LAO Contact

- Rachel Ehlers

- Overarching Comments

- Sarah Cornett

- Zero-Emission Vehicles

- Energy

- Sonja Petek

- Water and Drought

- Coastal Resilience

- Helen Kerstein

- Wildfire and Forest Resilience

- Nature-Based Activities

- Luke Koushmaro

- Community Resilience

- Extreme Heat

- Frank Jimenez

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Circular Economy

February 14, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Discussion of Governor’s Overall Approach

- Overview of Specific Proposed Adjustments

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Overview of This Report. In response to the multibillion‑dollar budget problem the state is facing, the Governor’s budget proposal identifies significant solutions from recent augmentations made to climate, resources, and environmental programs. This report describes the Governor’s proposals and provides the Legislature with suggestions for how it might modify the spending plan to better reflect its priorities and prepare to address a potentially larger budget problem. The report begins with a discussion of the Governor’s overall approach, including background on recent funding augmentations and the state’s budget problem; a high‑level overview of the Governor’s proposals; our overarching assessment of the proposed approach; and recommendations for how the Legislature could proceed. We then walk through the Governor’s proposed solutions in each of 11 thematic areas, including examples of alternative or additional budget solutions the Legislature could consider.

Recent Budgets Included Significant General Fund Augmentations. Combined, the 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget agreements included notable amounts of new spending for a wide variety of activities related to mitigating and responding to climate change, as well as for protecting and restoring natural resources and the environment. In most cases, these augmentations represented unprecedented levels of General Fund for these types of programs, many of which historically have been supported primarily with special funds or bond funds. These budget packages also included agreements to provide additional funding in future years for a six‑year total of about $39 billion (2020‑21 through 2025‑26). To help address the General Fund shortfall that began materializing last year, the 2023‑24 spending plan made a number of revisions—including reductions, delays, and fund shifts—to the thematic packages agreed to in earlier budget deals. On net, the revised budget agreement intended to maintain $36 billion from a combination of funding sources (93 percent of the original total) from 2020‑21 through 2026‑27 for these activities. (In some budget documents the administration cites higher climate spending amounts because it includes several large programs in its totals that we exclude from ours, such as related to transportation and housing.)

Governor Proposes $4.1 Billion in General Fund Solutions for 2024‑25 Budget Problem. Similar to last year, the Governor relies on three strategies to achieve additional General Fund savings from climate, resources, and environmental programs across the budget window (2022‑23 through 2024‑25)—$2 billion from spending reductions, $1.1 billion from delaying spending to a future year, and $1 billion from reducing General Fund and backfilling with a different fund source (primarily using the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, [GGRF]). The amount of multiyear savings proposed across the combined budget window and forecast period (2023‑24 through 2027‑28) is somewhat less—$3.6 billion. This is the net result of some additional out‑year reductions which are more than offset by the costs associated with the resumption of delayed expenditures.

Given State Budget Shortfall, Overall Proposed Approach Has Several Merits. The magnitude of the General Fund problem means that the Legislature faces difficult choices in developing its budget this year. Within this context, we find a number of redeeming qualities in the Governor’s proposal. Specifically, it: (1) continues to fulfill most state objectives by sustaining the vast majority of planned multiyear funding and activities; (2) focuses reductions on recent one‑time augmentations, which is less disruptive than reducing ongoing base programs; (3) does not reduce funding that has already been committed to specific projects or grantees; (4) utilizes GGRF to sustain numerous programs while also achieving General Fund savings; and (5) eliminates most unappropriated General Fund planned for the budget year and future.

Governor’s Proposal Reflects Administration’s Priorities, Maintains Significant Amount of Unspent Funds. The administration’s choices regarding which programs to preserve and which to reduce largely reflect the Governor’s priorities. Specifically, many of the proposed cuts are to programs for which the Legislature advocated during budget negotiations, rather than those that were initially proposed by the Governor. To the extent the Legislature’s priorities differ from the Governor’s, we recommend it select a different mix of programs for funding reductions. Moreover, our review of expenditure data suggests the Governor’s proposal maintains over $1 billion in uncommitted prior‑ and current‑year appropriated funds. The Legislature could reduce some of this funding and achieve General Fund savings as additions or alternatives to the Governor’s proposals, in most cases without major disruptions to specific programs or projects. However, should it wish to capture these savings, we recommend the Legislature consider taking early action ahead of the June budget deadline as in many cases departments have plans to make additional grant awards this spring.

Proposed Delays and Out‑Year Commitments Complicate Future Budget Situation. While the Governor eliminates most of the unappropriated planned General Fund, some of this funding is only temporarily reduced—$1.7 billion in General Fund expenditures are delayed to future years. While these delays provide short‑term savings and might preserve intended activities over the longer term, they also exacerbate future budget problems by increasing out‑year General Fund spending commitments. The proposal also would maintain over $900 million in General Fund spending that previous budget agreements planned for 2025‑26. Building a multiyear spending plan that incorporates this funding sets expectations for potential projects and grantees that may be hard to keep given projected out‑year budget deficits. Moreover, the Governor’s proposal includes plans to dedicate a notable share of out‑year discretionary GGRF revenues for specific purposes (primarily for spending related to zero‑emission vehicles) rather than deferring those spending decisions to future budget negotiations. The Legislature might benefit from preserving additional flexibility around how it wants to use future GGRF resources. Overall, we recommend the Legislature minimize out‑year commitments for both the General Fund and GGRF.

Recommend Legislature Identify Alternative and Additional Budget Solutions Depending on Its Priorities and the Evolving General Fund Condition. We think that generating at least the same magnitude of General Fund solutions from climate, resources, and environmental programs as the Governor will be important in solving the budget problem. Maximizing spending reductions from one‑time funds will allow the Legislature to minimize the use of other budget tools—like reserves—that likely will be needed to address deficits in future years. To the degree some of the Governor’s proposed program reductions represent important efforts for the Legislature, however, it could opt to sustain that funding and instead find a like amount of savings by making alternative reductions, such as to programs with uncommitted funds. Besides alternative reductions, we recommend the Legislature also begin identifying options for potential additional budget solutions from these programs. Further reductions to this one‑time spending could prove helpful in a number of potential scenarios, such as if (1) the budget condition worsens (current LAO revenue projections suggest this is likely), (2) the Legislature wants to reject some of the Governor’s proposed General Fund budget solutions in other policy areas, (3) the Legislature wants to “make room” to fund some of its key priorities, and/or (4) the Legislature determines that some of the solutions included in the Governor’s proposal may not yield anticipated savings. While this process will be challenging, taking the time to consider potential options over the spring will better prepare the Legislature to make decisions in June when it will not have much time to gather information before the budget deadline.

Introduction

In response to the multibillion‑dollar budget problem the state is facing, the Governor’s budget proposes reducing net General Fund spending by $3.6 billion across six years from climate, resources, and environmental programs. The proposal saves $4.1 billion in General Fund affecting the 2024‑25 budget from a combination of spending reductions, shifting spending to different fund sources, and delaying funding for certain programs to a future year, but over the multiyear period some of these savings are offset by the resumption of the delayed spending. This report describes the Governor’s proposals and provides the Legislature with suggestions for how it might modify the spending plan to better reflect its priorities and prepare to address a potentially larger budget problem.

The report begins with a discussion of the Governor’s overall approach, including background on recent funding augmentations and the state’s budget problem; a high‑level overview of the Governor’s proposals for climate, resources, and environmental programs; our overarching assessment of the proposed approach; and recommendations for how the Legislature could proceed.

We then walk through each of the Governor’s proposed solutions by thematic area, including examples of alternative or additional solutions the Legislature could consider. These thematic areas include:

- Zero‑Emission Vehicles (ZEVs).

- Water and Drought.

- Energy.

- Wildfire and Forest Resilience.

- Nature‑Based Activities.

- Community Resilience.

- Coastal Resilience.

- Sustainable Agriculture.

- Circular Economy.

- Extreme Heat.

- Other Recent Augmentations.

Discussion of Governor’s Overall Approach

Background

Recent Budgets Included Significant General Fund Augmentations for Climate, Natural Resources, and Environmental Protection. Combined, the 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget agreements included notable amounts of new spending for a wide variety of activities related to mitigating and responding to climate change, as well as for protecting and restoring natural resources and the environment. These budget packages also included agreements to provide additional funding in future years for a six‑year total of about $39 billion (2020‑21 through 2025‑26). Most of this funding was grouped into thematic packages, such as for ZEVs, wildfire and forest resilience, and water and drought‑related activities. (Recent budgets also provided some additional augmentations for natural resources and environmental protection departments that we do not include in these totals. Additionally, as we describe in the box below, this amount does not include some additional non‑environmental funding that the administration sometimes includes in its “Climate Budget” totals.) The funding was spread across numerous departments and was primarily from the General Fund, but did include about $6 billion from other funds, mostly the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) and Proposition 98 (dedicated school funding for kindergarten through community college, used here for zero‑emission school buses). In general, these augmentations were all for activities that were one time or limited term in nature, such as providing grants for local entities to construct infrastructure or carry out habitat restoration projects. Some of the augmentations provided funding for activities to be undertaken by state agencies, such as to secure additional electricity resources intended to ensure summer electric reliability.

Clarifying Different “Climate Budget” Spending Totals

Budget documents released by the administration cite higher totals for spending on climate programs than we discuss in this report. Specifically, the administration states that intended multiyear spending for the administration’s “California Climate Commitment” originally totaled $54 billion (as compared to our $39 billion). That document also cites higher numbers for the proposed 2024‑25 budget solutions from climate‑related programs ($6.7 billion as compared to our $4.1 billion) and the revised proposed multiyear total maintained ($48 billion compared to our $34 billion). This discrepancy stems from the administration counting several additional programs in its totals that we exclude from ours. These include multiyear spending plans related to transportation infrastructure ($13.8 billion, which includes $4.2 billion in bond funding for the high‑speed rail project), housing development ($975 million), and various research initiatives and infrastructure projects at the University of California and California State University systems ($722 million), as well as a number of programs in both the health and workforce policy areas.

Presumably, the administration includes this wider array of programs in its climate spending totals because it finds that they have some nexus to addressing or responding to climate change causes and impacts. We have two primary rationales for omitting these programs from our content in this and previous reports related to spending on climate and environmental programs.

First, while many of the programs included in the administration’s totals may have some nexus with climate change, in most cases that is not their primary focus. For example, while developing infill housing could help the state meet its climate goals by reducing driving and associated emissions, the primary goal of the Infill Infrastructure Grant, Adaptive Reuse, and State Excess Site Development programs (all of which are included in the Governor’s Climate Budget totals) is to expand the state’s housing inventory. Indeed, given how widespread climate change impacts are becoming, one might be able to draw some relation between addressing or responding to climate change and an increasingly wide array of state expenditures, meaning grouping and tracking them comprehensively would become progressively more unwieldy and impractical.

Second, to help avoid confusion, we have aligned our summaries with the way the Legislature has approached discussing and adopting its decisions. That is, the thematic “packages” and the handful of other environmental program augmentations we present in this report match the content discussed and voted on in the budget subcommittees that are directly charged with considering fiscal and policy issues related to climate change, natural resources, and environmental protection. The programs we exclude from our totals were deliberated upon in other legislative budget subcommittees and were not considered together in an overarching “legislative climate budget.”

This slight divergence in how the administration and our office summarize climate spending is not new—we each have been largely consistent in our approaches since 2022‑23. (We have adjusted our totals slightly in this report to incorporate some additional “non‑package” augmentations which the Governor is now proposing to modify, as we describe in the text.) Moreover, these distinctions do not represent a true difference in spending estimates, but rather alternative choices in how to frame the discussion of state spending for climate programs.

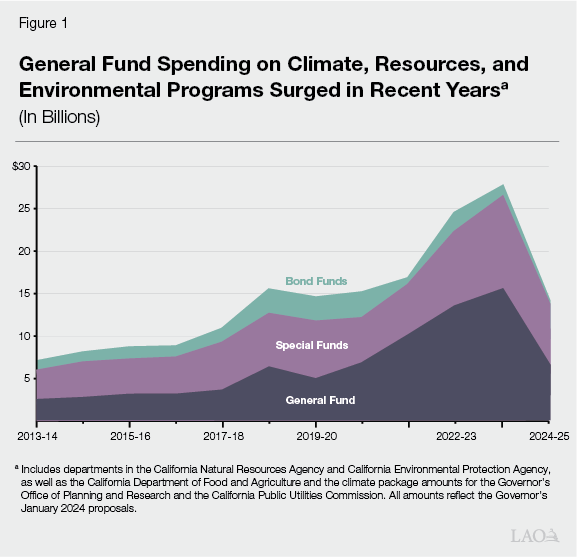

General Fund Augmentations Represent Significant Departure From Historical Funding Trends. In most cases, the recent augmentations represent unprecedented levels of General Fund for these types of programs, many of which historically have been supported with special funds or bond funds. This anomalous General Fund spending was enabled by the significant tax revenue surpluses the state received (and expected to receive) over the past couple of years. Figure 1 highlights these trends. The figure shows total annual funding (including both the recent one‑time augmentations as well as baseline funds) for the California Department of Food and Agriculture and the departments within the California Natural Resources Agency and California Environmental Protection Agency, along with just the climate‑specific funding provided to some additional departments through the thematic packages. As shown, in the years prior to 2021‑22, spending on climate, natural resources, and environmental programs averaged around $10 billion annually, and General Fund typically made up roughly one‑third of the totals. In contrast, from 2021‑22 through 2023‑24, average annual funding levels for these departments more than doubled, with the General Fund contributing more than half of the funding. In some cases, this short‑term infusion of new funding has allowed the state to expand previous programs or initiate new activities, while in others the state is providing General Fund support to continue existing activities that previously were supported with other fund sources.

Fiscal Downturn Led to Some Reductions and Modifications to Packages in 2023‑24 Budget Agreement. To help address the General Fund shortfall that began materializing last year, the 2023‑24 spending plan made a number of revisions—including reductions and delays—to the thematic packages agreed to in earlier budget deals. Specifically, the budget included General Fund reductions to the climate funding packages totaling $8.7 billion across 2021‑22 through 2023‑24, although it backfilled about $2 billion of that amount by shifting costs to other fund sources (particularly GGRF). Because the spending plan achieved some of those General Fund savings by delaying funding to future years and also anticipated additional out‑year GGRF backfills, the planned net programmatic reduction from these packages across the multiyear period was only $2.8 billion. That is, the budget agreement intended to maintain $36 billion from a combination of funding sources (93 percent of the original total) from 2020‑21 through 2026‑27 for specified climate‑related and natural resources activities. Figure 2 displays the multiyear funding totals for each package as revised by the 2023‑24 budget agreement. The figure also includes $2.3 billion for certain other significant climate and environmental spending not adopted as part of the thematic packages, including $1 billion to implement the Clean Energy Reliability Investment Plan (CERIP), $500 million to clean up contaminated brownfield sites, and $477 million for a Climate Innovation Program.

Figure 2

Revised Recent and Planned Augmentations to Climate, Resources, and Environmental Programs

(In Millions)a

|

Thematic Area |

2021‑22b |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Total |

|

Zero‑Emission Vehicles |

$3,351 |

$2,168 |

$847 |

$1,407 |

$1,406 |

$906 |

$10,085 |

|

Drought and Water Resilience |

5,244 |

1,145 |

587 |

584 |

554 |

17 |

8,131 |

|

Energy |

2,245 |

2,193 |

1,333 |

539 |

621 |

51 |

6,982 |

|

Wildfire and Forest Resilience |

1,478 |

620 |

669 |

— |

— |

— |

2,767 |

|

Nature‑Based Activities |

106 |

1,016 |

286 |

1 |

— |

— |

1,409 |

|

Community Resilience |

202 |

745 |

340 |

50 |

— |

— |

1,337 |

|

Coastal Resilience |

19 |

431 |

653 |

10 |

— |

— |

1,112 |

|

Sustainable Agriculture |

670 |

328 |

53 |

— |

— |

— |

1,052 |

|

Circular Economy |

198 |

245 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

443 |

|

Extreme Heat |

80 |

128 |

197 |

— |

— |

— |

404 |

|

Otherc |

579 |

127 |

295 |

675 |

875 |

— |

2,551 |

|

Totals |

$14,172 |

$9,146 |

$5,260 |

$3,266 |

$3,456 |

$974 |

$36,273 |

|

aReflects 2023‑24 budget agreement. Includes roughly $28 billion from the General Fund and $8.3 billion from other fund sources, including the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and Proposition 98. bAlso includes $520 million provided in 2020‑21, mostly for wildfire and forest resilience activities. cIncludes funding for various environmental‑related programs not incorporated in thematic packages, including to implement the Clean Energy Reliability Investment Plan, brownfields cleanup, and the Climate Innovation Program. |

|||||||

State Faces a Multiyear, Multibillion‑Dollar Budget Problem. Due to a deteriorating revenue picture relative to expectations from June 2023, both our office and the administration anticipate that the state faces a significant multiyear budget problem. A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when funding for the current or upcoming budget is insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. Estimates of the magnitude of this shortfall differ based on how “baseline” spending is defined—the administration estimates a $38 billion problem whereas in January our office estimated that the Governor’s budget addresses a $58 billion problem—as well as somewhat different revenue projections. Regardless of these distinctions, it is clear that the state faces the task of “solving” a substantial budget problem. Moreover, both our office and the administration estimate that, based on current revenue forecasts, the state will face significant operating deficits in subsequent fiscal years. The Governor proposes to address the 2024‑25 budget problem through a combination of strategies, including relying on reserves and reducing recent one‑time spending commitments. Given that the climate, resources, and environmental policy areas were the largest categories for recent one‑time investments, the Governor targets these programs for a notable share of these spending solutions. Under the administration’s projections, even after adopting the Governor’s proposals, the state still would face operating deficits of $37 billion in 2025‑26, $30 billion in 2026‑27, and $28 billion in 2027‑28. (We discuss the overall budget condition in our January 2024 report, The 2024‑25 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget.)

Governor’s Proposals

Uses Three Strategies to Generate $4.1 Billion in General Fund Solutions for 2024‑25 Budget Problem. Similar to last year, the Governor relies on three strategies to achieve additional General Fund savings from climate, resources, and environmental programs: reductions, funding delays, and fund shifts. This generates approximately $4.1 billion in General Fund savings across the budget window (2022‑23 through 2024‑25)—$2 billion from spending reductions, $1.1 billion from delaying spending to a future year, and $1 billion from reducing General Fund and backfilling it with a different fund source. In some cases, the Governor proposes a combination of strategies, such as delaying spending to a future year and shifting the fund source. The amount of multiyear savings proposed across the combined budget window and forecast period (2023‑24 through 2027‑28) is somewhat less—$3.6 billion. This is the net result of some additional out‑year reductions which are more than offset by the costs associated with the resumption of delayed expenditures.

- Reductions. The Governor reduces $2 billion in General Fund support for selected programs across the budget window. In some of these cases, the proposal is to rescind funding that was provided in the current or prior year that departments have not yet expended. In others, the Governor proposes not providing funding in 2024‑25 that was pledged as part of a recent budget agreement. For some programs, the Governor partially reduces the intended funding levels and for others the proposal completely eliminates the funding. Besides the $2 billion in reductions affecting the 2024‑25 budget, the proposal reduces an additional $543 million from General Fund expenditures that recent budget agreements had planned for the out‑years (2025‑26 through 2027‑28).

- Funding Delays. The Governor proposes delaying $1.1 billion in intended General Fund for certain programs, with the intent to provide it in a future year rather than within the budget window as originally planned. This would achieve near‑term General Fund savings, but shift the associated costs to a future year. In addition to the $1.1 billion originally planned for the current or budget year, the Governor also proposes delaying $635 million in General Fund expenditures that had been planned for 2025‑26.

- Fund Shifts. The Governor achieves an additional $1 billion in savings affecting the budget window by reducing or eliminating the intended General Fund for a program but then backfilling it with GGRF.

Relies on GGRF to Maintain Funding for Certain Programs. Of the $2.3 billion in GGRF that the administration estimates is available for discretionary expenditures in 2024‑25, the Governor proposes using more than three‑quarters to backfill proposed General Fund reductions, including the $1 billion in fund shifts for climate and environmental programs. This includes $557 million in current‑year expenditures (primary within the ZEV package) for which the Governor is requesting that the Legislature take early action to reduce General Fund and backfill it with GGRF. (The administration has requested that administering departments pause their spending of authorized General Fund for these programs to avoid eroding these potential current‑year savings.)

The Governor also proposes delaying $600 million in planned GGRF spending for ZEV programs from 2024‑25 to 2027‑28. While this does not directly result in General Fund savings, it has the effect of freeing up additional GGRF resources in 2024‑25 which can then be redirected for alternative purposes (such as the proposed fund shifts, which do generate budget solutions). The Governor also would sustain previous plans to provide $600 million from GGRF for the ZEV package in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. Please see our companion publication, The 2024‑25 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan, for a more detailed discussion of the Governor’s GGRF proposals.

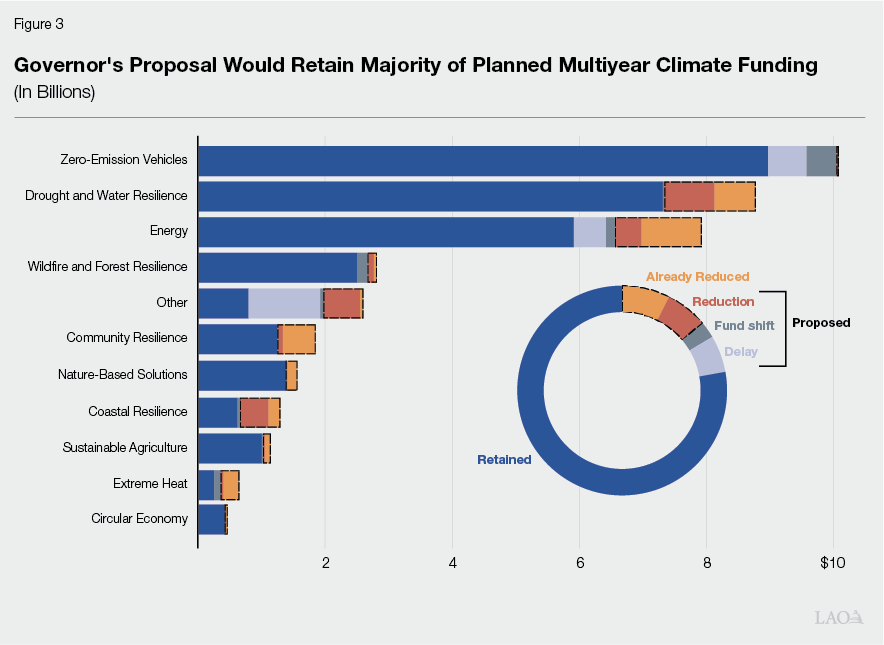

Assessment

Vast Majority of Intended Multiyear Funding Would be Maintained. Responding to the causes and impacts of climate change presents significant challenges for California and has therefore been a clear priority of both the administration and the Legislature in recent years. Indeed, the resources and environmental policy areas received the largest proportional share of discretionary one‑time General Fund spending from recent budget surpluses. The Governor’s budget largely sustains this commitment. As shown in Figure 3, even with the Governor’s proposed budget adjustments, the majority of the spending and activities included in recent budget agreements would continue. Specifically, the proposal would sustain $33.7 billion, or 86 percent of the total original intended amounts. Even these reduced amounts still would represent significant augmentations compared to historical levels for most of these programs. Moreover, as shown earlier in Figure 1, even with the Governor’s proposed reductions, funding levels for climate and resources‑related activities would remain at levels that are roughly comparable to those that were in place in 2019‑20, before the unprecedented increases that have occurred over the last couple of years. This can give the Legislature confidence that even at moderately reduced spending levels such as those proposed by the Governor, the state can continue to make significant progress on its climate and environmental goals. However, as shown in the figure, the proportion of funding proposed to be maintained—and therefore the relative magnitude of the activities that could continue being implemented—does vary by thematic package. For example, the Governor proposes maintaining essentially all of the total intended funding for ZEV programs, but only about half for coastal resilience activities.

Given State Budget Shortfall, Overall Proposed Approach Has Several Merits. The magnitude of the General Fund problem means that the Legislature faces difficult choices in developing its budget this year. Within this context, we find a number of redeeming qualities in the Governor’s proposal. Specifically, it:

- Continues to Fulfill Most State Objectives. As noted, even with the Governor’s proposed reductions, the vast majority of multiyear funding and activities included in recent budget agreements would be sustained.

- Focuses Reductions on Recent One‑Time Augmentations. Pulling back one‑time expenditures is less disruptive than making reductions to ongoing base programs.

- Does Not Reduce Funding That Has Already Been Committed to Specific Projects or Grantees. Sustaining committed funding avoids creating challenges for local grantees and project sponsors that may already have entered into contracts, attained other financing, or initiated construction.

- Utilizes Other Available Funds to Sustain Numerous Programs. The strategy of using GGRF to backfill many General Fund reductions allows the state to both achieve savings and maintain planned activities.

- Eliminates Most Unappropriated General Fund Planned for Budget Year and Future. Pulling back on plans to provide funding that had been scheduled for 2024‑25 or future years is among the least disruptive reductions the state can make, in that administering departments should not yet have proceeded in making grant solicitations or initiating projects.

Reducing Remaining General Fund From 2024‑25 and Out‑Years Could Be Less Disruptive Than Some Other Alternatives. While the Governor’s proposal eliminates most of the General Fund that past budget agreements had planned for but not yet provided, it leaves some in place. Specifically, the proposal would maintain about $380 million of General Fund spending planned for 2024‑25 (including $200 million for drinking and wastewater infrastructure projects and about $160 million for several energy programs). Moreover, the Governor sustains plans to provide about $930 million from the General Fund in 2025‑26 (including $500 million for water storage projects, over $300 million for energy programs, and $100 million to implement portions of CERIP). Because these funds have not yet been appropriated and departments do not have the legal authority to spend them, the Legislature should have some certainty that they have not yet been awarded or committed for specific projects. As such, avoiding appropriating this budget‑year and out‑year funding in the first place could be less disruptive for departments and other entities than retracting existing funding. Moreover, avoiding incorporating one‑time expenditures into out‑year spending plans would help address the projected future budget deficit and avoid setting spending expectations that may be hard to keep.

Proposed Delays Complicate Future Budget Situation. While the Governor eliminates most of the unappropriated General Fund planned for 2024‑25, some of this funding is only temporarily reduced. Specifically, as noted above, the Governor proposes delaying a total of $1.7 billion in General Fund expenditures to future years. (This consists of $1.1 billion affecting the 2024‑25 budget window and an additional $635 million from 2025‑26.) While these delays provide short‑term savings and might preserve intended activities over the longer term, they also exacerbate future budget problems by increasing out‑year General Fund spending commitments. Specifically, the delays result in higher planned spending of $315 million in 2025‑26, $665 million in 2026‑27, and $750 million in 2027‑28. As noted above with regard to the out‑year planned funding the Governor proposes to maintain, building a multiyear spending plan that incorporates this delayed funding sets expectations for potential projects and grantees that may be hard to keep given projected out‑year budget deficits. We estimate that state revenues in the out‑years would need to exceed the administration’s forecast by roughly $50 billion per year in order to sustain the total amounts of spending proposed by the Governor’s budget across all policy areas. Moreover, state priorities may shift in the coming years—based both on the revenue picture but also evolving circumstances such as potential floods or droughts, policy changes at the federal level, or other unforeseen events—and avoiding overcommitting out‑year funds would help preserve legislative flexibility to respond.

Legislature Could Pursue Alternative Approach for Prioritizing GGRF in Current and Budget Years. While the Governor’s approach of using GGRF to backfill General Fund reductions and sustain certain activities has merit, the Legislature could adopt this same strategy in a somewhat different way to align with its priorities. Specifically, it could achieve the same amount of savings as the Governor through directing GGRF funds to backfill a different mix of General Fund reductions. For example, the Governor proposes directing a total of $1.3 billion from GGRF to backfill all the proposed General Fund reductions to the ZEV package, but only $37 million to sustain a mere 8 percent of the proposed reductions to coastal resilience activities. Based on its highest priorities, the Legislature could choose a different allocation. The Legislature has flexibility around how it is able to direct GGRF revenues because the program was authorized in a way that is akin to a tax, meaning the funds can legally be used for broad purposes. Historically, the state has used GGRF for a wide range of environmental programs (along with programs in other policy areas such as transportation and housing).

Extensive Reliance on Out‑Year GGRF Makes Assumptions About Future State Priorities and Revenues. While the state dedicates a share of annual GGRF revenues to recurring ongoing activities (such as the high‑speed rail project, sustainable housing and transit programs, and forest health activities), it generally has maintained about 35 percent for discretionary spending decisions agreed upon by the Legislature and Governor as part of each year’s budget negotiations. The 2023‑24 budget package broke with historical practice somewhat by including plans to dedicate a notable share of out‑year discretionary GGRF revenues for specific purposes rather than deferring that decision to future legislative and administration negotiations. Specifically, the agreement planned to dedicate $600 million from discretionary GGRF annually for three years beginning in 2024‑25 to backfill General Fund reductions within the ZEV package. As noted above, the Governor’s proposal maintains these plans and adds an additional out‑year GGRF commitment of $600 million in 2027‑28 resulting from a proposed delay of some planned ZEV package spending. This would commit a total of $1.8 billion ($600 million per year) in future GGRF revenues from 2025‑26 through 2027‑28. While this approach allows the state to maintain long‑term intended ZEV spending plans and save General Fund, it does raise two key concerns.

First, the Legislature might benefit from preserving additional flexibility around how it wants to dedicate future GGRF funds. Specifically, given the projected budget deficits in the coming years, the Legislature could face some very difficult choices around its expenditures—including a potential need to reduce General Fund support for core ongoing programs. In such a case, the Legislature could find that it has higher priorities for GGRF revenues than sustaining planned one‑time program expansions. While nothing precludes it from revisiting these spending intentions in a future year, leaving them in its multiyear spending plan for now could set unrealistic expectations and make redirecting the funds in the coming years more challenging. In contrast, holding off on making spending commitments until it has more information about the budget situation it faces in each given fiscal year would preserve more flexibility for the Legislature to target available discretionary GGRF funds to its pressing and emerging priorities.

Second, considerable uncertainty exists around how much GGRF revenue will be available in future years. Historically, GGRF revenues have experienced significant volatility. A precipitous drop in GGRF revenues could jeopardize not only these planned out‑year ZEV expenditures but also other longstanding state priorities for which the state has historically relied upon this funding source—raising further questions about the wisdom of committing these additional funds so many years in advance.

Data Indicate Significant Amount of Appropriated Funding Has Not Yet Been Committed by Administering Departments. Of the General Fund appropriated for the thematic packages from 2021‑22 through 2023‑24, we estimate that over $4 billion remains uncommitted. (This typically means that it has not yet been dedicated to specific projects or activities.) Of this total, we estimate that the Governor is proposing solutions—including reductions, delays, and fund shifts—affecting under $3 billion. This leaves over $1 billion in uncommitted prior‑ and current‑year appropriated funding that has not been proposed for a General Fund solution. The Legislature could reduce some of this funding and achieve General Fund savings as additions or alternatives to the Governor’s proposals, in most cases without major disruptions to specific programs or projects. We discuss various specific examples of programs that the Legislature could consider reducing in the subsequent thematic sections of this report.

Governor Gives Precedence to Administration’s Initiatives Over Legislative Priorities. The administration’s choices regarding which programs to preserve and which to propose for reductions largely reflect the Governor’s priorities. Specifically, many of the proposed cuts are to programs for which the Legislature advocated during budget negotiations, rather than those that were initially proposed by the Governor. For example, the Governor proposes cutting $452 million from the multiyear budget agreement for coastal resilience activities—proportionally more than any other of the thematic packages—much of which was originally added by the Legislature. The Governor also proposes cutting several other programs that the Legislature augmented as priorities during previous budget negotiations, such as watershed climate resilience projects ($126 million proposed reduction), addressing per‑ and polyfluoroalkyl substances ($102 million proposed reduction), the Outdoor Equity Grant Program ($25 million proposed reduction), and the Urban Waterfront Program ($12.3 million proposed reduction). Notably, at the same time, the Governor proposes to maintain uncommitted funding for a number of the administration’s priorities, such as for water storage projects ($500 million proposed to retain), water resilience projects ($228 million), and coastal acquisitions ($49 million). To the extent the Legislature’s priorities differ from the Governor’s, it could select a different mix of programs for funding reductions.

We also note that the administration has considerable control over the pace at which programs are administered. For example, we understand that the administration has suspended grant solicitations for certain programs due to funding uncertainty—thus likely contributing to higher uncommitted amounts available for potential reduction—whereas others proceeded in their solicitations without interruption.

Administration Plans to Commit More Funding to Specific Projects in Coming Months. Departments in charge of administering the funding provided through recent budgets indicate that some programs expect to commit additional funds soon by making further grant awards within the next few months. For example, the administration indicates it expects to make some grant awards in spring 2024 for water resilience projects ($228 million currently uncommitted), transmission financing ($200 million currently uncommitted), the Wildlife Conservation Board’s various nature‑based solutions programs (affecting $73 million of the $100 million currently uncommitted), and funding to protect salmon (affecting $30 million of the $35 million currently uncommitted). After those grant awards are made, grantees will reasonably expect that funding is forthcoming and take steps such as entering into contracts and initiating construction activities. At that point, the Legislature will lose the option of reverting the associated funding and capturing savings without causing significant disruptions. As such, for some programs, the Legislature may want to consider taking early action to make funding reductions ahead of the June budget deadline to ensure departments do not proceed with their current plans to commit unspent funds (and erode potential savings). As noted above, we think these amounts could total over $1 billion.

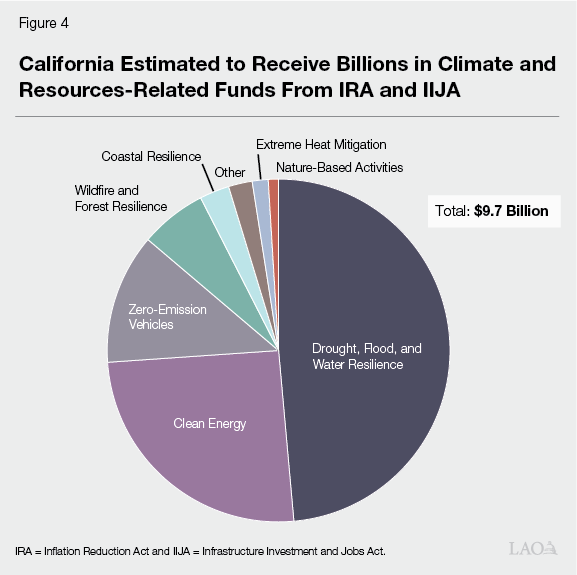

Entities in California Are Receiving Significant Federal Funds for Climate‑ and Environmental‑Related Activities. Recent federal legislation, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), have provided large increases in funding for various climate‑ and environmental‑related activities. As shown in Figure 4, we estimate that, thus far, entities in California—including state agencies and departments, local governments, tribes, private companies, and nongovernmental organizations—have received commitments totaling roughly $9.7 billion from IIJA and IRA to support a wide range of climate‑ and environmental‑related activities. Some of the program areas slated to receive the most funding include drought and water resilience (much of which is for drinking water‑related projects), clean energy, ZEVs, and wildfire and forest resilience. Additionally, many federal agencies have not yet allocated all of their IIJA and IRA funding, so entities in California will have the opportunity to compete for—and potentially secure—additional funding in the near future.

Notably, many of the federally funded activities are broadly similar to those supported by the state’s programs. However, typically they do not provide an identical dollar‑for‑dollar replacement for state funds, as they may have different eligibility criteria or allowable uses. For example, in some cases, federal programs also require a local funding contribution, which can result in higher barriers to access than some state programs. Despite these program differences, the availability of billions of dollars of federal funds to support climate‑ and environmental‑related activities will ensure that even with recent and proposed reductions to state funding, significant support still is available for many of the same broad purposes planned for in recent state budgets. This consideration may be particularly important if the Legislature finds it needs to make additional reductions to General Fund‑supported programs. For example, it could identify program areas where state entities are receiving significant infusions of federal funds (such as drinking water and ZEVs) and evaluate whether it could make additional reductions to proposed state funds and still make notable progress toward achieving its priorities.

Information on Program Effectiveness Is Limited. Ideally, the Legislature’s decisions around which programs to sustain or reduce could be informed by evidence regarding which activities are most effective at limiting the magnitude and impacts of climate change. Unfortunately, such data are not widely available. In some cases, this is because activities funded by recent budgets are being attempted for the first time. Even for most previously funded programs, however, such outcome data are not regularly collected or tracked. The lack of such information also impedes the Legislature’s longer‑term decisions, such as regarding which programs should be prioritized for future funding investments. Moreover, future decisions would benefit from information about the process of implementing the recent unprecedented level of funding, including the design of and demand for specific programs, as well as successes and challenges for both administering departments and project sponsors.

Recommendations

While we have identified some advantages to the Governor’s overall approach, the administration’s proposals do not represent the only set of options for addressing the budget problem. The Legislature could make changes to (1) reflect its priorities (such as by making alternative reductions or fund shifts), (2) avoid growing out‑year budget deficits (such as by limiting the use of funding delays), and (3) include a higher level of budget solutions (such as by making additional reductions to unspent prior‑ or current‑year funds). Below, we discuss our overarching recommendations to the Legislature for crafting climate, resources, and environmental budget solutions, which we also summarize in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Summary of Overarching Recommendations for Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maximize General Fund Savings by Reducing Significant One‑Time Spending From Climate Packages. We recommend the Legislature adopt a budget that includes significant General Fund savings from climate, resources, and environmental programs—at least as much as the Governor. While this could entail making reductions to some programs the Legislature believes are important, the vast majority of the unprecedented recent investments still would be sustained. Maximizing spending reductions from one‑time funds will allow the Legislature to minimize the use of other budget tools—like reserves—that likely will be needed to address deficits in future years. Moreover, the Legislature faces some urgency in making these changes, as this strategy will not be as readily available as time passes—once one‑time funds are spent, they no longer are available to pull back, leaving fewer (and often more disruptive) options for balancing the budget, such as making cuts to ongoing programs.

Identify Alternative and/or Additional Budget Solutions Depending on Legislative Priorities and the Evolving General Fund Condition. We think that generating at least the same magnitude of General Fund solutions from climate, resources, and environmental programs as the Governor will be important to solving the budget problem. However, we recommend the Legislature modify the Governor’s proposals to reflect its priorities. To the degree some of the Governor’s proposed program reductions represent important efforts for the Legislature, it could opt to sustain that funding and instead find a like amount of savings by making alternative reductions, such as to programs with uncommitted funds. Besides finding alternative reductions, we recommend the Legislature also begin identifying options for potential additional budget solutions from climate, resources, and environmental programs. Further reductions to this one‑time spending could prove helpful in a number of potential scenarios, such as if (1) the budget condition worsens (current LAO revenue projections suggest this is likely); (2) the Legislature wants to reject some of the Governor’s proposed General Fund budget solutions in other policy areas (such as to human services programs); (3) the Legislature wants to “make room” to fund some of its key priorities, which could include support to implement recently chaptered legislation (which the Governor’s budget does not fund); and/or (4) the Legislature determines that some of the solutions included in the Governor’s proposal may not yield the anticipated savings. While this process will be challenging, taking the time to consider, research, and select potential options over the spring will better prepare the Legislature to make decisions in May and June when it will not have much time to gather information before the budget deadline.

Consider Taking Early Action to Halt Program Spending in the Current Year and Capture Associated Savings. To the degree the Legislature identifies uncommitted funding from prior‑ and current‑year appropriations it feels are good candidates for making reductions, it may want to act on them ahead of the June budget package. This will help ensure that departments do not proceed in making grant awards (eroding the potential savings) and that the funds can be captured without causing undue disruptions. As noted above, we think the total amount of additional prior‑ or current‑year unspent funds could total over $1 billion. The Governor already has proposed a package of early action budget items to which the Legislature could add, but this likely will require identifying and acting upon the target programs within the next month or two. The Legislature also could consider directing the administration to temporarily pause all spending of uncommitted prior‑ and current‑year funding from these packages to preserve its options as it gets a better sense of the revenue picture and deliberates its budget package this spring. However, we note that the administration’s compliance with such direction may be difficult to enforce.

Use GGRF to Help Sustain Highest Legislative Priorities. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s overall strategy of using GGRF to help backfill General Fund reductions for certain programs. This approach allows the state to achieve necessary budget savings while continuing important activities. However, we recommend the Legislature adopt a GGRF spending package that preserves funding for its highest‑priority activities, which may represent a different mix from that proposed by the Governor. For example, instead of prioritizing GGRF to sustain all of the original intended funding for ZEV activities, the Legislature could redirect some of those funds to sustain some additional funding for other program areas proposed for deeper reductions, especially given the significant amount of federal funds available for ZEVs.

Minimize Out‑Year Commitments for Both General Fund and GGRF. As noted, the Governor proposed delaying about $1.7 billion in General Fund spending for climate, resources, and environmental programs to future years, sustains over $900 million in General Fund planned for 2025‑26, and also commits $1.8 billion in out‑year GGRF for maintaining intended multiyear spending levels in the ZEV package. While this approach might preserve funding over the longer term, it also exacerbates future budget problems. Given the out‑year budget forecast, we recommend that—for now—the Legislature consider both reducing planned out‑year funding that has not yet been appropriated, and reducing rather than delaying expenditures and revisiting them in a future year when it has a better sense of its available fiscal resources and highest spending priorities for both the General Fund and GGRF. This would help avoid both worsening out‑year budget deficits and creating spending expectations the state may not be able to fulfill.

Conduct Robust Oversight of Spending and Outcomes, and Consider Whether Additional Program Evaluations Might Be Worthwhile. We recommend the Legislature conduct both near‑term and ongoing oversight of how the administration is implementing—and local grantees are utilizing—funding from the recent budget augmentations. In particular, we recommend the Legislature track: (1) how the administration is prioritizing funding, especially within newly designed programs; (2) the levels of demand and over‑ or under‑subscription for specific programs; (3) any barriers to implementation that departments or grantees encounter; and (4) the impacts and outcomes of funded projects. The Legislature has a number of different options for conducting such oversight, all of which could be helpful to employ given that they would provide differing levels of detail. These include requesting that the administration report at spring budget hearings, requesting reports through supplemental reporting language, and adopting statutory reporting requirements (such as those typically included for general obligation bonds). Additionally, to the degree it might want more intensive external program evaluations for certain high‑priority programs to help assess their effectiveness, the Legislature could consider adopting language that directs the administration to set aside a portion of provided funding to contract with researchers to conduct more in‑depth studies.

Overview of Specific Proposed Adjustments

Zero‑Emission Vehicles

Recent Budget Agreements Included $10 Billion Over Several Years for ZEV Programs. The 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budgets included plans to provide a combined $10 billion over several years to different departments for a collection of activities intended to promote statewide adoption of ZEVs. Of this initial funding plan, the majority of support was from the General Fund ($6.3 billion), but also included $1.6 billion from Proposition 98 General Fund, $1.3 billion from GGRF, and about $700 million combined from federal and other special state funds. As shown in Figure 6, funded activities included programs for both light‑ and heavy‑duty vehicles, such as vehicle purchase incentives and projects to expand the state’s vehicle charging network.

Figure 6

Governor’s Proposed Changes to ZEV Package

General Fund Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

Original Multiyear Totala |

Revised Multiyear Totalb |

Proposed Reductions |

Proposed Multiyear Total |

|

School buses and infrastructure |

CARB |

$1,525c |

$1,390c |

— |

$1,390c |

|

CEC |

425c |

410c |

— |

410c |

|

|

Clean trucks, buses, off‑road equipment |

CARB |

1,100 |

1,100 |

— |

1,100 |

|

CEC |

670d |

670d |

—f,g |

670d |

|

|

ZEV fueling infrastructure grants |

CEC |

870 |

870d |

—f,g |

870d |

|

Transportation package ZEV |

CalSTA |

790e |

790e |

— |

790e |

|

Clean Cars 4 All |

CARB |

656d |

656 |

—f |

656d |

|

Clean Vehicle Rebate Project |

CARB |

525 |

525 |

— |

525 |

|

Drayage trucks and infrastructure |

CEC |

500 |

500d |

—f |

500d |

|

CARB |

445 |

445d |

—f,g |

445d |

|

|

Sustainable community plans and strategies |

CARB/CalSTA |

339 |

339d |

—f |

339d |

|

Equitable At‑Home Charging |

CEC |

300 |

300d |

—f |

300d |

|

ZEV manufacturing grants |

CEC |

250 |

250 |

‑$7 |

243 |

|

Ports |

CARB |

250 |

185 |

— |

185 |

|

CEC |

150 |

130 |

— |

130 |

|

|

Transit buses and infrastructure |

CARB |

520 |

140 |

— |

140d |

|

CEC |

230 |

60 |

—g |

60 |

|

|

Emerging opportunities |

CARB |

100 |

100 |

— |

100 |

|

CEC |

100 |

100 |

‑7 |

93 |

|

|

Charter boats compliance |

CARB |

100d |

100 |

—f |

100 |

|

Near‑zero heavy duty trucks |

CARB |

45 |

45 |

— |

45 |

|

Drayage trucks and infrastructure pilot |

CARB |

40 |

40 |

‑14 |

26 |

|

CEC |

25 |

25 |

‑9 |

16 |

|

|

ZEV consumer awareness |

GO‑BIZ |

5 |

5 |

— |

5 |

|

Hydrogen infrastructure |

CEC |

60 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Flexible ZEV transit capital program |

CalSTA |

— |

910d,h |

— |

910d |

|

Total |

$10,020 |

$10,085h |

‑$38 |

$10,047 |

|

|

aBased on 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget agreements. bBased on 2023‑24 budget agreement. cIncludes Proposition 98 General Fund. dIncludes Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). eIncludes federal funds. fDelays to 2027‑28. gFund shift to GGRF. hThe 2023‑24 budget agreement made $845 million in program reductions and added $910 million across four years for a new flexible ZEV transit program. |

|||||

|

Note: Totals may not add due to rounding |

|||||

|

ZEV = zero‑emission vehicle; CARB = California Air Resources Board; CEC = California Energy Commission; CalSTA = California State Transportation Agency; and GO‑Biz = Governor’s Office of Infrastructure and Economic Development |

|||||

The 2023‑24 budget agreement made some changes to this original package in light of the evolving General Fund condition. Specifically, it reduced multiyear funding for several programs by a total of $845 million. This included reducing $550 million for transit buses and infrastructure, $150 million for school buses and infrastructure, and $85 million for ports. However, the current‑year agreement also added money for a new flexible ZEV transit capital program that provides formula funding to transit agencies which they can use to support zero‑emission buses and related infrastructure and/or to cover their operating expenses. This program is funded with GGRF and intended to provide $910 million over four years, thereby more than offsetting the reductions in terms of total multiyear planned ZEV spending. To achieve General Fund savings, the 2023‑24 budget package also included a number of fund shifts to use GGRF revenues in place of some planned General Fund (including for out‑year expenditures) and delayed certain intended spending to 2026‑27.

Governor’s Proposal: Reduces $38 Million, Delays $600 Million, and Shifts $475 Million to GGRF. As shown in Figure 6, the Governor’s budget proposes to reduce net multiyear spending for ZEV activities by $38 million relative to the 2023‑24 budget package. The proposal also includes delays and fund shifts. Specifically:

- Modest Reductions to Four Programs ($38 Million). The budget makes reductions to the following programs: California Energy Commission (CEC) ZEV manufacturing grants ($7 million), CEC emerging opportunities ($7 million), and the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and CEC drayage trucks and infrastructure pilot projects ($14 million and $9 million, respectively).

- Funding Delays ($600 Million). The Governor proposes delaying a total of $600 million in planned expenditures from GGRF for seven programs from 2024‑25 to 2027‑28. (This delay has the net effect of freeing up $600 million in GGRF funds in the budget year, which the Governor then uses to backfill General Fund reductions for other programs. The proposal also would commit a like amount of GGRF in 2027‑28 for the delayed expenditures.) The affected programs are: CEC ZEV fueling infrastructure grants ($120 million); CEC clean trucks, buses, and off‑road equipment ($137 million); Clean Cars 4 All ($45 million); CEC and CARB drayage trucks and infrastructure ($50 million and $48 million, respectively); CARB sustainable community plans and strategies ($100 million); CEC Equitable At‑Home Charging ($80 million); and CARB charter boats compliance ($20 million). The administration notes that prior‑year funding is available for most of these programs to meet applicant demand in the interim.

- Current‑Year Shift to GGRF ($475 Million, Early Action). The budget proposes shifting $475 million of current‑year ZEV expenditures from General Fund to GGRF for the following programs: ZEV fueling infrastructure grants ($219 million); drayage trucks and infrastructure ($157 million); transit buses and infrastructure ($29 million); and clean trucks, buses, and off‑road equipment ($71 million). This proposed change is enabled by higher‑than‑projected cap‑and‑trade auction revenues materializing in the current year. The Governor is requesting that the Legislature take early action to effectuate this fund shift so that programs can proceed with making grant awards this spring.

LAO Comments: Legislature Could Consider Alternative and/or Additional Reductions. While there is significant unspent funding planned for the budget year and out‑years in the ZEV package, most of this funding is from GGRF. Consequently, making reductions would not automatically generate General Fund savings. However, the Legislature could achieve further budget solution if it were to reduce GGRF spending on ZEV activities, make additional General Fund reductions elsewhere, then redirect the freed‑up GGRF to backfill those other priorities. Based on available data on remaining funds, the Legislature could consider reducing the following:

- School Bus and Infrastructure (About $1 Billion in Proposition 98 General Fund). The 2022‑23 budget package established a new program to fund zero‑emission school buses and related infrastructure administered by CARB and CEC. The Legislature previously approved $500 million of Proposition 98 General Fund to fund the first round of grants and adopted intent language to allocate additional funding in the future. The Governor’s budget provides an additional $500 million of Proposition 98 General Fund for a second round of grants in 2024‑25. The administration has indicated it is in the process of, but has not yet allocated, the original grant funding. With this in mind, we recommend the Legislature: (1) consider reverting the prior funding (about $500 million) to achieve General Fund savings, and (2) reject the new $500 million proposed in the budget year. For more information about the school bus spending, please see our report, The 2024‑25 Budget: Proposition 98 K‑12 Education Analysis.

- Buses and Off‑Road Equipment (At Least $249 Million). CARB has used its appropriations for this category of activities to fund its Hybrid and Zero‑Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program. Expenditure data suggest $249 million of the GGRF previously appropriated for this program is unspent and could be reverted and redirected to achieve General Fund savings elsewhere. CEC also received funding in this category but the administration had not provided data on CEC’s expenditures as of this writing.

- Charter Boats Compliance ($60 Million). CARB closed its grant solicitations for this program in December 2023 and currently is reviewing applications. Approximately $40 million of General Fund plus $20 million of GGRF remains in the balance. The Legislature could consider reverting this $60 million but likely would have to take early action in order to capture the savings as CARB is in the process of preparing to award the funds.

- Emerging Opportunities ($47 Million). CARB is using this funding for ZEV technology demonstration projects. Of the $53 million General Fund originally allocated, $47 million remains in the program’s balance and could be reverted for General Fund savings.

- CEC ZEV Program Funding (Unknown, Potentially Several Hundreds of Millions of Dollars). Updated information on CEC’s ZEV package expenditures was not available at the time of this writing. Based on historical CEC ZEV spending time lines, we suspect that several hundreds of millions dollars of unspent funding could be available. We will provide more information to the Legislature after we receive these data from the administration.

Water and Drought

Recent Budget Agreements Included $8.8 Billion Over Several Years for Water and Drought‑Related Activities. As shown in Figure 7, the 2022‑23 budget appropriated and intended to provide a combined $8.8 billion ($8.3 billion from the General Fund and about $450 million from other funds) over several years to various departments for emergency drought response and water resilience activities. Nearly half of the funding ($4 billion) was to support activities related to drinking water quality and availability, water recycling and groundwater cleanup, water supply, and flood management. About $1.4 billion was intended for immediate drought response activities, such as for the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) to respond to drinking water emergencies. The remaining funding ($3.3 billion) was to support habitat restoration, water quality, and conservation activities. The 2023‑24 budget agreement reduced total multiyear funding by $632 million General Fund (7 percent). Major reductions included $278 million for water recycling, $119 million for Salton Sea restoration activities, and $60 million for local assistance grants related to implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

Figure 7

Governor’s Proposed Changes to Water and Drought Resilience Package

General Fund Unless Otherwise Noteda (In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

Original Multiyear Totalb |

Revised Multiyear Totalc |

Proposed Reductions |

Proposed Multiyear Total |

|

Drinking Water, Water Supply, Flood |

$4,025 |

$3,732 |

‑$224 |

$3,508 |

|

|

Drinking water, wastewater projects |

SWRCB |

$1,700 |

$1,700 |

— |

$1,700 |

|

Water recycling, groundwater cleanup |

SWRCB |

800 |

522 |

‑$174d |

348 |

|

Water conveyance, water storage |

DWR |

700 |

700 |

— |

700 |

|

Flood management and planning |

DWR |

644 |

644 |

— |

644e |

|

Dam safety |

DWR |

100 |

100 |

‑50 |

50 |

|

Aqueduct solar panel pilot study |

DWR |

35 |

20 |

— |

20 |

|

Watershed climate studies |

DWR |

25 |

25 |

— |

25 |

|

Water storage tanks |

DWR |

21 |

21 |

— |

21 |

|

Immediate Drought Response |

$1,439 |

$1,409 |

‑$27 |

$1,382 |

|

|

Community drought relief |

DWR |

$800 |

$800 |

— |

$800 |

|

Data, research, communications |

Various |

202 |

202 |

— |

202 |

|

Water rights activities |

SWRCB |

113 |

113 |

— |

113e |

|

Drought contingency control section |

Various |

96 |

96 |

— |

96 |

|

Forecasting water supply/runoff |

DWR |

101 |

101 |

‑$27 |

74f |

|

Drinking water emergencies |

SWRCB |

62 |

62 |

— |

62 |

|

Drought salinity barrier |

DWR |

27 |

3 |

— |

3 |

|

Drought food assistance |

DSS |

23 |

23 |

— |

23 |

|

Conservation technical assistance |

DWR |

10 |

10 |

— |

10e |

|

Water refilling stations at schools |

SWRCB |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Habitat/Nature‑Based Solutions |

$1,208 |

$1,208 |

‑$438 |

$770 |

|

|

Wildlife and habitat projects |

CDFW, DWR |

$459 |

$459 |

— |

$459 |

|

Watershed climate resilience |

WCB |

334 |

334 |

‑$312 |

22 |

|

Watershed climate resilience |

DWR |

161 |

161 |

‑126 |

35 |

|

Aquatic/large‑scale habitat projects |

Various |

149 |

149 |

— |

149 |

|

Spending from various bonds |

WCB, DWR |

105 |

105 |

— |

105 |

|

Water Quality and Ecosystem Restoration |

$1,191 |

$1,027 |

‑$102 |

$925 |

|

|

Water resilience projects |

CNRA |

$445 |

$445 |

— |

$445e |

|

Streamflow enhancement program |

WCB |

250 |

250 |

— |

250 |

|

Salton Sea |

DWR |

220 |

101 |

— |

101 |

|

PFAs support |

SWRCB |

200 |

155 |

‑$102 |

53 |

|

Urban streams and border rivers |

Various |

70 |

70 |

— |

70 |

|

Clear Lake |

CNRA |

6 |

6 |

— |

6 |

|

Conservation/Agriculture |

$916 |

$771 |

‑$19 |

$752 |

|

|

SGMA implementation |

DWR |

$356 |

$296 |

— |

$296 |

|

Water conservation programs |

DWR |

180 |

180 |

— |

180 |

|

SWEEP |

CDFA |

160 |

120 |

—g |

120 |

|

Multibenefit land repurposing |

DOC |

110 |

90 |

— |

90 |

|

Agricultural conservation |

DWR, CDFA |

70 |

45 |

— |

45 |

|

Relief for small farmers |

CDFA |

25 |

25 |

‑$13 |

12 |

|

On‑farm technical assistance |

CDFA |

15 |

15 |

‑6 |

9 |

|

Totals |

$8,779 |

$8,148 |

‑$810 |

$7,337 |

|

|

aIn total, about $450 million is from a variety of non‑General Fund sources, including bond funds, federal funds, special funds, and reimbursements. bBased on 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget agreements. cBased on 2023‑24 budget agreement. dGovernor proposes delaying $100 million from 2022‑23 to 2025‑26. eIncludes funding from sources other than General Fund. fOriginal appropriation was $16.75 million ongoing. Governor proposes reducing annual amount to $10 million beginning in 2024‑25. gGovernor proposes delaying $21 million until 2024‑25 and shifting the fund source from General Fund to Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. |

|||||

|

SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; DWR = Department of Water Resources; DSS = Department of Social Services; CDFW = California Department of Fish and Wildlife; WCB = Wildlife Conservation Board; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; PFAs = per‑ and polyfluoroalkyl substances; SGMA = Sustainable Groundwater Management Act; SWEEP = State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program; CDFA = California Department of Food and Agriculture; and DOC = Department of Conservation. |

|||||

Governor’s Proposal: Reduces $810 Million, Delays $100 Million, and Delays and Shifts $21 Million. Also shown in Figure 7, the Governor’s budget proposes to reduce multiyear General Fund spending for water and drought resilience, relative to the 2023‑24 budget agreement, by $810 million. (The $7.3 billion the Governor proposes to retain represents 84 percent of the original 2022‑23 package.) The proposal would revert $100 million appropriated in earlier years for water recycling projects administered by SWRCB and delay providing it until 2025‑26. Similarly, for the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s (CDFA’s) State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program, the proposal would revert $21 million General Fund appropriated in earlier years and instead provide the same amount of funding from GGRF in 2024‑25. Proposed reductions include:

- Watershed Climate Resilience. The budget proposes to reduce funding by $438 million ($126 million to the Department of Water Resources [DWR] and $312 million to the Wildlife Conservation Board [WCB]), retaining just 11 percent ($56 million) of the original amount. DWR indicates that the proposed reduction would affect the number of long‑term projects it can fund but not its near‑term program plan, which includes six pilot studies and a subsequent set of grants. While the reduction will lead to WCB awarding fewer grants, it has other funding sources available for these types of projects, including $43 million from Proposition 68 (2018) and annual support of $21 million from the Habitat Conservation Fund.

- Water Recycling and Groundwater Cleanup: The proposal would reduce funding for groundwater cleanup by $55 million and for water recycling by $119 million (the 2023‑24 budget already reduced funding by $278 million). (As noted above, the budget also would delay $100 million until 2025‑26 for water recycling.) Relative to the original package, the budget would retain $348 million, or 43 percent for these two programs. SWRCB indicates it would prioritize providing low‑cost financing for water recycling projects through its State Revolving Fund (SRF) programs and providing grants for water recycling and clean water projects in disadvantaged communities. In addition, the federal IIJA is providing more federal funding than normal for SRF programs between 2022 and 2026 ($1.16 billion for the Drinking Water SRF and $790 million for the Clean Water SRF), which can be used for water recycling and groundwater cleanup projects.

- Per‑ and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAs) Support. The proposal would reduce funding for addressing PFAs by $102 million (retaining $53 million, or 27 percent, of the original total, after accounting for additional reductions made in 2023‑24). PFAs are long‑lasting chemicals which are hard to break down and have been used in a variety of consumer and industrial products. Reduced funding would result in fewer and/or smaller state‑funded grants. However, SWRCB will receive approximately $460 million in federal funds through its SRF programs from 2022 through 2026 to address “emerging contaminants,” which include PFAs.

- Dam Safety. The budget would halve funding—from $100 million to $50 million—for dam safety pilot projects administered through a competitive grant program by DWR. The reduction would result in DWR funding fewer projects.

- Agricultural Programs. The budget would reduce funding for drought relief for small farmers by $13 million and for on‑farm technical assistance by $6 million. (Relative to the original package, the budget would retain $21 million, or 53 percent, for these two programs.) CDFA indicates that demand for drought relief grants was lower than anticipated (it awarded about $12 million of the available $25 million), perhaps in part due to a similar program being offered through the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO‑Biz). The on‑farm technical assistance program was similarly undersubscribed, although CDFA indicates this could reflect the limited capacity of technical assistance providers, rather than the needs of farmers.

- Forecasting Activities. The budget would reduce an ongoing appropriation for DWR—from $17 million to $10 million annually—that supports water supply/runoff forecasting. Specifically, the reduction would result in conducting fewer aerial snow surveys and conducting them (and associated modeling) in fewer watersheds.

LAO Comments: Legislature Could Consider Alternative and/or Additional Reductions. In light of the state budget condition, the Legislature has several options for additional and/or alternative reductions from the water and drought resilience package.

- Water Storage Projects ($500 Million in 2025‑26). The administration’s original proposal for this funding noted that it would build on the $2.7 billion provided by Proposition 1 (2014) for water storage projects, yet specific details on how the funds would be used have not been provided. Given this funding has not yet been appropriated, eliminating it likely would be less disruptive compared to certain other options before the Legislature.

- Drinking Water Project Grants ($200 Million). While these programs are important, the state currently has an unprecedented amount of federal funding available for these purposes through the federal SRFs. In addition, state statute requires an annual GGRF appropriation of $130 million (through 2030) to SWRCB for the same types of drinking water projects. As such, the state could continue to pursue its goals and focus on the drinking water needs of disadvantaged communities even with a reduction in General Fund support.

- Water Recycling (Reduce Rather Than Delay $100 Million). Although eliminating this funding—rather than delaying it, as proposed by the Governor—would reduce the number of projects SWRCB could support with state funding (which is more flexible than federal funding), other funding sources are available for these projects. Specifically, SWRCB can use federal funds provided through the SRF for water recycling projects.

- Revert Unspent Funding Provided in Earlier Budgets. Of the $6.5 billion General Fund already appropriated for water and drought resilience packages across 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24, the Governor proposes reducing about $524 million of uncommitted funds (as discussed above). Based on our review of other uncommitted funds, the Legislature could consider additional reductions of close to $775 million. For example, SWRCB has about $300 million in uncommitted funds for drinking water/wastewater programs. SWRCB expects to commit a good portion of this funding between April and June, with an estimated $65 million remaining by the end of the 2023‑24 fiscal year. Consequently, depending on how much of this funding the Legislature wished to pull back, it may have to act quickly to capture the potential savings that currently are available. While these programs remain important, particularly among disadvantaged communities, SWRCB could partially offset reductions with federal SRF funding and its annual GGRF appropriation. Additionally, the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) has approximately $228 million in uncommitted funds for water resilience grants. The administration indicates it will select awardees in the March/April time frame, meaning the Legislature would have a short window to act and reduce these funds to solve the budget problem. Other examples include $50 million for dam safety (given the Governor already proposes a reduction of the other $50 million, an additional reduction would eliminate the pilot program) and $104 million for WCB’s streamflow enhancement program.

Energy