LAO Contact

Correction (5/14/19): Corrected sunset dates on certain Health and Human Services proposals.

May 12, 2019

The 2019-20 May Revision

Initial Comments on the Governor’s

May Revision

On May 9, 2019, Governor Newsom presented his first revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (This annual proposed revised budget is called the “May Revision.”) The Governor’s revised budget package provides updates on the administration’s estimates of revenues (in part based on collections in April, the state’s most important revenue collection month). The Governor’s May Revision also revises some January budgetary proposals and introduces some new proposals. In this post, we provide a summary of the Governor’s revised budget, primarily focusing on the state’s General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. (In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail and release several additional budget posts.) We begin with an overview of the overall budget condition under the May Revision estimates and proposals. Then we describe the Governor’s major budget proposals in greater detail. We conclude with our initial comments on this budget package.

The Budget’s Condition Under the May Revision

In this section, we provide an overview of the condition of the state budget under the estimates, assumptions, and proposals in the May Revision. First, we describe the changes to the administration’s revenue estimates and assumptions since the Governor’s January budget. Second, we describe the administration’s revised estimates of changes to the state’s formula-driven and other baseline costs. Finally, we describe the General Fund condition under these changes.

Revenues

Total Revenues Higher by $3.2 Billion. Compared to January, the administration’s estimates of revenues and transfers (excluding reserve deposits) have increased by $3.2 billion across the three fiscal years of 2017‑18 to 2019‑20. This upward revision is primarily the net effect of a few factors.

Higher Personal Income Tax (PIT) Revenues. Across the three years, PIT revenues are higher by $1.9 billion. Much of this increase is due to an increased capital gains estimate, which the administration has revised upward by $1.8 billion. The administration also assumes slightly stronger growth in withholding (relative to the recent trend) to account for a number of recent and planned initial public offerings of California-based businesses.

Higher Corporation Tax (CT) Revenue. Across the three years, CT revenues are higher by $1.7 billion compared to January. Much of this is the result of stronger-than-expected CT collections in April. We believe this increase in revenues likely is a one-time event in response to federal tax changes in 2017.

Some Tax Policy Changes. The increase in revenues, including in PT and CT, also reflects some changes to tax policy and assumptions about the effects of those changes. For example, the January budget reflected a “placeholder” assumption of $1 billion in revenue from the Governor’s proposal to conform with certain federal tax policy changes. The May Revision reflects a more specific estimate of $1.7 billion in 2019‑20 (declining to roughly $1.4 billion in later years). Also, the May Revision further expands the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit, reducing PIT revenues by an additional $190 million beginning in 2019‑20. Finally, the administration’s revenue estimates incorporate a modest amount of forgone revenue from a proposal to create a new, temporary sales tax exemption for menstrual products and children’s diapers.

Our accompanying post, The 2019‑20 May Revision: LAO Revenue Outlook, provides more detail on the administration’s revenue estimates and compares them to our own revenue estimates. In short, the differences between our and the administration’s revenue estimates are small through 2019‑20.

Expenditures

Constitutionally Required Spending. The budget has two key constitutional spending formulas, which require the state to spend minimum amounts in certain areas. The first—required by Proposition 98 (1988)—is a formula for determining the minimum amount of state funding for schools and community colleges. The second—required by Proposition 2 (2014)—is a formula that requires: (1) reserve deposits into a rainy day fund and (2) debt payments. The administration’s revised estimates of revenues (as well as some changes in other conditions) result in:

Proposition 98 General Fund Spending Requirement Increases by $1.1 Billion. The Proposition 98 minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges is met through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. Relative to the Governor’s January budget, required Proposition 98 General Fund spending is up $1.1 billion over the 2017‑18 through 2019‑20 period. Most of this increase is attributable to increases in General Fund revenue. The nearby box describes this requirement in more detail.

Higher Proposition 2 Requirements of $1.6 Billion. The provisions of Proposition 2 require the state to set aside a share of General Fund revenues, particularly those from capital gains taxes, for reserve deposits and debt payments. The administration’s increased estimates of revenues, particularly those from capital gains, mean the state must set aside an additional $1.2 billion for reserve deposits and nearly $400 million for debt payments in 2019‑20 (relative to the administration’s initial estimate in January).

Relatively Small Share of Proposition 98 Increase Available for New Commitments. Whereas estimates of General Fund spending have increased $1.1 billion over the period, estimates of local property tax revenue have decreased $343 million. Taken together, total funding for schools and community colleges is up $746 million relative to the Governor’s budget. The state is constitutionally required to deposit approximately half of this new funding into the Proposition 98 reserve account (discussed later in this report). Another one-third of the newly available funding covers baseline cost increases, largely related to slightly higher-than-expected student attendance. Only a small share of the funding is available for new commitments. The largest added Proposition 98 spending commitment in the May Revision is an augmentation to a January proposal related to special education. This proposal would provide grants to school districts serving large concentrations of students with disabilities, English learners, and low-income students. Whereas the Governor’s budget provided a total of $577 million for this purpose (consisting of a mix of one-time and ongoing funds), the May Revision would provide $696 million (an increase of $119 million) and make the entire allocation ongoing.

Other Baseline Cost Adjustments. We estimate that baseline costs in the budget decrease by roughly $400 million. (We consider “baseline costs” the effect of cost changes as a result of changes in caseload, price, and utilization or other factors like federal requirements.) This adjustment is the net result of a variety of factors, including the following largest adjustments:

Higher In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) Costs. Relative to January, the administration estimates underlying costs related to IHSS are higher by nearly $300 million. Much of this increase is the result of an increase in hours worked per case by IHSS service providers.

Lower Medi-Cal Costs. Although the May Revision summary references a reduction in Medi-Cal costs of nearly $1 billion in 2018‑19 and 2019‑20, much of this change is the result of costs shifting between accounting items in the budget. Consequently, net underlying programmatic costs related to the Medi-Cal program are down by a much smaller amount of over $200 million. In our The 2019‑20 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we noted that the administration did not propose renewing the managed care organization tax package. The May Revision also does not propose extending the tax package. Had the administration done so, it would have meant lower Medi-Cal costs and roughly $700 million in net General Fund benefit in 2019‑20.

Higher Department of Developmental Services (DDS) Costs. The administration now estimates baseline General Fund spending on DDS will increase by roughly $100 million. This results from higher estimates of caseload, increases in the use of certain services, and an unanticipated number of residents still living at Fairview Developmental Center.

Overall Condition of the State Budget

Governor Proposes Total Reserves of $19.5 Billion. Figure 1 shows the General Fund’s condition from 2017‑18 through 2019‑20 under the Governor’s budget assumptions (above) and proposals (which we discuss later). The Governor proposes the state end 2019‑20 with $19.5 billion in total reserves. This total would consist of (1) $16.5 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account, the state’s constitutional reserve; (2) $1.6 billion in the special fund for economic uncertainties (SFEU), which is available for any purpose including unexpected costs related to disasters; (3) $900 million in the Safety Net reserve, which is available for spending on the state’s safety net programs like CalWORKs; and (4) nearly $400 million in the state’s school reserve.

Figure 1

General Fund Condition Under Administration’s Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$5,059 |

$11,419 |

$6,224 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

131,116 |

138,046 |

143,839 |

|

Expenditures |

124,756 |

143,241 |

147,033 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$11,419 |

$6,224 |

$3,031 |

|

Encumbrances |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

|

SFEU balance |

10,034 |

4,839 |

1,646 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA balance |

$10,807 |

$14,358 |

$16,515 |

|

SFEU balance |

10,034 |

4,839 |

1,646 |

|

Safety Net reserve balance |

— |

900 |

900 |

|

PSSSA balance |

— |

— |

389 |

|

Total Reserves |

$20,841 |

$20,097 |

$19,450 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (discretionary reserve); BSA = Budget Stabilization Account (rainy day fund); and PSSSA = Public School System Stabilization Account. |

|||

State Makes First Ever Deposit Into State School Reserve. Proposition 2 established a reserve account within Proposition 98 and set forth various formulas for making deposits into the reserve. These formulas generally require the state to make deposits when (1) revenue from capital gains exceeds 8 percent of General Fund tax revenue; and (2) the Proposition 98 funding level is above the prior-year level, adjusted for changes in student attendance and a growth factor that is generally linked to increases in per capita personal income. (In addition, Proposition 2 contained a provision that effectively disallowed deposits during an initial period after voters approved the measure.) For 2019‑20, the Governor’s January budget estimated that the second condition would not be met due to strong growth in per capita personal income. Recent federal data, however, show per capita personal income growing somewhat more slowly than previously estimated. The downward revision to per capita personal income growth—combined with an upward revision to state General Fund revenue—means that this second condition is met under May Revision estimates. Under the Proposition 2 formulas, the required deposit is $389 million. This deposit counts toward meeting the Proposition 98 funding requirement in 2019‑20.

Governor’s May Budget Proposals

Budget Structure

Available Surplus Was $20.1 Billion in January. We estimate the Governor allocated $20.1 billion in available discretionary resources in January (we refer to this as the “surplus”). (In this context, we define “discretionary resources” to exclude constitutionally required spending on schools and community colleges, debt payments, and reserve deposits, as well as baseline cost changes like caseload and price-driven costs.) This surplus figure is lower than what we reflected in our report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, due in part to an accounting error in the Governor’s budget. (We discussed this error on page 7 of that report.) This significant surplus was the result of a variety of factors: (1) stronger than budgeted revenue growth, (2) lower than anticipated Medi-Cal spending, and (3) a large number of one-time spending proposals in 2018‑19.

Governor Has $800 Million in Additional Resources to Allocate in May. Despite the remarkable size of the surplus in January, the May Revision reflects a slightly better budget picture with a surplus that is larger by $800 million. This increase is the net result of a variety of factors described earlier, including somewhat higher revenues (offset by higher constitutional requirements) and slightly lower baseline spending. In addition, the May Revision reduces discretionary reserves and uses new required debt payments for a portion of the Governor’s January debt proposal. This reduction and shift in spending enables the Governor to allocate a total of $1.3 billion in new programmatic spending in May. The Governor uses this additional funding to make new programmatic commitments and modify some proposals from January. We describe the major proposals in these categories in more detail below.

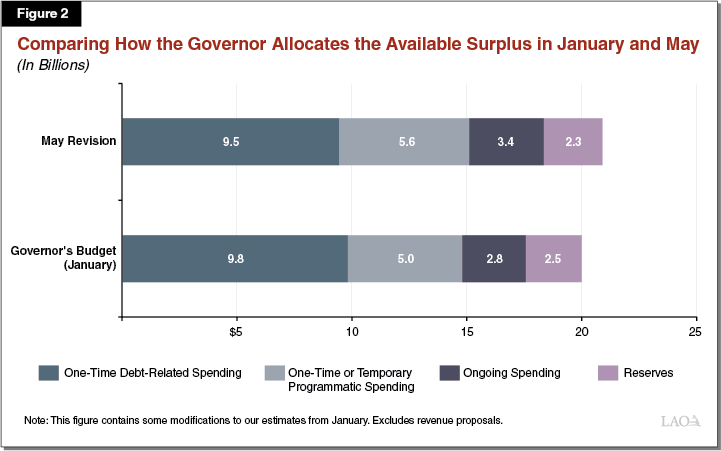

Overall Budget Structure Similar to January. Figure 2 shows how the Governor allocated the total surplus in January and May among four major categories of budget commitments: discretionary debt payments, one-time or temporary programmatic spending, ongoing programmatic spending, and discretionary reserves. Compared to January, the Governor reduces discretionary spending on debt payments, increases one-time programmatic spending, increases ongoing spending, and reduces discretionary reserves.

Governor Increases Ongoing Spending, but Proposes Sunsets for Existing Programs in 2021‑22. Compared to January, the Governor increases ongoing spending from $2.8 billion to $3.4 billion. These proposals carry “full implementation” costs of $4.4 billion. New ongoing spending later declines, however, to roughly $2.6 billion because the Governor proposes to “sunset” four major categories of program expenditures. Absent these sunsets, a structural deficit would emerge under his policy plans and revenue estimates. The Governor’s sunset proposals are:

Using Proposition 56 Funding for General Fund Cost Increases in Medi-Cal. Recent budgets have used funding from Proposition 56, which established a higher tax on tobacco products, to increase provider payments in Medi-Cal. The Governor proposes discontinuing these payment increases at the end of 2021 and instead using Proposition 56 funding in place of General Fund to cover cost growth in Medi-Cal, providing budgetary savings.

Making Restoration of IHSS Service Hours Temporary. During the last recession, the state reduced IHSS service hours by 7 percent, but the Legislature has reversed this reduction in every year since 2015‑16. Although the Governor initially planned to make the funding restoration ongoing in January, his new action would reinstate the reduction on January 1, 2022.

Making New Insurance Subsidies Temporary. The Governor has proposed a new policy to subsidize the cost of health insurance for lower-income Californians. (This proposal is coupled with a new state individual mandate that would generate penalty revenue.) The Governor proposes making these subsidies last only for three years (through 2022), although the individual mandate and associated revenue would be ongoing. (We discuss these subsidies in greater detail below.)

Making New Supplemental Rate Increases for Developmental Services Providers Temporary. The Governor proposes sun-setting one of his proposed augmentations in 2019‑20—rate increases for certain DDS providers. (We discuss this augmentation in greater detail below.)

Altogether, these sunsets would reduce ongoing General Fund spending by $1.8 billion in the next couple of years.

Changes to January Proposals

The May Revision makes a number of modifications and refinements to discretionary General Fund spending proposals from January. Figure 3 summarizes these major changes. The net effect of these changes increases spending by $345 million. In this section, we describe some of the key changes.

Figure 3

Modifications to Discretionary General Fund Programmatic

Spending Proposals From Governor’s January Budget

(Change in Costs, in Millions)

|

Health |

|

|

Funding to create new state insurance subsidies |

$295.3 |

|

Expanding Medi‑Cal benefits to undocumented young adults (make half‑year) |

‑121.9 |

|

Other revisions to health proposals |

0.7 |

|

Housing and Homelessness |

|

|

Repurpose $500 million in housing production grants for infill infrastructure grant program |

— |

|

Additional funding for homelessness programs |

$150.0 |

|

Education and Child Care |

|

|

Additional pension rate relief for schools and community colleges |

$150.0 |

|

Kindergarten facility grants (reduce proposed funding level) |

‑150.0 |

|

Full‑day state preschool slots (start slots later in year) |

‑93.5 |

|

Cal Grants for students with children (update cost estimate) |

‑25.0 |

|

Other revisions to education and child care proposals |

5.6 |

|

Human Services |

|

|

Revisions to IHSS county maintenance‑of‑effort |

$55.0 |

|

Changes to county single allocation |

41.4 |

|

Other revisions to human services proposals |

32.6 |

|

Criminal Justice |

|

|

Additional funding for CalVIP |

$18.0 |

|

Other revisions to criminal justice proposals |

‑9.0 |

|

Other |

‑$3.8 |

|

Total |

$345.0 |

|

IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services and CalVIP = California Violence Intervention Program. Note: Excludes constitutional spending requirements and some smaller proposals. |

|

Clarifies Details for Health Insurance Mandate Penalty and Subsidies Proposal. The May Revision provides details on a January proposal to impose a state individual mandate and use the resulting penalty revenues to subsidize the cost of insurance for qualifying individuals. Both the individual mandate and insurance subsidies would be implemented beginning in January 2020. Subsidies would be available for three years. The Governor proposes to provide relatively larger subsidies to households with incomes between 400 percent and 600 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) that currently do not receive federal insurance subsidies. Relatively smaller subsidies would be provided for households with incomes between 200 percent and 400 percent of the FPL that currently do qualify for federal subsidies. (The original January proposal did not include subsidies for those with income between 200 percent and 250 percent of the FPL.)

The individual mandate proposal would be ongoing. Because penalties would not be paid until 2021 (when filers pay their 2020 taxes), the General Fund would cover the first year of subsidies’ cost in 2019‑20, estimated at $295 million. The General Fund would be reimbursed in 2022‑23 when the subsidies end but penalty revenue continues to be collected.

Changes Approach to Housing and Homelessness Proposals. The Governor proposes significant changes in the May Revision to three major components of the housing and homelessness package introduced in January. First, in January, the Governor proposed making an additional $500 million available to cities and counties for general purposes as an incentive to meet their short-term housing goals. The May Revision repurposes these funds for the Infill Infrastructure Grant Program, which provides funding for infrastructure projects that support high-density affordable and mixed-income housing in locations designated as infill. Second, the May Revision increases the proposed grants to local governments for homelessness from $500 million to $650 million and updates the allocation and eligible uses of the grant funding. Third, in January, the Governor proposed making $250 million available to cities and counties to help them meet new short-term housing production goals. The May Revision also makes schools and county offices of education eligible for a portion of these funds.

Adjusts Early Education Proposals. The May Revision reduces the Governor’s January proposal to provide one-time General Fund for kindergarten facility grants from $750 million to $600 million. The May Revision also extends the grant funding through 2021‑22, initially limiting funding to those school districts that plan to convert their part-day kindergarten programs into full-day programs. In addition, the May Revision reduces State Preschool funding by $93 million to account for starting the 10,000 proposed new slots in April 2020 rather than July 2019 as originally proposed. The administration also withdraws its plan to fund State Preschool for all income-eligible four-year olds by 2021‑22, citing concerns about the state’s multiyear fiscal situation.

New Budget Proposals in May

In addition to modifying some proposals from January, the Governor puts forward a number of new discretionary General Fund proposals in the May Revision. The total cost of these new proposals is nearly $1 billion, with about two-thirds devoted to one-time or temporary proposals and one-third to ongoing proposals. Some of the larger proposals are summarized in Figure 4 below and highlighted in this section. (These estimates reflect the cost of the May Revision proposals in 2019‑20, but some of these costs grow in future years.)

Figure 4

Major New Discretionary General Fund Programmatic

Spending Proposals in May Revision

(Cost in 2019‑20, in Millions)

|

One Time or Temporary |

Ongoing |

|

|

Education |

||

|

Grants for teachers working in shortage areas |

$89.8 |

— |

|

Teacher training |

44.8 |

— |

|

Other education proposals |

27.7 |

$11.1 |

|

Human Services |

||

|

Supplemental rate increases for DDS providersa |

— |

101.2 |

|

Allow CalWORKs recipients to receive Stage 1 for 12 months |

— |

40.7 |

|

Retain, recruit, and support foster parents |

21.6 |

— |

|

Suspend the DDS Uniform Holiday Schedulea |

— |

30.1 |

|

Other human services proposals |

9.4 |

3.6 |

|

Criminal Justice |

||

|

Implement integrated substance use disorder treatment at CDCR |

— |

71.3 |

|

Additional superior court judgeships |

— |

30.4 |

|

Legal aid for renters in landlord‑tenant disputes |

20.0 |

— |

|

Other criminal justice proposals |

15.0 |

19.6 |

|

Emergencies and Environment |

||

|

Improve resiliency of state’s infrastructure/various (power shutdown resiliency) |

75.0 |

— |

|

Harbors and Watercraft and State Parks Recreation Fund Stabilization |

26.0 |

9.7 |

|

Surge capacity for disasters |

20.0 |

— |

|

Other emergencies and environment proposals |

53.6 |

14.2 |

|

General Government |

||

|

Replace and upgrade voting systems |

87.3 |

— |

|

Fund the Department of General Services to maintain Sonoma Developmental Center |

21.1 |

— |

|

Other general government proposals |

52.8 |

17.8 |

|

Health |

||

|

Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control |

40.0 |

— |

|

Other health proposals |

— |

16.4 |

|

Totals |

$604.0 |

$357.0 |

|

a Although the Governor provides funding for these proposals on a temporary basis, as we discuss in this report, we treat them as ongoing because they are addressing ongoing cost pressures. Note: Excludes constitutional spending requirements and some smaller proposals. UCRP = University of California Retirement Plan; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; CalWORKs = California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids; and CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Provides $135 Million One Time for Teacher Initiatives. The May Revision includes $90 million to provide 4,500 teachers up to $20,000 in grants for teaching in certain schools and subject areas (generally those that have high rates of teachers on temporary licenses). The May Revision also includes $45 million for teacher training initiatives focused on various areas, including computer science, social emotional learning, and subject matter competency.

Provides $100 Million for a Supplemental Rate Increase for DDS Providers. The Governor proposes allocating roughly $100 million in 2019‑20 to provide a supplemental rate increase for DDS providers in certain service categories. The rate increases would take effect January 1, 2020. The full-year cost of these increases is about $200 million. The decision about what service categories to supplement were informed by findings from a recent rate study. Under the Governor’s multiyear plan, these increases would be on a temporary basis, ending after December 31, 2021.

Provides Ongoing Funding for Substance Use Disorder Treatment and Additional Judgeships. The Governor proposes $71.3 million from the General Fund (increasing to $164.8 million annually in 2021‑22) to implement an integrated substance use disorder treatment program. This program includes medication assisted treatment and an overhaul of existing cognitive behavioral therapy programs. The Governor also proposes $30.4 million in General Fund (increasing to $36.5 million annually in 2020‑21) to support 25 new trial court judges and associated court staff. These resources would be distributed to those courts with the greatest judicial need based on their workload as identified in the judicial branch’s needs assessment.

LAO Comments

Budget Proposals

Governor Took Steps to Improve Some January Budget Proposals . . . In January, after the Governor released his proposed budget, we noted that many of his budget proposals were “still under development.” The Governor has now taken steps to provide more detail on some of these proposals. For example, the Governor provided detail on the state individual mandate and health insurance subsidies. He also took an intermediate step toward expanding the state’s paid family leave program. In addition, the Governor’s decision to redirect $500 million to infill infrastructure to support housing may be a more effective approach for increasing housing development across the state.

. . . But Some Proposals Still Lack Important Detail. That said, many of the Governor’s budgetary proposals from January still lack important details. For example, the Governor’s goal to create a state Opportunity Zone program to complement the federal policy lacks basic information on policy design and structure. Moreover, the Governor has introduced some new proposals in May that seem promising, but the Legislature has limited time to consider. For instance, the Governor’s proposal to identify surplus school district property for teacher housing lacks detailed information or analysis.

Budget Structure

Governor Generally Maintains Budget Structure From January. The Governor does not make major revisions to the overall structure of the January Governor’s budget in the May Revision. In particular, the Governor still proposes allocating about half of discretionary resources to repaying some state debts. Notably, the Governor continues to propose dedicating $3 billion to reduce the state’s California Public Employees’ Retirement System unfunded liability—a proposal we think is prudent. Also, although the Governor allocates less in discretionary resources to reserves ($2.3 billion rather than $2.5 billion), total reserves increase by $1 billion compared to January (because the state is required to deposit more money into reserves under the rules of Proposition 2). The administration also takes the notable step of making the first ever deposit of nearly $400 million into the state’s school reserve—better positioning schools to weather a recession.

Proposed Level of Reserves Approach Lower End of Advised Range. Based on the experience of recent recessions, we estimate the state would need about $20 billion in reserves to cover a budget problem associated with a mild recession and $40 billion to cover a moderate recession. In last year’s Fiscal Outlook publication, we found $3 billion in ongoing commitments were supportable in a recession scenario, assuming the state entered the recession with $25 billion in reserves. This is roughly $6 billion more in reserves than the $19.5 billion currently proposed by the Governor. While the state could rely on internal borrowing—as was done during the Great Recession—these practices create new debts the state must repay and can impair the operations of some state programs. (Moreover, the Governor’s proposal to set the level of the SFEU to $1.6 billion is lower than the amount that has been required in recent years to respond to disasters.) As such, we advise the Legislature consider building more reserves than currently proposed by the Governor. Given the extraordinary scale of the surplus currently available, we think the state should seize this unique opportunity to robustly prepare for a recession now.

Budget-Year Costs Do Not Reflect Full Extent of Commitments. The Governor makes a number of policy proposals in the May Revision without reflecting the full cost of those commitments. In order to maintain a balanced budget through the forecast period ending in 2022‑23, the Governor sunsets a variety of budget-year proposals. (Each of these commitments have different historical circumstances, but nevertheless reflect estimated costs to maintain current service levels.) We have a number of concerns with this approach. In particular, the Governor chooses to treat policies that are fundamentally ongoing in nature as temporary, which creates programmatic challenges and increases cost pressures. This approach implicitly prioritizes new ongoing spending proposals—such as increases for the universities, that do not sunset—largely at the expense of existing programmatic commitments. Consequently, we think this May Revision understates the true ongoing cost of its policy commitments.

Multiyear Budget Analysis Will Be Particularly Important This Year. The May Revision somewhat increases ongoing spending compared to the January Governor’s budget (setting aside the ostensible plan to sunset some expenditure items described earlier). Specifically, the May Revision commits $3.4 billion in new ongoing spending in 2019‑20—with costs increasing to $4.4 billion in full implementation. This is a significantly higher level of new ongoing spending than recent budgets. It also is somewhat higher than the capacity we thought was available when we released our Fiscal Outlook in November.

In the coming week, we will conduct our multiyear budget analysis of the May Revision proposals. This report will provide our assessment—using our revenue estimates—of whether the state budget has the capacity for the May Revision proposals. Given the higher level of ongoing spending proposed in this budget, we think the results of this analysis will be particularly critical this year as the Legislature evaluates the Governor’s budget package.