LAO Contacts

February 12, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget:

Department of General Services

- Department Overview

- CFS Workload

- Construction of Sacramento Office Buildings: Resources, Bateson, and Unruh Projects

- Deferred Maintenance

Summary

In this analysis, we assess the Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposals for the Department of General Services (DGS). Specifically, we review and make recommendations regarding the Governor’s proposals for (1) additional staff for Contracted Fiscal Services (CFS) workload, including the establishment of a new strike team to assist departments performing accounting activities with the Financial Information System for California (FI$Cal); (2) renovating the Resources, Bateson, and Unruh buildings, and (3) funding elevator and fire system‑related deferred maintenance projects. (We discuss DGS’ proposal to support statewide emergency management functions in our forthcoming report, The 2020‑21 Budget: Governor’s Wildfire‑Related Proposals.) In summary, we recommend the following:

- CFS Workload. Approve the six positions for the strike team on a two‑year limited‑term basis because the level of ongoing workload for the strike team is uncertain, particularly given that the other resources have been provided to assist departments transition to Fi$Cal.

- Renovation of the Bateson, Unruh, and Resources Buildings. Require DGS to report at budget hearings on options for reducing the costs of these projects in order to assess whether to move forward with the original scope and timeline of these projects or make adjustments given their significant cost increases.

- Deferred Maintenance. Reject $35.4 million (General Fund) proposed for elevator projects at two facilities because it is not clear that these projects must be done immediately and the General Fund should not be used on a long‑term basis to fund DGS building needs. Additionally, require DGS to report at budget hearings on its plan for maintaining facilities and for adjusting building rates to address building maintenance needs.

Department Overview

The DGS provides a variety of services to state departments, such as procurement, management of state‑owned and leased real estate, management of the state’s vehicle fleet, printing, administrative hearings, legal and fiscal services, development of building standards, and oversight over school construction. The department generally funds its operations through fees charged to client departments.

The Governor’s budget proposes $2 billion from various funds to support DGS in 2020‑21. This is a net decrease of $257 million, or about 11 percent, from current‑year estimated expenditures. This decrease primarily reflects the expiration of $1 billion in one‑time funding provided in 2019‑20 to construct a new building on Richards Boulevard in Sacramento, offset by $722 million in one‑time funding provided in 2020‑21 to renovate three state buildings. (We discuss the proposed funding for the three building renovations further below.)

CFS Workload

Background

CFS Provides Accounting and Budgeting Services to Various State Entities. The CFS program within DGS provides fiscal services—including accounting and budgeting services—to other state entities on a fee‑for‑service basis. CFS currently provides these services to 45 state entities, such as the Horse Raising Board, the Commission on State Mandates, and various state conservancies. Many of CFS’ client agencies are small, which makes it difficult for them to provide their own fiscal services in a cost‑effective manner. The 2019‑20 budget included $9.5 million for CFS.

Fi$Cal Project. For almost 15 years, the administration has been engaged in the design, development, and implementation of the FI$Cal project. This information technology (IT) project is being developed to replace the state’s aging and decentralized IT financial systems with a new system that integrates the state’s accounting, budgeting, cash management, and procurement processes. In 2016, the Legislature established the Department of FI$Cal to maintain and operate the IT system and support its users. These users currently include a total of 152 departments, with additional departments expected to be added in the coming years. The revised 2019‑20 budget includes $138 million for the Department of FI$Cal.

State Provided Significant Resources to Support Department Transitions to Fi$Cal. Many departments have experienced challenges transitioning to Fi$Cal. In response to these challenges, the state has provided significant resources to assist departments implement the system. For example, in 2019‑20, the Department of Fi$Cal received $64.1 million ($39.1 million General Fund) over three years to provide additional user training (including on accounting in FI$Cal, such as closing month‑ and year‑end financial statements) and department support (such as assisting with changing departmental business processes). In addition to the resources provided to the Department of Fi$Cal, at least 13 other departments also received FI$Cal‑related resources in 2019‑20. These resources included, for example, increased staffing to enable departments to address the additional workload created by Fi$Cal.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget for 2020‑21proposes an ongoing $2.3 million augmentation from various sources—including the Central Services Cost Recovery Fund, General Fund, and Service Revolving Fund—and 15 additional positions for CFS. Of these 15 positions, nine positions would provide accounting services to support four new client agencies and six positions would create a strike team to consult and assist other state agencies with accounting in the Fi$Cal system. (In addition to these resources, the Governor’s budget provides resources to several other departments for support of various Fi$Cal‑related activities.)

Assessment

Below, we provide our assessment of the six positions proposed for the CFS Strike Team. We do not have concerns with the nine additional staff proposed to provide accounting services for the four new client agencies.

Some Overlap Between Strike Team and Department of Fi$Cal Activities. We find that the activities proposed for the CFS Strike Team—providing other state departments assistance operating within the Fi$Cal system—are similar to those proposed to be undertaken by the Department of Fi$Cal with the funding approved in 2019‑20. For example, both proposals include providing training for departments on accounting in Fi$Cal. Accordingly, it will be important for the Legislature to consider the proposed CFS Strike Team in the context of the resources that have already been provided to the Department of Fi$Cal.

Uncertain Level of Ongoing Strike Team Workload. We find that there is uncertainty regarding the amount of ongoing workload for the CFS Strike Team. In particular, we would expect that the CFS Strike Team’s workload could vary over time depending on various uncertain factors, including: (1) how much departments use the resources provided to the Department of Fi$Cal for similar activities, (2) the level of additional resources departments directly receive to support their transitions to Fi$Cal and how such resources affect departments’ needs for assistance from DGS, and (3) the pace of additional department transitions to Fi$Cal.

Importance of Oversight of Fi$Cal Implementation. We find that continued legislative oversight over the implementation of Fi$Cal is particularly important given the challenges that departments have experienced thus far transitioning to Fi$Cal. As part of this oversight, it will be important for the Legislature to understand how much departments are using CFS’s Strike Team—as well as Department of Fi$Cal’s resources—to support their accounting activities.

Recommendation

Approve Funding for Fi$Cal Strike Team on a Two‑Year Limited Term Basis. We recommend that the Legislature approve the funding for the six‑person CFS Strike Team on a two‑year limited‑term basis, rather than on an ongoing basis, as proposed by the Governor. If DGS determines continued resources are required at the end of this limited‑term funding, it can request funding for additional years at that time.

After the two‑year period, the administration should be able to provide information on how the resources provided to implement Fi$Cal—including those provided to the CFS Strike Team, Department of Fi$Cal, and other departments that have received Fi$Cal‑related augmentations—have been used thus far and the outcomes they have achieved. This information should enable the Legislature to make a more informed decision regarding whether ongoing resources are needed for the CFS Strike Team. Additionally, this information should assist the Legislature with its ongoing oversight over the progress of the Fi$Cal project.

Construction of Sacramento Office Buildings: Resources, Bateson, and Unruh Projects

Background

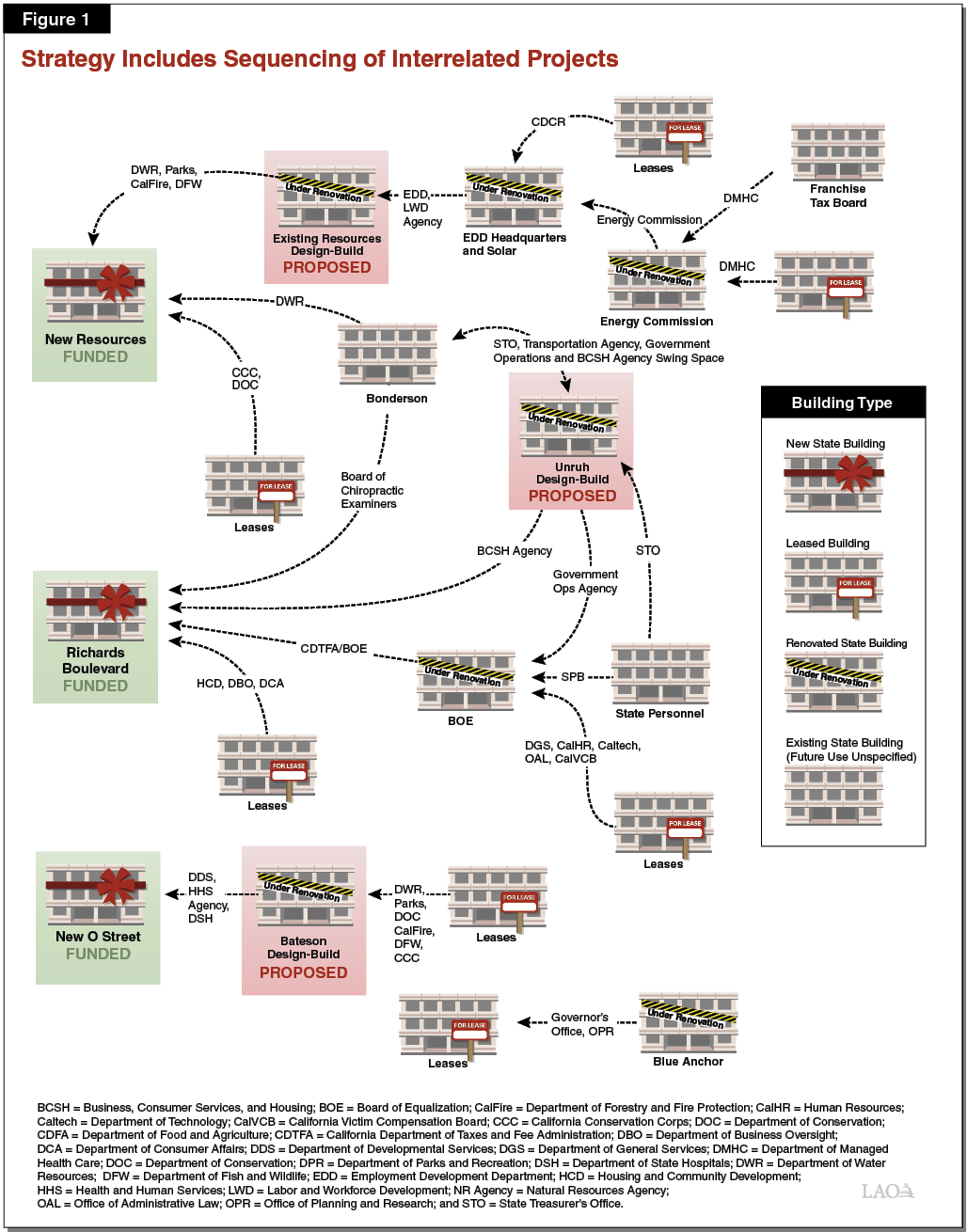

Administration Developed a State Office Building Strategy for Sacramento. As part of the 2014‑15 budget, the administration proposed and the Legislature approved funding for a study of state office buildings in the Sacramento area, which was to include assessments of the condition of state facilities, a plan for sequencing the renovation or replacement of state office buildings in Sacramento (State Office Building Strategy), and a plan for funding these activities. DGS completed the State Office Building Strategy in March 2016 and made some minor revisions to it in 2018. The State Office Building Strategy includes building three new state office buildings and renovating eight existing state office buildings within about ten years. The projects in the State Office Building Strategy are interrelated as shown in Figure 1. This is because the administration is proposing to strategically sequence building renovations by successively conducting staff moves and building renovations in order to reduce costs and disruptions associated with moving departments into and out of temporary space. (In addition to these projects, the state is also undertaking a renovation of the State Capitol Annex and construction of a new “swing space” office building to temporarily house staff from the Annex, but these projects are proceeding separately.)

Administration Using Design‑Build Approach. The administration has been using the design‑build project delivery approach for the construction of the projects included in the State Office Building Strategy. Under this approach, the construction contract is not awarded to the lowest bidder. Instead, once the performance criteria are complete, DGS determines the amount to provide to the contractor—the stipulated sum—for completing the final designs and constructing the project (known as the design‑build phase). Next, contractors submit detailed proposals that meet the requirements outlined in the performance criteria and can be completed within the amount of the stipulated sum. Finally, DGS evaluates these proposals based on various criteria, such as environmental sustainability.

Significant Funding Has Been Provided for Strategy. Since 2016‑17, the state provided a total of roughly $1.9 billion to support the State Office Building Strategy. This included the approval of roughly $20 million from the General Fund in 2018‑19 and 2019‑20 for the initial planning phase—known as the performance criteria phase—for the renovation of three office building projects in the Sacramento area that are part of the State Office Building Strategy: (1) the Resources Building, (2) the Bateson Building, and (3) the Unruh Building. When the Legislature approved funding for performance criteria for these projects, their total project costs were estimated to be $627 million—$376 million for the Resources Building renovation, $161 million for the Bateson Building renovation, and $90 million for the Unruh Building renovation.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget includes $721.7 million in lease revenue bond authority in 2020‑21 for the design‑build phase of three projects that are part of the administration’s State Office Building Strategy. This would bring the total project cost for these three projects to $742.1 million. The Governor’s specific proposals include:

- Resources Building Renovation ($421.3 Million). The budget provides $421.3 million for the design‑build phase of the renovation of the Resources Building, a 520,000 net useable square foot building constructed in 1964. The total cost of the project is estimated at $430.2 million.

- Bateson Building Renovation ($183.6 Million). The budget provides $183.6 million for the design‑build phase of the renovation of the Bateson Building, a 215,000 net useable square foot building constructed in 1981. The total cost of the project is estimated at $188.8 million.

- Unruh Building Renovation ($116.8 Million). The budget provides $116.8 million for the design‑build phase of the renovation of the Unruh Building, a 125,000 net usable square foot building constructed in 1929. The total cost of the project is estimated at $123.1 million.

Assessment

When Originally Proposed, Renovations Appeared to Be Expensive . . . In our report, The 2018‑19 Governor’s Budget: Department of General Services, we analyzed proposals to fund the performance criteria for the Bateson and Unruh Building renovation projects. At that time, we found that the projects appeared to be expensive relative to past state office building projects. For example, we found that, after adjusting for inflation in construction costs, these renovations were significantly more expensive than the Library and Courts Building—a historic building that DGS indicated it used as a basis for its cost estimates. When proposed in 2019‑20, the renovation of the Resources Building was roughly the same cost as the Bateson and Unruh Building renovations on a square footage basis, raising similar concerns about the relative expense of the building.

. . . But Are Now Expected to Be Even More Costly. Since the Legislature approved funding for the performance criteria phase for the Resources, Bateson, and Unruh renovation projects, the estimated costs of these projects have increased significantly. Specifically, the cost of the Resources Building renovation has increased by 14 percent, the cost of the Bateson Building renovation has increased by 17 percent, and the cost of the Unruh Building renovation has increased by 37 percent. These increases bring the cost per square foot of these renovations to be between about $825 and $1,000 per net useable square foot ($650 and $750 per gross square foot).

In our discussions with DGS, the department cited numerous reasons for the cost increases for these projects, including worse building conditions than previously assumed, a tight labor market for construction workers, and changes in buildings standards. Additionally, DGS indicated that its use of the Library and Courts project as a basis for estimating the renovation costs of other projects was problematic, since that project was not as extensive of a renovation as the proposed projects. In particular, according to DGS, the Library and Courts project did not replace all of the key building components, such as elevators. However, the Resources, Bateson, and Unruh renovation projects envision full replacements.

Options to Contain Costs Available. If the Legislature is not comfortable with the cost increases for the Resources, Bateson, and Unruh renovation projects, but would like to continue to move forward with the projects, there are a few possible options. Specifically, the Legislature could consider directing DGS to:

- Reduce Extent of Renovations. The Legislature could consider taking an approach similar to the Library and Courts Building renovation—not replacing all the key building components. This approach would reduce project costs, although some of these costs would potentially be borne at a future date when the building components reach the end of their useful life. As evidenced by the Library and Courts building, this approach can still result in a high‑quality renovation.

- Employ Less Expensive Materials. The Legislature could consider directing DGS to use less expensive materials, such as finishes, in some areas. Again, these choices could have trade‑offs in some cases, since some higher grade finishes also last longer or have lower ongoing maintenance costs.

- Delay Projects Until Labor Market Is Less Impacted. The Legislature could consider delaying a project. This would result in fewer projects happening simultaneously, which could help address the tight labor market for construction workers. However, it would delay the completion of the renovated building and affect the timing of other projects, since the State Office Building Strategy is generally interrelated. Furthermore, construction costs could continue to increase, if the construction labor market remains tight.

Recommendation

Require DGS to Report on Options to Contain Costs for Legislative Consideration. We recommend that the Legislature require DGS to report at budget hearings with further details on potential options—such as the ones we identified above—that could reduce the costs of these projects, along with their associated trade‑offs. This information would assist the Legislature in assessing whether to move forward with the original scope and time line of the Resources, Bateson, and Unruh renovation projects or make adjustments given the significant cost increases.

Deferred Maintenance

Background

DGS Facilities. DGS owns and maintains 56 office buildings that total roughly 16 million gross square feet. DGS buildings’ are located across the state, but roughly two‑thirds of the square footage of the buildings is in the Sacramento region. Other major metropolitan areas with a relatively large number of DGS buildings are the San Francisco Bay Area and the Greater Los Angeles Area.

DGS’ Building Rental Rates. DGS funds building maintenance costs, in addition to other costs associated with operating buildings (such as custodial and groundskeeping services), by charging monthly rental rates to the state departments that are tenants in these facilities. These rates are based on a number of factors (such as whether or not the building has outstanding bonds on it) and range from $2.29 per square foot to $7.93 per square foot. For example, DGS plans to generally charge state agencies that are tenants in the buildings without outstanding bonds a statewide standard building rental rate of $2.55 per square foot per month in 2020‑21.

Previous Budgets Provided Funding for DGS’ Deferred Maintenance Needs. When routine maintenance activities are delayed or do not occur, we refer to this as deferred maintenance. In 2015‑16, DGS identified a deferred maintenance backlog at its buildings totaling $138 million. In our March 2015 report The 2015‑16 Budget: Addressing Deferred Maintenance in State Office Buildings, we identified a few reasons for this deferred maintenance backlog. For example, we found that during the recent recession, DGS reduced rental rates in order to relieve costs to other state departments, which reduced funding available for maintenance activities and likely contributed to the accumulation of deferred maintenance. For example, the statewide standard building rental rate mentioned above was reduced by over one‑third, from $1.80 per square foot per month in 2008‑09 to $1.12 per square foot per month in 2011‑12. To help address the backlog that developed during this period, the state provided a total of $35 million from the General Fund for DGS’ deferred maintenance projects since 2015‑16

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposes about $80 million in one‑time General Fund support for deferred maintenance projects at DGS buildings. Of this amount, $56.4 million is for elevator modernizations at three state facilities (the Ronald M. George, Elihu Harris, and Ronald Reagan buildings) and $23.6 million is for fire alarm systems at five state facilities (the Edmund Brown, Van Nuys, Justice, Library and Courts II, and Franchise Tax Board Campus buildings). The budget also includes provisional language specifying that (1) the funding is available for elevator and fire alarm projects, (2) the funding is available only upon completion of Department of Finance’s review of DGS’ project design, and (3) if projects cost less than the amounts provided, the difference shall revert to the General Fund. The language, however, does not identify the specific facilities eligible for funding.

Assessment

Unclear if All Elevator Projects Represent Immediate Needs. We find that it is not clear whether all the specific projects proposed for funding need to occur immediately. Specifically, DGS cites facility condition assessments performed by a contractor in 2015 to support its request for elevator modernizations at three facilities—the Ronald M. George, Elihu Harris, and Ronald Reagan buildings. However, those studies found that the elevators in two of these three buildings—Ronald M. George Building and Elihu Harris Building—were not top priority projects and did not recommended them for immediate completion. For example, the report found that the elevators in the Elihu Harris building to be in “fairly good shape” due to above average maintenance at the facility, and recommended budgeting for modernization within 3 to 5 years given that parts could become more scarce in the coming years. While this means that the elevators are around their normal modernization cycle, it does not mean that the elevators represent an imminent safety concern or are not functional. Notably, neither the Ronald M. George Building and Elihu Harris Building elevator projects appeared on lists of the department’s deferred maintenance projects that the Legislature has received in past years.

Facility Condition Assessments Identified Lower Costs Than Proposal. The facility condition assessments on the Ronald M. George, Elihu Harris, and Ronald Reagan buildings identified much lower costs for the recommended elevator modernizations at these three buildings than are reflected in DGS’ proposal. Specifically, the facility condition assessments estimated that the costs of the elevator projects at these three buildings would total about $13 million, which is roughly one‑quarter the cost identified in DGS’ proposal. It is not clear to us whether this difference is because the consultant envisioned less comprehensive modernization efforts than DGS or whether the differences are due to other factors, such as poor cost estimation. This suggests that there is uncertainty about the cost of the projects and it is possible that there could be significant unspent funds. While the Governor’s provisional language attempts to address this possibility, it does not limit the use of the funds to the projects at the three specific buildings identified by the department. Accordingly, if the Legislature is comfortable funding one or more elevator projects, it will want to limit the use of the funds and ensure that they are not spent on other elevator projects that were not specified in the proposal, since some of them may be lower priority.

General Fund Not an Appropriate Funding Source to Support DGS Buildings on Regular Basis. Building rates are intended to reflect the cost of operating and maintaining buildings. It has been reasonable for the Legislature to provide some limited funding on a short‑term basis to help DGS address its most critical deferred maintenance needs, particularly those that were deferred when the department kept rates artificially low during the recession. However, we find that it is not appropriate for DGS to rely on General Fund augmentations on a long‑term basis to fund its deferred maintenance needs for a couple of reasons. First, this funding approach disconnects the rental rates paid by departments from the costs of operating and maintaining buildings, which reduces the department’s incentive to be a good steward of its buildings. Second, this approach places a disproportionate share of costs on the General Fund, rather than allocating some costs to the special funds that support some DGS tenants and therefore should bear some of these costs.

Unclear Why Backlog Has Changed Over Time. If the department has an effective ongoing maintenance program, we would expect that the size of its deferred maintenance backlog would decline over time as additional funding is provided to address it. However, DGS’ reported backlog has grown from $138 million to $544 million between 2015‑16 and 2020‑21, despite the state providing $35 million to address the backlog since 2015‑16. It is unclear whether these changes in DGS’ reported backlog represent actual changes in deferred maintenance needs across years or are a result of differences in how deferred maintenance is catalogued or reported by the department.

It is important to understand what is leading to these changes in the reported backlog because it might point to different legislative responses. For example, if changes in the department’s backlog represent actual differences in accumulated needs, it might suggest that DGS’ routine maintenance activities are insufficient and that it should improve its maintenance program. However, if the changes are a result of a new reporting methodology, it raises questions about the department’s process for identifying and cataloging deferred maintenance.

Recommendations

Reject Funding for Two Non‑Urgent Elevator Projects. We recommend that the Legislature only approve funding for the most critical, urgent deferred maintenance projects, since the General Fund should not be used on a long‑term basis to fund DGS building needs. Less urgent projects should generally be planned for in advance and funded over a period of time through DGS’ rates structure. This approach would more fairly apportion their costs across various funds and also create better incentives for the department to be a good steward of its buildings. Consistent with this approach, we recommend that the Legislature reject the $35.4 million (General Fund) proposed for the Elihu Harris and Ronald M. George Building elevator projects. While these specific projects may be worthwhile, it is not clear they represent immediate, critical needs. (We are not raising concerns with the $44.7 million for the Ronald Reagan Building elevator project and the fire alarm system projects, since the department and the facility condition assessments better support the urgency of these projects.)

Modify Provisional Language to Limit Use of Elevator Funding to Specific Projects. Given the differences in the cost estimates for elevator projects reflected in the facility condition assessments and DGS’ proposal, which suggest the actual project costs could be less than estimated, we recommend that the provisional language be modified to identify the specific facilities eligible for the elevator project funding—such as the Ronald Reagan Building. This will ensure that, if the specific elevator project or projects that the Legislature approves are ultimately less costly than proposed, the unused funds would return to the General Fund rather allowing DGS to use the funds on other elevator projects that may be of less urgency.

Require DGS to Report on Plan for Maintaining Facilities and Adjusting Rates to Reflect Actual Costs. We recommend that the Legislature direct DGS to report at budget hearings on why the department’s reported backlog of deferred maintenance has increased dramatically, and how the department will prevent the further accumulation of deferred maintenance. It will be important for the Legislature to have this information given that DGS’ deferred maintenance needs have grown substantially in recent years despite multiple allocations of deferred maintenance funding. We further recommend that the Legislature direct DGS to report on its plan for adjusting future building rates to address its backlog of deferred maintenance projects—including the Elihu Harris and Ronald M. George building elevators—over time, rather than continuing to rely on General Fund augmentations.