July 13, 2023

Mental Health Services Act

Revenue Volatility and the Governor’s Proposal to Reduce Allowable County Reserves

Summary. In March, the Governor proposed a broad package of changes intended to “modernize” the state’s behavioral health system, combined with additional funding for behavioral health housing. This post—the first in a series of planned reports—analyzes a specific proposal to lower the cap on allowable county reserves of Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) revenues. Adequate reserves are particularly important for counties given extreme MHSA revenue volatility. In light of this volatility, allowable reserves under the Governor’s proposal would be inadequate during an economic recession. Further, we find that the current-law reserve caps are too low. Whether or not the Legislature chooses to revisit the MHSA reserves policy, we recommend that the Legislature use this opportunity to address MHSA revenue volatility head on. Many options exist. For example, swapping the MHSA tax for a portion of the overall personal income tax (PIT) would provide counties with a far more reliable revenue stream that would continue to exhibit healthy growth, while only marginally increasing revenue volatility at the state level. Under this option, revenues could continue to be deposited into the MHSA fund in order to be dedicated to MHSA purposes, and the swap could be designed to raise the same amount of revenue over the long term.

Background

Mental Health Services Act

MHSA Approved by Voters in 2004. In November 2004, California voters approved Proposition 63, also known as the MHSA. The MHSA made substantial new funding available to counties for community mental health services. In particular, the MHSA dedicates a share of funding to prevention and early intervention activities, as well as innovative programs, that at the time some had argued should be a greater focus of public community mental health services.

Funds Services With Tax on Income Over $1 Million. Proposition 63 levied a 1 percent tax surcharge on taxable income over $1 million. The revenues from the MHSA tax are deposited into the Mental Health Services Fund (MHSF). The tax is concentrated on a very small number of taxpayers. In 2020, about 109,000 tax filers contributed $2.8 billion in revenue to MHSA. These filers comprised about six-tenths of 1 percent of all PIT filers in 2020. Of Proposition 63 taxpayers, however, about 70 percent of the total tax liability in 2020 was concentrated among about 13,000 filers with taxable income of $5 million and over.

Nearly All Revenue Dedicated to County Programs. The vast majority of MHSA funding goes to counties. The MHSA establishes a variety of parameters for how MHSA funding may be spent, including the percent of funds which must—or sometimes may—be spent on specific kinds of activities. Seventy-six percent of MHSA funding for counties must be used on community services and supports (CSS). CSS is the primary MSHA funding category that supports direct service provision to adults with serious mental illness and children and youth with serious emotional disturbance. The CSS category has three service categories: full-service partnerships (FSP), outreach and engagement services, and general system development. At least 50 percent of CSS funding is directed by state rules towards FSPs, which provide mental health and wraparound services for individuals with the greatest mental health needs. The MHSA also allows counties to dedicate up to about 20 percent of the funding they receive under the CSS category to purposes that support their local mental health system, such as capital facility and technological needs, workforce development programs, and prudent reserves. Nineteen percent must be used on prevention and early intervention activities, which are aimed at preventing mental illnesses before they become severe. The remaining 5 percent must be spent on innovative programs.

County Programs Predominantly Serve Ongoing Needs. Some activities eligible for MHSA funding serve a one-time or temporary purpose. Examples of these activities include constructing capital facilities, improving technology, and building prudent reserves. In addition, certain activities—for example, some innovative programs—may be good candidates for pilot projects. These one-time or temporary activities, however, make up a small portion of overall county MHSA spending. The bulk of MHSA spending—for FSPs, other CSS, or prevention and early intervention activities—is intended to support community mental health services provided on an ongoing basis to the population eligible to receive them. Ideally, these ongoing services would be funded with a relatively stable revenue source that allows for consistent spending over time.

Up to 5 Percent of Revenue Available for State Purposes. The MHSA allows up to 5 percent of overall revenues to be used for state administration of MHSA. The 5 percent is often referred to as the “state cap.” Under current legislative practice, funding within the state cap that is not needed for direct MHSA administration is available for the Legislature to appropriate to various mental health programs.

MHSA and Revenue Volatility

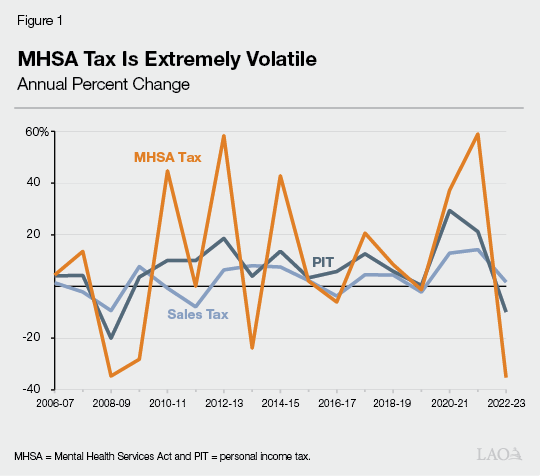

MHSA Tax Is an Extremely Volatile Revenue Source. Figure 1 compares the annual percent change in revenues from the MHSA tax, the state General Fund share of PIT, and the sales and use tax (SUT). (The figure shows MHSA revenue accrued by fiscal year—not as counties receive MHSA revenue via the monthly deposits and true ups discussed later.) Most of the taxable income earned by the vast majority of PIT filers is derived from wages and salaries. Wages and salaries are a relatively stable income category. By contrast, Proposition 63 filers derive a far greater share of their income from relatively volatile sources, including capital gains; partnership income; and dividends, interest, and rent. In particular, capital gains depend heavily on movements in financial markets. As such, tax revenue derived from capital gains is an extremely volatile and unpredictable source of income tax revenue. As shown in the figure, the year-over-year percentage change in MHSA revenue is in many years two to three times as large as the change in PIT. For example, in 2014-15, PIT revenue grew by 14 percent whereas MHSA revenue grew by over 43 percent. Also of note, in fiscal years in which PIT is growing slowly, MHSA revenue often declines year over year. For example, in 2016-17, PIT revenue grew by almost 6 percent while MHSA revenue declined by 6 percent.

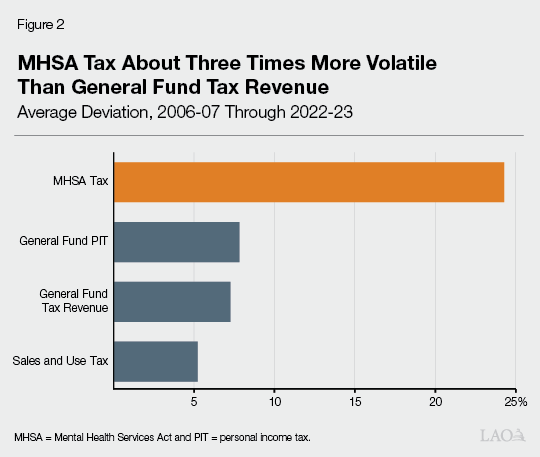

Measuring Revenue Volatility. In assessing the volatility of a data series, looking at the year-to-year changes in the data is important. When data show more variability in annual changes, they are said to be more volatile. One way to measure the variability in a data series is average deviation (AD). AD summarizes—for a given time period—how many percentage points the data in a series deviate from the average growth rate. Generally speaking, a revenue source with an AD of 10 percentage points over a given time period would be twice as volatile as a revenue source with an AD of 5 percentage points. See “Measuring Volatility” in our February 2017 report, Volatility of the Personal Income Tax Base, for a detailed description and hypothetical calculation of AD.

MHSA Tax Three Times More Volatile Than PIT. Figure 2 compares the AD of MHSA tax revenue to the ADs of the General Fund share of PIT, SUT, and all General Fund tax revenue. As shown in the figure, MHSA tax revenue is about three times more volatile than the General Fund share of PIT and General Fund tax revenues, and is nearly five times more volatile than SUT.

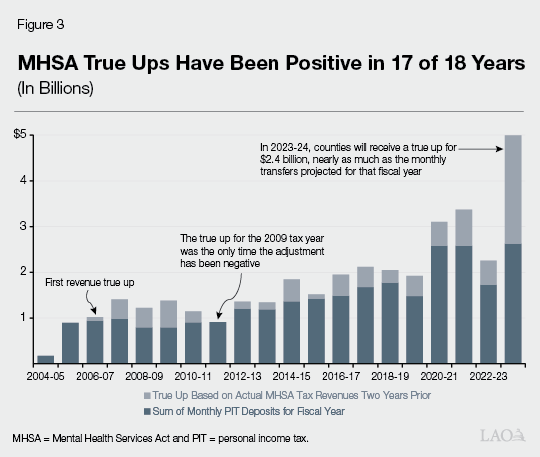

Proposition 63 Created True-Up Mechanism to Help Deal With Unpredictability of Revenues. Due to the volatility surrounding high-earners’ tax payments, Proposition 63 created a complex process by which a portion of PIT receipts are initially deposited into the MHSF monthly and later “trued up” based on actual MHSA tax revenue. True-up payment adjustments (which can be positive or negative) affect county revenues two years after the actual MHSA tax payments are made. Figure 3 shows revenues to the MHSF by fiscal year. The revenue in a single fiscal year is the sum of the monthly deposits plus the true up. On average, the true ups have been about 30 percent of the sum of initial monthly deposits for a fiscal year, but in 2023-24 the true up is projected to be 90 percent of the monthly deposits for that fiscal year. In other words, counties are essentially receiving an extra year of revenue via the true ups in 2023-24.

MHSA and Reserves

Budget Reserves Are the Key Tool Counties Have to Manage MHSA Revenue Volatility. Counties use reserves to set aside funds in good MHSA revenue years, allowing them to avoid having to make spending reductions in bad revenue years. Reserve deposits also take funding off the table when revenues surge, helping to avoid building the spending base to an unsustainable level. Given that the MHSA mostly funds ongoing mental health services, and that the need for these services is not sensitive to the economic cycle, reserves are an essential tool counties can use to achieve more consistent spending on MHSA services across years. That said, the need to hold significant reserves changes the timing of when revenues are allocated to programmatic purposes. Moreover, if allowable reserve levels are inadequate, counties may need to rely on other budgeting strategies to manage the volatility of the MHSA tax, which can raise questions regarding the efficient allocation of resources.

Proposition 63 Planning Process Requires Counties to Establish “Prudent Reserves.” Proposition 63 requires counties to prepare and submit three-year plans, and annual plan updates, that are reviewed by the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission. Generally, the plans detail how the counties will allocate unspent funds and estimated revenues on CSS, prevention and early intervention, innovation, and other MHSA programs. As a part of this planning process, Proposition 63 required counties to establish and maintain prudent reserves that allow for service provision during years in which revenues fall below recent averages grown for population and inflation. As described earlier, Proposition 63 allows up to 20 percent of the average amount of CSS funding that a county received over the previous five years to be used to support its local mental health system. Making deposits to maintain a prudent reserve to prevent funding for services from being reduced below the average of previous years is among the eligible uses of this “up to 20 percent” funding bucket. Proposition 63 also generally requires that any funds allocated to a county that are unspent within three years (five years for small counties) revert to the state to be redistributed among all of the counties.

Legislature Set Caps on Reserves in 2018. Chapter 328 of 2018 (SB 192, Beall), caps the allowable cumulative balance of county prudent reserves at 33 percent of the average CSS revenue the county received in the prior five fiscal years. (While Proposition 63 required prudent reserves and capped the annual amount of reserve deposits that could be made, it did not cap the cumulative balance that could be maintained in a reserve.) Legislative bill analyses from the time indicate that the author proposed the bill partly in response to a California State Auditor report that detailed large budget reserves at the county level over which the state was not providing effective oversight. The Auditor determined that the state should have reverted and redistributed $231 million held by counties beyond statutory time frames for expenditure, as required by Proposition 63. The Auditor also found that between $157 million and $274 million held in prudent reserve accounts were in excess of what would be needed to maintain spending in recent years adjusted for population and inflation—as was the original intent of Proposition 63 for prudent reserves.

State Regulations Establish Additional Parameters, Allow for Reserve Withdrawals. Under SB 192, counties initially established prudent reserves as of July 1, 2019 and are only required to recalculate their maximum allowable reserve levels once every five years, although state regulations allow counties to reassess their allowable reserves more frequently. State regulations allow counties to access their prudent reserves when the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) determines that MHSA revenues are below the average of the five previous fiscal years adjusted for changes in population and inflation. In addition, regulations require counties to transfer funds from their prudent reserves to their CSS accounts when they determine their projected allocation of CSS funds is insufficient to continue to serve the same number of individuals served by specified programs in the previous fiscal year.

Governor’s Proposal to Lower Allowable Reserve Caps

Governor Proposes Major Changes to Behavioral Health System and Additional Behavioral Health Housing. In March, the Governor provided the Legislature with a broad outline of a proposed package of changes intended to modernize the state’s behavioral health system, combined with additional funding for behavioral health housing. The proposal is currently moving through the Legislature in two companion bills—SB 326 (Eggman) and AB 531 (Irwin). Specifically, the Governor proposes a general obligation bond for the March 2024 ballot that would raise $4.7 billion. The proceeds from the bond sale would be used to build additional behavioral health beds in residential settings. In addition, the Governor proposes major changes to the MHSA that also would be submitted to the voters in March 2024. Among these changes, the Governor proposes to restructure the categories of funding, allow MHSA funds to be used for treatment of substance use disorders, increase county reporting on behavioral health spending, and lower allowable county prudent reserves. This post focuses on the Governor’s proposal to lower the cap on allowable reserves of MHSA revenues, which we discuss below.

Governor Proposes to Lower Allowable Prudent Reserve Caps. As has been communicated by the administration, the Governor seeks to reduce county prudent reserve caps from their current level of 33 percent of average CSS funding in the previous five years to 25 percent for small counties and 20 percent for large counties. This change would go into effect January 1, 2025. In addition, the Governor proposes to require the counties to recalculate their prudent reserves every three years rather than the five years in current law.

Changes to MHSA Categories Impact Available Funds for Reserve Deposits. The Governor proposes to change the categories of funding to require 35 percent of county funding to be dedicated to FSPs and 30 percent for housing interventions. Of the remaining funding, 30 percent would be used for behavioral health services and supports. Specifically, this category would include programs currently funded in the CSS and prevention and early intervention categories that would not fit within either the newly created FSP or housing categories, workforce, education and training, capital facilities, technological needs, innovative behavioral health pilots and projects, and prudent reserves.

Should Allowable Reserve Caps Be Lowered?

What Makes a Well-Performing MHSA Reserve Policy?

Reserve Caps Should Reflect Revenue Volatility... To aid in the Legislature’s assessment of the Governor’s proposal, we offer perspectives on what makes for a reasonable reserve policy for the MHSA. Ideally, a reserve policy accounts for the volatility of the funding source. There are several ways this can be done. For example, the Legislature could consider historical revenue experience. In the case of MHSA revenues that flow to counties, revenues declined on a year-over-year basis in 8 out of 15 fiscal years between 2007-08 and 2022-23. This experience shows that MHSA revenues decline during both economic expansions as well as recessions. For example, county MHSA revenue declined by 18 percent in 2015-16, a fiscal year that was solidly in the middle of an economic expansion. During a recession, MHSA revenue should be expected to decline sharply—for example, in 2010-11 and 2011-12 combined, revenues declined by 39 percent. While a reasonable reserve policy may not fully cover revenue declines that occur during severe recessions, the substantial volatility of MHSA revenue suggests that the reserve policy should be especially robust. While there is no one right target, we think a reasonable target for the current MHSA would be for allowable reserves to be almost certain to cover a 20 percent revenue decline and very likely to cover a 30 percent revenue decline. Under this target, counties would be confident that reserves could be sufficient to avoid major programmatic disruptions during good economic times. Furthermore, counties would have a very good chance of keeping robust reserves able to cover what may be a plausible revenue decline they might experience during a moderate recession. We note that there are reasonable arguments for setting a more or a less robust reserve policy.

…As Should Withdrawal and Deposit Rules. While a rainy-day fund designed for a relatively stable revenue stream might be reasonably focused on economic recessions, the historical experience with MHSA suggests that an effective withdrawal policy would allow counties to access reserves during economic expansions as well. Given the extent to which MHSA revenue can surge, and the associated challenge of making large upward adjustments to MHSA spending plans, an effective reserve policy would allow counties broad flexibility to deposit large portions of revenue surges into prudent reserves, to be used when revenues significantly decline in order to achieve more consistent spending over time.

Consider Willingness to Place Fiscal Risks on Counties. There is no one right level of reserves. In part, the extent of reserves desired can be informed by the level of risk that the Legislature is willing to take. In this case, however, counties will be the entities facing the consequences of an inadequate MHSA reserve policy. Thus, the Legislature would want to be mindful about placing excessive fiscal risks onto counties.

Insufficient Reserves May Result in Suboptimal Programmatic Outcomes. As described earlier, a small portion of MHSA funding can be used for certain one-time or temporary activities that support the local mental health system, including capital facilities and technological needs. While these activities are beneficial, the bulk of county mental health services funded by the MHSA—mainly FSPs and other CSS—are designed to meet an ongoing need for community mental health services across the population eligible to receive them. Given the volatility of MSHA tax revenues, state policy would ideally allow for county reserves to be sufficient such that counties can make ongoing commitments without the risk of major programmatic disruptions in response to large revenue declines. While we have not assessed past MHSA spending and outcomes, conceptually we think that an overreliance on temporary, rather than ongoing, commitments could lead to suboptimal programmatic outcomes. This underscores the need for a robust reserve policy that can withstand a reasonable range of potential future revenue declines.

Measuring the Potential Performance of a Reserve Cap Policy

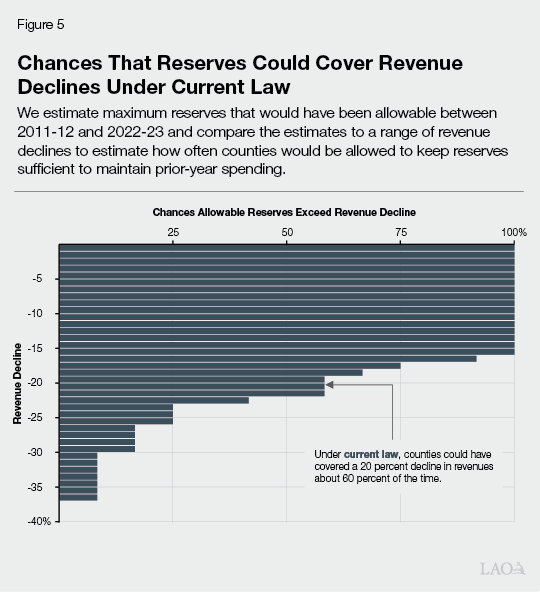

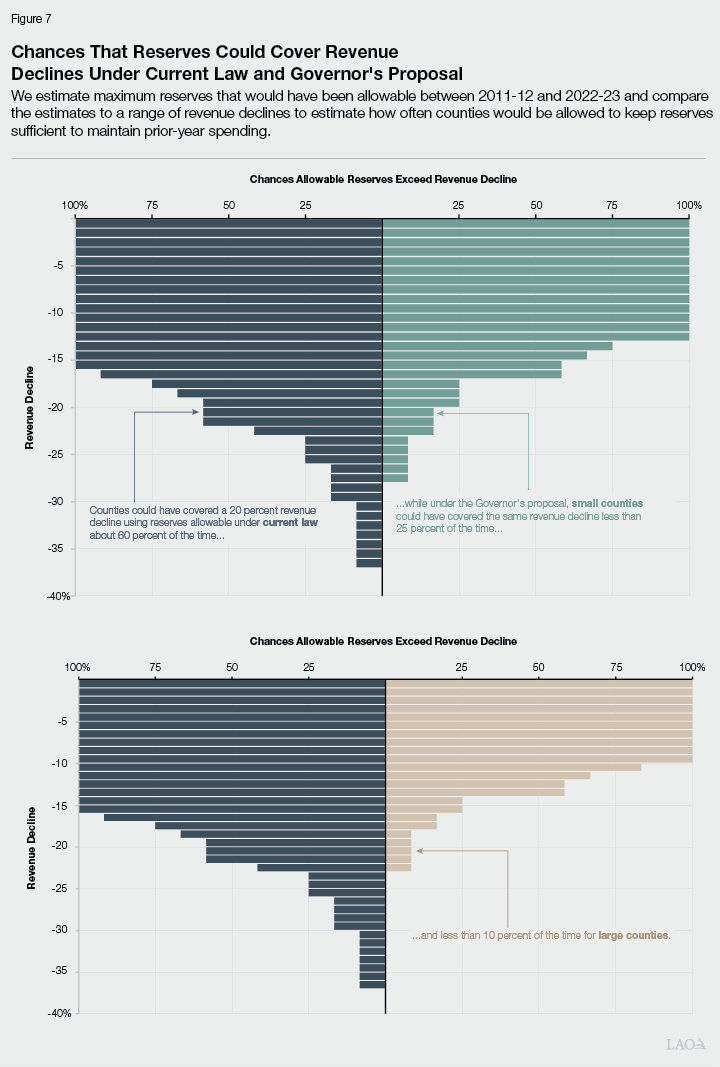

Based on Historical MHSA Revenue Performance, We Estimate the Chances Reserves Could Cover Revenue Declines. The current-law reserve caps have only been in place since 2019-20, providing little time to assess how well they have worked. To allow for a more robust analysis, we first estimate the level of reserves that would have been allowed under both the current-law caps and those proposed by the Governor had they been in place from 2011-12 through 2022-23. (As described earlier, the reserve caps are based on a five-year rolling average of CSS funding. We begin the analysis in 2011-12 because it is the first year for which there is five full fiscal years of revenue data needed to estimate the caps.) This approach results in 12 years of reserve cap data that we can compare to a range of revenue declines in order to gauge how often counties could be expected to fully cover future revenue declines with reserves. We compare allowable reserves under the three scenarios (current law, Governor’s proposal for small counties, and Governor’s proposal for large counties) in their ability to cover revenue declines of up to 40 percent (based on the largest historical MHSA revenue decline).

The Potential of the Current-Law Reserve Cap Policy

Prior to assessing the Governor’s proposal, we first assess the sufficiency of the current-law caps to establish a baseline against which the Governor’s proposal can be measured.

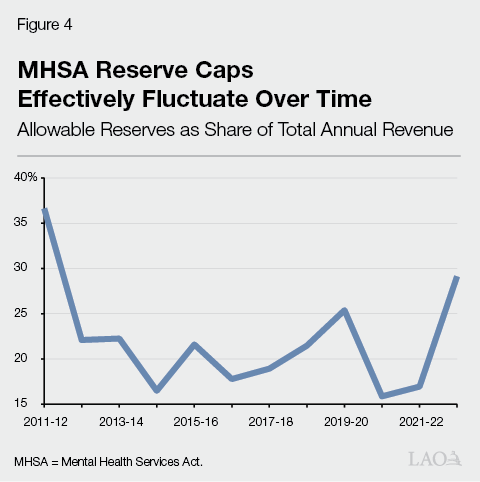

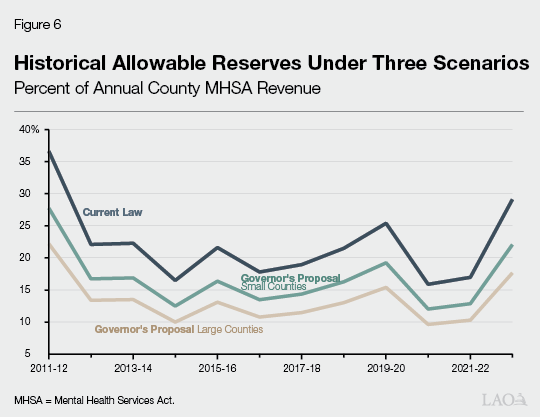

Reserve Caps Are Effectively Lower Than Expressed in State Law. As they are expressed in state statute, the current-law prudent reserve caps overstate the effective value of the reserves for two reasons. First, the current-law reserve caps are expressed as a percentage of a portion of MHSA revenue. Specifically, the caps are 33 percent of CSS funding, which itself is 76 percent of county MHSA revenues. This means that the caps are equal to 25 percent of total county MHSA revenues (the product of 33 percent and 76 percent). Second, the caps are based on an average of the previous five years of CSS funding. In general, when revenue is growing, the average amount of revenue in the previous five years will tend to be less than in the year for which the caps are being calculated. Figure 4 shows “effective” reserve caps—that is, reserves as a percentage of total annual county MHSA revenues. (The figure shows what the current-law reserve caps would have been had they been in place prior to 2019-20.) As shown in the figure, the effective reserve caps have fluctuated between 16 percent and 37 percent of total county MHSA revenue, averaging 22 percent of total county MHSA revenue across the period.

Current-Law Caps Arguably Constrain Counties From Acting Prudently When Revenues Spike. Because the reserve caps are based on a five-year rolling average, annual fluctuations in MHSA revenue do not result in a proportional change in the permissible level of reserves. As shown in Figure 4, this means that when revenues spike, as they did in 2014-15 and 2020-21, the reserve caps effectively decline as a share of total annual revenue. Revenue surges are the ideal time to be building reserves so as to prepare for future revenue drops and avoid building up base programs, and yet current law arguably constrains counties from acting prudently by making larger deposits at these times.

State Regulations May Be Too Restrictive in Allowing Withdrawals From Prudent Reserves. As described earlier, state regulations allow counties to access their prudent reserves when MHSA revenues are below the average of the five previous fiscal years adjusted for changes in population and inflation. We estimate that this withdrawal policy would have allowed counties to access prudent reserves three times since 2011-12: in 2011-12 (revenues declined 26 percent year over year), 2019-20 (revenues declined 9 percent), and 2022-23 (revenues declined 35 percent). The withdrawal policy, however, would not have allowed counties to access reserves in three other fiscal years in which revenues declined year over year: 2013-14 (revenues declined about 2 percent year over year), 2015-16 (revenues declined 18 percent), and 2018-19 (revenues declined 3 percent). Moreover, the policy relies on a DHCS determination, which may make it difficult for counties to predict when a withdrawal would be available. (We note that counties may have been able to access their prudent reserves in 2013-14, 2015-16, and 2018-19 to the extent that their projected allocation of CSS funds was insufficient to continue to serve the same number of individuals served by specified programs in the previous fiscal year. The extent to which counties could access reserves under this regulation is based on county determinations.)

Current-Law Reserve Caps Alone Likely Inadequate to Manage MHSA Revenue Volatility. Figure 5 shows the chances that reserves allowable under current law could cover revenue declines of up to 40 percent. Earlier, we suggested a target for allowable reserves to be almost certain to cover a 20 percent revenue decline and very likely to cover a 30 percent revenue decline. As Figure 5 shows, historical revenue performance suggests that counties could likely cover a 20 percent revenue decline, but would have a less than 10 percent chance of covering a 30 percent revenue decline. Given the low chances that counties could cover major revenue declines during an economic recession with currently allowable reserves, counties may have to rely significantly on temporary commitments and other budgeting strategies to compliment reserves allowable under current law.

Current Reserve Caps May Have Already Proved Too Low in Practice. Senate Bill 192 established the first prudent reserve caps for the 2019-20 fiscal year. In the first few years of experience, counties received a surge in revenue during 2020-21 (60 percent), followed by healthy growth in 2021-22 (8 percent), and a large decline in revenue in 2022-23 (35 percent). Based on our estimates, even under a best-case scenario in which all counties had proactively recalculated their reserve caps in 2022-23, the effective caps in that year (29 percent) would have been insufficient to cover the year-over-year decrease in revenue. If all counties had kept their 2019-20 caps in place, the effective reserve for 2022-23 (22 percent) would have been far below the year-over-year decrease in revenue. While 2022-23 was the largest single year-over-year decrease in MHSA revenue, the combined decrease over 2010-11 and 2011-12 combined was 39 percent; thus, we would describe the 2022-23 decrease as a large but not unprecedented decrease.

The Potential of the Governor’s Proposed Reserve Cap Requirement

Effective Reserves Proposed by Governor Are Lower Than Under Current Law. Figure 6 compares effective reserve caps that would have been allowed under current law from 2011-12 through 2022-23 with those proposed by the Governor. Across the period, allowable reserves under current law would have averaged about 22 percent of annual county MHSA revenue, compared with 17 percent and 13 percent for small and large counties, respectively, as proposed by the Governor.

Allowable Reserves Under Governor’s Proposal Almost Certainly Inadequate During Economic Recessions. Figure 7 compares the chances that allowable reserves could cover revenue declines of up to 40 percent under three scenarios: current law, the Governor’s proposal for small counties, and the Governor’s proposal for large counties. Again, applying the targets developed earlier, small counties could cover a 20 percent revenue decline less than 20 percent of the time, with that figure dropping to less than 10 percent of the time for large counties. Historical revenue performance suggests that neither small nor large counties could cover a revenue decline of 30 percent.

Governor’s Proposal May Reduce Future Prudent Reserve Deposits. As described earlier, counties can deposit up to about 20 percent of CSS funding annually into their prudent reserve accounts. Reserve deposits, however, currently compete against other activities that support local mental health systems, such as capital facility and technological needs and workforce development programs. Under the Governor’s proposal, prudent reserves would compete with additional activities, including certain programs currently funded in the CSS category and certain early intervention programs. The Governor’s proposed changes to the funding categories may make it harder for counties to prioritize prudent reserve deposits in the future.

LAO Finding: Case Not Made to Lower Reserve Cap Requirement. As described earlier, allowable county reserves under current law are likely inadequate to manage MHSA volatility. Lowering the reserve caps would further limit counties’ abilities to cover revenue declines. Specifically, the historical performance of MHSA revenues suggests that, under the Governor’s proposal, counties likely would not be able to cover revenue declines that could be expected to occur from time to time during economic expansions. Moreover, reserves allowable under the Governor’s proposal almost certainly would be inadequate during economic recessions. If the Legislature approves the Governor’s proposal, counties would have to rely more on temporary commitments and other budgeting strategies to cope with MHSA revenue volatility than they already do under current law. Moreover, the proposal may discourage ongoing spending commitments that may help counties provide more consistent and successful mental health services.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Recommend Addressing MHSA Revenue Volatility

MHSA Tax Is Not Suited to Supporting Ongoing Programs. Ongoing programs, like the mental health services provided under the MHSA, ideally are funded with fairly stable revenue sources that exhibit healthy growth over time. While growth in the MHSA tax has been strong, the tax is perhaps the most volatile source of revenue in the state tax system. Alternatives exist that could strike a better balance between revenue stability and growth. While a carefully designed and robust MHSA reserve policy may be able to encourage consistent spending, funding MHSA services with a stable revenue stream would be a more straightforward way of providing consistent and successful MHSA services.

Recommend Addressing MHSA Revenue Volatility Head On. As noted earlier, the author of SB 192 cited California State Auditor findings of excessive county reserves as part of the basis for the current caps on allowable reserves. The Auditor’s report and media accounts over the years suggested that counties have kept excessive reserve balances and are not responsive enough in spending their MHSA dollars in a timely manner. If the Legislature agrees that encouraging more responsive county MHSA spending is a priority, we think the most effective strategy may be to address the root cause of the problem—MHSA revenue volatility. Addressing MHSA revenue volatility would be especially vital if the Legislature adopts the Governor’s proposal to reduce allowable county reserves. Options—potentially requiring voter approval—include:

Change MHSA Tax Base. One way to address MHSA revenue volatility would be to change the MHSA tax base. Many options exist. For example, the Legislature could reduce the 1 percent tax rate and expand the taxable income subject to the tax, which could notably reduce MHSA revenue volatility while raising a similar amount of revenue. This approach, however, would increase the number of tax filers paying the MHSA tax.

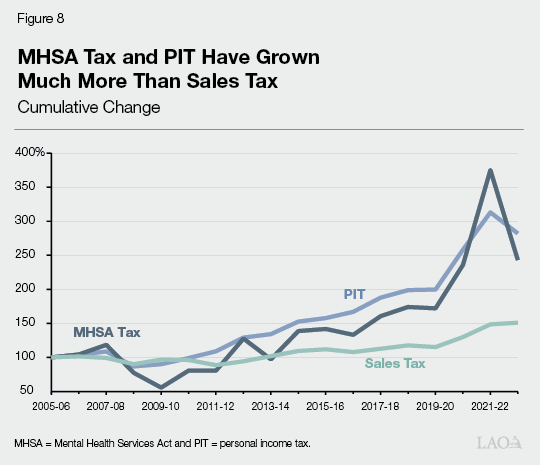

Swap MHSA Tax for Portion of SUT. Another way to fundamentally address MHSA revenue volatility would be to transfer the MHSA tax that is collected to the state General Fund and shift a dedicated portion of the General Fund tax base to fund the MHSA. One advantage to this approach would be that MHSA revenue volatility could be dramatically reduced without changing the taxes that any California taxpayer currently pays. If the Legislature wanted to shift an especially stable tax to counties, it could shift a portion of the General Fund share of the SUT. We note, however, that there are trade-offs between stability and long-term growth of a funding source. As shown in Figure 8, while the SUT would provide counties an especially stable fund source, it would come at the expense of long-term growth.

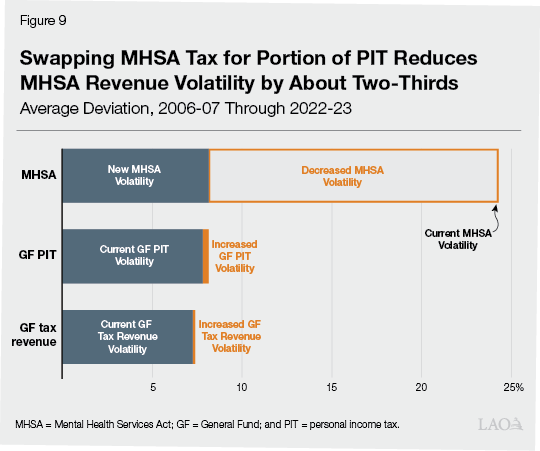

Swap MHSA Tax for Portion of PIT. Another possible approach that would strike a different balance between stability and growth would be to swap the MHSA tax for a portion of the overall PIT. We estimate that between 2005-06 and 2022-23, MHSA revenue has equaled 2.3 percent of overall PIT revenue. Swapping the MHSA tax for 2.3 percent of PIT would provide counties a much more stable funding source that would also experience healthy growth over time. Moreover, as shown in Figure 9, MHSA revenue volatility could be reduced by around two-thirds with only a marginal increase in overall General Fund tax revenue volatility. This approach would come with other benefits as well. There would no longer be a need for complex revenue true ups—instead, counties would receive a specified share (2.3 percent in this scenario) of PIT cash every month. This approach also would have the benefit of not changing the taxes that any California taxpayer pays.

Additional Reserve Policy Improvements for Legislative Consideration

In the course of our review of the Governor’s proposal, we have identified several potential other improvements to the county MHSA reserve policy that merit legislative consideration.

Match Allowable Reserves to Revenue Volatility. We think it is vital that MHSA prudent reserve caps reflect the volatility of the MHSA funding source. A reasonable level of reserve caps depends in part on whether the Legislature chooses to change the MHSA funding source to make it less volatile. Assuming no change to the MSHA tax, we think even the current-law reserve caps are too low. In order to meet our suggested reserve policy target, allowable reserves would have to be roughly 55 percent of CSS funding, or about two-thirds higher than the current-law level. The Governor’s proposal would therefore move the reserve caps in the wrong direction. If the Legislature chooses to address MHSA revenue volatility, it will want to choose a reserve cap policy that matches the volatility of the new revenue source. Substantially addressing MHSA revenue volatility could allow for reasonable reserve caps that are lower than in current law, perhaps as low as proposed by the Governor.

Grant Counties More Flexibility in Accessing Reserves… We think that the current rules governing MHSA prudent reserve withdrawals are arguably too constrained. For example, we estimate that the current rules would not have allowed counties to access reserves in 2015-16 when revenues declined 18 percent on a year-over-year basis. (In general, this was because MHSA revenues were still quite elevated compared with the preceding five fiscal years, which partially included tax revenues collected in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.) The Legislature could consider various flexibilities. For example, counties could be permitted to utilize their reserves in any fiscal year in which revenue is declining and in an amount up to the amount of the decline.

…And in Making Reserve Deposits. The current-law reserve policy is largely untested. In particular, there is limited experience of how the caps—and the rules governing deposits into the reserves—would perform during an economic downturn and in the years immediately following. Under current law, counties can deposit up to 20 percent of a five-year average of CSS funding into their reserves; however, prudent reserves compete with activities that support local mental health systems, such as capital facility and technological needs and workforce development programs. As described earlier, prudent reserves would compete against additional programs under the Governor’s proposal. While the degree to which expenditures on these other activities would squeeze out potential reserve deposits under the Governor’s proposal is unclear, we think imposing caps on both reserve deposits and cumulative reserve balances may be overly constraining. The Legislature may wish to consider removing the deposit caps completely or granting counties more flexibility to exceed deposit caps in years following significant year-over-year revenue declines or when revenues spike, as discussed below.

Allow Counties to Set Aside Revenue Spikes to Offset Future Declines. As described earlier, the current-law reserve caps as structured effectively decrease when revenues spike. This arguably constrains counties from acting prudently. There are several options that could allow for more flexibility in these spike years. For example, a large year-over-year increase in overall revenue or a true up exceeding a specified threshold could trigger flexibility for counties to set aside reserves in excess of their caps. The Legislature also could consider a mechanism that would automatically set aside spikes above a specified threshold. The Legislature could then consider providing counties a set period of time in which to right-size their reserves following a spike.

Conclusion

Governor’s Proposal Is a Missed Opportunity to Address Core Problem With MHSA Revenue. Ongoing programs, like the mental health services provided under the MHSA, ideally are funded with fairly stable revenue sources in order to provide consistent levels of service. Yet, the MHSA tax is perhaps the most volatile source of revenue in the state tax system. Absent other changes, lowering prudent reserve caps as the Governor proposes will only exacerbate county budgeting challenges and place excessive fiscal risk on counties. If the Legislature wishes to see more responsive county spending of MHSA funds, we recommend addressing MHSA revenue volatility head on. Many options exist. For example, swapping the MHSA tax for a portion of the overall PIT would allow counties to have far greater confidence in the reliability of their revenue stream while only marginally increasing revenue volatility at the state level. Under this approach, counties would also have long-term revenue growth comparable to what they have seen so far with the MHSA tax. Moreover, this approach would even allow for reasonable reserve caps that are lower than in current law and that do not force counties to take excessive fiscal risks.