LAO Contacts

- Ross Brown

- Cap-and-trade

- Air quality

- Rachel Ehlers

- Coastal adaptation

- Water conservation

- Resources bond

- Shawn Martin

- Drinking water

- Toxic pollution

- Jessica Peters

- Parks and forestry

- Fire protection

- Brian Brown

- Overall resources and environment

February 14, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Natural Resources and Environmental Protection

- Executive Summary

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Wildfire Prevention and Response

- Climate Change

- Water

- Environmental Quality

- Resources Capital Outlay

- Bond Administration

- Budget Transparency

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess several of the Governor’s budget proposals in the natural resources and environmental protection areas. Based on our review, we recommend various changes, as well as additional legislative oversight. Below, we summarize our major findings and recommendations. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Budget Provides $11 Billion for Programs

The Governor’s budget for 2019‑20 proposes a total of $11.3 billion in expenditures from various fund sources for programs administered by the Natural Resources ($6.7 billion) and Environmental Protection ($4.6 billion) Agencies. The budget plan for these programs is mostly similar to what was approved in 2018‑19 with only a few major changes proposed.

Budget Includes Significant New Fiscal and Policy Proposals

Expansion of Wildfire Response Capacity. The Governor’s budget includes $97 million—mostly from the General Fund—for several proposals to enhance CalFire’s wildfire response capacity. We generally find these proposal to be reasonable given the increasingly severe wildfire seasons and, therefore, recommend the Legislature approve most of the Governor’s proposals. We also recommend an assessment of existing state and local fire response capacity in order to better inform where additional resources could best be targeted in future years.

Cap‑and‑Trade Expenditure Plan. The Governor’s budget includes a cap‑and‑trade expenditure plan that (1) assumes total Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) revenue of $4.7 billion in the current and budget year and (2) proposes to spend a total of $2.4 billion in 2019‑20. We estimate revenue will be roughly $800 million higher over the two‑year period. While there is uncertainty about future revenue, we find that the Legislature likely could spend a somewhat higher amount in the budget year and still maintain a healthy fund balance.

Regarding proposed expenditures, we find that there is limited information provided by the administration on (1) expected programmatic outcomes, (2) necessary adjustments for certain programs to stay within proposed allocations, and (3) key details for the workforce development programs proposed. Based on these questions, we recommend that the administration provide additional information at budget hearings to inform budget decisions.

Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Program. The administration proposes to create a new program that would (1) impose charges on water customers and certain agricultural entities—with estimated annual revenues of at least $110 million when fully implemented—and (2) provide funding to address unsafe drinking water throughout the state. We find that the proposal is consistent with the state’s human right to water policy. We also identify other issues for legislative consideration, including uncertainty about revenue and cost estimates and trade‑offs with the proposed provisions to limit the state’s authority to take certain enforcement actions against polluters.

Deferred Maintenance. The administration proposes $67 million—mostly General Fund—to implement deferred maintenance projects at six natural resources departments. While we find that additional investments in maintaining state assets is an important budget priority, we recommend that the Legislature require departments to report on what projects they intend to implement to ensure that they will focus on high‑priority activities. We further recommend reporting requirements to enable oversight of (1) how departments maintain their facilities on an ongoing basis and (2) what projects are actually implemented with the funding.

Certain Proposals Highlight Need for Additional Legislative Oversight

Implementation of 2018 Wildfire Legislation. The Governor’s budget includes $235 million—mostly GGRF—for proposals in several departments to implement the 2018 legislative package to increase wildfire prevention and forest health activities. Because we find that the proposals are consistent with the legislation, we recommend the Legislature approve them. We also recommend the Legislature conduct ongoing oversight to ensure effective implementation of the legislative package and offer specific questions to aid in those oversight activities.

Coastal Adaptation. The Governor proposes $3.3 million in ongoing funding (GGRF) for the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and California Coastal Commission to assist local governments in their sea‑level rise adaptation efforts. We recommend the Legislature adopt these proposals because of the potential future impacts of sea level rise. We also recommend that the Legislature continue to work with state and local entities to identify the most effective ways to support local communities’ planning and response needs, including ongoing assessments of progress, how these efforts should be funded, and what additional research and data is needed.

Water Conservation. The Governor proposes $8 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20 (over $2 million ongoing) for the Department of Water Resources and State Water Resources Control Board to implement recent water conservation legislation. We find that the proposals are consistent with legislative intent and recommend approval. We also recommend ongoing oversight to ensure that state and local entities are meeting the deadlines established in the legislation and that overall efficiency and drought resilience outcomes are being attained.

Implementation of AB 617. Chapter 136 of 2017 (AB 617, C. Garcia) made various changes to monitor and reduce criteria and toxic air pollutants that adversly effect some communities. The Governor’s budget proposes $276 million—mostly GGRF—to continue the implementation of AB 617, including (1) $260 million for one‑time funding to support local air district activities and incentive programs and (2) $16 million for state administrative activities. The proposal largely is consistent with AB 617 and past budgeted activities. However, we recommend that the Legislature reject a component of the proposal that would provide $3.8 million to the California Air Resources Board because it lacks workload justification. In addition, we recommend that the administration report on its expectations for future funding and expansion.

Exide Cleanup Activities. The Governor proposes $75 million in one‑time General Fund loans—in addition to $177 million in previous loans—to fund the cleanup of residential properties contaminated by airborne lead from the Exide lead‑acid battery recycling facility. This funding would support increased costs to clean up previously identified parcels, as well as clean up hundreds of additional parcels. We recommend the Legislature require the Department of Toxic Substances Control to report on the costs and time frame for completing the residential cleanup, as well as when Exide will begin to repay the state.

Implementation of Proposition 68. The Governor proposes about $1 billion in spending from Proposition 68 (2018 bond) for a number of programs in various departments. The proposals appear to be reasonable and consistent with the requirements of the bond, though the Legislature may want to adjust the funding amounts for particular programs to expedite or increase the effectiveness of program implementation based on input from stakeholders and the state departments.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

In this section, we provide an overview of the Governor’s 2019‑20 budget plan for the state’s natural resources and environmental protection departments, including a brief description of the main changes from the current year. Later in this report, we provide more detailed assessments of many of these specific proposals.

Overall Budget Plan Mostly Similar to Current Year

Total Spending of $11.3 Billion Proposed. California’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies oversee the activities of about 40 state departments, boards, and conservancies whose missions are to protect and restore the state’s natural and environmental resources and to ensure public health and environmental quality. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget proposes total funding of $11.3 billion from all sources—the General Fund, as well as special, bond, and federal funds—for these entities. As shown in Figure 1, this reflects a net reduction of $432 million (4 percent) compared to the current‑year budgeted level. (Later in this section, we compare to revised estimates for the current year, which have been updated since the enactment of the budget.) While there is a net reduction in overall spending authority, the proposed budget is mostly consistent with what was approved in the current year and does not reflect significant programmatic reductions. Instead, the overall net spending reduction largely reflects the appropriation of one‑time funding in the current year. For example, the current‑year budget provided $255 million more in one‑time bond funds from Proposition 68 (2018) than is proposed for the budget year. Partially offsetting these reductions, the proposed 2019‑20 budget also includes some proposals for increased funding, for example, to implement recent wildfire prevention legislation. We summarize the most significant budget adjustments below.

Figure 1

Proposed Spending Compared to 2018‑19 Budgeted Level

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Agency |

2018‑19 Budgeted |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Natural Resources |

$7,212 |

$6,713 |

‑$499 |

‑7% |

|

Environmental Protection |

4,544 |

4,611 |

67 |

1 |

|

Totals |

$11,756 |

$11,324 |

‑$432 |

‑4% |

Summary of Budget Changes

Total of $6.7 Billion Proposed for Natural Resources Departments. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s budget plan for entities within the Natural Resources Agency includes a total of $6.7 billion. Almost half of this funding (including most of the General Fund support) is for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) and to repay past natural resources‑related general obligation bonds. Just over half of the total is proposed to be funded from the General Fund with the remainder mostly from special funds and bond funds. Of the total proposed, $5.1 billion (76 percent) is to administer state programs, and most of the remainder is for local assistance—generally grants to local governments and nonprofits to implement projects.

Figure 2

Natural Resources Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 Actual |

2018‑19 Estimated |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Total |

$6,258 |

$9,565 |

$6,713 |

‑$2,853 |

‑30% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

$1,727 |

$2,200 |

$2,027 |

‑$173 |

‑8% |

|

General obligation bond debt service |

968 |

1,022 |

1,145 |

123 |

12 |

|

Parks and Recreation |

792 |

1,236 |

851 |

‑384 |

‑31 |

|

Water Resources |

556 |

2,197 |

745 |

‑1,452 |

‑66 |

|

Fish and Wildlife |

520 |

538 |

477 |

‑60 |

‑11 |

|

Energy Commission |

426 |

867 |

402 |

‑465 |

‑54 |

|

Natural Resources Agency |

136 |

371 |

223 |

‑148 |

‑40 |

|

Wildlife Conservation Board |

496 |

196 |

196 |

— |

— |

|

Conservation Corps |

109 |

155 |

143 |

‑13 |

‑8 |

|

Conservation |

168 |

138 |

135 |

‑3 |

‑2 |

|

State Lands Commission |

42 |

100 |

79 |

‑21 |

‑21 |

|

Other resources programsa |

316 |

547 |

289 |

‑258 |

‑47 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$3,127 |

$3,968 |

$3,513 |

‑$455 |

‑11% |

|

Special funds |

1,693 |

2,124 |

1,703 |

‑421 |

‑20 |

|

Bond funds |

1,122 |

3,171 |

1,207 |

‑1,965 |

‑62 |

|

Federal funds |

316 |

302 |

290 |

‑12 |

‑4 |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$4,687 |

$5,775 |

$5,108 |

‑$667 |

‑12% |

|

Local assistance |

1,044 |

2,874 |

1,248 |

‑1,626 |

‑57 |

|

Capital outlay |

527 |

917 |

357 |

‑560 |

‑61 |

|

aIncludes state conservancies, Coastal Commission, and other departments. |

|||||

Total of $4.6 Billion Proposed for Environmental Protection Departments. As shown in Figure 3 , the Governor’s budget plan for entities within the Environmental Protection Agency includes a total of $4.6 billion. Most of this supports three departments—the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle), State Water Resources Control Board, and California Air Resources Board. Of the total budgeted, $3.7 billion (81 percent) is proposed to be funded from special funds, and $2.9 billion (63 percent) is for local assistance.

Figure 3

Environmental Protection Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2017‑18 Actual |

2018‑19 Estimated |

2019‑20 Proposed |

Change From 2018‑19 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Totals |

$4,482 |

$6,356 |

$4,611 |

‑$1,745 |

‑27% |

|

By Department |

|||||

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery |

$1,626 |

$1,846 |

$1,575 |

‑$271 |

‑15% |

|

Water Resources Control Board |

1,206 |

2,222 |

1,358 |

‑864 |

‑39 |

|

Air Resources Board |

1,267 |

1,799 |

1,176 |

‑623 |

‑35 |

|

Toxic Substances Control |

238 |

336 |

349 |

13 |

4 |

|

Pesticide Regulation |

104 |

107 |

109 |

2 |

2 |

|

Other departmentsa |

40 |

46 |

45 |

‑1 |

‑2 |

|

By Funding Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$162 |

$361 |

$125 |

‑$236 |

‑65% |

|

Special funds |

3,567 |

4,435 |

3,713 |

‑722 |

‑16 |

|

Bond funds |

515 |

1,191 |

405 |

‑786 |

‑66 |

|

Federal funds |

238 |

369 |

369 |

‑1 |

— |

|

By Purpose |

|||||

|

State operations |

$1,400 |

$1,911 |

$1,698 |

‑$212 |

‑11% |

|

Local assistance |

2,928 |

4,445 |

2,913 |

‑1,532 |

‑34 |

|

Capital outlay |

154 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

aIncludes the Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, and general obligation bond debt service. |

|||||

Spending Reductions Primarily Reflect Technical Changes. Compared to updated estimates of current‑year expenditures, proposed 2019‑20 spending for natural resources and environmental protection departments is lower by $2.9 billion (30 percent) and $1.7 billion (27 percent), respectively. These reductions include decreases in spending from the General Fund, as well as bond and special funds. However, these changes largely reflect the expiration of one‑time funding provided in 2018‑19, as well as technical budget adjustments made since the enactment of the 2018‑19 Budget Act, rather than significant programmatic changes.

- One‑Time General Fund Spending in Current Year. Combined, General Fund spending by natural resources and environmental protection departments is estimated to decrease by $691 million compared to revised current‑year estimates. This mostly reflects one‑time funding provided in the current year, including higher estimated emergency firefighting costs of $245 million for CalFire, $170 million for flood protection projects by the Department of Water Resources, $154 million for CalRecycle to conduct debris cleanup activities following recent wildfires, and $100 million to support the construction of a new California Indian Heritage Center. (While the wildfire‑related costs are budgeted as one‑time in 2018‑19, spending for these programs in 2019‑20 could be higher than budgeted based on actual firefighting and debris cleanup activities associated with future fires.)

- Technical Adjustments to Special and Bond Fund Amounts. Under the Governor’s proposed budget, spending from bond funds would decrease by a total of $2.8 billion, and special fund spending would decrease by a total of $1.1 billion, compared to revised current‑year estimates. Much of this apparent budget‑year decrease is related to how certain bond and special funds are accounted for in the budget, making year‑over‑year comparisons difficult. Specifically, bond and special funds that were appropriated but not spent in prior years are often carried over to the current year. The 2018‑19 amounts will be adjusted in the future based on actual expenditures.

Implements Several Key Legislative Measures. The proposed 2019‑20 budget includes a number of proposals for increased funding to implement recent legislative measures. This includes $226 million for various natural resources and environmental protection departments to implement laws passed in 2018 designed to improve forest health and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires. The budget also proposes to begin or continue implementing other legislation passed in recent years, including to increase water conservation efforts by local water agencies, more sustainably manage groundwater, and improve air quality in communities with particularly high concentrations of toxic air pollution.

A Few Significant New Initiatives Proposed. The budget proposes some new programs and expansions of existing programs. The Governor proposes an increase of $97 million (mostly General Fund) to expand the state’s capacity to respond to wildfires, including funding for additional CalFire firefighting crews and dedicated fire crews operated by the California Conservation Corps (CCC). (For comparison, the 2018‑19 budget includes $1.1 billion for baseline wildfire suppression costs.) Other significant new proposals in the budget include (1) $75 million in General Fund loans to the Department of Toxic Substances Control to continue and expand environmental cleanup efforts around the Exide battery facility; (2) $27 million from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) for workforce development programs; and (3) the creation of a new program to support the provision of safe drinking water mainly in small, disadvantaged communities.

Summary of Significant Changes Proposed. Figure 4 lists the most significant funding and policy changes proposed for natural resources and environmental protection departments.

Figure 4

Significant Proposals for 2019‑20

|

Natural Resources |

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parks and Recreation |

|

|

|

|

Conservation Corps |

|

|

Water Resources |

|

|

Environmental Protection |

|

Toxic Substances Control |

|

|

|

Water Resources Control Board |

|

|

|

Air Resources Board |

|

|

Various Departments—Natural Resources and Environmental Protection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wildfire Prevention and Response

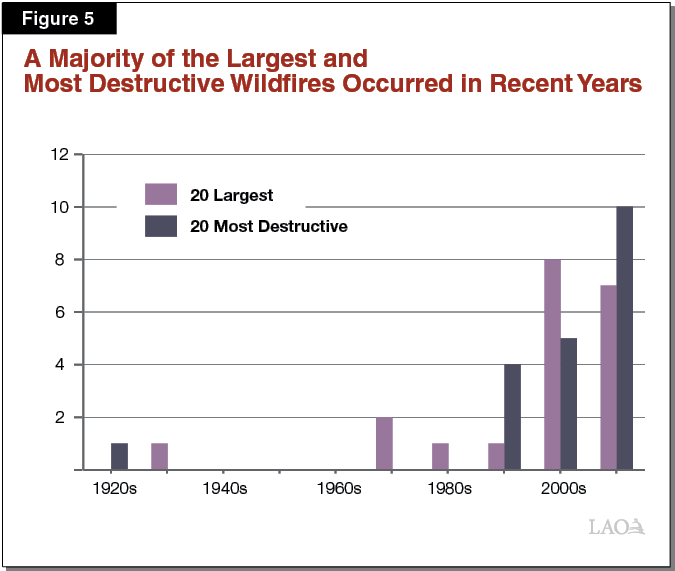

Steps Taken to Address Wildfires After Recent Catastrophic Fire Seasons. As shown in Figure 5, there is a trend of increasingly large and destructive wildfires in recent decades. This trend has been particularly acute in the last couple of years, which have seen some of the worst individual wildfires in the state’s recorded history. The 2018 fire season included several particularly large and catastrophic fires, such as the Mendocino Complex Fire that was the largest in recorded state history at 459,123 acres. The 2018 fire season also included the Camp Fire in Butte County that became the most destructive wildfire in state history with nearly 19,000 structures destroyed and 86 fatalities, including the near‑total destruction of the town of Paradise.

In recent years, the Legislature has taken a number of steps in response to these increasingly severe wildfire seasons, including augmenting funding for forest health, fire prevention, and wildfire response, as well as passing a package of wildfire‑related legislation in 2018.

Governor’s Budget Continues Recent State Efforts to Prevent and Respond to Wildfires. The Governor’s 2019‑20 budget plan includes a total of $654 million across numerous state departments to continue and expand recent efforts related to wildfires. As shown in Figure 6 , this includes $295 million to provide local and recovery assistance, $235 million to implement the 2018 wildfire legislative package, and $124 million to enhance fire response capacity. The amount for local and recovery assistance is proposed on a one‑time basis. Most of the remainder is proposed as ongoing augmentations with some components growing in out‑years.

Figure 6

Governor’s 2019‑20 Wildfire‑Related Budget Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

General Fund |

Other Funds |

Total |

|

Local and Recovery Assistance |

|||

|

Waive local share of debris removal costsa |

$155.2 |

— |

$155.2 |

|

HCD community development block grant |

— |

$108.8 |

108.8 |

|

Property tax backfillb |

31.3 |

— |

31.3 |

|

Subtotal, Local and Recovery Assistance |

($186.5) |

($108.8) |

($295.3) |

|

2018 Legislative Package—Forest Health and Fire Prevention |

|||

|

CalFire (various bills) |

— |

$210.0 |

$210.0 |

|

PUC and Public Advocates Office (SB 901) |

— |

9.1 |

9.1 |

|

CCC (AB 2126) |

$4.5 |

— |

4.5 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board (SB 901) |

2.6 |

1.8 |

4.4 |

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife (SB 901) |

— |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

Air Resources Board (SB 1260) |

— |

3.4 |

3.4 |

|

Subtotal, 2018 Legislative Package |

($7.1) |

($227.8) |

($234.9) |

|

Enhanced Fire Protection |

|||

|

CalFire—13 additional fire engines |

$40.3 |

— |

$40.3 |

|

OES—fire engine prepositioning |

25.0 |

— |

25.0 |

|

CalFire/CCC—5 dedicated fire crews |

13.6 |

— |

13.6 |

|

CalFire—air tankers |

13.1 |

— |

13.1 |

|

CalFire—heavy equipment operator staffing |

10.6 |

— |

10.6 |

|

CalFire—employee wellness |

4.2 |

$2.4 |

6.6 |

|

CalFire—fire detection cameras |

5.2 |

— |

5.2 |

|

CalFire—situational awareness staffing |

4.5 |

— |

4.5 |

|

CalFire—mobile equipment replacement |

3.0 |

— |

3.0 |

|

Military Department—administrative support |

1.7 |

— |

1.7 |

|

Subtotal, Enhanced Fire Protection |

($121.2) |

($2.4) |

($123.6) |

|

State Lands Management |

|||

|

CalFire—acquire demonstration forest lands |

$0.4 |

— |

$0.4 |

|

State Lands Commission—forest health inventory |

— |

$0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Subtotal, State Lands Management |

($0.4) |

($0.2) |

($0.6) |

|

Totals |

$315.2 |

$339.2 |

$654.4 |

|

aDebris removal costs are scored in 2018‑19. bProperty tax backfill amount is the total for a three‑year period and is scored in 2018‑19. HCD = Department of Housing and Community Development; CalFire = California Department of Foresty and Fire Protection; PUC = Public Utilities Commission; CCC = California Conservation Corps; and OES = Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. |

|||

In this section, we will focus primarily on the wildfire proposals for natural resources and environmental protection departments. First, we discuss proposals to implement the 2018 wildfire legislative package, and then we discuss the proposals to enhance fire response capacity.

Implementation of 2018 Legislative Package

The Governor’s budget includes numerous proposals to implement the 2018 wildfire legislative package. In general, the proposals are consistent with the various pieces of legislation. We recommend the Legislature approve these proposals, as well as conduct ongoing oversight to answer key questions about the near‑ and long‑term implementation of the legislative package.

Background

Recent Funding Increases for Forest Health and Fire Prevention. Until recently, CalFire’s budget has included base funding of about $100 million annually for forest health and fire prevention. Beginning in 2014‑15, the state budget has included a series funding augmentations, generally provided on a one‑time basis, for various forest health and fire prevention programs. Figure 7 summarizes the major augmentations. In total, these augmentations have increased spending by more than $200 million annually in the current year and prior year above the $100 million base budget, resulting in total annual CalFire funding for forest health and fire prevention of over $300 million. Most of this funding has been from GGRF.

Figure 7

CalFire Funding Augmentations for Forest Health and Fire Prevention

(In Millions)

|

Program/Activity |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

|

Forest health, fire prevention, and fuels reduction |

42 |

— |

25 |

195 |

155 |

|

Prescribed fire crews |

— |

— |

— |

— |

30 |

|

Urban and community forestry |

— |

— |

15 |

20 |

20 |

|

Partnership with California Conservation Corps |

— |

— |

0 |

5 |

5 |

|

Various othera |

— |

5 |

21 |

16 |

10 |

|

Totals |

42 |

5 |

61 |

236 |

220 |

|

aIncludes tree mortality funding, community‑based fire prevention, and state responsibility area local assistance grants. |

|||||

The largest increase in forest health and fire prevention funding in recent years has been to fund two grant programs—one each for forest health and fire prevention activities—as well as support fuels reduction projects implemented by CalFire staff. The forest health grant program funds projects by nonprofits and local governments that apply multiple treatments—such as prescribed fire, pest abatement, and reforestation—to a forested area. The fire prevention grant program provides funding to nonprofits, local governments, and local fire safe councils primarily for the development of fuel breaks—involving the removal of vegetation to form a clearing often about 300 feet wide and several miles long—to protect at‑risk communities.

In addition, $30 million was provided beginning in 2018‑19 to fund six dedicated prescribed fire crews at CalFire. Once established, these crews will develop and implement prescribed fire projects on a year‑round basis. The rationale for establishing crews dedicated to year‑round prescribed fire work was that the extended and increasingly severe fire seasons did not leave a long enough “off season” for regular CalFire crews to undertake prescribed fire projects, which are an important forest health activity. Other recent augmentations have averaged roughly $40 million annually since 2016‑17. This includes funding for (1) urban and community forestry grants for activities such as planting trees and creating urban forest management plans, (2) partnerships with CCC for fuels reduction projects, and (3) various other activities including grants to remove dead and dying trees and implement community‑based fire prevention projects.

2018 Wildfire Legislative Package Builds on Recent Changes. The Legislature approved several pieces of legislation in 2018 to address the increasingly severe wildfire seasons. The legislative package builds on the recent budget augmentations and enacts numerous policy changes such as establishing new programs and regulatory processes to improve forest health and support fire prevention activities. While there were numerous bills related to wildfires (and disaster response more broadly), there were five bills in the package for which the administration has associated budget proposals for 2019‑20. (We discuss those budget proposals later in this analysis.) Among other changes, the bills contain the following major provisions:

- SB 901—Funding for Forestry and Fire Prevention Activities. Chapter 626 of 2018 (SB 901, Dodd) includes several provisions intended to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires with a focus on forest health, expanding the use of prescribed fires, and reducing fuels. This includes a requirement that the annual state budget include two appropriations—$165 million for forest health and fire prevention grants and fuels reduction projects and $35 million for prescribed burn activities—beginning in 2019‑20 and continuing for a total of five years. In aggregate, these amounts would be roughly the same as the amounts provided for these purposes in 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

- SB 901—Streamlining Permitting Requirements. SB 901 also includes several changes to streamline the regulatory and approval processes related to timber harvesting activities to allow private landowners to remove trees and other vegetation from their property in order to reduce fuel available for forest wildfires. First, SB 901 creates a new exemption, known as the small timberland owner exemption, that allows owners of relatively small acreage forests—60 acres if near the coast or 100 acres elsewhere—to remove trees in order to reduce the continuity of fuels (such as in a densely forested area) if certain other criteria are met. Some examples of criteria to qualify for the exemption include limiting the harvest to certain size of trees harvested and prohibiting removal of the six largest trees in each acre harvested. Second, the legislation expands an existing exemption, known as the forest fire prevention exemption, which has allowed for tree removal or timber harvesting without an approved timber harvest plan in certain cases where the removal of fuels will help reduce the risk of severe wildfires and when the construction of temporary roads are not needed to conduct the project. SB 901 expands the potential use of this exemption by allowing for the construction of temporary roads in certain cases. Third, SB 901 requires CalFire to develop a Wildfire Resilience Program to provide technical assistance to nonindustrial timberland owners to help them with the regulatory process when conducting fuel reduction projects. The legislation specifically requires the Wildfire Resilience Program to provide information on the state permits needed to conduct fuel reduction projects, best practices for wildfire resilience, and available grant programs.

- SB 901—Electric Utilities and Wildfire Mitigation Plans. SB 901 also contains provisions related to electric utilities because utility infrastructure is a common source of wildfire ignition. First, the legislation establishes procedures for wildfire cost financing for investor owned utilities (IOUs) to apply for recovery of costs incurred as a result of catastrophic wildfires. Second, SB 901 adds additional required elements for wildfire mitigation plans prepared by IOUs and reviewed by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) in consultation with CalFire. Specifically, IOUs must describe their future plans related to deenergizing portions of the electrical distribution system, managing vegetation along utility corridors, inspecting infrastructure, and other steps they will take to modernize infrastructure and improve safety.

- SB 1260—Prescribed Fires. Among other things, Chapter 624 of 2018 (SB 1260, Jackson) supports the use of prescribed fires for forest health and wildfire prevention in two key ways. First, the legislation requires the California Air Resources Board (CARB) in coordination with local air districts to conduct enhanced air quality and smoke monitoring to provide air regulators with improved information when reviewing requests for conducting prescribed fires. Second, SB 1260 requires CalFire to develop a professional “burn boss” curriculum and certification program that would create a consistent standard for the education and skills needed for people to conduct prescribed fires. Under this program, CalFire staff members and private individuals or companies could become certified in order to increase the workforce capable of safely conducting prescribed fires.

- AB 2126—Forestry Corps Crews. Another component of the legislative package related to forest health is a requirement in Chapter 635 of 2018 (AB 2126, Eggman) that the CCC establish four “forestry corps” crews to develop and implement forest health projects, such as fuels reduction, tree planting, and cone and seed collection. CCC is also required to assist forestry corps members in obtaining forestry degrees or certificates.

- AB 2518—Wood Product Manufacturing Facilities. Chapter 637 of 2018 (AB 2518, Aguiar‑Curry) requires CalFire and the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection (BFFP) to identify barriers to utilizing small trees and other woody biomass in the production of mass‑timber and other innovative wood products after they are removed from forests in California. AB 2518 also requires the Forest Management Task Force, staffed by CalFire, to develop recommendations for where to site wood product manufacturing facilities.

- AB 2911—Building Standards and Surveys of High‑Risk Communities. Chapter 641 of 2018 (AB 2911, Friedman) requires the Office of the State Fire Marshall (OSFM) within CalFire to (1) recommend updated building standards to better protect structures from wildfire risks, (2) develop a list of low‑cost retrofits that could be implemented at existing structures to reduce the risks, and (3) provide this list to the public through education and outreach efforts. AB 2911 also requires BFFP, in consultation with OSFM, to survey local governments in certain high‑risk fire areas to identify existing subdivisions having only one roadway to access the subdivision. For these communities identified, the board is required to make recommendations to reduce wildfire risks and track the extent to which recommendations are implemented.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget includes $235 million (mostly from the GGRF) and 213 positions across five different natural resources and environmental protection departments, as well as the CPUC, to implement the major components of the 2018 wildfire legislative package.

CalFire Proposals. The majority of the funding and positions proposed—$210 million (GGRF) and 121 positions—is for CalFire, as described in greater detail below.

- Forest Health and Fire Prevention Grants ($165 Million). The Governor’s budget includes $165 million, as required by SB 901, and 19 positions for forest health grants, fire prevention grants, and fuel reduction projects conducted directly by CalFire staff. (The 19 positions were established in 2018‑19 on a one‑time basis. This proposal provides ongoing funding for these positions.)

- Prescribed Fire Staffing Expansion ($35 Million). The budget includes $35 million, as required by SB 901, and 78 new positions to create four additional prescribed fire crews, as well as provide associated administrative and technical support. (The budget also reflects the continuation of 79 positions authorized in 2018‑19 to staff the six initial crews and one research position, for total prescribed fire staffing of 157.)

- BFFP Regulatory Activities ($2.6 Million). The budget includes $2.6 million and two positions for the board to develop new regulations needed to implement various provisions of SB 901. For example, SB 901 requires new regulations for fuel breaks to protect certain types of communities. This funding includes $2 million to contract for technical and legal assistance to develop these regulations.

- Burn Boss Certification Development ($2.5 Million). The budget proposes $2.5 million and eight positions to conduct research, provide training, and monitor prescribed fire activity in the state. Under the proposal, CalFire would contract with California State University, Sacramento to develop the burn boss curriculum. The proposal also includes $100,000 for public outreach.

- Building Standards and Surveys of High‑Risk Communities ($2.3 Million). The Governor’s budget includes $2.3 million and six positions to evaluate wildfire risks for certain existing communities. Specific activities would include conducting surveys of existing subdivisions, making recommendations to local governments on how to reduce fire risks, researching evacuation standards and road design, and tracking whether recommendations are implemented by local communities.

- Wildfire Resilience Program Development ($2 Million). The budget proposes $2 million and seven positions to establish the Wildfire Resilience Program required by SB 901. The new positions would provide staff to conduct outreach to nonindustrial timberland owners throughout the state, create and maintain a list of permits required for fuels reduction and forest management projects, summarize research on wildfire resilience, and post information on state websites.

- Identification of Barriers for Wood Product Manufacturing Facilities ($400,000). The budget includes $400,000 (one time) for a consultant contract to assist CalFire and BFFP in developing a report on barriers to mass‑timber production in California and barriers to other innovative wood product manufacturing that uses smaller trees or woody biomass removed in the course of completing fuels reduction activities.

- Utility Wildfire Mitigation Plan Reviews ($227,000). The budget proposes $227,000 to support one research analyst at CalFire to assist CPUC with the review of IOU wildfire mitigation plans. CalFire and CPUC have entered into a memorandum of understanding to facilitate data sharing and allow CalFire to provide technical assistance to CPUC. The research analyst would develop geographic information system data, generate maps, and conduct research and modeling to evaluate the effectiveness of wildfire mitigation plans submitted by IOUs.

Other Proposals. The remaining $25 million requested is for proposals at various other state departments.

- CPUC and Public Advocate’s Office ($9.1 Million). The budget provides $6.6 million (Public Utilities Commission Utilities Reimbursement Account) and 34 positions to CPUC for ongoing workload related to SB 901, including reviewing IOUs’ wildfire mitigation plans. In addition, the budget provides $2.5 million (Public Utilities Commission Public Advocates Office Account) and 14 positions to the Public Advocate’s Office for safety‑related and administrative workload, such as reviewing wildfire mitigation plans and for reviewing wildfire cost financing applications.

- CCC ($4.5 Million). The budget includes $4.5 million from the General Fund and two positions for the CCC to establish four forestry corps crews, as required by AB 2126. This includes the creation of two new crews, the conversion of an existing resource crew, and the establishment of one crew through a local corps grant.

- State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) ($4.4 Million). The budget includes $4.4 million ($2.6 million from the General Fund and $1.8 million from the Waste Discharge Permit Fund) and 22 permanent positions for SWRCB to implement various provisions in SB 901, including the development and implementation of a streamlined statewide permit to address water quality degradation that could result from increased removal of vegetation along utility corridors. The permit would provide a more streamlined process for utilities to receive necessary approvals before undertaking vegetation management projects that will be required by the new comprehensive utility wildfire mitigations plans. In addition, the budget request supports increased workload from the new small timberland owner timber harvest exemption and the expanded forest fire prevention exemption for the construction of temporary roads. Staff would be required to review exemption requests, inspect projects to ensure compliance, and develop recommendations to protect water quality.

- Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) ($3.5 Million). The Governor’s budget includes $3.5 million ($2 million from the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund and $1.5 million from the General Fund) and 15 positions for DFW to handle an increase in environmental review and permitting workload related to SB 901. Most of the positions would handle workload related to the small timberland owner timber harvest exemption and the forest fire prevention exemption for the construction of temporary roads for timber harvesting. The remaining positions would address workload for DFW to assist CalFire in providing technical assistance through the new Wildfire Resilience Program.

- CARB ($3.4 Million). The budget provides CARB with $3.4 million (GGRF) for prescribed burn smoke monitoring, forecasting, modeling, and reporting activities consistent with the requirements of SB 1260. This total includes $2 million annually for three years for local assistance grants to local air districts to provide smoke management plan reviews, provide training on the use of smoke sensors and monitors, and support other activities related to prescribed fires. The proposal also includes funding for CARB to add five new positions, as well as $595,000 in one‑time funding to purchase 10 air quality monitors and 21 smoke sensors.

LAO Assessment

Proposals Consistent With Legislation. The budget proposals to implement the 2018 legislative wildfire package appear consistent with the requirements of the various bills in the package. For example, the budget includes the two required appropriations of GGRF funds and includes funding to support legislative requirements on state agencies to implement other components of the package, such as developing new programs and regulations.

Details and Expected Outcomes for Some Proposals Are Limited. Some of the budget proposals lack important details to assist the Legislature in overseeing the ongoing implementation of the legislative package. For example, the budget proposes $165 million for forest health and fire prevention grants and related CalFire projects, but the budget details do not describe how funds would be allocated across various types of grants and programs. CalFire staff have indicated to us that the department likely will fund some direct CalFire projects and then split the remaining funding evenly between forest health and fire prevention grants. However, CalFire has also indicated that these allocations are subject to change.

Similarly, while the Governor’s budget includes the $35 million for prescribed burn crews, CalFire did not submit a detailed budget document that provides important implementation details, such as (1) information about where crews would be located in the state; (2) a time frame for the new crews to be hired, trained, and implementing new projects; and (3) estimates of how many projects and acres are expected to be treated by the crews. The proposal for the CalFire Wildfire Resilience Program also lacks key details, such as how many nonindustrial timberland owners are estimated to receive technical assistance based on the proposed level of funding and staffing for the program.

While it is understandable that some details of these new programs are still under development, the limited information on some proposals could limit the Legislature’s ability to ensure the intent of the legislative package is fully achieved and that implementation progresses along the time line assumed when the package was enacted.

Recent Electric Utility Bankruptcy Highlights Risks and Uncertainties. As mentioned above, electric utility infrastructure is often the ignition source of wildfires. As a result, IOUs have an important role in wildfire prevention, but can face financial stresses associated with wildfire risks. For example, in January 2019, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) filed for bankruptcy in large part as a result of potential costs related to recent wildfires ignited by the utility’s infrastructure. This bankruptcy raises various risks and costs for the state’s utilities, as well as other entities. For example, the bankruptcy proceedings could affect future payments received by fire victims and insurance companies, as well as costs paid by PG&E ratepayers. At this time, the magnitude of the effects is unknown. In addition, it is unclear what impacts, if any, PG&E’s bankruptcy could have on the implementation of the recent legislative package, particularly the wildfire mitigation plan required by SB 901. Moreover, the bankruptcy highlights wildfire risks and potential costs faced by other utilities in the state, as well as in other regions of PG&E’s service area. Given the health of the state’s forests, there continue to be significant wildfire risks that could be ignited by electric utility infrastructure. These risks and uncertainties further highlight the importance of ongoing legislative policy efforts and oversight.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Governor’s Budget Proposals. Overall, the requests are consistent with the package of legislation and appear to fund reasonable first steps to implementing the package. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature approve the budget proposals to implement the 2018 wildfire legislative package.

Ensure Details of Implementation Consistent With Legislative Intent. In addition, because some of the proposals implement new programs or are continuing relatively new programs, some questions about the specific implementation of the legislative package are not answered in the detailed budget documents provided. While this may be understandable, the Legislature will want to ensure it has answers to key questions about the implementation of the legislative package in 2019‑20 to ensure specific implementation decisions being made by the administration are in line with legislative intent. In particular, we recommend that the Legislature require the administration to report at spring budget hearings on the following questions:

- Forest Health and Fire Prevention Fund Allocation. How will the $165 million for forest health and fire prevention grants and fuels reduction projects be allocated among various programs? When will grants be awarded and projects underway?

- Implementation of Prescribed Burn Crews. How is CalFire progressing at hiring and training the prescribed burn crews approved in the 2018‑19 budget? Where will crews be located? How will projects be selected and prioritized? How is CalFire ensuring these crews remain dedicated to prescribed fire work year‑round without being pulled into assist with wildfire suppression?

- Wildfire Resilience Program. How many landowners are expected to receive technical assistance each year under the new program? How will the effectiveness of this program be assessed, and what outcomes does CalFire expect to achieve with the staffing level requested?

- PG&E Bankruptcy. How might the PG&E bankruptcy impact the implementation of the utility’s wildfire mitigation plan? Does the PG&E bankruptcy impact other aspects of the administration’s implementation of the legislative package?

Conduct Ongoing Oversight. Given the number of changes enacted in the legislative package, as well as the complex and long‑term challenge of improving forest health and reducing wildfire risks, it likely will take many years to evaluate outcomes of the state’s efforts. In addition, many of the requirements in the legislative package create new programs and regulatory requirements. So, it is unclear what specific implementation challenges state departments, local governments, and land owners might face in their efforts to achieve the goals of the legislation. In light of this, we recommend that the Legislature conduct ongoing oversight through future budget and policy committee hearings to monitor the state’s progress. Some key questions for future oversight include the following:

- Measuring Outcomes. How will the state measure overall outcomes in the near term and the long term? Are there ways to track the effectiveness of specific programs and regulatory changes? How will the state monitor the change in fire risk or severity in areas that have received forest health and fire prevention treatments compared to non‑treated areas?

- Allocation of Funds to Highest Priority Areas. What criteria is CalFire using to allocate funding among various regions of the state? To what extent is the department targeting dollars to the highest risk areas and/or those areas with the greatest potential public safety or environmental benefits? Is CalFire receiving a sufficient number of grant applications from the highest priority geographic areas? If not, what steps is CalFire taking to proactively work with high‑risk areas to develop potential grant projects?

- Barriers to Completing Forest Health and Fire Prevention Projects. What implementation barriers or challenges are CalFire and grant recipients experiencing with completing forest health and fire prevention projects? Does sufficient workforce capacity exist to undertake forest health and fire prevention activities at the current funding levels? Do capacity concerns constrain the ability to expand programs in the future?

- IOU Fire Prevention Efforts. How quickly are utilities conducting vegetation management projects along utility corridors? To what extent are utilities implementing the portions of the plans requiring deenergizing of electrical distribution systems and what are the impacts and outcomes? What barriers, if any, impede the ability of utilities to effectively implement wildfire mitigation plans and the ability of state agencies to oversee the implementation of these plans?

- Outcomes for Timber Harvest Exemptions. How many timber harvest exemptions are state agencies—CalFire, SWRCB, and DFW—processing? To what extent are the streamlined exemption processes resulting in more fuels reduction?

- Prescribed Burns. To what extent are additional resources for CARB resulting in more approvals for prescribed fires? How are CARB and local air districts balancing the inherent greenhouse gas (GHG) and air quality trade‑offs associated with approving prescribed burns that would have near‑term emissions? How has the burn boss certification program affected the ability of local and private entities to implement prescribed burns?

- Collaboration Across State and Local Entities. How is CalFire collaborating with other state and local entities to prioritize forest health and other wildfire reduction activities within key regions of the state? To what extent are regional planning efforts taking place, such as in key watersheds?

- Balancing Funding for Prevention Activities and Fire Response. How is the state balancing funding for forest health and fire prevention activities to reduce the risks associated with future wildfires with demands to increase funding for fire response resources necessary to respond when wildfires occur? How can the state determine where funding can be most effective? To what extent should funding priorities change in the future as wildfire risks change or if additional very severe and destructive wildfires occur?

- Overall Funding and Staffing Levels. Are funding and staffing levels sufficient to keep up with workload demands, such as for processing permit exemptions or burn boss certifications? To what extent is there ongoing or increased demand for forest health and fire prevention grants in high priority regions?

Expansion of Fire Response Capacity

The concept of increasing CalFire fire response capacity is reasonable given the increasingly severe wildfire seasons experienced in the state. We recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposals, with the exception of the proposal for C‑130 air tankers. While the overall concept of the air tanker proposal is reasonable, CalFire has not provided the necessary budget details needed to fully evaluate this proposal. As such, we recommend that the Legislature have CalFire provide additional details at budget hearings before taking an action on the request for new air tankers. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature require the administration to conduct an assessment of existing state and local fire response capacity in order to inform a multiyear approach to increasing fire response resources.

Background

The state responds to wildfires in the state responsibility area by utilizing CalFire resources (such as state and contracted fire crews, fire engines, helicopters, and air tankers), mutual aid resources (such as local fire fighters and engines), and other state resources (such as equipment and staff from the California Military Department). CalFire is currently funded to operate 343 fire engines, as well as 234 fire stations, 12 air attack bases, and 10 helitack bases.

Recent Budgets Have Augmented CalFire Response Resources. In recent years, CalFire’s base budget for wildfire response has been about $1 billion. In response to the increasingly severe fire seasons and the general need to update and modernize equipment over time, recent state budgets have increased CalFire’s wildfire response resources. For example, in 2017‑18 CalFire received $42 million to increase the availability of 42 of its fire engines into year‑round engines and extend the length of the season that helitack ground crews work. More recently, the 2018‑19 budget provided CalFire with several significant funding augmentations bringing CalFire’s base budget for fire response is $1.1 billion (mostly from the General Fund) in 2018‑19. These augmentations include:

- $315 million over multiple years to replace all 12 of CalFire’s helicopters.

- $10.9 million for heavy equipment mechanics and vehicle maintenance funding to address greater wear and tear from the lengthening fire seasons.

- $9.6 million to add five CCC crews dedicated to CalFire work, resulting in a total of seven dedicated CCC crews.

- $3 million in one‑time funding for mobile equipment (such as fire engines and bulldozers) replacements due to increased wear and tear.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget proposes $124 million for enhanced fire response capacity across multiple departments in 2019‑20. The largest share of this proposed funding is $96.9 million almost entirely from the General Fund for CalFire (offset by $1.8 million in reduced reimbursement authority for CCC) to implement several proposals as described below. Under the proposals, this funding for CalFire would increase to over $120 million in subsequent years.

- Additional Fire Engines ($40.3 Million). The budget supports adding 13 new fire engines to CalFire’s fleet, as well as 131 additional positions to staff those engines. This would bring the total size of the fleet to 356 fire engines. Under the proposal, these 13 new engines would be operated on a year‑round basis bringing the total number of fire engines operated on a year‑round basis to 65 engines.

- Increased Staffing ($15.1 Million). The budget includes two proposals to increase CalFire’s fire response staffing. First, the budget includes $10.6 million and 34 heavy equipment operator positions in order have a total of three heavy equipment operators for each of CalFire’s 58 bulldozers to provide 24 hours a day, seven days a week staffing. Second, the budget includes $4.5 million to support 13 positions to provide situational awareness staffing—dedicated staff to provide real‑time intelligence to decision makers during a wildfire.

- CCC Crews Dedicated to CalFire ($13.6 Million). The budget proposes to add five CCC crews dedicated to CalFire for fire response and prevention activities. This includes converting four existing CCC reimbursement crews into crews dedicated full‑time to CalFire work and creating one new crew dedicated to CalFire work. Under the proposal, the total number of CCC crews dedicated to CalFire will increase to 12.

- C‑130 Air Tankers and Related Capital Outlay ($13.1 Million). The budget includes funding and six positions to implement the first year of a plan to accept seven used C‑130 air tankers from the federal government to replace CalFire’s existing fleet of aircraft, with the first air tanker scheduled to be received in 2020‑21. The state will receive the aircraft for free, but the department’s costs will increase over the next several years for operating and maintenance costs. CalFire estimates annual costs will rise steadily over the next five years reaching $50 million in increased annual costs by 2023‑24. In addition, the proposed 2019‑20 funding level includes $1.7 million for the first phase of three capital outlay projects to construct barracks to accommodate the new larger flight crews needed to operate the C‑130 aircraft. These three projects along with a fourth barracks project expected to be initiated next year are estimated to cost a total of $26 million over several years.

- Employee Wellness ($6.6 Million). The budget proposes to expand two employee wellness programs. First, the budget would expand an existing health and wellness pilot program to a statewide program. The health and wellness pilot program involves conducting voluntary wellness screenings to test for health conditions common to firefighters, such as heart disease and certain types of cancer. Second, the budget increases staffing for CalFire’s Employee Support Services program that provides mental health support to CalFire employees and family members. The proposal would allow CalFire to provide more services to firefighters at the location of major fires and provide additional education and information related to post‑traumatic stress disorder.

- Fire Detection Cameras ($5.2 Million). The administration proposes to join an existing network of wildfire detection cameras and to expand the network by 100 additional cameras in locations determined by CalFire. Specifically, the funding will support a contract between CalFire and ALERTWildfire—a consortium of the University of Nevada, Reno; the University of California, San Diego; and the University of Oregon—to allow CalFire to access and control ALERTWildfire’s existing network of wildfire detection cameras.

- Mobile Equipment Replacement ($3 Million). The budget proposes to continue on an ongoing basis a one‑time 2018‑19 funding augmentation to CalFire’s budget for replacement of mobile equipment, such as bulldozers and fire engines. Funding would be used to replace additional mobile equipment that has experienced additional wear and tear from the extended fire seasons in recent years.

LAO Assessment

Increasing Fire Response Resources Is Reasonable in Concept. The magnitude and severity of recent fire seasons suggest that severe wildfires could be a worsening problem. Moreover, ongoing impacts from the drought, bark beetle infestations, tree mortality, climate change, and effects of decades of fire suppression activities all contribute to increased risks of severe wildfires. Given the recent fire conditions and the likelihood that conditions persist or even worsen, it is reasonable to increase the state’s fire response resources.

C‑130 Air Tanker Proposal Lacks Detail. As discussed later in this report, the administration typically submits detailed budget documents that provide background, justification, and fiscal details for each budget proposal. While the administration submitted these budget documents for the proposals to increase CalFire’s fire response resources, the documents lack certain details necessary to evaluate specific components of the proposals and to fully understand future costs and expected outcomes. This is particularly the case for the proposed C‑130 air tankers. For example, it is unclear why funding for maintenance and operations contracts is needed in 2019‑20 when the state is not scheduled to receive the first C‑130 air tanker until 2020‑21. Similarly, it is unclear whether current costs related to operating and maintaining CalFire’s existing air fleet (which will be decommissioned) are being netted out from the total amount of funding being requested for the new air tankers. Given the significant cost, especially in future years, to operate and maintain the C‑130 air tankers, it is important for the Legislature to have the detail necessary to understand all of the components and costs of the proposal and why each component is needed. While CalFire staff have been helpful and responsive in providing additional details on the proposals, questions regarding the air tanker proposal remain outstanding.

Administration Has Not Conducted Assessment to Inform Future Budget Decisions. In light of the state’s increasingly severe fire seasons and the trend of increasing wildfire response resources in recent budgets, we expect there will be continued pressure to expand fire response funding in the future. Having more information on existing fire response capacity and gaps in capacity would help the Legislature in its consideration of future budget proposals to increase fire response resources. However, the administration has not completed a recent assessment of state, mututal aid, and federal wildfire response capacity; potential gaps; and where additional resources would be most beneficial. Without such an assessment it is difficult to know the extent to which the specific fire response augmentations proposed address the highest priorities, fill the most critical gaps in response coverage, and take the most cost‑effective approach to addressing fire response challenges. In addition, an assessment of response capacity, gaps, and benefits could help inform future budget decisions, as well as better allow the state to develop longer‑term funding plans for the deployment of future resources to ensure that additional resources approved in the future are used in the most beneficial and cost‑effective manner.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Most of the Governor’s Budget Proposals. We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s requests for additional fire response resources in CalFire, with the exception of the proposal to support additional C‑130 air tankers. We find these proposals reasonable given the recent severe fire seasons and ongoing wildfire risks in many areas of the state.

Require CalFire to Provide Additional Information on C‑130 Air Tankers. As discussed above, the proposal for the C‑130 air tankers lacks important details, including the rationale for funding maintenance and operations contracts before the new air tankers are delivered. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature require CalFire to provide additional details on the air tanker proposal at spring budget hearings before determining what action to take on the proposal. While the overall concept of replacing CalFire’s air fleet with the C‑130 air tankers is reasonable, we think the Legislature will want to fully understand the costs of implementing this proposal before taking action on this item. To the extent the department is unable to provide sufficient justification for some components of this proposal, we would recommend the Legislature reject those components of the proposal in 2019‑20. Doing so would not impede the department’s ability to accept the C‑130s in future years or to begin the related capital projects proposed.

Require an Assessment to Inform Future Budget Decisions. In order to guide potential increases in fire response resources in future years, we recommend that the Legislature adopt supplemental reporting language to require CalFire, in coordination with the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, to provide an assessment of existing state, mututal aid, and federal fire response capacity; gaps in capacity; and where additional resources would be most beneficial. Such an assessment should evaluate state and local responsibilities, and include all types of fire response including fire engines, air attack, and other resources. The assessment should evaluate the cost‑effectiveness of increasing CalFire resources compared to increasing other resources, appropriate funding sources, goals for fire response, and expected outcomes and benefits from addressing gaps in capacity. In addition, the assessment should identify potential capital outlay needs, such as adding fire stations or helitack bases. Lastly, the assessment should prioritize identified gaps in coverage or identified demands for additional resources. We recommend that the Legislature require CalFire to submit this assessment by April 1, 2020 in order to inform potential future budget decisions related to increasing fire response capacity.

Climate Change

Cap‑and‑Trade: Revenue and Fund Condition

The Governor’s budget (1) assumes cap‑and‑trade revenue of $2.6 billion in 2018‑19 and $2.1 billion in 2019‑20; (2) proposes to spend a total of $2.4 billion in 2019‑20, including roughly $1.1 billion in discretionary expenditures; and (3) leaves less than $100 million in the GGRF at the end of 2019‑20. We estimate revenue will be roughly $800 million higher over the two‑year period and, as a result, about $450 million would remain unspent at the end of 2019‑20. There continues to be uncertainty about future revenue, making it appropriate to remain cautious when determining the overall amount of spending. However, under our revenue estimates, the Legislature could spend a somewhat higher amount in the budget year—a couple hundred million dollars, for example—and still maintain a healthy fund balance. We recommend the Legislature ensure multiyear discretionary spending commitments do not exceed $900 million annually—the maximum amount that could be supported by future revenue if recent trends in allowance prices continue. We also recommend the Legislature modify the proposed budget bill language to ensure the Legislature’s highest priorities are funded if revenue falls below projections.

In this section of the report, we assess the administration’s cap‑and‑trade revenue estimates and the overall condition of the GGRF based on total estimated expenditures in 2018‑19 and proposed expenditures in 2019‑20. In the following section, we provide a more detailed description of the Governor’s proposed cap‑and‑trade spending plan and our assessment of those specific proposals.

Background

Cap‑and‑Trade Part of State’s Strategy for Reducing GHGs. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]) established the goal of limiting GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Subsequently, Chapter 249 of 2016 (SB 32, Pavley) established an additional GHG target of reducing emissions by at least 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. One policy the state uses to achieve these goals is cap‑and‑trade. The cap‑and‑trade regulation—administered by CARB—places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from large emitters, such as large industrial facilities, electricity generators and importers, and transportation fuel suppliers. Capped sources of emissions are responsible for roughly 80 percent of the state’s GHGs. To implement the program, CARB issues a limited number of allowances, and each allowance is essentially a permit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. Entities can also “trade” (buy and sell on the open market) the allowances in order to obtain enough to cover their total emissions. (For more details on how cap‑and‑trade works, see our February 2017 report The 2017‑18 Budget: Cap‑and‑Trade.)

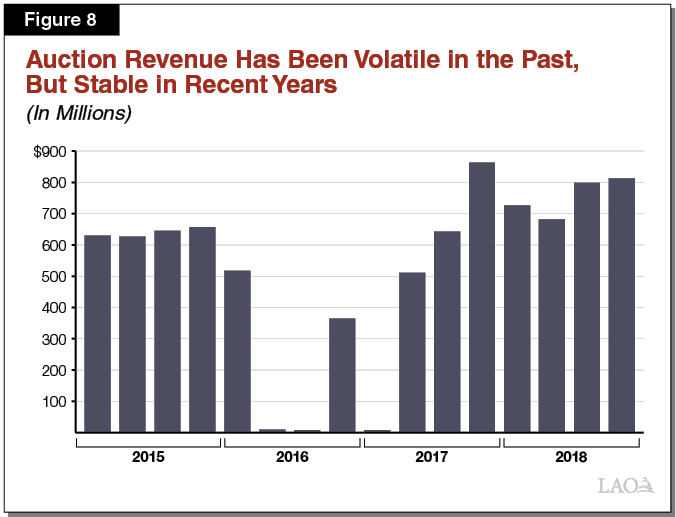

Auction Revenue Has Been Volatile in Past, but Stable Since Program Extension. About half of the allowances are allocated for free to utilities and certain industries, and most of the remaining allowances are sold by the state at quarterly auctions. The allowances offered at quarterly auctions are sold for a minimum price—set at $15.62 in 2019—which increases annually at 5 percent plus inflation. Revenue from the auctions is deposited in the GGRF.

Figure 8 shows quarterly state auction revenue since 2015. Quarterly revenue has been relatively consistent, except in 2016 and early 2017 when auction revenue dropped substantially in a few auctions. This was because very few allowances offered by the state were purchased. Several factors likely contributed to this decrease in allowance purchases, including (1) an oversupply of allowances in the market because emissions were well below program caps and (2) legal uncertainty about the future of the program. The Legislature subsequently passed Chapter 135 of 2017 (AB 398, E. Garcia), which effectively eliminated legal uncertainty about the future of the program by extending CARB’s authority to continue cap‑and‑trade through 2030. Since then, quarterly auction revenue has consistently exceeded $600 million—reaching about $800 million in the most recent auctions.

Current Law Allocates Over 60 Percent of Annual Revenue to Certain Programs. Over the last several years, the Legislature has committed to ongoing or multiyear funding for a variety of programs, including:

- “Off‑the‑Top” Allocations to Backfill Certain Revenue Losses. AB 398 and subsequent legislation allocates GGRF to backfill state revenue losses from (1) expanding a manufacturing sales tax exemption and (2) suspending a fire prevention fee that was previously imposed on landowners in State Responsibility Areas (SRA fee). Under current law, both of these backfill allocations are subtracted—or taken off the top—from annual auction revenue before calculating the continuous appropriations discussed below. These allocations are roughly $100 million annually.

- Continuous Appropriations. Several programs are automatically allocated 60 percent of the remaining annual revenue. State law continuously appropriates annual revenue (minus the backfills taken off the top) as follows: (1) 25 percent for the state’s high‑speed rail project, (2) 20 percent for affordable housing and sustainable communities grants (with at least half of this amount for affordable housing), (3) 10 percent for intercity rail capital projects, and (4) 5 percent for low carbon transit operations.

The remaining revenues—sometimes referred to as “discretionary”—are allocated through the annual budget process, and funds generally support activities intended to facilitate GHG reductions. Historically, some of these expenditures have been allocated on a one‑time basis, while other programs have been allocated funding on a multiyear basis.

Proposal

Budget Assumes $2.1 Billion of Revenue in 2019‑20. Figure 9 summarizes the Governor’s proposed framework for GGRF revenue and expenditures. The budget assumes cap‑and‑trade auction revenue of about $2.6 billion in 2018‑19 and $2.1 billion in 2019‑20. According to the Department of Finance (DOF), the 2018‑19 amount continues the revenue assumption used when the budget was adopted last year. The 2019‑20 amount is based on an assumption that all allowances offered by the state will sell at the minimum auction price.

Figure 9

Summary of GGRF Fund Condition Under Different Auction Revenue Estimates

(In Millions)

|

Governor’s Estimates |

LAO’s Estimates |

||||

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

||

|

Beginning Balance |

$620 |

$272 |

$620 |

$518 |

|

|

Revenue |

$2,675 |

$2,200 |

$3,200 |

$2,500 |

|

|

Auction revenue |

2,575 |

2,100 |

3,100 |

2,400 |

|

|

Investment income |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

Expenditures and Transfers |

$3,023 |

$2,390 |

$3,302 |

$2,569 |

|

|

“Off‑the‑top” backfillsa |

71 |

130 |

71 |

130 |

|

|

Continuous appropriations |

1,502 |

1,182 |

1,781 |

1,361 |

|

|

Discretionary expendituresa |

1,450 |

1,078 |

1,450 |

1,078 |

|

|

End Balance |

$272 |

$82 |

$518 |

$448 |

|

|

aAssumes Governor’s 2019‑20 spending proposals are adopted. GGRF = Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. |

|||||

$2.4 Billion Expenditure Plan Spends Most of Available Funds. Based on Governor’s revenue estimates, the budget allocates a total of about $2.4 billion GGRF in 2019‑20 for various programs—including off‑the‑top backfills, continuous appropriations, and discretionary spending. (We discuss the details of the expenditure plan in more detail below.) This spending comes from anticipated 2019‑20 revenue, plus some unspent funds that carryover from 2018‑19. Under the Governor’s proposal and revenue assumptions, about $80 million would remain unallocated at end of 2019‑20.

Budget Includes About $500 Million in Multiyear Discretionary Spending. Of the $1.1 billion in proposed discretionary spending in 2019‑20, almost $500 million consists of multiyear discretionary spending commitments made in past years—such as the Clean Vehicle Rebate Project (CVRP) ($200 million), forest health ($165 million), prescribed fire and fuel reduction ($35 million), and administrative costs ($60 million). Most of the remaining discretionary allocations would be on a one‑time basis.

Budget Bill Language Provides DOF Authority to Reduce Certain Allocations. Similar to last year’s budget, the administration proposes budget bill language (BBL) that (1) restricts certain discretionary programs from committing more than 75 percent of their allocations before the fourth auction of 2019‑20 and (2) gives DOF authority to reduce these discretionary allocations after the fourth auction if auction revenues are not sufficient. In addition, DOF must notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) of these changes within 30 days. This BBL is meant to ensure the fund remains solvent if revenue is lower than estimated. The allocations that DOF could reduce include air pollution reduction (AB 617) incentives, heavy‑duty and freight equipment programs, transportation equity projects, Transformative Climate Communities Program, waste diversion grants and loans, and agricultural equipment upgrades. Other discretionary programs would continue to be funded at budgeted levels under this scenario.

LAO Assessment

Revenue Likely Somewhat Higher Than Budget Assumes . . . We estimate auction revenue will be about $3.1 billion in 2018‑19 and $2.4 billion in 2019‑20—or about $800 million higher over the two‑year period. Our estimates assume that almost all allowances sell at the minimum auction price—consistent with recent market trends. Although the administration indicates that it makes a similar assumption in 2019‑20, our estimates are about $300 million higher in that year. The difference is primarily because we estimate that about 16 million more allowances will be offered during the budget year based on updated estimates of available allowances.

. . . But Revenue Uncertainty Continues. There are a wide variety of factors that contribute to revenue uncertainty. Revenue is primarily driven by demand for allowances and market prices. The overall demand for allowances and prices will depend on economic conditions, technological advancements, future regulatory actions, and market expectations about these various factors. All of these factors are highly uncertain and, as a result, revenue could be higher or lower than our projections. For example, revenue could be lower if companies do not purchase all of the allowances offered at auctions. There will be more allowances available than companies need in order to comply with the regulation in the next few years. As a result, if a sufficient number of businesses do not want to purchase and hold onto allowances for future years (also known as “banking”), then some of the allowances offered in the near term might not be purchased. On the other hand, if businesses anticipate that prices will rise substantially in the future, this could increase demand for allowances and increase near‑term prices. This could increase revenue substantially.