March 19, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

CalFire—Implementation of a 66‑Hour Workweek

Summary

The Governor’s budget includes $199 million ($197 million from the General Fund) and 338 positions in fiscal year 2024‑25 to begin implementing a shift to a 66‑hour workweek as contemplated in a 2022 memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the union representing firefighters from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire). The costs of the proposal would increase in the coming years as CalFire phases in the changes, rising to $770 million ($756 million General Fund) on an ongoing annual basis and 2,457 permanent positions by 2028‑29.

Prioritizing firefighters’ health and welfare is a worthwhile goal, and pursuing this outcome through the concept of reducing firefighters’ workweek was a reasonable step for the Legislature to take when it approved the MOU in September 2022. However, both the cost of adopting a 66‑hour workweek and the extent of the state’s revenue shortfall still were unknown at that time. The magnitude of the proposal the administration has now presented to the Legislature shows that it would create a substantial new ongoing General Fund commitment. This proposal comes at a time when the state faces a large, ongoing budget problem. As such, the Legislature faces a key decision as to whether or not implementing the proposal is affordable given the state’s current fiscal condition.

If the Legislature is not certain that the General Fund can sustain the proposal right now, we recommend that it not move forward with funding the change as part of the 2024‑25 budget. Deferring implementation would provide the Legislature with greater flexibility in the future to determine its preferred course of action in light of potentially evolving budget conditions, while still sustaining its long‑term commitment to improving the health and wellness of the state’s firefighters. We also offer suggestions for interim, less costly steps the Legislature could consider taking to support firefighters if it were to delay implementation of the workweek change. If, however, the Legislature wants to prioritize General Fund for implementing this change beginning in 2024‑25, we recommend it add reporting language to help ensure that the proposal maximizes the potential for associated wildfire resilience‑related co‑benefits.

Background

CalFire’s Main Responsibilities

CalFire Has Responsibilities for Fire Response and Resource Management. CalFire has primary responsibility for wildland fire response in State Responsibility Areas, which are mostly privately owned wildlands that encompass about one‑third of the acreage of the state. The federal government is responsible for wildland fire response on federal lands. The balance of the state consists of both developed and relatively rural lands (generally not wildlands) for which fire response services are the responsibility of local jurisdictions. In some cases, local jurisdictions contract with CalFire to provide fire protection and other services on their behalf. In addition to its roles related to fire response, CalFire also has various responsibilities for the management and protection of the state’s forests.

Trends in Wildfires and CalFire’s Budget

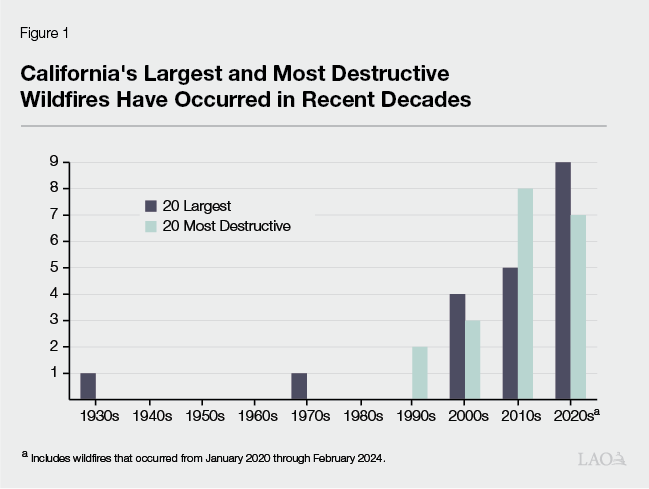

Major Wildfires Have Occurred Over the Past Several Years. As Figure 1 shows, most of California’s largest and most destructive wildfires have occurred in recent decades. This trend has been particularly notable in the last several years, which have seen some of the worst wildfires in the state’s recorded history. For example, the 2018 wildfire season included the Camp Fire in Butte County, which became the single most destructive wildfire in state history with nearly 19,000 structures destroyed and 85 fatalities, including the near‑total destruction of the town of Paradise. A few key factors have contributed to the recent increase in large and destructive wildfires, including climate change, poor forest and land management practices, and increased development in fire‑prone areas.

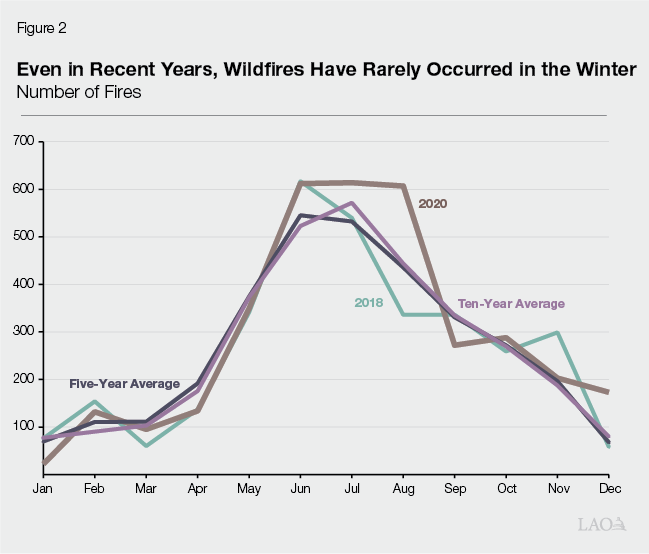

While Annual Wildfire Seasons Have Lengthened, Strong Seasonal Pattern Still Exists. Despite recent years having particularly large and destructive wildfires and concerns about wildfires becoming a year‑round phenomenon, the occurrence of wildfires in California continues to have a strongly seasonal pattern—primarily occurring during the summer and fall months when the weather is the driest Figure 2 shows the average number of wildfires by month across the last five years compared to the ten‑year average, along with the number of wildfires by month in the severe 2018 and 2020 wildfire seasons. As the figure shows, wildfire activity is relatively low from December through March and reaches its peak from June through August each year. While generally fewer wildfires occur in the fall (as compared to summer), these fires can be particularly severe because forests are dry after little to no rainfall during the summer, as well as due to other autumn weather conditions such as high winds.

Increase in Wildfires Has Led to Concerns About State’s Preparedness and Demands on Firefighters. Recent increases in large and severe wildfires have raised concerns about the state’s capacity to adequately respond to these growing threats, particularly when multiple large wildfires occur simultaneously as has happened in recent years. Responding to these large and severe wildfires has imposed significant burdens on firefighters—many of whom have been required to work long stretches without breaks. This, in turn, has led to concerns about the mental and physical health and wellness of the firefighters who are on the frontlines of these events. These issues have been highlighted in the media—such as in a series of articles published in 2022 by CalMatters.

Legislature Has Taken Various Actions to Respond to Concerns. The Legislature has taken a number of actions in response to these growing concerns, including to improve the health and wellness of firefighters. For example, in the 2020‑21 and 2022‑23 budgets, the Legislature approved proposals—totaling roughly $170 million per year on an ongoing basis—to provide relief staffing for CalFire. The main goal of these augmentations was to reduce the strain on firefighters by making it easier for them to take time off, such as for vacations and training activities. (We discuss these staffing expansions in further detail later in this brief.) Also, as part of the 2019‑20 budget, the Legislature approved a proposal that provided $9 million annually and 25 positions to augment various employee health and wellness programs at CalFire.

In recent years, the Legislature also has approved various increases in fire response capacity more broadly, such as adding new fire crews at CalFire and partner agencies and funding new helicopters and other aircraft. (We summarize many of these augmentations in our 2022 publications, The 2022‑23 Budget: Wildfire Response Proposals and The 2022‑23 California Spending Plan: Resources and Environmental Protection.) By augmenting fire response capacity, the state provided resources to enable CalFire to respond more quickly and forcefully to wildfires. This, in turn, was intended to help keep fires from growing and exacerbating, thereby avoiding placing more severe strains on firefighters. Finally, the state also has made unprecedented investments in improving forest and landscape conditions in recent years, including providing $2.8 billion from 2020‑21 through 2023‑24 as part of a series of budget packages, as well as authorizing the continuous appropriation of $200 million annually from cap‑and‑trade program revenues through 2028‑29 to support wildfire resilience activities. These investments—which we discuss in more detail in our February 2024 report, The 2024‑25 Budget: Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions—are aimed in large part at reducing the susceptibility of the state’s forests and landscapes to catastrophic wildfires, which should indirectly reduce the strains on firefighters.

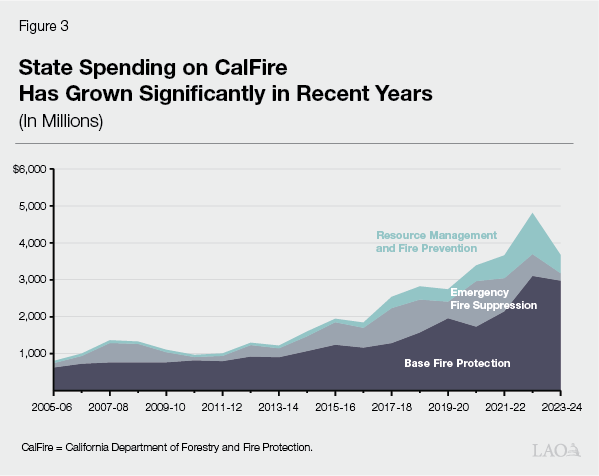

CalFire Budget and Staffing Have Increased Substantially in Recent Years. Driven by augmentations such as those discussed above, we estimate that CalFire’s total base wildfire protection budget has nearly tripled over the past ten years (from $1.1 billion in 2014‑15 to $3 billion in 2023‑24). As shown in Figure 3, CalFire’s overall budget also has increased, with its combined budget for fire protection, emergency fire suppression, and resource management and fire prevention more than doubling over the past ten years (from $1.7 billion in 2014‑15 to $3.7 billion in 2023‑24). Correspondingly, CalFire’s staffing levels also have increased significantly over the past decade. Specifically, between 2014‑15 and 2023‑24, the number of positions that CalFire categorizes as related to fire protection increased from 5,756 to 10,275, and the total number of positions at the department grew from 6,632 to 12,000 (representing roughly an 80 percent increase in both cases).

Current Structure of CalFire’s Workweek, Staffing, and Operational Models

CalFire’s current workweek, staffing, and operational models are dictated in large part by the department’s service needs, which include providing 24‑hours per day, 7‑days per week coverage on a year‑round basis, as well as augmented response capacity during peak wildfire season. We discuss these current structures in further detail below.

CalFire Currently Operates on a 72‑Hour Workweek. CalFire firefighters have a different work schedule than most other state employees. To facilitate providing round‑the‑clock coverage, firefighters typically work—on average—four 72‑hour workweeks in a 28‑consecutive‑day cycle. A 72‑hour workweek typically consists of three consecutive 24‑hour days (during which firefighters usually sleep at the station), followed by four days off.

Under Current Workweek, Firefighters Receive Significant Compensation From Both Scheduled and Unplanned Overtime. CalFire employees working a 72‑hour workweek receive overtime pay for all hours worked in excess of 212 hours during the 28‑consecutive‑day workperiod. (Pursuant to federal law, 212 hours is the maximum number of work hours allowed during a 28‑consecutive‑day period before overtime must be paid.) This compensation structure results in 19 hours in a typical workweek (or 76 hours in a 28‑day pay period) being paid at 1.5 times an employee’s hourly rate for scheduled overtime, referred to as Extended Duty Week Compensation. We estimate that scheduled overtime makes up roughly one‑third of the total base pay for most common firefighter classifications. For example, the salary range for an entry‑level, seasonal Firefighter I position is roughly $3,700 to $4,600 per month, plus an additional $1,800 to $2,300 in scheduled overtime.

Employees receive additional pay for unplanned overtime for any time worked in excess of 72 hours in a workweek, which also is paid at 1.5 times an employee’s hourly rate. Unplanned overtime is used to backfill staff that take vacations or engage in training exercises, as well as to engage in certain emergency response activities.

CalFire Generally Uses a 3.11 Staffing Factor for Permanent Firefighters. To provide round‑the‑clock coverage and allow each firefighter to take four days off per week, CalFire must hire more than one person to cover each fire response position (referred to as a “post”). Historically, CalFire used a staffing factor of 2.33, meaning the department would hire 2.33 firefighters for each post position in order to provide coverage seven days per week. As a result of the recent relief staffing augmentations mentioned above, CalFire currently is in the process of moving towards a new standard staffing factor of 3.11 for most post positions. Under this new staffing factor, the department would hire 3.11 firefighters for each post to provide coverage seven days per week as well as for when firefighters take time off (such as for vacations, sick leave, or training). CalFire fire engines generally are staffed with three personnel at all times. Since each of these positions is considered a post that must be covered, it would take 9.33 personnel to staff each engine if a 3.11 staffing factor were applied to each of the positions.

CalFire’s Current Staffing and Operational Models Have Various Other Key Features. Besides the workweek and staffing factors, other important features of CalFire’s current staffing and operational models include the following:

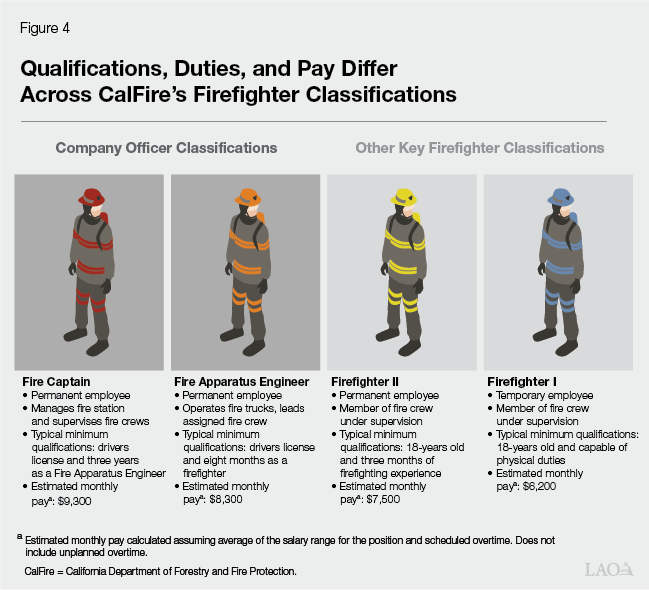

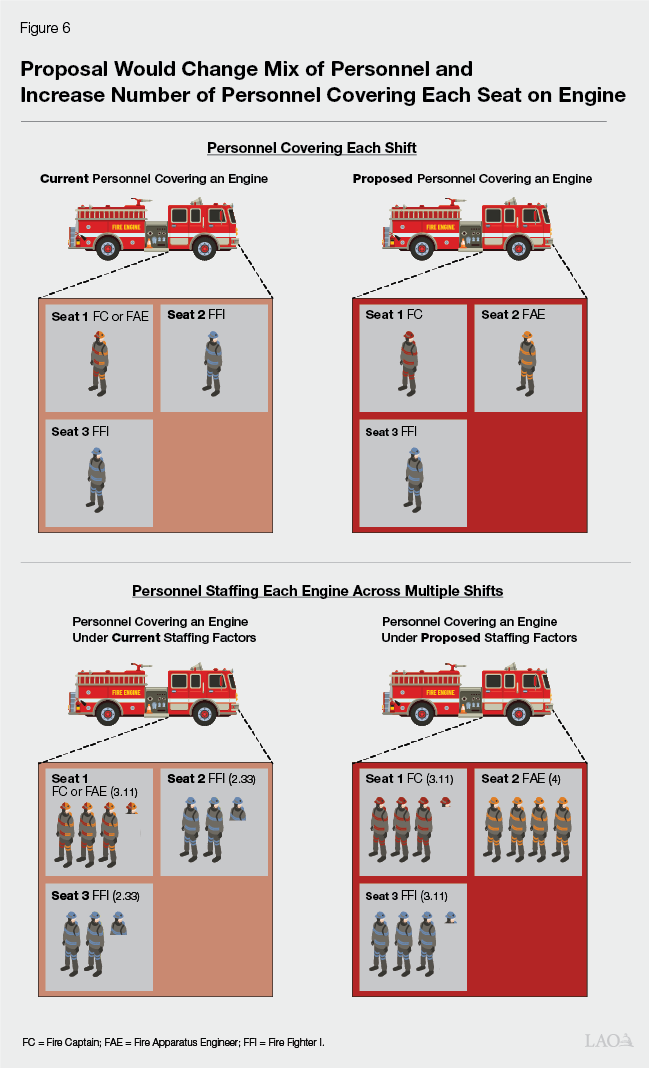

- Engines Currently Staffed With Mix of Classifications, Including Temporary Staff. As mentioned above, CalFire’s fire engines generally are staffed with three personnel at all times. At least one of these three personnel is required to be a Fire Captain or Fire Apparatus Engineer (positions referred to as “company officers”). For example, a fire engine may be staffed with a Fire Captain and two Fire Fighter Is or a Fire Apparatus Engineer and two Fire Fighter Is. As we display in Figure 4, these personnel have different qualifications and duties. For instance, a seasonal Fire Fighter I has relatively few professional prerequisites. In contrast, attaining the rank of Fire Captain requires significant firefighting experience, including serving for roughly three years as a Fire Apparatus Engineer. Additionally, the various classifications also carry notable differences in pay and benefits—we estimate that Fire Captains earn roughly 50 percent more per month than Fire Fighter Is and Fire Apparatus Engineers earn roughly one‑third more per month than Fire Fighter Is. (Fire Fighter Is also are less costly for CalFire to employ because they work a maximum of nine months per year rather than year round.)

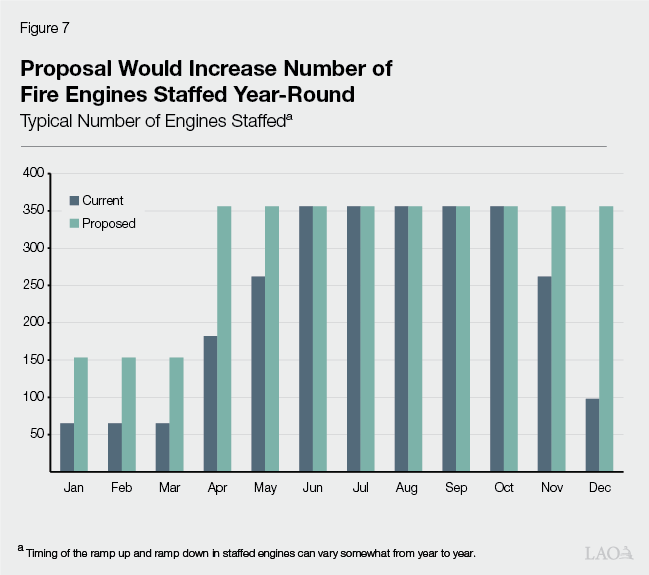

- CalFire Operates Three Staffing Periods. Currently, CalFire operates three staffing periods—base, transitional, and peak. The number of fire engines, air attack bases, and helitack bases that the department activates varies across these three periods based on projected fire risk. For example, during peak season—which typically extends from roughly June through early October—CalFire operates 356 fire engines, 12 air bases, and 10 helitack bases. In contrast, during the base staffing period—which typically extends from roughly December through March—CalFire operates 65 engines and no aerial resources. Between the base and peak periods, CalFire operates what it refers to as a transitional staffing period. During these times of year, the number of fire engines and aerial resources are ramped up and ramped down. (We display the number of fire engines that CalFire typically operates each month in Figure 7 of this brief.)

- CalFire Currently Rotates Personnel Individually Rather Than as a Group. Currently, CalFire firefighters rotate on and off of their shifts individually rather than together as a group “platoon.” For example, on a given fire engine, one firefighter may work Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday; whereas another will work Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday; and a third will work Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. For this reason, the same team of firefighters typically does not staff a fire engine together for more than one or two days a week.

Unit 8 and Recent MOU

Unit 8 Represents Most CalFire Personnel. Under state law, state employees regularly undertake collective bargaining with the Governor (as represented by the California Department of Human Resources) over their compensation. State workers (except managers and certain others) are organized into 21 bargaining units and represented by unions. The product of the collective bargaining process is an MOU, which specifies the terms and conditions of employment. To take effect, MOUs must be ratified by union members and the Legislature. Unit 8 (CalFire Local 2881) represents most of CalFire’s positions, such as Fire Captains, Fire Apparatus Engineers, Fire Fighter IIs, and Fire Fighter Is. (CalFire’s positions that are not covered by Unit 8 mostly consist of its administrative and support positions, such as Associate Governmental Program Analysts and Office Technicians.)

Legislature Approved Current Unit 8 MOU in September 2022. The Legislature approved the most recent MOU with Unit 8 in September 2022 with the passage of Chapter 250 of 2022 (AB 151, Committee on Budget). This MOU is in effect through June 2024. A successor agreement likely will be submitted to the Legislature for ratification in the coming months, although the precise timing is not yet known. As we discussed in our August 2022 analysis of the Unit 8 MOU, the agreement included various provisions such as providing a 6.6 percent general pay increase over two years, adding additional pay for employees with long tenures and certain education qualifications, increasing reimbursements for transit and vanpools, and changing the workweek, as discussed further below.

Unit 8 MOU Included 66‑Hour Workweek Provision—Contingent on a State Budget Appropriation. Under the agreement, the state and union agreed to reduce the CalFire firefighter workweek from 72 hours to 66 hours—a 24‑hour reduction per 28‑day pay period. The MOU set this change to take effect on November 1, 2024—notably, after the expiration date of the agreement—and subject to an appropriation in the 2024‑25 budget. The agreement required that a joint labor management committee be established to determine the changes needed to implement the reduction, including hours of work, shift patterns, retention and recruitment, and classifications. The agreement further required the committee to present to the Director of the Department of Finance a mutual agreement by July 1, 2023, to be included in the Governor’s budget proposal in January 2024. Notably, the MOU specified that if the Governor declares a fiscal emergency and General Fund monies over the 2024‑25 Governor’s budget’s multiyear forecasts are not available to support the reduction to a 66‑hour workweek on an ongoing basis (including the estimated direct costs and any increases in the cost of overtime driven by the proposal), the parties agreed to reopen the provision regarding how and when to implement the workweek reduction.

Governor Intends to Declare Fiscal Emergency and General Fund Is Facing Very Large Out‑Year Deficits. Due to a deteriorating revenue picture relative to expectations, both our office and the administration anticipate that the state faces a significant budget problem. Specifically, in January our office estimated that the Governor’s budget addressed a $58 billion problem. More recent fiscal data we summarize in our February publication, The 2024‑25 Budget: Deficit Update, indicate the budget outlook continues to worsen. We now estimate the state has a $73 billion deficit to address with the 2024‑25 budget. To address the budget problem, the Governor proposes a combination of actions including spending reductions, fund shifts, delays, reserve withdrawals, cost shifts, and revenue increases. Notably, while the Governor has not yet declared a formal budget emergency, the structure of the proposed solutions assumes that a declaration will be forthcoming in the next few months. Specifically, the proposed withdrawals from reserve accounts—a key part of the Governor’s budget balancing plan—are only allowable with a budget emergency declaration. Moreover, in addition to the immediate budget problem facing the state, both our office and the administration estimate that based on current revenue forecasts, the state will face significant structural operating shortfalls—at least $30 billion annually—from 2025‑26 through 2027‑28.

Governor’s Proposal

Includes Roughly $200 Million—Growing to Over $750 Million Ongoing—From the General Fund to Implement a 66‑Hour Workweek. The Governor’s budget includes $199 million ($197 million from the General Fund) and 338 positions in fiscal year 2024‑25 to begin implementing a shift to a 66‑hour workweek as contemplated in the 2022 MOU with Unit 8. The costs of the proposal would increase in the coming years as CalFire phases in the changes, rising to $770 million ($756 million from the General Fund) on an ongoing annual basis and 2,457 permanent positions by 2028‑29. As shown in Figure 5, these costs include (1) salaries and benefits for adding new firefighter and other wildfire response‑related positions; (2) salaries and benefits for adding new support staff, including administrative personnel and maintenance staff; (3) additional overtime (including both scheduled and unplanned) for firefighters and other wildfire response‑related classifications; (4) 235 new vehicles, as well as costs for vehicle leases, maintenance, radios, and equipment; (5) various augmented aerial support‑related contracts, such as for contracted pilots and mechanics at airbases; (6) one‑time special repair funding to address maintenance needs at CalFire facilities; (7) training center costs; and (8) proportional funding for contract counties.

Figure 5

Summary of 66‑Hour Workweek Funding Proposal

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

Ongoing |

||||

|

Positions |

Amount |

Positions |

Amount |

||

|

Salaries and Wages |

338 |

$28.3 |

2,457 |

$191.9 |

|

|

Fire Response Positions |

231 |

$19.5 |

2,075 |

$162.1 |

|

|

Fire Apparatus Engineer |

104 |

7.6 |

1,352 |

98.7 |

|

|

Fire Captain |

105 |

8.6 |

594 |

48.7 |

|

|

Battalion Chief |

10 |

0.9 |

59 |

5.5 |

|

|

Heavy Fire Equipment Operator |

10 |

0.8 |

40 |

3.3 |

|

|

Assistant Chief |

6 |

1.1 |

24 |

4.3 |

|

|

Forestry Fire Pilot |

5 |

0.6 |

15 |

1.7 |

|

|

Aviation Officer III |

5 |

0.7 |

5 |

0.7 |

|

|

Reduction of Firefighter I Costs |

‑14 |

‑0.8 |

‑14 |

‑0.8 |

|

|

Support Positions |

107 |

$8.8 |

382 |

$29.8 |

|

|

Associate Governmental Program Analyst |

56 |

4.2 |

302 |

22.7 |

|

|

Staff Services Manager I |

5 |

0.4 |

34 |

3.0 |

|

|

Heavy Equipment Mechanics |

25 |

2.0 |

25 |

2.0 |

|

|

Direct Construction Supervisor I |

21 |

2.1 |

21 |

2.1 |

|

|

Overtime |

— |

$13.9 |

— |

$122.3 |

|

|

Scheduled Overtime |

— |

9.5 |

— |

83.6 |

|

|

Unplanned Overtime |

— |

4.4 |

— |

38.8 |

|

|

Staff Benefits |

— |

$28.4 |

— |

$206.4 |

|

|

Operating Expenses and Equipment |

— |

$20.0 |

— |

$125.8 |

|

|

Contracts for Aircraft Staffing and Maintenance |

— |

$15.1 |

— |

$15.1 |

|

|

Vehicles Purchases, Leases, and Repair |

— |

$48.5 |

— |

$14.8 |

|

|

Training Center Costs |

— |

$33.2 |

— |

$7.7 |

|

|

Special Repairs |

— |

$5.3 |

— |

— |

|

|

Contract County Proportional Share |

— |

$6.3 |

— |

$86.4 |

|

|

Totals |

338 |

$198.9a |

2,457 |

$770.4b |

|

|

a$197 million from the General Fund and $2 million from reimbursements and various special funds. b$756 million from the General Fund and $14 million from reimbursements and various special funds. |

|||||

Assessment

Addressing Firefighter Fatigue and Welfare Is a Worthwhile Goal

Workweek Change Aims to Address Legitimate Concerns About Firefighter Welfare. The state has experienced some of the most severe wildfire seasons in its history in recent years. As discussed previously, these wildfires have placed significant strains on the state’s firefighters, many of whom have been asked to work for extended periods with few breaks. These long periods of work have been difficult for firefighters as well as for their families. By switching from a 72‑hour workweek to a 66‑hour workweek, the typical schedule for a firefighter would include roughly one fewer 24‑hour shift per month than is currently the case. This, in turn, could provide some additional time off for firefighters, thus helping to address the legitimate concerns about fatigue that have resulted from these recent wildfire seasons. In adopting the Unit 8 MOU, along with the various other actions it has taken in recent years to address concerns about the health and wellness of firefighters, the Legislature has demonstrated that it prioritizes this issue.

Legislature Faces Decision About Whether Proposal Is Affordable

Prioritizing firefighters’ health and welfare through the concept of reducing their workweek was a reasonable step for the Legislature to take in September 2022. However, at the time that the Legislature approved the current Unit 8 MOU, both the cost of adopting a 66‑hour workweek and the extent of the state’s revenue shortfall still were unknown. The magnitude of the proposal the administration has now presented to the Legislature shows that it would create a substantial new ongoing General Fund commitment. This proposal comes at a time when the state faces a large, ongoing budget problem. As such, the Legislature faces a key decision as to whether or not implementing the change in the workweek is affordable given the state’s current fiscal condition. We discuss these issues in further detail below.

Legislature Did Not Have Information About Cost Implications When It Considered MOU. When the administration submits an MOU to the Legislature for consideration, it typically prepares an estimate of the associated costs. In the case of the Unit 8 MOU, however, the administration’s cost estimate did not include the costs of the 66‑hour workweek provision for a couple of reasons. First, the workweek change would not be implemented until after the expiration of the MOU and the administration’s estimate only included costs for activities occurring during the term of the MOU. Second, the joint labor management committee was given relatively broad discretion regarding how to structure implementation of the new provision, but the committee was not even formed until after the MOU was ratified. These factors precluded the Legislature from having detailed information about the ultimate costs of implementing the 66‑hour workweek change when it considered the MOU. Notably, at the time our office analyzed the MOU, we estimated that the 66‑hour workweek provision likely would be costly for the state. However, we were only able to provide a broad sense of the potential costs—which we stated were likely to be in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars annually—given the uncertainty regarding how the provision ultimately would be effectuated.

Structure of MOU Workweek Provision Is Unique. The provision of the Unit 8 MOU that establishes a 66‑hour workweek differs from how policy changes typically are handled through the collective bargaining process in a few notable ways. First, the provision establishes a large policy change that affects how the state compensates its employees and how the state combats wildfires with minimal detail and significant deference to the joint labor management committee process. Second, the provision has very large fiscal effects that are not incurred until after the labor agreement has expired, making it impossible to know the full fiscal effect of the current MOU at the time of legislative ratification. Third, as we discuss in more detail below, the provision specifies that implementation of the policy change is subject to legislative appropriation in the 2024‑25 budget—an explicit acknowledgment of the Legislature’s budget authority and its ability to revisit, modify, or reject the policy in the future. None of these three characteristics are standard of a typical MOU provision.

Costs of Workweek Change Turning Out to Be Very High. The cost of the administration’s proposed approach to effectuating the 66‑hour workweek change is substantial—$770 million ($756 million from the General Fund) when fully implemented. This proposal would result in a roughly 20 percent increase in CalFire’s budget and staffing levels compared to 2023‑24. (As mentioned previously, total funding and staffing in 2023‑24 already reflect significant increases compared to historical levels.) As noted, only limited information was available on the details and implications of the 66‑hour workweek when the Legislature approved the MOU, so it may not have expected the associated costs to be this high. The 66‑hour workweek change also could create cost pressures for the state that are not reflected in the proposal. Most notably, by significantly increasing the number of firefighters the state employs, the proposal would contribute to the need to build a new CalFire training center, which is estimated to cost roughly $420 million.

Fiscal Conditions Have Deteriorated Since the Legislature Considered the MOU. When the Legislature considered the Unit 8 MOU in September 2022, the state’s fiscal condition and outlook looked significantly better than they do currently. Specifically, around the time the 2022‑23 budget was enacted, both our office and the administration anticipated the state’s budget would be roughly balanced over the coming years. Since that time, revenue projections have declined precipitously. For example, the administration’s revenue forecasts for 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 are more than $70 billion lower than they were in June 2022—and our office’s projections are even worse. This revenue erosion has resulted in significant projected deficits both in the budget year and out‑years, as discussed previously.

Legislature Maintains Flexibility Over Implementing MOU Based on State’s Funding Capacity. The provisions of MOUs are always subject to appropriation, as the Legislature has the fundamental constitutional “power of the purse.” However, as referenced above, MOUs typically do not include language explicitly declaring this to be the case. The fact that the Unit 8 MOU explicitly mentions this condition seemed to emphasize that the Legislature might need to weigh the capacity of the General Fund to support the costs of the change beginning in 2024‑25. Also, regardless of the intent of the language in the MOU, no particular Legislature may “bind the hands” of a future Legislature by requiring a future appropriation. As such, even though it approved the Unit 8 MOU, the Legislature still has flexibility around whether to provide funding to implement this proposal—as with any other proposal the committee and administration might put forward.

Governor Is Inconsistent in Pulling Back Some Commitments While Retaining 66‑Hour Workweek Change. The administration putting forth this workweek proposal despite the budget shortfall—and thereby deferring to the Legislature to decide whether the General Fund can sustain the associated costs—deviates from its approach to various other state commitments. Notably, in light of recent deteriorations in the condition of the General Fund, the Governor is proposing to pull back numerous other commitments that the state made in recent years. For example, the Governor is proposing to eliminate the existing telework stipends that have been provided to many state employees—even though these stipends also were agreed upon in negotiations with numerous bargaining units—to save a much smaller amount than the cost of the 66‑hour workweek proposal ($26 million General Fund annually). Additionally, the Governor is proposing various budget solutions in the climate, resources, and environmental areas—including reductions, delays, and fund shifts—to achieve $4.1 billion in savings to address the 2024‑25 budget problem. These proposals would pull back multiple funding commitments that were made over the past few years, including reducing well over $1 billion in funding that has already been appropriated. (We discuss these proposed solutions in greater detail in our February 2024 report, The 2024‑25 Budget: Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions.) Given the condition of the General Fund, we think it is both reasonable and necessary for the Legislature to revisit all its previous budget commitments—including those the Governor proposes revising and those he would leave intact—to determine whether they still are among its highest priorities for available funding.

Withholding Approval of Funding in 2024‑25 Could Have Some Notable Advantages

There are a few reasons why it could be beneficial to the Legislature to withhold its approval of funding to implement the workweek proposal in 2024‑25, as we discuss further below.

Withholding Approval Would Preserve Legislative Flexibility to Revisit Approach. As discussed previously, the MOU includes language allowing for the reopening of when and how to implement the change in the workweek through future collective bargaining negotiations if the Governor declares a budget emergency and the General Fund cannot sustain the costs. However, in practice, if the Legislature chooses to appropriate the proposed funds to implement the change as part of the 2024‑25 budget, delaying implementation through the collective bargaining process likely will be difficult and result in some other concessions to affected employees that would increase state costs. Deferring to the collective bargaining process for adjusting the workweek provision also would constrain the Legislature’s role in being able to shape any potential modifications, since its only involvement with MOU agreements is a “yes” or “no” vote on ratification. In contrast, if the Legislature were to defer approving funding for implementing the 66‑hour workweek, it would give the parties the opportunity to reopen discussions on that provision as part of the upcoming negotiation process, such as to consider an alternative implementation time line or put forward alternative and less costly options to address firefighter welfare. It also would give the Legislature the opportunity to independently explore whether it would like to implement other approaches to addressing its concerns about firefighter health and wellness instead of the workweek change. Accordingly, not funding the workweek proposal in 2024‑25 is among the only effective avenues available to the Legislature if it wants to maximize its authority and flexibility to consider alternative approaches.

Withholding Approval Would Allow Legislature to Adjust to Future Budget Conditions. The flexibility provided by not approving the proposal in 2024‑25 would allow the Legislature to revisit the choice regarding whether to implement the 66‑hour workweek change in a future year when the General Fund has greater capacity, including potentially with modifications as needed or desired. In contrast, if the Legislature approves the proposal now and the budget condition does not improve, it may be in a position of having to make even steeper cuts to other activities (or raising taxes by an even larger amount) to sustain this new funding commitment in the out‑years while facing multibillion‑dollar annual deficits.

Withholding Approval Would Enable Revised MOU to Incorporate Various Details That Have Yet to Be Bargained. Withholding approval of funding for the 66‑hour workweek also would give the collective bargaining process more opportunity to work out specific details of the policy so that the Legislature and public can be more aware of the totality of the proposal and the details can be fully incorporated into a revised MOU. For example, the current MOU does not incorporate any changes to the number of hours firefighters would be paid for scheduled overtime, despite the fact that firefighters would be working fewer hours under the proposal. If a revised MOU were to come back to the Legislature for consideration in a future year, the negotiating parties could consider whether overtime pay policies for firefighters also should be adjusted in tandem with the workweek change.

Proposal Has Large Operational and Other Impacts

The main intent of the proposal is to change the CalFire workweek from 72 hours to 66 hours. However, as we discuss further below, it goes well beyond just hiring proportionately more personnel to implement this change. Instead, the Governor also proposes making various changes to CalFire’s staffing and operational models—with significant associated costs. Additionally, the proposal also has potential indirect impacts on both CalFire and other partner agencies, such as local governments, which are not fully understood at this time.

Administration’s Proposed Approach Driven by Goal of Addressing Imbalance in Ratio of Positions and Increasing Staff Development Pipeline. The administration argues that it cannot reduce the workweek simply by adding proportionately more firefighting staff. Instead, in addition to hiring additional firefighters overall, the administration also proposes to modify various other aspects of CalFire’s staffing model to address a current problem with its staff development pipeline. Specifically, the proposal makes two key changes—discussed below—with the primary intention of increasing both the number and proportion of Fire Apparatus Engineers the department employs. The administration’s primary rationale for these changes is a concern that it would struggle to hire a sufficient number of Fire Captains to implement the workweek change if the department were to continue with its current staffing model. As shown earlier in Figure 4, working for at least three years as a Fire Apparatus Engineer is a prerequisite for being eligible to be hired for a Fire Captain position. Under CalFire’s current engine staffing model, the department employs roughly three Fire Captains for every two Fire Apparatus Engineers. According to the administration, this imbalance has resulted in an inadequate pipeline of qualified staff to fill Fire Captain positions. The administration believes that adding large numbers of additional firefighters to reduce the workweek without changing the current staffing model would exacerbate this imbalance and result in an unworkable shortage of Fire Captains.

Proposed Approach Would Greatly Increase Share of Experienced, Year‑Round Staff, Resulting in Higher Costs. The administration proposes to create a larger pipeline to Fire Captain positions by creating far more Fire Apparatus Engineer positions than would otherwise be necessary. Specifically, the administration proposes two actions that together have the effect of significantly increasing the number of Fire Apparatus Engineer positions relative to other firefighter classifications, both of which have notable cost implications:

- Increases Share of Seats on Engines Filled by More Experienced, Year‑Round Fire Apparatus Engineers. As shown in Figure 6, under the proposal, CalFire would use Fire Apparatus Engineers to fill many of the posts that currently are filled by entry‑level, seasonal Fire Fighter Is. For example, an engine that currently is staffed at any given time with a Fire Captain and two Fire Fighter Is might instead be staffed by a Fire Captain, Fire Apparatus Engineer, and Fire Fighter I.

- Increases Number of Positions Hired to Cover Each Fire Apparatus Engineer Seat on an Engine. In addition to changing the staffing mix on an engine during a particular shift, the proposal also would change the number of Fire Apparatus Engineers CalFire hires to cover an engine across multiple shifts. (As discussed earlier, the number of positions hired to cover a particular post across multiple shifts is referred to as a staffing factor.) This proposed change also is illustrated in Figure 6. Specifically, under the proposal, four people would be employed to cover each Fire Apparatus Engineer post rather than 3.11, as is the current policy. (As displayed, the proposal also would increase the current staffing factor for Fire Fighter I positions from 2.33 to 3.11.)

The net result of these changes is that the proposal not only increases overall CalFire staffing levels by roughly 20 percent but also makes very significant changes to the mix of personnel employed by the department. Notably, the proposal would roughly double the number of Fire Apparatus Engineers employed by the department, while decreasing the number of Fire Fighter I positions. This, in turn, has very large fiscal implications because Fire Apparatus Engineers are much more costly for the department compared to Fire Fighter Is, both because their pay and benefits are more substantial and because they work more months per year.

Approach Has Various Cascading Impacts on CalFire’s Operational Model. The addition of over 2,000 new firefighters combined with the shift towards a much higher share of firefighters being more experienced year‑round staff would have notable operational implications for CalFire, including the following:

- Would Increase the Number of Fire Engines Staffed Year‑Round. The expanded ranks and higher share of permanent (rather than seasonal) firefighters would allow CalFire to modify when it staffs its fire engines. Specifically, instead of its current model of three staffing periods—base, transitional, and peak, as discussed earlier—CalFire would move to two staffing periods—base and peak—as shown in Figure 7. Also, the peak staffing period would be extended to nine months rather than five months. Furthermore, the number of fire engines that would be staffed during the base period would more than double—153 versus 65.

- Would Adopt a Platoon Staffing Model. In addition to moving the department towards greater year‑round staffing of engines, the additional permanent personnel would allow CalFire to adjust its staffing rotation to a platoon model (subject to further bargaining with Unit 8). Under this approach, firefighters would rotate on and off duty together as a group rather than individually. For example, an engine might be staffed by a team made up of a Fire Captain, Fire Apparatus Engineer, and Fire Fighter I on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday; a separate trio of individuals on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday; and a third group on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Notably, under this model, some days would have overlapping groups of two teams working on the same day.

Proposed Changes Could Have Indirect Impacts on Other Agencies. In addition to the direct impacts on CalFire operations, the workweek change could potentially have indirect impacts on CalFire and other partner agencies, many of which may not be fully understood yet. For example, currently, many local agencies have contracts with CalFire to provide local fire protection and emergency services. If the proposal is approved, we expect these agreements ultimately may need to be modified to reflect that (1) more personnel will be needed to fill each seat on a fire engine because of the higher staffing factors and (2) each fire engine will be staffed with a mix of relatively more costly personnel than is currently the case. These changes could result in higher costs for these local agencies and potentially make it less advantageous for some of them to contract with CalFire for services.

Legislature Could Explore Other Options

As we discussed previously, addressing the welfare of firefighters is a worthwhile goal. However, particularly given the state’s fiscal condition, the Legislature could consider other ways to address this underlying concern as an alternative to changing the workweek. Furthermore, even if the Legislature wants to proceed with implementing a 66‑hour workweek, it could consider modifying the approach proposed by the administration.

Degree to Which Proposal Will Address Concerns About Firefighter Wellness Is Unclear. At a high level, the administration’s proposal to reduce the workweek would result in the state hiring many more firefighters and each firefighter working the equivalent of one fewer 24‑hour shift per 28‑day pay period. This has the potential to improve conditions for firefighters since they will receive some extra time off relative to their current schedules. Also, because the proposal would result in higher overall staffing levels at CalFire, it could increase firefighting capacity and thus somewhat reduce the amount of overtime any individual firefighter might be asked to work. However, the extent to which the change would improve firefighters’ overall health and wellness is uncertain. This is in part because—as discussed in the nearby box—the nature of the health and wellness challenges facing firefighters is not fully understood, and thus the most effective strategies for addressing these issues are not particularly clear. Additionally, the proposal would not affect many of the underlying challenges associated with being a firefighter. Specifically, under this proposal, firefighters still would have to deal with the various inherent strains of the job, including doing physically and emotionally strenuous work. Moreover, even with a shorter workweek firefighters still would be expected to work regular 72‑hour shifts and still would have to be available to serve potentially much longer periods during severe wildfire events.

Lack of Clarity Regarding Nature of Problem With Firefighter Welfare

A general recognition exists that the health and wellness of firefighters is a concern—particularly in light of recent severe and destructive wildfire seasons. However, the scope of the issues facing the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s (CalFire’s) firefighters still is unclear, as data on key metrics such as the incidence of post‑traumatic stress disorder, other mental health issues, and suicides are limited. Additionally, despite the increasing concerns about the health and wellness of firefighters, CalFire reports that its employee retention rates have remained largely stable over time and firefighting positions appear to continue to be very attractive to new employees. To date, CalFire has not provided evidence that it has faced challenges attracting firefighters to work at the department. For example, CalFire reports that it currently has three times more applicants for entry‑level Fire Fighter Is than available positions, suggesting that health and wellness concerns are not dissuading people from pursuing this profession.

Most Cost‑Effective Way to Address These Firefighter Wellness Concerns Is Unclear. Given the lack of clarity around the strains affecting firefighters and the best ways to address them, the Legislature could consider alternatives besides changing the workweek. For example, the Legislature could expand the existing health and wellness programs at CalFire to ensure that firefighters have access to robust support for mental and physical health concerns. Other changes the Legislature could explore include implementing policies that prohibit firefighters from working more than a certain number of days in a row (potentially paired with expansions in the use of mutual aid with partner agencies to offset potential losses in fire response capacity) or decrease the number of hours worked in the offseason (such as through reducing or eliminating planned offseason overtime, as was done prior to a change that occurred in 2006‑07). Additionally, the Legislature could consider using some of the funding that would be required to implement the 66‑hour workweek change to instead support efforts to improve conditions in the state’s forests. Such investments potentially could provide long‑term benefits to firefighters—as well as to the environment and surrounding communities—by reducing the likelihood of the severe wildfires that create the most significant strains on firefighters. Each of these actions would involve trade‑offs, but they remain available options for the Legislature to explore if desired.

Other Ways to Implement a 66‑Hour Workweek. The administration indicates that it does not believe any other viable approaches to reducing the workweek exist apart from the one it presents in its proposal. However, if the Legislature wants to move forward with implementing a 66‑hour workweek in accordance with the MOU, we have identified a number of other approaches for doing so—although none is without trade‑offs. For example, the Legislature could consider:

- Reducing Relief Staffing. The Legislature could consider reducing the workweek at least in part by dropping the engine staffing factor back to 2.33 (the level prior to the changes approved in 2020‑21 and 2022‑23). Under this approach, the additional personnel that CalFire currently is in the process of hiring to implement a 3.11 staffing factor could instead be used to provide coverage for a reduction in the workweek. This could allow the department to shorten the workweek without adding such significant new costs. A major drawback to this approach is that maintaining a lower staffing factor would deny firefighters the benefit of additional capacity to cover time off for vacations, training, and other activities. It also could potentially result in some additional overtime compared to current plans.

- Increasing Scheduled Overtime. The Legislature could consider using scheduled overtime to meet at least some of the reduced workweek hours. If the reduced workweek hours were covered entirely through scheduled overtime, this would essentially result in firefighters working a similar amount as they currently do, but shifting some of those hours to be classified as overtime. Such an approach likely would have the effect of increasing the net compensation for firefighters—and therefore state costs—but we expect that the overall costs would be less than the Governor’s workweek proposal. A major drawback to this approach is that even though it might increase firefighter compensation, it would not reduce their total work hours to the same degree, and thus might not provide the desired health and wellness benefits.

- Addressing the Fire Captain Shortage Through Other Approaches. The Legislature could consider adding firefighters to implement the 66‑hour workweek but taking other, less expensive actions to address the Fire Captain imbalance. As noted above, many of the administration’s proposed changes—and associated costs—result from increasing the number of Fire Apparatus Engineers to encourage a bigger development pipeline for Fire Captains. The Legislature could instead adjust CalFire’s existing classification requirements, or create a new classification. For example, the Legislature could look into creating a Lieutenant classification as a rank between Fire Captain and Fire Apparatus Engineer, which could enable Fire Apparatus Engineers to promote more quickly. This, in turn, would mean that fewer Fire Apparatus Engineer positions would be necessary to create an adequate staff development pipeline for higher‑level positions. The Legislature also could direct CalFire to try to recruit Fire Captains from other agencies. Even if this required increasing the Fire Captain salary to make it more attractive, such an approach could potentially be less expensive than significantly expanding the number of Fire Apparatus Engineers beyond what is necessary to effectuate the workweek change.

If the Legislature Approves Proposal, Important to Maximize the Benefits

Given the important goals—and very large costs—of the Governor’s 66‑hour workweek proposal, if the Legislature moves forward with approving it, ensuring that the change provides as much value as possible to the state will be important. Below, we discuss how the Legislature can facilitate this objective through requiring additional tracking and reporting.

Proposal Has the Potential to Improve Wildfire Resilience, but Actual Benefits Will Depend Upon Implementation… The administration’s proposed approach to decreasing the workweek to 66 hours would result in the state hiring over 2,000 additional permanent firefighters upon full implementation. These firefighters would work on a year‑round basis even during months when relatively few wildfires occur. In principle, when not fighting fires, these personnel should be available to perform other priority activities, such as thinning forests and conducting prescribed burns to improve the resilience of the state’s forests. Importantly, however, the level of wildfire resilience benefits that ultimately are achieved will depend heavily on the extent to which the additional firefighters actually conduct this wildfire resilience work in practice.

…And Wildfire Resilience Activities Currently Not Well‑Tracked. CalFire does not systematically track the amount of time its crews spend on wildfire resilience work versus other pursuits, which makes verifying the extent to which firefighters actually spend time on these activities difficult. Moreover, while CalFire currently tracks and reports the overall number of acres treated as a result of activities undertaken by the department, it does not report a break out of how many acres were treated directly by CalFire personnel—either by firefighting crews or by dedicated fuel reduction crews—compared to those treated by partners that receive grants administered by CalFire. Absent such information, determining whether changes in the number of acres treated are a result of additional activities being conducted by firefighters—including personnel added as a result of the 66‑hour workweek proposal—or stem from other state investments (such as the funding provided in recent wildfire resilience packages) will continue to be challenging. Should it fund the workweek change, the Legislature could use it as an opportunity to hold CalFire more accountable for achieving demonstrable wildfire resilience co‑benefits by requiring more detailed reporting on (1) how CalFire firefighters spend their time, including the amount of time spent on wildfire resilience activities, and (2) the number of acres treated by CalFire firefighters.

Recommendations

Evaluate Whether Adopting New 66‑Hour Workweek Is Affordable at This Time Given Significant General Fund Shortfall. We recommend the Legislature not treat the decision about whether to fund the implementation of a 66‑hour workweek as one that has already been made. As noted, the MOU was structured to provide the state with the flexibility to weigh the state’s fiscal condition when determining whether or not implementation of this change should proceed—including by explicitly making it subject to a legislative appropriation and by including language that negotiations over the provision could be reopened if the Governor declares a fiscal emergency. We therefore recommend the Legislature decide whether or not to fund this change in 2024‑25 based on its evaluation of the merits of the proposal, taking into account the information it now has on the costs of implementing the change and the condition of the General Fund. Given the state budget deficit, we recommend the Legislature reassess all its previous budget commitments—including those the Governor proposes revising and those he would leave intact—to determine whether they still are among its highest priorities for available funding.

Notably, given the recent deterioration in the condition of the General Fund, we expect that difficult budget decisions may lie ahead for the Legislature. Specifically, based on current revenue projections, to bring the budget into balance over the next few years, the Legislature will have to adopt some combination of ongoing program reductions and tax increases totaling at least $30 billion. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature weigh whether the benefits of the 66‑hour workweek proposal are sufficient to prioritize funding it beginning in 2024‑25, recognizing that doing so likely will come at the expense of cutting other existing ongoing commitments more deeply and/or raising taxes more significantly than would otherwise be the case.

If Uncertain Whether General Fund Can Support Proposal, Do Not Approve in 2024‑25… Several factors contribute to uncertainties around whether the General Fund can sustain this proposal in the coming years, including its high costs, current projections of budget‑year and out‑year deficits, and lack of clarity regarding future economic conditions. Moreover, as noted, the Legislature did not have comprehensive cost estimates or information on the operational implications of the proposal when it approved the concept of the workweek reduction through ratifying the MOU. Should the Legislature determine that these concerns require a more cautious approach to adopting this substantial operational change with myriad impacts at this time, we recommend it consider deferring approval of funding for the workweek reduction to a future year. (In practice, this would mean rejecting the proposal without prejudice in 2024‑25.) This option would provide the Legislature with the flexibility to sustain its long‑term commitment to the goals of addressing firefighter health and wellness, but also account for the state’s current fiscal realities. The Legislature could then reevaluate the concept of implementing the 66‑hour workweek change in the future when the state’s budget condition improves.

Delaying implementation also could offer other benefits, including providing additional time for the Legislature to consider potential modifications to the proposal (such as alternative ways to address the Fire Captain pipeline challenges) and to gather information on the possible indirect implications (such as on contracts with local agencies). Deferring providing funding now also could allow the forthcoming collective bargaining process to consider changes—which is unlikely to occur if the Legislature proceeds with appropriating the funding in 2024‑25. The administration could come back to the Legislature sometime after the next round of MOU negotiations—such as in 2025‑26 or a future year—with a similar or revised implementation proposal as part of a future MOU. This revised MOU could, for example, incorporate various details that have yet to be bargained so it better reflects the totality of the change. The negotiations also could revisit other potential options for reducing the workweek, such as using other approaches to improve the pipeline to high‑level positions instead of substantially increasing the share of Fire Apparatus Engineer positions. The Legislature could then consider whether to approve a revised MOU and fund the change to a 66‑hour workweek when the administration presents them to the Legislature again.

…And Consider Other Options for Addressing Firefighter Wellness Concerns. If the Legislature were to defer action on the proposed workweek change, we recommend it explore supporting other, less costly, steps to address concerns about firefighter health and wellness in the interim. For example, some changes the Legislature could consider include (1) various options for expanding existing health and wellness programs at CalFire to ensure that firefighters receive adequate professional support when they experience times of crisis, (2) policies to reduce the number of hours firefighters work in the offseason and/or the number of hours firefighters work per shift during severe wildfires, and (3) additional support for projects to improve forest conditions and make the state’s landscapes more resilient to the catastrophic fires that impose the most strain on firefighters. The Legislature also could consider providing a small amount of dedicated funding to support independent research to better understand the scope of problems with health and wellness among CalFire firefighters, such as the underlying causes and most promising approaches for cost‑effective solutions. Such research could help inform future decisions regarding whether reducing CalFire’s workweek is the optimal approach to improving firefighter health and wellness.

If Legislature Wants to Proceed With Implementation This Year, Consider Adding Reporting Language. If the Legislature determines that reducing CalFire’s workweek is among its highest priorities for the General Fund this year, we recommend it adopt provisional budget bill language requiring the administration to track the wildfire resilience co‑benefits of the proposal—including the time firefighters spend on wildfire resilience work and the amount of resilience work completed by CalFire’s firefighters—and to report this information on an annual basis to the Legislature. Such an annual report would provide important information to help the Legislature assess how the newly approved personnel are being used and ensure that they are maximizing the wildfire resilience co‑benefits that can be achieved. (While we think this information would be particularly important if the Legislature significantly expands CalFire staffing, the Legislature may want to consider requiring such a report regardless of its action on this proposal, as it also could help improve overall understanding of wildfire resilience co‑benefits achieved by existing wildfire response staff.)

Conclusion

The landscape has evolved markedly in a few key ways since the Legislature approved the Unit 8 MOU and the change to CalFire’s workweek in September 2022. First, the condition of the General Fund has deteriorated significantly in the intervening months, making it much more likely that the state will need to adopt significant budget reductions and/or revenue increases. Second, the magnitude of the costs and implications of the 66‑hour workweek change have become much clearer. We now know that when fully implemented, the proposal would have very large state costs, eventually totaling over $750 million annually from the General Fund. Additionally, the administration’s proposed approach would have significant effects on CalFire, resulting in a roughly 20 percent increase in the department’s budget and staffing levels and expanding its operations during months that are relatively low‑risk for wildfires. These changes would, in turn, have various direct and indirect operational impacts on both CalFire and other partner agencies. These impacts—some of which are still not fully clear—were certainly not apparent to the Legislature when it approved the Unit 8 MOU.

Given this altered context, the Legislature faces a key decision as to whether the General Fund can sustain implementing the proposed change in CalFire’s workweek in the near term, recognizing that doing so could well come at the expense of making offsetting reductions to ongoing programs elsewhere in the budget and/or adopting tax increases. If the Legislature is not certain that the General Fund can sustain the proposal right now, we recommend that it not move forward with funding the change as part of the 2024‑25 budget. Deferring implementation would provide the Legislature with greater flexibility in the future to determine its preferred course of action in light of potentially evolving budget conditions, while still sustaining its long‑term commitment to improving the health and wellness of the state’s firefighters. We also offer suggestions for interim, less costly steps the Legislature could consider taking to support firefighters if it were to delay implementation of the workweek change. If, however, the Legislature wants to prioritize General Fund for implementing this change beginning in 2024‑25, we recommend it add reporting language to help ensure that the proposal maximizes the potential for associated wildfire resilience‑related co‑benefits.