Lisa Qing

March 5, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

California Community Colleges

- Introduction

- Overview

- Apportionments

- Select Categorical Programs

- Enrollment

- Rising Scholars Network

- Common Cloud Data Platform

- Common Enterprise Resource Planning System

- Credit for Prior Learning

- Career Passports

Summary

Brief Covers the California Community Colleges (CCC). This brief analyzes the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending proposals for CCC. It covers apportionments, selected categorical programs, enrollment growth, the Rising Scholars program, two information technology (IT) projects, and two career education initiatives.

Proposed Apportionments Increase Is Reasonable. The Governor’s largest ongoing proposal for CCC is $230 million for a 2.43 percent cost‑of‑living‑adjustment (COLA) for apportionments. This general purpose funding would help community college districts address their core operating costs, including continued salary pressures, rising pension contributions, and higher health care premiums. The Legislature will receive an updated COLA rate in the spring. We recommend approving the COLA for apportionments as long as Proposition 98 funding remains sufficient to cover the associated cost.

Recommend Prioritizing Funding for Enrollment Growth. The Governor proposes $30 million ongoing for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth. In 2025‑26, community colleges could see enrollment pressures due to several factors, including regional demographic trends, elevated unemployment rates, some districts exceeding their current targets, and potential constraints on California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) enrollment levels. We recommend funding at least the amount of enrollment growth proposed by the Governor. The Legislature could consider funding more growth by redirecting ongoing funds from proposals that are not well justified.

Recommend Rejecting Funding for Both IT Projects. The Chancellor’s Office recently launched the Common Cloud Data Platform, a demonstration project intended to make it easier for participating districts to share student data. The Governor proposes $29 million ongoing and $134 million one time to expand this platform to all districts. We think it would be premature to fund this expansion before the demonstration project is completed in June 2026. The Governor also proposes $168 million one time to develop a common enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. This would replace the existing IT systems that participating districts use to manage their core business functions. We have significant concerns with the lack of planning, large future costs, and other risks associated with this project.

Recommend Rejecting Funding for Both Career Education Initiatives. As part of his forthcoming Master Plan for Career Education, the Governor proposes $7 million ongoing and $43 million one time for a credit for prior learning initiative. Although we see potential state benefits in expanding credit for prior learning, we think it would be premature to approve these funds without better information on the outcomes of a similar initiative funded in 2024‑25. The Governor also proposes $50 million one time to develop “career passports” that allow individuals to display their skills and credentials. For this proposal, the administration has not provided a clear problem definition, evidence of likely benefits, or certain key details.

Recommend Maintaining a One‑Time Budget Cushion. Although we have concerns with the Governor’s specific one‑time spending proposals, we think his broader approach of designating some Proposition 98 funding for one‑time purposes is prudent. This approach creates a cushion that can help protect ongoing programs if the minimum guarantee declines. To maintain the cushion, the Legislature could use any funds redirected from the Governor’s one‑time proposals for other one‑time purposes, potentially including a discretionary deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on CCC. The CCC system is one of California’s three public higher education segments. The system consists of 115 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts located throughout the state, plus one statewide online community college administered by the Board of Governors. The colleges offer a breadth of academic programs, including lower‑division transferable coursework, career technical education, precollegiate basic skills instruction, and baccalaureate degrees in certain occupational fields. This brief analyzes the Governor’s 2025‑26 budget proposals for CCC. We begin by covering the Governor’s overall budget plan for CCC. The next eight sections of the brief focus on the Governor’s proposals relating to (1) apportionments, (2) select categorical programs, (3) enrollment growth, (4) the Rising Scholars Network, (5) the Common Cloud Data Platform, (6) the Common Enterprise Resource Planning system, (7) credit for prior learning, and (8) career passports.

Overview

In this section, we describe the Governor’s overall budget plan for CCC and provide a few overarching comments about it.

Governor’s Budget Plan

Total CCC Funding Is $19 Billion in 2025‑26 Under Governor’s Budget. This reflects a 1.6 percent increase over the revised 2024‑25 level. As Figure 1 shows, $13.6 billion (72 percent) of CCC support in 2025‑26 would come from Proposition 98 funds. Proposition 98 funds, which consist of state General Fund and certain local property tax revenue, cover community colleges’ main operations. An additional $682 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund would cover certain other costs, including debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC faculty retirement costs, and Chancellor’s Office operations. In recent years, the state has also provided non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain student housing projects.

Figure 1

Total CCC Funding Increases Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions, Except Funding Per Student)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change From 2024‑25 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$8,198a |

$9,048 |

$9,041 |

‑$6 |

‑0.1% |

|

Local property tax |

4,070 |

4,304 |

4,538 |

233 |

5.4 |

|

Subtotals |

($12,267) |

($13,352) |

($13,579) |

($227) |

(1.7%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Fund |

$610 |

$643 |

$682 |

$38 |

5.9% |

|

Lottery |

364 |

316 |

316 |

— |

— |

|

Special funds |

58 |

97 |

96 |

‑1 |

‑1.1 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,032) |

($1,057) |

($1,094) |

($37) |

(3.5%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$482 |

$482 |

$484 |

$2 |

0.3% |

|

Other local revenueb |

3,313 |

3,341 |

3,368 |

27 |

0.8 |

|

Subtotals |

($3,795) |

($3,823) |

($3,852) |

($29) |

(0.8%) |

|

Federal |

$446 |

$446 |

$446 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$17,540 |

$18,678 |

$18,971 |

$293 |

1.6% |

|

FTE studentsc |

1,100,665 |

1,100,406 |

1,098,575 |

‑1,831 |

‑0.2%d |

|

Funding per studente |

$11,145 |

$12,134 |

$12,361 |

$227 |

1.9 |

|

aIncludes $788 million in withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve. bPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. cReflects budgeted FTE students. dReflects the net change after accounting for the proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. eReflects Proposition 98 funding, including reserve withdrawals, per budgeted FTE student. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Beyond State Funds, Community Colleges Receive Support From Various Other Sources. Much of CCC’s remaining funding comes from enrollment fees, other student fees, and various local sources (such as revenue from facility rentals and community service programs). The Governor proposes no increase to enrollment fees for 2025‑26. Since summer 2012, CCC enrollment fees have been $46 per unit, or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year. Community college fees in California remain the lowest of any state and significantly below the national average. In 2023‑24, community college tuition and fees averaged approximately $5,300 nationally—about four times the CCC level.

Proposition 98 Per‑Student Funding Continues Growing Under Governor’s Budget. Under the Governor’s budget, the estimated average Proposition 98 per‑student funding level at the colleges in 2025‑26 is $12,361. This is $227 (1.9 percent) more than the revised 2024‑25 level. As a result of many Proposition 98 augmentations for community colleges, per‑student Proposition 98 funding has increased significantly over the past several years. It is approximately $1,900 (18 percent) higher than the inflation‑adjusted 2018‑19 level.

Governor Has Several Proposition 98 Spending Proposals for CCC. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor proposes a total of $752 million in new Proposition 98 spending for CCC across the budget window (2023‑24 through 2025‑26). Of this amount, $357 million is for ongoing augmentations and $395 million is for one‑time initiatives. The largest ongoing proposal is a 2.43 percent COLA for apportionments. Notably, the Governor also proposes $30 million ongoing to support 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth. The majority of the one‑time funding is related to two IT projects.

Figure 2

Governor Proposes New CCC Ongoing and

One‑Time Spending

Proposition 98 General Fund, 2023‑24 Through 2025‑26 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (2.43 percent) |

$230 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

30 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (2.43 percent)a |

30 |

|

Rising Scholars Network |

30 |

|

Common Cloud Data Platform |

29 |

|

Credit for prior learning |

7 |

|

Subtotal |

($357) |

|

One‑Time Initiativesb |

|

|

Common Enterprise Resource Planning System |

$168 |

|

Common Cloud Data Platform |

134c |

|

Career passports |

50 |

|

Credit for prior learning |

43d |

|

Subtotal |

($395) |

|

Total Changes |

$752 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and mandates block grant. bIn addition to these new one‑time initiatives, the Governor’s budget provides $10 million for LGBTQ+ centers in 2025‑26, marking the third year of a three‑year initiative totaling $30 million. cIncludes $2.6 million in reappropriated Proposition 98 funds. dIncludes $10 million in reappropriated Proposition 98 funds. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

Governor’s Budget Creates Proposition 98 Settle‑Up Obligation. As we discuss in The 2025‑26 Budget: Proposition 98 Guarantee and K‑12 Spending Plan, total spending on schools and community colleges in 2024‑25 under the Governor’s budget is $1.6 billion less than the estimated Proposition 98 guarantee in that year. If revenues remain unchanged, this would create a $1.6 billion settle‑up obligation to schools and community colleges that the state would need to pay in the future. State law does not specify what share of these funds would go to community colleges. If the Legislature were to allocate the funds in proportion to the split of other Proposition 98 spending in the Governor’s budget, then we estimate $171 million would go to community colleges.

Governor Also Proposes Bond Funding for Many CCC Capital Outlay Projects. In November 2024, voters approved Proposition 2, which authorizes $1.5 billion in state general obligation bonds for community college facilities. The Governor’s budget proposes to allocate the first round of Proposition 2 bond funds for community colleges. Specifically, he proposes providing a total of $51 million in bond funds to support the design phases of 29 new CCC capital outlay projects. The Governor’s budget also provides $29 million from an earlier state general obligation bond measure, Proposition 51, to support the construction phases of two continuing capital outlay projects. Our table, California Community Colleges Capital Outlay Projects, lists these projects and their associated costs. We plan to analyze these projects in a forthcoming publication.

LAO Comments

Plan Contains a Reasonable Mix of Ongoing and One‑Time Spending. The Governor proposes a certain mix of ongoing and one‑time Proposition 98 spending for CCC in 2025‑26. We think that mix is a reasonable starting point. Notably, designating some Proposition 98 funding for one‑time purposes creates a cushion that mitigates volatility in the guarantee. The expiration of one‑time costs could help the state accommodate a future reduction in the guarantee without having to cut ongoing programs. In The 2025‑26 Budget: Proposition 98 Guarantee and K‑12 Spending Plan, we recommend the Legislature designate at least as much Proposition 98 funding for one‑time purposes as the Governor proposes. Within the CCC budget, the Governor designates $341 million in funding that counts toward the minimum guarantee in 2025‑26 for one‑time purposes (consisting of $97 million for one‑time initiatives and $244 million for the repayment of costs deferred from 2024‑25).

Opportunities Exist to Focus Ongoing Spending on Core Costs. Beyond the one‑time spending, there is a limited amount of new ongoing Proposition 98 funding available in CCC’s budget. With these ongoing funds, we recommend prioritizing actions that address core cost increases, such as providing an apportionments COLA and funding enrollment growth. Most of the new ongoing spending in the Governor’s budget goes toward such purposes. However, the Governor also proposes ongoing spending increases for certain other purposes, such as the Rising Scholars Network, the Common Cloud Data Platform, and credit for prior learning. In building the CCC budget, the Legislature has opportunities to increase the amount of funding available for core costs by redirecting ongoing funds from proposals that are not well justified, as we discuss later in this brief.

Proposed One‑Time Initiatives Have Notable Drawbacks. Though the amount of one‑time spending in the Governor’s budget is reasonable, the specific proposals have drawbacks, as we discuss in the last four sections of this brief. Some of these proposals lack basic details and planning. For other proposals, the state does not yet know the outcomes of related existing efforts. In building the CCC budget, the Legislature has opportunities to redirect funding from these proposals toward its own one‑time priorities. In addition, it could consider using some of these funds to make a discretionary deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve. In last year’s budget package, the state withdrew the entire balance of this reserve to address a drop in the minimum guarantee in 2023‑24. Under the Governor’s budget, the state would make mandatory deposits into this reserve in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, ending 2025‑26 with a balance of $1.5 billion. This equates to 1.3 percent of Proposition 98 spending in 2025‑26. Discretionary deposits on top of this amount could further promote budget resiliency, helping to protect ongoing community college programs in the event the minimum guarantee were to fall in a future year.

Apportionments

In this section, we focus on apportionments, which is general purpose funding the state allocates to community college districts. Districts, in turn, use their general purpose funding to cover their core operating costs. We begin this section by providing background on community colleges’ core operating costs. We then explain how the state provides funding for those costs. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposal to provide a COLA for apportionments, assess the proposal, and provide a recommendation.

Cost Pressures

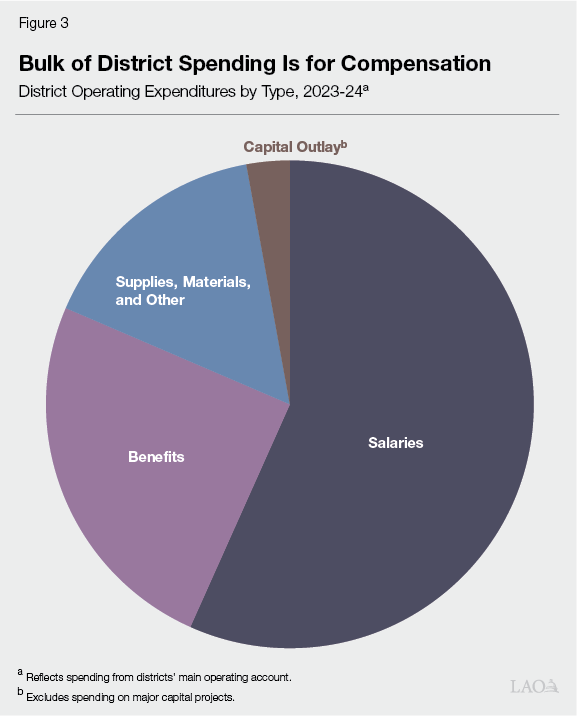

Compensation Is Largest Community College Operating Cost. Community college districts use the bulk of their apportionment funding on employee compensation. As Figure 3 shows, salaries and benefits (including retirement benefits, health care benefits, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance) accounted for more than 80 percent of district spending in 2023‑24. The remainder of a district spending was for various other core operating costs, including utilities, insurance, software licenses, equipment and supplies.

Staffing Has Rebounded to Pre‑Pandemic Level. At the start of the pandemic, as community college districts were facing steep enrollment declines, districts decreased their staffing levels. From fall 2019 to fall 2021, community college staffing statewide declined by 4.5 percent, falling from about 65,800 full‑time equivalent (FTE) employees to about 62,800 FTE employees. Since then, however, community college staffing has gradually rebounded to the pre‑pandemic level, reaching about 65,900 FTE employees in fall 2023. As enrollment has increased over the past two years, community college districts have increased staffing across all employee categories, including part‑time and full‑time faculty, support staff, and administrators.

Salary Decisions Are Made Locally. Most community college employees are represented by labor unions. Several unions represent faculty throughout the state, with the largest two being the California Federation of Teachers and the California Teachers Association. The California School Employees Association is the largest union for support staff. Each community college district negotiates with the local branches of their unions. Community college districts and their local unions make key compensation decisions, including salary decisions, through collective bargaining. Community college district governing boards—not the Legislature—ratify local collective bargaining agreements. When the state provides a COLA for apportionment funding, most districts in turn negotiate a COLA rate with their local unions. In negotiating this rate, districts typically account for a number of factors, including changes in housing and other costs for employees, the district’s salary competitiveness, and the district’s need to address non‑salary cost pressures. A small proportion of districts (likely less than 10 percent) automatically apply any state‑funded COLA rate to employees.

Salaries Have Been Generally Increasing. Over the past five years, salaries for community college employees generally have increased. For tenured and tenure‑track faculty, the average salary statewide has grown slightly faster than inflation, from about $99,300 in fall 2018 to about $122,500 in fall 2023. For support staff, the average salary statewide has grown at a similar rate to inflation, from about $61,100 in fall 2018 to about $74,600 in fall 2023.

Districts’ Pension Costs Also Have Been Rising. About half of CCC employees (faculty) participate in the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), while the other half (staff and administrators) participate in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). Because employer contribution rates for these two systems are set by their respective state boards, all community college districts statewide are subject to the same rates. Districts’ pension costs have been increasing over time. In 2014‑15, districts’ employer contribution rate was 8.9 percent of payroll for CalSTRS and 11.8 percent of payroll for CalPERS. In 2024‑25, those rates are up to 19.1 percent of payroll for CalSTRS and 27.1 percent of payroll for CalPERS.

Districts Regularly Face Various Other Cost Pressures. Similar to the other education segments, community college districts have faced recent increases in costs for health benefits, insurance, equipment, supplies, and utilities. Health benefits are the largest of these remaining cost pressures. In the past couple of years, districts have faced greater pressure in this area than normal because premiums have been increasing at historically high rates. District contributions to employee health premiums are collectively bargained. Districts commonly cover a large share of the premium increases for their full‑time employees. Coverage for part‑time employees varies widely among districts, though districts tend to cover a lower share of the cost increases for these employees.

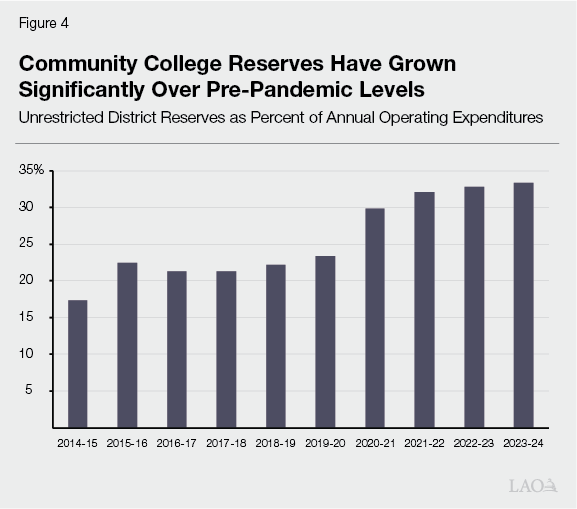

Systemwide Reserves Continue to Increase. Community college districts maintain local reserves to help manage revenue declines or unexpected costs. Based on best practices from the Government Finance Officers Association, the Chancellor’s Office recommends that districts maintain unrestricted reserves worth a minimum of 16.7 percent (two months) of annual expenditures. As Figure 4 shows, districts’ unrestricted reserves have increased over the past several years. Whereas unrestricted reserves totaled $1.8 billion (22 percent of expenditures) in 2018‑19, they grew to $3.5 billion (33 percent of expenditures) in 2023‑24. The increase in reserves over the past five years is likely the result of several factors—including significant increases in state funding, an influx of federal relief funds during the pandemic, and lower student enrollment and staffing levels during the pandemic.

Funding

Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Funding From Apportionments. All community college districts (except the statewide online Calbright College) receive funding from apportionments. In 2023‑24, community college districts collectively received $9.6 billion in apportionment funding. Apportionments account for about 70 percent of total Proposition 98 CCC funding.

State Has Formula to Determine Districts’ Apportionment Funding. Historically, districts received apportionment funding based almost entirely on student enrollment. In 2018‑19, the state adopted a new formula called the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). This formula is intended to create stronger incentives for colleges to enroll lower‑income students and improve student outcomes for them and overall. Under SCFF, districts receive apportionment funding for regular credit courses based on three components: (1) a base allocation linked to enrollment, (2) a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and (3) a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. These three components account for about 70 percent, 20 percent, and 10 percent of apportionment funding, respectively. Districts continue to receive apportionment funding for noncredit courses, as well as credit courses for dual enrollment students and incarcerated students, based entirely on enrollment.

Some Districts Are Receiving Additional Funding Through Hold Harmless Provision. When the state adopted SCFF, it created a temporary funding protection called “hold harmless” for those districts that would have received more funding under the previous apportionment formula. This provision was intended to provide time for those districts to ramp down their budgets to their new SCFF‑calculated amounts or find ways to increase the amount they generate through SCFF (such as by enrolling more low‑income students or improving student outcomes). Under this provision, districts receive whatever they generated in 2017‑18 under the old formula, adjusted for any subsequent COLAs provided by the state through 2024‑25. Districts are funded according to this provision if their hold harmless amount exceeds both their SCFF‑calculated amount and the stability amount discussed in the next paragraph. More than 25 districts were on hold harmless in each year from 2018‑19 through 2021‑22, before declining to only 12 districts in 2022‑23. (The decline in 2022‑23 was related to a $600 million augmentation the state provided to increase SCFF base funding rates, thereby decreasing the number of districts whose hold harmless amount exceeded their SCFF‑calculated amount.) In 2023‑24, the 11 districts remaining on hold harmless received $90 million in apportionment funding above their SCFF‑calculated amount. On average, these districts received more funding per student than other districts. The per‑student apportionment funding level was $9,574 across districts on hold harmless in 2023‑24, compared to $8,895 across districts that received their SCFF‑calculated amount.

Other Districts Are Receiving Additional Funding Through Stability Provision. State law also creates a second funding protection called “stability.” This provision allows a district to receive its SCFF‑calculated amount in the previous year adjusted for COLA. Districts are funded according to stability if the associated funding exceeds both their SCFF‑calculated amount for that year and their hold harmless amount. The number of districts on stability has fluctuated over the past few years. In 2023‑24, 26 districts were on stability, with these districts receiving $70 million in apportionment funding above their SCFF‑calculated amount. Like districts on hold harmless, districts on stability tended on average to receive more funding per student than districts that received their SCFF‑calculated amount. The per‑student apportionment funding level was $9,390 across districts on stability in 2023‑24.

“Basic Aid” Districts Also Are Receiving Additional Funding. Certain community college districts receive local revenue—primarily from property taxes—that exceeds the apportionment funding they would receive under SCFF, hold harmless, or stability. These districts are commonly referred to as basic aid districts. Basic aid districts retain their excess local property tax revenue, with none redistributed to other districts. Accordingly, these districts’ funding levels are much more closely tied to local property tax trends than the factors underlying the SCFF calculation and any COLA that might be applied to SCFF. In 2023‑24, there were eight basic aid districts. Given notable variations in their local property tax revenue, their per‑student apportionment funding amounts after accounting for the excess revenue ranged from $8,939 (Sierra) to $22,504 (Marin). All but one of these districts had per‑student apportionment funding rates that were higher than the systemwide average.

State Typically Provides a COLA for Apportionment Funding. Although the state is not statutorily required to provide a COLA for apportionments, it has a long‑standing practice of doing so when Proposition 98 funds are available. (In contrast, the state is statutorily required to provide a COLA for the Local Control Funding Formula [LCFF], which applies to school districts.) The COLA rate is based on a price index published by the federal government that reflects changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country. Over the past 30 years, the average COLA rate has been just under 3 percent. In some recent years, however, the COLA rate has been historically high—5.07 percent in 2021‑22, 6.56 percent in 2022‑23, and 8.22 percent in 2023‑24.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes COLA for Apportionments. The Governor’s budget includes $230 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to cover a 2.43 percent COLA for apportionments. This is the same COLA rate the Governor proposes for the K‑12 LCFF.

Assessment

Districts Face Several Notable Cost Pressures in 2025‑26. Although inflation has slowed notably since its peak in 2022, it remains above the historical average, likely translating to continued salary pressures in 2025‑26. Districts are also facing increased pension costs. Based on current assumptions, districts’ CalSTRS contribution rate is projected to remain at 19.1 percent in 2025‑26, but the CalPERS contribution rate is projected to increase to 27.4 percent (0.3 percentage points higher than in 2024‑25). Across both retirement systems, districts’ pension contribution costs are expected to increase by a combined $88 million in 2025‑26. In addition, districts continue to report that health care premiums are growing quickly. Beyond these employee compensation costs, districts generally are expecting increases in other costs such as insurance, utilities, and equipment in 2025‑26.

Additional COLA Data Is Forthcoming. In late January, the federal government released updated data on the price index that the state uses to calculate the COLA rate. Based on this data, we estimate the COLA rate for 2025‑26 is 2.26 percent—slightly lower than estimated under the Governor’s budget. The COLA rate will be finalized in late April, when the federal government releases the last round of data used in the calculation.

Providing a COLA for Apportionments Helps Districts Pay Core Costs. The proposed COLA rate for apportionments would help districts address anticipated cost increases for their core operations. Doing so would help maintain the quality of CCC’s core instructional programs, while also providing flexibility for districts to address particularly pressing local spending priorities. Historically, the Legislature has made providing a COLA for apportionments its top CCC budget priority for these reasons.

Certain Districts Are Not Expected to Receive a COLA in 2025‑26. Under state law, a new hold harmless policy is scheduled to take effect in 2025‑26. Under the new policy, a district’s hold harmless amount will be set at its apportionment level in 2024‑25, without any subsequent COLA adjustments. The intent of this policy is to phase down the additional funding that districts on hold harmless are receiving and gradually transition these districts onto SCFF. As the state continues to provide COLAs for SCFF, these districts’ SCFF‑calculated amounts will rise, and, at some point, exceed their hold harmless amounts. The more quickly these districts grow their enrollment and improve their outcomes, the more quickly their funding will begin to grow again. Though these districts will not see a COLA in 2025‑26, they will still benefit from receiving more per‑student funding, on average, than other districts with SCFF‑calculated funding levels.

Recommendation

Make COLA Decision Once Better Information Is Available This Spring. By the May Revision, the Legislature will have not only a finalized COLA rate calculation but also updated state revenue estimates. Those revenue estimates will, in turn, affect the amount available for ongoing Proposition 98 spending at CCC. If Proposition 98 resources in May remain sufficient to support the updated COLA, then we recommend the Legislature approve the proposal at that time. Providing a COLA for SCFF can help districts address their core operating cost increases, while helping to bring more districts that would otherwise be on hold harmless onto the formula.

Select Categorical Programs

In this section, we focus on CCC categorical programs. We first provide background on these programs, next describe the Governor’s proposal to provide a COLA for a subset of programs, and then raise an issue for legislative consideration.

State Funds Many CCC Categorical Programs. Whereas most CCC Proposition 98 funding is for apportionments and is intended to cover core instructional and operating costs, about 30 percent is for categorical programs. The state has more than 40 categorical programs. These programs provide community college districts with funding designated for specific purposes. The state is providing a total of $3.8 billion ongoing across all CCC categorical programs in 2024‑25. The five largest programs—the California Adult Education Program, the Student Equity and Achievement Program, Student Success Completion Grants, the Strong Workforce Program, and Extended Opportunity Programs and Services—account for more than half of that spending. The remaining programs serve a range of purposes, from financial aid administration and technology services to specific types of student and faculty support.

Underlying Costs Tend to Grow Over Time. As with apportionments, statute does not authorize an automatic COLA for any CCC categorical program. Nonetheless, categorical programs tend to experience cost pressures over time. The key cost drivers for some categorical programs are employee related, with costs rising as compensation increases. Some categorical programs also have enrollment‑related cost drivers, with costs rising as the number of program‑eligible students increases.

State Has Provided Increases for Select Categorical Programs. Historically, the Legislature’s CCC COLA decisions have been driven by the availability of Proposition 98 funding and its relative budget priorities. In some years, the Legislature has provided a COLA for a subset of categorical programs. As Figure 5 shows, the state has consistently provided a COLA for seven specific categorical programs in almost every year since 2019‑10. (In 2020‑21, the state did not provide a COLA for any CCC programs because it anticipated a significant budget shortfall due to the pandemic.) The state has also provided a COLA for certain other categorical programs in one or two of these years. Separate from providing a COLA, the state sometimes provides other funding increases to expand categorical programs. For example, the state increased funding for the Student Equity and Achievement Program by $24 million (5 percent) in 2021‑22 and another $25 million (5 percent) in 2022‑23.

Figure 5

Certain Categorical Programs Have Received a COLA in Recent Years

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

|

|

Academic Senate |

✔ |

|||||

|

Adult Education Program |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Apprenticeship programs |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

CalWORKs student services |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Campus child care support |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Disabled Students Programs and Services |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Extended Opportunity Programs and Services |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

Mandates Block Grant |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

MESA program |

✔ |

✔ |

||||

|

Middle College High School |

✔ |

|||||

|

NextUp foster youth program |

✔ |

|||||

|

Part‑time faculty compensation |

✔ |

|||||

|

Part‑time faculty office hours |

✔ |

|||||

|

Puente Project |

✔ |

✔ |

||||

|

Rapid rehousing |

✔ |

|||||

|

Student basic needs centers |

✔ |

|||||

|

Student mental health services |

✔ |

|||||

|

Umoja program |

✔ |

✔ |

||||

|

Veteran resource centers |

✔ |

|||||

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment and MESA = Mathematics, Engineering, Science Achievement. |

||||||

Governor Proposes to Provide Seven Categorical Programs With a COLA. The Governor’s budget includes a total of $30 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to provide seven CCC categorical programs with a 2.43 percent COLA. These are the same seven programs that have received a COLA in almost every year since 2019‑20. Figure 6 lists these programs and the cost of the associated COLA. More than half of the cost is for the California Adult Education Program, which supports precollegiate adult education at both community colleges and adult schools operated by school districts. (As we note in the “Apportionments” section, the data used to calculate the COLA will not be finalized until late April. The final rate could be slightly higher or lower than the Governor proposes, with corresponding changes in the associated cost.)

Figure 6

Governor’s Budget Includes Increases

for Select Categorical Programs

Reflects Funding for 2.43 Percent COLA (In Millions)

|

Program |

Cost |

|

Adult Education Program |

$15.9 |

|

Extended Opportunity Programs and Services |

5.3 |

|

Disabled Student Programs and Services |

4.2 |

|

Apprenticeship programs |

2.3 |

|

CalWORKs student services |

1.4 |

|

Mandates Block Grant |

1.0 |

|

Campus child care support |

0.1 |

|

Total |

$30.2 |

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

Proposal Is a Reasonable Starting Point, but Legislature Could Consider Other Options. Given that the Governor’s proposal includes many of the categorical programs the Legislature has prioritized for a COLA in recent years, it is a reasonable starting point for 2025‑26 budget deliberations. The Legislature could adopt the proposal, or it could choose to provide a COLA for a different set of categorical programs based on its priorities this year. Given the limited amount of ongoing CCC Proposition 98 spending under the Governor’s budget, the Legislature will face a trade‑off between providing more funding for categorical programs and reserving those funds for other ongoing budget priorities, such as enrollment growth.

Enrollment

In this section, we provide background on how the state funds community college enrollment, discuss recent enrollment trends, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund enrollment growth, assess the proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

Enrollment Is a Key Factor in Determining Apportionment Funding. Under SCFF, the largest factor in determining a district’s apportionment funding is its enrollment level. The SCFF enrollment calculation for regular credit courses is based on a three‑year average. Specifically, it uses the average of the FTE student count in that given year and the two previous years. In 2024‑25, the funded enrollment level based on the three‑year average is estimated at 1,064,141 FTE students systemwide. This is an estimated 4,432 FTE students (0.4 percent) higher than the reported enrollment level in 2024‑25.

In Certain Cases, Funding Is Based on Alternative Years of Enrollment Data. In 2024‑25, one key reason the systemwide funded enrollment level (using the three‑year average) is slightly higher than reported enrollment is a provision called the “emergency conditions allowance.” Under this provision, the Chancellor’s Office may use alternative years of enrollment data to calculate a district’s apportionment funding in extraordinary cases. During the pandemic, the Chancellor’s Office calculated apportionment funding for nearly all districts using pre‑pandemic enrollment data in place of their lower reported enrollment levels for 2019‑20 through 2022‑23. This affects the three‑year averages used to calculate districts’ apportionment funding through 2024‑25.

Districts With Recent Enrollment Declines Can Recover Apportionment Funding. When a district’s enrollment decreases, its SCFF‑calculated apportionment funding generally also decreases. Under state law, the district may subsequently increase its apportionment funding through a process called “restoration.” Through this process, a district is authorized to receive funding for adding back as many FTE students as it has cumulatively lost funding over the past three years. As its enrollment increases, its apportionment funding also increases until it uses up this authority. In 2024‑25, districts are adding back an estimated 14,802 FTE students through restoration.

State Allocates Enrollment Growth Funding Separately. Enrollment growth funding is provided on top of the funding generated from all other components of the apportionment formula. Growth funding supports enrollment increases at districts that have not seen recent declines in funded enrollment, as well as districts that already have used up their restoration authority. State law does not prescribe how to determine the amount of growth funding to provide CCC in any given year. Historically, the state has considered several factors, including changes in the adult population, the unemployment rate, prior‑year enrollment trends, and the availability of Proposition 98 funding. From 2021‑22 through 2024‑25, the state provided funding for 0.5 percent systemwide growth annually.

State Funds Enrollment Growth at a Per‑Student Rate. The per‑student rate varies by type of instruction. In 2024‑25, the base rate for regular credit courses is $5,294 per FTE student, with districts generating additional funding (on top of the base rate) for enrolling students who are low income or for attaining specified student outcomes. The base rate for dual enrollment students, incarcerated students, and most noncredit students is higher ($7,425 per FTE student), as districts do not earn additional funding based on these students’ income level or outcomes.

State Has Certain Rules for Allocating Enrollment Growth Funds Across Districts. State law directs the Chancellor’s Office to allocate enrollment growth funding across all districts using a formula that accounts for several local factors. These factors include the number of individuals within the district’s service area who do not have a college degree, are unemployed, or are in poverty. If a district does not fully use its enrollment growth allocation, then the remaining funds are redistributed to other districts that are growing beyond their initial growth allocation. State law caps the total amount of enrollment growth funded at any given district at 10 percent annually.

Recent Trends

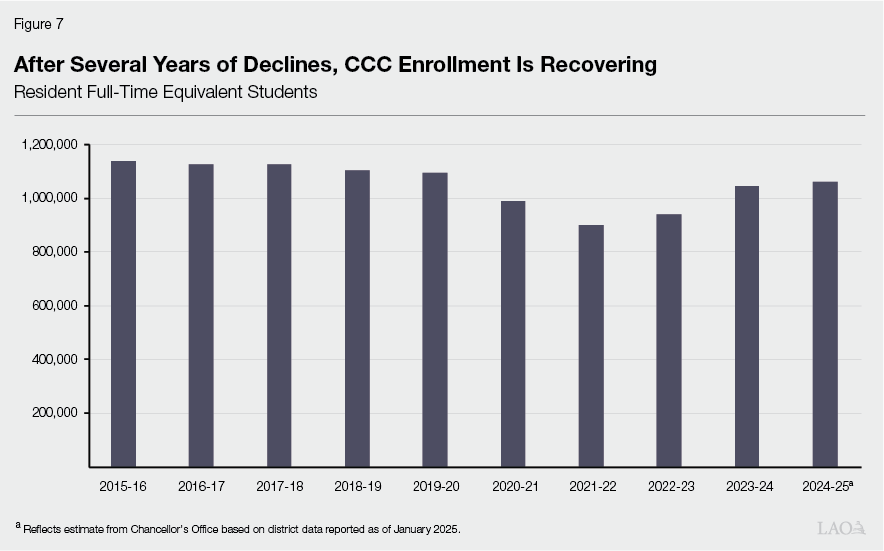

CCC Enrollment Declined Prior to and Especially During the Pandemic. As Figure 7 shows, CCC enrollment declined for much of the past decade. From 2015‑16 to 2019‑20, the enrollment decline was gradual. This trend has commonly been attributed to a long economic expansion, reflected in a strong labor market and historically low unemployment during that period. Historically, increases in unemployment have been accompanied by increases in community college enrollment, as more individuals return to school for training. The pandemic, however, was an exception. Due to the public health emergency, community college enrollment dropped notably even as unemployment temporarily surged. Between 2019‑20 and 2021‑22, the number of FTE students at CCC declined by about 195,000 (18 percent). This decline was consistent with national community college enrollment trends over the period.

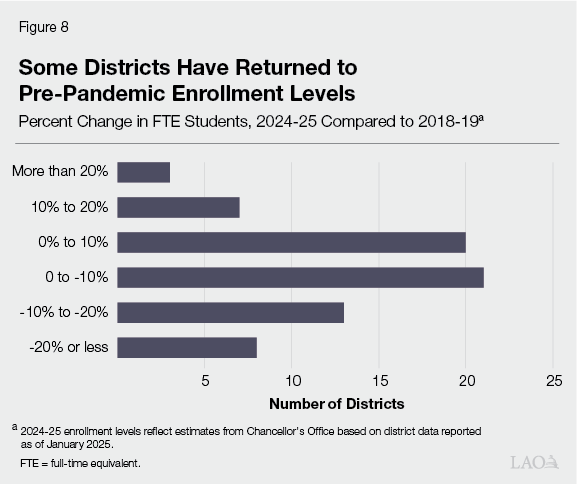

Enrollment Levels Are Now Recovering in Many Districts. After declining for several years, CCC enrollment began to increase again in 2022‑23. The number of FTE students increased by 4.4 percent in 2022‑23 and further increased by 11.3 percent in 2023‑24. The Chancellor’s Office recently released its initial estimates of 2024‑25 enrollment, based on data submitted by districts as of January 2025. Under these estimates, enrollment is on track to increase by an additional 1.3 percent in 2024‑25. With these increases, about 40 percent of districts were back at or above their pre‑pandemic enrollment levels in 2024‑25, as Figure 8 shows.

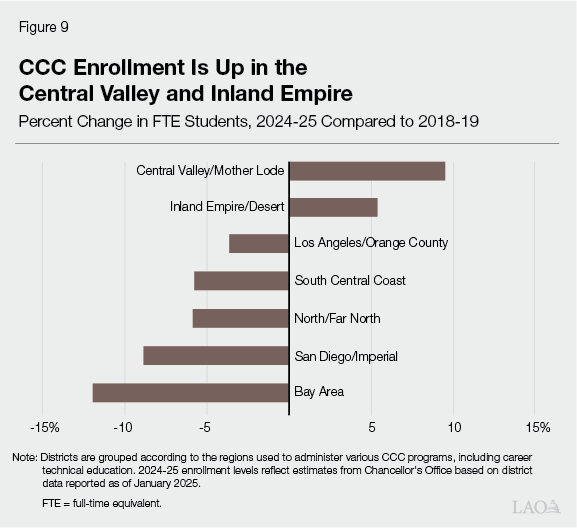

Enrollment Trends Have Varied Notably by Region. As Figure 9 shows, estimated CCC enrollment in 2024‑25 is up relative to pre‑pandemic levels in two regions: the Central Valley and the Inland Empire. This generally aligns with broader demographic trends, as these regions have experienced population growth since 2018‑19. In all other regions, estimated CCC enrollment remains below pre‑pandemic levels. The enrollment decrease has been largest in the Bay Area, a region that has experienced above‑average population declines over this period. Within each region, enrollment trends vary among some districts. In every region experiencing declining enrollment, one or more community college districts are growing despite the regional trend.

Several Factors Are Likely Contributing to Recent Enrollment Increases. In addition to demographic growth in certain regions, several other factors are likely contributing to the recent rebound in community college enrollment. The state’s unemployment rate has steadily increased over the past two years, from a low of 3.8 percent in September 2022 to 5.5 percent as of December 2024. This weaker labor market likely has led more individuals to return to school. Districts are also pursuing a variety of growth strategies, including expanding high school partnerships, reengaging students who recently dropped out of college, and offering more flexible courses (including courses with shorter terms and more frequent start dates).

Enrollment Is Shifting Toward Different Types of Instruction. Though the overall enrollment level is recovering, the mix of enrollment has changed somewhat compared to before the pandemic. In 2024‑25, enrollment in regular credit courses was approximately 71,000 FTE students lower than in 2018‑19, as Figure 10 shows. This decrease was partly offset by increases in other types of instruction, most notably dual enrollment courses for high school students. Dual enrollment at CCC rose from about 37,400 FTE students in 2018‑19 to an estimated 57,200 FTE students in 2024‑25—a 53 percent increase over just six years. During this time frame, noncredit enrollment also increased, though by a much lower rate (11 percent).

Figure 10

Dual Enrollment Is Growing Much Faster Than Other Types of Enrollment

Full‑Time Equivalent Students

|

Enrollment Category |

Description |

2018‑19 |

2024‑25a |

Change |

|

|

Number |

Percent |

||||

|

Regular Credit |

Students generally enrolled in lower‑division academic or CTE courses. |

990,925 |

919,920 |

‑71,005 |

‑7% |

|

Noncredit |

Adult students enrolled primarily in precollegiate basic skills, ESL, or CTE courses. |

70,300 |

77,907 |

7,607 |

11 |

|

Dual Enrollment |

High school students enrolled in credit‑bearing community college courses. |

37,370 |

57,246 |

19,876 |

53 |

|

Incarcerated Students |

Students currently incarcerated enrolled in credit‑bearing community college courses. |

4,697 |

4,636 |

‑61 |

‑1 |

|

Totals |

1,103,292 |

1,059,709 |

‑43,584 |

‑4% |

|

|

aReflects estimate from Chancellor’s Office based on district data reported as of January 2025. |

|||||

|

CTE = career technical education and ESL = English as a second language. |

|||||

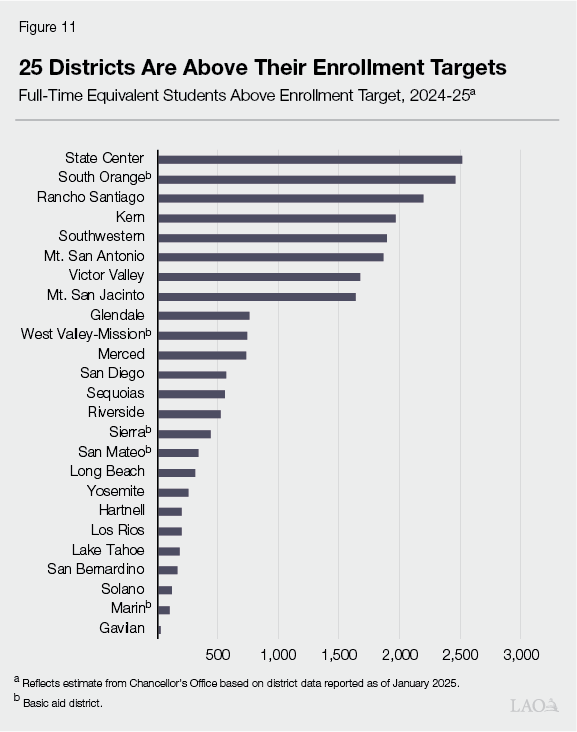

Some Districts Have Recently Grown Beyond Their Enrollment Targets. In 2024‑25, the state provided $28 million to support 0.5 percent enrollment growth systemwide. Districts are on track to fully use this available growth funding. Moreover, after accounting for this growth funding, 25 districts are on track to enroll more students than their 2024‑25 enrollment target. As Figure 11 shows, these districts are estimated to collectively exceed their enrollment targets by 22,420 FTE students, equating to 4.8 percent of their total enrollment. (Five of these districts, accounting for a combined 4,075 FTE students above the target, are basic aid districts.) The districts estimated to exceed their targets are located throughout the state, with districts in the Los Angeles/Orange County, Central Valley, and Inland Empire regions accounting for the majority of the students above the target. Districts that exceed their enrollment targets initially accommodate the associated impacts, commonly by having larger class sizes or opening up additional course sections. Subsequently, districts typically aim to realign their enrollment with their funding using various enrollment management strategies, such as adjusting their course offerings. Largely in response to some districts recently exceeding their targets, CCC is requesting the state fund a higher rate of enrollment growth—1.5 percent—in 2025‑26.

Proposal

Governor’s Budget Funds Some Enrollment Growth. The Governor’s budget includes $30 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth at CCC in 2025‑26. This equates to an estimated 5,439 additional FTE students. The average base rate for each of these students is $5,597. The proposed 0.5 percent growth rate is the same rate the state has adopted in each of the past four years.

Assessment

Statewide Demographic Trends Are Not Likely to Generate Enrollment Pressure in 2025‑26. Under both our office’s and the administration’s projections, the total adult population (ages 18‑59) in California is roughly flat in 2025‑26, compared to the previous year. The number of high school graduates is projected to decline by 3 percent in 2024‑25, which could lead to a smaller incoming class of traditional‑age college students in 2025‑26. This is particularly the case because college‑going rates among recent high school graduates have been roughly flat over the past few years for which this data is available. Taken together, these statewide demographic factors likely are not generating notable pressure for CCC enrollment growth in 2025‑26.

Regional Trends Could Create Some Enrollment Pressure. Though demographic pressures statewide are not likely to be significant in 2025‑26, certain regions of the state still are expected to experience growth in their adult population. When we map the administration’s county‑level population projections to community college regions, we find the adult population (ages 18‑59) in the Central Valley and Inland Empire regions are projected to continue growing at above‑average rates through 2028‑29. During the same period, the adult population is projected to decrease in the Bay Area and Los Angeles/Orange County regions. Under current law, the Chancellor’s Office will take local demographic factors into account when allocating new enrollment growth funding.

Labor Market Trends Could Continue to Generate Enrollment Pressure. Some districts also could see upward enrollment pressures for other reasons, including labor market trends. After climbing gradually for the past two years, California’s unemployment rate has reached 5.5 percent as of December 2024. This is above the pre‑pandemic unemployment rate (about 4 percent), though still below the historical average over the past 30 years (about 7 percent). Under our office’s projections, unemployment continues to increase in 2025‑26 and the out‑years. This trend could lead more individuals to enroll at the colleges.

Some Districts Likely Remain Above Their Enrollment Targets. Another upward enrollment pressure is related to the 25 districts that exceeded their enrollment growth targets in 2024‑25. Without new enrollment funding, these districts could begin employing enrollment management strategies (such as adjusting their course offerings) to constrain their growth. Conversely, with additional funding, these districts might continue on their stronger growth trajectories.

University Budget Constraints Could Increase CCC Enrollment Demand. A fourth reason CCC might experience upward enrollment pressure is related to state budget constraints affecting CSU and UC in 2025‑26. As we discuss in The 2025‑26 Budget: Higher Education Overview, the state might not have sufficient non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to support enrollment growth at CSU and UC in 2025‑26. If CSU and UC do not receive enrollment growth funding, more students might enroll at community colleges.

Recommendation

Prioritize Enrollment Growth Within Available Ongoing Funds. We recommend the Legislature fund at least the 0.5 percent enrollment growth proposed by the Governor. The Legislature could consider funding more enrollment growth—potentially up to the 1.5 percent requested by CCC—by redirecting funds from lower‑priority ongoing proposals. (We would not recommend redirecting funds from one‑time proposals toward enrollment growth, as this would reduce the one‑time cushion within the CCC budget.) Community colleges could see upward enrollment pressures from several fronts. Regional demographic trends, rising unemployment rates, enrollment in excess of existing targets, and potential constraints on CSU and UC enrollment levels all could drive up CCC enrollment levels in 2025‑26. Providing funding for additional growth could help districts maintain programmatic quality as they enroll more students. We estimate each additional 0.5 percent of enrollment growth would cost $30 million ongoing.

Rising Scholars Network

In this section, we provide background on the Rising Scholars Network, describe the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for this program, assess the proposal, and provide associated recommendations.

Background

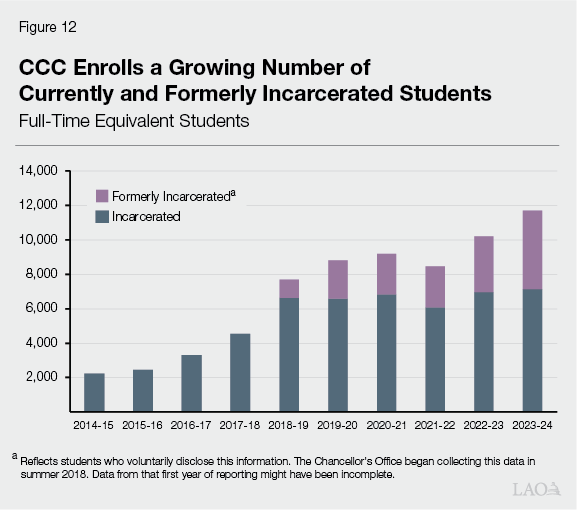

Some CCC Students Are Currently or Formerly Incarcerated. As Figure 12 shows, the number of incarcerated students enrolled at the community colleges has increased over the past decade—from about 2,200 FTE students in 2014‑15 to about 7,100 FTE students in 2023‑24. The majority of these students were in state prisons, and the remaining students were in other facilities such as county jails, county juvenile facilities, or federal facilities. (Juvenile facilities house youth up to age 23 or, in some cases, age 25.) Whereas colleges historically provided instruction to incarcerated students primarily through correspondence courses, they have been providing a growing amount of in‑person instruction over the past decade. Community colleges also enroll formerly incarcerated students. Based on data from the Chancellor’s Office, the number of formerly incarcerated students has doubled since 2019‑20, reaching about 4,500 FTE students in 2023‑24.

State Primarily Supports These Students Through Apportionments. For currently incarcerated students, the state provides colleges with apportionment funding based entirely on the number of these students they enroll. In 2023‑24, the state provided colleges collectively with $41 million in apportionment funding for incarcerated students in credit‑bearing courses. For formerly incarcerated students, the state provides colleges with apportionment funding based on the same factors used for the broader community college student population—enrollment, low‑income student counts, and specified student outcomes. We estimate the amount of apportionment funding for formerly incarcerated students was in the low tens of millions of dollars in 2023‑24. In addition to apportionments, a CCC categorical program provides $3 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for textbooks or digital course content for incarcerated students across all types of correctional facilities. Colleges may also use funding from certain other broader categorical programs, including the Student Equity and Achievement Program, to provide support services for currently and formerly incarcerated students. Data is not available on the amount of categorical funding colleges are using to support these students.

State Established Rising Scholars Network in 2021‑22. Chapter 558 of 2021 (AB 417, McCarty) established the Rising Scholars Network to provide support services to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated students enrolled in community college courses. The 2021‑22 budget package provided $10 million ongoing for this categorical program. These funds are to support up to 65 colleges in providing various services, including academic advising, tutoring, financial aid application assistance, and assistance accessing other campus and community resources. State law authorizes the Chancellor’s Office to designate up to 5 percent of program funding for program administration, development, and accountability. The Chancellor’s Office is required to report on December 31, 2023 and every two years thereafter on colleges’ efforts to serve currently and formerly incarcerated students.

Just Over Half of Colleges Are Participating in Original Program. In 2022, the Chancellor’s Office awarded the Rising Scholars Network funds through a competitive process that accounted for a college’s readiness based on its current programs and services for currently or formerly incarcerated students. Of the 68 applicants, 59 were selected for awards of between $100,000 to $190,000 annually through 2024‑25. Two of the selected applicants were multi‑college districts, bringing the total count of participating colleges potentially up to 62—just under the cap of 65. The remaining applicants did not receive the minimum number of points to be eligible for funding. Based on information from the Chancellor’s Office, participating colleges are spending the majority of their program funds on personnel, including staff to provide specialized support for currently and formerly incarcerated students and instructional designers to adapt courses to be delivered in correctional settings. Other program expenses include technology, classroom space, and professional development.

State Added Juvenile Justice Component to Program in 2022‑23. The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $15 million ongoing to add a new component to the Rising Scholars Network that focuses on youth impacted by the juvenile justice system. The majority of these funds are to support up to 45 colleges in providing instruction and support services (such as basic needs assistance and education planning) on campus and in local juvenile facilities. Of the total program funding, $1.3 million is designated for technical assistance, including staff to oversee program implementation and provide training and support. In addition, $750,000 was designated on a one‑time basis in 2022‑23 for a program evaluation that examines the first cohort of participating colleges over a period of at least five years. Since 2022‑23, the state has retained the provisional budget language funding this program.

Some of Same Colleges Are Participating in Juvenile Justice Component. In 2023, the Chancellor’s Office awarded the juvenile justice funds through a competitive process. Of the 47 colleges that applied, 44 colleges received awards of $312,500 annually through 2026‑27. (Each college’s award amount was slightly lower in 2022‑23 because of the one‑time set‑aside for a program evaluation.) Two colleges that applied for the program did not receive awards, and one college declined an award. Most of the colleges participating in the juvenile justice component of the program are also participating in the original component focused on adult students. In total, 75 colleges are participating in one or both program components in 2024‑25. As with the original component, colleges are spending the majority of program funds from the juvenile justice component on personnel costs.

Proposal

Governor Proposes to Increase Funding for Rising Scholars Network. The Governor’s budget increases funding for the Rising Scholars Network by $30 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund, bringing total program funding to $55 million. The Governor proposes trailer bill language removing the cap on the number of colleges participating in the adult component of the program. (Budget bill language would continue to limit participation in the juvenile justice component to 45 colleges.) The administration proposes no changes to program requirements for either the adult or juvenile components.

Assessment

Increasing Support for Incarcerated Students Could Have Benefits. As we discuss in our report, Assessing Community College Programs at State Prisons, some research conducted in other states has identified benefits to higher education for incarcerated students, including reductions in recidivism. Support services might help these students attain their educational goals. Data is not available on the amount or the impact of support services provided to incarcerated students in CCC courses. Based on the meetings and site visits we conducted for this report, however, relatively few counselors advise incarcerated students, and these students typically do not have access to trained tutors.

Proposed Funding Increase for Rising Scholars Network Is Relatively Large. The Governor’s proposed $30 million increase for the Rising Scholars Network would more than double the ongoing program funding level. It is also three times the increase requested by the Chancellor’s Office in the CCC 2025‑26 budget request for this purpose ($10 million). The administration has not provided a strong rationale for proposing such a significant increase for the program. Notably, the administration has not offered evidence of demand among additional community colleges for this amount of program funding.

Proposal Lacks Clarity on Intended Use of Funds. The proposed trailer bill language does not specify whether the additional funding is intended for the adult component or the juvenile justice component of the program, each of which has different rules. It also does not specify whether the funds are intended to support currently or formerly incarcerated students—two student groups that may have differing needs and differing access to support services. In addition, it does not specify how the Chancellor’s Office is to allocate the funds among interested colleges, including how much grant funding each college would be eligible to receive. The administration indicates that the Chancellor’s Office would have flexibility to make these types of decisions.

State Does Not Yet Know Outcomes of Current Program. In March 2024, the Chancellor’s Office submitted the first of its biennial reports to the Legislature on its efforts to serve currently and formerly incarcerated students. The report provides data on enrollment and outcomes for these student groups from 2018‑19 through 2020‑21—the three years prior to the state establishing the Rising Scholars Network. Our office has requested data from the Chancellor’s Office on student outcomes since the program was established in 2021‑22. As of this writing, we have not yet received this data. In addition, the program evaluation the state funded in 2022‑23 budget has not yet begun. The Chancellor’s Office indicates they are currently developing a request for proposals for this evaluation.

Recommendations

With Limited Available Ongoing Funds, Prioritize Supporting Core Programs. As we discuss in the “Overview” section, we recommend the Legislature prioritize ongoing funding for core costs. We recommend considering other program expansions only if ongoing funding remains available after these core costs are addressed. Regarding the Rising Scholars Network, we caution against significantly expanding this program before the state has any information on its outcomes to date. Over the next few years, the Legislature expects to receive more information on how the program is going, including the results of the evaluation it funded in the 2022‑23 budget. After it has this information, it will be in a better position to revisit various aspects of the program, including its funding level. In the meantime, the Legislature could reject the proposed augmentation for 2025‑26 and (1) redirect the funds to other ongoing priorities, (2) designate the funds for one‑time purposes, or (3) make a discretionary deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve. Either of these last two options would result in a larger budget cushion for protecting existing core community college programs moving forward.

Consider Other Approaches to Supporting Incarcerated Students. Although the state has limited budget capacity to expand programs such as the Rising Scholars Network, it has other options to improve support for incarcerated students without incurring additional net costs. Our report, Assessing Community College Programs at State Prisons, contains two recommendations related to this objective. First, in that report, we recommend modifying SCFF to include a performance component for incarcerated students (as it does for most other students), thus creating better incentives for colleges to help these students attain their educational goals. Second, in that report, we also recommend using untapped federal Pell Grants to cover enrollment fees, textbooks, and technology costs for incarcerated students. This would free up state funding currently going toward these purposes, which the Legislature could in turn use for other purposes, such as providing additional support for incarcerated or formerly incarcerated students. We estimate this would free up approximately $9 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund as well as non‑Proposition 98 General Fund in the low tens of millions of dollars.

Common Cloud Data Platform

In this section, we first provide background on the Common Cloud Data Platform, a demonstration project the Chancellor’s Office launched to provide shared access to student data across participating districts. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to expand this platform systemwide, assess that proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

Background

Each District Maintains Its Own Student Data. Community colleges collect various types of student data, including data on enrollment, demographics, academic outcomes, and financial aid. Each district stores this student data in an IT system called an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. (Districts also use their ERP systems for many other purposes, as we discuss in the next section of this brief.) The Chancellor’s Office does not have direct access to this data. Instead, it requires districts to report certain data, including on enrollment and student outcomes, periodically during the course of the year. These district reports are in turn used for various systemwide purposes, including determining apportionment funding and complying with state reporting requirements.

Chancellor’s Office Recently Launched Demonstration Project to Share Student Data More Easily. In October 2023, the Chancellor’s Office launched a demonstration project called the “Common Cloud Data Platform.” The goal of this project is to develop a platform through which the Chancellor’s Office and participating districts could share student data on a “near real‑time” basis. The platform would be compatible with districts’ existing ERP systems. By making the sharing of student data easier, this project is intended to streamline certain systemwide reporting processes. It is also intended to enable the development of data analytics tools, such as timelier enrollment and student outcomes dashboards, which the Chancellor’s Office indicates could improve decision‑making and student support. The Chancellor’s Office is supporting this demonstration project using $10 million in one‑time funds set aside from the Student Equity and Achievement Program. (Under state law, the Chancellor’s Office may designate up to 5 percent of funding for that program for systemwide activities.) Currently, six districts—representing a range of sizes, locations, and ERP systems—are participating in the demonstration project. The Chancellor’s Office is preparing to add a second cohort of about six more districts to the project over the next few months.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Expanding Student Data Platform Systemwide. The Governor’s budget provides $163 million Proposition 98 General Fund ($29 million ongoing and $134 million one time) for the Common Cloud Data Platform. Based on the proposed trailer bill language, the funds would be used to develop and expand the platform to all districts, incorporate new analytics tools, and support related data quality assurance and governance processes. The Chancellor’s Office would allocate these funds to a district or districts to administer these activities under its oversight. (The state commonly takes this approach with CCC systemwide initiatives to ensure that Proposition 98 General Fund is allocated to local educational agencies.) The language directs the Chancellor’s Office to submit a report on the project’s implementation status to the Legislature by January 31, 2028. The language does not specify how long the funds would be available for expenditure.

Assessment

Demonstration Project Is Still Underway. The Common Cloud Data Platform demonstration project provides an opportunity for the Chancellor’s Office to develop and test the platform with a small group of districts, assess the outcomes, and apply the lessons learned toward future decisions about expanding the platform. The Chancellor’s Office anticipates completing the demonstration project in June 2026. We do not see a clear rationale for funding the systemwide expansion of this platform before the demonstration is complete and the Legislature has information on its outcomes.

More Information Is Needed on Project’s Benefits. While expanding the Common Cloud Data Platform systemwide could lead to more efficient reporting processes, these administrative efficiencies are unlikely to be enough on their own to justify a project of this size. To better understand the justification for systemwide expansion, the Legislature would likely want more information on the state benefits of having more timely student data, relative to the data currently available. For example, the Legislature may want specific examples of how near real‑time data is needed for state decision‑making. Real‑time data likely is most useful at the local level, where it could help instructors and counselors better support specific students. It is unclear, however, whether this project would significantly improve the data that districts have on their own students, except to the extent those students are also enrolled at other participating institutions.

Proposed Funding Level Could Exceed Project Costs. The $163 million included in the Governor’s budget is based on CCC’s 2025‑26 systemwide budget request. In that request, however, this amount was intended to cover not only the expansion of the Common Cloud Data Platform but also the launch of the Common ERP project (which we discuss in the next section of this brief). We think that the full amount likely would not be needed for the Common Cloud Data Platform alone. A January 2025 Board of Governors meeting agenda cites a significantly lower cost ($96 million one time to be spent across several years) for expanding the Common Cloud Data Platform systemwide. The Chancellor’s Office indicates, however, that this cost estimate is not final.

Recommendation

Reject Funding at This Time and Require Reporting on Demonstration Project. Given the issues above, we think it would be premature to fund the systemwide expansion of the Common Cloud Data Platform. Instead, we recommend requiring the Chancellor’s Office to report on the current demonstration project upon its completion. The report could cover the outcomes of the project for participating districts, any challenges encountered and lessons learned, the projected state and local benefits of expanding the platform systemwide, a refined cost estimate for that expansion, and an analysis of alternatives and their respective costs. This information would be similar to the information provided to the Legislature for other IT projects through the state’s IT project approval process, as we discuss in the nearby box. The Legislature could require the Chancellor’s Office to report on these items by October 30, 2026. This is a few months after the completion of the demonstration project and a few months before the start of the state’s 2027‑28 budget process. If the Legislature decided to expand the platform based on the demonstration project’s results, it could initiate state funding in 2027‑28, funds permitting.

Common Enterprise Resource Planning System

In this section, we first provide background on the ERP systems that districts use to manage their core business functions. We then describe the Governor’s proposal to develop a common ERP across multiple districts, assess that proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

Background

Each District Has Its Own ERP System. Community college districts use their ERP systems to manage numerous functions relating to student information, finance, and human resources. Currently, each district contracts separately with a vendor for its ERP system, with nearly all districts using one of three main products. Each district also employs its own IT staff to administer and maintain its ERP system. The Chancellor’s Office believes this approach has several drawbacks—including inconsistencies in the technology experience for students and employees across the system, information security vulnerabilities at districts with outdated ERP systems, and IT staffing challenges at smaller districts.

Chancellor’s Office Recently Initiated a Common ERP Project. In February 2024, the Chancellor’s Office convened a task force to provide input on systemwide technology issues. One issue the task force considered was the development of a common ERP—a centrally administered IT system that would replace existing, locally administered IT systems. At the conclusion of the task force, the Chancellor’s Office decided to continue exploring the development of an opt‑in common ERP system with interested districts. In November 2024, the Chancellor’s Office began the planning process for this project with a group of about a dozen districts.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Funding for a Common ERP Project. The Governor’s budget provides $168 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for this purpose. Under the proposed trailer bill language, the funds would be used to develop, implement, and expand the Common ERP project and support related data governance activities. The Chancellor’s Office would allocate these funds to a district or districts to administer these activities under its oversight. The language directs the Chancellor’s Office to submit a report to the Legislature containing a project time line, budget, and progress update by January 31, 2027. It also directs the Chancellor’s Office to submit a second report to the Legislature on the project’s implementation status by January 31, 2030. The language does not specify how long the funds would be available for expenditure.

Assessment

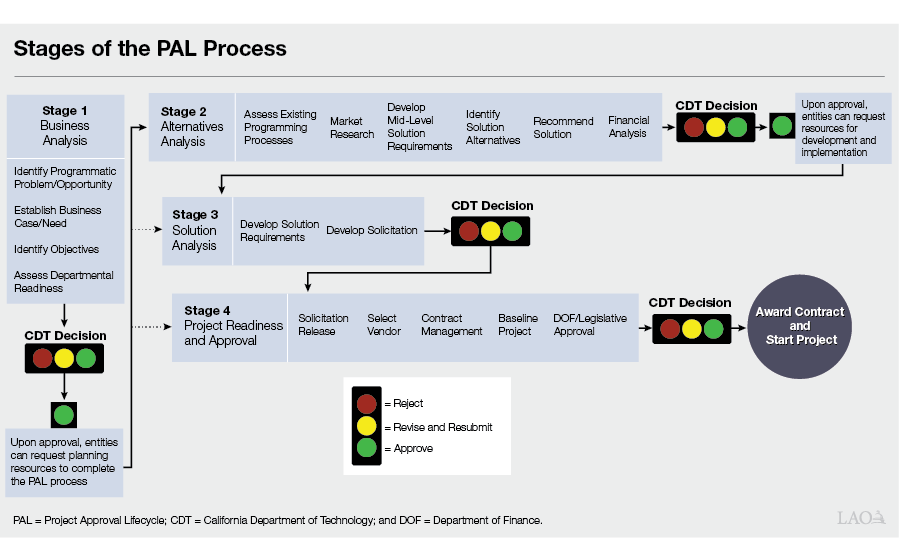

Project Has Not Undergone Typical Planning Process. Most state IT projects undergo a planning process managed by the California Department of Technology (CDT), in consultation with the Department of Finance, called the Project Approval Lifecycle (PAL). The box below describes this process. Because the Chancellor’s Office is considered an independent agency outside of CDT’s authority, its projects are not required to go through the PAL process. The Common ERP project has not undergone a comparable planning process, and the documentation currently available on this project is not equivalent to what the Legislature typically receives for other state IT projects.

State Information Technology (IT) Project Approval Process

State Has Standard Approval Process for Most IT Projects. Historically, the state has experienced considerable challenges successfully implementing IT projects. In 2016, the California Department of Technology (CDT) implemented a new project approval process—known as the Project Approval Lifecycle (PAL)—with the goal of helping bolster project planning and reduce the likelihood of project challenges or failure. As the figure below shows, the PAL process has four stages. Each stage requires departments to conduct specific planning‑related analyses and submit an associated planning document to CDT for approval. Collectively, these documents form a comprehensive plan for implementing the proposed project. These documents can give the Legislature a better understanding of—and more confidence in—the project cost, schedule, and scope prior to approving funding for project implementation through the annual budget process. Whereas current policy requires most state agencies to use the PAL process, the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office and community college districts are not required to go through the process.

Alternatives to Achieving Project Objectives Have Not Been Thoroughly Studied. The first and second stages of the PAL process, respectively, require departments to identify project objectives and evaluate various alternatives for accomplishing those objectives. While the Chancellor’s Office has identified several potential objectives for a systemwide technology project, it has not thoroughly evaluated the alternatives for accomplishing those objectives. Some of these alternatives might be more cost‑effective or lower risk than the proposed Common ERP project. For example, districts with outdated ERP systems could turn to the Foundation for California Community Colleges to negotiate better pricing through its shared procurement program. Alternatively, these districts could create a joint powers authority to pool their IT resources and expertise, leveraging their larger combined size to negotiate better prices. Without an analysis of these types of alternatives, the Legislature cannot determine whether the Common ERP project is the best way to address the identified objectives.

State Lacks Basic Information on Project Scope, Schedule, and Cost. The trailer bill language does not specify how many districts are to participate in the Common ERP project or whether the intent is to implement it systemwide. The Chancellor’s Office indicates, however, that its intent is to eventually implement the project at all districts over multiple waves. Implementing a project of this scope would require significant time and costs. Whereas the Legislature typically has information on a project’s schedule and cost prior to approving funding for development and implementation, it would not receive this information on the Common ERP project until well afterward. Under the proposed trailer bill language, the report due to the Legislature by January 31, 2027 would include a project time line and “the budget and expenditures of resources appropriated, and any identified one‑time and future funding needs necessary for completing the work.”