February 16, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

The California Department of

Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Overview

- Trends in the State Prison and Parole Populations

- Prison Capacity Reduction Proposals

- Audio‑Video Surveillance Systems

- Free Voice Calls for People in Prison

- Migration of Business Information System to Updated Software Platform

- The Joint Commission Accreditation

- Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program

- Comprehensive Employee Health Program

- Resources to Implement Recently Enacted Legislation Related to Parole and Prison Health Care

- Division of Juvenile Justice Closure

Summary

In this brief, we provide an overview of the total amount of funding in the Governor’s proposed 2023‑24 budget for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), as well as assess and make recommendations on several specific budget proposals.

Prison Capacity Reduction Proposals. The Governor proposes reductions to CDCR’s baseline funding to reflect plans to deactivate two full prisons and six yards at various prisons. Based on our review, it is not clear how CDCR weighted the various factors in selecting prisons for deactivation—making it difficult for the Legislature to determine if it agrees with the department’s selections. In addition, the department has not fully justified the 15,000 empty prison beds that it proposes to continue operating in 2023‑24 and has no plan to make further capacity reductions despite the number of empty beds being projected to reach nearly 20,000 by 2027. Without a capacity reduction plan, the state is at risk of incurring significant unnecessary costs. We recommend the Legislature take steps to gather key information from the administration to develop capacity reduction targets to inform current and future budget decisions, such as deactivating additional prisons.

Audio‑Video Surveillance Systems (AVSS). The Governor proposes $87.7 million General Fund (decreasing to $14.7 million annually beginning in 2026‑27) to (1) install and operate AVSS at ten prisons and (2) ongoing equipment replacement costs for all proposed and previously authorized AVSS and body‑worn camera systems beginning in 2026‑27. While AVSS can have benefits, the proposal has a significant budget‑year cost and would drive ongoing General Fund costs. Given that the state could be in a position to deactivate around five more prisons by 2027, there is a risk that any of the ten prisons proposed for AVSS installation would be deactivated shortly after the installation. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the $87.7 million proposed in 2023‑24 to install and maintain AVSS at ten prisons.

Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program (ISUDTP). The Governor proposes a net decrease of $28.6 million in 2022‑23 and $51 million in 2023‑24 for ISUDTP. These changes are the net effect of (1) various population‑driven adjustments based on existing methodologies and (2) a proposed increase in funding for toxicology testing based on a newly proposed methodology. We have several concerns with the budgeting methodologies for specific ISUDTP‑related resources. Given that the department indicates it will update the proposed funding for ISUDTP at the May Revision, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action and direct the department to make specific changes to the budgeting methodologies in order to better tie the level of resources requested to the department’s actual workload.

Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) Closure. To reflect the realignment of DJJ youth to counties and the closure of the division in 2023‑24, the Governor proposes to reduce DJJ’s budget to about $3 million, as well as increase CDCR’s non‑DJJ budget by $22.8 million annually. These funds would support ongoing workload related to the closure and allow the Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp to contract to accept youth from the counties. We find that portions of the requested resources are likely unnecessary and recommend reducing them. In addition, the proposed Pine Grove contracts are inconsistent with realignment because the state would be responsible for at least 93 percent of the cost of the camp, resulting in the state effectively double paying counties that choose to send realigned youth to it. Accordingly, we recommend charging a fee that minimizes the state cost for Pine Grove.

Overview

Roles and Responsibilities. CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of certain adults convicted of felonies, including the provision of rehabilitation programs, vocational training, education, and health care services. As of January 18, 2023, CDCR was responsible for incarcerating about 95,600 people. Most of these people are housed in the state’s 32 prisons and 34 conservation camps. The department also supervises and treats about 38,600 adults on parole and is responsible for the apprehension of those who commit parole violations. In addition, about 390 youths are housed in facilities that are currently operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

Governor’s Proposed Budget. The Governor’s January budget proposes a total of about $14.5 billion to operate CDCR in 2023‑24, mostly from the General Fund. This amount reflects a decrease of $454 million (about 3 percent) from the revised 2022‑23 level. (These amounts do not reflect anticipated increases in employee compensation costs in 2023‑24 because they are accounted for elsewhere in the budget.) The proposed budget would provide CDCR with a total of about 62,400 positions in 2023‑24, a decrease of about 2,400 (4 percent) from the revised 2022‑23 level. This brief provides our analysis of several of the Governor’s major proposals related to CDCR.

Trends in the State Prison and Parole Populations

Background

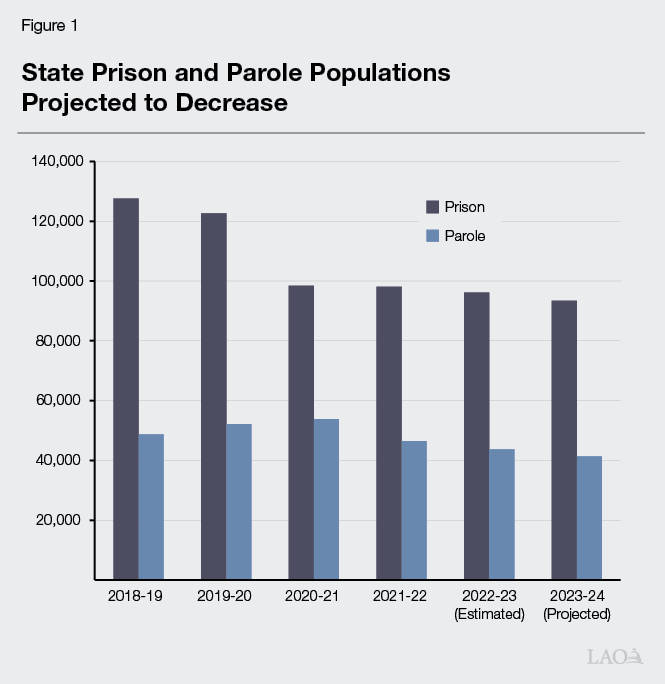

As shown in Figure 1, the average daily prison population is projected to be 93,400 in 2023‑24, a decrease of about 2,800 people (3 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The average daily parole population is projected to be 41,300 in 2023‑24, a decrease of 2,300 people (5 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The projected decrease in the prison population is primarily due to the estimated impact of various sentencing changes enacted in recent years. The projected decrease in the parole population is primarily due to recent policy changes that have reduced the length of time people spend on parole by allowing them to be discharged earlier than otherwise.

Governor’s Proposal

Net Reductions in Current‑ and Budget‑Year Population Funding. The Governor’s budget for 2023‑24 proposes, largely from the General Fund, a net decrease of $112 million in the current year and a net decrease of $259 million in the budget year related to projected changes in the overall prison and parole populations and various subpopulations (such as those housed in reentry facilities and people on parole who have convictions for sex offenses). The current‑year net decrease in costs is primarily due to both a lower total prison population and a lower portion of that population receiving treatment through ISUDTP relative to what was assumed in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. (For more on ISUDTP, please see the “Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program” section of this brief.) This decrease in costs is partially offset by a projected increase in pharmaceutical costs.

The budget‑year net decrease in expenditures is primarily due to a (1) reduction in custody staffing resulting from the planned deactivation of portions of six prisons, (2) lower total prison population, and (3) lower portion of that population receiving treatment through ISUDTP. This decrease in costs is partially offset by projected increases in pharmaceutical costs and reimbursements to local governments for costs they incurred in connection with state prisons, such as by providing coroner services.

Budget Adjustments Will Be Updated in May. As a part of the May Revision, the administration will update these budget requests based on updated population projections.

Recommendation

Withhold Recommendation Until May Revision. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision.

Prison Capacity Reduction Proposals

Background

State Currently Operating 32 State‑Owned Prisons and 1 Leased Prison. As of January 18, 2023, CDCR was responsible for incarcerating a total of about 95,600 people—91,300 men, 3,900 women, and 400 nonbinary people. Most of these people—about 91,000—are housed in 1 of 32 prisons owned and operated by the state. This includes 29 men’s prisons; 2 women’s prisons; and 1 prison that houses both men and women in separate facilities, which is Folsom State Prison (FOL) in Represa. (People who are transgender, nonbinary, or intersex are generally required to be housed in a men’s or women’s facility based on their preference.)

The state also typically houses up to about 2,400 men in a prison—the California City Correctional Facility (CAC)—leased from a private company, but operated by the state. The remaining people are housed in various specialized facilities outside of prisons, such as conservation camps and community reentry facilities.

Prisons Differ in Their Ability to Accommodate Needs of Incarcerated Population. Prisons are typically composed of multiple facilities (often referred to as “yards”) where people live in housing units, recreate, and access certain services (such as dental care). CDCR typically clusters people with similar needs (such the amount of security they require) in the same yard. Accordingly, prisons differ in their ability to meet specific needs based on the types of yards they are composed of. Some of the key needs that CDCR staff consider in matching each person with a specific prison and yard include:

- Security. CDCR categorizes most of its men’s yards into a range of security levels. (Women’s yards are not classified into different security levels as they generally have similar levels of security.) People housed in higher‑security yards live in cells, while people housed in lower‑security yards generally live in open dormitories.

- Health Care Treatment. Health care needs can affect which prisons people are housed in. For example, people with higher medical needs are typically placed at prisons designated as Intermediate Health Care institutions. This generally means that they are closer to community hospitals to facilitate access to specialty care. In addition, people receiving mental health care services are not housed at certain prisons located in desert regions of the state as they are more likely to be taking heat‑sensitive medications. Health care needs can also affect the specific yard within a prison that people are assigned to. For example, people receiving the highest level of outpatient mental health care—referred to as the Enhanced Outpatient Program—are generally housed together in dedicated yards. These yards generally include housing units with medication distribution rooms that allow nurses to prepare and distribute medications inside the housing unit to improve medication compliance. In contrast, other people are typically expected to go to a centralized medication dispensary to receive their medications.

- Other Needs. Various other factors can affect where people are housed. For example, nine prisons have restrictions to mitigate the impact of Valley Fever—an infection caused by a fungus in the soil that enters people’s lungs when inhaled. Accordingly, people who have certain medical conditions that put them at higher risk of getting very sick or dying from Valley Fever are not housed at these prisons. In addition, certain prisons do not have the necessary physical features to accommodate people in wheelchairs.

Some Prisons Fill Relatively Unique Roles. Some prisons fill relatively unique roles, which can go beyond meeting the needs of the incarcerated population. For example, Sierra Conservation Center in Jamestown serves as the primary hub for providing training and placing people in California’s conservation camps. (Conservation camps are facilities typically located off prison grounds that house eligible people who contribute to state wildfire mitigation while serving their prison term.) In addition, since 1947, all license plates issued by California have been produced by people housed at FOL.

Many State‑Owned Prisons Have Significant Infrastructure Needs. As of January 2023, CDCR identified 43 deferred maintenance or capital outlay projects across 23 prisons at an estimated total cost of $1.7 billion that are expected to be needed over the next ten years. The majority of these projects are focused on issues related to safety (such as replacement of fire suppression systems) and critical infrastructure (such as kitchen renovations). None of the projects are intended to add capacity. The estimate does not include (1) projects expected to cost less than $5 million and (2) a comprehensive assessment of prison infrastructure needs related to health care or rehabilitation. As such, it is likely that the total cost of infrastructure projects that will be needed at prisons over the next ten years could exceed $1.7 billion. (For more information on prison infrastructure, please see our February 2020 report The 2020‑21 Budget: Effectively Managing State Prison Infrastructure.)

State‑Owned Prisons Subject to Court‑Ordered Population Limit. State‑owned and operated prisons are subject to a federal court order related to prison overcrowding that limits the total number of people they can house to 137.5 percent of their collective design capacity. Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one person per cell and did not use bunk beds in dormitories. Currently, this means that the state is prohibited from housing more than a total of 112,697 people in state‑owned prisons. It also means that when prisons or yards are deactivated, this population limit is reduced by 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison or yard that was deactivated.

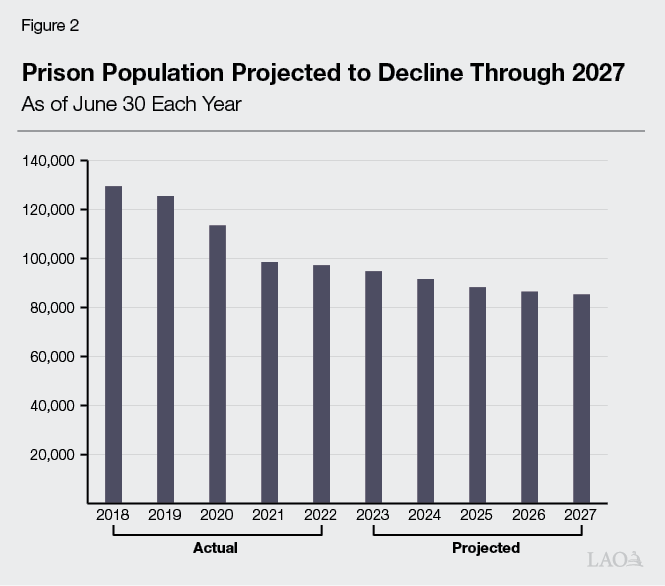

Prison Population Decline Allowing for Capacity Reductions. As shown in Figure 2, the prison population has declined significantly in recent years and is expected to remain low through June 2027. In 2021, CDCR completed a multiyear drawdown of people housed in contractor‑operated prisons made possible by the declining prison population. In addition, the administration deactivated the Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) in Tracy, as well as low‑security yards at the California Correctional Institution in Tehachapi and Correctional Training Facility in Soledad in September 2021. CDCR estimates that these deactivations resulted in ongoing General Fund savings totaling about $190 million. Deactivation also allowed the state to avoid funding infrastructure repairs that would otherwise have been needed to continue operating these facilities. For example, with the deactivation of DVI, the state was able to avoid a water‑treatment project—projected in 2018 to cost $32 million—that would have been necessary to comply with drinking water standards. Current law requires the California Correctional Center (CCC) in Susanville to be deactivated by June 30, 2023. As of January 2023, all the people who were housed at CCC have already been relocated to other prisons.

Governor’s Proposal

Deactivate Two Full Prisons and Six Yards at Various Prisons. On December 6, 2022, CDCR announced plans to deactivate CAC by March 2024 and Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (CVSP) in Blythe by March 2025. CDCR indicates that it selected CAC and CVSP for deactivation based on Penal Code Section (PC) 2067, which requires the department to accommodate projected population declines by reducing capacity in a manner that maximizes long‑term savings, leverages long‑term investments, and maintains sufficient flexibility to comply with the federal court order related to prison overcrowding. In determining how to reduce capacity, PC 2067 requires CDCR to consider certain factors, including operational cost, workforce impacts, and subpopulation and gender‑specific housing needs. In addition, the administration indicates it is proposing to deactivate CAC given that the term of the lease for the facility is nearing its end and the capacity provided by the facility is no longer needed to comply with the federal court order related to prison overcrowding.

CDCR also announced plans to deactivate six individual yards at various prisons in 2023. Figure 3 lists the specific yards that would be closed. The department indicates that it chose to deactivate yards at six different prisons—rather than one whole prison—because doing so (1) provides the department with long‑term operational flexibility to meet the changing needs of the incarcerated population, (2) likely results in less disruption to staff and incarcerated people, and (3) helps address staffing shortages.

Adjust CDCR Funding to Account for Planned Deactivations. To reflect the planned deactivations, the Governor’s budget reflects a reduction in 2023‑24 of about $280 million (largely from the General Fund) and 1,602 positions (increasing to $420 million and 2,301 positions annually beginning in 2024‑25). The ongoing reductions consist of:

- $132 million and 777 positions associated with the deactivation of CCC.

- $33 million and 166 positions (increasing to $136 million and 647 positions by 2024‑25) associated with the deactivation of CAC.

- $114 million and 659 positions (increasing to $150 million and 877 positions by 2024‑25) from the six yard deactivations.

We note that the budget maintains about $50 million and 250 positions in base funding for various purposes, such as to support staff associated with conservation camps and a limited staff at CCC to provide minimal maintenance and security services at the prison—a practice referred to as “warm shutdown.” The administration plans to submit revised savings estimates for CCC, CAC, and the six yard deactivations by the May Revision.

Continue Operating Nearly 15,000 Empty Beds. The department indicates that, while it intends to continue monitoring the issue, it is not planning further capacity reductions at this time because (1) there is a need to maintain flexibility within the system, such as having adequate quarantine space to continue managing COVID‑19 within prisons, and (2) population projections are fairly uncertain in out‑years. Accordingly, the department plans to continue to operate nearly 15,000 empty beds in 2023‑24.

Assessment

Unclear How CDCR Weighted Factors in Selecting Prisons for Deactivation

While CDCR indicates that it used the factors outlined in PC 2067 to inform its selection of prisons for deactivation, it is not clear how the department weighted these different factors. Consideration of the same factors weighted in different ways could result in different prisons being selected for deactivation. For example, if the state prioritizes operational flexibility for CDCR, CVSP could be a strong candidate for deactivation because it (1) does not provide a significant source of celled housing, (2) does not appear to fill any unique systemwide roles, (3) is not designated as an Intermediate Health Care institution, and (4) is one of the desert institutions that does not house people receiving mental health services due to the interaction with heat sensitive medications. On the other hand, if the state prioritizes operational cost savings, it might select a different prison. For example, despite housing a fairly similar population, the per capita operational expenditures of the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco were $68,250 in 2019‑20 compared to $58,101 at CVSP. Not knowing how CDCR weighted the different factors that went into its decision makes it difficult for the Legislature to evaluate whether it agrees with the department’s selections.

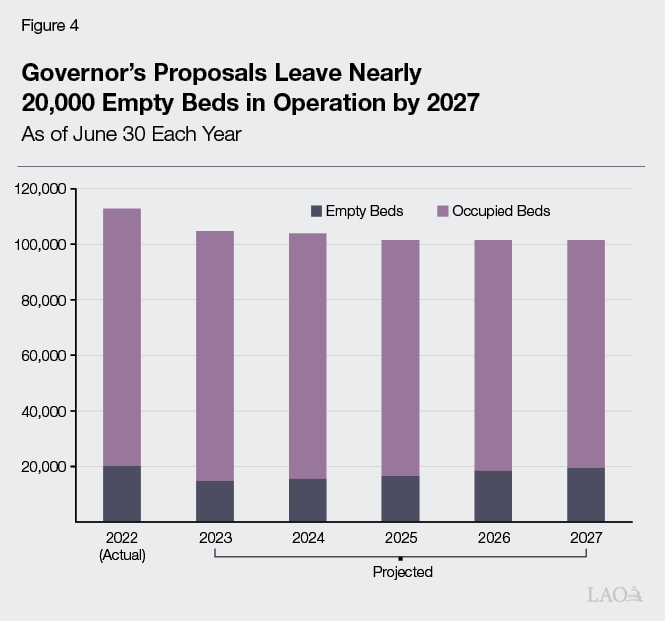

Number of Empty Prison Beds in Operation Projected to Grow to Nearly 20,000 by 2027

As discussed above, the Governor’s proposals would leave about 15,000 empty beds in the near term. As shown in Figure 4, the projected long‑term decline in the prison population suggests that, after the proposed deactivations are completed, the state could have nearly 20,000 empty prison beds—comprising about 20 percent of the state’s total prison capacity. This means that the state could be in a position to deactivate around five additional prisons by 2027, while still remaining roughly 2,500 people below the federal court‑ordered population limit.

Operation of Empty Beds Has Not Been Fully Justified

As discussed above, the state prisons are expected to have about 15,000 empty beds in the near term, growing to 20,000 by 2027. However, CDCR indicates that it is not planning further capacity reductions at this time because (1) there is a need to maintain flexibility within the system (such as having adequate quarantine space to continue managing COVID‑19 within prisons) and (2) population projections are fairly uncertain in out‑years. However, CDCR has not provided any data or analysis showing what number of beds is necessary for quarantine space. In addition, while there is always some uncertainty in population projections, the magnitude of empty beds projected is so large that it seems reasonable to assume that actual population trends will allow for some amount of capacity reduction.

State Lacks Prison Capacity Reduction Plan

Absent data and analysis demonstrating a compelling need to permanently maintain roughly 15,000 empty beds in the near term and 20,000 by 2027, the state will continue to have a substantial amount of excess capacity. Accordingly, it is reasonable for the state to start planning to reduce this excess capacity. While CDCR indicates that it will continue monitoring population trends and capacity needs, it does not have a prison capacity reduction plan. Specifically, the department has not identified the amount of empty beds it requires or how it would reduce beds in excess of this amount. As we discuss below, without a capacity reduction plan, the state is at risk of incurring unnecessary prison operational and infrastructure costs.

Unnecessary Prison Operational Costs. As the prison population declines, the state is able to spend less in certain types of costs—such as food and clothing—that are directly tied to the number of people that need to be housed in state prisons. Specifically, the state saves about $15,000 per year each time one fewer person needs to be housed in a prison. These savings accrue as the population declines—regardless of whether prison capacity is reduced. However, there are many other types of costs—such as most staffing costs—that are only saved when capacity is reduced. Specifically, when a whole prison is deactivated, the state can save several tens of thousands of dollars per capita annually in addition to the population‑driven savings. Per capita savings associated with yard deactivations are generally somewhat less. This is because, while individual yard deactivations do allow staffing levels to be reduced, prisons have many centralized staffing costs—such as for administration and perimeter security—that must be maintained regardless of the number of yards in operation. As discussed above, after the planned deactivations, the state is projected to have enough excess capacity to allow for the deactivation of around five additional prisons. Deactivation of five prisons could generate around $1 billion in annual ongoing operational cost savings. We note, however, that deactivating five prisons—or an equivalent amount of capacity reduction through a combination of prison and yard deactivations—could take a significant amount of advanced planning. For example, before the state can deactivate a facility, it might need to relocate a certain key function to another prison or make plans to mitigate the loss of that function. Without a capacity reduction plan, the state risks delaying deactivations—and the resulting operational savings—or spending hundreds of millions of dollars annually to indefinitely operate empty beds that have not been fully justified.

Unnecessary Prison Infrastructure Costs. As discussed above, state prisons have significant infrastructure repair needs—many of which must be addressed for health and safety reasons. Without a capacity reduction plan, it is difficult for the state to avoid funding projects at facilities that may be deactivated shortly thereafter. For example, as discussed in the “Audio‑Video Surveillance Systems” section of this brief, CDCR had purchased equipment for and was close to beginning installation of an audio‑video surveillance system at CVSP when the prison was announced for deactivation. In addition, CDCR completed construction of a new $31 million health care facility at CCC in July 2021—about a year and a half before all incarcerated people were relocated to other prisons. Funding infrastructure projects at prisons that are deactivated shortly thereafter is not cost‑effective. Moreover, it can mean that health and safety issues—at other prisons that the state does ultimately continue to operate—are addressed later than otherwise. Advanced planning is particularly critical given that infrastructure projects are costly and can take several years to complete.

Unnecessary Staff Training Costs. CDCR’s staffing needs are affected by various factors, including the number of facilities being operated. Correctional officer staffing needs are particularly important to plan for, given that before these staff can be assigned to a prison they must first complete a 13‑week correctional officer training academy that is paid for by the state. The Governor’s 2023‑24 budget maintains $140 million General Fund for CDCR to continue operating the academy and delivering other training to peace officers. Without a capacity reduction plan, the state risks producing more correctional officers than needed from a workload standpoint. This would not be a cost‑effective use of training resources.

Recommendations

Withhold Action on Budget Adjustments Associated With Deactivations. Given that CDCR intends to submit revised budget adjustments associated with CCC, CAC, and the six yard deactivations by the May Revision, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on these proposals. We will provide recommendations on the revised proposals when they are available.

Direct CDCR to Report on How Criteria for Deactivation Decisions Were Prioritized. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report in spring budget hearings on how it weighted the criteria that it used to identify CAC, CVSP, and the six yards for deactivation. To the extent the Legislature disagrees with how the department weighted factors, it could direct CDCR to deactivate different prisons and/or yards. Depending on the prisons or yards the Legislature ultimately decides to close, it may need to make corresponding budget adjustments relative to the Governor’s proposal.

Develop Near‑Term Capacity Reduction Target to Guide 2023‑24 Budget Decisions and Additional Deactivations. Given the risks associated with the state’s current lack of a capacity reduction plan, we recommend that the Legislature develop a near‑term capacity reduction target for the amount of capacity to be reduced in 2023‑24 through additional yard deactivations. In order to help guide the development of this target, we recommend that the Legislature take the following steps:

- Direct CDCR to Report Data and Analysis Showing Number of Empty Beds Needed in 2023‑24. As discussed above, the state prison system currently has and is projected to continue to have a significant number of empty beds. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report in spring budget hearings any available data and analysis justifying the number of empty beds that are needed in the budget year. To the extent that complete data or analysis will not be available in time to inform spring budget hearings, the administration should report on the steps and time line necessary to complete it.

- Determine Near‑Term Capacity Reduction Target. Based on the data and analysis reported by the department, we recommend that the Legislature determine a near‑term capacity reduction target. To the extent that there is significant uncertainty or gaps in the data or analysis provided by the department, this could remain a relatively conservative target.

- Direct CDCR to Deactivate Additional Yards in 2023‑24 to Meet Near‑Term Capacity Reduction Target. Because full prison deactivations can require significant advanced planning, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to deactivate additional yards in the budget year in order to meet the near‑term capacity reduction target. By deactivating yards, the state will be able to begin achieving near‑term operational savings while it finishes developing a long‑term plan—discussed below—to deactivate full prisons. Deactivating these yards does not preclude the state from reactivating them in the future as necessary. We note that the Legislature would need to make corresponding budget adjustments relative to the Governor’s proposal to reflect these additional yard deactivations and achieve General Fund savings.

Direct CDCR to Provide Information to Guide Future Budget Decisions. To guide future budget decisions and help the state avoid ongoing unnecessary spending, it is important to identify an appropriate long‑term capacity reduction target, specific prisons to be deactivated, and any planning activities—such as relocating key infrastructure—that must occur before deactivation can occur. To guide this process, we recommend that the Legislature:

- Direct CDCR to Report on Long‑Term Empty Bed Need. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to submit a report by January 10, 2024 that identifies long‑term empty bed needs and provides key information needed to plan for future prison deactivations. Specifically, the report should include thorough data and analysis supporting an estimate of the number of empty beds that the state will need to maintain in the long term. In conducting this analysis, the department should consider options—aside from maintaining empty beds—for how to manage unexpected increases in the population. The options considered should include, but not be limited to, establishing agreements with sheriffs to delay transfers from jail to prison, reducing prison terms through credits under the department’s existing authority, and the possibility of quickly reactivating yards or prisons as necessary.

- Determine Long‑Term Capacity Reduction Target. With the report described above, the Legislature will be in a better position to determine an appropriate number of empty beds to operate in the long term. Based on this, we recommend that the Legislature determine a long‑term capacity reduction target.

- Direct CDCR to Report on Major Implications of Deactivating Each Prison and Costs to Address Them. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to submit a report by January 10, 2024 that provides—for each prison or for a subset of prisons identified by the Legislature—an inventory of any major implications of deactivation and a description of the options for and cost to mitigate those implications. For example, a major implication of deactivating FOL would be that the state would have to find an alternative means of producing license plates. Accordingly, the report should briefly describe this implication, and discuss options and costs of mitigating it, such as operating the factory with civil service staff or relocating it to another prison. With this information, the Legislature would be able to weigh the costs and benefits of selecting a particular prison for deactivation. In addition, once it selects a prison for deactivation, the Legislature would be able to plan for any necessary actions to mitigate negative implications of its deactivation—such as relocating a key function.

- Achieve Long‑Term Capacity Reduction Target Through Prison Deactivation. After establishing a long‑term capacity reduction target, the Legislature would be able to estimate the number of prisons that can be deactivated over the next several years. Using information reported by CDCR on the implications of deactivating each prison, the Legislature could make decisions about which implications it is comfortable accepting and/or paying to mitigate. Moreover, given that some mitigation strategies (such as relocating critical infrastructure) could take time, having this information will allow the state to begin planning for future prison deactivations. In determining how many and which prisons to close, we recommend that the Legislature consider reactivating yards as necessary to maximize the total number of whole prison deactivations achieved. This is because, as discussed above, deactivation of whole prisons is generally more cost‑effective than similarly sized capacity reductions achieved through yard deactivations.

Audio‑Video Surveillance Systems

Background

AVSS Recently Installed at Various Prisons to Address Misconduct. Over the past several years, federal courts and the Office of the Inspector General, which provides external oversight of CDCR, have raised concerns about officer misconduct toward people in prison. For example, in fall 2016, a court monitoring team documented numerous allegations of officer misconduct, including physical abuse, denial of food, verbal abuse, tampering with mail and property, inappropriate response to suicide attempts or ideation, and retaliation for reporting misconduct. CDCR has taken various actions in response to these concerns, including installing fixed camera AVSS and body‑worn cameras on officers at various prisons. According to the department, these cameras are also used to deter and aid in investigations of other incidents, such as assaults, riots, and contraband trafficking involving people in prison. In total, the state has provided funding to CDCR for the installation of AVSS at 22 prisons and body‑worn cameras at 10 prisons. As of November 2022, AVSS has been installed at nine prisons and body‑worn cameras have been deployed at nine prisons. Currently, there are 11 state‑owned prisons that have not been funded to receive AVSS. We note that one of these prisons, CCC, is planned to be deactivated by June 30, 2023.

Governor’s Proposal

Install AVSS at Ten Prisons and Establish Ongoing Replacement Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes $87.7 million General Fund (decreasing to $7.5 million in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 and increasing to $14.7 million annually beginning in 2026‑27) and 19 positions to (1) install and operate AVSS at the ten remaining prisons not currently planned for deactivation where AVSS has not been authorized and (2) fund ongoing licensing, software, and equipment replacement costs for all proposed and previously authorized AVSS and body‑worn camera systems beginning in 2026‑27.

Proposal to Be Revised to Reflect Recently Announced Deactivations. As discussed earlier in this brief, CDCR recently announced plans to deactivate CVSP, CAC, and yards at six state‑owned prisons. At the time this announcement was made, CDCR had already purchased—but not yet installed—AVSS equipment for CVSP. CDCR indicates that it will be able to install this equipment at other prisons. Accordingly, the department plans to submit a revised proposal by the May Revision reflecting this and any other changes specifically resulting from the planned facility deactivations.

Assessment

AVSS Can Have Benefits, but Results in Additional General Fund Cost Pressures. Given that AVSS appears to be a useful investigation tool, we find that it is reasonable to install AVSS at prisons that the state intends to operate in the long term. However, the proposal has a significant budget‑year cost and would drive General Fund costs on an ongoing basis. This is notable, given the budget problem facing the state. Specifically, the Governor’s budget proposes various budget solutions to address the estimated budget problem for 2023‑24. However, our estimates suggest the budget problem is likely to be larger in May. Moreover, even under Governor’s budget assumptions, the proposed solutions also are insufficient to keep the state budget balanced in future years, with projected out‑year deficits in the $4 billion to $9 billion range.

Not Cost‑Effective to Implement AVSS at Prisons That Could Be Deactivated. As we discussed earlier in this brief, the state is expected to have significant excess prison capacity. Specifically, we estimate that the state could be in a position to deactivate around five additional prisons by 2027. However, the administration has not identified specific prisons for future deactivation. As such, under the Governor’s proposal, there is a risk that any of the ten prisons proposed for AVSS installation would be deactivated shortly after the installation—thereby the benefits of AVSS at these prisons could barely be realized.

Recommendation

Reject Portion of Funding Tied to Expansion of AVSS at Ten Prisons. Given the budget problem facing the state and the risk of installing AVSS at prisons that are deactivated shortly thereafter, we find that it is not prudent to expand AVSS to new prisons at this time. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the portion of the proposal—$87.7 million and 19 positions in 2023‑24—to install and maintain AVSS at ten prisons. When there is greater clarity as to which additional prisons will be deactivated, the administration could submit a request for resources to install AVSS at additional prisons. We note that our earlier recommendation in this brief to gather key information from the administration related to prison capacity reduction would help guide the identification and prioritization of which specific prisons to deactivate.

Free Voice Calls for People in Prison

Background

Various Ways for People in Prison to Communicate With Friends and Family. In addition to in‑person visiting and writing letters, there are various ways that people in prison can maintain contact with friends and family through electronic communication. These include voice calls, video calls, and electronic messages. Voice calls can be made from standard, hardwired telephones located at all prisons and portable tablet devices that are currently being distributed to people in prison. According to CDCR, everyone in prison will receive a tablet by June 2023. The department regulates the use of telephones and tablets among the prison population, such as the times of day when calls can be made.

Communications Contract Provides 15 Minutes of Voice Calling at No Charge. CDCR contracts with a company to provide communications services to the prison population. As a part of this contract, the company operates the telephones and tablets, which include certain security features, such as enabling correctional staff to monitor calls and restrict certain phone numbers from being called. When the contract was first initiated, the state did not pay the company as the company receives payments from users of the communications services. The current six‑year contract, which began in 2021, provides each person in prison with 15 minutes of voice calling every two weeks before any charges are levied. Under the contract, charges are levied for all electronic messages.

Charges for Time Beyond 15 Minutes Previously Paid by Friends and Family. Any time above 15 minutes is charged at a rate of 2.5 cents per minute for domestic calls and 7 cents per minute for international calls, plus applicable surcharges and taxes. Historically, these charges were paid by those receiving the calls from people in prison, such as their friends and family. However, as discussed below, the state has recently begun paying these charges.

Between July 2021 and December 2022, State Paid for Additional 60 Minutes. The 2021‑22 Budget Act provided $12 million General Fund to pay for an additional 60 minutes of voice calling every two weeks, as well as 60 free electronic messages per month, for each person in prison. This allowed each person to use a total of 75 minutes of voice calling every two weeks before their friends or family incurred any charges. Ultimately, about $2.2 million of the funding was spent in 2021‑22, with the remaining $9.8 million reappropriated in the 2022‑23 Budget Act for the same purposes. CDCR estimates that for the first part of 2022—specifically between July 2022 and December 2022—state costs for voice calling and electronic messages totaled about $1.5 million. Accordingly, the department estimates that about $8.3 million (of the $12 million originally appropriated in 2021‑22) remained available as of January 1, 2023.

Beginning January 2023, State Paying for All Additional Minutes. Chapter 827 of 2022 (SB 1008, Becker) specifies that CDCR shall provide accessible, functional voice calls free of charge. On January 1, 2023, CDCR began implementing this requirement by paying all charges accrued for voice calls. Though CDCR does not directly limit the number of minutes people can use, it does continue to restrict when calls can be made for operational reasons. CDCR intends to continue providing 60 free electronic messages per month through June 2023.

Governor’s Proposal

$5.6 Million General Fund to Pay Charges From January 2023 Through June 2023. CDCR estimates that charges for voice calling and the 60 electronic messages from January 2023 through June 2023, will total $13.9 million. The Governor requests $5.6 million General Fund—on top of the $8.3 million identified above—to pay for these charges over the six‑month period. The department indicates that it might adjust the amount it is requesting at the May Revision based on actual minute usage data.

$30.7 Million General Fund to Pay Charges and Provide Information Technology (IT) Support Annually. The Governor proposes $30.7 million ongoing General Fund and two positions to support voice calling. Of this amount, $30.4 million is expected to pay for voice calling charges. The department indicates that it might adjust this amount at the May Revision based on actual minute usage data. The remaining funding would be used to support two new IT positions to address growing workload driven primarily by the introduction of tablets and increased demand for communication services generated by Chapter 827. Beginning in July 2023, the department would no longer pay for 60 electronic messages per month. As a result, users would pay charges for these messages at the contract rate of five cents per message.

Provisional Language to Allow the Department of Finance (DOF) to Adjust 2023‑24 Funding Amount. The Governor proposes provisional language that would allow DOF to augment or reduce the 2023‑24 appropriation based on actual or estimated expenditure data. The department indicates that it believes this authority is needed given the uncertainty about how many calling minutes will be used.

Annual Budgeted Amount Modified Through a Technical Adjustment. The Governor intends to adjust annual baseline funding for calling charges as needed through a technical adjustment. Accordingly, these adjustments would not be presented to the Legislature through budget change proposals.

Assessment

Proposed Funding Appears Reasonable, but Is Based on Limited Data Currently Available. Based on calling usage data through September 2022 and analysis provided by CDCR, the funding amounts proposed to pay for calling charges in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 appear reasonable. We also think that the proposed two IT positions appear reasonable, given the growing communications‑related workload. However, by the May Revision, the department will have additional months of calling usage data. Most notably, it will have calling usage data from after January 1, 2023 when Chapter 827 went into effect. Accordingly, it is possible that the estimated funding levels could change by the May Revision.

Provisional Language Is Unnecessary and Limits Oversight. We agree that the annual funding amount needed for calling charges is subject to uncertainty, particularly in the near term given that Chapter 827 only recently went into effect and tablets are still being distributed. However, the annual budget act already includes the ability to augment funding for departments for unexpected costs. Specifically, Item 9840‑001‑0001 includes $40 million to augment departments’ General Fund budgets upon approval of the Director of DOF no sooner than 30 days after notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC). This budget item is maintained in the Governor’s proposed budget for 2023‑24. In the event that this $40 million is used for other contingencies and is unavailable to support higher than anticipated calling charges, we note that Item 9840‑001‑0001 outlines a process through which the administration can request a supplemental appropriation. Accordingly, we find that the proposed provisional language is unnecessary.

We also note that the proposed provisional language would severely limit legislative oversight, as it does not require legislative notification or approval. In contrast, augmentations through Item 9840‑001‑0001 require notification to JLBC and supplemental appropriations require approval by the Legislature.

Annual Technical Adjustment Process Lacks Transparency. We agree that the level of funding budgeted for calling charges may warrant adjustment from year to year to reflect more current usage estimates. However, we find that the proposed technical adjustment process lacks transparency. This is because, under the typical technical adjustment process, the administration does not submit documentation supporting the proposed budget adjustment. Accordingly, it would be difficult—without seeking additional information from the department—for the Legislature to identify what discretionary decisions were made, whether the funding adjustment is justified, and to conduct oversight of prison voice communications more broadly.

Going forward, it would be important for the Legislature to ensure that the level of funding provided annually is aligned to actual costs, which could be impacted by various factors, including changes in (1) the size of the prison population, (2) CDCR policies concerning when calls can be made, and (3) per‑minute costs as well as taxes and surcharges. Moreover, these factors could be affected by discretionary decisions made by the department, such as a decision to renegotiate the communications services contract. As such, the Legislature will want to ensure it has the opportunity to review the above changes and decisions.

Population Budget Adjustments Provide an Alternative Approach. In contrast to the technical adjustment process, CDCR currently uses a population budget adjustment process to propose annual adjustments to various aspects of CDCR’s budget that are tied to the size of the prison population or its subpopulations. Through this process, the administration submits documentation showing the methodology and data sources used to support the proposed adjustments, which creates transparency on the proposed adjustments.

Recommendations

Withhold Action on Proposed Funding and Require Updated Data. While the proposed funding levels appear reasonable given currently available data, the department indicates it might adjust the proposed funding levels at the May Revision based on updated data. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the proposal until that time. In addition, to ensure that the Legislature is well‑positioned to base its decision on recent data that was gathered after Chapter 827 went into effect, we also recommend directing the department to submit updated calling usage data at the May Revision.

Reject Proposed Provisional Language. Given that the proposed provisional language is unnecessary and limits legislative oversight, we recommend that the Legislature reject it. As noted above, the budget already includes Item 9840‑001‑0001 to account for unanticipated funding needs.

Direct CDCR to Annually Adjust Funding Level Through Population Budget Adjustment Process. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to adjust the level of funding for calling charges through the department’s annual population budget adjustment process. Through this process, the department would submit to the Legislature its proposed budget adjustment along with the methodology used to calculate it. For example, the department could develop a methodology that uses actual calling data from the prior year, the current per‑minute costs as well as taxes and surcharges, and projections of the size of the prison population for the coming year to estimate the amount of funding needed for the budget year. This transparency would enable the Legislature to better assess if the proposed adjustments are warranted and to provide ongoing oversight of prison voice communication more broadly.

Migration of Business Information System to Updated Software Platform

Background

CDCR Business Information System (BIS) Supported by SAP Software Platform. CDCR uses a system of interconnected IT applications—called BIS—to track and report data on various aspects of its operations. The type of software platform that the department uses to support BIS is enterprise resource planning (ERP) software and is made by the company SAP. (ERP is an industry term for software that integrates processes to help a business better manage its activities. For instance, in the case of a financial system, an ERP will enable the process of approving a purchase order to also create an accounting transaction that encumbers the funds in one step.) When CDCR began using SAP’s ERP software in 2011, BIS primarily included financial applications, which provided functions like accounting, budgeting, and procurement. Over time, CDCR has added nonfinancial applications to BIS that provide various other functions, such as those related to employee health and safety, armory tracking, and allegations of staff misconduct. CDCR currently maintains BIS with annual funding of $24 million General Fund and 61 positions.

SAP Ending Mainstream Support for Current ERP Software Beginning in 2027. In 2027, SAP is scheduled to stop providing mainstream support for the version of its ERP currently used by CDCR, which is called ERP Central Component (ECC) 6.0. This is because the company is offering a new ERP software called S/4HANA. The loss of support services could cause security vulnerabilities or loss of functionality in BIS. To prevent this from happening, the department could migrate BIS to S/4HANA by 2027. Alternatively, it is possible that third‑party vendors could provide adequate temporary support for the system. In addition, we note that information published by SAP suggests that CDCR may be able to contract with SAP to provide temporary extended maintenance past 2027.

State Centralizing Financial IT Systems Within Financial Information System for California (FI$Cal). Since 2005, the state has been in the process of replacing its aging and decentralized financial IT systems with one new system—FI$Cal, which integrates state government processes for accounting, budgeting, cash management, and procurement. In addition to eliminating the need for over 2,500 department‑specific applications, FI$Cal is intended to automate manual processes, improve tracking of statewide expenditures, provide greater transparency into the state’s financial data and management, and standardize state financial practices. FI$Cal is managed by the Department of FI$Cal.

CDCR Required to Transition to FI$Cal by 2032. Currently, all but 20 state entities have transitioned to FI$Cal. Ten of these entities, such as the University of California, have received statutory authority to use systems other than FI$Cal for their financial management on an ongoing basis. The other ten state entities, including CDCR, are currently considered deferred from FI$Cal. This means that they are currently allowed to continue using financial IT systems other than FI$Cal but are statutorily required to transition to FI$Cal to the extent possible by July 1, 2032.

Analysis to Inform CDCR Transition Expected to Be Completed by End of 2023. As a part of the planning process for transitioning a department to FI$Cal, the Department of FI$Cal works with the transitioning department to conduct a “fit‑gap” analysis. The purpose of a fit‑gap analysis is to identify the transitioning department’s existing business functions, processes, and data systems used for financial management; any gaps in the ability of FI$Cal to meet those needs; and potential options for addressing such gaps. The Department of FI$Cal indicates that it engaged with CDCR to conduct a fit‑gap analysis in 2020‑21 but the analysis was only partially completed by CDCR. FI$Cal currently expects the analysis to be completed by the end of 2023 and indicates that the specific time line to transition CDCR to FI$Cal can be evaluated at that time.

Governor’s Proposal

$8.1 Million in 2023‑24 to Begin Migrating BIS to S/4HANA. The Governor proposes limited‑term General Fund support of $8.1 million in 2023‑24, $9.3 million in 2024‑25, and $7.8 million in 2025‑26 based on CDCR’s intention to migrate BIS from ECC 6.0 to S/4HANA over three years. Specifically, the department intends to initiate migration in 2023‑24 in order to complete it before 2027 when mainstream SAP support for ECC 6.0 is scheduled to end. CDCR indicates that, pending the results of the fit‑gap analysis, it would subsequently transition the financial applications to FI$Cal.

Assessment

Initiating Migration to S/4HANA in 2023‑24 Appears Premature. Under the Governor’s proposal, the financial applications within BIS would be migrated to S/4HANA and—pending the results of the fit‑gap analysis—subsequently transitioned to FI$Cal at some point before 2032. In other words, the state would eventually be paying for both the migration to S/4HANA and the transition to FI$Cal, which does not seem cost‑effective. However, as discussed above, the state may be able to contract with SAP or a third‑party vendor to provide extended maintenance for the ECC 6.0 software supporting BIS. This would allow CDCR to delay migration to S/4HANA. Accordingly, it appears premature to begin migration at this time.

Key Information Needed to Determine Costs of Delaying Migration. In order to determine whether it is cost‑effective to delay the migration to S/4HANA, the Legislature would need to know the cost and potential trade‑offs of contracting with SAP or a third‑party vendor to temporarily provide extended maintenance for the ECC 6.0 software currently supporting BIS. However, it is unclear to what extent CDCR evaluated such options given that it did not provide information on the costs and potential trade‑offs associated with them. Without this key information, it is difficult for the Legislature to determine whether to approve the department’s proposal or delay the transition to S/4HANA. Moreover, we note that if the administration has not made efforts to assess options to delay migration to S/4HANA, it raises concerns that the administration is not putting the necessary effort into moving CDCR onto FI$Cal.

Recommendation

Withhold Action and Direct CDCR to Report Key Information. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report in spring budget hearings on (1) the annual costs to contract with SAP to continue providing maintenance, (2) the estimated annual costs to provide maintenance through a third‑party vendor, and (3) any potential challenges associated with these options and strategies to mitigate them. This information would allow the Legislature to evaluate whether the benefits of delaying migration are worth the costs. Until it receives this information, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. We will review information provided by the department and make recommendations to the Legislature after the information is available.

The Joint Commission Accreditation

Background

CDCR’s Provision of Mental Health Care Under Federal Court Oversight. In 1995, a federal court ruled in the case now referred to as Coleman v. Newsom that CDCR was not providing constitutionally adequate mental health care to the prison population. As a result, the court appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on CDCR’s progress towards providing an adequate level of mental health care. The Special Master continues to monitor and issue recommendations to CDCR for the care delivered to the prison population participating in an in‑prison mental health program, which is about one‑third of the total population. The Special Master also appoints experts to review mental health delivery processes and compliance with court‑ordered recommendations, such as experts who regularly perform in‑person audits of CDCR’s suicide prevention practices. The federal court in the case will decide when care has improved to the point where oversight through the Special Master can end. However, the court has not provided the state with specific benchmarks that must be met for court oversight to end.

CDCR’s Provision of Medical Care Under Federal Court Management. In 2006, after finding the state failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to people in prison, a federal court in the case now referred to as Plata v. Newsom appointed a Receiver to take control over the direct management and operation of the state’s prison medical care delivery system from CDCR. The Receiver’s mandate is to bring the department’s medical care program into compliance with federal constitutional standards. Unlike a Special Master, a Receiver has executive authority in hiring and firing medical staff, entering contracts with community providers, and acquiring and disposing of property.

In order for the state to regain control of the delivery of prison medical care, the state must demonstrate that it can provide a sustainable constitutional level of care at every prison. The federal court has outlined a specific process for delegating care at each prison back to the state. Specifically, each prison must first be inspected by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) to determine whether the institution is delivering an adequate level of care. The Receiver then uses the results of the OIG inspection—regardless of whether the OIG declared the prison’s provision of care adequate or inadequate—along with other health care indicators to determine whether the level of care is sufficient to be delegated back to CDCR. To date, 20 out of the 33 state‑owned and operated prisons have been delegated back to the state. However, the Plata v. Newsom court and the OIG continue to monitor and audit the delegated institutions.

Health Care Accreditations Can Provide External Oversight. Health care accreditations can provide insight into whether an organization providing care is achieving a minimum standard of care. The accreditation process uses an external, independent body that applies standardized criteria to ensure that organizations provide care consistent with the criteria. This is typically done by preparing an organization for the review process and then performing an unannounced audit of the organization’s procedures based on standardized criteria. Once accredited, an organization must continue to meet the quality standards every audit cycle to maintain its accreditation. Various agencies provide different types of accreditations designed for the specific health care service being delivered, such as medical and mental health accreditations. The Joint Commission (TJC) is one agency that accredits about 80 percent of U.S. hospitals for various types of health care services. For example, TJC issues accreditations in Behavioral Health and Human Services (covering mental health care), Ambulatory Health Care (focusing on emergency medical care), and Nursing Care Center. CDCR indicates that four prisons obtained at least one TJC accreditation and two prisons are preparing for Behavioral Health and Human Services TJC accreditation in 2023‑24 using existing resources.

Governor’s Proposal

Resources for Accreditations. The Governor’s budget proposes $3.2 million General Fund and 15 positions in 2023‑24 (increasing annually to $6.1 million and 38 positions in 2027‑28 and ongoing) to obtain and maintain TJC accreditations in Behavioral Health and Human Services, Ambulatory Health Care, and Nursing Care Center for all state‑owned and operated prisons over a five‑year period. The resources would support accreditation fees, training of staff, and ongoing positions dedicated to preparing prisons for the accreditation audits.

Assessment

Accreditations Not Required to End Court Oversight. Neither the Coleman v. Newsom or Plata v. Newsom courts have ordered the state to obtain accreditations as a way to demonstrate care has improved to a desired level or as a condition of exiting court oversight. Nor have the courts selected a specific accreditation as the most appropriate for the delivery of care in prisons. Instead, each court establishes its own requirements to determine whether care has improved to the point where court oversight is no longer necessary. As such, it is unclear whether achieving accreditations will address specific recommendations or remedial plans ordered by the courts.

Proposed Accreditation Could Unnecessarily Duplicate Oversight of Health Care. We also find that the Governor’s proposal to dedicate resources to obtain TJC accreditations at each prison could unnecessarily duplicate oversight already provided by the courts, court‑appointed experts, and OIG in the Plata v Newsom and Coleman v. Newsom cases. The state, through the OIG and state payments to court appointed experts, already dedicates resources for oversight of prison health care. It is likely that TJC would find the same deficiencies already captured by existing oversight entities, thereby not providing much additional value regarding the delivery of health care in California’s prisons.

Accreditations Are a Laudable Goal, but Exiting Court Oversight Should Be Prioritized. Attaining accreditations for CDCR’s prison health care system could have merit in the future, but achieving compliance with current court standards in order to exit court oversight should be a higher priority. This is because the state has not yet been able to fully demonstrate to the courts that adequate care is being provided at all prisons. We acknowledge accreditations could indirectly help in achieving court standards, such as if achieving accreditations requires improvements that the courts have ordered. However, the state is already aware that it needs to make these improvements. Moreover, to the extent that achieving the accreditations requires improvements that are not ordered by the courts, it would demand resources and effort that should instead be prioritized for court compliance. Dedicating resources and staff effort to address specific court orders or concerns should remain the priority until court compliance is achieved. We note that accreditation would be of greater value when the state has control over medical care as a way to help ensure the state maintains adequate care after federal court oversight ends.

Recommendation

Reject Proposal. In view of the above, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to provide CDCR resources to obtain and maintain TJC accreditations at all state‑owned and operated prisons. We find that it is more appropriate for the state to prioritize its resources and efforts for ending court oversight rather than pursuing these accreditations. We note this proposal could be considered in the future if achieving these accreditations is ordered by the courts or to ensure the quality of care is maintained once the state exits court oversight. The General Fund resources that are “freed up” under our recommendation would be available for other legislative priorities.

Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program

Background

ISUDTP Treats Substance Use Disorder (SUD) as a Medical Need. ISUDTP, initiated as part of the 2019‑20 budget, provides a continuum of care to people in prison to address their SUD and other rehabilitative needs. Prior to ISUDTP, CDCR generally assigned people to SUD treatment based on whether they had a “criminogenic” need for the program—meaning the person’s SUD could increase their likelihood of recidivating (committing a future crime) if unaddressed through rehabilitation programs. In contrast, ISUDTP is designed to transform SUD treatment from being structured as a rehabilitation program intended to reduce recidivism into a medical program intended to reduce SUD‑related deaths, emergencies, and hospitalizations. For example, as part of ISUDTP, each person leaving prison receives two doses of naloxone, a medication that can help reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. In addition, people who are part of ISUDTP are assigned to SUD treatment based on whether they are assessed to have a medical need for such treatment. For example, when people are admitted to prison, Licensed Clinical Social Workers (LCSWs) determine the appropriate level of care for those identified as having a potential SUD with the National Institute on Drug Abuse Quick Screen. Similarly, for those within six months of release from prison, LCSWs administer an SUD assessment that identifies other needs necessary to facilitate transition into the community.

ISUDTP Expanded Availability of Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT). People who are addicted to certain substances (such as opioids or alcohol) can develop a chemical dependency. This can result in strong physical cravings, withdrawal that interferes with treatment, and/or medical complications. MAT is intended to combine SUD treatment services (such as cognitive behavioral therapy, a type of therapy which helps change negative patterns of behavior) with medications designed to reduce the likelihood of people relapsing while undergoing SUD treatment. Prior to 2019‑20, CDCR had operated MAT pilot programs at three prisons. Under ISUDTP, MAT was made available at all prisons to targeted groups starting in 2019‑20.

Toxicology Testing Used When Receiving MAT. Toxicology testing is the process of collecting samples from a person to test for the presence of toxins, poisons, or substances, including illegal substances. Regular testing is important for those receiving MAT. Toxicology results can be used for various purposes, such as to determine a baseline level of toxins in the body before people receive MAT, monitor their adherence to treatment, adjust the dosage level of medications, and determine whether people are continuing to use substances.

ISUDTP Expanded in 2022‑23. ISUDTP was expanded through the 2022‑23 budget, which brought total current funding for the program to $291.4 million General Fund and 740.6 positions, increasing to $327.9 million in 2023‑24. As part of the ISUDTP expansion, the department indicated that it would annually propose both current‑ and budget‑year population‑driven adjustments to the program’s resources. This means the level of funding would be adjusted based on changes in the population affecting ISUDTP workload, such as changes in the MAT patient population. Population‑adjusted resources include those for medications used for MAT and toxicology tests. They also include adjustments to staffing levels for various classifications, such as LCSWs as well as Licenses Vocational Nurses (LVNs), Pharmacists, and Pharmacy Technicians involved in dispensing MAT medications. Accordingly, the $291.4 million in the 2022‑23 budget and the planned $327.9 million for 2023‑24 would be adjusted to account for population changes.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor proposes a net decrease of $28.6 million in 2022‑23 and $51 million in the 2023‑24 for ISUDTP relative to the planned amount when the 2022‑23 budget was adopted. This would bring total funding for ISUDTP to $262.8 million in 2022‑23 and $276.8 million in 2023‑24. These changes are the net effect of (1) various population‑driven adjustments based on existing methodologies and (2) a proposed increase in funding for toxicology testing based on a newly proposed methodology. As a part of the May Revision, the department will update these budget requests based on updated spring 2023 population projections.

Population‑Driven Adjustments Based on Existing Methodologies. The Governor proposes various population‑driven adjustments to ISUDTP based on existing methodologies that result in a decrease in funding of $41.6 million General Fund and 51.6 positions in 2022‑23 and $65 million General Fund and 105.4 positions in 2023‑24. These changes consist of:

- Adjustments Based on MAT Patient Population. Most of the adjustments are due to the MAT patient population being projected to be about 15,500 in the current year and about 16,600 in the budget year rather than 25,500, as was previously projected for both years. For example, the department proposes reducing funding for MAT medications by $16.6 million in current year and $23.1 million in the budget year.

- Adjustment to LVNs Based Partially on MAT Patient Population. The LVN positions are only partially adjusted based on the MAT patient population. Specifically, the department receives 1.77 LVNs per 225 MAT patients unless this adjustment would result in the department receiving less than 139.8 LVN positions, in which case the number of LVNs remains at 139.8—equivalent to the number of LVNs required to distribute MAT medications to 17,717 patients. The department indicates that it must retain these 139.8 positions even if the MAT patient population is below 17,717 in order to effectively distribute both MAT medications for ISUDTP and other medications not part of ISUDTP. Given that the MAT patient population is projected to be below 17,717 in both the current and budget year, the department proposes to retain 139.8 LVN positions in both years. This reflects a reduction in both the current and budget years of 62 LVN positions. We note that the department indicated that it might revise this budgeting methodology in the spring.

- Adjustments Based on MAT Patient Population and Other Factors. Some of the ISUDTP adjustments are based both on the number of MAT patients and other factors. For example, the number of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians is adjusted based on calculations incorporating the MAT patient population and other factors, such as the MAT inventory (referred to as Omnicell Count). Based on changes in these factors, the department is requesting an increase of 2.3 additional Pharmacists in the current year and 1.9 Pharmacists in the budget year. In addition, the department is requesting to reduce the number of Pharmacy Technicians by 6.5 in the current year and 10.2 in the budget year.

- Adjustments Based on Factors Other Than the MAT Patient Population. Several adjustments are based on factors other than the MAT patient population. For example, the level of funding for naloxone and the number of LCSWs is based on the historical number of admissions to and releases from prison each month. Specifically, based on an assumption that there will be an average of 3,000 monthly prison admissions and releases, the department is proposing an increase of 13.5 LCSWs in the current year and a reduction of 0.5 LCSWs in the budget year. However, the department is not proposing a change in funding for naloxone in either year as its existing funding for the medication is sufficient, despite changes in prison admissions and releases.

Resources for Toxicology Testing Based on New Methodology. The 2022‑23 budget provided sufficient resources to conduct ten toxicology tests per MAT patient per year. However, the administration is proposing to change the methodology to increase the number of toxicology tests per MAT patient to 14 per year going forward to reflect actual testing data. Accordingly, the budget proposes an increase of $13 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and $13.9 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to provide ISUDTP with sufficient resources to conduct 14 toxicology tests per MAT patient annually on a permanent basis. According to the department, the permanent 14 toxicology tests rate per MAT patient is necessary given that the MAT program has been ramping up significantly, which has resulted in a corresponding increase in toxicology testing being observed. Moreover, CDCR indicates that a higher number of toxicology tests per MAT patient have been used because more testing is necessary in the initial stages of treatment.

Assessment

LVNs Requested Not Solely Based on ISUDTP Workload. Under the department’s current methodology for budgeting LVNs, LVNs positions are not reduced despite the MAT patient population being less than 17,717. According to the department, this is because LVNs have to distribute both MAT‑related medications for ISUDTP and other medications not part of ISUDTP. This suggests that LVN positions budgeted through ISUDTP have workload outside of ISUDTP. This is problematic because LVN workload outside of ISUDTP is already funded elsewhere in the health care budget—resulting in the department receiving more funds than necessary to complete the workload.

Unclear Justification for Adjustment Proposed for Pharmacy Positions. The Governor proposes to adjust the number of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians based on calculations incorporating the MAT patient population and various other factors, such as the Omnicell Count. However, the department has not provided sufficient information on how these factors are used to calculate the number of positions needed. For example, it is unclear why, despite a decrease in the number of MAT patients and MAT medications, there would be an increase in the need for Pharmacists. Accordingly, it is unclear whether the number of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians proposed is justified.

Request for LCSWs and Naloxone Inconsistent With Recent Data on Admissions and Releases. As discussed above, the need for LCSWs and naloxone is based on a projection that there will be 3,000 monthly admissions and releases in both the current and budget year. This is roughly consistent with the number of admissions and releases that have occurred historically. However, this assumption is inconsistent with more recent data. For example, data from the department indicates that in 2022, an average of 2,400 people were admitted and 2,700 people were released from prison each month. This is 600 fewer admissions (or 20 percent) and 300 fewer releases (or 10 percent) than assumed in the Governor’s proposal. This suggests that the department is requesting more resources than it needs in the current and budget year for LCSWs and naloxone.

Budgeting Toxicology Testing Based on Current Frequency Could Be Flawed in the Future. Given that data on the number of toxicology tests used per MAT patient suggests the department needs to be budgeted for 14 rather than 10 tests annually, we do not have concerns with increasing funding for such tests in the current and budget year. However, we find that it could be problematic in the future. Although the current rate of toxicology testing for those on MAT is higher than anticipated, it is possible that, as patients spend more time in the MAT program, the need for toxicology testing could decrease as the department indicates patients in the initial stages of treatment need more testing. Accordingly, the assumption that the average MAT patient needs 14 toxicology tests annually could be flawed in future years.

Recommendations

Withhold Action. Given that the department indicates it will update the proposed funding for ISUDTP at the May Revision, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action until that time. We will advise the Legislature on the revised proposal when it is available.

Direct Department to Make Specific Changes to Methodology Used for Revised and Future Proposals. Based on our analysis, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to make specific changes to the budgeting methodology for LCSWs, naloxone, and LVNs both for the revised spring proposal and future proposals. Specifically, we recommend the department (1) base requests for LCSWs and naloxone on either updated projections of or recent data on the number of admissions and releases each year rather than a historical rate and (2) develop a methodology—that does not include other workload that is not ISUDTP related—to base the number of LVNs requested for ISUDTP. To the extent the recommended changes result in insufficient LVNs for other workload, the department could present a separate proposal justifying the need for such LVNs. These changes would better tie the level of resources requested to the department’s actual workload.

Direct the Department to Provide Sufficient Justification for Pharmacy‑Related Positions. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide sufficient information explaining and justifying its budgeting methodology for Pharmacists, and Pharmacy Technicians at budget hearings. This information would help the Legislature to review the revised spring proposal when it becomes available and to determine whether the budgeting methodology for these positions needs to be revised.

Annually Adjust Resources for Toxicology Testing Based on Actual Usage and MAT Projections. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to adjust the level of funding to administer toxicology tests in future years based on the projected MAT patient population and the average testing rate in the most recently completed prior year. For example, for the 2024‑25 fiscal year, this means basing funding for toxicology testing on the 2024‑25 projected MAT population and the average number of tests per MAT patient administered in 2022‑23.

Comprehensive Employee Health Program

Background