Series

Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

Update 6/13/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 May Revision.

Update 1/20/17:

Post 1 updated to reflect estimates in the 2017-18 Governor's Budget.

September 30, 2016

Revisiting the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund Insolvency

Who Pays Unemployment Insurance Taxes, and How Much?

This post is the second in a series of four posts related to California’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program. The first reviewed the current condition of the UI trust fund and how it may change in the near future. This post provides context on who pays UI taxes and how the amount paid varies. The remaining posts will assess the extent to which the UI trust fund is prepared for the next economic downturn and look at potential steps the Legislature could take should it wish to increase reserves in the trust fund as a means to address the fiscal impacts of the next economic downturn.

The other posts in this series can be accessed using the nearby menu.

Background

UI Program Assists Unemployed Workers. As described in our first post, the UI program provides weekly benefits, funded through payroll tax contributions paid by employers, to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. Weekly UI benefits are intended to replace up to 50 percent of a claimant’s prior earnings, subject to a maximum of $450 per week, for up to 26 weeks.

UI Program Is Financed Through Employer Tax Contributions. Employers pay both state and federal UI payroll taxes. State UI taxes are deposited into the state’s UI trust fund to pay for benefits to unemployed workers. Federal UI taxes are typically used to pay for certain costs other than state benefit payments, such as program administration. However, as described in our first post, federal UI taxes may be increased to pay off federal loans received by a state to pay for UI benefits when the state’s trust fund is insolvent. California employers are currently subject to increased federal UI taxes for this reason.

Federal UI Tax Is Applied Uniformly to All Employers. The federal UI tax, including any increases to repay federal loans, applies uniformly to all employers, regardless of the amount of UI benefits received by their former employees. Specifically, for tax year 2015, California employers paid 0.6 percent (the typical federal UI tax rate) plus an additional 1.5 percent (the increase to repay federal loans) on a tax base of the first $7,000 of each current employee’s wages.

State UI Tax Rates Depend on Trust Fund Condition . . . State UI tax rates also apply to a base of each current employee’s first $7,000 in annual wages, but vary by year and by employer according to a series of eight tax rate schedules laid out in state law. These schedules are used to assign a state UI tax rate to each employer based on two main factors. The first factor is the condition of the state’s UI trust fund. State law requires that rate schedules with higher rates, up to a maximum of 6.2 percent, be used when the condition of the UI trust fund is poor, so that the fund’s reserve can be replenished. (The minimum state rate is 0.1 percent.) Because the state’s trust fund is currently insolvent, the highest tax rate schedule, known as the F+ schedule, is currently in use. We note that the condition of the UI trust fund has been poor enough to require the F+ schedule since 2004.

. . . And Employer Experience. The second factor that affects the state UI tax rate assigned to employers is the employer’s “experience,” or the extent to which the employer’s former employees have received UI benefits in the past. As described in greater detail below, employers whose former employees have received relatively more UI benefits than those of other employers will, in general, be assigned a higher tax rate on the schedule. Employers whose former employees have received relatively less UI benefits than those of other employers will generally be assigned a lower rate on the schedule. This aspect of the UI financing system is known as “experience rating.”

Experience Rating Intended to Allocate UI Program Costs According to Program Use. The general intent of experience rating is to link payment for UI program costs to the likelihood that benefits will be paid, such that employers whose employees are more likely to receive UI benefits—in other words, are more likely to be laid off, as measured by the amount of past benefits received by the employer’s former employees—would pay a higher proportion of UI program costs. This linking of costs to benefits is similar in concept to other forms of insurance that charge higher premiums to individuals and organizations with a higher likelihood (risk) of using the insurance. For example, property insurance providers may charge a higher premium to an individual with a higher likelihood of incurring property damage that would result in an insurance claim. In practice, the extent to which an employer’s state UI tax rate is adjusted to reflect the risk that UI benefits will be paid is limited by statutory minimum and maximum tax rates. Accordingly, as will be more fully discussed below, the state’s UI program is not fully experience-rated.

Average UI Benefits Received and Taxes Paid Vary by Industry

As described above, state UI tax rates are assigned to employers on an individual basis and determined largely by the amount of UI benefits claimed by each employer’s former employees. As a result, assigned state UI tax rates will vary from employer to employer across the state and within each industry. Although individual employers’ tax rates vary within each industry, employers in certain industries on average tend to have higher or lower amounts of benefits received, and are assigned higher or lower state UI tax rates, than employers in other industries. Below, we examine how UI benefits received and state UI tax taxes paid vary by industry by aggregating benefits received and tax contributions paid at the industry level.

UI Benefits Relatively Concentrated in Seasonal Industries. Figure 1 shows the amount of total UI benefits claimed by former employees of a given industry as a percentage of total taxable wages in that industry. These amounts varied substantially in 2013-14, from an average of 1.6 percent in the accommodation and food services industry to an average of 11.6 percent in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing and hunting industry. Seasonality plays a significant role in the relatively high rate of UI benefit receipt in certain industries such as agriculture and construction. Workers in these industries are much more likely to be regularly out of work, leading to greater total UI benefit claims.

Figure 1

Average Unemployment Insurance (UI) Benefits Received and

State UI Tax Contributions Paid by Industry

As Percent of Taxable Wages, 2013-14

|

Industry |

Benefits |

Contributions |

|

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting |

11.6% |

5.6% |

|

Construction |

10.7 |

5.9 |

|

Information |

7.3 |

5.8 |

|

Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction |

6.4 |

5.8 |

|

Public Administration |

5.9 |

5.5 |

|

Administrative & Support and Waste Management & Remediation |

5.7 |

5.8 |

|

Utilities |

5.7 |

5.1 |

|

Finance and Insurance |

5.5 |

5.6 |

|

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

5.4 |

5.3 |

|

Manufacturing |

5.2 |

5.5 |

|

Management of Companies and Enterprises |

5.0 |

5.2 |

|

Educational Services |

4.5 |

5.2 |

|

Wholesale Trade |

4.4 |

5.4 |

|

Real Estate and Rental & Leasing |

4.3 |

5.4 |

|

Transportation and Warehousing |

4.3 |

5.2 |

|

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation |

4.1 |

5.2 |

|

Other Services (except Public Administration) |

3.1 |

5.0 |

|

Health Care and Social Assistance |

2.8 |

5.1 |

|

Retail Trade |

2.5 |

4.9 |

|

Accommodation and Food Services |

1.6 |

4.5 |

|

Note: Industry categories from the North American Industry Classification System are used in this figure. |

||

Average State UI Taxes Paid Also Vary by Industry, but Relatively Less Than Variation in Average Benefits Received. Figure 1 shows—by aggregating data for employers on an industry-by-industry basis—that the average state UI taxes paid by employers in different industries also varied in 2013-14. The extent of the variation in taxes paid, however, is markedly less than the extent of variation in benefits received. This results in a mismatch between industry averages for benefits received and taxes paid. As discussed below, this is because the state’s experience rating system does not fully account for differences in the benefits received by former employees when setting an employer’s tax rate.

Incomplete Experience Rating Results in Sharing of Excess Benefit Costs

Employer Contribution Rates Are Capped. California, like other states, puts a ceiling and a floor on the state UI tax rate that employers may be assigned. As described above, California’s top rate is 6.2 percent and the minimum rate is 0.1 percent. Consistent with experience rating, the greater the amount of UI benefits claimed by an employer’s former employees, the higher the employer’s state UI tax rate, up to the statutory maximum. Once the maximum rate is reached, it cannot be increased further, regardless of how much UI benefits paid to former employees exceed the employer’s tax contributions. This results in “incomplete” experience rating, where the likelihood of future benefit payments (as measured by past payments) is not fully reflected in an employer’s assigned tax rate. For example, an average employer in the construction industry whose former employees receive UI benefits equal to about 11 percent of the employer’s taxable wages would not pay more than 6.2 percent of taxable wages in state UI tax contributions.

Some Employers Effectively Subsidize Benefits Paid to Other Employers’ Former Employees. When an employer imposes benefit costs that exceed the UI taxes it pays, the state’s UI program is set up such that these excess benefits costs are shared by a broad group of other employers. It accomplishes this by assigning a higher tax rate to relatively low-cost employers than is necessary to cover the benefit costs of those employers’ former employees. This sharing of excess benefit costs results in a cross-subsidy, relative to a fully experience-rated system, where the state UI tax contributions of lower-cost employers are used to pay for a portion of UI benefits claimed by former employees of employers who already pay the maximum state UI tax rate. Because UI benefits received and state UI tax rates assigned vary among employers within industries, each industry has employers that are assigned a state UI tax rate that exceeds what is necessary to cover the costs of benefits received by their former employees (that is, they provide a subsidy) and other employers that are assigned a state UI tax rate that does not cover the cost of benefits received by their former employees (that is, they receive a subsidy). However, because benefits received and tax contributions paid tend to be higher or lower in some industries than in others on average, we examine the amount of cross-subsidies at the industry level.

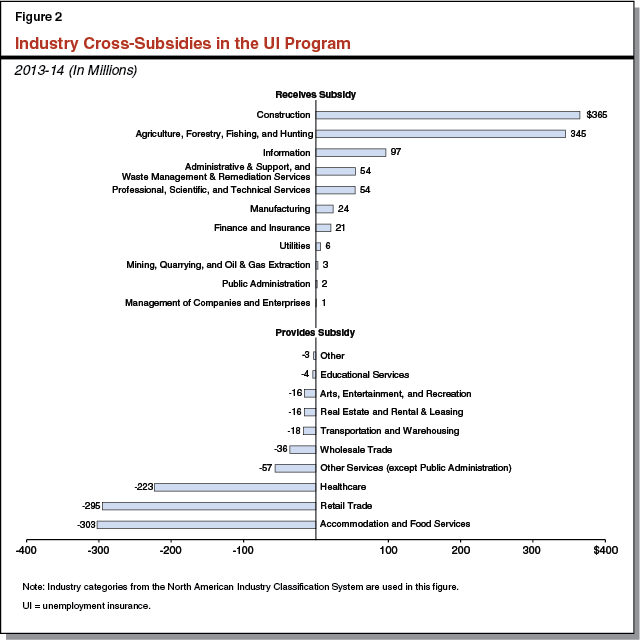

Figure 2 roughly estimates the amount of industry-level cross-subsidies provided and received in 2013-14 by calculating the difference in industry UI tax contributions that would have been paid if each industry’s aggregate contributions had been proportional to the amount of aggregate UI benefits claimed by former employees in that industry. As shown in the figure, the construction industry and the agricultural, forestry, and fishing and hunting industries received the most significant subsidies, meaning that these industries’ share of total state UI tax contributions would have been much greater if excess benefit costs were not shared by employers broadly—that is, if the aggregate contributions had been collected in proportion to aggregate benefits received. The accommodation and food services and retail trade industries provided the most significant subsidies, meaning that these industries’ share of total state UI tax contributions would have been much smaller if excess benefit costs were not shared. The magnitude of these subsidies is significant. As an example, if state UI taxes had been collected in proportion to benefits received in 2013-14, the state UI contributions paid by the retail trade industry would have been reduced by 44 percent.

Incomplete Experience Rating and Sharing of Excess Benefit Costs Are Common in State UI Systems. We note that the incomplete experience rating in California’s UI program reflects a policy choice to limit the extent to which employers with high turnover pay for the resulting UI benefit costs by requiring employers with lower turnover to pay for a portion of these costs. As mentioned previously, all states have a cap on the maximum state UI tax rate (set at various levels), such that all state UI programs feature incomplete experience rating in which certain employers subsidize the UI benefit costs of other employers’ former employees to some extent.

Using Federal UI Tax to Finance Benefits Increases Sharing of Benefit Costs

As noted previously, California employers are currently subject to increased federal UI taxes, the proceeds of which go to repay federal loans that have been taken by the state to continue the payment of UI benefits after the UI trust fund exhausted its reserve in 2009. In effect, employers are paying for the cost of past benefits received during the last recession while continuing to pay the cost of UI benefits that are being claimed currently. Hypothetically, if the state UI tax had been able to generate sufficient revenues to cover benefits through the last recession using the current experience-rated state UI tax, the current increases to the federal UI tax would not be in effect. Because the increased federal UI taxes apply equally to all employers regardless of experience, they reduce further the system’s overall reliance on experience rating. This outcome can be viewed as a positive or a negative depending on the Legislature’s policy goals for experience rating and the desired level of cross-subsidies in the UI program.