January 13, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

Overview of the Governor’s Budget

- Introduction

- What Is the Budget Problem?

- How Does the Governor Propose Addressing the Budget Problem?

- Budget Condition

- Assessing the Governor’s Approach

- Crafting the Legislature’s Budget

- Appendices

Executive Summary

Why Do Budget Problem Estimates Differ? A budget problem is inherently a point‑in‑time estimate that reflects information available at the time of development, forecasts of future revenues and spending, and assumptions about the extent to which changes in costs are due to current policy (that is, whether or not they are “baseline changes”). When changes in costs do not occur automatically under current policy, we count them as budget solutions or augmentations. We take this approach in order to provide the Legislature visibility into the full scope of the administration’s choices.

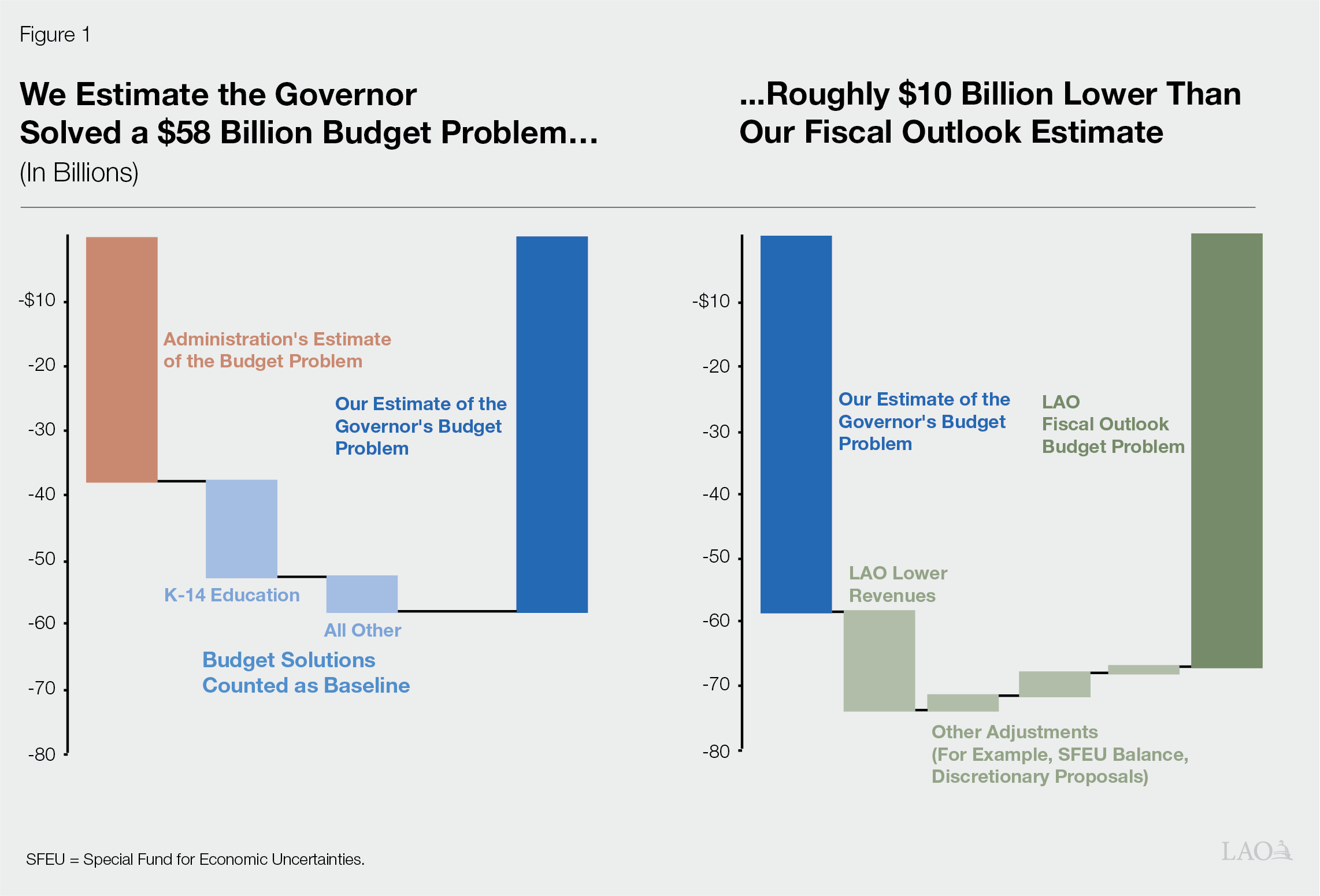

What Is Our Estimate of the Budget Problem Under the Governor’s Budget? We estimate the administration solved a budget problem of $58 billion. Our estimate of the Governor’s budget deficit is larger than the administration’s estimate ($38 billion) largely due to differences in what we consider to be baseline changes. The largest of these changes impacts schools and community colleges. Specifically, the administration defines a $15 billion reduction to school and community college spending—relative to the enacted level in 2023—as a baseline change.

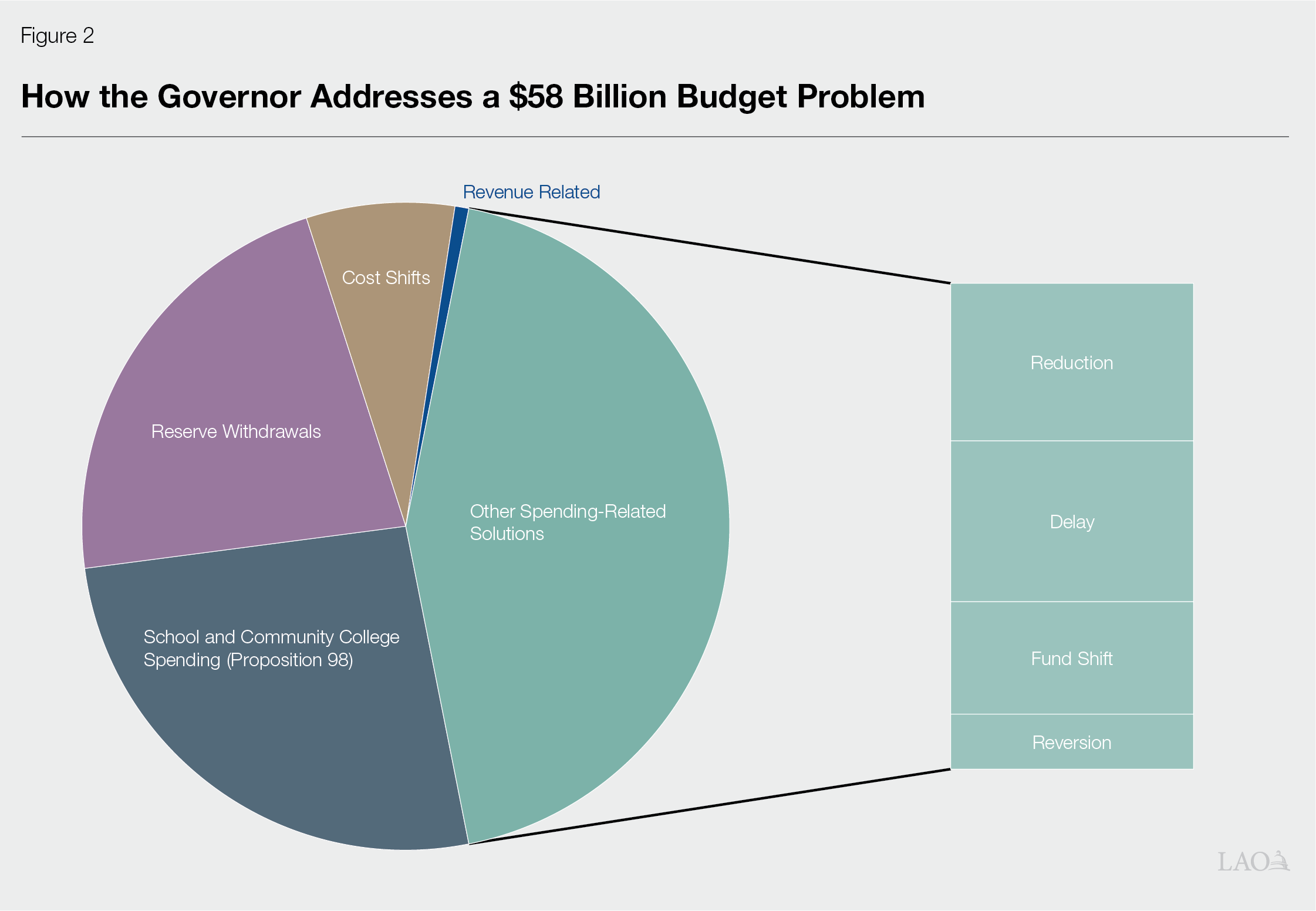

How Does the Governor Propose to Solve the Budget Problem? The Governor’s budget solutions focus on spending. Spending‑related solutions (including both school and community college spending and other spending) total $41 billion and represent nearly three‑quarters of the total solutions. In addition, the Governor’s budget includes $13 billion in reserve withdrawals, which represent nearly one‑quarter of the total; $4 billion in cost shifts; and about $400 million in revenue‑related solutions.

Assessing the Governor’s Approach. The Governor’s budget revenue projection is $15 billion higher than our Fiscal Outlook. This revenue estimate is plausible, but optimistic. On the spending side, there are strengths and weaknesses to the Governor’s approach. In particular, the Governor’s reserve withdrawal is reasonable, and we think focusing on spending‑related solutions is warranted. However, some significant spending‑related solutions pose challenges. The budget lacks a plan for implementing proposed reductions to schools and community colleges, and some other solutions are unlikely to yield the anticipated savings. Further, the state faces significant deficits in the coming years, likely necessitating difficult decisions in the future, such as reductions to core services and/or revenue increases.

Crafting the Legislature’s Budget. Overall, the Governor’s budget runs the risk of understating the degree of fiscal pressure facing the state in the future. The Legislature likely will face more difficult choices next year. To mitigate these challenges, we recommend the Legislature develop this year’s budget with a focus on future years. Specifically, we suggest the Legislature: (1) plan for lower revenues, (2) maintain a similar reserve withdrawal, (3) develop a plan for school and community college funding, (4) maximize reductions in one‑time spending, and (5) apply a higher bar for any discretionary proposals and contain ongoing service level.

Introduction

On January 10, 2024, Governor Newsom presented his proposed state budget to the California Legislature. In this report, we provide a brief summary of the Governor’s budget based on our initial review as of January 12. In the coming weeks, we will analyze the plan in more detail and release many additional issue‑specific budget analyses.

What Is the Budget Problem?

A budget problem—also called a deficit—arises when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. In the Governor’s budget, the administration estimated that the state faces a budget problem of $38 billion. In December, our office pegged the budget problem at $68 billion. The difference between these estimates is narrower than these topline numbers might suggest.

A budget problem is inherently a point‑in‑time estimate that reflects information available at the time of development, forecasts of future revenues and spending, and assumptions about the extent to which changes in costs are due to current policy (that is, whether or not they are “baseline changes”). When changes in costs do not occur automatically under current policy, we count them as budget solutions or augmentations. We take this approach in order to provide the Legislature visibility into the full scope of the administration’s choices. This section walks through the sources of our differences with the administration and how those differences impact the budget problem estimate.

We Estimate the Administration Solved a Larger Budget Problem—$58 Billion. While the Governor cited a budget problem of $38 billion, we estimate the administration solved a budget problem of $58 billion. Our estimate of the Governor’s budget deficit is larger than the administration’s largely due to differences in what we consider to be baseline changes. As the left side of Figure 1 shows, we estimate the administration counts about $21 billion in budget solutions as baseline changes. The largest of these changes impacts schools and community colleges. Specifically, the administration defines a $15 billion reduction to school and community college spending—relative to the enacted level in 2023—as a baseline change. As we explained in our report The 2024‑25 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, these adjustments would not be automatic under current law—they would require proactive choices by the Legislature—and therefore we count them as policy choices. Similarly, across the rest of the budget, we estimate the administration scores about $5 billion in other budget solutions as baseline changes. This includes, for example, $1.6 billion in spending delays for competitive transit grant funds, a change in the General Child Care budgeting methodology that results in nearly $900 million in savings over the budget window, and a change in the distribution of funds in the school facilities program that delays nearly $700 million in spending until after 2024‑25. If these actions were all counted as policy choices, rather than baseline changes, the resulting budget problem would be $58 billion.

We Estimate the Net Difference Between LAO and Administration Budget Problems Is About $10 Billion. The right side of Figure 1 shows the differences between our estimate of the administration’s budget problem versus our own December 2023 estimate. The key difference here is related to our offices’ respective revenue forecasts—the Governor’s are about $15 billion higher. Offsetting these higher revenues are some other changes. For example, the Governor sets aside $3.4 billion for unexpected costs and proposes over $2 billion in new discretionary proposals. Both of these choices make the budget problem larger and necessitate additional budget solutions by these amounts. (We will provide tables of all of the Governor’s proposed solutions and discretionary actions in forthcoming Appendices.)

How Does the Governor Propose Addressing the Budget Problem?

Figure 2 summarizes the budget solutions that this section describes in detail. The Governor’s budget solutions focus on spending. Spending‑related solutions (including both school and community college spending and other spending) total $41 billion and represent nearly three‑quarters of the total solutions. In addition, the Governor’s budget includes $13 billion in reserve withdrawals, which represent nearly one‑quarter of the total; $4 billion in cost shifts; and about $400 million in revenue‑related solutions.

Spending‑Related Solutions

The Governor’s budget includes $26 billion in spending‑related budget solutions (excluding schools and community colleges). These solutions can be categorized into four types: reductions, delays, fund shifts, and reversions. Nearly all of the Governor’s spending‑related solutions are one‑time and temporary, rather than ongoing. The remainder of this section describes each of these types in turn.

Reductions. Under our definition, a spending reduction occurs when the Governor proposes the state spend less money than what has been established under current law or policy. More colloquially, these are spending cuts. The Governor’s budget includes $8 billion in spending‑related reductions. The largest include: a nearly $800 million reduction to state departments’ operation budgets, proposed to be allocated through departments’ vacancy rates; about $500 million in savings to continue an existing two‑week delay in Medi‑Cal payments; a $500 million reduction to the school facilities aid program; and a $350 million reduction to legislative district projects.

Delays. We define a delay as an expenditure reduction that occurs in the budget window (2022‑23 through 2024‑25), but has an associated expenditure increase in a future year of the multiyear window (2025‑26 through 2027‑28). That is, the Governor proposes moving the spending to a future year. About $8 billion of the Governor’s spending‑related solutions are delays. As a result, proposed spending is higher by $5 billion in 2025‑26, nearly $2 billion in 2026‑27, and roughly $1 billion in 2027‑28. Given our and the administration’s forecasts of the budget condition in future years, the state likely cannot afford this spending. Although these delayed amounts would be subject to future budget conditions and legislative decisions, some delays create a relatively strong obligation or expectation on the state. For example, the Governor proposes reverting and delaying provision of about $2.7 billion in previously appropriated funding that already has been committed for specific state and local transportation projects. Because state departments and local agencies will already be well underway in planning, financing, and beginning to implement these projects, not providing this funding in future years would cause disruptions.

Fund Shifts. Fund shifts are budget solutions that use other fund sources—for example, special funds—to pay for a cost typically incurred by the General Fund. These shifts displace spending that these special funds otherwise would have supported. As a result, we consider these to be a type of spending‑related solution because they typically result in lower overall state spending, inclusive of all funds. We estimate the Governor’s budget includes $6 billion in fund shifts. This includes: using nearly $4 billion in revenue from the managed care organization tax to offset General Fund costs in Medi‑Cal and shifting $1.8 billion in costs for multiple programs from the General Fund to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Reversions. Costs for state programs sometimes come in lower than the amount that was appropriated. This often occurs, for example, when the state overestimates uptake in a new program or as a routine matter in programs where spending is uncertain due to factors like caseload. When actual state costs are below budgeted amounts, a reversion occurs after a period of time—typically, three years. The reversion returns the unspent funds to the General Fund. In this year’s budget, the Governor proposes accelerating some reversions that would have otherwise occurred in the future and proposes proactively reverting certain funds that otherwise are continuously appropriated (which has the effect of realizing savings from the unspent funds that would not otherwise occur). While not all of these amounts represent lower state spending over the long term, they do result in savings today at a cost in the future. As a result, we count them as spending‑related solutions. We estimate the proposed budget includes about $3 billion in reversions.

School and Community College Spending

$15 Billion in Lower Spending on Schools and Community Colleges. The California Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges (otherwise known as Proposition 98 [1988]). The state meets this requirement through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. Due to the large decline in General Fund revenues, the constitutionally required General Fund spending level is down $15.2 billion relative to the estimates in the June budget. The Governor proposes to reduce school and community college spending to this lower level (we describe the specific reductions in the next section).

Reserve Withdrawals

Budget Stabilization Account. Proposition 2 (2014) governs deposits into and withdrawals from the state’s general‑purpose constitutional reserve—the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). Under these rules, the state can make withdrawals from the constitutionally required balance of the BSA in a fiscal emergency, which occurs when estimated resources for the upcoming year are insufficient to cover the costs of the previous three enacted budgets, adjusted for inflation and population. Although the Governor has not officially declared a budget emergency for 2024‑25 (or any other year in the budget window), we agree that the conditions for a declaration exist. After a budget emergency is declared, the state can withdraw up to half of the constitutional balance of the BSA. (The Legislature also can withdraw the entire “discretionary” balance of the BSA at any time, which are amounts that were deposited into the fund on top of Proposition 2 requirements.) The Governor proposes withdrawing half of the BSA’s constitutional balance, $10.2 billion, and the entire discretionary balance, $1.8 billion.

Safety Net Reserve. The Governor also proposes withdrawing the entire balance of the Safety Net Reserve—$900 million. Withdrawing the entire balance of the Safety Net Reserve may not be consistent with legislative intent. The Safety Net Reserve was designed to help cover costs of increasing caseload in Medi‑Cal and the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program in the event of an economic downturn. Although caseloads under the Governor’s budget are higher than anticipated in June, economic conditions likely do not yet match what the Legislature envisioned when it created the reserve. Moreover, the administration proposes ongoing reductions to CalWORKs despite withdrawing these reserves. Withdrawing the entirety of this reserve may not be consistent with its original design.

Cost Shifts

The Governor’s budget includes about $4 billion in cost shifts. We define cost shifts as budget actions that achieve savings in the present, but result in a binding obligation or higher cost for the state in a future year. In that way, these actions can be similar to borrowing, but are often not explicitly structured as such. For example, major categories of cost shifts in the Governor’s budget include proposals to: defer one month of state employee payroll from June to July, which results in $1.6 billion in one‑time savings; redirect a $1.3 billion supplemental pension payment made under the requirements of Proposition 2 for actuarially required contributions to the California Public Employee Retirement System, and $1.2 billion in special fund loans.

Revenue‑Related Solutions

We estimate the Governor’s budget includes about $400 million in revenue‑related solutions. For example, the Governor proposes narrowing businesses’ ability to reduce their tax bill by counting previous losses against their current income. This would generate about $300 million in additional revenue in 2024‑25.

Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget after accounting for the Governor’s budget proposals and solutions. We also describe the condition of the school and community college budget.

General Fund Budget

Figure 3 shows the General Fund condition based on the Governor’s proposals and using the administration’s estimates and assumptions.

Figure 3

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$61,737 |

$42,078 |

$8,030 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

180,416 |

196,859 |

214,699 |

|

Expenditures |

200,075 |

230,908 |

208,718 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$42,078 |

$8,030 |

$14,010 |

|

Encumbrances |

10,569 |

10,569 |

10,569 |

|

SFEU balance |

31,509 |

‑2,539 |

3,441 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$21,708 |

$23,132 |

$11,106 |

|

SFEU |

31,509 |

‑2,539 |

3,441 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

— |

|

Total Reserves |

$54,117 |

$21,493 |

$14,547 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|||

Under Governor’s Budget, Reserves Would Total $14.5 Billion by End of 2024‑25. Under the Governor’s budget, general purpose reserves would total $14.5 billion by the end of 2024‑25. (In addition, the state would have $3.9 billion in the Proposition 98 Reserve, available only for school and community college programs.) The remaining balance of the BSA—$11 billion—would likely be available to address a budget problem next year in the very likely event that it occurs.

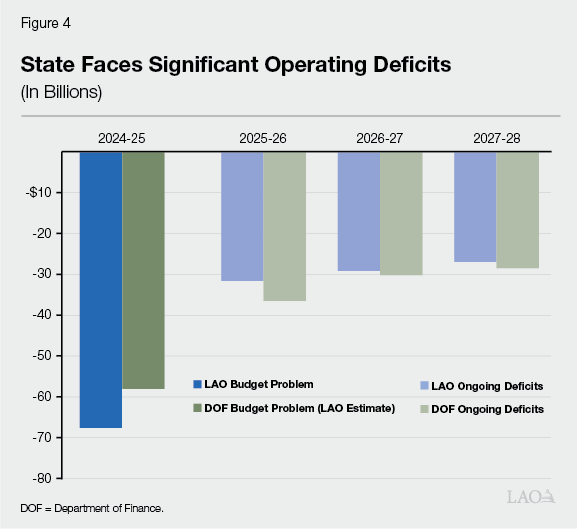

Administration Plans for Significant Future Budget Deficits. The Governor’s budget includes estimates of multiyear revenues and spending. Under the administration’s projections, the state faces operating deficits of $37 billion in 2025‑26, $30 billion in 2026‑27, and $28 billion in 2027‑28. (As shown in Figure 4, these deficits are very similar to our December projections of the budget’s position—although our estimates were based on current law and policy, not the Governor’s budget proposals.) Although these future deficits are smaller than the current one, they are still quite significant. Moreover, the state is likely to face these deficits with fewer options—such as one‑time spending reductions and reserves. As such, future deficits are likely to require more difficult decisions, like ongoing spending cuts and revenue increases.

School and Community College Budget

Funding for Schools and Community Colleges Down $14.3 Billion Over Budget Window. Compared with the estimates included in the June 2023 budget plan, the administration estimates the constitutional minimum funding level for schools and community colleges is down $14.3 billion over the 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 period. This downward revision consists of a $15.2 billion reduction in required General Fund spending, partially offset by a $903 million increase in local property tax revenue. Most of the reduction—$9.1 billion—is attributable to 2022‑23, with the remainder divided about evenly between 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The Governor proposes to reduce funding to the lower constitutional level through a combination of spending reductions and discretionary withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve. These reductions also free up funding for a few smaller augmentations.

Assumes $8 Billion in Lower Spending in 2022‑23. The budget proposes to reduce General Fund spending on school and community college programs in 2022‑23 by $8 billion. The budget does not specify how the state will implement this reduction, but indicates the state will make the reduction in a way that avoids impacting school and community college budgets. We also understand that as part of this action, the state would make supplemental payments totaling $8 billion over a five‑year period (from 2025‑26 through 2029‑30). (Separate from this proposal, the budget scores $1.1 billion in lower baseline spending in 2022‑23.)

Proposes Discretionary Withdrawal From Proposition 98 Reserve. The Proposition 98 Reserve is a statewide reserve account for school and community college funding. The Governor proposes to make a discretionary withdrawal of $5.7 billion from this account to help cover costs for existing school and community college programs in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. After accounting for the discretionary withdrawal and a few other automatic adjustments, the remaining balance in the reserve would be $3.9 billion.

Funds Augmentations in a Few Areas. The most notable ongoing augmentation is a 0.76 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for existing school and community college programs. The most notable one‑time proposal is $500 million for a second round of grants funding zero‑emission school buses. The budget also proposes smaller increases related to the educator workforce, education technology, and community college nursing programs.

Assessing the Governor’s Approach

Revenues Optimistic but Plausible. California entered a revenue and economic downturn last fiscal year. State tax revenues fell 20 percent. The number of unemployed workers in California increased by 200,000. A key question for this budget is: to what extent and for how long will this downturn persist? The Governor’s budget assumes a quick return to growth, projecting an 8 percent increase in tax revenues in the current fiscal year. While possible, we think this assumption is optimistic. Halfway through the current year, we are yet to see clear signs of such a rebound. Income tax withholding is up only 2 percent. Sales tax collections are down slightly. In the relatively important collections month of December, corporation tax collections posted double digit declines. Unemployment continues to tick up consistently each month. One potential reason for optimism is the rebound in stock prices that occurred over the last year, especially in the spring of 2023. Stock market rallies, however, can reverse as quickly as they start. Further, the relationship between stock price gains and state revenues is complex. Any two similar stock market rallies can have significantly different impacts on state revenues.

Reserve Withdrawals Generally Reasonable. The Governor proposes withdrawing roughly half of the BSA and the entire Safety Net Reserve to help solve the budget problem. While the administration likely could withdraw the entire balance of the BSA under the rules of Proposition 2 (for example, if the Governor declared a budget emergency for multiple years in the budget window), maintaining a sizeable balance in the BSA is prudent given the continued budget problems likely for future years.

Budget Lacks Plan for Implementing Proposed Reductions in School and Community College Spending. The largest source of savings within the Governor’s school and community college spending package is a proposed reduction of $8 billion in 2022‑23 funding. The administration, however, has not explained how its proposal could achieve $8 billion in savings, given the administration also indicates the proposal would not impact school and community college budgets. The Legislature will need significantly more information before it can assess the proposal—including its potential effects on the state budget after 2024‑25. The Legislature also may want to consider alternative solutions, such as making additional withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve, funding fewer augmentations, or making targeted reductions to existing programs.

Governor’s Spending‑Related Solutions Warranted, but Some Solutions Could Pose Challenges. The administration proposes spending‑related solutions (excluding school and community college spending) of $26 billion. This is a good start to solving the budget problem as these reductions largely do not impact the state’s ongoing core service level. There are some solutions, however, that may not yield the savings required to balance the budget. For example, across‑the‑board reductions—like the proposal to allocate general funding cuts to departments based on their vacancy rates—historically have not generated the initially assumed savings. In addition, as discussed earlier, some proposed solutions increase future budget pressure and shift fiscal risk to other entities. In addition to the transportation example provided earlier, the administration suggests the University of California and California State University could use delayed payments as collateral against borrowing. Not only would this proposal increase the pressure on the state to provide these payments next year—despite continued deficits—but it also would shift fiscal risk to these entities in the event the state does not ultimately make these payments.

Despite Spending‑Related Solutions, Governor’s Budget Likely Unsustainable in Future Years. The state faces significant operating deficits in the coming years, which are the result of lower revenue estimates, as well as increased cost pressures. These deficits are somewhat compounded by the Governor’s budget proposals to delay spending to future years and add billions in new discretionary proposals. State revenues in the out‑years would need to exceed the administration’s forecast by roughly $50 billion per year in order to sustain the spending proposed by the Governor’s budget. While our multiyear revenue forecast is somewhat above the administration, it is well below amount needed to close the deficits. Thus, while it may be reasonable to expect some upside to the administration’s multiyear revenues, it is unlikely this upside will resolve the out year deficits.

Crafting the Legislature’s Budget

Overall, the Governor’s budget runs the risk of understating the degree of fiscal pressure facing the state in the future. The Legislature likely will face more difficult choices next year. To mitigate these challenges, we recommend the Legislature develop this year’s budget with a focus on future years. In particular, most of the recommendations we make here would mitigate some of the need for even more difficult decisions in the future, such as reductions to core services and/or revenue increases.

Plan for Lower Revenues. By May, we will be much closer to resolving the question of how much (if at all) revenues will rebound in the current fiscal year. While many outcomes are possible, our assessment of the current evidence suggests the resolution of this question likely will result in the administration revising down their revenue estimates in May. Should this occur, it would necessitate additional budget solutions. We advise the Legislature to begin to consider now what those solutions could be.

Maintain Similar Reserve Withdrawal. We advise the Legislature to use no more in reserves than proposed by the Governor—currently about half of general‑purpose reserves. Given the state is likely to continue to face significant budget problems in the coming years, depleting reserves now would make reductions to ongoing programs and/or ongoing revenue increases more likely.

Develop Plan for School and Community College Funding. Given the lack of clarity in the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature may want to develop its own plan for addressing school and community college funding. As we describe in our Fiscal Outlook, the Legislature could use the existing balance in the Proposition 98 Reserve to help cover spending above the constitutional minimum in 2022‑23. This approach would allow the state to reduce spending in 2022‑23 with no immediate effect on schools and community colleges.

Maximize One‑Time Spending Reductions. The Governor’s budget includes $26 billion in spending‑related solutions (excluding school and community college solutions). While the Governor’s budget likely reflects pulling back most recently approved one‑time and temporary spending, we are still assessing whether any additional such appropriations remain. To the extent they do, we recommend the Legislature assess whether additional pull backs could be achieved, including in the current year. Maximizing one‑time spending reductions allows the Legislature to minimize the use of other budget tools—like reserves—that likely will be needed in future years. To ensure these one‑time savings can be realized, the Legislature may wish to consider early action on current‑year appropriations.

Apply High Bar for Any Discretionary Proposals and Contain Ongoing Service Level. The Governor’s budget includes roughly $2 billion in discretionary proposals for 2024‑25. To balance the budget, these discretionary proposals require additional reductions to already approved expenditures. Consequently, we recommend the Legislature set a very high threshold for approving these new proposals. Specifically, the Legislature would need to view these new proposals as preferable to already approved spending. We also recommend the Legislature avoid growing the ongoing service level by assessing whether to continue approved, but not yet implemented, programs.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Spending Solutions

Appendix 2: All Other Solutions

Appendix 3: New Discretionary Spending