Jennifer Pacella

February 6, 2025

The 2025‑26 Budget

Higher Education Overview

Summary

Higher Education Plan Reflects a Tale of Two Budgets. In 2025‑26, the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget is projected to be more constrained than the Proposition 98 side. Correspondingly, the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC)—supported by the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget—receive ongoing base reductions totaling nearly $800 million. In contrast, the California Community Colleges (CCC)—supported by the Proposition 98 side of the budget—receive $357 million in ongoing augmentations and $395 million in new one‑time funds. Though the budget plan reduces state support for the universities, CSU and UC are planning to raise their tuition charges—a significant source of nonstate funding. Accounting for all core funding, CCC funding increases by 1.9 percent, CSU funding increases by 0.7 percent, and UC funding falls by 0.3 percent in 2025‑26.

Several Important Factors to Consider in Understanding Impact on Universities. The reductions that the budget plan includes for CSU and UC were made pursuant to Control Section 4.05 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act, which applied reductions of up to 7.95 percent to the “state operations” component of most state agencies’ budgets. Though treated the same as most other state agencies, CSU and UC are different in notable ways: (1) all of their state funding is designated as state operations (with none designated as “local assistance”), (2) they can access additional tuition revenue, and (3) the state does not authorize their employee positions (or ratify their collective bargaining agreements). Though comparisons to other state agencies can be complicated for these reasons, CSU and UC have identified the kinds of things they would do in response to the fiscal constraints they are facing. The universities are considering leaving vacant positions open, postponing some facility projects, reducing travel and other lower‑priority expenses, and using reserves, among other actions. In turn, students could end up with larger classes, fewer course offerings, and impacted student support services. Given total core funding for CSU and UC is not changing much in 2025‑26, these responses would be driven mostly by certain projected cost increases, including benefit costs, that the universities have identified for the coming year.

Recommend Signaling More Realistic Budget Expectations. Though the budget plan contains base reductions for CSU and UC in 2025‑26, it includes large General Fund increases for them in 2026‑27. Given updated data on the projected deficit, the state likely will not have budget capacity to support substantial increases in General Fund support for any programs, including for CSU and UC, in 2026‑27. We think signaling this expectation is more realistic for the universities and avoids having the state create new fiscal obligations it cannot currently afford.

Recommend Aligning State Funding With Enrollment Expectations. All three segments have exceeded their systemwide enrollment targets in 2024‑25, and the universities are on track to meet their 2025‑26 targets. Both CSU and UC, however, have expressed concern about continuing to grow enrollment in the absence of additional state funding, as doing so can negatively affect their programmatic quality. Consistent with historic practice, we recommend the Legislature keep funding connected with students. If General Fund resources are available, more enrollment could be supported, otherwise enrollment targets could be held flat. Given Proposition 98 funding is growing, the Legislature could consider funding more CCC enrollment growth than the Governor’s budget does.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on Higher Education Budget. In this brief, we first provide an overview of the Governor’s proposed 2025‑26 budget plan for higher education. We then assess that plan. We conclude by offering a few budget recommendations. In the brief, we focus on the major budget components for CCC, CSU, UC, and the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). Over the coming weeks, our office plans to release additional budget briefs that delve more deeply into the Governor’s proposals for each of these segments. Beyond these budget briefs, our EdBudget website contains many budget tables showing the Governor’s education proposals.

Overview

In this section, we summarize the funding and spending levels proposed for higher education under the Governor’s budget.

Funding

Governor’s Budget Reflects Reduced General Fund Support for Higher Education. As Figure 1 shows, the Governor’s budget for 2025‑26 includes a total of $22.4 billion in ongoing General Fund support for the three segments and CSAC. The proposed 2025‑26 funding level is $360 million (1.6 percent) lower than the revised 2024‑25 level. General Fund support declines for UC and CSU, while increasing slightly for CCC and remaining about flat for CSAC. The higher education reductions in the Governor’s budget are consistent with a multiyear budget agreement reached last year. (As we cover in The 2025‑26 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state agreed last year to $12 billion in total 2025‑26 spending reductions.)

Figure 1

Total General Fund Support for Higher Education

Declines Somewhat in 2025‑26

Ongoing General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change From 2024‑25 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCC |

$7,955 |

$9,689 |

$9,722 |

$33 |

0.3% |

|

CSU |

5,391 |

5,526 |

5,403 |

‑122 |

‑2.2 |

|

UC |

4,717 |

4,858 |

4,587 |

‑272 |

‑5.6 |

|

CSAC |

2,468 |

2,729 |

2,730 |

1 |

— |

|

Totals |

$20,532 |

$22,802 |

$22,442 |

‑$360 |

‑1.6% |

|

Note: Amounts reflect Governor’s new proposals, as well as reductions applied pursuant to |

|||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

|||||

Local Property Tax Revenue for Community Colleges Continues to Trend Upward. Beyond state General Fund support, the three segments receive substantial core funding from other sources. For CCC, the largest nonstate fund source is local property tax revenue. CCC local property tax revenue that counts toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is projected to increase $233 million (5.4 percent) in 2025‑26. This local property tax growth rate is higher than its historical growth rate over the past 20 years (4.7 percent).

Student Tuition Revenue at UC and CSU Increases. For CSU and UC, the largest nonstate core fund source is student tuition revenue. CSU and UC now have tuition policies in place that generally raise tuition charges moderately each year (discussed in more detail below). UC began raising its tuition charges in 2022‑23, with CSU following in 2024‑25. Prior to having these policies, CSU and UC had held their resident undergraduate and graduate tuition charges flat for an extended period, with these charges raised once only since 2011‑12. (In 2017‑18, CSU and UC raised resident tuition charges by 5 percent and 2.7 percent, respectively. In a few other years, UC also assessed small increases to its Student Services Fee.) Beyond tuition increases, tuition revenue also grows as enrollment increases. Total tuition revenue (accounting for increases in tuition charges and enrollment) is estimated to rise $188 million (5.4 percent) at CSU and $241 million (4.4 percent) at UC in 2025‑26. Both CSU and UC have policies that set aside a portion of new tuition revenue for student financial aid. Of the new tuition revenue the segments expect to generate in 2025‑26, CSU is planning to set aside $63 million (one‑third) and UC is planning to set aside $98 million (about 40 percent) for student financial aid.

Governor Assumes CSU Continues to Implement Its Tuition Policy. Under CSU’s tuition policy, the tuition charge is set to increase 6 percent annually for all students (both undergraduate and graduate students), beginning in 2024‑25 and extending through 2028‑29. In 2025‑26, the annual tuition charge for a full‑time student is set at $6,450 for resident undergraduates, reflecting an increase of $366 over the 2024‑25 rate. CSU estimates increases in its tuition charges will generate $164 million in additional tuition revenue in 2025‑26. CSU’s tuition level has long been lower than comparable public institutions nationally. In 2023‑24, CSU’s resident undergraduate tuition and fees were approximately $2,171 (22 percent) lower than the national average of comparable public institutions.

Governor Also Assumes UC Continues to Implement Its Tuition Policy. UC’s tuition policy generally pegs increases in annual tuition charges to inflation. Incoming undergraduate students and all academic graduate students are subject to the tuition increases, with tuition charges for continuing undergraduate students held flat (for up to six academic years). In 2025‑26, systemwide tuition and fees is set at $14,934 for new resident undergraduate students, reflecting an increase of $498 (3.4 percent) from 2024‑25. UC also is raising nonresident supplemental tuition in 2025‑26. The supplemental rate for nonresident undergraduates (which is in addition to the base rate for resident students) is set at $37,602. The supplemental rate rises by $3,402 (10 percent) from 2024‑25. The planned increase for nonresident students is higher than the inflation‑based rate generally aimed for under UC’s tuition policy. UC estimates increases in its tuition charges will generate $225 million in additional tuition revenue in 2025‑26. UC’s tuition level has long been higher than comparable public institutions nationally. In 2023‑24, UC’s resident undergraduate tuition and fees were approximately $2,300 (18 percent) higher than the national average of public institutions classified as having very high research activity.

Governor Proposes No Tuition Increase at CCC. The Governor proposes no increase in the community college enrollment fee—retaining the existing per unit enrollment fee of $46. The annual enrollment fee for a student enrolled full time (30 units) would remain at $1,380. The CCC enrollment fee was last raised in summer 2012, at which time the state increased the per‑unit fee from $36 to $46. Community college fees in California remain the lowest of any state and significantly below the national average. In 2023‑24, community college tuition and fees averaged approximately $5,300 nationally—about four times the CCC tuition level.

Nonstate Funds Help Mitigate State Reductions. Figure 2 shows the changes in core funding by source for each segment. Core funding at CCC increases nearly 2 percent. At CSU, increases in student tuition revenue more than offset reductions in state funding, whereas increases in student tuition revenue fall slightly short of offsetting reductions in state funding at UC.

Figure 2

Increases in Other Core Funds Help Mitigate General Fund Reductions

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change From 2024‑25 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCC |

|||||

|

General Funda |

$7,410 |

$9,048 |

$9,041 |

‑$6 |

‑0.1% |

|

Local property taxa |

4,070 |

4,304 |

4,538 |

233 |

5.4 |

|

Additional General Fundb |

545 |

641 |

681 |

39 |

6.1 |

|

Additional local property taxb |

454 |

481 |

509 |

27 |

5.7 |

|

Student fees |

482 |

482 |

484 |

2 |

0.3 |

|

Lottery |

364 |

316 |

316 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($13,324) |

($15,273) |

($15,569) |

($295) |

(1.9%) |

|

Proposition 98 Reserve |

$788 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$14,111 |

$15,273 |

$15,569 |

$295 |

1.9% |

|

CSU |

|||||

|

General Fundd |

$5,391 |

$5,526 |

$5,403 |

‑$122 |

‑2.2% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

3,267 |

3,477 |

3,665 |

188 |

5.4 |

|

Lottery |

83 |

76 |

76 |

—c |

0.3 |

|

Totals |

$8,741 |

$9,078 |

$9,144 |

$66 |

0.7% |

|

UC |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,717 |

$4,858 |

$4,587 |

‑$272 |

‑5.6% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

5,268 |

5,498 |

5,740 |

241 |

4.4 |

|

Lottery |

65 |

59 |

59 |

— |

— |

|

Othere |

409 |

401 |

401 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$10,460 |

$10,817 |

$10,787 |

‑$30 |

‑0.3% |

|

aFunds that count toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Excludes Proposition 98 Reserve funds. b“Additional General Fund” refers to non‑Proposition 98 funds for CCC state operations, certain pension costs, and debt service. “Additional local property tax” cLess than $500,000. dIncludes funding for pensions and retiree health benefits. eIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. |

|||||

Administration Expects All Segments to Increase Resident Undergraduate Enrollment. Figure 3 shows how core funding is changing on a per‑student basis. As the top part of Figure 3 shows, the administration expects each of the three segments to increase their enrollment in 2025‑26. The administration proposes 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth at community colleges. For CSU and UC, the administration maintains the expectations set forth in the 2024‑25 Budget Act. The 2024‑25 Budget Act specified that CSU was to grow resident undergraduates by approximately 6,300 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students in 2024‑25 and about 10,200 FTE students in 2025‑26. The 2024‑25 Budget Act specified that UC was to grow resident undergraduates by approximately 3,000 FTE students each year from 2024‑25 through 2026‑27. As of January 2025, both segments report exceeding their growth targets in 2024‑25, leaving less growth needed to meet their 2025‑26 targets. (The annual targets for UC include the expected replacement of 902 FTE nonresident students with resident undergraduates across three high‑demand campuses. UC reports exceeding this expectation too in 2024‑25.)

Figure 3

Core Funds Per Student Increase at CCC,

While Falling at CSU and UC

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change From 2024‑25 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Enrollmenta |

|||||

|

CCC |

1,031,323 |

1,036,480 |

1,041,662 |

5,182 |

0.5% |

|

CSU |

391,268 |

401,300 |

407,936 |

6,636 |

1.7 |

|

UC |

293,483 |

299,486 |

300,111 |

625 |

0.2 |

|

Totals |

1,716,074 |

1,737,266 |

1,749,709 |

12,443 |

0.7% |

|

Per‑Student Fundingb |

|||||

|

CCC |

$11,895 |

$12,882 |

$13,036 |

$154 |

1.2% |

|

CSU |

22,339 |

22,622 |

22,416 |

‑206 |

‑0.9 |

|

UC |

35,638 |

36,119 |

35,942 |

‑177 |

‑0.5 |

|

aReflects full‑time equivalent (FTE) students. For CCC, reflects estimated actual enrollment bReflects ongoing core funds per FTE student. The CCC amounts reflect Proposition 98 |

|||||

Core Funds Per Student Up at CCC, Down at Universities. As the bottom part of Figure 3 shows, core funding per student would range from just over $13,000 at CCC to nearly $36,000 at UC in 2025‑26. Core funding per student would rise in 2025‑26 for CCC, while falling at CSU and UC. None of the changes, however, are large in percentage terms. Per‑student funding at CCC increases by 1.2 percent, whereas per‑student funding at CSU and UC declines by less than 1 percent.

Plan Contains Deposits Into Proposition 98 Reserve. The budget plan the state adopted last year drew down all existing funding in the Proposition 98 Reserve ($8.4 billion) to cover certain 2023‑24 Proposition 98 costs. Of this amount, $788 million was designated for CCC costs ($546 million for 2023‑24 apportionment costs and $242 million for various CCC costs shifted from 2022‑23 to 2023‑24). Under the Governor’s 2025‑26 budget plan, the state would make deposits into the Proposition 98 Reserve in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, ending 2025‑26 with a Proposition 98 Reserve of $1.5 billion. The state would decide how much of these reserves to designate for community college purposes when it makes future reserve withdrawals.

Spending

Governor’s Budget Reflects Reduced General Fund Support for Universities in 2025‑26. Consistent with the budget plan set forth in June 2024, ongoing base General Fund reductions are applied to CSU ($375 million) and UC ($397 million) in 2025‑26. CSU and UC would have flexibility in determining how to accommodate these reductions. Compared to the June 2024 estimates, the CSU amount is $21.4 million smaller (down from $396.6 million) whereas the UC amount is $20 million larger (up from $377 million). These changes are due to certain methodological modifications the administration made to its calculations. Also consistent with the June 2024 budget plan, one‑time base reductions made to CSU ($75 million) and UC ($125 million) in 2024‑25 are restored in 2025‑26. Characterized differently, each segment was subject to a base reduction in 2024‑25 that gets larger in 2025‑26, with CSU’s reduction $300 million larger and UC’s reduction $272 million larger year over year. These reductions are pursuant to Control Section 4.05 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act. This budget control section, which applied broadly across state government, authorizes reductions of up to 7.95 percent in state operations.

Budget Plan Contains Deferred Augmentations for Universities. Also consistent with the June 2024 budget plan, ongoing General Fund augmentations of about 5 percent for CSU and UC are deferred from 2025‑26 until 2027‑28. Specifically, the plan defers augmentations of $252 million for CSU and $241 million for UC. (As part of the Governor’s five‑year compacts, the Governor indicated intent to provide CSU and UC with 5 percent annual base increases from 2022‑23 through 2026‑27 as a way to offer them more predictable funding levels.) At UC, the budget also defers $31 million in additional funding for the nonresident replacement plan. For the past three years, the state has been providing UC with funding to replace nonresident students at three high‑demand campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) with resident undergraduate students. The fourth year of this funding, as with UC’s base increase, is deferred two years (from 2025‑26 until 2027‑28). Under the deferral arrangement, one‑time back payments would be provided to CSU and UC in 2026‑27 (for 2025‑26 costs) and 2027‑28 (for 2026‑27 costs).

Governor Retains Compact Expectations. In exchange for receiving more predictable funding levels, the Governor wanted CSU and UC to meet certain expectations. The compacts, for example, include expectations that CSU and UC increase resident enrollment (including in high‑demand areas), close equity gaps, and improve workforce preparation. Although the budget plan does not include a base General Fund increase for CSU and UC in 2025‑26, the administration continues to expect the segments to meet compact goals. (The compacts remain uncodified, and no statutory repercussions are set forth if the segments do not meet one or more compact goals.)

Budget Plan Reflects Reduction in Middle Class Scholarship (MCS) Funding. Consistent with last year’s budget agreement, the MCS program receives $527 million ongoing General Fund in 2025‑26, down from a revised 2024‑25 level of $925 million. The funding level in 2025‑26 reflects the expiration of $289 million in one‑time General Fund, along with a $109 million reduction in ongoing General Fund. CSAC estimates MCS awards accordingly would change from covering about 30 percent of students’ remaining financial need in 2024‑25 to 18 percent in 2025‑26.

Most New Higher Education Spending Is for Community Colleges. Figure 4 shows the Governor’s proposed higher education augmentations, excluding certain caseload‑related and technical changes. As the figure shows, the Governor proposes $828 million in new higher education spending ($358 million ongoing, $470 million one time). The bulk of proposed new spending is for community colleges. The Governor’s budget covers a 2.43 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for CCC apportionments and several CCC categorical programs. The Governor’s budget funds 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth at CCC, supporting about 5,400 additional students. The Governor’s budget also provides new funding for various other CCC purposes, including initiatives related to information technology and career education.

Figure 4

Budget Plan Includes Higher Education Augmentations

General Fund Changes, 2025‑26a (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Increases |

|

|

CCC apportionments (2.43 percent COLA) |

$230 |

|

CCC enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

30 |

|

CCC categorical programs (2.43 percent COLA) |

30 |

|

CCC Rising Scholars Network |

30 |

|

CCC Systemwide Common Technology Platform, Phase 1 |

29 |

|

CCC credit for prior learning |

7 |

|

CSU Capital Fellows programs |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($358) |

|

One‑Time Increases |

|

|

CCC Systemwide Common Technology Platform, Phase 2 |

$168 |

|

CCC Systemwide Common Technology Platform, Phase 1 |

134 |

|

CCC career passports |

50 |

|

CCC credit for prior learning |

43 |

|

Golden State Teacher Grants |

50 |

|

California College of the Arts |

20 |

|

College Corps augmentationb |

5 |

|

Subtotal |

($470) |

|

Total Changes |

$828 |

|

aBesides 2025‑26, some CCC spending is attributed to 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. bIn 2025‑26, total General Fund for the program would be $68 million, rising to $84 million in 2026‑27. |

|

|

Note: The table excludes $60 million Proposition 98 Strong Workforce Program funds for a CCC |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

Governor’s Budget Includes a Smattering of Other Discretionary Proposals. Outside of the community colleges, the Governor’s budget includes four new discretionary spending proposals. The budget includes $50 million one‑time General Fund to extend the Golden State Teacher Grant program (which CSAC administers) by one year. Created as a temporary initiative in 2021‑22, this program provides grants to students in teacher education programs who agree upon graduation to work in certain subject areas or types of schools for a minimum‑required amount of time. The budget includes $20 million one‑time General Fund to provide general fiscal support for the California College of the Arts (a private, nonprofit school). The budget includes a $5 million ongoing General Fund augmentation for College Corps, raising total General Fund for that program to $68 million (with intent to raise further to $84 million in 2026‑27). California Volunteers (within the Governor’s Office of Service and Community Engagement) administers this program. Established in 2021‑22, College Corps provides paid service opportunities to undergraduates at CCC, CSU, UC, and private universities. Lastly, the Governor’s budget includes a $1.3 million ongoing General Fund augmentation for the Capital Fellows programs, which CSU’s Center for California Studies administers. The Governor proposes to increase the monthly salary for Capital Fellows from $3,253 to $4,888, reflecting a $1,635 (50 percent) increase in 2025‑26.

Governor’s Budget Covers Certain Cost Increases, Mostly in the Financial Aid Area. Beyond these new spending proposals, the Governor’s budget funds certain caseload and other cost increases. Notably, the Governor’s budget covers projected cost increases for the Cal Grant program—providing $14 million in additional funding in 2024‑25 and a further $109 million in 2025‑26 (reflecting a 4.5 percent increase over the revised 2024‑25 level). The projected Cal Grant cost increases include $48 million to cover the higher tuition costs at UC and CSU in 2025‑26, as Cal Grants generally cover tuition costs for students with financial need. The administration typically revises the Cal Grant cost estimates again in the May Revision, upon receiving updated caseload data in the spring. The Governor’s budget also contains ongoing General Fund adjustments to CSU’s base budget in 2025‑26 to reflect projected cost increases for pensions ($136 million) and retiree health ($41 million).

Assessment

In this section, we assess the higher education budget plan and discuss the potential effects on the segments.

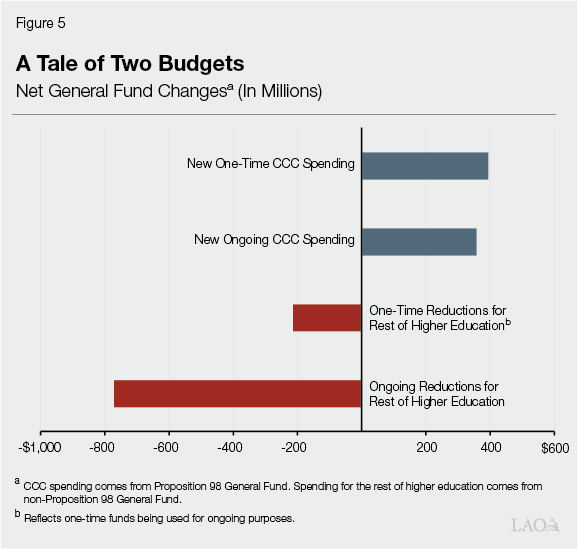

Budget Plan

Budget Plan Reflects Stark Differences in Funding Among the Segments. The higher education budget consists of two contrasting stories. As Figure 5 shows, Proposition 98 General Fund spending for the community colleges increases. Associated ongoing and one‑time spending each increase by nearly $400 million. In contrast, spending for the rest of higher education (UC, CSU, and CSAC) shrinks. Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund support declines by a net of almost $800 million in ongoing funding and about $200 million in one‑time funding that had been used for ongoing purposes. These funding differences stem from certain budgetary constraints. Most notably, Proposition 98 guarantees a minimum level of funding for community colleges (and school districts). That guarantee does not apply to the rest of higher education, which is impacted more directly by the state General Fund condition. The combined effect is that the funding levels among the higher education segments do not necessarily reflect all of the factors the Legislature may want to consider when budgeting. Ideally, the Legislature may want to account for factors such as the number of high school graduates, the labor market, college‑going rates, the quality of the segments’ academic programs, and employee trends.

Budget Plan Does Not Account for Key Differences Between Universities and Other State Agencies. Though CSU and UC were included in the Control Section 4.05 reductions, they differ in some notable ways from other state agencies. One difference is that the state designates all CSU and UC appropriations as “state operations,” with none designated as “local assistance.” This means all university spending at both the system and campus levels are designated as state operations. Applying a flat percentage reduction to state operations funding for the universities therefore results in a much more sizeable cut—one that is likely to have a direct impact on campuses. In contrast, the state is not applying Control Section 4.05 reductions to other agencies’ local assistance programs. From this perspective, the universities are more adversely impacted by Control Section 4.05. Another notable difference, however, is both CSU and UC generate substantial nonstate revenue through student tuition. After accounting for anticipated growth in tuition revenue, CSU’s and UC’s total core funding is not changing much, even with the cuts to their state funding. Many other state agencies lack the ability to generate much, if any, nonstate revenue. A third notable difference is that the state does not directly authorize each employee position at CSU and UC, as is typically the case with state agencies. Instead, the CSU Board of Trustees and UC Board of Regents have that authority. This is why CSU and UC were excluded from the vacant positions sweep imposed by Control Section 4.12 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act. Other state agencies had to accommodate the effects of both Control Sections 4.05 and 4.12. (Though unrelated to the impacts of these control sections, a fourth notable difference is that the Legislature does not ratify CSU and UC collective bargaining agreements.)

University Deferrals Are Poor Fiscal Practice. The deferral plans contain large increases in General Fund support for CSU and UC in 2026‑27, as Figure 6 shows. Given updated projected deficits from our office and the administration, the most likely scenario is that the state would not have budget capacity to provide General Fund base increases to CSU and UC in 2026‑27 (absent a significant positive change in the state’s fiscal outlook). Given CSU and UC would have little certainty of receiving payment in 2026‑27, they likely would be reticent to support new ongoing spending in 2025‑26. Such an approach therefore leaves the Legislature lacking clarity regarding how much CSU and UC would spend in 2025‑26, and, in turn, exactly which spending priorities they would cover.

Figure 6

Deferral Plans Contain Steep General Fund Increases for CSU and UC in 2026‑27

Reflects Multiyear Assumptions of Deferral Plans, General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

|

|

CSU |

|||

|

Ongoing Changes |

|||

|

Base reduction |

‑$375 |

— |

— |

|

Two‑year deferral of year 4 base increaseb |

— |

— |

$252 |

|

Anticipated year 5 base increase |

— |

$265 |

— |

|

One‑Time Back Payments |

|||

|

Base costs |

— |

$252 |

$252 |

|

One‑Time Adjustmentsc |

$75 |

— |

‑$252 |

|

Totals |

$5,403 |

$5,921 |

$6,173 |

|

Change from previous year |

‑2.2% |

9.6% |

4.3% |

|

UC |

|||

|

Ongoing Changes |

|||

|

Base reduction |

‑$397 |

— |

— |

|

Deferral of year 4 base increaseb |

— |

— |

$241 |

|

Deferral of year 4 nonresident replacement fundingb |

— |

— |

31 |

|

Anticipated year 5 base increase |

— |

$254 |

— |

|

Anticipated year 5 nonresident replacement funding |

— |

30 |

— |

|

One‑Time Back Payments |

|||

|

Base costs |

— |

$241 |

$241 |

|

Nonresident relacement costs |

— |

31 |

31 |

|

One‑Time Adjustmentsc |

$125 |

— |

‑$272 |

|

Totals |

$4,587 |

$5,142 |

$5,413 |

|

Change from previous year |

‑5.6% |

12.1% |

5.3% |

|

aIn 2025‑26, the Governor will be entering year 4 of his compact with the CSU Chancellor and UC President. The fifth and final year of this compact is bUnder the deferral plans, the year 4 base increases and UC nonresident replacement funding are deferred from 2025‑26 to 2027‑28. In 2026‑27, one‑time cIn 2025‑26, reflects the restoration of one‑time reductions applied in 2024‑25. In 2027‑28, reflects removal of prior‑year, one‑time back payments. |

|||

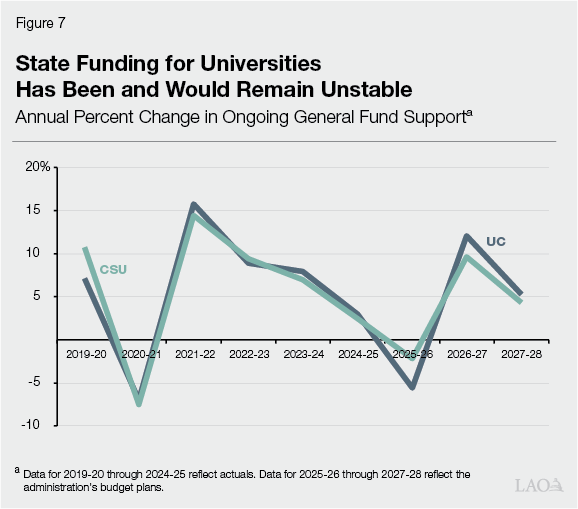

Universities Are Not Experiencing More Predictable State Funding Levels. Despite the Governor’s compacts and desire to provide CSU and UC with predictable annual funding increases, ongoing General Fund support for the universities has not followed such a trajectory. As Figure 7 shows, state funding for universities over the last several years has been volatile. From 2019‑20 through 2024‑25, ongoing General Fund support for UC and CSU has seen annual increases as high as 16 percent and annual declines as deep as 8 percent. Looking at the budget plan for the universities over the next three years, state support would remain volatile, with annual ongoing General Fund increases as high as 12 percent (if state funding permitted) and annual declines as deep as 5.6 percent (or potentially deeper depending on the state’s budget condition).

In Line With Longstanding Legislative Priority, Cal Grant Funding Is Maintained. As part of the June 2024 budget agreement, the Legislature effectively decided to reduce programs elsewhere so that it could maintain funding for the state’s longest‑standing student financial aid program, the Cal Grant program. This program targets financial aid to students from low‑ and middle‑income families. It is notably more targeted than the MCS program. Whereas the Cal Grant program for low‑income students has an income cap of $69,000 (for a family of four in 2024‑25), and the Cal Grant program for middle‑income students has an income cap of $131,200 (for a family of four), the MCS program benefits families with annual income as high as $226,000. As a narrower needs‑based program, the Cal Grant program is designed to help those students most at risk of not being able to enroll in and complete college due to financial issues.

Non‑Proposition 98 Augmentations Come at the Expense of Other Priorities. Though preserving Cal Grant funding was an element of the two‑year budget agreement, the Governor is proposing a few higher education non‑Proposition 98 General Fund augmentations this year that were not part of that agreement. The Governor’s College Corps, Golden State Teacher Grants, and College of the Arts proposals total $75 million one‑time General Fund in 2025‑26, with ongoing costs for College Corps growing to $84 million in 2026‑27. We are still in the midst of evaluating these proposals, but each raises notable concerns and trade‑offs for the Legislature to consider, particularly as all of this new spending effectively is coming at the expense of other budget priorities.

Effects on Segments

Regular Cost Pressures Are Adding to Segments’ Fiscal Challenges. CSU’s and UC’s fiscal issues are being made more challenging because they, like community colleges, continue to face all of their typical cost pressures. The largest component of all three segments’ budgets is compensation. All three segments will continue to face pressure to increase employee salaries. All three segments also are projecting higher pension and health care costs in 2025‑26. (The state, however, directly pays a small share of community college pension costs, a large share of CSU pension costs, and all of CSU retiree health care costs.) Beyond compensation, smaller elements of the segments’ budgets also are expected to increase. For example, insurance costs, utilities, and equipment costs are expected to rise. The community colleges would be able to manage these typical cost increases more easily than the universities given they receive a COLA under the Governor’s budget. In contrast, CSU and UC would need to make room for any such costs by adjusting other parts of their budgets. Such adjustments could be particularly challenging for CSU, as it already directed campuses in 2024‑25 to accommodate certain compensation cost increases using existing funds, thereby requiring further savings to be found elsewhere within campus budgets.

University Reductions Will Have Some Campus Impact. Though the universities indicate they are still considering how they would respond to funding deferrals, they have identified the kinds of actions campuses could take in response to reductions in their state funding. As the 2024‑25 Budget Act already included small base reductions and indicated intent for deeper base reductions in 2025‑26, the systems already have begun planning and responding. Actions include leaving vacant positions open (hiring freezes), consolidating services, postponing some facility projects, reducing travel and other lower‑priority types of expenses, using reserves, and generating more revenue through self‑support programs. Campuses generally would have some discretion in making these choices. Some of these actions could affect students—leaving them potentially with larger classes, fewer course offerings, and student support services that could take longer to access. In turn, some students could take longer to graduate. Importantly, given projected total core funding is not changing much at either segment between 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, these types of programmatic reductions would emanate mostly from the projected cost increases (including salary and benefit costs) that the universities have identified.

Meeting Enrollment Expectations Entails Trade‑Offs. Both university systems anticipate exceeding the state’s enrollment expectations in 2024‑25 and are on track to meet the 2025‑26 expectations. Growing enrollment while not receiving associated state augmentations, however, would deepen the programmatic ramifications noted earlier. Historically, the state has provided “marginal cost funding” for the additional students it directs CSU and UC to enroll. In 2025‑26, the state marginal cost funding rate for CSU is $10,983 and for UC is $12,885. This funding is intended to allow CSU and UC to hire the additional staff and cover the additional operating costs that come with educating additional students. If UC and CSU were to continue growing without additional funding, they effectively would be covering the associated costs by making further programmatic adjustments, such as even larger class sizes. (In 2023‑24, the student‑faculty ratio was 19.9 at CSU and 21.9 at UC.) Both university systems have expressed concern about continuing to grow enrollment in the absence of additional state funding.

CSU’s and UC’s Uncommitted Reserves Are Not High as Share of Operating Expenses. Though reserves are one way to respond to temporary fiscal downturns, neither segment is carrying high levels of uncommitted reserves. As of June 30, 2024, CSU reported $2.4 billion in total core reserves. Of that amount, $777 million is reserved for economic uncertainties, which equates to 34 days of operations (or 9.1 percent of total annual core operating expenditures). UC reported $1.5 billion in total core reserves. Of that amount, $155 million is reserved for economic uncertainties. This amount equates to six days of operations (or 1.6 percent of total annual core operating expenditures). CSU’s reserve levels are lower than CSU’s reserve policy, which stipulates that reserves cover between three and six months of operating expenses. UC does not have a systemwide policy requiring campuses to hold a minimum level of reserves for economic uncertainties, but all UC campuses are below their own uncommitted reserve targets, which typically range from one to three months of operating expenses. Both systems’ reserves also are lower than general fiscal best practices. The Government Finance Officers Association historically has recommended that government agencies hold at least two months of unrestricted budgetary fund balances (though exceptions are considered depending on certain factors such as the size of the agency, its diversification of revenue streams, the volatility of those revenue streams, and overall risk exposure).

Recommendations

In this section, we provide a few budget recommendations for the Legislature.

Recommend Signaling More Realistic Budget Expectations for CSU and UC in 2026‑27. To balance the budget in 2024‑25, the state applied small General Fund reductions to CSU and UC. At the same time, the state provided a clear signal to CSU and UC that they were to begin planning for deeper base reductions in 2025‑26. Such an approach gave the university systems time to plan and make the associated difficult adjustments within their budgets. Given the state’s projected budget deficit in 2026‑27, the state likely will not have budget capacity to support substantial increases in General Fund spending for any programs, including for CSU and UC. Rather than continuing with the deferral plans and committing to out‑year funding increases, we recommend sending a more realistic signal to CSU and UC that they might not receive any increases in their base funding in 2026‑27. We think signaling this expectation is more helpful to the universities than setting an explicit expectation they will receive substantial additional state funding in 2026‑27, without any specific plan to ensure that funding is forthcoming. It also avoids having the state create new fiscal obligations it cannot currently afford. If the state’s fiscal condition improves over the next year, the Legislature could consider providing base increases for the universities at that time.

Recommend Aligning State Funding With Enrollment Expectations. As the Legislature traditionally has done, we recommend it continue to link the universities’ General Fund support with specified enrollment targets. If no additional General Fund support is provided, we recommend the Legislature hold CSU’s and UC’s enrollment targets flat for one year. This would help maintain the universities’ programmatic quality at existing levels. If more General Fund resources materialize, the Legislature could provide state marginal cost funding to support more enrollment at one or both segments. It also could continue funding UC for replacing nonresident students at high‑demand campuses with resident students. Given the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget is much more constrained at this time than the Proposition 98 side of the budget, supporting CSU and UC enrollment growth is much more challenging than supporting CCC enrollment growth. Given Proposition 98 funding is growing, and some colleges are exceeding their existing enrollment targets, the Legislature could consider funding more CCC enrollment growth than the Governor’s budget does. Funding more CCC enrollment growth could have added benefit at a time when some students effectively might be redirected to the colleges by one or more of the university systems.

Recommend Requiring Strong Case Be Made for Any New Higher Education Spending. Given projected out‑year budget deficits, we recommend the Legislature set a high bar for any new General Fund spending, as new spending now could come at the expense of existing programs the following year. In this vein, we recommend the Legislature examine the Governor’s proposals relating to Golden State Teacher Grants, College Corps, and College of the Arts especially carefully, as they would be funded from the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget. The Legislature also could examine the Governor’s proposed new initiatives relating to CCC technology and career education carefully, potentially replacing one or more of these Proposition 98 proposals with other CCC activities it deems of higher budget priority. Overall, as basic alternatives to the Governor’s proposals, the Legislature could consider funding other activities it deems of higher statewide priority or making larger reserve deposits to help address future budget challenges.