May 15, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Initial Comments on the

Governor’s May Revision

Key Takeaways

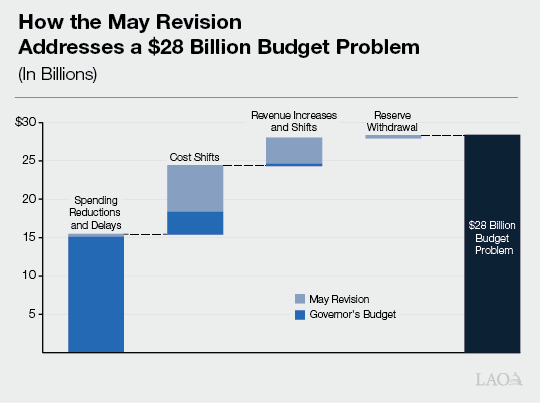

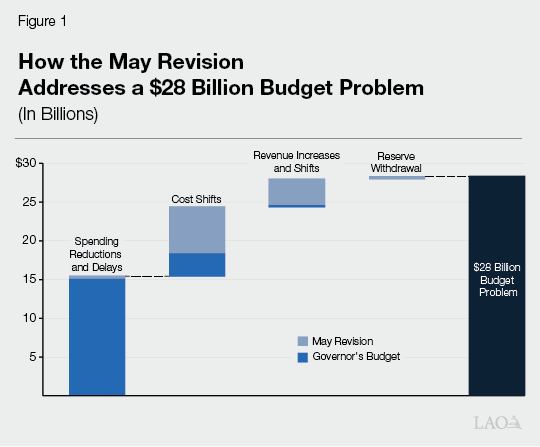

Governor’s May Revision Solves a $28 Billion Budget Problem. The figure below summarizes the budget solutions that the Governor proposes using to address the $28.3 billion budget problem. As the figure shows, while the January Governor’s budget focused primarily on spending solutions, the May Revision solves much of the additional budget problem by shifting more costs and increasing revenues. That said, spending solutions still represent about half of the total proposals. Total budget solutions proposed in the May Revision (including those maintained from Governor’s budget) are: $15.1 billion in spending reductions and delays, $9.1 billion in cost shifts, $3.7 billion in revenue increases and shifts, and $450 million in reserve withdrawals.

Although Revenues Are Always Uncertain, May Revision Predicated on Optimistic Estimates. The administration points out that there is elevated uncertainty in this year’s revenue outlook. Significant revenue uncertainty, however, is not unique to this year. Due to economic unknowns, policy changes, and other potential disruptions, revenues forecasts are always uncertain. This year, as always, we advise adopting the best possible revenue estimate based on all available economic and revenue data. We do not view revenue uncertainties as a cause for inaction or a reason to adopt optimistic revenue assumptions. Based on our assessment, there is a roughly two‑thirds chance revenues will come in below May Revision estimates. As such, while we consider the May Revision revenues plausible, adopting them would present considerable downside risk.

Adopting Administration’s Revenue Estimates Sets Up Difficult January. Under our revenues, and after accounting for constitutional spending requirements, the budget problem for 2023‑24 is $6.2 billion larger than the administration’s estimates. The state currently has $11 billion in one‑time or temporary spending planned for 2023‑24—amounts that could be reduced to address this larger budget problem. Doing so now—in response to our lower revenue projections—would be better than waiting until next year for a few reasons. Once the new fiscal year begins, state departments will begin obligating and distributing these funds as planned. As such, midyear pullbacks would need to be based on what money has gone out the door instead of the state’s priorities. This approach could be particularly disruptive to program participants who would have planned on receiving the funds. Moreover, the administration will have an information advantage—it knows better what money has or has not been dispersed—making it more challenging for the Legislature to exert its preferences in response. While using some reserves at that time could be reasonable, the Legislature could still face difficult decisions to ensure the budget is on sound fiscal footing in future years.

Introduction

On May 12, 2023, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (This annual proposed revised budget is called the “May Revision.”) In this brief, we provide a summary of and comments on the Governor’s revised budget, focusing on the overall condition and structure of the state General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail and provide additional comments in hearing testimony. The information presented in this brief is based on our best understanding of the administration’s proposals as of May 13, 2023. In many areas of the budget, our understanding will continue to evolve as we receive more information.

$28 Billion Budget Problem

In this section, we present our estimates of the budget problem the Governor addressed in the May Revision budget proposal. Importantly, the estimates in this section are predicated on the administration’s revenue projections. As we discuss later in this report, the administration’s revenue projections are optimistic. Under our own projections, the budget problem would be larger.

What Is a Budget Problem? A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when resources are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. Under the State Constitution, a budget problem must be solved, for example, by increasing revenues or reducing spending. Due to a deteriorating revenue picture relative to expectations from June 2022, both our office and the administration have anticipated the state faces a budget problem in the 2023‑24 budget process. (The budget problem is calculated across the budget window—that is, the three fiscal years under review in the budget process. In this case, those years are: 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24.)

The Budget Problem

We Estimate the Governor Solved a $28.3 Billion Budget Problem in the May Revision. Our estimate of the budget problem is slightly lower than the $31.5 billion figure cited by the administration. The reasons for our differences are generally the same as those we cited at the Governor’s budget, including the cost of certain assumptions and policies that the administration included in the baseline, but had not been adopted. For example, the administration’s estimates included an assumption about the costs of inflation in future years that was not current law. We explained those differences in more detail in our report, The 2023‑24 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget.

Budget Problem Increased $10.4 Billion Since January. We estimate that, under the administration’s policies and assumptions, the budget problem grew by $10.4 billion since the administration’s January projections in the Governor’s budget. There are a range of factors, some offsetting, that contribute to the growing budget problem. They are:

- Revenues Lower by $9.4 Billion. The administration’s baseline revenue estimates (that is, excluding constitutionally required reserve deposits and policy choices) are lower by $8.4 billion across the three‑year budget window compared to January estimates. (The total also includes about $1 billion in revenue adjustments attributable to 2020‑21 and earlier.) This increases the size of the budget problem.

- Constitutional Requirements Lower by $2.7 Billion. Reflecting these lower revenue estimates, the administration’s estimates of General Fund constitutional requirements (including school and community college spending, reserve deposits, and debt payments) are lower by $2.7 billion. This partially offsets the revenue decrease described above, reducing the size of the budget problem.

- Spending and Other Adjustments Increase Budget Problem by $2.7 Billion. Across the budget, baseline spending (meaning, spending under current law) is higher than Governor’s budget estimates by $2.7 billion. Some of the contributors to this increase include baseline costs in Medi‑Cal and In‑Home Supportive Services. Higher baseline spending increases the size of the budget problem.

- New Discretionary Spending of Over $700 Million. We estimate the Governor proposed additional discretionary spending of over $700 million in the May Revision. This adds to the $2.2 billion in discretionary spending proposed in January for a total of $2.9 billion. A forthcoming appendix also provides a list of these proposals, which increase the size of the budget problem. The nearby box includes more information on how we categorize adjustments for universities, courts, and employee compensation.

Adjustments for Universities, Courts, and Employee Compensation

We define discretionary spending as new spending not required under current law or policy. We generally do not assume annual cost increases for inflation and other cost pressures, except where the Legislature has a practice of enacting them. Programs for which the Legislature generally has provided these increases include: universities, employee compensation, and courts. In these cases, as long as the administration’s proposed increase is consistent with our estimate of underlying cost pressures, we do not consider the augmentation to be discretionary. For example, the Governor proposes $443 million to provide 5 percent base General Fund increases for the universities, which we do not include in the forthcoming Appendix on discretionary spending. That said, to address the budget problem, the Legislature could choose to provide a lower amount for universities and other similar items.

How the Governor Proposes Solving the Budget Problem

The State Constitution requires the Legislature to enact a balanced budget, which means the Governor must propose solutions when the administration estimates the state faces a deficit. The state has many types of solutions—or options—for addressing a budget problem, but the most important include: reserve withdrawals, spending reductions, revenue increases, and cost shifts (for example, between funds).

Figure 1 summarizes the budget solutions that the Governor proposes using to address the $28.3 billion budget problem. As the figure shows, while the January Governor’s budget focused primarily on spending solutions, the May Revision solves much of the additional budget problem by shifting more costs and increasing revenues. That said, spending solutions still represent about half of the total proposals. Total budget solutions proposed in the May Revision (including those that persisted from the Governor’s budget) are: $15.1 billion in spending reductions and delays, $9.1 billion in cost shifts, $3.7 billion in revenue increases and shifts, and $450 million in reserve withdrawals. The remainder of this section describes each of these components in more detail. (In this figure and throughout the report, some of the estimates cited here for the Governor’s budget might not match estimates provided in our Overview of the Governor’s Budget, published in January. In these cases, our understanding of the proposals has evolved since we published that report.)

$15.1 Billion Spending‑Related Solutions

The Governor’s May Revision includes $15.1 billion in spending‑related budget solutions, a slight increase relative to the Governor’s budget. That said, although spending reductions increased on net, the May Revision also withdraws some spending reductions proposed in January. For example, the May Revision retracts the proposed reduction to the Court Appointed Special Advocate program and proposes using an alternative fund source for a portion of the Behavioral Bridge Housing program, rather than a General Fund delay.

The May Revision spending proposals can be categorized into three types: reductions, delays, and reductions subject to trigger restoration. Nearly all of these solutions would apply to one‑time and temporary spending. The forthcoming appendix provides a list of these proposed solutions. The remainder of this section describes each of these types in turn.

$6.3 Billion in Delays. We define a delay as an expenditure reduction proposed for the budget window (2021‑22 through 2023‑24) with an associated cost increase in a future year of the multiyear (2024‑25 through 2026‑27). That is, the spending would be moved to a future year. Less than half of the Governor’s spending‑related solutions are delays. For example, the Governor proposes delaying: $550 million in grants for early education facilities from 2023‑24 to 2024‑25 and $550 million for broadband last‑mile project grants from 2023‑24 to future years. To the extent budget problems persist—as we anticipate is likely—the Legislature will have to revisit these and other spending augmentations again.

$5.1 Billion in Reductions. We define a spending reduction as the elimination of an augmentation previously approved under current law or policy. The May Revision includes $5.1 billion in reductions, the largest of which is withdrawing a discretionary principal payment on state’s unemployment insurance loan (which otherwise is paid by employers’ payroll taxes). The May Revision also includes a proposal to delay providing ongoing General Fund for financial assistance to Covered California enrollees, freeing up $304 million. About one‑third of the Governor’s spending solutions are reductions.

$3.7 Billion in Reductions Subject to Trigger Reduction. The May Revision proposes making one‑quarter of all spending‑related solutions subject to trigger restoration language. Under this proposed language, program spending that otherwise would have occurred in 2023‑24 would not be allocated as part of the June budget act. However, if in January 2024 the administration estimates there are sufficient resources available to fund these expenditures, those programs would be restored halfway through the fiscal year. Many of the spending solutions in natural resources and environment, transportation, and housing and homelessness are subject to this trigger restoration language. That said, our revenue estimates suggest it is unlikely that these trigger restorations can be afforded in 2023‑24. As such, the Legislature should consider these solutions as spending reductions.

$9.1 Billion Cost Shifts

We estimate the May Revision includes $9.1 billion in cost shifts, a $6 billion increase relative to January. Cost shifts occur when the state moves costs between entities, fund sources, or across fiscal years. For example, shifting spending from the General Fund to special funds or, as has been done in prior budgets, shifting costs from the state to local governments. Major cost shift proposals in the May Revision include: (1) $2 billion in loans from special funds (and other state funds) to the General Fund; (2) a shift of $1.1 billion in costs for zero‑emission vehicles from the General Fund to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; (3) early reversion of unspent funds in General Child Care (as estimated by the Department of Finance) and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs); and (4) shifts in a variety of capital outlay projects from General Fund cash to bonds, for example for climate projects, student housing, and clean energy projects. (Bonds associated with the climate projects and clean energy would require voter approval to move forward.) While swapping bonds for General Fund is a reasonable response to weakening fiscal conditions, the merits of the individual projects proposed warrant scrutiny, especially given that with higher interest rates, the related debt servicing costs will be higher into the future. The forthcoming appendix provides a full list of these proposed cost shifts.

$3.7 Billion Revenue‑Related Solutions

The May Revision includes $3.7 billion in revenue‑related solutions, an increase of $3.4 billion from January. The main proposal in this area is a renewal and increase in a tax on health insurance plans known as the managed care organization (MCO) tax. Under the proposal, the tax would last from April 2023 through December 2026 and be used to maintain and augment support for Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. The tax also requires approval from the federal government to be used to draw down federal funding to support Medi‑Cal. We estimate that, in 2023‑24 specifically, the MCO tax proposal would provide $3.5 billion to address the budget problem. In addition, the May Revision proposes reverting $200 million in unspent funds associated with the Middle Class Tax Refund to the General Fund.

$450 Million Reserves

Uses $450 Million From the Safety Net Reserve. The 2018‑19 budget created the Safety Net Reserve to set aside funds for future costs of two programs—CalWORKs and Medi‑Cal—in the event of a recession. Absent policy changes, these programs typically experience increased expenditures during a recession when unemployment increases and program caseloads rises. The reserve has a balance of $900 million and the May Revision proposes using half of that to address the budget problem in 2023‑24.

Maintains State’s Constitutional Reserves. The state has two main constitutional reserve accounts: the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), which can help address a budget problem, and the School Reserve, which can supplement otherwise required spending on schools and community colleges (and cannot help address the budget problem). In order for the state to make discretionary withdrawals from either of these accounts, the Governor must declare a budget emergency. Although a budget emergency is likely available, the Governor does not propose using funds from either the BSA or the School Reserve in the May Revision.

May Revision Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget after accounting for the May Revision proposals and solutions. We also describe the condition of the school and community college budget. As is the case in the previous section, all of the estimates and figures here are predicated on the administration’s revenue projections.

General Fund Budget

Figure 2 shows the General Fund condition under the May Revision. The state would end 2023‑24 with $3.8 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). The SFEU is the state’s operating reserve and essentially functions like an end‑of‑year balance. The State Constitution’s balanced budget provision prohibits the state from enacting a negative SFEU balance for the upcoming fiscal year, in this case, 2023‑24. While historically the state mostly has enacted SFEU balances between $1 billion and $4 billion, the Legislature can choose to set the balance at any level above zero.

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$40,057 |

$55,462 |

$24,118 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

232,537 |

205,129 |

209,054 |

|

Expenditures |

217,133 |

236,472 |

224,101 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$55,462 |

$24,118 |

$9,072 |

|

Encumbrances |

$5,272 |

$5,272 |

$5,272 |

|

SFEU Balance |

$50,190 |

$18,846 |

$3,800 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$21,708 |

$22,252 |

$22,252 |

|

SFEU |

50,190 |

18,846 |

3,800 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

450 |

|

Total Reserves |

$72,798 |

$41,998 |

$26,502 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Under May Revision, Reserves Would Total $26.5 Billion by End of 2023‑24. As mentioned earlier, the Governor’s May Revision does not propose using any constitutional reserves to address the budget problem. As a result, under the administration’s estimates and assumptions, general purpose reserves would total $26.5 billion by the end of 2023‑24. In addition, the state would have $10.7 billion in the School Reserve, available only for school and community college programs. In both cases, the state would have reached the constitutional maximum for the accounts.

Budget Condition Expected to Continue to Deteriorate. Under the administration’s estimates and assumptions, the budget condition would worsen in future years. Specifically, under these estimates, the state faces operating deficits of around $15 billion in each year of the outlook (2024‑25 through 2026‑27). Cumulatively, these deficits would compound such that the state would have a negative $41 billion balance in the SFEU by 2026‑27. As such, these operating deficits represent future budget problems the Legislature would need to address. The budget condition will look different under our revenue estimates, however. We will address the budget’s multiyear condition in greater detail in our forthcoming report, The 2023‑24 Budget: Multiyear Budget Outlook.

School and Community College Budget

Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee Down Over Budget Window. The State Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. The minimum guarantee is met with a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. Compared with the estimates included in the June 2022 budget plan, the administration revises its estimates of the minimum guarantee up $317 million in 2021‑22 and down $3.6 billion in 2022‑23. For 2023‑24, the administration estimates the minimum guarantee is $106.8 billion—$3.5 billion below the 2022‑23 level enacted last June. The net decrease over the period is primarily attributable to lower General Fund revenue estimates, somewhat offset by higher local property tax revenue.

Includes Additional Ongoing Spending, Makes Reductions to Previous One‑Time Augmentations. Despite the drop in the guarantee, the May Revision proposes to provide an 8.22 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment for existing programs. Compared with the June 2022 budget plan, it also includes a net increase of $1.1 billion in constitutionally required deposits into the School Reserve, as well as a few new ongoing and one‑time initiatives. To cover these increases and avoid spending more than the guarantee, the May Revision proposes $5.1 billion in reductions to several one‑time grants approved last year.

Comments

Administration Maintains Some Spending Augmentations Using Safety Net Reserve and Budget Borrowing. Although the administration proposes about $15 billion in spending‑related solutions in its budget proposal, the administration still maintains significant one‑time or temporary spending augmentations slated for 2023‑24. To support this spending, at least in part, the administration uses about $2.5 billion in special fund loans and reserve withdrawals. Using these funds now means the state will not have them to support core programs later in the likely event that budget problems persist. In order to minimize the likelihood of future reductions to core programs, the Legislature could reduce more one‑time spending instead of using these reserves and special fund loans.

May Revision Predicated on Optimistic Revenues. Across 2021‑22 to 2023‑24, our tax revenue estimates are $11 billion lower than the administration’s May Revision estimates. We discuss our revenue estimates in greater detail here: The 2023‑24 Budget: May Revenue Outlook. Based on our assessment, there is a roughly two‑thirds chance revenues will come in below May Revision estimates. As such, while we consider the May Revision revenues plausible, adopting them would present considerable downside risk.

Budget Problem Magnified by New Proposals. The May Revision includes $2.9 billion in new, discretionary spending proposals. These proposals add to the budget problem dollar for dollar, necessitating spending reductions and other budget solutions. Given the budget problem, we recommend the Legislature reject all new discretionary proposals without prejudice, unless they address an immediate safety or health issue. In most cases, doing so would not impact current services provided by the state.

Revenues Estimates Are Always Uncertain. The administration points out that there is elevated uncertainty in this year’s revenue outlook. Significant revenue uncertainty, however, is not unique to this year. Due to economic unknowns, policy changes, and other potential disruptions, revenues forecasts are always uncertain. This year, as always, we advise adopting the best possible revenue estimate based on all available economic and revenue data. We do not view revenue uncertainties as a cause for inaction or a reason to adopt optimistic revenue assumptions.

Adopting Administration’s Revenue Estimates Sets Up Difficult January. We advise the Legislature to adopt our revenue estimates, which are less likely to result in unanticipated shortfalls in the future. Adopting the administration’s revenue estimates, by contrast, would mean there is a two‑in‑three chance that the state’s shortfall will grow, necessitating more budget solutions in next year’s budget. For example, under our revenues, and after accounting for constitutional spending requirements, the budget problem for 2023‑24 is $6.2 billion larger than the administration’s estimates. This would add to the administration’s already planned deficit for 2024‑25 of $14 billion. Put another way, adopting the Governor’s plan sets the Legislature up for another double‑digit budget problem, involving even more difficult budget decisions, next year.

Spending Reductions for 2023‑24 Will Be More Challenging Next Year. The state currently has $11 billion in one‑time or temporary spending planned for 2023‑24—amounts that appeared affordable when they were enacted in previous years, but appear less so today. If budget problems persist, as is likely, pulling back more of this spending will be necessary, at least in part. Doing so now—in response to our lower revenue projections—would be better than waiting until next year for a few reasons. Once the new fiscal year begins, state departments will begin obligating and distributing these funds as planned.As such, midyear pullbacks would need to be based on what money has gone out the door instead of the state’s priorities. This approach could be particularly disruptive to program participants who would have planned on receiving the funds. Moreover, the administration will have an information advantage—it knows better what money has or has not been dispersed—making it more challenging for the Legislature to exert its preferences in response. While using some reserves at that time could be reasonable, the Legislature could still face difficult decisions to ensure the budget is on sound fiscal footing in future years.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Spending Solutions

Appendix 2: All Other Solutions

Appendix 3: New Discretionary Spending