LAO Contact

February 21, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

California Community Colleges

Summary

Brief Covers the California Community Colleges (CCC) Budget. This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals relating to CCC enrollment, apportionments, and nursing education. In addition, the brief provides a number of recommendations and options to help the Legislature address the large gap between current CCC spending and available Proposition 98 funding.

Governor’s Budget Plan for CCC Has Notable Drawbacks. In responding to the drop in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for 2022‑23, the Governor proposes a budget maneuver that effectively borrows from the future non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget—setting problematic fiscal precedent and worsening the state’s out‑year deficits. In addition, the Governor’s budget likely overestimates the amount of funding available to the colleges in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The Governor’s budget also proposes to increase ongoing spending in 2024‑25 by providing a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) to certain CCC programs, despite not being able to afford even existing CCC spending commitments. Furthermore, the Governor misses many opportunities to pull back funds remaining from prior budgets to achieve one‑time budget solutions.

Recommend Rejecting Budget Maneuver, Using Proposition 98 Reserves Instead. Given the significant drawbacks to the Governor’s CCC budget plan, we recommend the Legislature take a different approach. For 2022‑23, instead of adopting the Governor’s problematic budget maneuver, we recommend the Legislature use Proposition 98 reserves to address the funding shortfall. This alternative is sound from a legal perspective, avoids setting a troubling fiscal precedent, does not worsen future budget deficits, and is in line with the underlying rationale for having a Proposition 98 Reserve account.

Recommend Reverting Funds Remaining From Recent CCC Initiatives. Based on our February 2024 revenue estimates, an $800 million gap exists in 2023‑24 between CCC spending and available Proposition 98 funding. We recommend the Legislature address the bulk of this gap by reverting certain unallocated and unspent CCC funds. We identify many unused funds from recent CCC initiatives that could be pulled back on a one‑time basis. In many cases, the funds we identify are available because of insufficient take‑up rate by colleges or students for newly created programs. The Legislature could consider our list a starting point, adding items, if needed.

Recommend Identifying Ongoing Solutions Outside of Colleges’ Core Programs. Beyond one‑time solutions, the Legislature might need to look for ongoing solutions to balance the CCC budget. Based on our February 2024 revenue estimates, approximately $700 million in ongoing CCC solutions would be required to align ongoing spending with the minimum guarantee in 2024‑25. The $700 million assumes that the Legislature does not fund the Governor’s CCC COLA proposals. More or less savings might be needed depending on budget developments from now through June 2025. In deliberating over the coming months on how to achieve savings, we recommend the Legislature attempt to preserve funding in certain core areas, including CCC’s core instructional mission and aid for financially needy students. Outside of these core areas, we identify several ways the Legislature could achieve ongoing savings, including by reducing state support for certain athletic activities, enrichment activities, and aid for non‑financially needy students. As with our list of one‑time solutions, the Legislature could use our list of ongoing solutions as a starting point, potentially adding items, as needed.

Introduction

CCC Has Broad Mission. The CCC system is one of California’s three public higher education segments. The system consists of 115 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts located throughout the state, plus one statewide online community college administered by the Board of Governors. The colleges offer a breadth of academic programs, including lower‑division transferable coursework, career technical education, precollegiate basic skills instruction, and citizenship classes. The state also allows community colleges to offer baccalaureate degrees in certain occupational fields as long as they do not duplicate the programs offered by the University of California (UC) or the California State University (CSU). In addition to their core academic programs, colleges are authorized to offer state‑supported instruction that is primarily recreational in nature (such as golf and yoga classes).

Brief Focuses on CCC Budget. This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals for CCC. We begin by describing the Governor’s overall budget plan for CCC and providing our high‑level assessment of that plan. The next four sections of the brief focus on CCC enrollment, apportionments, a loophole related to summer enrollment, and nursing education, respectively. Within those sections, we identify a few opportunities for the Legislature to achieve budget savings. The last section covers other opportunities the Legislature has to achieve one‑time and ongoing budget savings.

Overview

In this section, we first cover major Proposition 98 proposals impacting community colleges. We then assess the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 plan for the colleges and provide associated high‑level recommendations. In the last section, we cover certain non‑Proposition 98 proposals for the colleges.

Proposition 98 Proposals

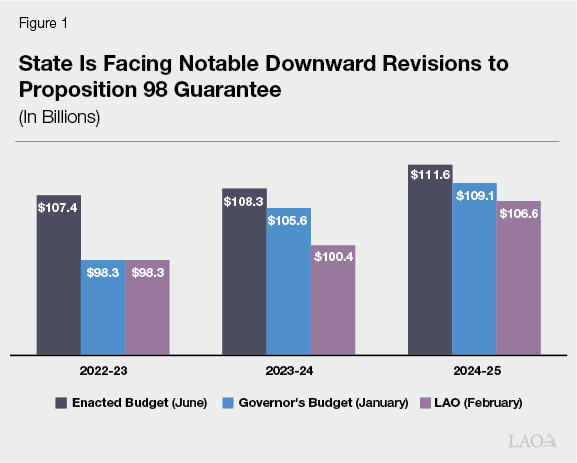

Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee Is Revised Downward Over Budget Window. Proposition 98 (1988) established a constitutional funding formula that sets a minimum annual funding level for schools and community colleges. Commonly known as the “minimum guarantee,” this funding requirement is met through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue. Since the 2023‑24 budget was enacted, the administration has revised its estimates of state General Fund revenues down substantially. These downward revenue revisions in turn lead to significant downward revisions in the administration’s estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25. As Figure 1 shows, the minimum guarantee is down even further in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 under our February 2024 estimates. We discuss these estimates in more detail in The 2024‑25 Budget: Proposition 98 and K‑12 Education Analysis.

State Faces Unusually Large Drop in 2022‑23 Proposition 98 Guarantee. Of the downward revisions, $9.1 billion is attributable to 2022‑23. This is the largest reduction to the guarantee in a prior year since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. Previous downward revisions to the prior‑year guarantee have been no more than a few hundreds of millions of dollars. The administration attributes the unusually large adjustment primarily to the late tax filing deadline for 2022 returns (November rather than April 2023) and the lack of reliable revenue data prior to budget enactment in June 2023.

Governor Proposes Large Budget Maneuver Relating to Reduction in 2022‑23 Guarantee. The Governor proposes to realign Proposition 98 spending with the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee in 2022‑23. The main way the Governor addresses the reduction in the guarantee is by proposing to reclassify $8 billion in Proposition 98 General Fund payments already made to schools and community colleges. Of the $8 billion, $910 million would be attributed to community colleges. The $8 billion would be reclassified as non‑Proposition 98 General Fund payments, removed from the state’s books in 2022‑23, and recognized back on the state’s books in even increments spread across 2025‑26 through 2029‑30. This maneuver would not reduce any previous funding provided to colleges or attempt to recoup any of this funding in subsequent years—districts would retain the associated cash they originally received. Rather than colleges being affected, the impact of the maneuver would occur entirely on the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget beginning in 2025‑26. In effect, the state would be borrowing from future non‑Proposition 98 funds to pay for 2022‑23 school and college spending. Unlike a traditional loan, however, the state would not score this mechanism as borrowing, make payments to an external creditor, or accrue any interest.

Governor Proposes Using Proposition 98 Reserves to Address Reduction in 2023‑24 Guarantee. Under the Governor’s budget, the minimum guarantee in 2023‑24 is revised downward by $2.7 billion. The Governor’s budget also accounts for higher baseline costs in several programs (mostly involving K‑12 schools). The main way the Governor proposes to address the lower guarantee and higher costs is by making a $3 billion discretionary withdrawal from the Proposition 98 Reserve. Of this amount, the Governor proposes using $236 million to cover ongoing community college apportionment costs. (We discuss apportionment costs in more detail in the “Apportionments” section of this brief.)

Governor Proposes Increasing CCC Spending in 2024‑25. Despite not having sufficient Proposition 98 funds to cover existing Proposition 98 program costs, the Governor’s budget contains some Proposition 98 program augmentations in 2024‑25. As Figure 2 shows, the largest CCC proposal is to provide apportionments with $69 million to cover a 0.76 percent COLA—the same COLA rate proposed for the K‑12 Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The Governor also proposes providing a 0.76 percent COLA to seven CCC categorical programs at a total cost of $9.3 million. The Governor proposes $30 million for 0.5 percent systemwide CCC enrollment growth In addition, the Governor’s budget contains $60 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund to expand CCC nursing education. (Last year, the state adopted a five‑year funding plan totaling $300 million to expand CCC nursing education, with the programmatic details of the initiative to be subject to future legislation.)

Figure 2

Governor’s Budget Proposes Some

Proposition 98 Spending Increases for CCC

2024‑25 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (0.76 percent) |

$69 |

|

Student Success Completion Grant (caseload adjustment) |

50 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

30 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (0.76 percent)a |

9 |

|

Subtotal |

($158) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Nursing education |

$60 |

|

Subtotal |

($60) |

|

Total Spending Increases |

$218 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and the mandates block grant. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

Governor Accommodates Higher Proposed Spending in 2024‑25 Using More Reserves. To cover his new proposed CCC spending in 2024‑25, the Governor proposes to make another discretionary withdrawal from the Proposition 98 Reserve. For schools and colleges combined, the Governor proposes to withdraw $2.6 billion. Of this amount, $486 million would be used for ongoing community college apportionment costs. Under the Governor’s plan, $3.9 billion in Proposition 98 reserves would remain available entering 2025‑26.

Assessment

Proposed Budget Maneuver Worsens State’s Out‑Year Deficits. We have major concerns with the Governor’s proposed budget maneuver for addressing the drop in the 2022‑23 guarantee. As we discuss in The 2024‑25 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state is projected to have multiyear budget deficits of roughly $30 billion annually. The Governor’s proposed maneuver contributes to these projected budget deficits over the outlook period and beyond (through 2029‑30). Carrying $8 billion in effectively greater internal debt would make balancing the state budget more difficult in the coming years. Moreover, the impact would be felt fully on the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget—potentially at the expense of health care programs, social services, and other state programs beyond education. The maneuver sets problematic fiscal precedent by borrowing from the future to pay for past operating costs. We describe these and other concerns in more detail in The 2024‑25 Budget: The Governor’s Proposition 98 Funding Maneuver.

Proposed CCC Operating Shortfall Worsens CCC Budget Outlook. Whereas the Governor’s proposed funding maneuver makes balancing the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget more difficult beginning in 2025‑26, his proposed Proposition 98 operating shortfalls make balancing the Proposition 98 side of the budget more difficult too. Under the Governor’s plan, community colleges would enter 2025‑26 with a $486 million apportionment shortfall. The Governor’s plan also leaves schools with a nearly $2.2 billion LCFF shortfall entering 2025‑26. These combined shortfalls mean the first $2.7 billion of any new Proposition 98 funding in 2025‑26 would need to go first to backfilling funding gaps in existing programs. Entering 2025‑26 with existing operating shortfalls means both existing programs are at greater risk of cuts and any new priorities are less likely to be addressed.

Governor’s Plan Misses Opportunities to Achieve CCC Savings. The Governor’s plan relies solely on his proposed budget maneuver and drawing down Proposition 98 Reserves. Other than caseload and technical adjustments, the Governor’s plan includes no components aimed at lowering CCC spending, despite the state’s revised budget outlook. In taking this approach, the Governor misses opportunities to achieve savings over the budget window. Moreover, the savings opportunities that could be achieved now (like reverting unallocated funds from prior‑year initiatives) would have little negative impact on districts. By missing these opportunities now, the Governor’s plan makes realigning CCC spending with available Proposition 98 funding even more difficult moving forward.

Recommendations

Use Proposition 98 Reserves in Place of Funding Maneuver to Address 2022‑23 Drop in Guarantee. Under the Governor’s plan, the state would be using Proposition 98 reserves to increase CCC spending amid budget deficits. We recommend the Legislature take a more prudent approach and use the reserves instead to address the large decline in the 2022‑23 minimum guarantee. We think reserves provide the greatest benefit for the state budget—and for colleges—when the state is facing a large, unexpected shortfall and would need to adopt disruptive alternatives if it did not withdraw reserves. The significant drop in the prior‑year guarantee meets these conditions in 2022‑23. In contrast to the Governor’s proposed maneuver, using reserves to address the 2022‑23 shortfall would work within an existing legal framework, avoid setting a problematic fiscal precedent, and not worsen future state budget deficits. It also would be consistent with the state’s original rationale for creating the Proposition 98 Reserve account.

Identify More CCC Budget Solutions to Address 2023‑24 Drop in Guarantee. Based on our February 2024 estimates of the 2023‑24 minimum guarantee, the Legislature is facing an approximately $800 million gap that year between available Proposition 98 CCC funding and existing CCC spending. If the Legislature used Proposition 98 reserves to address the 2022‑23 situation, it would have approximately $175 million in Proposition 98 reserves remaining to support CCC program spending in 2023‑24. Although the estimated CCC funding gap in 2023‑24 is still subject to considerable uncertainty, we recommend the Legislature begin identifying additional potential Proposition 98 budget solutions. Toward this end, we recommend the Legislature revisit recent CCC initiatives to determine if any associated funding remains unallocated or unspent. As discussed in the “Budget Solutions” section of this brief, we estimate the Legislature could achieve hundreds of millions of dollars in additional Proposition 98 budget solutions by identifying still available funds from recent CCC initiatives. Pulling back these funds could yield potentially enough savings to address the entire CCC budget gap in 2023‑24.

Hold Core CCC Spending Flat in 2024‑25. As a starting point in building the CCC budget for 2024‑25, we recommend not increasing ongoing CCC spending. To this end, we recommend not providing a COLA to apportionments (or any CCC program). Typically, when facing multiyear deficits, the state aims to contain, not increase, spending. Though we recommend not providing a COLA to CCC apportionments, we recommend the Legislature place a high initial priority on maintaining funding for the colleges’ core instructional costs. Districts cover their core instructional costs by relying on certain components of their apportionment funding. Typically, colleges have more difficulty responding to reductions in this apportionment funding compared to their other program funding.

Begin Considering Ways to Achieve Ongoing General Fund Savings. After all Proposition 98 reserves have been spent and all opportunities for pulling back unallocated or unearned funds have been exhausted, the state still might face a notable Proposition 98 CCC budget problem. Under our February estimates, hundreds of millions of dollars in ongoing Proposition 98 CCC budget solutions would be needed. In this situation, we recommend the Legislature attempt to preserve funding for key priorities such as CCC’s core instructional mission, student support services, and aid for financially needy students. Areas the Legislature might consider finding savings is by eliminating state support for athletics and classes that are primarily enrichment in nature, as well as eliminating fee waivers for non‑financially needy students. Reducing these types of programs would minimize the negative implications for colleges’ core programs and low‑income students. The “Budget Solutions” section of this brief identifies a number of options that would result in ongoing General Fund savings.

Non‑Proposition 98 Proposals

Total Funding for CCC in 2024‑25 Is Up From Revised 2023‑24 Level. Under the Governor’s budget, total funding for the colleges would reach $18.4 billion in 2024‑25, a 2.8 percent increase over the revised 2023‑24 level. As Figure 3 shows, non‑Proposition 98 General Fund support would increase by just over 9 percent ($55 million) in 2024‑25, largely due to an increase in debt service payments on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities.

Figure 3

Total CCC Funding Increases Moderately Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2022‑23 Revised |

2023‑24 Revised |

2024‑25 Proposed |

Change From 2023‑24 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Funda |

$7,634 |

$8,425 |

$8,679 |

$255 |

3.0% |

|

Local property tax |

3,860 |

4,036 |

4,210 |

175 |

4.3 |

|

Subtotals |

($11,494) |

($12,460) |

($12,890) |

($430) |

(3.4%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Fund |

$618 |

$606 |

$661 |

$55 |

9.1% |

|

Lottery |

367 |

316 |

316 |

—b |

‑0.1 |

|

Special funds |

24 |

103 |

98 |

‑4 |

‑4.1 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,009) |

($1,025) |

($1,075) |

($50) |

(4.9%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$407 |

$407 |

$409 |

$1 |

0.4% |

|

Other local revenuec |

3,514 |

3,537 |

3,559 |

22 |

0.6 |

|

Subtotals |

($3,921) |

($3,944) |

($3,968) |

($24) |

(0.6%) |

|

Federal |

$441 |

$441 |

$441 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$16,865 |

$17,869 |

$18,373 |

$504 |

2.8% |

|

FTE studentsd |

1,100,681 |

1,100,417 |

1,098,591 |

‑$1,826 |

‑0.2%e |

|

Proposition 98 funding per FTE studentf |

$10,442 |

$11,323 |

$11,733 |

$410 |

3.6 |

|

aIncludes withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve ($11,000 in 2022‑23, $236 million in 2023‑24, and $486 million in 2024‑25). bDifference of less than $500,000. cPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. dReflects budgeted FTE students. eReflects the net change after accounting for the proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. fReflects Proposition 98 funding, including reserve withdrawals, per budgeted FTE student. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Governor Proposes No Increase in CCC Enrollment Fees. Beyond Proposition 98 funding and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund, much of CCC’s remaining funding comes from student fees (including enrollment fees) and various local sources (such as revenue from facility rentals and community service programs). The Governor proposes no increase to enrollment fees for 2024‑25. Since summer 2012, CCC enrollment fees have been held flat at $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). Community college fees in California remain the lowest of any state and significantly below the national average. In 2022‑23, community college tuition averaged approximately $5,100 nationally—more than triple the CCC enrollment fee level.

Governor’s Budget Funds One Continuing Academic Capital Project. The Governor proposes to provide $29 million in state general obligation bond funding to continue one previously authorized community college project—the College of the Siskiyous Theater and McCloud Hall renovation. The bond funds would come from Proposition 51 (2016). This project is funded for the construction phase. In 2022‑23, the state approved $1.6 million for preliminary plans and working drawings. Construction is scheduled to start in January 2025 and be completed by June 2026.

Governor Returns to Paying Cash for a Few Student Housing Projects. In response to the budget deficit the state faced last year, the 2023‑24 budget package converted 19 CCC student housing projects from being funded up front with cash to being debt financed. Specifically, the state rescinded a total of about $1 billion one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund, replacing it with $61.5 million ongoing non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for debt financing. Under the arrangement, most of the CCC projects (16) were to issue local revenue bonds or wait for a state lease revenue bond or other state financing alternative to be developed as part of the 2024‑25 budget process. Three intersegmental projects involving the Merced, Riverside, and Santa Cruz areas are being funded with UC revenue bonds. Since enactment of the 2023‑24 Budget Act, the administration has determined that three of the CCC projects (in the Napa, Santa Rosa, and Imperial Valley areas) are not good candidates for a state lease revenue bond program. The Governor’s budget proposes to return to funding these three projects up front with cash—using $50.6 million of the ongoing non‑Proposition 98 General Fund appropriation provided last year (generating $10.9 million in 2023‑24 savings).

Additional Student Housing Financing Proposal Is Likely to Be Submitted in the May Revision. The Governor’s Budget Summary indicates that the administration is committed to using a state lease revenue bond approach for financing the remaining 13 CCC projects. The Governor intends to submit a corresponding proposal at the May Revision. Given timing issues entailed in developing such a program, the administration believes no associated funding would be needed in 2024‑25.

Enrollment

In this section, we provide background on community college enrollment trends, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund enrollment growth, assess the proposal, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Several Factors Influence CCC Enrollment. Under state law, community colleges operate as open access institutions. That is, all persons 18 years or older may attend a community college. (While CCC does not deny admission to students, there is no guarantee of access to a particular class.) Many factors affect the number of students who attend community colleges, including changes in the state’s population, particularly among young adults; local economic conditions, particularly the local job market; the availability of certain classes; and the perceived value of the education to potential students.

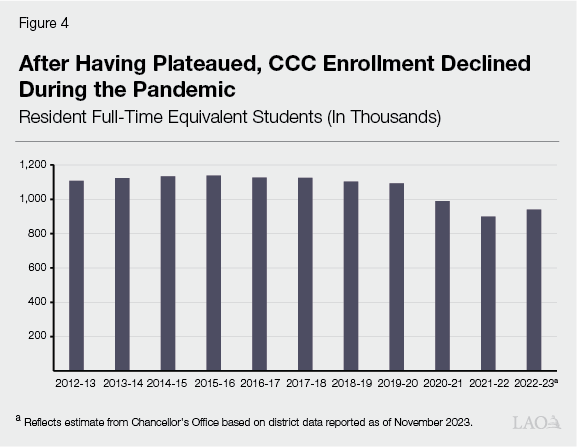

Prior to the Pandemic, CCC Enrollment Had Plateaued. Following the Great Recession, as the economy and state funding began recovering (2012‑13 through 2015‑16), systemwide CCC enrollment grew. As Figure 4 shows, CCC enrollment flattened thereafter. The plateau in CCC enrollment during this period was commonly attributed to the long economic expansion, strong labor market, and unemployment remaining at or near record lows.

CCC Enrollment Dropped Notably During the Pandemic. As Figure 4 also shows, between 2018‑19 (the last full year before the start of the pandemic) and 2021‑22, full‑time equivalent (FTE) students at CCC declined by more than 200,000 (19 percent). The drop in CCC enrollment was consistent with national community college enrollment trends over this period. While CCC enrollment declines over these years affected virtually every student demographic group, most districts reported the largest enrollment declines among African American, male, lower‑income, and older adult students. These group‑specific impacts also were consistent with national trends.

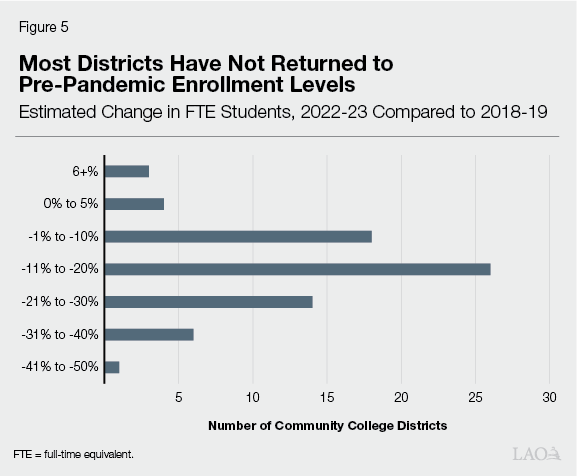

Enrollment Levels Are Increasing in Many Districts. After three years of enrollment drops, data from the Chancellor’s Office indicates that enrollment rose overall in 2022‑23—increasing by an estimated 4 percent (in FTE terms) over 2021‑22 levels. Figure 5 shows that while some districts were back at or above their pre‑pandemic enrollment levels in 2022‑23, most community colleges remained below those levels. Fall 2023 data will not be released by the Chancellor’s Office until late February 2024, but some data suggests continued growth in 2023‑24. Based on information our office received in January 2024 directly from 20 districts (representing more than one‑quarter of districts in the state), fall 2023 enrollment was strong, with districts reporting growth over fall 2022 levels of between 4 percent and 18 percent. This data suggests more districts are likely to return to their pre‑pandemic levels over the next couple of years.

Several Factors Likely Contributing to Recent Enrollment Increases. District administrators cite a number of reasons for the recent rebound in enrollment. Unemployment in the state has ticked up over the past year (increasing from 3.8 percent in September 2022 to 5.1 percent by December 2023), which likely has resulted in more individuals deciding to earn a CCC education. Many districts also have indicated they have increased enrollment among nontraditional students, including dually enrolled high school students and incarcerated students. Additionally, colleges have increased outreach to local high schools, and many colleges have created phone banks to contact individuals who recently dropped out of college or had completed a CCC application recently but did not register for classes. In addition, a number of colleges have begun to offer more flexible courses, with shorter terms and more frequent start dates (rather than only offering typical semester start dates).

State Has Certain Rules for Allocating Enrollment Growth Funds Across Districts. Statute does not specify how the state is to go about determining how much CCC growth funding to provide in any given year. Historically, the state has considered several state‑level factors, including changes in the adult population, the unemployment rate, and prior‑year enrollment trends. When the state funds growth, it provides districts with a uniform rate for each major type of instruction. (The weighted average rate is about $5,400 per student in 2023‑24.) The Chancellor’s Office uses a statutory formula to allocate that enrollment growth funding across districts. The allocation formula takes into account several local‑level factors, including local rates of educational attainment, unemployment, poverty, and enrollment. Funding for districts that are unable to reach their budgeted growth targets is eventually redistributed to other districts who grow beyond those targets.

Unused Growth Funds May Be Used for Backfilling Apportionment Shortfalls. For many years, the annual budget act has contained provisional language allowing the CCC Chancellor’s Office to allocate unused systemwide enrollment growth funding to backfill any shortfalls in CCC apportionment funding. Shortfalls can occur as a result of colleges generating lower‑than‑budgeted enrollment fee revenue or local property tax revenue. The provisional budget language allows the Chancellor’s Office to redirect unearned growth funds in this way after underlying apportionment data has been finalized, which occurs after the close of the fiscal year. After addressing any apportionment shortfalls, remaining unused enrollment funding flows into the Proposition 98 Reversion Account. Funds in this account may be redirected for any one‑time Proposition 98 purpose.

Proposal

Governor’s Budget Funds Enrollment Growth. The Governor’s budget includes $30 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for 0.5 percent systemwide CCC enrollment growth in 2024‑25. This equates to about 5,400 additional FTE students. The average base rate for each of these students is $5,440. To be eligible for these growth funds, a district must first recover to its pre‑pandemic enrollment level. The Governor’s proposed enrollment growth rate of 0.5 percent is the same rate the state has adopted the past three years. The Governor’s budget also continues the practice of including provisional language redirecting any unearned enrollment growth funds first to backfilling apportionment shortfalls.

Assessment

Likely That Some of 2022‑23 Growth Funding Will Not Be Earned by Districts. Based on data reported by the Chancellor’s Office to our office in early February 2024, $19 million of $27 million in 2022‑23 enrollment growth funding had been earned by districts. The Chancellor’s Office has identified no apportionment funding shortfalls for 2022‑23. The Chancellor’s Office plans to release final 2022‑23 enrollment and funding data by the end of February 2024. Any 2022‑23 growth funds not earned by districts or not needed for an apportionment shortfall would become available for other Proposition 98 purposes, including Proposition 98 budget solutions. (The June 2023 budget swept the entire $24 million in enrollment growth funding from 2021‑22, as none of it was earned.)

Better Information Is Coming on 2023‑24 Enrollment. As of this writing, estimating 2023‑24 CCC enrollment remains difficult given that the Chancellor’s Office is still processing fall 2023 district enrollment submissions and the spring 2024 term is just beginning. By the time of the May Revision, the Chancellor’s Office will have provided the Legislature with preliminary enrollment data for 2023‑24. This data will show which districts are reporting enrollment increases and declines and the magnitude of those changes. It also will show how many districts are on track to earn any of the 2023‑24 enrollment growth funds. Apportionment data for 2023‑24, however, will not be finalized until February 2025, such that the Legislature might not want to take any associated budget action until next year. At that time, if some or all of the 2023‑24 enrollment growth funds end up not being earned by districts or needed for an apportionment shortfall, the Legislature could redirect available funds for other Proposition 98 purposes, including Proposition 98 budget solutions.

Several Factors Could Guide 2024‑25 Enrollment Growth Decision. If some districts are on track to grow in 2023‑24, it could mean they might continue to grow in 2024‑25. Student demand also might increase in 2024‑25 if the state’s unemployment rate continues to tick upward, the job market weakens, or entry‑level wage growth slows. These developments often are accompanied by an increase in the number of individuals seeking reskilling or upskilling. By providing funding for enrollment growth in 2024‑25, the state could encourage and reward districts for expanding access to students. Countering these growth pressures, however, is demographic data indicating declines in both the college‑age population (ages 18‑24) and the broader working‑age adult population (ages 25‑64) in the state.

Recommendations

Sweep 2022‑23 Growth Funds. Once 2022‑23 enrollment and funding data are finalized later this fiscal year, we recommend the Legislature use any unearned enrollment growth funds to help achieve Proposition 98 budget savings. Based upon preliminary data, $8 million would be available as savings. This action could be one of several ways the Legislature achieves Proposition 98 savings. Given the notable downward revisions in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee over the budget window, such savings would help the state balance the budget.

Consider Forthcoming Data, Together With State’s Budget Condition, to Decide on Growth Funding for 2024‑25. We recommend the Legislature also use updated enrollment data, as well as updated data on available Proposition 98 funding, to make its decision on CCC enrollment growth for 2024‑25. If the updated enrollment data indicate districts are growing in 2023‑24, the Legislature could view the Governor’s proposed growth funding in 2024‑25 as warranted. Ultimately, though, the Legislature will want to weigh the benefits of providing more access to individuals seeking a CCC education with the need to find General Fund savings to address the state’s significant budget problem. Were updated revenue estimates at the May Revision to suggest a more significant budget problem for the state, we recommend the Legislature not provide any growth funding for community colleges in 2024‑25.

Apportionments

In this section, we focus on community college apportionments. Community colleges use their apportionment funding to cover their core operating costs. Below, we first provide background on community colleges’ core operating costs and how colleges generally cover those costs. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to provide a COLA for apportionments and select categorical programs, assess the proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

Cost Pressures

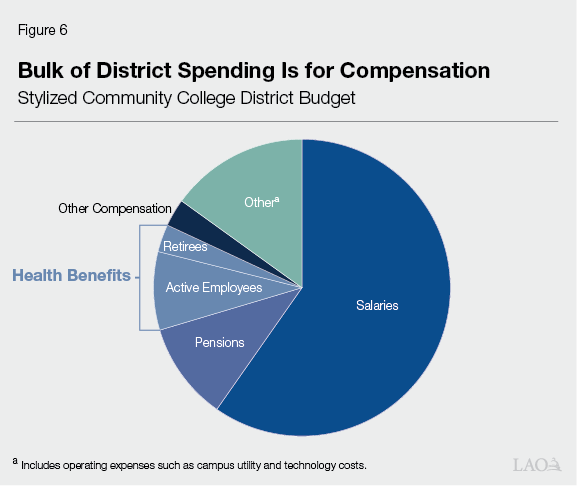

Compensation Is Largest Community College Operating Cost. Colleges use the bulk of apportionment funding on employee compensation. As Figure 6 shows, all compensation‑related costs—including salaries, retirement benefits, health care benefits, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance—typically account for 80 percent to 85 percent of a district’s budget. The remainder of a district’s budget is for various other core operating costs, including utilities, insurance, software licenses, equipment, and supplies.

Salary Decisions Are Made Locally. Most community college employees are represented by labor unions. Several unions represent faculty throughout the state, with the largest being the California Federation of Teachers. The California School Employees Association is the main union for classified staff. Each community college negotiates with the local branches of these unions. Through collective bargaining agreements, community college districts and their employees make key compensation decisions, including salary decisions. These agreements are ratified by local community college district governing boards. The Legislature does not ratify these local agreements. Over the past several years, salaries for community college faculty generally have increased. For tenure and tenure‑track faculty, the average salary has been growing slightly quicker than inflation, reaching $114,630 in 2022.

Districts Are Likely to Feel Some Salary Pressure in 2024‑25. Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, both inflation and wage growth (across the nation and in California) were at their highest levels in several decades. Although inflation and wage growth among workers have slowed noticeably over the past year, both are likely to remain above historical averages for the next few years. As a result, community college districts are likely to continue feeling pressure to provide their employees with salary increases. This is particularly true in districts that report having challenges recruiting faculty and other staff due to less competitive salary levels.

Districts’ Pension Costs Also Are Rising. About half of CCC employees (namely faculty) participate in the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), with the other half (namely staff and administrators) participating in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). Districts’ employer contribution rates for these two systems are set by the respective retirement boards, rather than at the local community college district level (meaning all college districts are subject to the same contribution rates). Districts’ pension costs have been increasing over time. In 2013‑14, districts’ employer contribution rate was 8.3 percent of payroll for CalSTRS and 11.4 percent of payroll for CalPERS. Those rates are up to 19.1 percent of payroll for CalSTRS and 26.7 percent of payroll for CalPERS in 2023‑24. Based on current assumptions, districts’ CalSTRS contribution rate is expected to stay constant at 19.1 percent in 2024‑25, whereas the CalPERS rate is projected to increase to 27.8 percent. (Community colleges are not included in the Governor’s CalPERS proposal involving changes in how a previous state supplemental payment is applied.) Accounting for both retirement systems, community college costs are expected to increase by $76 million in 2024‑25.

Colleges Face Various Other Cost Pressures. Similar to other education segments, community college districts generally also expect to see higher costs in 2024‑25 for health care premiums, insurance, equipment, supplies, and utilities. Health care costs are the largest of these remaining cost pressures. Districts are likely to face even greater pressure in this area than normal, as premiums in 2024 are increasing at historically high rates. Cost drivers include new medical technologies, increases in prescription drug costs, and inflation. Districts generally cover premium increases for their respective health care plans, though those decisions are collectively bargained. In some cases, employees are responsible for covering all or a portion of the premium increases.

COLA Is Typically Subject to Collective Bargaining at District Level. The state typically provides apportionment funding with a COLA to help districts cover operating cost increases. In most cases, districts, in turn, negotiate a COLA rate with their bargaining units. In negotiating a COLA rate with employee unions, districts typically take into account a number of factors, including changes in the costs of housing and other expenses for employees, the competitiveness of salaries relative to other districts, and the need for the district to address non‑salary cost pressures (such as pension liabilities and cost increases to utilities and other operating expenses). A relatively small proportion of districts (likely less than 10 percent) automatically apply any state‑funded COLA rate to employees.

Staffing Levels Have Declined, Particularly Among Part‑Time Faculty, Over the Past Few Years. While districts are facing pressure to increase salaries and cover pension and health care rate increases, staffing levels systemwide are down. From fall 2019 to fall 2022, the total number of CCC FTE employees declined by 2.5 percent, falling from nearly 66,000 FTE employees in fall 2019 to approximately 64,000 FTE employees in fall 2022. Part‑time faculty—which historically have made up nearly half of all CCC employees—experienced the largest decline (14 percent in both FTE and headcount terms). This decline was due to districts offering fewer course sections as a result of lower enrollment. When districts reduce course sections, they typically reduce their use of part‑time faculty, who are hired as temporary employees, compared to full‑time faculty, who are hired as permanent employees. Most districts across the state have been affected by enrollment declines and, in turn, have experienced staffing reductions. While CCC compensation costs have increased over the past several years, they have been offset somewhat due to these reductions in staffing.

Staffing Might Begin to Rebound. Though fall 2023 staffing data are not yet available, two factors discussed in the “Enrollment” section of this brief could result in districts adding somewhat more employees in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. Staffing could increase due to an enrollment rebound at community colleges and signs of a weaker labor market in the state.

Funding

Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Funding From Apportionments. All community college districts (except the statewide online Calbright College) receive funding from apportionments. The amount each district receives is based on the state’s Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). SCFF takes into account many factors, including the amount of credit and noncredit instruction each district provides. In 2023‑24, community college districts collectively received 70 percent of all their Proposition 98 funding through apportionments. The remainder of CCC Proposition 98 funding is allocated to community colleges districts through more than 40 categorical programs.

Apportionment Funding Has Increased Significantly Over Past Three Years. Although the state is not statutorily required to provide a COLA for apportionments (as it is for school districts’ LCFF), the state has a long‑standing practice of providing a COLA when Proposition 98 funds are available. Over the past three years, community colleges have received historically large COLAs—with COLAs of 5.07 percent in 2021‑22, 6.56 percent in 2022‑23, and 8.22 percent in 2023‑24. In 2022‑23, districts received an additional 8.3 percent base apportionment increase on top of the COLA. These apportionment funding increases are much higher than the average COLA rate over the past 30 years, which is just under 3 percent.

Proposition 98 Funding Per Student Is Much Higher Today Than Before the Pandemic. As a result of these apportionments increases—as well as funding increases for numerous categorical programs in recent years—budgeted per‑student Proposition 98 funding is at an all‑time high. Since 2018‑19, per‑student funding has reached new all‑time highs nearly every year. Under the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan, budgeted CCC per‑student funding in 2024‑25 would be approximately $1,500 (14 percent) higher than that pre‑pandemic level (2018‑19), after adjusting for inflation. Moreover, actual funding per student is significantly above budgeted funding per student. Though enrollment has dropped since 2018‑19, funding has not been adjusted accordingly. Rather, a series of hold‑harmless provisions has largely insulated community colleges from the fiscal impact of enrollment declines. We estimate actual funding per student in 2022‑23 is approximately $3,100 (31 percent) higher than the 2018‑19 level, after adjusting for inflation.

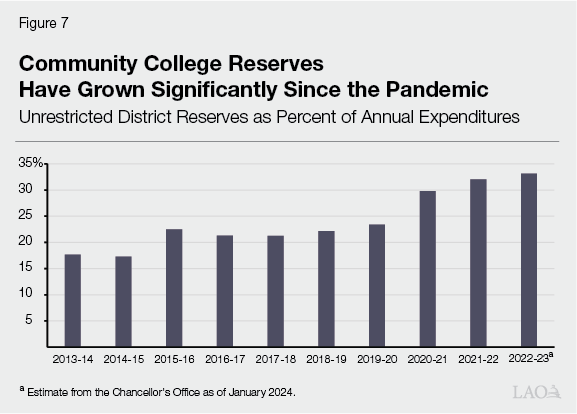

Systemwide Reserves Continue to Increase. In addition to the state’s Proposition 98 Reserve, districts maintain their own local reserves. Figure 7 shows that district unrestricted reserves increased over the past several years. Whereas unrestricted reserves totaled $1.8 billion (22 percent of expenditures) in 2018‑19, they grew to an estimated $3.1 billion (33 percent of expenditures) in 2022‑23. Both the Government Finance Officers Association and the Chancellor’s Office’s recommend that unrestricted reserves comprise a minimum of 16.7 percent (two months) of expenditures.

Funding Increases, Together With Budget Savings, Contributed to Higher Reserve Levels. The increase in districts’ local reserves is the result of at least three factors. One factor is that the state notably increased community college funding during the pandemic years despite enrollment drops. Given enrollment drops and large state augmentations (even beyond high COLA rates), districts purposefully have tended not to spend all their state allotments the past few years. Additionally, federal relief funds provided during the pandemic reduced pressure on local and state funds that colleges would otherwise have needed to cover technology and certain other operating costs. Amid these federal and state funding increases, colleges also achieved savings from staff reductions and vacancies.

Proposal

Governor Proposes COLA for Apportionments and Certain Categorical Programs. The Governor’s budget includes $69 million to cover a 0.76 percent COLA for apportionments. This is the same COLA rate the Governor proposes for the K‑12 LCFF. The Governor’s budget also includes a 0.76 percent COLA for seven CCC categorical programs, at a total cost of $9 million. The COLA rate is based on a particular price index, as described in more detail in the nearby box. The COLA rate will be revised in late April, as new data from the federal government is released at that time.

How the K‑14 Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA) Is Calculated

Lower Energy Costs May Be a Factor Behind Low COLA Rate. The state calculates a statutory COLA each year using a price index published by the federal government. This index reflects changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country. Costs for employee wages and benefits are the largest factor affecting the index, but other factors, including costs for fuel, utilities, supplies, equipment, and facilities, also affect the index. The 0.76 percent COLA rate in the Governor’s budget is below the historical average of about 3 percent. One key factor likely contributing to the low COLA rate in 2024‑25 is the recent decline in energy prices. The COLA rate for the budget year is based on prices for the 12‑month period ending in March 2024 compared to the previous 12‑month period (April 2022 through March 2023). Energy prices peaked in summer 2022 and have since fallen. Given energy prices are among the most volatile of all the factors contributing to the index, they can have an outsized effect on the COLA rate.

Assessment

Proposed COLA Worsens State’s Funding Shortfall for CCC. Under the Governor’s budget, the state has insufficient Proposition 98 funds to cover even existing CCC costs, before applying any COLA in 2024‑25. Given Proposition 98 funding is insufficient to cover CCC costs, the Governor proposes to draw down $486 million in Proposition 98 reserves. The Governor must dedicate $78 million of his proposed Proposition 98 Reserve withdrawal for covering the added ongoing cost of the proposed COLA for CCC apportionments and certain CCC categorical programs. Historically, the state has not used reserves to augment ongoing spending. Rather, the state historically has used reserves during times of recessions to mitigate program reductions.

Recommendation

Reject Proposal, Revisit Available Funding Next Year. As a first step in addressing the lowered estimates of the minimum guarantee, we recommend the Legislature not provide a COLA to CCC apportionments or any CCC categorical programs, thereby containing ongoing spending in 2024‑25. This would result in savings of $78 million Proposition 98 General Fund relative to the Governor’s budget. Under the Governor’s budget proposal, one‑time reserves are required to cover these higher ongoing costs. Such an approach sets up the state for more difficult choices next year. Were the Legislature not to provide the COLA in 2024‑25, it would lessen the ongoing shortfall for CCC programs and allow for better choices in 2025‑26. This recommendation is consistent with our office’s recommendations not to increase funding and spending expectations for CSU and UC in 2024‑25. If sufficient state revenues do not materialize over the coming months, all higher education segments face the further prospect of ongoing program cuts.

Colleges Likely Would Not Experience Significant Financial Hardship Without a COLA. While a year without a COLA would have implications for districts, it likely would be manageable given the circumstances. The likely leaner budget year comes after several years of high apportionment funding increases, including a large above‑COLA base increase in 2022‑23. Districts generally also have relatively high local reserves that could be tapped to address cost increases that are unavoidable in the near term (such as higher health care premiums or software licenses and other technology). The impact of not providing a COLA in 2024‑25 also might be mitigated by a weakening statewide labor market and slowing wage growth, making it easier for districts to recruit and retain employees.

Summer Loophole

In this section, we first provide background on SCFF, the rules for counting and reporting enrollment, and a new CCC funding protection. We then describe how a CCC policy on reporting summer enrollment will increase apportionment costs over the next several years. Next, we provide an assessment of that policy and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

Enrollment Is the Largest Component of SCFF. SCFF is the main community college funding formula. The formula consists of (1) a base allocation linked to enrollment, (2) a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and (3) a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. For each of these three components, the state sets funding rates. About 70 percent of districts’ SCFF funding is from the base allocation linked to enrollment.

Enrollment Is Counted on the “Census Date.” Community college districts typically operate four academic terms—the primary fall and spring terms, along with shorter summer and winter intercessions (often about half of the length of the primary terms). Unlike K‑12 schools, which are funded on students’ daily attendance, most community college enrollment is based on the number of students enrolled in a course on the census date. The census date is a point defined in CCC regulations as one‑fifth into a given academic term.

Regulations Give Districts Flexibility on Reporting Summer Enrollment. SCFF calculations rely on data that community college districts report. For some components of SCFF, including the low‑income student counts and student success points, districts must report their data for each fiscal year beginning with summer term and extending through spring term. (For example, data for the summer 2021 term through spring 2022 term were used for these components of the 2021‑22 SCFF calculations.) For many years, CCC regulations have contained a loophole for summer enrollment. For SCFF calculations, summer classes that have a census date in one fiscal year and end in the following fiscal year may be reported in either fiscal year. Under these regulations, districts are allowed to “double up” summer enrollment in a given fiscal year—for example, counting both summer 2021 and summer 2022 enrollment to their 2021‑22 SCFF enrollment calculations.

A New SCFF Hold Harmless Funding Policy Goes Into Effect in 2025‑26. SCFF has several funding protections that allow districts to earn more in apportionment funding than they would otherwise earn through the formula’s regular calculations and funding rates. (As discussed in the “Enrollment” section of this brief, many districts are benefiting from these provisions given their enrollment is down notably from pre‑pandemic levels.) The 2022‑23 budget modified one of these funding protections by setting a new hold harmless funding level. Specifically, beginning in 2025‑26, districts are to receive no less total apportionment funding than they received in 2024‑25. The intent of this policy is to provide a funding floor for districts experiencing enrollment declines. In addition, because the hold harmless amount will not grow by COLA each year, the intent is to eventually move all districts off the hold harmless provision and into the regular SCFF formula calculations (whereby districts have incentives to enroll low‑income students and have good outcomes for all students).

Assessment

New Hold Harmless Policy Creates a Strong Incentive for Districts to Use Summer Loophole. Districts use the summer loophole (counting two summer terms toward one fiscal year) to boost district funding in a given year above what it would be otherwise. Over the next few years, using the summer loophole will become even more appealing to districts. This is because many districts likely will be on hold harmless in 2025‑26 due to recent enrollment declines. In order to maximize this funding, they have an incentive to push as much enrollment as they can into 2023‑24. By doing so, they could boost their funding level in 2024‑25 by taking advantage of a different funding protection known as stability. (Some growing districts could receive more funding using the summer loophole if instead they push summer enrollments into 2024‑25.)

Left Unchanged, Summer Loophole Could Add Hundreds of Millions of Dollars in SCFF Costs. Systemwide, summer enrollment averages 12 percent of total annual enrollment, though the share can be as high as 20 percent in some districts. Doubling up summer enrollment in one year therefore can have large implications on districts’ funding. Estimating the cost of the summer loophole, however, is difficult given final 2023‑24 enrollment and funding data, including summer 2024 data, are not yet available. Based on our discussions with several districts and some preliminary modeling, we estimate the loophole could result in roughly $100 million in additional costs annually from 2024‑25 through 2026‑27, for a total of about $300 million in costs. SCFF costs likely would continue to be a few millions of dollars higher beyond 2026‑27, until all districts reach enrollment levels moving them off the hold harmless provision. The administration has not built these costs into their SCFF calculations. The summer loophole also will have distributional effects, as districts taking advantage of the summer loophole effectively generate more under the formula (without any workload justification) than other districts. Given projected budget deficits and the prospect of spending reductions, we think this is a particularly bad time to be raising SCFF costs and potentially redistributing available funds among districts to reward those that use a loophole.

Summer Loophole Distorts Enrollment Data. Beyond these issues, the summer loophole can obscure actual enrollment trends. A district could report an enrollment decrease between two years, for example, but that may be due solely to its decision to report two summers’ worth of enrollment in the prior year. The summer loophole thus makes enrollment tracking and legislative oversight more difficult.

Recommendation

Recommend Legislature Close Summer Loophole. We recommend the Legislature specify in statute that the summer term is to be the first term counted in a fiscal year and summer‑term enrollment is to be reported only once each fiscal year. We recommend including this new policy in June 2024 trailer legislation and making it apply starting in summer 2024. The new policy would mean that enrollment in the summer 2024 term would be counted only for 2024‑25 (and enrollment in the summer 2025 term would be counted only for 2025‑26). This approach would align summer enrollment reporting with the reporting of the other components of SCFF. (In addition, counting summer term as the first term of the fiscal year is the same as CSU’s and UC’s policy.) It also would eliminate a loophole that would otherwise drive up the cost of the formula substantially over the next few years. Finally, our recommendation would make enrollment reporting more meaningful and allow for improved legislative oversight.

Nursing Education

In this section, we first provide background on the state requirements to become a registered nurse (RN), nursing education programs, recent trends in the nursing workforce, and funding sources for CCC nursing programs. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to fund a new nursing education initiative, assess the proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

State Nursing Requirements and Programs

RNs Must Be Licensed to Work in California. California’s more than 300,000 RNs provide a variety of health care services in various settings, including hospitals, medical offices and clinics, extended care facilities, and laboratories. All RNs in the state must have a license issued by the California Board of Registered Nursing. To obtain a license, students must graduate from an approved nursing program, pass a national licensing examination, and complete certain other steps (such as undergoing a criminal background check).

Students Have Three Main Education Routes to Becoming a Nurse. In California, three main types of pre‑licensure education programs are available to persons seeking to become an RN. The most common option is for students to enroll in a four‑year program at a university culminating in a Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree. The next most common route is for students to enroll at a two‑year program at a community college culminating in an Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN). The third route is for students to enroll in a university program culminating in a Master’s of Science in Nursing (MSN) degree. Pre‑licensure master’s programs accept individuals who hold a bachelor’s degree in a non‑nursing field. Generally, students in such a master’s program complete educational requirements for an RN license in about 18 months, then continue for another 18 months to obtain an MSN. All three types of pre‑licensure programs combine classroom instruction, “hands on” training in a simulation lab, and clinical placement in a hospital or other health facility.

Community Colleges Are Key Providers of Nursing Education. In 2022‑23, 144 public and private postsecondary institutions in California offered a total of 152 pre‑licensure programs. Figure 8 shows community colleges are a major educator of RNs, offering 77 of the state’s 92 associate degree programs. A total of 13,982 students graduated from a pre‑licensure program in 2022‑23—39 percent with an associate degree, 55 percent with a bachelor’s degree, and 6 percent with a master’s degree.

Figure 8

California Has Many Pre‑Licensure Nursing Programs

2022‑23

|

Programs |

Graduates |

|

|

Associate Degree in Nursing |

||

|

CCC |

77 |

4,488 |

|

County of Los Angeles program |

1 |

73 |

|

Private institutions |

14 |

866 |

|

Subtotals |

(92) |

(5,427) |

|

Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing |

||

|

CSU |

17 |

1,804 |

|

UC |

2 |

94 |

|

Private institutions |

28 |

5,851 |

|

Subtotals |

(47) |

(7,749) |

|

Master’s of Science in Nursinga |

||

|

CSU |

1 |

42 |

|

UC |

4 |

176 |

|

Private institutions |

8 |

588 |

|

Subtotals |

(13) |

(806) |

|

Totals |

152 |

13,982 |

|

aReflects programs enrolling students who do not yet have a registered nursing license. |

||

Community Colleges Have Developed BSN Partnerships With Universities. State law limits community college RN programs to offering the ADN. In a number of cases, though, community colleges have collaborated with universities, particularly CSU campuses, to design pathways from the ADN to the BSN. For example, 13 Los Angeles‑area community colleges have partnered with CSU Los Angeles to create an accelerated ADN‑to‑BSN program. In that program, CCC students begin taking upper‑division courses through the university while still enrolled in their ADN program, enabling them to earn a BSN from CSU Los Angeles within one year of graduating from one of the partnering community colleges.

Nursing Workforce

State Faced Nursing Shortage Throughout the 2000s. Beginning in the 1990s, health care employers indicated that the size of the nursing workforce was insufficient to adequately staff health care facilities—particularly hospitals, which are statutorily required to maintain minimum nurse‑to‑patient ratios. Despite paying higher wages and encouraging—and in some cases requiring—existing staff to work overtime, the state continued to experience a gap between supply of and demand for RNs throughout the 2000s.

State Responded to Shortage by Expanding Capacity in Nursing Programs. The Legislature responded to this nursing shortage in a number of ways, most notably by providing targeted funding to the state’s public higher education segments to increase enrollment in their pre‑licensure nursing programs. As a result of these and other factors (including an increase in the number of private colleges launching nursing programs), the number of students annually graduating and obtaining an RN license more than doubled during the 2000s—from about 5,100 graduates in 2000‑01 to 10,600 graduates by 2010‑11.

Prior to Pandemic, Nursing Workforce Was in Good Shape Overall. According to a 2017 forecast prepared by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) for the Board of Registered Nursing, the number of nursing graduates in the state (approximately 11,000 per year across the state’s pre‑licensure programs) likely was sufficient to ensure an adequate nursing workforce in the state through at least 2027. While the overall nursing workforce was sufficient to meet overall workforce demands, some hospital officials reported difficulty attracting nurses to work in particular regions of the state (including the Central Valley and certain rural areas). In addition, the UCSF report cautioned that reductions in the employment rates of older RNs could affect the forecast.

Nursing Shortage Re‑Emerged as a Result of the Pandemic. During the pandemic, many older RNs left nursing and some younger RNs quit their nursing jobs due to higher stress levels and family or other personal considerations. In addition, many pre‑licensure nursing education programs experienced enrollment declines due to social distancing requirements, reduced access to clinical sites, and less student demand. These factors resulted in a reduction of the supply of RNs compared with previous projections and a mismatch between supply and demand. According to a February 2024 report by UCSF (unpublished), there currently is an estimated statewide supply‑demand gap of 17,000 FTE nurses. Hospitals and other health care employers are using various means in response to the short‑staffing, including paying nurses to work more overtime and using more traveling nurses (who live in other states and come to California to work for short periods of time).

Statewide Shortage Is Projected to Close Within Four Years. With the pandemic having subsided, nursing schools in the state have reported returning to pre‑pandemic levels of enrollment. All three types of pre‑licensure nursing programs anticipate further growth in the coming years. The number of new graduates from these programs is anticipated to fill more of the expected job openings. Given these developments, UCSF forecasts that the supply‑demand mismatch will gradually decline over the next few years, closing entirely by 2028. UCSF cautions, however, that if newly graduated RNs and experienced nurses are not retained in the workforce due to burnout or job dissatisfaction, the shortage could persist. Also, the study cautions that even were supply numbers to match demand on a statewide basis, regional differences could persist.

CCC Nursing Funding

Main Source of CCC Nursing Funding Is Apportionments. Just like other types of instruction, community college districts claim apportionment funding (through SCFF) for each FTE student enrolled in one of their nursing programs. Under SCFF, community college districts receive additional funding if an enrolled student is low income and for each successful student outcome (including graduation). We estimate that community college districts generated about $100 million in SCFF funding for the 11,845 FTE nursing students enrolled in 2022‑23 (about $8,500 per actual FTE student).

State Also Funds a CCC Nursing Categorical Program. Since 2006‑07, the state also has funded a CCC nursing categorical program designed to expand enrollment and provide supplemental student support (such as tutoring). Since 2009‑10, the Legislature has provided $13.4 million annually in Proposition 98 General Fund. Funding is distributed through grants to virtually every ADN program in recognition of the relatively high cost to educate nurses. High costs are mainly due to smaller required student‑to‑faculty ratios in simulation labs and clinical settings as well as the need for specialized equipment.

Colleges Also Can Use Strong Workforce Program and Other Categorical Program Funds for Nursing Education. In addition to providing supplemental funds for nursing specifically, since 2016‑17, the Legislature has provided ongoing funding for the CCC Strong Workforce Program (SWP). The associated $290 million in Proposition 98 General Fund support is intended to help career technical education programs (like nursing) cover their higher instructional costs. SWP funds also are intended to make programs more aligned with industry demand and to facilitate regional planning and coordination. The majority of SWP funds go directly to colleges, with the remainder allocated to eight regional SWP consortia. Based on our discussions with several consortia and colleges, some SWP funding is being used annually for nursing. Some SWP funds, for example, are helping to purchase lab equipment or start new programs. In addition to SWP funds, colleges can use funding they receive from the Student Equity and Achievement program and other student services programs to support their nursing students.

Some CCC Nursing Programs Also Receive State‑Funded “Song‑Brown” Grants. Originally established by Chapter 1175 of 1973 (SB 1224, Song), the Song‑Brown program was created to address shortages of primary care physicians by increasing support for training programs. Since that initial legislation, the Song‑Brown program has expanded to support nursing and certain other education and training programs. Recently, the Legislature has provided $50 million one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund over three years ($20 million in 2022‑23 and $15 million each in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25) for grants specifically to pre‑licensure nursing programs in the state. Priority is given to programs in medically underserved areas that prepare students to serve in multi‑cultural communities, low‑income neighborhoods, and rural communities. In March 2023, the Department of Health Care Access and Information (HCAI), which administers this initiative, awarded a total of $17 million to 34 nursing programs, including 17 community college ADN programs. HCAI intends to announced the next round of grantees in March 2024.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor’s Budget Includes $60 Million for Nursing Education. The 2023‑24 higher education trailer legislation, Chapter 50 of 2023 (SB 117, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), included a five‑year plan to provide additional funding for CCC nursing programs. The legislation appropriated a total of $300 million Proposition 98 General Fund over five years ($60 million annually from 2024‑25 through 2028‑29) so as to “expand nursing programs and bachelor of science in nursing partnerships to grow, educate, and maintain the next generation of registered nurses through the community college system, subject to future legislation.” The Governor’s budget provides $60 million for 2024‑25. The Governor’s Budget Summary indicates that details on how the funds would be used is “subject to future statutory changes.”

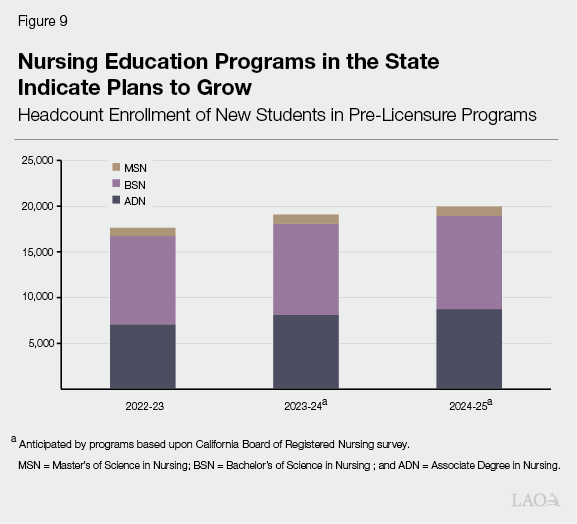

Assessment

Nursing Enrollment Is Back on Track. After declining during the pandemic, nursing programs reported in fall 2023 that they have capacity and plans to increase enrollment slots, as Figure 9 shows. Nursing programs also are reporting strong demand from students again, with community college and many other nursing programs reporting far more applications than they can accommodate. CCC programs have an incentive to enroll these students because they are funded based on enrollment and receive additional state funding for their nursing programs. Private programs, meanwhile, have an incentive to fill enrollment slots with tuition‑paying students. Given these circumstances, it is unclear why additional state funding is needed as proposed in the Governor’s budget.

SWP Designed to Address Regional Challenges. To the extent regional supply challenges persist, existing SWP funding is well‑suited to support nursing programs. The underlying rationale for SWP is that some programs (just like nursing) have especially high costs due to equipment and low student‑faculty ratios. In addition, the Legislature recognized when it created SWP that some industry sectors (like health care) might benefit from regional coordination and planning. The SWP structure allows for providers and employers to identify workforce needs and develop a regional strategy. Data provided by the Chancellor’s Office show that all eight regional consortia have large annual surpluses of SWP funding (particularly the Central Valley/Mother Lode, South Central Coast, and Inland Empire/Desert consortia). These funds are available to use for nursing programs and other local and regional workforce priorities.

Staffing Attrition Appears to Be Key Threat to a Balanced Workforce in the State. Various studies have identified dissatisfaction among nurses. A 2022 survey of RNs by the Board of Registered Nursing found that 6 percent of RNs feel “completely burned out,” with another 31 percent reporting that they are “definitely burning out.” The highest burnout rates are most common among nurses under 45 years old. UCSF has warned that shortages could persist if RNs are not retained in the workforce. State funding for community colleges, as proposed by the Governor, would not address this problem. UCSF recommends instead that employers “redouble their efforts to retain experienced RNs” and develop programs for newly graduated RNs to promote successful transition into the workforce. A number of researchers and policy groups suggest that health care employers consider a number of evidence‑based strategies toward that end, including providing more workplace flexibility, providing services such as childcare, and developing peer support groups. Such employer initiatives could help not just with retaining existing staff but potentially attracting back former RNs.

Recommendation

Recommend Legislature Reject Proposal. Given that data suggests the current mismatch between supply and demand of RNs is temporary and that lack of state funding does not seem be a key reason underlying the shortage, we recommend the Legislature reject this proposal. To the extent individual regions continue to seek increases in their nursing supply pipeline in response to local shortages, colleges already have funding from apportionments, SWP, and other state programs that can be used for this purpose.

Budget Solutions

In this section, we discuss a number of legislative options for achieving additional CCC savings in light of the state’s budget situation and the significant downward revisions to the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

State Adopted Many One‑Time CCC Initiatives Over Past Three Years. From 2021‑22 through 2023‑24, the Legislature approved a total of about $3 billion in one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund support for more than 60 one‑time CCC initiatives and projects. Some of the largest appropriations were for facilities maintenance, student outreach, student basic needs, and an initiative for faculty to create open educational resources.

State Also Expanded Funding for Ongoing CCC Programs. During the past several years, the state has appropriated ongoing funding both to create new CCC programs and to expand existing ones. For example, the state created a CCC student mental health program and doubled funding for the California Apprenticeship Initiative. In some cases, the CCC augmentations provided by the state have been exceptionally large. For example, in 2022‑23, the state increased annual funding for the long‑standing Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program from $490,000 to $200.5 million (a 400‑fold increase).

Recommend Reverting Unallocated and Unspent Funds to Address CCC Budget Gap in 2023‑24. As we discuss in the “Overview” section of this brief, the CCC budget has an approximately $800 million gap between current spending and available funding under our office’s February revenue estimates. The budget gap could end up being higher or lower depending upon revenue developments over the coming months. Under our recommended approach, Proposition 98 reserves likely could help address a small part of the budget gap in 2023‑24, but hundreds of millions of dollars likely still would be needed in other budget solutions. One‑time solutions are a typical way for addressing reductions in the current‑year minimum guarantee, as these types of solutions tend to be the least disruptive. Figure 10 provides a list of ways the Legislature could achieve one‑time savings. In many cases, the identified funds are available because of insufficient take‑up rate by colleges or students for newly created programs. In many cases, additional savings are likely to emerge as spending data for 2023‑24 is collected and reported. The Legislature could consider our list a starting point, adding items, if needed, as more information becomes available in the coming months.

Figure 10

Some Funds From Recent CCC Initiatives Remain Available for Budget Solution

Proposition 98 General Fund One‑Time Solutions (In Millions)

|

Program |

Amount |

Implementation Update |

|

Strong Workforce Program |

$381a |

Amount shown reflects total unspent regional and district funds of $27.4 million from 2020‑21, $105.7 million from 2021‑22, and $248 million from 2022‑23. Unspent funds from years prior to 2020‑21 might still be available to sweep too. By March 2024, the Chancellor’s Office will have an update on regional and district spending from 2023‑24 allocations. (In 2023‑24, regions received $110.4 million and districts received $165.5 million.) |

|

Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance program |

177a |

Of the $200.5 million ongoing appropriated for this program in 2022‑23, only $23.3 million was claimed by districts for reimbursement. Program participation might be low again in 2023‑24. The Legislature will have an update on how much was claimed for reimbursements in 2023‑24 by June 2024. |

|

Health care pathways for English learners |

100 |

The 2022‑23 budget provided $130 million for allocation over three years ($30 million in 2022‑23 and $50 million each in the following two years). The first round of awardees, which includes community colleges and adult schools, was announced in summer 2023 and the first $30 million was disbursed in December 2023. |

|

Student Success Completion Grant |

100a |

In 2022‑23, the state provided $413 million for these grants, which are available to financially needy students attending college full time. According to the Chancellor’s Office, colleges have not been able to fully award that amount because there were not enough eligible students. Additional savings might be realized in 2023‑24 depending on the take‑up rate. (The 2023‑24 budget provided $363 million for the program.) |

|

Zero Textbook Cost initiative |

66 |

The 2021‑22 budget provided $115 million one‑time funding for this initiative. As of the end of February 2024, the Chancellor’s Office expects to have allocated $48.6 million for grants and other program expenses. |

|

Part‑time Faculty Office Hours program |

51a |

Amount shown includes savings of $27 million from 2021‑22 and $23.6 million from 2022‑23 due to low participation by districts. Program might have additional savings in 2023‑24. The Legislature will have an update on how much was claimed for reimbursements in 2023‑24 by June 2024. (The 2023‑24 budget provided $24 million for the program.) |

|

California Apprenticeship Initiative |

43 |

Amount shown includes savings of $2.4 million from 2021‑22 and $10.2 million from 2022‑23, as well as $29.9 million in unallocated funds from 2023‑24. |

|

Classified Employee Summer Assistance program |

10a |

The 2022‑23 budget provided $10 million ongoing for this new program. The Chancellor’s Office reports low participation by employees in 2022‑23. Systemwide, 128 classified employees participated, generating a total of $473,000 in program costs. Program might have additional savings in 2023‑24 if participation remains low. |

|

Enrollment growth |

8 |

Amount shown reflects an estimate of unearned and unused enrollment growth funds in 2022‑23. (The June 2023 budget reverted the entire $24 million in enrollment growth funding from 2021‑22, as none of it was earned.) |

|

Calbright College |

—b |

At the end of 2022‑23, Calbright had $43 million in remaining one‑time startup funds. By early March 2024, Calbright will provide an update on year‑to‑date spending in 2023‑24. |

|

COVID‑19 block grant |

—b |