LAO Contact

August 26, 2019

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 5 (Highway Patrol)

On August 16, 2019, the administration submitted to the Legislature a proposed memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the state and Bargaining Unit 5 (Highway Patrol). Compensation costs for Unit 5 members and their managers are paid mostly from the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA). This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. State Bargaining Unit 5’s current members are represented by the California Association of Highway Patrolmen (CAHP). The administration has posted the agreement and a summary of the agreement on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website. (Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of this and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.)

The proposed agreement would be in effect for four years. We recommend that the Legislature consider this agreement in the broader context of the state budget because the agreement (1) has significant short- and long-term effects on the MVA—a fund that recently was projected to be insolvent, and (2) interacts directly with the enacted version of the 2019‑20 budget.

Unit 5 members currently work under the terms of an expired MOU. The expired agreement went into effect July 3, 2010 and expired July 3, 2018. Pursuant to the Ralph C. Dills Act (Dills Act), the provisions of an expired MOU generally continue to be in effect beyond the agreement’s expiration. Although the Brown Administration bargained some changes (referred to as addenda) to the 2010 agreement—including a 2012 addendum extending the expiration of the agreement to 2018—the bulk of the expired agreement was bargained by the Schwarzenegger Administration in 2010.

Major Provisions of Proposed Agreement

Term. The agreement would expire June 30, 2023, meaning that it would be in effect for four years. The agreement includes provisions with new ongoing effects on the state’s budget in five fiscal years (from the current year—2019‑20—through 2023‑24). The long duration of the proposed agreement is not consistent with our 2007 recommendation that the Legislature only approve tentative agreements that have a term of no more than two years.

Salary and Pay

Maintains Current State Law That Annual Salary Increases Be Determined by Five Local Governments. For more than 40 years, statute has compared highway patrol officers’ compensation with an average of specified elements of compensation provided to peace officers employed by five local jurisdictions. The five jurisdictions are Los Angeles County and the Cities of Los Angles, Oakland, San Diego, and San Francisco. The statutory comparison predates the state employee collective bargaining process established by the Dills Act. (Prior to collective bargaining, the State Personnel Board [SPB] annually would recommend to the Legislature salary ranges for classifications.) Specifically, beginning in 1975‑76, Chapter 723 of 1974 (AB 3801, Brown) required SPB to survey pay levels of officers in the five jurisdictions and to base its recommendations for highway patrol officers’ salaries each year on the estimated average salary across the five jurisdictions. Under current state law, Section 19827 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR will survey “total compensation” (including both base salaries and some other categories of compensation) provided to officers in the five jurisdictions and that highway patrol officers will receive a pay increase based on the average total compensation across the five jurisdictions regardless of whether their MOU is current or expired.

The proposed agreement maintains the current methodology to determine highway patrol officer compensation. This provision is not consistent with our 2007 recommendation that the Legislature end the practice of automatic pay raise formulas. The administration assumes that highway patrol officers’ salaries will increase 3.9 percent in 2020‑21, 4.3 percent in 2021‑22, and 5.3 percent in 2022‑23. Because the actual amounts are wholly dependent on decisions made by the five local governments, the actual pay increases received during the term of the agreement could be higher or lower than the administration assumes.

Limits 2019‑20 Salary Increase to 3 Percent . . . Based on the compensation survey of the five local governments, the highway patrol officers’ pay increased about 3.5 percent on July 1, 2019. The proposed agreement temporarily reduces this pay increase to 3 percent beginning the pay period following ratification of the agreement.

. . . Redirecting Any Amount Above 3 Percent to Retirement Benefits . . . The agreement temporarily redirects any amount of the 2019‑20 salary increase above 3 percent to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) as an employer contribution to employee pension benefits. Based on the most recent compensation study, this means that about one-half of 1 percent of pay would be redirected from employee salaries to the state’s contribution to CalPERS. This contribution would be in addition to what the state and employees otherwise would contribute to CalPERS and would reduce the pension plan’s unfunded liability. Redirecting this portion of salary also produces short-term savings for the state because—while the about one-half of 1 percent of pay is paid to CalPERS—the state does not pay salary-driven benefit costs (like pension and Medicare contributions) associated with the redirected pay.

. . . But Redirects Amount Back to Salary Upon Expiration of Agreement. On July 1, 2023—after the agreement expires—the one-half of 1 percent of pay would be redirected back to employees as a salary increase. As such, beginning July 1, 2023—assuming a subsequent agreement does not extend the redirection—the state would begin paying salary-driven benefit costs on the one-half of 1 percent of pay.

Pension Benefits

Conforms Benefit Structure Outlined in Agreement to State Law. The Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act of 2012 (PEPRA) made various changes to pension benefits earned by employees first hired by the state after January 1, 2013. These changes included substantially reduced benefit formulas and changes to the number of years of compensation that are considered as part of an employee’s final compensation for purposes of calculating the employee’s pension benefit. Unit 5 members hired after January 1, 2013 have been subject to PEPRA; however, the language of the expired MOU does not reflect the new benefit structure. The proposed agreement would conform the labor agreement to reflect state law. (This change, however, does not affect any officers’ compensation or pension benefits.)

Increases Patrol Officer Employee Contributions by 3 Percent of Pay by End of Agreement. Under PEPRA, the state has a “standard” that employees pay one-half of the normal cost of the pension benefit. According to the most recent CalPERS actuarial valuation (using data as of June 30, 2018), the total normal cost for highway patrol officers ranges from 23.6 percent of pay and 31 percent of pay, depending on a highway patrol officer’s date of hire. CalPERS reports that the blended total normal cost—the average total normal cost for state highway patrol officers—is 29.9 percent of pay. The current highway patrol officer contribution to CalPERS is 11.5 percent of pay. The agreement increases employee contributions over the course of the agreement by 1 percent of pay each year starting in 2020‑21. Consequently, employee contributions would be 12.5 percent of pay in 2020‑21, 13.5 percent of pay in 2021‑22, and 14.5 percent of pay in 2022‑23. In order for officers to be paying one-half of the blended normal cost, employee contributions would need to increase by 0.5 percent of pay in 2023‑24—after the proposed agreement expires, which may require statutory changes to take effect without it being agreed to in a subsequent agreement. The administration does not estimate the fiscal effect of the agreement beyond 2022‑23.

Establishes Conditions Under Which Cadet Employee Contributions Increase. Highway patrol cadets—people who are in the academy training to become highway patrol officers—are members of the State Miscellaneous retirement plan. The total normal cost for State Miscellaneous ranges from 15.2 percent of pay to 17.6 percent of pay, depending on date of hire, and the blended State Miscellaneous total normal cost is 16.8 percent of pay. Under the expired agreement, cadets contribute 8 percent of pay towards their pensions. The proposed agreement establishes conditions under which cadet pension contributions would increase. Specifically, if the normal cost for State Miscellaneous increases by 1 percent or more, cadets would be required to increase their contributions. The administration’s fiscal estimates assume that cadets’ contributions will increase by 0.25 percent of pay in 2020‑21 to a total employee contribution of 8.25 percent of pay. How the administration arrived at this assumption is unclear. If the total blended normal cost grows in the next valuation to trigger an increase in cadet contributions, the increase would need to be more than 0.25 percent of pay to ensure that employees are paying one-half of normal cost. One-half (rounded to the nearest quarter percent) of the current blended normal cost would require employees to contribute 8.5 percent of pay—0.5 percent of pay higher than their current contributions.

Requires MVA to Make $100 Million Supplemental Pension Payment Over Four Years. In each of the four fiscal years of the agreement (2019‑20, 2020‑21, 2021‑22, and 2022‑23), the agreement would require the MVA to contribute $25 million to CalPERS—totaling to $100 million over the four years. This contribution would be a supplemental contribution to the highway patrol retirement plan, meaning that it is in addition to whatever contribution the state would make to CalPERS on behalf of highway patrol officers. The agreement specifies that “in the sole discretion” of the Director of Finance, the $25 million supplemental payments for 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 can be deferred one year if projected revenues at the May Revision are “insufficient to fully fund existing statutory and constitutional obligations, existing fiscal policy, and the costs of providing the aforementioned supplemental pension payments.”

Redirects General Fund Supplemental Pension Payment Appropriated in 2019‑20 Budget. Chapter 33 of 2019 (SB 90, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) appropriated $265 million from the General Fund in 2020‑21 as a supplemental pension payment to state pension plans. The law specified that the money would be apportioned among the state employee pension plans in proportion to each plan’s share of the state’s total General Fund pension contribution to CalPERS. Because highway patrol compensation is paid entirely from special funds, none of the money appropriated under Chapter 33 will be apportioned to the highway patrol pension plan under current law. The agreement would redirect $243 million of the $265 million 2020‑21 General Fund appropriation to the highway patrol pension plan.

Retiree Health Benefits

Implements Benefit Structure and Vesting Period for Future Employees Already in Place for Other State Employees. Under the Brown Administration, the state adopted a policy to reduce retiree health benefits for future employees through the collective bargaining process. (For a summary of the changes, refer to our March 16, 2015 report.) Unit 5 is the last bargaining unit to adopt the lower benefit for future employees. Under the agreement, Unit 5 members first hired after January 1, 2020 will earn the less generous benefits and be subject to the longer vesting period to be eligible for the benefits.

Maintains Past Contributions Established In Lieu of Pay Increases. Since 2010, the state and Unit 5 have agreed in a number of instances to redirect portions of pay increases that Unit 5 members otherwise would have received as a result of the annual compensation study to make contributions to retirement benefits. As Figure 1 shows, the parties periodically agreed to redirect this money to prefund retiree health benefits. The proposed agreement would maintain the amount of money that is redirected from pay to retiree health benefits at 3.4 percent of pay. In the past, these contributions have been based on base pay. The agreement would specify that this contribution would instead be based on pensionable compensation, which is higher than base pay because it includes pay differentials.

Figure 1

Tracking Changes to State and Employee Contributions to

Prefund Unit 5 Retiree Health Benefits

|

Fiscal Year |

Calculated as a Percent of . . . |

State Contribution |

Employee Contribution |

Total Contribution |

|

|

In Lieu of Statutory Salary Increase |

Direct State Payment |

||||

|

2009‑10 |

Base Pay |

0.5% |

— |

0.5%a |

1.0% |

|

2010‑11 |

1.5b |

— |

0.5b |

2.0b |

|

|

2011‑12 |

—b |

— |

—b |

—b |

|

|

2012‑13 |

—b |

— |

—b |

—b |

|

|

2013‑14 |

1.9 |

2.0%c |

— |

3.9 |

|

|

2014‑15 |

3.4d |

2.0 |

0.5e |

5.9 |

|

|

2015‑16 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

7.8 |

|

|

2016‑17 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

7.8 |

|

|

2017‑18 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

7.8 |

|

|

2018‑19 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

7.8 |

|

|

2019‑20 |

3.4 |

3.9 |

0.5 |

7.8 |

|

|

2020‑21f |

Pensionable Compensation |

3.4 |

3.4 |

— |

6.8 |

|

2021‑22 (and beyond)f |

3.4g |

3.4g |

—g |

6.8 |

|

|

aMemorandum of understanding addendum temporarily suspended contribution to prefund retiree health benefits through 2013‑14 and instead redirected contributions towards pensions. bEmployee contribution began January 2010. cEstablished to “match” the combined employee and employer pensions contributions that had been established through temporary redirection of retiree health contributions. dRedirected 1.5 percent from pension contributions. eRedirected from pension contributions. fProposed under tentative agreement now before the Legislature. gEstimated 50/50 percentage and may be adjusted each year no more than 0.5 percent of pensionable compensation. |

|||||

Maintains State’s Direct Payment Contributions. In the past, the state and Unit 5 have agreed that the state contribute a specified percentage of pay—in addition to the contributions that were in lieu of a pay increase discussed above—to prefund Unit 5 retiree health benefits. As shown in Figure 1, the agreement would require the state to contribute 3.4 percent of pensionable compensation to prefund retiree health benefits. In total, the agreement would require 6.8 percent of pay to be contributed to prefund retiree health benefits.

Allows for State and Employee Contributions to Fluctuate if Normal Cost Changes. Beginning July 1, 2021, the agreement would allow the state and employee contributions to increase or decrease by no more than 0.5 percent of pay in any given year. Specifically, the contributions would change if “the actuarially determined total normal costs increase or decrease by more than half a percent from the total normal cost contribution percentages in effect at the time.” The annual valuation of the state’s retiree health liabilities expresses the normal cost of the benefit as a dollar amount—not a percentage of pay. Accordingly, the administration and CAHP seemingly would need to agree to how to calculate normal cost as a percentage of pay in each year before the contributions change.

Other Major Provisions

Leave Cash Out. To the extent authorized by department directors, the proposed agreement would allow employees to cash out up to 80 hours of vacation or annual leave each year. These leave cash outs are subject to Medicare payroll taxes but do not affect employees’ pension benefits. The administration assumes that departments will not receive additional budgetary resources to pay for these cash outs.

Allows for Alternate Work Schedules. The agreement would allow California Highway Patrol (CHP) to establish an alternate work week so long as the department is able to meet its mission and a majority of affected officers agree. If an alternate work week schedule is instituted in an area, the agreement requires all road patrol officers in the area to participate.

Creates Role for Director of Finance to Open Agreement. In addition to the role created for the Director of Finance with regards to the supplemental pension payments from the MVA, the agreement also gives the Director the “sole discretion” to determine if “projected state revenues are insufficient to fully fund existing statutory and constitutional obligations, existing fiscal policy, and the costs of providing compensation pursuant to section 19827.” If the Director determines that there are insufficient revenues, the agreement would be reopened and the parties would meet—the provisions of the agreement would remain in effect until the parties agreed to an alternative. (This language is similar to language that also is included in the proposed agreements with Unit 7 and is similar to provisions in the 2019‑20 budget package, which we discuss in our report The 2019‑20 Budget: Overview of the California Spending Plan.)

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

Administration Attributes Some Costs to Agreement That Are Current Law. As Figure 2 shows, the administration estimates that the agreement could increase state costs by $256.5 million by 2022‑23. However, $222.9 million of these costs are the administration’s estimated costs for the formula-driven salary costs required under current law. To determine the costs of the agreement relative to current law, we would exclude these costs—bringing the estimated fiscal effect of the agreement to $34 million in 2022‑23. Further, (1) the administration assumes that the fiscal effects of the 80-hour leave cash out and employees contributing more towards their pensions would have no effect on the state’s appropriations and (2) the $25 million supplemental payment in 2022‑23 is one time. Accordingly, the administration estimates that the agreement would increase ongoing annual state costs by about $2 million beginning in 2022‑23 relative to current law.

Figure 2

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

|

Salary increases pursuant to current law |

— |

$61.6 |

$132.2 |

$222.9 |

|

80‑hour leave cash outa,b |

$25.4 |

26.4 |

27.6 |

29.0 |

|

Supplemental pension payment from MVA |

25.0 |

25.0 |

25.0 |

25.0 |

|

Retiree health contribution |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

Redirecting portion of pay to pensions |

‑1.0 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.8 |

‑0.3 |

|

Increased employee pension contributionsa |

— |

‑7.1 |

‑14.5 |

‑22.3 |

|

Totals |

$49.4 |

$107.1 |

$171.5 |

$256.5 |

|

aAdministration assumes these costs or savings will not affect state appropriations. bEstimates the maximum possible cost to the state. Actual cost depends on how many employees cash out leave and how much leave they cash out. MVA = Motor Vehicle Account. |

||||

Does Not Reflect Increased Costs Required by Agreement That Occur Beyond 2023‑24. The administration estimated the costs only for the time that the agreement is in effect. Accordingly, the administration did not estimate costs in 2023‑24 resulting from the agreement. However, the agreement would require new costs in 2023‑24 that should be accounted for. Specifically, when the one-half of 1 percent of pay is redirected from pensions to salary, the state’s costs will increase by about $1 million in 2023‑24. However, in the absence of this agreement, these costs would be incurred under current law in 2019‑20 as part of the 2019‑20 formula-driven salary increase.

LAO Assessment

Legislative Authority

Legislature Has the Authority to Reopen Agreement. The agreement suggests that the Director of Finance has sole discretion to determine if there are sufficient funds to pay for an agreement. For clarification, under the Dills Act and the Legislature’s constitutional power of the purse, the Legislature always has the authority to appropriate in the annual budget act an amount of money that is less (or more) than what would be necessary to fund a scheduled compensation increase established under a ratified agreement. If the Legislature determines that there are insufficient revenues in a given year, the Legislature may choose not to appropriate funds for a pay increase scheduled under a ratified agreement. In this case, the pay increase may not go into effect and either the union or Governor may reopen negotiations on all or part of the labor agreement.

Automatic Compensation Increases

Highway Patrol Salary Increases Automatically. The state’s costs for highway patrol salary are determined by factors over which the Legislature has no control. Specifically, five local governments determine the state’s costs. Highway patrol officers currently are the only state employees in California who automatically receive adjustments to their salary ranges each year. Although we did not have time to do an exhaustive search, we could not find another state that provides its highway patrol officers automatic pay increases based on compensation provided to local peace officers.

Difficult to Forecast Costs. For most bargaining units, the MOU schedules specified pay increase for the duration of the agreement. This provides the state a level of certainty when developing its budget—the Legislature reasonably can forecast and prepare for these rising employee compensation costs in the state budget. From one year to the next, the state’s salaries for highway patrol officers are not known until late in the budget process—making it difficult for the Legislature to plan, establish priorities, and balance the budget during the annual budget process.

As Figure 3 shows, the annual salary increases have varied over the years. As we will discuss in greater detail below, this creates a particular challenge for the state when highway patrol officers predominantly are paid from the MVA—a state fund that recently was on the path to insolvency. Ultimately, salary growth for highway patrol officers is determined by decisions made by five local governments based on local circumstances without regard for the state’s fiscal condition.

Figure 3

Highway Patrol Salary Increases

|

2019‑20 |

3.0% |

|

2018‑19 |

6.2 |

|

2017‑18 |

2.9 |

|

2016‑17 |

4.9 |

|

2015‑16 |

0.4 |

|

2014‑15 |

6.0 |

|

2013‑14 |

4.0a |

|

2012‑13 |

— |

|

2011‑12 |

—b |

|

2010‑11 |

—c |

|

2009‑10 |

—c |

|

2008‑09 |

4.1 |

|

2007‑08 |

6.1 |

|

2006‑07 |

5.7d |

|

2005‑06 |

5.6 |

|

2004‑05 |

6.8 |

|

2003‑04 |

7.7e |

|

aCompensation survey from 2013 found that Unit 5 compensation was 5.9 percent lower than the five surveyed local jurisdictions. Pursuant to a June 19, 2013 MOU addendum, Unit 5 members received a 4 percent GSI in 2013‑14 and the remaining 1.9 percent was redirected to prefund OPEB. bEffective January 2012, employees at the “top step” of their salary range received a 2 percent salary increase. cIn August 2009, the state and CAHP agreed to amend the 2006‑2010 MOU and the Legislature and Governor approved Government Code Section 22944.3 specifying that “any amount that would otherwise be used to permanently increase compensation pursuant to Section 19827, effective July 1, 2009, and on July 1, 2010, shall instead be used to permanently prefund post‑employment health care benefits for patrol members. The amount used to prefund benefits relative to any increases under the survey methodology effective July 1, 2010, shall not exceed 2 percent.” The 2010‑2013 MOU specified that these funds be redirected from OPEB to pension benefits. Pursuant to the 2010‑13 MOU, beginning in 2013‑14, the state contributes 2 percent of pay towards OPEB. dUnit 5 members also received a 3.5 percent stipend beginning in 2006‑07 as compensation for pre‑ and post‑shift activities that are compensable under federal law. eEmployees agreed to Personal Leave Program—reducing their pay by 5 percent for 12 months. MOU = memorandum of understanding; GSI = general salary increase; OPEB = other post‑employment benefits; and CAHP = California Association of Highway Patrolmen. |

|

Formula Not Tied to Actual Recruitment and Retention Trends. Section 19827 explicitly states that the purpose of linking highway patrol compensation to the five local governments is to “recruit and retain the highest qualified employees.” Despite this legislative intent, the current formula does not contain any factor that adjusts pay increases based on the success or failure of CHP to actually recruit and retain employees. For example, the pay increase calculated by the formula would be the same if 20 percent of the highway patrol officer positions were vacant across the state or none of the positions were vacant. Currently, the vacancy rate among Unit 5 positions is low—about 5 percent of authorized Unit 5 positions are vacant compared with about 15 percent of positions across state government being vacant.

Formula Not Tied to Officers’ Current Locations. The five jurisdictions used in the formula were the five largest police jurisdictions in California in 1974. These jurisdictions may have served as a good proxy in the past to assess how much highway patrol officers should be paid to reflect the cost of living where they worked; however, as we discuss in greater detail in the next section, these five jurisdictions today represent among the most expensive regions of the state and are not where many highway patrol officers work.

Limits Legislative Flexibility and Oversight. For the reasons discussed above, formula-driven salaries limit legislative oversight of state employee compensation and hinders the Legislature’s ability to respond to unexpected fiscal challenges. Because of this, our office recommended in 2007 that the Legislature end automatic pay raise formulas. As we indicated in that analysis “implementing this recommendation would require the Legislature to (1) reject any proposed MOUs that include an automatic pay raise formula tied (for example) to growth in local government salaries and (2) pass legislation repealing the CHP statutory pay formula.”

Formula Has Long-Standing Precedent. In the past, other bargaining units have had formula-driven salary increases incorporated into their MOUs. However, these other examples were limited in their duration. The highway patrol formula, on the other hand, has determined highway patrol salaries for decades and has been referenced in statute for 44 years. While ideally the Legislature would not approve automatic pay raise formulas, the weight of precedent likely makes rejecting the Unit 5 formula difficult. Recognizing this challenge, in the next section, we discuss how changing the sample used in the survey could improve the existing formula.

Salary Survey Methodology

Setting Compensation Levels for Statewide Classification Challenging. The cost of living in California varies significantly by region. Employees in the same occupation often earn higher levels of compensation in higher cost of living regions in the state. The state employs people in each county with about two-thirds of the state workforce in a county other than the County of Sacramento. In many cases—like Unit 5—the state employs people in the same classification in both high and low cost of living regions of the state. As a result, the state has (among other considerations) two competing priorities when determining an appropriate level of compensation for a classification. One priority is for the state to be a competitive employer in a region’s labor market by offering a compensation package that allows the state to recruit and retain employees. The second competing priority is to limit the amount of regional difference within a classification in order to prevent state employees from consistently transferring to higher paid regions of the state. As we discuss below, the current formula used to establish Unit 5 compensation establishes the state’s highway patrol officer compensation based on some of the highest cost regions of the state. As such, the formula effectively pays all highway patrol officers as if they worked in a high cost of living region. However, many officers work in regions far less expensive than the five local jurisdictions.

CHP Officer Spread Throughout the State. CHP officers are located in all regions of the state and, because of this, face varying costs of living. The most important driver of differences in the cost of living across regions is housing costs. Housing is the single largest expenditure category for most households, usually making up more than one-third of all spending. Housing costs also vary significantly across regions of the state, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Highway Patrol Officers Work in Regions

With High and Low Housing Costs

|

Region |

Officers |

Home Price |

|

San Francisco Bay Area |

978 |

$915 |

|

Southern California |

1,976 |

536 |

|

San Diego |

405 |

592 |

|

Greater Sacramento |

959 |

451 |

|

San Joaquin Valley |

769 |

263 |

|

Rest of state |

1,143 |

357 |

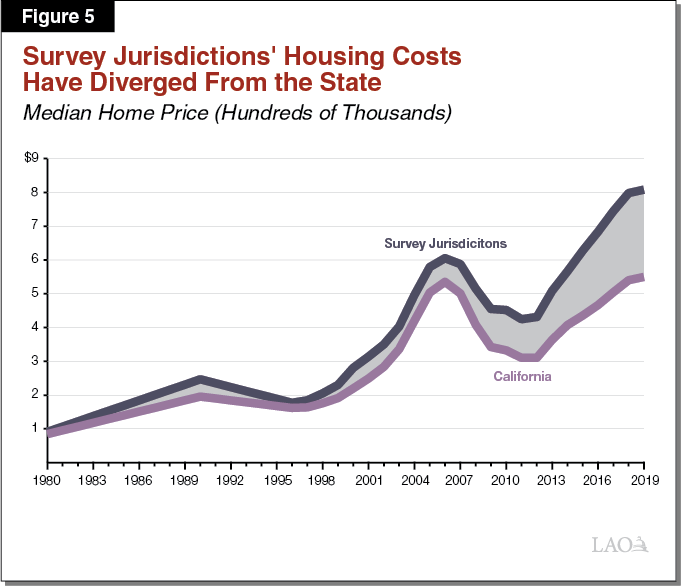

Cost of Living in Compensation Survey Jurisdictions Is Not Representative of Costs Faced by Many Highway Patrol Officers. The typical home in places that highway patrol officers are located (weighted by the number of officers in each location) costs about $520,000—just slightly less than the statewide median of $550,000. In contrast, the typical home in the five jurisdictions used for the compensation survey costs about $800,000. As Figure 5 shows, decades ago, when the survey was first adopted, housing costs in the five jurisdictions were about in the line with the rest of the state, but they have since diverged significantly.

While we do not know if salaries in these five jurisdictions similarly have diverged from the salaries earned by peace officers in other regions of the state, housing costs demonstrate the costs faced by peace officers earning the salaries in the five jurisdictions and likely reflect salary pressures in these jurisdictions.

Adding Jurisdictions to the Compensation Survey Could Make It More Representative. Adding some lower-cost jurisdictions to the compensation survey could make the jurisdictions in the survey better reflect the living costs—and likely the labor markets—faced by a typical highway patrol officer. For example, if the County of Sacramento and the Cities of Bakersfield, Fresno, Riverside, and Stockton were added to the survey, the average home price across all the survey jurisdictions (including the five existing jurisdictions) would be $560,000—just about even with the statewide norm. This analysis assumes, however, that compensation changes in these jurisdictions have mirrored changes in the cost of living. If the Legislature wished to pursue such changes to the survey, further analysis about these jurisdictions’ compensation decisions would be required.

MVA

MVA Is One of Hundreds of Special Funds. The state’s primary operating fund is the General Fund. In addition to the General Fund, the state has hundreds of special funds that serve as the operational funding source for programs with specific purposes. The primary funding source for special funds often are fees for service. Some special funds operate at a surplus while others have significant challenges due to some combination of declining revenues and increasing expenditures. For many departments, the largest category of expenditure is related to employee compensation. For departments funded by a challenged special fund, growth in employee compensation costs beyond what currently is projected can further weaken the special fund’s condition.

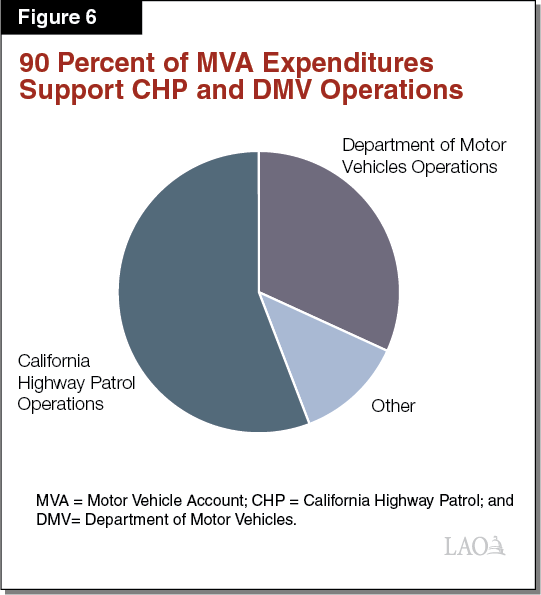

Most MVA Expenditures Pay for CHP and Department of Motor Vehicle (DMV) Operations. In 2019‑20, the MVA is expected to have $4.2 billion in expenditures. As Figure 6 shows, CHP and DMV operations account for 90 percent of the MVA’s expenditures. Most of the two departments’ expenditures from the MVA are expected to pay for employee compensation. Specifically, the CHP expects to spend about $1.8 billion MVA funds on employee compensation and DMV expects to spend about $890 million MVA funds on employee compensation.

MVA Has Had Challenges In Recent Years. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures exceeded combined revenues and transfers. For example, the MVA faced an operational shortfall in 2015‑16 of about $300 million, which was addressed through the one-time repayment of $480 million in loans that were previously made from the MVA to the General Fund. In 2016‑17, the MVA faced an operational shortfall of roughly the same magnitude and possible insolvency in 2017‑18. In order to address this shortfall and help maintain the solvency of the MVA, the Legislature increased revenues into the account by increasing the base vehicle registration fee by $10 in 2016 and indexing it to the consumer price index.

Legislature Took Recent Action to Prevent MVA From Becoming Insolvent. As we discussed in our February 2019 analysis, the MVA began the year facing a 2018‑19 operational shortfall of almost $400 million. Without corrective action, the MVA likely would have again experienced an operational shortfall in 2019‑20 and potentially have become insolvent in the future. In order to help address the MVA’s solvency, as well as increased MVA expenditures in the current year (such as a net increase of $242 million for DMV to process federally compliant driver licenses and identification cards), the 2019‑20 budget includes various actions intended to benefit the MVA in the near term (such as suspending a transfer of revenues from the MVA to the General Fund and delaying facility projects). After these corrective actions, the administration projects that the fund will have a reserve of about $100 million in 2022‑23 (this projection also assumes that additional future spending—about $50 million—proposed by the Governor is approved).

MVA Might Be Less Stable Than Assumed . . . The administration’s projected MVA fund balance assumes that (1) highway patrol officers receive a 3 percent salary increase each year and (2) DMV’s payroll costs grow 2 percent each year. These assumptions probably do not accurately predict costs under current law. For example, in estimating the costs of the Unit 5 agreement, the administration assumes that the statutory formula-driven pay increases will exceed 3 percent each year. In addition, the 2 percent growth at DMV may underestimate salary growth and growth in CalPERS pension contributions. It is possible that—under current law—the MVA already is on a path towards an operational shortfall within the next few years.

. . . And Could Be Further Weakened by Labor Agreements. Any growth in CHP or DMV compensation above current assumptions could weaken the MVA fund condition. Based on the administration’s estimates of the Unit 5 agreement, the proposed agreement could increase state annual costs by tens of millions of dollars by 2022‑23 relative to current law. However, the supplemental pension payments under the agreement also will provide an unknown long-term benefit to the MVA that will offset these costs by some amount. In addition, the Legislature has received a proposed MOU with Unit 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety) and likely will receive proposed MOUs with the nine bargaining units represented by Services Employees International Union, Local 1000 (Local 1000) in the remaining weeks of session. Virtually all of DMV employees are represented by either Unit 7 or Local 1000. To the extent that these agreements increase DMV personnel costs more than 2 percent each year, the MVA fund condition will be weakened and the Legislature likely will need to take additional actions it took earlier this year to keep the MVA solvent. The administration indicates that it is monitoring the fund and will explore options—if necessary—to keep the fund’s reserve at $100 million.

Supplemental Pension Payments

Administration Provided Estimated Effects of MVA Making Supplemental Pension Payments . . . When the Legislature has considered supplemental payment proposals in the past, we have strongly recommended that the Legislature base its decision on actuarial and stochastic analyses to understand the range of possible effects of making the supplement payment. The payments from the MVA that the administration proposes in the agreement likely would result in long-term savings to the MVA. We asked the administration for an actuarial and stochastic assessment of the benefit to the MVA by making the $100 million supplemental contribution over the term of the agreement. The administration provided one estimate prepared by CalPERS based on actuarial assumptions. A stochastic analysis was not available. Although an actuarial analysis is informative, a stochastic analysis would provide the Legislature a better sense of the range of possible effects because it takes into consideration thousands of possible investment return scenarios whereas the actuarial analysis assumes one investment return scenario. Based on the actuarial analysis, the net savings to the MVA resulting from the supplemental payments would be $128 million over the next few decades. The actual savings could be higher or lower than this estimate and depends on actual investment returns.

. . . And Redirecting General Fund Supplemental Pension Payment. When the Legislature was considering the administration’s budget proposal to make a General Fund supplemental payment to CalPERS, the administration argued that the payment should be apportioned to the pension plans based on the plans’ share of the state’s General Fund contributions to CalPERS. The administration pushed this proposal even after our office pointed out that the proposal would mean that highway patrol would not benefit. The actuarial and stochastic analyses of the SB 90 plan was based on this apportionment. Like the proposed MVA supplemental payment, we asked the administration for actuarial and stochastic analyses of the fiscal effects of redirecting $243 million of the 2020‑21 General Fund supplemental payment established under SB 90. The administration provided us with the effects estimated by an actuarial analysis provided to the administration by CalPERS. Under the apportionment established under SB 90, the administration reported that MVA costs over the next few decades would decrease by $165 million (largely due to employees at DMV). The administration estimates that redirecting $243 million of the 2020‑21 General Fund supplemental pension payment to the highway patrol pension plan would further reduce MVA costs by $560 million over the next few decades. The administration estimates that redirecting the supplemental pension payment to the highway patrol pension plan will—relative to the savings estimated under SB 90—erode the expected General Fund savings over the next few decades by $400 million.