Ryan Miller

March 6, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

Understanding Recent Increases in

the Medi‑Cal Senior Caseload

- Background

- Recent Trends in the Senior Caseload

- What is Causing the Growth in the Senior Caseload?

- Issues for Legislative Consideration

Summary

Recent Growth in Medi‑Cal Senior Caseload Due Mostly to Eligibility Expansions. As of December 2024, the senior caseload in Medi‑Cal stands at 1.4 million, about 40 percent higher than at the start of the continuous coverage period that began in 2020 as a response to the COVID‑19 pandemic. This brief explores the causes of this growth. We find that the senior caseload is around 225,000 higher than it would have been under a pre‑pandemic law and policy baseline. We estimate that at least 165,000 of these individuals are enrolled due to eligibility expansions, with the remaining up to 60,000 individuals enrolled due to the continuous coverage requirement and the related flexibilities implemented during its unwinding.

Growth Raises Issues for Legislative Consideration. Our findings show that, to a greater extent than initial estimates suggested would be the case, the Legislature’s policy choices to expand Medi‑Cal eligibility for seniors are having their intended effects. In particular, asset test elimination appears to have been particularly effective at extending Medi‑Cal coverage to seniors. That said, it will be important for the Legislature to monitor the extent to which senior growth continues to grow in the context of a constrained state budget. Given this sizable growth in the senior caseload—many of whom are enrolled in Medi‑Cal for the first time—we raise issues that we think merit legislative oversight.

Background

Seniors in Medi‑Cal

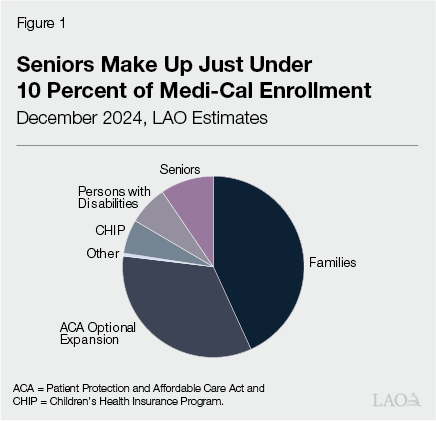

Seniors Are a Small Caseload in Medi‑Cal. Figure 1 shows our estimates of the composition of Medi‑Cal enrollment as of December 2024. As the figure shows, families are the largest category of Medi‑Cal enrollees, followed by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) optional expansion population (childless adults ages 19 through 64), seniors, persons with disabilities, children in the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and other enrollees. Together, families and the ACA population make up about three‑quarters of Medi‑Cal enrollment. Seniors make up just under 10 percent of Medi‑Cal enrollment.

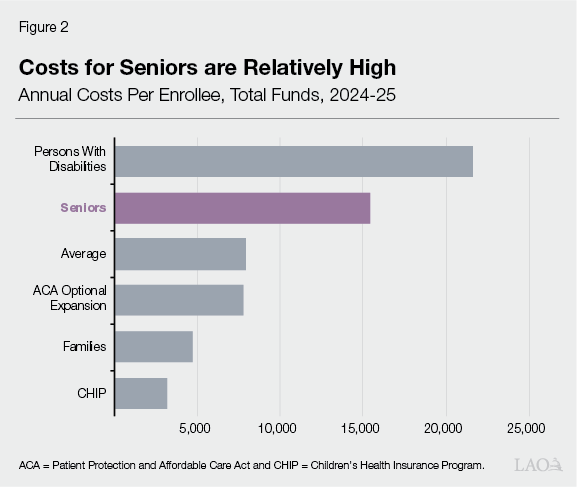

State Costs Are Higher for Seniors. Figure 2 shows per‑enrollee costs for each of the caseload categories. As the figure shows, seniors are a relatively costly category in Medi‑Cal, with annual costs per enrollee of around $15,000 (total funds). This compares to the average annual cost per enrollee of about $8,000 (total funds) across all caseload categories. Unlike the ACA and CHIP populations, for which the federal government provides an “enhanced” match of 90 percent and 65 percent, respectively, services provided to seniors, like families and persons with disabilities, receive a standard 50 percent federal match. (The federal government provides an enhanced match for certain functions and services that apply to all enrollees regardless of enrollment category.) While higher health care costs are expected as people age, seniors also carry higher state costs due to the standard federal reimbursement rate.

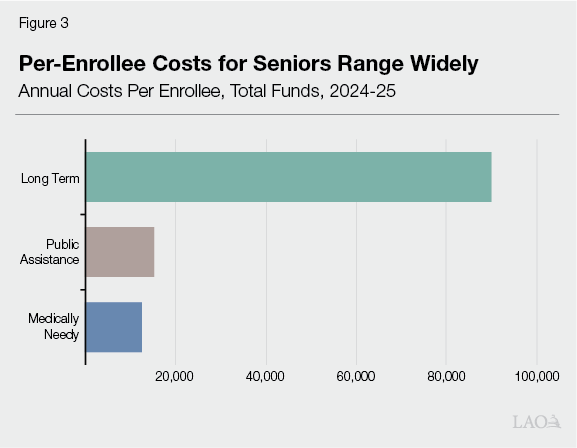

Within Senior Category, Costs Vary Widely. As budgeted in the Medi‑Cal estimate, the senior category is the total of three aid categories—seniors receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) (budgeted as Public Assistance), seniors receiving long‑term care in settings such as skilled nursing facilities (budgeted as Long Term), and all other non‑disabled seniors (budgeted as Medically Needy). Programs in the Medically Needy category include the aged, blind, and disabled federal poverty level (ABD FPL) program and those enrolled in share‑of‑cost Medi‑Cal. As of December 2024, about two‑thirds of seniors enrolled in Medi‑Cal are in the Medically Needy category, with another 30 percent in the Public Assistance category. Less than 3 percent of seniors are in the Long‑Term category. Figure 3 shows the per‑enrollee costs for these three aid categories. As shown in the figure, total annual costs per senior ranges widely, with costs for those in institutional care, such as skilled nursing facilities, totaling nearly six times the next most costly aid category of Public Assistance.

Recent Policy Changes Impacting Seniors

Asset Test Elimination

Prior to January 2024, Medi‑Cal Eligibility for Seniors Based in Part on Complex Rules Limiting Assets. Beginning January 1, 2015, the ACA created a simpler process (known as the Modified Adjusted Gross Income, or MAGI, methodology) for determining eligibility for most Medi‑Cal applicants. Seniors and persons with disabilities, however, continued to apply under “non‑MAGI” rules. Prior to January 1, 2024, these complex rules included a verification of assets, commonly referred to as an asset test, and a variety of income deductions and exemptions. With regard to assets, the rules limited the amount of countable assets an applicant could have to $2,000 per individual and $3,000 per couple. An additional $150 in assets was allowable for each additional household member. Figure 4 summarizes selected countable and noncountable assets under the old rules. (More detail on these rules can be found in Appendix A of the Department of Health Care Services’ [DHCS’] 2020 report on Medi‑Cal asset limits.) In many cases, the rules were fairly straightforward. For example, the value of a primary residence and primary vehicle generally were not counted as assets. In some other cases, however, the rules could be complex. For example, funds dedicated for burial costs or burial plots, vaults, and crypts were exempt so long as they were secured using an irrevocable contract. If, on the other hand, the fund or space was secured using a revocable contact, only the first $1,500 of the contract was exempt.

Figure 4

Treatment of Selected Assets Under Medi‑Cal’s Prior Asset Test Rules

Prior to January 1, 2024

|

Asset Type |

Countable |

Non‑Countable |

Notes |

|

Primary Residence |

✔ |

Proceeds from the sale of a primary residence were exempt so long as the assets were used to purchase another home within six months of the sale. |

|

|

Other real estate assets |

✔ |

Up to $6,000 could have been exempt if the property produced an income of 6 percent of the property’s market value. |

|

|

Primary vehicle |

✔ |

||

|

Additional vehicles |

✔ |

Net market value of additional motor vehicles was counted. |

|

|

Recreational vehicles |

✔ |

Included recreational motor vehicles, boats, campers, and trailers. |

|

|

Annuities, retirement accounts, and pensions |

✔ |

Generally were not counted so long as payments of principal and interest were being received. (Payments count as income for eligibility determination purposes.) For annuities, the cash surrender value was counted if payments were deferred at any time. |

|

|

Life insurance |

✔ |

✔ |

Term life insurance policies were exempt. Face value for other types of life insurance policies, either on life of individual or family member, was exempt, if value was $1,500 or less. Otherwise, cash surrender value was counted. |

|

College savings plans |

✔ |

529 and 529A savings plans were exempt. |

|

|

Household items |

✔ |

||

|

Personal effects |

✔ |

✔ |

Clothing was exempt. Wedding rings, engagement rings, and heirlooms exempt. Jewelry under a market value of $100 was exempt. |

|

Assets used in a business |

✔ |

||

|

Assets being sold |

✔ |

Assets were not counted if applicant showed they were making a “bona fide effort to sell.” |

2021‑22 Budget Package Phased Out Asset Test. The 2021‑22 budget package included trailer bill legislation that phased out the asset test for seniors and persons with disabilities. Specifically, between July 1, 2022, and December 31, 2023, the asset limits were increased to $130,000 for individuals and $195,000 for couples (with an additional $65,000 allowable for each additional household member), and were fully eliminated effective January 1, 2024. With regard to income, seniors and persons with disabilities still must have countable income below 138 percent of the FPL—$20,783 for an individual in 2025. In general, seniors and persons with disabilities with income over this threshold still can be eligible for Medi‑Cal but must pay a share of cost. Based on our review of the legislative history, the elimination of the asset test was meant to remove a barrier to enrollment, encourage continuity of coverage, and make eligibility determinations between MAGI and non‑MAGI populations more equitable, among other goals.

Other Policy Changes

Elimination of a Medi‑Cal Share of Cost for Seniors Up to 138 Percent of FPL. Prior to December 2020, seniors and persons with disabilities whose incomes were between roughly 122 percent and 138 percent of the FPL had to pay a share of cost in order to receive Medi‑Cal coverage. The 2019‑20 budget package eliminated this share of cost for seniors and persons with disabilities up to 138 percent of FPL, consistent with the eligibility rules for children and adults through age 64.

Expansion of Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to Older Adults Regardless of Immigration Status. Historically, federal law has allowed for individuals with unsatisfactory immigration status to receive a restricted set of services, generally pregnancy and emergency services. Beginning in the mid‑2010s, the state began to offer full‑scope (comprehensive) services to all individuals regardless of immigration status. (The state General Fund fully incurs the costs of services provided beyond the partially federally funded restricted‑scope services.) These expansions occurred incrementally, with an expansion to those age 50 and over effective July 1, 2022.

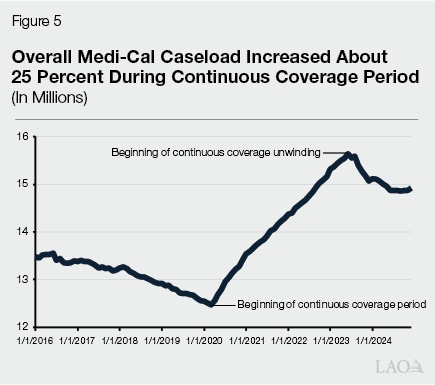

Continuous Coverage Period and Unwinding. In 2020, as a COVID‑19‑related action, Congress approved a temporary increase in federal funding for most Medicaid costs. To be eligible for this increased funding, states were required to comply with several requirements on top of standard Medicaid rules, the most important being the “continuous coverage requirement.” This requirement prohibited states from terminating eligibility for existing beneficiaries except in limited circumstances. Largely as a result of these policies, Medi‑Cal caseload increased by over 3 million enrollees (25 percent) between March 2020 and June 2023, as shown in Figure 5. Counties resumed eligibility processing in April 2023, which resulted in overall Medi‑Cal caseload beginning to decline starting in July 2023. During this continuous coverage unwinding period, the state implemented certain flexibilities meant to limit disruption of eligibility redeterminations on enrollees and simplify and reduce eligibility processing workload for counties. Some of these flexibilities helped seniors stay enrolled in Medi‑Cal—for example, one policy allowed counties to more easily renew eligibility for individuals who derive income from stable sources, such as social security and pensions.

Recent Trends in the Senior Caseload

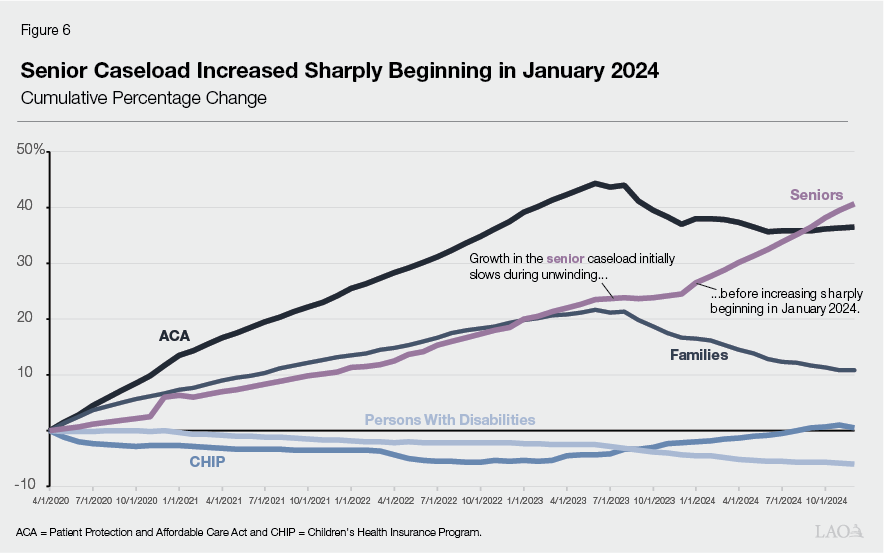

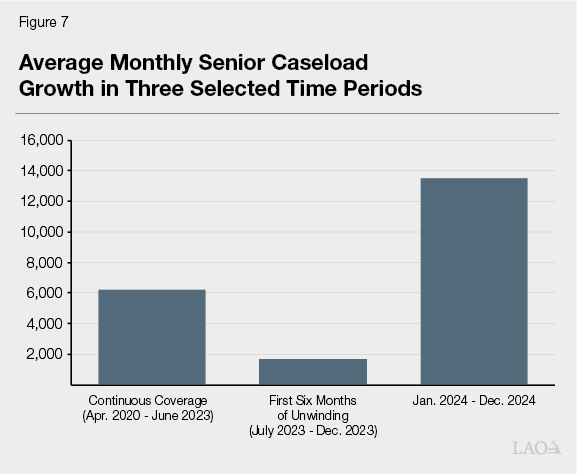

Senior Caseload Began to Increase More Sharply in January 2024. Figure 6 shows the cumulative percentage change for each category of Medi‑Cal enrollees from April 2020 (when the continuous coverage period began) through December 2024 (a year and a half after the beginning of the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement). As the figure shows, growth in the senior caseload was largely consistent with the families category until the start of the continuous coverage unwinding period. Specifically, both categories had grown by just over 20 percent by June 2023. Thereafter, the families caseload began to decrease in response to counties resuming eligibility redeterminations while the senior caseload continued to grow, albeit more slowly than during the continuous coverage period. Starting in January 2024, senior caseload began to increase sharply. Figure 7, compares average monthly growth in the senior caseload in these three time periods. Based on data available on the California Health and Human Services Agency (CalHHS) Open Data Portal, the increases have continued through at least December 2024 (the last month of data available as of publication of this report).

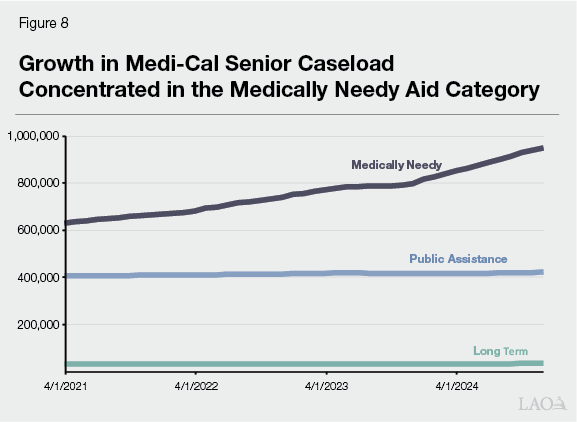

Increases Concentrated Within Single Program in Medi‑Cal. Figure 8 shows caseload in the three senior aid categories from April 2021 through December 2024. Senior caseload grew by about 320,000 individuals over the period, with growth occurring almost exclusively in the Medically Needy category. More specifically, the growth has been almost exclusively in the “1H” aid code, which corresponds to the ABD FPL program. ABD FPL program enrollees have countable income under 138 percent of the FPL, are not enrolled in SSI, and do not have a share of cost.

What is Causing the Growth in the Senior Caseload?

In this section, we estimate the extent to which four possible explanations—each related to a policy change—are causing increases in the senior caseload, while enrollment in the other caseload categories is declining or has stabilized following the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement These possible explanations include: (1) the elimination of a Medi‑Cal share of cost for seniors up to 138 percent of FPL; (2) enrollment growth in the full‑scope expansion of Medi‑Cal to older adults regardless of immigrations status (hereafter “older adult expansion”); (3) the asset test elimination; and (4) the effects of continuous coverage, the unwinding, and unwinding flexibilities.

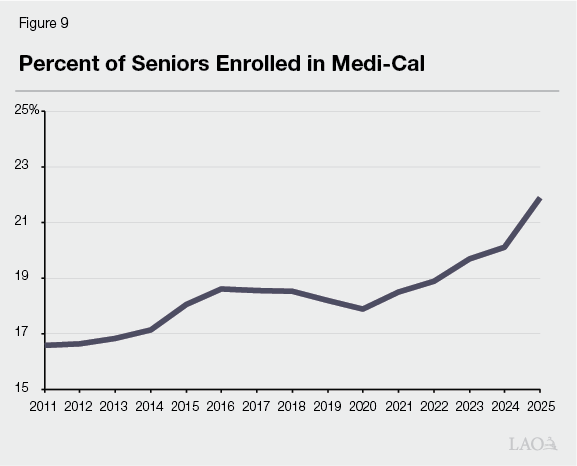

We Estimate That Senior Caseload Is Currently About 225,000 Higher Than Expected Under a Pre‑Pandemic Law Baseline. Figure 9 shows seniors enrolled in Medi‑Cal as a percent of the total population over age 65. As shown in the figure, between 2015 and 2019, the share of seniors statewide who were enrolled in Medi‑Cal ranged between about 18 percent and 18.5 percent. We estimate that there were 6.5 million individuals age 65 and over as of January 1, 2025 in California. If 18.5 percent of these individuals were enrolled in Medi‑Cal, we estimate that the senior caseload would have been 1.2 million. This estimate reflects the number of individuals that would have been enrolled in Medi‑Cal based on laws and policies in place before the pandemic (meaning without the impacts of continuous coverage, unwinding flexibilities, elimination of a share of cost for certain seniors, asset test elimination, or the older adult expansion). (While possible that additional seniors falling into poverty could have increased this 18.5 percent threshold on the natural, the lack of growth in Medi‑Cal enrollment for seniors receiving SSI benefits and increasing real per capita social security income—a key income source for seniors—leads us to think this is unlikely to contribute significantly to increases in the senior caseload.) The 1.2 million estimate compares to actual enrollment on January 1, 2025 that we estimate to be 1.4 million—a difference of about 225,000 seniors. (By applying a historical percentage of seniors already enrolled in Medi‑Cal to our estimate of the January 1, 2025 population aged 65 and over, we are already accounting for the extent to which the natural growth in the state’s overall senior population has contributed to the senior caseload increase.) This means that to explain what is driving recent increases in the senior caseload, we need to account for about 225,000 seniors in excess of this pre‑pandemic policy baseline (hereafter, “senior growth due to policy changes”).

Estimate a Total of 165,000 of Senior Caseload Growth Is Due to Eligibility Expansions. In order to determine the extent to which particular policy changes have been driving senior growth, we conducted an analysis to first determine the total increases that are being driven by eligibility expansions as opposed to the effects of continuous coverage, the unwinding, and unwinding flexibilities. In the paragraphs that follow, we provide our analysis that results in our estimate of at least 165,000 seniors being added due to eligibility expansions since 2020. (As a consequence of this estimate, it follows naturally that we estimate up to 60,000 seniors being added due to the effects of continuous coverage, the unwinding, and unwinding flexibilities, for a total increase of 225,000 seniors due to policy changes.) Having the estimate for the total senior caseload added by eligibility expansions allows us to estimate the caseload impact of the asset test elimination—an impact that is very challenging to estimate on its own without consideration of the impact of all the other policy changes affecting the senior caseload being implemented at the same time.

About 30,000 of Increase Due to Elimination of Medi‑Cal Share of Cost for Seniors Up to 138 Percent FPL Beginning in December 2020. As shown earlier in Figure 6, there was a large increase in the senior caseload in December 2020 that coincided with the elimination of share‑of‑cost Medi‑Cal for seniors and persons with disabilities with incomes between 122 percent and 138 percent of the FPL. Individuals who are enrolled in share‑of‑cost Medi‑Cal, but who have not met their share of cost in a given month, are not reflected in the caseload data. By eliminating the share‑of‑cost requirement for these individuals, we estimate that this expansion brought around 30,000 new Medi‑Cal members into the program in a single month.

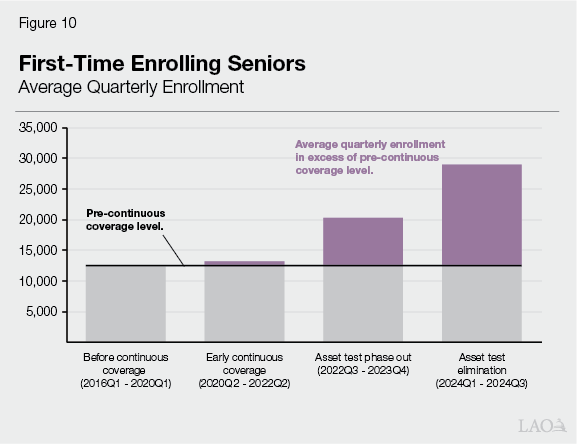

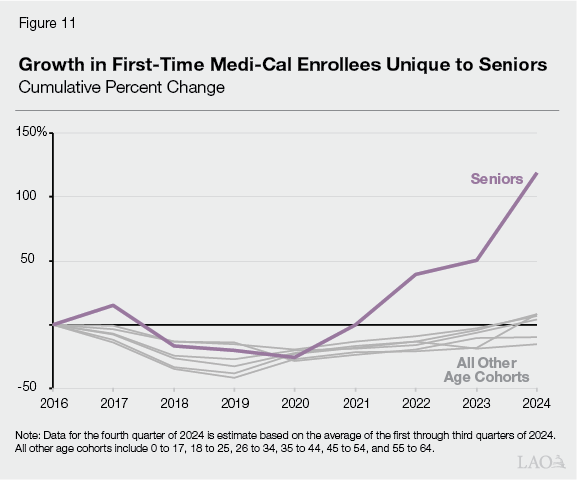

About 115,000 of Senior Growth Due to Policy Changes Are First‑Time Medi‑Cal Enrollees as a Result of Eligibility Expansions Since the Second Half of 2022. Figure 10 shows the average number of Medi‑Cal enrollees over 65 who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal for the first time in their lives in four selected time periods—before the continuous coverage period, during continuous coverage but before the asset test phase out, the asset test phase‑out period, and finally after elimination of the asset test. (The data in the figure are from the CalHHS Open Data Portal.) As shown in the figure, the quarterly average number of seniors enrolling in Medi‑Cal for the first time during the first 27 months of continuous coverage was virtually identical as it was before the pandemic. During the 18 months in which the asset limit was increased, but not eliminated, first‑time‑enrolling seniors in Medi‑Cal increased by about 60 percent. Once the asset test was fully eliminated, first‑time‑enrolling seniors were more than twice the level as prior to the policy change. As shown in Figure 11, this growth in first‑time‑enrolling Medi‑Cal enrollees is unique to seniors. From the third quarter of 2022 through the fourth quarter of 2024, we estimate that about 115,000 first‑time‑enrolling seniors enrolled in Medi‑Cal over the historical average new enrollment. Importantly, these increases in individuals enrolling in Medi‑Cal for the first time are definitionally not the result of continuous coverage unwinding flexibilities because the flexibilities only helped those already enrolled in Medi‑Cal stay in the program. Rather, this increase in first‑time‑enrolling seniors would be due to eligibility expansions.

Additional 20,000 Growth in Recent Months Due to Eligibility Expansions. As shown earlier in Figure 7, during the continuous coverage period, the average monthly increase in the senior caseload was about 6,200. This was during a time in which counties were not conducting any eligibility redeterminations. Even with federal flexibilities, we would not expect average monthly growth in the senior caseload during the unwinding period to exceed this 6,200 figure. Yet, even after removing from the caseload the 115,000 first‑time‑enrolling Medi‑Cal enrollees that are due to eligibility changes, we are left with average monthly growth of about 8,000 during 2024. We therefore assume that at least another 20,000 of the increase in senior caseload is due to eligibly expansions. (This estimate equals the difference between 8,000 and 6,200 multiplied by 12 months.) While not first‑time Medi‑Cal members, we assume that these individuals would have lost coverage absent changes like the asset test elimination. Combined with the 30,000 increase in seniors due to the elimination of a Medi‑Cal share of cost for certain seniors and 115,000 first‑time‑enrolling seniors in Medi‑Cal, we arrive at a total of at least 165,000 seniors who we estimate are in the program due to eligibility changes.

Estimate About Two‑Thirds of Senior Growth Due to Eligibility Expansions Is From Asset Test Elimination. As discussed above, the elimination of a Medi‑Cal share of cost for certain seniors provides about 30,000 of the 165,000 estimated senior growth due to eligibility expansions, leaving 135,000 of the growth to allocate between two eligibility expansions: (1) the older adult expansion and (2) the asset test elimination. In our analysis below, we estimate that the older adult expansion has resulted in an increase of 23,000 seniors, thereby leaving the remaining balance of 112,000 to be due to the asset test elimination.

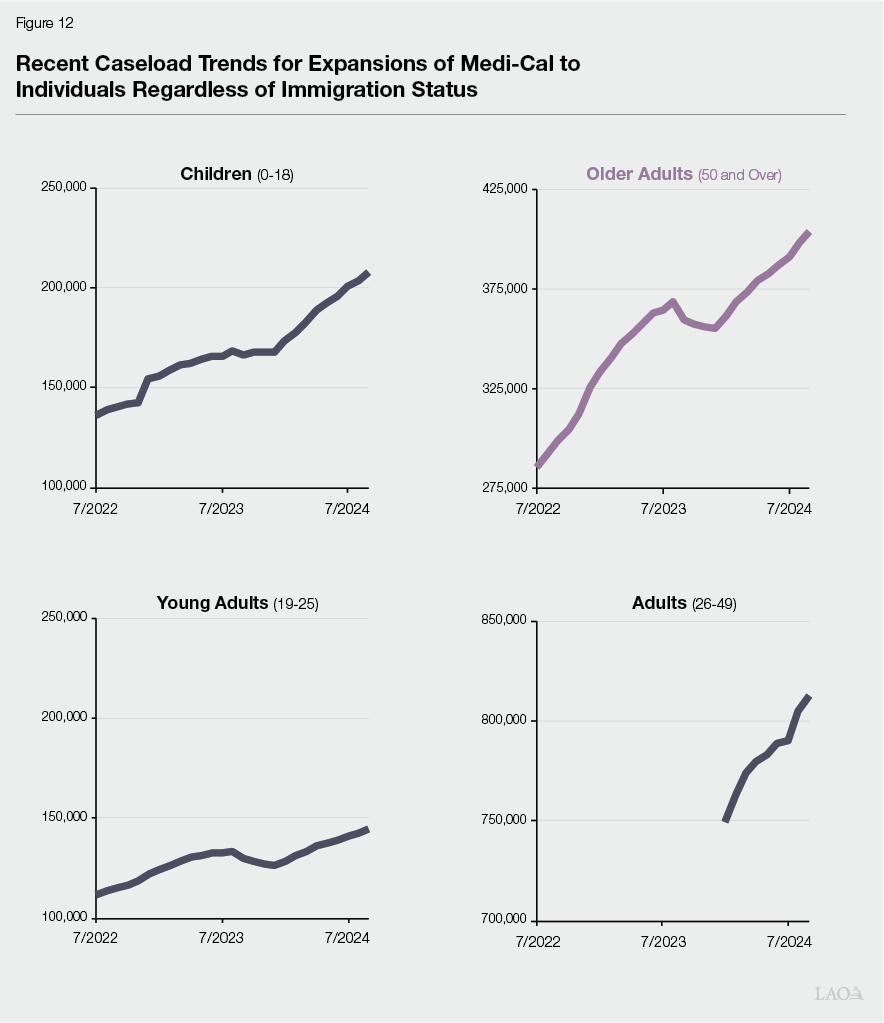

About 23,000 of Increase in Seniors Due to Eligibility Expansions Appears to Be Due to Older Adult Expansion. Figure 12 shows recent trends in the caseload for the four expansions of full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to individuals regardless of immigration status. From July 2022 through September 2024, the caseload in the expansion to individuals age 50 and older—a group that is notably not limited to those age 65 and over—increased by about 120,000 individuals. Assuming recent trends continued, by December 2024 we estimate the increase was about 135,000. Based on data on the restricted scope population prior to the expansions to adults and older adults, 17 percent of the individuals in the older adult expansion were aged 65 and older in 2021‑22. (See Figure 1 of our May 2021 publication, Estimated Cost of Expanding Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to All Otherwise‑Eligible Californians Regardless of Immigration Status.) This translates to about 23,000 seniors, or less than 15 percent, of the at least 165,000 additional seniors due to eligibility expansions.

At Least 112,000 of Senior Increase Appears to Be Due to Asset Test Elimination. After subtracting the 23,000 new seniors in Medi‑Cal we estimate are due to the older adult expansion, and the 30,000 that were shifted into Medi‑Cal due to the elimination of share of cost up to 138 percent of the FPL, at least 112,000 additional seniors due to eligibility changes remain. Presumably, these new Medi‑Cal seniors are the result of the asset test elimination, the only other major eligibility change affecting seniors since the start of the pandemic. This estimated caseload impact of the asset test elimination is at least three times the caseload impact that was estimated at the time the policy change was adopted (37,000).

Net Effects of Continuous Coverage, Unwinding, and Unwinding Flexibilities Account for Up to Remaining 60,000 of Increase in Senior Caseload. Subtracting the at least 165,000 increase in the senior caseload due to eligibility changes from the 225,000 total seniors due to policy changes leaves up to 60,000 seniors. This figure is the net of the increase in the senior caseload due to the continuous coverage period and flexibilities, less disenrollments due to the continuous coverage unwinding. While this estimate is modest, senior caseload was growing slowly before the continuous coverage period, meaning that the incremental effect of continuous coverage, the unwinding, and flexibilities was not as significant for seniors as it was for families and the ACA optional expansion population, which were declining prior to continuous coverage.

Summary of Factors Driving Growth in Senior Caseload. Figure 13 summarizes our estimates of the policy changes causing growth in the senior caseload. As shown in the figure, we estimate that the majority (165,000) of the 225,000 seniors in excess of a pre‑pandemic law and policy baseline are due to eligibility changes. Most of this 165,000 estimate is due to the asset test elimination. The remaining 60,000 seniors are assumed to be due to the effects of continuous coverage, the unwinding, and remaining enrollment flexibilities.

Figure 13

Estimated Causes of Increased Senior Caseload in

Medi‑Cal Due to Policy Changes

LAO Estimates, Caseload as of January 2025

|

Additional seniors due to eligibility changes |

165,000 |

|

(Due to elimination of share of cost for seniors up to 138 percent FPL) |

(30,000) |

|

(Due to older adult expansion) |

(23,000) |

|

(Due to asset test elimination) |

(112,000) |

|

Additional seniors due to continuous coverage and unwinding flexibilities |

60,000 |

|

Seniors in Excess of Pre‑Pandemic Law and Policy Baseline |

225,000 |

|

FPL = federal poverty level. |

|

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Considerations for the State Budget

Asset Test Elimination Appears to Cost Nearly $500 Million General Fund More Than Originally Estimated. We assume that the average caseload increase due to the asset test elimination across 2024‑25 equals the caseload effect of at least 112,000 enrollees that we estimate as of January 1, 2025 (the midpoint of the fiscal year). Multiplying this figure by average per‑enrollee costs for the Medically Needy aid category ($12,533) produces total costs of $1.4 billion for the asset test elimination. (DHCS’ original caseload estimate included a small number of individuals who would enroll in the Long‑Term category; however, because essentially all of the growth we have observed has been in the Medically Needy aid category, we only apply the per‑enrollee costs for that category for simplification purposes.) Applying a 50 percent nonfederal share as a rough rule of thumb results in General Fund costs of about $700 million in 2024‑25. If the caseload effect of the asset test elimination instead averaged 37,000 across 2024‑25, as estimated at the time of enactment of the asset test phase out, costs would have been about $460 million ($230 million General Fund). Thus, we estimate the asset test elimination results in nearly $500 million more in General Fund costs in 2024‑25 than was previously assumed to be the case.

Asset Test Elimination a Good Example of Inherent Challenges in Projecting Costs for Some Medi‑Cal Expansions. Our current estimates of the caseload and fiscal impacts of the asset test elimination raise questions about the original estimates. In general, it seems these original estimates accounted mainly for individuals who had applied for Medi‑Cal and were initially rejected due to excess assets. The estimates did not seem to account for individuals who would have been eligible for Medi‑Cal but for the asset test rules and who had never applied, a group which appears to be significant. The asset test elimination is a good example of the challenges inherent in producing fiscal estimates for proposals to extend state programs to populations that are outside of their existing reach. The asset test elimination is not alone in this regard—the expansions of full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to individuals regardless of immigration status are also costing more than originally estimated due to a combination of higher caseload and per‑enrollee costs. Upcoming budget hearings present a good opportunity for the Legislature to conduct oversight over the impacts of these and other recent expansions.

Extent to Which Senior Caseload Continues to Grow Is an Issue to Watch. As mentioned earlier, sharp increases in the senior caseload have continued through December 2024, the last month for which we have caseload data. The duration and extent of these increases will be key in eventually understanding the full fiscal and programmatic effects of the asset test elimination, the older adult expansion, and other recent eligibility changes affecting seniors. Prior eligibility expansions suggest that it can be some time before the full caseload effects of an expansion are realized, suggesting that it could be another year or more before the senior caseload stabilizes. Additionally, we have begun to see sharp increases in the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) caseload in recent months, suggesting that senior caseload growth in Medi‑Cal may have fiscal implications for the IHSS program as well. Continued monitoring of data on new enrollees in Medi‑Cal likely will be key, as the planned expiration of continuous coverage flexibilities likely will result in offsetting disenrollments in the senior caseload.

Asset Test Elimination a Powerful Tool for Helping Seniors Access Care. In watching the extent to which the senior caseload continues to grow, the Legislature may wish to keep in mind the policy benefits deriving from the elimination of the asset test. If our estimates are reflective of the causes of recent increases in the senior caseload, it seems that a significant share of California seniors living in or near poverty were eligible for Medi‑Cal but for the state’s historical restrictive limitation on assets. It also seems likely to us that a significant number of seniors who were eligible for Medi‑Cal under prior law may not have enrolled due to the complex asset rules. For example, a single individual with $20,000 in a retirement account may have chosen not to apply for Medi‑Cal upon hearing that they could only have $2,000 in assets, despite the retirement funds not being counted as assets under the rules. (The income derived from the retirement account would have been considered income.) It appears that the asset test elimination is proving to be a powerful tool for seniors in or near poverty to access health care.

Additional Issues for Legislative Oversight

The caseload developments covered in this report raise a number of issues that we think merit legislative oversight.

- Enrollee Educational Efforts. With so many seniors enrolling in Medi‑Cal for the first time, educational efforts specifically aimed at seniors could be worth considering. For example, in 2017, the scope of the state’s estate recovery policy was narrowed considerably. Generally speaking, only those deceased members whose estates are subject to probate and who received specified nursing facility or home‑ and community‑based care services are subject to recovery. Despite this narrowed scope, with so many seniors enrolling in Medi‑Cal for the first time, should the department consider any educational communications to help enrollees understand the estate recovery rules?

- Access to Services. As of December 2024, the senior caseload in Medi‑Cal stands at 1.4 million, about 40 percent higher than at the start of the continuous coverage period. Given the particular health care needs of seniors, should the state consider any actions to ensure sufficient access to services for this population?

- Potential Cost Pressures in Long‑Term Care. As shown earlier in Figure 8, the increases in senior caseload have been concentrated in the Medically Needy aid category and have not resulted in corresponding increases in the relatively costly long‑term care aid category, which has been largely flat since 2021. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration about the potential for additional seniors in Medi‑Cal to eventually shift to the long‑term care aid category, which would substantially increase state costs. Should the state consider additional actions to facilitate more transitions to less costly home‑ and community‑based services in order to help prevent this cost growth?