LAO Contacts

Corrected 2/20/20: Corrected to remove Alameda County from the list counties participating in the Coordinated Care Initiative.

February 14, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget:

Analysis of the Medi-Cal Budget

- Introduction

- Background

- Overview of the Governor’s Budget

- Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Regulation

- Update on Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services

- Full‑Scope Expansion for Seniors Regardless of Immigration Status

- SNF Rate Reform

- County Administration

- Proposal to End Dental Managed Care in the Two Pilot Counties

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

Overall Medi‑Cal Budget Picture. The Governor’s budget proposes $25.9 billion General Fund ($103.5 billion total funds) in 2020‑21, an increase of $2.9 billion (12.4 percent) over estimated 2019‑20 levels. This increase reflects both a number of workload budget adjustments that increase General Fund costs along with new funding to support several policy proposals. Notably, the Governor proposes $348 million General Fund ($695 million total funds) to implement the provisions of a broad set of Medi‑Cal reform proposals collectively referred to as “Medi‑Cal Healthier California for All.” We do not assess these reform proposals in this report, but will do so in a separate forthcoming report.

Administration Recently Submitted a Modified Managed Care Organization (MCO) Tax Proposal for Federal Consideration. For a number of years, the state has imposed a tax on MCOs. Revenues from the MCO tax result in a significant annual General Fund benefit—most recently, nearly $1.3 billion. The MCO tax expired at the end of 2018‑19 and the Legislature reauthorized a new MCO tax in 2019. Because the MCO tax would increase federal Medicaid funding, it requires federal approval. In late January 2020, the federal government rejected the state’s original MCO tax proposal. In early February 2020, the administration—using authority in the MCO tax’s reauthorizing legislation—modified the MCO tax and submitted a new proposal to the federal government. The modified MCO tax proposal would generate a smaller annual General Fund benefit ($1.3 billion to $1.7 billion) than the original proposal (around $2 billion) and have different impacts on MCOs’ tax liability. Federal approval of the modified MCO tax remains uncertain. (We note that as the Governor’s budget does not assume the receipt of revenues from the reauthorized tax until 2021‑22, the fiscal impact of the ultimate federal decision on the state’s proposal will not affect the Governor’s budget structure until 2021‑22.)

Draft Federal Regulation Could Have Significant Fiscal Effects for Medi‑Cal. In October 2019, the federal government released draft regulations related to financing and oversight in the Medicaid program. The draft rule, if implemented in its current or similar form, would require significant changes to major Medi‑Cal financing mechanisms, possibly resulting in several billion dollars of higher General Fund costs. (The modified MCO tax discussed earlier, however, could be approved under existing federal rules.) The ultimate impact of the proposed regulations is highly uncertain and depends on what provisions are in the final rule and how the federal government elects to implement them. However, given the potential for a significant fiscal impact on Medi‑Cal financing, we recommend that the Legislature approach proposals to significantly increase ongoing General Fund expenditures in the 2020‑21 budget with caution.

Governor’s Budget Includes Various Proposals Intended to Result in Pharmacy Savings. This report analyzes the Governor’s pharmacy‑related proposals that implicate Medi‑Cal and the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), including (1) changes to facilitate the transition of Medi‑Cal pharmacy services from a managed care to a fee‑for‑service (FFS) benefit, which include proposed supplemental payments for clinics to mitigate associated financial losses, and (2) budget‑related legislation authorizing DHCS to collect rebates on drugs not paid for through Medi‑Cal. First, we find that the Governor’s savings estimate for the transition of Medi‑Cal pharmacy services to an FFS benefit likely is overstated. We recommend that the Legislature enact report requirements to ensure that this major policy change is achieving its objective of generating state savings. Additionally, we question whether the Governor’s proposed supplemental payments for clinics serve a public purpose in the long run, and recommend either making the payments temporary or, if made ongoing as proposed, tying them to quality and/or access improvements.

Governor Proposes Expanding Comprehensive Coverage for Income‑Eligible Seniors, Regardless of Immigration Status. Historically, income‑eligible undocumented immigrants only qualified for “restricted‑scope” Medi‑Cal coverage, which covers emergency‑ and pregnancy‑related health care services. Over the last several years, the Legislature has expanded comprehensive “full‑scope” Medi‑Cal coverage to undocumented children ages 0 through 18 and adults ages 19 through 25. The Governor proposes to expand full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to income‑eligible undocumented seniors ages 65 and older beginning in January 2021. The Governor projects $64 million will be needed to fund this half‑year expansion in 2020‑21. We project that this expansion will cost around $250 million on an ongoing basis, with this funding split between Medi‑Cal and the In‑Home Supportive Services program.

Proposed Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) Rate Reform Has Promise, But Many Questions Remain. The state’s current system for setting reimbursement rates for SNF sunsets in August 2020. The Governor proposes to reauthorize the rate‑setting system with several changes. Overall, these changes intend to increase the role of SNF quality in setting rates. The Governor also proposes to extend a quality assurance fee paid by SNF that offsets the General Fund costs of SNF reimbursement. We find that, in concept, better integrating quality incentives with rates could strengthen incentives for SNF to improve quality. However, many questions remain about the proposal, such as how the proposed rate system would function in the managed care environment. (The Governor has separately proposed transitioning SNF care to the managed care delivery system statewide.) We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on this proposal until more information is provided. Should the Legislature adopt the Governor’s proposal, we recommend requiring an evaluation of the new rate structure’s impact on SNF quality.

Increased Oversight of County Medi‑Cal Administration Is Warranted. Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was disruptive to county Medi‑Cal administration. Federal and state audits have identified deficiencies in county administration and the state’s oversight of these activities during and following ACA implementation. Further, the analytical basis for the state’s approach to budgeting for county administrative activities has significantly eroded. The Governor proposes to provide a cost‑of‑living adjustment for county administration funding (consistent with recent practice) with no other changes to the state’s budgeting methodology. The Governor further proposes to reinstate and build on county oversight processes that previously were suspended. We recommend that the Legislature require the administration to provide an update on county performance and efforts to improve performance prior to approving the Governor’s proposals. We further recommend that the Legislature adopt a plan for revising the budgeting methodology for county Medi‑Cal administration.

Proposal to End Dental Managed Care. For over 25 years, the state has operated a dental managed care pilot program in Sacramento and Los Angeles Counties whereby Medi‑Cal dental services are accessed through specialty dental managed care plans rather the typical Medi‑Cal dental FFS delivery system. The Governor proposes to end the dental managed care pilot program and transition Medi‑Cal dental services to FFS in the two pilot counties. In our assessment, dental managed care has not achieved its objectives of achieving savings while ensuring access and quality. Accordingly, we recommend approval of the Governor’s proposal assuming no information is obtained during the budget process that shows clear improvement in the dental managed care plan performance.

Introduction

Report Provides Assessment of Overall Medi‑Cal Budget Proposal… With proposed General Fund expenditures of nearly $26 billion, Medi‑Cal is one of the largest items in the state’s budget. This report provides a broad overview of the major spending changes reflected in the Governor’s proposed Medi‑Cal budget, as well as analysis and recommendations on several proposals for legislative consideration.

…But Does Not Assess Medi‑Cal Healthier California for All. This report does not provide analysis and recommendations on the Governor’s proposed broad Medi‑Cal reform effort, referred to as “Medi‑Cal Healthier California for All” (MHCA). We will provide our comments on that reform proposal in a separate forthcoming report.

Layout of This Report. This report begins with some high‑level background on the Medi‑Cal program, followed by an overview of the major drivers of year‑over‑year spending changes in the Governor’s budget. We also discuss the administration’s recent submittal (late January 2020) of a modified managed care organization (MCO) tax proposal. Following this section, we provide analysis and recommendations on a series of key issues:

- Recently proposed draft federal regulations referred to as the “Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Regulation.”

- Proposals related to the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit.

- The Governor’s proposal to expand comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible seniors regardless of immigration status.

- Proposed changes to rate‑setting for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).

- Issues related to county administration of eligibility and enrollment functions in Medi‑Cal.

- The Governor’s proposal to end dental managed care in the current two pilot counties and instead provide dental care as a fee‑for‑service (FFS) benefit statewide.

We conclude this report with a summary table of our recommendations.

Background

Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, is administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and provides health care coverage to almost 13 million of the state’s low‑income residents. Coverage is cost‑free for most Medi‑Cal enrollees. Instead, Medi‑Cal costs generally are shared between the federal, state, and local (county) governments.

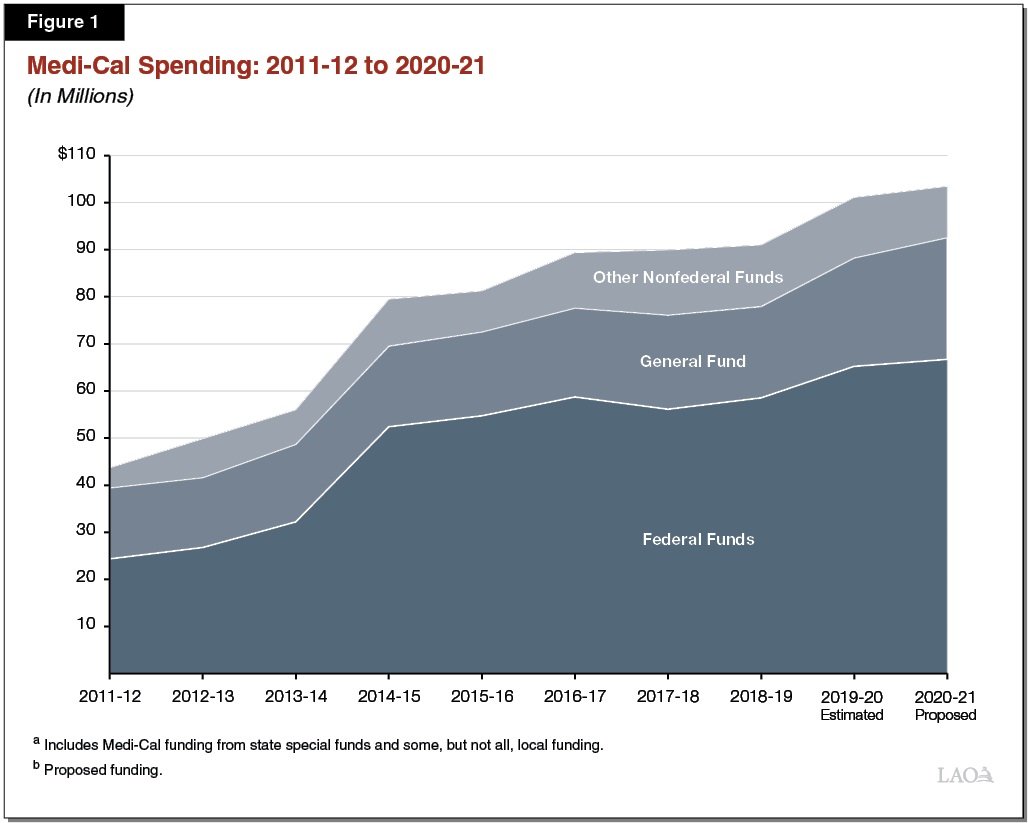

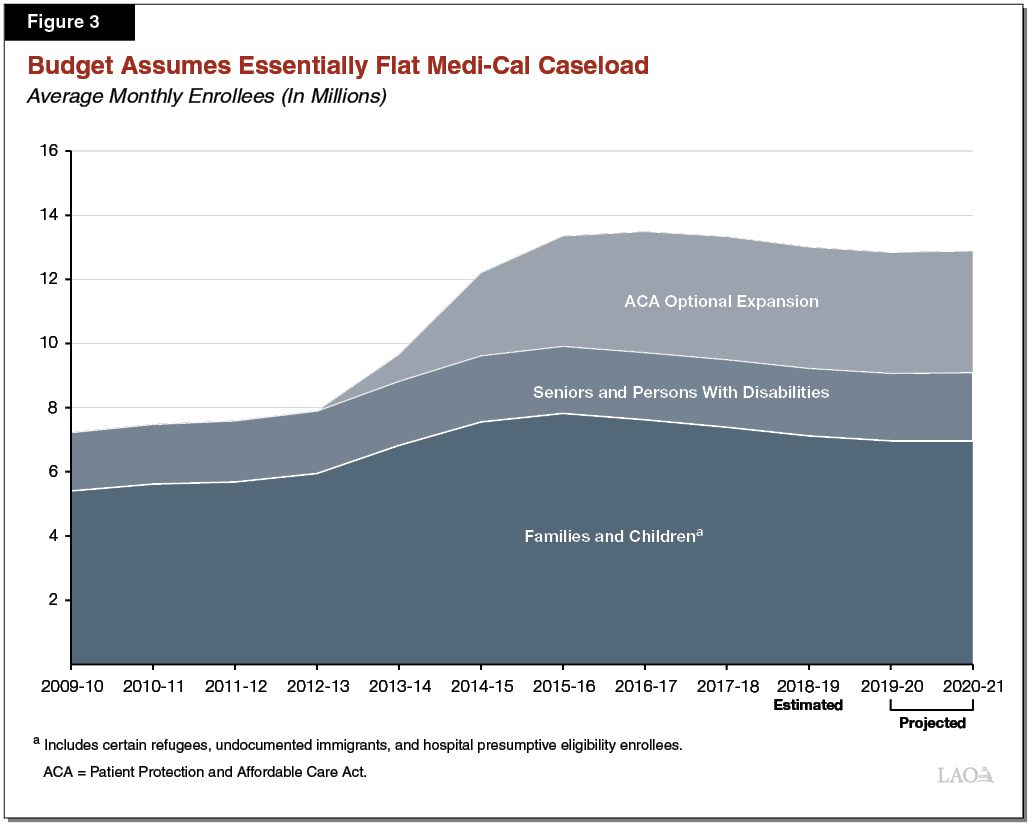

Medi‑Cal Has Grown Significantly Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Before 2014, Medi‑Cal eligibility mainly was restricted to low‑income families with children, seniors, persons with disabilities, and pregnant women. As allowed under the ACA, in 2014, the state expanded Medi‑Cal eligibility to include additional low‑income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program. This eligibility expansion sometimes is referred to as the “ACA optional expansion.” Medi‑Cal has grown significantly both in terms of caseload and spending as a result of the ACA optional expansion and the other changes under the ACA to encourage health care coverage. Figure 1 shows the growth in Medi‑Cal spending over the last decade. Figure 3, found later in this report, shows the significant increase in Medi‑Cal caseload from nearly 8 million enrollees to over 13 million enrollees in the years following implementation of the ACA, with the caseload leveling off recently.

Federal Share of Cost Varies, Primarily by Eligibility Group. The costs of state Medicaid programs generally are shared between the federal government and states based on a set formula. The percentage of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government is known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP).

For most low‑income families and children, seniors, persons with disabilities, and pregnant women, California generally receives a 50 percent FMAP—meaning the federal government pays half of Medi‑Cal costs for these populations. For the subset of children in families with higher incomes that qualify for Medi‑Cal as part of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the federal government pays 76.5 percent of the costs and the state pays 23.5 percent. (The state share is scheduled to ramp up to the historical cost share of 35 percent over the coming years.) Under the ACA, the federal government paid 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to the ACA optional expansion population from 2014 through 2016. Beginning in 2017, the federal cost share decreased to 95 percent and phases down further to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter.

Delivery Systems. There are two main Medi‑Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi‑Cal FFS generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi‑Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans to provide health care coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person per month, regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi‑Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi‑Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health care services in a timely manner. Managed care enrollment is mandatory for most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, meaning these beneficiaries must access most of their Medi‑Cal benefits through the managed care delivery system. FFS enrollment largely consists of newly enrolled beneficiaries who will soon enroll in a managed care plan and certain seniors and persons with disabilities. In 2019‑20, more than 80 percent of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are estimated to be enrolled in managed care.

Overview of the Governor’s Budget

Current‑Year Adjustments

Estimated General Fund Spending Down $92 Million in 2019‑20. The Governor’s budget projects that Medi‑Cal spending will be $92 million lower (0.4 percent) in 2019‑20 relative to what was assumed in the 2019‑20 Budget Act. This is a small current‑year adjustment relative to previous years. The downward adjustment primarily reflects (1) savings from reduced expected enrollment in the program and (2) a number of other, primarily technical adjustments that largely offset one another.

Budget‑Year Adjustments and Proposals

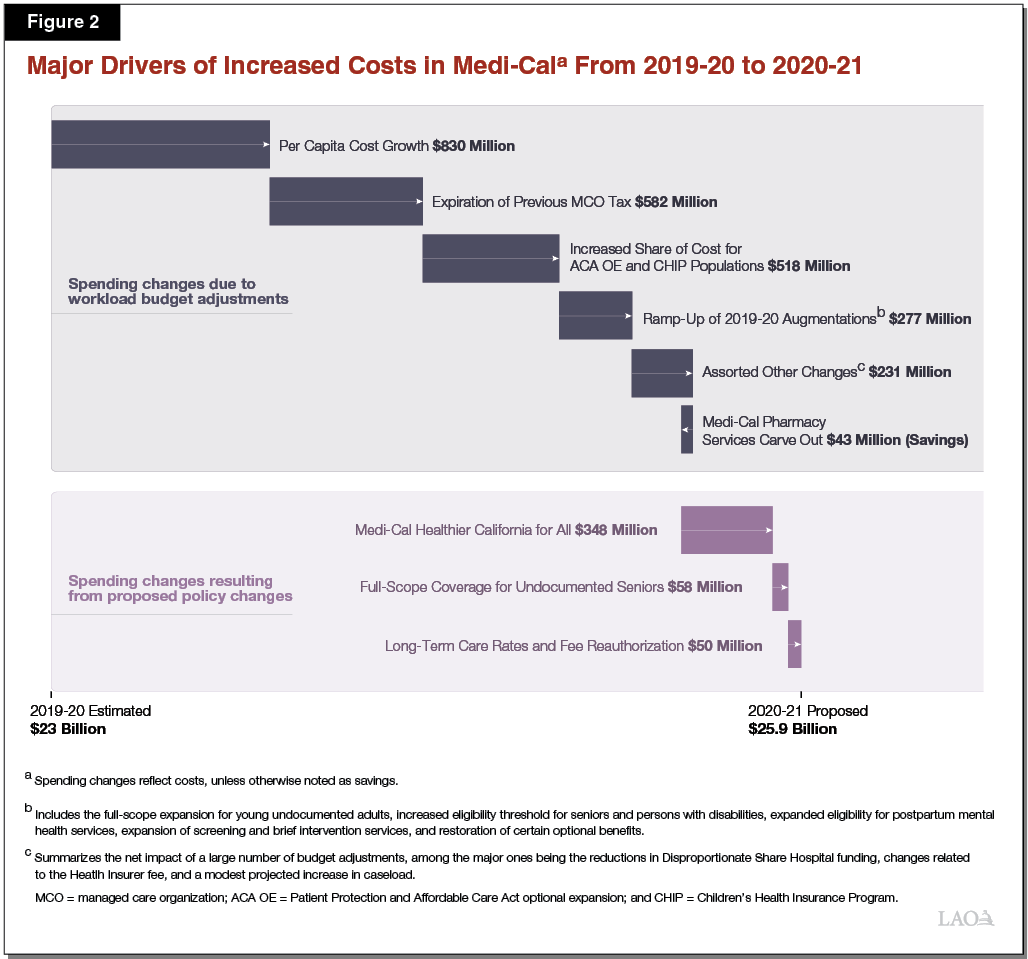

Under the Governor’s proposed budget, General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal would grow from $23 billion in 2019‑20 to $25.9 billion in 2020‑21—a $2.9 billion, or 12.4 percent, increase in year‑over‑year spending. Figure 2 summarizes the major factors responsible for the proposed growth in General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal, which includes both workload budget adjustments and new policy proposals.

Workload Budget Adjustments. Most of this change in General Fund spending from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21 is due to workload budget adjustments. We describe several major adjustments below.

- Governor’s Budget Cautiously Assumes Caseload Essentially Will Be Flat Going Into 2020‑21. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor’s budget projects that the Medi‑Cal caseload will remain essentially flat in 2020‑21, growing only by 0.4 percent to an average of 12,880,440 enrollees per month. This assumption results in higher General Fund costs in the low tens of millions of dollars relative to 2019‑20. In our view, the Governor’s Medi‑Cal caseload estimates are cautious as we project that the caseload will continue to decline slowly, provided that the economy continues to expand. (In recent years, caseload declined by around 1 percent to 2 percent per year on average.) The Governor will provide updated caseload estimates in May, at which time we will reassess the reasonableness of the administration’s Medi‑Cal caseload assumptions.

- Per Capita Cost Growth. We estimate that per capita cost growth accounts for $830 million of the increase in spending relative to 2019‑20.

- MCO Tax. The Medi‑Cal budget reflects a $582 million increase relative to 2019‑20, due to the expiration of the previous MCO tax and the Governor’s budget assumption that revenues from the MCO tax recently reauthorized by the Legislature would not materialize until 2021‑22.

- Scheduled Reductions in Federal Share of Costs. We estimate that the Medi‑Cal budget reflects a $518 million increase in spending relative to 2019‑20 due to scheduled changes in the federal share of costs for the ACA optional expansion and CHIP populations.

- Ramp‑Up of 2019‑20 Augmentations. The Medi‑Cal budget reflects a $277 million increase in spending relative to 2019‑20 due to continued implementation of 2019‑20 augmentations. These augmentations include (1) the expansion of full‑scope Medi‑Cal to otherwise eligible young adults regardless of immigration status, (2) an increased income eligibility threshold for certain seniors and persons with disabilities, (3) expanded eligibility for postpartum mental health services, (4) expansion of screening and intervention for substance use disorder services, and (5) the restoration of certain optional Medi‑Cal benefits.

- “Disproportionate Share Hospital” Reduction. The Medi‑Cal budget reflects an $83 million reduction in spending on payments to private disproportionate share hospitals, which serve large numbers of low‑income or uninsured populations. This state reduction is triggered by a scheduled reduction in federal funding for payments the state largely directs to public disproportionate share hospitals. (Congress has repeatedly delayed the scheduled federal reduction and may do so again. If this happens, the General Fund savings identified in the Governor’s budget on payments to private disproportionate share hospitals may be reduced or may not materialize at all.)

New Policy Proposals. Nearly $490 million of the increase in General Fund spending is attributable to new discretionary policy proposals that are included in the Governor’s budget.

- MHCA. The administration’s recently introduced MHCA proposal intends to significantly overhaul the state’s Medi‑Cal system, and introduces new benefits intended to provide more comprehensive care to patients with more complex health needs. The Medi‑Cal budget proposes spending $348 million from the General Fund ($695 million total funds) in 2020‑21 to implement MHCA. Under the Governor’s proposal, spending would double to $695 million General Fund ($1.4 billion total funds) in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. Beginning in 2023‑24, ongoing annual costs would be $395 million General Fund ($790 million total funds).

- Expansion of Comprehensive (“Full‑Scope”) Medi‑Cal Coverage to Seniors Regardless of Immigration Status. The administration proposes extending comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to income‑eligible seniors aged 65 and older regardless of immigration status. The Medi‑Cal budget provides $58 million in 2020‑21 to implement this proposal for a half year. On an annual basis, we project Medi‑Cal General Fund costs for the expansion to be around $110 million.

- SNF Rate Reform. The administration proposes reforming the way in which SNF rates are set. In recent years, SNF rates have received an annual increase and the Governor’s proposal would continue this practice. However the Governor additionally proposes providing an additional midyear rate increase in 2020‑21, related to transitioning SNF rate setting from a state fiscal‑year basis to a calendar‑year basis. Budget documents released on January 10, 2020 indicate that the General Fund cost of this midyear increase will be around $50 million in 2020‑21. The ongoing costs of this midyear adjustment would be roughly double this amount.

- Supplemental Payment Pool for Clinics to Mitigate Loss in Earnings Due to Changes to Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services. To mitigate the loss in earnings for clinics due to changes to Medi‑Cal pharmacy services, the Governor proposes half‑year funding of $26 million General Fund ($53 million total funds) to create a new supplemental payment program.

Administration Recently Resubmitted a Modified MCO Tax Proposal

Background. For a number of years, the state has imposed a tax on MCOs’ Medi‑Cal and commercial lines of business. This tax historically raised significant special fund revenues ($2.6 billion in 2018‑19), which generate a General Fund benefit (most recently, nearly $1.3 billion in 2018‑19) by offsetting a portion of General Fund expenditures in Medi‑Cal. Following the expiration of the most recent MCO tax, which was in place from 2016‑17 through 2018‑19, the Legislature reauthorized the MCO tax last year under a somewhat modified structure from the previous tax. The reauthorized MCO tax would generate a General Fund benefit of $1 billion to $2 billion annually from 2019‑20 to 2023‑24. Because the reauthorized MCO tax would increase federal Medicaid funding, it requires federal approval. For more information on the reauthorized MCO tax, see our Budget and Policy Post: The 2019‑20 Budget: California Spending Plan—Health and Human Services.

Governor’s Budget Assumes a Delayed Implementation of the Reauthorized MCO Tax. Due to uncertainty regarding the timing of federal approval of the reauthorized MCO tax, the Governor’s budget assumed a delay in when the General Fund benefit from the reauthorized MCO tax would materialize. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget assumes the General Fund benefit from the MCO tax would materialize in 2021‑22 rather than in either 2019‑20 or 2020‑21.

Federal Government Rejected the State’s Initial Proposal for a Reauthorized MCO Tax. In late January 2020, after the release of the Governor’s budget, the federal government notified the state of its decision to reject the state’s proposal for a reauthorized MCO tax. The federal government rejected the reauthorized MCO tax proposal under existing federal rules. Based on our understanding, the federal government rejected the state’s proposal, at least in part, due to the reauthorized tax not imposing any liability on MCOs that do not have Medi‑Cal membership, thereby—in the federal government’s view—violating the no‑hold harmless requirement in existing federal law.

Administration Has Submitted a Modified MCO Tax Proposal for the Federal Government to Consider. In the reauthorizing legislation for the MCO tax, the Legislature gave the administration authority to modify the structure of the MCO tax in order to gain federal approval, provided that the modifications do not significantly increase the total tax amounts projected to be collected under the tax. The administration has used this authority and, in early February, resubmitted a modified MCO tax proposal to the federal government for consideration.

To gain federal approval, the administration has modified the MCO tax proposal in a way that increases the net tax liability on a number of MCOs, specifically by lowering the enrollee threshold for taxation on non‑Medi‑Cal membership. In effect, this would increase the net liability on four MCOs that have no Medi‑Cal membership. By imposing a net liability on MCOs without Medi‑Cal membership, the state’s modified MCO tax proposal is intended to address the federal government’s principal objection to the structure of the recently rejected, original proposal.

Figure 4 compares the structure of the original and modified MCO tax structures. Figure 5 compares the fiscal impact in the first year of implementation. The net General Fund benefit of the modified MCO tax would be lower than that of the rejected tax. Rather than generating a General Fund benefit of up to around $2 billion on an annual basis, the modified MCO tax would generate a $1.3 billion to $1.7 billion General Fund benefit on annual basis. The lower benefit is largely due to effectively eliminating the tax on MCOs’ first 675,000 Medi‑Cal enrollees. Moreover, some MCOs will face higher net tax liability under the modified proposal, while others will face lower net tax liability. As with the original proposal, the modified proposal would be in place for 3.5 years.

Federal Decision, if Maintained, Significantly Raises the Amount of General Fund Needed for Medi‑Cal Beyond 2020‑21. If the state ultimately does not obtain federal approval on the modified MCO tax proposal, an additional $1 billion to $2 billion of General Fund would be needed annually to fully fund the Medi‑Cal program starting in 2021‑22. This amount is relative to the multiyear assumptions included in the Governor’s budget.

Figure 4

Comparing the Tax Rates of the Original and Modified MCO Tax Proposals

|

Member Monthsa |

Tax Rate Per Member Month |

|

|

Original Proposalb |

Modified Proposalc |

|

|

Medi‑Cal Enrollees |

||

|

1‑675,000 |

$40 |

— |

|

675,001‑4,000,000 |

40 |

$40 |

|

4,000,001 and above |

— |

— |

|

Commercial Enrollees |

||

|

1‑675,000 |

— |

— |

|

675,001‑4,000,000 |

— |

$1 |

|

4,000,001 to 8,000,000 |

$1 |

— |

|

8,000,001 and above |

— |

— |

|

aA member month is defined as one member being enrolled for one month in an MCO. bOriginal proposal refers to the MCO tax as reauthorized and proposed to the federal government for consideration in 2019. cModified proposal refers to the MCO tax as modified by the administration and proposed to the federal government for consideration in 2020. |

||

|

MCO = managed care organization. |

||

Figure 5

Comparing the Fiscal Impacts of the Original and Modified MCO Tax Proposals

LAO Estimates for First Full Year of Implementation (In Millions)

|

State Impact |

Original Proposala |

Modified Proposalb |

Difference |

|

Total MCO tax revenue |

$2,631 |

$2,063 |

‑$568 |

|

General Fund cost of Medi‑Cal reimbursement to MCOs |

‑915 |

‑714 |

201 |

|

Net General Fund Benefit |

$1,716 |

$1,349 |

‑$367 |

|

Health Insurance Industry Impact |

|||

|

MCO tax liability |

$2,631 |

$2,063 |

‑$568 |

|

Medi‑Cal reimbursement to MCOs |

‑2,614 |

‑2,040 |

574 |

|

Net Health Insurance Industry Liability |

$17 |

$23 |

$6 |

|

aOriginal proposal refers to the MCO tax as reauthorized and proposed to the federal government for consideration in 2019. bModified proposal refers to the MCO tax as modified by the administration and proposed to the federal government for consideration in 2020. |

|||

|

MCO = managed care organization. |

|||

Extends Potential Suspensions to 2023‑24

To prevent a potential General Fund operating deficit from arising in the years after 2019‑20, the 2019‑20 Budget Act adopted provisional suspension language that applies to a number of recent, mostly health and human services augmentations. Figure 6 lists the four Medi‑Cal augmentations subject to the suspension language. The 2019‑20 Budget Act’s provisional language suspends all of the augmentations subject to the language as of January 1, 2022 unless the Department of Finance determines in May 2021 that annual General Fund operating surpluses could accommodate all the augmentations over the next two fiscal years. The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposes to extend the effective date of the suspensions for one‑and‑a‑half years to July 1, 2023. Accordingly, the four Medi‑Cal augmentations listed in Figure 6 would be suspended starting in 2023‑24 unless the Department of Finance determines that there is sufficient General Fund to support all the augmentations subject to the suspension language in 2023‑24.

Figure 6

Medi‑Cal Augmentations Subject to

Potential Suspension

General Funds (In Millions)

|

Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal provider payment increasesa |

$819 |

|

Extension of Medi‑Cal coverage for postpartum mental health |

46 |

|

Medi‑Cal optional benefits restoration |

34 |

|

Expansion of screening and intervention in Medi‑Cal to drugs other than alcohol |

3 |

|

Total |

$902 |

|

aThe Proposition 56 funding for Medi‑Cal no longer supporting provider payment increases would be used to offset General Fund spending on cost growth in Medi‑Cal. |

|

Medicaid Fiscal Accountability Regulation

In October 2019, the federal government released draft regulations related to financing and oversight in the Medicaid program. These rules, if implemented in their current or a similar form, would require significant changes to major Medi‑Cal financing mechanisms, possibly resulting in several billion dollars of higher General Fund costs. These rules also would dramatically increase the amount and types of information the state would be required to report to the federal government. In this section, we provide background on how the nonfederal share of Medi‑Cal costs is financed and the major provisions of the proposed regulations. The provisions of the draft federal regulations are likely to change before being finalized, so the ultimate impact on the state is highly uncertain.

Medi‑Cal Is Partly Financed From a Variety of Non‑General Fund Sources

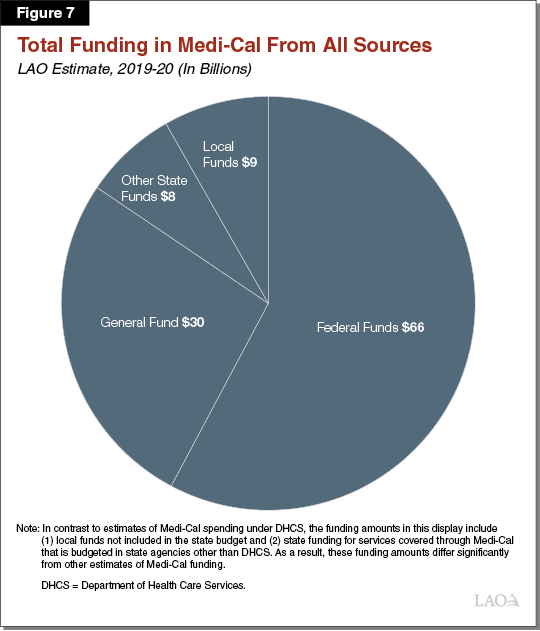

Figure 7 displays total funding for Medi‑Cal in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 under the Governor’s proposal. As shown in the figure, the state uses a variety of non‑General Fund sources to finance the nonfederal share of Medi‑Cal, including local funds, health care‑related taxes, and state special funds. We describe these nonfederal funding sources below.

Local Funds

Some Local Governments Operate Health Facilities That Serve Medi‑Cal Enrollees. Some local government entities in the state—including some counties, cities, and special districts—operate health care facilities, such as hospitals and clinics. These government‑operated facilities are part of the state’s health care “safety net,” a term which is sometimes used to refer to health care providers that provide care regardless of an individual’s health insurance coverage status or ability to pay for care. Medi‑Cal enrollees and the uninsured typically make up a large share of these providers’ patients. Local governments that operate health facilities receive payment through the Medi‑Cal program for the services that they provide to Medi‑Cal enrollees.

Local Governments Also Contribute Toward the Nonfederal Share of Medi‑Cal Costs. In addition to providing health care services to Medi‑Cal enrollees, local governments also contribute toward financing the nonfederal share of cost in Medi‑Cal. There are two mechanisms established in federal law through which local governments contribute to financing Medi‑Cal:

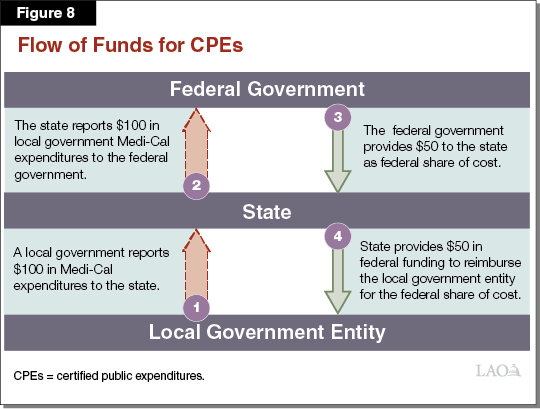

- Certified Public Expenditures (CPEs). Under the first mechanism, a local government incurs costs providing covered health care services to Medi‑Cal enrollees. The local government certifies to the state that expenditures were made and the state then makes a claim to the federal government to receive funding to cover the federal share of the expenditures. This federal funding is then used to reimburse the local entity for the federal share of the expenditure. As described earlier, the portion of Medi‑Cal expenditures covered by the federal government varies depending on the population being served. Figure 8 provides an example of how funds would flow through this CPE process assuming an FMAP of 50 percent. We estimate that CPEs account for around $3.1 billion in Medi‑Cal funding in 2019‑20.

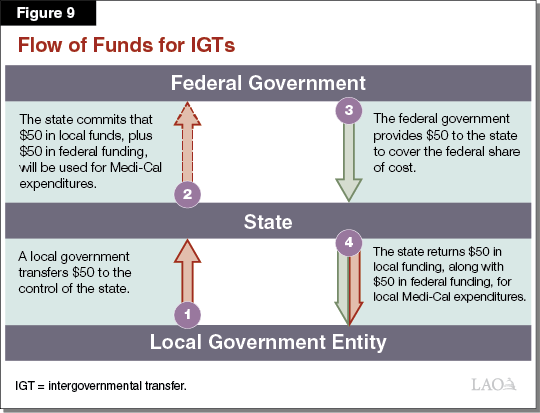

- Intergovernmental Transfers (IGTs). Under the second mechanism, local governments transfer funding to the control of the state, which then commits to the federal government that the funding will be used in the future for Medi‑Cal expenditures. The federal government provides the state funding to cover the federal share of cost of the future expenditures and the state then provides both the local funding and the federal funding to the local government for Medi‑Cal expenditures. Under current practice and consistent with federal approvals to date, funding that local governments provide as an IGT can come from various sources, such as revenue the local government entity receives from providing health care services and local tax revenues. Figure 9 provides an example of how funds would flow through the IGT process assuming an FMAP of 50 percent. We estimate that IGTs account for about $4.6 billion in Medi‑Cal funding in 2019‑20.

Funds From Health Care‑Related Taxes

Federal Government Currently Regulates Health Care‑Related Taxes. Many states levy licensing fees, assessments, or other mandatory payments on the provision of health care services or products. These are referred to as “health care‑related taxes.” Given its significant role in funding health care, the federal government has existing rules that regulate states’ health care‑related taxes to the extent that these are levied to draw down federal funds. The rules apply, for example, to taxes on direct health care services (such as hospital inpatient stays) as well as payers of health care services (such as health insurer revenue or enrollment).

The rules are in place to prevent states from imposing too disproportionate a burden on federal Medicaid funds to pay the tax. Therefore, to receive federal approval, a state must prove to the federal government that the burden of paying a health care‑related tax does not fall too disproportionately on Medicaid as opposed to non‑Medicaid services. Specifically, health care‑related taxes must pass a complex statistical test that determines whether the tax falls too disproportionality on federal Medicaid funds. To further ensure that the tax liability is distributed broadly among Medicaid and non‑Medicaid services, a state cannot hold payers of the health care‑related tax harmless by providing its payers direct or indirect payments to offset the tax. While a state may implement a health care‑related tax that violates federal rules, the federal government reduces funding for the state’s Medicaid program in proportion to the revenues raised by an impermissible tax, making imposition of such taxes highly unappealing.

Medi‑Cal Relies on Revenues From Several Health Care‑Related Taxes. California has—or until recently has had in place—several health care‑related taxes that, together, generate significant revenues that help finance the Medi‑Cal program and often serve to offset what would otherwise be General Fund costs. We describe these taxes below.

- MCO Tax. As previously discussed, in 2019, the state proposed for federal approval a reauthorized MCO tax that would generate a General Fund benefit of up to roughly $2 billion annually. While no revenues from the MCO tax are assumed in the Governor’s budget to offset General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal in either 2019‑20 or 2020‑21, the administration, in the January budget, assumes such revenues would offset General Fund Medi‑Cal spending starting in 2021‑22. As also noted, in early February of this year, the state submitted a modified MCO tax proposal following the federal government’s late‑January decision to reject the California’s original MCO tax proposal on the basis of current federal rules related to health care‑related taxes.

- Hospital Quality Assurance Fee (QAF). Under the hospital QAF, the state assesses a tax on private hospitals based on the amount of care they provide to Medi‑Cal enrollees and other populations (measured in terms of bed days), totaling a projected $3.5 billion in 2019‑20. Most of the QAF revenues are used to provide supplemental payments to private hospitals and a small amount of grant funding to public hospitals, increasing their total overall reimbursement for services provided to Medi‑Cal enrollees. Another portion of the hospital QAF funding is kept by the state to offset what otherwise would be General Fund costs, a projected $914 million in 2020‑21. The Legislature first established the hospital QAF in 2009. The hospital QAF was later reauthorized by the Legislature several times. In 2018, voters approved Proposition 52, which made permanent the statutory authority for the state to assess the hospital QAF and provide the associated supplemental payments and grant funding. However, the state is required to seek federal approval for adjustments to the QAF and related supplemental payments every few years.

- Other Provider Fees and Taxes. The state has a few other, relatively minor, provider taxes, listed below:

- SNF QAF. The state assesses a fee on SNF bed days that is used to offset the state’s General Fund costs for SNF services in Medi‑Cal. The SNF QAF is projected to raise $505 million in 2019‑20.

- Ground Emergency Medical Transportation (GEMT) QAF. The state assesses a fee on GEMT that is used to raise reimbursement levels for GEMT providers and offset what otherwise would be General Fund costs in Medi‑Cal. The GEMT QAF is projected to raise around $200 million in 2019‑20.

- Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) QAF. The state assesses a fee on the gross receipts of certain ICFs that is used to offset state costs for ICF services. The ICF QAF is projected to raise $35 million in 2019‑20.

Other Special Funds

In addition to local funds and revenues from health care‑related taxes, the state relies on a number of other state special funds to finance the nonfederal share of cost in Medi‑Cal. For example, Medi‑Cal’s most significant source of other state special fund revenue is from state taxes on tobacco products, including the approximately $1 billion in Proposition 56 (2016) revenue that supports provider payment increases in Medi‑Cal.

As Proposed, Federal Regulations Would Change Medicaid Financing and Oversight

Below, we describe provisions of the draft federal regulations that would have the greatest impact on Medi‑Cal.

Changes Related to Allowable Sources of Funding

The draft regulations significantly change what the federal government would allow as a source of nonfederal funding for Medi‑Cal.

- Would Limit Use of State Special Funds. The draft regulation specifies that state funding for Medi‑Cal would need to come from the General Fund, which would appear to preclude the possibility of the state using state special funds, such as those that receive tobacco tax revenues, to finance Medi‑Cal.

- Would Limit Permissible Sources of IGTs. The draft regulation also specifies that the source of IGTs would be limited to state and local government tax revenues. This limitation would exclude local governments’ patient care revenue—a very significant source of funding for IGTs under current financing structures.

Changes Specific to Health Care‑Related Taxes

New Proposed Rules Would Prohibit Health Care‑Related Taxes From Placing an Undue Burden on Medicaid. As previously noted, the federal government already has rules that effectively prohibit health care‑related taxes if the tax burden falls too disproportionately on Medicaid as opposed to non‑Medicaid services. Under the proposed federal regulations, the federal government would add additional, nonstatistical tests beyond the existing statistical test to determine whether a health care‑related tax falls too disproportionately on Medicaid services. These additional tests would effectively prohibit health care‑related taxes that place different tax rates on taxpayers based on their levels of Medicaid (versus non‑Medicaid) activity. In addition, the new federal rule would give the federal government significant discretion—beyond the tests—to determine whether a proposed health care‑related tax places an undue burden on Medicaid as opposed to non‑Medicaid services.

Significantly Increases Reporting Requirements

The draft regulations would significantly expand the amount and types of information the state would be required to provide to the federal government. These new reporting requirements could result in significant new state costs.

Requires Provider‑Level Reporting on Supplemental Payments. The state provides supplemental payments (that is, payments on top of base rates that increase overall compensation) to various Medi‑Cal providers, and currently reports information about the aggregate amount of these supplemental payments to the federal government. Under the proposed regulation, the state would be required to provide information on the amount of supplemental payments provided to each individual provider.

Would Require More Frequent Reauthorization of Supplemental Payments. For many of the state’s supplemental payments, the state periodically seeks reauthorization from the federal government to continue the program. For some supplemental payment programs, however, the state is not currently required to seek periodic reauthorization. Under the proposed regulation, the state would be required to seek federal reauthorization every three years for all payments.

Would Require Evaluation of Supplemental Payments. In connection with the periodic reauthorization described above, the state would be required to commit to evaluating the impacts of supplemental payments on quality and access to services. The state generally has not been required to conduct such evaluations in the past.

Allows Temporary “Grandfathering” Period

The draft regulations include a provision allowing states to continue financing structures and supplemental payments that do not comply with the regulation for a period of no more than three years after the regulations are finalized, provided that federal approval was in place before the regulations are finalized. We understand that the regulations could be finalized this summer, but this is uncertain. Notably, the state recently applied for approval of the most recent iterations of the hospital QAF and the MCO tax.

Potential Impacts in Medi‑Cal

State May Be Unable to Continue Various Financing Mechanisms Without Significant Changes. If the draft regulations were finalized in their current or similar form, many of the state’s mechanisms for financing Medi‑Cal with non‑General Fund sources would be at risk of being disallowed. For financing mechanisms that are disallowed, the Legislature would need to make a choice as to whether to replace the non‑General Fund sources with General Fund, restructure the financing mechanism (where feasible) to make it compliant with the regulations (which would likely require either the state or other entities to increase their contribution toward Medi‑Cal costs), or reduce spending in the Medi‑Cal program to account for the lost funding.

Ultimately, the draft federal regulations likely would have different impacts on different Medi‑Cal financing mechanisms. Consequently, the entire amount of funding from local funds and other state funds displayed in Figure 7 is not necessarily at risk. For some financing mechanisms, such as the MCO tax, the provisions of the state’s tax are clearly incompatible with the provisions of the draft rule and being able to continue this financing mechanism in the future is unlikely. In other cases, depending on the contents of the final rule, the state might be able to make relatively modest adjustments to come into compliance with the regulations, mitigating the fiscal impact on the state. Other items, such as the SNF QAF, appear to largely comply with provisions of the draft regulations, so any impact may be limited. At this time, we estimate that the state could face increased annual General Fund costs in the several billions of dollars if the draft regulations were finalized in their current or similar form and the state were to maintain Medi‑Cal funding at current levels.

Ultimate Impact of Proposed Regulations Highly Uncertain. The provisions of the draft regulations would have significant adverse impacts for Medicaid programs in many other states. In light of this, there is a strong possibility that some provisions of the draft regulation could be changed before the regulation is finalized. The ultimate fiscal impact of the regulations on the state will depend on what provisions are in the final rule and how the federal government elects to implement them. Additionally, as noted previously, some financing mechanisms that are ultimately found to be noncompliant with the final regulations may be grandfathered if federal approval is achieved before the rule is finalized. These factors make the ultimate impact of the proposed regulations on the state highly uncertain. However, given the potential for a significant fiscal impact on Medi‑Cal financing, we recommend that the Legislature approach proposals to significantly increase ongoing General Fund expenditures with caution.

Update on Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services

This section analyzes the Governor’s executive order issued in 2019 to transition Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy services benefit from managed care to entirely an FFS benefit. (Transitioning benefits from managed care to FFS is referred to as “carving out” a service.) Please see our previous report, The 2019‑20 Budget: Analysis of the Carve Out of Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services From Managed Care, for more background on and analysis of the pharmacy services carve out. This section also analyzes the two new prescription drug affordability proposals by the Governor that primarily impact Medi‑Cal or DHCS—(1) to consider international prices in the negotiation of drug rebates and (2) to authorize DHCS to collect rebates on drugs that are not paid for through Medi‑Cal. Our forthcoming report will analyze the Governor’s two other major prescription drug affordability proposals that have a statewide implication (that is, not Medi‑Cal/DHCS‑focused)—(1) to create a California generic drug label and (2) to establish the Golden State Drug Pricing Schedule.

Background

Brand‑Name Versus Generic Drugs

A “brand‑name” drug is a drug that is sold under a trademarked name. Brand‑name drugs are often “innovator” drugs that enjoy patent protection, which prohibits nonowners of the patent from manufacturing and selling the drug without the owner’s consent. As such, brand‑name drugs are often single‑source drugs, meaning that the patent owner has no competitors offering an identical drug for sale within the drug market. A generic drug is a non‑brand‑name drug that is made with the same chemical combination as a currently or formerly available brand‑name drug that has had its patent and exclusivity period expire (usually after roughly 15 years of coming to market). Typically, generic drugs are multiple‑source drugs where multiple manufacturers compete to produce and sell drugs made of identical chemical combinations. Because brand‑name drugs often do not face any marketplace competition, they tend to be significantly more expensive than generic drugs.

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services

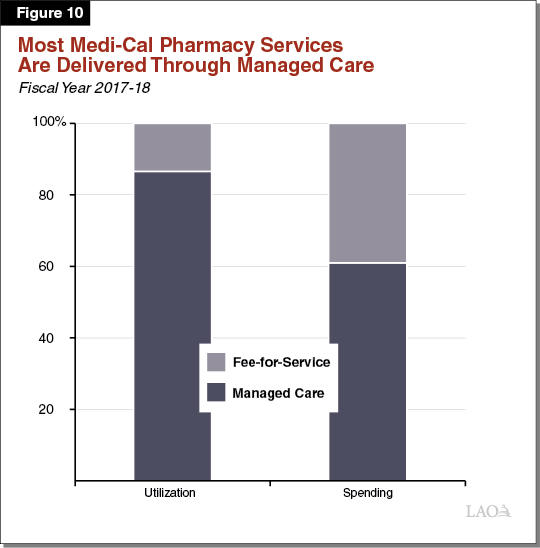

Medi‑Cal Covers Pharmacy Services, Predominantly Through Managed Care. Under its pharmacy services benefit, Medi‑Cal covers prescription drugs and other medical products obtained from pharmacies for the nearly 13 million state residents enrolled in the program. For the vast majority of Medi‑Cal recipients, Medi‑Cal pays the entire cost of covered drugs and medical products. As shown in Figure 10, most Medi‑Cal pharmacy services utilization and a majority of spending occurs through managed care. Although Medi‑Cal managed care plans currently cover and pay for most prescription drugs in Medi‑Cal, certain therapeutic classes of drugs—primarily, expensive classes of drugs, such as those for hemophilia and HIV—are carved out of managed care and instead paid for directly by the state through FFS.

DHCS Generally Only Directly Collects Supplemental Rebates in FFS. For most prescription drugs dispensed to Medi‑Cal enrollees, the state collects “federally required” rebates from drug manufacturers according to formulas prescribed under federal law. In addition, DHCS uses the Medi‑Cal program’s purchasing power to negotiate state supplemental rebates from drug manufacturers on top of the federally required rebates, but primarily only for prescription drugs paid for through FFS. Both types of rebates lower the final cost of prescription drugs. Hereafter, we refer to prescription drug costs before accounting for rebates as “gross” costs, and costs after accounting for rebates as “net” costs.

Rebates, Primarily Federally Required Rebates, Significantly Reduce Net Prescription Drug Costs in Medi‑Cal. On average, the federally required rebates lower the net cost of prescription drugs by between 30 percent and 50 percent. State supplemental rebates reduce the net cost of prescription drugs by a considerably smaller amount—around 3 percent if only counting the drugs for which the state receives supplemental rebates (those generally paid for through FFS). In addition, Medi‑Cal managed care plans also generally negotiate supplemental rebates from drug manufacturers. The savings to plans (around 4 percent) are of a similar magnitude as state supplemental rebates and are at least partially passed along to the state in the form of lower capitated payments to Medi‑Cal managed care plans.

In FFS, the State Receives Direct Savings Through the 340B Program… The federal 340B program entitles eligible health care providers (mainly hospitals and clinics that serve large numbers of low‑income patients) to discounts on outpatient prescription drugs (drugs that are not administered by a physician or within a hospital setting). These discounts result in savings that benefit participating health care providers, payers for health care such as Medi‑Cal, and other entities, such as the retail pharmacies that dispense drugs purchased through the 340B program (hereafter referred to as 340B drugs). In Medi‑Cal FFS, the state pays for 340B drugs at the purchasing hospital or clinic’s discounted cost, plus a fee to cover the cost of dispensing the drug. This means 340B discounts are passed along to the state in Medi‑Cal FFS.

…While In Managed Care, Providers Retain Earnings Through the 340B Program. In Medi‑Cal managed care, however, managed care plans pay negotiated prices for 340B drugs. This allows the health care providers participating in the 340B program to keep the difference between (1) their discounted cost and (2) the negotiated prices paid by Medi‑Cal managed care plans. Therefore, 340B savings in managed care generally accrue to hospitals, clinics, and their retail pharmacy partners rather than being passed along to the state. For more information on the interaction between the 340B program and Medi‑Cal, see our report, The 2018‑19 Budget: Analysis of the Governor’s 340B Medi‑Cal Proposal.

Governor’s January 2019 Executive Order

Carve Out Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services From Managed Care. In early January 2019, Governor Newsom released an executive order that, among other changes, directed DHCS to carve out the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services benefit from managed care and transition it entirely to FFS. Under this carve out, DHCS would more directly pay for and manage the pharmacy services utilized by Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, in contrast to paying Medi‑Cal managed care plans to do so. The administration hopes that the carve out will enable DHCS to use the full negotiating power of the Medi‑Cal program and its nearly 13 million enrollees to negotiate deeper discounts on prescription drugs than currently achieved. At the time the executive order was released, the administration did not release an estimate of the savings that would result from the carve out.

Key 2019 Developments Related to the Carve Out. The following bullets describe the two major developments that occurred related to the Medi‑Cal pharmacy services carve out following the Governor’s executive order.

- Administration Released a Savings Estimate. In May 2019, DHCS estimated that the carve out would, on net, result in ongoing General Fund savings of $393 million on an annual basis.

- Contract Awarded to a Company to Help Administer the Carved‑Out Benefit. In November 2019, DHCS announced the awarding of a contract to an administrative services organization—Magellan Medicaid Administration, Inc.—to assist the state in administering the entire Medi‑Cal pharmacy benefit through FFS. Rather than acting as a full‑service pharmacy benefit manager, Magellan primarily will assist the state by paying pharmacy claims and performing first‑line authorizations for drugs that require administrative review before being dispensed. DHCS, rather than Magellan, will (1) set the state’s preferred drug list (the drugs that will not require administrative review, also known as prior authorization), (2) negotiate discounts with drug manufacturers, (3) make final determinations related to prior authorizations, and (4) continue to perform certain other administrative responsibilities.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes several changes to facilitate the pharmacy services carve out. In addition, the Governor proposes two novel changes to state law, more loosely related to the carve out, aimed at increasing DHCS’ power to obtain deeper discounts on prescription drugs. We describe these proposed changes in this section.

Proposals and Update Related to the Carve Out

Proposes Budget‑Related Language to Facilitate Carve Out. The Governor proposes budget‑related language aimed at improving the experience for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries under the pharmacy services carve out. This language would make two statutory changes: (1) remove the current limit in FFS of six prescriptions per Medi‑Cal beneficiary and (2) eliminate the state’s authority to collect copays for prescription drugs obtained at pharmacies.

Proposes Supplemental Payment Pool for Clinics to Mitigate Loss in 340B Earnings. As a consequence of transitioning Medi‑Cal pharmacy services from managed care to FFS, participating providers (primarily hospitals and clinics) generally will no longer be able to generate earnings through the 340B program. To mitigate the loss in earnings for clinics but not hospitals or hospital‑affiliated clinics, the Governor proposes to spend $53 million General Fund ($105 million total funds) on an ongoing basis through the creation of a new supplemental payment program. For 2020‑21, the Governor proposes half‑year funding of $26 million General Fund ($53 million total funds). The administration indicated that the supplemental payments would be made to qualifying clinics based on the prescription drug utilization of their patient populations.

Budget Assumes $43 Million in Associated Net General Fund Savings in 2020‑21, and $405 Million Ongoing. The Governor’s budget revises the administration’s previous estimate of savings under the pharmacy services carve out. On an ongoing basis, the administration now estimates $405 million in net General Fund savings under the carve out (nearly $1.2 billion total funds). The administration assumes a gradual ramp up of these savings, estimating that $43 million in net General Fund savings ($126 million total funds) will materialize in 2020‑21. Given the January 1, 2021 implementation date, the 2020‑21 savings estimate reflects a half‑year of the carve out being in effect. Figure 11 summarizes the administration’s estimate of savings under the carve out.

Figure 11

DHCS Estimate of Savings Under the

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Carve Out

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

Ongoing |

|

|

Direct Pharmacy Costs |

||

|

Change in gross pharmacy spending |

‑$14 |

‑$33 |

|

Additional state supplemental rebate revenue |

‑12 |

‑292 |

|

Savings on 340B drugs |

‑31 |

‑74 |

|

Subtotals |

(‑$57) |

(‑$399) |

|

Lower administrative costs |

‑$14 |

‑$58 |

|

340B clinic supplemental payment program |

26 |

53 |

|

Grand Totals |

‑$43 |

‑$405 |

|

Note: Negative numbers denote savings; positive numbers denote costs. Totals may not add due to rounding. DHCS = Department of Health Care Services. |

||

New Proposals

Authorizes Consideration of International Best Prices in Rebate Negotiations With Drug Makers. The Governor proposes budget‑related legislation to change state law so that DHCS, when negotiating state supplemental rebates from drug manufacturers, may consider the best prices manufacturers make available to international purchasers and payers. In contrast, today, state statute authorizes DHCS to consider the best prices available to domestic purchasers and payers.

Authorizes DHCS to Collect Rebates for Drugs Not Paid for by Medi‑Cal. The Governor proposes budget‑related legislation that would authorize DHCS to collect rebates for drugs that are paid for by entities other than Medi‑Cal. The intent is to utilize the purchasing power—as well as DHCS’ established infrastructure for collecting rebates—to obtain deeper discounts on prescriptions drugs. Any rebate revenues collected on behalf of non‑Medi‑Cal beneficiaries would be used to offset General Fund expenditures in Medi‑Cal, and thereby increase the amount of General Fund available to the Legislature for any other purpose by the amount of additional rebates collected. The proposed budget‑related language would give the administration the authority to determine which non‑Medi‑Cal populations would be included in the rebate program.

LAO Assessment and Recommendations

Carve Out’s Estimated Savings Are Uncertain

DHCS’ Savings Estimate Is More Comprehensive Than Last Year’s Estimate. Last year, DHCS’ estimate of savings under the carve out did not capture a major component of savings—those related to changes in how the state would reimburse 340B drugs. DHCS’ updated estimate captures at least a significant portion, but not all, of likely savings related to 340B drugs. The estimate includes likely savings on 340B drugs provided through clinics, but, due to data limitations, excludes likely savings on 340B drugs provided through hospitals.

General Fund Savings Estimate Likely Is Overstated Due to Overly Optimistic Assumptions Related to Supplemental Rebates. While DHCS’ updated savings estimate is more comprehensive than last year’s estimate, it likely significantly overstates the savings that will be generated by the carve out. Under the carve out, DHCS assumes the state will be able to more than quintuple state supplemental rebate revenues—so that they eventually reach $292 million in General Fund annually, as shown in Figure 11—without facing significantly higher gross costs for prescription drugs. DHCS believes such savings through state supplemental rebates are achievable since the state was able to collect state supplemental rebates at these levels in the mid‑2000s, before Medi‑Cal had transitioned to a program predominantly run through managed care. We believe that collection of rebates at these levels is overly optimistic absent a significant increase in gross pharmacy services costs for the following reasons:

- Significantly Higher Generic Drug Utilization. Today, around 90 percent of drugs paid for by Medi‑Cal are generic drugs. In the mid‑2000s, around 50 percent of drugs paid for by Medi‑Cal were generics. We understand that the state collects no state supplemental rebates on generic drugs. In our view, the administration’s savings estimate does not account appropriately for the significant shift away from brand‑name drugs to generic drugs that has occurred over the last 15 years or so. Accordingly, we find that the DHCS estimate likely significantly overstates savings under the carve out.

- Higher Federally Required Rebates. For many expensive prescription drugs, the ACA in 2010 amended federal law to significantly increase the minimum level of federally required rebates that drug manufacturers must pay to Medicaid programs. Given the higher level of federally required rebates, drug manufacturers are unlikely to offer state supplemental rebates as high as they did prior to the ACA’s changes to federal law.

- Medi‑Cal Managed Care Plans Achieve 4 Percent Savings. Some, though not all, Medi‑Cal managed care plans have significant prescription drug purchasing power based on their total nationwide membership. For example, Anthem has more than 40 million members nationwide while Kaiser Health Plan has around 12 million. We understand that the large Medi‑Cal plans regularly use the full negotiating power associated with their total nationwide membership to negotiate rebates from drug manufacturers. While DHCS may be able to surpass 4 percent in state supplemental rebate savings, we seriously question whether the department could do three times as well as Medi‑Cal managed care plans currently do.

- State Supplemental Rebate Estimate Is Substantially Higher Than the Percentage Amount Collected by Any Other State Medicaid Program. We understand that the most any state collects in state supplemental rebates is 7 percent of gross pharmacy services spending. DHCS’ estimate assumes the state will collect 12 percent of gross Medi‑Cal pharmacy services spending under the carve out—a rate that is 70 percent higher than what is achieved by any other state Medicaid program. While we agree that, given Medi‑Cal’s size, the state could collect state supplemental rebates at a higher rate than any other state, a rate that is 70 percent higher than any other state appears overly optimistic.

Ultimate Savings Are Highly Uncertain But Likely Lower Than Governor Estimates… Savings under the carve out are highly uncertain due to data limitations and the challenge of predicting the outcomes of future negotiations between the state, drug manufacturers, and potentially other providers. In our assessment, and as shown in Figure 12, net General Fund savings are more likely to be around $150 million annually on an ongoing basis, or between 30 percent and 40 percent of what DHCS estimates. Assuming a similar ramp‑up schedule as DHCS has assumed, we would project related savings of around $15 million in 2020‑21, as opposed to the $43 million estimated by DHCS. Our projected savings are not precise, and the fiscal impact could differ by hundreds of millions of dollars. While we view the carve out as likely to generate net General Fund savings, there is a tangible risk that the carve out could have the opposite of the intended effect and result in net General Fund costs. This risk primarily stems from two possibilities: (1) that DHCS could pursue high state supplemental rebates without necessarily achieving lower net drug costs and (2) that the costs of administering the benefit could be significantly higher than currently assumed.

Figure 12

Comparison of DHCS and LAO Estimates of Net Savings Under the Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Services Carve Out

General Fund (In Millions)

|

DHCS |

LAO |

|

|

Direct Pharmacy Costs |

||

|

Change in gross pharmacy spending |

‑$33 |

$60 |

|

Additional state supplemental rebate revenue |

‑292 |

‑160 |

|

Savings on 340B drugs |

‑74 |

‑80 |

|

Subtotals |

(‑$399) |

(‑$180) |

|

Lower administrative costs |

‑$58 |

‑$40 |

|

340B clinic supplemental payment program |

53 |

53 |

|

Other |

— |

20 |

|

Grand Totals |

‑$405 |

‑$150 |

|

Note: Negative numbers denote savings; positive numbers denote costs. Totals may not add due to rounding. DHCS = Department of Health Care Services and LAO = Legislative Analyst’s Office. |

||

…And Without New Reporting Requirements, Any Savings Will Be Difficult to Track. The actual fiscal impact of the carve out will be difficult to track through the existing fiscal reports produced by DHCS. While DHCS’ fiscal reports will provide aggregate gross and net spending totals, they will not display how pharmacy services utilization has changed—for example, if it has gone up or if utilization of brand‑name drugs has increased relative to utilization of generic drugs. Moreover, due to changes in the complex makeup of the prescription drug market, no one fiscal measure will clearly indicate whether the state has achieved savings under the carve out.

Recommend Enacting Reporting Requirements in Order to Oversee Fiscal Impact of Pharmacy Services Carve Out. Because the fiscal impact of the carve out will be difficult to assess using existing fiscal reports by DHCS, we recommend that the Legislature establish detailed reporting requirements for DHCS. Such reports are necessary to ensure that the Legislature will know the extent to which the carve out is achieving one of its primary goals—to generate savings in Medi‑Cal. Reports should compare spending on pharmacy services prior to and after the carve out, and include at least the following elements:

- Estimates of Gross and Net Pharmacy Services Spending Per Drug Prior to and After the Carve Out. Because changes in utilization could significantly impact overall Medi‑Cal spending on pharmacy services, obtaining information on spending per drug utilized will be important.

- Average Net Cost and Utilization Estimates of Top 25 Most Expensive and Top 25 Most Utilized Drugs. Because developments in the pharmaceutical market will render pharmacy services spending per drug an imperfect estimate of the fiscal impact of the carve out, a second approach to understanding changes in pharmacy services spending would be useful for understanding the fiscal impact of the carve out. As such, the Legislature could consider requiring DHCS to report net cost and utilization estimates of the top 25 most expensive and top 25 most utilized drugs in Medi‑Cal.

- Generic Versus Brand‑Name Drug Utilization and Spending. Generics are significantly less expensive than brand‑name drugs and generally equivalent in terms of efficacy. In our view, to ensure savings under the carve out, maintaining high levels of generic drug utilization in Medi‑Cal will likely be critical. Accordingly, a key measure of the carve‑out’s fiscal performance will be the degree to which generic drug utilization levels remain high. The Legislature could go further than reporting requirements and also require DHCS to release a communication each time it includes a brand‑name drug for which there is a generic equivalent on Medi‑Cal’s preferred drug list, attesting that it has performed an analysis that shows that, on net, the brand‑name drug will be less expensive than the generic competitor.

- Changes in 340B Drug Utilization. A major component of gross savings under the carve out will result from changes to 340B reimbursement. To obtain a more comprehensive picture than the administration’s estimate of what 340B savings under the carve out may be, the report should assess changes in Medi‑Cal spending on 340B drugs for all providers that utilize the 340B program.

- Estimate of Spending on Administration of the Pharmacy Services Benefit Prior to and After the Carve Out. In our view, whether proposed funding to administer the carve out will be sufficient for ongoing implementation is somewhat uncertain. In addition, existing fiscal reports produced by DHCS will not show how much funding has been removed from managed care plans’ capitated rates specifically for administering pharmacy services. Accordingly, we recommend for DHCS to annually report (1) the additional funding needed to administer the pharmacy services carve out and (2) the annualized amount of funding removed from Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ capitated rates specifically for administration.

Carve Out Implementation Time Line Is Optimistic

Many systems changes need to be completed to ensure the smooth transition of pharmacy services from managed care to FFS. Most critically, DHCS and its new administrative services contractor must be ready to receive and pay claims to almost every pharmacy in the state, as well as perform necessary prior authorizations. Delays in DHCS’ or the administrative services contractor’s readiness—without a similar delay in the effective date of the carve out—would significantly disrupt Medi‑Cal beneficiaries’ ability to obtain their prescription drugs and other medical supplies from pharmacies. However, delaying the effective date for the carve out comes with significant challenges. For one, funding for pharmacy services is scheduled to be removed from managed care plans’ capitated rates starting in January 2021. In preparation for the date of transition, managed care plans need to have plans for the winding down of their capacity to administer the pharmacy services benefit. The extent to which Medi‑Cal managed care plans will have the functional capacity to administer pharmacy services past January 2021 should the state not be ready to implement the carve out is unclear.

Recommend Requiring DHCS to Report on Progress to Date. Given the optimistic time line of implementation of the carve out, we recommend that the Legislature use the budget process to ask DHCS and stakeholders for information to assess the extent to which implementation is on track for the January 1, 2021 effective date of the carve out.

Supplemental Payments for Clinics

How Supplemental Payments for Clinics Will Be Structured Still Somewhat Uncertain. We await more information from the administration on certain specifics of how the supplemental payments will be structured. For example, at this point, how much each supplemental payment will be and how patients’ pharmacy services utilization data will flow from pharmacies to clinics and then to DHCS is unknown.

Supplemental Payments Will Significantly Reduce Net General Fund Savings Under the Carve Out. The Governor’s proposal to mitigate clinics’ financial losses under the changes related to 340B reimbursement through the creation of a supplemental payment program will partially offset a major component of savings under the carve out. According to our estimate, this proposal reduces net General Fund savings under the carve out by around 25 percent.

In the Short Run, Backfilling Lost Funding for Clinics Might Have Merit… We understand that clinics have come to rely upon 340B earnings through Medi‑Cal managed care as a major revenue source. Accordingly, eliminating these earnings, without giving clinics some time to adjust to this loss in earnings, could disrupt clinic operations and their ability to serve their patients in the short run. For this reason, temporary supplemental payments that backfill clinics’ lost earnings might have merit.

…In the Long Run, What Public Purpose the Supplemental Payments Would Serve Is Unclear. Neither federal nor state law prescribes how clinics participating in the 340B program can spend their 340B earnings. Accordingly, while clinics likely use a portion of these earnings to improve access or quality, there is no requirement that they do so. Therefore, backfilling clinics’ lost 340B earnings does not necessarily fulfill a public purpose, such as improving access or quality. Moreover, most of the clinics that would be eligible for the 340B supplemental payments receive cost‑based reimbursement from Medi‑Cal, which generally ensures that their costs are covered. Since the reimbursement methodology for clinics already covers their costs, and generally is more generous than what other Medi‑Cal providers receive, the possibility that many clinics would close—thereby significantly hurting access in Medi‑Cal—appears unlikely. Given somewhat generous reimbursement for affected clinics and the lack of an explicit link between the supplemental payments and improvements in quality or access, the value of providing these payments in the long run is unclear.

Recommend Making Supplemental Payments Temporary or, if Made Ongoing, Tie Them to Quality and/or Access Improvements. We recommend that the Legislature only approve the Governor’s proposed supplemental payments, as currently structured, on a limited‑term basis to help clinics adjust to lower revenues. Alternatively, if the Legislature wishes to provide supplemental payments to clinics on an ongoing basis, we recommend that the Legislature specifically tie the payments to improvements in either access or quality rather than on the prescription drug utilization of clinic patients.

International Best Prices

Policy Change Unlikely to Result in Any Significant Savings. In our view, DHCS currently has the authority to open negotiations with drug manufacturers by asking for any price they wish. Authorizing DHCS to consider international prices for drugs will not change this aforementioned authority. As such, we are skeptical that the policy change will result in significant new savings in Medi‑Cal.

No Major Concerns With Adopting Proposed Statutory Change. While, in our assessment, this proposed change to state law will not result in much savings for the state, there is no significant cost to making the change. Accordingly, the Legislature could consider approving the Governor’s proposed budget‑related language.

Collection of Rebates for Drugs Not Paid for Through Medi‑Cal

Policy Change Has Merit Since It Could Significantly Increase the Negotiating Power of State Drug Purchasers. We find that expanding DHCS’ authority to collect rebates on drugs not paid for through Medi‑Cal has significant merit. We believe such a change could result in state savings on prescription drugs, while also potentially streamlining state negotiations on drug prices.

Outstanding Questions. At this time, on which populations’ behalf DHCS would negotiate non‑Medi‑Cal prescription drug rebates is unclear. However, we expect that these non‑Medi‑Cal populations could include, for example, incarcerated individuals, Department of Developmental Services consumers, and students in the California State University system. In addition, the proposed legislation does not require the administration to notify the Legislature of decisions on which populations will be included in the rebate program. Finally, there is uncertainty as to how adding populations might affect which drugs are made available to the various participating populations.

Recommend Approving in Concept. Given the potential of this proposal to generate savings and streamline negotiations on drug prices, we recommend approval of the Governor’s proposal to authorize DHCS to collect rebates on drugs not paid for through Medi‑Cal—contingent upon the administration answering certain outstanding questions during the budget process. We recommend that the Legislature ask the administration how it intends to decide on the appropriateness of adding populations to the rebate program and how the Legislature will ultimately be informed of such decisions.

Full‑Scope Expansion for Seniors Regardless of Immigration Status

Background

Prior to 2015, Undocumented Immigrants Were Eligible Only for “Restricted‑Scope” Medi‑Cal Coverage. Medi‑Cal eligibility depends on a number of individual and household characteristics, including, for example, income, age, and immigration status. Historically, income‑eligible citizens and immigrants with documented status have qualified for comprehensive, or “full‑scope,” Medi‑Cal coverage, while otherwise income‑eligible undocumented immigrants generally have not qualified for full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage. Rather, those who would be eligible for Medi‑Cal but for their immigration status were historically eligible only for restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage, which covers emergency‑ and pregnancy‑related health care services. The federal government pays for a portion of undocumented immigrants’ restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal services according to standard FMAP rules.

Today, Otherwise Eligible Young Undocumented Immigrants Are Eligible for Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage. In 2016, the state expanded full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented children from birth through age 18. Then, in the 2019‑20 budget, the state expanded full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented young adults ages 19 through 25. Today, undocumented immigrants ages zero through 25 are eligible for full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage. Undocumented adults ages 26 and over currently are only eligible for restricted‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage.

Undocumented Immigrants Continue to Represent a Significant Portion of the State’s Remaining Uninsured Population. Undocumented immigrants above age 25 do not qualify for public financial assistance to obtain comprehensive health care coverage, either through Medi‑Cal or through the state’s Health Benefit Exchange known as Covered California. As a result, they represent a significant portion of the state’s remaining uninsured. Recent estimates indicate that there are likely more than 1.5 million uninsured undocumented immigrants in the state, which represents as much as 50 percent of the state’s remaining uninsured. Figure 13 provides a brief overview of where the state stands today in terms of Medi‑Cal coverage of undocumented immigrants, including an estimate of the General Fund cost to expand full‑scope Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise eligible populations not currently covered or proposed to be covered by the Governor.

Figure 13

Ongoing Caseload and Cost of Expanding Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to Otherwise Eligible Undocumented Immigrants

|

Coverage and Age Groups |

Caseload |

General Fund Cost (In Millions)a |

|

Populations That Currently Have Full‑Scope Coverage |

||

|

Otherwise eligible children ages 0‑18 |

130,000 |

$150 |

|

Otherwise eligible adults ages 19‑25 |

105,000 |

260 |

|

Population Proposed to Gain Full‑Scope Coverage in 2020‑21 |

||

|

Otherwise eligible seniors ages 65+ |

27,000 |

250 |

|

Remaining Population Only Eligible for Restricted‑Scope Coverage |

||

|

Otherwise eligible adults ages 26‑64b |

890,000 |

2,350 |

|

All |

1,150,000 |

$3,000 |

|