LAO Contacts

- Helen Kerstein

- Victim Grant Programs

- Luke Koushmaro

- Youth and Community Restoration

- Probation

- Inmate Health and Rehabilitation

- Anita Lee

- Judicial Branch

- Department of Justice

- Indigent Defense

- Caitlin O'Neil

- Prisons

February 18, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Criminal Justice Proposals

- Criminal Justice Budget Overview

- Cross‑Cutting Issues

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Department of Youth and Community Restoration

- Judicial Branch

- Department of Justice

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overview. The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget includes a total of $19.7 billion from all fund sources for the operation of judicial and criminal justice programs. This is a net increase of $341 million (2 percent) over the revised 2019‑20 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $16.2 billion in 2020‑21, which represents an increase of $213 million (1 percent) above the revised 2019‑20 level. In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the judicial and criminal justice area and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize some of our major recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of the report.

Probation Funding and Reforms. The Governor proposes $71 million (General Fund) and budget trailer legislation to (1) modify the existing funding formula for incentivizing counties to reduce the rate at which they send felons on community supervision to state prison (referred to as the SB 678 funding formula), (2) require increased supervision of certain misdemeanor probationers and provide limited‑term funding for this supervision, and (3) reduce the length of felony and misdemeanor probation.

We recommend the Legislature reject the proposed changes to the SB 678 formula as they could have unintended consequences, such as reducing counties’ incentive to send fewer individuals to prison. However, in order to more effectively keep misdemeanor probationers out of prison, we recommend expanding the SB 678 formula to include misdemeanor probationers as an alternative to the proposed increase in misdemeanor probation supervision. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature reject the proposal to reduce the length of probation as it could result in a larger portion of individuals being sentenced to jail or prison.

Correctional Staff Training and Job Shadowing. The Governor’s budget includes a total of $21.4 million (General Fund) to implement various initiatives to improve correctional staff training, such as a facility for hands‑on officer training and a new job shadowing program. While the various training initiatives generally appear worthwhile, we recommend that the Legislature reject 42 of the requested 85 positions and associated $6.7 million because they have not been fully justified. We also recommend the Legislature require the administration to provide an annual report on training outcomes that could be impacted by the initiatives. This would allow the Legislature more effectively provide oversight of officer standards and training.

Telehealth Services Building. The Governor’s budget proposes $2 million (General Fund) for preliminary plans to construct a telehealth services building at San Quentin State Prison to better recruit Bay Area physicians and psychiatrists to provide telehealth services. The estimated total cost of the project is $26 million. We recommend that the Legislature reject the proposal and instead direct the administration to provide a plan next year to utilize telecommuting. We find that utilizing telecommuting would have several benefits over the proposed capital outlay project including being much less costly and allowing for wider recruitment.

Online Adjudication of Infractions. The Governor’s budget proposes $11.5 million (General Fund)—increasing to $56 million annually beginning in 2023‑24—to expand statewide the use of an online adjudication tool. We find that the impacts of the online adjudication tool are still uncertain and could require more funding than currently proposed. It is also premature to expand the tool statewide prior to the completion of the statutorily required evaluation of the tool. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal.

Bureau of Forensic Services (BFS) Support. The Governor’s budget proposes to provide a total of $49.7 million in one‑time and ongoing General Fund to (1) backfill declines in criminal fine and fee revenue supporting BFS; (2) fund the site acquisition and planning phase for a new consolidated forensic science laboratory campus; and (3) fund equipment replacement, facility maintenance, and workload related to recent legislation. We recommend the Legislature approve these proposals. In addition, we also recommend requiring local agencies to partially support BFS beginning in 2021‑22 and directing the Department of Justice to develop a plan to implement this change given the substantial benefit BFS provides local agencies. This would provide an ongoing solution to the continued decline in BFS fine and fee revenue.

Criminal Justice Budget Overview

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating offenders back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and the California Department of Justice (DOJ). The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 proposes total expenditures of $19.7 billion for the operation of judicial and criminal justice programs. Below, we describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice and provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2020‑21.

State Operational Expenditure Trends

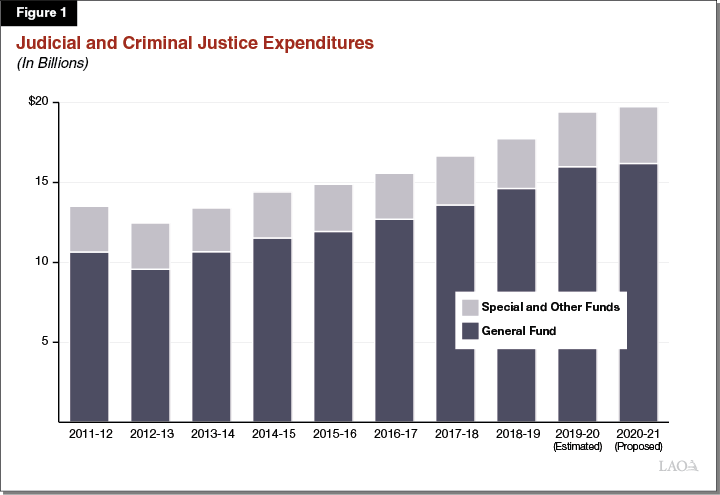

Spending Was Relatively Low Early in the Decade… As shown in Figure 1, total state expenditures on the operation of criminal justice programs were relatively low in the early part of the decade. This was primarily due to two factors. First, in 2011 the state realigned various criminal justice responsibilities to the counties, including the responsibility for certain low‑level felony offenders. This realignment reduced state correctional spending and was the primary reason for the decrease in expenditures between 2011‑12 and 2012‑13. Second, the judicial branch—particularly the trial courts—received significant one‑time and ongoing General Fund reductions. A major motivation behind both the 2011 realignment and the reductions made to trial courts was the fact that the state faced annual budget shortfalls exceeding several billion dollars between 2008‑09 and 2012‑13 due to the Great Recession.

…But Has Increased Steadily Since Then. However, overall spending for the operational support of criminal justice programs has increased steadily since 2012‑13. This was largely due to additional funding for CDCR and the trial courts. For example, increased CDCR expenditures resulted from (1) the cost of complying with court orders related to prison overcrowding and improving inmate health care, (2) increased employee compensation costs, and (3) spending on costs deferred during the fiscal crisis. (For more information on this issue, please see our recent brief State Correctional Spending Increased Despite Significant Population Reductions.) During this same time period, various augmentations were provided to the trial courts to offset reductions made in prior years and to fund specific activities.

Governor’s Budget Proposals

Total Proposed Spending of $19.7 Billion in 2020‑21. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s 2020‑21 budget includes a total of $19.7 billion from all fund sources for the operation of judicial and criminal justice programs (excluding planned capital outlay expenditures). This is a net increase of $341 million (2 percent) over the revised 2019‑20 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $16.2 billion in 2020‑21, which represents an increase of $213 million (1 percent) above the revised 2019‑20 level. We note that this increase does not include increases in 2020‑21 employee compensation costs for these departments, which are budgeted elsewhere. If these costs were included, the increase would be somewhat higher.

Figure 2

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Actual |

Percent |

||||

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

$12,597 |

$13,320 |

$13,395 |

$75 |

0.6% |

|

General Funda |

12,278 |

13,014 |

13,088 |

75 |

0.6 |

|

Special and other funds |

319 |

306 |

306 |

— |

— |

|

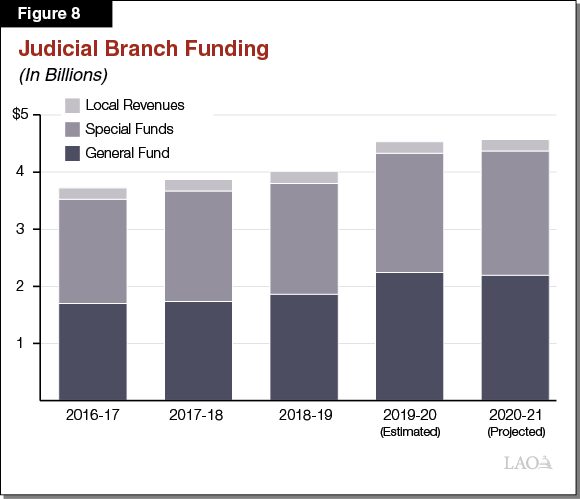

Judicial Branchb |

$3,801 |

$4,330 |

$4,367 |

$37 |

0.9% |

|

General Fund |

1,860 |

2,240 |

2,192 |

‑48 |

‑2.1 |

|

Special and other funds |

1,941 |

2,090 |

2,176 |

85 |

4.1 |

|

Department of Justicec |

$902 |

$1,086 |

$1,107 |

$22 |

2.0% |

|

General Fund |

291 |

360 |

370 |

10 |

2.8 |

|

Special and other funds |

611 |

725 |

737 |

12 |

1.6 |

|

Board of State and Community Corrections |

$185 |

$381 |

$298 |

‑$83 |

‑21.7% |

|

General Fund |

93 |

255 |

127 |

‑128 |

‑50.2 |

|

Special and other funds |

92 |

126 |

171 |

46 |

36.4 |

|

Department of Youth and Community Restorationd |

— |

— |

$290 |

$290 |

— |

|

General Fund |

— |

— |

284 |

284 |

— |

|

Special and other funds |

— |

— |

5 |

5 |

— |

|

Other Departmentse |

$265 |

$290 |

$291 |

$1 |

0.2% |

|

General Fund |

95 |

112 |

132 |

20 |

17.8 |

|

Special and other funds |

169 |

178 |

159 |

‑19 |

‑10.9 |

|

Totals, All Departments |

$17,750 |

$19,407 |

$19,748 |

$341 |

1.8% |

|

General Fund |

14,618 |

15,981 |

16,194 |

213 |

1.3 |

|

Special and other funds |

3,131 |

3,426 |

3,555 |

129 |

3.8 |

|

aDoes not include revenues to General Fund to offset corrections spending from the federal State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. bIncludes funds received from local property tax revenue. cDoes not include funding related to the National Mortgage Settlement. dWas previously the Division of Juvenile Justice within the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. eIncludes Office of the Inspector General, Commission on Judicial Performance, California Victim Compensation Board, Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, State Public Defender, funds provided for trial court security, and debt service on general obligation bonds. Note: Detail may not total due to rounding. |

|||||

Major Spending Proposals. The most significant piece of new spending included in the Governor’s budget relates to a $108 million General Fund augmentation for the trial courts. In addition, the budget includes $71 million from the General Fund to support proposed changes in the way county probation departments supervise misdemeanor probationers ($60 million) and modifications to an existing grant program supporting county probation departments ($11 million). The budget also provides $35 million General Fund for various proposals to expand rehabilitation programs within CDCR, including $27 million to provide technology for inmates participating in academic programs. We note that the proposed spending increases are partially offset by decreases in funding, primarily due to the expiration of one‑time grant funding previously provided to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC).

Cross‑Cutting Issues

Combining the State’s Programs for Victims of Crime

We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to report at budget committee hearings on their time line for consolidating programs that serve victims of crime. If the administration is unable to provide a time line acceptable to the Legislature, we recommend that the Legislature consider directing the administration to complete the consolidation within a designated time frame. The specific time line for the consolidation could be developed in consultation with the Office of Emergency Services (OES) and the California Victim Compensation Board (CalVCB). We further recommend that the time line for consolidation be specified in budget trailer legislation to ensure that the Legislature’s direction to the administration continues to be clear.

Background

Numerous Recommendations to Consolidate Victim Programs. The state maintains numerous programs that serve victims of crime, such as grants to organizations that support victims of child abuse, human trafficking, domestic violence, or other types of trauma. These programs are generally administered by OES and CalVCB. Since 2002, several entities—including the California Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency; the Little Hoover Commission; the State Auditor; and our office—have identified weaknesses in the state’s administration of programs serving victims of crime and have argued for greater coordination and consolidation of these programs. For example, in our March 2015 report, The 2015‑16 Budget: Improving State Programs for Crime Victims, we found that (1) current victim programs administered by OES and CalVCB lack coordination, (2) the state is likely missing opportunities for federal grants, (3) many programs are small and appear duplicative, and (4) narrowly targeted grant programs undermine prioritization. To address these weaknesses, we recommended that all victim programs be consolidated under a restructured CalVCB that focuses solely on victim programs. We also recommended that the Legislature require the new board to develop a comprehensive strategy for addressing the key weaknesses in the state’s victim programs.

Legislature Required Administration to Create a Plan for Consolidation. Following our 2015 report, the Legislature enacted Supplemental Reporting Language (SRL) as part of the 2015‑16 budget package requiring that the administration—working with CalVCB and OES—submit a plan by January 10, 2016 to consolidate the state’s victim programs under the same administering entity. In response to the SRL, CalVCB and OES provided a report that summarized CalVCB and OES’s respective roles related to victim services and provided some examples of CalVCB and OES’s ongoing efforts to collaborate. However, the report failed to provide the required consolidation plan. Accordingly, as part of the 2018‑19 Budget Act, the Legislature adopted provisional language requiring CalVCB and OES to provide a report to the Legislature by January 10, 2019 with options and recommendations for consolidating the state’s victim programs under one entity. In response to this requirement, CalVCB and OES prepared a more comprehensive report. This report contained a number of recommendations, including (1) a phased approach to consolidating victim programs, starting with implementing various steps to improve coordination between CalVCB and OES, and (2) a detailed consolidation plan in December 2019.

Governor Expressed Intention to Consolidate Victim Programs. In the administration’s summary 2019‑20 budget, the Governor indicated his plans to submit a proposal in 2020‑21 to consolidate the state’s victim programs within a single department. He further indicated that this proposal was aimed at addressing the problem of the state administering dozens of victim programs through multiple state departments in a manner that is not designed to maximize ease of access for victims.

Governor’s Proposal

Despite the Governor’s intention to pursue a consolidation as part of his proposed 2020‑21 budget, the Governor’s budget does not include a specific proposal. Rather, the administration states that while it still intends to pursue this consolidation, the plan has been temporarily paused. The administration indicates that this pause is driven by (1) the complexity of the consolidation of the state’s victim programs and (2) OES’s limited capacity to implement the consolidation given its role in coordinating response and recovery efforts related to recent disasters. Based on our discussions with the administration, we understand that there is currently no set time line for proceeding with the consolidation effort.

Assessment

Consolidation of Victims Programs Continues to Make Programmatic Sense. We continue to find that consolidating all victim programs under a single department would improve services for victims of crime by enhancing coordination and maximizing the use of federal funds. Furthermore, we continue to find that this department should be focused entirely on victims. This point is reinforced by the fact that, according to the administration, OES was unable to pursue consolidation efforts because of its need to focus on disaster response.

Rationale for Delay Is Not Compelling and Lack of Revised Time Line Is Problematic. We do not find the administration’s rationale for pausing its effort to consolidate victim programs indefinitely to be compelling. While there are complexities associated with such a reorganization, the Governor is proposing several others as part of the 2020‑21 budget. Notably, one of these reorganizations involves bringing another entity—the Seismic Safety Commission—under OES. If OES can expand its capacity to take on the Seismic Safety Commission, it seems reasonable that it should have sufficient capacity to continue the effort to consolidate victim programs. Accordingly, at a minimum, we think it is reasonable for the Legislature to expect a revised time line for completing this consolidation.

Recommendation

Require OES and CalVCB to Report at Budget Hearings on Time Line for Consolidation. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration—including CalVCB and OES—to report at budget committee hearings on their time line for consolidating programs that serve victims of crime in a timely manner. This information is important for the Legislature to have given its demonstrated interest in consolidation.

If the administration is unable to provide a time line for consolidation that is acceptable to the Legislature, we recommend that the Legislature consider directing the administration to complete the consolidation within a designated time frame. The specific time line for the consolidation could be developed in consultation with OES and CalVCB to ensure that it is realistic given the complexities involved. We further recommend that the time frame for consolidation be specified in budget trailer legislation to ensure that the Legislature’s direction to the administration continues to be clear.

Probation Funding and Reforms

The Governor proposes $71 million General Fund in 2020‑21 and budget trailer legislation to (1) modify the SB 678 funding formula, (2) require increased supervision of certain misdemeanor probationers and provide limited‑term funding for this supervision, and (3) reduce the length of time individuals are on felony and misdemeanor probation. We find that the changes to the SB 678 formula could have various unintended consequences and thus recommend the Legislature reject these changes. In addition, we find that requiring supervision of certain misdemeanor probationers would likely not prevent misdemeanor probationers from going to prison. As an alternative, we recommend the Legislature expand the SB 678 funding formula to include misdemeanor probationers, which would more likely reduce the number of misdemeanor probationers sent to prison. Finally, we find that reducing the length of time individuals spend on probation could increase jail and prison sentences and thus recommend the Legislature reject the proposal.

Background

Overview of Sentencing. Criminal cases can be resolved through plea bargains—agreements for the defendant to plead guilty, typically in exchange for the prosecutor reducing charges or recommending a specific sentence—or through trials. Trials can be decided by a judge or by a jury. In the event that a plea deal is accepted or a guilty verdict is issued, a judge will then hold a hearing to deliver a sentence. Judges have discretion to sentence individuals as authorized by statute and can choose to accept, modify, or deny plea deals.

Sentencing law generally defines three types of crimes: felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions. A felony is the most serious type of crime. Existing law classifies some felonies as “violent” or “serious,” or both. Examples of violent felonies include murder and robbery. While almost all violent felonies are also considered serious, some felonies are only defined as serious, such as assault with intent to commit robbery. A misdemeanor is a less serious offense. Misdemeanors include crimes such as assault, petty theft, and public drunkenness. An infraction is the least serious offense and is generally punishable by a fine.

Felony Sentencing. Offenders convicted of felonies can be sentenced as follows:

- County Jail or Split Sentence. Felony offenders who have no prior or current convictions for serious, violent, or sex offenses are generally sentenced to county jail. Courts may sentence such offenders to spend their entire sentence in county jail. Alternatively, courts may require such offenders to serve a “split sentence” with a portion of their sentence being in jail and a portion being in the community under “mandatory supervision” provided by a county probation officer. Offenders who violate the terms of their community supervision are typically returned to county jail. However, if they commit a new prison‑eligible crime, they can be sentenced to prison.

- State Prison and Parole or Post‑Release Community Supervision (PRCS). Felony offenders who are ineligible for county jail because of their criminal history are sentenced to state prison. Upon release from prison, offenders with a current serious or violent offense are supervised in the community by state parole agents. The remainder of offenders are generally placed on PRCS and supervised by county probation officers. Offenders who violate the terms of their supervision are typically placed in county jail. However, if they commit a new felony, they can be sent to prison.

- Felony Probation. Instead of sentencing felony offenders to prison, county jail, or a split sentence, a court may place an offender on felony probation, depending on the offender’s criminal history. Individuals placed on felony probation are typically assigned to a county probation officer who supervises them in the community. Probation can last up to five years or the maximum sentence for the offender’s crime, whichever is greater. Courts can change the terms of an individual’s probation at any time and can choose to discharge an individual from probation early for reasons such as good conduct and progress towards rehabilitation. Offenders who violate the terms of their probation can be subject to the felony sentence that they would have otherwise received, such as being sentenced to state prison.

Misdemeanor Sentencing. An individual convicted of a misdemeanor can be sent to jail or placed on misdemeanor probation. Unless an offender is convicted of multiple misdemeanors, jail sentences for misdemeanors cannot exceed one year but many have lower maximum sentences such as six months. Misdemeanor probation can last for up to three years. Offenders who violate the terms of their supervision can be subject to the misdemeanor sentence that they would have otherwise received, such as being sentenced to jail. However, many individuals on misdemeanor probation are not actively supervised by probation officers. Misdemeanor offenders who commit new prison‑eligible felonies can be sent to prison.

California Performance Incentives Act (SB 678). Chapter 608 of 2009 (SB 678, Leno) was enacted to incentivize counties to reduce the rate at which they sent felony probationers to state prison—known as the felony probation failure rate. Under SB 678, counties received a portion of the state correctional savings that resulted from reductions in the felony probation failure rate. Chapter 26 of 2015 (SB 85, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) updated the formula to award counties for reductions in the rate at which the other felony supervision populations—offenders on PRCS and mandatory supervision—are sent to prison. Accordingly, this gave counties the incentive to reduce the overall felony supervision failure rate, rather than just the felony probation failure rate. Chapter 26 also adjusted the SB 678 funding formula to reduce the volatility of the funding awarded to counties. Under Chapter 26, counties receive funding based on the following three components:

- Funding for Reducing Felony Supervision Failure Rate Below Prior Year. The first funding component compares a county’s most recent annual felony supervision failure rate with the rate from the previous year. If the failure rate is lower than the previous year, the county receives 35 percent of the estimated state correctional savings associated with that reduction. This is intended to incentivize counties to continue to reduce the felony supervision failure rate each year.

- Funding for Reducing Felony Supervision Failure Rate Below Baseline. The second funding component compares a county’s felony supervision failure rate to a statewide baseline felony supervision failure rate of 7.9 percent. Depending on how the county’s rate compares to the baseline, the county will receive between 40 percent and 100 percent of the highest payment they received between 2011‑12 and 2014‑15. This is intended to (1) incentivize counties to reach a rate that is below the baseline and (2) ensure that a county that is already below the baseline will continue to receive funding even if it is not able to further reduce its rate.

- Funding to Guarantee $200,000 Minimum Award. The third component guarantees that each county receives at least $200,000. If the first two components total less than this amount, the county’s award is increased to $200,000. This is intended to ensure counties continue to receive at least some state funding.

Counties can only use SB 678 funding to provide supervision and rehabilitation services for offenders on felony supervision. Examples of how this funding could be used include electronic monitoring and evidence‑based rehabilitation programs, such as cognitive behavioral treatment. In addition, counties are required to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs and practices and can use the funding to pay for these evaluations.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 includes various proposals totaling $71 million General Fund (declining to $11 million annually by 2024‑25) and budget trailer legislation that would (1) modify the SB 678 funding formula, (2) require increased supervision of certain misdemeanor probationers and provide limited‑term funding to support this supervision, and (3) reduce the length of time individuals would be on felony and misdemeanor probation. We describe these changes in greater detail below.

Modification to SB 678 Funding Formula ($11 Million). The Governor proposes budget trailer legislation to modify the SB 678 funding formula in an effort to further reduce the volatility in the funding that the program provides to counties. Under the Governor’s proposal, counties would no longer receive funding based on their felony supervision failure rate. Instead, counties would receive a set amount each year equal to the highest award they received between 2017‑18 and 2019‑20. To fund this change, the administration is proposing $11 million from the General Fund on an ongoing basis.

However, the amount a county receives could be reduced in the future if the county increases the number of felons on community supervision they send to prison in multiple years. Specifically, counties would receive warnings if there is an increase in the total number of individuals on felony supervision who are sent to prison in a given year that exceeds the county’s baseline amount by ten individuals or 24 percent (whichever is greater). The baseline for each county would be equal to the average number of individuals on felony supervision who were sent to prison between 2016 and 2018. A county’s funding in a given year would be reduced to 50 percent of its prior year award if the county had received two or more warnings in the three preceding years. However, as is currently the case, counties would be guaranteed at least $200,000 in funding.

The administration is also proposing to broaden the allowable uses of SB 678 funds to include services and supervision for misdemeanor probationers. As we discuss below, this is intended to help counties offset the costs associated with the Governor’s proposal to require increased supervision of certain misdemeanor probationers.

Increased Misdemeanor Probation Supervision and Funding ($60 Million). The Governor proposes requiring probation departments to more actively supervise individuals on misdemeanor probation for certain offenses. Specifically, departments would be required to actively supervise misdemeanor probationers whose offenses are related to the unlawful possession of firearms, theft, domestic violence, and certain sex offenses.

In addition, the Governor’s budget includes increased General Fund support over a four‑year period—$60 million annually in 2020‑21 through 2022‑23, and $30 million in 2023‑24—for county probation departments to increase the level of supervision provided to individuals on misdemeanor probation for the above offenses. The funding is intended to support the required increase in supervision for four years. After the four‑year period, counties would continue to be required to provide increased supervision to the specified misdemeanor probationers but would need to use their own funds to do so, as state funding would no longer be provided specifically for this purpose. Due to the Governor’s proposed change in the allowable uses of SB 678 funds mentioned above, counties could choose to use that funding to pay for these costs.

According to the administration, the above changes are in response to an increase in the number of individuals with prior terms of misdemeanor probation being admitted to prison. The administration indicates that requiring the supervision of misdemeanor probationers and providing limited‑term funding to support the supervision would reduce the likelihood that such individuals end up in prison.

Reduce Length of Felony and Misdemeanor Probation Supervision. The Governor proposes to reduce the maximum amount of time individuals could spend on felony and misdemeanor probation to the lesser of (1) two years or (2) the maximum term of incarceration for their crime. In practice, this would mean that misdemeanor probation would be capped at one year—the maximum term of incarceration for misdemeanors—unless the offender had been convicted of multiple misdemeanors.

The Governor also proposes establishing a process to allow individuals on felony probation or on misdemeanor probation for one of the misdemeanors requiring supervision to be discharged early. Under the proposal, county probation departments would be required to discharge such individuals from probation if they have substantially complied with the terms of their probation for one year.

According to the administration, the above changes should result in counties providing increased supervision and services earlier in the probation term, when research indicates individuals are more likely to recidivate. The administration indicates that this should lead to improved outcomes for misdemeanor probationers and reduce the number of such probationers sent to prison.

Assessment

Proposal to Address SB 678 Volatility Is Unnecessary and Could Create Unintended Consequences. As discussed earlier, the Governor proposes to reduce the volatility in the SB 678 funding that is provided to counties. However, we find that the fluctuations in SB 678 funding are generally relatively small compared to the total budgets for county probation departments. On average, the difference between the minimum and maximum award counties received over the last three years was less than $400,000, or about 1 percent of the average probation department budget in 2017‑18 (the most recent data available).

Moreover, we find that that administration’s proposal to change the SB 678 funding formula is problematic and can result in unintended consequences. Specifically, we find the following:

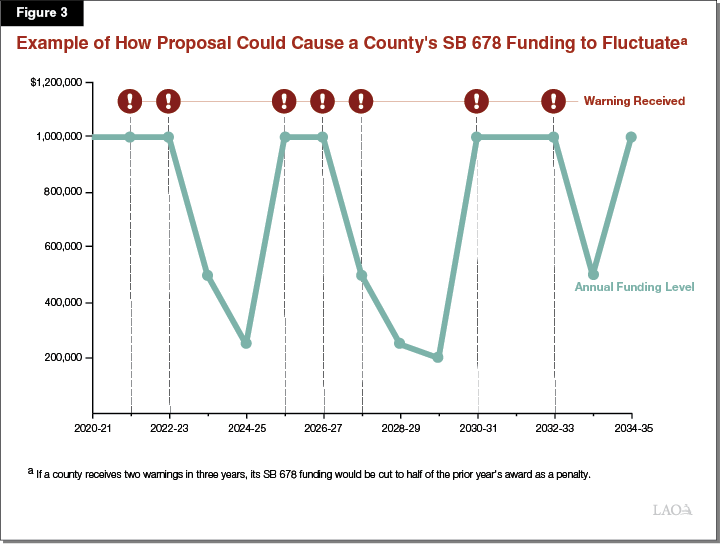

- Proposal Could Actually Increase Volatility and Harm Future Performance. Under the Governor’s proposal, counties would be penalized and receive less funding if they increase the total number of individuals on felony supervision who are sent to prison over multiple years and receive two or more warnings. Such counties could actually experience more volatility once penalized. This could make it difficult for a county to recover once its funding has been cut. For example, if a county receives two warnings in the three most recent years, it would only receive 50 percent of its prior‑year award. If the county then received another penalty in the following year, its funding would be reduced by another 50 percent. As a result, if a county received multiple penalties in a row, its funding could eventually be reduced to the minimum of $200,000. This means the proposed changes could actually increase rather than reduce volatility in SB 678 funding. Moreover, the proposed penalties could reduce the availability of resources for counties to pursue evidence‑based practices. As a result, not only would funding levels be highly volatile, the funding structure could undermine future performance if reduced resources lead to counties providing fewer services. Figure 3 provides an example of how a county that starts out with a $1 million award could be impacted by the proposed funding formula in this way.

- Proposal Undermines Incentive to Reduce Prison Population. The current formula for SB 678 incentivizes counties to continue to reduce the prison population by reducing the felony supervision failure rate. In contrast, under the proposed approach, counties would only be incentivized to keep the number of individuals sent to prison low enough to avoid a warning. Removing the incentive for further reductions would undermine the legislative intent of SB 678.

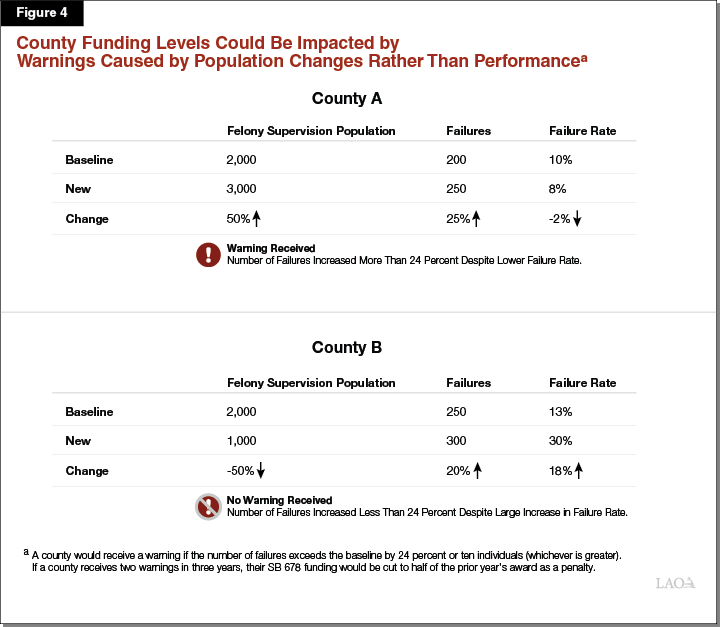

- Number of Supervised Individuals Could Distort Penalties and Rewards. The proposed formula would be based on the number of individuals on felony supervision who are sent to prison rather than on changes to the felony supervision failure rate. This means that counties that have an increase in the number of individuals on felony supervision could potentially be penalized for maintaining or even improving their felony supervision rate. It could also mean that counties whose felony supervision populations decline could have an increase in the felony supervision failure rate without being penalized. Figure 4 provides two hypothetical scenarios of a county (County A) getting a warning despite improved performance while another county (County B) does not get a warning despite more than doubling its felony supervision failure rate. Given the administration’s proposal to reduce the length of supervision, it is likely that felony supervision populations could decline significantly, making scenarios similar to the one illustrated for County B more likely.

Proposed Increase in Misdemeanor Probation Supervision Problematic… The administration states that requiring counties to supervise certain misdemeanor probationers and providing limited‑term funding for misdemeanor supervision and services would reduce the number of misdemeanor probationers who eventually end up in prison. However, the following aspects of the proposal make it unlikely that this would occur.

- Funding Provided Irrespective of Success. Unlike the current SB 678 funding formula for individuals on felony supervision, the proposed resources for misdemeanor probation would not be based on the extent to which counties reduce the number of individuals who are sent to prison. Instead, counties would receive these funds irrespective of whether they reduce prison commitments.

- Lack of Incentive for Counties to Actually Increase Service Levels. While the administration intends to increase services for individuals on misdemeanor probation, it is not clear that counties would actually increase such services. This is because the proposal only requires the supervision of certain individuals on misdemeanor probation but does not require counties to provide additional services. We note that counties currently have the authority to provide services to misdemeanor probationers. If counties thought this was an effective use of their funding, they would likely already be providing these services.

- Could Prevent Counties From Using Resources in More Effective Ways. Research suggests that the most effective way to reduce recidivism is to concentrate resources on individuals with a high risk to reoffend and a high need for services. However, the proposal’s supervision requirement would be based on the individual’s offense rather than the individual’s risk of reoffending or need for services. As a result, the proposal could result in resources being unnecessarily spent on misdemeanor probationers that are low risk and/or low need instead of allowing those resources to be used in ways that could be more effective at reducing recidivism.

…and More Effective Alternative Exists. We find that expanding the current SB 678 funding formula to award counties for reducing the rate at which misdemeanor probationers are sent to prison is a better approach to reducing the number of such individuals in prison relative to the Governor’s proposal. First, unlike the administration’s approach, it would give counties an ongoing fiscal incentive to reduce the number of misdemeanor probationers sent to prison. Second, it would also give counties the flexibility to focus supervision and services on the misdemeanor probationers they have identified as having the highest risks and needs rather than requiring counties to focus on individuals on probation supervision for specific offenses. This could ultimately help reduce the state’s prison population and create state savings, that would be partially shared with the counties responsible for creating it.

Reducing Probation Terms and Mandating Early Discharge Could Have Unintended Consequences. While reducing probation terms might result in counties choosing to provide additional supervision and services earlier in the probation term, it would likely have unintended consequences.

- Limit on Probation Terms Could Increase Sentences to Jail and Prison. Courts already have the discretion to both set an individual’s probation at two years or less. If courts determine that someone should be on probation for more than two years, the court likely feels that the individual would not be ready to be in the community unsupervised before that time. It is unlikely that the Governor’s proposed limits would change this sentiment. Instead, because the two‑year limit would only apply to probation, it might lead courts to consider other sentencing options that would result in offenders being monitored for a longer period of time. For example, the courts could place an individual in prison which would then be followed by parole or PRCS. We would note that because such alternatives to probation involve incarceration, it would also result in more individuals being placed in jail or prison.

- Requiring Early Discharge Could Increase Sentences to Jail and Prison Similarly, mandating that probation departments provide probationers early discharge if they generally comply with the terms of their supervision could further disincentive courts from placing an individual on probation. Courts already have the discretion—and a process established in statute—to terminate an individual’s probation early for reasons such as good conduct and progress towards rehabilitation. As a result, the proposed early discharge process would only make a meaningful difference in cases where it results in an individual being released earlier than the courts would otherwise authorize. Courts might consider this when determining how to sentence such an individual and, in order to prevent this from occurring, might send the individual to prison or jail.

- Changes Could Result in More Plea Bargains Requiring Incarceration. While many cases would likely continue to be settled with plea bargains, we note that reducing the length of probation and judicial discretion in decisions to terminate probation early might also be a concern for prosecutors. For example, under the current process prosecutors can weigh in on decisions to terminate probation early but the proposed early discharge process does not include such a role for prosecutors. As a result, prosecutors might be more reluctant to propose or accept plea bargains involving probation for reasons similar to those above. This could result in a larger portion of plea bargains involving prison or jail.

Recommendations

Reject Proposal to Stabilize SB 678 Funding. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed statutory changes to SB 678 and $11 million augmentation to support these changes. We find that the Governor’s proposal is unnecessary as the current volatility in SB 678 funding appears to be relatively low. In addition, we find that the proposed changes to the formula could have a number of unintended consequences, such as increasing the volatility of the funding counties receive and reducing their incentive to keep felony probationers out of prison.

Reject Misdemeanor Probation Proposal and Instead Expand SB 678. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to require counties to supervise individuals on probation for certain misdemeanor offenses, given that it appears unlikely that the proposal would effectively prevent misdemeanor probationers from going to prison. Instead, we recommend the Legislature expand the current SB 678 funding formula to reward counties for keeping misdemeanor probationers out of prison. We find that this would be more likely to reduce the number of misdemeanor probationers who are sent to prison. We note that if the Legislature chose to expand SB 678 to include misdemeanor probationers, it could consider providing counties with some initial funding to assist in the expansion of evidence‑based practices and services for this population. For example, the Legislature could redirect the $60 million for misdemeanor supervision proposed by the Governor in 2020‑21, or a different amount, for this purpose on a limited‑term basis. This would allow counties to create evidence‑based services for misdemeanor probationers that would help prevent them from being sent to prison. As a result, counties would receive a portion of the resulting state savings to maintain and expand such services.

Reject Proposal to Reduce Probation Terms. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to reduce probation terms by limiting them to two years and instituting mandatory early discharge. We are seriously concerned that these changes could have unintended consequences, such as increasing the number of individuals who are sentenced to jail or prison rather than probation.

Indigent Defense Grant Program

We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide specific details regarding the proposed pilot program for indigent defense services (such as the primary goals of the program and the types of activities that would be funded) by April 15, 2020. Pending receipt of this information, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal.

Background

Counties Generally Responsible for Providing Attorney Representation in Criminal Cases. Both the federal and state Constitution guarantee certain rights to defendants in criminal cases, including the right to the assistance of an attorney in their defense. The state has generally delegated responsibility for providing such assistance to the counties. As such, counties are typically responsible for funding defense attorneys for indigent defendants (generally defined as individuals who cannot afford their own attorneys) in criminal cases. Counties provide defense attorneys to indigent defendants in three ways: (1) establishing a county‑operated public defender’s office, (2) contracting with private law firms or practitioners, and (3) paying for attorneys appointed by the court. In 2017‑18, counties reported spending roughly $1 billion on public defense attorney representation.

Concerns With Effective Defense Representation. In recent years, concerns have been raised about the effectiveness of the representation counties provide to indigent defendants. For example, the ACLU and certain private law firms sued the State of California and Fresno County alleging that the state and Fresno County are failing to provide meaningful and effective legal defense representation to indigent defendants in criminal cases. The litigation raised various concerns, including the lack of appropriate levels of funding for defense representation, the lack of parity in funding between prosecutors and defense attorneys, excessive defense attorney caseloads, and the lack of necessary training to ensure meaningful representation of clients. Similar concerns have been raised in other states as well.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $10 million General Fund (one time) for the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) to administer a pilot program, in consultation with the Office of the State Public Defender, to provide grants to eligible county public defender offices for indigent defense services. Of this amount, up to $200,000 would be available for BSCC to contract for an evaluation of the pilot grant program. Finally, grant recipients would be required to report on the use of this funding to BSCC. The administration indicates that additional details about the proposed pilot program will be forthcoming.

Ensure Proposed Grant Program Is Consistent With Legislative Priorities

While it is possible that the proposed pilot grant program could be worthwhile, the Legislature currently does not have sufficient information from the administration to effectively evaluate its merits. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to ensure that the administration provides additional information that clearly outlines what specific goals the program is intended to achieve and what specific activities the funds would support. For example, it is currently not clear whether the program is intended to reduce caseloads, improve the quality or consistency of defenses raised by attorneys, or achieve some other goal. Knowing the goals of the program and how the funds would be used would help the Legislature determine whether the program is structured in a manner consistent with its priorities.

Additionally, given that the program is a pilot, the Legislature will want to ensure the administration provides clear information on how funded programs and activities would be evaluated and the specific information that would be collected to do so. Such information is important as it would help ensure that data is collected consistently to enable comparisons between counties and between funded programs and activities aimed at addressing the same identified goal. More importantly, it would help ensure that the Legislature has sufficient information to determine the effectiveness of the pilot program and whether it should be continued on a larger scale in the future, particularly in the larger context of indigent defense representation.

Recommendation

Withhold Action Pending Additional Information. In light of the above concerns, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide details on the grant program by April 15, 2020. Specifically, such details should include: (1) the primary goals of the proposed grant program, (2) the specific types of programs and activities that would be eligible for funding for each goal, and (3) how funded programs and activities would be evaluated. This information would help the Legislature effectively evaluate whether the program is structured in a manner consistent with its priorities. Until the above information is provided, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal. To the extent that the administration is unable to provide the specified details, we would recommend the Legislature reject this proposal.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Overview

CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of January 15, 2020, CDCR housed about 123,700 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 35 prisons and 42 conservation camps. About 2,800 inmates are housed in contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 52,100 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who violate the terms of their parole. In addition, 769 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), which includes three facilities and one conservation camp. However, beginning July 1, 2020, DJJ will be removed from CDCR and become a separate department—the Department of Youth and Community Restoration.

Operational Spending Proposed for 2020‑21. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $13.4 billion ($13.1 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2020‑21. Figure 5 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the prior and current years and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $75 million, or less than 1 percent, from the estimated 2019‑20 spending level. This increase reflects various augmentations, including increased workers compensation costs and funding proposed by the Governor for adult probation departments as a part of a proposal to change probation supervision terms and practices discussed earlier in this report. This additional proposed spending is partially offset by various spending reductions, most notably a reduction reflecting the shift of DJJ and reduced spending for contract beds. (The proposed $75 million increase does not include anticipated increases in employee compensation costs in 2020‑21 because they are accounted for elsewhere in the budget. These increases are currently budgeted to exceed $100 million.)

Figure 5

Total Expenditures for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Adult institutions |

$11,102 |

$11,676 |

$11,956 |

$280 |

2% |

|

Adult parole |

689 |

750 |

765 |

15 |

2 |

|

Administration |

556 |

589 |

614 |

25 |

4 |

|

Division of Juvenile Justicea |

200 |

245 |

— |

‑245 |

‑100 |

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

51 |

60 |

60 |

‑1 |

‑1 |

|

Totals |

$12,597 |

$13,320 |

$13,395 |

$75 |

0.6% |

|

aBeginning in 2020‑21, the Division of Juvenile Justice within CDCR will become a separate department—the Department of Youth and Community Restoration—under the Health and Human Services Agency. |

|||||

Capital Outlay Spending Proposed for 2020‑21. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $497 million ($111 million General Fund) for CDCR capital outlay projects in 2020‑21. This amount includes (1) $92 million in additional General Fund support to continue previously approved projects and to begin four new projects at existing CDCR facilities, (2) $91 million in new lease revenue bond authority to construct a mental health crisis bed facility at the California Institution for Men in Chino, and (3) $224 million in previously authorized General Fund lease revenue bonds for various counties to construct or renovate correctional facilities.

Trends in the Adult Inmate and Parolee Populations

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request pending receipt of updated population projections at the May Revision.

Background

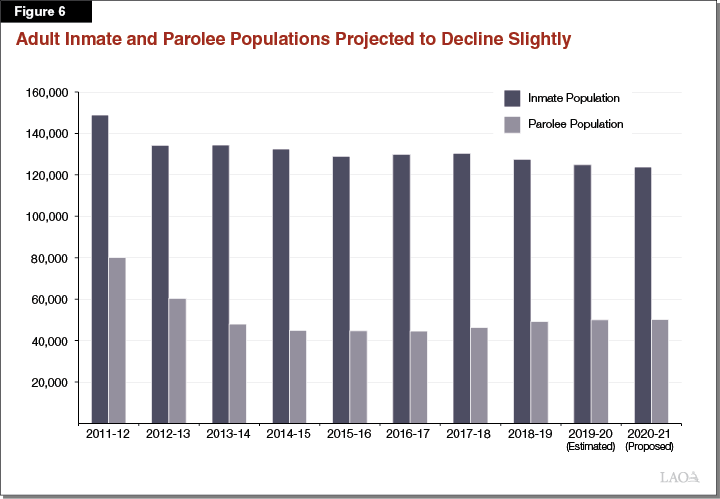

As shown in Figure 6, the average daily inmate population is projected to be 123,700 inmates in 2020‑21, a decrease of about 900 inmates (1 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The average daily parolee population is projected to be 50,500 in 2020‑21—roughly the same as the estimated current‑year level. The projected decrease in the inmate population is primarily due to the estimated impact of Proposition 57 (2016), which made certain nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration and expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ prison terms through credits.

Governor’s Proposal

Net Reduction in Population Funding for Current and Budget Years. The Governor’s January budget plan for 2020‑21 proposes a net decrease of $54.6 million in the current year and a net decrease of $29.5 million in the budget year related to projected changes in the overall population of adult offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole). The current‑year net decrease in costs is primarily due to a larger than anticipated reduction in the use of contract beds and the number of offenders housed in state‑operated prisons relative to what was assumed in the 2019‑20 Budget Act. This decrease in cost is partially offset by projected costs, primarily due to increases in parole‑related costs relative to what was assumed in the 2019‑20 Budget Act. The budget‑year net reduction in expenditures is primarily due to a projected decrease in the inmate population as a result of Proposition 57, which is partially offset by various increased costs, such as parole‑related costs.

Budget Adjustments Will Be Updated in May. As a part of the May Revise, the administration will update these budget requests based on updated population projections. In addition, the administration indicates that it plans to adjust the projections and associated budget requests to account for the estimated effects of two policy changes: (1) Chapter 590 of 2019 (SB 136, Wiener), which eliminates a one‑year sentence enhancement for prior offenses in certain cases and (2) a planned regulatory change that will advance certain inmates’ release consideration dates when they earn credits for certain significant educational achievements.

Recommendation

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision.

Conservation Camps

Between May 2019 and December 2019, the number of inmates in conservation camps has declined and has averaged only about 2,900 inmates, despite having the capacity for about 4,600 inmates. Given the reduction in state costs that could likely be achieved by increasing the conservation camp population, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report in spring budget hearings on (1) what options it is considering (if any) to do so and (2) the feasibility of removing restrictions on camp eligibility for certain low‑risk inmates.

Background

CDCR Operates Conservation Camps. CDCR operates 42 conservation camps located throughout the state. Inmates assigned to conservation camps carry out fire suppression work and respond to other emergencies, such as floods and earthquakes. In addition, fire crews work on conservation projects on public lands and provide labor on local community service projects.

Only Certain Inmates May Be Placed in Camps. Inmates generally qualify for placement in camps if CDCR has determined they (1) can be safely housed in a low‑security environment, (2) can work outside a secure perimeter under relatively low supervision, and (3) are medically fit for conservation camp work. CDCR generally makes this determination based on various factors including the nature of the crimes inmates are convicted of, their behavior while in prison, and the amount of time they have left to serve on their sentence. For example, CDCR excludes from camps inmates (1) convicted of specific crimes, including sex offenses; (2) who have more than five years left to serve; and (3) who are wanted by outside law enforcement agencies on other charges.

CDCR Offers Various Incentives for Inmates to Seek Placement in Camps. Inmates can generally earn time off of their prison term faster if housed in a camp than if housed elsewhere. For example, inmates serving terms for violent offenses can earn one day off of their sentences for every day served with good behavior in a camp, while they can only earn one day off for every four days served elsewhere. In addition, inmates are paid between $1.45 per day and $3.90 per day depending on their position and an additional $1 per hour when they are engaged in firefighting work. This is significantly higher than most other inmate jobs, which generally pay between $0.08 and $1.00 per hour. Other aspects of camps—such as the food quality and the lower‑security environment—also tend to be viewed favorably by inmates compared to standard prison settings.

Recent Decline in Conservation Camp Population. In recent years, CDCR has typically housed roughly 3,500 inmates in camps, which have a capacity of about 4,600 inmates. However, between May 2019 and December 2019, the camp population declined and has averaged only about 2,900 inmates. The administration indicates that Proposition 57 has caused a decline in the overall inmate population, including the number of inmates eligible to be housed in camps. This is because the measure expanded opportunities for inmates to be released earlier than otherwise—such as by allowing CDCR to authorize additional sentencing credits. This means that inmates in camps are completing their sentences faster than CDCR can recruit eligible inmates to replace them. For example, the administration reports that prior to the effects of Proposition 57, inmates spent roughly three to four years in camps on average while they now spend only roughly nine months on average.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget assumes that CDCR’s 42 conservation camps will house an average daily population of 2,900 inmates in 2020‑21.

Assessment

Increased Utilization of Camp Beds Could Reduce State Costs. Under the Governor’s proposal, 37 percent of camp beds would be vacant. To the extent the state could fill a greater portion of these beds, it could likely reduce costs in multiple ways.

- Decreased Use of Contract Prison Beds. The state currently can only house a limited number of inmates in state‑owned and operated prisons due to a federal court‑ordered population cap. As such, the state houses some inmates outside of such prisons, including in contract prisons and conservation camps. To the extent the state can increase the number of inmates in conservation camps, it can reduce the number of inmates housed in contract prison beds, which cost about $18,000 more annually per bed than a camp bed.

- Reduced Inmate Population. As mentioned above, inmates housed in camps can generally earn time off of their prison sentence faster than if housed elsewhere. Accordingly, placing additional inmates in camps would generally allow those inmates to be released earlier. In turn, this would reduce the state prison population and state costs.

- Potentially Reduced Wildfire Mitigation Costs. When insufficient inmate crews are available, the state must use other crews—such as those formed by employees of federal agencies or private companies—which can increase costs. Accordingly, increasing the camp population, which would increase the number of inmates available to support state wildfire fighting efforts, could reduce the need to rely on more costly crews.

If the state could increase the camp population by about 600 inmates—returning it to its roughly 3,500 inmate level prior to the effects of Proposition 57—we estimate that the total reduction in state costs could be in the low tens of millions of dollars annually.

State Has Various Alternatives to Increase Camp Population. The state could provide greater incentives for inmates to participate in camps, such as by giving them increased pay. Alternatively, the state could expand inmate eligibility for camps. In a recent report, we identified cases where CDCR’s existing eligibility criteria seem to be unnecessarily excluding certain populations of inmates from camps, as well as presented options for removing these restrictions in ways that increase the camp population without jeopardizing public safety. Specifically, we recommended CDCR create processes for allowing low‑risk sex offenders, inmates with more than five years left to serve, and inmates wanted by another law enforcement agency on minor charges into camps. (For more information, see our report Improving California’s Prison Inmate Classification System.)

Recommendation

In view of the above, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to report in spring budget hearings on what options it is considering (if any) to increase the camp population and a time line for implementing such options. We further recommend the Legislature have CDCR report on the feasibility of removing restrictions on camp eligibility for certain inmates, such as inmates with more than five years left to serve. The above information would allow the Legislature to consider whether it wants to direct the department to take any of these steps in order to increase the camp population.

Correctional Staff Training and Job Shadowing

The Governor’s budget includes a total of $21.4 million (General Fund) in 2020‑21 to implement various initiatives to improve correctional staff training, such as a facility for hands‑on officer training and job shadowing program. While the various training initiatives proposed by the Governor generally appear worthwhile, we recommend that the Legislature reject 42 of the requested 85 positions and associated funding because they have not been fully justified. Accordingly, we recommend reducing the Governor’s proposal by $6.7 million. We also recommend requiring the administration to provide an annual report on training outcomes that could be impacted by the initiatives.

Background

CDCR Correctional Training. CDCR operates a 13 week correctional officer academy at the Richard A. McGee Correctional Training Center in Galt. At the academy, cadets learn the basic practices of a correctional officer—such as how to search inmate property—in a largely classroom‑based setting. Afterward, graduates are assigned to prisons and begin work as correctional officers.

The Commission on Correctional Peace Officer Standards and Training (CPOST) is statutorily responsible for developing, approving, and monitoring standards for the selection and training of correctional officers and supervisory staff, as well as monitoring CDCR’s design and delivery of staff training. CPOST is comprised of six members, three appointed by CDCR to represent the department’s management and three appointed by the Governor to represent the members of the California Correctional Peace Officers’ Association (the union representing CDCR correctional staff). The 2019‑20 budget includes $1.3 million from the General Fund for CPOST and $83 million from the General Fund for CDCR to deliver training to peace officers.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget includes a total of $21.4 million (General Fund) and 54 positions in 2020‑21 to (1) renovate and staff a facility to be used for hands‑on officer training, (2) implement a job shadowing program for new correctional officers, (3) provide additional staff for CPOST, and (4) increase training for correctional counselors. (Under the proposal, the funding would generally decrease and the positions would increase until reaching $19.8 million and 85 positions in 2023‑24 and annually thereafter.)

New Facility for Hands‑On Training ($8.2 Million). Under the Governor’s proposal, CDCR would convert a former prison located in Stockton into a facility to provide hands‑on training to cadets on topics such as transportation of inmates, contraband surveillance, and escape prevention. The department also plans to offer a new training called “Day in the Life.” At the time of this analysis, however, CDCR was not able to provide information on the specific topics that this training would cover. The training would be integrated into the 13 week academy, allowing cadets to receive a combination of classroom and hands‑on training. The department indicates that this is necessary to ensure that correctional officers do not start their jobs lacking key experiences that are currently not available at the academy. According to CDCR, providing this type of training will improve inmate and staff safety and morale as well as reduce unnecessary use of force and related litigation. The Governor’s budget includes $8.2 million and 17 positions in 2020‑21 for the new training facility. Under the proposal, the level of resources would fluctuate until reaching $7.6 million and 48 positions in 2023‑24 and annually thereafter. These 48 positions would include 28 instructional sergeants, 16 maintenance staff, and 1 sergeant to provide perimeter security.

Job Shadowing Program for New Correctional Officers ($11.5 Million). The department proposes to require new correctional officers to shadow experienced officers for three weeks before the new officers are placed in their permanent assignments. The Governor’s budget provides a total of $11.5 million in ongoing resources for the program. This amount includes (1) $5.2 million to pay the new officers’ salaries during these three weeks and (2) $6.3 million to support 35 correctional sergeant positions (one per prison). These sergeants would coordinate the new job shadowing program and perform various other duties related to staff training that the department indicates have grown in recent years beyond a level that can be accommodated by existing staff.

Additional CPOST Staff ($524,000). The Governor’s budget provides $524,000 in 2020‑21 (decreasing to $462,000 annually beginning in 2021‑22) for CPOST to add two new supervisor‑level positions. CPOST indicates that without these positions, it cannot effectively provide oversight of standards and training for CDCR’s management and supervisory positions. According to CPOST, the additional staff would allow it to better monitor and evaluate outcomes associated with increased staff training, such as use of workers compensation, employee attrition, and morale.

Additional Training for Correctional Counselors ($1.2 Million). Correctional counselors compile and maintain information about inmates—such as their criminal and medical histories—and assist with assigning inmates to appropriate housing settings and rehabilitation programs. The Governor’s budget proposes $1.2 million in 2020‑21 (decreasing to $312,000 annually in 2021‑22) for CDCR to provide training to correctional counselors related to communication and case management skills. The department reports that this is necessary as current training for these staff is focused on knowledge of department policies and regulations but lacks sufficient training on interpersonal communication, which is an important element of their work.

Assessment

Portions of Requested Funding Are Not Fully Justified. We find that efforts to integrate hands‑on training into the academy, implement a job shadowing program for new officers, provide additional staff for CPOST, and expand training for correctional counselors appear reasonable and worthwhile. However, the following portions of the requested funding have not been fully justified:

- Instructors for Day in the Life Training. One of the 19 trainings that CDCR plans to offer at the new facility—called Day in The Life—would drive one‑quarter of the workload for the 28 new instructional sergeants requested for the facility. However, at the time of publication, the department had not explained what this course would entail and why it believes its benefits justify seven dedicated sergeant positions at a total cost of $1.3 million annually.

- Maintenance Staff at New Training Facility. The proposal includes 16 maintenance positions for the new facility—one‑third of the total staffing package proposed for the facility. This includes a locksmith, heavy equipment mechanic, three stationary engineers (responsible for maintaining electrical and mechanical systems), three maintenance mechanics (responsible for repairing plumbing, electrical systems, and various pieces of equipment such as locks), one plumber, and one electrician. While some maintenance staff would be necessary, at the time of this report, the department had not explained why it needs 16 maintenance staff at a facility that is not a 24‑hour institution and does not house inmates. For example, given that no inmates are housed in the new facility’s cells, it is unclear why the department could not bring a locksmith from one of its other institutions to fix locks when needed. Furthermore, the new facility would not need the extensive infrastructure and equipment associated with an operational prison—including industrial kitchens and busses. Accordingly, it is not clear that there would be enough infrastructure and equipment on site to justify all of the requested maintenance staff. We think that one chief engineer, one lead custodian, and two groundskeepers would be a more reasonable maintenance staffing package for the proposed training center.

- Outside Patrol Sergeant at New Training Facility. The proposal includes a sergeant position to perform various security functions, including processing staff and visitors into and out of the facility, monitoring vehicles, and observing video surveillance monitors. It is unclear why a facility with no inmates present would need this level of security.

- Portion of New Prison‑Based Sergeants. The department requests 35 sergeant positions to perform various duties related to staff training. The department provided information showing that there is sufficient new workload related to managing the proposed job shadowing program to justify 13 of the 35 proposed staff. According to CDCR, the remaining 22 proposed positions would accommodate workload that existing staff are unable to complete in a timely manner due to other workload priorities. For example, CDCR indicates that employee orientations are often not provided until after new employees have been working for several months. However, the department has not been able to provide adequate information to justify the additional 22 positions. This information includes: (1) data identifying the specific workload being delayed and the extent to which it is delayed, (2) the impacts of the delayed workload, (3) detailed analysis demonstrating that the 22 requested positions are needed to complete this workload in a timely manner, and (4) alternatives that the department considered for accommodating the identified workload.

Unclear How Legislature Would Be Informed of Training Outcomes. With the requested new supervisory staff, CPOST reports that it would be better able to monitor metrics that it expects to be impacted by these training initiatives. This added data collection capacity would be beneficial, but we note that the proposal did not include any requirement that the Legislature be kept regularly informed of the findings.

Recommendations

Reject Unjustified Portions of New Training Center and Job Shadowing Program. In light of the concerns raised above, we recommend the Legislature reject the following portions of the resources requested for the new training center and job shadowing program that have not been justified:

- Instructors for Day in the Life Training. We recommend that the Legislature reject the seven sergeant positions and associated $1.3 million in funding for the Day in the Life training given that CDCR has not explained what this course would entail or why its benefits would justify its cost.

- Portion of Maintenance Staff. We recommend that the Legislature reject 12 of the proposed 16 maintenance positions as they do not appear necessary. This would reduce the funding needed for the training center by $1.2 million once the training center is fully operational.

- Perimeter Security Sergeant. We recommend that the Legislature reject the perimeter security sergeant position and associated $180,000 in ongoing funding as it is unclear why the new training center would need this level of security.

- Portion of Prison‑Based Sergeants. We recommend that the Legislature reject the 22 prison‑based sergeants and associated $4 million in ongoing funding given that CDCR has not provided an analysis demonstrating the need for these positions.

Approve CPOST Funding but Require Report on Outcomes of Training. We recommend that the Legislature approve the requested resources for CPOST as the additional positions would better position CPOST to meet its Legislative mandates. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature pass budget trailer legislation requiring an annual report from CPOST beginning July 1, 2021 on the correctional training provided by CDCR. This report should include data on relevant outcomes that could be impacted by the improvements to CDCR training—including the number of workers’ compensation claims, use of sick leave, transfer and attrition rates, employee morale, the number of inmate appeals, use of force incidents, and lawsuits brought against the department. The report should also include the conclusions CPOST draws from the data and its plans to address any concerns or challenges identified. This information would help the Legislature more effectively provide oversight of officer standards and training.

Approve Funding to Increase Training for Correctional Counselors. We recommend that the Legislature approve the proposal to increase correctional counselor training given that the objective and funding amount associated with the proposed training appear reasonable.

Applying Credits to Advance Youth Offender Parole Hearings

We recommend that the Legislature reduce the proposed amount by $258,000 in 2021‑22 and $516,000 in 2022‑23 to account for a more reasonable estimate of ongoing workload.

Background

Youth Offender Parole Process. State law generally allows inmates who were under the age of 26 when they committed their offense to be considered by the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) for release earlier than otherwise. For example, an inmate who received a 30 year sentence for a crime the inmate committed at age 25 is considered for release after 15 years—as long as the inmate does not have certain disqualifying case factors, such as being sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. The earliest date that such inmates are eligible for release under this process is known as their youth parole eligible date (YPED).

Sentencing Credits and YPEDs. CDCR generally allows inmates to reduce their prison terms by earning credits for participating in rehabilitation programs and maintaining good behavior. For example, inmates can earn Educational Merit Credits (EMC), which give them between 90 and 180 days off their prison term when they (1) earn high school, associate, bachelor, or post‑graduate degrees or (2) become a certified alcohol and drug counselor.

Currently, credits earned by inmates eligible for the youth offender parole process do not advance their YPEDs. For example, an inmate with a 30 year sentence and a YPED of 15 years who earned a total of one year in credits would still not be considered for release by BPH until after serving 15 years. However, if not released by BPH, the inmate would be released after 29 years due to the impact of the credits.

Chapter 577 of 2019 (AB 965, Stone), however, authorizes CDCR to implement regulations allowing inmates to advance their YPEDs for credits they earn. CDCR indicates it will use this authority to allow inmates to advance their YPEDs by earning EMCs beginning on January 1, 2022. This change will apply retroactively to EMCs earned since August 1, 2017 when EMCs were first introduced.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget requests one, two‑year, limited‑term position and $504,000 from the General Fund in 2020‑21 for CDCR to develop processes and make information technology upgrades needed to apply EMCs to YPEDs in its data systems. Under the proposal, the proposed funding would increase to $847,000 in 2021‑22 and $796,000 in 2022‑23 and each year thereafter primarily for case records staff to (1) review all roughly 20,000 inmates eligible for the youth offender parole process for retroactive application of EMCs and (2) process YPED changes on an ongoing basis when they earn EMCs.

Proposal Likely Overestimates Ongoing Costs