LAO Contact

November 16, 2022

The 2023‑24 Budget

Considering Inflation’s

Effects on State Programs

- Summary

- Introduction

- Inflation Basics

- How and When Does the State Budget Account for Inflation?

- What Are the Consequences When State Spending Does Not Account for Inflation?

- LAO Comments

Summary

State Budget Automatically Accounts for Inflation in Some Areas. There are three mechanisms by which state spending is adjusted for inflation: (1) formulas, in which program spending is statutorily adjusted for certain factors, like a cost of living adjustment (COLA); (2) administrative decisions, in which the Legislature delegated authority to the administration to adjust costs with varying levels of discretion; and (3) legislative decisions, in which specific spending increases are determined through legislative deliberation and are directly approved by the Legislature. There is significant variation in the use of these mechanisms across the budget, such that some areas of the budget automatically account for inflation, but many others do not. Overall, a large share of state spending is adjusted to some degree formulaically or administratively (notably in K‑12 education and many health payments), however, a large number of programs are not.

Impacts of Not Accounting for Inflation. When programs require specific legislative action to adjust for inflation, those adjustments are less likely to occur. When program spending does not increase to account for inflation, the size and scope of those programs declines. Specifically, not adjusting for inflation can reduce the quantity or quality of state services, lower benefit levels for program recipients, reduce access to services, delay provision of services, or create challenges for hiring and retention. By not automatically accounting for inflation across all programs, however, the Legislature retains flexibility to ensure resources are provided to areas of highest priority.

Consider Whether Existing Automatic Adjustments Align With Legislative Priorities. There are benefits to both automatic and legislatively determined adjustments. We do not think that all—or even more—programs should have automatic COLA‑like adjustments or more statutory authority for administrative discretion. Broadly, automatic and administrative adjustments reduce the Legislature’s discretion over state spending. That said, the range of approaches and application of inflation adjustments varies in ways that might not always align with legislative priorities. Given current elevated levels of inflation, we suggest the Legislature consider whether the current automatic program spending adjustments target additional resources to areas of legislative priority.

Consider the Disparate Impacts of Inflation When Addressing This Year’s Budget Problem. Elevated inflation already has eroded the quantity and quality of state services to some degree. As we anticipate higher inflation to persist to an extent, further reductions to services are likely. Under our Fiscal Outlook, however, the Legislature will face a $25 billion budget problem in 2023‑24 and will not have surplus resources available to address inflation absent other spending or revenue changes. As the Legislature deliberates over how to address the upcoming budget problem, we advise considering how to mitigate the dual impact of inflation and funding reductions on programs.

Introduction

Over the course of 2022, elevated inflation has persisted, defying expectations of many professional forecasters. To the degree this continues—which our office thinks is likely to an extent—elevated inflation will have significant, although disparate, consequences across the state budget. This brief takes a case study approach to examine how elevated inflation has already impacted—and could continue to impact—state spending programs. Consequently, while this analysis covers a large share of the budget, it is not comprehensive. (We discuss the economic context for higher inflation, as well as the potential implications on revenues, in our report, The 2023‑24 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook.) Given these impacts, at the end of this brief, we provide some comments and guidance for the Legislature to consider ahead of the 2023‑24 Governor’s budget.

Inflation Basics

How Inflation Has Changed to Date. After decades of relatively low inflation, prices of many goods and services began increasing more rapidly in 2021. There are different ways to measure inflation, each reflecting different segments of the economy. One of the most common and broad‑based measures is the consumer price index (CPI), which reflects the cost of typical goods and services purchased by households. The California CPI was 7.5 percent as of the third quarter of 2022, compared to less than 3 percent over the previous five years. Other measures of inflation also are relevant to specific areas of state spending. For example, annual growth in the California Construction Cost Index (CCCI), published by the Department of General Services (DGS)—relevant to capital outlay and other infrastructure spending—was 13.4 percent in 2021, compared to an average of 3.1 percent over the previous five years. The California Necessities Index—a measure of price inflation for basic goods such as food and clothing that is relevant for some human services programs—grew by 6.6 percent in 2021, compared to an average of 3.6 percent over the previous five years.

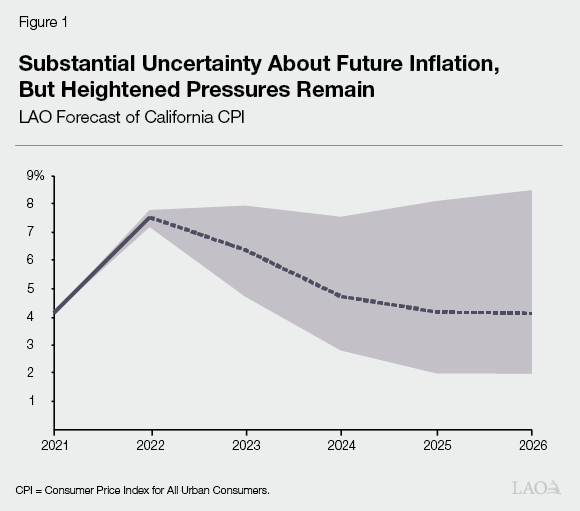

What Might Happen in the Future? The outlook for inflation in the coming years is highly uncertain. The Federal Reserve—tasked with maintaining stable price growth—has started to take actions to slow inflation by cooling the economy. While these efforts very well could return inflation in California to the pre‑pandemic norm of 2.5 percent per year, heightened inflation pressures—such as relatively high levels of consumer spending and wage growth—could result in elevated inflation that persists in the coming years. Reflecting these heightened pressures, our forecast of inflation in California, shown in Figure 1, has annual inflation dropping to about 4 percent and remaining there for the next few years. Other economic forecasters also see a significant risk of future inflation exceeding levels seen in recent years. For example, in a recent survey of professional forecasters, respondents put a 62 percent probability on U.S. inflation being 3 percent or higher in 2023—notably higher than the 2019 survey and the recent historical average.

While our forecast presents inflation estimates we think are most likely to be least wrong, in all likelihood they will be wrong to some extent. The shaded area in Figure 1 shows how inflation could differ from our main forecast. For example, by 2026, annual inflation levels ranging from 2 percent to 9 percent are plausible. Key factors contributing to the current uncertainty include the degree to which businesses and workers begin to expect heightened inflation in future years, the degree to which actions by the Federal Reserve to reduce inflation are successful, and changes in geopolitical events affecting food and energy prices.

How and When Does the State Budget Account for Inflation?

Ultimately, all changes in state spending are legislative decisions as the Legislature holds the constitutional power of appropriation. That said, in some cases, the legislature has delegated its authority such that some spending changes can be made without specific legislative deliberation. As a result, there are three general mechanisms for these spending adjustments, all of which require different levels of legislative input.

- Formulaic Adjustments. Cases in which program spending is adjusted by certain factors, like a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). These factors are set and approved in state law. These adjustments require limited annual legislative input, particularly when continuously appropriated.

- Administrative Decisions. Cases in which the Legislature has delegated authority to the administration to adjust costs with varying levels of discretion. In most cases, however, administrative decisions still require some type of legislative approval through statute, like the annual budget bill or a midyear budget adjustment bill.

- Specific Legislative Decisions. In all other cases, budgeted cost increases are determined through legislative deliberation and are directly approved by the Legislature. In these cases, the Legislature makes specific choices about whether and how to spend more funds to keep up with rising program costs. These changes can be one time, temporary, or ongoing.

The remainder of this section describes how these mechanisms are used across different categories of spending. In some areas, the state budget automatically adjusts for inflation using these mechanisms, whereas in other areas it does not.

Categories of Costs

Salaries and Benefits. Across the state budget, the largest category of state operations costs is for salaries and benefits for state employees. Increases in state employee pay typically are established in labor agreements, which are negotiated by the administration and ratified by the Legislature. Although salary increases for most employees covered by agreements ratified in 2022 were below inflation, over the past several years, state employee salary adjustments generally kept pace with inflation. Other benefit costs—such as for pensions, retiree health, and employee health benefits—also tend to increase with inflation. For example, state costs for retiree health are driven by the number of retirees receiving the benefit and the cost of health premiums. To the extent that inflation drives increases in health premiums, the state’s costs would increase automatically. Consequently, salary and benefit costs are adjusted for inflation through a combination of administrative and legislative decisions, as well as formulaic adjustments.

Lease Costs, Operating Expenses, and Equipment. A second major category of state operations costs is facilities and equipment. This includes, for example, the cost to state departments for leases and other rental costs, as well as operating expenses and equipment (OE&E)—such as printing, communication, and travel. In terms of rental payments, when a building is state‑owned, the department generally pays rent to DGS, which supports DGS’ operations and maintenance of the buildings. When a department’s underlying costs of rent or OE&E increase as a result of inflation or other factors, in general, the department must manage the increase within its existing budget. When budgeted rental amounts are systematically below actual costs, departments occasionally will submit a budget change proposal to the Legislature requesting additional appropriation authority to cover these higher costs. Consequently, adjustments for increases in lease costs and OE&E are driven by legislative decisions.

Lump Sums to Other Entities. In some other areas of the budget, the state provides lump sum amounts—sometimes referred to as block grants—to other entities of government, which those entities manage as part of their own budgets. This includes, for example, the majority of state funding to school districts, which is provided through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF); base funds provided to the universities; and funds to the trial courts. In each case, the Legislature might set expectations for the other entities in using the funds, but to a large extent, the other entity is responsible for making decisions about how to allocate state funds, usually alongside other funding sources (such as local property tax revenue or student tuition revenue). In these cases, when costs increase as a result of inflation, state funds sometimes adjust automatically and sometimes do not. For example, there is a statutory annual COLA for LCFF based on a measure of inflation, but the Legislature must decide each year what adjustments to make to trial courts and universities in response to inflation and other cost increases.

Contracts, Grants, and Awards. Through a variety of processes, including competitive bids, the state regularly awards contracts, grants, and awards to third‑party entities to provide goods and services. These types of arrangements exist across nearly every area of state government, but some illustrative examples include: the California Department of Transportation, which contracts with construction companies to build and maintain roads; the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, which provides grants to local governments and nonprofit organizations for forest resilience; and the Department of Housing and Community Development, which awards funds to developers for affordable housing projects. Typically, inflation does not result in spending increases for existing agreements between the state and private entities because the state does not renegotiate awards or contracts once they are made (although high inflation can increase costs for contractors and heighten the risk of project failure). This means that, once a grant, award, or contract has been made, the contractor or grantee generally bears the risk of the project—for example, due to rising prices of materials or energy—and award amounts are not correspondingly adjusted upward. (There are some narrow exceptions to these rules, depending on the department, type of contract, and the terms of the agreement.) New awards, grants, and contracts can account for inflation as bidders and applicants develop and negotiate costs in their subsequent applications and proposals. Budgeted costs only increase, however, if the Legislature increases funding for the program, otherwise, fewer awards, grants, and contracts are awarded.

Capital Outlay. For budgetary purposes, capital outlay includes purchases of land and state‑owned projects involving construction of new facilities or renovation of existing facilities. Government Code allows the State Public Works Board to augment the costs of major capital outlay projects by up to 20 percent with legislative notification. Larger augmentations require legislative approval. The same section of Government Code also gives the Department of Finance the authority to change the scope of major projects with notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee and, in cases where a project is authorized with multiple fund sources, to determine which of the fund sources will bear the costs of that augmentation. Consequently, up to a certain point, adjustments for increases in capital outlay costs are made by administrative decisions.

Provider Rates. For some service‑based programs, the state pays specific rates to private and nonprofit entities to deliver services to program beneficiaries. Examples of provider rates include child care vouchers, Medi‑Cal managed care payments, and developmental service provider rates. Across these services, there is variation in how these rates are adjusted for inflation. For example, child care vouchers are based on a survey of market child care costs, however, the Legislature must adopt new rates based on those surveys in order to adjust the value of the vouchers for inflation. In contrast, inflationary pressures are incorporated into the Department of Health Care Service’s process for setting capitated rates in Medi‑Cal managed care. This process uses a variety of sources of data and projections of costs and prices. Consequently, this process results in changes based on both formulaic and administrative adjustments. In the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), although the Legislature recently enacted a plan to support rate models developed in a 2019 study (and updated to 2021‑22 levels), under current law, providers would only receive rate adjustments based on future legislative decisions.

Administrative Costs. While many health and human services programs are, in large part, jointly financed by the state and federal governments, the state has delegated various administrative functions—including intake and eligibility determinations of new applicants and ongoing eligibility case management activities—to counties. This includes, for example, Medi‑Cal, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). To support these functions, the state pays a share of counties’ costs based expected workload. In the case of Medi‑Cal, state payments to counties for program administration are automatically adjusted for inflation annually. For other programs, including CalWORKs and SNAP, they are not. Consequently, while some programs’ administrative costs are adjusted by formula, others are determined by legislative decisions.

In‑Kind, Cash, and Cash‑Like Benefits. The state provides some in‑kind, cash, and cash‑like benefits directly to individuals. These benefits include, for example, cash assistance programs like CalWORKs and Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP), as well as Cal Grants provided to students for non‑tuition expenses. In general, these benefits are not automatically adjusted for changes in beneficiaries’ cost of living. Some of these programs also receive other adjustments, for example, SSI/SSP grants receive an annual, federally funded COLA on the federal share of the grant and CalWORKs grants are increased based on a complex formula based on growth in some 1991 realignment revenues. Consequently, while there are some formulaic adjustments to program benefits, increases to state‑funded benefits largely are determined through legislative decisions.

What Are the Consequences When State Spending Does Not Account for Inflation?

This section describes the impacts on programs and services when budgeted spending does not account for inflation. Throughout this section, we sometimes discuss spending in terms of its real value. The nearby box describes this term.

Real Value

The real value of a dollar refers to the amount of goods and services that dollar can buy. Over time, the real value of a dollar decreases due to inflation. For example, suppose the state spends $100,000 to provide services to ten people. In the next year, the cost of providing the service increases 10 percent, so the state can only provide those services to nine people. As a result, we can say that the “real” value of the state’s dollar has declined 10 percent.

Lowers Quantity of Services. One of the most common impacts of elevated inflation for spending programs is a reduction in the quantity of state services provided. This is true across many areas, but in recent months, consistent with significantly higher growth in the CCCI, impacts have been particularly acute in construction‑related areas and others making use of heavy mechanized equipment. These areas include, for example, housing construction, fire management, and transportation. In these cases, inflation results in a reduced service level relative to what was originally anticipated by the Legislature. As a result, the state will build fewer housing units, treat fewer acres of forest for wildfires, and perform less maintenance of state roads and highways. In one particularly telling, although narrow, example, the California Department and Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) reported that one project appropriated in the 2020‑21 budget—a pest eradication capital outlay project—experienced a 25 percent increase in estimated cost. As a result, CDFW had to nearly halve the size of the structure it had planned.

Lowers Quality of Services. In other budget areas, inflation can result in a reduction of quality, rather than quantity, of services. For example, in county administration of human services programs, less state funding in real terms can mean local governments have lower staffing levels. Fewer staff means higher caseloads, which can result in adverse impacts to program timeliness and accuracy, particularly for redeterminations and case management. In another similar example, regional centers—which provide services to consumers with developmental disabilities—are funded by the state with a core staffing formula that largely has been frozen since 1991. While the formula funds the Service Coordination position at $34,032 per year, regional centers pay, on average, $67,000 for this position. Regional centers report that, as a result, they hire fewer service coordinators and those service coordinators carry average caseload ratios of roughly 1:78 consumers—above statutory limits, which range from 1:25 to 1:66 based on several categories of consumer need. These elevated caseload ratios likely are having negative impacts on service quality and quantity for consumers. Continued high inflation would further erode the real value of the formula‑driven funding level for these positions.

Lowers Benefit Levels. Elevated inflation also results in lower benefit levels for recipients, in real terms. As described earlier, most state cash and cash‑like benefits, such as for CalWORKs, SSI/SSP, and the non‑tuition portion of state Cal Grants, currently are not adjusted for inflation. As a result, we expect the real value of these assistance programs to decline more rapidly than prior years as higher inflation persists. As a result, program beneficiaries will not be able to afford the same level of goods and services.

Reduces Access to Services. In some limited cases, higher inflation can result in reduced access to or longer wait times for state services. In the case of both DDS and, potentially, Medi‑Cal fee for service, if elevated inflation persists, rates would erode in real terms. This could further exacerbate issues of coverage, for example by reducing the number of providers willing to participate in either system.

Delays the Provision of Services. In some cases, elevated inflation results in service delays. These challenges are particularly relevant in several construction‑intensive areas, but a key example is in housing—specifically, housing projects that are still being planned. High inflation has resulted in delays as developers have needed to spend more time securing additional capital—above what was originally anticipated—to finance the projects before construction can begin. In a higher inflationary environment, longer delays also can lead to higher housing development costs, further reducing housing production. In other examples, state departments have held positions open as a way of managing higher costs without additional spending authority. This can result in delays as staff are redirected between workloads.

Lowers Real Incomes for Employees and Causes Challenges for Hiring and Retention. As we discussed earlier, for many years, general salary increases agreed to through collective bargaining generally have kept pace with inflation, although those agreed to in 2022 did not. To the extent salary increases are below inflation, real incomes of state employees will decline. If persistent, lower salaries can make hiring and retaining employees challenging for state departments. Moreover, when a state department must compete with the private sector and/or local government for employees, these challenges can be particularly acute. As we put together this analysis, nearly every state department we spoke with reported some level of difficulty with hiring and retention and anticipated that continued inflation would result in additional challenges.

Exacerbates Preexisting Challenges. In many cases, inflation does not necessarily cause severe problems in isolation, but rather exacerbates preexisting challenges. For example, in areas like forest management and housing where the state government recently significantly expanded state spending, the state is running into supply issues. These supply challenges range from hiring enough contractors to complete needed work to securing raw materials to build housing. In addition to supply shortages, reaching legislative goals for some programs also becomes more challenging when there is elevated inflation. For example, the Legislature has stated a goal of setting CalWORKS grants at 50 percent of the federal poverty level. When inflation is high, not only does the purchasing power of the grant decline more rapidly, but also the resources required to meet the Legislature’s goal increase faster.

Heightens Risks of Project Failure. As we mentioned earlier, in some cases, the state can shift the risk of inflation to contractors when entering into agreements and contracts. Contractors for many state services often already have subcontracts in place with fixed prices for materials, which mitigates their risk as well. However, persistently high and very elevated inflation can nonetheless increase the risk of contractors failing to meet the terms of the contract. Sometimes this results in delays to project completion, for example, if the state has to rebid the project. But in extreme cases, it could heighten the risk of project failure altogether. Another key metric of risk is not only the level of inflation, but also changes in it. In some areas, the unpredictability of inflation—swings in the rate of growth of prices—can pose greater issues. If inflation is high, but stable, contractors and developers can plan for it and account for growth in prices in projections. Large swings in inflation are much more difficult to integrate into plans and therefore can result in significantly more risk, either for the contractor or the state.

LAO Comments

Elevated inflation already has eroded the quantity and quality of state services to some degree. As we anticipate higher inflation to persist, further reductions to services are likely. Under our Fiscal Outlook, however, the Legislature likely will face a budget problem in 2023‑24 and will not have surplus resources available to address inflation. As the Legislature deliberates over how to address the upcoming budget problem, we advise considering how to mitigate the dual impact of inflation and funding reductions on programs. Below, we describe these dynamics in more detail.

Consider Whether Existing Automatic Adjustments to Programs Align With Legislative Priorities. When programs require specific legislative action to adjust for inflation, those adjustments are less likely to occur. There are benefits to both automatic and legislatively determined adjustments. We do not think that all—or even more—programs should have automatic adjustments or more statutory authority for administrative discretion. Doing so would reduce the Legislature’s discretion over state spending. That said, the range of approaches and application of inflation adjustments varies in ways that might not always align with legislative priorities. For example, some types of capital projects are subject to administrative augmentation whereas others are not. Both types of projects may be infrastructure in the broad sense, with differences—like ownership of the asset—making one but not the other eligible for administrative augmentation. As the Legislature considers the Governor’s budget, we suggest it also consider which programs have preexisting processes for adjusting for inflation and which do not and whether automatic adjustments align with its priorities.

Accounting for Inflation Would Increase Budget Problem. In our recently released report, The 2023‑24 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we estimated that the Legislature will face a budget problem of $25 billion in the upcoming budget cycle. A budget problem occurs when the state’s anticipated General Fund revenues are expected to be lower than expected General Fund costs under current law and policy. However, as we have discussed extensively here, in many cases, budgetary spending does not automatically adjust in response to inflation—meaning the actual costs to maintain the state’s service level are higher than what our outlook reflects. Consequently, the traditional definition of a budget problem understates the actual budget problem, assuming the Legislature wanted to maintain its current level of services.

Consider Inflation When Addressing the Budget Problem. The Legislature is likely to face a double challenge this year: a budget problem coupled with continued, elevated inflation. As the Legislature works to address the budget problem, we suggest policymakers consider the unique impacts of inflation on each of the state’s major spending programs in conjunction with possible budget solutions. For those programs whose costs have not been recently adjusted for inflation, budget reductions could result in greater reductions in service. In other cases, pausing automatic adjustments could free up resources and mitigate the need for reductions. If the Legislature wants to provide new inflation adjustments in some areas in response to higher prices, the size of the budget problem will increase, meaning corresponding reductions to other areas also would be required.