LAO Contact

January 4, 2023

Assessing California’s Climate Policies

The 2022 Scoping Plan Update

- Summary

- Introduction

- Background

- Overview of 2022 Scoping Plan Update

- Assessment of Plan to Meet 2030 Goals

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Summary

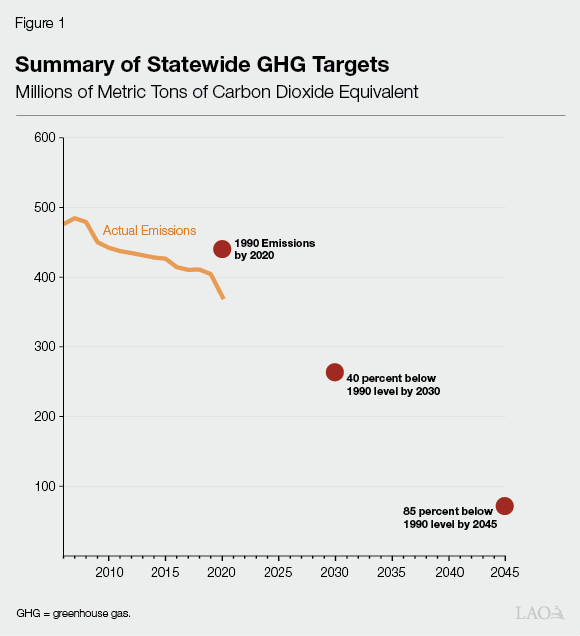

2022 Scoping Plan Update Identifies Pathway to Long‑Term 2045 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Goal. California has established statutory goals for reducing statewide GHG emissions—down to at least 40 percent below the 1990 level by 2030, and to at least 85 percent below the 1990 level by 2045. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) must develop a plan for meeting these goals, and update this Scoping Plan every five years. In its recently adopted plan, CARB selects its preferred pathway to meeting the state’s long‑term 2045 GHG goal, and adopts a new, more ambitious goal for 2030 (48 percent reduction below the 1990 level).

Plan Lacks a Clear Strategy for Meeting 2030 GHG Goals. In this brief, we evaluate CARB’s plan for meeting the state’s 2030 GHG goals. Despite the significant reductions needed to meet these goals, CARB’s plan does not identify which specific policies it will implement. For example, the plan is unclear regarding how much the state will rely on financial incentives, sector‑specific regulatory programs, or cap‑and‑trade. Rather, the plan’s estimated reductions are driven primarily by assumptions developed by CARB, without specifying how those assumed outcomes might be achieved. The lack of focus on policy options is a missed opportunity that has important ramifications for California’s overall GHG reduction efforts, including:

- The lack of specificity likely will lead to delayed action, as it defaults to state departments to identify necessary implementation steps. This increases the risk that the state will not meet its statutory 2030 GHG goal, much less CARB’s more ambitious target.

- If the state needs to adopt policy changes in a relatively short period of time to meet its goal, this could be costlier and/or disruptive for private businesses and households.

- The plan does not provide the Legislature with sufficient information—such as about cost‑effectiveness, distributional impacts, or other environmental impacts—to evaluate the merits of new policies that might be needed to meet the 2030 goal.

- Failing to develop a credible plan to meet statewide GHG goals could adversely affect California’s ability to serve as an effective model for other jurisdictions or demonstrate global leadership.

Cap‑and‑Trade Program Is Not Currently Positioned to Close 2030 Emissions Gap. CARB indicates that it will evaluate the cap‑and‑trade program in 2023 to determine whether changes are needed to help meet its 2030 goal. We find that cap‑and‑trade is not currently positioned to ensure the state meets it statutory 2030 GHG goal, much less CARB’s more ambitious target. In short, the program is not stringent enough to drive the additional emission reductions needed because there will be more than enough allowances available for covered entities to continue to emit at levels exceeding the 2030 target. This could also lead to relatively low allowance prices, as well as reduced and volatile cap‑and‑trade auction revenue.

Recommend Legislature Require CARB to Clarify 2030 Plan and Consider Cap‑and‑Trade Changes. We recommend the Legislature direct CARB to submit a report to the Legislature by July 31, 2023 that clarifies its plan for reducing GHG emissions to meet the 2030 statutory goal. We also recommend the Legislature consider changes to the cap‑and‑trade program to address concerns about program stringency. Potential modification options include: reducing the supply of allowances issued in future years, limiting the use of offsets (credits generated from GHG reductions taken by entities not covered by cap‑and‑trade), and extending the program beyond 2030.

Introduction

In this brief, we describe and assess the California Air Resources Board’s (CARB’s) 2022 Scoping Plan Update (hereafter Scoping Plan)—the state’s primary plan for how it will reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Specifically, our brief includes: (1) background on statewide GHG emissions and emission reduction goals, (2) an overview of the 2022 Scoping Plan Update, (3) an assessment of CARB’s plan to achieve the state’s 2030 GHG reduction goal, and (4) recommendations for legislative next steps. This brief was developed pursuant to Chapter 135 of 2017 (AB 398, E. Garcia), which requires our office to report annually on the economic impacts and benefits of the state’s 2020 and 2030 GHG goals.

Focus of This Brief Is on 2030 GHG Goal. As we discuss in more detail later in this brief, the Legislature has adopted specific statewide GHG emission goals for 2020, 2030, and 2045. We focus this analysis on CARB’s plan for achieving the 2030 goal. The main reasons we choose to focus on the 2030 goal, rather than the long‑term 2045 goal, are:

- This brief is submitted pursuant to our AB 398 statutory requirement which directs our office to assess the impacts of achieving the state’s 2030 GHG goal, but does not reference the 2045 goal.

- The 2030 goal reflects the state’s next significant GHG reduction benchmark and a key interim step towards putting the state on track to try to meet its long‑term 2045 GHG goal.

- Economic impacts and benefits depend heavily on technological advancements of various GHG‑reduction technologies and changes in broad economic conditions, both of which are difficult to forecast over long time horizons. While even evaluating potential environmental and economic impacts in 2030 is challenging, the effects in 2045 are subject to far greater uncertainty.

Background

Legislature Has Set Various GHG Goals. The Legislature has adopted three successive statewide GHG emission reduction goals (also known as targets):

- 2020. Chapter 488 of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley) established the goal of limiting GHG emissions statewide to the 1990 level by 2020.

- 2030. Chapter 249 of 2016 (SB 32, Pavley) extended the limit to at least 40 percent below the 1990 level by 2030.

- 2045. Chapter 337 of 2022 (AB 1279, Muratsuchi) extended the limit to at least 85 percent below the 1990 level by 2045. Assembly Bill 1279 also established a goal of zero net carbon emissions by 2045, commonly known as carbon neutrality. (For more detail on carbon neutrality, see the box below.)

What Is Carbon Neutrality?

Carbon neutrality is when the amount of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) being added to the atmosphere (sources) equals the amount of GHGs that are being removed from the atmosphere (sinks). Sources of GHGs include carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion and methane emissions from agricultural activities—all of which are part of the state’s emission reduction targets described in this brief. However, carbon neutrality also incorporates other sources as well as sinks that are not typically counted as part of state emissions, such as net changes in the amount of carbon in forests and the amount of carbon dioxide that is removed from the atmosphere and stored underground. These types of activities are also known as carbon dioxide removal.

State Met 2020 Target Early, but 2030 and 2045 Goals More Ambitious. As shown in Figure 1, statewide GHG emissions have decreased in recent years—dropping below the 2020 target several years ahead of schedule. However, emissions would need to decline much faster in order to meet the 2030 and 2045 targets. For context, from 2010 to 2019, emissions declined by about 1 percent annually. In contrast, meeting statutory statewide emission reduction goals would require average annual reductions of 4 percent from 2019 to 2030, and 9 percent between 2030 and 2045.

Notably, statewide emissions declined substantially in 2020—mostly due to reduced driving and economic activity in the initial months of the pandemic. However, preliminary data show that emissions subsequently bounced back in 2021, suggesting that much of the reduction was temporary. Similarly, although a potential future period of reduced economic activity—such as a recession—likely would result in another dip in emissions, temporary changes in economic activity alone are unlikely to drive the magnitude of emission reductions needed to meet the 2030 goal, much less the sustained reductions needed to meet the longer‑term 2045 target.

CARB Required to Develop Scoping Plan for Meeting Statewide GHG Targets. State law requires CARB to develop a Scoping Plan and update it at least every five years. The Scoping Plan is meant to identify CARB’s strategy for achieving the statewide GHG targets. Statute requires that the plan must, among other things, identify and make recommendations on measures to facilitate the achievement of the maximum technologically feasible and cost‑effective reductions of GHGs. In addition, for each emissions reduction measure identified in the plan, it must identify the following information:

- The range of projected GHG emissions reductions that result from the measure.

- The range of projected air pollution reductions that result from the measure.

- The cost‑effectiveness of the measure.

Overview of 2022 Scoping Plan Update

After conducting a series of workshops over the last couple of years and issuing a draft plan in May 2022, CARB formally adopted its final 2022 Scoping Plan Update in December 2022. In this section, we provide an overview of the plan.

Plan Highlights Several Potential Scenarios and Selects Preferred Path. As a starting point, CARB estimates emissions under a “Reference Scenario,” which is meant to reflect what future emissions would be under current state practices and policies (excepting any potential emission reductions from the state’s cap‑and‑trade program). As shown in Figure 2, the board estimates that under the Reference Scenario, the state would fail to meet both its 2030 and 2045 GHG goals. CARB then models four different alternative scenarios—each making different assumptions about how and when the state reduces emissions. To model the four alternative scenarios, CARB makes various assumptions about household behavior—such as per capita vehicle miles traveled (VMT)—and technology adoption—such as how many electric heat pumps are installed in buildings, how many refineries install carbon capture and storage (CCS), and how much carbon dioxide removal is deployed. Alternatives 1 and 2 would achieve carbon neutrality by 2035, whereas Alternatives 3 and 4 would achieve carbon neutrality in 2045. Figure 3 summarizes some of the key assumptions CARB used to develop the four alternatives it modeled in the plan.

Figure 3

Summary of Scoping Plan’s Four Scenarios

|

Assumptions |

Scenario |

|||

|

Alternative 1 |

Alternative 2 |

Alternative 3 |

Alternative 4 |

|

|

Reductions in per capita vehicle miles traveled |

|

|

|

|

|

Adoption of light‑duty ZEVs |

|

|

|

|

|

Changes to petroleum refining |

|

|

|

|

|

Sales of electric HVAC and water heaters for existing buildings |

|

|

|

|

|

Reductions in dairy methane emissions |

|

|

|

|

|

Carbon dioxide removal |

|

|

|

|

|

ZEV = zero‑emission vehicle; CCS = carbon capture and storage; and HVAC = heating, ventilation, and air conditioning. |

||||

CARB selected Alternative 3—also known as the Scoping Plan Scenario—as its preferred modeling scenario for taking actions to achieve the state’s GHG emissions reduction goals. According to CARB, this alternative most closely aligns with existing statute and executive orders, and best achieves the balance of cost‑effectiveness, health benefits, and technological feasibility. Figure 2 displays CARB’s projections for GHG reductions under this Scoping Plan Scenario. As shown in the figure and discussed below, these projections assume that under this scenario, the state will be below its statutory GHG target in 2030.

Focuses on 2045 Goals. Most of the plan—including the modeling and analysis—focuses on the state’s long‑term 2045 carbon neutrality goal. For example, under each alternative, CARB estimates GHG emission reductions, air pollution reductions, and cost‑effectiveness associated with different groups of emission reduction measures. However, these estimates focus almost exclusively on effects in 2035 and 2045, with limited information on the projected effects in 2030. (CARB analyzes 2035 effects because Alternatives 1 and 2 would seek to achieve carbon neutrality by 2035.)

Identifies More Aggressive 2030 GHG Goal. As it relates to the 2030 goal, perhaps the most significant change in the 2022 plan (as compared to previous Scoping Plans) is that it identifies a new GHG target of 48 percent below the 1990 level, compared to the current statutory goal of 40 percent below. (Hereafter, we will refer to the 48 percent reduction as the Scoping Plan goal and the 40 percent reduction as the statutory goal.) Current law requires the state to reduce GHG emissions by at least 40 percent below the 1990 level by 2030, but does not specify an alternative goal. According to CARB, a focus on the lower target is needed to put the state on a path to meeting the newly established 2045 goal, consistent with the overall path to 2045 carbon neutrality.

Assessment of Plan to Meet 2030 Goals

Based on our assessment of CARB’s plan for reducing emissions by 2030—including both addressing the statutory goal and the newly identified Scoping Plan goal—we have two primary findings: (1) the plan lacks a clear strategy for meeting the 2030 GHG goals and (2) the cap‑and‑trade program is not currently positioned to close a 2030 emissions gap.

Plan Lacks Clear Strategy for Meeting 2030 GHG Goals

In this section, we assess how well the 2022 Scoping Plan Update positions the state to meet its 2030 GHG reduction goal. We find that the plan’s lack of specific policy strategies could result in a number of negative implications.

Meeting 2030 Goals Will Require Major Acceleration of Emission Reductions. Meeting the 2030 statutory goal for reducing GHG emissions by 40 percent below the 1990 level already would require the state to significantly accelerate its rate of emission reductions, relative to historical norms. On average, the state has reduced emissions by about 1 percent annually over the last decade. As previously mentioned, meeting the 2030 statutory goal would require a 4 percent average annual reduction. However, as noted above, the Scoping Plan sets an even more ambitious target of reducing GHG emissions by 48 percent below the 1990 level. This would require a 5 percent average annual reduction from 2019 to 2030—an even greater acceleration of existing trends. For context, since 2000, statewide annual emissions have only ever dropped by more than 3 percent twice:

- A 6 percent reduction occurred from 2008 to 2009. This was around the time of the Great Recession. Also, in 2009, CARB made some changes to the way it counts emissions from electricity imports, which could have contributed to its calculated drop in emissions.

- A 9 percent reduction occurred from 2019 to 2020. This was during the first year of the COVID‑19 pandemic so it reflected many temporary, rather than permanent, changes in business and household behaviors.

Plan Lacks a Clear Description of What Policy Approaches Will Be Deployed to Reduce Emissions. Generally, the plan does not identify which policies will be used to reduce emissions in order to meet the 2030 targets (for either the statutory goal or the Scoping Plan goal). Rather, the plan’s estimated reductions are primarily driven by assumptions developed by CARB and the third‑party contractors who led the modeling effort, without specifying how those assumed outcomes might be achieved. The assumptions for the Scoping Plan Scenario were selected to illustrate a scenario where the state meets its targets. For example, the plan assumes the state will make the following changes:

- VMT. The plan assumes a 25 percent reduction in per capita VMT by 2030. In contrast, CARB assumes continuing with current policies (the Reference Scenario) would lead to a 4 percent reduction in VMT by 2045.

- CCS. The plan assumes CCS will be installed on 70 percent of refineries by 2030. Under current policy, CARB assumes no CCS will be installed on refinery operations.

- Building Electrification. The plan assumes 80 percent of new heating, ventilation, and air conditioning and water heater sales will be electric by 2030, in both residential and commercial buildings. Under current policy, CARB assumes 15 percent of sales will be electric.

These assumptions are significant drivers of the overall emission reductions the Scoping Plan Scenario expects the state to achieve in 2030. The plan does not, however, provide any clear description of what types of policies will drive these changes. For example, it is unclear how much the state will rely on financial incentives, sector‑specific regulatory programs, or cap‑and‑trade to achieve these reductions. The current plan does not provide any clear direction or roadmap for these types of decisions. Instead, CARB indicates that an evaluation of all major programs will be needed to assess their effectiveness and their specific GHG reduction objectives between now and 2030. (The plan includes some estimated impacts of adopting different technologies and behaviors needed to meet the 2045 goal, but these do not focus on specific policies that might be used to meet the 2030 goal.)

Lack of Clear Policy Approach Has Several Key Downsides. In our view, the lack of focus on policy options in the Scoping Plan Update is a missed opportunity that has important ramifications for California’s overall GHG reduction efforts. The major downsides include:

- Delayed Action Increases Risk That State Will Not Meet 2030 Goal. Without a clear policy approach articulated in the Scoping Plan, how—and whether—the state will meet the statutory 2030 GHG goal is unclear, much less how it will meet the more ambitious Scoping Plan goal. The lack of specific direction means that state departments will need to spend additional time and effort to identify and evaluate what policy changes will be required to achieve the intended outcomes before they can even begin the process of adopting and implementing those changes. Overall, many of these efforts likely will take years. Such a delay increases the risk that the state will not meet its 2030 goal.

- Rushed Policy Implementation Could Be More Costly. Even if state departments do take subsequent actions to identify, evaluate, and adopt new or modified policies in order to try to meet the ambitious 2030 targets, these policies would then need to achieve reductions in a relatively short period of time. A more rushed implementation time line could be costlier and/or more disruptive for private businesses and households.

- Limits Information Available for Key Legislative Decisions. Different policy approaches are likely to have varying associated advantages and disadvantages, including the magnitude of GHG reductions, improvements in local air pollution, economic costs, and how costs and benefits are distributed across various groups. However, without a clearly articulated policy approach, evaluating trade‑offs associated with specific policies used to meet the 2030 target is difficult—thereby limiting the amount of information that the Legislature has available to make near‑term budget and policy decisions. Specifically, the plan lacks information that the Legislature could use to evaluate the costs and benefits of a new policy that might be needed to meet the 2030 goal, how its impacts would be distributed across different households, and how it compares to alternative emission reduction measures. For example, if the Legislature were considering whether to allocate funding for either providing rebates for electric heat pumps or for electric trucks, it would lack helpful information to inform this decision, including the respective programmatic costs per ton of GHGs reduced, how much each activity would reduce local air pollution, and how the benefits of each activity would accrue to different regions or households.

- Could Adversely Affect California’s Ability to Demonstrate Global Leadership. The lack of a clear plan might have other downsides that are more difficult to identify, but nonetheless important for California’s effort to encourage global action on climate change. Since California represents only about 1 percent of global GHGs, the ultimate success of its climate policies depends on whether it spurs emission reductions in other jurisdictions. For example, California might influence other jurisdictions by demonstrating how to adopt and implement a plan to achieve ambitious GHG reduction goals. However, failing to develop a credible plan to meet statewide goals could limit the degree to which California can serve as an effective model for other jurisdictions. This could lead to California missing an opportunity to expedite global progress on limiting the extent of climate change.

Cap‑and‑Trade Program Not Currently Positioned to Close 2030 Emissions Gap

In this section, we provide our assessment of whether we believe the cap‑and‑trade program—as currently structured—can help ensure that the state meets its 2030 goals. We find that, although the program can be a cost‑effective way to achieve GHG goals, cap‑and‑trade is not currently positioned to make up for any significant shortfall in emissions reductions from other programs.

Scoping Plan Update Does Not Specify Role for Cap‑and‑Trade. The cap‑and‑trade program covers sectors and activities that represent about 75 percent of statewide GHG emissions—primarily emissions from transportation fuels, electricity, natural gas, and industrial activities. In its 2017 Scoping Plan Update, CARB expected non‑cap‑and‑trade programs to achieve roughly half of the emission reductions needed to meet the statutory 2030 annual target, with cap‑and‑trade making up the other half. Moreover, the 2017 plan then identified cap‑and‑trade as the state policy that would serve as a “backstop” to ensure the state meets its target. That is, the plan explicitly stated that to the degree other policies collectively fell short of meeting the state’s GHG reduction goals—sometimes referred as an emissions gap—the cap‑and‑trade program would reduce emissions further to make up the difference. In contrast, the 2022 Scoping Plan Update does not specify what role cap‑and‑trade is expected to play in reducing emissions. Instead, CARB indicates that the administration will submit a report to the Legislature by the end of 2023 containing potential suggestions on programmatic changes to ensure the program is well‑positioned to help the state meet its goals.

Cap‑and‑Trade Can Be a Cost‑Effective Way to Achieve GHG Goals… Economywide carbon pricing policies, such as cap‑and‑trade, generally have been found to be the most cost‑effective approaches to reducing GHG emissions. In a cap‑and‑trade program, covered entities face a choice to either (1) purchase allowances or offsets to be able to continue to emit, or (2) reduce emissions. As a result, the program sends price signals to households and businesses to encourage them to identify and undertake low‑cost emission reduction activities. (For more information on this issue, see our previous reports—The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade, Assessing California Climate Policies—Transportation, and Assessing California’s Climate Policies—Electricity Generation.) Also, in theory, the “cap” on emissions—which controls emissions by limiting the number of allowances issued—can serve as a backstop to other programs and policies to ensure the state meets certain goals. Strict enforcement of this cap can thereby reduce uncertainty about whether the state will meet its overall emission reduction goals, even if other factors—such as unsuccessful policy implementation or changing economic conditions—drive emissions higher than expected. As a result, we think using cap‑and‑trade as a key policy tool for achieving the state’s GHG goals is a reasonable approach.

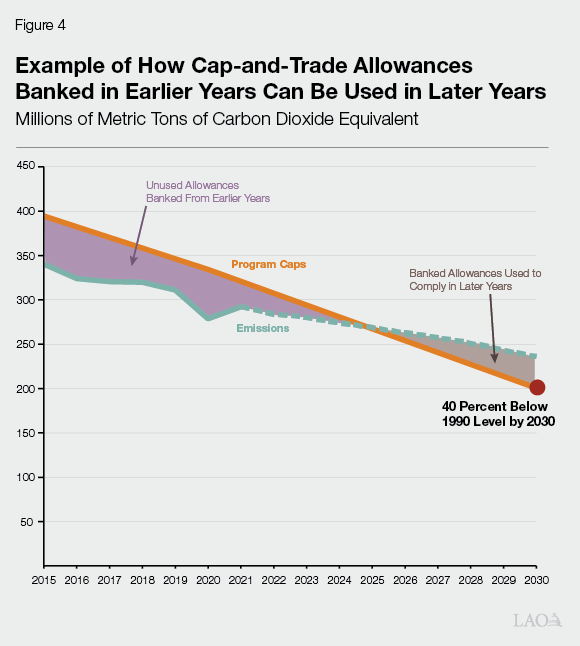

…But Program Is Not Currently Well‑Positioned to Ensure State Meets Its 2030 Target. In practice, however, the cap‑and‑trade program currently is not calibrated in a way that will allow it to serve as the backstop for meeting the state’s statutory 2030 goal, much less the more ambitious Scoping Plan target. In short, the program is not stringent enough—that is, it will not drive the additional emission reductions needed to close a 2030 emissions gap. One key reason for this is because there will be more than enough allowances available for covered entities to continue to emit at levels exceeding the 2030 target. As we described in our 2017 report, Cap‑and‑Trade: Issues for Legislative Oversight, the program allows unlimited banking of allowances from earlier years, which can then be used to comply with more strict caps in later years. If a significant number of allowances are “banked” in the earlier years, covered entities can then continue emitting GHGs in 2030 at levels that exceed the state’s targets.

Figure 4 illustrates an example of how this could occur, under a scenario where covered emissions track CARB’s Reference Scenario and continue to make up about 75 percent of total statewide emissions. Assuming no program modifications or extension of the cap‑and‑trade program beyond 2030, covered emissions would be only 29 percent below the 1990 level in 2030 (236 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent)—which would fail to meet both the statutory goal (reduce to 201 million metric tons) and Scoping Plan goal (reduce to 175 million metric tons). We also estimate that a cumulative total of about 200 million unused allowances would remain at the end of 2030. As a result, covered entities would have more than enough allowances to comply with the regulation without actually needing to reduce their emissions any farther.

Program Stringency Is a Concern Under A Range of Scenarios. The example in Figure 4 is only one of many possible scenarios, as significant uncertainty about future emissions remains. However, under a wide range of different emissions scenarios that we analyzed—including a scenario where covered emissions decline more slowly (1 percent annually) and a scenario where covered emissions decline more quickly (nearly 4 percent annually)—the state would fail to meet its statutory goal and a significant number of unused allowances would remain at the end of 2030. Notably, a significant decline in emissions driven by other policies or economic conditions also would result in even more unused allowances—making it even less likely that cap‑and‑trade could act as a backstop to limit emissions and close any remaining emissions gap in 2030.

Lack of Program Stringency Also Affects Allowance Prices and Auction Revenue. An overall supply of allowances that significantly exceeds demand also results in relatively low allowance prices and affects future state revenue from cap‑and‑trade auctions—both of which could make it harder for the state to meet its GHG goals in 2030 and future years.

- Low Allowance Prices. An over‑supply of allowances eventually will result in a significant drop in their market price—likely to levels near or below the floor price established by CARB. When prices would drop to these levels is unclear, but they likely would approach the floor as market participants (such as covered entities) become more confident that there will be excess allowances available through 2030. Although reduced allowance prices mean lower direct costs for households and businesses, they also mean the cap‑and‑trade program would have less of an effect on emissions.

- Reduced and Volatile GGRF Revenue. As allowance prices decline, so too will the state cap‑and‑trade auction revenue that goes into the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). These monies fund a wide variety of environmental and transportation programs. As covered entities begin to see that more allowances than they need are available, some of the allowances offered at state auctions likely will go unsold. As a result, the state will have very low and/or volatile GGRF revenue at these auctions—making it more difficult to fund the various programs that typically rely on GGRF funding, including programs intended to help the state meet its GHG reduction goals. This revenue scenario could be somewhat similar to the auction results from 2016 and early 2017, where the state sold very few allowances and generated almost no revenue. (See our report, The 2017‑2018 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade, for more details.)

Recommendations

Require CARB to Clarify Plan for Meeting 2030 Goals. We recommend the Legislature direct CARB to submit a report to the Legislature by July 31, 2023 that clarifies its plan for reducing GHG emissions to meet 2030 goals. As part of this report, CARB should identify new or expanded policies that would be used to meet both the statutory goal and the Scoping Plan goal, including the role that it expects cap‑and‑trade to play. The report should also include additional details about the estimated emission reductions, air pollution reductions, distributional impacts, and cost‑effectiveness of each of those policies. Such a report would help the Legislature: (1) evaluate the feasibility of the administration’s new 2030 goal, (2) assess whether it agrees with the administration’s policy approach or whether it would like to pursue a modified approach, (3) identify potential policy or budget actions needed to meet the Legislature’s 2030 benchmark, and (4) ensure there is adequate legislative oversight of the administration’s implementation of the plan. We recognize that specifying the details of every policy and conducting a thorough analysis of each policy might not be feasible by July 2023. However, given the available resources at CARB, we think providing a significant amount of additional detail and analysis is both reasonable to expect and valuable for legislative decision‑making.

Consider Changes to Cap‑and‑Trade Program to Make It More Consistent With Legislative Goals. We recommend the Legislature consider changes to the cap‑and‑trade program to address concerns about stringency, and make it more consistent with achieving 2030 GHG goals. The state has several options for modifying the program, including one or more of the following:

- Reducing Supply of Allowances Issued in Future Years. The state could employ several possible approaches to reducing the future supply of allowances. For example, the state could reduce the number of new allowances issued in future years based on a periodic assessment of whether the size of the allowance bank exceeds predetermined thresholds. This would put upward pressure on allowance prices, but make the program more stringent. CARB already has authority to make these types of changes.

- Limiting Use of Offsets. Offsets are credits generated by entities undertaking GHG emission reduction projects from sources that are not covered by the state’s cap‑and‑trade program (uncapped sources), such as forestry projects that increase or maintain carbon in the forests. Covered entities can purchase these offsets and use them (instead of allowances) to cover some of their emissions (up to 4 percent of their emissions through 2025, and 6 percent of emissions from 2026 through 2030). Offsets allow covered entities to emit at higher levels than they otherwise would, in exchange for emission reductions elsewhere, often outside of California. Limiting, eliminating, or modifying the use of offsets in the program could encourage greater emission reductions from covered entities within California. Some changes to the use of offsets would require new legislation.

- Extending the Program Beyond 2030. The current cap‑and‑trade program operates through 2030. Providing clear legislative authority for a post‑2030 cap‑and‑trade program could give covered entities more of an incentive to reduce emissions before 2030, in preparation for the post‑2030 period when the state’s emission reduction goals become more aggressive and allowances could therefore—if the program still exists—become more expensive. Although an extension would not necessarily ensure the program works as a 2030 backstop, it could increase allowance prices and encourage additional emission reductions before 2030. Whether additional legislative authority is needed for CARB to extend the program beyond 2030 currently is unclear.

A complete analysis and discussion of potential program modifications is beyond the scope of this report. However, the 2021 Annual Report of the Independent Emissions Market Advisory Committee discusses some of these options in more detail. Given the wide variety of potential modifications and the trade‑offs associated with each approach, we recommend the Legislature hold hearings in 2023 to have CARB report on the changes it is considering to the program. Specifically, as part of such hearings, we recommend directing CARB to explain how potential programmatic changes would address concerns about program stringency and help the state meet its near‑term GHG goals.

Conclusion

The Legislature has established an ambitious 2030 GHG reduction goal and tasked CARB with developing a plan for achieving this goal. Unfortunately, CARB’s updated plan lacks important details about how the state can achieve this approaching objective. Going forward, we recommend the Legislature seek additional information from the administration about the policies it plans to implement to achieve GHG targets, including potential changes to the cap‑and‑trade program that make it more consistent with the state’s 2030 goals.