Our office has released a report that was requested earlier this year by the Legislature concerning options for a California state earned income tax credit (EITC). As we discuss there, many state EITC proposals build off of the federal EITC.

What is the Federal EITC? The federal EITC is a provision of the federal income tax code that allows taxpayers with total income below a certain level to reduce their tax liability by an amount that depends on their “earned income,” which primarily includes wages and self-employment income. (Earned income does not include such sources as interest income, retirement income, or unemployment benefits.) The federal EITC was established in 1975. Initially, it was intended to compensate lower-income workers for the federal payroll taxes that fund the Social Security and Medicare programs, and the amount of the credit was limited to the taxpayer’s payroll tax liability up to a certain income level. Over time, its purpose became to increase the rewards to paid work and reduce poverty. It was expanded significantly in 1986, 1990, and 1993 to the point where its benefits greatly exceed payroll tax liabilities for most beneficiaries. The EITC has become a major federal antipoverty program with a total cost of $64 billion in 2012, spread over nearly 28 million tax returns.

EITC Can Reduce Liability Below Zero. As the name suggests, the EITC is a federal tax credit. This means that its value is used to reduce a taxpayer’s final federal income tax liability, after computing taxable income and then applying the relevant tax rates. This is in contrast to a deduction, which is used to reduce taxable income before rates are applied. The federal EITC is a “refundable” credit, meaning that if the amount of a taxpayer’s EITC is greater than his or her liability before applying the credit, then the federal government actually owes the taxpayer money for that year. For example, if a person’s tax liability excluding the EITC is $200 and the calculated EITC amount is $500, then the final liability including the EITC is negative $300: the federal government owes the taxpayer $300. In contrast, if the credit were “nonrefundable,” the taxpayer’s liability could not be reduced below zero even if the EITC amount were greater than the liability excluding the EITC.

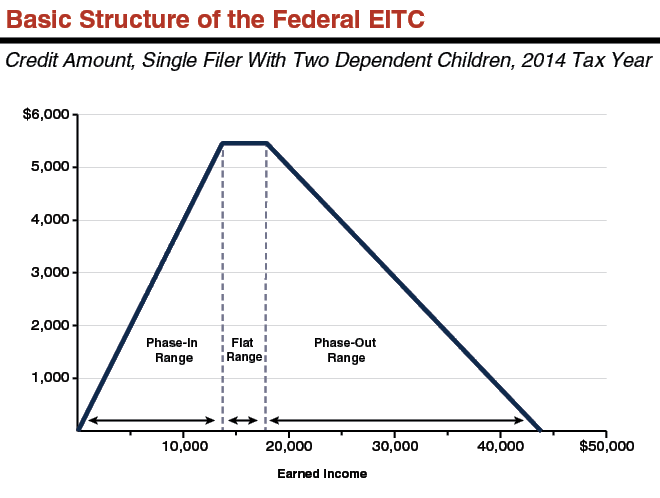

As Income Increases, Credit Amount Rises, Then Phases Out. The EITC benefit schedule depends on the number of dependent children the taxpayer has and on whether they are filing a single or joint tax return. In every case, as shown in the figure below, the EITC has:

- A “phase-in” range of earned income where the total EITC amount steadily increases with every dollar earned. For the example shown in the figure below, the taxpayer receives 40 cents in credit for each dollar earned over this range.

- A “flat” range where the taxpayer gets the maximum possible EITC amount for their filing status and number of dependents, and additional earned income does not affect the amount of the EITC benefit. For the example shown below, the taxpayer would receive the maximum benefit of $5,460 over this range.

- A “phase-out” range where the total EITC amount declines steadily with every dollar earned. For the example shown below, the taxpayer would lose about 21 cents in credit for each dollar earned over this range.

More information on the federal EITC is in our report. Additional information on the EITC will also be posted here on the LAO California Economy and Taxes blog.