LAO Contact

February 22, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Analysis of Child Welfare

Proposals and Implementation Updates

- Introduction

- Program Background

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Implementation Updates

- Comments and Questions

Summary

Governor’s Budget Proposal for Child Welfare Reflects Net Decrease. The 2023‑24 Governor’s Budget includes around $920 million General Fund ($9.3 billion total funds) for child welfare programs under the Department of Social Services (DSS). This represents a net decrease of around $420 million General Fund ($270 million total funds) from the 2022‑23 revised budget. The net decrease largely reflects the expiration of one‑time and limited‑term augmentations—most of which include multi‑year spending authority—that had been provided for child welfare programs by recent budgets. Under the 2023‑24 proposal, implementation would continue for these recently‑funded programs, as well as for major ongoing child welfare programs, such as Continuum of Care Reform and Family First Prevention Services Act.

Includes One Major New Spending Proposal. While overall child welfare funding is proposed to decrease, the Governor’s Budget includes one significant new spending proposal. As part of the broader California Behavioral Health Community‑Based Continuum federal waiver demonstration project, the administration proposes $10.6 million General Fund in 2023‑24 for increased child welfare workload costs under DSS beginning January 1, 2024. Prior to implementation, the federal government would need to approve the waiver request.

DSS Has Taken Steps to Begin Implementation of Many New Child Welfare Programs Funded by Recent Budget Acts. DSS has received more than $1 billion General Fund to augment child welfare programs in recent years, comprising mostly one‑time funds for new limited‑term programs. For example, some of these major new programs include: building capacity and placement flexibilities for youth with complex care needs, increasing support for family finding and engagement, and developing prevention services. In most cases, DSS has provided guidance and allocations for these new programs within 6 to 12 months, although reaching full program implementation often takes additional time.

Recommend Continuing Oversight and Seeking More Information Around Implementation of New Programs. To improve oversight of the many new child welfare programs, the Legislature could ask the department to provide more detailed anticipated timelines before implementation begins. In addition, the Legislature could direct the department to report on: why developing guidance and launching new programs requires the amount of time it does, what challenges have arisen and required additional time to address, what any unanticipated obstacles have been, and what programs are achieving in terms of impacts on youth and families. Ultimately, the Legislature could use this information to help determine whether the department has sufficient resources to undertake this many new programs simultaneously, as well as whether the new programs are meeting legislative expectations.

Introduction

California’s children and family programs include an array of services to protect children from abuse and neglect and to keep families safely together when possible. This analysis: (1) provides program background; (2) outlines the Governor’s proposed 2023‑24 budget for children and family programs, including child welfare services (CWS) and foster care programs; (3) provides implementation updates on a number of programs that were funded in the current and prior years; and (4) raises questions and issues for the Legislature to consider.

Program Background

Child Welfare Programs and Services. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a variety of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such as substance use disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal to help families remain together, if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care system, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to return to their parents, the state provides assistance to establish a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship. California’s counties carry out children and family program activities for the state, with funding from the federal and state governments, along with local funds.

Federal Funding. When a family is affected by the child welfare or foster care system, and that family meets federal eligibility standards based on income and other factors, states may claim federal funds for part of the cost of providing care and services for the child and family. State and local governments provide funding for the portion of costs not covered by federal funds, based on cost‑sharing proportions determined by the federal government. These federal funds are provided pursuant to Title IV‑E (related to foster care) and Title IV‑B (related to child welfare) of the Social Security Act.

2011 Realignment. Until 2011‑12, the state General Fund and counties shared significant portions of the nonfederal costs of administering CWS. In 2011, the state enacted legislation known as 2011 realignment, which dedicated a portion of the state’s sales and use tax and vehicle license fee revenues to counties to administer child welfare and foster care programs (along with some public safety, behavioral health, and adult protective services programs). As a result of Proposition 30 (2012), under 2011 realignment, counties either are not responsible or only partially responsible for CWS programmatic cost increases resulting from federal, state, and judicial policy changes. Proposition 30 establishes that counties only need to implement new state policies that increase overall program costs to the extent that the state provides the funding for those policies. Counties are responsible, however, for all other increases in CWS costs—for example, those associated with rising caseloads. Conversely, if overall CWS costs fall, counties retain those savings.

Continuum of Care Reform (CCR). Beginning in 2012, the Legislature passed a series of legislation implementing CCR. This legislative package makes fundamental changes to the way the state cares for youth in the foster care system. Namely, CCR aims to: (1) end long‑term congregate care placements; (2) increase reliance on home‑based family placements; (3) improve access to supportive services regardless of the kind of foster care placement a child is in; and (4) utilize universal child and family assessments to improve placement, service, and payment rate decisions. Under 2011 realignment, the state pays for the net costs of CCR, which include up‑front implementation costs. While not a primary goal, the Legislature enacted CCR with the expectation that reforms eventually would lead to overall savings to the foster care system, resulting in CCR ultimately becoming cost neutral to the state. (We note that CCR is a multiyear effort—with implementation of the various components of the reform package beginning at different times over several years—and the state continues to work toward full implementation in the current year.)

Extended Foster Care (EFC). At around the same time as 2011 realignment, the state also implemented the California Fostering Connections to Success Act (Chapter 559 of 2010 [AB 12, Beall]), which extended foster care services and supports to youth from age 18 up to age 21, beginning in 2012. To be eligible, a youth must have a foster care order in effect on their 18th birthday, must opt in to receive EFC benefits, and must meet certain criteria (such as pursuing higher education or work training) while in EFC. Youth participating in EFC are known as non‑minor dependents (NMDs). In addition to case management services, NMDs receive support for independent or transitional housing.

Foster Placement Types. As described above, when children cannot remain safely in their homes, they may be removed and placed into foster care. Counties rely on various placement types for foster youth. Pursuant to CCR, a Child and Family Team (CFT) provides input to help determine the most appropriate placement for each youth, based on the youth’s socio‑emotional and behavioral health needs and other criteria. Placement types include:

- Placements With Resource Families. For most foster youth, the preferred placement type is in a home with a resource family. A resource family may be a relative (either a noncustodial parent, other relative, or nonrelative extended family member), a foster family approved by the county, or a foster family approved by a private foster family agency (FFA). FFA‑approved foster families receive additional supports through the FFA and therefore may care for youth with higher‑level physical, mental, or behavioral health needs.

- Congregate Care Placements. Foster youth with intensive behavioral health needs preventing them from being placed safely or stably with a resource family may be placed in a Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program (STRTP). These facilities provide specialty behavioral health services and 24‑hour supervision. STRTP placements are designed to be short term, with the goal of providing the needed care and services to transition youth safely to resource families. Pursuant to new federal requirements—specifically the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), described more below—STRTPs must meet new federal criteria to continue receiving Title IV‑E funding for federally eligible youth. In addition, STRTP placements must be approved by a “Qualified Individual” (QI) such as a mental health professional.

- Independent and Transitional Placements for Older Youth. Older, relatively more self‑sufficient youth and NMDs may be placed in supervised independent living placements (SILPs) or transitional housing placements. SILPs are independent settings, such as apartments or shared residences, where NMDs may live independently and continue to receive monthly foster care payments. Transitional housing placements provide foster youth ages 16 to 21 supervised housing as well as supportive services, such as counseling and employment services, that are designed to help foster youth achieve independence.

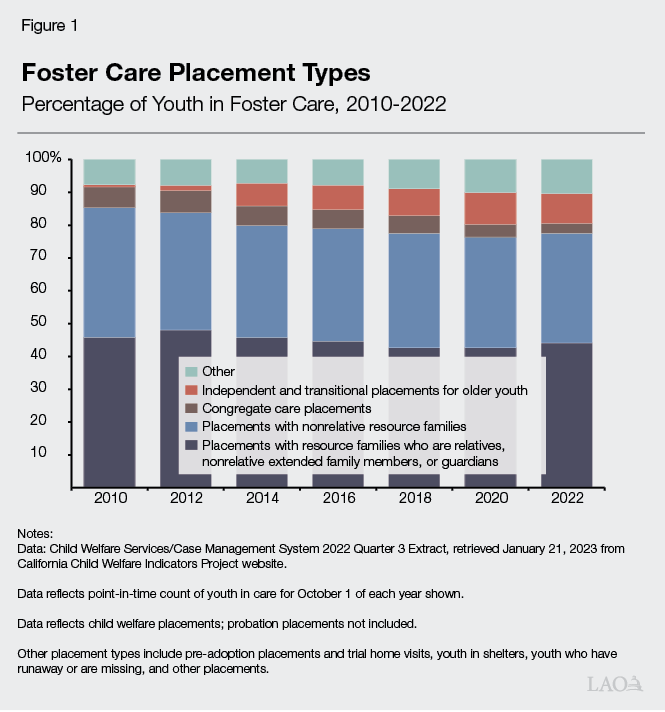

Total Foster Care Placements Have Remained Relatively Stable, With Shifts in Placement Types. Over the past decade, the number of youth in foster care has ranged from around 55,000 to 60,000 at any point in time. While the total number of placements has remained relatively stable, the predominance of various placement types has shifted over time. In particular, congregate care placements have decreased in line with the goals of CCR, while independent placements for older youth have increased since the implementation of EFC. Figure 1 illustrates changes in the proportions of foster placement types over time.

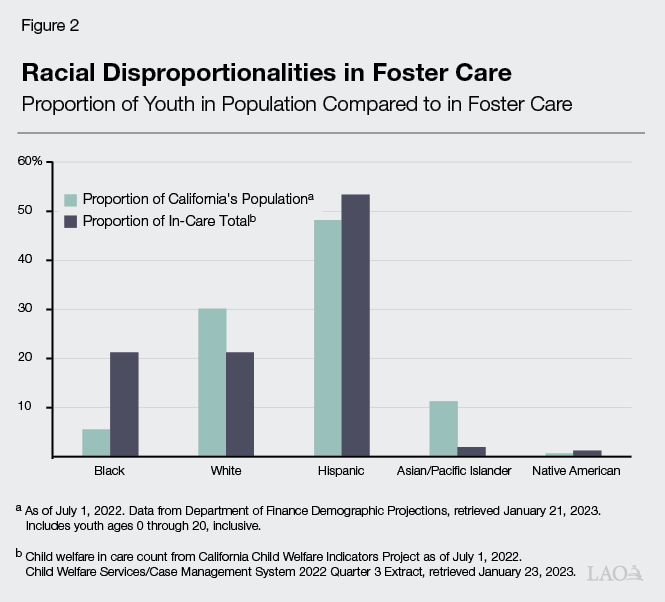

Foster Youth Are Disproportionately Low Income, Black, and Native American. A broad body of research has found that families impacted by child protective services are disproportionately poor and overrepresented by certain racial groups, and are often single‑parent households living in low‑income communities. In California, Black and Native American youth in particular are overrepresented in the foster care system relative to their respective shares of the state’s youth population. As illustrated in Figure 2, the proportion of Black and Native American youth in foster care is around four times larger than their proportion of the population in California overall. While the information displayed in Figure 2 is point in time, significant disproportionalities have persisted for many years. (The figure displays aggregated state‑level data; disproportionalities differ across counties.)

FFPSA. Historically, one of the main federal funding streams available for foster care—Title IV‑E—has not been available for states to use on services that may prevent foster care placement in the first place. Instead, the use of Title IV‑E funds has been restricted to support youth and families only after a youth has been placed in foster care. Passed as part of the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act, FFPSA expands allowable uses of federal Title IV‑E funds to include services to help prevent children and families from entering (or re‑entering) the foster care system. Specifically, FFPSA allows states to claim Title IV‑E funds for mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment services, in‑home parent skill‑based programs, and kinship navigator services once states meet certain conditions. FFPSA additionally makes other changes to policy and practice to ensure the appropriateness of all congregate care placements, reduce long‑term congregate care stays, and facilitate stable transitions to home‑based placements.

The law is divided into several parts; Part I (which is optional and related to prevention services) and Part IV (which is required and related to congregate care placements) have the most significant impacts for California. States were required to implement Part IV by October 1, 2021 in order to prevent the loss of federal funds for congregate care. States may not implement Part I until they come into compliance with Part IV.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Proposed Spending in 2023‑24 Decreases Compared to 2022‑23, Primarily Due to Expiration of One‑Time and Limited‑Term Funding. As shown in Figure 3, total funding for child welfare is proposed to decrease by more than $400 million General Fund ($270 million total funds) from the current year, 2022‑23, to the budget year, 2023‑24. This net change is the result of a new discretionary proposal ($10.6 million General Fund to help facilitate activities proposed as part of a federal Medicaid waiver demonstration project) and some automatic programmatic increases—primarily annual cost‑of‑living and caseload adjustments, estimated growth in county spending as a result of realignment growth, as well as some small funding augmentations to implement new legislation—which are more than offset by larger spending decreases due to the expiration of one‑time/limited‑term program augmentations. For example, funding for the previously authorized Excellence in Family Finding block grant program, Bringing Families Home program augmentation, and increase in emergency response is proposed to end in the current year (although expenditure authority will continue for a few more years). A more detailed accounting of the program changes resulting in the net year‑over‑year decrease is laid out in Figure 4, and the one new child welfare discretionary proposal is described more below.

Figure 3

Changes in Local Assistance Funding for Child Welfare

Includes Child Welfare Services, Foster Care, AAP, KinGAP, and ARC (In Millions)

|

Total |

Federal |

State |

County |

Reimbursement |

|

|

2023‑24 Governor’s Budget proposal |

$9,296 |

$3,168 |

$918 |

$4,995 |

$215 |

|

2022‑23 revised budget |

9,566 |

3,307 |

1,338 |

4,709 |

213 |

|

Change From 2022‑23 to 2023‑24 |

‑$271 |

‑$139 |

‑$420 |

$286 |

$2 |

|

Note: Does not include Child Welfare Services automation. |

|||||

|

AAP = Adoption Assistance Program; KinGAP = Kinship Guardianship Assistance Payment; and ARC = Approved Relative Caregiver. |

|||||

Figure 4

Drivers of Overall Child Welfare Net Spending Decrease

(In Millions)

|

Item |

Total Funds Change From 2022‑23 (Revised) to 2023‑24 |

General Fund Change from 2022‑23 (Revised) to 2023‑24 |

Description |

|

CalBH‑CBC Demonstration |

$14.0 |

$11.0 |

This amount reflects child welfare‑specific costs included in the proposed demonstration project. This initial funding amount is for child welfare social worker workload to participate in CFT meetings for Family Maintenance cases. Other costs are budgeted under DHCS. |

|

Net changes in CCR costs |

14.0 |

8.0 |

The net increase in CCR costs reflects increases in the HBFC rate and PPA, partially offset by decreases in CFTs, RFA backlog, and other program areas. See CCR table for more detail regarding these changes. |

|

SMHS documentation and notification to support continuity of care (AB 1051) |

3.2 |

2.6 |

Costs for additional social worker time to fulfill documentation and notification requirements when foster youth receiving SMHS are placed out‑of‑county, as required by Chapter 402 of 2022 (AB 1051, Bennett). Costs also include automation for data collection on foster youth receiving SMHS. Other costs are budgeted under DHCS. |

|

Case management activities for psychiatric residential treatment facilities (AB 2317) |

1.3 |

1.3 |

Costs for additional social worker time to conduct case management activities for youth placed in psychiatric residential treatment facilities, as required by Chapter 589 of 2022 (AB 2317, Ramos). |

|

Juvenile records access (SB 1071) |

1.1 |

0.8 |

Costs for additional social worker time to prepare juvenile case files for certain administrative hearings, as required by Chapter 613 of 2022 (SB 1071, Umberg). |

|

Family finding and investigations (SB 384) |

1.1 |

0.8 |

Costs for additional social worker time to investigate the names and locations of any alleged parents of children entering foster care, as required by Chapter 811 of 2022 (SB 384, Wiener). Costs also include one‑time county child welfare and probation department reporting costs. |

|

Documentation of family reunification services (AB 2866) |

0.2 |

0.1 |

Costs for additional social worker time to provide sufficient documentation during applicable status review hearings that FR services were provided or offered, as required by Chapter 165 of 2022 (AB 2866, Cunningham). |

|

Excellence in Family Finding and Engagement block grants |

‑308.0 |

‑150.0 |

One‑time grants in 2022‑23, expendable over five years, to local child welfare agencies for family finding, engagement, and support activities. Participating counties are required to provide matching funds equal to one‑half of the state funds. |

|

COVID‑19 temporary eFMAP |

‑111.0 |

— |

During the public health emergency, the federal government has been providing a 6.2 percent increase in the federal match rate (referred to as eFMAP). The eFMAP will begin to phase out April 1, 2023, and will drop to 0 as of January 1, 2024. |

|

Child welfare stabilization funding for Los Angeles County |

‑100.0 |

‑100.0 |

2022‑23 Budget Act included $200 million in 2022‑23 and $100 million in 2023‑24 ($300 million total over two years). |

|

Bringing Families Home program augmentation |

‑93.0 |

‑93.0 |

Limited‑term augmentation of $92.5 million provided in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 ($185 million total over two years). |

|

Increase in emergency response social worker funding |

‑68.0 |

‑50.0 |

Limited‑term augmentation of $50 million General Fund provided in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 ($100 million total over two years), to help local child welfare agencies respond to the public health emergency. |

|

Child abuse prevention federal grants augmentation |

‑43.0 |

— |

One‑time augmentation provided in 2022‑23 for various federal child welfare grant programs. |

|

Minor victims of commercial sexual exploitation |

‑25.0 |

‑25.0 |

One‑time augmentation in 2022‑23, expendable over three years, to support placement and services for youth who have been impacted by human trafficking, and to develop a specialized training curriculum for child welfare staff and other stakeholders who interact with these youth. |

|

STRTP provider IMD transition support |

‑10.0 |

‑10.0 |

Limited‑term support in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 for STRTPs that would be classified as IMDs, to assist them with transitioning program models in order to retain federal funding eligibility for SMHS. Additional funding is budgeted under DHCS. |

|

Reporting costs for removing barriers to placements with relatives (SB 354) |

‑7.0 |

‑5.0 |

One‑time funding in 2022‑23 for county manual data collection as required by Chapter 687 of 2021 (SB 354, Skinner) to compile and submit data on criminal records exemptions and denials for relative caregivers. |

|

Child welfare training additional support |

‑7.0 |

‑7.0 |

Limited‑term funding in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 for child welfare training additional support. |

|

RFA backlog resources |

‑6.0 |

‑4.0 |

One‑time funding in 2022‑23 to help counties address the RFA backlog by allowing counties to pay overtime for existing staff to expedite RFA application review. |

|

California Parent and Youth Helpline |

‑5.0 |

‑5.0 |

One‑time funding in 2022‑23, expendable over three years, to continue providing a support helpline for children and families who may be at risk of involvement with child welfare or entry to foster care. The helpline was initially funded as a pandemic emergency response initiative. |

|

Foster Youth Independence pilot program |

‑1.0 |

‑1.0 |

One‑time funding in 2022‑23 for case management and services to increase utilization of federal housing choice vouchers for former foster youth up to age 25, who are or are at risk of experiencing homelessness. |

|

Tribal technical assistance (AB 2083) |

‑0.1 |

‑0.1 |

One‑time funding in 2022‑23 to support tribal engagement with counties to develop tribal consultation protocols, as required by Chapter 815 of 2018 (AB 2083, Cooley). |

|

Other Net Changes |

479.0 |

6.0 |

This amount reflects the net effect of other changes across programs, including caseload changes, CNI COLAs, and estimated increases in county expenditures under 2011 realignment. |

|

Totals |

‑$271.0 |

‑$420.0 |

|

|

CalBH‑CBC = California Behavioral Health Community‑Based Continuum; CFT = Child and Family Team; DHCS = Department of Health Care Services; CCR = Continuum of Care Reform; HBFC = Home‑Based Family Care; PPA = Placement Prior to Approval; RFA = Resource Family Approval; SMHS = specialty mental health services; FR = family reunification; eFMAP = Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentages; STRTP = Short‑Term Residential Therapeutic Program; IMDs = Institutions for Mental Disease; CNI = California Necessities Index; and COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|||

Governor’s Budget Includes One Significant New Discretionary Proposal for Child Welfare. The Governor’s budget proposes $314 million General Fund ($6.1 billion total funds) for the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and DSS over five years to fund the California Behavioral Health Community‑Based Continuum Demonstration (CalBH‑CBC), effective January 1, 2024. A component of the ongoing California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal initiative, one goal of the proposed CalBH‑CBC is to deliver early interventions to reach children and families to help prevent entry into (or further involvement with) the child welfare system. In implementing CalBH‑CBC, the administration proposes to request a federal waiver to establish new preventative Medi‑Cal benefits, such as housing vouchers, joint DHCS/DSS home visiting programs, and stipends for youth extracurricular activities.

Specifically, for child welfare, the proposal includes $10.6 million General Fund ($14.5 million total funds) in 2023‑24 for DSS to fund increased child welfare social worker workload for participation in CFTs for certain families at risk of child removal. At full implementation, CalBH‑CBC funding under DSS would increase to around $33 million General Fund ($45 million total funds) and is proposed to include case management services to help facilitate home visiting programs (jointly administered by DSS and DHCS) and foster youth participation in extracurricular activities.

Comments on Governor’s Budget

Specific Objectives of Child Welfare CalBH‑CBC Funds Are Unclear. Certainly, the administration’s stated goal of the CalBH‑CBC child welfare funding—to deliver early interventions to reach children and families to help prevent entry into or deepened involvement with the child welfare system—is compelling. However, the specific anticipated outcomes to be achieved through the proposed funding amount is unclear. The Legislature could consider asking for more program detail—including the likelihood that the federal government would approve the waiver request in time for implementation to begin January 1, 2024, and specific objectives and outcome targets of the child welfare funding component—before deciding whether to approve, modify, or reject the Governor’s proposal.

For a more detailed overview and comments on the administration’s overall CalBH‑CBC proposal, refer to our Behavioral Health budget analysis.

Implementation Updates

In this section, we describe progress that DSS has made in implementing various programs funded in the current and prior years. We begin by describing the implementation of the major, ongoing initiatives that have been underway for several years and conclude with the newer, more recently funded efforts.

Long‑Term Implementation

First, we provide updates on two broad‑reaching and multifaceted programs: CCR and FFPSA. As described in the program background section, implementation for CCR has been ongoing for nearly ten years. FFPSA implementation began in California in 2021‑22 (although initial planning began earlier); full implementation—particularly of prevention services components—likely will take several years.

CCR. The state continues to work toward achieving all of its CCR goals in the current year. Several components of CCR have been fully implemented for a few years now and, overall, CCR is making progress toward achieving its overarching goals. Below, we provide updates on some CCR components of recent legislative interest, and Figure 5 displays the net costs of CCR budgeted in 2023‑24, relative to those in 2022‑23. (For a more extensive overview of these and additional CCR components, refer to our previous budget analysis.)

- Resource Family Approval (RFA) Processing Times. To become eligible to provide care to foster youth and receive foster care maintenance payments, households must complete the RFA process. The target for completing RFA is 90 days, but the state has yet to reach that target as an average or median processing time. As of November 2022, median approval time was 119 days (107 days for families with Placement Prior to Approval). This is a slight improvement from the third quarter of 2021, when median approval time was 120 days (109 days for families with Placement Prior to Approval). The 2022‑23 budget included both one‑time and ongoing augmentations to help counties process resource family applications in a timelier manner. One‑time funding of $4.4 million General Fund is being used in the current year to pay social worker overtime to help address the backlog, and ongoing funding of $50 million General Fund beginning in the current year will be allocated to counties to improve caregiver approval time lines permanently. At the time of publication, it is our understanding that DSS had not yet released any guidance or the specific county allocations for the $50 million augmentation.

- Foster Care Rates Development. The 2022‑23 budget package extended the date through which interim foster care rates—developed as part of the initial CCR implementation—shall remain operative. These rates are now in effect through December 31, 2024, with final rates expected to be implemented by January 1, 2025. DSS convened a number of stakeholder workgroups in the fall of 2022 to provide input into the permanent rate structure.Specifically, four workgroups were convened comprising relevant stakeholders to consider rates for: resource families, foster family agencies, intensive services foster care (ISFC), and STRTPs. The workgroup participants reached consensus around a number of key findings (that reflect the perspectives of workgroup participants and not necessarily that of DSS), including:

- The current rates are inadequate across all placement settings. Rates aim to support care and supervision but do not address the need for services/supports.

- Rates should follow the child and not the placement type; assessment should identify the child’s level of need, not where the child should be placed.

DSS is now working to develop a proposal for the permanent rate structure to be implemented by January 1, 2025 as required by statute. When DSS will share a draft of this proposal with the Legislature is not yet known.

- CFT Meetings. CFT meetings involve the youth, family members, and various professionals (for example, social workers, mental health professionals, and QIs) and community partners (for example, teachers) for the purpose of informing case plan and placement goals and strategies to achieve them. Since 2017, guidance from DSS has indicated that all foster youth and NMDs should receive CFT meetings within 60 days of entering care and periodically thereafter. In the current year, nearly all youth in foster care are receiving at least one CFT meeting at some point during their placement.

- Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) Assessments. In 2018, DSS selected the CANS assessment tool as the functional tool to be used in CFT meetings. CFTs began implementing the tool in 2019—with child welfare and behavioral health staff jointly responsible for completing all required CANS data. (The CANS tool also is used by the QI to meet FFPSA congregate care assessment requirements, as of October 1, 2021.) Guidance from DSS required child welfare agencies to begin entering CANS data into an automated system by July 1, 2021. However, when CANS assessments are completed by behavioral health staff and entered into the behavioral health reporting system, that data is not accessible through the child welfare system. Therefore, all CANS data is not currently available through a single system.

- Level of Care (LOC) Determinations. Beginning April 1, 2021, all home‑based family care placements with resource families were eligible to receive the basic rate or LOC rates 2 through 4 and ISFC, based on assessed need using the LOC Protocol Tool. As of July 2022, more than 14,000 placements had received an LOC assessment, and the proportion of those assessed as LOC 2 through 4 or ISFC was 53 percent. This is a moderate increase from a year prior, when fewer than 10,000 placements had received an LOC assessment and the proportion of those receiving a rate other than the basic rate was 31 percent.

- Potential of Using CANS Assessment for LOC Determinations. Stakeholders have raised various concerns with the LOC Protocol Tool since its implementation and have suggested that a CANS assessment module could be developed and used for rate determinations in lieu of a separate tool. DSS is in the early stages of working with the Praed Foundation to develop a potential Decision Support Model using CANS data that may be used for LOC determinations. Concurrently, DSS is providing technical assistance and support to counties to ensure CANS assessments are being conducted in a timely manner and with fidelity, in the context of CFTs. Additionally, DSS is working to build functionality of CANS automation into the new child welfare information technology system currently being developed (CWS‑California Automated Response and Engagement System [CWS‑CARES]) to support a CANS module potentially being used as the tool for LOC determinations.

Figure 5

Changes in CCR Budgeted Costs

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 Revised |

2023‑24 Governor’s |

Change |

||||||

|

Total |

Nonfederal |

Total |

Nonfederal |

Total |

Nonfederal |

|||

|

HBFC rate |

$271.3 |

$165.8 |

$294.3 |

$180.2 |

$22.9 |

$14.4 |

||

|

PPA (statutory change July 1, 2022) |

14.1 |

14.1 |

15.3 |

15.3 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

||

|

CANS (child welfare workload only) |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

2.9 |

‑0.1 |

‑1.1 |

||

|

CCR Reconciliation for 2019‑20 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

||

|

CCR—contracts |

7.7 |

5.6 |

7.6 |

5.6 |

‑0.1 |

— |

||

|

Second Level Administrative Review |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

||

|

CFTs |

95.3 |

69.6 |

91.9 |

67.6 |

‑3.4 |

‑2.0 |

||

|

RFA (funding for Probation Departments) |

5.8 |

4.2 |

5.8 |

4.3 |

— |

— |

||

|

RFA backlog (one‑time overtime funding for county social workers) |

6.1 |

4.4 |

— |

— |

‑6.1 |

‑4.4 |

||

|

Caregiver Approvala (ongoing augmentation to counties for RFA) |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

— |

— |

||

|

LOC Protocol Tool |

10.0 |

7.3 |

9.9 |

7.3 |

‑0.1 |

— |

||

|

SAWS |

0.5 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

‑0.5 |

‑0.2 |

||

|

Totals |

$465.0 |

$325.5 |

$479.0 |

$333.3 |

$14.0 |

$7.9 |

||

|

aThe administration does not include the Caregiver Approval premise as part of its CCR total. |

||||||||

|

HBFC = Home‑Based Family Care; PPA = Placement Prior to Approval; CANS = Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths; CCR = Continuum of Care Reform; CFT = Child and Family Team; RFA = Resource Family Approval; LOC = level of care; and SAWS = Statewide Automated Welfare System. |

||||||||

FFPSA. The state has continued to make progress toward implementing FFPSA in the current year. Below, we describe some key components that have yet to be fully implemented. (For a more extensive overview of these and additional FFPSA components, refer to our previous analysis.) In addition, 2022‑23 supplemental reporting language requires DSS to provide bi‑annual reports to the Legislature on the progress of FFPSA implementation. The first report was due to the Legislature by February 1, 2023. DSS has needed additional time to prepare the required data and now intends to provide the report in April 2023.

- State Prevention Plan. To opt in to Part I of FFPSA, states must submit a five‑year Title IV‑E prevention plan (state plan) to be approved by the federal Administration of Children and Families (ACF). A state plan must detail the state’s selection of evidence‑based prevention services; plans for identifying populations at imminent risk of entry or reentry into foster care (who may be assessed as candidates); and the approach that will be used to comply with federal evaluation, model fidelity, activity and outcome tracking and reporting, and safety and risk monitoring requirements. DSS submitted the state plan to ACF in August 2021 and received significant feedback and questions from ACF. In response, DSS submitted an updated state plan for federal approval in November 2022. This resubmission included several updates around California’s selection of evidence‑based practices (EBPs), eligibility and candidacy, target population for EBPs, implementation and continuous monitoring of EBPs, oversight of monitoring child safety, child welfare workforce training and support, and more. The complete state plan submitted to ACF in November can be viewed here, and a summary of changes from the August 2021 submission to the November 2022 submission can be found here. At the time of publication of this budget analysis, California’s state plan has not yet been approved by ACF.

- State Funding for Prevention Services. The 2021‑22 Budget Act included $222 million General Fund for one‑time block grants to assist counties with developing and implementing comprehensive prevention plans (CPPs), including specific EBPs that are newly eligible for Title IV‑E federal financial participation and included in the state prevention plan, described above. All 58 counties have expressed their intent to DSS to opt in to receive block grant dollars and are required to submit their CPPs to DSS by January 31, 2023. Prior to submitting their plans, counties also were required to complete capacity and readiness assessments and asset mapping and needs assessments to guide selection of Title IV‑E‑eligible EBPs and other prevention strategies. DSS has been providing technical assistance to counties as they prepare their CPPs. The department anticipates reviewing CPPs and disbursing grants in the coming months.

- Title IV‑E Claiming for EBPs. In order to begin claiming Title IV‑E funds for EBPs included in the state prevention plan, the state must be able to meet federal requirements around tracking per‑child prevention spending. Such tracking is beyond California’s child welfare data system’s current capacity, but will be incorporated into the forthcoming CWS‑CARES. We note that, based on historical progress of CWS‑CARES development, this solution could take significant time—potentially several years—to develop.

- Transition Support for STRTPs With 16+ Beds. In defining criteria for Qualified Residential Treatment Programs (QRTPs), the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established that Institutions for Mental Disease (IMDs) cannot be QRTPs and therefore would be ineligible for federal Medicaid financial participation. In particular, larger behavioral health facilities (those with 16 or more beds) would be defined as IMDs. In July 2020, DHCS requested that CMS exempt California’s STRTPs from being considered IMDs. CMS rejected this request and indicated that each STRTP must be reviewed individually to determine whether it should be deemed an IMD. DHCS was required to make these individual determinations by December 2022. To support facilities that would otherwise have been determined to be IMDs (those with 16+ beds) the 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budgets provided around $10 million in each year to help those facilities transition their program model. Thirteen STRTPs in total received transition funds. Of those, 12 facilities (with total capacity of 238 beds) have successfully transitioned their program models, while one facility (25 beds) ultimately has chosen not to transition. Two additional facilities (157 beds) opted not to receive transition funds. DSS and DHCS are in communication about the plan for the three non‑transitioned providers.

Implementation of Recently Funded Programs

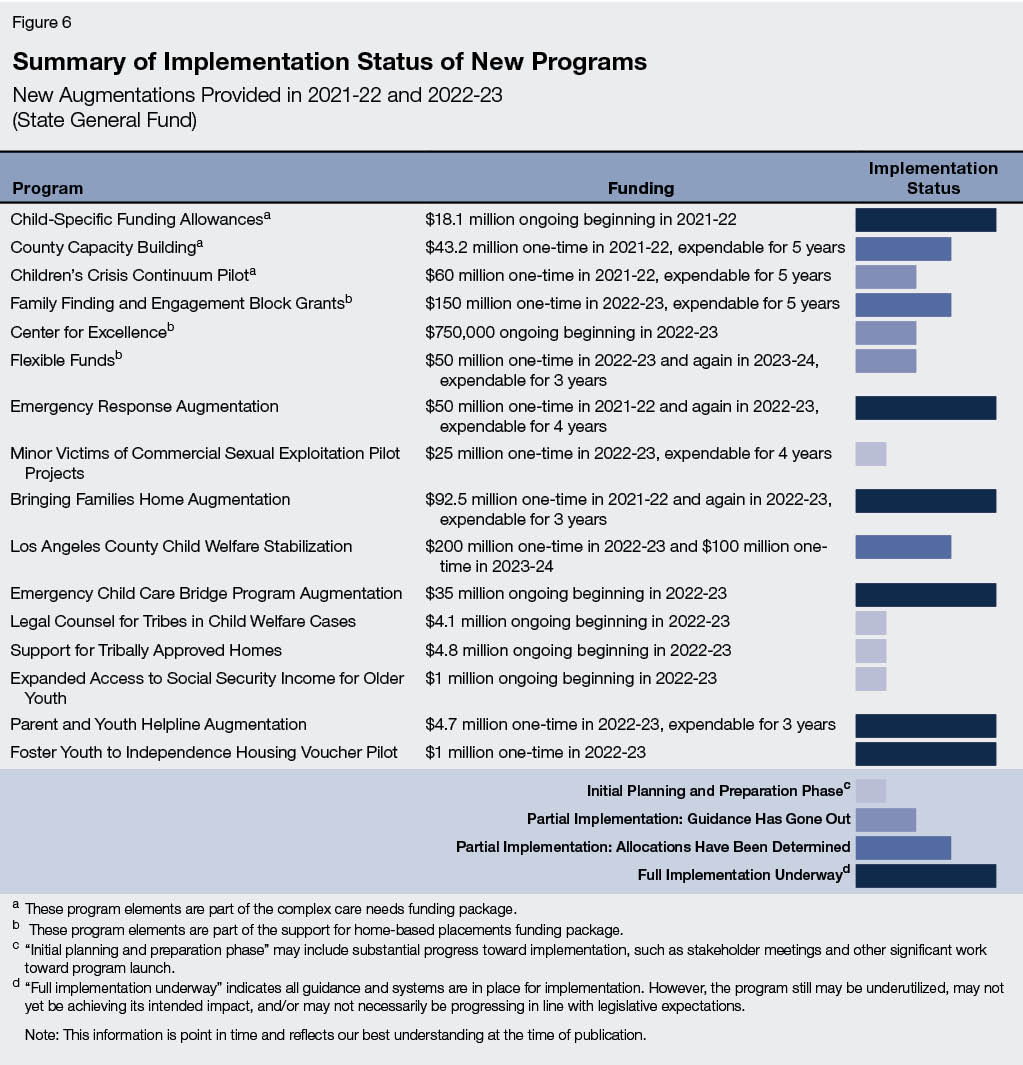

Next, we provide implementation updates on the numerous initiatives that have been newly created and/or received significant funding augmentations in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. Figure 6 summarizes the current implementation status of these programs and we provide more detailed updates below.

Improving Services for Youth With Complex Care Needs. Recent budgets have included significant augmentations to increase county capacity, placement and program options, and funding flexibilities for youth with complex behavioral health and other care needs. In part, recent augmentations also aim to ensure youth with complex needs can be served effectively within California to eliminate the need for out‑of‑state congregate care placements. Below, we provide updates on progress DSS and counties have made in implementing various funding components.

- Child‑Specific Funding Allowances. The 2021‑22 Budget Act provided $18.1 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and ongoing for individual foster youth with complex needs on a case‑by‑case basis. All counties are provided with an annual allocation, as determined by an allocation methodology developed by DSS in partnership with the County Welfare Directors Association (CWDA) and Chief Probation Officers of California (CPOC). To access their allocations, counties are required to complete and submit a child‑specific funding template for each youth who benefits from the funds. The template details the youth’s assessed needs related to behavioral health, permanency and family finding, and placement challenges, as well as any extraordinary developmental or medical needs. As of October 2022, $4.5 million from 2021‑22 funds and $3 million from 2022‑23 funds had been approved for 111 requests.

- County Capacity Building. The 2021‑22 Budget Act also provided $43.2 million General Fund one time to assist counties in the up‑front costs of establishing a high‑quality continuum of care designed to support foster youth in the least restrictive setting possible. All counties are provided with a total allocation and the funding is available for five years (through June 30, 2026). To access their allocations, counties are required to submit proposals to DSS (proposals can be submitted yearly or on a one‑time basis). Guidance from DSS indicates that potential uses for the capacity building funding include:

- Establishing specialized foster care models such as ISFC.

- Funding therapeutic foster care, which is a specialty mental health service.

- Providing intensive child‑specific recruitment, family finding, and engagement.

- Developing specialized models of home‑based care, such as high‑fidelity wraparound and community‑based treatment programs, to act as alternatives to congregate care placements.

- Contracting with highly specialized STRTPs for youth who otherwise might have been placed in an out‑of‑state congregate setting. As of October 2022, three counties had submitted proposals to access this funding. DSS anticipates that additional counties will submit plans in the coming months, as the department has consulted with and provided technical assistance to several other counties.

- Children’s Crisis Continuum Pilot Project. The 2021‑22 Budget Act created the Children’s Crisis Continuum Pilot Project, an initiative to be jointly administered by DSS and DHCS, and provided $60 million General Fund to fund the pilot on a one‑time basis, with funds available for five years (through June 30, 2026). The aim of the pilot is to allow counties to develop a robust, highly integrated continuum of services designed to serve foster youth who are in crisis—addressing currently perceived gaps in the existing array of crisis response services. According to guidance from the departments, the primary function of the pilot program will be to provide therapeutic interventions, specialized programming, and short‑term crisis stabilization, and to ensure youth are able to transition seamlessly between placement settings and health care programs as needed. DSS and DHCS developed a Request for Proposal (RFP) process to solicit funding applications from counties; the departments released the RFP in July 2022 and proposals were due December 1, 2022. Eight counties have applied and DSS anticipates sending notice of intent to award grants to awardees by the end of February 2023.

Increasing Support for Home‑Based Placements. Recent budgets also have included significant augmentations to help ensure as many foster youth as possible can receive all needed individualized supports in home‑based settings, thereby reducing reliance on congregate care. Below, we provide updates on progress DSS and counties have made in implementing two main funding components.

- Excellence in Family Finding, Engagement, and Support Block Grants. The 2022‑23 Budget Act included $150 million one time in 2022‑23, available for five years (through June 30, 2027), to fund block grants to counties and tribes to supplement family finding, engagement, and support activities. Budget language established the program, specifying that DSS shall:

- Develop the allocation methodology in consultation with CWDA, CPOC, and tribes.

- Make funds available by March 1, 2023.

- Establish procedures for program data collection and reporting to include specific measures described in statute.

Statute also requires counties that elect to participate in the program to:

- Provide a match of local funds, equal to half of state funds provided.

- Hire (or contract for) family finding workers to be dedicated to the program full time.

DSS released initial guidance and county allocations in February 2023. According to the guidance, counties opting in to the program will need to submit a written plan to DSS for approval and will be able to access their allocations as of the date their plan is approved. Plans will be reviewed on a rolling basis; counties may submit plans up until June 30, 2025. Detailed claiming information will be made available via forthcoming fiscal guidance.

- Center for Excellence in Family Finding. The 2022‑23 budget package established the state Center for Excellence (CFE) in Family Finding under DSS. Statute specifies that the Center will provide training and technical assistance to help increase and stabilize placements with and connections to relatives (including tribes). DSS has contracted with the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) to house CFE. According to the initial information released by the department in February 2023, CFE will become operational March 1, 2023 and will conduct training and technical assistance for counties and tribes that opt into the family engagement block grant program, described above. In preparing to launch CFE, DSS and UC Davis held initial peer learning sessions in October and November 2022, and conducted a number of stakeholder meetings in January and February 2023 to determine what specific services and supports are most needed from CFE. As a result, CFE’s trainings and technical assistance will include:

- Conducting evidence‑based, organization‑specific assessments of quantitative and qualitative data related to permanency outcomes and operations.

- Strengthening trauma‑informed permanency practices and programs.

- Developing workforce capacity around supporting permanency and family finding and engagement.

- Providing guidance and research on the latest high‑fidelity, evidence‑based permanency and family finding and engagement models and practices.

- Providing peer‑to‑peer learning opportunities for counties, tribes, and providers to share and leverage best practices and program sustainability.

- Fostering a culture of diversity and inclusion that actively invites the contribution and participation of those who are most impacted and is representative of diverse identities and communities.

-

Flexible Funds. The 2022‑23 Budget Act also included $50 million one time in 2022‑23 (with another $50 million in 2023‑24), available for three years, to be allocated to counties and tribes to provide support for foster youth and caregivers on a case‑by‑case basis. Budget language specified intended uses for the funds, including:

- Respite care for foster caregivers.

- Costs to facilitate participation in enrichment activities.

- Supports to enable a youth’s connections with relatives/tribe.

- Costs to facilitate a youth’s placement with a relative who otherwise would be unable to take the placement due to housing arrangement limitations.

In January 2023, DSS published guidance for counties (with additional guidance for tribes forthcoming) specifying requirements to access these funds, along with specific claiming instructions. The department also released individual county allocations via a separate fiscal letter. According to the guidance, counties intending to use their allocations will be required to submit a letter of intent to DSS; letters will be accepted on a rolling based through July 1, 2024. Counties that elect to use their allocations also must submit an annual reporting and evaluation form. The form, which DSS included in its January guidance, will be used to collect information about the outcomes achieved as a direct result of the funding claimed. If counties claim funds for the specific uses detailed in the budget language, no prior notification or application is required. However, if counties would like to use their funding for a different purpose, they are required first to submit a request to DSS and receive written authorization prior to claiming the funds.

Emergency Response Augmentation. The 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budgets each provided $50 million General Fund one time, expendable for four years, to enhance counties’ emergency response services. DSS released guidance for the 2021‑22 funds in December 2021, requiring counties to opt in by March 1, 2022. Additionally, DSS released guidance for the 2022‑23 funds in December 2022; counties will be required to opt in for this second round of funding by March 1, 2023. Counties electing to receive funds are required to develop and submit plans to DSS, which the department must approve prior to counties claiming funds. The guidance details examples of potential uses for the funds, such as hiring additional emergency response social workers, supervisors, or support staff, and increasing pay or other incentives for emergency response staff. Counties also will be required to submit annual plan updates to DSS, with the first annual update due on June 30, 2023. According to initial county claims data, more than $35 million had been claimed as of January 2023.

Pilot Projects to Support Minor Victims of Commercial Sexual Exploitation. The 2022‑23 budget provided $25 million one time, available for four years, to administer contracts to community organizations for pilot programs to develop innovative placement continuums for youth who are, or at risk of becoming, victims of commercial sexual exploitation. Funding for the pilot programs is a one‑time augmentation to California’s ongoing federally and state‑funded commercially sexually exploited children (CSEC) programs, which aim to prevent exploitation, provide various services to victims and those at risk, and provide specialty training on CSEC to social workers. Statute specifies that the pilot programs must meet certain criteria, such as providing intensive trauma‑informed services for youth and their caregivers during recovery, peer and survivor support groups, and specialized training for impacted youths’ caregivers. Statute further requires DSS to provide to the Legislature two reports: one by January 1, 2024 identifying gaps in the service array for youth who have been exploited, and the second by June 30, 2027 discussing the implementation and outcomes of the funded pilot programs. As of November 2022, DSS had determined the specific project areas and selected some of the organizations who will conduct the pilots:

- $7 million for a Bay Area pilot by the Department on the Status of Women.

- $7 million for a rural regional pilot by the Children’s Legacy Center.

- $10 million for a Southern California pilot, which DSS intends to release for competitive bid in March 2023 (for a contract start date toward the end of the calendar year).

- $1 million to fund training contracts.

Bringing Families Home (BFH) Program Augmentation. BFH provides housing supports and services to families receiving child welfare services who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness. The goal of BFH is to increase family reunification and prevent foster care placement among participants in cases where housing instability prevents reunification or could lead to foster care placement. BFH is a county/tribal optional program supported by General Fund resources and requiring a dollar‑for‑dollar local match. The 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budgets each provided an augmentation of $92.5 million, expendable for three years, and accompanying budget language exempted participating counties and tribes from the match requirement. Fifty‑one counties and one tribe are receiving 2021‑22 funds. DSS reported that as of June 2022, BFH had served more than 3,900 families since the beginning of program implementation. According to initial findings of an ongoing program evaluation, of families who exited the program during the first two years of funding, around half exited to permanent housing, 14 percent exited to community‑provided or temporary housing, and 3 percent were experiencing homelessness upon exit. (Remaining exiting families left the program without a reported destination.) Regarding the 2022‑23 funds, DSS published allocations in December 2022, indicating 53 counties and one tribe have opted in. Further, DSS established a program update schedule and is requiring participating counties and tribes to report on various program outcome measures. The first report on 2021‑22 funding outcomes was due to DSS January 20, 2023. Some counties have needed extensions to prepare the required data; DSS anticipates having key findings from the surveys in late February.

Los Angeles County Child Welfare Stabilization. The 2022‑23 budget included $200 million (and an additional $100 million in 2023‑24) for Los Angeles County to increase funding for family reunification services, prevention services implementation, and other activities upon the expiration of federal funding certainty grants, which had been provided to counties that participated in Title IV‑E waiver demonstration projects. (The federally approved projects allowed participating counties to use their Title IV‑E dollars more flexibly. The projects ended in 2019, and from 2019 until 2021, the federal government provided step‑down grants to help counties transition.) To demonstrate these funds supplement and do not supplant existing child welfare funding, statute specified Los Angeles County shall provide its 2011 realignment balances to DSS. Based on consultations with Los Angeles County, DSS determined that funds will be provided on a reimbursement basis. In January 2023, DSS issued the specific allocations for child welfare and probation along with templates that social workers and probation officers will use to invoice funds. In addition, DSS issued the templates that county workers will use to report their 2011 realignment balances.

Emergency Child Care Bridge Augmentation. The Emergency Child Care Bridge program aims to stabilize foster placements by providing time‑limited child care vouchers for resource families and by providing child care navigators to assist eligible families in accessing long‑term subsidized child care. In addition, the program provides trauma‑informed training to child care providers working with child welfare system‑impacted children. Prior to the current year, vouchers could be provided for up to 12 months. The 2022‑23 budget provided an ongoing augmentation of $35 million to expand access to the program, and accompanying language directed DSS to develop guidance specifying that effective September 1, 2022, counties may extend vouchers beyond 12 months based on a compelling reason. Budget‑related legislation also adjusted the eligibility criteria for vouchers to include parents who work or attend school from home. DSS published the required guidance on September 26, 2022. While the funding augmentation for 2022‑23 has been disbursed to counties, data on impacts of the expanded funds—for example, how many families have received vouchers beyond 12 months—are not yet know.

Legal Counsel for Tribes in Child Welfare Cases. The 2022‑23 budget provided $4.1 million General Fund ongoing to provide resources for legal counsel to represent tribes in Indian child welfare dependency cases. In implementing this new assistance component, DSS is in the process of holding consultations with tribes, and intends to enter into memorandums of understanding with participating tribes by May 1, 2023. All 109 of California’s federally recognized tribes are potentially eligible; tribes wishing to receive assistance will be required to submit a letter of interest by April 7, 2023. DSS anticipates around 70 to 80 tribes will opt in. Based on tribal interest, DSS plans to issue allocations to individual tribes in June 2023.

Support for Tribally Approved Homes. The 2022‑23 budget provided $4.8 million General Fund ongoing to support tribes in increasing recruitment and approval of tribally approved homes for the purpose of foster or adoptive placement for Indian children, pursuant to the Indian Child Welfare Act. DSS intends to release initial draft guidance and consult with tribes beginning in mid‑ to late February. Similar to the process for implementing support for legal counsel for tribes, described above, tribes will be able to opt in and DSS anticipates providing allocations by June 2023.

Expanded Access to Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for Older Youth. The 2022‑23 budget provided around $1 million General Fund ongoing for increased county workload to facilitate access to federal SSI benefits for eligible older foster youth. Budget language described additional steps that county child welfare agencies must take around submitting initial applications, reconsiderations, appeals, and redeterminations to the federal Social Security Administration for youth ages 16‑18, and directs DSS to develop guidance to this effect. Budget‑related legislation further specified these new county requirements would take effect January 1, 2023, or 30 days after DSS issues the guidance, whichever is later. At the time of publication, DSS had not yet issued the required guidance; the department indicated it aims to release the guidance by the end of February 2023.

Parent and Youth Helpline Augmentation. The California Parent and Youth Helpline provides phone, e‑mail, video chat, and group support to children and their families who may be at risk of involvement with the child welfare system or entry to foster care. An emergency contract for the helpline was initially funded in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic; the current $3.7 million contract is valid through June 30, 2023. The 2022‑23 budget provided a $4.7 million General Fund one‑time augmentation to fund the helpline for an additional three years. From May 2020 through August 2022, the helpline received over 40,000 texts, e‑mails, and other communications from youth and parents in total. In addition, nearly 300 parents participated in online support groups.

Foster Youth to Independence (FYI) Housing Voucher Pilot. The federal FYI program, administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), provides housing vouchers for former foster youth up to age 25 who are, or are at risk of, experiencing homelessness. HUD implements the program through local public housing authorities who are required to coordinate with local child welfare agencies to provide recipient youth with supportive services (such as counseling on lease agreements, basic life skills and money management training, and education and career preparation assistance) for 36 months while the youth receives the housing vouchers. To help fund the required supportive services component of FYI for one year and encourage more California public housing authorities to opt in to administer the federal vouchers, DSS dedicated $4 million in supplemental flexible federal Chafee dollars (received for the federal fiscal year 2020‑21), which were expendable through September 2022. The 2022‑23 budget provided an additional $1 million General Fund to ensure supportive services could be maintained beyond September 2022 for the required 36 months of the program.

Comments and Questions

In this section, we provide comments and questions for the Legislature to consider. Given the numerous new activities being implemented across child welfare—and considering that there is only one significant new proposal included in the 2023‑24 Governor’s Budget—most of our comments focus on some key areas for Legislative oversight of ongoing implementation.

Implementation Is Underway for Most Major New Child Welfare Funding Provided in Current and Prior Year… As summarized in Figure 6 and described above, DSS has begun implementing most of the new initiatives and significant program augmentations funded by recent budgets. In general, the department has provided implementation guidance (where needed) within around six months and counties have been able to commence activities within around a year of the Legislature providing funding through budget acts (although the planning period for comprehensive prevention services has been notably longer).

…But Still Too Early to Fully Assess Impact. Even for programs we have categorized as “full implementation underway” in Figure 6, assessing what is actually being achieved remains challenging. In many cases, it remains too early to assess any implementation trends, particularly impacts and outcomes for youth and families (more on this point below). We note that DSS is planning evaluation contracts to assess certain programs, but those results will not be available for quite some time.

Seek Information to Better Understand Any Implementation Challenges and Identify Potential Areas to Streamline. As noted throughout this brief, in many cases, the department has taken 6 to 12 months or longer to develop guidance and launch new program activities. We acknowledge that DSS has received numerous significant allocations for new/expanded child welfare programs over the past few years, while simultaneously managing all the programmatic changes that resulted from the pandemic. Within this context, certainly some lead time between funds being provided through the annual budget process and program implementation launch is to be expected.

To help the Legislature improve its ability to track the implementation time lines of the many new programs across DSS, the Legislature could ask the department to provide more detailed anticipated timelines for implementation up front. This could help the Legislature more easily monitor progress of the many various moving pieces as implementation begins.

In addition, the Legislature could direct the department to report on: Why developing guidance requires the amount of time it does, what challenges have arisen and required additional time to address, and what any unanticipated obstacles have been.

Ultimately, the Legislature could use this information to determine whether the department has sufficient resources to undertake this many new programs simultaneously. The Legislature also could use this information to shape future budget‑related legislation to help ensure new program launch may proceed as seamlessly as possible.

Furthermore, to help ensure augmentations for programs that are of the highest legislative priority are able to begin implementation as quickly as possible, the Legislature also could consider directing the department to prioritize implementation of various new programs in a certain order.

Continue to Seek Opportunities to Hear Directly from Youth and Families to Help Ensure Legislative Expectations Are Being Met. As referenced throughout this brief, publicly available guidance and other information shared by DSS can help the Legislature track DSS’s efforts to implement various new child welfare programs—in terms of tracking the specific actions the department is taking. In addition, once implementation has been ongoing for some time, data collection and required reporting can help provide some insight into overall programmatic outputs. However, more nuanced tracking around progress, impacts, and outcomes at the local level for individual youth and families—and how actual implementation ultimately meets or falls short of legislative expectations—may be less clear. To gain a deeper understanding of the extent to which funding is achieving the Legislature’s intended impact and goals for youth and families, we recommend the Legislature continue to seek input directly from stakeholders—including youth and families—as feasible. In addition to regular oversight and budget hearings, other opportunities to hear directly from system‑involved youth and families could include partnership with the California Health and Human Services Agency’s Child Welfare Council and the newly created Youth Empowerment Commission housed under the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research.

Forthcoming Final Rates Structure Will Be Important to CCR’s Overall Success. As described above, DSS is in the process of preparing a proposal for the final rate structure under CCR, which is statutorily required to be implemented by January 1, 2025. The Legislature may wish to ask the department to commit to a more specific time frame for introducing its final rates proposal to ensure sufficient time for legislative and stakeholder review and given the importance of the final rates to the success of CCR’s objectives.

Forthcoming Report on FFPSA Implementation Will Provide Oversight Opportunity. As noted above, the administration now intends to provide the first required supplemental reporting language report on FFPSA implementation in April 2023. We anticipate the data and information provided in this report will provide an opportunity for deeper understanding around how implementation of FFPSA Parts I and IV is progressing and where challenges may remain. We will review the report when it becomes available and share our feedback with the Legislature as applicable at that time.