LAO Contact

Table of Contents

Main Report

Appendix 1: Spending Solutions

Appendix 2: All Other Solutions

May 17, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

Initial Comments on the

Governor’s May Revision

Key Takeaways

We Estimate Governor Addressed a $55 Billion Budget Problem. The Governor cites a budget problem of $27 billion. Based on the administration’s revenue estimates and proposals, we estimate the Governor addressed a larger deficit than this—$55 billion. The difference is attributable to what our offices consider to be current law, particularly for school and community college spending. While we would maintain that our approach more accurately reflects current law, these scoring differences do not reflect substantive differences in our views of the state’s fiscal position.

The Governor Addresses the Deficit by Adjusting Spending. The May Revision primarily solves the budget problem by adjusting spending. Spending-related solutions (including both school and community college spending and other spending) represent nearly 90 percent of the total solutions. Of this total, $22 billion are related to school and community college funding changes and $16 billion are spending reductions, while the remaining solutions comprise other types, like fund shifts. The Governor also reduces the state’s reliance on reserves—using only $4 billion in reserve withdrawals to cover the deficit, significantly less than the $13 billion proposed in January.

Proposed Budget Structure Puts the State on Better Fiscal Footing. The overall structure of the Governor’s May Revision improves the fiscal health of the state in a number of ways. First, by proposing the state use less in reserves, the Governor preserves an important tool to address budget problems, which are likely to continue to emerge. Second, by further reducing one-time and temporary spending, the Governor leverages a “use it or lose it” tool that improves budget resilience. Finally, the Governor proposes new statutory language that would temporarily set aside anticipated surplus revenues for at least a year. While executing this proposal would be technically complex, we think the underlying idea is meritorious.

Next Steps for the Legislature. As the Legislature enters the final phase of budget deliberations, we suggest four key areas of consideration. First, given the significant decline in prior-year revenues, the Legislature will need to decide how to address prior-year funding for schools and community colleges. Second, the Governor proposes ongoing spending reductions that total $8 billion within a few years, which involve trade-offs and, in some cases, reductions to core service levels. Although the administration’s focus for ongoing reductions tends to be on newer programs and program expansions, there could be longer-standing programs that the Legislature wishes to revisit. Third, we suggest the Legislature consider whether particular proposed solutions raise serious concerns. For example, two major proposals raise concerns for our office: the suspension of net operating loss (NOL) deductions and unallocated state operations reductions. Finally, given that our revenue forecast is somewhat below the administration’s forecast, we would suggest the Legislature consider whether or not it is comfortable with this downside risk to the state’s budget picture. This risk might be acceptable, however, particularly if the Legislature adopts the May Revision budget structure.

Introduction

On May 14, 2024, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (The Governor also held a press conference and released a summary of the budget update on May 10, 2024.) This annual proposed revised budget is referred to as the May Revision. In this brief, we provide a summary of and comments on the Governor’s revised budget, focusing on the overall condition and structure of the state General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail, provide additional comments in hearing testimony, and update our multiyear forecast of the budget’s condition. The information presented in this brief is based on our understanding of the administration’s proposals as of May 14, 2024. In many areas, our understanding of the proposals will continue to evolve.

The Budget Problem

In this section, we present our estimates of the budget problem that the Governor addressed in the May Revision. The estimates in this section are predicated on the administration’s revenue projections and spending proposals. Our analysis also focuses on the three-year budget window under consideration: 2022-23 through 2024-25.

What Is a Budget Problem? A budget problem—also called a deficit—arises when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. A budget problem is inherently a point-in-time estimate that reflects information available at the time of development, forecasts of future revenues and spending, and assumptions about the extent to which changes in costs are due to current policy (that is, whether or not they are “baseline changes”). When changes in costs do not occur automatically under current policy, we count them as budget solutions or augmentations. We take this approach in order to provide the Legislature visibility into the full scope of the administration’s choices. The remainder of this section walks through the sources of our differences with the administration and how those differences impact the budget problem estimate.

How Big Is the Budget Problem?

We Estimate Governor Addressed a $55 Billion Budget Problem. The Governor cites a budget problem of $27 billion. Under our estimates, the administration addressed a larger deficit than this—$55 billion. This difference is largely due to differences in two areas:

Schools and Community Colleges. Our calculation of the budget problem assumes $22 billion in higher baseline spending on schools and community colleges. This difference mainly relates to our treatment of changes in the minimum spending requirement established by Proposition 98 (1988). Compared with the estimates from June 2023, the minimum requirement has decreased significantly in 2022-23 and 2023-24. The May Revision assumes spending on schools and community colleges is reduced to the lower level each year and treats all of the corresponding spending adjustments as baseline changes. Our approach, by contrast, calculates baseline school spending under current law. The difference between these approaches is most evident in our treatment of the Governor’s proposal to “accrue” the cost of $8.8 billion in prior-year payments to schools to future years. The administration treats this proposal like an automatic change and calculates the deficit assuming it has already occurred. By contrast, we treat the proposal like a policy choice—one that has not yet occurred—because it would modify a law the Legislature adopted several years ago indicating the state would not reduce school spending in the prior year.

Other Solutions. Across the rest of the budget, we also count about $6 billion in other budget actions as solutions that the administration counts as baseline changes. This includes, for example, $1.6 billion in spending delays for competitive transit grant funds, a sweep of nearly $600 million in unawarded General Child Care slots, and a change in the distribution of funds in the school facilities program that delays nearly $700 million in spending until after 2024-25.

Together, these scoring differences account for the roughly $27 billion difference in our office’s accounting of the budget problem and the administration’s scoring. While we would maintain that our approach more accurately reflects current law, these scoring differences do not reflect substantive differences in state’s fiscal position.

Budget Problem Has Shrunk Since January Due to Early Action. In January, we estimated that the budget problem under the administration’s assumptions was $58 billion. The budget problem is now slightly lower—$55 billion. There are four notable factors contributing to this difference. First, in April, the Legislature passed an early action package that reduced the size of the budget problem by $17.3 billion (Chapter 9 of 2024 [AB 106, Gabriel]). Second, the administration reduced the total amount of new discretionary spending proposals by roughly $200 million (from $1.2 billion in January to about $1 billion). Third, offsetting this, the administration’s revenue forecast eroded by roughly $12 billion. (As we discuss more later, our office’s revenue estimates are slightly lower than this.) This downgrade reflects weakness in recent collections across income, corporation, and sales taxes. Fourth, some baseline costs are higher compared to January. For example, higher estimated caseload in the state’s Medi-Cal program results in about $2 billion in higher costs across the budget window.

How Does the Governor Propose Addressing the Deficit?

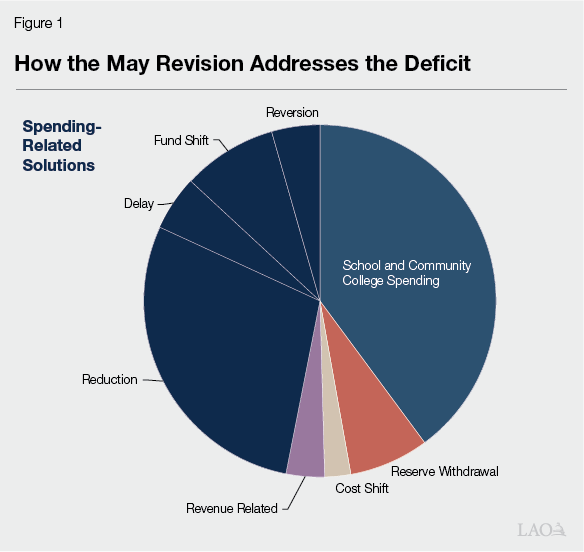

Figure 1 summarizes the budget solutions that this section describes in detail. (These descriptions reflect remaining proposals after the adoption of the early action package.) The May Revision primarily solves the budget problem by adjusting spending. Spending-related solutions (including both school and community college spending and other spending) total $48 billion and represent nearly 90 percent of the total solutions. Spending-related solutions include reductions, fund shifts, delays, and reversions. In addition, the May Revision includes $4 billion in reserve withdrawals, $1 billion in cost shifts, and about $2 billion in revenue-related solutions. Online appendices 1 and 2 (forthcoming) list all of the solutions by area.

School and Community College Spending

The California Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges—otherwise known as Proposition 98. The state meets this requirement through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. When General Fund revenue declines, the minimum requirement usually declines in tandem. Most school spending, however, does not automatically decrease when the minimum requirement drops in the current or prior year. Due to lower General Fund revenues, the amount of authorized school and community college spending exceeds the minimum requirements for 2022-23 and 2023-24. The May Revision aligns school and community college spending to the minimum required level in each year of the budget window. This reduces total General Fund spending on schools and community colleges by $22 billion.

Spending-Related Solutions

Reductions. Under our definition, a spending reduction occurs when the Governor proposes that the state spend less money than what has been established under current law or policy. More colloquially, these are spending cuts. The May Revision includes $16 billion in spending-related reductions. This includes:

One-Time and Temporary Reductions. Within the budget window, the May Revision eliminates or reduces over $11 billion in one-time or temporary spending. For example, the May Revision forgoes nearly $1 billion in provider rate increases in the Managed Care Organization package (growing to over $2 billion in 2025-26), reduces $325 million in funding for the multifamily housing program, and reduces the Regional Early Action Planning program by $300 million.

Ongoing Spending Reductions. The May Revision also includes about $5 billion in ongoing spending reductions in 2024-25, which grow to roughly $8 billion over time. These ongoing reductions include, for example: an unallocated cut to state operations, an indefinite pause to the multiyear child care slot expansion plan, and a reduction to foster care permanent rates (which would be subject to a trigger restoration if revenues are sufficient to fund them in the future).

Fund Shifts. Fund shifts are budget solutions that use other fund sources—for example, special funds—to pay for a cost typically incurred by the General Fund. These shifts reduce expenditures from the General Fund as they simultaneously displace spending that these special funds otherwise would have supported. As a result, we consider these to be a type of spending-related solution because they typically result in lower overall state spending, inclusive of all funds. We estimate the May Revision includes $5 billion in fund shifts. This primarily includes General Fund costs that have been shifted to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, federal funds, and other special funds.

Delays. We define a delay as an expenditure reduction that occurs in the budget window (2022-23 through 2024-25), but has an associated expenditure increase in a future year of the multiyear window (2025-26 through 2027-28). That is, the Governor proposes moving the spending to a year in the near future. (We do not categorize a proposal as a delay if it would shift the cost outside of the multiyear window. As such, some proposals that the Governor calls “pauses,” we refer to as reductions.) Nearly $3 billion of the May Revision spending-related solutions are delays. As a result, proposed spending is higher in the out-years.

Reversions. Costs for state programs sometimes come in lower than the amount that was appropriated. This often occurs, for example, when the state overestimates uptake in a new program or as a routine matter in programs where spending is uncertain due to factors like caseload. When actual state costs are below budgeted amounts, a reversion occurs after a period of time—typically, three years. The reversion returns the unspent funds to the General Fund. In this year’s budget, the Governor proposes accelerating some reversions that would have otherwise occurred in the future and proposes proactively reverting certain funds that otherwise are continuously appropriated (which has the effect of realizing savings from the unspent funds that would not otherwise occur). While not all of these amounts represent lower state spending over the long term, they do result in savings today at a cost of forgone savings in the future. As a result, we count them as spending-related solutions. We estimate the May Revision includes about $2 billion in reversions.

Reserve Withdrawals

Budget Stabilization Account. Proposition 2 (2014) governs deposits into and withdrawals from the state’s general-purpose constitutional reserve—the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). Under these rules, the state can make withdrawals from the constitutionally required balance of the BSA in a fiscal emergency, which occurs when estimated resources for the upcoming year are insufficient to cover the costs of the previous three enacted budgets, adjusted for inflation and population. Although the Governor has not officially declared a budget emergency for 2024-25 (or any other year in the budget window), we agree that the conditions for a declaration exist. After a budget emergency is declared, the state can withdraw up to half of the constitutional balance of the BSA. (The Legislature also can withdraw the entire “discretionary” balance of the BSA at any time, which are amounts that were deposited into the fund on top of Proposition 2 requirements.) In the May Revision, the Governor proposes withdrawing about $3 billion from the BSA—significantly less than the roughly $12 billion withdrawal proposed in January.

Safety Net Reserve. Similar to January, the Governor also proposes withdrawing the entire balance of the Safety Net Reserve—$900 million. The Safety Net Reserve was designed to help cover costs of increasing caseload in Medi-Cal and the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program in the event of an economic downturn.

Cost Shifts

The May Revision includes about $1 billion in cost shifts. We define cost shifts as budget actions that achieve savings in the present, but result in a binding obligation or higher cost for the state in a future year. In that way, these actions can be similar to borrowing, but are often not explicitly structured as such. For example, major categories of cost shifts include: an additional $607 million in special fund loans to the General Fund, and a proposal to shift funding for the Capitol Annex project from cash to bond debt service that provides $450 million in budget savings within the budget window.

Revenue-Related Solutions

We estimate the May Revision includes about $2 billion in revenue-related solutions. The largest revenue solution is a proposal to not allow businesses with more than $1 million in income to claim NOL deductions on their taxes in 2025, 2026, and 2027. This proposal provides $900 million in additional revenue in 2024-25 and over $5 billion in future years. In addition, the May Revision includes a proposal to increase the Managed Care Organization tax and use the nearly $700 million in increased revenues to offset General Fund costs.

Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget after accounting for the May Revision proposals and solutions. We also describe the condition of the school and community college budget.

General Fund Budget

Figure 2 shows the General Fund condition under the May Revision. The state would end 2024-25 with $3.4 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). The SFEU is the state’s operating reserve and essentially functions like an end-of-year balance. The State Constitution’s balanced budget provision prohibits the state from enacting a negative SFEU balance for the upcoming fiscal year, in this case, 2024-25. While historically the state mostly has enacted SFEU balances between $1 billion and $4 billion, the Legislature can choose to set the balance at any level above zero.

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 Revised |

2023‑24 Revised |

2024‑25 Proposed |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$63,631 |

$46,260 |

$9,727 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

178,544 |

189,354 |

205,249 |

|

Expenditures |

195,915 |

225,888 |

200,974 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$46,260 |

$9,727 |

$14,001 |

|

Encumbrances |

$10,569 |

$10,569 |

$10,569 |

|

SFEU Balance |

$35,691 |

‑$842 |

$3,432 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$21,708 |

$22,555 |

$19,429 |

|

SFEU |

35,691 |

‑842 |

3,432 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

— |

|

Total Reserves |

$58,299 |

$22,613 |

$22,861 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Under May Revision, Reserves Would Total $23 Billion by End of 2024-25. As mentioned earlier, the Governor proposes using $3 billion from the BSA and $900 million from the Safety Net Reserve to help address the budget problem. This means the state would end 2024-25 with nearly $23 billion in General Fund reserves—considerably more than the $14.5 billion proposed in January. (Under the May Revision, the state would withdraw all of the remaining balance of the School Reserve, which is available only for school and community college spending.)

School and Community College Budget

Funding for Schools and Community Colleges Down $3.7 Billion Over Budget Window. Compared with the estimates included in the Governor’s budget, the administration estimates the constitutional minimum funding level for schools and community colleges is down $3.7 billion over the 2022-23 through 2024-25 period. Most of this decline ($3 billion) is attributable to 2023-24. This downward revision consists of a $4.2 billion reduction in required General Fund spending, partially offset by a $489 million increase in local property tax revenue. The May Revision includes several actions to mitigate the effects of lower Proposition 98 spending on schools. The primary actions are: (1) reserve withdrawals, (2) cost shifts, and (3) repurposing of unspent/unused funds. These actions also free up funding for a few smaller augmentations.

Withdraws Remaining Balance in Proposition 98 Reserve. The Proposition 98 Reserve is a statewide reserve account for school and community college funding. The Governor’s budget proposed to make a discretionary withdrawal of $5.7 billion from this account to help cover costs for existing school and community college programs in 2023-24 and 2024-25. The May Revision proposes to withdraw an additional $3.9 billion, drawing down the entire balance in the account.

Increases Size of Maneuver That Would Shift Costs into the Future. Under the Governor’s budget, the administration projected the 2022-23 spending level for schools and community colleges was $8 billion higher than the required minimum funding level. The Governor’s budget proposed “accruing” these $8 billion in prior-year payments to future years, without changing the amount disbursed to schools and community colleges. These costs would be recognized gradually over a five-year period, beginning in 2025-26. The May Revision retains this funding maneuver and accrues an additional $768 million to future years, reflecting a further decline in the minimum funding level for 2022-23.

Commits to Additional Spending in a Few Areas. Most notably, the May Revision provides an additional $300 million to cover a higher 1.07 percent statutory cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for existing school and community college programs. (The statutory COLA is up from 0.76 percent in the Governor’s budget.) The May Revision also includes $395 million in one-time funding for zero-emission school buses, in addition to the $500 million in the Governor’s budget.

Assessing the Governor’s Approach

Proposed Budget Structure Puts State on Better Fiscal Footing. Although we will have more comments on the multiyear outlook for the budget in the coming week or so, the overall structure of the May Revision improves the fiscal health of the state in a number of ways. Specifically, the May Revision:

Reduces Reliance on Reserves. Compared to his January proposal, the Governor reduces reliance on reserves to address the deficit. The Governor does so despite the fact that the state faces a serious budget problem and that the administration’s revenue forecast deteriorated between January and May. Although this means making more difficult decisions this year, using less in reserves now also gives the Legislature more tools to address more budget problems that are quite likely to continue to emerge in the coming years.

Further Reduces One-Time and Temporary Spending. The Goveror proposes the state pull back more one-time and temporary spending. We think this is the right approach for two reasons. First, when this spending was adopted, it was understood that it might need to be pulled back if future budget problems arise. Second, reducing one-time and temporary spending is a “use or lose” tool for addressing the budget problem—once the funds are disbursed to recipients, pulling them back becomes practically impossible. Other tools, like reserve withdrawals and cost shifts, also can be used only once, but at any time. Reducing this one-time and temporary spending allows the state to save these other tools to deploy in the future, improving budget resilience.

Introduces Proposal to Save Excess Revenues. While we have not yet seen the specific language, we understand the May Revision includes proposed statutory changes that would temporarily set aside anticipated surplus revenues for at least a year. While executing this proposal would be technically complex and involve trade-offs, we think the underlying idea is meritorious. In particular, we are in favor of the Legislature exercising caution when it allocates large surpluses—particularly those associated with revenue surges. Saving some of this surging revenue, rather than spending or committing it right away, can provide an important cushion for the state budget to weather revenue downturns. While the administration’s approach is still forthcoming, the Legislature has different options for implementing this concept.

Improves Likelihood the State Can Maintain More Core Services. We encourage the Legislature to consider the state’s budget structure and overall fiscal health when evaluating the May Revision. While the proposed budget requires difficult choices, its overall structure likely increases the Legislature’s ability to maintain core services in the future. (While there is no single definition of “core services,” we use this term to refer to the ongoing spending level committed to by the Legislature.)

Next Steps for the Legislature

How Does the Legislature Want to Address School and Community College Funding? One key question for the Legislature is deciding how to address prior-year funding for schools and community colleges. The May Revision continues to rely on a funding maneuver that would contribute to the structural budget shortfall in future years. As we described in our February report, we recommend the Legislature reject this proposal. The proposal establishes a new type of internal obligation, creates pressure for similar cost shifts in the future, and reduces budget transparency. The Legislature has other options for reducing prior-year spending that would avoid these significant downsides. For example, the Legislature could bring prior-year spending down by using funds from the Proposition 98 Reserve, funding fewer augmentations, rescinding unallocated grants, and/or making targeted reductions to existing programs.

How to Balance Trade-Offs When Reducing Ongoing Spending? The May Revision includes ongoing spending reductions that total $8 billion within a few years. (That said, nearly $3 billion of this total is attributable to reductions to state operations, which might not be achievable savings.) Some of these reductions reflect paring back planned expansions of programs, for example, in the case of child care. In other cases, the reductions reflect the elimination of programs altogether, as is the case with public health funding. Each of these decisions involve trade-offs, and some represent reductions to core service levels. Although the administration’s focus for ongoing reductions tends to be on newer programs and program expansions, there could be longer-standing programs that the Legislature wishes to revisit.

Do Any Proposals Raise Serious Concerns? While structurally the Governor has taken a prudent approach, some specific proposals raise concerns for our office. (Rejecting or reducing either of these solutions or any others would require finding equivalent alternatives in dollar-for-dollar terms.) Specifically, based on our initial review we have concerns with:

Suspension of NOL Deductions. Typically, when a business experiences a NOL, it is allowed to carry forward these NOLs and deduct them from their income in future years. This allows businesses to smooth profits and losses such that businesses with similar profits over time pay similar taxes. Without this smoothing, businesses in riskier or more innovative industries—such as the technology, motion picture, and transportation sectors—could end up paying more taxes than businesses with similar but more stable profits. As such, suspending NOL deductions would lead to a less equitable tax system. While the suspension of NOL deductions has been a go-to budget solution for decades, the frequency at which this approach has been used is now starting to raise questions. Should the Governor’s proposal take effect, the state will have disallowed NOL deductions in nearly half of years between 2008 and 2027. At this rate, it seems reasonable to ask whether suspensions have begun to meaningfully undermine the purpose of allowing NOL deductions in the first place.

Unallocated State Operation Reduction. In January, the Governor proposed a one-time, vacancy-related $762.5 million unallocated General Fund reduction across state departments. In the May Revision, the Governor modifies this January proposal by making the reduction ongoing. In addition to the January reduction proposal, the May Revision includes a new proposed $2.2 billion unallocated reduction to state operations in 2024-25 and $2.8 billion ongoing beginning in 2025-26. This effectively reduces General Fund state operations costs by 7.95 percent. In total, between the two proposals, the May Revision assumes a $3.6 billion unallocated reduction to General Fund state operations. This is a very large unallocated reduction—constituting more than 10 percent of General Fund state operations. While we think it is a meritorious endeavor for the Department of Finance to identify efficiencies in state government, we think this proposal is flawed for a couple reasons. First, the administration has not articulated a strategy for achieving efficiencies. Particularly given the administration has stated these savings would not impact existing personnel, wages, or salaries, it is difficult to imagine how this level of savings could be achieved. Second, the administration would not begin the process of identifying these savings until the fall. Waiting to identify savings until the fiscal year has already begun is likely to result in a significant erosion to assumed savings. To the extent that the administration cannot achieve the full level of assumed savings, a budgetary shortfall will carry into future years.

Is the Legislature Comfortable With the Downside Risk to Revenues? Our revenue forecast is somewhat below the May Revision across the budget window. As such, we think it is more likely than not that revenues ultimately will come in below the May Revision. That being said, we think the administration’s estimates are a reasonable basis for building the state budget. Doing so, however, would create a somewhat heightened risk that the state will face additional shortfalls next year. On the other hand, using the May Revision estimates would diminish the risk of overshooting on budget reductions now. This revenue risk might be acceptable from the Legislature’s perspective, particularly if the Legislature adopts the May Revision budget structure. Under that structure, if higher revenues fail to materialize, the budget would still have other forms of resilience to mitigate the effects.