LAO Contact

February 28, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

- Introduction

- Overview of CDCR Prison Infrastructure

- Major Drivers of Prison Infrastructure Needs

- State Lacks Plan to Manage Prison Infrastructure

- Road map for Developing a Prison Infrastructure Plan

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

State Owns and Operates 34 Prisons. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) operates and maintains 34 prisons, which contain extensive amounts of infrastructure essential to prison operations, including health care facilities, firehouses, and waste water treatment plants. Twelve of these prisons were originally constructed between the 1850s and 1960s, with the remaining 22 being built from 1980 through 2013. We note that to reduce prison overcrowding, the state also houses inmates in beds outside of the 34 state‑owned prisons such as contracted prisons.

Significant Infrastructure Needs Throughout Prison System. CDCR reports significant infrastructure needs throughout the system that could cost billions of dollars to fully address. The major factors that drive prison infrastructure needs and spending include:

- Prison Age and Condition. One of the most significant factors driving prison infrastructure needs and spending is the age and condition of the state’s existing facilities. A recent study found that infrastructure at the state’s 12 oldest prisons has generally exceeded its expected useful life and recommended over 150 infrastructure projects totaling over $11 billion.

- Size and Housing Needs of Inmate Population. The size of the inmate population and various subpopulations—such as the number of inmates that require high security housing—also drive infrastructure needs. In recent years, the state’s inmate population has declined—and is expected to continue to decline in the next few years—primarily due to the implementation of various policy changes, such as Proposition 57 (2016). In order to accommodate the ongoing decline in the inmate population, the Governor has raised the possibility of closing a prison within the next five years after inmates are removed from publically operated contract prisons.

- Inmate Services. The types of services the state provides to inmates such as health care and rehabilitation programs have driven—and continue to drive—major infrastructure expenditures.

Recommended Road Map for Developing a Prison Infrastructure Plan. Given the age and condition of the state’s prison facilities and the continued decline in the inmate population, the state will have to prioritize future infrastructure spending and reevaluate the number of prisons it operates. However, the state currently lacks a prison infrastructure plan to guide its decisions both in the near term and long term. Accordingly, we provide in this report a road map to guide the Legislature in the development of a plan for managing prison infrastructure.

Specifically, we recommend the following key steps:

- Direct CDCR to Close Two Prisons. We recommend closing two prisons, rather than removing inmates from publically operated contract prisons and closing one prison as the Governor proposes. This is because prioritizing prison closure would reduce the risk of infrastructure‑related emergencies and litigation, as well as achieve additional state savings. In order to guide the identification of prisons for closure, we recommend the Legislature direct CDCR to rank prisons for closure based on cost avoidance, operational needs, and their ability to serve inmates. This would allow the Legislature to avoid approving unnecessary infrastructure projects at prisons that could be closed. We also recommend requiring the department to submit a detailed prison closure plan.

- Require CDCR to Develop a Strategy to Improve Infrastructure. We recommend the Legislature require CDCR to create a strategy to improve the infrastructure at the remaining prisons. This includes developing a list of significant, high‑priority infrastructure projects that should be accomplished over the next ten years. In developing this list, CDCR should consider certain criteria, such as the possibility of further prison closures and various alternatives to repairing existing facilities. The department should also develop a project priority order and time line that prioritizes addressing infrastructure needs that threaten inmate and staff well‑being, as well as opportunities to reduce construction and operational costs.

Following our recommended road map would allow the state to more effectively and efficiently address the continued decline in the inmate population and the significant repairs needed at many of its prisons.

Introduction

The state owns and operates 34 prisons, which contain extensive amounts of infrastructure that are essential to its operations, including health care facilities, firehouses, and waste water treatment plants. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), which is responsible for maintaining the prisons, reports significant infrastructure needs throughout the system that could cost billions of dollars to fully address. Despite this, the state currently lacks a plan to strategically manage and address the needs of its prison infrastructure. The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 proposes $103 million in additional General Fund support and $91 million in new lease revenue bond authority for various projects to address some of the infrastructure needs at certain prisons. In presenting his budget plan to the Legislature, the Governor also raised the possibility of closing a prison within the next five years to accommodate the ongoing decline in the inmate population. Given the magnitude of the state’s prison infrastructure needs, combined with the possibility of closing a prison in the near future, it will be important for the state to think strategically about managing its prison infrastructure—both in the near term and long term. In this report, we (1) provide an overview of the state’s prison infrastructure, (2) discuss the major drivers of prison infrastructure needs and spending, and (3) provide a road map to guide the Legislature in the development of a plan to strategically manage the state’s prison infrastructure.

Overview of CDCR Prison Infrastructure

State Owns and Operates 34 Prisons. As of February 5, 2020, CDCR was responsible for a total of 123,500 inmates—118,000 male inmates and 5,500 female inmates. The majority of these inmates are housed in one of 34 prisons owned and operated by the state—31 for males, 2 for females, and 1 (Folsom State Prison in Represa) that houses both male and female inmates in separate facilities. (We note that the state also leases a prison facility—the California City Correctional Facility—from a private entity that it operates with state staff.) As shown in Figure 1 (see next page), 12 of these prisons were originally constructed between the 1850s and 1960s with the remaining 22 being built from 1980 through 2013. While many prisons are designed for a range of different inmates and functions, some prisons have specialized missions that are critical to providing specific services. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the California Medical Facility (CMF) in Vacaville and California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton specialize in providing medical and mental health treatment to inmates who have the most severe and long‑term needs. In addition, the California Correctional Center in Susanville and the Sierra Conservation Center in Jamestown are responsible for training inmates in firefighting techniques before they are placed into one of 39 male conservation camps located throughout the state, which are generally jointly operated by CDCR and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Figure 1

California’s 34 State‑Owned Prisons

|

Prison |

Year Opened |

Special Missiona |

Design Capacity |

Number of Inmatesb |

|

San Quentin State Prison |

1852 |

Mental Health |

3,082 |

4,070 |

|

Folsom State Prison (Represa) |

1880 |

Medical Care |

2,469 |

3,271 |

|

California Correctional Institution (Tehachapi) |

1933 |

High Security |

2,783 |

3,700 |

|

California Institution for Men (Chino) |

1941 |

Medical Care |

2,976 |

3,551 |

|

Correctional Training Facility (Soledad) |

1946 |

— |

3,312 |

5,078 |

|

California Institution for Women (Corona) |

1952 |

Medical Care, Mental Health |

1,078 |

1,615 |

|

Deuel Vocational Institution (Tracy) |

1953 |

— |

1,681 |

1,997 |

|

California Medical Facility (Vacaville) |

1955 |

Medical Care, Mental Health |

2,361 |

2,510 |

|

California Men’s Colony (San Luis Obispo) |

1961 |

Medical Care |

3,838 |

3,756 |

|

California Rehabilitation Center (Norco) |

1962 |

— |

2,491 |

3,846 |

|

California Correctional Center (Susanville) |

1963 |

Conservation Camps |

1,733 |

4,081 |

|

Sierra Conservation Center (Jamestown) |

1965 |

Conservation Camps |

1,726 |

4,370 |

|

California State Prison, Solano (Vacaville) |

1984 |

Medical Care |

2,610 |

4,276 |

|

California State Prison, Sacramento (Represa) |

1986 |

Medical Care, High Security |

1,828 |

2,339 |

|

Avenal State Prison |

1987 |

— |

2,920 |

4,228 |

|

Mule Creek State Prison (Ione) |

1987 |

Medical Care |

3,284 |

4,005 |

|

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility (San Diego) |

1987 |

Medical Care |

2,992 |

3,860 |

|

California State Prison, Corcoran |

1988 |

High Security |

3,116 |

3,014 |

|

Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (Blythe) |

1988 |

— |

1,738 |

2,770 |

|

Pelican Bay State Prison (Crescent City) |

1989 |

High Security |

2,380 |

2,632 |

|

Central California Women’s Facility (Chowchilla) |

1990 |

— |

2,004 |

2,819 |

|

Wasco State Prison |

1991 |

— |

2,984 |

4,610 |

|

Calipatria State Prison (Calipatria) |

1992 |

— |

2,308 |

3,094 |

|

California State Prison, Centinela (Imperial) |

1993 |

— |

2,308 |

3,461 |

|

California State Prison, Los Angeles County (Lancaster) |

1993 |

Medical Care, High Security |

2,300 |

3,214 |

|

North Kern State Prison (Delano) |

1993 |

— |

2,694 |

4,446 |

|

Ironwood State Prison (Blythe) |

1994 |

— |

2,200 |

2,896 |

|

Pleasant Valley State Prison (Coalinga) |

1994 |

— |

2,308 |

3,153 |

|

High Desert State Prison (Susanville) |

1995 |

High Security |

2,324 |

3,181 |

|

Valley State Prison (Chowchilla) |

1995 |

— |

1,980 |

3,002 |

|

Salinas Valley State Prison (Soledad) |

1996 |

High Security, Mental Health |

2,452 |

2,917 |

|

California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility (Corcoran) |

1997 |

High Security |

3,424 |

5,281 |

|

Kern Valley State Prison (Delano) |

2005 |

High Security |

2,448 |

3,541 |

|

California Health Care Facility (Stockton) |

2013 |

Medical Care, Mental Health |

2,951 |

2,848 |

|

aMental health means prison has a psychiatric in‑patient program. Medical care means prison is classified as an intermediate care facility. High security means prison is assigned to high security mission by department. Conservation camps mean prison’s primary mission is training inmates in firefighting techniques. bAs of February 5, 2020. |

||||

Infrastructure Is Critical to Prison Operations. CDCR is responsible for maintaining the state’s 34 prisons, which collectively consist of about 5,000 buildings covering over 42 million square feet and contain over 22,000 individual pieces of equipment and utility systems. As 24‑hour institutions responsible for the daily care of thousands of inmates, prisons rely on a wide range of infrastructure, such as industrial kitchens, boilers, electrical generators, and waste water treatment plans. Infrastructure failure—such as damaged roofs or failed smoke detection systems—can pose significant health and safety risks to inmates and staff. Prison infrastructure also affects the state’s ability to deliver services to inmates, such as health care and rehabilitation programs. For example, a lack of sufficient classrooms can make it difficult for prisons to provide inmates with rehabilitative treatment. Accordingly, the annual state budget includes funding for CDCR to maintain its prison facilities. The 2019‑20 budget includes $182 million for deferred maintenance projects at various prisons and $56 million for CDCR to conduct preventative maintenance at all facilities.

Major Drivers of Prison Infrastructure Needs

In this section, we describe the major factors that drive prison infrastructure needs and spending. These include (1) age and condition of each prison, (2) the size and housing needs of the inmate population, and (3) the types and levels of services that the state provides to inmates.

Prison Age and Condition

One of the most significant factors driving prison infrastructure needs and spending is the age and condition of the state’s existing facilities. As previously discussed, 12 of the state’s prisons were built in the 1960s or earlier—including some that are more than a century old. We note that the state’s other 22 prisons also have significant and growing needs.

12 Oldest Prisons Have Significant Infrastructure Needs

Study Found Oldest Prisons Have Generally Exceeded Expected Useful Life. The 2016‑17 Budget Act provided CDCR with $5.4 million to hire a consultant to (1) assess the infrastructure conditions at the 12 prisons that were originally constructed between the 1850s and 1960s and (2) recommend specific projects necessary to maintain their current operations for the foreseeable future. The resulting study, which was recently completed, found that most of the buildings and building systems date to their original construction. Accordingly, they have generally exceeded their expected useful life and are often not consistent with current building code requirements, such as having fire sprinklers and adequate ventilation in kitchens. Many pieces of infrastructure were found to be failed or at risk of failure. For example, the study found inoperable fire alarms in housing units and failed emergency generators, and noted that most of the electrical systems at one prison were in such poor condition that they could fail at any time. The study also found infrastructure prone to frequent breakage. For example, one prison’s gas distribution system leaks multiple times per year.

In some cases, the infrastructure is so outdated that replacement parts cannot be purchased and must be specially manufactured by prison maintenance staff. These frequent and complicated repair needs drive increased ongoing maintenance costs. In other cases, maintenance staff are more limited in their ability to repair damaged infrastructure. For example, the study noted that (1) several building systems cannot be repaired without disturbing asbestos insulation, (2) some prison roofs are so waterlogged that it can be difficult for staff to walk on them when making repairs, and (3) some prison windows are covered with security bars and mesh that prevent staff from repairing them.

Study Recommended Over $11 Billion in Repairs. The study recommended over 150 specific infrastructure improvement projects across the state’s 12 oldest prisons. The study identified which pieces of infrastructure to rebuild—rather than simply repair—by comparing the cost of repairs to the cost of rebuilding. In cases where the cost of repair was 65 percent or more of the cost of replacement, the study generally recommended replacement as a more cost‑effective approach to repair. Accordingly, some of the recommended projects involve rebuilding significant portions of prisons. The study also generally recommended repairing or replacing systems in buildings critical to prison operations if they were nearing or past the end of their expected useful life. (Please see the box on page 7 for additional information regarding the methodology used by the consultant in preparing the study.) As shown in Figure 2, the estimated cost to complete all of the recommended projects is about $11 billion. The consultant is expected to provide a final report in spring 2020 that will include a recommended statewide prioritization of projects.

Figure 2

Recent Study Recommended Over $11 Billion in Projects at 12 Oldest Prisons

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Prison |

Estimated Cost of Recommendations |

Number of Projects |

|

San Quentin State Prison |

$1,647 |

11 |

|

California Men’s Colony |

1,557 |

12 |

|

Correctional Training Facility |

1,318 |

26 |

|

California Institution for Men |

1,228 |

26 |

|

California Rehabilitation Center |

1,116 |

7 |

|

Deuel Vocational Institution |

804 |

13 |

|

Folsom State Prison |

800 |

11 |

|

Correctional Medical Facility |

763 |

10 |

|

California Correctional Institutiona |

531 |

16 |

|

Sierra Conservation Center |

504 |

9 |

|

California Correctional Center |

503 |

10 |

|

California Institution for Women |

413 |

8 |

|

Totals |

$11,184 |

159 |

|

aDoes not include portions of the prison that were built in 1985. |

||

Other 22 Prisons Also Likely Have Significant Infrastructure Needs

Unlike the 12 oldest state prisons, a similar in‑depth study by an independent consultant has not been conducted on the other 22 state‑owned prisons. However, as shown in Figure 3, the department reported in 2018 that it would cost a total of about $8 billion to address all maintenance and repairs identified at the 22 prisons as being necessary to complete between 2018‑19 and 2023‑24. We note that the actual need could be higher given that the condition of these prisons has not been fully assessed at the same level as the state’s 12 oldest prisons. Moreover, the condition of the 22 prisons could have worsened at a higher rate than estimated in 2018.

Figure 3

$8 Billion in Estimated Repairs Needed at Other 22 Prisonsa

(In Millions)

|

Prison |

Cost |

|

Pleasant Valley State Prison |

$616 |

|

Centinela State Prison |

540 |

|

California State Prison, Solano |

494 |

|

California State Prison, Corcoran |

470 |

|

Pelican Bay State Prison |

455 |

|

Calipatria State Prison |

453 |

|

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility |

436 |

|

Ironwood State Prison |

434 |

|

California State Prison, Los Angeles County |

433 |

|

Chuckawalla Valley State Prison |

430 |

|

California State Prison, Sacramento |

423 |

|

Mule Creek State Prison |

405 |

|

North Kern State Prison |

362 |

|

Wasco State Prison |

332 |

|

Avenal State Prison |

331 |

|

Central California Women’s Facility |

282 |

|

California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility |

278 |

|

Salinas Valley State Prison |

277 |

|

High Desert State Prison |

262 |

|

Valley State Prison |

189 |

|

Kern Valley State Prison |

90 |

|

California Health Care Facility |

— |

|

Total |

$7,992 |

|

aRepairs identified as being necessary to complete between 2018‑19 and 2023‑24. |

|

Size and Housing Needs of Inmate Population

As we discuss below, another significant factor affecting the level of infrastructure needs within the state’s prisons is the inmate population both in terms of its size, which affects the number of prisons needed, and its makeup, which affects the type of prisons and facilities needed.

Number of Inmates

Population Size Directly Related to Need for Prisons Due to Overcrowding Limit. In recent years, the state has been under a federal court order to limit the population of its 34 state‑owned prisons to 137.5 percent of their design capacity. As such, the state is currently allowed to house no more than about 117,000 inmates in the 34 state‑owned facilities. If the prison population exceeds the population cap at any point in time, a court‑appointed officer is authorized to order the release of the number of inmates required to meet the cap. To ensure that such releases do not occur if the prison population increases unexpectedly, CDCR houses about 2,000 fewer inmates than is allowed under the cap as a “buffer” against the cap. (See the box on page 8 for more information on the court‑ordered prison population limit.)

In order to comply with the prison population cap, the state took a number of actions. These include (1) housing inmates in contracted facilities, (2) constructing additional prison capacity, and (3) reducing the inmate population through several policy changes. Because the inmate population still currently exceeds the court‑ordered limit, the state houses inmates in beds outside of the 34 state‑owned prisons, such as contracted prisons. As of February 5, 2020, CDCR housed about 670 male inmates and 180 female inmates in privately operated contract prisons. In addition, the state housed about 1,600 male inmates in publically operated contract prisons.

Methodology Used to Assess State’s 12 Oldest Prisons

A consultant hired by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation recently completed an in‑depth assessment of the state’s 12 oldest prisons. In assessing the condition of these prisons, the consultant compiled information on the condition of individual buildings and building systems (such as electrical systems or plumbing systems) at each prison. Specifically, the consultant (1) reviewed existing facility condition data and documentation (such as blueprints), (2) visited each prison to collect additional data and speak with staff responsible for daily operations and facility maintenance, and (3) estimated the condition of some buildings based on the condition of similar buildings that were constructed at the same time.

The above information was then used to calculate a 10‑Year Facility Condition Index (FCI) for each building and for each prison as a whole. The 10‑Year FCI is the estimated cost of currently needed and expected repairs to a building over the next ten years as a percentage of the cost to replace it entirely with a similar facility that meets updated design standards. The building industry generally uses 65 percent as a threshold for recommending complete replacement. This means that if the cost of needed repairs is 65 percent or more of the cost to replace the building, it is likely more cost‑effective to replace the building than to repair it.

After an FCI for each building and prison as a whole was calculated, the consultant selected particular buildings or building systems for repair or replacement using the following major steps:

- Replace Critical Buildings When More Cost‑Effective Than Repairing. The study generally recommended replacing all buildings critical to prison operations, such as kitchens, that had FCIs of 65 percent or higher. Less critical buildings, such as warehouses, were generally not recommended for replacement.

- Reduce FCI of Overall Prison to 15 Percent or Below by Upgrading Critical Systems in Essential Buildings. After identifying entire buildings for replacement, the study selected specific building systems in other buildings for repair or replacement that would, together, reduce the FCI for the entire prison to 15 percent or below. Priority was given to building systems identified as the most critical to prison operations (such as electrical systems) and located in buildings most essential for providing inmate services (such as inmate housing units).

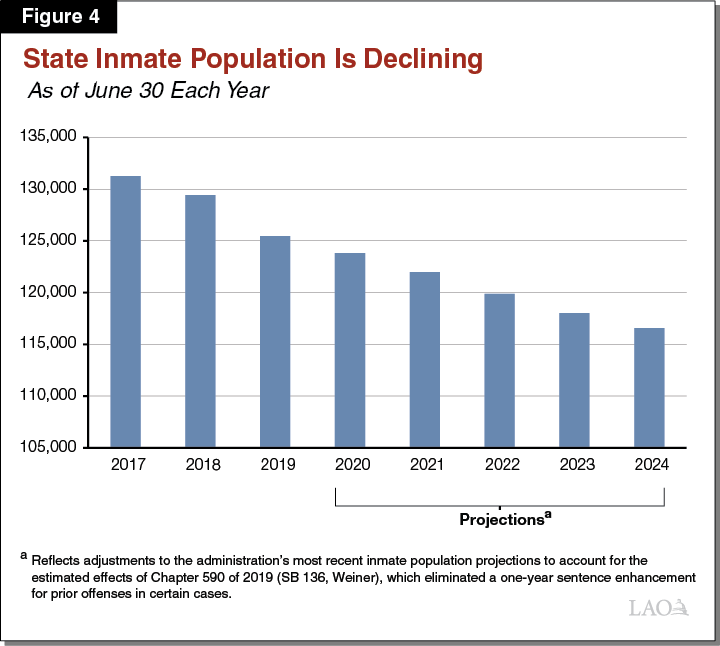

Population Decline Has Not Reduced Need for Prisons… As shown in Figure 4, the state’s inmate population has declined by about 5,800 inmates (4 percent) between June 30, 2017 and June 30, 2019. The decline is primarily due to Proposition 57 (2016), which made certain nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration and expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce prison terms through credits. Despite these declines, the need for all of the state’s existing prisons has not changed. This is because state law requires the department to first accommodate declines in the prison population by removing inmates from privately operated contract prisons housing males. CDCR expects to remove the last 670 inmates remaining in these facilities by April 2020.

Federal Court Orders to Improve Inmate Health Care and Limit Prison Overcrowding

In December 1995, after finding the state failed to provide constitutional mental health care to inmates, a federal court in the case now referred to as Coleman v. Newsom appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR’s) progress towards providing an adequate level of mental health care. In February 2006, after finding the state failed to provide a constitutional level of medical care to inmates, a federal court in the case now referred to as Plata v. Newsom appointed a Receiver to take control over the direct management of the state’s prison medical care delivery system from CDCR.

In November 2006, plaintiffs in Coleman v. Newsom and Plata v. Newsom filed motions for the federal courts to convene a three‑judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act to determine whether (1) prison overcrowding was the primary cause of CDCR’s inability to provide constitutionally adequate inmate health care and (2) a prisoner release order was the only way to remedy these conditions. In August 2009, the three‑judge panel declared that overcrowding was the primary reason that CDCR was unable to provide adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that, in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison system. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms.) The court ruling applies to the number of inmates in prisons operated by CDCR and does not preclude the state from housing additional inmates elsewhere, such as conservation camps and other publicly or privately operated facilities.

…But Continued Decline Could Reduce Number of Prisons Needed in Future. As shown in Figure 4, the inmates population is expected to continue to decline in the next few years. Specifically, we project that, after the 670 male inmates are removed from privately operated prisons, the population will decline by about 6,200 inmates by June 2024. State law requires CDCR to accommodate declines in the inmate population—after privately operated male contract prisons are closed—by reducing either the capacity of state‑operated prisons or the remaining contracted prisons (including publically operated contract prisons and privately operated prisons for females) based on consideration of various criteria, including cost and the housing needs of the inmate population. If the population does decline by 6,200 inmates as projected, the state could close two prisons without violating the court‑ordered limit on prison overcrowding. (As we discuss later in this report, the Governor plans to instead first remove all male inmates from publically operated contract prisons and then potentially close one state prison at some point in the next five years.)

Housing Needs of Inmates

Inmate Security Levels Drive Infrastructure Need. CDCR classifies inmates into four housing security levels, ranging from Level I (lowest security) to Level IV (highest security). Level I and Level II inmates are typically housed in open dormitories, which are large rooms with multiple beds. In contrast, Level III and Level IV inmates are housed in cells, each of which holds no more than two inmates, and are in facilities with armed guard coverage. CDCR’s celled housing facilities vary in the amount of visibility afforded to officers from a centralized location. Facilities built after 1980 tend to have the greatest amount of visibility, are generally considered safer, and can be operated with fewer officers than an older‑style facility with poorer visibility. As a result, CDCR prioritizes these facilities for higher security inmates. As shown in Figure 5, CDCR’s Level IV facilities are more crowded than other housing levels. This indicates that the state currently has greater need for higher security level facilities, which generally tend to cost more to build and operate. (For more detailed information on how CDCR assigns inmates to housing security levels, please see our May 2019 report Improving California’s Prison Inmate Classification System.)

Figure 5

High Security Facilities are Most Crowdeda

|

Housing Level |

Number of Inmates |

Capacity |

Percent of Capacity |

|

I |

13,950 |

12,505 |

112% |

|

II |

46,837 |

35,374 |

132 |

|

III |

20,557 |

18,420 |

112 |

|

IV |

27,314 |

14,936 |

183 |

|

Totals |

108,658 |

81,235 |

134% |

|

aExcludes all female inmates and male inmates who (1) have not yet been assigned to a housing level or (2) are housed in a specialized bed that does not have a designated housing level. |

|||

Other Inmate Housing Needs Also Drive Infrastructure Needs. Various inmate needs beyond security also affect the types and location of facilities where inmates can be housed. For example, inmates with disabilities requiring certain physical design features, such as wheelchair ramps, can only be housed at facilities that include such features. Inmates considered to be at high risk to attempt suicide require cells without elements such as bars or sharp corners that could be used in a suicide attempt. Inmates who are at risk of contracting Valley Fever—an infection caused by fungus in soil that can become airborne and enter the lungs—cannot be housed at nine Central Valley prisons where the fungus is found.

Inmate Services

As we discuss below, the types of services the state provides inmates are also a major source of infrastructure needs within the prisons. For example, federal court requirements to improve inmate health care have driven—and continue to drive—major infrastructure expenditures. In addition, efforts to expand the provision of rehabilitation programs result in infrastructure needs.

Inmate Health Care Services Require Certain Facilities. Prisons include specialized facilities and equipment for staff to provide medical, dental and mental health services to inmates. For example, CDCR uses specialized inmate housing to provide short‑term inpatient care for inmates experiencing mental health crises. Due to federal court orders to improve inmate medical and mental health care services, the state has made significant improvements to the health care facilities in its prisons over the past decade to help ensure that inmates are provided a constitutionally adequate level of care. For example, the state provided about $1.2 billion in General Fund lease revenue bonds in 2012 for CDCR to renovate and construct health care facilities at various prisons. In addition, the state authorized about $900 million in lease revenue bonds to construct the CHCF in Stockton, which was activated in 2013 and provides medical and mental health treatment to inmates who have the most severe and long‑term needs.

While many health care related infrastructure needs have been addressed in recent years, some needs still remain. For example, the health care facilities at the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) in Norco were not renovated because the prison was slated for closure at the time that the above projects were being planned. However, the administration later reversed its decision to close the prison and the Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 includes $5.9 million (General Fund) for health care facility repairs for CRC. In addition, the Governor’s budget includes various other health care related infrastructure proposals, including $91 million in lease‑revenue bond authority to construct a 50‑bed mental health crisis facility at the California Institution for Men in Chino.

Need for Rehabilitation Program Space. In order to provide rehabilitation programs to inmates (such as cognitive behavioral therapy and career technical education), CDCR needs treatment space, classrooms, and workshop spaces. The state has significantly expanded the capacity of rehabilitative programs in recent years. For example, the 2016‑17 budget included a $64 million General Fund augmentation and the 2019‑20 budget included an additional $71.3 million General Fund augmentation for CDCR rehabilitative programing. However, many of the state’s prisons were not built with infrastructure that fully complements CDCR’s current rehabilitative program offerings. This is generally because correctional policies over the 150 year span when the prisons were built reflected either less emphasis on rehabilitation or emphasis on different types of rehabilitation relative to today. For example, while a prison built in the 1940s may include space for education programs, it may not have sufficient classrooms for CDCR to also deliver cognitive behavioral therapy, a treatment modality not developed until the 1960s. CDCR has found ways to work around infrastructure limitations, such as by holding multiple small group therapy sessions at once in large gymnasiums, as is currently being done at San Quentin State Prison (SQ). Such settings, however, are not ideal because the groups lack privacy, which can be important given the personal nature of the topics discussed in some rehabilitation programs. In recent years, the state has taken steps to address this need. For example, the 2019‑20 budget included funding for working drawings to construct additional classroom space at SQ.

State Lacks Plan to Manage Prison Infrastructure

As discussed above, there are various factors that impact the state’s prison infrastructure needs and spending. In particular, the age and condition of the state’s prison facilities and the continued decline in the inmate population will require the state to prioritize future infrastructure spending and reevaluate the number of prisons it operates. However, the state currently lacks a prison infrastructure plan to guide its decisions both in the near term and long term. Such a plan is particularly important given the extent and severity of prison infrastructure needs, as well as the possibility of prison closure in the near term. Without such a plan, it is difficult for the state to prioritize infrastructure spending in such a way as to ensure that the most urgent needs are addressed first and that projects are done in a logical and efficient manner. This is important because, if the state does not address infrastructure issues that present habitability concerns for inmates or significantly threaten prison operations, the risk of infrastructure‑related emergencies and litigation against the state for conditions resulting from its poor infrastructure will grow.

The absence of a prison infrastructure plan also makes it difficult for the Legislature to effectively evaluate the Governor’s various prison infrastructure proposals for 2020‑21. For example, it would not be ideal for the Legislature to approve a modification to a building that would be replaced or closed a few years later due to a decline in the prison population. We also note that having a prison infrastructure plan that prioritizes future projects allows the state to plan for the costs of these projects and their potential impact on prison operations.

Road map for Developing a Prison Infrastructure Plan

In this section, we provide a road map to guide the Legislature in the development of a plan for managing prison infrastructure. First, given the size of the projected decline in the inmate population and the poor condition of many of the state’s prisons, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to develop a plan to close two prisons in the near term. Next, we recommend directing CDCR take specific steps to develop a strategy for upgrading its remaining prison facilities to meet their infrastructure needs and achieve other operational or programmatic goals. Figure 6 provides an overview of our recommended road map for developing a prison infrastructure plan.

Figure 6

LAO Recommended Road Map for Developing State Prison Infrastructure Plan

|

Direct CDCR to Close Two Prisons |

|

|

|

|

Require CDCR to Develop a Strategy to Improve Infrastructure |

|

|

Direct CDCR to Close Two Prisons

As a first step in developing a prison infrastructure plan, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to close two prisons in the near term. We also recommend directing CDCR to begin the process of developing a detailed prison closure plan. We discuss these recommendations in detail in the next section.

Prioritize Prison Closure to Achieve Additional Benefits

After all remaining male inmates are removed from privately operated contract prisons as required by state law, the Governor proposes to accommodate near‑term population declines by first removing the 1,600 male inmates from publically operated contract prisons and then closing one prison. However, we recommend closing two prisons due to the extensive infrastructure problems that have been identified.

While this approach would require the state to maintain male inmates in publicly operated contract prisons in the near term, it would create three specific benefits. (We note that to remove these inmates from contract prisons, as well as close two prisons, the state would need to take steps to further manage the inmate population, as discussed in the nearby box.) Specifically, prioritizing prison closure would:

- Reduce Risk of Infrastructure Emergencies. Closing two prisons would allow the state to avoid the need to make infrastructure improvements at those two prisons and concentrate resources for infrastructure improvements at the remaining prisons. Accordingly, under this approach, the state could more quickly address the most pressing infrastructure problems across the prison system. This, in turn, would reduce the risk of infrastructure emergencies—such as parts of a prison becoming inoperable or uninhabitable—both at the prisons that are closed, and at the remaining prisons.

- Reduce the Inmate Population. The state could further reduce the inmate population, such as by increasing credit earning rates or enacting sentencing changes. For example, elderly inmates are generally considered for release if they have served more than 25 years in prison and reach 60 years old. Reducing the time served or age eligibility requirements could increase releases.

- Place Inmates Outside of Contract and State‑Owned Prisons. The state could house inmates in placements other than contract and state‑owned prisons. For example, the state could increase the conservation camp population by expanding inmate eligibility (such as by allowing inmates with minor felony detainers into camps) or providing greater participation incentives (such as better pay). (For more information about the state’s options to increase the conservation camp population, please see the “Conservation Camps” section of our report The 2020‑21 Budget: Criminal Justice Proposals.)

- Reduce Buffer Against Population Cap. The state could also house more inmates in the 34 prisons by reducing the roughly 2,000 inmate “buffer” against the cap. (As mentioned earlier, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) houses about 2,000 fewer inmates than is allowed as a buffer to avoid violating the court‑ordered limit on prison overcrowding in the event that the inmate population increases unexpectedly.) For example, CDCR could shift 500 inmates from contract beds to state‑owned prisons without exceeding the cap. However, the state may want to take additional actions to mitigate the increased risk of violating the court order. For example, it could consider establishing agreements with county jails to temporarily delay the transfer of newly convicted inmates to prison in the event that the inmate population increases unexpectedly. However, we note that paying counties to house these inmates would somewhat offset the state savings associated with prison closure and/or removal of inmates from contract prisons.

- Reduce Risk of Infrastructure‑Related Litigation. Given that closing two prisons would allow the state to more quickly improve its poor infrastructure, it would also reduce the risk that the state is sued for the conditions resulting from poor infrastructure. This is particularly important given that the state has already faced some infrastructure‑related litigation. Specifically, on June 4, 2019 a court found that a failed roof on a dining facility at the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility in Corcoran—which was allowing water, mold, bird feces, and maggots to fall into inmate dining areas—violated the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Accordingly, the court ordered CDCR to cease using the dining facility within two weeks until the roof could be repaired.

- Achieve State Savings. In addition to avoiding the need to make costly infrastructure improvements at the prisons that are closed, prioritizing prison closure would create operational savings for the state. This is because the department would save about $90,000 annually per inmate by closing state prisons, whereas it saves roughly $35,000 per inmate annually when it removes inmates from contract prisons. We estimate that prioritizing prison closure over removal of inmates from the remaining contract prisons would allow the state to achieve about $100 million in additional annual operational savings relative to closing contract beds.

Population Management Options

The state has various options it could consider to reduce the need for contract prisons. Specifically, the state could take steps to:

Identify Prisons for Closure Based on Key Criteria

Whether the state chooses to close two prisons in the near term, or only one as proposed by the Governor, it will need to identify the prison or prisons it will close. In order to guide the identification of prisons for closure, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to prioritize prisons for closure using the following criteria:

- Per Inmate Cost Avoidance. The state would create greater savings to the extent it prioritizes for closure prisons that would be costly to continue operating indefinitely relative to the design capacity that they add to the entire system. This means that the state should consider closing prisons with high operational costs and/or costly infrastructure needs but relatively low design capacity.

- Operational Needs. Closure of prisons with specialized missions would have significant operational implications. For example, closure of either the CMF or CHCF would jeopardize the state’s ability to provide health care to its inmates that have the most severe and long‑term needs. Accordingly, the state would likely not want to close a prison with a specialized mission unless it can shift that function to another prison or determine that the function is no longer needed.

- Ability to Adequately Provide Services Undermined by Location. Some prisons have difficulty providing adequate health care, rehabilitation, and other inmate services. Often, this is because their remote location makes it challenging to recruit and retain health care employees (such as physicians). Accordingly, prisons that have difficulty providing adequate services due to their remote location should be prioritized for closure over prisons that operate more effectively.

Ranking facilities based on the above criteria—and any other criteria that the Legislature may wish to consider—would allow the state to identify which two prisons to close in the near term. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide this prison ranking before the May Revision as this information would help inform deliberations on the 2020‑21 budget. For example, the administration’s request for $5.9 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 for health care facility repairs at CRC should not be approved if the facility will be closed in the near future. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on all prison infrastructure proposals until it receives this ranking. When the department has provided this list—or the Legislature has created its own list—we recommend not approving infrastructure modification proposals at the two highest ranked prisons unless they are critical, short‑term repairs essential to operating the prison until it is closed.

Require Development of Detailed Prison Closure Plan

After identifying which prisons to close, the state will need a plan to address the logistics of implementing the closure process. As a part of the prison closure process, the state will likely bargain with unions who represent the employees at the prisons slated for closure on how to minimize the effects on the workforce and day‑to‑day operations. For example, the state may develop an agreement with unions specifying the amount of money that employees who are required to relocate to fill CDCR vacancies elsewhere would receive. To the extent that there are not enough vacancies to accommodate employees affected by prison closure, the state may want to create incentives for employees to voluntarily separate from state service in lieu of a layoff. This would encourage more senior employees—who are more costly to the state and would otherwise not be affected by the layoff—to voluntarily leave state service and prevent the need for less senior employees to be laid off.

The state could consider other alternatives as well, such as training employees at risk of layoff to fill vacancies elsewhere in the department or state government. Given the complexities of implementing these details, the layoff process can take six to nine months to complete. In addition, there are various other logistics that will require advanced planning, such as how the inmate population at the prison will be drawn down and transported elsewhere. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to begin developing a closure plan as soon as the prisons slated for closure have been identified. We recommend that the closure plan and associated labor agreements be submitted to the Legislature by January 10, 2021 for consideration as part of the 2021‑22 budget process.

Require CDCR to Develop a Strategy to Improve Infrastructure

After identifying which prisons to close in the near term—and, therefore, which prisons will be operated over the medium and long terms—we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to create a strategy to improve the infrastructure at these prisons. Specifically, we recommend the department (1) identify which projects should be pursued and (2) determine a priority order and time line for accomplishing these projects.

Identify Infrastructure Projects to Pursue

We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to provide, by January 10, 2022, a list of significant, high‑priority infrastructure projects that should be accomplished over the next ten years. Below, we outline various factors that we recommend the Legislature direct the department to consider in developing this list.

Possibility of Further Prison Closures. To the extent the inmate population continues to decline after June 2024, it is possible that the state would be able to close additional prisons in the medium term. The state will want to identify these prisons, based on the criteria discussed earlier in this report, so that it can appropriately gauge the degree of infrastructure upgrades to make at these prisons. For example, if it appears likely that a particular prison may be closed in ten years, it would be reasonable for the state to approve funding to replace an electrical generator with an expected useful life of roughly ten years. However, it could be reasonable for the state to continue to repair leaking pipes at that prison as needed rather than fund a prison‑wide replacement of piping that would have an expected useful life beyond ten years. In contrast, at a prison the state expects to operate indefinitely, it might opt to replace both the electrical generator and piping, as it would be more cost‑effective than repairing the leaking pipes repeatedly for long periods of time.

Currently, it is difficult to assess how many prisons the state will likely need to operate in ten years because CDCR’s projections of the inmate population only extend five years. To help determine whether additional prison closures may be warranted in the future, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to estimate the likely impact of known significant changes in sentencing and credit earning rates over the next ten years both on the overall inmate population and key subpopulations, such as the number of inmates requiring high‑security housing. This information—along with the prison prioritization list discussed above—would help the Legislature determine what level of infrastructure upgrades to make at prisons that may be closed in the medium term. We recommend requiring the department to provide these long‑term inmate population projections by January 10, 2022 and annually thereafter. These projections would allow the state to annually readjust its expectations for the need for infrastructure projects.

Actual Viability of Existing Infrastructure. As discussed above, the study of the state’s 12 oldest prisons often recommended repairing or replacing systems in buildings critical to prison operations if they were nearing or past their expected useful life. However, the study also noted that with diligent maintenance, some systems can be reliably operated past their expected useful life. Accordingly, when identifying which projects are necessary, CDCR, should consider which of the buildings and systems recommended for repair or replacement can continue to function for a longer period of time with appropriate maintenance. This would help the state to focus infrastructure upgrades on the buildings and systems that are most likely to fail in the near future.

Alternatives to Repairing Existing Facilities. As discussed above, the study assessing the state’s 12 oldest prisons made recommendations for repair or replacement of infrastructure based largely on the cost of needed repairs as a percent of the cost of rebuilding. The study did not consider other potential operational cost savings or programmatic benefits that could be achieved by redesigning, relocating, or consolidating facilities rather than simply repairing or rebuilding them similar to their current designs. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to consider:

- Redesigning or Consolidating Facilities to Achieve Lower Operational Costs. As discussed above, design features—such as clear lines of sight on recreation yards and in housing units—can reduce the amount of custody staffing needed to operate the prison. In addition, consolidating prisons could reduce overhead costs of operating them. For example, rather than repairing or rebuilding housing units at one prison, CDCR could close the prison and rebuild the housing capacity as infill on the grounds of other prisons. This could create substantial ongoing operational savings. Accordingly, in determining whether to repair or rebuild facilities, the department should consider whether ongoing operational savings that could be achieved by redesigning or consolidating facilities would justify the higher cost of rebuilding as opposed to repairing them.

- Rebuilding Facilities in Better Location. As discussed above, some prisons have difficulty providing adequate services to inmates due to their remote location. Accordingly, CDCR should consider rebuilding prisons or portions of prisons in areas where it is easier to deliver services to inmates. This consideration would be particularly important if the state is already going to be rebuilding a significant portion of a prison. For example, rather than rebuilding a housing unit at a remote prison, the department should consider whether it could achieve better programmatic outcomes by closing the facility and building a similarly sized housing unit as infill on the grounds of a different, less‑remote prison. In addition to improving staff recruitment, this would likely place more inmates closer to their families and allow the state to take better advantage of volunteers located in urban areas who often assist with operating rehabilitative programs.

- Redesigning Facilities to Better Meet Inmate Needs. In considering what infrastructure projects to pursue, CDCR should not only assess infrastructure needs based on facility age and condition, as was done in the study of the 12 oldest prisons, but also whether existing infrastructure—regardless of condition—is appropriately meeting inmate needs and legislative priorities. This means that the department should assess the need for additional high‑security housing, classrooms, health care space, suicide prevention features, accessibility modifications, or security features (such as video surveillance systems). In addition, if the state does decide to rebuild significant portions of prisons, this would present an opportunity to better align prison design with current correctional policies—such as a greater emphasis on rehabilitation than existed when many of the state’s prisons were built.

Develop Project Priority Order and Time Line

After identifying a list of projects to accomplish over the next ten years, the state will need to determine when the projects will be completed. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to provide a project priority order and time line by January 10, 2023. We further recommend directing the department to develop this project prioritization and time line using the following steps:

- Prioritize Addressing Issues That Threaten Inmate, Staff Well‑Being. CDCR should first prioritize addressing infrastructure needs that threaten inmate and staff well‑being. This would help the state minimize the possibility of infrastructure emergencies that could harm inmates or staff or prevent the department from being able to use significant portions of a prison on short notice. This, in turn, would likely help reduce litigation risk.

- Prioritize Projects that Create Significant Operational Savings. Next, CDCR should prioritize projects that would create significant ongoing operational savings. For example, repairing a guard tower would eliminate the need for staffing additional correctional officers to provide perimeter security.

- Time Projects to Prevent Unnecessary Costs. In determining a project order, CDCR should avoid making modifications to a facility that is then rebuilt or renovated only a few years later. For example, CDCR is currently pursuing a project to install air cooling systems in several inmate housing units at the California Institution for Men in Chino, one of the 12 oldest prisons. However, the study recommended replacing those housing units entirely. While it is unclear if CDCR will actually replace those housing units, if it did so, it would need to reinstall a new air cooling systems in the replacement housing units—effectively paying for two air cooling projects. Given that there will not be time for the state to finalize its infrastructure improvement strategy to inform the 2020‑21 budget process, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to explain in budget hearings how each of the proposed infrastructure modification projects would interact with potential future infrastructure projects.

- Assess Whether Grouping Projects by Location Would Reduce Costs. Construction projects in areas where inmates are present often cost more than similar projects completed elsewhere. This is because security protocols—such as counting construction tools—lengthen project time lines, creating additional costs. Accordingly, CDCR could potentially reduce construction costs by temporarily removing inmates from a portion of a prison in order to complete all of the projects in that area. On the other hand, reducing the inmate population at a prison could also reduce the amount of inmate labor available to assist with construction work through the department’s Inmate Ward Labor (IWL) program, which could in turn, increase costs. (The IWL program hires inmates to work on infrastructure projects at its prisons. These inmates earn between $0.35 and $1.00 per hour and learn various skills, such as roofing or building foundation pads, depending on the nature of the project.)

Conclusion

Given the magnitude of the state’s prison infrastructure needs, combined with the possibility of closing prisons in the near future, it is important for the state to have a near‑term and long‑term plan to manage its prison infrastructure. In order to guide the Legislature in the development of such a plan, we outline in this report a road map for closing two prisons and prioritizing infrastructure projects at the remaining prisons. Following our recommended road map would allow the state to more effectively and efficiently address the continued decline in the inmate population and the significant repairs needed at many of its prisons.