LAO Contacts

- Wildfire Resilience and Response

- Disaster Response and Recovery

- Schools

- Insurance

- Local Government

January 28, 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

About Wildfires in California

Updated February 13, 2025

The catastrophic January 2025 Southern California wildfires have led to increased interest in how the state historically has prepared for, responded to, and recovered from wildfires. In response to this interest, this post answers commonly asked questions related to wildfires in the state of California. This post does not explicitly discuss the recent Southern California fires and does not contain new LAO analysis or recommendations, but rather provides background information intended to help offer broader context on the state’s historical wildfire-related activities, division of roles and responsibilities, and spending. We also discuss some traditional federal-level activities and processes, particularly related to disaster response and recovery. This post is organized into five sections: (1) Wildfire Resilience and Prevention, which involves activities the state performs to decrease the incidence, intensity, and impacts of wildfires before they occur; (2) Wildfire Response, which includes firefighting and protection actions the state undertakes when a wildfire occurs; (3) Wildfire Recovery, which includes typical steps that take place after a wildfire occurs; (4) Funding for Schools and Local Governments, which discusses actions the state has taken to support local entities in response to previous wildfires; and (5) Insurance, where we describe the state-run “backstop” program for insuring against wildfire and other losses.

Table of Contents

- Wildfire Resilience and Prevention

- How does wildfire risk vary across the state? (1/28/25)

- How has the size, destructiveness, and severity of wildfires in California changed over time? (1/28/25)

- What types of factors contribute to wildfire risk? (1/28/25)

- Who owns most of the forestlands in California? (1/28/25)

- What are some recent augmentations the state has provided for wildfire resilience and prevention? (1/28/25)

- How has state spending on wildfire resilience changed over time? (1/28/25)

- What key entities are involved in wildfire resilience and prevention? (1/28/25)

- Wildfire Response

- How does the government typically respond to disasters such as wildfires in California? (1/28/25)

- What key entities are involved in wildfire response? (1/28/25)

- What state funding typically is available to cover immediate wildfire response-related costs? (1/28/25)

- What are some recent augmentations the state has provided for wildfire response? (1/28/25)

- What federal funding typically is available to cover state and local wildfire response-related costs? (1/28/25)

- How has state spending on wildfire response changed over time? (1/28/25)

- How has the state’s firefighting workforce changed over time? (1/28/25)

- Wildfire Recovery

- Funding for Schools and Local Governments

- What has the state done to assist counties, cities, and special districts with property tax losses due to wildfires? (1/31/25)

- How does the state mitigate reductions in property tax revenue for school districts affected by fires and other disasters? (1/28/25)

- How does the state mitigate the effect of reduced student attendance on school district budgets? (1/28/25)

- How does the state mitigate the loss of learning time students experience when a fire or other disaster closes school? (1/28/25)

- How does the state help school districts rebuild school facilities after a fire? (1/28/25)

- Insurance

- What is the FAIR Plan? (1/28/25)

Wildfire Resilience and Prevention

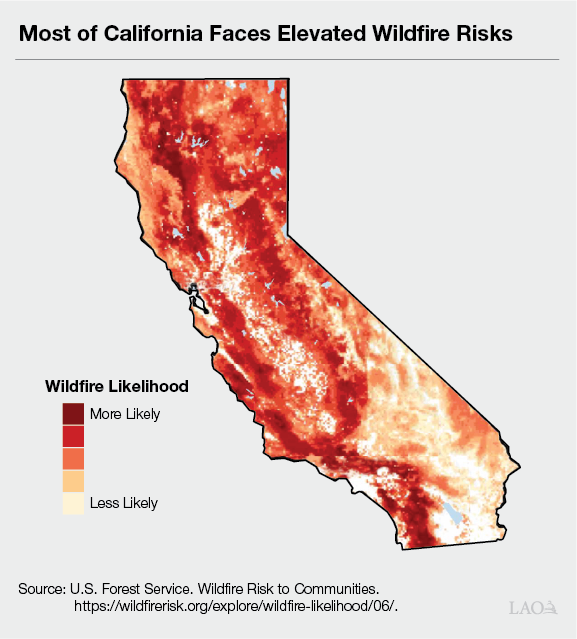

How does wildfire risk vary across the state?

California’s climate makes it naturally susceptible to wildfires. The state’s rainfall is highly seasonal, usually falling mostly in the late fall and winter. Starting in the spring, much of the state typically experiences low levels of rainfall and increasingly warm conditions. These conditions begin to dry out vegetation, which makes the state increasingly susceptible to wildfires during the summer and early fall—or even later in years when dry conditions persist through the winter. Some areas of the state face a particularly high risk of severe wildfires due to factors such as the type of vegetation present, the local weather patterns, and the topography. Many of the areas with the highest risk are where human development abuts or intermingles with undeveloped wildlands (commonly referred to as the wildland-urban interface, or WUI). These spaces often contain smaller communities, but some more populated areas near wildlands also can be highly susceptible to wildfires, such as during high wind conditions.

The Figure displays wildfire likelihood across the state as estimated by the federal government. This reflects the estimated probability of a wildfire burning in any given year (based on fire behavior modeling across thousands of simulations of possible fire seasons). This research estimates that California has, on average, greater wildfire likelihood than any other state in the nation.

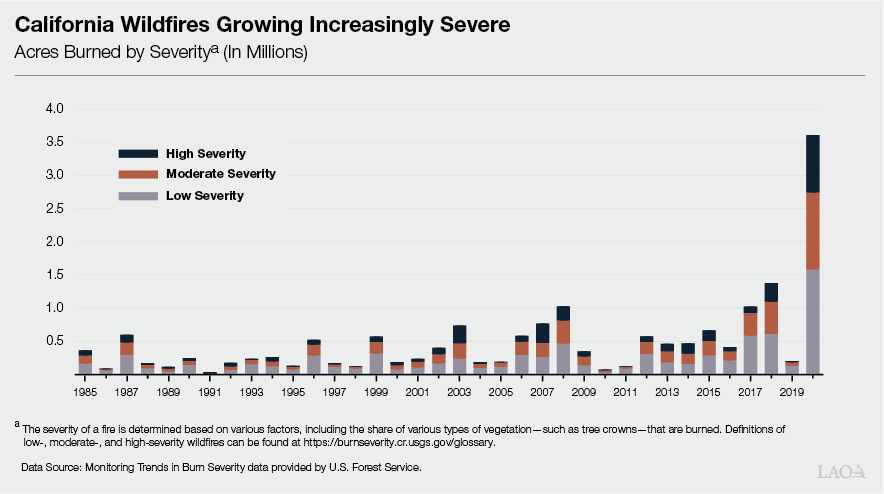

How has the size, destructiveness, and severity of wildfires in California changed over time?

As shown in the Figure, most of California’s largest and most destructive wildfires have occurred in recent decades. (The state compiles these data measured by the number of acres burned and the number of structures destroyed.) This trend has been particularly notable over the last several years, which have seen some of the worst wildfires in the state’s recorded history. For example, eight of the most destructive wildfires occurred from August 2020 through January 2025. This includes the Eaton and Palisades fires, for which specific damage totals still were being refined as of this writing.

While the state has experienced particularly large wildfires within the last several years as compared to over the past century, the number of acres burned in recent decades still is notably less than the historical average. Historically, significant parts of the state would burn annually, especially during the warm, dry months of the year. In the 1700s, for example, an estimated 4.5 million acres burned each year, on average. This is more than four times the average annual amount of acreage that has burned in recent decades, due in large part to the state’s focus on suppressing wildfires. Many plant and tree species native to California adapted to these regular, low- and moderate-intensity wildfires. These fires played an important role in keeping the state’s forests and landscapes healthy by periodically clearing underbrush and contributing to regrowth of native plant species. Because of the change in fire prevalence, when wildfires do occur now, they often burn at higher severity than would naturally be the case. The next Figure shows the increase in acres burned by severity level over the past few decades. High-severity wildfires can be problematic, particularly for forested landscapes, because they often denude landscapes, leaving large areas with mostly charred remnants. (The severity of a fire is determined based on various factors, including the share of various types of vegetation—such as tree crowns—that are burned.) In contrast, lower-severity wildfires typically burn underbrush and smaller trees, but leave intact many larger, well-established trees and species that have adapted to withstand fire.

What types of factors contribute to wildfire risk?

The conditions and causes for each wildfire vary, as do the subsequent impacts. Weather, human activities, and location characteristics can all affect both fire ignitions and resulting damage. As of this writing, information was still being collected regarding which specific contributors led to the January 2025 fires in Southern California. However, some of the significant factors that have contributed to the statewide trends of wildfires becoming deadlier and more destructive in recent decades include:

Increased Development in Fire-Prone Areas. Over time, as the state’s population has increased and more development has occurred, more communities have built up in forested and rural areas that previously had limited development. This intersection of developed areas and the wildlands is known as the “wildland-urban interface,” or WUI. Continued development in the WUI means that more people and property are located in areas prone to wildfires. For instance, between 1990 and 2020, the number of housing units in California’s WUI grew from 3.6 million to 5.1 million (a 42 percent increase). Besides placing more people and structures in locations with higher wildfire risk, increased development and activity in the WUI can also raise the chance of human-caused fire ignitions.

Climate Change. Scientists have found that climate change is contributing to hotter weather and longer dry seasons in California than was previously typical. Warmer weather and more frequent droughts can, in turn, lead to drier vegetation and greater numbers of dead or dying trees, both of which are prone to igniting. Notably, extremely dry conditions in combination with high winds can be particularly high risk for wildfires. This is because high winds can result in embers from a wildfire being blown miles away from the main fire. In such cases, wildfires have jumped across fire breaks, roadways, and bodies of water.

Utility Infrastructure Management. Only about 10 percent of wildfires are started by utility equipment, and many of those fires result in little or no property damage. However, some of these fires can cause significant damage, as has occurred in recent years. Utility powerlines caused at least 8 of the 20 most destructive fires in California’s history. (As of this writing, the role that utility infrastructure played in the January 2025 Southern California wildfires still is under investigation.) Wildfires caused by powerlines can be particularly damaging, in part because some of the factors that cause utility ignitions—such as high winds damaging electrical lines—also contribute to a rapid spread of fire that is difficult to control. For example, Pacific Gas and Electric equipment started the 2018 Camp Fire in Butte County.

Unhealthy Forests. Much of the state’s forestlands are unhealthy, which means they tend to be dense with small trees and brush. These serve as “ladder fuels” to carry wildfires into tree canopies, increasing their spread. Comparatively, a healthy forest typically has less brush and fewer trees, and those trees that are present are larger and more established. Healthy forests tend to have less severe wildfires that burn through the brush and may leave tree canopies intact. Many forestlands are in an unhealthy condition as a result of historical failure to implement logging best practices and years of suppressing naturally occurring wildfires.

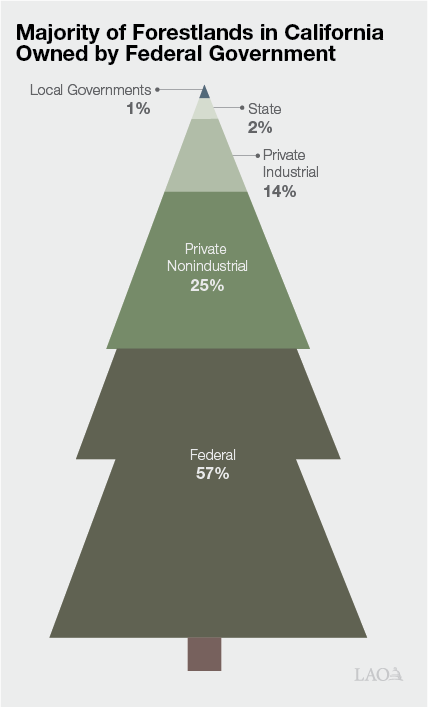

Who owns most of the forestlands in California?

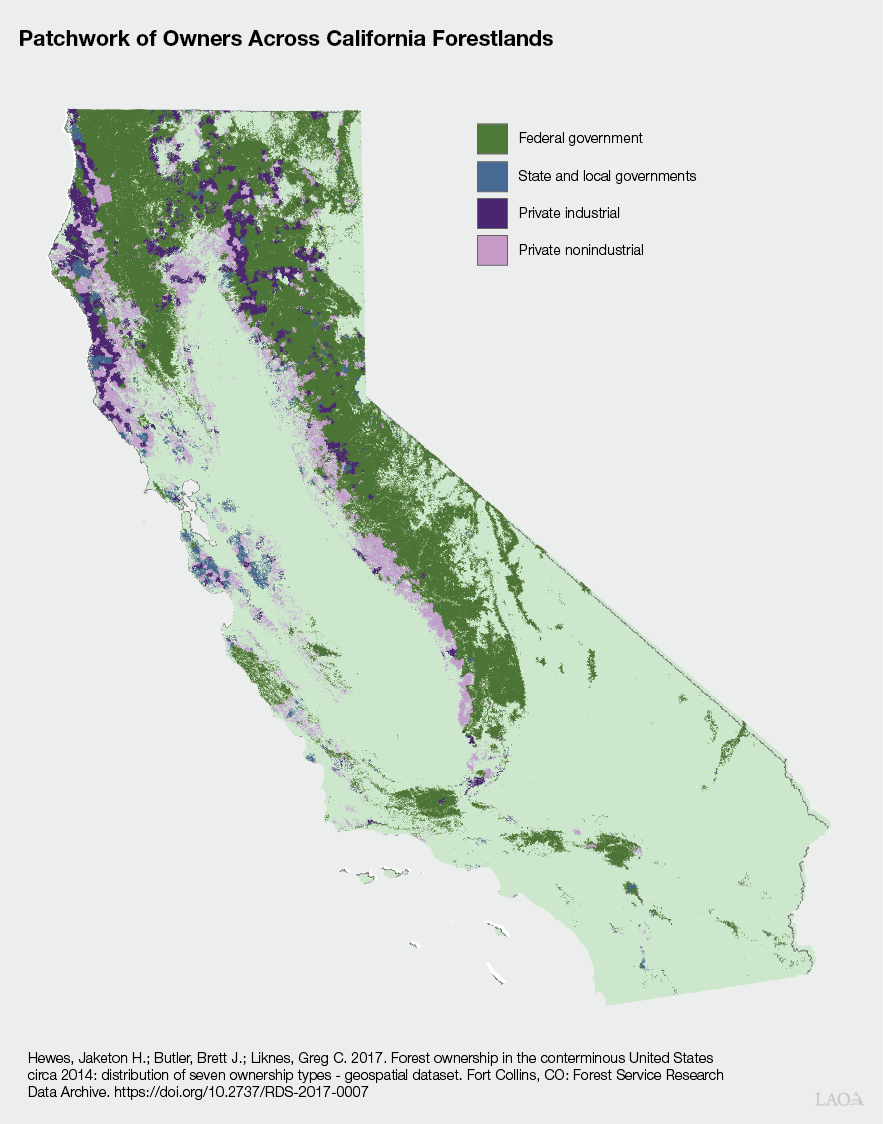

Forestland is defined as land that is at least 10 percent stocked by forest trees of any size, or land that formerly had such tree cover and is not currently developed for a non-forest use. Forestlands can include a variety of types of landscapes. As shown in the Figure, close to 60 percent (nearly 19 million acres) of forestlands in California are owned by the federal government, including by the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and National Park Service. Private nonindustrial entities own about one-quarter (8 million acres) of forestland. These include families, individuals, conservation and natural resource organizations, and Native American tribes. Industrial owners—primarily timber companies—own 14 percent (4.5 million acres) of forestland. State and local governments own a comparatively small share—only 3 percent (1 million acres) combined. This kaleidoscope of ownership has implications for management responsibilities and also makes coordination important when conducting both wildfire resilience and response activities.

The next Figure displays these forest ownership patterns across the state. In some areas, neighboring parcels are owned by a patchwork of different owners. In other areas of the state, a single owner—typically a federal agency—owns a large swath of contiguous land.

What are some recent augmentations the state has provided for wildfire resilience and prevention?

The state has significantly augmented funding for wildfire resilience-related activities across a variety of departments in recent years through two main actions. First, the Legislature passed statutes—Chapter 626 of 2018 (SB 901, Dodd) and Chapter 155 of 2021 (SB 155, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review)—that dedicated $200 million annually from 2019-20 through 2028-29 from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund to support forest health and fire prevention activities. Second, the Legislature approved three major wildfire and forest resilience budget packages in 2021 and 2022, which together pledged a significant amount of one-time funding for wildfire resilience to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) and a variety of other state departments. Together, these commitments total $3.6 billion across over the nine-year period from 2020-21 through 2028-29—$2.6 billion through the wildfire resilience budget packages along with an additional $1 billion outside of those packages. (These totals incorporate a modest reduction of roughly $200 million compared to initial plans for the wildfire resilience budget packages due to a decline in the state’s fiscal condition.) The Figure summarizes these funding commitments. As of the 2024-25 fiscal year, the state has already appropriated $2.7 billion, with an additional cumulative $900 million planned to be provided in forthcoming annual state budgets through 2028-29. (The figure displays major state augmentations for wildfire resilience and prevention over the past several years, but it is not comprehensive of all spending and may omit some smaller items.)

Summary of Recent State Wildfire and Forest Resilience Fundinga

2020‑21 Through 2028‑29 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

Multiyear Totalb |

|

Resilient Forests and Landscapes |

$2,073 |

|

|

TBD forest health and fire prevention activities |

TBD |

$1,000c |

|

Forest Health Program |

CalFire |

552 |

|

Stewardship of state‑owned land |

Various |

246 |

|

Post‑fire reforestation |

CalFire |

100 |

|

Forest Improvement Program |

CalFire |

75 |

|

Forest Legacy Program |

CalFire |

45 |

|

Tribal engagement |

CalFire |

40 |

|

Reforestration nursery |

CalFire |

15 |

|

Wildfire Fuel Breaks |

$761 |

|

|

Fire prevention grants |

CalFire |

$475 |

|

Prescribed fire and hand crews |

CalFire |

129 |

|

CalFire unit fire prevention projects |

CalFire |

90 |

|

Forestry Corps and residential centers |

CCC |

67 |

|

Regional Capacity |

$500 |

|

|

Conservancy projects |

Various Conservancies |

$350 |

|

Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program |

DOC |

150 |

|

Forest Sector Economic Stimulus |

$102 |

|

|

Workforce training grants |

CalFire |

$53 |

|

Climate Catalyst Fund Program |

IBank |

27 |

|

Transportation grants for woody material |

CalFire |

10 |

|

Market development |

OPR |

7 |

|

Biomass to hydrogen/biofuels pilot |

DOC |

5 |

|

Science‑Based Management and Other |

$114 |

|

|

Monitoring and research |

CalFire |

$38 |

|

Remote sensing |

CNRA |

30 |

|

Prescribed fire liability pilot |

CalFire |

20 |

|

Permit efficiencies |

CARB & SWRCB |

12 |

|

State demonstration forests |

CalFire |

10 |

|

Interagency Forest Data Hub |

CalFire |

4 |

|

Community Hardening |

$74 |

|

|

Home hardening |

OES & CalFire |

$38 |

|

Defensible space inspectors |

CalFire |

20 |

|

Land use planning and public education |

CalFire & UC ANR |

16 |

|

Total |

$3,623 |

|

|

aAs of the 2024‑25 Budget Act. bIncludes $2.6 billion approved through discrete wilfire and forest resilience budget packages in 2021 and 2022, as well as $200 million annually from 2024‑25 cSpecific activities and departments TBD in future years. |

||

|

TBD = to be determined; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; CCC = California Conservation Corps; DOC = Department of |

||

One important point to note is that although the state may allocate a specific amount of funding in a given year, the entities receiving grants from the state to undertake wildfire resilience and prevention activities may need multiple years to complete associated projects and fully expend the funds. As such, the notable infusion of one-time funding the state provided over the last several years likely will support projects that take place over several years to come.

In addition to spending its own money, the state requires electric utilities to dedicate funding from their ratepayers to undertake activities intended to reduce the risks of utility-sparked wildfires. Such wildfire mitigation activities include vegetation management (such as trimming and removing trees) and modifying infrastructure (such as covering power lines, installing stronger poles, and burying distribution lines underground). The state also has provided some additional funds to support and oversee these utility wildfire risk reduction efforts.

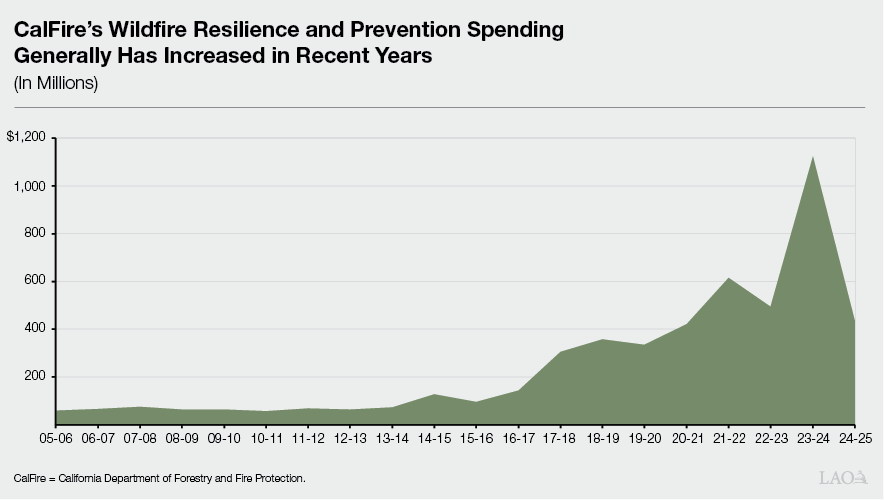

How has state spending on wildfire resilience changed over time?

CalFire’s funding for wildfire resilience-related activities generally has grown over time, aided by significant augmentations in recent years. As shown in the Figure, CalFire’s budget for resource management and fire prevention—which generally is intended to improve the state’s resilience to wildfires by reducing the likelihood that wildfires will occur and lessening associated damage when they do—has increased from about $140 million in 2016-17 to an estimated roughly $440 million in 2024-25. However, as shown in the figure, these funding amounts have varied from year to year due to the one-time nature of many of the augmentations the state has provided. For example, CalFire’s funding for these activities peaked at over $1.1 billion in 2023-24 as a result of significant one-time funding the state provided that year.

CalFire is not the only state department involved in wildfire resilience and prevention activities. Funding for many other departments for such activities—such as various state conservancies—also has generally increased in recent years as a result of the recent wildfire and forest resilience budget packages and other augmentations. However, as of this writing, we do not have comparable data on wildfire resilience spending over time across all of the relevant departments.

What key entities are involved in wildfire resilience and prevention?

The mix of ownership and diverse jurisdictions across the state means that a number of different entities are involved in managing lands and conducting wildfire prevention and resilience activities, as highlighted in the Figure.

Key Entities Involved in Wildfire Resilience and Prevention Activities

|

Entity |

Primary Responsibilities |

|

Federal |

|

|

U.S. Forest Service |

Owns and manages about 15.5 million acres of forestland in California, including 18 National Forests. Oversees activities related to forestry research, resource development, land conservation, and recreation. |

|

Bureau of Land Management |

Owns and manages about 1.6 million acres of forestland in California, including overseeing activities related to resource development, land conservation, and recreation. |

|

National Park Service |

Owns and manages about 1.4 million acres of forestland in California, including preserving natural and cultural resources and facilitating public access. |

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) |

Administers various programs that provide grants to states for actions to reduce the impacts of future disasters, including the Hazard Mitigation Assistance program and the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program. |

|

State |

|

|

Department of Forestry and Fire Protection |

Administers forest health and fire prevention programs. Staffs hand crews that conduct fire suppression, vegetation management, and hazardous fuel reduction projects. Enforces defensible space requirements in the “State Responsibility Area” (SRA, which includes over 31 million acres of mostly privately owned forestlands). Oversees enforcement of state timber harvesting policies on private lands. Manages 71,000 acres of state research forests and conducts forestry research. |

|

Conservation Corps, Military Department, and Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

Staff hand crews that conduct fire suppression, vegetation management, and hazardous fuel reduction projects. |

|

Board of Forestry and Fire Protection |

Serves as regulatory arm of CalFire. Develops state’s forest policies and regulations. |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

Oversees the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Program and helps coordinate statewide forest policies and programs. |

|

State Conservancies |

Allocate funding, generally through grants to other entities, for wildfire resilience projects. |

|

State Parks and Department of Fish and Wildlife |

Conduct wildfire resilience activities on state‑owned lands. |

|

Department of Conservation |

Administers the Regional Forest and Fire Capacity Program to support regional collaboration on forest health and wildfire resilience activities. |

|

Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force |

Develops research, recommendations, and plans for improving the state’s wildfire resilience. |

|

Governor’s Office of Emergency Services |

Administers and allocates federal FEMA funding to communities for disaster mitigation activities. |

|

Office of Energy Infrastructure Safety (OEIS) |

Primary state agency responsible for reducing the likelihood of utility‑involved wildfires. Approves utilities’ wildfire risk mitigation plans. |

|

Public Utilities Commission |

Regulates investor‑owned electric utilities, ratifies the utility wildfire risk mitigation plans approved by OEIS, and oversees the use of public safety power shutoffs. |

|

Other |

|

|

Local government agencies |

Operate planning departments that make land use and zoning decisions related to development in the wildland urban interface. Enforce local and state defensible space requirements as applicable. Operate various programs to reduce wildfire risk, such as by providing financial or in‑kind support for defensible space and/or fuel reduction projects. |

|

Private property owners |

Meet applicable state and local requirements around defensible space and/or timber harvesting. (State defensible space requirements generally apply to residents in the SRA and regions designated as very high fire hazard severity zones.) |

|

Electric utilities |

Manage electrical infrastructure (such as powerlines) and undertake various actions to reduce risks of wildfires started by their equipment. |

|

Local fire safe councils (typically non‑governmental organizations) |

Educate local communities about wildfire. |

Wildfire Response

How does the government typically respond to disasters such as wildfires in California?

The State’s Disaster Response System Takes a “Bottom-Up” Approach. The state’s system of disaster response typically starts at the local level. Members of the public typically alert a local government about a disaster incident—such as a fire—through calls to the 9-1-1 system. Upon receiving such an alert, local first responders—such as police or fire departments—respond to the incident. Many smaller disaster incidents—such as small fires—are handled solely at the local level by these first responders.

Provides Additional Resources Through Mutual Aid System. When disaster incidents are large enough that they overwhelm a local government’s capacity to respond, the local government can request additional resources—such as emergency responders or equipment—from other governmental entities in its mutual aid region through the state’s mutual aid system. Mutual aid refers to the practice of neighboring jurisdictions supporting each other during disasters. If the resources within a mutual aid region are insufficient, regional mutual aid coordinators work with state-level staff to request additional resources from other areas, including local governments in other parts of the state, various state agencies, other states, the federal government, or other countries.

Response to Wildfires Can Vary Depending on Where They Start. In the case of wildfires, the disaster response approach can vary based on where the fire starts and which entity has wildfire response jurisdiction. For example, if a wildfire starts in an area where the state has jurisdiction, the state—rather than a local government—is often the first entity to respond. For more information on the responsibilities of local, state and federal agencies involved in wildfire response, see “What Key Entities are Involved in Fire Response?” on this page.

What key entities are involved in wildfire response?

Wildfire response efforts in California’s wildlands involve firefighting resources at the state, federal, and local levels, as highlighted in the Figure.

Key Entities Involved in Wildfire Response

|

State |

|

|

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire)a |

Main state entity involved in wildfire response. Main entity responsible for protecting State Responsibility Areas, which cover about one‑third of the state’s acreage and mostly include privately owned wildlands. |

|

Governor’s Office of Emergency Services |

Monitors and coordinates wildfire and other disaster response, including tasking other agencies with carrying out specific activities and coordinating mutual aid. Administers various programs that support wildfire response, such as by providing fire engines to local agencies for use in the mutual aid system and pre‑positioning resources in advance of periods of high fire risk known as “red flag warnings.” |

|

California Military Department |

Provides support—such as additional firefighting aircraft—to assist with combatting large fires. Under the supervision of CalFire, operates hand crews that conduct activities such as fire suppression through a program known as “Task Force Rattlesnake.” |

|

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

Under the supervision of CalFire, operates hand crews—staffed by people committed to state prison who are housed at conservation camps—that conduct activities such as fire suppression. |

|

California Conservation Corps |

Under the supervision of CalFire, operates hand crews—staffed by young adult corpsmembers—that conduct activities such as fire suppression. |

|

Local and Federal |

|

|

U.S. Forest Service |

Main federal entity involved in wildfire response. Main federal entity responsible for protecting Federal Responsibility Areas, which generally include lands owned or managed by the federal government. |

|

Various Local Agenciesa |

Entities such as city and county fire departments and local fire protection districts typically are primarily responsible for protecting Local Responsibility Areas, which include incorporated cities and agricultural lands. |

|

aIn some cases, CalFire and local agencies provide primary response and prevention services in each other’s jurisdictions under contractual relationships. |

|

What state funding typically is available to cover immediate wildfire response-related costs?

Some funds for emergency-related activities are included in the annual budgets of state departments tasked with responding to emergencies—primarily CalFire, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, and the California Military Department. In addition, state law provides a few ways for the Governor to access other funds when the Governor declares a state of emergency and/or the state experiences a large wildfire.

Emergency Fund. The Department of Finance (DOF) has authority to allocate more state General Fund to CalFire to pay for the costs of responding to large wildfires (regardless of the existence of a disaster declaration) if the administration finds that the budgeted amount will not be sufficient to cover its costs. (For more detail, please see The 2023-24 Budget: Improving Legislative Oversight of CalFire’s Emergency Fire Protection Budget.)

Disaster Response-Emergency Operations Account (DREOA). Upon the Governor’s declaration of a state of emergency, existing statute authorizes DOF to transfer funds from the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) to DREOA and allocate funds from DREOA to state departments for disaster response operations costs. The SFEU is the state’s discretionary budget reserve of the General Fund.

Authority to Access Any Available State Funds. Upon the Governor’s declaration of a state of emergency, existing state law also gives the Governor the authority to spend any available state funds to respond to the emergency. When redirecting special funds that are otherwise dedicated for a specific purpose, state law requires that the funds be repaid. (For more on this this authority as well as DREOA, please see The 2021-22 Budget: Improving Legislative Oversight of Emergency Spending Authorities)

The Legislature also has broad authority to provide additional funding for disaster and wildfire response. This funding typically comes from the state General Fund. Under the emergency provisions of Proposition 2, the Legislature can withdraw additional funds from the Budget Stabilization Account—the state’s rainy day reserve—to pay for disaster-related costs such as those related to wildfires.

What are some recent augmentations the state has provided for wildfire response?

The Figure highlights many of the key funding increases the state has provided for wildfire response-related activities in recent years. These augmentations have supported a variety of purposes, such as additional firefighters, hand crews, support staff, fire engines, air tankers, helicopters, and various types of new technology. Most of these augmentations have been made through CalFire’s budget, but some other departments also have received additional resources, such as the California Conservation Corps and the California Military Department. As shown in the figure, in many cases, the state has provided funding on an ongoing basis. However, in some instances, the state has provided limited-term resources, such as to purchase new helicopters and other equipment. The majority of these expenditures were supported by the state’s General Fund. In addition to the augmentations shown in the figure, we estimate that the state has dedicated over $800 million from 2017-18 through 2024-25 for CalFire infrastructure projects that support the department’s wildfire-response activities. Examples of such capital outlay projects include replacing and relocating facilities like unit headquarters, fire stations, and air attack bases. The state also has made various smaller wildfire response-related augmentations that are not captured in the figure.

Key Recent State Wildfire Response Augmentationsa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aExcludes non‑wildfire‑specific augmentations and capital outlay projects that support wildfire response. |

|

CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; CCC = California Conservation Corps; OES = Governor’s Office of Emergency Services; CMD = California Military Department; CPUC = California Public Utilities Commission; CAD = Computer Aided Dispatching; and AVL = Automatic Vehicle Locator. |

What federal funding typically is available to cover state and local wildfire response-related costs?

Federal funding for wildfire response can come from a variety of programs and may be distributed to state agencies and local governments. Often the first federal aid that the state receives for wildfire response comes through the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMAs’) Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG) program. The FMAG program reimburses states for eligible costs—such as mobilization, equipment, and supplies—incurred during the first 90 days after grant approval. FEMA typically reimburses 75 percent of eligible costs through the FMAG program. The FEMA Regional Administrator is authorized to grant FMAGs. In making the decision whether to authorize FMAGs, FEMA considers factors such as the threat to lives and property presented by a wildfire as well as the availability of state and local resources. Funding for FMAGs comes primarily from the federal Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), which Congress and the President have historically funded through augmentations provided as needed in response to specific disasters.

Additionally, if the President issues a national emergency or major disaster declaration, state and local agencies may be eligible for reimbursement for a portion of certain wildfire response and recovery costs through FEMA’s Public Assistance (PA) program. In such cases, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services—acting as the fiscal agent for both the state and local governments—coordinates applications for reimbursement through the PA program. Under a national emergency declaration, the PA program typically provides aid for certain types of emergency response-related activities and specific recovery costs (such as debris removal). If the President issues a major disaster declaration, the PA program can also provide funding for roads and bridges, water control facilities, buildings and equipment, utilities, parks and recreation, and certain other costs. FEMA typically reimburses 75 percent of eligible costs through the PA program. However, the President has the authority to adjust the percentage up to 100 percent. Regardless of the authorized federal reimbursement rate, the state and local governments often do not receive every dollar they request as some costs are deemed ineligible. Like the FMAG program, funding for the PA program comes primarily from the federal DRF.

The time it takes for the state and local governments to receive FEMA reimbursements varies. Some payments are made within the budget year, while others take years to recoup because payment only occurs after a project is complete. The timing and level of reimbursement can also be impacted by the amount of funding in the DRF as FEMA can delay payments when its budgeted funds are running low.

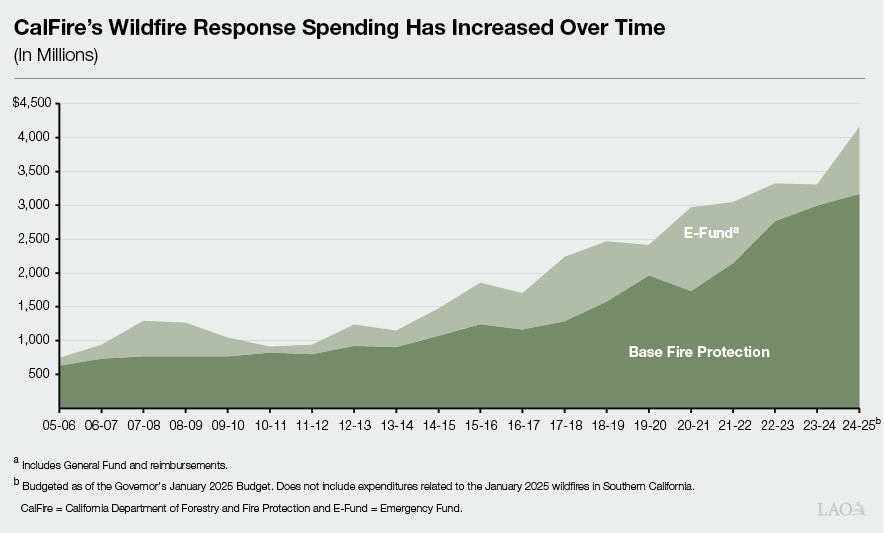

How has state spending on wildfire response changed over time?

The Figure displays how CalFire’s total spending for wildfire response (sometimes referred to as wildfire protection) has grown significantly over the past several years—from $2.2 billion in 2017-18 to $4.2 billion in 2024-25 (an 86 percent increase). (We note that the figure reflects budgeted expenditures for 2024-25 as of the Governor’s January 2025 budget proposal and thus does not include additional costs associated with responding to the January 2025 wildfires in Southern California.)

CalFire’s wildfire response budget has two components. First, CalFire has a base wildfire protection budget, which pays for the department’s everyday firefighting operations, including salaries, facility maintenance, and other predictable and anticipated costs. This amount also is intended to cover costs associated with the “initial attack” on a wildfire—the firefighting operations generally undertaken within the first 24 hours of an incident. Driven by numerous discrete augmentations, CalFire’s expenditures from its base wildfire response budget have grown significantly in recent years. Specifically, as shown in the Figure, these expenditures have grown by $1.9 billion, or nearly 150 percent, from 2017-18 ($1.3 billion) to 2024-25 ($3.2 billion). Notably, some of the recent augmentations still are in the process of being phased in. As such, absent any future actions to reduce funding, these totals will continue to grow. When fully implemented, we estimate that these already-adopted proposals will increase CalFire’s base budget for wildfire response by at least another $600 million annually above the estimated 2024-25 level.

Second, CalFire has an amount budgeted under what is known as the Emergency Fund (E-Fund), which is intended to enable the department to pay for the costs of responding to large wildfires, such as overtime and equipment used after the initial attack. As we discuss in further detail in a 2023 report, the Legislature provides the administration authority to allocate more state General Fund to the E-Fund if at any point during the fiscal year the department finds that the budgeted amount will not be sufficient to cover its costs. As shown in the figure, CalFire’s annual expenditures from the E-Fund have varied depending on factors such as the severity of a given wildfire season. (E-fund expenditures can also include reimbursements from federal and local governments related to firefighting activities CalFire undertakes on their behalf.)

CalFire is not the only state department involved in wildfire response activities. Funding for other departments for such activities—such as the California Military Department and California Conservation Corps—also has generally increased as a result of recent augmentations. However, as of this writing, we do not have comparable data on wildfire response spending over time across all of the relevant departments.

How has the state’s firefighting workforce changed over time?

CalFire’s overall workforce—including those dedicated primarily to wildfire response, as well as those engaged in other activities such as forest resilience—has increased substantially in recent years. Specifically, CalFire’s total staffing grew by more than 80 percent between 2017-18 and 2024-25 (from 6,800 to 12,500). Similarly, the number of positions that CalFire designates as dedicated primarily to wildfire response (also referred to as wildfire protection) has grown by nearly 85 percent over that same period (from 5,800 to 10,800). (Most of these wildfire response-related positions are firefighters, but some represent other types of support personnel.) CalFire relies on a combination of permanent and seasonal firefighters to meet its operational needs. As of 2024-25, we estimate that roughly three-quarters of wildfire response-related positions are permanent and the rest are seasonal. The forthcoming implementation of a shorter workweek for CalFire firefighters (from 72 hours to 66 hours) that the state recently approved will significantly augment these numbers. (We discuss the shift in the workweek in further detail in this 2024 report.) We estimate that by the time the change to the workweek is fully implemented in 2028-29, CalFire positions focused on wildfire response will increase to roughly 12,900.

CalFire is not the only state department involved in wildfire response activities. For example, the California Military Department, California Conservation Corps, and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation all receive funding to support hand crews that help with wildfire response, among other activities. However, as of this writing, we do not have comparable data on wildfire response spending over time across all of the relevant departments.

Wildfire Recovery

What are the main types of disaster recovery assistance?

Disaster recovery assistance is wide-ranging and may be categorized by type of recipient (such as individual, government, or business), type of program (such as grants or loans), purpose of aid (such as debris removal or tax relief), or provider of aid (such as state, local, federal, or nonprofit). The Figure below includes the main types of federal and state disaster recovery assistance that have been offered in recent years. While some of these programs are available for all declared disasters, other types of assistance (such as property tax backfills) are offered at the discretion of policy makers. For more on these programs, please see our 2019 publication, Main Types of Disaster Recovery Assistance.

Main Types of Disaster Recovery Assistance

|

Type of Disaster Assistance |

Federal or |

Type of Program |

||

|

Grant or |

Loan |

Other |

||

|

Assistance Provided to Governments |

||||

|

Public Assistance Program |

F |

✔ |

||

|

California Disaster Assistance Program |

S |

✔ |

||

|

Hazard Mitigation Program |

F |

✔ |

||

|

Assistance Provided to Individuals, Households, or Businesses |

||||

|

Individuals and Households Program |

F |

✔ |

||

|

Rural Development Disaster Assistance Program |

F |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

State Supplemental Grant Program |

S |

✔ |

||

|

Small Business Administration loans |

F |

✔ |

||

|

IBank Disaster Relief and Jump Start Loan |

S |

✔ |

||

|

Income tax relief |

Both |

✔ |

||

|

Property tax relief |

S |

✔ |

||

|

Disaster Unemployment Assistance Program |

F |

✔ |

||

|

National Dislocated Worker Grants (for employment services) |

F |

✔ |

||

|

Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and other food assistance |

F |

✔ |

||

|

Legal, counseling, and other services |

F |

✔ |

||

|

aIn some cases, federal programs are administered by state agencies. |

||||

|

F = Federal; S = State; and IBank = California Infrastructure Economic Development Bank. |

||||

What are the key stages of wildfire recovery?

Wildfire recovery typically occurs in stages, which may overlap with one another. Below, we describe some of the key stages involved in recovery from wildfires.

Addressing Immediate Needs, Returning Access to Properties, and Documenting Damages. The initial stage involves local or other government officials assessing damaged homes and businesses and clearing them for re-entry, if possible. Property owners begin documenting damages and initiating insurance claims. Lead response agencies start identifying what the community needs to recover and begin directing relevant staff and agencies to provide services, funding, or technical assistance. For example, local governments may organize city and county recovery staff, state government may direct agencies to begin clean-up work, and the federal government may authorize specialized aid, such as unemployment insurance for disaster survivors or housing counselors.

Removing Debris. The debris removal process begins with the removal of hazardous waste, such as batteries, paint, and asbestos. The process then moves to general cleanup, which includes the removal of burnt structures, foundations, and contaminated soil, as well as any other measures necessary to prepare a site for rebuilding. Some property owners may choose to remove nonhazardous debris on their own or pay private debris removal professionals. However, many property owners choose to partner with government for debris removal services, typically at no cost to the property owner. This process is a joint effort that can include federal, state, and local agencies. In some fires, state agencies such as the Department of Toxics and Substance Control and California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery are the main agencies tasked with debris removal. In other cases, federal agencies such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers or the Environmental Protection Agency may lead.

Rebuilding Homes, Businesses, and Community Facilities. The central actors in rebuilding homes and businesses are property owners working with private general contractors, architects, and engineers. These specialists work with local government entities (such as permit and planning departments, health and safety inspectors, and related public agencies) to replace damaged structures. Local governments may establish temporary “one-stop” disaster recovery centers to help initiate the recovery and rebuilding process for households and businesses affected by the fires. Property owners also work with the federal, state, and local governments to obtain (often limited) assistance with rebuilding costs not covered by insurance. (Many of these costs are ultimately paid by property owners and their insurers.)

The federal, state, and local governments work together to repair damages to community facilities, government property, and infrastructure. For example, the state Office of Public School Construction may work with local school districts to replace schools and the California Department of Transportation may be brought in to repair or replace state roads.

What key entities are involved in wildfire recovery?

Wildfire Recovery Includes a Variety of Government Entities. Defined broadly, wildfire recovery includes not only cleanup and removal of fire-related debris and contamination, but also activities that support households and business during the process of rebuilding. State, local, and federal entities can provide a wide variety of services and programs to these ends. The figure below highlights some of the key entities that can be involved in wildfire recovery and their primary responsibilities.

Key Federal and State Entities Involved in Recovery Activities

|

Entity |

Primary Responsibilities |

|

Federal |

|

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) |

Acts as the primary federal disaster recovery agency. Provides funding and in‑kind support to state, tribal, territorial, and local governments; as well as to individuals and households. Major programs include the Public Assistance program (for governments) and the Individual Assistance program (for households and businesses). FEMA support levels vary by federal disaster declaration type. |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

Assists in the cleanup of hazardous waste. Provides clean‑up crews and safe disposal of hazardous materials such as paint, cleaners, batteries, oils and pesticides from burned properties. |

|

Housing and Urban Development |

Provides housing‑related support for individuals and households, including mortgage insurance for disaster victims and housing counselors. Also administers the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program, which provides funds to help cities, counties, and states recover from declared disasters. |

|

Small Business Administration |

Offers low‑interest loans to individuals and businesses for homes, personal property (including cars), businesses, and economic injury. |

|

United States Army Corps of Engineers |

Assists with the removal of contaminated debris—such as ash and fire debris—from burned properties. Includes the removal, reduction, and disposal of residential or commercial structures. |

|

United States Department of Agriculture |

Administers various programs to help individuals, communities, farmers, and businesses. Programs focus on livestock assistance and farm loans, farmland and forest repair and restoration, and crop losses. |

|

State |

|

|

Governor’s Office of Emergency Services |

Acts as the primary state disaster response agency. Coordinates recovery efforts and acts as the state’s fiscal agent for federal disaster recovery funds provided to state and local governments. |

|

California Department of Education |

Provides resources to local education agencies for recovery from disasters, including guidance on reopening schools after wildfires, displaced students, provisions for students with disabilities, waivers from average daily attendance rules, and more. Also provides technical support to local education agencies rebuilding schools. |

|

California Department of Food and Agriculture |

Works with various partners to provide care to animals and livestock affected by disaster. |

|

Department of General Services |

Provides technical assistance on contract development and state procurement processes to support recovery efforts, including construction‑related procurements. The Division of the State Architect and the Office of Public School Construction provide technical support and grant funding to local education agencies rebuilding schools. |

|

California Department of Housing and Community Development |

Provides technical assistance to support local governments and housing developers in recovery efforts. Administers housing‑related federal disaster recovery funds. |

|

California Department of Insurance |

Enforces mandatory one‑year moratorium on insurance cancellations in areas near wildfire. Provides consumer assistance for wildfire claimants; including assistance related to insurance fraud and complaints made against agents and firms. |

|

California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery |

Removes ash, debris, and contaminated soil on impacted parcels and properties and identifies and removes fire‑damaged trees in danger of falling on public property or deemed a hazard to crew safety. |

|

California Department of Water Resources |

Assists with fire and watershed mitigation, repairs damage to water infrastructure, and works to prevent flooding that can follow wildfires. |

|

California Health and Human Services Agency |

Takes actions to prevent disruptions in access to health care delivery, prescription medications, medical devices, and behavioral health services for Medi‑Cal members affected by wildfire, among other activities. The Department of Managed Health Care, the regulator of managed care health plans, can direct health plans to help plan members impacted by wildfires access all medically necessary services. The California Department of Public Health works with local public health departments to monitor ongoing public health risks and conducts visits of evacuated licensed skilled nursing facilities to ensure that patients and staff can return safely. The Department of Health Care Access and Information, which oversees health care facility construction standards, provides emergency assessments of hospitals and skilled nursing facilities in emergency areas and can arrange for priority approval for repairs of damaged facilities. |

|

Department of Social Services |

Coordinates with local entities to provide mass shelter. Supports community care facility licensees (such as child care providers and adult and senior residential care providers) impacted by disasters. Provides temporary nutritional benefits through Disaster CalFresh. Provides disaster case management to help impacted individuals navigate and attain services. Provides one‑time grants up to $10,000 to assist individuals and families with rebuilding, replacement of personal property, or rental assistance. |

|

Department of Toxic Substances Control |

Removes household hazardous waste, asbestos, and e‑waste found on impacted parcels and properties. |

|

Employment Development Department |

Distributes federal funding under the Disaster Unemployment Assistance program to individuals whose unemployment was a result of disaster. |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

Monitors water quality and ensures that debris removal activities include measures to contain debris and prevent ash and other materials from entering rivers, creeks, and streams. |

|

Others |

In addition to the above‑listed state departments and agencies, a wide variety of other state entities can be involved with wildfire recovery duties, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles, Department of Fish and Wildlife, Franchise Tax Board, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, Infrastructure Bank, Contractors State License Board, California Department of Transportation, and the California Department of Veterans Affairs. |

Funding for Schools

What has the state done to assist counties, cities, and special districts with property tax losses due to wildfires?

“Ad valorem” property taxes—hereafter referred to as simply property taxes—are a levy on property owners based on the value of their property. Property tax revenues are a major source of funding for local governments in California, including cities, counties, and special districts.

Statute permits counties to reassess the value of property that has been damaged or destroyed from wildfire and other disasters. Damaged or destroyed property (such as residences and commercial buildings) thus can result in tax relief for property owners—but lower revenues for local governments.

In response to recent wildfires, the Legislature has helped local governments offset their loss of property tax collections by providing a General Fund backfill. The Figure shows that recent state budgets have provided a total of over $80 million to local jurisdictions affected by wildfires. The state identifies the backfill amount by requesting data from county staff on estimated property tax losses from reassessments. (Generally, the state has chosen to exclude from a backfill those tax losses from “moveable” [unsecured] property such as recreational vehicles and boats.)

State Has Provided Backfills to Local Governments for

Property Tax Losses Due to Recent Wildfires

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Fiscal Year |

Wildfire (Year) |

Amount |

|

2018‑19 |

Various (2017) |

$33.0 |

|

2019‑20 |

Camp, others (2018) |

31.3 |

|

2020‑21 |

— |

— |

|

2021‑22 |

Various (2020) |

11.0 |

|

2022‑23 |

Various (2021) |

3.8 |

|

2023‑24 |

Kincade (2019) |

0.6 |

|

2024‑25 |

Various (2021) |

1.6 |

|

Total |

$81.3 |

|

|

Note: Does not include funding provided by the state for additional relief to local jurisdications affected by wildfires (such as for general recovery efforts). |

||

How does the state mitigate reductions in property tax revenue for school districts affected by fires and other disasters?

Most school districts in the state are funded through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue. When property tax revenue decreases due to a fire (or other disaster), the state provides an equivalent amount of General Fund revenue to make up the difference. The state provides this backfill automatically through the Local Control Funding Formula (the primary state funding source for schools). One exception pertains to districts with very high levels of per-pupil property tax revenue, sometimes known as “basic aid” districts. These districts do not receive an automatic backfill, though the state previously has provided special appropriations in the budget to offset property tax reductions in these districts.

How does the state mitigate the effect of reduced student attendance on school district budgets?

The California Department of Education administers a waiver process that allows a school district to avoid funding reductions when a fire or other disaster results in school closures or lower attendance rates. The waiver works in two main ways. First, it allows a district to avoid fiscal penalties for having fewer days of instruction than the statutory minimum (normally 180 days). This part of the waiver applies when a disaster results in the complete closure of a school. The second part of the waiver applies when a school remains open but experiences a reduction in attendance rates. (School districts are primarily funded based on their average daily attendance.) The waiver allows a district to receive funding based on its attendance before the disaster occurred.

How does the state mitigate the loss of learning time students experience when a fire or other disaster closes school?

As part of the waiver process mentioned above, districts are currently required to adopt a plan for offering online instruction or independent study to students within ten days of an emergency that results in school closures or significant attendance declines. In addition, districts are required to reopen for in-person instruction as soon as possible, unless prohibited under the direction of the local or state health officer. Beginning July 1, 2025, all districts (not only those using the waiver process) must include in their comprehensive school safety plans how, following an emergency event, they will (1) communicate with students and families within five calendar days; (2) identify and provide supports for pupils’ social-emotional, mental health, and academic needs; and (3) provide access to in-person or remote instruction within ten instructional days. To meet this latter requirement, districts may also help students enroll or be temporarily assigned to another district within the same county or an adjacent county.

How does the state help school districts rebuild school facilities after a fire?

State law generally requires districts to carry fire insurance for the properties they own. When a school facility is destroyed by fire, payouts on these policies provide funding to help districts rebuild. The state supports school districts with facilities through various grants within the School Facility Program, which is administered by the State Allocation Board. School districts affected by a fire may be eligible for facility hardship grants. Facility hardship applications are prioritized over normal construction and modernization projects. To be eligible, a school district must demonstrate that a facility needs to be replaced due to an imminent health and safety threat, or existing facilities have been lost due to fire, flood, earthquake or another disaster circumstance. The State Allocation Board may also support districts impacted by a natural disaster in procuring interim housing, such as portable classrooms. Through the main School Facility Program, school districts may also apply for state funding to partially cover the costs of new construction and modernization. Districts that are unable to provide their share of matching funds can apply for financial hardship funding and have the state cover up to 100 percent of project costs.

Insurance

What is the FAIR Plan?

Insurer of Last Resort. The Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan is the state’s insurer of last resort. The state created the FAIR Plan in 1968 to be a temporary safety net that provides homeowners with basic insurance coverage when none is available in the competitive market. For much of its history, it filled this role, covering a very small number of California homes.

Rapid Growth in Recent Years. Since 2018, however, the number of properties covered by the FAIR Plan has more than tripled. The FAIR Plan now covers around 450,000 properties statewide, with a total potential for loss of $450 billion. While the FAIR Plan only covers about 5 percent of homeowners statewide, reliance is much higher in communities with high wildfire risk.

Backstopped by Private Insurers. Like any insurer, the FAIR Plan pays claims out of premiums it collects from property owners in combination with reinsurance—insurance for insurers which provides additional funding in years of unusually large losses. If these resources are inadequate, the FAIR Plan is authorized to place a charge on insurance companies to collect additional funds to pay claims. A share of these charges is passed on to consumers. The consumers’ share is larger when the charge is larger. The FAIR Plan last collected such charges in 1995.