December 17, 2019

How High?

Adjusting California's Cannabis Taxes

Also see this ![]() Summary Fact Sheet for the report

Summary Fact Sheet for the report

- Introduction

- Background

- Effects of Tax Rate Changes on Legal and Illicit Markets, Tax Revenue, and Youth Use

- Considering Other Potential Changes to Cannabis Taxes

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Executive Summary

Report Required by Proposition 64. Proposition 64 (2016) directed our office to submit a report to the Legislature by January 1, 2020, with recommendations for adjustments to the state’s cannabis tax rate to achieve three goals: (1) undercutting illicit market prices, (2) ensuring sufficient revenues are generated to fund the types of programs designated by the measure, and (3) discouraging youth use. This report responds to this statutory requirement and discusses other potential changes to the state’s cannabis taxes. While this report focuses on cannabis taxes, nontax policy changes also could affect these goals.

Proposition 64 Created Two State Excise Taxes on Cannabis. Proposition 64 established two state excise taxes on cannabis. The first is a 15 percent retail excise tax, effectively a wholesale tax under current law. The second is a tax based on the weight of harvested plants, often called a cultivation tax. (The measure authorizes the Legislature to amend its tax provisions without voter approval, but the scope of this authorization is unclear.)

Analysis

Choices About Tax Structure Should Precede Choice of Tax Rate. Before determining the specific tax rates to impose, we encourage the Legislature first to address two critical decisions: (1) choosing what type of tax to impose on cannabis, and (2) choosing which type of transaction to tax (known as the “taxed event”) and who should remit the tax (known as the “point of collection”). These choices can have effects on the three goals identified by the measure as well as other important considerations.

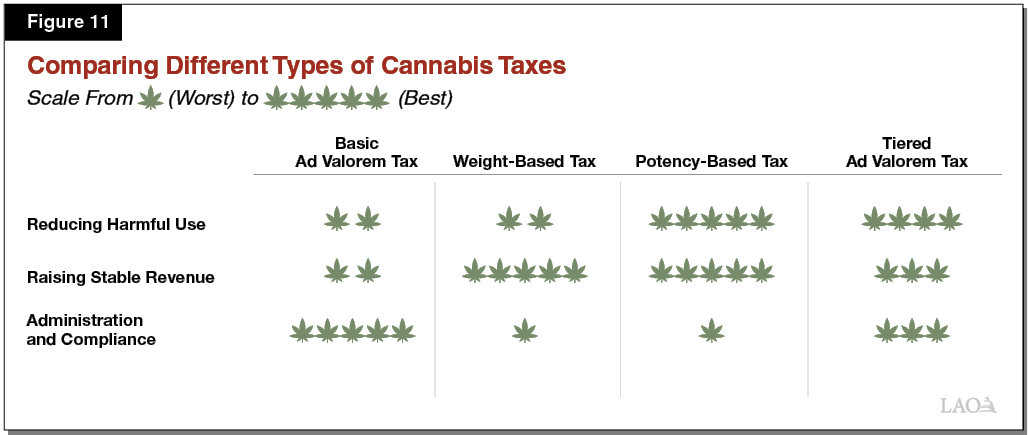

Trade‑Offs Exist Among Tax Types, but Weight‑Based Taxes Generally Weakest. We analyze four types of taxes: basic ad valorem (set as a percentage of price, such as the current retail excise tax), weight‑based (such as the current cultivation tax), potency‑based (for example, based on tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]), and tiered ad valorem (set as a percentage of price with different rates based on potency and/or product type). Our analysis focuses primarily on three main criteria: (1) effectiveness at reducing harmful use, (2) revenue stability, and (3) ease of administration and compliance. No individual type of tax performs best on all criteria. For example, tiered ad valorem and potency‑based likely are best for reducing harmful use, but basic ad valorem is easiest to administer. Given these trade‑offs, the Legislature’s choice depends heavily on the relative importance it places on each criterion. That said, the weight‑based tax is generally weakest, performing similarly to or worse than the potency‑based tax on the three main criteria.

Choice of Taxed Event and Point of Collection Depends on Type of Tax. We assess several options for specifying the tax event and point of collection for state cannabis taxes. Tax administration and compliance work best when the connection between the taxed event and the point of collection is very close, when taxpayers are highly visible to the public, and when there is a small number of taxpayers.

Rate Changes Would Create Trade‑Offs Among Three Goals. Any tax rate change would help the state meet certain goals while likely making it harder to achieve others. On one hand, for example, reducing the tax rate would expand the legal market and reduce the size of the illicit market. On the other hand, such a tax cut would reduce revenue in the short term, potentially to the extent that revenue could be insufficient. Furthermore, lower tax rates could lead to higher rates of youth cannabis use. With a thriving illicit market, however, much of the cannabis used by youth could avoid taxation. Where possible, this report provides quantitative estimates of the short‑term effects of rate changes. We summarize these estimates—along with assessments of revenue sufficiency—in the figure below.

Recommendations

Replace Existing Taxes with Potency‑Based or Tiered Ad Valorem Tax. We view reducing harmful use as the most compelling reason to levy an excise tax. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature replace the existing retail excise tax and cultivation tax with a potency‑based or tiered ad valorem tax, as these taxes could reduce harmful use more effectively. If policymakers value ease of administration and compliance more highly than reducing harmful use, however, the Legislature might prefer to keep the existing retail excise tax. In contrast, we see little reason for the Legislature to retain the weight‑based cultivation tax.

Specify Taxed Event and Point of Collection to Match Type of Tax. After the Legislature chooses the type of cannabis tax it wants to levy, we recommend that it specify the taxed event and point of collection to facilitate tax administration and compliance. For example, for an ad valorem tax (tiered or basic), we recommend levying the tax on the retail sale and collecting it from the retailer.

Set Specific Tax Rate. For a potency‑based or tiered ad valorem tax, we recommend that the Legislature specify the details of the tax structure in consultation with scientific experts. Such expertise—informed by the state’s track‑and‑trace data—is crucial for determining key details. Currently available information suggests that a potency‑based tax in the range of $0.006 to $0.009 per milligram of THC could be appropriate. If the Legislature prioritizes reducing the illicit market, it may prefer a rate closer to the lower end of this range. If, on the other hand, it prioritizes raising revenues, it may prefer a rate closer to the higher end.

If the Legislature decides not to adopt a potency‑based or tiered ad valorem cannabis tax, we nevertheless recommend that the Legislature eliminate the cultivation tax. In this case, we recommend that the Legislature set the retail excise tax rate somewhere in the range of 15 percent to 20 percent depending on its policy preferences.

Estimated Short‑Term Effects of Rate Changes on Legal Consumption and Revenue

|

Cultivation Tax |

Retail Excise Tax |

Likely Short‑Term Percentage Change in |

Likelihood Revenue Would Exceed Thresholdb |

|

|

Legal Cannabis Consumption |

State Cannabis Tax Revenuea |

|||

|

Keep at current ratesc |

Keep at current rate (15%) |

0% |

0% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

Eliminate |

Reduce to 11% |

+6% to +20% |

‑34% to ‑43% |

Likely to fall short |

|

Eliminate |

Keep at current rate (15%) |

+3% to +11% |

‑16% to ‑25% |

Roughly equal chances of exceeding and falling short |

|

Eliminate |

Increase to 20% |

‑2% to +1% |

‑5% to +3% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

Keep at current rates |

Increase to 25% |

‑7% to ‑22% |

+18% to +40% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

aUnder current law, we expect state cannabis tax revenue to be in the mid‑hundreds of millions in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. bSome provisions of Proposition 64 imply that revenue below $350 million in 2021‑22 would not be sufficient. cAs of January 1, 2020, the cultivation tax rates are $9.65 per ounce of dried cannabis flowers, $2.87 per ounce of dried cannabis leaves, and $1.35 per ounce of fresh cannabis plants. |

||||

Introduction

In November 2016, California voters approved Proposition 64, which legalized the nonmedical use of cannabis (typically called recreational or adult use) and created a structure for regulating and taxing it. Proposition 64 also directed our office to submit a report to the Legislature by January 1, 2020, with recommendations for adjustments to the state’s tax rate on cannabis to achieve three goals: undercutting illicit market prices, ensuring sufficient revenues are generated to fund the types of programs designated in the measure, and discouraging use by persons younger than 21 years of age. This report responds to that requirement. Specifically, we provide (1) background information on cannabis and its legalization in California, (2) a discussion of the effects of adjusting the tax rate, (3) an assessment of other potential changes to California’s cannabis tax structure, and (4) recommendations for the Legislature.

Background

Understanding the Cannabis Plant and its Effects

Cannabis Plant Contains Various Compounds. The cannabis plant contains a variety of compounds known as cannabinoids. While there are over 100 known cannabinoids, the most well‑known cannabinoids are tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Experts regard THC as the primary psychotropic component of cannabis, responsible for much of the intoxicating “high” reported by cannabis users. In contrast, CBD generally is understood not to be intoxicating. Depending on factors such as the specific strain of the cannabis plant, as well as growing and harvesting conditions, some cannabis plants have much higher levels of THC and/or CBD than others. Very low‑THC cannabis is often regarded as a distinct crop known as “hemp.” Hereafter, we use the term “cannabis” to refer to the non‑hemp, generally higher‑THC version of the plant, and to the products made from it.

Wide Variety of Cannabis Products Available. Historically, the most common method for consuming cannabis has been smoking the plant’s flower. While this is still very common, there also are a variety of other types of cannabis products. Such products include edibles (such as candy and beverages), concentrates (such as “wax”, which has a texture similar to candle wax), vapor cartridges, and topicals. These products have different properties, such as the amount of time until they take effect, the duration of their effects, the concentration of THC in the product (commonly known as “potency”), and the amount of THC ultimately absorbed by the body. For example, it generally takes longer for users to feel the effects of edible cannabis products than smoked products, and the effects of edibles tend to last longer. Additionally, concentrates are typically much more potent than flower (on average around 70 percent THC compared to around 20 percent THC). Some cannabis products contain significant amounts of CBD but very little THC.

Cannabis Has Become More Potent Over Time. Evidence suggests that the average potency of cannabis has increased in recent years. There appear to be two contributing factors to the increase in potency. First, cultivators have bred cannabis plants for higher THC concentrations. Second, concentrates and other high‑potency products make up an increasing share of the cannabis market.

Key Effects of Cannabis. Researchers’ current understanding of the health effects of cannabis is far from complete. That said, evidence indicates that cannabis provides health benefits to those with certain conditions, such as chronic pain and nausea from chemotherapy. However, there also is evidence of potential harms from cannabis use. For example, some research suggests links between cannabis use and psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia. Additionally, cannabis use can impair driving, particularly when combined with alcohol use. In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine assessed the available research on the effects of cannabis. Figure 1 summarizes some of the key findings of that report. The negative effects of cannabis appear to be greatest for high‑THC products, high‑frequency use, and use by certain sensitive groups, such as youth.

Figure 1

Summary of Cannabis’ Effects and Associations

As Assessed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicinea

|

Conclusive Evidence |

Substantial Evidence |

|

|

Effective treatment for: |

||

|

Chemotherapy‑induced nausea and vomiting |

✔ |

|

|

Chronic pain treatment in adults |

✔ |

|

|

Patient‑reported multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms |

✔ |

|

|

Statistical association between cannabis or cannabinoid use andb: |

||

|

Development of schizophrenia or other psychoses |

✔ |

|

|

Worse respiratory symptoms and more chronic bronchitis episodes (long‑term smoking) |

✔ |

|

|

Increased risk of motor vehicle crashes |

✔ |

|

|

Lower birth weight of offspring with maternal smoking |

✔ |

|

|

aDoes not include effects and associations that were assessed to have no evidence, limited evidence, insufficient evidence, or moderate evidence. bStatistical association does not necessarily suggest a causal relationship. |

||

Cannabis Legalization in California

Under federal law, it is illegal to possess or use cannabis. Currently, the U.S. Department of Justice (US DOJ) does not prosecute most cannabis users and businesses that follow state and local cannabis laws if those laws are consistent with US DOJ priorities, such as preventing cannabis from being exported to other states. Despite federal law, California and many other states have taken steps to legalize and regulate cannabis in the past few decades. However, these states have not been able to include exported cannabis in these efforts due to federal prohibitions. In California, exports likely account for a large share of California‑grown cannabis—roughly 80 percent by some recent estimates.

Proposition 215 (1996) Legalized Medical Cannabis. In 1996, California became the first state to legalize cannabis for medical use when voters approved Proposition 215. While Proposition 215 legalized the medical use of cannabis, it did not create a statutory framework for regulating or taxing it. As a result, for roughly 20 years after the measure passed, most regulation and taxation of medical cannabis in California happened at the local level through ordinances and permit requirements. (Like other businesses, medical cannabis businesses were subject to broad‑based state taxes, such as income taxes and sales taxes.) In recent years, the Legislature passed a series of laws—most notably, in 2015, Chapter 688 (AB 243, Wood), Chapter 689 (AB 266, Bonta), and Chapter 719 (SB 643, McGuire)—to provide a statutory framework to regulate medical cannabis.

Proposition 64 Legalized Adult‑Use Cannabis. In November 2016, California voters approved Proposition 64. At the time, Washington, Colorado, Oregon, and Alaska were the only states that had legalized cannabis for adult use. Under Proposition 64, adults 21 years of age or older can legally grow, possess, and use cannabis for nonmedical purposes, with certain restrictions. Since the passage of Proposition 64, the Legislature has passed laws amending the measure, including Chapter 27 of 2017 (SB 94, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), which brought the state’s medical and adult‑use regulatory structures into conformity.

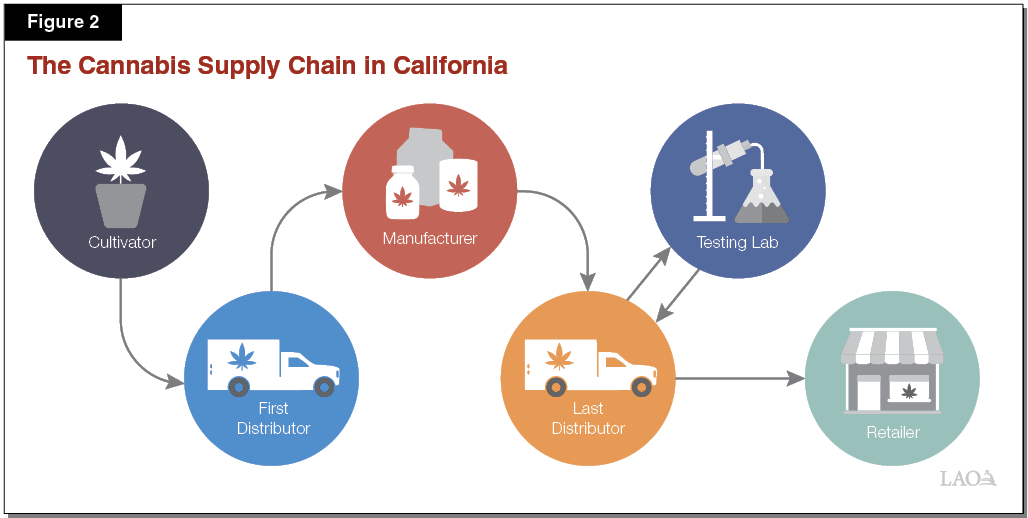

Current Structure for State Cannabis Regulation and Taxation. Under Proposition 64, state agencies issue licenses to several types of cannabis businesses, including cultivators, manufacturers, distributors, testing labs, and retailers. (The relationships among these businesses can vary; Figure 2 illustrates an example.) To hold a state license, cannabis businesses must pay fees and meet numerous other requirements, including ones related to security protocols, product testing, and product labeling. For example, cannabis products must be tested for THC and CBD content before the last distributor transfers the products to the retailer. Additionally, state‑licensed businesses must participate in the state’s “track‑and‑trace” system by attaching unique identifier tags (similar to bar codes) to each plant and product. These tags allow the state to track the movement of cannabis products through the entire supply chain, from cultivation all the way to retail sale.

Local Governments May Regulate, Ban, and Tax Cannabis. Proposition 64 authorizes local governments to impose requirements on cannabis businesses, to limit where they can locate, or to ban them altogether. Additionally, local governments may impose fees and taxes on cannabis, which we discuss further below.

Legislature May Make Some Changes to the Measure. The California Constitution does not allow the Legislature to amend a measure passed by the voters unless the measure itself authorizes the Legislature to do so. Proposition 64 authorizes the Legislature to amend the measure’s tax provisions with a two‑thirds vote. These changes must be consistent with the measure’s intent and further its purposes. In many cases, whether a proposed change to Proposition 64 would meet these criteria and, therefore, whether the Legislature could enact it without a statewide vote is unclear.

State Cannabis Taxes and Revenue Distribution Under Proposition 64

Proposition 64 Imposes Two State Excise Taxes on Cannabis. Like other businesses, cannabis businesses generally must pay broad‑based taxes such as income taxes and sales taxes. (We further discuss sales taxes on cannabis in the nearby box.) Additionally, as shown in Figure 3, Proposition 64 established two state excise taxes on cannabis. The first is a 15 percent excise tax on retail gross receipts. The second is a cultivation tax on harvested plants. As of January 1, 2020, the cultivation tax rates are $9.65 per ounce of dried flowers, $2.87 per ounce of dried leaves, and $1.35 per ounce of fresh plants. The California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA), which administers these cannabis taxes, adjusts the cultivation tax rates annually for inflation.

Sales Taxes on Cannabis

Sales Taxes Apply to Tangible Goods, Including Cannabis. California’s state and local governments levy a sales and use tax (commonly known as a sales tax) on retail sales of tangible goods. The rate varies across the state, ranging from 7.25 percent to 10.5 percent, with a statewide average of 8.6 percent. Cannabis products are tangible goods, so their retail sale generally is subject to this tax.

Legislative Analyst’s Office Definition of Cannabis Taxes Does Not Include Sales Tax. We define cannabis taxes to include taxes or tax rates that apply primarily to cannabis. We chose this definition—which does not include the sales tax—for two reasons. First, as discussed in our 2018 report, Taxation of Sugary Drinks, changes in excise tax rates, such as cannabis tax rates, primarily affect the price of one specific type of good relative to the prices of other items that consumers buy. The sales tax applies to a wide range of goods, so it does not have this property. Second, as described above, Proposition 64 (2016) requires that state cannabis tax revenues be allocated to purposes specified by the measure. In contrast, sales tax revenue goes to the state’s General Fund and to local programs, regardless of whether that revenue comes from cannabis sales or sales of other goods.

Figure 3

California’s Cannabis Taxes

|

Tax |

Type |

Rate on January 1, 2020 |

|

State retail excise tax |

Ad valorem tax primarily on wholesale sales |

Nominally 15 percent of retail price. In practice: |

|

||

|

State cultivation tax |

Weight‑based tax on harvested cannabis |

|

|

Local taxes |

Varies; most commonly ad valorem or based on square footage |

Varies—on average, roughly equivalent to a 14 percent tax on retail salesa |

|

aLAO estimate of the average cumulative tax rate, including taxes on cultivation, manufacturing, distribution, testing, and retail. |

||

Distributors Responsible for Remitting State Taxes. Cultivators and retailers bear the legal responsibility for the initial payment of the cultivation and retail excise taxes, respectively. However, pursuant to Chapter 27, final distributors—rather than cultivators or retailers—must remit these taxes to CDTFA, resulting in a multistep payment process. We explain this process below and illustrate how it works for a hypothetical manufactured product in Figure 4.

- Cultivation Tax. A cultivator determines the amount of cultivation tax it owes by weighing the plants it harvests. It then pays this amount to a distributor when it sells or transfers the harvested plants. In a case in which cannabis travels from the cultivator to just one distributor prior to retail sale, that distributor remits the tax to CDTFA. In many cases, however (such as the case illustrated in Figure 4), the supply chain is more complex, with multiple manufacturers and distributors handling harvested cannabis and the products derived from it. In these cases, each of those businesses must transfer the cultivation tax until the final distributor remits it to CDTFA.

- Retail Excise Tax. Retailers generally must pay the retail excise tax to final distributors when they make wholesale purchases. These distributors then remit the retail excise taxes to CDTFA. Retailers must make these payments before they sell the products to consumers, so the tax is based directly on the wholesale price (the price that retailers pay to distributors) rather than the retail price (the price that consumers pay to retailers). Pursuant to Chapter 27, CDTFA sets the tax based on its estimate of the average ratio of retail prices to wholesale prices—commonly known as a “markup.” CDTFA’s current markup estimate (as of January 1, 2020) is 80 percent. Due to the 15 percent statutory tax rate and the 80 percent markup estimate, the current effective tax rate on wholesale gross receipts is 27 percent (15 percent x [100 percent + 80 percent]).

Revenues Go to Three Types of Activities. The state deposits the revenues from the two cannabis taxes into the Cannabis Tax Fund. Proposition 64 continuously appropriates Cannabis Tax Fund proceeds to fund three types of activities:

- Allocation 1—Regulatory and Administrative Costs. First, revenues pay back certain state agencies for any cannabis regulatory and administrative costs not covered by license fees.

- Allocation 2—Specified Allocations. Second, after regulatory and administrative costs are covered, revenues go to certain research and other programs, such as researching the effects of cannabis and the effects of the measure.

- Allocation 3—Percentage Allocations. Third, these revenues go to three broad types of activities: 60 percent for youth programs related to substance use education, prevention, and treatment; 20 percent for environmental programs; and 20 percent for law enforcement. (Unlike the other allocations, funding for Allocation 3 comes from tax receipts from the prior year.)

Administration Has Discretion Within Each Percentage Allocation. Proposition 64 does not allow the administration to change the share of revenue allocated to each of the three Allocation 3 categories. (The measure loosens these restrictions starting in 2028.) However, it generally authorizes the administration to choose how to allocate funding among various eligible activities within each of the three Allocation 3 categories (youth substance use programs, environmental programs, and law enforcement). For example, as shown in Figure 5, in 2019‑20, the administration’s largest allocation within the substance use‑related youth program category was for childcare for children 13 and under ($81 million out of $119 million for this category).

Figure 5

Administration’s Anticipated Allocations of

Cannabis Tax Fund Revenues for 2019‑20

(In Millions)

|

Allocation 1: Regulatory and Administrative |

|

|

Bureau of Cannabis Control—Equity Programa |

$15.6 |

|

Fish and Wildlife |

9.2 |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

7.4 |

|

Tax and Fee Administration |

7.3 |

|

Employment Development Department |

2.5 |

|

Pesticide Regulation |

2.3 |

|

Statewide General Administration |

0.2 |

|

Total Allocation 1 |

$44.5 |

|

Allocation 2: Research and Other Programs |

|

|

Go‑Biz—community reinvestment |

$20.0 |

|

Public universities—evaluation of effects of measure |

10.0 |

|

Highway Patrol—impaired driving methodology |

3.0 |

|

University of San Diego—cannabis research |

2.0 |

|

Total Allocation 2 |

$35.0 |

|

Allocation 3: Percentage Allocations |

|

|

Youth Education Prevention, Early Intervention and Treatment Account |

|

|

Education—childcare slots |

$80.5 |

|

Health Care Services—local prevention programs |

21.5 |

|

Public Health—cannabis surveillance and education |

12.0 |

|

Resources Agency—youth community access grants |

5.3 |

|

Subtotal, Youth Account |

($119.3) |

|

Environmental Restoration and Protection Account |

|

|

Fish and Wildlife—environmental cleanup and enforcement |

$23.9 |

|

Parks—program development, ingress and egress, and restoration |

15.9 |

|

Subtotal, Environmental Restoration and Protection Account |

($39.8) |

|

State and Local Government Law Enforcement Account |

|

|

State and Community Corrections—local grants for public health and safety |

$26.0 |

|

Highway Patrol—impaired driving and traffic safety |

13.8 |

|

Subtotal, State and Local Government Law Enforcement Account |

($39.8) |

|

Total Allocation 3 |

$198.8 |

|

Total Expenditures |

$278.3 |

|

aAdministered by the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (Go‑Biz). |

|

Tax Treatment Differs Between Medical and Adult‑Use Cannabis. State law exempts medical cannabis from certain taxes under two scenarios. First, under a new law that takes effect January 1, 2020 (Chapter 837, Statutes of 2019 [SB 34, Wiener]), medical cannabis products that businesses donate to consumers free of charge (and that meet other conditions) are exempt from the state’s cannabis taxes. Second, cannabis is exempt from state and local sales taxes if purchased for medical use with a valid state medical identification card.

Implementation of Proposition 64

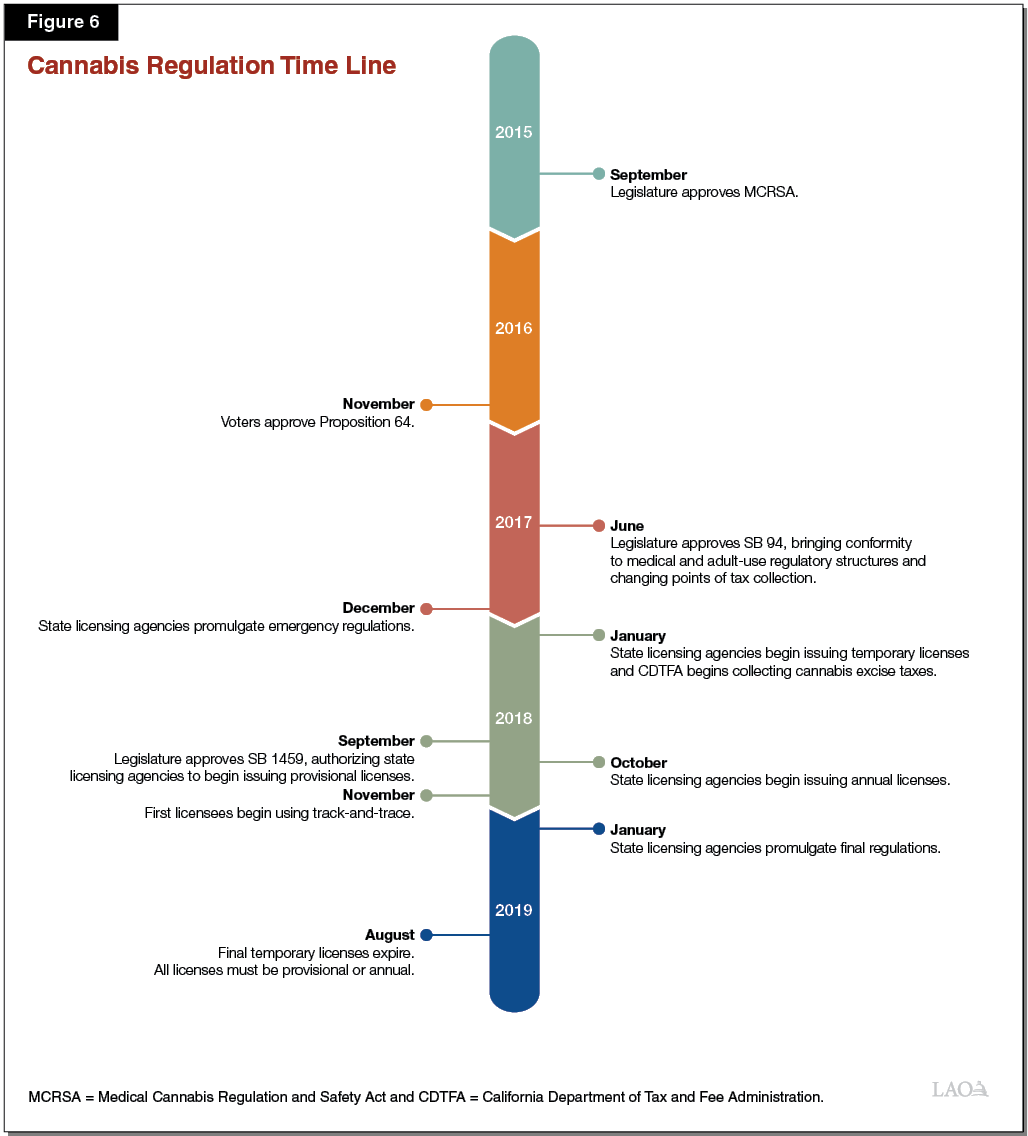

California Still in Early Stages of Implementing Regulatory Structure. Proposition 64 required state licensing agencies—such as the Bureau of Cannabis Control—to begin licensing cannabis businesses and administering cannabis excise taxes starting January 1, 2018. Given this time frame, implementing departments have taken a multistep approach, starting with temporary actions and then following up with more permanent ones. As shown in Figure 6, these actions include:

- Promulgating Regulations. The licensing departments promulgated regulations on an emergency basis in December 2017 and issued final regulations in January 2019. The final regulations specified detailed rules for how licensees must operate, such as the security protocols they must follow and how they must conduct laboratory tests on cannabis products. These regulations included some key decisions affecting the cannabis industry. For example, the regulations prohibit cities and counties from banning retail delivery of cannabis into their jurisdictions. (Some local governments currently are challenging this regulation in the courts.)

- Issuing Temporary Licenses. In January 2018, the licensing departments began issuing temporary licenses to businesses. These temporary licenses allowed businesses to operate on a conditional, limited‑term basis without paying license fees or participating in the track‑and‑trace program. The last temporary licenses expired in August 2019.

- Issuing Provisional and Annual Licenses. In September 2018, the Legislature passed Chapter 857 of 2018 (SB 1459, Cannella), which allowed the licensing departments to issue provisional cannabis licenses under certain conditions. Provisional licensees must pay license fees and participate in the track‑and‑trace program, but they do not need to show proof of full compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). (Complying with CEQA can involve a lengthy process.) Chapter 40 of 2019 (AB 97, Committee on Budget) extended the period in which businesses could hold provisional licenses to no later than January 2023, after which licensees will need to secure annual licenses, which require full compliance with CEQA. Licensing agencies began issuing annual licenses in October 2018.

- Requiring Participation in Track‑and‑Trace. As the temporary licenses have expired, more businesses have obtained provisional or annual licenses, a condition of which is that they enter certain product information into the track‑and‑trace system. When we prepared this report, the system still contained limited information.

Local Regulatory Policies Vary by Jurisdiction. Since the passage of Proposition 64, cities and counties have taken a wide variety of approaches to cannabis. Some local governments have licensed many cannabis businesses. Others have taken the opposite approach, prohibiting all cannabis businesses from locating within their boundaries. Finally, some have taken an in‑between approach—for example, licensing only medical cannabis businesses, licensing only certain types of adult‑use cannabis businesses, or capping the number of certain types of businesses (such as allowing only a limited number of retailers). Over time, there appears to be a general trend towards more local governments licensing cannabis businesses.

Local Tax Policies Vary by Jurisdiction. Local governments also have taken a wide variety of approaches to taxing cannabis. These approaches fall into three broad categories. First, many local governments impose the same tax rate on all cannabis businesses regardless of type. Second, many local governments impose higher tax rates on retailers than other types of cannabis businesses. Third, a few local governments license cannabis businesses but do not levy taxes specifically on cannabis. Although these three approaches lead to a wide range of local tax rates, we estimate that the average cumulative local tax rate over the whole supply chain is roughly equivalent to a 14 percent tax on retail sales. In addition to taxes, many local governments also require cannabis businesses to make other payments—such as fees—as a condition of operating.

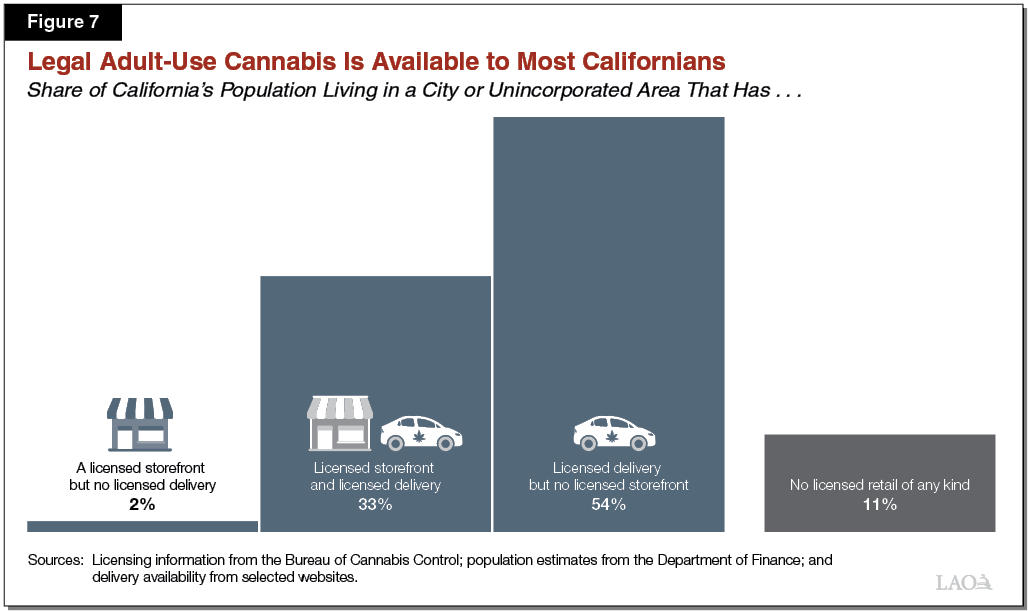

Consumer Access Depends on Delivery and Local Licensing. We estimate that one‑third of Californians live in cities or unincorporated areas with at least one licensed adult‑use retail storefront. As mentioned above, however, state regulations allow retail delivery even into cities and counties that do not authorize cannabis businesses. As a result, as shown in Figure 7, we estimate that about 90 percent of Californians live in jurisdictions with access to at least one state‑licensed adult‑use retailer—either storefront or delivery.

Cannabis Taxes in Other States and Canada

Nine other states and Canada have passed laws taxing adult‑use cannabis. We summarize these taxes in Figure 8. The most common type of cannabis tax is an ad valorem (price‑based) tax on retail sales, and the second‑most common is a weight‑based tax on cultivation. Canada and Illinois have tax rates that incorporate information about potency—the amount of THC in a product. (We further describe the different types of cannabis taxes in the nearby text box)

Figure 8

Adult‑Use Cannabis Taxes in Other States and Canada

|

Jurisdiction |

Year Implemented |

Type(s) of Tax |

Key Rate(s) on January 1, 2020 |

Additional Local Taxes |

|

Alaska |

2016 |

Weight‑based excise tax |

$50 per ounce of mature flower, $15 per ounce of leaves |

Taxes on retail sales (no cap on rates) |

|

Canada |

2019 |

|

|

Varies |

|

Coloradoa |

2014 |

|

|

Taxes on retail sales (no cap on rates) |

|

Illinois |

2020 (scheduled) |

|

|

Combined local taxes of up to 6 percent on any adult‑use business (cities up to 3 percent and counties up to 3 percent within city limits) |

|

Maine |

2020 (scheduled) |

|

|

None |

|

Massachusetts |

2018 |

Ad valorem tax on retail sales |

10.75 percent |

Taxes of up to 3 percent on retail sales |

|

Michigan |

2020 (scheduled) |

Ad valorem tax on retail sales |

10 percent |

None |

|

Nevada |

2017 |

|

|

None |

|

Oregon |

2016 |

Ad valorem tax on retail sales |

17 percent |

Taxes of up to 3 percent on retail sales |

|

Washington |

2014 |

Ad valorem tax on retail sales |

37 percent |

None |

|

aAlthough Colorado’s retail tax rate is nominally 15 percent, cannabis is exempt from the general sales tax rate of 2.9 percent, yielding a net tax rate of 12.1 percent. bEstimated tax rates in U.S. dollars based on current exchange rates. THC = tetrahydrocannabinol. |

||||

Types of Cannabis Taxes to Consider

- Basic Ad Valorem Tax. Under a basic ad valorem tax, the amount of tax due is a percentage of the price. The sales tax and California’s current retail excise tax on cannabis are examples of ad valorem taxes.

- Weight‑Based Tax. Under a weight‑based tax, the amount of tax due is based directly on the weight of the product. The rates can vary depending on the part of the plant (for example, flower or leaves) or its condition (for example, dried or fresh). California’s current cultivation tax is an example of a weight‑based tax.

- Potency‑Based Tax. Under a potency‑based tax, the amount of tax due depends only on the potency of the cannabis product. For example, Canada’s cannabis tax system includes a rate of $0.01 Canadian (roughly three‑quarters of a cent U.S.) per milligram of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in certain types of cannabis products. Hereafter, we use “potency‑based” primarily to refer to this simple THC‑based structure. However, potency‑based taxes could take a variety of forms—for example, incorporating other cannabinoids in addition to THC.

- Tiered Ad Valorem Tax. A tiered ad valorem tax is similar to the basic ad valorem tax, but with multiple rates. These rates could depend on potency and/or the type of product. For example, Illinois has set three different ad valorem tax rates on cannabis based on potency and product type: 10 percent on cannabis flower and other products with THC concentrations below 35 percent; 20 percent on cannabis infusions, such as edibles; and 25 percent on products with THC potency above 35 percent, such as concentrates.

Effects of Tax Rate Changes on Legal and Illicit Markets, Tax Revenue, and Youth Use

As noted above, Proposition 64 requires us to recommend adjustments to the state’s cannabis tax rate to achieve three goals: (1) undercutting illicit market prices, (2) ensuring sufficient revenues are generated for the programs identified in the measure, and (3) discouraging use by persons younger than 21 years of age. In this section, we discuss the effects of tax rate changes on these outcomes.

Effects of Tax Rate Changes Illustrated With Four Examples. By “effects,” we refer to the difference between two outcomes: (1) the outcome that would occur under a given policy choice, and (2) the outcome that would occur under the current policy, all else equal. (Effects does not refer, for example, to year‑over‑year changes in outcomes. We elaborate on this point in the Appendix.) To make our discussion of short‑term effects concrete, we provide estimates for four examples of potential rate changes. These examples reflect recent proposals considered by the Legislature and other options to provide a better sense of potential effects of changes.

- Example 1: Eliminating Cultivation Tax and Reducing Retail Excise Rate to 11 Percent. Bills introduced in 2018 (AB 3157, Lackey) and 2019 (AB 286, Bonta) proposed these rate changes.

- Example 2: Eliminating Cultivation Tax and Keeping Retail Excise Rate at 15 Percent. In 2019, the Legislature discussed amendments to AB 286 that would have enacted this change.

- Example 3: Eliminating Cultivation Tax and Raising Retail Excise Rate to 20 Percent. As discussed below, we estimate that this change likely would be roughly revenue neutral in the short term.

- Example 4: Keeping Current Cultivation Rates and Raising Retail Excise Rate to 25 Percent. To illustrate a range of options, we round out the list of examples with a net tax increase.

Effects Uncertain, Particularly in the Long Run. Adult‑use cannabis legalization is a relatively new phenomenon, so useful evidence on the effects of changing cannabis tax rates is limited. As a result, these effects are uncertain to varying degrees. As described below, we have estimated the likely short‑term effects of rate changes on two outcomes related to the statutory goals described above—the size of the legal cannabis market and cannabis tax revenues. (“Short‑term” refers to the first year or two after the rate change. We discuss our estimation methods briefly in the Appendix.) However, available evidence does not enable us to quantify the long‑term effects of rate changes on those outcomes, nor the short‑term or long‑term effects of rate changes on other outcomes related to the statutory goals, such as the size of the illicit market and youth use. Instead, we discuss these effects qualitatively.

Effects on Size of Legal and Illicit Markets

Basic Relationship Between Taxes and Relative Prices. Cannabis tax rates directly affect the costs that legal cannabis businesses incur for selling cannabis. For example, if the state cut the tax rate, it would become less costly for those businesses to sell cannabis. As a result, consumers would pay lower prices for legal cannabis. (The magnitude of this price change would depend on market conditions.) In contrast, the change in tax rates would have no direct effect on the cost of selling cannabis in the illicit market. (The illicit market consists of commercial cannabis activity that does not comply with the regulatory structure required in law.) Consequently, a change in tax rates would affect the difference between legal and illicit prices, with a tax cut making legal cannabis more competitive with illegal cannabis compared to what would be the case in the absence of a cut.

What Does it Mean to “Undercut” the Illicit Market? One of the goals listed in Proposition 64 is to undercut illicit market prices. However, under current market conditions, changes in the state tax rate likely would not make legal cannabis less expensive than illicit cannabis. Even if the state eliminated its cannabis taxes entirely, other costs—such as regulatory compliance costs and local taxes—likely would keep legal cannabis prices higher than illicit market prices. (This could change if legal prices decline, as they have in other states.) Accordingly, we instead consider competition between the legal and illicit cannabis markets more broadly. Even if legal cannabis remains more expensive than illicit cannabis, any price change will affect some consumers’ choices, which in turn affect the sizes of the legal and illicit markets.

In Short Term, Tax Cuts Expand Legal Market. Our analysis of competition between the legal and illicit markets starts with estimation of the likely short‑term effects of tax rate changes on the amount of cannabis purchased from the legal market. As illustrated by the examples in Figure 9, tax cuts would expand the legal cannabis market, while tax increases would shrink it.

Figure 9

Estimated Short‑Term Effects of Rate Changes on Legal Consumption and Revenue

|

Cultivation Tax |

Retail Excise Tax |

Likely Short‑Term Percentage Change in |

Likelihood Revenue Would Exceed Thresholdb |

|

|

Legal Cannabis Consumption |

State Cannabis Tax Revenuea |

|||

|

Keep at current ratesc |

Keep at current rate (15%) |

0% |

0% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

Eliminate |

Reduce to 11% |

+6% to +20% |

‑34% to ‑43% |

Likely to fall short |

|

Eliminate |

Keep at current rate (15%) |

+3% to +11% |

‑16% to ‑25% |

Roughly equal chances of exceeding and falling short |

|

Eliminate |

Increase to 20% |

‑2% to +1% |

‑5% to +3% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

Keep at current rates |

Increase to 25% |

‑7% to ‑22% |

+18% to +40% |

Very likely to exceed |

|

aUnder current law, we expect state cannabis tax revenue to be in the mid‑hundreds of millions in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. bSome provisions of Proposition 64 imply that revenue below $350 million in 2021‑22 would not be sufficient. cAs of January 1, 2020, the cultivation tax rates are $9.65 per ounce of dried cannabis flowers, $2.87 per ounce of dried cannabis leaves, and $1.35 per ounce of fresh cannabis plants. |

||||

Tax Cuts Reduce Illicit Market, but Size of Effect Is Uncertain. Ideally, we would be able to identify what proportion of the increase in legal consumption of cannabis would be due to reductions in illicit consumption (substitution) as opposed to increased cannabis use overall. Unfortunately, while we suspect that tax cuts would increase substitution from the illicit market more than they would increase actual consumption, we have found no evidence that would enable us to quantify these effects. Thus, while a tax cut clearly would reduce the size of the illicit market to some extent (and a tax increase would expand it), we cannot quantify the extent of this effect.

Taxes Likely Have Little Effect on Exports. The illicit market for California‑grown cannabis consists of two parts: (1) cannabis sold in California and (2) cannabis exported out of the state. In‑state sales likely account for a small share of California‑grown cannabis. Crucially, exported cannabis does not compete directly with California’s legal market, so changing the state’s cannabis tax rate likely would have little effect on it. Additionally, as mentioned previously, a key federal enforcement priority is preventing the export of cannabis to other states. Accordingly, California and others states that have legalized cannabis do not allow licensed cannabis businesses to export cannabis out of state. Thus, regardless of the state’s tax system, under current federal policies, California cannot bring exported cannabis into the state’s legal market.

Long‑Term Effects Highly Uncertain. The long‑term effects of rate changes on the size of the legal and illicit markets, while important, are highly uncertain. In theory, these long‑term effects could be substantially different from the short‑term effects. One reason is that changes in state tax rates could affect cities’ and counties’ licensing and taxation choices, which in turn would affect the size of the legal and illicit markets. Suppose, for example, that the state reduces its tax rate. On the one hand, local governments could respond by raising their tax rates, partly offsetting the effects of the state tax cut. On the other hand, local governments could respond to the potential for generating greater tax revenue by licensing more cannabis businesses, amplifying the market‑expanding effects of the state tax cut on legal consumption.

Effects on Tax Revenue

Tax Cuts Reduce Revenue in the Short Term. Figure 9 displays our estimates of the short‑term revenue effects of the four rate changes described above. As directed by Proposition 64, our revenue estimates focus exclusively on state cannabis tax revenues. Overall, reducing cannabis tax rates would reduce revenues in the short term, while raising rates would lead to higher revenues. (Under current law, we expect state cannabis tax revenue to be in the mid‑hundreds of millions of dollars in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22.) Although tax cuts would expand the legal market, this effect would not be anywhere near large enough to fully offset the revenue loss. Modest rate increases, on the other hand, would raise revenue in the short term. (We estimate that extremely large rate increases—such as an increase in the retail excise tax rate from 15 percent to 80 percent—likely would reduce revenue.) The long‑term revenue effects of rate changes are highly uncertain, for the same reasons that the long‑term effects on legal and illicit markets are uncertain.

What Are “Sufficient Revenues”? Proposition 64 does not define what constitutes sufficient revenues. However, the measure requires the California Highway Patrol (CHP) to receive at least $50 million from Allocation 3 (starting in 2022‑23). Because many other programs must receive funding prior to this allocation, we estimate the state would have to collect at least $350 million in revenue in 2021‑22 to meet the CHP funding requirement. Accordingly, it is reasonable to assume that 2021‑22 revenue below $350 million would not be sufficient. Beyond this requirement, it is difficult to determine what level of revenue would be sufficient. (We discuss these difficulties further in the nearby box.)

Sufficient Revenues Under Proposition 64

Proposition 64 (2016) requires our office to make recommendations on adjustments to the tax rate in order to ensure sufficient revenues are generated for the programs identified in the measure, among other goals. As we discuss below, there are a few key reasons why it is difficult to determine what constitutes sufficient revenues. Some of these challenges include the administration’s flexibility in choosing which programs to fund, the lack of a clear definition of “sufficiency,” and revenue uncertainty. Additionally, the way the measure restricts the allocation of revenues—with fixed percentage allocations and no discretionary reserve—makes it more difficult for the state to fund programs sufficiently with a given amount of revenue.

Challenges in Determining Sufficient Revenues

Measure Provides Administration Discretion to Allocate Funds to Programs. The first step in determining sufficient revenue would be to identify the list of specific programs that would need to be funded. The measure, however, does not enable us to define such a list. Instead, it describes some broad program categories, and it generally authorizes the administration to allocate funding to a variety of possible programs within those categories. Accordingly, in practice, the administration may spend these funds on a wide range of activities. Additionally, the administration may adjust the amount of funding provided to each activity at any time. As a result, the amount of funding required could vary dramatically depending on the specific programs the administration chooses to fund.

Measure Lacks Direct Guidance on Sufficiency. The measure provides no direct guidance on what constitutes sufficient revenues. For example, the measure does not identify specific goals for the youth substance use programs, such as the number of programs funded, the number of individuals treated, or the reduction in youth substance use disorders achieved. Accordingly, even if the administration’s future funding allocations could be predicted with certainty, there still could be a variety of reasonable perspectives on what constitutes sufficient revenues for those programs.

Future Revenues Uncertain. Another complicating factor is that, even absent changes in tax rates, future cannabis tax revenues are uncertain. Accordingly, even if the Legislature could direct funds to programs that target the goals specified by the measure—youth substance use programs, environmental programs, and law enforcement—and even if those goals were clear, there would be significant uncertainty regarding the tax rate that would be needed to meet these goals.

Challenges in Achieving Sufficient Revenues

Restrictions in Measure Make it More Difficult to Achieve Revenue Sufficiency. Proposition 64 restricts the use of state cannabis tax revenues. These restrictions make it more difficult for the state to fund programs sufficiently with a given amount of revenue, primarily for two reasons:

- Percentage Allocations Remain Fixed. Although Proposition 64 gives the administration discretion to allocate funds within each of the three percentage allocations (youth substance use, environmental, and law enforcement), it does not authorize changes to the 60‑20‑20 split itself. If, for example, overall cannabis revenue provided sufficient funding for two of those three categories but not the third, neither the Legislature nor the administration could reallocate cannabis revenue to the area of greatest need.

- No Discretionary Reserve. Proposition 64 does not authorize the Legislature or the administration to maintain a discretionary reserve for the Cannabis Tax Fund. Such a reserve could help the state maintain sufficient programmatic funding if revenue were to decline in some years.

Other Funds Could Help Address These Challenges. Proposition 64 asks us to assess revenue sufficiency based only on the revenue raised by the state’s cannabis taxes. From a broader perspective, the state could address the challenges described above by supplementing the funding for these programs with other revenues, such as General Fund revenues.

Much Lower Rates Might Not Yield Sufficient Revenue. Under the current tax rates, we estimate that revenues are very likely to exceed the $350 million revenue threshold in 2021‑22. Figure 9 lists brief descriptions of the likelihood that revenues would exceed this revenue threshold under the four examples of potential rate changes.

Youth Use

Higher Taxes Could Reduce Youth Use, Depending on Availability of Illicit Cannabis. As discussed above, higher taxes would reduce legal cannabis consumption, but we do not know how much of this reduction would consist of substitution to the illicit market and how much would consist of reductions in actual consumption. This uncertainty extends to the effects of changes to cannabis taxes on youth use. If youth easily can acquire cannabis from the illicit market, tax increases on legal cannabis might not substantially raise the actual prices that youth pay. If taxes do not substantially raise actual prices paid by youth, they very likely would have little effect on youth use. That said, if the illicit market becomes less active over time—for example, as a result of more active enforcement—taxes could become a reliable tool for reducing youth use.

Tobacco taxes provide a reference point for the relationships among tax rates, illicit trade, and youth substance use. Research shows that tobacco taxes raise tobacco prices despite significant illicit tobacco trafficking, thus reducing youth tobacco use. Illicit sales currently play a much bigger role in California’s cannabis market than in typical tobacco markets, likely making illegal cannabis accessible to youth even in a scenario with relatively high tax rates. That said, total elimination of illicit cannabis markets likely is not a prerequisite for higher cannabis taxes to reduce youth cannabis use.

Other Key Effects of Rate Changes

Analysis of Harmful Use and Medical Use Similar to Youth Use. In addition to the three criteria laid out in statute, we encourage the Legislature to consider two additional major criteria as it weighs potential adjustments to cannabis taxes:

- Harmful Use. Excise taxes can reduce not just youth use of cannabis, but harmful use more generally. As noted in the Background section, evidence suggests that cannabis use can have some negative effects, such as increased risk of motor vehicle crashes. As with youth use, however, the effects of cannabis taxes on harmful use likely depend on the extent to which illicit cannabis remains a readily available substitute for legal cannabis. As long as illicit consumption remains common, consumers of all ages face a variety of health risks due to the unregulated nature of those products. Also, as we discuss in the next section, the effects of cannabis taxes on harmful use depend not only on the tax rate, but also on the type of tax.

- Medical Use. As described in the Background section, cannabis can be useful for addressing certain ailments. Consequently, an ideal system of cannabis regulation and taxation would enable the state to tax cannabis used for medical purposes at a substantially lower rate than cannabis for adult use. (We further compare taxes on cannabis and on medicine in a recent online post, Comparing Taxes on Cannabis to Taxes on Other Products in California.) However, distinguishing medical cannabis products and customers from adult use is difficult in practice. This is because (1) similar products can be used by medical and adult‑use users, and (2) cannabis can be used to treat a variety of conditions, some of which can be difficult to verify (such as chronic pain). Due in large part to the challenge of distinguishing medical cannabis from adult‑use cannabis, the state generally taxes both types similarly. As a result, higher cannabis taxes have the potential to reduce not just youth and other harmful use, but also medical use.

Changing Tax Rates Would Involve Trade‑Offs Between Statutory Goals

In Short Term, Rate Cuts Help Address Illicit Market but Reduce Revenue. In light of the above analysis, the Legislature faces trade‑offs when considering adjustments to the state’s cannabis tax rate. Any tax rate change would help the state meet certain goals while likely making it harder to achieve others. On one hand, for example, reducing the tax rate would expand the legal market and reduce the size of the illicit market. On the other hand, such a tax cut would reduce revenue in the short term, potentially to the extent that revenue could be considered insufficient. Furthermore, lower tax rates could lead to higher rates of youth cannabis use—particularly if the state makes progress towards reining in the illicit market.

Importance of Nontax Policies

Nontax Policies Also Affect Legal and Illicit Markets, Revenues, and Youth Use. The scope of this report is limited to state cannabis taxes. These taxes, however, are only one of many state policies that could affect revenue, the illicit market, and youth use. Examples of other such policies include increased criminal or civil penalties for participating in the illicit cannabis market, additional state or local resources devoted to enforcing state laws, changes in state licensing requirements, changes to local governments’ authority to ban cannabis businesses, and resources devoted to youth education on the effects of cannabis use. For instance, enhanced enforcement would make it more difficult and costly for businesses to operate in the illicit market. This likely would shift activity from the illicit market to the legal market, thereby increasing tax revenues. Additionally, it likely would affect youth use by making it more difficult and expensive for them to access cannabis through the illicit market.

Considering Other Potential Changes to Cannabis Taxes

Basic Tax Policy Choices Should Precede Changes to Tax Rates. The prior section focuses narrowly on our statutory charge of assessing the effects of adjusting tax rates, taking the existing tax structure as given. As discussed in that section, changing cannabis tax rates could help the Legislature make progress towards some of the measure’s goals, though there are trade‑offs involved. The Legislature could make further progress towards those goals and others by making changes not only to the tax rates, but also to the basic structure of the taxes. As summarized in Figure 10, we encourage the Legislature to approach cannabis tax policy in three steps: first, choosing what type of tax to impose on cannabis; second, choosing the taxed event and point of collection for the tax; and third, choosing the tax rate.

Figure 10

Setting the Cannabis Tax Rate

|

|

|

|

|

|

Considering the Type of Tax

Types of Taxes to Consider. We have identified four types of cannabis taxes that the Legislature may wish to consider: basic ad valorem, weight‑based, potency‑based, and tiered ad valorem. We describe these taxes further in the "Types of Cannabis Taxes to Consider" box above.

Criteria to Consider When Choosing Type of Tax. Key criteria to consider when selecting the type of tax include:

- Harmful Use. As noted in the “Background” section, the negative effects of cannabis use seem to be particularly high for high‑potency products, high‑frequency use, and youth use. To score well on this criterion, a tax should impose higher costs on more harmful purchases and lower costs on less harmful purchases. (As noted above, diminished illicit market activity would help make the tax more useful for this purpose.)

- Raising Stable Revenues. For any type of tax, the Legislature can set the rate to raise a particular amount of revenue (up to a point) in an average year. However, the revenue raised by some types of taxes could grow at rates that vary unpredictably from year to year, while other taxes could raise more stable revenues. The latter types score better on this criterion than the former.

- Administration and Compliance. To score well on this criterion, a tax should be relatively straightforward for tax administrators and taxpayers to implement and enforce.

- Other Criteria. In addition to the three main criteria identified above, the Legislature also may wish to consider other criteria, such as: (1) the extent to which a tax could help the legal market compete effectively with the illicit market; (2) the extent to which a tax would create arbitrary cost differences between very low‑THC cannabis products and similar hemp products; (3) the difficulty of implementing the change.

Assessment of Tax Types

Figure 11 summarizes our assessment of the four types of cannabis taxes based on the three main criteria identified above. As we discuss below, each type of cannabis tax has strengths and weaknesses, and no individual type of tax performs best on all criteria. Accordingly, the Legislature’s choice depends heavily on the relative importance it places on each of these criteria. That said, the weight‑based tax is generally weakest, performing similarly to or worse than the potency‑based tax on the three main criteria.

Reducing Harmful Use. We rate the potency‑based and tiered ad valorem taxes as having the greatest potential to reduce harmful use.

- Potency‑Based Could Reduce Harmful Use Very Effectively. The negative effects of cannabis appear to be linked in large part to the potency of the products used. Accordingly, a potency‑based tax is a direct, consistent way to use taxes to discourage harmful use, so it scores well on this criterion.

- Tiered Ad Valorem Also Could Reduce Harmful Use Very Effectively. While measured THC potency is a very important determinant of harmful use, it is far from the only one. Other key factors include the share of THC absorbed by the body, as well as other health risks (such as pulmonary risks from smoking). The Legislature could use a tiered ad valorem tax to set higher rates not only on more potent products, but also on specific product categories—such as certain types of concentrates—regarded as particularly harmful. In this way, a tiered structure could account for some of these other harmful attributes, and thus also have the potential to be very effective at reducing harmful use. That said, the relative effectiveness of this tax depends heavily on the rate differences between tiers. Suppose, for example, that a consumer is choosing between a more harmful product and a less harmful product that fall within the same rate tier. For this consumer, the tiered ad valorem tax does not reduce harmful use any more effectively than a basic ad valorem tax.

- Weight‑Based and Ad Valorem Likely Worse for Reducing Harmful Use. Weight‑based and ad valorem taxes do not directly target high‑potency products and other products associated with harmful use. Accordingly, they score less well on this criterion. Weight and price are related to harmful use, but these relationships are complex. For example, the production of high‑potency products, such as concentrates, tends to require greater quantities (and thus weight) of cannabis. However, since weight‑based taxes apply the same tax rate to cannabis flowers regardless of their potency, they tend to encourage the cultivation of higher‑potency cannabis. Additionally, some evidence suggests that more potent products (and products with high THC absorption rates) tend to be somewhat more expensive than less potent products. However, for a given type of product, heavy users might pay lower prices—and proportionally lower ad valorem taxes—than infrequent users. This could happen, for example, if heavy users tend to obtain bulk discounts or if they tend to be more price‑sensitive than infrequent users. Furthermore, price declines—discussed in more detail below—could reduce the effectiveness of an ad valorem tax at reducing harmful use over time if the state does not adjust the rate accordingly.

Stable Revenues. We rate the weight‑based and potency‑based taxes as most effective at providing stable revenues. We discuss each of the options from least effective to most.

- Ad Valorem Likely Least Stable, Though Adjustments Could Help. We think that cannabis prices in California likely will decline in the coming years as the cannabis market matures, consistent with other states’ experience. These potential near‑term price declines would tend to slow the growth of revenues generated from an ad valorem tax. We expect that price declines would coincide with increases in the quantity of cannabis purchased, which would somewhat offset their effects on ad valorem revenues. Furthermore, the state could address this weakness of the ad valorem tax by adjusting the tax rate frequently to reflect price changes. For example, the Legislature could direct CDTFA to adjust tax rates automatically based on changes in average cannabis prices. While this type of adjustment could help improve the stability of ad valorem taxes, it would be imperfect because it would take some time to adjust the rate, and Proposition 64 does not allow for reserves to help smooth out spending in the interim.

- Tiered Ad Valorem Also Relatively Volatile. Like a basic ad valorem tax, a tiered tax could raise volatile revenues. However, if the trend towards higher‑potency products continues, then revenue from the tiered tax could grow accordingly, perhaps somewhat offsetting revenue slowdowns resulting from declining prices. Like the ad valorem tax, the state could address this weakness of the tiered ad valorem tax by adjusting the tax rate frequently to reflect price changes.

- Weight‑Based and Potency‑Based Best for Generating Stable Revenues. Based largely on other states’ experiences, we generally expect total plant weight and THC produced in the legal cannabis market to be less volatile than prices. Accordingly, weight‑based and potency‑based taxes likely would raise more stable revenues than an ad valorem tax (basic or tiered).

Administration and Compliance. We rate the basic and tiered ad valorem taxes as best for administration and compliance.

- Basic Ad Valorem Best for Administration and Compliance. The basic ad valorem tax is easier for CDTFA to administer than weight‑based taxes and potency‑based taxes. CDTFA has considerable financial expertise as well as direct experience implementing ad valorem taxes, such as the sales tax. Similarly, CDTFA already has an administrative structure for auditing and enforcing payment of ad valorem taxes, which makes it easier for the department to ensure compliance. Furthermore, basic ad valorem taxes can make taxpayer compliance relatively straightforward, as they often do not require businesses to collect much information beyond what they track during their normal course of business.

- Tiered Ad Valorem Also Good for Administration and Compliance. A tiered ad valorem tax would be somewhat more complicated to administer than a basic ad valorem tax. However, as long as the number of rates were relatively small, a tiered ad valorem tax should not be overly difficult to administer. Notably, CDTFA has some experience implementing tiered ad valorem rates for the alcoholic beverage tax. (We discuss comparisons between cannabis taxes and other excise taxes—including alcoholic beverage taxes—in greater detail in an accompanying online post, Comparing Taxes on Cannabis to Taxes on Other Products in California.)

- Administration and Compliance More Difficult for Weight‑Based and Potency‑Based. CDTFA does not have much expertise regarding the weight or chemical composition of products. While data entered into the track‑and‑trace system could help taxpayers and the department implement a weight‑based or potency‑based tax, these taxes likely still would be more difficult for the agency to administer than an ad valorem tax. Potency might seem like a more exotic tax base than weight, but it is not clear that it would be more difficult to administer. This is in part because a potency‑based tax has two key advantages with regard to administration and compliance. First, testing labs verify the potency of cannabis products. (As we understand it, these tests rarely find substantial differences between labeled and actual cannabinoid content. More commonly, products fail lab tests for other reasons, such as high levels of pesticides.) In contrast, the state has not established any mechanism for consistent, direct third‑party verification of the weight of harvested plants. Second, THC content appears on the labels of all cannabis products, allowing for further verification opportunities upon retail purchase. In contrast, once a cannabis product has entered the manufacturing process, there is no way to verify the weight of the raw plant material used to make it.

Other Criteria. Below, we discuss how the various types of taxes perform on some additional criteria.

- No Clear, Major Differences in Competition With Illicit Market. As discussed above, higher tax rates reduce the size of the legal cannabis market and expand the illicit market. However, we do not anticipate any similarly clear, major effects of the type of tax on the relative strength of the legal and illicit markets. As discussed above, compliance could be more difficult for some types of taxes than others, but the resulting effects on the size of the legal and illicit markets likely would be small.

- Potency‑Based Would Reduce Cost Differences Between Cannabis and Hemp Products. The state’s cannabis taxes apply to cannabis and all of the products derived from it, regardless of their THC content. However, these taxes do not apply to hemp or to the products derived from it. As a result, these taxes could create large, essentially arbitrary cost differences between low‑THC cannabis‑derived products and similar hemp‑derived products. A potency‑based cannabis tax could make these cost differences much smaller than a weight‑based tax or an ad valorem tax.

- Bigger Changes Would Be Harder to Implement. Implementing major changes could involve a variety of challenges during the transition to the new tax structure. For example, the transition to a potency‑based tax would be more difficult for tax administrators and taxpayers than a minor adjustment to one of the existing taxes.

Number of Taxes to Levy

The Legislature faces trade‑offs in deciding how many cannabis taxes to levy. If multiple taxes have highly complementary strengths and weaknesses, then a carefully chosen combination of taxes could have the potential to achieve better outcomes than one of them alone. However, our assessment suggests that such a combination might not exist in practice, limiting the gains from levying more than one type of tax. Additionally, levying more than one type of tax makes tax administration and compliance more burdensome and complex. Accordingly, on balance, we do not think there is a strong rationale for levying multiple types of cannabis taxes.

Choosing the Taxed Event and Point of Collection

After the Legislature decides what type of tax it wants to levy on cannabis, the next step is to choose both the taxed event and the type of business that will remit the tax (also known as the “point of collection”).

Taxed Event Options. The Legislature may wish to considering levying a cannabis tax at any of three points in the supply chain:

- The sale or transfer of harvested cannabis from the cultivator to the first distributor.

- The sale or transfer of cannabis products from the last distributor to the retailer.

- The sale of cannabis products from the retailer to the consumer.

Point of Collection Options. The Legislature may wish to consider assigning tax remittance responsibilities to the cultivator, the first distributor, the last distributor, or the retailer.

Criteria to Consider When Choosing Taxed Event and Point of Collection. Below, we identify some key criteria to consider when choosing the taxed event and the point of collection, roughly in descending order of importance. These criteria reflect conditions conducive to effective tax administration and compliance.

- Nexus Between Taxed Event and Point of Collection. For most taxes, a single entity—a taxpayer—participates in the taxed event, collects the original tax payment, and remits the tax to the state. In other words, there is a very close nexus between the taxed event and the point of collection. In contrast, California’s cannabis taxes split these responsibilities between multiple businesses. This separation of taxpaying responsibilities weakens each business’s incentive to ensure that the correct amount of tax is paid. An additional concern arises because many cannabis businesses have limited access to financial services due to federal criminalization. The current split of taxpaying responsibilities often involves cash changing hands multiple times, leading to problems with security, compliance, and enforcement. Furthermore, distributor remittance of the retail excise tax requires a markup calculation that makes the tax more difficult to administer.

- Taxpayer Characteristics. An ideal taxpayer plays a consistent role in the supply chain, is readily identifiable and visible to tax administrators and the public, has an established relationship with tax administrators, and is familiar with the record‑keeping practices needed to pay taxes accurately and comply with audits.

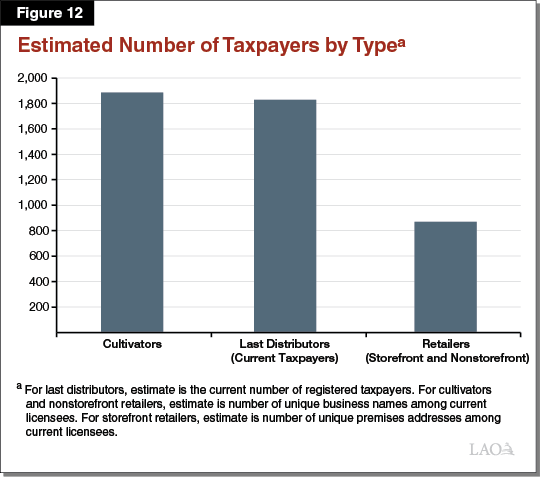

- Number of Taxpayers. All else equal, tax administration is more cost‑effective when there are fewer taxpayers. In Figure 12, we compare the current number of taxpayers to the estimated number of taxpayers under two alternative points of collection. As shown in the figure, we estimate that collecting taxes from retailers would result in a significantly smaller taxpayer population than collecting from cultivators or last distributors (the current point of collection).

- Credit Constraints. As noted above, many cannabis businesses have limited access to financial services—including credit. As a result, it could be difficult for some of these businesses to set aside money for tax payments before consumers purchase their products. To address this concern, the Legislature could levy cannabis taxes as late in the supply chain as possible.

Best Taxed Event and Point of Collection Vary by Type of Tax

For each type of tax, there are trade‑offs among different taxed events and points of collection. Below, we summarize the main trade‑offs and assess the best taxed event and point of collection for each type of tax.

Ad Valorem (Basic and Tiered): Tax Retail Sales and Collect Tax From Retailers. Compared to distributors, retailers play a more consistent and public‑facing role in the supply chain, and they already interact with CDTFA through the sales tax. Additionally, moving tax payments to the retail level could address concerns related to credit constraints. Accordingly, we view retail sales and retailers as the best taxed event and point of collection, respectively, for both types of ad valorem cannabis taxes. (As discussed in our related online post, A Key Interaction Between Sales Taxes and Other Taxes on Cannabis Retailers, moving the point of collection to the retail level could give the state an opportunity to create a uniform tax base across multiple retail taxes.)

Potency‑Based Tax: Two Reasonable Options. Many of the reasons for levying ad valorem taxes at the retail level also apply to potency‑based taxes. As shown in Figures 2 and 4, however, lab testing of cannabis products occurs shortly before distribution from the last distributor to the retailer. Accordingly, there is a close nexus between the last distributor and the initial measurement of the tax base for a potency‑based tax. Overall, a reasonable case could be made to (1) levy a potency‑based tax on the retail sale and collect it from the retailer, or to (2) levy a potency‑based tax on the last distribution and collect it from the distributor.

Weight‑Based: Tax Sale or Transfer to First Distributor and Collect Tax From First Distributor. The only practical opportunities to weigh cannabis plants occur early in the supply chain, around the time of sale or transfer from the cultivator to the first distributor. Accordingly, this sale or transfer is the best taxed event for a weight‑based tax, and the point of collection should be one of the two businesses involved in the transaction—the cultivator or the first distributor.

Choosing Timing of Changes

Historically, the Legislature has adjusted excise tax rates very infrequently. If this experience is a guide, the Legislature might want to think carefully about the timing of any changes to the state’s cannabis tax structure and rates. On one hand, the sooner the Legislature changes the state’s cannabis taxes, the sooner the state will realize any benefits associated with those changes. On the other hand, as discussed below, there are advantages to waiting until more information is available and the market is more stable.

- Full Implementation of Track‑and‑Trace Could Provide Valuable Data. Information that licensees enter into the track‑and‑trace system could be very helpful for estimating the effects of potential changes to the state’s cannabis taxes. We anticipate that track‑and‑trace system data collection will ramp up considerably in the coming months, since all licensees are now required to participate. Additionally, we expect that the data in the system will improve over time as licensees become accustomed to using it and administering agencies have time to validate the data.

- Current Law Limits Researchers’ Access to Track‑and‑Trace. Chapter 27 of 2017 imposes strict limits on access to track‑and‑trace data. Specifically, the statute allows access only for authorized state and local government employees pursuant to certain laws. While there are legitimate reasons—such as privacy concerns—for restricting access to track‑and‑trace data, these restrictions makes it difficult for our office or other researchers to use the data to help inform the Legislature’s policymaking.

- Scientific Understanding of Cannabis’ Effects Will Improve. Although there is some useful research on the effects of cannabis, federal criminalization of cannabis has impeded research progress. For example, researchers have had to purchase cannabis from one supplier and have not had access to the full range of cannabis strains and products that are available in the marketplace. Accordingly, there are still significant gaps in scientific understanding of the health effects of various cannabis products. Over time, we anticipate that research will fill some of these gaps and scientific understanding of the effects of cannabis will improve, particularly if the federal government loosens its restrictions. This improved understanding could help the Legislature create a tax structure that more effectively addresses the harmful aspects of the plant or more effectively differentiates between medical and adult use for tax purposes.

- Regulatory Environment and Industry Are Still in Flux. California’s legal cannabis industry is still in the early stages of its development, making it difficult to predict what the industry will look like in the future. The long‑term effects of tax policy changes would depend on industry growth, licensing requirements, market structure, prices, potency, product mix, and many other factors that could change considerably in the coming years.

Recommendations

As described further below and summarized in Figure 13, we recommend that the Legislature make various changes to cannabis taxes. These changes—which could be complemented by changes to nontax policies—include: (1) replacing the state’s existing cannabis taxes with a potency‑based or tiered ad valorem tax; (2) choosing the taxed event and point of collection to match the type of tax chosen; (3) setting the tax rate to match the Legislature’s policy goals; and (4) taking some related actions, such as clarifying access to track‑and‑trace data and crafting the definition of gross receipts carefully. We recommend that the Legislature enact these changes soon given the benefits they could yield. Additionally, we recommend that the Legislature revisit cannabis taxes periodically to see if further changes are warranted in light of new information from track‑and‑trace and from scientific research on the effects of cannabis.

Figure 13

Summary of Recommendations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Change Type of Tax to Account for Potency and/or Product Type