Nick Schroeder

June 27, 2025

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 9

(Professional Engineers)

The administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 9 (Professional Engineers) on June 23, 2025. Unit 9 consists of professional engineers who design and oversee the construction and maintenance of roads, bridges, buildings, dams, and other infrastructure throughout the state. Unit 9’s current members are represented by the Professional Engineers in California Government (PECG). The current memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the state and PECG is scheduled to expire June 30, 2025. Our analysis of the current MOU and other labor agreements proposed in the past are available on our State Workforce webpages. If ratified by the Legislature and PECG members, the proposed agreement would be the successor MOU to the current MOU. In the event that the proposed agreement is not ratified before June 30, 2025, the provisions of the current MOU generally would remain in effect as is required under the Ralph C. Dills Act. This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. The administration has posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website the agreement (including a new side letter related to the state’s hybrid work policy), a summary of the agreement, and a summary of the administration’s estimates of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effects.

Background

In this section, we provide background on key elements of collective bargaining for Unit 9 that are relevant to the proposed agreement.

Unit 9 in Context of State Workforce

Fourth Largest Bargaining Unit. Unit 9 is the fourth largest of the state’s 21 bargaining units. As of March 2025, rank-and-file and excluded employees associated with Unit 9 totaled more than 17,600 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, accounting for about 7 percent of the state’s total workforce (about 256,000 FTE). As we discuss in greater detail below, the number of Unit 9 positions as grown significantly over the past decade. Unit 9 and affiliated excluded employees account for about 2 percent of the state’s General Fund salary and salary-driven benefit costs. Most Unit 9 employees work for departments that are funded from non-General Fund sources.

Furloughs

Long History of Using Furloughs to Address State Budget Problems. Furloughs, referred to as Personal Leave Program (PLP) when established through the state’s collective bargaining process, are the most common tool adopted by the state to reduce state employee compensation costs in times of budget problems. Furloughs have been used in nine fiscal years since 1992 (1992-93, 1993-94, 2003-04, 2008-09 through 2012-13, and 2020-21). Typically, a furlough for state employees reduces state employee pay by 4.62 percent in exchange for one day (eight hours) off per month without affecting other elements of compensation (for example, pension and health benefits). In the past, the state has (1) imposed furloughs and negotiated PLP at the bargaining table, (2) established furloughs as mandatory days when employees do not work (state offices would be closed one, two, or three “Furlough Fridays” each month), and (3) allowed employees to have “self-directed” furlough days where employees have discretion to use furlough days as they would vacation or other leave benefits. During the most recent period of furloughs in 2020-21, the state negotiated agreements with all 21 bargaining units to reduce employee compensation costs through PLP 2020 in anticipation of a budget problem in 2020-21 that did not materialize. The pay reduction and number of leave hours received during PLP 2020 varied by bargaining unit, depending on the specific terms of each agreement. Subsequent labor agreements ended PLP 2020. As of December 2024, Unit 9 members have 474,357 unused furlough or PLP leave hours in their leave balances.

Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB)

Rising Cost. OPEB in state employee compensation consists of retiree health benefits. The state has provided some form of health benefits to retired state employees since 1961. During most of this time, the state has paid for these benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis after an employee is retired and receiving the benefit. Since the 1990s, the costs for this benefit have been among the fastest growing costs in the state budget. Between 2000-01 and 2024-25, the state’s inflation-adjusted General Fund pay-as-you-go cost towards these benefits increased by more than 250 percent to $2.8 billion. The largest factors driving these cost increases have been (1) the rapid growth in health premiums and (2) the growing number of people receiving the benefit as more employees retire and people live longer in retirement.

Large Unfunded Liabilities. Because the state had not set aside funds to prefund retiree health benefits for much of the benefit’s existence, a large and growing unfunded liability exists. In the most recent actuarial valuation (as of June 30, 2023) the state’s unfunded liability associated with this benefit for all state employees is estimated to be $85.2 billion.

Progress Towards Prefunding. In 2015-16, the state adopted a policy to establish through the collective bargaining process a prefunding arrangement whereby the state and current employees each pay one-half of the normal cost of the benefit (refer to our 2015 analysis, The 2015-16 Budget: Health Benefits for Retired State Employees for more information). (Under the policy, the state continues to make pay-as-you-go payments for benefits received by retirees.) The money contributed by the state and employees to prefund the benefit is put in a trust fund. Projections at the time indicated that the benefit would be fully funded by 2046. Under the plan, the assets of the trust fund cannot be used to pay for the benefit until 2046 or whenever the benefit is fully funded, whichever comes first. The state and Unit 9 agreed to this prefunding arrangement in 2015 with the fund expected to be fully funded for Unit 9 within 30 years. Today, the state and employees represented by Unit 9 contribute 2 percent of pay to prefund the benefit for Unit 9 members. As of June 30, 2023, the state and Unit 9 have set aside $370.8 million to prefund the benefit and the unfunded liability associated with Unit 9 is $3.2 billion. The most recent actuarial valuation of Unit 9 retiree health benefits (as of June 30, 2023) estimates that the Unit 9 funding plan is on track to fully fund Unit 9 retiree health benefits by 2048.

Telework

Stipend. Since October 2021, Unit 9 members have been eligible to receive a monthly telework stipend. Employees who are identified as being “remote centered” are eligible to receive $50 per month. Employees who are identified as “office centered” are eligible to receive $25 per month. Under the telework stipend program, the MOU specifies that “no reimbursement claims will be authorized for utilities, phone, cable/internet, or other telework incurred costs.”

Executive Order N-22-25. Under current state policy, state departments that allow state employees to work a hybrid schedule (meaning a portion of the work week in office and a portion of the work week from a remote location) must have a telework policy with a default minimum of two in-person days per work week. On March 3, 2025, Governor Newsom issued Executive Order N-22-25. The executive order requires all agencies and departments under the Governor’s authority that provide telework as an option for employees to implement a telework policy with a default minimum of four in-person days per work week effective July 1, 2025.

Vacation and Annual Leave Caps

Leave Caps. Under state law, vacation or annual leave is considered a form of wages that is vested when earned. As such, employers cannot adopt a “use it or lose it” policy for earned employee vacation and annual leave whereby unused vacation or annual leave above a certain level is forfeited at the end of the year. State law allows employers to adopt a leave cap whereby employees do not accrue new vacation leave once their leave balance has reached the cap.

640-Hour Cap. The state caps the amount of vacation or annual leave that most state workers—including Unit 9—may accumulate at 640 hours (80 days). Under state policy, employees continue to accrue leave even if their leave balances exceed the cap. The state’s leave balance caps are the state’s main tool to manage state employees’ leave balances. When an employee approaches or exceeds the cap, managers are supposed to work with the employee to develop a plan to ensure that the employee is able to take time off to keep their leave balance below the applicable cap.

Proposed Agreement

Term. The agreement would be in effect from July 1, 2025 through June 30, 2028. This means that the agreement would be in effect for three fiscal years: 2025-26, 2026-27, and 2027-28.

Pay Increases. As specified below, the agreement would provide all Unit 9 members pay increases on July 1, 2025 and on July 1, 2027.

2025-26: 3 Percent General Salary Increase (GSI). Effective July 1, 2025, the agreement would provide all state employees represented by Unit 9 a 3 percent pay increase. As a GSI, the pay increase adjusts all steps of all salary ranges of all job classifications represented by Unit 9.

2026-27: Special Salary Adjustments (SSAs) to Top (4.5 Percent) and Bottom Steps (2 Percent). Effective July 1, 2027, the agreement would provide SSAs that adjust the top and bottom steps of the salary ranges for all Unit 9 classifications. Specifically, the top steps would increase 4.5 percent and the bottom steps would increase 2 percent. This would have the effect of a 4.5 percent pay increase for any employee at the top step of the salary range and a 2 percent pay increase for all other employees.

PLP 2025. The agreement would establish PLP 2025 for Unit 9 members in 2025-26 and 2026-27. Under the agreement, PLP 2025 would (1) reduce employee pay by 3 percent (effectively holding employee take-home pay flat after accounting for the GSI) and (2) provide employees five hours of PLP 2025 leave each month. The agreement specifies that employees should be given maximum discretion to use PLP 2025 leave and that all leave should be used prior to separation from state service. In the event that employees have unused PLP 2025 leave in their leave banks upon separation, the agreement specifies that the employees’ unused leave would be cashed out upon separation at their final salary level. The agreement specifies that PLP 2025 would not affect employees’ retirement, health, or other benefits.

Suspend Employer and Employee Contributions to Prefund Retiree Health Benefits. The proposed agreement would suspend for two years (2025-26 and 2026-27) both the employer and the employee contributions to prefund retiree health benefits. Specifically, the contributions would be suspended from July 1, 2025 through June 30, 2027.

Telework Stipend. The agreement would end the telework stipend effective June 30, 2025.

Vacation and Annual Leave Cap. The agreement would allow employees to have larger leave balances before managers are expected to develop plans with employees to use their accrued leave above 640 hours through 2028. The proposed agreement specifies the vacation and annual leave cap would be 832 hours in 2026, 768 hours in 2027, 704 hours in 2027, and return to 640 hours in 2028.

Furlough Protection. The proposed agreement specifies that, while PLP 2025 is in effect (2025-26 and 2026-27), the state will not implement a furlough program or establish additional PLP days.

LAO Comments

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect

Reduced State Costs Through 2026-27. Figure 1 shows the administration’s estimated fiscal effects of the proposed agreement. As the figure shows, PLP 2025 and the suspension of OPEB prefunding would result in the state’s Unit 9 compensation costs being lower than present levels through 2026-27. These savings would help address the immediate budget problem.

Long Term, Agreement Would Increase State Costs. While the agreement would reduce annual state costs through 2026-27, it would lead to higher annual costs beginning in 2027-28. Moreover, as we discuss in greater detail below, the agreement would lead to growth in unfunded liabilities, potentially contributing to future budget problems.

Figure 1

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect of Proposed Unit 9 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|||

|

Pay Increases |

$6.0 |

$83.7 |

$6.0 |

$83.7 |

$12.5 |

$175.7 |

||

|

Personal Leave Program 2025 |

‑6.2 |

‑86.2 |

‑6.2 |

‑86.2 |

— |

— |

||

|

Eliminate Telework Stipend |

‑0.4 |

‑5.8 |

‑0.4 |

‑5.8 |

‑0.4 |

‑5.8 |

||

|

Suspend Employer OPEB Contributionsa |

‑2.2 |

‑30.2 |

‑2.2 |

‑30.2 |

— |

— |

||

|

Extend Terms of Agreement to Excluded Employeesb |

‑2.3 |

‑12.5 |

‑2.3 |

‑12.5 |

7.7 |

37.6 |

||

|

Totals |

‑$5.0 |

‑$51.1 |

‑$5.0 |

‑51.1 |

$19.8 |

$207.4 |

||

|

aState General Fund retiree health prefunding costs are paid using funds required to be expended under Proposition 2 (2014). bThis is an indirect cost that would result from the agreement being ratified. |

||||||||

|

OPEB = Other Post‑Employment Benefits. |

||||||||

Unit 9

Wages Found Lagging Statewide for One Occupation. The most recent CalHR compensation study compared the state’s compensation with that offered by other employers for three occupations: civil engineers, electrical engineers, and environmental engineers. The study found that state wages (excluding benefits) were (1) above the statewide market for civil engineers (by 2.5 percent) and environmental engineers (by 7 percent) and (2) below the statewide market for electrical engineers (by 16.6 percent).

Total Compensation Found Above Statewide Market for All Occupations. When looking at wages and benefits, CalHR found that state total compensation for all three occupations were above the statewide market (electrical engineers by 0.7 percent, civil engineers by 12.5 percent, and environmental engineers by 16.7 percent). The only instance where state total compensation was found to lag other employers was in the regional market in the San Francisco Bay Area for electrical engineers by 12 percent.

Recruitment and Retention Challenges Among Unit 9 Not Clear. The number of Unit 9 positions has grown significantly in recent years. Specifically, between 2013 and 2024, the number of Unit 9 positions grew by more than 17 percent from 10,333 positions to 12,141 positions. In light of the growth in Unit 9 positions, the factors we discuss below could indicate some combination of (1) challenges filling Unit 9 positions or (2) operational decisions by departments to keep positions vacant.

Turnover Rates Lower Than State Average. The turnover rate among Unit 9 (5.8 percent) is lower than the statewide turnover rate (7.4 percent). Turnover from Unit 9 as a result of voluntary or involuntary separations—meaning separation before retirement—is much lower than the state averages. For example, while the statewide average of voluntary separations is 3 percent, it is only 1.2 percent among Unit 9 positions. This suggests that the state is not facing challenges retaining employees in Unit 9 positions.

Vacancy Rate Above State Average. In 2019 and 2020, the vacancy rate among Unit 9 positions was below or at the statewide average vacancy rate across all civil service positions. Since 2020, the Unit 9 vacancy rate has been higher than the statewide average. As of May 2025, the Unit 9 vacancy rate was 19 percent compared with the statewide average of 17 percent. Most of the growth in Unit 9 positions occurred after 2020—coinciding with the growth in the vacancy rate. This suggests that the state is not filling the new positions. Vacancies could be due to recruitment challenges or could reflect operational decisions made by departments to hold positions vacant in order to use the funding associated with the vacant positions to pay for other things in their budget.

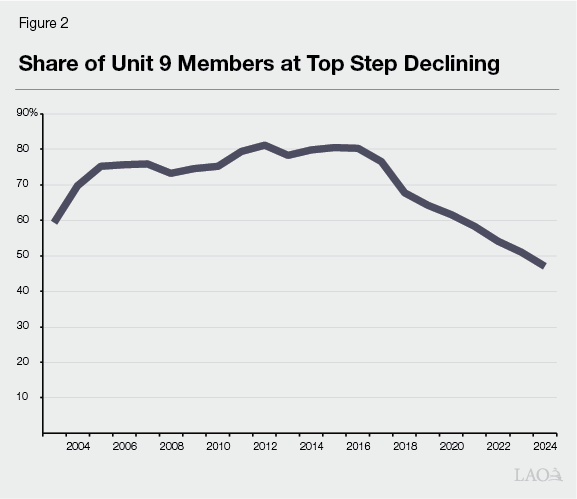

Declining Seniority Among Unit 9 Members. As Figure 2 shows, over the past decade, the share of Unit 9 members who are at the top step of their classification’s salary scale has decreased significantly from more than 80 percent in 2015 to 47 percent in 2024. This drop in the share of employees at the top step coincides with a drop in the average number of years of service during the same time period—from 14 years of service to 11 years of service. Both of these trends indicate that Unit 9 members are less senior today than they were a decade ago. This decline in seniority likely reflects a combination of (1) Unit 9 members retiring and being replaced with new state employees and (2) new positions being filled with new state employees..

Effects of PLP

Furloughs a Common, but Imperfect Tool. Although furloughs and PLP are established through different means (imposed versus bargained), the two policies functionally are the same: reduced pay in exchange for time off. As such, we generally refer to the two policies interchangeably as furloughs. As we indicated above, the state has used furloughs extensively in the past three decades in response to budget problems. Furloughs have some clear advantages including that they are administratively easy to implement; they offer immediate and predictable levels of savings; and they do not require a reduction in workforce, allowing the state to immediately “staff up” after the budget problem passes. However, there are some notable trade-offs to relying on furloughs to achieve budgetary savings. These trade-offs include effects on recruitment and growth in long-term liabilities:

Recruitment: Furloughs can make the state a less attractive employer to possible new hires by making the state’s compensation package less competitive compared with compensation offered by other employers and by demonstrating a lack of predictability in the state’s terms of employment.

Long-Term Liabilities: Furloughs result in higher leave balances and retirement unfunded liabilities. Unless employees are able to take more time off, furloughs result in larger unused leave balances. These higher leave balances, in turn, lead to higher costs to the state when employees separate from state service and the state must pay the employee for any unused leave at their final salary level. Retirement liabilities funded as a percentage of pay also grow as a result of furloughs. For example, the state pays a percentage of employees’ pay to fund pension benefits. During a furlough, the state’s contributions towards pension benefits is made as a percentage of the reduced salary. However, the benefit earned by the employee is based on their full (not reduced) salary. Accordingly, during furloughs, the state systematically underfunds its pensions—contributing to larger unfunded liabilities.

Suspension of Employer and Employee OPEB Contributions

Missed Opportunity to Improve OPEB Prefunding Arrangement. We long have been critical of the state’s retiree health prefunding strategy. We have found that establishing a benefit that fundamentally has no bearing on an employee’s salary to be funded as a percentage of pay is overly complicated and creates risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by the target date. In addition, sharing the funding cost with state employees likely strengthens any argument that the benefit is protected under the State Constitution, potentially preventing the Legislature from reducing or modifying the benefit in the future. Instead, we have argued that the state should assume the full responsibility of prefunding the benefit. While we are not at the bargaining table and do not know what issues were discussed, we feel it was a missed opportunity for the parties to not find a solution that simplified the prefunding arrangement while also helping address the current budget problem.

Proposed Agreement Makes Fully Funded Target Date Unlikely. Currently, the full normal cost to prefund Unit 9 retiree health benefits is estimated to equate to 4 percent of Unit 9 pay. Under the proposed agreement, no contributions would be made to prefund the benefit for two years. Systematically underfunding the benefit for two years makes reaching the full funding target date unlikely.

Lower Costs Today in Exchange for Higher Costs Later. Suspending both the employer and employees’ contributions to prefund OPEB for two years reduces costs today but contributes to a significant and growing unfunded liability and creates substantial risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by 2048. Further, it creates a precedent for (1) other bargaining units this year to adopt similar actions and (2) future Governors to see this action as an acceptable trade-off to address future budget problems. To the extent that this action is repeated, whether this year or in future years, the goal to fully fund the benefit will become increasingly elusive. In that case, the state could once again face rapidly growing costs in order to pay this benefit. Moreover, the structure of the funding plan allows the state to use money in the trust fund beginning in 2046, regardless of whether or not the benefit is fully funded. The benefit is on track to be fully funded after 2046. Suspending contributions will delay the full funding date further. A future Legislature and Governor could face pressure to use money from the trust fund as soon as it becomes available, especially to address a budget problem, should one exist in 2046. To the extent that money is drawn from the fund before the benefit is fully funded, the likelihood of the benefit ever becoming fully funded will further diminish. Maintaining regular and full payments to prefund the benefit is the best option to meet the policy goal of fully funding the benefit.

Vacation and Annual Leave Caps

Ineffective Tool. While the leave cap is the state’s main tool to manage state employees’ leave balances, it is ineffective. It especially is ineffective during times of furlough when employees receive additional time off. In our review of leave balances following the five years of furloughs between 2008-09 and 2012-13, we “found no evidence that the cap had an effect on containing state employee leave balances” during the period. As of December 31, 2024, more than 2,300 employees represented by Unit 9 had vacation or annual leave balances that exceeded the cap. The proposed agreement’s changes to the leave cap is an acknowledgement that PLP 2025 likely will result in higher leave balances; however, we do not consider the proposed changes as materially substantial.

Budget

Three-Party Budget Deal Assumes Savings From State Employee Compensation. The current form of the budget deal between the two houses of the Legislature and the Governor (AB 102, Gabriel) assumes that state employee compensation will be reduced in 2025-26. Control Section 3.90 specifies that “the Legislature finds that the savings will likely be needed to maintain the sound fiscal condition of the state.” The control section establishes an expectation of the Legislature that all state bargaining units will meet and confer in good faith with the administration on or before July 1, 2025 to achieve the assumed level of savings through the collective bargaining process for rank-and-file employees and through existing administrative authority for employees excluded from the collective bargaining process.

Three-Year Term Could Reduce Future Legislative Flexibility. We long have recommended that the Legislature only ratify agreements that would be in effect for one or, at most, two fiscal years The basis of this recommendation is to preserve legislative flexibility to respond to changing economic conditions. If the state’s budget condition were to improve or degrade over the next three fiscal years, it would be difficult for the Legislature to deviate from the agreement.