Series

Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

Update 6/13/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 May Revision.

Update 1/20/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 Governor's Budget.

September 30, 2016

Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

An Update on the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Condition

(This post updated 6/13/17 to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 May Revision.)

This post is the first in a series of four posts that collectively will (1) review the current condition of the unemployment insurance (UI) trust fund and how it may change in the near future, (2) provide context on who pays UI taxes and how much they pay, (3) assess the extent to which the UI trust fund is prepared for the next economic downturn, and (4) look at potential steps the Legislature could take should it wish to increase reserves in the trust fund as a means to address the fiscal impacts of the next economic downturn. This first post will focus on the current condition of the trust fund.

The other posts in this series can be accessed using the nearby menu.

Background

UI Program Assists Unemployed Workers. The UI program provides weekly benefits, funded through payroll tax contributions paid by employers, to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The program is authorized in both federal and state law, and significant discretion is given to states to set benefit and employer contribution levels. Under current state law, weekly UI benefit amounts are intended to replace up to 50 percent of a claimant’s prior earnings, subject to a maximum of $450 per week, for up to 26 weeks.

UI Program Is Financed Through Employer Tax Contributions. Employers pay both state and federal UI payroll taxes. State UI tax revenues are deposited into the state’s UI trust fund to pay for benefits to unemployed workers. State UI tax rates are determined in accordance with a series of rate schedules laid out in state law. The schedules generally require higher rates, up to a statutory maximum of 6.2 percent of each employee’s first $7,000 in annual wages, when the condition of the UI trust fund is poor—meaning that it has a low level of reserves (as might occur following a recession). This rate structure is intended to allow for the fund’s reserve to be replenished when the fund condition is poor. When the trust fund reserve is larger, schedules with lower tax rates are in place. State UI tax schedules also require relatively higher tax rates for employers whose employees disproportionately receive UI benefits, in an attempt to allocate the costs of UI benefits to those employers whose employees benefit the most from UI. This practice is referred to as “experience rating.”

The federal UI tax, with certain exceptions discussed later, is typically used to pay for certain costs other than state benefit payments, such as program administration, and is set at a rate of 0.6 percent of each employee’s first $7,000 in annual wages.

The UI Trust Fund Is Insolvent

The state’s UI trust fund is insolvent, meaning that the cost of benefits exceeded employer tax contributions, the trust fund exhausted its reserves, and the state had to take on debt to pay for benefit costs. Below, we describe in greater detail the conditions that led the UI trust fund to exhaust its reserves and ultimately require the state to take on loans to continue benefit payments.

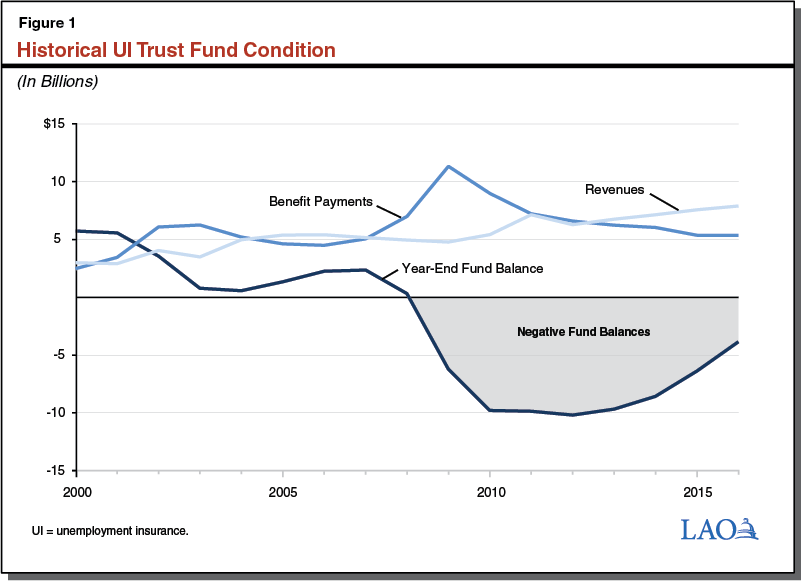

Trust Fund Reserves Ran Out in 2009. The UI trust fund exhausted its reserves in 2009 as the result of a combination of factors. In 2001, state legislation raised the level of UI benefits—increasing program costs—without increasing employer contributions. Over the long run, this has made it difficult for contributions to support benefit costs, particularly during periods of higher unemployment when demand for benefits is greater. As shown in Figure 1, due to significantly elevated levels of unemployment during the most recent recession, the total amount of UI benefits paid to workers substantially increased. However, because the state was already using the highest tax rate schedule even before the recession began (due to the already existing relatively poor condition of the UI trust fund), revenues from employer taxes did not increase to fully offset the dramatically higher benefit costs, leading the trust fund to exhaust its reserves.

California Receives Federal Loans to Continue Paying UI Benefits. Federal law provides for states that exhaust their UI trust fund reserves to receive loans from the federal government that must be repaid at a later time, generally with interest, so that benefits may continue to be paid without interruption. California, like many other states, has used these federal loans to continue paying UI benefits after the trust fund reserve was exhausted in 2009. The state’s peak year-end balance of loans was $10.2 billion at the end of 2012. Since that time, total revenues flowing into the UI trust fund have exceeded the cost of benefits each year so that the amount of the remaining federal loans is decreasing. However, the UI trust fund remains insolvent, with a loan balance of $3.9 billion at the beginning of 2017.

Federal Loans Projected to Be Paid Off in 2018. If the Legislature takes no action to change revenues flowing in or benefits flowing out of the UI trust fund, the remaining federal loans are projected to be fully repaid sometime in 2018, primarily through a series of automatic federal tax increases described in greater detail below. This projection is based on an assumption that the state’s economy continues to experience moderate growth over the next several years. (We note that this assumption does not constitute a prediction, as periods of stagnation, recession, or even faster economic growth, are possible in future years.) Once federal loans have been fully repaid, the UI trust fund will once again have a positive reserve balance and will be solvent. In a subsequent post we will examine the extent to which the UI trust fund reserve may be sufficient to remain solvent over the long term.

Consequences of Insolvency

Federal Loans Have Resulted in General Fund Interest Payments . . . As long as a balance of federal loans remains to be repaid, the state must make annual interest payments to the federal government. While some other states that took federal loans levied surcharges on employers to pay for interest costs, California has elected to pay the interest costs from the state General Fund. The state’s interest payment for 2016 totaled $111 million. Adding this payment to previous interest payments, the state has spent a total of almost $1.4 billion in General Fund resources servicing the federal loan since the beginning of the recession. The state is estimated to make additional interest payments of $52 million in 2017 and $17 million in 2018 before the loan is projected to be fully repaid in 2018, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

General Fund Interest Payments on Federal Loans

(In Millions)

|

2011 |

$303 |

|

2012 |

308 |

|

2013 |

259 |

|

2014 |

217 |

|

2015 |

171 |

|

2016 |

111 |

|

2017 (estimated) |

52 |

|

2018 (estimated) |

17 |

|

Total |

$1,438 |

. . . And Temporarily Increased Employer Taxes. As noted above, proceeds from the federal UI tax are typically used to pay for certain costs other than state UI benefit payments, such as program administration. However, for states that have outstanding loans for a certain amount of time (between 22 and 34 months, depending on when the loans are first received), federal law requires that the effective federal UI tax rate on employers be increased by 0.3 percentage points, with the additional revenues generated from the tax increase used to pay down the loans. The effective federal UI tax rate then continues to increase by increments of 0.3 percentage points each year until the loans are fully repaid, at which point the effective federal UI tax returns to its usual rate of 0.6 percent. In effect, these federally required tax increases make it so that employers pay for UI benefit costs that were incurred during the recession that are initially covered by federal loans when the state UI trust fund has exhausted its reserves.

Because California has had federal loans since 2009, the effective federal UI tax rate paid by the state’s employers has been increasing each year since 2011, as shown in Figure 3. For tax year 2016 (payment collected in calendar year 2017), employers are estimated to collectively pay $2.2 billion in higher federal UI taxes than they would have if the rates had not increased. The annual amount of additional tax contributions is estimated to grow to $2.6 billion for tax year 2017 (payment collected in calendar year 2018). As noted above, these federal UI tax increases are temporary, and will cease once the federal loans are repaid.

Figure 3

Increased Federal UI Taxes Paid by Employers Due to Outstanding Federal Loans

(In Billions)

|

Tax Year |

Effective Increase to Federal Ratea |

Additional Revenuesb |

|

2011 |

0.3% |

$0.3 |

|

2012 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

2013 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

2014 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

|

2015 (estimated) |

1.5 |

1.7 |

|

2016 (estimated) |

1.8 |

2.2 |

|

2017 (estimated) |

2.1 |

2.6 |

|

2018 (estimated) |

— |

— |

|

Total |

$9.6 |

|

|

aReflects the increase to the federal unemployment insurance (UI) tax rate above the base rate of 0.6 percent. bAdditional revenues are collected in the calendar year following the tax year. |

||

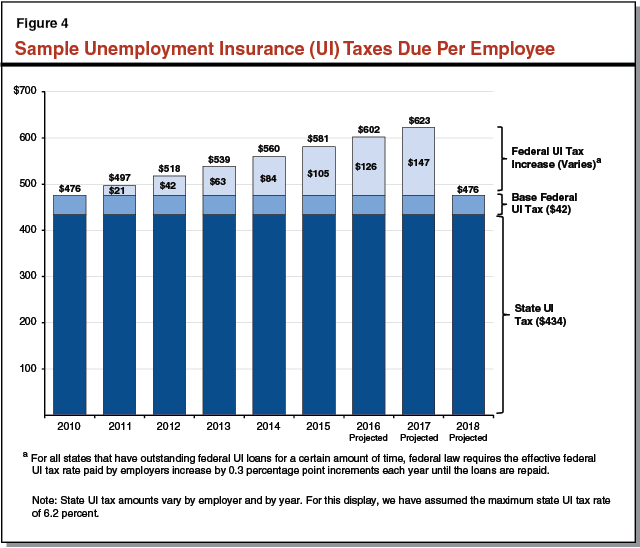

Increased Federal UI Taxes in Context. To give some context to the magnitude of increased federal UI taxes that employers are required to pay because of the trust fund insolvency, Figure 4 displays the amount of a hypothetical employer’s combined state and federal UI tax liability for an individual employee in each year the increased federal UI taxes have been or are projected to be in effect. In this figure we assume that the employer pays the maximum state UI tax rate of 6.2 percent. (For 2015, about 23 percent of employers, representing roughly 40 percent of statewide taxable wages, were assigned the maximum rate. We note that the state UI tax rate paid by an individual employer will vary from year to year.) As shown in the figure, in tax year 2017 the hypothetical employer would be required to pay $434 in state UI taxes, $42 for the base federal UI tax of 0.6 percent, plus an additional $147 in additional federal UI taxes, coming to a total of $623 for each employee. The increased federal UI taxes due for the 2017 tax year because of the outstanding federal loans represent a 31 percent increase in total UI tax liability relative to what would have been owed otherwise.

We note that, despite using the highest rate schedule, many employers do not pay the maximum state UI tax rate of 6.2 percent because of experience rating. Since the federal UI tax increases apply equally to all employers, the relative increase in total taxes due per employee will be larger for employers that pay a lower state UI tax rate. For example, for a hypothetical employer that pays a state UI tax rate of 3.1 percent, the projected increased federal UI taxes due in tax year 2017 represent a 57 percent increase in total UI tax liability relative to what would have been owed if the increased federal rates had not been in effect. (For 2015, about 24 percent of employers, representing roughly 10 percent of statewide taxable wages, were assigned a state UI tax rate of 3.1 percent or less.)

Improvement in UI Trust Fund Condition Largely the Result of Temporarily Increased Federal UI Taxes

Broadly speaking, the condition of the UI trust fund is gradually improving because of decreased benefits as the economy improves and increased revenues coming into the UI trust fund. These increased revenues are largely attributable to temporarily increased federal UI taxes. Were it not for the federal UI tax rate increases that have already been implemented, and those that are scheduled to be implemented in the next few years, the UI trust fund likely would not return to solvency in the foreseeable future, even with relatively lower total benefits being paid out in an improving economy. This is because state UI tax revenues only slightly exceed the cost of UI benefit payments, leaving little excess revenue to pay off the loans. State UI tax revenues are unlikely to increase, because the state is already using the highest rate schedule. In future posts we will examine how the condition of the UI trust fund may change after current loans are repaid, and to what extent the trust fund is prepared for the next economic downturn.