LAO Contact

February 15, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

University of California

- Introduction

- Overview

- Core Operations

- Enrollment

- Capital Outlay Funding Delays

- New Transfer Requirements for UCLA

Summary

Brief Covers Governor’s Budget Proposals for the University of California (UC). This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals relating to UC’s core operations, enrollment, and certain capital outlay projects. It also analyzes a proposal to impose certain new requirements on UC Los Angeles (UCLA) relating to transfer students.

Recommend Legislature Link UC’s Base Funding Increase to Spending Priorities. The Governor’s main proposal for UC is a $216 million (5 percent) ongoing General Fund base increase—the second of five annual base increases included in his multiyear compact with UC. The Governor does not designate the base increase for any particular purposes, and the amount is not connected to UC’s identified operating cost increases. We recommend the Legislature take a more transparent budget approach by determining which of UC’s operating cost increases it wishes to support in 2023‑24 and providing funding designated for those particular purposes.

Legislature Could Revisit UC’s Enrollment Growth Funding and Targets. The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided UC with $51.5 million ongoing General Fund to grow enrollment by 4,730 resident undergraduate students in 2023‑24 over 2021‑22. UC expects to grow by 4,197 students in 2023‑24 (533 students below the target). As budget solutions, the Legislature could recognize associated General Fund savings of $8.6 million in 2023‑24 and $51.5 million in 2022‑23 (given UC expects to serve no additional students this year). We recommend the Legislature also set enrollment targets for 2024‑25, thereby helping to influence UC’s admission decisions next year. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposed $30 million ongoing General Fund to continue implementing the state’s plan to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at high‑demand campuses, opening up more slots for resident undergraduates.

Recommend Revisiting Certain UC Capital Projects. In response to the state’s projected budget deficit, the Governor proposes to delay a total of $366 million in one‑time funding for four UC capital projects until 2024‑25. Rather than delaying funding, we recommend the Legislature revisit whether to proceed with two of the projects. Those two projects (at UCLA and UC Merced) are in very early planning phases, have spent no state funds to date, lack key project information or lack justification (based on enrollment projections), and are not urgent. For the UC Riverside project, we recommend weighing it against UC’s other capital priorities. If the Legislature determines this project is the most pressing priority, we recommend it consider financing the project using university bonds. Lastly, for the UC Berkeley project, we recommend the Legislature obtain a more comprehensive project plan before proceeding, as the need for additional state funding moving forward could be considerable.

Recommend Rejecting Transfer Proposal for UCLA. The Governor proposes trailer bill language requiring UCLA to participate in the Transfer Admissions Guarantee (TAG) program and Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) program. The proposed language makes $20 million of the campus’s ongoing core funding contingent on meeting the new requirements. We recommend the Legislature reject this proposal and instead consider whether to require all UC campuses to participate in the TAG and ADT programs. We also recommend the Legislature have a broader discussion regarding whether it would like to develop a performance‑based budgeting model for UC.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on UC. UC is one of California’s three public higher education segments. In contrast to campuses at the other two segments—the California State University (CSU) and the California Community Colleges (CCC)—UC’s ten campuses are research universities. Nine of UC’s campuses enroll undergraduate, graduate, and professional school students across a range of disciplines, whereas a tenth campus enrolls graduate health science students only. Campuses offer degrees through the doctoral level. This brief is organized around the Governor’s 2023‑24 budget proposals for UC. The first section of the brief provides an overview of the Governor’s UC budget package. The remaining four sections focus on core operations, enrollment, certain capital projects, and certain transfer programs, respectively. This brief is part of our series of higher education budget analyses. The 2023‑24 Budget: Higher Education Overview was our first brief in this series.

Overview

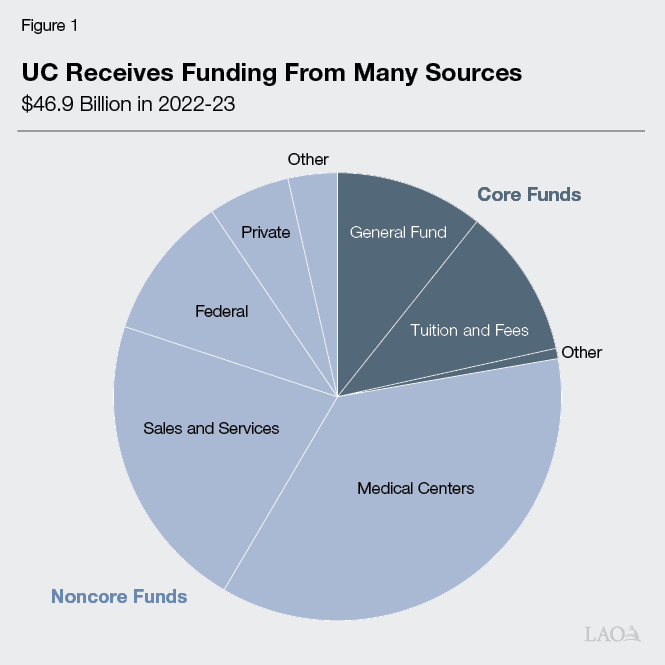

UC Budget Is $46.9 Billion in 2022‑23. Though having the lowest level of state support, the fewest campuses, and the least student enrollment, UC has the largest budget of the three public highest education segments—with total funding greater than the CSU and CCC budgets combined. As Figure 1 shows, UC receives funding from a diverse array of sources. The state generally focuses its budget decisions around UC’s “core funds,” or the portion of UC’s budget supporting undergraduate and graduate education and certain state‑supported research and outreach programs. Core funds at UC primarily consist of state General Fund and student tuition revenue. A small portion comes from other sources, such as overhead funds associated with federal and state research grants. Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, ongoing core funds per student increased 6 percent at UC.

Ongoing Core Funding Increases by $450 Million (4.6 Percent) Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 2 shows, more than half of the increase comes from the General Fund, with a smaller increase from student tuition and fee revenue. Specifically, ongoing General Fund increases by $256 million (5.9 percent), whereas tuition and fee revenue increases by $194 million (3.8 percent). In 2023‑24, tuition revenue is expected to grow both due to increases in tuition charges for certain students and enrollment growth. Under the Governor’s budget, we estimate ongoing core funding per student increases 3.1 percent.

Figure 2

Largest Portion of UC Core Fund Increase Comes From General Fund

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

General Fund |

$4,011 |

$4,374 |

$4,630 |

$256 |

5.9% |

|

Tuition and fees |

5,017 |

5,081 |

5,276 |

194 |

3.8 |

|

Lottery |

53 |

46 |

46 |

—a |

—a |

|

Other core fundsb |

207 |

301 |

301 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$9,288 |

$9,802 |

$10,252 |

$450 |

4.6% |

|

FTE studentsc |

289,913 |

288,664 |

292,891 |

4,227 |

1.5% |

|

Funding per student |

$32,036 |

$33,956 |

$35,003 |

$1,047 |

3.1 |

|

aAmount is less than $500,000 or 0.05 percent. bIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. cReflects total resident and nonresident enrollment in undergraduate, graduate, professional, and health science programs. |

|||||

|

FTE = Full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Governor Proposes Base Funding Increase for UC. Though the Legislature did not codify the Governor’s multiyear budget compact with UC, the Governor is proceeding with the second year of it. Under this compact, the Governor has agreed to propose 5 percent base funding increases for UC annually through 2026‑27. Accordingly, for 2023‑24, the Governor is proposing to provide UC with a $216 million (5 percent) ongoing General Fund augmentation. This is the largest of the Governor’s proposals for UC.

Governor Proposes Other Funding Increases and Funding Delays for UC. As Figure 3 shows, the Governor’s budget includes various other UC proposals. Notably, the Governor proposes $30 million ongoing General Fund to continue implementing the state’s plan to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at three high‑demand UC campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) by 902 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students, in turn increasing resident undergraduate enrollment on those campuses by the same amount. The appropriation backfills UC for the loss of associated nonresident tuition revenue. Beyond these additional resident slots, UC is planning for growth of approximately 4,200 resident undergraduates, to be funded from within its budget. The Governor’s budget also includes $2 million one‑time funding for UC Fire Advisors—the second consecutive year the state would be providing funding for this purpose. (As part of the state’s wildfire prevention and forest resilience efforts, it is funding UC personnel who provide information to community members on how Californians can protect homes, landscapes, and property from wildfire damage.) Beyond these funding increases, the Governor’s budget proposes delaying funding for several capital projects. Though no new state funding is involved, the administration also has a proposal requiring the UCLA campus to participate in certain transfer programs.

Figure 3

Governor Proposes Funding Increases and Funding Delays for UC

General Fund Changes, 2023‑24 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Funding Increases |

|

|

Base increase (5 percent) |

$216 |

|

Nonresident enrollment reduction plana |

30 |

|

UC Riverside medical school project (debt service) |

7 |

|

Graduate medical education |

4 |

|

Total |

$256 |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

UC Fire Advisors |

$2 |

|

Total |

$2 |

|

Funding Delays |

|

|

UCLA Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapyb |

‑$100 |

|

UC Riverside and UC Merced campus expansion projectsc |

‑83 |

|

UC Berkeley Clean Energy Campus Projectc |

‑83 |

|

Total |

‑$266 |

|

aIn 2023‑24, UC would reduce its nonresident undergraduate enrollment at three campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) by a total of 902 students. It would backfill these slots with the same number of additional resident undergraduate students. bThe state originally scheduled $200 million in 2022‑23, $200 million in 2023‑24, and $100 million in 2024‑25 for this project. The Governor now proposes to provide $100 million in 2022‑23, $100 million in 2023‑24, and $300 million in 2024‑25. cThe state originally scheduled $83 million in 2022‑23, $83 million in 2023‑24, and $83 million in 2024‑25 for these projects. The Governor now proposes to retain $83 million in 2022‑23 but delay the $83 million in 2023‑24 and provide $166 million in 2024‑25. |

|

UC Generates Additional Revenue From Tuition Increases. In July 2021, the Board of Regents adopted a new tuition policy. Under the policy, tuition is increased annually for new undergraduates and all graduate students, while remaining flat for continuing undergraduates. Tuition increases generally are based on a three‑year rolling average annual change in the California Consumer Price Index, with a cap of 5 percent. The first year of tuition increases under the new policy was 2022‑23. In 2023‑24, tuition and systemwide fee rates are set at $13,752 for new undergraduate students and $13,104 for continuing undergraduate students, reflecting a $648 (4.9 percent) increase for new students. In 2023‑24, UC estimates generating an additional $147 million in revenue from tuition increases. It plans to use $58 million of this additional revenue for institutional student financial aid. (In addition, the California Student Aid Commission budget includes $46 million in higher associated Cal Grant costs for UC students in 2023‑24. This Cal Grant cost increase is entirely offset by Cal Grant reductions associated with overall caseload.)

Core Operations

In this section, we provide background on UC’s core operating costs and how UC generally covers these costs. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed base funding increase for UC. We then assess the Governor’s proposal and make an associated recommendation.

Background

UC Has Considerable Flexibility in Managing Its Operating Costs. UC has more control than most state agencies over its operating costs. Of UC’s core‑funded compensation, more than 90 percent is associated with employees who are not represented by a labor union. The Board of Regents directly sets salaries and benefits for these employees. UC negotiates salaries and benefits with its represented employee groups. As with CSU, the Legislature does not ratify UC’s collective bargaining agreements. UC also has more control than other state agencies in that it operates its own retirement system—the UC Retirement Plan (UCRP).

UC’s Largest Operating Cost Is Compensation. As with most state agencies, UC spends the majority of its ongoing core funds (about 68 percent in 2021‑22) on employee compensation, including salaries, employee health benefits, retiree health benefits, and pensions. Beyond employee compensation, UC faces other annual costs, such as paying debt service on its systemwide bonds, supporting student financial aid programs, and covering other operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). Each year, campuses typically face pressure to increase employee salaries at least at the pace of inflation. Certain other operating costs, including health care and utility costs, also tend to rise over time in step with sector‑specific cost trends. In addition, UC is responsible for setting its pension contribution rates, and it expects to increase these rates over the next several years, primarily as a result of weaker‑than‑expected stock market performance. Though operational spending grows in most years, UC has pursued certain actions to contain this growth. For example, over the past several years, UC has achieved operational savings through changing certain procurement practices.

UC Covers Its Operating Cost Increases From Three Main Sources. In most years, the state provides additional ongoing General Fund support to cover some of UC’s operating cost increases. Since 2013‑14, the state has provided UC with General Fund base increases in all years but one. (In 2020‑21, the state reduced General Fund base support due to a projected shortfall, but it restored funding the following year.) UC sometimes supplements General Fund increases with additional systemwide tuition and fee revenue. Though it raised systemwide tuition rates only once between 2013‑14 and 2020‑21 (in 2017‑18), UC is in the midst of implementing its new tuition policy that raises systemwide tuition rates for certain students annually. Thirdly, UC relies on various alternative fund sources to help cover some of its operating cost increases. In particular, UC relies on nonresident supplemental tuition revenue and investment earnings to increase its budget capacity. In recent years, UC also has been estimating the amount of operational savings it achieves through changing certain procurement practices and other efficiencies. It has identified these freed‑up funds as an additional alternative source of support for core operations.

Share of Costs Covered by General Fund Has Been Increasing. As the state has provided UC with regular General Fund base increases and tuition charges have remained flat most years over the past decade, the General Fund has been comprising a growing share of UC’s core funds. Whereas we estimate the General Fund comprised 43 percent of UC’s ongoing core funds ten years ago, it comprises 46 percent today. Despite this increase, ongoing General Fund support per student has not kept pace with inflation since 2017‑18. Though ongoing General Fund support per student in 2022‑23 was 22 percent higher than in 2017‑18 (rising from $12,471 to $15,151) in unadjusted terms, it was 3.8 percent lower when adjusted for inflation.

Campuses Have Largely Spent Federal Relief Funds. Between March 2020 and March 2021, the federal government enacted three pieces of legislation providing COVID‑19 relief funds to higher education institutions. All associated funding was deposited into the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF) and made directly available to campuses. UC campuses received a total of $1.4 billion in HEERF funds. Of this amount, UC campuses were required to spend at least $605 million on student financial aid. Any remaining funds were available for a broad range of institutional expenses associated with COVID‑19. As of November 2022, UC campuses had spent $1.3 billion (94 percent) of the total relief funds they received. Aside from student financial aid, the largest categories of expenses were replacement of lost revenue, salaries and benefits, and information technology. Under current federal guidance, campuses have until June 30, 2023 to spend the remaining $88 million in relief funds. It is expected that campuses will be able to expend the remaining funds by this date.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Unrestricted General Fund Base Increase. The Governor proposes a $216 million (5 percent) ongoing General Fund increase for UC in 2023‑24. Budget provisional language indicates that the funds are available “to support operational costs” at UC.

Assessment

Unrestricted Base Increase Lacks Transparency and Accountability. The Governor’s proposed unrestricted base increase for UC lacks transparency, as the funds are not designated for particular purposes. Compounding this uncertainty, the Board of Regents does not adopt a corresponding spending plan until after final state budget enactment. Though UC’s fall 2022 budget request provides some indication of how UC could use the proposed funds, no statutory language requires UC to spend the base increase consistent with that preliminary plan. For all these reasons, the Legislature does not have assurance that the proposed augmentation will be spent in ways that are aligned with its priorities. Furthermore, the state has not put in place a funding formula or accountability system for UC that is akin to the one in place for CCC, which provides fiscal incentives to achieve certain outcomes. (Under the CCC Student Centered Funding Formula, community colleges effectively earn funds by achieving certain enrollment and performance outcomes.) Though the Governor’s compact describes some performance expectations, no clear mechanism exists to increase or decrease UC’s funding in response to its outcomes.

Amount of Governor’s Proposed Base Increase Is Arbitrary. The 5 percent annual base increases proposed in the Governor’s compact are not tied to projections of UC’s operating costs. Since the initial agreement was made last year, new information has become available on UC’s cost increases as well as the state’s budget condition. Each year of the compact moving forward, new information will continue to emerge. Typically, the Legislature desires to use the most recent and accurate information available to guide its budget decisions instead of relying on arbitrary increases previously proposed by the administration.

Proposed General Fund Augmentation Does Not Fully Cover UC’s Projected Cost Increases. Figure 4 shows the $406 million in 2023‑24 operating cost increases that UC identified in its fall 2022 budget plan. UC is planning for faculty and other nonrepresented staff salary increases. In addition, it already has 2023‑24 contracts in place for its represented employee groups, with most groups receiving salary increases in the range of 3 percent to 5 percent. UC’s employer contribution rate for UCRP also is set to increase by 1 percentage point, with the total employer rate rising from 15.4 percent to 16.4 percent in 2023‑24. UC projects a 4 percent increase in its health care costs for active employees and retirees. UC also projects cost increases for OE&E and debt service. Altogether, we estimate these operating cost increases exceed UC’s available core fund increases by approximately $40 million. UC indicates it would respond to any operating shortfall through operational savings and redirections of existing resources.

Figure 4

UC Has Identified Many Cost Pressures

Proposed Changes for Core Operations, 2023‑24 (In Millions)

|

Core Operations |

|

|

Faculty compensation |

$97.4 |

|

Retirement contributions |

72.7 |

|

Nonrepresented staff compensation |

69.0 |

|

Operating expenses and equipment |

55.4 |

|

Faculty merit program |

37.1 |

|

Represented staff compensation |

37.0 |

|

Health benefits for active employees |

24.3 |

|

Health benefits for retirees |

6.8 |

|

Debt servicea |

6.0 |

|

Total Cost Increases |

$405.7 |

|

Funding |

|

|

General Fund |

$252.0b |

|

Tuition and fee revenue |

58.3c |

|

Alternative fund sources |

54.6d |

|

Total Funding Increases |

$364.9 |

|

Operating Shortfall |

‑$40.8e |

|

aReflects debt service on certain academic buildings. bReflects Governor’s proposed 5 percent base increase, $30 million for nonresident enrollment reductions, and $6.5 million in higher debt‑service costs. cReflects revenue from tuition and fee rate increases net of institutional student financial aid and after accounting for the loss of nonresident supplemental tuition resulting from the nonresident enrollment reduction plan. dConsists of $30 million in investment earnings, $13.8 million in procurement savings, and $10.8 million in additional tuition revenue from nonresident enrollment growth. eReflects estimated shortfall. Assumes enrollment growth below the existing state‑funded level generates no new state costs. |

|

UC Is Likely to Face Heightened Salary Pressures in 2023‑24. Though UC already has 2023‑24 contracts in place for its represented groups, it has yet to make salary decisions for its nonrepresented faculty and staff, who comprise the vast bulk of UC’s workforce. In 2023‑24, UC is likely to face significant pressure to provide these employees with salary increases. Over the past year, both inflation and wage growth (across the nation and in California) were at their highest levels in several decades. These trends could continue into 2023‑24. The decisions UC ultimately makes in this area will affect its operating balance.

Governor’s Budget Includes No Funding for Capital Renewal. Though the Governor’s budget includes no capital renewal funding, UC requested $1.2 billion in one‑time state funds for this purpose in its fall 2022 budget request. UC estimates it needs this amount annually to keep its capital renewal backlog from growing. UC’s capital renewal backlog is currently estimated at $7.3 billion (not including seismic upgrades). UC’s backlog of projects has been growing as emerging projects outpace funding. Absent a plan to address these capital renewal needs, project backlogs very likely will continue to grow—leading to higher costs and greater risk of programmatic disruptions. (We discuss the universities’ capital renewal needs in more detail in our recent brief, Addressing Capital Renewal at UC and CSU.)

Recommendation

Build Base Increase Around Identified Operating Cost Increases. We recommend the Legislature decide the level of base increase to provide UC by considering the operating cost increases it wants to support in 2023‑24. Given the state’s projected budget deficit, we recommend considering the proposed 5 percent base increase an upper bound. With the General Fund augmentation that the Governor proposes, together with additional revenue from tuition increases and alternative fund sources, UC could cover most of its projected cost increases. However, it would need to find some savings. For example, it might consider revisiting its projected OE&E spending. UC included $55 million for projected OE&E cost increases in its spending plan, which is about $15 million more than our estimate of UC’s budget shortfall. Further downward spending adjustments would become more difficult for UC, as those reductions could begin to affect salary increases for nonrepresented employees. Though smaller salary increases likely are unpalatable, UC does not appear to be having special difficulty attracting and retaining most of its faculty and staff. For example, UC faculty salaries on average are higher than most public universities engaging in a similar level of research. In addition, faculty separations have remained about the same over the last ten years. Finally, given UC’s sizable and growing capital renewal needs, the Legislature could consider reallocating some proposed funding for this purpose.

Enrollment

In this section, we first provide background on the state’s approach to funding enrollment growth at UC. Next, we cover recent UC enrollment trends. Then, we describe the Governor’s enrollment proposals, assess those proposals, and make associated recommendations.

Background

State Typically Sets Enrollment Targets and Provides Associated Funding. Over the past two decades, the state’s typical enrollment approach for UC has been to set systemwide resident enrollment targets. These targets typically have applied to overall resident enrollment, giving UC flexibility to determine the mix of additional undergraduate and graduate students. If the overall systemwide target has reflected growth (sometimes the state leaves the target flat), the state typically has provided associated General Fund augmentations. Augmentations have been determined using an agreed‑upon per‑student funding rate derived from the “marginal cost” formula. This formula estimates the cost to enroll each additional student and shares the cost between state General Fund and anticipated tuition revenue.

Two Important Recent Modifications to State’s Enrollment Growth Approach. In recent years, the state has set enrollment growth targets only for undergraduates and has set those targets one year in advance (for example, setting a target in the 2021‑22 budget for the 2022‑23 academic year). Setting an out‑year target allows the state to better influence UC’s admission decisions, as campuses typically have already made their admission decisions for the coming academic year before the enactment of the state budget in June.

State Recently Adopted a Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Plan for UC. Recently, the state acted to limit the number of nonresident undergraduates at UC, with the intent to make more slots available for resident undergraduates at high‑demand campuses. Specifically, the 2022‑23 Budget Act directed UC to reduce incoming nonresident undergraduate enrollment at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by a total of 902 FTE students and increase resident undergraduate enrollment by the same amount. The budget act provided UC with $30 million General Fund to backfill for the loss of associated nonresident tuition revenue. If UC does not meet the reduction target, provisional language directs the administration to reduce UC’s appropriation proportional to any shortfall. The 2022‑23 actions were intended to be the first year of a multiyear plan (stretching through 2026‑27) to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at those three campuses down to no more than 18 percent of total undergraduate enrollment. (The 18 percent cap applies to all UC campuses, but only those three campuses currently are notably above the cap.) The planned reductions are spread evenly over each year of the phase‑down period.

State Set Resident Enrollment Target for 2023‑24. Specifically, the state set an expectation in the 2022‑23 Budget Act that UC grow by a total of 7,632 resident undergraduate FTE students in 2023‑24 above the 2021‑22 level. This amount consists of three components. First, it includes 4,730 additional students to be funded at a state marginal cost rate of $10,886. The budget act provided $51.5 million to fund this group of students. Second, it includes another 2,000 students (reflecting roughly 1 percent additional growth). UC is to cover the cost of these students from the base increase it receives in 2023‑24. Third, it includes 902 additional resident students due to the planned replacement of nonresident students. The cost to cover these students is to be provided through the nonresident reduction plan.

State Funded UC for Prior “Over‑Target” Enrollment. In addition to the new enrollment targets set for UC, the 2022‑23 Budget Act funded UC for students it had enrolled over previous state targets. Specifically, the budget act provided $16 million for 1,500 undergraduate FTE students UC enrolled over target from 2018‑19 through 2021‑22.

Recent Trends

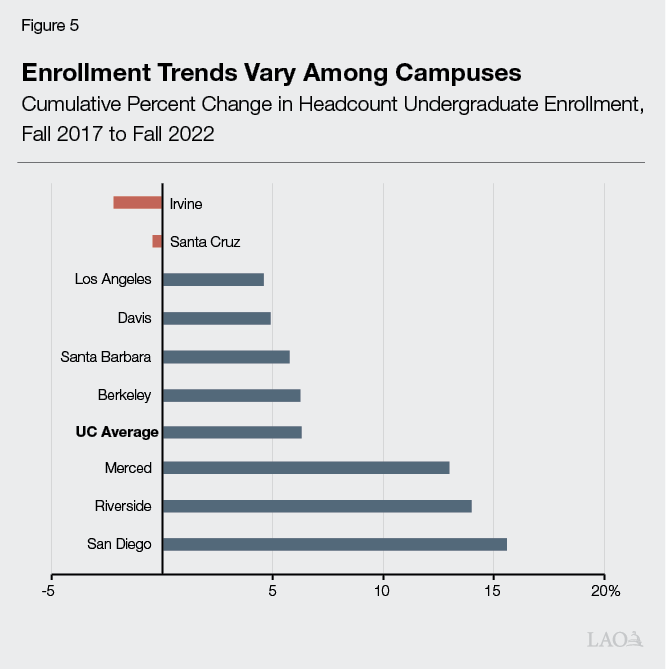

Recent Enrollment Trends Have Varied Among Campuses. As Figure 5 shows, enrollment trends varied widely among campuses over the past five years. From fall 2017 to fall 2022, the cumulative change in undergraduate students ranged from a 16 percent increase at the San Diego campus to a 2.2 percent decrease at the Irvine campus. While final 2022‑23 campus‑level data is not yet available, roughly half of campuses (Davis, Irvine, Santa Cruz, and San Diego) saw a decline in student headcount in the fall 2022 term.

UC Expects Resident Undergraduate Enrollment in 2022‑23 to Decline Slightly. Though 2022‑23 enrollment data has not yet been finalized, UC has made initial systemwide estimates based on enrollment levels in the summer and fall of 2022. UC estimates 2022‑23 resident undergraduate enrollment will be 195,597 students—263 students (0.1 percent) below the level in 2021‑22. As Figure 6 shows, UC is expecting enrollment in fall through spring terms to be up slightly, but more than offset by the enrollment drop it experienced in the summer 2022 term. The drop in summer 2022 enrollment could reflect a strong labor market, together with fewer online courses offerings compared to summer 2021. (Enrollment spiked in summer 2020 in the midst of the pandemic, likely because students had more opportunities to study online and fewer summer employment opportunities. Summer enrollment since then has declined.)

Figure 6

UC Enrollment Drop in 2022‑23 Attributable to Decline in Summer Enrollment

Resident Undergraduate Full‑Time Equivalent Students

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Fall through spring |

177,643 |

176,636 |

177,947 |

1,311 |

0.7% |

|

Summera |

22,432 |

19,224 |

17,650 |

‑1,574 |

‑8.2 |

|

Totals |

200,075 |

195,860 |

195,597 |

‑263 |

‑0.1% |

|

aSummer term is treated as the first term of a fiscal year. For example, summer 2022 is counted toward 2022‑23. |

|||||

Some Key Factors Underlie Systemwide Undergraduate Trends. Freshman enrollment the past three years at UC has been more volatile than normal—growing 1.6 percent in fall 2020, growing 11 percent in fall 2021, and falling 6.1 percent in fall 2022. UC attributes the large increase in fall 2021 to the elimination of standardized testing requirements, coupled with the suspension of the statewide eligibility index due to COVID‑19‑related grading policies. (The statewide eligibility index is a formula used by UC to determine which students are in the top 9 percent of California high school graduates.) Both of these factors, in turn, contributed to a large increase in applications. Compared to these trends, transfer enrollment is on a clearer trajectory of decline, with a decline of 1.1 percent in fall 2021, followed by a decline of 9.1 percent in fall 2022. These declines reflect the lagged effect of declines in community college enrollment the past couple of years. Regarding continuing students, retention rates are down slightly (about 1 percentage point), as is average credit load (by less than 0.5 units per term).

Graduate Enrollment Has Followed a Similar Trend as Undergraduate Enrollment. Similar to undergraduate enrollment, graduate enrollment significantly increased in fall 2021, then leveled off in fall 2022. Specifically, total graduate enrollment grew by nearly 5,000 students (7.5 percent) in fall 2021, then dropped by approximately 230 students (0.3 percent) in fall 2022. Since fall 2020, enrollment in UC’s master‑degree programs has grown the most (29 percent), followed by professional programs (11 percent). Enrollment in doctoral programs has remained about flat (down 0.2 percent). (In fall 2022, doctoral programs comprised 45 percent of UC’s total graduate enrollment, professional programs comprised 41 percent, and master‑degree programs comprised 14 percent.)

Governor’s Proposals

Governor Set Forth Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Targets Under Compact. The Governor’s compact includes a multiyear plan to expand resident undergraduate enrollment at UC. Specifically, the administration proposes that UC grow resident undergraduate enrollment by around 1 percent each year (roughly 2,000 FTE students) through 2026‑27. The top portion of Figure 7 shows the original compact enrollment targets for UC, as modified by the 2022‑23 Budget Act (which funded higher growth in 2023‑24). Under the compact, UC would not receive additional funds for enrollment growth over the period, but instead it would need to accommodate the higher costs from within its 5 percent annual base augmentations (discussed in the “Core Operations” section of this brief).

Figure 7

UC Has a Modified Enrollment Plan

Resident Undergraduate Full‑Time Equivalent Students

|

2021‑22 Actual |

2022‑23 Estimated |

2023‑24 Projected |

2024‑25 Projected |

2025‑26 Projected |

2026‑27 Projected |

Cumulative Growtha |

|

|

Compactb |

195,861 |

— |

203,493 |

205,493 |

207,493 |

209,493 |

13,632 |

|

Change over prior year |

— |

— |

7,632 |

2,000 |

2,000 |

2,000 |

— |

|

Annual percent change |

— |

— |

3.9% |

1.0% |

1.0% |

1.0% |

— |

|

UC Planc |

195,861 |

195,597 |

199,794 |

203,027 |

206,260 |

209,493 |

13,632 |

|

Change over prior year |

— |

‑264 |

4,197 |

3,233 |

3,233 |

3,233 |

— |

|

Annual percent change |

— |

‑0.1% |

2.1% |

1.6% |

1.6% |

1.6% |

— |

|

aReflects total growth from 2021‑22 through 2026‑27. bReflects compact as modified by the 2022‑23 Budget Act. Change in 2023‑24 is compared to 2021‑22 level. cReflects projected enrollment growth in 2023‑24 as identified by UC. From 2024‑25 through 2026‑27, remaining planned growth is evenly distributed. |

|||||||

Governor Also Set Forth Graduate Enrollment Targets Under Compact. In addition to resident undergraduate enrollment targets, the compact specifies that UC is to grow graduate student enrollment (resident and nonresident enrollment combined) by a total of about 2,500 students over the same time period. To meet this goal, UC plans to increase total graduate enrollment by 625 FTE students in 2023‑24. Over the remaining years of the compact, UC plans to continue growing total graduate enrollment by 625 FTE students annually—reaching the cumulative goal of 2,500 additional graduate students by 2026‑27. UC is to cover the cost of this enrollment growth also from within its 5 percent annual base augmentations.

Governor Proposes to Continue Implementing the UC Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Plan. Whereas the Governor’s budget does not earmark funding to meet the resident undergraduate or graduate enrollment targets mentioned above, it includes $30 million ongoing General Fund to continue reducing nonresident enrollment at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by a total of 902 FTE students in 2023‑24. The $30 million is intended to replace lost nonresident supplemental tuition revenue as well as lost base tuition revenue that supports financial aid for resident students. The Governor’s budget proposes to retain provisional language that would reduce this appropriation proportionally were UC to fall short of the reduction target.

Assessment

UC Is Likely to Meet 2022‑23 Nonresident Undergraduate Enrollment Target. Compared to the fall 2021 term, nonresident undergraduate headcount in the fall 2022 term declined at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by a total of 992 students. This reduction equates to 913 FTE students, which exceeds the state reduction target of 902 FTE students. Though UC exceeded the overall reduction target for the fall term, one campus reduced nonresident undergraduate enrollment only slightly. Specifically, the smallest decline occurred at the Berkeley campus (88 students), with the Los Angeles campus declining by 406 students and the San Diego campus declining by 498 students. Of the three campuses, Berkeley has the highest percentage of nonresident undergraduate enrollment (23.7 percent of total undergraduate enrollment in fall 2022). Given the Berkeley campus experienced the smallest decline in fall 2022, it will need even greater reductions over the next several years to meet the 18 percent campus cap by 2026‑27. As intended, the three campuses increased their resident undergraduate enrollment in fall 2022—growing by a combined 1,711 students, more than backfilling for the reduction in nonresident undergraduates.

2023‑24 Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target Will Most Likely Not Be Met. UC has revised its resident undergraduate enrollment plans to account for the slight drop in 2022‑23 systemwide enrollment as well as the expectation that it will not meet its budget act enrollment target for 2023‑24. As the bottom part of Figure 7 shows, UC expects to grow by 4,197 FTE resident undergraduate students (2.1 percent) in 2023‑24, short of the 7,632 FTE student target. (The 4,197 FTE students is a point‑in‑time estimate from UC, which will be refined in the coming months.) UC effectively plans to speed up growth in subsequent years—growing at 1.6 percent rather than 1 percent each year. Under this modified plan, UC would reach the ultimate compact enrollment target by 2026‑27.

Different Set of Considerations for Graduate Enrollment. In contrast to undergraduate enrollment, access has not been the primary focus of the state when deciding whether to support graduate enrollment growth. Rather, the focus has been on workforce needs—both within the UC system and in the state. Existing workforce demand likely varies for academic doctoral, academic master’s, and professional graduate students, with some graduate programs (including certain health care programs) in higher demand than others. Beyond these workforce considerations, UC campuses also often seek to grow graduate enrollment proportionate to undergraduate enrollment. This practice ensures campuses have an adequate number of teaching and research assistants to accommodate the higher level of undergraduate courses and faculty workload. Over the last five years, the ratio of total UC undergraduate students to graduate students has consistently been about five to one. The level of growth identified in the Governor’s budget is consistent with maintaining that ratio.

Legislature Has More Time to Influence 2024‑25 Enrollment Levels. As UC already is making its 2023‑24 enrollment decisions, the Legislature has less ability to influence its enrollment level that year. The Legislature could, however, send an early signal to campuses about its enrollment expectations for 2024‑25. In setting an enrollment target for 2024‑25, the Legislature likely would want to consider certain demographic, academic, and economic factors. The number of high school graduates next year, for instance, is projected to increase by 0.6 percent, potentially spurring some demographically driven growth among new students in 2024‑25. At this time, other factors such as application volume, retention rates, average unit load, and the job market are uncertain for 2024‑25.

Setting Funded Enrollment Level Is Helpful Budget Practice. Over the past few years, the state has set an enrollment growth target for UC (for example, 2,000 additional resident undergraduates), without specifying the associated total funded enrollment level (for example, a total of 202,000 resident undergraduates). Such an approach can lead to confusion and unintended consequences. This is particularly the case when the baseline level of enrollment comes in notably lower or higher than expected. Take, for example, a stylized case in which the Legislature at the time of budget enactment believes 2022‑23 enrollment will be 200,000 and provides UC enrollment growth funding to serve an additional 2,000 students in 2023‑24. If the Legislature has not specified its expectation that UC enroll a total of 202,000 students in 2023‑24, disagreements might arise. As enrollment data is finalized, if total 2022‑23 enrollment is 198,000 students, then UC might still expect to receive funding if it grows back to 200,000 in 2023‑24. The Legislature, however, might have expected UC to grow beyond its previously funded level of 200,000 students. These types of situations can be avoided if the state sets expectations regarding both enrollment growth targets and resulting funded enrollment levels.

Recommendations

Consider Adding a Budget Solution Related to Lower‑Than‑Expected Enrollment. As we discuss in The 2023‑24 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we recommend the Legislature plan for the risk of a larger budget problem by developing a larger set of potential budget solutions than the Governor has proposed. Given UC expects enrollment growth in 2023‑24 to be below the level funded in the 2022‑23 Budget Act, the Legislature may wish to consider adding an associated budget solution. Specifically, the Legislature could reduce 2023‑24 funding by $8.6 million to align with UC’s planned 2023‑24 enrollment level. (The $8.6 million in savings is based on a $10,886 state marginal cost rate for the estimated 790 student shortfall.) If the Legislature wanted to go further in aligning UC’s funding with enrollment, it also could adjust UC’s funding in 2022‑23. Specifically, it could reduce UC enrollment growth funding by $51.5 million in 2022‑23, as UC does not plan to enroll any of the additional associated students this year.

Set Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target in 2024‑25. To help influence UC’s future enrollment decisions, we recommend the Legislature set a resident undergraduate enrollment target for 2024‑25. Based the factors discussed earlier, the Legislature could consider any number of options, ranging from holding enrollment flat to funding moderate growth. Regardless of the exact growth target, we recommend the Legislature also specify an expected enrollment level for 2024‑25. Such an approach clarifies legislative intent, thereby improving transparency, and enhances accountability. Lastly, though we recommend setting enrollment targets for UC one year in advance, we recommend providing associated enrollment growth funding the same year the additional students enroll. This is because the bulk of the costs incurred to educate new students begins the year those students enroll, rather than a full year earlier.

Approve Continued Implementation of Nonresident Reduction Plan. We recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposed $30 million to continue implementing the state’s nonresident undergraduate enrollment reduction plan for UC. The proposal is consistent with state law and recent state budget actions. The nonresident enrollment reduction plan continues to serve the state’s objective of freeing up slots for resident undergraduates at high‑demand campuses.

Seek Better Information on How UC Will Cover Cost of Graduate Enrollment Growth. If the Legislature has specific workforce priorities that entail graduate enrollment growth, it could set a target for 2024‑25. That said, the Legislature could continue its current approach of not setting a graduate enrollment target if it has no specific graduate student‑related priorities. Regardless of which of these options it takes, we recommend the Legislature ask UC to provide further documentation on how it intends to cover the associated cost of enrolling additional graduate students. As graduate academic students do not tend to cover their full associated education costs, enrolling more graduate students could worsen UC’s projected operating shortfall (discussed in the “Core Operations” section of this brief).

Capital Outlay Funding Delays

In this section, we first provide background on capital outlay at UC. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed budget solutions relating to four UC capital projects. Then, we assess the package of proposed budget solutions and make associated recommendations.

Background

State Funds Academic Facilities and Infrastructure at UC. Traditionally, the state has funded UC’s academic facilities, including classrooms, laboratories, and faculty offices. It has also funded certain campus infrastructure, such as central plants, utility distribution systems, and pedestrian pathways. In addition to these state‑supported assets, UC has self‑supporting facilities, including student housing, parking structures, certain athletic facilities, and student unions. These types of facilities generate their own fee revenue, which covers associated capital and operating costs. The UC system also operates several medical centers, which provide clinical care for patients, train medical school students and residents in clinical environments, and support the university’s health science research. Most medical center funding comes from clinical revenues, primarily generated from Medi‑Cal, Medicare, and private insurance.

UC Has Identified Many Capital Projects. Under state law, UC is to submit a capital outlay plan to the Legislature annually by November 30 that identifies the projects proposed for each campus over the next five years. UC’s most recent plan (Capital Financing Plan 2022‑2028) covers the current year (2022‑23) and the next five years (through 2027‑28). This plan identifies $23.2 billion in projects proposed for this period, subject to available funding. The total amount consists of $10.2 billion in academic facilities and infrastructure projects, $6.6 billion in self‑supporting projects, and $6.4 billion in medical center projects.

State Funds UC Capital Projects in Two Ways. The main way the state funds UC’s academic facilities and infrastructure is through supporting debt‑service payments. As of 2013‑14, state law allows UC to sell university bonds to finance its academic facilities. UC uses the proceeds to cover the cost of projects, then repays the bonds over time (typically 30 years). UC may use its main General Fund appropriation in the annual state budget act, along with other available funds, to make these payments. In state law, UC may use up to 15 percent of its main General Fund appropriation for debt service on state‑approved capital projects. This debt‑financing approach is particularly common for larger projects, such as projects to renovate, replace, or construct an entire facility. A second way the state funds UC’s capital projects is by providing cash up front. Particularly when the state has a budget surplus, it can use this approach to fund deferred maintenance, seismic safety, and energy efficiency projects—projects that tend to be narrower in scope and lower in cost relative to entire renovations or new facilities.

Last Year, the State Funded Many UC Capital Projects With Up‑Front Cash. In 2022‑23, the state had a significant budget surplus. In addition, the state appropriations limit (SAL) constrained how the state could use the budget surplus. One way the state addressed its SAL requirements was by spending the surplus on purposes, such as capital outlay, that could be excluded from the limit. Specifically, the 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $366 million one‑time General Fund to UC for four specific capital projects, along with $125 million one‑time General Fund for deferred maintenance, seismic safety, and energy efficiency projects across the system.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes to Delay Funding for Four Projects. Since the enactment of the 2022‑23 Budget Act, the state budget condition has deteriorated. The state now faces a budget problem. To reduce near‑term spending, the Governor proposes to delay a total of $366 million one‑time General Fund provided for four UC capital projects until 2024‑25. Figure 8 lists the four projects, along with the associated one‑time funds that would be delayed under the Governor’s proposal. The Governor includes these funding delays as part of his overall package of solutions to address the state’s budget deficit.

Figure 8

Governor Proposes to Change Funding Schedule for Four UC Capital Projects

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Totals |

|

|

Original Funding Schedule |

||||

|

UC Los Angeles, Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy |

$200.0 |

$200.0 |

$100.0 |

$500.0 |

|

UC Berkeley, Clean Energy Campus Project |

83.0 |

83.0 |

83.0 |

249.0 |

|

UC Riverside, campus expansion |

51.5 |

51.5 |

51.5 |

154.5 |

|

UC Merced, campus expansion |

31.5 |

31.5 |

31.5 |

94.5 |

|

Totals |

$366.0 |

$366.0 |

$266.0 |

$998.0 |

|

Modified Funding Schedule |

||||

|

UC Los Angeles, Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy |

$100.0 |

$100.0 |

$300.0 |

$500.0 |

|

UC Berkeley, Clean Energy Campus Project |

83.0 |

— |

166.0 |

249.0 |

|

UC Riverside, campus expansion |

51.5 |

— |

103.0 |

154.5 |

|

UC Merced, campus expansion |

31.5 |

— |

63.0 |

94.5 |

|

Totals |

$266.0 |

$100.0 |

$632.0 |

$998.0 |

|

Difference |

‑$100.0 |

‑$266.0 |

$366.0 |

— |

Assessment

Projects Generally Do Not Address UC’s Highest Capital Outlay Priorities. Some of the capital projects identified in UC’s Capital Financing Plan 2022‑28 are critical and urgent. Those projects address deficiencies with existing facilities and infrastructure that could otherwise present life safety concerns or disrupt campus operations. In contrast, most the projects identified for delays under the Governor’s proposal do not address these types of deficiencies with existing space. Three of the four projects add new space. Moreover, adding new space increases ongoing operations and maintenance costs, and it creates future capital renewal costs as building components age. To date, UC has not provided documentation identifying how those additional costs would be covered for these new projects.

Little Information Is Available on the Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy (Institute). Based on information provided by UC, the four projects identified for delays are in early project phases. Of the four projects, the proposed Institute is in the earliest phase. According to UC, the Institute would be an independent research institute funded through a public‑private partnership and classified for federal tax purposes as a California nonprofit public benefit corporation. UCLA and the Institute founders are currently negotiating the terms of the public‑private partnership. To date, UC has spent no state (or nonstate) funds on the project. Additionally, standard project information on the scope, schedule, cost, ownership, and operations of the proposed facility have not yet been provided to the state. Without this information, the Legislature is unable to assess the project and compare it with other budget priorities. Moreover, unlike the other new projects the state funded in 2022‑23, UC did not add this facility to its Capital Financing Plan 2022‑28. While UC did identify capacity constraints for the UCLA health facilities, the Institute was not mentioned as a project to alleviate those capacity constraints.

Merced Campus Expansion Project Does Not Serve Immediate Need. UC Merced plans to add an academic facility that would provide new classrooms, faculty offices, and research space. The project remains in an early planning phase, with no state or nonstate funds spent on the project to date. The project also lacks justification at this time, as UC Merced very likely does not have the enrollment demand over the next several years to support an expansion project. UC Merced has indicated that it likely will need additional academic facility space once its enrollment reaches 12,500 students. If UC Merced continued growing at the same pace over the next five years as it has over the past five years, its enrollment would reach 10,377 students by 2027‑28, still far below the level needed to justify the expansion project.

Riverside Campus Expansion Project Has Stronger Justification. UC Riverside plans to add an Undergraduate Teaching and Learning Facility that would provide up to 78,000 assignable square feet for general assignment classrooms, specialized teaching spaces, and teaching assistant preparation spaces. UC estimates the project would add approximately 900 classroom seats. In UC’s Capital Financial Plan 2021‑27, UC Riverside listed this project as its top funding priority. UC Riverside has justification for the additional space. In UC’s most recent utilization report (using data from fall 2018), UC Riverside was using its existing classroom space at 104 percent of legislative standards and its laboratory space at 121 percent of legislative standards. Moreover, since fall 2018, total campus enrollment (headcount) has increased approximately 2,900 students (12 percent). The project is expected to address some of the campus’s existing space shortages. Though no state (or nonstate) funds have been spent on the project to date, the campus expects to encumber $6.8 million over the next several months for preliminary plans.

Many Key Details Missing for Berkeley Clean Energy Campus Project. UC’s Capital Financial Plan 2021‑27 included a $360 million state‑eligible energy project for the Berkeley campus that was not yet funded. UC’s Capital Financial Plan 2022‑28 includes the $249 million the state authorized for the project last year, but it also identifies $700 million in state‑eligible project costs not yet funded. In response to our questions, UC clarified that the project likely will entail many phases, with the total cost currently estimated at $700 million. Given the plan, it appears UC would be requesting substantial additional state funding for the project in the out‑years. It is not clear how much energy savings the campus will generate from the various phases that could offset project costs. If the campus is choosing to go beyond state clean‑energy requirements, it also raises the issue of which entity should pay for those associated costs. Furthermore, supporting such a costly project at one campus likely will create significant cost pressure for similar projects at other UC campuses, and do so at a time the state is facing projected budget deficits.

Delays Could Result in Higher Overall Project Costs. If the Legislature wanted to delay funding for any of the four projects, the overall cost of those projects likely will increase due to construction cost escalation. Construction costs in California were an estimated 9.3 percent higher in December 2022 than December 2021. This rate of increase was historically high, but some amount of construction cost escalation is expected most years, including over the next couple of years. The four affected UC capital projects are in different parts of the state, such that the exact effect of funding delays on each project’s costs very likely will vary. For example, construction cost escalation last year was 10.4 percent in Los Angeles compared to 8.4 percent in San Francisco. (This most recent variance differs from the trends over the past several decades, in which construction cost escalation tends to be somewhat higher in San Francisco than Los Angeles.)

Proposed Funding Is Not Linked to Project Milestones. Typically, the state tries to keep General Fund authorizations linked to the progress of capital projects. This approach substantially reduces programmatic and fiscal risks to the state, as important discoveries can be made in early project phases that notably affect both design and constructions costs. Linking funding to sequential project phases also facilitates legislative oversight throughout the life of a project. Under the Governor’s funding delay proposals, funding for the four UC projects is not connected to key phases. Importantly, most of the four projects likely retain substantially more funding than needed to cover the cost of reaching key milestones (such as completing working drawings or the design phase) in 2023‑24.

Recommendations

Recommend Adding Institute to Budget Solutions List. Given the deterioration in the state’s budget condition, together with projected out‑year deficits, we recommend the Legislature expand its budget solutions list by removing funding for the Institute. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature remove the entire $500 million General Fund scheduled to be provided for the Institute from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25. Given the lack of information about the project, the benefit of any smaller amount of funding for the project remains unclear. Were more information to become available about the project in future years and the project were to show stronger justification relative to UC’s other pressing capital needs, the Legislature could reconsider the project at that time, funds permitting.

Recommend Adding UC Merced Campus Expansion to Budget Solutions List. We recommend the Legislature further expand its budget solutions list by removing funding for the UC Merced expansion project given its lack of justification at this time. Specifically, we recommend removing the entire $94.5 million General Fund scheduled for the project from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25, as any smaller amount likely would be insufficient to cover proposed project costs. Were enrollment at UC Merced to grow substantially over the next several years and the campus’s existing space to reach and exceed legislative utilization standards, the campus could resubmit the project to the Legislature for funding consideration at that time.

Sweep 2022‑23 Funds for These Two Projects If Proceeding With Them. Neither the Institute nor the UC Merced project have demonstrated they will use their first round of funding in 2022‑23. Were the Legislature to decide to maintain authorization for these projects, we recommend the Legislature still sweep the associated 2022‑23 funding (and 2023‑24 funding, as the Governor proposes). Leaving large amounts of funding with projects that are not ready to use the funding raises risks and opportunity costs for the state. The state could minimize these risks and mitigate opportunity costs by better aligning funding with project phases. That is, the Legislature could provide the first allotment of funding in 2024‑25 (or thereafter) when the projects have demonstrated they could spend it.

Consider Financing UC Riverside Project With University Bonds. If the Legislature were to conclude that the UC Riverside campus expansion project is one of UC’s most pressing capital needs, it could consider debt‑financing the project, with UC selling university bonds. Most capital projects of this scale are debt‑financed, with costs effectively spread over many years consistent with a facility’s useful life. Using such an approach, the state would save a total of $154.5 million General Fund from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25. Moving forward, it could provide UC with additional General Fund to cover the associated debt service, or, as it does with most similar UC capital projects, it could have UC cover the cost from within its base budget. We estimate annual debt service on the project would be approximately $10 million. Debt‑financing a project raises overall costs substantially due to interest payments, with total project costs likely to at least double. A small portion of this increased cost, however, might be offset by proceeding with the budget in the budget year and avoiding some potential cost escalation that would otherwise occur were the project delayed.

Gather More Information About the Berkeley Clean Energy Campus Project. Before deciding what approach to take with the Berkeley project, we recommend the Legislature request UC to provide more information about the project. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature request a full financial plan for the project that, at a minimum, identifies the total state cost, total nonstate cost, annual cost by fund source by year, projected energy savings, and projected climate‑related benefits. If the Legislature concludes that UC has a sound, comprehensive financial plan for the project, it then could decide how best to finance the state share. Given the scale of the project, the Legislature could consider having UC sell university bonds. As mentioned above, this is the typical approach used for projects of this scale.

New Transfer Requirements for UCLA

In this section, we provide background on the options students have for transferring to a UC campus. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposal to place certain new transfer requirements on the UCLA campus. We then assess the Governor’s proposal and make an associated recommendation.

Background

Simplifying the Transfer Process Has Been a Longstanding Legislative Priority. The Legislature has enacted many policies over the years intended to simplify the transfer process, reduce excess course units (which often arise as a result of transferring from community colleges to universities), and reduce students’ time‑to‑degree. Toward these ends, the Legislature has directed the segments to take steps toward streamlining their lower‑division course requirements. Most recently, the Student Transfer Achievement Reform Act of 2021 requires UC, CSU, and CCC to develop a single lower‑division general education set of courses that would meet all three segments’ academic standards. (The new set of courses would apply only to general education, not major preparation. As a result, important differences still would remain among UC and CSU in terms of their transfer admission requirements.) The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $65 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund to help the community colleges in implementing the most recent round of transfer reforms.

UC Has Goal to Enroll One Transfer Student for Every Two Freshmen. For many decades, UC has aimed to achieve a certain mix of upper‑division and lower‑division students. Specifically, UC aims to have 60 percent of undergraduate instruction at the upper‑division level and 40 percent at the lower‑division level. To this end, UC aims to enroll one transfer student to every two freshmen. Over the past 15 years, UC generally has been making progress toward this goal, with its freshman‑to‑transfer ratio declining from 2.5 in 2008‑09 to 2.1 in 2021‑22.

Transfer Students Must Meet Certain Academic Criteria to Be Eligible for UC Admission. Community college students generally must complete certain UC‑transferable, lower‑division courses with a minimum grade point average (GPA) of 2.4. If a campus has more transfer applicants than slots, it uses UC’s comprehensive review policy to select students for admissions. (This process is very similar to the process used when a campus has more freshman applicants than slots.) Under comprehensive review, when reviewing an applicant, campuses may consider courses, grades, honors classes, completion of special projects, and academic accomplishments in light of the student’s life experiences, among other factors. Eligible transfer students who are not accepted to their campus(es) of choice are redirected to the UC Merced or UC Riverside campus.

Transfer Students Have Additional Options for Being Admitted to UC. One longstanding option is the TAG program. Students choosing the TAG option submit a supplemental TAG application to their UC campus of choice. As long as they meet the course and GPA requirements, they are guaranteed admission into their campus of choice. Six UC campuses participate in the TAG program, with three campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) not participating. A more recent admission option is UC Transfer Pathways. Under this option, students complete a specific set of courses in their major of choice. Pathways are offered in 20 of UC’s most popular majors. All nine general UC campuses participate in this program, though campus GPA requirements vary.

UC and CSU Transfer Pathways Are Different. UC Transfer Pathways do not have complete overlap with CSU’s transfer pathways. Many students transferring to CSU take a different pathway, which involves obtaining an ADT. The ADT was developed collaboratively between the CCC and CSU. Under the ADT process, students complete 60 units of lower‑division, major‑specific coursework at community colleges, then transfer and complete 60 units of upper‑division coursework at a CSU campus. The ADT is specifically designed to enable students to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from a CSU campus in a coordinated 120‑unit, four‑year academic program. The ADT is offered in many academic subject areas.

Compact Contains Certain UC Transfer Expectations. The Governor’s expects UC to meet a 2:1 freshman‑to‑transfer ratio. UC’s first compact progress report (released in November 2022) identified several strategies it plans to use to achieve this goal. These strategies include expanding the number of UC Transfer Pathways and expanding support programs for transfer students from underrepresented groups.

Proposal

Governor Proposes to Require UCLA to Participate in Certain Transfer Programs. The administration proposes to place certain new requirements on the UCLA campus with the goal of facilitating community college students’ ability to transfer to the campus. Specifically, by 2025‑26, the campus would need to (1) enact and maintain policies to participate in the TAG program as well as (2) create and maintain pathways for students transferring with an ADT. By March 31, 2024, the campus would need to submit a report to the Director of Finance indicating its commitment to meeting these requirements.

Governor Links Requirement With Campus’s Base Funding. The Governor does not provide a General Fund augmentation to UC for meeting the new transfer requirements at the Los Angeles campus, but he proposes trailer bill language making $20 million of that campus’s ongoing core funding contingent on it meeting the new requirements. Based upon the UC Office of the President’s determination, if the campus does not meet the new requirements, UC is to redirect the $20 million to the other nine UC campuses using its regular campus allocation model.

Assessment

UCLA Does Relatively Well on Enrolling and Graduating Transfer Students. In 2022‑23, UCLA expects to enroll approximately 3,300 new transfer students—more than any other UC campus. (UC San Diego expects to enroll the next largest group of new transfer students, approximately 2,700.) Even more importantly, UCLA has the lowest ratio of freshmen to transfer students. The UCLA ratio is 1.53—much better than the systemwide target rate of two freshmen to one transfer student, as well as notably lower than any other campus. (UC Davis has the next best ratio, 1.90.) Furthermore, transfer students at UCLA graduate at higher rates than the system overall. At UCLA, 74 percent of transfer students graduate within two years, increasing to 91 percent graduating within three years—compared to 63 percent and 85 percent, respectively, systemwide.

No Compelling Justification for Singling Out UCLA. UCLA is one of four campuses (together with Davis, Irvine, and San Diego) that already meets the compact goal of having a freshman‑to‑transfer ratio of 2.0 or below. Together with its relatively good transfer and graduation rates, the campus does not show evidence of requiring special rules to promote better transfer access or outcomes. Moreover, UCLA is not anomalous in its participation in transfer programs. Two other UC campuses do not participate in the TAG program, and no UC campus currently participates in the ADT program. UC Transfer Pathways, for which all nine UC general campuses participate, effectively are UC’s alternatives to CSU’s ADT pathways.

Governor’s Approach Sets Very Poor Policy Precedence. The Governor proposes linking base funding to a very narrow set of outcomes at a single campus. Such an approach is particularly myopic. It also is of questionable design in terms of promoting appropriate incentives. The Governor’s approach focuses solely on inputs (participating in certain transfer programs) rather than outcomes, which is counter to the basic notion of performance‑based budgeting. Moreover, the Governor’s approach violates the basic tenet of fairness in that it potentially punishes a single campus for not doing certain things, while other campuses acting in the same ways would experience no state repercussions.

Recommendation

Recommend Rejecting Proposal and Considering More Holistic Approach. For all the reasons discussed above, we recommend the Legislature reject this proposal. We recommend the Legislature consider whether it would like to require all UC campuses to participate in the TAG and ADT programs. If the Legislature is interested in pursuing these new requirements, we encourage it to coordinate with UC on how best to navigate the associated transitions. In the case of both the TAG and ADT programs, affected UC campuses would need to make important changes to their admission requirements. We also recommend the Legislature have a broader conversation regarding whether it would like to develop a performance‑based budgeting model for UC. If the Legislature is interested in linking funding to performance, we recommend it focus on a set of key expectations and apply the model to all UC campuses. As with the funding model the state uses for CCC, the Legislature could consider having both access and outcome components embedded in the model, along with further incentives to serve underrepresented students.