LAO Contact

March 15, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Increasing Compliance With

Unclaimed Property Law

Summary

Unclaimed Property in California. California law requires banks, insurance companies, and many other businesses (known as “holders”) to transfer to the California State Controller’s Office (SCO) personal property considered abandoned by owners. Most of this “unclaimed property” is cash, like uncashed checks. The state takes temporary title in these properties and maintains an indefinite obligation to reunite the property with its owners. Both holders and the state are required to notify owners about their property and attempt to reunite them with it. Funds remitted to the state but not reunited with owners provide a source of General Fund revenue, currently around $400 million per year.

Holder Compliance With Unclaimed Property Law Is Very Low. Most businesses in California fail to report unclaimed property—SCO estimates the compliance rate is about 2 percent. There are two reasons for this: (1) they are unaware of the law or (2) they are willfully noncompliant, largely to avoid the high interest penalty (12 percent annually) associated with failing to properly report.

Increasing Holder Compliance Has Merit. To increase holder compliance, the Governor proposes allocating resources to SCO for more audits of potential holders. We agree with the Governor’s goal to increase holder compliance. However, the scale of SCO’s audits cannot address the significant lack of compliance. With only a couple of dozen audits conducted each year, SCO cannot change the behavior of hundreds of thousands of California businesses.

Two Options to Address Holder Compliance. This report contains two options to try to substantially increase holder compliance with unclaimed property law. In particular we suggest the Legislature consider:

- Including an Unclaimed Property Question on Businesses’ Tax Forms. The Legislature could amend tax law to require businesses to respond to a question about unclaimed property as part of their tax filings. This question would be purely informational (it would not have tax implications for the business) and likely would significantly increase businesses’ awareness of the law.

- Providing One‑Time Amnesty for Noncompliant Holders. The Legislature also could provide one‑time amnesty for holders who voluntarily report past‑due unclaimed property by temporarily waiving the penalty associated with delinquent reports. This could be an effective way to address the problem of willful noncompliance.

The Legislature might want to consider pursuing both of these options. This would be even more effective at increasing holder compliance than either of these options alone and would avoid placing undue financial hardship on businesses. Effectively increasing holder compliance would mean more property reunited with its rightful owners and could result in hundreds of millions of dollars in General Fund benefit.

Background

Unclaimed Property Program

What Is Unclaimed Property? California law requires banks, insurance companies, and many other types of entities (known as holders) to transfer to SCO personal property considered abandoned by owners. Nearly all “unclaimed” properties are cash assets, like uncashed checks, bank accounts, payments from insurance policies, and the value of liquidated stocks and other securities. In rare cases, unclaimed property includes tangible items, like the contents of safe deposit boxes. Property is considered unclaimed if owners have had no contact with holders for a specified period of time, in many cases three years. This period without contact is called the “dormancy period” (see Figure 1). The state “escheats,” or takes temporary title in, these properties and maintains an indefinite obligation to reunite the property with owners (including heirs), should they come forward and make a claim.

Figure 1

Dormancy Period Is Three Years for Most Property Types

|

One Year |

|

Wages and salaries, such as uncashed paychecks |

|

Three Yearsa |

|

Checking and savings accounts |

|

Matured CDs and other time deposits |

|

Payable individual retirement accounts (IRAs) |

|

Stocks, bonds, dividends, and mutual funds |

|

Seven Years |

|

Sums payable on money orders |

|

Fifteen Years |

|

Sums payable on travelers’ checks |

|

aIncludes only a selection of example property types. Most other property types also fall into this category. |

Holders Must Notify Owners of Impending Escheat. State law requires holders (businesses) to notify owners their property will escheat to the state if they do not contact the holder. Holders must notify owners between six months and one year prior to the reporting deadlines described in the next paragraph. These notices contain specific information, including details about the property, a statement that the property will escheat to the state, and a form that owners can use to contact the holder to keep the property active. The reasons owners have unclaimed property vary. Sometimes owners are deceased or simply unware that the property exists.

Holders of Unclaimed Property Required to Report Annually to SCO. By November 1st of each year, holders are required to submit a holder notice report to SCO. This report details the property that has exceeded its dormancy period. SCO uses these reports to send pre‑escheat notices to owners, advising them to reestablish contact with the property. In 2016, SCO received 16,555 holder notice reports.

Property Escheats to State About Seven Months After Holder Report. If efforts by holders and SCO to prevent escheat have failed, holders must deliver unclaimed property to SCO between June 1 and June 15 (submitted with another report, called the holder remit report). State law requires holders that willfully fail to report, pay, or deliver unclaimed property to SCO to pay 12 percent annual interest on the value of the property from the date it should have been reported, paid, or delivered.

SCO Works to Reunite Property With Owners. Before and after property escheats to the state, SCO conducts a variety of activities to try to reunite owners with their property. In addition to the notices referenced earlier, SCO maintains a website for owners to search for their property, runs advertisements, and works with the Department of Veterans Affairs to send notices to veterans who appear to have unclaimed property. SCO also has a property owner advocate’s office that assists individuals in making claims. State law also allows individuals or businesses—known as investigators—to assist owners in recovering their unclaimed property and charge a fee of up to 10 percent of the value of the claim. (Our report from 2015, Unclaimed Property: Rethinking the State’s Lost and Found Program, recommended a variety of options to improve the state’s success in reuniting unclaimed property with owners.)

Holder Compliance Is Very Low

Only a Small Portion of California Businesses Are in Compliance With Holder Reports. According to SCO, only 16,555 out of about 900,000 California businesses submitted a holder report in 2016. This represents a compliance rate of about 2 percent. (SCO’s estimate of total businesses excludes self‑employed individuals and small businesses.) While this might be an imperfect measure of the number of business with unclaimed property, it strongly suggests that the vast majority of California businesses are out of compliance with unclaimed property law. Based on this, SCO has estimated that the total amount of outstanding unclaimed property that has not been properly reported by holders to the state is in the billions of dollars. Moreover, although the number of active California businesses has increased, holder reporting has declined—from nearly 23,000 holder reports received in 2011‑12 to 16,555 in 2016‑17.

Many Types of Holders and Properties Are Out of Compliance. The types of holders that do commonly submit holder reports include banks and other financial institutions, major multinational corporations, and real estate agencies. Given the very low compliance rate, there are examples of nearly all types of businesses that are out of compliance with unclaimed property law. This includes hospitals, retailers, utility companies, manufacturers, and insurance companies. Even institutions that do remit reports fail to report certain kinds of property. Some forms of unclaimed property that is under‑reported includes:

- Uncashed Checks. Other than sole proprietorships, most businesses have employees. As such, they are likely to have some form of unclaimed property, for example, in the form of uncashed checks, like paychecks. While the dollar value of a single unclaimed property might be low, in aggregate, the value of this unreported unclaimed property could be substantial.

- Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). Even though major financial institutions tend to submit holder reports to SCO, audits have revealed that these institutions still under‑report IRAs. Like other forms of property, IRAs are considered unclaimed property if an owner has not made contact with the account for three years. However, other conditions must also apply, namely that the owner must be over the age of 70.5 or the property is payable or distributable.

- “Pay‑Per‑Click” Revenue. An audit of a major California‑based technology company found that while the business was remitting holder reports to SCO, it failed to identify pay‑per‑click revenue. This is money paid to individuals for allowing advertising content on their websites. For example, one company’s policy was to only issue a check once revenues reached a certain threshold. For some individuals, reaching that threshold may take a long time and the owner may no longer be involved with account.

- Other. SCO reports that many other forms of unclaimed property are under‑reported, some specific to a particular industry. Automobile dealerships tend to under‑report customers’ deposits and Department of Motor Vehicle fees. Casinos under‑report uncollected jackpots and bonuses and expired chips. Professional sports teams often fail to report ticket refunds.

Two Main Reasons Holders Are Out of Compliance. SCO reports that there are two main reasons that businesses tend to be out of compliance. (“Out of compliance” can mean the business fails to remit a holder report entirely or fails to report a complete holder report.) In general, when holders are out of compliance it is because they either are:

- Unaware of the Law. Many businesses are simply unaware of the law regarding unclaimed property. These businesses do not to submit holder reports at all. Relatedly, businesses also may lack adequate internal procedures to remain in compliance with the law. For example, holders must track when owners are in contact with their properties either through a technological solution to automate monitoring or—for smaller businesses—manually.

- Willfully Noncompliant. Some businesses are aware of the law, but still either fail to submit holder reports or submit incomplete reports. A key reason some businesses might choose not to comply with the law is the relatively high interest rate that must be paid on properties that have not been reported.

SCO’s Efforts to Improve Holder Compliance

SCO Has Two Primary Ways to Increase Holder Compliance. SCO recognizes the holder compliance rate is very low and has made efforts to increase it. SCO has resources for two major activities related to holder compliance:

- Holder Outreach and Compliance. First, SCO established its holder outreach and compliance unit in the 2012‑13 budget to increase businesses’ awareness of and compliance with the law. This unit conducts a variety of activities, including: speaking at conferences, conducting training and workshops, and sending informational letters. SCO also works with both the California Department of Fee and Tax Administration and the Secretary of State to provide information about the law to new businesses. SCO currently has six authorized positions and $630,000 in expenditure authority for the holder compliance unit.

- Audits. Second, SCO performs audits of California businesses to ensure they are in compliance with unclaimed property law. Through the course of an audit, when SCO discovers a business has unreported unclaimed property, the business must first notify the owners about it. If an owner does not reestablish contact with the account, the holder must remit the property to SCO. In either case, the holder must pay penalty interest to the state on the unreported property. SCO also checks the businesses’ internal policies and procedures to ensure they are able to perform the necessary functions to comply with the law. SCO currently has 17 authorized positions and $2.7 million in expenditure authority to conduct these audits.

SCO Conducts About 20 Audits Per Year. Since 2013‑14, SCO has released 119 holder audit reports, an average of about 20 audits per year. Audits result in more property reunited with owners, property remitted to the state, and penalty interest revenue to the state. Figure 2 shows a recent history of the results of SCO’s holder audits. As the figure shows, audits result in somewhat more property being returned directly to owners by holders. In addition, the amount the state spends on audits each year—$2.6 million—is less than the annual amount received by the state as a result of the audits—$5.9 million (a portion of this is eventually returned by the state to owners).

Figure 2

Property Returned to Owners and Remitted to State From Recent Audits

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑14 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

|

|

Audit reports issued |

29 |

21 |

10 |

20 |

19 |

20 |

|

State |

||||||

|

Interest revenue |

$3,761 |

$2,073 |

$1,849 |

$2,980 |

$1,547 |

$1,400 |

|

Property remitted to statea |

2,146 |

3,941 |

3,195 |

2,654 |

5,326 |

4,480 |

|

Totals |

$5,907 |

$6,014 |

$5,044 |

$5,634 |

$6,873 |

$5,880 |

|

Owners |

||||||

|

Property returned to owners |

$9,392 |

$2,082 |

$95 |

$112 |

$863 |

$1,120 |

|

a A portion of the property remitted to the state is eventually returned to owners. |

||||||

Since 2013‑14, Holder Compliance Unit Has Brought Thousands of Holders Into Compliance. SCO estimates that, since 2015‑16, the holder compliance unit has brought an average of 2,200 new businesses to remit holder reports for the first time each year. SCO estimates this has resulted in an average of $57 million in cash property reunited with owners (directly by holders) and $70 million in unclaimed property remitted to the state each year.

Unclaimed Property Provides a Net Benefit to State Budget

Amount Escheated Always Exceeds Amount Reunited With Owners. Each year, the state receives unclaimed property from holders and reunites some portion of this property with its rightful owners. However, the value of property remitted to the state always exceeds the value of property reunited with owners. This difference provides a monetary benefit to the state, which first is deposited into the Unclaimed Property Fund and then transferred to the General Fund. The state uses the unclaimed property fund to finance SCO’s administrative costs to operate the program. The remainder—the amount that is not reunited with owners or used for unclaimed property administration—provides a source of General Fund revenue. This money is spent on programs throughout the General Fund budget.

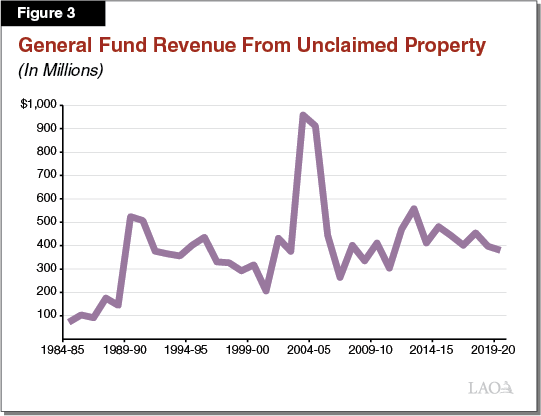

Unclaimed Property Revenue Has Remained Flat in Recent Years. Figure 3 shows the annual amount of unclaimed property revenue to the state adjusted for inflation. As the figure shows, General Fund revenue from unclaimed property has remained largely flat for a few decades, even declining slightly in recent years. (The significant spike in revenues in the mid‑2000s reflects a decision to accelerate the schedule for selling securities.) The fact that unclaimed property revenue has been largely flat in recent years is consistent with declining rates of holder reporting.

State Maintains an Indefinite Liability for Unclaimed Property. The cumulative amount of past unclaimed property that was not reunited with its owners constitutes a liability for the state. With hundreds of millions of dollars flowing to the state annually, this liability grows each year—and the cumulative total now stands at $9.4 billion. The state maintains an indefinite liability to reunite property with owners—meaning owners could one day come forward to claim any piece of this total amount. That said, the vast majority of this property will never be reunited with owners for a variety of reasons. For one, some records contain very little to no information about owners, rendering reunification with owners virtually impossible. Also, owners of properties that the state escheated long ago may have died or moved to another state, greatly diminishing the chances of reunification.

Actual Liability Much Smaller. The state’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR)—a display of the state’s finances in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles—includes an alternative estimate of the state’s unclaimed property liability. Specifically, the CAFR includes an estimate of the amount that owners will actually claim in the future based on the state’s historical experience in reuniting property with owners. The 2016‑17 CAFR reflects an unclaimed property liability of nearly $1 billion.

Governor’s Proposal and Assessment

This section summarizes the Governor’s proposal to increase unclaimed property holder compliance and provides our assessment of the proposal.

Governor Requests $1.6 Million (Unclaimed Property Fund) for 11 Positions. The Governor’s Budget proposes funding to improve holder compliance with unclaimed property law. In total, the Governor requests 11 positions and $1.6 million ongoing (Unclaimed Property Fund) to continue activities related to auditing holders for compliance. (This proposal would make permanent a similar 2016‑17 budget request plus one additional position for administration.)

Increasing Holder Compliance Increases Benefit to Owners and the State. We agree with the Governor’s goal to increase holder compliance. As discussed previously, compliance with unclaimed property law is very low. The state has the incentive to increase holder compliance for two main reasons. Increasing holder compliance would (1) result in more property being reunited with owners (both directly by holders as well as by the state) and (2) increase a source of state revenue. Measured against these goals, audits result in:

- Slightly More Property Reunited With Owners. As Figure 2 showed, since 2013‑14, SCO’s holder audits have resulted in an average of nearly $1 million in unclaimed property being reunited with owners directly by holders. That said, the magnitude of these increases is very low in the context of the overall amount of property that holders and the state reunite with owners each year. For comparison, through the course of the program’s normal operations, the state reunites a couple hundreds of millions of dollars with owners each year.

- Slightly More Unclaimed Property Remitted to the State. As Figure 2 showed, since 2013‑14, SCO’s holder audits resulted in an average of $3.6 million in unclaimed property remitted to the state and nearly $2 million in related interest payments. (A portion of the property remitted to the state as a result of audits is eventually reunited with owners.) That said, compared to existing unclaimed property revenues (nearly $400 million in 2018‑19), audit revenue of a few million dollars is very low. Overall, the General Fund revenue that results from the audits is low, but exceeds the cost of the audits.

Audits Can Only Address a Small Share of Holders Out of Compliance. The threat of a potential audit is an important incentive for businesses to comply with unclaimed property law. That said, while there are benefits to auditing holders—and the General Fund benefit of the audits exceeds the cost of conducting them—there also are clear limitations. Namely, the scale of audits cannot address the vast holder under‑compliance rate. With only a couple of dozen audits conducted each year, SCO cannot change the behavior of the hundreds of thousands of California businesses that are not complying with unclaimed property law. As such, this approach is unlikely to result in much additional compliance relative to current trends. To address this problem, the following section presents some additional policy options to try to significantly increase holder compliance.

Options to Increase Holder Compliance

This section presents some options to address the goal of substantially increasing holder compliance with unclaimed property law. As discussed earlier, there are two major reasons holders tend to be noncompliant. They are either: (1) unaware of the law or (2) willfully noncompliant, mainly to avoid interest penalties. Each of the two options in this section addresses one of these two different causes of noncompliance. As such, the Legislature could purse either or both of these options.

Include an Unclaimed Property Question on Businesses’ Tax Forms

Most California businesses file income tax returns with the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) each year. Under one option, the Legislature could amend tax law to require businesses to respond to a question about unclaimed property as part of their tax filings. This addition to tax forms could be relatively simple with a single question. For example, the tax form could ask: “Did your business submit a holder notice report to the California State Controller’s Office last year?” and indicate that the business could be out of compliance with existing law if it responds “no.” Alternatively, the tax form could include a few different questions that ask about different property types and length of time since owner contact. The adoption of this question in tax software would be critical to its effectiveness in improving compliance because so many businesses file their taxes electronically.

Option Would Address Holders’ Awareness of Unclaimed Property Law. This question would be purely informational—it would not have tax implications for the business. The main advantage of this option is that it is likely to significantly increase holders’ awareness of the law. Incorporating such a question into tax filings is likely to be much more effective at increasing compliance than notices or letters because it incorporates information about the program into a formal process that businesses participate in every year.

Resources Required. Implementing this option would require additional resources for both FTB and SCO. FTB would require additional resources primarily to handle questions from businesses generated by this new line on the form. SCO would require additional resources to process and evaluate additional holder reports and process more claims by owners. That said, the cost of these activities likely is much lower than the benefit, both in terms of the unclaimed property returned to owners and the amount of unclaimed property revenue remitted to the state. As a result, such a proposal likely would have a net benefit to the state, possibly in the hundreds of millions of dollars over time. (If this question were included on businesses’ tax forms for the 2019 tax year, increased reporting would likely begin in late 2020.)

Provide a One‑Time Amnesty for Noncompliant Holders

Another option is to provide a one‑time amnesty for holders who voluntarily report past‑due unclaimed property. Under current law, these holders owe an interest penalty of 12 percent per year for past‑due unclaimed property. This may deter some holders from becoming fully compliant, particularly because the probability of being audited is relatively low. The Legislature could temporarily waive this penalty for a certain period for holders who voluntarily report past‑due unclaimed property.

State Has Conducted a Holder Amnesty Program in the Past. The state has conducted an amnesty program for holders before. Chapter 267 of 2000 (AB 1888, Dutra), authorized a one‑year amnesty program beginning in January 2001. (The program was extended for a second year—through December 2002—by Chapter 22 of 2002 [AB 227, Dutra].) During the amnesty period, SCO conducted outreach efforts, including advertisements in national newspapers. The program resulted in 4,927 holder reports detailing 145,903 properties valued at $196 million (in nominal terms)—$113 million in cash and $83 million in securities. Of these reports, 1,567 were made by holders that had never previously filed. For comparison, this represented about a quarter of property escheated in 2000‑01 and 2001‑02.

Option Would Address Willful Noncompliance. Conducting audits—as the Governor proposes—is one way to address the problem of willful noncompliance, but it is a narrow solution to a wide‑ranging problem. Because the state only conducts a couple of dozen audits each year, businesses know that the probability of receiving an audit is relatively low. Giving businesses a temporary amnesty period to report past‑due unclaimed property could be a different—and more effective—way to address the problem of willful noncompliance, particularly among businesses that are already reporting to SCO.

Resources Required. Implementing this option would require resources for SCO—mostly on a temporary basis—to process and evaluate additional holder reports that occurred during the amnesty period. Some more resources also would be required on an ongoing basis to address higher compliance rates and more claims by owners. One way to limit the resources required would be to roll out the amnesty period at different times for different industries (say, one year for the service industry, a second year for the financial industry, and so on). That said, even if an amnesty period were pursued simultaneously for all industries, the temporary increased cost of these activities likely would be much lower than the benefit of unclaimed property returned to owners and remitted to the state. Consequently, there likely would be no net cost to the state. The state’s experience with an amnesty program in the past suggests this option alone would result in at least a couple hundred millions of dollars in additional revenue.

Both Options

Pursuing either of the options described above in isolation may be less effective than if they were implemented simultaneously. In particular, a change to tax filings might make many more businesses aware of the unclaimed property law, but they also might be reticent to participate if it means reporting years‑ or decades‑old property, carrying a very high interest penalty. Complying with these interest penalties could even result in a financial hardship for some smaller businesses. Conversely, pursuing an amnesty program without an effective way to increase businesses’ awareness of the law would not bring many new holders into compliance. As such, the Legislature might want to consider pursuing both of these options together—coupling an amnesty program with a new reporting requirement to FTB—to increase holder compliance, reunite property with its rightful owners, and result in additional General Fund benefit.