LAO Contact

March 5, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

Overview of the Federal Fiscal Responsibility Act’s Impacts on CalWORKs

Summary. The federal Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA) introduced multiple changes to the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program’s rules and requirements. Although these changes do not go into effect until 2025‑26, the 2024‑25 Governor’s budget includes proposals that could benefit from being considered in the context of these changes. In this post, we provide background on the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program, information on the upcoming federal changes and how they are likely to impact the CalWORKs program, and comments and questions for the Legislature to consider as it determines if and how to respond to the federal changes.

Background

The CalWORKs program was created in 1997 in response to the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation that created the federal TANF program. CalWORKs provides cash grants and job services to low-income families. In 2022‑23, CalWORKs served approximately 330,000 households monthly. The program is administered locally by counties and overseen by the state Department of Social Services (DSS).

Funding

Federal, State, and County Governments Share Program Costs. Federal law allows for some state flexibility in the use of federal TANF funds. California receives $3.7 billion annually for its TANF block grant, over $2 billion of which goes to CalWORKs (the remainder helps fund aid for some low-income college students and various smaller human services programs). To receive its annual TANF block grant, the state must spend a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) amount from state and local funds to provide services for families eligible for CalWORKs. This MOE amount is approximately $3 billion annually (which can be spent directly on CalWORKs or other programs that meet federal requirements).

Eligibility

Grants Based on Number of Eligible Family Members, Not Overall Family Size. Monthly CalWORKs grant amounts are set according to the size of the assistance unit (AU). The size of the AU is the number of CalWORKs-eligible people in the household. Grant amounts are adjusted based on AU size—larger AUs are eligible to receive larger grant amounts—to account for the increased financial needs of larger families. As of December 2023 (when the most recent analysis was conducted), about 40 percent of CalWORKs cases included everyone in the family (and thus the AU size and the family size were the same). In the remaining 60 percent of cases, though, one or more people in the family were not eligible for CalWORKs and therefore the AU size was smaller than the family size.

Family Members May Be Ineligible for CalWORKs for Several Reasons. Most commonly, people are ineligible for CalWORKs because they (1) exceeded the lifetime limit on aid for most adults (currently 60 months, explained below), (2) currently are sanctioned for not meeting some program requirements (such as work requirements, explained below), or (3) receive Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) benefits (state law prohibits individuals from receiving both SSI/SSP and CalWORKs). Additionally, individuals may be ineligible due to their immigration status. Undocumented immigrants, as well as most immigrants with legal status who have lived in the United States for fewer than five years, are ineligible for CalWORKs. More eligibility requirements exist for adults than for children, so in some cases, a child or children are the only family members eligible for CalWORKs.

Lifetime Limit on Aid Exists for Most Adult CalWORKs Participants. Most adults may only receive cash aid for a total of 60 months throughout their lifetime. Some exemptions exist, allowing some adults to exceed the lifetime limit or receive aid that does not count towards the limit. For example, adult recipients age 60 or older or those with disabilities are not subject to the time limit. States can only spend TANF and MOE funds on cases within this lifetime limit or on cases exempt from the limit (such as those mentioned above or child-only cases in which the adult[s] in the household are ineligible for aid due to immigration status or receipt of SSI/SSP benefits). Throughout this post, we refer to these cases as “TANF/MOE-funded” cases. Children of adults who exhaust the 60-month time limit may continue to receive cash aid, if otherwise eligible, up to age 18. These cases are often referred to as “safety net” cases. Safety net cases are funded with non-MOE General Fund dollars and are not subject to time limits.

Many Adult CalWORKs Participants Must Meet Work Requirements. Most adults receiving CalWORKs assistance must be employed or participate in activities intended to lead to employment, known as welfare-to-work (WTW) activities. Counties have flexibility in the types of WTW activities and services they provide to these individuals, often called work-eligible CalWORKs participants.

Performance Measures

The Federal Government Measures Program Success Through Work Participation Rate (WPR) Requirements. The federal TANF program places heavy emphasis on states’ WPR, or the percentage of adult participants engaging in required WTW activities. The WPR is currently the only federal measure of program performance. Under federal rules, at least 50 percent of all families and 90 percent of two-parent families receiving TANF/MOE-funded cash assistance (and with work-eligible adults in the family) must work or engage in WTW activities for 20 to 35 hours per week, depending on their family makeup. Federal law outlines specific WTW activities that count toward the WPR requirements.

States Incur Financial Penalties for Failing to Meet WPR Requirements. Federal financial penalties for failing to meet the WPR requirements start at 5 percent of a state’s annual TANF grant. Penalties increase (up to a maximum penalty of 21 percent) each successive year a state fails to meet the requirements. A state that meets the all families requirement (50 percent participation) but not the two-parent requirement (90 percent participation) incurs a smaller penalty than it would if it had failed to meet both requirements.

Meeting All WPR Requirements Has Been Challenging for California. Since 2007‑08, California has failed to meet at least one WPR requirement annually. California state law stipulates if the state fails to meet the WPR requirement(s) and incurs a federal penalty, counties that did not meet the WPR requirement(s) locally incur a portion of the penalty’s cost. States may appeal a penalty. Figure 1 summarizes California’s recent penalties and appeals. California has submitted appeals for all penalties incurred to date. As of August 2023, the final penalties from 2011‑12 to 2013‑14 had not been assessed (assessing the penalties would reduce the state’s TANF grant in the assessment year) and the 2014‑15 to 2018‑19 penalties were in dispute.

Figure 1

California’s Previous Penalties and Appeals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Federal Fiscal Year |

All Families WPR Requirement |

Two‑Parent WPR Requirement |

Original |

Current |

Revised Estimated |

|

2007‑08 |

Failed |

Met |

$48 |

— |

— |

|

2008‑09 |

Failed |

Met |

114 |

— |

— |

|

2009‑10 |

Failed |

Met |

180 |

— |

— |

|

2010‑11 |

Failed |

Met |

246 |

— |

— |

|

2011‑12 |

Failed |

Failed |

312 |

$165 |

$12 |

|

2012‑13 |

Failed |

Failed |

378 |

231 |

6 |

|

2013‑14 |

Failed |

Failed |

444 |

297 |

5 |

|

2014‑15 |

Met |

Failed |

93 |

66 |

13 |

|

2015‑16 |

Met |

Failed |

9 |

9 |

5 |

|

2016‑17 |

Met |

Failed |

14 |

14 |

13 |

|

2017‑18 |

Met |

Failed |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

2018‑19 |

Met |

Failed |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

2019‑20 |

Met |

Failed |

5 |

— |

— |

|

2020‑21 |

Met |

Failed |

11 |

— |

— |

|

2021‑22 |

Met |

Failed |

To Be Determined |

To Be Determined |

To Be Determined |

|

Totals |

$1862 |

$791 |

$64 |

||

|

aReflects most recent correspondence from Administration for Children and Families. bIncludes penalty relief provided for “significant progress” towards WPR target, and the impact of a penalty reduction in any given year on the penalty calculation/amount in following years. |

|||||

|

WPR = work participation rate. |

|||||

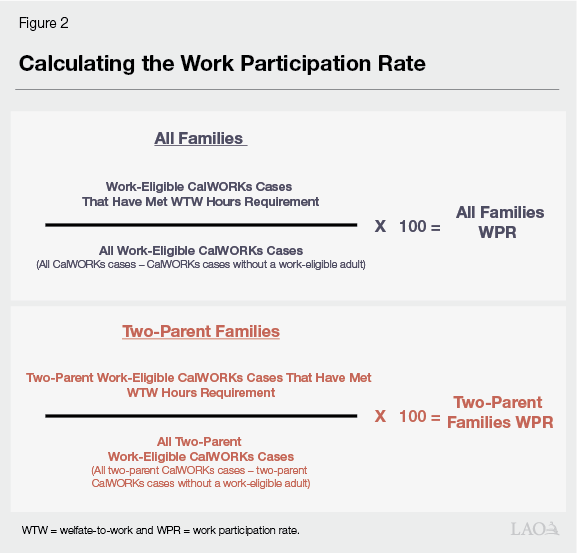

Some Cases Are Excluded From the WPR Calculation. CalWORKs households without work-eligible adult(s)—such as those with adults who do not qualify for assistance or who have exceeded the 60-month assistance limit—are excluded from the WPR calculation. The 2022‑23 WPR calculation excluded approximately 170,000 of these types of cases monthly. Figure 2 illustrates how the all families and two-parent families WPRs are calculated.

Federal WTW Requirements Focus on Core WTW Activities. As mentioned, the federal government requires most adult recipients of TANF/MOE-funded aid to participate in WTW activities for a certain number of hours each week, depending on family composition. Federal rules also dictate how many of those hours must be spent on work or work-like activities, which are called “core” WTW activities. To fulfill federal requirements (and to be counted as meeting the WTW requirements in a state’s WPR), most individuals must spend the majority of their WTW hours on core activities. Core activities include, but are not limited to, employment, community service, and job search activities. Noncore activities include certain job skills training and educational activities.

States Have Some Flexibility in the Types of WTW Activities and Services Provided. In 2012, the Legislature modified state rules governing allowable WTW activities. The modified WTW rules provide greater flexibility for participants to receive services aligned with addressing barriers to employment, such as mental health issues. California’s rules provide more flexibility than the federal rules on the types of activities that can be counted towards WTW participation. Additionally, California does not dictate how many hours an individual must spend on core activities. Therefore, some CalWORKs participants meet their WTW requirements through mostly noncore activities, such as barrier removal or education. Generally, individuals who spend more time on noncore activities than is allowable under federal rules are included in the state’s work-eligible caseload (the WPR’s denominator), but are excluded from the number of cases meeting the WTW requirements (the WPR’s numerator).

California and Other States Often Fail to Meet Two-Parent WPR Requirement. In 2022, over 98 percent of states, including California, met the all families WPR requirement. However, only 35 percent met both the all families target and the higher two-parent families target. Almost half of all states did not provide any TANF/MOE-funded benefits to work-eligible two-parent households, which allowed them to avoid the two-parent WPR requirement entirely.

State Collects Data on Additional Performance Measures Alongside WPR. California established the CalWORKs Outcomes and Accountability Review (Cal-OAR), a local program management system, through the 2017‑18 Budget Act. Cal-OAR is designed to facilitate improvement of county CalWORKs programs through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of program outcomes and best practices. The system, implemented in July 2021 (after a COVID-19 related delay in 2020‑21), includes performance measures on engagement, participation, supportive service delivery, participants’ educational attainment, participants’ employment and wages, and program exits and reentries. A workgroup of DSS and legislative staff, county representatives, the County Welfare Directors Association of California, CalWORKs recipients, and other relevant entities selected the performance measures to align with the programmatic goals of supporting both self-sufficiency amongst work-eligible Californians and improving low-income child and family well-being.

Key Components of Federal TANF Legislation

The FRA introduced multiple changes to the TANF program’s rules and requirements. We discuss the key components of the FRA below.

Caseload Reduction Credit and WPR

States Receive Caseload Reduction Credits to Reduce WPR Requirements. States can receive a caseload reduction credit if their overall TANF/MOE-funded caseload has declined relative to a specified base year. From 2005 to 2025, the base year is federal fiscal year 2004‑05. As an example, a state with an overall caseload decline of 10 percent in the most recently completed federal fiscal year relative to 2004‑05 would receive a caseload reduction credit of 10 percentage points, while a state with a 20 percent decrease in caseload (relative to 2004‑05) would receive a reduction credit of 20 percentage points. A state can receive both an all families caseload reduction credit and a two-parent families caseload reduction credit based on how its overall caseload and two-parent caseload have changed compared to the base year. A state’s reduction credits are subtracted from the standard WPR requirements (50 percent for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families) to reach the state’s adjusted WPR requirements. Figure 3 summarizes California’s annual caseload reduction credits and corresponding WPR requirements since 2009.

Figure 3

California’s Previous Caseload Reduction Credits, WPR, and WPR Requirements

|

All Families |

|||||

|

FFY |

Required Rate |

Caseload Reduction Credit |

State Adjusted WPR Requirement |

California’s WPR |

WPR Requirement Status |

|

2007‑08 |

50% |

21 |

29 |

25 |

Failed |

|

2008‑09 |

50 |

21a |

29 |

27 |

Failed |

|

2009‑10 |

50 |

21a |

29 |

26 |

Failed |

|

2010‑11 |

50 |

21a |

29 |

28 |

Failed |

|

2011‑12 |

50 |

— |

50 |

27 |

Failed |

|

2012‑13 |

50 |

— |

50 |

25 |

Failed |

|

2013‑14 |

50 |

— |

50 |

30 |

Failed |

|

2014‑15b |

50 |

— |

50 |

56 |

Met |

|

2015‑16 |

50 |

— |

50 |

61 |

Met |

|

2016‑17 |

50 |

— |

50 |

64 |

Met |

|

2017‑18 |

50 |

— |

50 |

57 |

Met |

|

2018‑19 |

50 |

16 |

34 |

55 |

Met |

|

2019‑20 |

50 |

25 |

25 |

51 |

Met |

|

2020‑21 |

50 |

30 |

20 |

52 |

Met |

|

2021‑22 |

50 |

41 |

9 |

48 |

Met |

|

Two‑Parent Families |

|||||

|

FFY |

Required Rate |

Caseload Reduction Credit |

State Adjusted WPR Requirement |

California’s WPR |

WPR Requirement Status |

|

2007‑08 |

90% |

90 |

— |

27 |

Met |

|

2008‑09 |

90 |

90a |

— |

29 |

Met |

|

2009‑10 |

90 |

90a |

— |

36 |

Met |

|

2010‑11 |

90 |

90a |

— |

34 |

Met |

|

2011‑12 |

90 |

— |

90 |

31 |

Failed |

|

2012‑13 |

90 |

— |

90 |

31 |

Failed |

|

2013‑14 |

90 |

— |

90 |

26 |

Failed |

|

2014‑15b |

90 |

— |

90 |

61 |

Failed |

|

2015‑16 |

90 |

— |

90 |

70 |

Failed |

|

2016‑17 |

90 |

— |

90 |

68 |

Failed |

|

2017‑18 |

90 |

— |

90 |

38 |

Failed |

|

2018‑19 |

90 |

26 |

64 |

31 |

Failed |

|

2019‑20 |

90 |

31 |

60 |

28 |

Failed |

|

2020‑21 |

90 |

34 |

56 |

23 |

Failed |

|

2021‑22 |

90 |

49 |

41 |

24 |

Failed |

|

aDue to the American Recovery and Investment Act of 2009, states could receive the caseload reduction credit from either 2007 or 2008 for WPR calculation from 2008 to 2011. In California, the caseload reduction credit for 2008 was larger than the 2007 credit and was therefore used. bSome CalWORKs cases without a work‑eligible adult were moved out from the CalWORKs WPR calculation and WINS cases were added to the calculation in FFY 2014‑15. cWINS two‑parent cases were removed from the two‑parent WPR calculation starting with FFY 2017‑18. |

|||||

|

WPR = work participation rate; FFY = federal fiscal year; and WINS = Work Incentive Nutrition Supplement. |

|||||

The FRA Establishes a New Base Year for Caseload Reduction Credit Calculations. Beginning October 1, 2025, caseload reduction credits will be calculated against a base year of federal fiscal year 2014‑15 instead of 2004‑05.

MOE Funds and the Work Incentive Nutrition Supplement (WINS) Program

California Uses MOE Funds for the WINS Program. WINS, introduced in 2014, provides specific CalFresh households with additional CalWORKs-funded monthly food benefits of $10. (CalFresh provides nutrition assistance to low-income Californians.) To qualify for WINS, households cannot also receive CalWORKs benefits and must include an adult working sufficient hours to meet the TANF WTW requirements. In 2022‑23, approximately 124,000 CalFresh households received WINS benefits monthly. WINS benefits are considered TANF assistance, as the program is funded with MOE dollars, and households receiving the benefit are included in the state’s WPR calculations.

FRA Set New Rules for Benefits Like WINS. Beginning October 1, 2025, working families enrolled in other programs like CalFresh must receive at least $35 in monthly MOE-funded benefits to be included in state WPR calculations. Starting in state fiscal year 2025‑26, WINS would only help California meet its WPR requirements if monthly benefits were increased from $10 to $35. This change would increase the annual cost of WINS by about $40 million.

Multistate Performance Measurement Pilot Program

The FRA Authorized a Five-State Pilot Project for Measuring Work Outcomes. The pilot will launch on October 1, 2024 and states will have the opportunity to apply to participate. States selected to participate will not be required to meet the WPR requirements for the duration of the six-year pilot. Instead, we understand performance of these states’ TANF programs will be measured by the percentage of work-eligible individuals employed six months after exiting the program, the earning levels of those individuals six and 12 months after program exit, and other indicators of family stability and well-being (which are yet to be determined by the federal government). At the beginning of the pilot, participating states will agree with the federal government on performance benchmarks for these measures. Participating states could be removed from the pilot for failing to meet these performance benchmarks. Removed states would again be subject to the same WPR requirements and potential penalties as non-pilot states going forward. DSS expects to receive additional information on the pilot requirements and how to apply in spring or summer 2024.

Work Outcomes Reporting Requirements

Current TANF Reporting Requirements Focus on Measuring Program Participation. While the WPR requirements are the only federal performance measures with targets (and financial penalties associated with failing to meet those targets), states are also federally required to submit other information on program participation. These reporting requirements include the number of program applications received, caseload, number of adult and child recipients, recipients’ employment status, number of program exits, and other participation measures. States may face a federal financial penalty for failing to submit the required information.

The FRA Introduces New Reporting Requirements on Program Outcomes. Beginning October 1, 2024, each state must report annually on the attainment of high school diplomas or equivalent amongst program participants under age 24 and job entry, job retention, and median earnings of work-eligible program participants after program exit. We understand these reporting requirements will not include targets for states to meet or associated penalties for failing to meet those targets, but may trigger financial penalties if a state does not submit the required information. The federal Administration for Children and Families indicated it plans to issue regulations on these new reporting requirements in spring 2024.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we provide comments and questions for the Legislature to consider as it determines if and how to respond to the upcoming federal changes mentioned above.

Caseload Reduction Credit and WPR

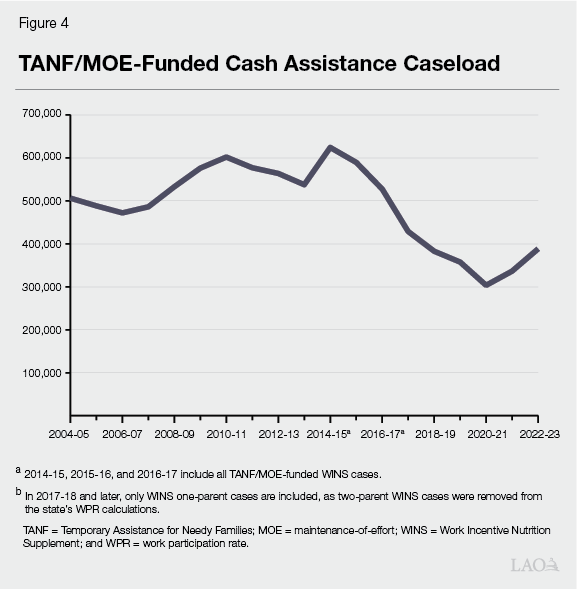

California’s Caseload Has Declined Relative to 2014‑15. In federal fiscal year 2014‑15, California’s average monthly CalWORKs caseload (excluding cases not receiving TANF or MOE funds) was about 446,000. About 178,000 WINS cases also met TANF work requirements, creating a total TANF/MOE-funded cash assistance caseload of approximately 624,000. Between federal fiscal year 2014‑15 and 2022‑23, the TANF/MOE-funded cash assistance caseload declined by almost 40 percent, as shown in figure 4.

California’s Annual Caseload Reduction Credits Likely to Increase Beginning in 2025‑26. As mentioned, large reductions in caseload relative to the base year generally translate to similarly large caseload reduction credits. Given the significant reduction in CalWORKs caseload relative to federal fiscal year 2014‑15, the administration is projecting the state’s annual all families and two-parent families caseload reduction credits will increase with the base year change in federal fiscal year 2025‑26. The administration indicated that based on initial projections, the all families reduction credit may reach up to 50 percentage points. This would lower the state’s all families WPR requirement to zero or to near zero. At this time, the administration’s reduction credit estimates are similar to our office’s independently forecasted estimates. These estimates may change as caseload changes over the next year. We will revisit the estimates when additional caseload information is available.

Change May Provide Opportunity to Increase Focus on State-Specific CalWORKs Goals. In recent years, California has broadened its CalWORKs goals to include program outcomes focused on long-term employment and family well-being, which do not always align with core WTW activities. However, as mentioned, the WPR requirements include potential financial penalties. While DSS and counties are required to collect and submit WPR-related data to the federal government regardless of where California’s WPR targets fall, the reduction credit rebase may lessen the pressure on the state and counties to meet higher WPR targets. In doing so, it may present an opportunity to shift some of the state’s focus towards other desired outcome measures or goals for the CalWORKs program

Goal of Increasing CalWORKs Take-Up May Impact WPR Requirements Long Term. In our recent analysis, we found roughly 60 percent of eligible families enroll in CalWORKs. State policymakers have undertaken efforts to increase this take-up rate, such as providing $2 million in the 2021‑22 Budget Act for a statewide media campaign to promote the CalWORKs program to potentially eligible populations. Considering the impacts future policy changes may have on the state’s WPR requirements may be important going forward.

MOE Funds and WINS

WINS Was Established With a Primary Goal of Boosting the State’s WPR. The program’s secondary goal is to provide additional benefits to working CalFresh families. As mentioned, starting in federal fiscal year 2025‑26, WINS would only help California meet its WPR requirements if monthly benefits were increased from $10 to $35.

WINS and Other Program Changes Likely Increased California’s WPR. In federal fiscal year 2013‑14, California had a failing all families WPR of approximately 30 percent. As mentioned, WINS was implemented in 2014. In the same year, California provided additional funding for subsidized employment, implemented family stabilization (a program intended to assist in-crisis CalWORKs recipients in removing barriers to WTW participation), and began excluding some CalWORKs cases without a work-eligible adult from the state’s WPR calculations. The next year, California’s all families WPR increased to 56 percent. California has continued to meet the 50 percent all families WPR requirement since 2014‑15.

California Likely to Meet One or Both WPR Requirements Regardless of WINS. Due to the caseload reduction credit rebase, California likely will meet one or both of its annual WPR targets in 2025‑26 (and potentially in multiple years thereafter) regardless of if WINS cases are included. Therefore, the Legislature could decide to eliminate WINS in 2025‑26 with some assurance that, at least over the next few years, doing so is unlikely to lead to federal financial penalties. However, if annual CalWORKs caseload increases, the state’s annual caseload reduction credits are likely to simultaneously decrease. This would push the state’s WPR requirements back up. Depending on how quickly and significantly caseload changes, California may face a future scenario where a program like WINS could again be helpful in ensuring the state can meet its WPR targets.

Legislature Might Consider Future Goals for WINS. The Legislature might begin considering if and how it plans to respond to the upcoming federal change impacting WINS in 2025‑26. For example, the state could continue to operate WINS as is, regardless of the upcoming change, by continuing to provide $10 monthly benefits. Alternatively, California could increase WINS monthly benefits in 2025‑26 to $35 to align with the new federal requirement, which would increase overall WINS costs by roughly $40 million annually. Finally, the Legislature could eliminate WINS altogether beginning in 2025‑26, generating about $25 million in annual General Fund savings.

Recommend Weighing Trade-Offs of Eliminating, Maintaining, or Expanding WINS. In light of the significant budget deficits expected in the future, the Legislature might begin considering how it will weigh the estimated cost of increasing WINS benefits to the new federally required minimum against the potential drawbacks of eliminating the program. Eliminating WINS would reduce monthly food benefits by $10 for about 125,000 households. We recommend the Legislature ask the administration for information on the impacts this reduction might have on overall benefit levels and food security amongst CalFresh families. Additionally, eliminating the program would mean that, in the future, if California struggles to meet the WPR, it would not have WINS as a tool to assist in meeting the requirements. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration how difficult it would be to re-start a WINS-like program in the future if WPR challenges arise once again.

Multistate Performance Measurement Pilot Program

Pilot Appears Aligned With Recent Legislative Interest in Expanding Goals of CalWORKs. As mentioned, California has broadened its CalWORKs goals in recent years to include a focus on long-term employment and family well-being. While additional details are needed on the pilot’s intended outcome measures, currently available information indicates some outcome measures already used to evaluate the CalWORKs program may be included in the pilot. California collects data on the percentage of work-eligible CalWORKs recipients employed approximately six months after program exit and these individuals’ earnings at six and 12 months post-exit, both of which have already been identified as intended pilot outcome measures. Cal-OAR also captures information on participating households’ stability and well-being, such as access to supportive services like child care, educational attainment, wage progression, and rate of program exits with earnings. More information on the well-being outcome measures to be used in the pilot will likely be available in spring 2024.

Administration in Favor of Participating in Pilot. In response to a legislative requirement to collect input from a workgroup of stakeholders on the emphasis of the WPR in CalWORKs, DSS held workgroup meetings between December 2022 and January 2023. DSS issued a report in September 2023 indicating the pilot could serve as an opportunity to temporarily protect against the financial penalties associated with WPR requirements while influencing nationwide development and utilization of more comprehensive performance measures aligned with California’s expanded goals for the CalWORKs program. County representatives also expressed interest in state pilot participation, indicating it could serve as an opportunity for county welfare departments to focus on performance metrics that better correspond with their local program goals. The Governor’s budget signaled the administration’s intent to apply for the pilot.

Recommend the Legislature Consider the Trade-Offs of Pilot Participation. If selected as a pilot participant, the state would have the opportunity to demonstrate whether alternative measurements might be more pertinent to measuring the success of state TANF programs. This could benefit California after the pilot ends if the federal government decides to change the TANF performance metrics for all states going forward. The pilot may also present an opportunity to shift some of the state’s focus towards other desired outcome measures or goals for the CalWORKs program. However, as mentioned, California is likely to face low WPR targets in 2025‑26 (and potentially in multiple years to follow) regardless of its participation in the pilot. These low targets could also provide opportunities for the state to focus on other outcome measures. We recommend the Legislature begin considering the potential trade-offs of pilot participation, such as the time and effort participating may entail versus the potential short- and long-term benefits for California. Potential state costs associated with pilot participation cannot be estimated at this time due to limited information, but are likely to become clearer as the federal Administration for Children and Families releases more information on the pilot requirements in spring 2024.

Work Outcomes Reporting Requirements

Cal-OAR Captures Most of the Data Needed for New Federal Reporting Requirements. Based on our understanding from the administration, Cal-OAR collects county-level data on job entry, job retention, and median earnings of CalWORKs participants after program exit. DSS indicated it plans to work with the California Department of Education to meet the reporting requirement on high school diploma attainment.

The Legislature Might Consider Requesting Annual Updates on State’s Performance. DSS is currently required to submit an annual report to the Legislature summarizing county performance on established Cal-OAR program measures and analyzing performance trends. However, DSS indicated in some cases, the way in which data is represented in Cal-OAR may differ slightly from federal reporting requirements. The Legislature might consider asking the administration to include in its annual report a summary of the state’s performance along any federal outcome measures (including the new reporting requirements) not captured in Cal-OAR.