Angela Short

January 28, 2026

Implementing California’s Child

Welfare Prevention Services Program

- Introduction

- Background

- State’s Progress Toward Implementing FFPS Prevention Program

- Counties’ Prevention Plans

- Counties’ Implementation Challenges

- Considerations and Opportunities for Legislature

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

Executive Summary

California Working to Implement Prevention Services Program. The Legislature passed Chapter 86 of 2021 (AB 153, Committee on Budget)—creating the Family First Prevention Services (FFPS) program—to provide services to children and families to prevent the need for child welfare system involvement and foster care placement. The program allows counties to receive federal Title IV‑E dollars for eligible services—a new and expanded use of this uncapped federal funding source. In addition to federally eligible prevention services, FFPS also encourages counties to deliver a broad range of prevention activities tailored to their local populations. Alongside the state legislation, the 2021‑22 budget provided $222.4 million for block grants to counties to develop their programs and begin implementing prevention services. The block grants are available for expenditure through June 30, 2028.

Implementation Includes Many Steps and Will Take Years to Execute Fully. Implementing the prevention services program established by FFPS represents a major undertaking and reflects a broader shift within child welfare policy over time to focus more on preventing entry into foster care. Implementing FFPS entails many steps that the Department of Social Services (DSS) and counties (as well as service providers and other stakeholders) must take. At this stage of implementation, DSS and counties have completed a number of essential steps in terms of preparation and planning and currently are working to implement services (with some counties already beginning to implement some new prevention services). This report provides a comprehensive update of implementation progress to date and highlights major areas where key program guidance remains forthcoming.

Developing Sustainable Funding Plans Will Be Needed for Prevention Services Program to Meet Its Goals. While the new federally allowable use of Title IV‑E funding for prevention services is significant, there are some notable limitations of the funding—such as the types of eligible programs and criteria for participation. In addition, Title IV‑E reimbursement for services requires that counties provide $1 of local funding for every $1 of federal funding claimed. Counties’ initial capacity to provide a local funding match is unclear. Additionally, services beyond the scope of federally eligible programs will need to be funded entirely by state/local sources. Child welfare funding in California is complex, with counties receiving dedicated revenues from the state to operate their child welfare programs. These revenues are based on complex formulas that are not directly tied to current caseloads and costs. While counties should achieve foster care cost savings by implementing effective child welfare prevention services (because there should be fewer children entering foster care), achieving those savings requires up‑front investments. Given these factors, both the state and counties will need to consider how multiple funding streams—including Medi‑Cal, local, state, and other federal sources—could be used to support child welfare prevention services.

Opportunities for Legislative Input. Our review of initial implementation by DSS, counties, and other stakeholders identifies some challenges and opportunities for the state. This report offers the Legislature a number of considerations to help ensure implementation of child welfare prevention services can continue in a manner that (1) allows the state to maximize federal funding whenever possible and (2) helps promote prevention services that can benefit as many at‑risk families across the state as possible. As the state remains in the relatively early phases of implementation, now is a good time for the Legislature to weigh in.

Introduction

In recent years, California’s child welfare system has focused on prevention services as a way to try to mitigate maltreatment risks and the need for child removal and placement into foster care. The state’s efforts were bolstered by the 2018 passage of the federal Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA). The law allows states to receive federal foster care funding when providing certain prevention services to specific at‑risk families, in addition to other federal law changes impacting other areas of child welfare and foster care policy. California began implementing FFPSA in 2021‑22 and provided a one‑time $222.4 million General Fund block grant to local child welfare agencies for prevention services.

In this publication, we discuss the state’s and counties’ ongoing implementation of prevention services since 2021‑22. First, we provide background information regarding California’s child welfare system and how it is funded. Second, we describe progress at the state level in developing and overseeing the new child welfare prevention services program. Third, we describe counties’ plans for implementing child welfare prevention services at the local level, as well as some challenges they have faced. Finally, we provide some considerations and options for the Legislature moving forward to help improve the state’s prevention services program and ensure implementation proceeds in a manner that (1) allows the state to maximize federal funding whenever possible and (2) helps promote sustainable prevention services that can benefit as many at‑risk families across the state as possible.

Background

California’s Child Welfare System Serves to Protect Children and Strengthen Families. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a variety of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such as substance use disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal to help families remain together, if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care system, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to safely return to their parents, the state provides assistance to establish a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship. (For a more detailed overview of California’s child welfare system, refer to our publication California’s Child Welfare System: Addressing Disproportionalities and Disparities.)

California’s Child Welfare System Is Locally Implemented, With Requirements and Oversight From State and Federal Governments. Local child welfare agencies implement child welfare programs on behalf of the state, with oversight from the Department of Social Services (DSS) and federal government. Local agencies include county child welfare departments, county probation departments, and certain tribes. (We will refer to the various types of local child welfare agencies as “counties” throughout this publication for simplicity.) Funding for child welfare programs comes from the federal and state governments, along with local funds. The federal and state governments set standards in terms of the service components that all local child welfare agencies must implement and oversee the quality of service delivery.

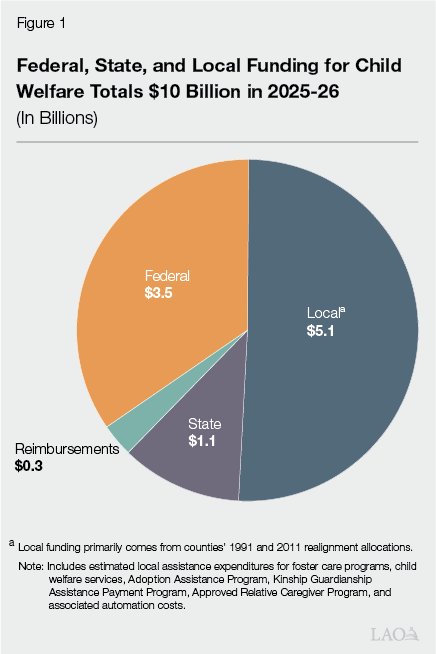

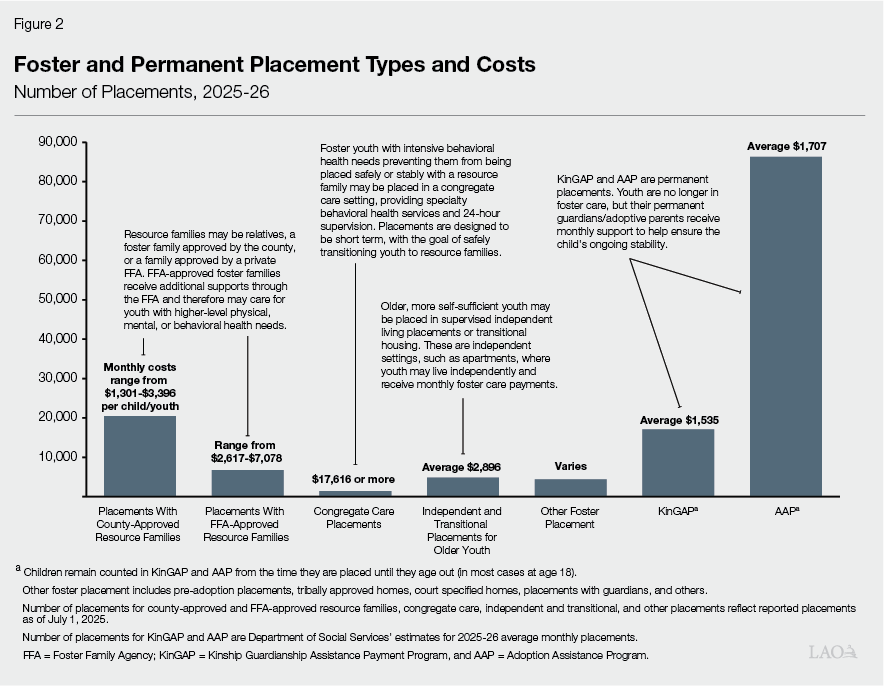

California’s Child Welfare System Is Funded by a Mix of Federal, State, and Local Funds. The state’s diverse array of child welfare programs is funded by federal, state, and local funds, as shown by Figure 1. The proportional mix of funds used to support any particular child welfare payment or service varies depending on whether a family is eligible for federal financial participation (a determination generally based on the income of the family from which a child was removed in foster care cases). Furthermore, the cost of services and supports may vary greatly based on the needs of the individual child and family (and whether the child has been placed into foster care or is able to remain safely at home). For example, in 2025‑26, the estimated average monthly assistance payment for foster care across all placement types is around $3,500, although for an individual child that payment may range from around $1,300 to nearly $18,000 or more depending on where a child is placed and the level of care needed. Figure 2 provides more information about the different out‑of‑home foster placements (that is, not those who are able to remain safely in their homes) and permanent placement types, along with monthly costs. In addition to the monthly assistance payment amount, other costs related to the child and parents’ needs may include, for example, Medi‑Cal coverage for behavioral health services. Foster care and permanent placements represent about half of the state’s General Fund spending on child welfare programs. Therefore, effective prevention efforts could help significantly reduce the state’s overall costs in this area.

Federal Funding Includes a Couple Major Uncapped and Capped Sources. When a family requires child welfare services or foster care, states may claim federal funds (that is, seek federal reimbursement) for part of the cost of providing care and services for the child and family if they meet federal eligibility requirements. State and local governments provide funding for the portion of costs not covered by federal funds, based on cost‑sharing proportions determined by the federal government. These federal funds are provided pursuant to Title IV‑E (related to foster care) and Title IV‑B (related to child welfare) of the Social Security Act.

- Title IV‑E. These funds are an uncapped federal entitlement—meaning there is no limit on how much Title IV‑E dollars states are able to claim for eligible expenditures—although eligible expenditures are relatively limited. Primarily, states may claim these funds for foster care, adoption, and guardianship assistance payments for eligible families. Eligibility for Title IV‑E federal financial participation in foster care cases generally depends on the income of the family from which a child was removed. More specifically, families must meet 1996 federal Aid to Families with Dependent Children eligibility requirements. This roughly equates to earnings of under $1,000 per month for a family of four. (In 2025‑26, an estimated 53 percent of foster care cases meet this requirement.) California must spend about $1 from nonfederal sources for every $1 of Title IV‑E funding the state receives (the federal matching rates differ across states and for different program components). In California, the nonfederal funds come primarily from counties’ 2011 realignment allocations. Realignment is explained in the box nearby. For federal fiscal year 2024, an estimated nearly $10 billion in Title IV‑E funding was provided nationally.

- Title IV‑B. On the other hand, allowable uses for Title IV‑B funds are significantly broader and can be used more generally for child and family services. However, these funds are provided to states as annual capped amounts (with the specific amounts varying from year to year based on the federal appropriation and other factors). Title IV‑B funding also includes some competitive grants that states may apply for related to child welfare research, training, and demonstration projects. States must spend at least $1 from nonfederal sources for every $3 of Title IV‑B funding the state receives. For federal fiscal year 2024, around $1.4 billion in Title IV‑B funding was provided nationally.

2011 Realignment

California’s Child Welfare Programs Were “Realigned” to Counties. Until 2011‑12, the state General Fund and counties shared significant portions of the nonfederal costs of administering child welfare programs. In 2011, the state enacted legislation and the voters adopted constitutional amendments (in 2012) known as 2011 realignment, which gave counties full nonfederal fiscal responsibility for child welfare. The legislation also dedicated a portion of the state’s sales and use tax and vehicle license fee revenues—along with a portion of the associated growth in these revenues—to counties to administer these programs (as well as some public safety, behavioral health, and adult protective services programs). In addition to dedicated 2011 realignment dollars, counties also may choose to spend other local funds (such as county general fund resources) on child welfare programs. As a result of Proposition 30 (2012), under 2011 realignment, counties either are not responsible or only partially responsible for child welfare programmatic cost increases resulting from federal, state, and judicial policy changes. Proposition 30 establishes that counties only need to implement new state policies that increase overall program costs to the extent that the state provides the funding for those policies. Counties are responsible, however, for all other increases in child welfare costs—for example, those associated with rising caseloads. Conversely, if overall child welfare costs fall, counties retain those savings.

Realignment Shifted Some Child Welfare Program Dynamics. Parameters set by realignment and Proposition 30 have resulted in some important dynamics within local‑ and state‑level child welfare program implementation:

- The state has implemented many newer child welfare program components as county options rather than mandated programs.

- California’s 58 counties make different implementation choices for child welfare programs. This approach can allow counties to make program choices that best meet the needs of their local populations, but at the state level can create challenges in tracking local program choices. Tracking how counties choose to spend their realignment dollars also presents challenges at the state level.

- Counties have incentive to achieve programmatic savings because they can retain those savings, freeing up funds for other child welfare services. However, because counties only receive realignment funds from the state to cover their costs, they also must identify other resources when costs exceed those amounts.

Other federal funding sources (all of which are capped) that California uses for foster care and broader child welfare purposes include some Temporary Assistance for Needy Families dollars and various federal grants, such as the Child Abuse Prevention Program and Chafee Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood.

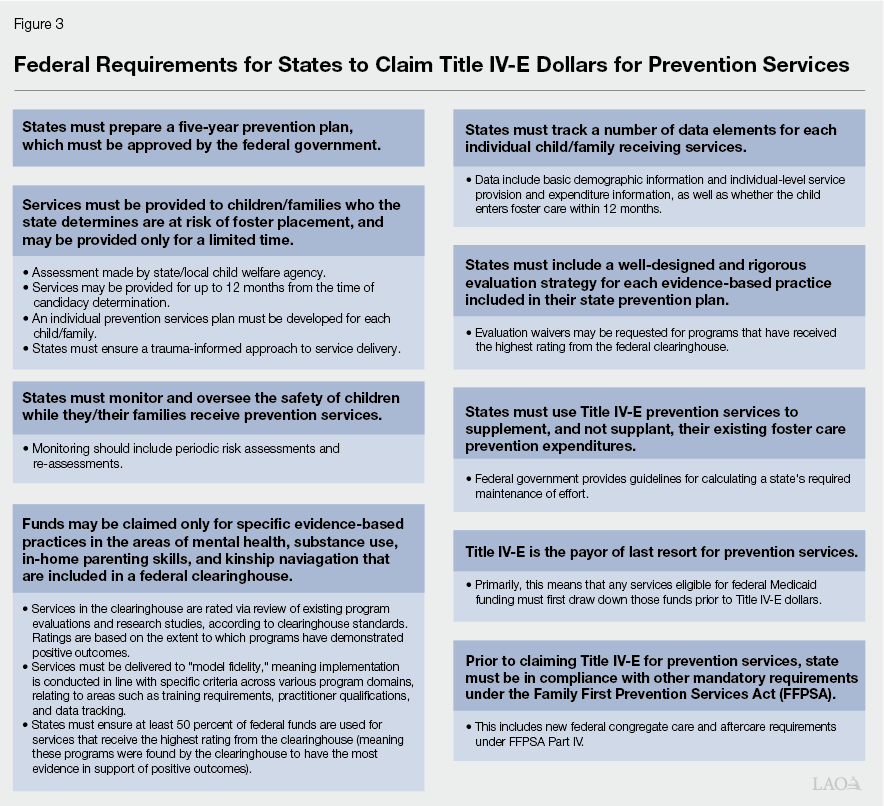

FFPSA Expanded Allowable Uses of Title IV‑E to Include Prevention Services. Passed as part of the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act, FFPSA expands allowable uses of federal Title IV‑E funds to include support for certain federally approved services to help prevent children and families from entering (or reentering) the foster care system. States are able to claim Title IV‑E funds for this new, expanded purpose within specific parameters. For example: (1) services must be provided to children/families who are “candidates” for foster care (as assessed by states/local child welfare agencies) or to pregnant/parenting youth in foster care; (2) funds may be claimed only for specific evidence‑based practices (EBPs) in the areas of mental health, substance use, in‑home parenting skills, and kinship navigation that are included in a federal clearinghouse; and (3) states must be able to track certain metrics for the individual/family receiving these services, to monitor expenditures and to demonstrate whether services help to reduce foster placements. A summary of these requirements, with some additional detail, is included in Figure 3.

Beyond expanding allowable uses of Title IV‑E funding for prevention, FFPSA requires states to make a number of changes to their foster care systems and programs, such as limiting the circumstances in which federal funding may be used to pay for congregate foster care placements. These changes must be made before states may seek Title IV‑E reimbursement for prevention services.

California Working to Implement Prevention Services Program. In response to FFPSA, California’s Legislature passed Chapter 86 of 2021 (AB 153, Committee on Budget)—creating the Family First Prevention Services (FFPS) program—to enact the federally required changes under FFPSA and to establish a new state prevention services program to take advantage of the expanded eligible uses for Title IV‑E funds and implement a broader array of prevention services. Alongside this state legislation, the 2021‑22 budget provided $222.4 million for block grants to counties to begin implementing Title IV‑E prevention services, as well as any other non‑federally eligible prevention services they choose to implement. The block grants are available for expenditure through June 30, 2028.

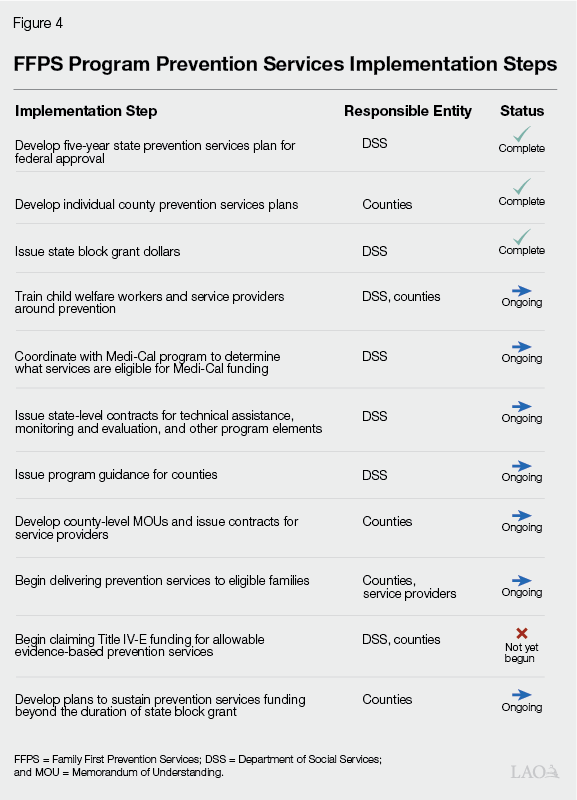

FFPS Implementation Includes Many Steps. Implementing the prevention services program established by FFPS entails many steps that DSS and counties (as well as service providers and other stakeholders) must take, as described throughout the remainder of this report. At a high level, major steps and their current status are laid out in Figure 4 and described in further detail in the following sections. At this current stage of implementation, DSS and counties have completed a number of essential steps in terms of preparation and planning. Counties currently are preparing to implement services (with some counties already beginning to implement some new prevention services).

FFPS Program Represents One Important Pillar of State’s Shift Toward Prevention Focus. The state’s prevention services program goes beyond implementing federally eligible services, with the overall aim to “improve outcomes for children and families, reduce entries into foster care, and reduce disproportionate entries into foster care” for overrepresented groups. The FFPS program marks an important milestone of shifts over time within California’s child welfare policy focus toward prevention. Simultaneously, the state is undergoing other complementary efforts to help reshape child welfare policy.

As one notable example of prevention‑related activities outside of FFPS, major efforts are underway to reform mandated reporting of child maltreatment. Mandated reporters are defined in state law as individuals in specific occupations (such as teachers, medical professionals, and law enforcement) who are required to report any known or suspected child maltreatment. Reporting maltreatment is an important part of protecting children. However, various stakeholders have raised concerns that the current mandated reporting law and practices overemphasize liability and result in trauma due to unnecessary reports to child welfare, rather than focusing on supporting families and preventing formal child welfare system involvement when not necessary for a child’s safety.

These complementary reform efforts directed at mandated reporting and other policy areas will be important to help achieve the state’s overall vision for its prevention services program.

State’s Progress Toward Implementing FFPS Prevention Program

Typically, when legislation creates a new child welfare program or directs changes to existing programs, DSS provides more detailed implementation guidance to counties, often through all‑county letters, which are distributed to local child welfare program directors and published online. Depending on the level of detail required, DSS usually provides program guidance within 6 to 12 months. For more substantial program changes, such as those required to implement FFPS, guidance may take longer to develop. As implementation of the FFPS program progresses, DSS has published, and continues to work toward developing, numerous major pieces of guidance for counties, as described throughout this section.

Five‑Year State

Prevention Services Plan

DSS Developed State Prevention Plan. As a first step toward implementing the prevention services portion of FFPS (prior to issuing internal state‑level guidance on specific program components), DSS needed to develop a state prevention plan for federal approval. According to federal requirements, state plans must detail the state’s selection of evidence‑based prevention services; plans for identifying populations at imminent risk of entry or reentry into foster care (who may be assessed as candidates); and the approach that will be used to comply with federal evaluation, model fidelity, activity and outcome tracking and reporting, and safety and risk monitoring requirements. (The concept of “model fidelity” is described in the nearby box.)

Model Fidelity

“Model fidelity” refers to how closely an implemented program adheres to the original, evidence‑based model on which it is based. A program delivered to high fidelity refers to a program that is implemented as designed in terms of factors such as planning and implementation phases, staff qualifications and training, data collection, and tracking outcomes. A program implemented in a way that deviates significantly from the model on which it is based would have low fidelity and not adhere to model fidelity requirements. Model fidelity is important in the context of evidence based practices because if programs are not implemented in the same way they are tested and modeled, they are unlikely to yield the desired results.

In developing the state plan, DSS held numerous stakeholder feedback sessions. DSS also received significant feedback from the federal government upon initial submission of the state plan. The updated plan ultimately was approved by the federal government in April 2023.

State Plan Includes Ten Well‑Supported EBPs. The federal clearinghouse rates EBPs as well‑supported, supported, promising, or not having enough evidence. See the box on the nearby for a more detailed explanation of these federal ratings. California’s state plan includes the ten EBPs in the federal clearinghouse that were rated as well‑supported at the time of plan development. These ten EBPs include four home‑visiting/parenting skills programs, two mental health programs, one substance abuse program, and three programs that are designed to address more than one of those areas. The EBPs are:

- Nurse‑Family Partnership: Home‑visiting program for low‑income, first‑time mothers. Visiting nurses support mothers with parenting skills, preventative health practices, and individualized goal setting and planning.

- Healthy Families America: Home‑visiting program delivered by community‑based organizations for new families with children at risk for maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences, typically offered for three years. Overall program goals are to strengthen nurturing parent‑child relationships, promote healthy child development, and reduce risk factors.

- Parents as Teachers: Home‑visiting parent education program wherein trained parent educators teach new parents skills intended to promote positive child development and prevent child maltreatment. Sessions also may be delivered in schools, child care centers, or other community spaces.

- Parent‑Child Interaction Therapy: Mental health counseling for young children and their caregivers that aims to decrease externalizing child behavior problems, increase positive parenting behaviors, and improve the quality of the parent‑child relationship. Parents are coached by Master’s level specially trained therapists in behavior‑management and relationship skills.

- Multisystemic Therapy: Intensive mental health program for older youth to promote pro‑social behavior and reduce criminal activity, mental health symptoms, out‑of‑home placements, and substance use. Master’s level therapists carry small caseloads and deliver the intensive interventions typically for a few months.

- Brief Strategic Family Therapy: Family therapy program for children and youth who display or are at risk for developing behaviors such as substance use, conduct problems, and delinquency. Trained counselors typically meet with families weekly for 12 to 16 sessions in community centers, clinics, or in home.

- Family Check‑Up: Family therapy program for children ages 2 through 17, aimed at building parenting skills and family management practices with the goal of improving child emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes.

- Functional Family Therapy: Family therapy program for at‑risk, older youth who have been referred for behavioral or emotional problems. Therapists typically meet weekly with families for three to six months.

- Homebuilders: Intensive home‑visiting program providing counseling, skill building, and support services for families who have children at imminent risk of out‑of‑home placement or who are in placement and cannot be reunified without intensive in‑home services.

- Motivational Interviewing: Method of counseling or more general case management practice that aims to identify ambivalence for change and increase motivation by helping clients prepare for and act on changes (including behavioral changes) needed to attain their personal goals. The plan includes practices for general case management and substance abuse treatment.

Federal Clearinghouse Ratings

The federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse rates programs as “well‑supported,” “supported,” “promising,” or not meeting criteria at the time of federal review. To make a rating, federal reviewers review available program evaluations and research studies that assess the program in question. The clearinghouse maintains a Handbook of Standards and Procedures, which lays out the specific criteria and methods used for rating programs. For example, reviewers consider program goals and how interventions are designed to meet those goals, how implementation is carried out, and to what extent program participation results in desired outcomes. The particular standards that programs must meet for each rating level in terms of design and execution and demonstrating positive outcomes are described in the nearby figure.

Federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse Ratings Criteria

|

Rating |

Standards to Achieve Rating |

|

|

Design and Execution |

Favorable Effects |

|

|

Well‑supported |

|

|

|

Supported |

|

|

|

Promising |

|

|

|

Does not meet criteria |

Programs that do not meet any of the other rating thresholds upon review of all studies are rated as not currently meeting criteria. |

|

There are a few advantages to states choosing well‑supported programs. First, these programs are proven to achieve results. Additionally, the federal Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) requires states to rigorously evaluate the evidence‑based practices (EBPs) they select; however, states can request to waive this requirement for well‑supported EBPs—thereby allowing states to avoid the costly process of intensive evaluation. (California has received waivers for all of its selected well‑supported EBPs.) Finally, FFPSA requires states to ensure that at least 50 percent of Title IV‑E funding received for prevention services goes toward well‑supported programs. (By choosing all well‑supported programs, California is guaranteed to meet this requirement.)

More detailed descriptions of these EBPs, along with additional information, can be found in Appendix A at the end of this publication.

Many of these EBPs (or versions of them) can already be found in parts of California to varying degrees. For example, according to the state plan, Nurse‑Family Partnership currently is operated (primarily by county public health departments) in 22 counties, and specially trained Master’s level therapists offer Parent‑Child Interaction Therapy in 40 cities. However, prior to FFPSA, none of these EBPs have been offered by child welfare agencies specifically as prevention services.

State Plan Identifies Many Characteristics of At‑Risk Populations. Candidates for Title IV‑E prevention services are individuals who are demonstrated to be at “imminent risk” of entry or reentry into foster care, and/or their parents or kin caregivers. Child welfare agencies must assess each individual candidate to determine their eligibility. (Pregnant or parenting foster youth are automatically eligible for prevention services and do not require individual assessments.) California’s state plan requires counties to assess individuals to determine candidacy using an “unbiased process and/or tools to assess risk.” (To aid counties in this assessment, DSS is working to develop a candidacy determination guide including concrete examples on how to assess for candidacy in an unbiased manner.) Specific groups which the state has identified in the state plan as targets for potential candidates—those with potentially higher likelihood of imminent need for foster placement, but who could remain safely at home with intervention (to be determined via the individual assessment)—include:

- Youth and families receiving voluntary or court‑ordered Family Maintenance services.

- Probation youth.

- Youth whose guardianship or adoption is at risk of disruption.

- Youth who are subject to a maltreatment allegation and investigation but for whom the court does not pursue a case.

- Youth with a sibling in foster care.

- Homeless or runaway youth.

- Substance‑exposed newborns.

- Youth who were victims of commercial sexual exploitation.

- Youth exposed to domestic violence.

- Youth whose caretakers experience substance use disorder.

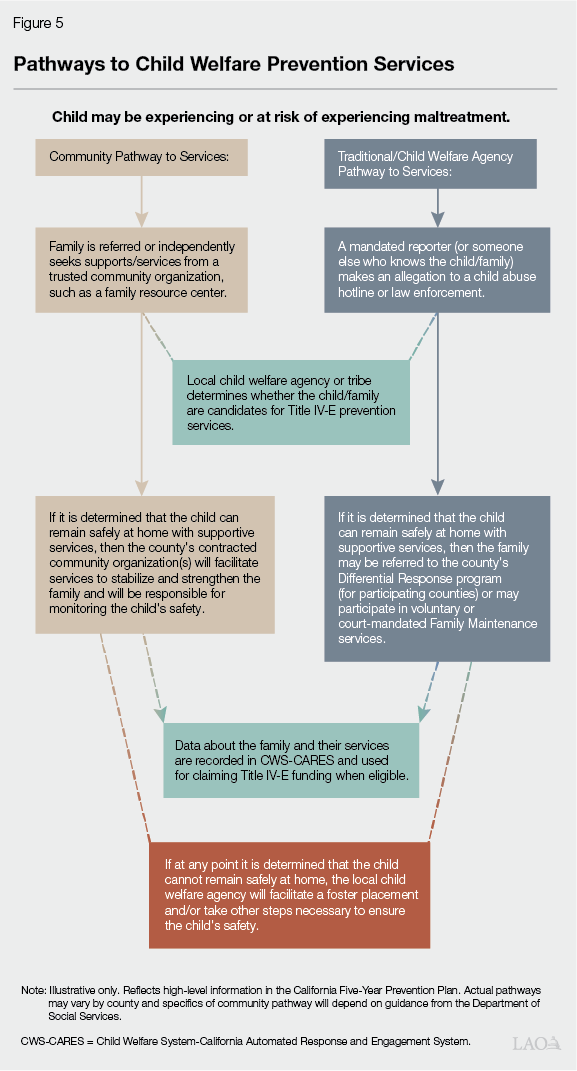

State Plan Allows Community Pathway for Connecting Families to Prevention Services. California’s state plan includes a “community pathway,” which is intended to support a “no wrong door” approach for families to access prevention services. Essentially, a community pathway will allow families to access prevention services prior to a call being made to the child welfare hotline, thus potentially mitigating for that family the trauma and stigma that can accompany formal child welfare system involvement. This is a novel approach to expand access for families to prevention services, and California is one of only a few states to include such an approach in its state plan. Under the community pathway outlined in California’s plan, a community‑based organization such as a family resource center—rather than the local child welfare agency—will be the family’s primary liaison to supports and services. The community‑based organization will be responsible for overseeing the child’s/family’s prevention services plan and ensuring the child remains safe in the home. The local child welfare agency still will need to be involved tangentially in the family’s case in that the agency will be responsible for confirming the child/family is an eligible candidate for Title IV‑E prevention services. Figure 5 illustrates a theoretical community pathway, compared to a traditional child welfare agency pathway.

DSS will provide additional guidance for counties around the specific requirements of implementing a community pathway. As one initial step, in March 2025, DSS published a community pathway framework brief, which details various activities that the state, local child welfare agencies, and community partners will need to complete as they take steps toward implementing county‑level community pathways.

Other State Actions

DSS Reviewed and Approved Counties’ Comprehensive Prevention Plans (CPPs). Counties opting in to receive state block grant dollars to help implement prevention services were required to create CPPs. (More information about the specific elements of CPPs and counties’ efforts in completing them is provided in the next section.) CPPs go beyond the specific EBPs eligible for federal reimbursement and require counties to scope comprehensive prevention service offerings to serve their local populations. In addition to preparing the state plan, DSS reviewed and approved counties’ individual CPPs, which were required to be completed and submitted to DSS by July 2023. To assist counties in developing their CPPs, DSS shared guidance, offered technical assistance, and provided templates for counties to use.

Coordination With County Behavioral Health and Medi‑Cal. FFPSA specifies that Title IV‑E funding is the “payor of last resort.” This means that, for EBPs that already may be funded (partially or wholly) by Medicaid or other federal sources, counties must first draw down those other eligible funding streams prior to receiving Title IV‑E dollars. Beyond the scope of child welfare programs, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) is working to implement a number of statewide reforms to Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. These health care reforms include efforts to expand coverage of EBPs available under Medi‑Cal. In May 2025, DHCS clarified (via a joint DSS/DHCS all‑county letter) Medi‑Cal coverage for EBPs focused on children and youth, including some of the ten EBPs which DSS included in the State Prevention Plan for FFPSA. All county behavioral health plans are required to cover these services for Medi‑Cal‑enrolled youth under the age of 21. Additionally, DHCS is supporting counties to develop their capacity to deliver these services to eligible youth and families who access them as prevention services.

The two departments plan to provide additional guidance on model fidelity standards for the EBPs, Title IV‑E prevention services that intersect with Medi‑Cal services, and a model joint written protocol related to payor of last resort.

Prevention Training for Child Welfare Workforce. FFPSA requires states to provide training and support for caseworkers in assessing what children and their families need, connecting to the families served, knowing how to access and deliver the needed trauma‑informed and evidence‑based services, and overseeing and evaluating the continuing appropriateness of the services. Training for California’s child welfare social workers and other child welfare staff is provided by five regional training academies (collectively referred to as CalAcademies), which offer training on a wide variety of topics and professional educational opportunities for child welfare staff. Most of the CalAcademies are affiliated with regional University of California and California State University campuses, alongside Los Angeles County’s child welfare training department. CalAcademies also track workforce training and conduct evaluations of child welfare staff through pre‑ and post‑surveys using an online learning and management system. In the State Prevention Plan, DSS describes a three‑tiered training approach to ensure child welfare staff and community providers are prepared to implement prevention services:

- Tier 1 focuses on prevention principles and consists of a series of webinars for county staff, community‑based organization staff, and tribal staff at all levels.

- Tier 2 focuses on specific elements of FFPS program requirements, such as candidacy and eligibility and monitoring and risk assessment. These trainings are more targeted toward child welfare caseworkers/other county child welfare staff.

- Tier 3 focuses on implementing EBPs. Trainings are targeted toward providers as well as child welfare staff.

Initial trainings under Tier 3 have been provided, and DSS released guidance (via All‑County Letter 25‑73) in October 2025 with more detail about the specific training sessions and required participants for Tier 1. Curriculum development for Tier 2 is ongoing and guidance will be released in the coming months.

DSS Administrative Progress. To help guide ongoing FFPS program development, DSS formed the FFPS Advisory Committee, tasked with monitoring and advising on program implementation. The committee includes subcommittees focused on the community pathway, Title IV‑E advisory, training and technical assistance, continuous quality improvement (CQI), and fiscal advisory. The FFPS Advisory Committee was launched in spring 2023 and meets quarterly. Additionally, as DSS often does when implementing new, significant program changes, the department hired some third‑party contractors to assist with various elements of FFPS implementation. For example, DSS contracted the Child and Family Policy Institute of California (CFPIC) to help coordinate and communicate with counties and other program stakeholders. CFPIC has conducted numerous technical assistance webinars, helps coordinate the FFPS Advisory Committee and its subcommittees, and maintains a consolidated cache of program resources online. DSS also contracted Chapin Hall to develop a series of CQI frameworks with specific outcome and model fidelity measures for each of the state’s selected EBPs. In March 2025, Chapin Hall published a statewide CQI plan and also has published individual EBP frameworks for each of the state’s selected EBPs (all available online through CFPIC’s resources webpage).

Counties’ Prevention Plans

While DSS has provided state‑level guidance as described above—because California’s child welfare system is state‑supervised and county‑administered—actual implementation decisions are made by counties and vary across the state. This section details the steps counties have taken toward full implementation of FFPS program prevention services. Our analysis is informed by our review of counties’ comprehensive prevention plans, as well as by conversations with various counties.

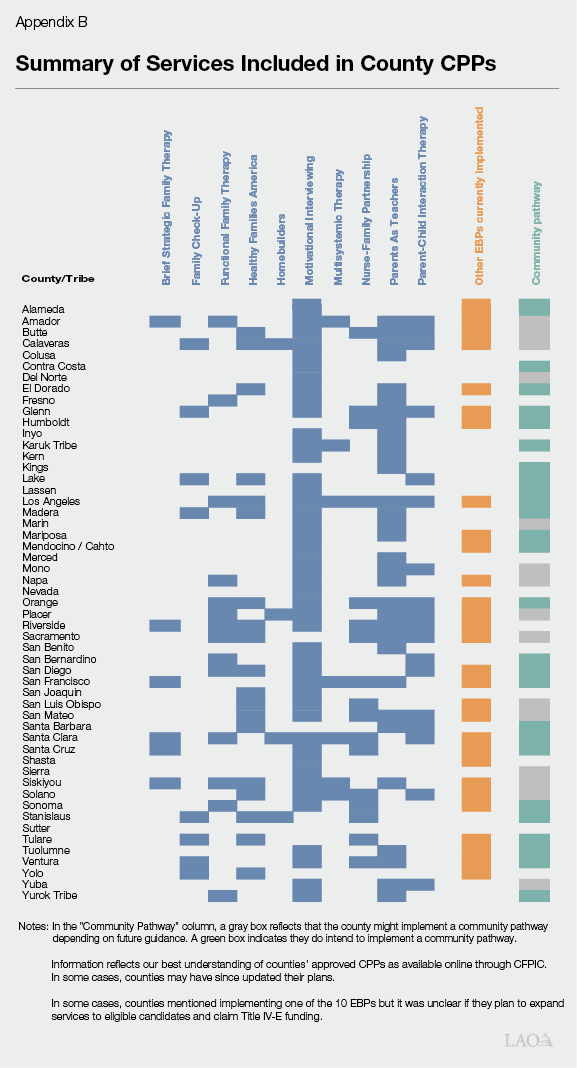

Counties Prepared Individual Prevention Plans

To Receive State Block Grant Funding, Counties Developed CPPs. As noted earlier, the state provided $222.4 million in 2021‑22, with multiple years of expenditure authority, to support counties with initial implementation of prevention services under the FFPS program. Prevention services are an optional child welfare program; counties are not required to participate. Ultimately, 51 counties and 2 Title IV‑E tribes opted to participate and are receiving the one‑time state block grant dollars. To participate, DSS required counties to prepare CPPs for approval by DSS. CPPs are intended to go beyond the scope of EBPs eligible for Title IV‑E funding to encompass other services and broader community‑based initiatives as counties deem relevant for their populations. In developing CPPs, counties conducted needs and capacity assessments, mapped current services and providers, defined the specific EBPs and other prevention services they will implement and who the target populations will be, and more. Counties will continue to scope their programs and build the needed capacities to deliver their selected services in the coming years. We describe some trends from the counties and their CPPs in the next several paragraphs. (Appendix B offers more detail regarding which counties selected specific EBPs.)

Most Counties Noted Benefits of the Process of Developing CPP. During discussions with various counties across the state, nearly all of the counties we met with shared that they found the process of developing a CPP beneficial. In particular, counties noted that mapping their current services and defining existing strengths as well as service gaps and needs—which they were required to do in coordination with local behavioral health, education, tribal leadership, service providers, and other stakeholders—was a useful endeavor and helped to strengthen existing cross‑sector relationships. However, some counties also experienced some challenges around cross‑sector coordination, noting communication silos and difficulty engaging certain groups.

In Their CPPs, Counties Identified Existing Strengths… As part of their capacity self‑assessments within their CPPs, around 20 counties described existing strengths to include county leadership and other partners having good existing collaboration and communication, strong motivation for change, and commitment to prevention services. Around one‑third of counties (especially larger and more urban counties, as well as some more medium‑sized counties) additionally noted that they benefit from numerous existing community‑based organizations and family resource centers with some existing capacity to implement EBPs.

…And Service Needs, Gaps, and Challenges. Across the board, counties described as part of their capacity self‑assessments within their CPPs the acute need for more mental health and substance use disorder services (even those counties with some existing capacity tended to note these service gaps). Counties described how the current services offered in these areas may not be the most effective interventions for the specific populations at greater risk of potential involvement with the child welfare system (such as groups experiencing poverty at higher rates and groups with linguistic and/or cultural barriers). Counties additionally stated that stakeholders and other service recipients often noted the need for more family‑friendly service options, child care, transportation, and other related services in order to access services. Many counties also discussed the need for domestic violence services. Counties also noted an existing need for programs providing concrete supports, such as housing assistance, especially in areas with higher cost of living. More rural, mountainous, and geographically large counties described logistical challenges to service delivery, such as lack of transportation and difficulties reaching and engaging with communities in more remote areas of the county. Around 20 counties (especially smaller and more rural counties) also noted an overall shortage of service providers, in particular providers possessing the resources to deliver EBPs to model fidelity. (We discuss some of these issues more in the next section.)

Trends Within Target Populations. Counties took varying approaches to identifying the specific populations and groups within their borders for whom they will focus their prevention efforts. Some counties identified target populations based on risk factors, such as children whose caregivers are experiencing substance use disorder, children exposed to domestic violence, families with a general neglect allegation but no case opened, or families participating in family maintenance services. Other counties chose broader groups, such as children ages zero to five (who often have the highest rates of entry into foster care by age) or older youth (who may have more intensive behavioral health support needs). In some other cases, counties identified communities by geography, such as those living in certain zip codes with higher rates of foster care entry or those in more remote areas of the county who historically have had lower levels of access to services.

Counties Selected Some EBPs From the State Plan

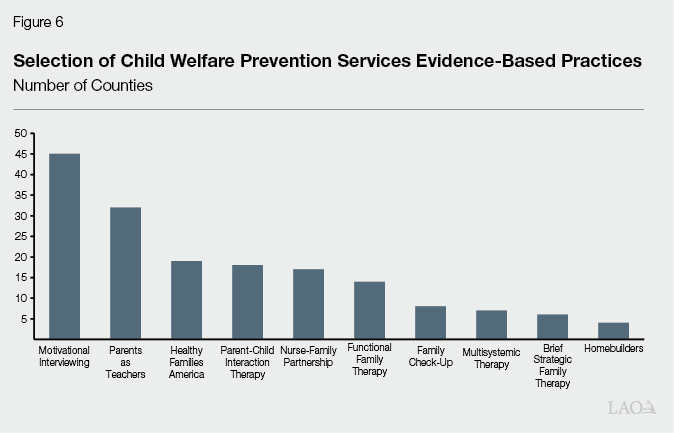

Most Commonly Selected EBPs From the State Plan. By selecting EBPs from the state plan, counties eventually will be able to claim Title IV‑E funding reimbursement for eligible candidates who receive those services. Of the ten EBPs included in the state plan, the most commonly selected practice is Motivational Interviewing (MI), with all but a few counties including MI in their CPPs. Based on conversations with counties, many counties opted to include MI in their CPPs because it is a practice that is broadly applicable to many different target populations, it can be implemented internally (rather than relying on external service providers to implement a specific program), and—relative to other EBPs—the training and model fidelity requirements are less onerous. Additionally, some counties note that child welfare staff and/or staff of partner organizations already use MI or similar models and have achieved positive results, making MI the most straight forward to implement of the state’s ten selected options. After MI, the most frequently selected EBP is Parents as Teachers, which over half of counties included in their CPPs. Roughly one‑quarter to one‑third of counties selected Functional Family Therapy, Healthy Families America, Nurse‑Family Partnership, or Parent‑Child Interaction Therapy. Smaller numbers of counties opted for the remaining EBPs included in the state plan. Figure 6 illustrates how many counties selected each EBP in their CPPs. Appendix B provides a full list of which counties selected each EBP.

FFPS Provides Opportunity to Expand Existing Services to Child Welfare Populations With Federal Funding. Implementing FFPS provides counties an opportunity to expand some already offered services to focus on maltreatment prevention. For example, around 20 counties included Nurse‑Family Partnership as a selected EBP in their CPPs. In most of these counties, the local public health department already delivers this program (typically serving first‑time, low‑income mothers and infants). To implement the service as a child welfare prevention program, local child welfare departments will contract with their public health counterparts to expand the program for eligible child welfare candidates. In addition, DHCS and DSS recently instructed county behavioral health plans to cover certain EBPs focused on children and youth behavioral health for youth up to age 21 enrolled in Medi‑Cal. These services include: Parent‑Child Interaction Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy, and Functional Family Therapy. For counties that already have providers who are able to offer these services, counties could coordinate with local behavioral health to expand access to these treatment models for their target child welfare prevention populations.

Counties’ CPPs Also Include Other Prevention Services Not in the State Plan

Many Counties Also Implement Other EBPs Not Included in the State Plan. Beyond the ten EBPs included in the State Prevention Plan, more than half of participating counties indicated in their CPPs that they have providers in their communities currently delivering other EBPs. Whether providers are able to meet fidelity standards for the program models is sometimes unclear, however. In some cases, these EBPs are included in the federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. However, because DSS did not include them in California’s state plan, counties are not able to receive Title IV‑E funding for them as child welfare prevention services. For example, in their CPPs, a number of counties specified that their local providers currently offer EBPs such as Mindfulness‑Based Cognitive Therapy (rated as well‑supported), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (rated as supported), Positive Parenting Program (various models rated as promising), and other therapy and program models.

Some Counties Also Include Wraparound as a Prevention Service. Wraparound refers to the practice of partnering with families to provide intensive services to children and families with complex needs using a team‑based approach. A child and family, working with a team of service providers, develops and follows a service plan that is intended to be comprehensive, family‑centered, strengths‑based, and needs‑driven. Since 2022, all counties have been required to provide wraparound services to foster youth transitioning out of congregate care placements for at least six months. This state requirement aligns with federal requirements under FFPSA, as described more in the nearby box. Additionally, all counties are in the process of updating their wraparound services to align with new, higher‑level statewide standards—referred to as “high fidelity wraparound.” High fidelity wraparound is a “promising” practice in the federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. Some counties included high fidelity wraparound services as part of their CPPs. However, because the EBP is not included in the state’s prevention plan, counties will not be able to receive Title IV‑E funding for it even if they choose to expand this service to eligible candidates for foster care.

California High Fidelity Wraparound

In addition to implementing prevention services as allowed by the federal Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), California also is implementing separate, required components of FFPSA related to congregate care. Specifically, FFPSA requires states to make certain changes in order to retain eligibility to claim Title IV‑E reimbursement for congregate care foster placements. One of these new federal requirements specifies that youth transitioning out of a congregate care placement must receive planning and support for at least six months post‑discharge (that is, aftercare services). Counties and their providers are responsible for meeting this new requirement by way of wraparound services (with models differing across counties and providers). In July 2025, the Department of Social Services and the Department of Health Care Services published guidance (via All‑County Letter 25‑47) for California High Fidelity Wraparound as the state’s uniform model of aftercare services. Counties and providers are now working to ensure their wraparound services achieve these statewide standards.

A Number of Counties Implement Culturally Relevant Programs. Around 20 counties—particularly those with significant Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino populations—describe in their CPPs that they are currently implementing programs that aim to serve specific communities using culturally informed, strengths‑based, and linguistically relevant approaches. For example, a number of California counties have “cultural broker” programs, which are community‑led initiatives that work with Black families who have an open child welfare case (or are at risk of child welfare system intervention). Through these initiatives, community members—who typically also have been involved with the child welfare system—support families by helping to facilitate interactions with social workers and the courts, and to navigate the array of county and local services. Similarly, a number of counties offer “promotoras y promotores” programs, which offer a similar model specifically tailored for Hispanic/Latino/Spanish‑speaking communities. These program models are not currently included in the federal clearinghouse. However, some counties have evaluated their programs and found them to reduce the number of families that enter foster care and increase family reunifications.

Several counties with significant tribal presence also partner with local tribes/tribally led organizations to implement culturally relevant and community‑led programs. For example, several counties mention in their CPPs that they offer the Family Spirit program. This program is a home visiting model for young Native American expectant and parenting mothers, with the goal of addressing intergenerational behavioral health challenges and promoting positive behavioral and emotional outcomes among mothers and children, while also helping families process historical traumas by embracing local languages, legends, and Native American history. Family Spirit is rated as a promising practice in the federal clearinghouse.

Counties’ Implementation Challenges

Since counties have begun to implement their CPPs, they have encountered a variety of challenges—some anticipated and some not. In this section, we describe some trends across counties in terms of these identified hurdles, based on discussions with counties and other stakeholders. Where relevant, we also have noted steps DSS is taking to help mitigate these challenges. Because implementation is underway, new guidance to help address challenges is issued regularly. As such, we have tried to include the most up‑to‑date information in our analysis. However, as implementation proceeds, some of these challenges may resolve and others may emerge.

Implementing EBPs

Array of EBPs in State Plan Does Not Always Correspond to Counties’ Prevention Needs. Some counties noted a general lack of alignment between the needs of their populations and the EBPs that are included in the state prevention plan (and even more broadly in the federal clearinghouse). For example, many counties selected target populations for prevention services based on identified risk factors, such as children whose caregivers are experiencing substance use disorder, children exposed to domestic violence, and families with a general neglect allegation but no case opened. At the same time, only one of the state’s selected EBPs (MI for substance use) directly aims to mitigate caregiver substance use disorder as its primary goal. Moreover, no programs in the federal clearinghouse are focused primarily on supporting children/families exposed to domestic violence, nor are there any programs in the federal clearinghouse that focus on providing concrete supports (which could help address factors underlying general neglect allegations).

State Plan Omits EBPs That Counties Already Provide. As described earlier, counties currently provide various EBPs that are in the federal clearinghouse but were not included in the state plan. As a result, counties cannot claim federal funding for these services despite being approved at the federal level. However, adding them to the state plan is not without trade‑offs. Specifically, including EBPs federally rated as supported or promising (rather than well‑supported) likely would require the state and counties to take on new costs to meet federal monitoring and evaluation requirements. (We discuss these trade‑offs in more detail in the next section.)

Limited Selection of EBPs That Are Culturally Relevant. Many counties noted that the state plan and federal clearinghouse more generally include few programs specifically designed for communities who disproportionately face child maltreatment risks, such as higher‑poverty Black and Native American communities. Given the significant overrepresentation of these groups in California’s child welfare system, counties noted that this lack of culturally specific services could potentially limit the effectiveness of programs for these populations. That said, the state plan does describe culturally relevant programs as an important focal area for California’s overall prevention vision.

Capacity of Providers. Most counties raised that community‑based organizations and other service providers could face challenges in implementing EBPs in line with federal requirements. Particularly in smaller and more rural counties with relatively fewer providers, counties raised issues related to hiring and maintaining qualified staff and meeting EBP model fidelity requirements around staff training, data tracking, and other elements due to high costs. Building provider capacity is a focal area for DSS and its contractors through the three‑tiered statewide training initiative and by developing resources and guidance.

Funding and Accounting Challenges

All counties discussed concerns and complexities surrounding prevention services funding. We describe these challenges in this section.

Title IV‑E Claiming. As described in the background, Title IV‑E reimbursement in California generally requires counties to spend $1 from local sources for every $1 of federal monies claimed. Counties currently may seek Title IV‑E reimbursement for administration and training activities in preparation for implementing EBPs. They are not able to receive Title IV‑E reimbursement for the prevention services provided until the state’s new child welfare data system—Child Welfare System‑California Automated Response and Engagement System (CWS‑CARES)—launches. The statewide launch of this new system is planned for October 2026. Prior to the new system coming online, counties cannot claim Title IV‑E funds for prevention services because the state’s legacy child welfare data system does not meet federal requirements around individual‑level prevention services tracking and outcomes reporting. As a result, counties can only use local and state block grant dollars to implement new or expand existing prevention services in the meantime. Some counties are taking the approach of trying to hold off on using some of their state block grant dollars until they can begin drawing down Title IV‑E matching funds. Other counties report having spent nearly all their state block grant dollars already—well in advance of being able to use these one‑time state resources as the required local match to receive federal reimbursement.

Medi‑Cal Funding and Billing. Given that federal rules specify Title IV‑E is the payor of last resort, and some EBPs are Medi‑Cal‑eligible services, counties expressed a need for clear guidance from the state related to Medi‑Cal billing and how different funding streams can be used together. While DSS and DHCS have provided some guidance related to Medi‑Cal coverage for certain EBPs (as described earlier), counties report continued confusion and the need for more detailed and individualized guidance around braiding together Medi‑Cal, Title IV‑E, and other funding sources. Additionally, some counties shared concerns that their EBP providers may not have the staffing or resource capacity to take on the complexities of direct Medi‑Cal billing.

Cost of Implementing to Model Fidelity. Most EBP models are “owned” by the service developer/purveyor, which is the entity (such as a university or independent service provider) responsible for creating and supporting the implementation of the EBP. They provide training, resources, and guidance to ensure fidelity and effective implementation, often charging counties or the service provider fees to do so. In some cases, counties shared that it would cost them several hundreds of thousands of dollars to contract with the developer/purveyor to provide the required initial training and guidance to begin implementing an EBP. In these cases, some counties ultimately decided not to pursue implementation of EBPs that they had included in their CPPs due to the costs. As a result, DSS is exploring a potential state‑level contract to assist counties with meeting model fidelity requirements, specifically for MI.

Funding Sustainability. A challenge that nearly every county emphasized is how to sustain their prevention programs financially once their state block grant dollars expire. Even once CWS‑CARES launches and counties can claim Title IV‑E reimbursement for eligible EBPs, how to fund the required local match remains a challenge for counties. Counties receive their flexible 2011 realignment funds for child welfare programs—which DSS has indicated counties will be able to use as the ongoing local funding component—but some counties report exhausting these funds to provide the basic mandatory child welfare program components. As the state block grant period draws to a close over the next few years, counties will be looking to DSS for more guidance and individualized financial planning assistance to sustain their prevention programs.

Other Challenges

Staffing Challenges. Nearly all counties noted in their CPPs and during conversations that they struggle to recruit and retain child welfare social workers (and oftentimes local service providers face similar challenges). This is a general challenge local child welfare agencies face, not specifically related to prevention services. Insufficient staffing can make implementing new initiatives difficult. More specifically related to staffing EBPs—because EBPs require relatively rigorous, often expensive training and ongoing monitoring—counties noted that staff turnover could add to the hurdles of meeting model fidelity requirements.

Questions Around Community Pathway. For counties that plan to implement a community pathway option (as described in the State Prevention Plan) for families to access services outside of the usual child welfare system pipeline, many questions remain around how the community pathway will work. Counties need more state guidance around the specific requirements, in some cases because they are still uncertain whether their community‑based organizations or family resource centers will have the capacity and resources to meet the requirements. A few counties have moved ahead with implementing their individual community pathways and are working with DSS to inform forthcoming guidance.

Need for More Specific and Tailored Technical Assistance. Some counties have hired their own contractors to help formulate their CPPs and guide implementation efforts. Other counties, however, are not able to do so. In particular for this latter group, counties expressed needing more in‑depth and individualized technical assistance from the state. Counties noted that the various webinars and other learning opportunities provided by DSS, state contractors, regional training academies, and others are helpful but tend to remain higher level.

Considerations and Opportunities for Legislature

In this section, we highlight some considerations for the Legislature alongside opportunities to provide additional direction and guidance to the administration and support for counties to help ensure implementation of child welfare prevention services can continue in a manner that (1) allows the state to maximize federal funding whenever possible and (2) helps promote prevention services that can benefit as many at‑risk families across the state as possible.

State‑Level Support for Model Fidelity. To support counties in meeting the often rigorous requirements surrounding EBP implementation, the state could consider state‑level contracts—or help facilitate regional contracts—for training and model fidelity monitoring. DSS already is exploring this option for MI, which is the EBP selected by nearly all counties in their CPPs. The Legislature could direct DSS to explore similar options for other EBPs, particularly the other services selected by the largest numbers of counties. This state‑level or regional‑level support could be particularly useful for smaller counties, for whom the cost of implementing EBPs to model fidelity could otherwise prove prohibitive.

Consider Updating State Plan to Include Other EBPs… The Legislature could consider directing DSS to update the State Prevention Plan to add additional EBPs from the federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. Specifically, the Legislature could direct DSS to include EBPs that multiple counties already implement (such as Mindfulness‑Based Cognitive Therapy and Positive Parenting Program models). Furthermore, given that high fidelity wraparound is included in the federal clearinghouse and that all counties will be implementing the California model of this program to meet FFPSA aftercare requirements, the Legislature could consider directing inclusion of this service in particular into the state’s prevention plan. Inclusion of these EBPs in the state plan would allow counties to receive Title IV‑E funding for these services when provided to eligible candidates. Additionally, by expanding the EBPs included in the state plan, counties could access federal funding for programs that potentially correspond more directly to their target populations’ needs (such as more services directly aiming to mitigate caregiver substance use).

…While Weighing Trade‑Offs. Importantly, however, inclusion of additional EBPs in the state plan would not be without trade‑offs. Namely, for any new services added to the plan that are rated as supported or promising, DSS would need to ensure that at least 50 percent of Title IV‑E dollars are claimed for well‑supported services. (Currently, because all EBPs included in the state plan are rated as well‑supported, meeting the 50 percent federally required threshold is not a concern.) Additionally, for services rated as supported or promising, DSS and counties could face new cost pressures related to federal evaluation requirements. (Again, because all currently included EBPs are well‑supported, DSS was able to obtain waivers for some of the federal evaluation requirements.) The Legislature may want to weigh the opportunity for counties to obtain additional Title IV‑E dollars against these trade‑offs in consultation with the administration prior to directing an expansion of EBPs in the state plan.

Consider How to Maximize Medi‑Cal Coverage for EBPs. In addition to considering expanding access to Title IV‑E funding for additional child welfare prevention services, the Legislature also could consider how to maximize Medi‑Cal coverage for eligible EBPs. Specifically, considering that local behavioral health plans are required to provide coverage for Parent‑Child Interaction Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy, and Functional Family Therapy, what steps could the state take to expand access to these services for eligible child welfare prevention candidates? Additionally, are there other child welfare prevention EBPs (either currently included in the State Prevention Plan or to be considered for future inclusion) that also could be covered by Medi‑Cal?

Explore Options for Submitting Other Programs to Clearinghouse. Aside from the EBPs already included in the federal clearinghouse, many counties implement other programs—such as cultural broker programs—that counties have found to be effective for their target populations. The Legislature could work with the administration to explore options for submitting such programs to the federal clearinghouse for review and potential rating. This effort would help address existing gaps, particularly in terms of culturally relevant prevention programs that could be eligible for federal dollars. Additionally, currently there are no programs in the federal clearinghouse focused on serving families exposed to domestic violence or providing concrete supports to families—yet these are some of the needs of target populations counties identified in their CPPs. The Legislature could work with the administration to understand what options exist to pursue expansion of the federal clearinghouse to include such programs.

Consider What Data Legislature Would Want for Future Evaluation. Implementing child welfare comprehensive prevention services is a major undertaking and emblematic of a broader shift within child welfare policy over time to focus more on preventing entry into foster care. Additionally, the state block grant funds of $222.4 million General Fund represent a significant discretionary augmentation for child welfare programs. As such, the Legislature likely will want effective measures for assessing the impact these funds and new services are having. Given that many counties are still in the relatively early phases of implementing their CPPs (and are not yet able to claim Title IV‑E funding for eligible prevention services), now is an opportune time for the Legislature to consider what specific data and outcomes measures it will want in the future. For any determined measures that DSS/counties do not currently report on, the Legislature could direct any necessary additional data collection now to ensure impacts may be measured over time. Regardless of any new data collection the Legislature may wish to add, the state will collect the federally required data elements once the new child welfare data system (CWS‑CARES) comes online. These data will include basic demographic information alongside tracking the specific prevention services that individual children/families receive, the cost of those services, and the status of the child/family 12 months after receiving prevention services (for example, has the child entered foster care).

Consider Long‑Term Funding Sustainability for CPPs… While the state block grant funds provide counties with new resources to implement child welfare prevention programs, the funding is one time. Future access to Title IV‑E reimbursement for prevention services will continue to require local matching contributions. Moreover, the Title IV‑E funding comes with numerous requirements and counties may not always be able to draw down any federal support for their programs (to the extent that they choose to implement services beyond the EBPs included in the State Prevention Plan). For example, some important types of prevention programs for at‑risk families—such as concrete supports and domestic violence intervention—are not currently eligible for Title IV‑E financial participation.

…Particularly in Light of the Incentives and Trade‑Offs of Realignment. Under 2011 realignment, counties have a fiscal incentive to deliver effective CPPs whether or not the state provides General Fund funding: effective prevention services should mean fewer families entering foster care, thereby lowering counties’ realigned child welfare program costs while allowing them to retain the savings. However, the reality is more complicated, with many factors that contribute to families’ risk for child maltreatment—such as poverty—existing far outside of local child welfare agencies’ control. Additionally, numerous counties report that growth in their baseline child welfare program costs exceeds realignment funding growth, leaving them without room in their realignment budgets for new or discretionary programs. Under 2011 realignment, however, the state has limited insight into how counties use their realignment dollars, making it difficult to assess the true impact of various cost pressures. Whenever considering increased program requirements and/or funding for child welfare—as a realigned program area—we recommend bearing these complex factors in mind.

Timing for Any Additional State Funds Is Important. In theory, counties will achieve foster care cost savings once they implement effective child welfare prevention services—meaning there is a natural incentive to invest in prevention programs. However, achieving those savings will require significant upfront investment, which may not be possible using only local funds. Many counties stated that they already have spent all or most of their state block grant dollars—prior to being able to claim any Title IV‑E matching funds for eligible EBPs. Because federal reimbursement for prevention services will require $1 local funding to match every $1 of federal monies claimed—and given the constraints and complexities of counties’ local realignment dollars described in the previous paragraph—some counties may not be in a position to provide the needed matching funds. Given these factors, to the extent the Legislature may be in a future position to provide additional one‑time state resources, another round of state block grant funding for counties’ child welfare prevention programs could be an area to consider. However, before providing any additional funding, we recommend first ensuring that a couple of conditions are met to help counties maximize federal funding and create financial sustainability for prevention programs beyond the duration of any state funding. First, any future funding should be provided after the launch of CWS‑CARES (anticipated for October 2026) to ensure counties are able to claim federal Title IV‑E reimbursement for eligible services. Second, detailed Medi‑Cal claiming guidance should be available to ensure counties and providers are able to draw down Medi‑Cal funding for eligible services. Once these conditions are met, additional state block grant funding could help counties begin generating savings—thereby promoting long‑term funding sustainability.

Conclusion

California has undertaken significant efforts toward implementing the state’s new prevention services program available for federal Title IV‑E reimbursement under FFPSA. Additionally, California’s policy goals for prevention services extend beyond the scope of EBPs eligible for Title IV‑E reimbursement and aim to include wider local arrays of services that can respond to the needs of at‑risk populations across counties. This move toward prevention is a major shift in child welfare policy focus that will take time to implement. There remains much to be done before the state and counties can realize the full extent of federal benefits. As counties have taken steps toward implementing their individual comprehensive prevention plans, some key challenges and opportunities for additional legislative guidance and input have come to light. As the state remains in the relatively early phases of implementation, now is a good time for the Legislature to weigh in to help ensure prevention services work can continue efficiently and benefit as many at‑risk families as possible across the state.

Glossary

|

Acronym/Term |

Definition |

|

Candidacy |

A “candidate for foster care” is a child at imminent risk for removal from their home and foster placement. This is defined more specifically by states, and is an individual child or family eligible for federal Title IV‑E financial participation for prevention services. |

|

Community Pathway |

California’s new federally allowable approach for families to access prevention services, without formal involvement of the local child welfare agency. Counties have the option of implementing their own local version of this approach—in line with state guidelines, which are under development. |

|

Comprehensive Prevention Plans (CPPs) |

These are the state‑required plans that counties prepared in order to opt in to receive state block grant dollars. |

|

Culturally Relevant Program |

A program utilizing an approach that incorporates the unique cultural and linguistic norms and needs of a community. |

|

Evidence‑Based Practices (EBPs) |

These are specific program/service models that have been rated by the federal clearinghouse as having sufficient evidence to support the program’s ability to achieve its intended positive outcomes amongst the target population. |

|

Federal Clearinghouse |

The federal Title IV‑E Prevention Services Clearinghouse, which rates evidence‑based practices as “well‑supported,” “supported,” “promising,” or not meeting criteria at the time of federal review. The clearinghouse maintains a Handbook of Standards and Procedures, which lays out the specific criteria components and methods used for rating programs. |

|

Family First Prevention Services Program (FFPS) |

California’s state program to implement FFPSA and prevention services more broadly. |

|

Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) |

Federal law requiring various changes to states’ child welfare practice and allowing states the option to claim Title IV‑E funding for certain evidence‑based services for child welfare prevention. |

|

Motivational Interviewing (MI) |

One of California’s selected evidence‑based practices. |

|

Model Fidelity |

Refers to how closely an implemented program adheres to the original, evidence‑based model on which it is based. A program delivered to high fidelity refers to a program that is implemented as designed in terms of factors such as planning and implementation phases, staff qualifications and training, data collection, and tracking outcomes. |

|

State Block Grant |

State General Fund funding provided to counties that opted in to provide child welfare prevention services under FFPS. The 2021‑22 Budget Act provided $222.4 million for this purpose. |

|

State Plan |

California’s Five‑Year State Prevention Plan, as required by the federal government to allow California to claim Title IV‑E financial participation for select prevention services delivered to eligible candidates. |

|

Title IV‑B |

Funding provided to states via Title IV, part B of the federal Social Security Act. Funding supports broad child welfare and prevention programs. |

|

Title IV‑E |

Funding provided to states via Title IV, part E of the federal Social Security Act. Funding supports primarily foster care, adoptions, and guardianships. |

|

Title IV‑E Pathway (Also Referred to as Traditional Pathway) |

The traditional way in which families access prevention services, meaning their case is brought to the attention of the local child welfare agency. |

Appendix A

Appendix A

Overview of Evidence‑Based Practices Included in State Plan

|

Program/Service |

Target Group |

Intended Outcomes |

Fidelity Indicators |

Type of Service |

Clearinghouse Rating |

|

Nurse‑Family Partnership (NFP) |

First‑time parents/caregivers with a child under two years of age (beginning prenatally). |

|

|

|

Well‑supported |

|

Description |

|||||

|

Home visiting program that is typically implemented by trained registered nurses. NFP serves young, first‑time, low‑income mothers beginning early in their pregnancy until the child turns two. The primary aims of NFP are to improve the health, relationships, and economic well‑being of mothers and their children. Typically, nurses provide support related to individualized goal setting, preventative health practices, parenting skills, and educational and career planning. However, the content of the program can vary based on the needs and requests of the mother. NFP aims for 60 visits that last 60‑75 minutes each in the home or a location of the mother’s choosing. For the first month after enrollment, visits occur weekly. Then, they are held bi‑weekly or on an as‑needed basis. |

|||||

|

Healthy Families America (HFA) |

Parents/caregivers with a child who is newborn to five years of age, generally starting within three months of birth. |

|

|

|

Well‑supported |

|

Description |

|||||

|

Home visiting program for new and expectant families with children who are at‑risk for maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences. HFA is a nationally accredited program that was developed by Prevent Child Abuse America. The overall goals of the program are to cultivate and strengthen nurturing parent‑child relationships, promote healthy childhood growth and development, and enhance family functioning by reducing risk and building protective factors. HFA includes screening and assessments to identify families most in need of services, offering intensive, long‑term and culturally responsive services to both parent(s) and children, and linking families to a medical provider and other community services as needed. Each HFA site is able to determine which family and parent characteristics it targets. Enrollment begins prenatally and continues up to three months after birth. Most families are offered services for a minimum of three years, and receive weekly home visits at the start. After six months, families receive visits less frequently depending on their needs and progress. |

|||||

|

Parents as Teachers (PAT) |

Parents/caregivers with a child who is newborn (or beginning prenatally) to kindergarten age. |

|

|

|

Well‑supported |

|

Description |

|||||

|