LAO Contact

Nick Schroeder

August 23, 2024

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 5

(Highway Patrol)

On August 20, 2024, the administration submitted to our office a proposed memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the state and Bargaining Unit 5 (Highway Patrol). Section 19829.5 of the Government Code specifies that our office has ten calendar days from the date we receive a proposed MOU to review the agreement and issue an analysis of the agreement. The proposed Unit 5 agreement was submitted after the close of business for the purposes of determining our ten-day review period on August 20, 2024. As such, we consider the agreement received on August 21, 2024. Unit 5 represents rank-and-file California Highway Patrol (CHP) officers. This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement to issue an analysis of the proposed MOU. State Bargaining Unit 5’s current members are represented by the California Association of Highway Patrolmen. The administration has posted the agreement and a summary of the agreement on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website. (Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of this and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.)

Major Provisions

Term. The proposed agreement would be in effect from July 1, 2024 through June 30, 2027. This means that the agreement would be in effect for three fiscal years (2024-25, 2025-26, and 2026-27).

Statutory General Salary Increases (GSIs)

Maintains Current Law That Salary Increases Automatically Each Year by Amount Determined by Five Local Governments. For nearly 50 years, statute has compared highway patrol officers’ compensation with an average of specified elements of compensation provided to peace officers employed by five local jurisdictions. The five jurisdictions are the City and County of San Francisco; Los Angeles County; and the Cities of Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego. This statutory comparison predates the state employee collective bargaining process established by the Ralph C. Dills Act. (Prior to collective bargaining, the State Personnel Board [SPB] annually would recommend to the Legislature salary ranges for classifications.) Specifically, beginning in 1975-76, Chapter 723 of 1974 (AB 3801, Brown) required SPB to survey pay levels of officers in the five jurisdictions and to base its recommendations for highway patrol officers’ salaries each year on the estimated average salary across the five jurisdictions. Under current state law, Section 19827 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR will survey “total compensation” (including both base salaries and some other categories of compensation) provided to officers in the five jurisdictions and that highway patrol officers will receive a pay increase based on the average total compensation across the five jurisdictions regardless of whether their MOU is current or expired. The proposed agreement maintains the current methodology to determine highway patrol officer salary.

Administration Assumes Annual GSI of 4 Percent During Term of Agreement. The administration’s fiscal estimates assume that the result of the salary survey would increase Unit 5 base pay by 4 percent in 2024-25, 3.9 percent in 2025-26, and 4 percent in 2026-27. For 2024-25, the administration’s assumption is based on approved MOUs in the comparison jurisdictions, however, the final salary study has not been released. For 2025-26 and 2026-27, the administration uses a combination of approved MOUs and averaging or prior increases to reach the assumed GSI. If these pay increases were extended to excluded employees affiliated with Unit 5, the pay increases would increase annual state costs by around $300 million by 2026-27.

Other Provisions Related to Pay

Resident Post Incentive Pay. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the agreement would provide $600 per month to employees who are assigned full time to a Resident Post. The administration’s estimates assume that 123 rank-and-file employees would receive this payment and 19 excluded employees would receive the payment—increasing annual state costs by about $1.8 million. The agreement specifies that the payment would be considered compensation for purposes of retirement.

Senior CHP Officer Pay. Under the current MOU, employees with at least 18 years of service as a CHP officer receive an additional monthly differential equivalent to a percentage of base salary. The current MOU establishes a schedule with six tiers that increases the payment as employees accrue more service until they reach 25 years of service as a CHP officer. Specifically, employees who have served as a CHP officer for 18 years receive 2 percent of base salary, 19 years receive 3 percent of base salary, 20 years receive 4 percent of base salary, 21 years receive 5 percent of base salary, 22 years receive 6 percent of base salary, and 25 or more years receive 8 percent of base salary. Effective July 1, 2024, the proposed agreement would create two additional tiers to the senior CHP officer pay so that employees with 27 years as a CHP officer would receive 10 percent of base salary and employees with 28 or more years as a CHP officer would receive 12 percent of base salary. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that these seniority payments are and will continue to be extended to supervisorial classifications that are excluded from the collective bargaining process and affiliated with Unit 5. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that nearly 1,400 rank-and-file and nearly 500 excluded employees have more than 18 years of service and currently receive a seniority payment. The administration estimates that the higher tiers for employees with 27 or more years of service would apply to 180 rank-and-file employees and 80 excluded employees, increasing annual state costs by about $2.2 million. The proposed agreement specifies that the payments could continue to be considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Bilingual Pay. The proposed agreement would increase from $100 to $125 per month the monthly pay available to employees who are assigned to a command with a demonstrated need, as determined by the department, to use the employee’s bilingual skills. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that 1,165 rank-and-file and 105 excluded employees receive this pay differential. The administration estimates that the provision would increase annual state costs by $658,000. The agreement specifies that these payments would continue to be considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Motorcycle Pay. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would increase from 4 percent of monthly base salary to 5 percent of monthly base salary the payment provided to employees identified as a motorcycle rider in Category I or II who is assigned to motorcycle enforcement duty or to motorcycle instruction duty. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that about 235 rank-and-file employees and about 58 excluded employees receive this payment and that the provision would increase annual state costs by $699,000. On average, the provision would increase these employees’ monthly pay by about $200. The agreement would maintain the current policy that these payments are considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Officer in Charge (OIC) Pay. Under the current MOU, employees who are assigned to perform the duties of an OIC for six or more hours during a shift receive a differential of 5 percent of the daily rate of base pay for every eligible day. The agreement specifies that the payment would be calculated by dividing the employee’s monthly base pay by 21.667 (the average number of workdays per month) and multiply that by 7 percent. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would increase the payment from 5 percent of the daily rate of base pay to 7 percent of the daily rate of base pay. The agreement would add a new provision that specifies that the OIC payment would be paid to Unit 5 members who are assigned as an acting sergeant. The agreement specifies that the payment would continue to be considered compensation for retirement purposes. In 2023, State Controller’s Office (SCO) data indicated that 689 employees received this payment each month, on average, and cost $728,422 in total. The administration estimates that the provision would increase annual state costs by $523,000.

Field Training Officer Pay. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would increase from 5 percent to 7 percent of the daily rate of base pay paid to employees for every day in which the employee (1) trains new employees or retrains existing employees and (2) acts as a Certified Motorcycle Training Officer during a Category II training period of newly assigned motorcycle riders or the reassignment evaluation of existing Category I motorcycle riders. The agreement continues the existing provision that specifies that the pay does not apply to situations where an experienced or skilled employee is required to informally “impart his/her knowledge to a newly hired or less experienced employee.” (The payment is calculated with the same methodology as the OIC Pay, discussed above.) The agreement specifies that the payment would continue to be considered compensation for retirement purposes. The administration estimates indicate that the provision would increase annual state costs by $448,000 and benefit about 400 employees.

Reimbursement for External Vest Carrier. During the term of the agreement, the proposed agreement would allow Unit 5 members to be reimbursed once up to $200 for the cost of purchasing an external vest carrier. The agreement specifies that the department currently is testing an external vest carrier and that employees would be able to purchase an external vest carrier and receive the reimbursement after the department has approved use of the equipment. The agreement specifies that the reimbursement payment would not be considered compensation for retirement purposes. The administration’s fiscal estimate assumes that 80 percent of Unit 5 rank-and-file and supervisorial employees receive the reimbursement at some point during the term of the agreement. Specifically, the administration assumes that 60 percent of employees receive the reimbursement in 2024-25, 10 percent of employees receive the reimbursement in 2025-26, and 10 percent of employees receive the reimbursement in 2026-27. In total, the administration estimates that this provision would cost the state $1.1 million.

Detective Incentive Pay. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would provide employees who meet the necessary training requirements (as outlined in Highway Patrol Manual 100.72, Departmental Detective Program Manual) and are assigned as a full-time detective a monthly payment of $500 per month. The administration assumes that 52 rank-and-file employees and 10 excluded employees would receive this payment, increasing annual state costs by $377,000. The agreement specifies that this payment would not be considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Investigator Performance-Based Pay. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would increase from $50 per month to $250 per month the payment provided to employees who (1) are assigned to perform the duties of an investigator full time and (2) meet or exceed performance standards in all critical tasks on their annual performance appraisal. The agreement also would change this payment by making it available to employees who are on a temporary assignment for more than 30 days and are performing the duties of an investigator. The administration’s fiscal estimates assume that 126 employees receive the payment and that the provision would increase annual state costs by $307,000. The agreement would maintain the current policy that these payments are not considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Drug Recognition Evaluators (DRE) Certification Pay. CHP is the state coordinator of all drug evaluation and classification programs. One such program is the DRE certification that requires the completion of a 72-hour classroom course and 32-hour field certification course. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that 550 rank-and-file and 30 excluded employees have a DRE certification. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, employees who are, or become, certified as a DRE would receive a one-time payment of $1,500. The agreement specifies that the payment would be paid to employees within 30 days upon verification of their certification. The administration estimates this provision would result in a one-time state cost of about $883,000. The agreement specifies that this payment would not be considered compensation for purposes of retirement.

Canine Care and Maintenance Pay. The proposed agreement would increase from $156.65 per month to 4 percent of base pay per month the payment to Unit 5 members who care and maintain an assigned canine. The average monthly base pay for Unit 5 is $10,687—4 percent of which is $444. The agreement specifies that this monthly payment would be “over and above” reimbursements articulated in the Highway Patrol Manual 70.7, Departmental Canine Program Manual. The agreement specifies that the parties consider this pay to constitute extra compensation provided by a premium rate under federal law such that the payment would “need not factor into the calculation of the regular rate for overtime purposes.” In 2023, SCO data indicate that 52 rank-and-file employees and 1 excluded employee received this payment each month, on average, and that the payment totaled $96,707 for the year. The administration estimates that this provision would increase annual state costs by $187,000. The agreement specifies that the payment would continue to not be considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Paramedic Pay Increased. The current MOU provides a $50 monthly payment to employees assigned full time to perform duties of a paramedic who meet or exceed performance standards in all critical tasks on their annual appraisal. The current MOU also specifies that an employee who is assigned in an administrative capacity to perform the duties of a paramedic other than in the flight program (for example, Academy Instructors) only receive the payment while they are in that assignment. Commencing the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement would change the paramedic pay by (1) increasing the payment from $50 per month to $200 per month; (2) removing the requirement that eligible employees be assigned full time to perform paramedic duties; (3) removing the requirement that employees assigned paramedic duties in an administrative capacity only receive the payment while in that assignment; and (4) specifying that the payment is available to employees who maintain a paramedic rating/certification, notwithstanding their assignment. Under the agreement, employees who are not required to maintain a paramedic rating/certification by the department but choose to maintain such a rating/certification are responsible for any associated costs with maintaining their rating/certification. The administration’s fiscal estimates indicate that about 33 rank-and-file and 2 excluded employees receive this payment. The administration’s estimates assume that the proposed provision would not increase the number of employees who receive the payment and would increase annual state costs by $99,000. The proposed agreement specifies that the payment would not be considered compensation for retirement purposes.

Business and Travel Reimbursement. Similar to what CalHR has done with other bargaining units, the proposed Unit 5 agreement would link the state’s business and travel reimbursement policy for Unit 5 to the rates established by the U.S. General Services Administration.

Clarification of Effect of Some Payments on Retirement Benefits. There are a number of payments for which the proposed agreement would not substantially change, but would codify current practice as to whether or not the payment is considered compensation for retirement purposes. The payments that the agreement specifies are considered compensation for retirement purposes include the educational incentive pay, night shift pay, and physical performance program incentive pay. The payments that the agreement specifies are not considered compensation for retirement purposes include payments received when employees are required to conduct business telephone calls outside of their work hours and compensation received when a reimbursable services contract is canceled on short notice or when a court appearance is cancelled on short notice.

Provisions Related to Leave

Vacation and Annual Leave Caps. The current MOU limits the number of accrued hours of unused vacation or annual leave employees may carry to 816 hours. According to data from SCO, as of December 31, 2023, three Unit 5 members had vacation leave balances that exceeded this cap and two Unit 5 members had annual leave balances that exceeded this cap. The proposed agreement would raise the vacation and annual leave caps to 924 hours of unused vacation and annual leave. The proposed agreement also specifies that these leave balances would be “extended” in the event that the department cannot reduce balances for operational reasons. The agreement does not provide any parameters or definition to the conditions necessary to extend the leave balance caps and does not specify by what level the caps would be increased under qualifying circumstances.

Bereavement Leave. The proposed agreement would make changes to the state’s bereavement leave policy for Unit 5 members. Under the current MOU, employees may be asked to provide substantiation that a qualified death occurred. The proposed agreement would (1) require that such requests for substantiation must be made within 30 days of the first day of leave and (2) specify what types of documentation could be used as substantiation (for example, a death certificate). The proposed agreement specifies that, in addition to three days of paid bereavement leave, eligible employees would be able to request for an additional two days of unpaid bereavement leave and that the employee would be able to use accrued leave credits to receive pay for the two days. The proposed agreement specifies that the up to five days of bereavement leave need not be taken consecutively but must be completed within three months of the date of death.

Parental Leave. The current MOU allows for an unpaid leave of absence for female permanent employees for purposes of pregnancy, childbirth, recovery therefrom, or care for the newborn child for a period not to exceed one year. The proposed agreement would remove the limitation of the leave being available to female employees and says that the leave would be available to a “permanent employee, including a spouse or domestic partner,” for the same purposes as currently established in the MOU. The proposed agreement specifies that during the time that an employee is on parental leave, the employee would be allowed to continue their health, dental, and vision benefits; however, the cost of these benefits would be paid by the employee at the group rate.

Catastrophic Leave. The current MOU establishes a catastrophic leave policy for employees to transfer their unused leave credits to other employees under specified circumstances. The proposed agreement would make various changes to the catastrophic leave program including allowing a minimum of one hour of leave to be donated rather than the current minimum of two hours of donated leave; allowing members of the employee’s immediate family to request the use of catastrophic leave rather than the current requirement that the request come from the employee; and allowing employees in different departments to make donations of compensable leave (leave that can be cashed out upon state separation, for example, vacation or annual leave).

Call Back. If an employee were to be called back to work during their regular shift hours on a day that the employee is officially on leave credit (sick leave, vacation/annual leave, or compensated time off), the proposed agreement would create a new requirement that the employee be credited with a minimum of four hours work time.

Other Provisions

California State Payroll System Project. The proposed agreement specifies that, upon notice by the state, the parties agree to reopen only pertinent sections of the agreement needed to implement any changes required by the California State Payroll System Project.

Deletion of Provision Acknowledging Cap on Pension Level. Under state law (Sections 21362 and 21362.2 of the Government Code), an employee’s pension benefit is limited to 90 percent of final compensation for patrol members who retire directly from the state on or after January 1, 2000. The current MOU includes a paragraph that recognizes this limitation in state law. The proposed agreement would delete this paragraph from the MOU. This presumably has no material effect as the sections of law that establish the cap would not be altered.

Court Appearance Via Video or Telephone. The current MOU provides compensation requirements for employees who are required to appear for court. The proposed agreement would create a new provision related to court appearances via video or telephone. Specifically, if an employee is subpoenaed to appear for court via telephone or video, the proposed agreement would require the employee to be compensated pursuant to the court appearance and call-back provisions of the MOU. The proposed agreement also would specify that employees may be required to come into an office to utilize dedicated phone lines and other equipment to accommodate the virtual court appearance. The proposed agreement would allow the department to allow an officer to conduct a virtual court appearance from the employee’s home; however, the agreement specifies that the department would not be able to require the employee to use their personal phone or computer for the virtual appearance.

Retirement Seminar. The current MOU allows an employee aged at least 49 years to use one shift of state time, with prior approval, to attend a retirement seminar. This paid time is available to employees only once during their career. The proposed agreement would make this one-time paid time to receive retirement information available to employees aged at least 48 years and would allow the time to be used for a retirement seminar or an individualized meeting (the examples identified in the agreement are a meeting with: the California Public Employees’ Retirement System [CalPERS], Savings Plus, or a union retirement planner). As is current policy, the agreement specifies that no overtime would be allotted and no expenses would be provided to employees.

Release Time for State Civil Service Examinations. The current MOU allows Unit 5 members to participate in a state civil service examination during the employee’s work hours if the examination is scheduled during the employee’s work hours. Under the MOU, employees must give their supervisor 48-hours’ notice of the examination. The proposed agreement specifies that overtime would not be authorized in order for a Unit 5 member to participate in a civil service examination.

Continuation of Joint Labor Management Committee (JLMC). The current MOU established a JLMC to review CHP’s practice of returning injured employees to active duty. The current MOU specifies that the JLMC would conclude six months after its initial meeting. The proposed MOU would make the JLMC a standing committee with no set date to conclude its activities. The administration indicates that this JLMC improved communication between the union and the department to better assist injured employees seek proper medical aid and return to work as quickly as possible.

Continuous Appropriation. The current MOU specifies that the parties would present to the Legislature a provision to appropriate funds to cover the economic terms of the MOU through June 30, 2023. The proposed MOU specifies that the parties would present to the Legislature as part of the ratification legislation a provision to appropriate funds to cover the economic terms of the proposed agreement through June 30, 2027.

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates

Administration Attributes Some Costs to Agreement That Are Current Law. As Figure 1 shows, the administration estimates that the agreement would increase annual state costs for rank-and-file Unit 5 members by $244.5 million by 2026-27. However, $238 million of these costs are the administration’s estimated costs for the formula-driven salary costs required under current law. To determine the costs of the agreement relative to current law, we would exclude these costs—bringing the estimated ongoing fiscal effect of the agreement to $6.2 million relative to current law.

Figure 1

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|

|

Pay Increases Provided by Current Law |

— |

$77.0 |

— |

$155.1 |

— |

$238.2 |

|

Other Provisions |

— |

6.4 |

— |

6.4 |

— |

6.4 |

|

Totals |

— |

$83.4 |

— |

$161.4 |

— |

$244.6 |

LAO Comments and Recommendations

Term Length Not Consistent With Standing LAO Recommendation. The proposed agreement would be in effect for three fiscal years and would maintain the current statute to provide automatic pay increases beyond these three years even if the agreement were to expire and the parties could not agree to a successor MOU. This is not consistent with our long-standing recommendation that the Legislature only approve MOUs with terms of one or two years. The basis of this recommendation is to preserve legislative flexibility to respond to changing economic conditions.

CHP Officer Vacancy Rates

Statewide, Share of Vacant Authorized Positions Growing. For at least the past 20 years, the statewide vacancy rate consistently has been above 10 percent. In recent years, the vacancy rate has increased significantly. Comparing statewide payroll data from December 2015 with data from December 2023, the statewide vacancy rate increased 62 percent from 13 percent of positions being vacant to 21 percent of positions being vacant.

Vacancy Rates Among CHP Officers Has Grown More Than Statewide Vacancy Rates Recently. In our 2019 analysis of the current MOU, we reported that the vacancy rate among Unit 5 positions was much lower than the statewide vacancy rate with only 5 percent of authorized Unit 5 positions being vacant at the time. Since 2019, the vacancy rate among Unit 5 positions has increased significantly. In 2023, the average monthly vacancy rate among authorized Unit 5 positions was 16 percent. The vacancy rate among Unit 5 positions has grown much faster than the statewide vacancy rate. While the statewide vacancy rate grew 62 percent between December 2015 and December 2023, the Unit 5 vacancy rate between the same payroll periods grew 94 percent.

Cause of High Vacancies Among CHP Officers Not Clear. As we discuss in our March 2024 budget analysis, there are a number of reasons for authorized positions to not be filled by a department, including departments intentionally holding positions vacant to pay for rising costs of doing business; turnover in the workforce resulting from employees promoting, retiring, separating, or otherwise vacating positions; the compensation that a department is able to offer not being competitive enough in the labor market to attract qualified candidates; or the nature or location of a state job. Given the limited amount of time we have to complete our analysis, we do not know why the vacancy rate for CHP officers has grown faster than the statewide vacancy rate. It is possible that the higher vacancy rate is due to some combination of turnover and recruitment challenges.

CHP Officer Salaries

CHP Officer Salary Increases Automatically. Under current law, the state’s costs for highway patrol salary are determined by factors over which the Legislature has no control: decisions made by five local governments. The extent to which these decisions are based on changes in the cost of living or other factors is not readily known to the Legislature or the administration. Moreover, highway patrol officers currently are the only state employees in California who automatically receive adjustments to their salary ranges each year. While we have not completed an exhaustive search, we are not aware of another state that provides its highway patrol officers automatic pay increases based on compensation provided to local peace officers.

Formula Not Tied to Actual Recruitment and Retention Trends. Section 19827 explicitly states that the purpose of linking highway patrol compensation to the five local governments is to “recruit and retain the highest qualified employees.” Despite this legislative intent, the current formula does not contain any factor that adjusts pay increases based on the success or failure of CHP to actually recruit and retain employees. The growth in vacancy rates among CHP officer positions suggests that the current methodology to establish CHP officer compensation may not meet the legislative purpose of recruiting and retaining employees. However, the extent to which pay is the driving factor in the vacancy rate increase is unknown.

Formula Not Tied to Officers’ Current Locations. The five jurisdictions used in the formula were the five largest police jurisdictions in California in 1974. These jurisdictions possibly were a representative sample of the cost of living where CHP officers worked in 1974; however, as we discussed in our 2019 analysis, these five jurisdictions today represent among the most expensive regions of the state and are not where many highway patrol officers work. As we discussed in our 2024 Unit 10 analysis, the state does not currently have a uniform locality pay system that adjusts state employee pay to reflect differences in cost of living across the state. Typically, salary adjustments for other units reflect comparisons of comparable jobs across the state. As a result, often, salaries are more competitive in regions with lower costs of living, whereas salaries in more expensive regions are less competitive. In contrast, Unit 5 receives salary increases based on labor market trends in counties with high costs of living despite roughly 70 percent of Unit 5 members working in counties that are not included in the survey.

Salary Growth Increases Other State Costs. The state employer payments towards some employee benefits are determined as a percentage of pay. These types of benefits are referred to as salary-driven benefits because growth in salary increases the state’s costs for these benefits. Salary-driven benefits for Unit 5 include pension benefits, overtime, the state’s contribution to prefund retiree health benefits, and Medicare. Excluding overtime (because it varies not only by salary but also by hours of overtime worked), 2024-25 Unit 5 salary-driven benefits are equivalent to 76 percent of salary cost. This means that every $1.00 increase in CHP officer salary increases state costs by $1.76. (If overtime is included, state costs increase by an additional $0.18, on average.) Salary growth also can affect the state’s pension unfunded liabilities, which, in turn, directly affects the state’s contributions towards pensions. CalPERS assumes that payroll grows by 2.8 percent each year. Payroll is a function of salary growth and growth in positions. To the extent that salary growth contributes to payroll increasing faster than 2.8 percent in a particular year, an actuarial unfunded liability is incurred. The cost of the new unfunded liability is amortized over time and increases the state’s employer contribution rates.

Difficult to Forecast Costs. For most bargaining units, an MOU schedules specified pay increases for the duration of the agreement. This provides the state a level of certainty when developing its budget—the Legislature reasonably can forecast and prepare for these rising employee compensation costs in the state budget. From one year to the next, the state’s salaries for highway patrol officers are not known until late in the budget process—making it difficult for the Legislature to plan, establish priorities, and balance the budget during the annual budget process. For example, at the time of the May Revision of the 2018-19 budget, the administration assumed that Unit 5 would receive a GSI of 5.8 percent when it ultimately came in at 6.2 percent. The level of pay increases provided to Unit 5 pursuant to the survey can vary significantly from one year to the next. For example, the survey resulted in Unit 5 receiving a 2.9 percent GSI in 2017-18 but a 6.2 percent GSI in 2018-19. The difficulty in forecasting future salary increases is particularly problematic because, as we discuss in greater detail later, the primary funding source for CHP—the motor vehicle account (MVA)—is projected to be insolvent in the near future. Challenges in forecasting CHP employee compensation costs makes it more difficult to accurately project the MVA fund condition.

Reliance on Formula Limits Legislative Flexibility and Oversight. Formula-driven salaries limit legislative oversight of state employee compensation and hinders the Legislature’s ability to respond to unexpected fiscal challenges—like the insolvency of a major state fund. Because of this, our office recommended in 2007 that the Legislature end automatic pay raise formulas. As we indicated in that analysis, “implementing this recommendation would require the Legislature to (1) reject any proposed MOUs that include an automatic pay raise formula tied (for example) to growth in local government salaries and (2) pass legislation repealing the CHP statutory pay formula.”

Automatic Formula Has Resulted in CHP Officer Salaries Rising Faster Than Other State Peace Officers and Inflation. Figure 2 compares the growth in average base salary for Units 5, 6 (Corrections), and 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety) with the growth in inflation (measured by the California Consumer Price Index [CA-CPI]) since 1999. The three bargaining units each represent peace officer classifications. As the figure shows, Unit 7 average base pay roughly kept pace with inflation over the past two and a half decades. As we discussed in the 2007-08 Budget: Perspectives and Issues, the 2001 MOU for Unit 6 briefly tied Unit 6 salaries to Unit 5 salaries between 2001 and 2006—this parity can be seen in the figure as Unit 6 average base pay growth very closely followed growth in Unit 5 average base pay during that period. After Unit 6 salaries were decoupled from Unit 5 salaries in 2006, the salary growth moderated and today is in line with inflation growth. In contrast, after 2006, Unit 5 average base pay continued to grow much faster than inflation. While the counter factual cannot be known, Unit 5 pay may have been closer to the increases provided to other peace officers if the automatic pay formula had not been not in effect.

Formula Has Long-Standing Precedent, but It Should Be Improved or Even Repealed. In the past, other bargaining units have had formula-driven salary increases incorporated into their MOUs (as we mentioned, Unit 6 briefly was tied to Unit 5 salaries, but Unit 9 [Professional Engineers] salaries also once were determined by formula). However, these other examples were limited in their duration. The highway patrol formula, on the other hand, has determined highway patrol salaries for decades and has been referenced in statute for nearly a half-century. While we recommend the Legislature not approve automatic pay raise formulas, we recognize that changing this long-standing practice raises a variety of challenges. If repealing the statute that establishes the automatic pay increases for Unit 5 is not feasible, we recommend that the Legislature instead modify the statute to improve the survey methodologies used. Most importantly, the survey methodology should use a more representative sample of employers against which to compare state compensation. In our 2019 analysis, we discussed how the sample used in the annual survey could improve upon the existing survey.

Non-Salary Payments

Seek Justification for Providing Pay for Specified Activities or Qualifications. The proposed agreement would increase the pay received by Unit 5 members for specific activities (for example, caring for and maintaining a canine) or maintaining specific qualifications (for example, a paramedic certification). In the limited time we have to review this agreement, we cannot assess whether these pay increases are justified. We recommend that the Legislature ask the administration to provide justification for each of these pay increases.

CHP Pension Benefits

Three Sources of Revenues for Pension Systems. CalPERS administers defined pension benefits for state employees and the employees of contracting local governments. A defined benefit pension guarantees employees a level of benefit in retirement. CalPERS benefits are paid to retired employees (or their beneficiaries) from a trust fund. The trust fund has three revenue sources: returns on invested assets (accounting for 56 percent of CalPERS pension benefit funding); employer contributions (accounting for 33 percent of CalPERS pension benefit funding), which we discuss in greater detail below; and active employee contributions (accounting for 11 percent of CalPERS pension benefit funding).

Employer Contributions to Pensions Consist of Two Parts. The employer contribution to a public pension system has two distinct components, each established as a percentage of pay:

Normal Cost. The normal cost is the amount actuaries determine must be contributed to the pension system in a given year to fund the benefit earned by state employees in that year. The normal cost is developed using various actuarial assumptions including assumptions about investment returns on assets and the life expectancy of members. Under the Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act of 2013, the state has a standard—implemented through the collective bargaining process—that the state and its employees each pay one-half of the normal cost.

Unfunded Liabilities. An unfunded liability exists when the projected value of pension benefits earned to date exceeds the projected assets of the pension system. While the state shares normal cost with employees, unfunded liabilities generally are the state’s responsibility. One way that unfunded liabilities come about is when actual experience deviates from what was assumed by actuaries when they developed the normal cost. Actuaries spread (or amortize) the effect of these actuarial losses (resulting in higher costs) over a time period specified by CalPERS board policy.

Employer Contribution Rates Established by Pension Board. State law (see Article XVI of the California Constitution and Section 20120 of the Government Code) gives the CalPERS board plenary authority, fiduciary responsibility, and management and control of the pension system. This includes the authority to adopt actuarial assumptions used in actuarial valuations and to set employer contribution rates. While the Legislature may appropriate more funds than are actuarially required towards pensions (a payment referred to as a “supplemental pension payment” or SPP), the Legislature has no flexibility to appropriate an amount of money that is less than what the CalPERS board approves.

CHP Officers Earn Distinct Pension Benefit: Highway Patrol. In total there are five state pension plans administered by CalPERS. The pension benefit earned by a state employee varies by the employee’s job. State-employed peace officers earn their benefit under one of two plans: Peace Officers and Firefighters (POFF) or Highway Patrol. While all other peace officers employed by the state earn the POFF benefit, CHP officers earn the Highway Patrol pension benefit.

Pension System Mature. A pension system matures as the share of people receiving benefits (retirees and their beneficiaries) grows relative to the share of active members who are working and contributing to the system. As a pension system matures, its cash flow changes from a positive cash flow (more money coming into the system than is being paid out to beneficiaries) to a negative cash flow (more money is being paid out to beneficiaries than is coming into the system). This generally means that mature pension systems rely on some combination of selling assets or using contributions to make benefit payments. All five of the state’s pension plans (1) have a ratio of more members receiving benefits than active members contributing to the plan and (2) are becoming more mature. The Highway Patrol pension plan is among the most mature state plans with 9,951 members receiving benefits and 6,643 active members contributing (as of June 30, 2022), a ratio of 66.8 percent (active employees to retirees), compared with POFF and State Miscellaneous having a ratio of 87 percent and 86 percent, respectively. Only the State Industrial plan has a lower ratio of active employees to retirees at 65 percent.

Volatility in Mature Pension Plans. As a pension plan matures and its cashflow becomes negative, its portfolio is less able to recover from investment losses. This is because the pension system effectively has a shorter time horizon to recoup the loss before money from the portfolio is needed to pay benefits. This sensitivity to market fluctuations translates to volatility in employer contributions towards unfunded liabilities. One way to measure this volatility is to use the “asset volatility ratio,” which is equal to the market value of assets divided by the annual covered payroll. Another way to measure this volatility is to use the “liability volatility ratio,” which is equal to the accrued liability of the plan divided by the plan’s annual covered payroll. By both of these measures, the Highway Patrol pension plan is the most volatile of the state’s pension plans.

State Makes Regular SPPs to All State Employee Pension Plans Except Highway Patrol. As mentioned earlier, an SPP is when an employer contributes more than is actuarially required towards a pension plan. An SPP directly reduces existing unfunded liabilities of a pension plan. This, in turn, reduces the employer’s costs towards the plan over decades in the form of lower contribution rates. The state has made one-time SPPs to each state pension plan at various times in the past. Such one-time SPPs to the Highway Patrol plan have included the 2017-18 plan to borrow funds to make SPPs to all pension plans and SPPs required by the current MOU. However, the state regularly appropriates SPPs to satisfy General Fund constitutional debt repayments required under Proposition 2 (2014) to the four pension plans other than Highway Patrol. Highway Patrol is excluded from these Proposition 2 SPPs because Highway Patrol is funded entirely by non-General Fund state funds.

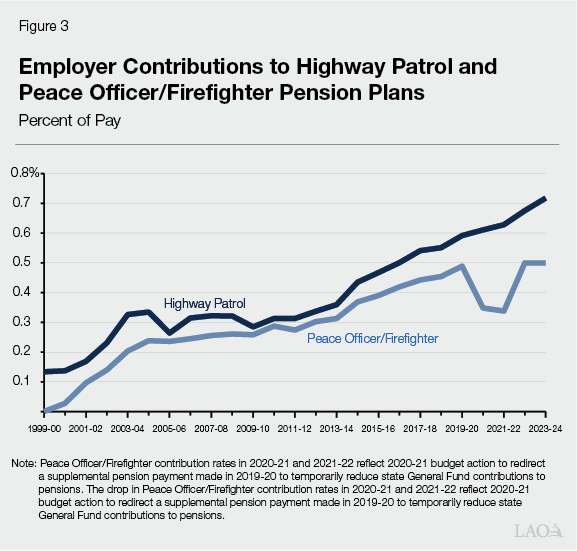

Highway Patrol Pension Employer Contribution Rates Have Grown More Than for Other Peace Officers. Figure 3 shows that the state’s contributions to fund the Highway Patrol pension plan have increased more than its contributions towards the POFF pension earned by other state peace officers. The difference in growth likely is due to a combination of the higher volatility of the Highway Patrol plan, the pay increases received by Unit 5, and the effects of the Proposition 2 SPPs that have benefited POFF but not Highway Patrol. CalPERS projects that the state’s contribution to the Highway Patrol plan will increase by an additional 2 percent of pay by 2029-30. Depending on how actual experience between now and 2029-30 deviates from actuarial assumptions (for example, investment returns), the state’s contribution could be higher or lower than currently projected.

CHP Officer Diversity

Gender and Racial Representation and Pay in State Civil Service Varies Between Classifications. In our 2022 analysis of CalHR’s budget proposal at the time, we discussed the diversity in the state workforce and the pay gap that exists in the state civil service. In that analysis, we concluded that (1) overall, the state workforce is not representative of the demographic composition of the state population; (2) there is significant variation in gender and racial diversity by classification; and (3) because compensation in state government is determined by an employee’s classification, the fact that demographic trends vary across state classifications means that compensation varies across state employees, depending on their race/ethnicity and gender. In its 2021 Women’s Earnings Report, CalHR found that women employed by the state earn 14.5 percent less than men employed by the state because jobs that tend to be filled by men are compensated more than state jobs that tend to be filled by women.

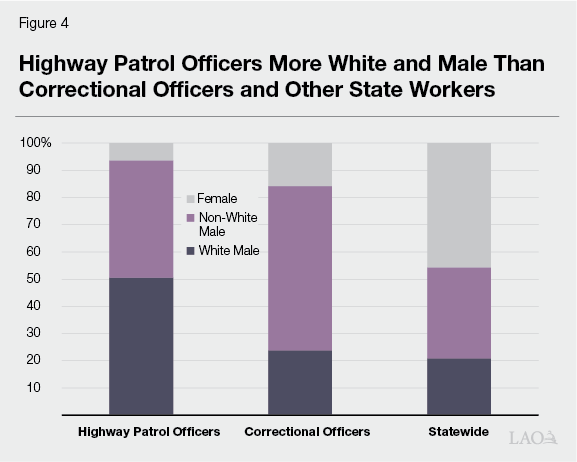

Unit 5 More Likely to Be White and Male… Peace officer jobs—like CHP officers—historically have been filled by men. As Figure 4 shows, CHP officers are less diverse than correctional officers or the statewide civil service workforce. Specifically, more than 90 percent of CHP officers are male and about one-half of CHP officers are both male and white. In contrast, correctional officers proportionately have nearly three-times the representation of women among their ranks and have a significantly larger share of non-white men. The lack of gender and ethnic/racial diversity among CHP officers means that the state’s police force that regularly interacts with the public is not representative of the public. However, the trend seems to be moving towards CHP officers becoming more diverse. For example, the share of CHP officers who are white and male has decreased from 61 percent in 2017 to 51 percent in 2024. Further, in 2024, only 20 percent of CHP cadets were identified as white and male. Higher levels of diversity among graduating cadets will lead to higher levels of diversity among CHP officers in future years.

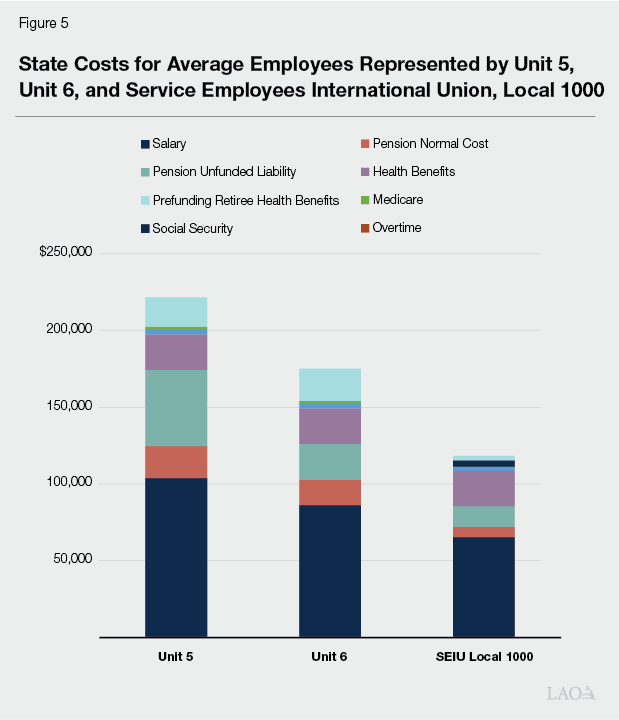

…And Compensated More. While there are classifications that receive significantly higher levels of compensation than CHP officers, Bargaining Unit 5 is the highest compensated state peace officer bargaining unit and is among the higher paid bargaining units overall statewide. Figure 5 shows that the state’s costs to compensate CHP officers is greater than for state correctional officers and roughly twice the cost for the state employees represented by Service Employees International Union, Local 1000 (SEIU Local 1000)—a union that represents roughly one-half of rank-and-file state employees. While the jobs performed by employees represented by SEIU Local 1000 and CHP officers are dramatically different, the comparison helps put CHP officer compensation into the context of the “typical” state employee. Comparing Unit 6 with Unit 5 allows for a comparison between peace officer classifications. As the figure shows, total compensation costs for Unit 5 is significantly larger than Unit 6, but this is driven in large part by the state’s payment to pension unfunded liabilities rather than significant differences in take home pay.

MVA

MVA Is One of Hundreds of Special Funds. The state’s primary operating fund is the General Fund. In addition to the General Fund, the state has hundreds of special funds that serve as the operational funding source for programs with specific purposes. The primary funding source for special funds often are fees for service. Some special funds operate at a surplus while others have significant challenges due to some combination of declining revenues and increasing expenditures. For many departments, the largest category of expenditure is related to employee compensation. For departments funded by a challenged special fund, growth in employee compensation costs beyond what currently is projected can further weaken the special fund’s condition.

MVA Is Primary Funding Source for CHP. The uses of most MVA revenues are constitutionally limited to the administration and enforcement of laws regulating the use of vehicles on public highways and roads, as well as certain transportation activities. While the MVA supports various state programs, it is the primary funding source for CHP and the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). For 2024-25, MVA revenues are estimated to total about $4.9 billion. Of this amount, nearly $4.3 billion (87 percent) is projected to come from vehicle registration fees.

MVA Has Had Challenges Over the Years. As we indicated in our 2019 MOU analysis and our 2024 budget analysis, the MVA has experienced periodic deficits and risks of insolvency over the past couple of decades. In response, the state has taken various actions to shore up the fund. Some of these past solutions provided temporary relief, such as the state making a one-time repayment of loans that previously were provided from MVA to the General Fund and delaying repayments to the General Fund for the 2017-18 SPP made using borrowed funds (which temporarily reduced MVA expenditures but created additional out-year liabilities). Other solutions provided longer-term solutions, including (1) ending a previous practice of transferring about $90 million annually from MVA to the General Fund; (2) authorizing vehicle registration fees to be adjusted annually based on the percent change in the CA-CPI to account for inflation; (3) shifting certain programs from MVA to other fund sources; and (4) shifting away from using up-front cash from MVA to pay for CHP’s and DMV’s facility needs.

Fund Rapidly Heading for Insolvency. As we discussed in our 2024 analysis, despite previous efforts to address MVA’s condition, the severity of the fund’s imbalance is expected to become worse in the near term, with expenditures growing about 1 percent faster than revenues over the next several years. Due to this imbalance, MVA is expected to fully exhaust its reserves and become insolvent in 2025-26. If left unaddressed, expenditures would continue to outpace revenues, resulting in a negative fund balance of $1.4 billion in 2028-29.

Employee Compensation a Major Cost Driver. One of the major factors that has contributed to the structural imbalance of MVA is rising employee compensation costs. These costs have been driven by both increases to staffing levels and growing salary and benefit costs at CHP. While the Legislature has flexibility to adjust CHP staffing levels to some degree, the autopilot pay increases and CalPERS’ authority to set employer pension contribution rates severely limits the Legislature’s flexibility to adjust CHP compensation costs in response to changing economic conditions.

Agreement Increases Compensation Costs, Adds to Risk for MVA. Expenditures towards CHP account for about 62 percent of total MVA expenditures. The proposed agreement would increase CHP compensation by maintaining the existing autopilot pay increases and increasing various pay differentials. The higher compensation levels established by the agreement would create additional pressure for the MVA as expenditures continue to rise. The lack of flexibility under the proposed agreement for the Legislature to adjust CHP compensation levels limits the Legislature’s flexibility reduce expenditures to stabilize the MVA.

Governor Proposes New Spending From MVA With No Plan to Address Solvency. Through this agreement, the Governor proposes new spending from the MVA. However, the Governor offers no proposal to address the structural deficit of the fund that (at the time of May Revision) the Department of Finance projected would become insolvent in 2025-26. The administration asserts that the projected MVA shortfall does not need to be addressed today because the fund is projected to be solvent through the end of 2024-25. The administration also indicates that it will continue to explore options to address the structural shortfall of the fund and will continue to use the budget process to ensure that the MVA remains solvent in the budget year. As the Legislature considers the proposed MOU, we recommend asking the administration to provide details as to when it will bring forward a plan to bring the MVA into solvency.