LAO Contact

- Managing Principal Analyst,

- Criminal Justice

- Judicial Branch, Department of Justice,

- State Penalty Fund

- Prisons, Firecamps

- Parole, Rehabilitation,

- Inmate Health Care

February 27, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Governor's Criminal Justice Proposals

- Criminal Justice Budget Overview

- Cross Cutting Issue: State Penalty Fund

- California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Judicial Branch

- California Department of Justice

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overview. The Governor’s budget proposes a total of $17.2 billion from various fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs in 2018‑19. This is an increase of $302 million, or 2 percent, above estimated expenditures for the current year. The budget includes General Fund support for judicial and criminal justice programs of $13.9 billion in 2018‑19, which is an increase of $270 million, or 2 percent, over the current‑year level. In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the judicial and criminal justice area and recommend various changes. Below, we summarize our major recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of the report.

Accommodating Proposition 57 Inmate Population Reductions. In response to the decline in the inmate population resulting from Proposition 57 (2016), the Governor proposes to remove inmates from the two out‑of‑state prison facilities and place them in a prison operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). We recommend that the Legislature instead consider directing CDCR to close the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) in Norco and remove inmates from one of the two out‑of‑state facilities. If the Legislature decides to close CRC, we recommend directing the department to provide a detailed closure plan. If the Legislature decides not to close CRC, CDCR should provide a plan for making the necessary infrastructure improvements at the prison.

Ventura Training Facility. The proposed budget provides a total of $9 million from the General Fund to CDCR, the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, and the California Conservation Corps to create a new firefighter training program for 80 parolees. According to the administration, the primary purpose of the proposal is to reduce parolee recidivism. We recommend rejection of the proposal because there is little evidence that the plan would be a cost‑effective way to achieve the stated goal. Instead, to the extent that the Legislature wanted to prioritize recidivism reduction programs, there are likely to be evidence‑based programs that could serve many more individuals and at a lower cost than under the Governor’s proposal.

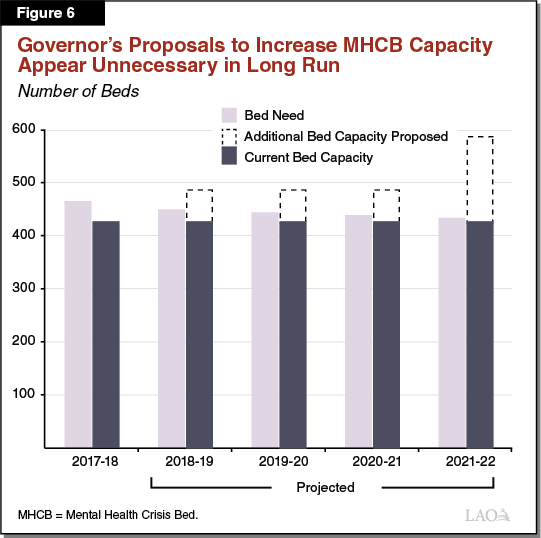

Inmate Mental Health Programs. We make several recommendations on the Governor’s proposals to increase the number of Mental Health Crisis Beds (MHCBs) and improve CDCR’s overall management of mental health beds. First, we recommend the Legislature provide limited‑term funding (rather than ongoing funding as proposed by the Governor) for CDCR to convert 60 existing mental health beds into “flex beds” to potentially use as MHCBs, as the need for MHCBs appears to be temporary. Second, we recommend the Legislature reject the working drawings funding proposed for two MHCB facility projects as current projections suggest that they would not be needed by the time they are in operation. Third, we recommend rejecting the proposed resources for CDCR to take over the mental health projections currently done by a private contractor. Finally, we recommend the Legislature approve the requested staff resources to help CDCR meet court‑approved guidelines for transferring patients to mental health beds.

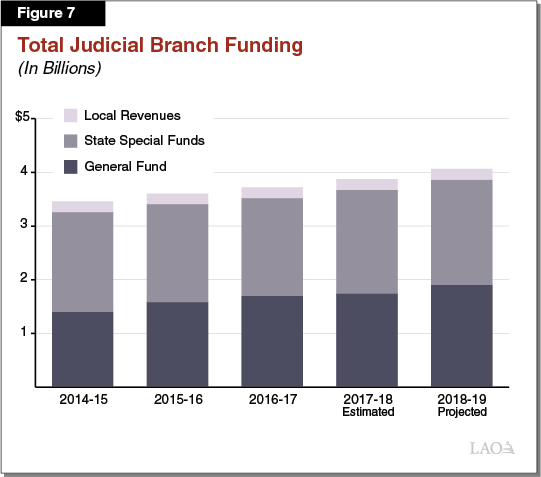

Trial Court Funding Augmentations. The Governor’s budget includes $123 million to increase general purpose funding for trial court operations—$75 million allocated based on the Judicial Council’s priorities and $47.8 million for certain trial courts that are comparatively less well‑funded than other courts. In evaluating the Governor’s proposals, we recommend that the Legislature (1) consider the level of funding it wants to provide relative to its other General Fund priorities and (2) allocate any additional funds provided based on its priorities—rather than allowing the Judicial Council to do so. Additionally, given the uncertainty around whether the Judicial Council’s current workload‑based funding methodology accurately estimates trial court needs, we also recommend the Legislature convene a working group to evaluate the methodology.

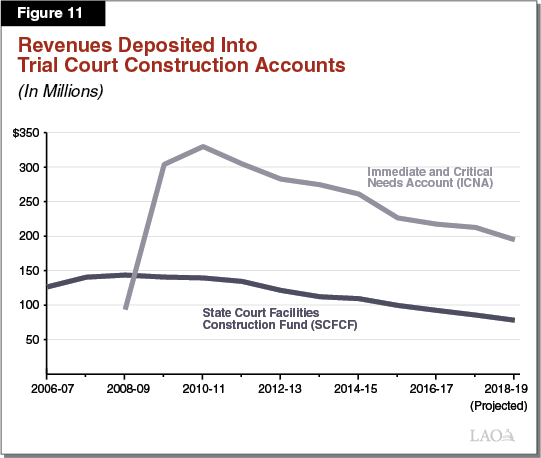

Trial Court Construction Projects. The Governor’s budget proposes to use lease revenue bonds backed from the General Fund—rather than an existing court construction account—to finance the construction of ten trial court projects that are currently on hold or have been indefinitely delayed due to a lack of revenue in the account. We find that this approach does not address key underlying problems with the state’s current trial court construction program, such as a lack of resources to pay existing debt service for court construction projects already completed. To address these problems, we recommend that the Legislature eliminate the state’s two construction accounts, shift responsibility for funding trial construction projects to the General Fund, and increase legislative oversight of funded projects. This would help ensure that those projects that are legislative priorities and have the greatest needs are funded, rather than being constrained by existing declining revenue sources. To the extent the Legislature would like to maintain the existing court construction system, we recommend modifying the Governor’s proposal to address some of the concerns we raise.

Criminal Justice Budget Overview

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating criminals back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and the California Department of Justice (DOJ). The Governor’s budget for 2018‑19 proposes total expenditures of $17.2 billion for judicial and criminal justice programs. Below, we describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice and provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2018‑19.

State Expenditure Trends

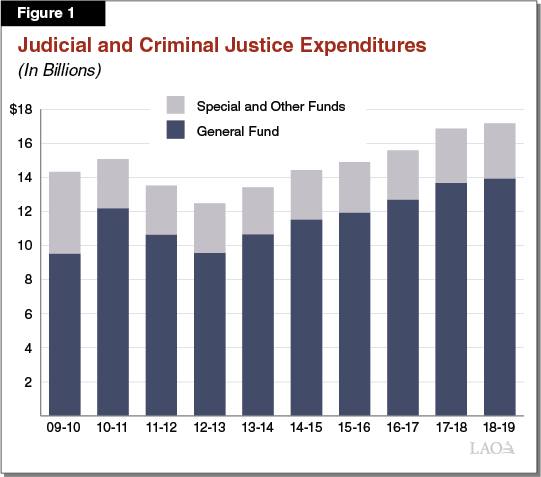

Total Spending Declined Between 2010‑11 and 2012‑13 . . . Over the past decade, total state expenditures on criminal justice programs has varied. As shown in Figure 1, criminal justice spending declined between 2010‑11 and 2012‑13, primarily due to two factors. First, in 2011 the state realigned various criminal justice responsibilities to the counties, including the responsibility for certain low‑level felony offenders. This realignment reduced state correctional spending. Second, the judicial branch—particularly the trial courts—received significant one‑time and ongoing General Fund reductions.

. . . But Has Increased Since Then. Since 2012‑13, overall spending on criminal justice programs has steadily increased. This was largely due to additional funding for CDCR and the trial courts. For example, increased CDCR expenditures resulted from (1) increases in employee compensation costs, (2) the activation of a new health care facility, and (3) costs associated with increasing capacity to reduce prison overcrowding. During this same time period, various augmentations were provided to the trial courts to offset reductions made in prior years and fund specific activities.

Governor’s Budget Proposals

Total Proposed Spending of $17.2 Billion in 2018‑19. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s 2018‑19 budget includes a total of $17.2 billion from all fund sources for judicial and criminal justice programs. This is an increase of $302 million (2 percent) over the revised 2017‑18 level of spending. General Fund spending is proposed to be $13.9 billion in 2018‑19, which represents an increase of $270 million (2 percent) above the revised 2017‑18 level. We note that this increase does not include increases in 2018‑19 employee compensation costs for these departments, which are budgeted elsewhere. If these cost were included, the increase would be somewhat higher.

Figure 2

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Actual |

Estimated |

Proposed |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Actual |

Percent |

||||

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation |

$10,889 |

$11,849 |

$11,975 |

$125 |

1.1% |

|

General Funda |

10,592 |

11,540 |

11,661 |

121 |

1.1 |

|

Special and other funds |

297 |

309 |

313 |

4 |

1.3 |

|

Judicial Branch |

$3,522 |

$3,675 |

$3,864 |

$188 |

5.1% |

|

General Fund |

1,702 |

1,748 |

1,907 |

158 |

9.1 |

|

Special and other funds |

1,821 |

1,927 |

1,957 |

30 |

1.6 |

|

Department of Justice |

$745 |

$927 |

$926 |

‑$1 |

‑0.1% |

|

General Fund |

219 |

238 |

245 |

7 |

2.8 |

|

Special and other funds |

526 |

689 |

681 |

‑8 |

‑1.1 |

|

Board of State and Community Corrections |

$201 |

$162 |

$155 |

‑$7 |

‑4.4% |

|

General Fund |

108 |

67 |

49 |

‑18 |

‑26.9 |

|

Special and other funds |

93 |

94 |

105 |

11 |

11.6 |

|

Other Departmentsb |

$225 |

$241 |

$237 |

‑$4 |

‑1.6% |

|

General Fund |

80 |

71 |

72 |

1 |

1.9 |

|

Special and other funds |

145 |

170 |

165 |

‑5 |

‑3.1 |

|

Totals, All Departments |

$15,583 |

$16,854 |

$17,156 |

$302 |

1.8% |

|

General Fund |

12,701 |

13,664 |

13,934 |

270 |

2.0 |

|

Special and other funds |

2,882 |

3,189 |

3,222 |

32 |

1.0 |

|

aDoes not include revenues to General Fund to offset corrections spending from the federal State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. bIncludes Office of the Inspector General, Commission on Judicial Performance, Victim Compensation Board, Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, State Public Defender, funds provided for trial court security, and debt service on general obligation bonds. Note: Detail may not total due to rounding. |

|||||

Major Budget Proposals. The most significant piece of new spending included in the Governor’s budget relates to various proposals to increase General Fund support for trial courts by a total of $210 million, including $75 million to support Judicial Council priorities and $48 million to equalize funding across trial courts. In addition, the budget includes various augmentations for other departments. For example, the Governor’s budget proposes a total of $136 million for infrastructure and equipment at CDCR, including $61 million to replace roofs at three prison facilities, $33 million to replace public safety radio communication systems, and $20 million to repair damage from leaking roofs.

Cross Cutting Issue: State Penalty Fund

LAO Bottom Line. The Governor’s proposed expenditure plan for the State Penalty Fund (SPF) generally is consistent with the 2017‑18 plan. We recommend, however, that the Legislature review the plan to make sure it reflects its priorities and modify as necessary. As we have indicated in recent years, long‑term solutions are needed to the overall assessment, collection, and distribution of fine and fee revenue to address the ongoing structural problems with the state’s current fine and fee system.

Background

Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue Supports Numerous State and Local Programs. During court proceedings, trial courts typically levy fines and fees upon individuals convicted of criminal offenses (including traffic violations). When such fines and fees are collected, state law (and county board of supervisor resolutions for certain local charges) dictates a very complex process for the distribution of fine and fee revenue to numerous state and local funds. These funds in turn support numerous state and local programs. For example, such revenue is deposited into the SPF for the support of various programs including training for local law enforcement and victim assistance. State law requires that collected revenue be distributed in a particular priority order, allows distributions to vary by criminal offense or by county, and includes formulas for distributions of certain fines and fees. (For more information about how criminal fines and fees are assessed and distributed, please see our January 2016 report, Improving California’s Criminal Fine and Fee System.) A total of about $1.7 billion in fine and fee revenue was distributed to state and local funds in 2015‑16. Of this amount, the state received roughly one‑half.

Various Actions Taken in Recent Years to Address Declining Criminal Fine and Fee Revenue. The total amount of fine and fee revenue distributed to state and local governments has declined since 2010‑11. As a result, a number of state funds receiving such revenue, including the SPF, have been in operational shortfall for years—meaning annual expenditures exceed annual revenues—and some have become insolvent. Over the past few years, the state has adopted a number of one‑time and ongoing solutions to address the shortfalls or insolvency facing some of these funds:

- Eliminating SPF Distribution Formulas. As part of the 2017‑18 budget, the state eliminated existing statutory provisions dictating how revenues deposited into the SPF are distributed to nine other state funds. Instead, specific dollar amounts are now appropriated directly to specific programs in the annual budget based on state priorities.

- Shifting Costs. In recent years, the state has shifted costs from various funds supported by fine and fee revenue to the General Fund or other funds. Most of these cost shifts were either on a one‑time or temporary basis. For example, nearly $16.5 million in costs were shifted from the Peace Officers Training Fund to the General Fund in 2016‑17. More recently, the state authorized DOJ to effectively shift $15 million in costs from the DNA Identification Fund in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 to two other special funds. However, one such cost shift—specifically the General Fund backfill of the Trial Court Trust Fund, which supports trial court operations—has been provided continuously since 2014‑15.

- Reducing Expenditures. The state has also directed certain departments to reduce expenditures from fine and fee revenue. For example, the Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST), which receives such revenue to support training for law enforcement, was required to reduce expenditures. In response, the commission took several actions, such as suspending or reducing certain training reimbursements and postponing some workshops. Similarly, as we discuss in more detail later in this report, the reduction in fine and fee revenues has halted certain trial court construction projects.

- Increasing Revenue. The state has also attempted to increase the amount of fine and fee revenue collected in different ways. For example, the 2017‑18 budget provided one‑time and ongoing resources for the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) to increase its fine and fee revenue collection activities. (Currently, court and county collection programs can collect fine and fee revenue themselves, as well as contract with FTB or private entities.)

Governor’s Proposal

SPF Expenditure Plan. The Governor’s budget projects that about $81 million in criminal fine and fee revenue will be deposited into the SPF in 2018‑19—a decline of $12.6 million (or 13.5 percent) from the revised current‑year estimate. (We note that revenue deposited into the SPF has steadily declined since 2008‑09 and will have declined by 53 percent by 2018‑19.) Of this amount, the administration proposes to allocate $79.5 million to eight different programs in 2018‑19—all of which received SPF funds in the current year. As shown in Figure 3, many of these programs are also supported by other fund sources. Under the Governor’s plan, five of the eight programs would receive less SPF support compared to the estimated 2017‑18 level. For some of these programs (such as the Victim Compensation Program), funding from other sources are proposed to partially offset the reduction in SPF support. Additionally, the Governor proposes to shift SPF support for the Bus Driving Training Program to the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA). (The MVA supports the state administration and enforcement of laws regulating the operation and registration of vehicles used on public streets and highways.) Finally, we note that the Governor’s budget does not include funding for two programs—the California Violence Intervention and Prevention Grant Program (CalVIP) and Internet Crimes Against Children Program—that received General Fund support in 2017‑18 to backfill on a one‑time basis the elimination of SPF support for these programs.

Figure 3

Governor’s Proposed State Penalty Fund (SPF) Expenditures for 2018‑19

(In Thousands)

|

Program |

2017‑18 (Estimated) |

2018‑19 (Proposed) |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||||||

|

SPF |

Other Funds |

Total |

SPF |

Other Funds |

Total |

Total |

|||

|

Victim Compensation |

$9,100 |

$103,656 |

$112,756 |

$6,534 |

$105,867 |

$112,401 |

‑$355 |

||

|

Various OES Victim Programsa |

11,834 |

73,377 |

85,211 |

8,984 |

63,649 |

72,633 |

‑12,578 |

||

|

Peace Officer Standards and Training |

47,241 |

5,287 |

52,528 |

43,835 |

1,959 |

45,794 |

‑6,734 |

||

|

Standards and Training for Corrections |

17,304 |

100 |

17,404 |

15,998 |

100 |

16,098 |

‑1,306 |

||

|

CalWRAP |

3,277 |

— |

3,277 |

2,478 |

— |

2,478 |

‑799 |

||

|

DFW employee education and training |

450 |

2,628 |

3,078 |

450 |

2,536 |

2,986 |

‑92 |

||

|

Bus Driver Training |

895 |

494 |

1,389 |

— |

1,447 |

1,447 |

58 |

||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

800 |

314 |

1,114 |

800 |

92 |

892 |

‑222 |

||

|

Local Public Prosecutors and Public Defenders Training |

450 |

— |

450 |

450 |

— |

450 |

— |

||

|

Totals |

$91,351 |

$185,856 |

$277,207 |

$79,529 |

$175,650 |

$255,179 |

‑$22,028 |

||

|

aIncludes Victim Witness Assistance Program, Victim Information and Notification Everyday Program, Rape Crisis Program, Homeless Youth and Exploitation Program, and Child Sex Abuse Treatment Program. OES = Office of Emergency Services; CalWRAP = California Witness Relocation and Assistance Program; and DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

|||||||||

LAO Assessment

Proposal Generally Consistent With Prior Year. The Governor’s proposed SPF expenditure plan reflects priorities that are generally consistent with the expenditure plan for 2017‑18. Specifically, the proposed plan does not eliminate SPF support for any programs which received such support in 2017‑18 except the Bus Driver Training Program which would be supported by the MVA instead. Additionally, similar to 2017‑18, reductions in SPF support for certain programs (such as for victim compensation) will be offset by increased expenditures from other funds.

Unclear What Impact Proposed Reductions Will Have. The Governor’s proposed expenditure plan does not specify how the programs would accommodate the proposed funding reductions. Rather, the reductions are unallocated and the programs would be given flexibility in how such reductions will be implemented. For example, it is unknown at this time how POST will accommodate its reductions. Accordingly, the programmatic impact of the proposed reductions is unknown.

Legislature May Have Different Priorities. While the Governor’s proposal reflects the administration’s funding priorities, it is likely that the Legislature has different priorities. The Legislature could decide that programs should implement different levels of expenditure reductions. For example, the Legislature could make greater reductions for peace officer or corrections standards and training in order to make funding available to support CalVIP. In addition, the Legislature may want to specify how certain departments implement their reductions in order to ensure that their choices are consistent with legislative priorities.

Structural Problems With Criminal Fine and Fee System Still Remain. The Governor’s proposal does not provide a long‑term solution to address the structural problems of the state’s criminal fine and fee system. As noted above, the amount of criminal fine and fee revenue distributed into state and local funds—such as the SPF—continues to decline. The elimination of formulas dictating SPF allocations in 2017‑18 increased the Legislature’s control over the use of the revenue and allowed the Legislature to allocate funding based on its priorities. However, numerous other distribution formulas remain—thereby making it difficult for the Legislature to make year‑to‑year adjustments in spending. Additionally, the level of funding allocated to programs, including those supported by the SPF, still relies on the amount of criminal fine and fee revenue that is available rather than on workload or service level needs. This means that programs that are supported by such revenue, which can fluctuate depending on factors outside of the Legislature’s control (such as the number of citations issued and individuals’ willingness to pay), will continue to be disproportionately impacted compared to programs that are not supported by this type of revenue. Finally, to the extent that revenue continues to decline, the Legislature will be required to continue to take action to address the operational shortfalls and insolvencies of funds supported by such revenue.

LAO Recommendations

Ensure SPF Expenditure Plan Reflects Legislative Priorities. Although the Governor’s proposed SPF expenditure plan is generally consistent with the 2017‑18 plan, the Legislature will want to review it to make sure the plan reflects its priorities—particularly given the projected reduction in SPF revenues—and make any necessary adjustments. We recommend the Legislature direct the entities that administer the programs to take specific actions in implementing any reduction in SPF support, in order to ensure that legislative priorities are maintained. For example, the Legislature could require that entities maintain certain types of training provided to local agencies.

Consider Changing Overall Distribution of Fine and Fee Revenue. As we have indicated in recent years, a broader, long‑term approach to changing the overall distribution of fine and fee revenue is needed to address the ongoing structural problems with the current system. As initially discussed in our January 2016 report, we continue to recommend that the Legislature (1) eliminate all statutory formulas related to fines and fees and (2) require the deposit of nearly all such revenue, except those subject to legal restrictions, into the General Fund for subsequent appropriation in the annual state budget. This would allow the Legislature to maximize control over the use of such revenue and ensure that state and local programs it deems to be priorities are provided the level of funding necessary to meet desired workload and service levels. This would also eliminate the need for the Legislature to continuously identify and implement short‑term solutions to address various other such funds supported by this revenue that are currently facing or nearing structural shortfalls or insolvency.

Consider Other Long‑Term Solutions to Address Structural Problems. In recent years, we have also identified various key weaknesses and problems with the state’s assessment, collection, and distribution of criminal fine and fee revenue, such as a lack of clear fiscal incentives for collection programs to collect debt in a cost‑effective manner that maximized the amount collected. To address these deficiencies, we provided a number of recommendations to overhaul and improve the system. For example, we recommended piloting a new collections model to address the lack of clear incentives for collection programs to collect debt in a cost‑effective manner, as well as consolidating most fines and fees to address the challenges of distributing revenues accurately. (For more information on our findings and recommendations, please see our January 2016 report, as well as our November 2014 report, Restructuring the Court‑Ordered Debt Collection Process.)

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Overview

The CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of January 10, 2018, CDCR housed about 130,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 35 prisons and 43 conservation camps. About 8,000 inmates are housed in either in‑state or out‑of‑state contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 46,000 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit parole violations. In addition, 620 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

Spending Proposed to Increase by $125 Million in 2018‑19. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $12 billion ($11.7 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2018‑19. Figure 4 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the past and current years and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $125 million, or about 1 percent, from the estimated 2017‑18 spending level. This increase reflects additional funding to (1) replace roofs and address mold damage at various prisons, (2) replace radio communication systems, and (3) pay the debt service for construction projects. This additional proposed spending is partially offset by various spending reductions, including reduced spending for contract beds. (The proposed $125 million increase does not include anticipated increases in employee compensation costs in 2018‑19.)

Figure 4

Total Expenditures for the California Department of

Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Prisons |

$9,646 |

$10,477 |

$10,522 |

$45 |

— |

|

Adult parole |

548 |

620 |

654 |

34 |

5% |

|

Administration |

467 |

504 |

548 |

44 |

9 |

|

Juvenile institutions |

183 |

197 |

201 |

4 |

2 |

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

45 |

50 |

50 |

‑1 |

‑2 |

|

Totals |

$10,889 |

$11,849 |

$11,975 |

$125 |

1% |

Trends in the Adult Inmate and Parolee Populations

LAO Bottom Line. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision.

Background

As shown in Figure 5, the average daily inmate population is projected to be 127,400 inmates in 2018‑19, a decrease of about 2,900 inmates (2 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. Also shown in Figure 5, the average daily parolee population is projected to be 49,800 in 2018‑19, an increase of about 2,800 parolees (6 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The projected decrease in the inmate population and increase in the parolee population is primarily due to the estimated impact of Proposition 57 (2016), which made certain nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration and expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ prison terms through credits.

Governor’s Proposal

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the inmate and parolee populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole).

The administration proposes a net increase of $39.5 million in the current year and a net increase of $38.3 million in the budget year for adult population‑related proposals. The current‑year net increase in costs is primarily due to a smaller than anticipated reduction in the use of contract beds, as well as increases in the number of inmates housed in state‑operated prisons and spending on inmate medical care relative to what was assumed in the 2017‑18 Budget Act. This increase in cost is partially offset by projected savings—such as from the cancellation of a planned expansion of the Male Community Reentry Program to San Francisco. The budget‑year net increase in costs is primarily due to a projected increase in the parolee population as a result of Proposition 57 and the activation of additional administrative segregation and mental health housing units. These increased costs are partially offset by savings—such as from a decrease in the use of contract beds.

LAO Recommendation

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision.

Accommodating Inmate Population Reductions Resulting From Proposition 57

LAO Bottom Line. In order to accommodate the anticipated decline in the inmate population due to Proposition 57, we recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to close the California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) in Norco and remove inmates from the contract facility in Mississippi—rather than closing all out‑of‑state contract facilities as proposed by the Governor. If the Legislature decides to close CRC, we recommend directing CDCR to provide a detailed plan on the closure. If the Legislature decides not to close CRC, CDCR should provide it with a plan for making the necessary infrastructure improvements at the prison.

Background

Federal Court Orders Prison Population Cap. In recent years, the state has been under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in the 34 state prisons operated by CDCR. Specifically, the court found that prison overcrowding was the primary reason the state was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care and ordered the state to reduce the population of the 34 prisons to below 137.5 percent of their design capacity. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms.) The court also appointed a compliance officer. If the prison population exceeds the population cap at any point in time, the compliance officer is authorized to order the release of the number of inmates required to meet the cap. To ensure that such releases do not occur if the prison population increases unexpectedly, CDCR houses about 2,000 fewer inmates than is allowed under the cap as a “buffer.”

Various Changes Have Allowed State to Comply With Population Cap. In order to comply with the court order, the state has taken a number of actions in recent years. These actions include (1) housing inmates in contract prison facilities (discussed in greater detail below), (2) constructing additional prison capacity, and (3) reducing the inmate population by implementing several policy changes, such as the 2011 realignment, which required that certain lower‑level felons serve their incarceration terms in county jail rather than state prison.

Contract Prisons Currently Used to Avoid Exceeding Population Cap. CDCR relies on contract facilities to maintain compliance with the court order. As of January 10, 2018, CDCR housed about 4,300 inmates in two out‑of‑state contract facilities—about 1,300 inmates in Tutwiler, Mississippi and about 3,000 inmates in Eloy, Arizona. CDCR also housed about 4,100 inmates in several contract facilities located in California.

Inmate Population Projected to Decline Due to Proposition 57. Approved by the voters in November 2016, Proposition 57 (1) made certain nonviolent offenders eligible to be considered for release after serving a portion of their sentence, (2) expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ prison terms through credits earned for good behavior and participation in rehabilitation programs, and (3) required that judges decide whether juveniles should be tried in adult court. The administration expects these changes to reduce the average daily inmate population by about 2,900 in 2018‑19, growing to a roughly 5,000 inmate reduction by 2020‑21 relative to its current level. (For more information on the implementation of Proposition 57, please see our report, The 2017‑18 Budget: Implementation of Proposition 57.)

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor proposes to accommodate the anticipated decline in the inmate population due to Proposition 57 by removing inmates from the contract facility in Mississippi by June 2018 and from the Arizona facility by fall 2019. These inmates would be moved to CDCR‑operated prisons to fill beds that are vacated as the overall population declines. Accordingly, the proposed budget includes a $68 million reduction in spending on out‑of‑state contract facilities in 2018‑19 relative to the revised 2017‑18 level.

LAO Assessment

Alternative to Closing All Out‑of‑State Contract Facilities Is to Close a State Prison. We agree with the administration that CDCR is likely to experience a decline of roughly 5,000 inmates over the next few years. The Governor proposes to accommodate this population decline by closing all out‑of‑state contract facilities. The estimated inmate decline, however, presents the Legislature with the opportunity to consider alternative ways to accommodate the population reductions caused by Proposition 57 that could result in a greater reduction in state costs and still keep a buffer of about 2,000 inmates below the cap. Specifically, the state could instead close a state prison since California’s prisons typically house between 2,000 and 5,000 inmates—a similar magnitude to the population reductions expected as a result of Proposition 57.

Possible Prison to Close Is CRC Due to Its Costly Repair Needs. In 2012, the administration’s plan for reorganizing CDCR following the 2011 realignment of adult offenders called for the closure of CRC by 2015, due to its age and deteriorating infrastructure. At the time, CDCR estimated that fully addressing all of the facility’s maintenance needs could cost over $100 million. However, the facility remained open because the administration later determined that CRC’s capacity was needed to comply with the population cap. (CRC has a design capacity of about 2,500—allowing the state to house 3,400 inmates at the overcrowding limit of 137.5 percent—and currently houses about 2,600 inmates.)

As part of the 2015‑16 Budget Act, the Legislature required the administration to provide an updated comprehensive plan for the state prison system, including a permanent solution to the decaying infrastructure at CRC. The administration’s plan stated that closing CRC is a priority but that the capacity will be needed for the next few years in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap. While the 2016‑17 budget included $6 million for special repairs at CRC to address some of the prison’s most critical infrastructure needs (such as improvements to electrical and plumbing systems), the administration has not presented a plan for the significant improvements that are still necessary, including health care facility improvements that have been made at other prisons at the request of the federal Receiver.

Closing CRC and Removing Fewer Inmates From Contract Facilities Could Result in Significant Savings. Given the expected decline in the inmate population as a result of Proposition 57, we estimate that the state could close CRC and still make a significant reduction in out‑of‑state contract beds by closing the Mississippi contract facility. (The state would need to maintain the Arizona contract.) We estimate that closing CRC and the Mississippi contract facility would eventually result in ongoing net savings of roughly $100 million annually relative to the Governor’s plan. This is because the department saves about $30,000 annually per inmate removed from a contract facility while it saves roughly $70,000 annually per inmate when it closes a state prison. (The higher per inmate costs of state‑run facilities are due to a variety of factors including contractors’ lower employee compensation costs and CDCR’s practice of not putting inmates with high health care needs—who are relatively expensive—into contract facilities.) Moreover, if the state closed CRC, it would avoid the cost of renovating the prison and constructing updated medical facilities. Currently, CDCR estimates it would require over $200 million to fully address the infrastructure needs at CRC, though it is not clear when this cost would be incurred.

We note that it would likely take at least a year before CRC could be closed. As such, the above savings would likely not be realized until at least 2019‑20 or later. In addition, it is possible that closing CRC could actually increase costs somewhat relative to the Governor’s proposal during the period when CRC is being closed. This is because until CRC is fully closed, the department would experience less savings from removing inmates from CRC than from contract facilities. The precise fiscal effect of closing CRC in the short term is unknown and would depend primarily on (1) how the court adjusts the prison population cap during the time that CRC is being shut down and (2) how quickly the department is able to achieve operational savings at CRC as it reduces the prison’s population. However, we estimate that this short‑term reduction in savings relative to the Governor’s plan would be unlikely to exceed the low tens of millions for a couple of years.

LAO Recommendation

In view of the significant ongoing savings that could result from closing CRC rather than the Arizona contract facility, we recommend that the Legislature consider directing CDCR to close CRC. If the Legislature decides to close CRC, we recommend requiring CDCR to provide a detailed plan on the closure. If the Legislature decides not to close CRC, CDCR should provide a plan for making the necessary infrastructure improvements at the prison.

Parole Staffing Proposals

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend the department utilize a budgeting methodology that is based on specific staffing ratios, as well as takes into account the size and composition of the parolee population, to annually adjust the total number and type of positions needed each year to operate the state’s parole system—not just for direct‑supervision positions as is currently the case. We recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to report at budget hearings on a timeline for incorporating support staff into its annual staffing adjustments. Pending such a report from the department and the availability of updated parolee projections that could change the level of positions needed, we withhold recommendation on the proposed staffing requests until the May Revision.

Background

Parolees Receive Different Levels of Supervision Based on Classification. CDCR’s Division of Adult Parole Operations (DAPO) classifies parolees into different classifications depending on the level of supervision they require, which is based on various factors such as their criminal history. As a result, the caseload of a parole agent primarily depends on the classification of the parolees supervised by the agent. For example, parole agents who supervise general felons typically have a caseload of around 55 parolees, while parole agents who supervise high‑risk sex offenders have a caseload of around 20 parolees.

Direct‑Supervision Positions Are Annually Adjusted Based on Parolee Population. For most types of direct‑supervision positions (such as parole agents and their supervisors), the department annually requests the level of funding and positions required to ensure that each classification of parolees receives appropriate levels of supervision, rehabilitation programs, and mental health treatment. The level requested is based on a budgeting methodology that utilizes specific staffing ratios and takes into account the size and composition of the parolee population. An increase in the parolee population would require additional positions and funding, and a decline in the population would result in a need for less resources compared to the previous year. For example, if the number of high‑risk sex offender parolees is estimated to increase by 20, the staffing ratios would indicate that one additional parole agent is needed for the coming year. Increases in the number of parole agents in turn result in the need for other positions based on certain ratios—such as one additional supervisor for every eight additional parole agents. Increases in the parolee population also generate the need for operating expenses and equipment, such as a GPS monitoring device that each additional high‑risk sex offender parolee is required to wear.

Support Positions Not Annually Adjusted Based on Parolee Population. In order to assist the work that parole agents do in the field, DAPO employs various support positions that do not involve the direct supervision of parolees—such as human resources analysts, some office technicians, and sign‑language interpreters. Some of these positions are located at headquarters in Sacramento, while others are located across DAPO’s 50 field offices. Similar to most other parole positions, the need for support positions is driven by changes in the parolee population. For example, if the parolee population increases, there would be a greater need for human resource analysts to process a potential increase in the number of workers’ compensation claims resulting from the additional parole agents hired to supervise parolees. Conversely, if the parolee population declines, CDCR would need fewer human resource analysts to process workers’ compensation claims. In other words, these positions are in effect based on ratios similar to direct‑supervision positions. We note, however, that the department makes requests for support positions on an ad‑hoc basis rather than annually adjusting these positions for changes in the parolee population like it does for its positions that involve the direct supervision of parolees.

Parolee Population Expected to Increase Temporarily Due to Proposition 57. As we discussed earlier in this report, the average daily parolee population is projected to increase to 49,800 in 2018‑19, an increase of about 2,800 parolees (6 percent) from 2017‑18. The population is expected to continue increasing until it reaches a peak of 51,000 parolees in 2019‑20. This increase is largely driven by Proposition 57. However, this increase is expected to be temporary and the parolee population is expected to decline by 1,000 (or 2 percent) from 2019‑20 to 2021‑22.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a $23 million General Fund augmentation and 94 additional direct‑supervision positions due to the projected increase in the parolee population in 2018‑19. The budget also proposes a $2.3 million General Fund augmentation and 23 additional support positions. This reflects a 4 percent increase in the number of these positions from the current‑year level. The proposed support positions include analysts, a sign‑language interpreter, and office technicians. According to the department, these positions are necessary to account for increased workload related to the additional direct‑supervision staff proposed for 2018‑19, as well as workload associated with direct‑supervision positions provided in prior years.

LAO Assessment

Staffing Requested for 2018‑19 Seems Appropriate. As discussed above, the department’s budgeting methodology for direct‑supervision and support positions are in effect based on staffing ratios that take into account the projected size of the parolee population for 2018‑19. Accordingly, we find that the requested direct‑supervision and support positions are appropriate based on the estimated parolee population for 2018‑19 at this time. We note, however, this estimate could change in May based on updated projections of the parolee population.

Requested Support Positions Will Not Be Adjusted Annually in Future Years. While the budgeting methodology for the proposed support positions takes into account the projected size of the parolee population in 2018‑19, it would not be annually adjusted as would be the case for the requested direct‑supervision positions. If these positions were adjusted on an annual basis, similar to the direct‑supervision positions, it would lead to a more complete accounting of the need for them.

LAO Recommendations

In view of the above, we recommend the department utilize a budgeting methodology that is based on specific staffing ratios, and takes into account the size and composition of the parolee population, to annually adjust the total number and type of positions needed each year—not just for direct‑supervision positions. We recommend that the Legislature require the department to report at budget hearings on a timeline for incorporating support staff into the annual parole staffing adjustment. Pending such a report from the department and the availability of updated parolee projections that could change the level of positions needed, we withhold recommendation on the proposed staffing requests until the May Revision.

Wage Increases for Inmate Workers Assigned to

Facility Maintenance Jobs

LAO Bottom Line. The Governor’s budget proposes a $1.8 million General Fund augmentation for CDCR to increase wages for facility maintenance inmate workers to equal those provided by other employment programs available to inmates, with the intention that this would allow the department to hire sufficient inmate workers to reduce its maintenance backlog. We find that additional information is needed in order for the Legislature to assess the potential effectiveness of the proposal and whether other actions are needed to fully address CDCR’s maintenance backlog. As such, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to report during budget hearings on specified information (such as how it plans to fill its vacant civil service positions who also perform maintenance work) and withhold action on the Governor’s proposal until it receives this information.

Background

Employment Opportunities for Inmates. Inmates have various opportunities for employment while incarcerated. Generally, inmate jobs fall into three categories:

- California Prison Industry Authority (CalPIA). CalPIA is a semiautonomous state agency that provides work assignments and vocational training to inmates and is funded primarily through the sale of the goods and services produced by these inmates. Many of these goods are purchased by state agencies. CalPIA has the capacity to employ about 7,800 inmate workers across 34 prisons who earn between $0.35 and $1.00 per hour. However, it reports that roughly 30 percent of these positions are currently vacant. While in CalPIA positions, inmates can participate in pre‑apprenticeship programs and gain certification in various career fields, making them more qualified to be hired for apprenticeships or other entry‑level positions upon release. When inmates complete these training programs, they generally earn credits that reduce the amount of time they must serve in prison. For example, inmates who complete CalPIA’s dental technician training program earn four weeks off of their sentence.

- Inmate Ward Labor (IWL) Program. CDCR’s IWL program hires inmates to work on capital outlay and repair projects at its prisons. These inmates are employed by IWL for the duration of a particular project and learn various skills, such as roofing or building foundation pads, depending on the nature of the project. When working for IWL, inmates earn between $0.35 and $1.00 per hour. In addition, some IWL inmate workers participate in IWL’s pre‑apprenticeship program through which they earn seven weeks off of their prison sentence. About 1,300 inmates and wards participated in IWL projects in 2017.

- Other Inmate Jobs. CDCR employs inmates to support prison operations in various ways, including cleaning and maintaining facilities, providing clerical support, and grounds keeping. These inmates earn between $0.08 and $0.37 per hour and generally do not receive credits or participate in formalized training programs through their job. Inmate workers assigned to facility maintenance jobs work under the supervision of civil service tradespersons on the maintenance of prisons’ mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems. Facility maintenance inmate workers use many of the same skills as some inmate workers in IWL and CalPIA positions.

CDCR Reports Backlog in Prison Maintenance. CDCR employs civil service tradespersons—such as plumbers, electricians, and carpenters—along with facility maintenance inmate workers to maintain its prisons. The department reports that it currently has a backlog in maintenance work orders and that CDCR’s Office of Audits and Court Compliance and the Department of Public Health have repeatedly cited CDCR for noncompliance with preventative maintenance policies.

The department argues that the above backlog is primarily due to two factors. First, the department indicates that there is a lack of inmate workers to help complete the maintenance work on a routine basis. Specifically, the department reports that 656 of its 2,834 (23 percent) inmate positions in facility maintenance are currently vacant. Moreover, CDCR believes that the higher wages, credit earning opportunities, and formalized training programs offered by CalPIA and IWL for often similar types of work attract inmates away from facility maintenance jobs. Second, CDCR indicates that it has been unable to hire sufficient numbers of civil service facility maintenance workers. In 2016‑17, the department reported that it had nearly $19 million in savings from civil service facility maintenance vacancies.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor proposes a $1.8 million General Fund augmentation in 2018‑19 for CDCR to increase wages for facility maintenance inmate workers to equal those received by CalPIA and IWL inmate workers—specifically from between $0.08 and $0.37 per hour to between $0.35 and $1.00 per hour. CDCR expects that the proposed wage increase would attract inmates who would otherwise have chosen CalPIA or IWL jobs to facility maintenance jobs and allow it to reduce its maintenance backlog.

LAO Assessment

Proposal May Not Effectively Attract Inmates Away From CalPIA and IWL. Under the Governor’s proposal, facility maintenance inmate workers would receive the same wages as CalPIA and IWL workers. However, CalPIA and IWL workers would continue to have access to other benefits—such as credits and pre‑apprenticeship programs—that facility maintenance workers would not. Accordingly, it seems reasonable that many inmates would still choose CalPIA and IWL jobs rather than facility maintenance jobs. Moreover, the incentive that would be created by the proposed pay increase could be reduced if CalPIA subsequently chose to raise its wages. We also note that if the proposal only results in a few additional facility maintenance inmate workers, the department would be paying all facility maintenance inmate workers—including existing ones who choose to work at current wage levels—more for a relatively modest impact on the size of the prison maintenance workforce.

If Effective, Wage Increase Could Generate Other Costs and Concerns. If the proposed wage increase is effective in attracting inmates to facility maintenance jobs—as intended by the administration—the department expects that the number of inmates in IWL and CalPIA positions would decline. This could have a number of potentially unintended consequences. Specifically, a reduction in inmate labor available to CalPIA and IWL could:

- Increase capital outlay costs to the extent that CDCR needs to hire additional contractors to complete capital outlay projects that would have otherwise relied on IWL inmate workers.

- Reduce the amount of goods and services produced by CalPIA, which could result in CDCR and other state departments needing to purchase goods from other suppliers at a higher cost.

- Increase the prison population to the extent that a reduction in the number of inmates participating in IWL and CalPIA training programs reduces the amount of credits these inmates earn, thereby increasing the amount of time they spend in prison.

- Potentially increase recidivism rates to the extent that participation in IWL and CalPIA training programs is more effective at reducing recidivism than facility maintenance jobs, given that the pre‑apprenticeships these programs offer potentially make inmates more employable upon release

Proposal May Not Increase Available Inmate Labor Pool. While attracting inmates away from CalPIA and IWL to facility maintenance jobs (as proposed by the administration) could be one way to help ensure that there are enough inmate workers to complete routine maintenance work, it is not the only way. For example, it is possible that the proposed increase in wages could prompt inmates who are not currently employed in CalPIA or IWL but who have skills in relevant trades to seek out facility maintenance jobs. That is, the wage increase would expand the overall labor pool of workers. However, CalPIA vacancies suggest that this would be unlikely to occur. This is because despite offering a pay rate identical to the one proposed by the department for facility maintenance inmate workers (along with other nonpay benefits), CalPIA has a vacancy rate of roughly 30 percent. This suggests that most or all of the inmates who are eligible and willing to work at CalPIA’s pay rate are already doing so. Accordingly, it appears likely that the Governor’s proposal would not be effective in expanding the labor pool.

Proposal Does Not Address Shortage in Civil Service Maintenance Staff. As discussed above, CDCR indicates its current maintenance backlog is partly due to the difficulty of hiring civil service maintenance workers. Since the Governor’s proposal does not address this issue, the extent to which the proposal would effectively reduce CDCR’s maintenance backlog is uncertain. For example, if the majority of the backlog is caused by a lack of civil service workers, then the proposed wage increase for inmate workers would not have more than a modest impact on the backlog. Furthermore, it is unclear how the department plans to use savings from civil service maintenance vacancies and whether a portion of the savings could be used to pay for the proposed inmate wage increase.

LAO Recommendation

In view of the above concerns, we recommend that the Legislature require the department to report at budget hearings on the following information: (1) why it thinks that the proposed wage increase would result in fewer facility maintenance inmate worker vacancies; (2) how it plans to mitigate potential unintended consequences of the proposal, including increased capital outlay costs, a higher prison population, and increased recidivism rates; (3) the number of civil service maintenance worker vacancies; (4) how CDCR has spent the savings resulting from those vacancies in recent years and whether a portion of such savings could be used to increase inmate worker pay; and (5) what steps it is taking to address the civil service staffing shortage, such as increasing advertising or using contractors. This information would help the Legislature assess the potential effectiveness of the Governor’s proposal and whether other actions—beyond those proposed by the Governor—are needed to effectively help reduce CDCR’s maintenance backlog. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal until it receives the above information.

Video Surveillance at California State Prison, Sacramento

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal to implement video surveillance in certain housing units at California State Prison, Sacramento (SAC) until the evaluation of the video surveillance system at High Desert State Prison (HDSP) is completed this spring. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report at spring budget hearings on other strategies is developing to address the concerns about staff misconduct at SAC.

Background

Restricted Housing for Inmates With Mental Illness. CDCR uses restricted housing units to temporarily house inmates who have committed a serious violation or whose presence in a less restricted environment poses a threat to themselves, others, or the integrity of an investigation. In general, Security Housing Units (SHU) are used for longer‑term restricted housing placements, while Administrative Segregation Units (ASU) are used for shorter‑term placements. While in these units, inmates’ freedom of movement and interaction with other inmates is substantially restricted.

When Enhanced Outpatient Program (EOP) inmates—those diagnosed with serious mental disorders but do not require inpatient treatment—receive SHU terms, they are housed in a Psychiatric Services Unit (PSU). (About 6 percent of the inmate population is part of EOP and, thus, must be housed separately from the general inmate population.) A PSU is intended to provide EOP services to inmate‑patients in a maximum security setting. Similarly, EOP inmates requiring short‑term segregation are placed in ASUs designated to provide EOP care known as ASU‑EOPs.

Alleged Staff Misconduct at SAC. In 1995, a federal court ruled in a case now referred to as Coleman v. Brown that CDCR was not providing constitutionally adequate mental health care to its inmates. As a result, the court appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on CDCR’s progress towards improving mental health care. In fall 2016, a Special Master monitoring team documented numerous allegations of officer misconduct by EOP inmates in restricted housing at SAC. The allegations included physical abuse, denial of food, verbal abuse, tampering with mail and property, inappropriate response to suicide attempts or ideation, and retaliation for reporting misconduct.

The monitoring team recommended that CDCR install surveillance cameras in all PSUs or place body cameras on all custody officers who work in these units. According to the team, these measures should reduce the use of excessive force, help resolve allegations of excessive force, and increase officer accountability. The monitoring team also recommended that CDCR screen staff for their suitability to work with the PSU population and provide them with additional training focused on mental health issues and crisis intervention.

Video Surveillance at CDCR Institutions. The 2017‑18 Budget Act provided $11.7 million for CDCR to implement comprehensive video surveillance at HDSP and Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF). The administration expects these surveillance systems to provide objective evidence with which to investigate inmate allegations against staff, reduce inmate misconduct, and reduce attempted suicides. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine are currently conducting an evaluation of video surveillance on one yard at HDSP. Among other metrics, the researchers are monitoring inmate complaints against staff, use‑of‑force incidences, inmate misconduct, and suicide attempts. The evaluation findings are expected to be released in spring 2018. Several of CDCR’s other prisons currently have video surveillance with varying degrees of institutional coverage. For example, both the California City Correctional Facility and the California Health Care Facility have video coverage of all facilities, yards, and housing units.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $1.5 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis in 2018‑19 for CDCR to purchase an audio/video surveillance system for the PSU and ASU‑EOP at SAC. Under the proposal, $177,000 would be needed annually beginning in 2019‑20 to operate and maintain the equipment. Similar to the systems at HDSP and CCWF, CDCR expects the proposed cameras to provide objective evidence with which to investigate inmate allegations against staff, reduce violent incidents, and reduce attempted suicides.

Premature to Expand Video Surveillance Before Evaluation Complete

While video surveillance at SAC could prove to be a worthwhile investment, we find it premature to expand its use at additional prisons until the evaluation of video surveillance at HDSP is completed this spring. The results of the evaluation could shed light on whether video surveillance can be effective at addressing the issues identified at SAC, since many similar issues have been identified at HDSP. In the meantime, the department should focus on developing other strategies to address the concerns at SAC, such as ensuring that staff in these units are adequately trained to work with inmate‑patients as was recommended by the monitoring team.

LAO Recommendation

We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposal to implement video surveillance at the PSU and ASU‑EOP at SAC until the evaluation report on the surveillance system at HDSP is available in spring. In order to ensure that the evaluation report is available to inform the Legislature’s deliberations on the 2018‑19 budget, we also recommend that the Legislature require the administration to provide it with the results of the HDSP evaluation prior to the May Revision. We further recommend requiring CDCR to report at spring budget hearings on other strategies it is developing to address the concerns at SAC, such as ensuring that staff are adequately trained to work with inmates in the PSU and ASU‑EOP units.

Ventura Training Center

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to convert the existing Ventura conservation camp for inmates into a new Ventura Training Center that would provide a firefighter training and certification program for parolees. We find that the proposed program is unlikely to be the most cost‑effective approach to reduce recidivism. To the extent that reducing recidivism is a high priority for the Legislature, it could redirect some or all of the proposed funding to support evidence‑based rehabilitative programming for offenders in prison and when they are released from prison. Similarly, the Legislature could explore if other options are available to provide the California Conservation Corps (CCC) corpsmembers training opportunities, to the extent it is interested in doing so.

Background

Offender Rehabilitation Programs Intended to Reduce Recidivism. Research has shown that certain criminal risk factors are particularly significant in influencing whether or not individuals commit new crimes following their release from prison (known as recidivating). For example, individuals who have low performance, involvement, and satisfaction with school and/or work are more likely to recidivate than individuals who do not exhibit these characteristics. Research also shows that rehabilitation programs (such as substance use disorder treatment and employment preparation) can be designed to address specific criminal risk factors. For example, employment counseling programs can help reduce or eliminate the criminal risk resulting from an offender’s low involvement in work. In addition, research suggests that programs are most effective in reducing recidivism when they are targeted at individuals who have a high risk of recidivating due to factors that could be addressed with rehabilitation programs. (For more information on the key criminal risk factors and principles for reducing recidivism, please see our recent report, Improving In‑Prison Rehabilitation Programs.)

State Provides Various Rehabilitation Programs to Parolees. Prior to an inmate’s release from prison, CDCR generally uses assessments to determine how likely the inmate is to recidivate as well as what criminal risk factors he or she has. The department uses this information to target many of its rehabilitation programs once the inmate is released and supervised by state parole agents in the community. The 2017‑18 budget included $215 million to support various parolee rehabilitation programs. One such program is the Specialized Treatment for Optimized Programming (STOP), which provides a range of services, such as substance use disorder treatment, anger management training, and employment services to parolees. To be eligible for STOP, parolees must have a moderate to high risk of reoffending and be identified as having a criminal risk factor that can be addressed by services available through the program.

Multiple Agencies Have Professional Firefighter Crews. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) employs over 7,000 firefighters each year during fire season. Of those, about 1,700 are seasonal firefighters, classified as “Firefighter I,” CalFire’s entry‑level firefighter classification. A Firefighter I is a temporary employee who is hired only for the duration of the “fire season”—the period of time when fires are most likely to occur at the greatest intensity. Individuals are usually hired in April, May, or June—as CalFire increases staffing for the fire season—and work for up to nine months, depending on the duration and intensity of the season. More experienced firefighters can apply to become a Firefighter II—a permanent employee. Both types of firefighters typically staff “engine crews,” which are made up of a fire engine and three to four firefighters, as well as an engine operator.

Federal and local agencies also operate fire crews. Some larger local agencies, such as the Los Angeles County Fire Department, provide their own wildfire protection. However, many agencies mostly respond to structure fires rather than wildfires. In addition, the U.S. Forest Service employs roughly 10,000 firefighters for fire protection in national forests.

State Conservation Camps Provide Inmate Firefighter Hand Crews. While in prison, certain inmates have the opportunity to serve as inmate firefighters as part of a hand crew and live in a conservation camp jointly operated by CDCR and CalFire (rather than remain in a prison facility). (Hand crews are usually made up of 17 firefighters that cut “fire lines”—gaps where all fire fuel and vegetation is removed—with chain saws and hand tools.) Inmates qualify for camps if CDCR has determined they (1) can be safely housed in a low‑security environment, (2) can work outside a secure perimeter under relatively low supervision, and (3) are medically fit for conservation camp work. CDCR makes this determination generally based on various factors, including the nature of the crimes inmates are convicted of, their behavior while in prison, and the time they have left to serve on their sentence. CDCR provides correctional staff at each camp who are responsible for the supervision, care and discipline of inmates. CalFire maintains the camp, supervises the work of the inmate fire crews, and is responsible for inmate custody while they are working. Currently, CalFire maintains 39 conservation camps statewide that have the capacity to house more than 4,300 offenders. (One of these camps houses juvenile offenders.) As of January 10, 2018, there were about 3,500 adult inmates housed in conservation camps. Each camp costs roughly $2.4 million to operate annually, or about half a million dollars per hand crew.

Inmates on hand crews receive basic training that consists of a week of classroom training and a week of field training that covers wildland fire safety and attack, hand tool use, teamwork, and crew expectations. Once assigned to a fire crew, inmates continue to receive training in things like cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency response, with some progressing to more responsible positions on the crew, such as a chainsaw operator.

CCC Provides Fire Crews and Support. The CCC maintains seven fire crews that are staffed by corpsmembers and typically train and operate under the supervision of CalFire Fire Captains. While assigned to wildfires, the crews are utilized primarily to construct fire lines. Fire crews also may assist fire engine crews and work after a fire is contained to extinguish any remaining hot spots. After a fire is completely extinguished, crews are used for post‑fire restoration work such as reseeding. According to CalFire, each crew costs about $1 million to operate annually.

Governor’s Proposal

Establish Ventura Training Center to Provide Firefighter Training and Certification for Parolees. The Governor proposes to convert the existing Ventura conservation camp for inmates into a new Ventura Training Center that would provide a firefighter training and certification program for parolees. (The inmate firefighter hand crews currently based at the Ventura conservation camp would be relocated to other state conservation camps.) Upon full implementation, the program would accommodate 80 parolees, selecting in most cases from those who had served as inmate firefighters in a conservation camp prior to their release from prison and were nominated for the program by CalFire and CDCR staff.

Parolees would be enrolled in the program for a total of 18 months. According to the administration, program participants would be paid and receive (1) 3 months of classroom instruction in basic forestry and firefighting, (2) 3 months of industry‑recognized firefighting training and certification (while also being available to support fire suppression and resource management efforts as needed), and (3) 12 months of full‑time assignment as part of an engine crew. The administration indicates that upon completion of the program, participants would have the experience and certifications to apply for entry‑level firefighting jobs with local, state, and federal firefighting agencies. The administration proposes to contract with a nonprofit organization to provide participating parolees with life skills training, reentry and counseling services, and job placement assistance to help them maximize their scoring capabilities in hiring processes and assist them with other challenges related to reentry. Participants would also have access to high school courses through CCC’s existing contract with the John Muir Charter School.

Allow Some CCC Corpsmembers to Participate in Selected Trainings. In addition to parolees, the program would allow up to 20 CCC corpsmembers at a time to participate in select trainings and certification opportunities to be identified by CCC and CalFire. The amount of time the corpsmembers would spend at the training center could vary from a week up to a month or more. The administration reports that corpsmembers at the training center would be housed separately from parolees but could participate in trainings together with them.

Provide Funding to Operate Program. The Governor requests $7.7 million from the General Fund and 12.4 positions in 2018‑19 to implement and operate the program. Under the proposal, $6.3 million from the General Fund and 12.4 positions would be needed to operate the program in 2019‑20 and annually thereafter. The $7.7 million proposed for 2018‑19 would be allocated as follows:

- CalFire ($2 Million). These resources would allow CalFire to purchase equipment and training materials for trainees, make facility repairs, and hire 24‑hour site security services.

- CDCR ($2.1 Million).These resources would be used by CDCR to provide 1.4 parole agents to supervise parolees at the new Ventura Training Center and six other staff—including a groundskeeper, custodian, and cooks—to operate the training center. In addition, CDCR would receive funds to contract with a nonprofit organization to provide case management and other services to participants.

- CCC ($3.5 Million). The bulk of these resources would be used to pay the salaries of parolee participants in the program, which are estimated to be $2.2 million annually. Under the proposal, CCC would provide payroll services for the parolees in the program. (The CCC has a payroll system that is designed to meet the needs of a short‑term, non‑civil service workforce.) The CCC also requests five positions to perform payroll functions and to provide supervision of corpsmembers while they are at the training center.

Make Infrastructure Improvements. In addition, the budget includes $1.1 million from the General Fund in 2018‑19 to develop preliminary plans for renovating the existing conservation camp to meet the needs of the proposed program. Specifically, these renovations would (1) replace and upgrade existing facilities (such as the staff barracks and equipment storage facilities), (2) add privacy to showers and bathrooms in existing dormitories, (3) construct a separate dormitory for female participants, (4) construct additional administrative and classroom space, and (5) build a gym for staff. The proposed renovations are expected to cost a total of $18.9 million.

Recidivism Reduction Is Primary Goal. The administration indicates that the primary goal of the proposed program is to reduce recidivism by helping ex‑offenders gain employment as firefighters. However, the proposal also suggests that because trainees would be available to assist with emergency response, the program could potentially increase firefighting resources.

LAO Assessment

While providing additional resources to reduce recidivism could be a worthwhile investment, we find that the Governor’s proposal raises several concerns. Specifically, we find that the proposal (1) is not evidence based; (2) would not target high‑risk, high‑need individuals; (3) would be unlikely to lead to employment for participants; (4) would likely not be cost‑effective; and (5) includes resources that are not fully justified. We also find that providing additional training to CCC members could be achieved in other ways.

Not Evidence Based. Research shows that rehabilitation programs that are evidence based are most likely to be effective at reducing recidivism. To be evidence based, a program must be modeled after a program that has undergone rigorous evaluations showing that it reduces recidivism. However, the administration has not provided examples of any other firefighter training programs that have been found to reduce recidivism. Accordingly, it is unclear whether the proposed intervention model has ever been found to be effective elsewhere. Furthermore, the administration is not proposing a feasibility study, pilot, or sufficiently rigorous evaluation plan for the program. As a result, it unclear how the administration would know if the proposed program were successful once it was implemented.

Not Targeted to High‑Risk, High‑Need Parolees. As discussed above, research suggests that rehabilitation programs are most likely to be successful when targeted at high‑risk, high‑need individuals. However, the administration plans to primarily recruit parolees who served as inmate firefighters in a conservation camp prior to their release from prison. These parolees tend to be of low risk to the community and have demonstrated a willingness and ability to work hard. Although CDCR does not separately track recidivism rates for inmates released from conservation camps, we expect that these inmates would be among the least likely in CDCR to recidivate. Moreover, the administration indicates that conservation camp inmates would be nominated by CalFire and CDCR staff for the program based on their nonviolent behavior and conformance to rules while incarcerated. This further suggests that program participants would already have relatively low risks of recidivism and low needs for rehabilitative programming. Accordingly, we find that the proposed target population is both inconsistent with best practices and with CDCR’s own efforts to target rehabilitation programs to high‑risk, high‑need offenders.