LAO Contacts

- Mark Newton

- Health and Developmental Services

- Ginni Bella Navarre

- Other Human Services

October 17, 2019

The 2019‑20 Budget: California Spending Plan

Health and Human Services (HHS)

Spending Plan

Overview

Overview of Health Spending

The spending plan provides $26.4 billion General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $4.1 billion, or 18 percent, compared to the revised 2018‑19 spending level, as shown in Figure 1. This year-over-year increase is primarily due to significant growth in projected General Fund spending in Medi-Cal. To a significant degree, increased projected General Fund spending in Medi-Cal in 2019‑20 reflects a shift in costs to the General Fund from other state and federal fund sources, rather than an overall increase in program costs. Of particular note in this regard is that the 2019‑20 spending plan, in contrast to the 2018‑19 one, does not reflect a full-year net General Fund benefit from the imposition of a tax on managed care organizations (MCOs). While the Legislature reauthorized the MCO tax (which had expired at the end of 2018‑19) through the end of 2022 in budget-related legislation enacted this session, the tax will not take effect until required federal approval is given, and such approval is not certain. As such, the amount of General Fund dedicated to Medi-Cal in 2019‑20 is likely around $1 billion higher than it will ultimately be, provided the MCO tax receives federal approval and is implemented.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Spending Trends

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Medi‑Cal—local assistance |

$19,680 |

$23,104 |

$3,424 |

17% |

|

Department of State Hospitals |

1,784 |

1,824 |

40 |

2 |

|

California Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California) |

— |

429 |

429 |

—a |

|

DHCS—state administration |

248 |

273 |

25 |

10 |

|

Other DHCS programs |

295 |

309 |

14 |

5 |

|

Department of Public Health |

177 |

307 |

130 |

73 |

|

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development |

105 |

120 |

15 |

14 |

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority |

9 |

11 |

2 |

22 |

|

Health and Human Services Agency |

6 |

20 |

14 |

233 |

|

Totals |

$22,304 |

$26,397 |

$4,093 |

18% |

|

aInfinite number. DHCS = Department of Health Care Services. |

||||

In addition, and as shown in Figure 2, year-over-year growth in health program General Fund spending reflects a number of policy actions adopted by the Legislature as part of its 2019‑20 spending plan. Prominent among these is the action to appropriate $429 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20 to provide state-funded subsidies for health insurance purchased on the individual market through the state’s health benefit exchange—Covered California. (The spending plan offsets the costs of these new subsidies using increased revenues from the new state individual mandate, as discussed below.) We discuss this and other major policy actions in greater detail below.

Figure 2

Major Actions—State Health Programs

2019‑20 General Fund Effect (In Millions)

|

Program |

Amount |

|

California Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California) |

|

|

Provides state‑funded individual health insurance premium subsidies |

$428.6 |

|

Medi‑Cal—Department of Health Care Services |

|

|

Reauthorizes managed care organization tax |

—a |

|

Eliminates Proposition 56 General Fund offset |

217.7 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for housing services for Whole Person Care counties |

100.0 |

|

Expands full‑scope Medi‑Cal to undocumented adults ages 19 through 25 |

73.8 |

|

Eliminates share of cost for SPDs with incomes up to 138 percent of FPL |

31.5 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for housing services for Non‑Whole Person Care counties |

20.0 |

|

Restores certain optional Medi‑Cal benefitsb,c |

17.4 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for Medi‑Cal outreach and enrollment assistance |

15.2 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for asthma mitigation project |

15.0 |

|

Augments funding for caregiver resource centers on a one‑time basis |

10.0 |

|

Extends mental health Medi‑Cal coverage for post‑partum mothersc |

8.6 |

|

Other—Department of Health Care Services |

|

|

Provide one‑time funding for substance use counselors in emergency departments |

20.0 |

|

Provide one‑time funding for actuarial study of potential new LTSS benefit |

1.0 |

|

Realignment—Indigent Health |

|

|

Redirect realignment funding from CMSP to offset General Fund costsd |

‑45.5 |

|

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development |

|

|

Provides one‑time funding for state mental health workforce programs |

50.0 |

|

Funds the 2020‑25 Workforce Education and Training Five‑Year Plan |

35.0 |

|

Supports one‑time Song‑Brown Program grants for pediatric residency programs |

2.0 |

|

Department of Public Health |

|

|

Supports various infectious disease prevention and control effortse |

57.0 |

|

Expands the California Home Visiting and Black Infant Health Programs |

30.5 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to improve health outcomes among LBQ women |

17.5 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for substance use disorder response navigators |

15.2 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to support sickle cell disease treatment infrastructure |

15.0 |

|

Supports Alzheimer’s research, infrastructure, and Governor’s Task Forcef |

8.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to support efforts to reduce mental health disparities |

8.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to support Kern Medical Center’s Valley Fever Institute |

2.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to support the International AIDS conference |

2.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding to support a study of farmworkers’ health |

1.5 |

|

Increases funding for the Safe Cosmetics Program |

1.5 |

|

Department of State Hospitals |

|

|

Implements new staffing standards |

23.0 |

|

Expands IST patient treatment capacity |

22.0 |

|

Provides funding for deferred maintenance |

15.0 |

|

Provides funding for patient‑related operating expenses |

10.5 |

|

Maintains expanded capacity of hospital police academy |

5.8 |

|

Expands capacity for patients nearing release |

5.7 |

|

Moves department headquarters |

4.9 |

|

Health and Human Services Agency |

|

|

Provides one‑time funding for Healthy California for All Commissiong |

5.0 |

|

Adds leadership positions, including Surgeon General, and supports reorganization |

3.2 |

|

aBecause implementation of the managed care organization tax is contingent upon pending federal approval (which is not certain), its revenues are not yet available for allocation. Provided the state receives federal approval, we expect revenues from the tax to reduce General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal by around $1 billion in 2019‑20. bIncludes audiology, incontinence creams and washes, optical, podiatry, and speech therapy. cSubject to potential suspension on December 31, 2021. dRealignment funding is redirected to pay for a higher county share of the cost of CalWORKs grants resulting in General Fund savings of an equal amount. eIncludes $40 million in one‑time funding available over four years; $15 million subject to potential suspension on December 31, 2021. fThe $5 million for Alzheimer’s infrastructure is one‑time. gFunding is reappropriated from 2018‑19 budget. The commission is charged with providing analysis of how to transition to a single‑payer health care delivery system. SPDs = seniors and persons with disabilities; FPL = federal poverty level; LTSS = long‑term services and support; CMSP = County Medical Services Program; LBQ = lesbian, bisexual, and queer; AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; and IST = incompetent to stand trial. |

|

Overview of Human Services Spending

The 2019‑20 spending plan provides nearly $15.5 billion from the General Fund for human services programs. This is an increase of $1.7 billion, or 12.6 percent, compared to the revised prior-year spending level, as shown in Figure 3. This is primarily the result of higher spending in the Department of Developmental Services and the In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, largely reflecting policy changes and increasing caseloads, costs per consumer, and labor costs in these two program areas. Figure 4 shows the major human services policy changes adopted by the Legislature as part of the 2019‑20 spending plan. These changes are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 3

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Spending Trends

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Change From 2018‑19 to 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Department of Developmental Services |

$4,498.5 |

$5,040.0 |

$541.9 |

12.0% |

|

In‑Home Supportive Services |

3,777.3 |

4,493.4 |

716.1 |

19.0 |

|

SSI/SSP |

2,759.7 |

2,733.0 |

‑26.7 |

‑1.0 |

|

County Administration/Automation |

811.8 |

826.1 |

14.3 |

1.8 |

|

Child welfare services |

605.8 |

653.1 |

47.3 |

7.8 |

|

CalWORKs |

300.4 |

564.8 |

190.2 |

88.0 |

|

Department of Child Support Services |

320.0 |

339.3 |

19.3 |

6.0 |

|

Department of Rehabilitation |

66.3 |

73.0 |

6.7 |

10.1 |

|

Department of Aging |

37.1 |

84.0 |

46.9 |

126.4 |

|

All other social services (including state support) |

496.9 |

668.2 |

171.2 |

34.5 |

|

Totals |

$13,748.0 |

$15,475.3 |

$1,727.2 |

12.6% |

Figure 4

Major Actions—Human Services Programs

2019‑20 General Fund Effect (In Millions)

|

Program |

Amount |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

|

|

Makes a deposit in the Safety Net Reserve |

$700.0a |

|

CalWORKs |

|

|

Increases monthly cash grant amounts |

331.5b |

|

Expands eligibility and increases funding for CalWORKs Home Visiting Program |

89.6 |

|

Eliminates consecutive day rule for Homeless Assistance Program |

14.7c |

|

Increases earned income disregard |

6.8c |

|

Increases asset limits |

7.5c |

|

In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) |

|

|

Provides funding to restore IHSS service hours previously reduced by 7 percent |

357.6 |

|

Shifts 2019‑20 IHSS MOE costs from counties to the state |

296.7 |

|

SSI/SSP |

|

|

Provides ongoing funding to increase Cash Assistance Program for Immigrants grants by $10 to equal SSI/SSP grant levels |

1.8 |

|

Provides ongoing funding for the Housing and Disability Assistance Program |

25.0 |

|

Child Welfare Services |

|

|

Provides funding for placement prior to approval |

39.1 |

|

Provides one‑time foster parent recruitment and retention funding |

21.6 |

|

Establishes the Family Urgent Response System |

15.0d |

|

Funds a one‑time augmentation to assist with Resource Family Approval process |

14.4 |

|

Creates a public health pilot project in Los Angeles County |

8.3e |

|

Provides a one‑time cost‑of‑living adjustment to Foster Family Agencies |

6.5e |

|

Food Assistance |

|

|

Provides funding for state‑funded food benefit programs for households negatively affected by the elimination of SSI Cash‑Out policy |

88.0 |

|

Increases funding for senior nutrition program |

17.5 |

|

Other Department of Social Services |

|

|

Funds development activities and state operations for the CalSAWS |

31.3 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for the youth civic engagement initiative |

12.0 |

|

Funds the Immigrant Justice Fellowship Program |

4.7 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for Elk Grove Food Bank relocation |

4.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for Adult Protective Services and Public Administrator/Guardian/Conservator training |

3.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for the Inland Congregations United for Change |

2.0 |

|

Provides funding for Special Olympics |

2.0 |

|

California Senior Legislature |

|

|

Provides ongoing funding for the California Senior Legislature |

0.3 |

|

Department of Child Support Services |

|

|

Provides funding for administrative costs of Local Child Support Agencies |

19.1 |

|

Department of Aging |

|

|

Provides temporary funding to increase Multipurpose Senior Services Program rate |

14.8 |

|

Provides ongoing funding for the Long‑Term Care Ombudsman Program |

4.2 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for Dignity at Home and Fall Prevention Program |

5.0 |

|

Provides ongoing funding to expand “No Wrong Door” model within the Aging and Disability Resources Centers |

5.0 |

|

Developmental Services |

|

|

Increases provider rates across most service categories by up to 8.2 percent |

124.5d |

|

Suspends policy requiring a uniform holiday schedule |

30.1f |

|

Expands safety net and crisis services |

25.8 |

|

Provides funding to restructure and reorganize DDS headquarters |

6.5g |

|

Funds implementation of rate increases and increases oversight and accountability of regional centers |

5.0 |

|

Provides funding for initial DDS headquarters relocation activities |

3.4h |

|

Provides planning funds for development of new federal reimbursement IT system |

3.0 |

|

Provides funding for the Best Buddies program |

2.0 |

|

Provides one‑time funding for on‑site assessments of service providers to comply with new federal rules |

1.8 |

|

Supports development of MOUs with counties about trauma informed systems of care for foster youth |

1.2i |

|

Expands regional center oversight of family home agencies |

1.1 |

|

Covers insurance co‑payments for families with infants or toddlers in the Early Start program |

1.0 |

|

Rehabilitation |

|

|

Increases community rehabilitation provider rates |

3.4 |

|

Makes IT improvements |

1.6 |

|

Funds Traumatic Brain Injury program with General Fund |

1.2 |

|

Increases supported employment provider rates (commensurate to DDS rate increases) |

0.5d |

|

aReserve now has a balance of $900 million which is available for either CalWORKs or Medi‑Cal. This funding is in a reserve and therefore not reflected in the 2019‑20 budget for CalWORKs. bReflects partial‑year costs, as increases take effect in October 2019. cAmount reflects partial‑year costs (policy changes scheduled to take effect in June 2020). These policies are only to be enacted after conforming changes are made to CalSAWS. dAmount reflects half‑year costs (rates take effect in January 2020). Increases are subject to possible suspension on December 31, 2021. eIncrease subject to possible suspension on December 31, 2021. fUniform holiday schedule subject to possible reinstatement after December 31, 2021. gAmount decreases to $6.2 million beginning in 2022‑23 after limited‑term positions end. hAmount declines in future years as the move is completed. iAmount decreases to $134,000 beginning in 2021‑22 after limited‑term positions end. |

|

|

MOE = maintenance‑of‑effort; CalSAWS = California Statewide Automated Welfare System; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; IT = information technology; and MOU = memorandum of understanding. |

|

HHS Crosscutting Issues

Provisionally Suspends Various HHS Augmentations on December 31, 2021

The Governor’s May 2019, multiyear budget projections showed a General Fund operating deficit arising before the end of 2022‑23. As a preventive measure, the spending plan adopted provisional suspension language that applies to 17 pre-selected HHS augmentations (as well as three augmentations in other policy areas) included in the 2019‑20 Budget Act. Specifically, in May 2021, the Department of Finance (DOF) will calculate whether General Fund revenues exceed General Fund expenditures—without the 17 HHS-related and three non-HHS-related suspensions—in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. If DOF determines revenues will exceed expenditures, then the programs’ ongoing expenses will continue. Otherwise, the expenditures are automatically suspended. We project that the HHS-related suspensions, if activated, would result in General Fund savings of up to $800 million in 2021‑22 (due to being implemented at the half-year mark) and around $1.7 billion in 2022‑23 and beyond. Figure 5 lists the 17 HHS augmentations subject to the suspension language.

Figure 5

HHS Programs or Augmentations Subject to Potential Suspension

(In Thousands)

|

Program or Augmentation |

Department |

Amounta |

|

Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal provider payment increases |

DHCS |

$861,004 |

|

IHSS 7 percent service‑hour restoration |

DSS |

357,582 |

|

DDS service provider rate increases (including DOR‑related increases) |

DDS |

250,000 |

|

Medi‑Cal optional benefits restoration |

DHCS |

40,500 |

|

Uniform holiday schedule current suspension allowing for extra billing days |

DDS |

30,100 |

|

Family Urgent Response Team |

DSS |

30,000 |

|

Senior nutrition |

CDA |

17,500 |

|

Foster care transitional housing |

DHCDb |

13,000 |

|

Emergency Child Care Bridge Program |

DSS |

10,000 |

|

Extension of Medi‑Cal coverage for post‑partum mental health |

DHCS |

8,600 |

|

Child welfare public health nursing early intervention |

DSS |

8,250 |

|

Foster Family Agency rate increase |

DSS |

6,500 |

|

Aging and Disability Resource Center/No Wrong Door Model |

CDA |

5,000 |

|

STD prevention and control |

DPH |

5,000 |

|

HIV prevention and control |

DPH |

5,000 |

|

Hepatitis C virus prevention and control |

DPH |

5,000 |

|

Expansion of screening and intervention in Medi‑Cal to drugs other than alcohol |

DHCS |

2,600 |

|

Total |

$1,655,636 |

|

|

aAmounts reflect the full‑year, projected General Fund cost of the augmentations or programs subject to the suspension language. Accordingly, the amounts reflect the General Fund savings during the first full year following the suspensions being activated. bWorking in conjunction with county child welfare agencies. HHS = Health and Human Services; DHCS = Department of Health Care Services; IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services; DSS = Department of Social Services; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; DOR = Department of Rehabilitation; CDA = California Department of Aging; DHCD = Department of Housing and Community Development; STD = Sexually Transmitted Disease; and DPH = Department of Public Health. |

||

Changes to 1991 Realignment

In 1991, the Legislature shifted significant fiscal and programmatic responsibility for many HHS programs from the state to counties. This shift is referred to as 1991 realignment. The spending plan reflects several changes to 1991 realignment, as described below. For more information on 1991 realignment and related proposals that were considered through the 2019‑20 budget process, see our previous reports: The 2019‑20 Budget: Assessing the Governor’s 1991 Realignment Proposals and The 2019‑20 May Revision: Update to the Governor’s 1991 Realignment Proposals.

Makes Various Changes to IHSS County Maintenance-of-Effort (MOE). As a part of the 2017‑18 budget, the state implemented a new IHSS county MOE financing structure. At the time, realignment revenues alone were not enough cover counties’ share of IHSS costs. Moreover, in January 2019, DOF released a report finding that 1991 realignment could no longer support counties’ IHSS MOE costs over time. To address this problem, the 2019‑20 budget includes a number of modifications to the IHSS county MOE, including rebasing the IHSS county MOE costs to a lower amount in 2019‑20 and lowering the annual adjustment factor. Overall, the changes made to the IHSS county MOE result in about $300 million of what otherwise would have been county costs shifting to the state in 2019‑20. For more detailed information on the 2019‑20 changes made to the IHSS county MOE financing structure, see the “In-Home Supportive Services” section of this post.

Increases Growth Funding for Local Health and Mental Health Programs. As part of the 2017‑18 budget package, the state redirected growth in 1991 realignment revenues that otherwise would have been allocated to local health and mental health programs to instead cover county IHSS costs. The 2019‑20 budget package discontinues this redirection, thus increasing the amount of growth funding allocated to local health and mental health programs. In 2019‑20, this change is estimated to result in an additional $128 million in realignment funding for these programs.

Suspends Revenues to County Medical Services Program (CMSP) Until Reserves Are Reduced. Providing health care services to the low-income uninsured population, such services sometimes referred to as “indigent health services,” is a major component of local health programs funded through realignment. Some counties administer indigent health services themselves. However, in 35 mostly rural counties, indigent health services are administered by CMSP. Since the state expanded eligibility for Medi-Cal in 2014, the number of individuals served by CMSP has dropped significantly. As CMSP has continued to receive funding through realignment, its reserves have grown to more than ten times its annual operating budget. Legislation adopted with the 2019‑20 budget package redirects all realignment funding from CMSP until its reserves are spent down to a level that would support no more than two years of operations. Redirected realignment funding—an estimated $45 million in 2019‑20—will instead be used to pay for an increased county share of cost in California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) grants, reducing state General Fund costs for CalWORKs grants by an equal amount.

Aging-Related Actions

Administration Initiates Master Plan on Aging Process. In recent years, the Legislature has called for the state to develop a plan for issues related to the growing aging population, including how best to structure state programs to meet the needs of the increasing number of seniors and assess the long-term impact of demographic changes on the state budget. In June 2019, the Governor signed an executive order establishing a formal process for the creation of a Master Plan for Aging. The Master Plan, in part, will address the sustainability of state long-term care programs and how to better coordinate programs that serve seniors, their families, and caregivers. Specifically, two reports are expected to be produced as a part of the Master Plan for Aging process. The first report, which is due to the Governor by March 2020, will include (1) information on the growth and sustainability of state long-term care programs and infrastructure, including IHSS; (2) an examination of financing, quality, and access to long-term care services; (3) an examination of potential workforce issues; and (4) recommendations to stabilize long-term care services as a foundation for implementing the Master Plan. The second report is scheduled to be released by October 1, 2020 and will include broader strategies on how the state government, local governments, the private sector, and philanthropy can promote healthy aging and prepare for the coming demographic shift.

Aging-Related Budget Actions. The 2019‑20 budget includes various near-term actions to strengthen and expand services to the aging population, which we list below.

- Eliminates Share of Cost for Aged and Disabled Medi-Cal Population up to 138 Percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The budget includes $31.5 million from the General Fund ($63 million total funds) to increase the income level up to which seniors and persons with disabilities may qualify for Medi-Cal benefits without having to pay a share of cost from 122 percent of FPL to 138 percent of FPL. We describe this change in greater detail in the “Medi-Cal” section of this post.

- Augments Funding for the Senior Nutrition Program. The budget includes a $17.5 million augmentation to the Senior Nutrition Program overseen by the Department of Aging. With the additional funding, it is estimated that the program will be able to provide 1.26 million more meals per year (an increase of roughly 7 percent) and serve about 12,000 new recipients (an increase of roughly 5 percent). As described more fully in the “Provisionally Suspends Various HHS Augmentations on December 31, 2021” section of this post, this augmentation is subject to possible suspension on December 31, 2021 depending on whether General Fund revenues will exceed General Fund expenditures in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23.

- Provides a Provider Rate Increase for the Multipurpose Senior Services Program. The budget provides $14.8 million one-time General Fund to be spent over three years to increase the Multipurpose Seniors Services Program provider rate by 25 percent.

- Provides Additional Funding for the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program. The budget increases funding for the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program by $5.2 million—from about $10 million in 2018‑19 to about $15 million in 2019‑20—to conduct quarterly visits of skilled nursing facilities and residential care facilities for the elderly. The additional funding consists of $4.2 million from the General Fund and $1 million (one time) from the State Health Facilities Citation Penalties Account. By 2020‑21, the additional General Fund provided to the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program will increase from $4.2 million to $5.2 million. (The program could continue to receive funding from the State Health Facilities Citation Penalties Account in 2020‑21 depending on whether the balance of the account exceeds $6 million at the 2020 May Revision.)

- Provides One-Time Funding for Dignity at Home and Fall Prevention Program. The spending plan includes $5 million one-time General Fund to support the Dignity at Home and Fall Prevention Program, which will provide grants to local area agencies on aging (AAAs) for injury prevention information, education, and services.

- Provides Funding to Strengthen “No Wrong Door” Model Through Aging and Disability Resources Centers. The budget provides $5 million ongoing General Fund to support the Aging and Disability Resources Centers (ADRCs). ADRCs were established in the early 2000s as a “No Wrong Door” program to assist older individuals, caregivers, and individuals with disabilities with accessing long-term services and supports at the local level. The state funds will be allocated by the Department of Aging to qualifying AAAs and Independent Living Centers interested in establishing a new ADRC to assist them in their application process. Additionally, funds can be provided to the existing eight ADRCs to expand or strengthen services.

- Increases Funding for Caregiver Resource Centers. In recent years, the state has provided $4.9 million annually from the General Fund to partially support the operations of 11 caregiver resource centers located throughout the state. These centers provide services and supports to families and other caregivers of persons with physical and cognitive impairments. In addition to continuing the annual funding amount of $4.9 million, the budget provides an additional $10 million annually from the General Fund for 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22, to expand service delivery and improve information technology systems used by the centers.

- Provides One-Time Funds for Adult Protective Services (APS) and Public Administrator/Guardian/Conservator (PA/PG/PC) Training. The 2016‑17 budget provided $3 million in one-time funding to develop training infrastructure for APS social workers. This funding expired at the end of 2018‑19. The spending plan includes $5.8 million one-time General Fund, available over three years, to (1) continue and expand APS training, and (2) develop a statewide infrastructure for PA/PG/PC training.

- Requires Feasibility Study for Potential Future Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) Benefit Program. The budget includes $1 million from the General Fund for the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to contract for a feasibility study that would evaluate the concept of a new state-funded LTSS benefit program. The budget action did not specify the features of the program that would be evaluated, but it could involve a cash benefit provided to individuals in need of LTSS due to age or disability, funded through those individuals’ prior contributions, such as through a payroll tax. The feasibility study will provide cost estimates for different options for services and financing and will evaluate possible impacts on existing state LTSS programs. The study is due to be provided to the Legislature no later than July 1, 2020.

- Provides Ongoing General Fund Support for the California Senior Legislature (CSL). Historically, CSL’s operating costs were covered by donations made through the voluntary contribution tax check-off program. However, in recent years the Legislature has provided CSL with one-time General Fund due to donations not being enough to fully cover costs. Rather than providing temporary funding, the budget provides $300,000 ongoing General Fund to primarily cover CSL staffing and office equipment expenses.

Housing-Related Actions

Provides Funding for Whole Person Care Pilot Housing Services. The spending plan includes $100 million from the General Fund on a one-time basis to provide funding for supportive housing services in counties that participate in the Medi-Cal Whole Person Care (WPC) pilot. We describe this funding in greater detail in the “Behavioral Health Augmentations” section of this post.

Provides Funding to Continue the Bringing Families Home Program. The 2019‑20 budget provides $25 million on a one-time basis to continue and expand the Bringing Families Home program for child welfare-involved families who are homeless or at risk of being homeless.

Provides Ongoing Funding to Housing and Disability Advocacy Program. The spending plan provides $25 million ongoing General Fund to permanently establish the Housing and Disability Assistance Program (HDAP). The 2017‑18 Budget Act initially included one-time funding of $45 million General Fund, available over three years, to establish HDAP. (The budget reappropriates the remaining balance of funding provided in 2017‑18.) Initially, HDAP was established as a temporary county match program to assist homeless, disabled individuals with applying for disability benefit programs, including the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP), while also providing housing supports. As a part of the 2019‑20 budget package, HDAP will continue to include outreach, case management, benefits advocacy, and housing supports to all program participants. Additionally, participating counties are still required to match any state funds on a dollar for dollar basis.

Allows for More Flexible Use of the Homeless Assistance Program (HAP). The 2019‑20 spending plan includes $14.7 million General Fund ($27.6 million General Fund annually thereafter) to remove the rule that the HAP be used for up to 16 consecutive days in a 12-month period. Instead, the program can be used for up to 16 cumulative days in a year.

Funds Transitional Housing Programs for Foster Youth. The 2019‑20 budget includes $13 million General Fund ($8 million General Fund annually thereafter) to the Department of Housing and Community Development to be available to counties to increase their transitional housing programs for foster youth. This augmentation is subject to the suspension described earlier.

Secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHSA)

The Secretary of CHHSA provides direction and leadership to 12 departments—including the two largest, DHCS and the Department of Social Services—and five different offices, including the Office of Systems Integration. The spending plan provides $533.5 million from all fund sources for the Secretary in 2019‑20, up $50.1 million relative to the revised estimate for 2018‑19. The General Fund accounts for $19.9 million of total funds in 2019‑20, up $14.2 million (or 246 percent) from 2018‑19. Most of the new funding ($12.2 million), however, is one time in nature, including $7.2 million to support collaborative efforts addressing early childhood issues (see the “Early Education” section of the Education spending plan post) and $5 million for the Healthy California for All Commission (see the “Increasing Health Care Coverage and Affordability” section later in this post).

Establishment of the Office of the Surgeon General, New Deputy Secretaries of Early Childhood Initiatives and Behavioral Health. The spending plan provides $2.6 million General Fund in 2019‑20 (and $2.5 million in 2020‑21 and ongoing) for the following new leadership positions at the Secretary of CHHSA.

- Surgeon General. In January, Governor Newsom issued an executive order establishing the Office of the Surgeon General and subsequently appointed California’s first Surgeon General. The Surgeon General will advise the Governor on comprehensive health approaches, particularly approaches that address adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress, and serve as a spokesperson on public health issues throughout the state. The spending plan provides funding to establish the office and for six positions, including the Surgeon General position.

- Deputy Secretary for Early Childhood Initiatives. The Governor created a new CHHSA position, the Deputy Secretary for Early Childhood Initiatives. This position, appointed by the Governor, will advise the Governor on early childhood initiatives and lead implementation of efforts in this area.

- Deputy Secretary for Behavioral Health. The Governor created another new CHHSA position, the Deputy Secretary for Behavioral Health. This position, also appointed by the Governor, will collaborate with departments on the WPC Pilot and serve in a leadership role on other mental health and substance use disorder issues.

- Assistant Secretary of Policy Development. As part of the reorganization of the Office of the Secretary of CHHSA discussed below, the spending plan provides funding for a new assistant secretary of policy development who will focus on health care costs and coverage and on the office’s work with the Healthy California for All Commission.

Reorganization of the Office of the Secretary. The spending plan provides $640,000 General Fund in 2019‑20 (and $603,000 annually thereafter) to reorganize the Office of the Secretary of CHHSA. Currently, the office has five assistant secretaries (each of whom oversees several CHHSA departments and offices) who report to a single deputy secretary. The reorganization will instead have two deputy secretaries (one for health services and one for human services), six assistant secretaries, and two new associate government program analysts focused on budget development. There will also be a new Office of Enterprise Data Analytics and a new Southern California Office of the Secretary. According to the administration’s plan, the reorganization will allow the Office of the Secretary to focus on several priorities: improving access to health insurance and health care for all Californians; better integrating health and human services systems using a person-centered approach to service delivery; and improving the lives of vulnerable populations, such as homeless Californians and foster youth. Under the reorganization, there will be increased use of data and analytics to inform decision-making.

California Statewide Automated Welfare System (CalSAWS)

State Required by Federal Government to Transition From Three Automated Welfare Systems to One Statewide System. A number of major HHS programs, such as CalFresh and CalWORKs, are locally administered by the state’s 58 counties. To determine eligibility for these programs and perform other administrative functions, counties use one of three automated welfare systems. Recently, federal agencies mandated that the state migrate all counties to a single statewide automated system by the end of 2023 in order to maintain federal funding for a portion of the systems’ maintenance and operations costs.

Development of a Single Statewide System Underway. In early 2019, state HHS departments (and the Office of Systems Integration [in the Office of the Secretary]) started development of a single statewide system—CalSAWS. The Legislature approved $156 million total funds ($31 million General Fund) in the 2019 Budget Act to support state operations and system development activities. The Legislature also codified additional legislative reporting and goals for the system.

Health Issues

Increasing Health Care Coverage and Affordability

The budget package includes several actions related to expanding health care coverage and making it more affordable, described below.

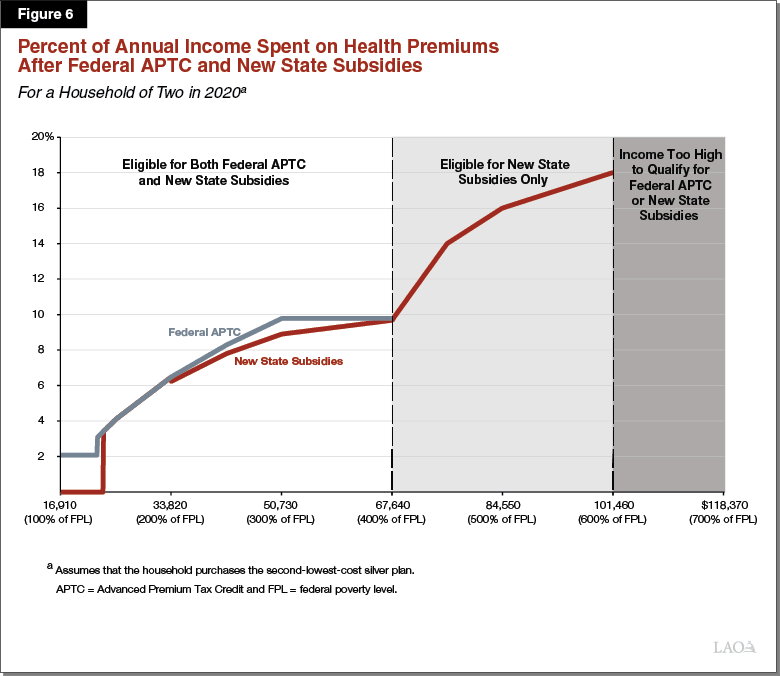

Funds Individual Market Insurance Subsidies. California residents who do not receive health care coverage through their employers or from government programs can purchase individual coverage through a centralized health insurance marketplace known as Covered California. The federal government provides subsidies to most people that purchase coverage through Covered California. The spending plan provides new state subsidies to further reduce the cost of coverage purchased through Covered California for households with incomes up to 600 percent of FPL, at a cost of $429 million (General Fund) in 2019‑20. The state subsidies will be modeled after the federal Advanced Premium Tax Credit (APTC) and will limit a household’s out-of-pocket premium costs to a percentage of its income. Figure 6 displays the structure of the new state subsidies relative to the federal APTC. For households with incomes less than 400 percent of FPL, the new state subsidies will build on the federal APTC by further lowering the percentage of income households are required to spend on premiums. Households with income between 400 percent and 600 percent of FPL do not qualify for the federal APTC but will qualify for the new state subsidies. The subsidies will be available beginning in January 2020 and continue for three years—through the end of calendar year 2022—after which they will be repealed.

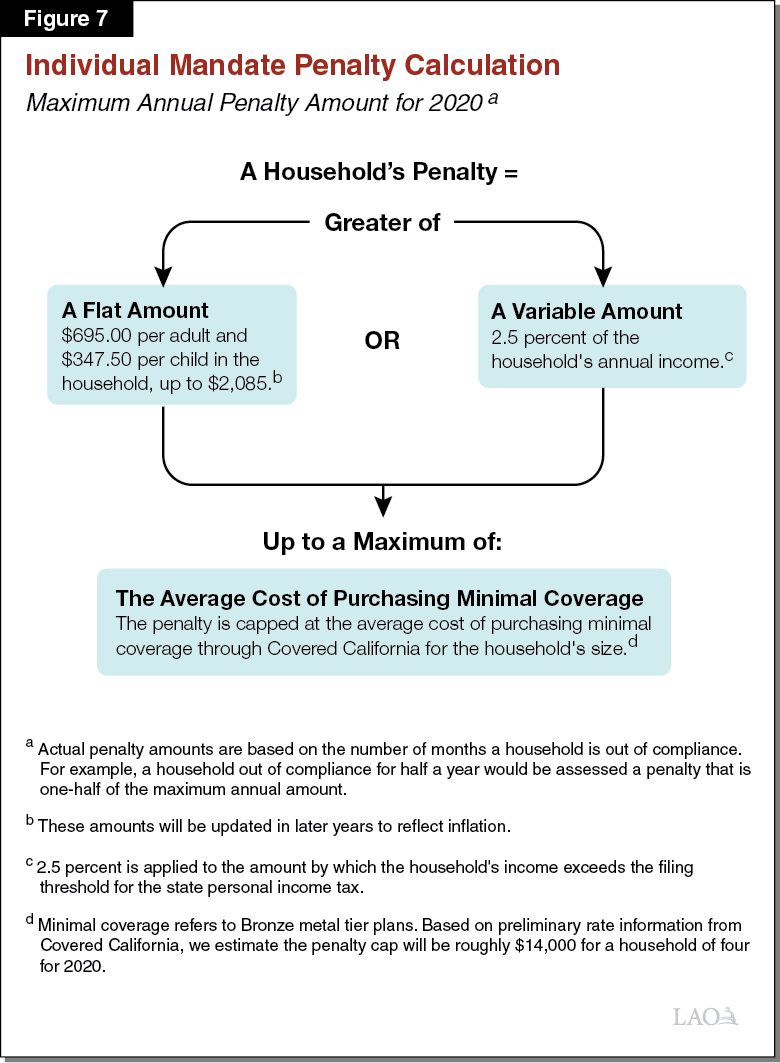

Establishes State Individual Mandate and Penalty. The federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act put in place a requirement, known as the “individual mandate,” that most individuals obtain health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. Congress later took action to set the amount of the penalty to zero, effectively eliminating it. Budget legislation puts in place a state individual mandate with an associated penalty, beginning in 2020. The new state individual mandate and penalty are modeled on the federal individual mandate and penalty before it was set to zero. Figure 7 lays out how the amount of the new state penalty will be calculated. As an example, a family of two adults and two children with annual income of $77,000 (roughly 300 percent of FPL) that is out of compliance with the individual mandate for all of 2020 would be subject to a penalty of $2,085. This penalty would be assessed on the family’s state income tax return, filed in early 2021.

The state individual mandate is expected to result in several hundred thousand additional individuals taking up health coverage that otherwise would not. The state individual mandate’s penalty will also generate General Fund revenues—an estimated $317 million beginning in 2020‑21—paid by those that do not comply with the mandate. These revenues will partially offset the cost of the new state subsidies described earlier. In contrast to the new state subsidies that sunset after 2022, the individual mandate and related annual penalty revenues are ongoing.

Expands Full-Scope Medi-Cal to Undocumented Adults Ages 19 Through 25. The spending plan expands full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to otherwise eligible undocumented adults ages 19 through 25. Currently, all undocumented adults are eligible for restricted-scope Medi-Cal that covers emergency- and pregnancy-related services. In 2019‑20, $75 million General Fund ($98 million total funds) is projected to be needed to cover the expansion, which is expected to be implemented later in the fiscal year due to systems changes that must be completed beforehand. On an ongoing basis, we project the expansion will increase General Fund spending by around $225 million annually across Medi-Cal and IHSS. About 100,000 young undocumented adults are expected to gain full-scope coverage under this expansion.

Eliminates Share of Cost for Aged and Disabled Medi-Cal Population up to 138 Percent of FPL. Children and nonelderly adults are generally eligible for free coverage through Medi-Cal if they have income less than 138 percent of FPL. In contrast, for individuals over age 65 and some others that qualify for Medi-Cal because of a disability, the income threshold for free coverage is lower—roughly 122 percent of FPL in 2019. Seniors and persons with disabilities subject to this threshold may still receive Medi-Cal coverage if their income exceeds the threshold, but generally must pay a share of their medical costs out of pocket first. The budget includes $31.5 million from the General Fund ($63 million total funds) to increase the income-eligibility threshold for Medi-Cal coverage without a share of cost to 138 percent of FPL for seniors and persons with disabilities. This amount of funding assumes a half-year of implementation in 2019‑20.

Extends Medi-Cal Coverage for Post-Partum Mothers With Mental Health Disorders. Currently, women with incomes between 138 percent and 322 percent of FPL may qualify for Medi-Cal coverage of pregnancy and post-partum services—including services to treat mental health conditions—while they are pregnant and for 60 days after the end of a pregnancy. Budget legislation extends the 60-day period of post-partum eligibility to one year for women who have been diagnosed with specified maternal mental health conditions. The budget provides $8.6 million from the General Fund to reflect this change. However, the administration believes that this change cannot be implemented this fiscal year and plans to implement the change during fiscal year 2020‑21.

Provides Funding for Medi-Cal Enrollment Assistance. The budget provides $15.2 million from the General Fund in 2019‑20, with intent for an additional $15 million to be provided in 2020‑21, for Medi-Cal enrollment assistance. These funds will be matched with an equal amount of federal funding. Funds will be distributed to counties, which in turn will contract with community-based organizations to conduct outreach and assist individuals who are eligible for Medi-Cal but are not enrolled to enroll and use their benefits.

Reconfigures the Council on Health Care Delivery Systems Into the Healthy California for All Commission. The 2018‑19 Budget Act established the Council on Health Care Delivery Systems, composed of appointees from the Governor and Legislature. The Council was tasked with studying health care delivery system reforms that could expand coverage, reduce costs, and streamline health care financing. The 2019‑20 spending plan reconfigures the Council into the Healthy California for All Commission, whose mission is specifically to develop a plan for transitioning to a single-payer health care financing system. Additional changes include an expansion in the number of members from 5 to 13 and expediting the Commission’s work so that its final required report—providing options for transitioning to single-payer—is due on or before February 1, 2021. Finally, the 2019‑20 spending plan reappropriates the unspent $5 million in General Fund provided to the Council in 2018‑19 to the Commission and makes the funding available for expenditure through 2020‑21.

Reauthorizes the MCO Tax

Reauthorized MCO Tax Is Structured Similarly to the Recently Expired Tax. For the years 2016‑17 through 2018‑19, the state imposed a tax on MCOs that generated a net General Fund benefit of over $1 billion annually. The spending plan reauthorizes the MCO tax under a broadly similar structure as the previous tax, with certain key distinguishing features. As with the previous MCO tax, the reauthorized tax is a per-member, per-month tax on the Medi-Cal and commercial enrollment of MCOs. Additionally, as shown in Figure 8, the reauthorized MCO tax features a tiered-rate structure whereby the tax rate varies based on Medi-Cal versus commercial enrollment and by the number of enrollees an MCO has. Because the MCO tax is a health care-related tax imposed on Medicaid services, it must be approved by the federal government.

Figure 8

Comparing the Tax Rates of the Previous and Reauthorized MCO Taxes

|

Member Monthsa |

Tax Rate Per Member Month |

|

|

Previous Tax: |

Reauthorized Tax: |

|

|

Medi‑Cal Enrollees |

||

|

1‑2,000,000 |

$45.0 |

$40.0 |

|

2,000,001‑4,000,000 |

21.0 |

40.0 |

|

4,000,001 and above |

1.0 |

— |

|

Commercial Enrollees |

||

|

1‑4,000,000 |

8.5 |

— |

|

4,000,001‑8,000,000 |

3.5 |

1.0 |

|

8,000,001 and above |

1.0 |

— |

|

AHCSP Commercial Enrolleesb |

||

|

1‑8,000,000 |

2.5 |

—c |

|

aA member month is defined as one member being enrolled for one month in a MCO. bAn AHCSP is defined as a nonprofit health plan that has high statewide enrollment, owns or operates pharmacies, and exclusively contracts with a single medical group in all of its geographic areas of operation. cThe reauthorized MCO tax does not have a unique tax tier for AHCSP commercial enrollees. Instead, these would be taxed according to the rates in the tiers for commercial enrollees. MCO = managed care organization and AHCSP = alternate health care service plan. |

||

Reauthorized MCO Tax Will Generate at Least a $1.7 Billion Net General Fund Benefit Annually for Three and a Half Years. The spending plan reauthorizes the MCO tax for a period of three and a half years, from 2019‑20 to halfway through 2022‑23. The tax rates in certain tiers are scheduled to increase each year, with the $40 tier(s) for Medi-Cal enrollees growing to $55 and the $1 tier for commercial enrollees growing to $1.50, each by 2022‑23. In contrast to the previous MCO tax package, the reauthorized MCO tax does not include any offsetting tax reductions for MCOs and their corporate affiliates. As shown in Figure 9, which compares the previous and reauthorized MCO tax packages, the reauthorized MCO tax is projected to generate a net General Fund benefit starting at $1.7 billion annually in 2019‑20, growing to over $2.1 billion by 2021‑22. Because the reauthorized MCO tax expires halfway through 2022‑23, a half-year of revenue will be collected that year.

Figure 9

Comparing the Fiscal Impacts of Previous and Reauthorized MCO Tax Packagesa

LAO Estimates (In Millions)

|

State Impact |

Previous Tax |

Reauthorized Tax |

||||||

|

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23b |

||

|

Total MCO tax revenue |

$2,283 |

$2,429 |

$2,564 |

$2,631 |

$2,958 |

$3,293 |

$1,810 |

|

|

General Fund cost of Medi‑Cal reimbursement to MCOs |

‑838 |

‑911 |

‑970 |

‑915 |

‑1,029 |

‑1,144 |

‑629 |

|

|

Insurance and corporation tax offsets |

‑386 |

‑322 |

‑337 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Net General Fund Benefit |

$1,060 |

$1,195 |

$1,257 |

$1,716 |

$1,928 |

$2,149 |

$1,181 |

|

|

Health Insurance Industry Impact |

||||||||

|

MCO tax liability |

$2,283 |

$2,429 |

$2,564 |

$2,631 |

$2,958 |

$3,293 |

$1,810 |

|

|

Medi‑Cal reimbursement to MCOs |

‑2,018 |

‑2,142 |

‑2,256 |

‑2,614 |

‑2,941 |

‑3,268 |

‑1,797 |

|

|

Offsetting tax reductions |

‑386 |

‑322 |

‑337 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Net Health Insurance Industry Benefit |

$120 |

$35 |

$29 |

‑$17 |

‑$17 |

‑$25 |

‑$12 |

|

|

aEstimates are based on accrual accounting and therefore do not reflect the year in which the revenues will be available to the state. bThe reauthorized MCO tax is scheduled to expire midway through 2022‑23, meaning only a half year of revenue will be collected that year. MCO = managed care organization. |

||||||||

Since Implementation Depends on Federal Approval, Revenues Remain Unallocated. MCO tax revenues are used to offset General Fund spending in Medi-Cal, which creates the net General Fund benefit. Since federal approval of the reauthorized MCO tax is pending and not certain, the spending plan does not allocate revenue from the reauthorized MCO tax to Medi-Cal. As such, the amount of General Fund dedicated to Medi-Cal in 2019‑20 is likely around $1 billion higher than it will ultimately be, provided the MCO tax receives federal approval and is implemented. It is our understanding that the 2020‑21 budget, either in January or May (depending on the timing of federal approval), will revise downward General Fund spending in Medi-Cal in 2019‑20 as a result of MCO tax revenues becoming available.

Other Medi-Cal Actions

Dedicates All Proposition 56 Funding in Medi-Cal to Provider Payment Increases. Proposition 56 (2016) raised taxes on tobacco products and dedicates the majority of ongoing revenues—about $1 billion annually—to Medi-Cal. As described in the bullets that follow, the spending plan uses all Proposition 56 funding for Medi-Cal to increase provider payments through a variety of mechanisms. In addition, under the spending plan—and unlike previous practice—DHCS will request multiyear federal approval of the provider payment increases. As shown in Figure 10, the spending plan dedicates over $1.2 billion in Proposition 56 funding—or $3.5 billion in total funding—to provider payment increases. As described above, all Proposition 56 provider payment increases in Medi-Cal are subject to the spending plan’s provisional suspension language, and therefore could end halfway through 2021‑22. Specifically, the details of the $1.2 billion in Proposition 56-funded provider rate increases are as follows:

- Continues Existing Provider Payment Increases. The spending plan extends nearly all of the existing Proposition 56 provider payment increases at their existing levels at a cost of $752 million in Proposition 56 funding ($2.2 billion in total funds).

- Establishes New Value-Based Payment Program. The spending plan provides $250 million in Proposition 56 funding ($544 million in total funds) to establish a value-based payment program whereby physicians will receive incentive payments for meeting various quality-based performance benchmarks. The payments are intended to improve quality in the areas of (1) pre- and post-partum care, (2) early childhood preventive care, (3) chronic disease management, and (4) behavioral and physical health integration. The spending plan establishes an intent to provide $180 million in Proposition 56 funding annually through 2021‑22, provided the suspension of Proposition 56 augmentations does not take place. Should the suspension take place, funding for the value-based payment program would likely be reduced by half in its final year.

- Provides Supplemental Payments for Additional Services and Providers. The spending plan provides $108 million in Proposition 56 funding ($619 million total funds) to expand supplemental payments to a variety of new services and providers. Figure 10 lists these new supplemental payments. Provided the suspensions do not take place, these new supplemental payments are intended to be ongoing.

- Augments Medi-Cal Student Loan Repayment Program. The 2018‑19 spending plan dedicated $220 million in Proposition 56 funding on a one-time basis to create a Medi-Cal physician and dentist student loan repayment program. The 2019‑20 spending plan provides an additional one-time amount of $120 million in Proposition 56 funding for this program, bringing total program funding to $340 million. Of the total, $290 million is designated for physicians and $50 million is designated for dentists.

Figure 10

2019‑20 Proposition 56 Medi‑Cal Spending Packagea

(In Millions)

|

Augmentation |

Proposition 56 Funds |

Total Funds |

|

Continue existing provider payment increasesb |

$752 |

$2,182 |

|

New Supplemental Payments: |

||

|

Value‑based payment programc |

250 |

544 |

|

Family planning services |

50 |

500 |

|

Developmental and trauma screenings |

37 |

97 |

|

Community‑based adult services |

14 |

14 |

|

Non‑emergency medical transportation |

6 |

6 |

|

Hospital‑based pediatric physician services |

2 |

2 |

|

Other: |

||

|

Physician and dentist student loan repaymentc |

120 |

120 |

|

Training for trauma screeningsc |

25 |

50 |

|

Totals |

$1,255 |

$3,515 |

|

aUnder the spending plan, all Proposition 56 augmentations are subject to potential suspension on December 31, 2021. bThese include payment increases for the following providers or services, most of which take the form of supplemental payments: physician services, dental services, women’s health, home health, pediatric day health care, Intermediate‑Care Facilities for the Developmentally Disabled, the AIDS Waiver Program and standalone pediatric subacute facilities. cWhile most Proposition 56 provider payment increases can be considered limited term, particularly in light of the provisional suspension language, these augmentations are explicitly intended to be limited term. |

||

Provides Resources to Improve Fiscal Oversight of Medi-Cal. In recent years, Medi-Cal expenditures have become increasingly difficult to predict and significant unanticipated changes to the Medi-Cal budget have become routine. The 2019‑20 budget package includes actions intended to improve the fiscal management of the Medi-Cal program and increase transparency for the Legislature. These actions include:

- Augmenting DHCS Staff. The Legislature approved the Governor’s proposal to provide $1.8 million from the General Fund ($3.8 million total funds) on an ongoing basis for additional staff at DHCS to improve monitoring of cash flows, increase reconciliation of spending to estimates, improve processing of payments and collections, and increase coordination among DHCS fiscal units.

- Establishing Drug Rebate Fund. The Legislature also approved the creation of a new special fund into which the state will deposit a portion of the drug rebate revenues, instead of using these revenues to immediately reimburse the General Fund. This is intended to smooth the impact of drug rebates, which can vary significantly from year to year, on the General Fund.

- Establishing Legislative and Administration Workgroup. Finally, the Legislature approved language directing the administration to convene a legislative working group to consult with legislative staff on longer-term options to improve fiscal management and transparency in Medi-Cal.

Restores Most Remaining Optional Benefits. In 2009, the state eliminated several optional Medi-Cal benefits, some of which have since been restored. The 2019‑20 budget restores most of the remaining optional benefits, including audiology, incontinence creams and washes, optical, podiatry, and speech therapy. The budget includes $17.4 million from the General Fund ($56.3 million total funds) in 2019‑20 for an assumed half-year of implementation.

Establishes Asthma Mitigation Project With One-Time Funding. The budget includes $15 million in one-time funding from the General Fund to support asthma prevention and environmental remediation services.

Behavioral Health Augmentations

Dedicates Significant One-Time Funding to Mental Health Workforce Programs. The spending plan includes a number of one-time augmentations related to mental health workforce development. The augmentations total $110 million, $85 million of which is General Fund and $25 million of which is from the Mental Health Services Fund (MHSF). This funding is divided among the following three programs:

- State Mental Health Workforce Programs. About $47 million General Fund is dedicated to state scholarship and student loan repayment programs administered by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). This funding is available for expenditure through 2024‑25. Of this funding, $1 million is specifically dedicated to student loan repayment for former foster youth.

- Workforce, Education, and Training (WET) Program. The Mental Health Services Act requires the state to develop five-year plans outlining strategies to meet the public mental health system’s workforce and education needs. Funding from the MHSF historically accompanied the five-year WET plans, but this funding recently expired. The spending plan dedicates $60 million ($35 million General Fund, $25 million MHSF) to fund the five-year WET plan spanning 2020 to 2025. This funding would be split among state WET programs administered by OSHPD and local WET programs administered by regional partnerships of county mental health agencies. For the regional partnerships to receive funding, they are required to provide 33 percent in matching local funds to support all the programs implemented under the 2020‑25 five-year WET plan. This funding is available for expenditure through 2025‑26.

- Psychiatry Fellowships for Primary Care Clinicians. Two University of California campuses—at Irvine and Davis—operate psychiatry fellowship programs for primary care clinicians—including physicians, physician assistants, and nurses—seeking advanced training and a certificate in primary care psychiatry. The spending plan provides $2.7 million General Fund to support scholarships for primary care and emergency physicians to participate in the psychiatry fellowship programs. To qualify, the physicians must demonstrate that their practices provide care to underserved populations. This funding is available for expenditure through 2024‑25.

Extends Medi-Cal Coverage for Post-Partum Mothers With Mental Health Disorders. Currently, women with incomes between 138 percent and 322 percent of FPL may qualify for Medi-Cal coverage of pregnancy and post-partum services—including services to treat mental health conditions—while they are pregnant and for 60 days after the end of a pregnancy. Budget legislation extends the 60-day period of post-partum eligibility to one year for women who have been diagnosed with specified maternal mental health conditions. The budget provides $8.6 million from the General Fund to DHCS to reflect this change. However, the administration believes that this change cannot be implemented in 2019‑20 and plans to implement the change during 2020‑21.

Provides $120 Million in General Fund to WPC-Related Activities. WPC pilots provide participating counties with support for integrating health, behavioral health, and social services for Medi-Cal beneficiaries who utilize multiple systems of care, including those who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. (As of September 2019, there are 27 participating counties.) The spending plan allocates $120 million from the General Fund to DHCS for WPC-related activities, as follows:

- $100 Million for Housing Services. Previously, the WPC pilot program has not provided additional funding to participating counties for housing services. The spending plan includes $100 million from the General Fund on a one-time basis to provide funding for housing supports in WPC pilot counties for individuals who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. These funds will be available for expenditure through June 2025.

- $20 Million to Improve Care Coordination in Non-WPC Pilot Counties. The spending plan also includes $20 million from the General Fund on a one-time basis for counties that do not participate in the WPC pilot program to develop programs that coordinate behavioral health services and social services for individuals with mental illness.

Funds Early Psychosis Research and Treatment. The spending plan includes $20 million in one-time funding from MHSF for the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (OAC) to support the Early Psychosis Intervention Plus (EPI Plus) program. The EPI Plus program was established through Chapter 414 of 2017 (AB 1315, Mullin), but no state funding has previously been appropriated. The funding included in the 2019‑20 spending plan for this program will support community services that help detect psychosis and mood disorders in adolescents and young adults before they become severe or disabling.

Provides $60 Million for Mental Health in Schools. The spending plan includes $50 million ($10 million ongoing) from the MHSF to facilitate partnerships between county mental health providers and K-12 education agencies through a competitive grant program. The spending plan also includes $10 million in one-time MHSF funds for the California Community Colleges (CCC) and the California State University (CSU) ($7 million for CCC and $3 million for CSU) for higher education mental health services.

Proposition 64 Revenues Available for Youth Substance Use Disorder Programs. Proposition 64 (2016) authorized certain new taxes on cannabis and allocated these taxes to specific purposes, including youth education, environmental restoration, and law enforcement. The spending plan includes $119.3 million from Proposition 64’s Youth Education, Prevention, Early Intervention, and Treatment Account (Youth Account), which, as stipulated by Proposition 64, is to be used broadly to educate about, prevent, and reduce harm from substance use disorder among youth. (See the “Cannabis Regulation” section in the “Other Provisions” spending plan post for more information about other tax allocations and regulation generally.) Specifically, the spending plan allocates $119.3 million from the Youth Account in 2019‑20 (the first fiscal year in which funds have been allocated for the broad purposes of youth substance use disorder programs) as follows:

- Additional Child Care Slots. $80.5 million will go to the California Department of Education to subsidize additional child care slots for income-eligible families. (See the “Early Education” section of the Education spending plan post.)

- Youth Substance Use Disorder Grant Program. $21.5 million will go to DHCS for a competitive grant program to develop and implement education, prevention, and early intervention of substance use disorders for youth. Some of the funding will also be available for local stakeholder engagement to inform program development, oversight, and administrative support.

- Cannabis Surveillance and Education. $12 million will go to the Department of Public Health (DPH) for data analysis, development of survey tools, and educational activities, including updating its “Let’s Talk Cannabis” website.

- Youth Community Access Grants. $5.3 million will go to the California Natural Resources Agency for grants supporting greater access to natural or cultural resources among youth from low-income families or disadvantaged communities.

Provides Funding for Substance Use Counselors in Emergency Departments. The spending plan includes $20 million one time from the General Fund to DHCS for the hiring of substance use disorder and behavioral health peer navigators to work in the emergency departments of acute care hospitals.

Provides Funding to Establish Youth Mental Health Drop-In Centers. The spending plan includes $15 million in one-time MHSF funding to OAC to establish local centers that provide integrated youth mental health services. These local centers will be modeled after a program developed in Santa Clara County that provides health, mental health, substance use, reproductive health, education, employment, and housing services to a target population of 12 to 15 year olds.

Other Adjustments. Budget legislation directs the administration to seek federal approval to expand the Medi-Cal benefit for screening, brief intervention, referral, and treatment to include screening for overuse of opioids and other illicit drugs. However, the spending plan does not include funding for this item because federal approval was not anticipated to be received during 2019‑20. The spending plan also includes $3.6 million in MHSF funding to DHCS over three years to support the peer-run warm line for emotional support operated by the Mental Health Association of San Francisco. Finally, the spending plan includes $15.2 million one time from the General Fund to DPH to fund peer navigators in harm reduction programs and $8 million one time from the General Fund for mental health disparities reduction, as described in the “Public Health” section of this post.

Department of State Hospitals (DSH)

Under the budget plan, General Fund spending for DSH will be $1.8 billion in 2019‑20, an increase of $39.4 million, or 2 percent, from the revised 2018‑19 level. The year-over-year net increase is largely related to the implementation of new staffing standards and the planned activation of additional Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) capacity, as discussed below. These increases are partially offset by various adjustments, such as the expiration of limited-term funding approved in prior years.

Implementation of New Staffing Standards. The budget includes a $23 million General Fund augmentation (growing to $64 million by 2022‑23) to implement two new sets of staffing changes. First, the budget includes $15 million to implement several changes related to the way nurses are staffed at the state hospitals. Specifically, the department will (1) standardize nursing staffing patterns and ratios across the five state hospitals, (2) establish psychiatric technician positions dedicated to staffing medication rooms, and (3) establish registered nurse supervisor positions to provide oversight during evening and overnight shifts. Second, the budget includes $8.1 million to create new positions and staffing standards for workload related to court evaluations and reports, as well as cognitive rehabilitation therapy.

Funding for Additional IST Capacity. The budget provides a $22 million General Fund augmentation for additional IST capacity. This includes $15.5 million for the activation of a secured treatment area at Metropolitan State Hospital, which will provide a total of 236 additional beds for the treatment of IST patients. It also includes $6.4 million for the department to contract with counties for up to 73 additional Jail-Based Competency Treatment (JBCT) beds through both existing and new county JBCT programs.

Other Adjustments. The budget also provides various other General Fund augmentations. This includes (1) $15 million for deferred maintenance projects, (2) $10.5 million for patient-related operating expenses, (3) $5.8 million to maintain the expanded capacity of the DSH hospital police academy, (4) $5.7 million to contract for additional beds to serve certain patients preparing for release, and (5) $4.9 million to relocate the department’s headquarters.

Department of Public Health

The spending plan provides $3.4 billion from all fund sources for DPH programs in 2019‑20, up 7.9 percent from the revised 2018‑19 estimate of $3.2 billion. Of the total, General Fund spending accounts for $307 million, an increase of 73 percent from $177.3 million in 2018‑19. Funding for new initiatives totals $159.1 million General Fund, of which two-thirds is one time in nature.

Increased Funding for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Including Spending to Address Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) and HIV. The spending plan provides $57 million General Fund to address infectious diseases, allocated as follows:

- Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control. $40 million General Fund one time, available over four years, primarily for local health jurisdictions to strengthen their infectious disease control and prevention infrastructure—$36 million is for local assistance, while $4 million is for state operations. Of the $36 million, $1 million is designated for tribal communities. Associated budget act language specifies that DPH shall work with stakeholders, including community-based organizations and the associations that represent local health jurisdictions, to determine the allocation methodology.

- STD-Specific Funding. $17 million General Fund is for STD prevention and control. Of the total, $7 million is to address STDs generally, $5 million is to address HIV specifically, and $5 million is to address Hepatitis C. Of the total, $15 million is subject to the December 31, 2021 suspension language discussed earlier.

Expansion of the Home Visiting and Black Infant Health Programs. The Governor proposed, and the Legislature approved, increased spending of $30.5 million from the General Fund to expand two DPH programs for mothers and young children. The spending plan assumes this General Fund expenditure will draw down an additional $34.8 million in federal matching funds.

- California Home Visiting Program. This program currently operates in 23 of California’s 58 counties, providing evidence-based home visiting services by nurses or paraprofessionals to pregnant women, new mothers, and young children. Participating women must have at least one of five risk factors, such as inadequate income or domestic violence. The program, established in 2010, has historically been funded with a federal grant. The spending plan provides $23 million General Fund to expand the program and draw down an estimated $22.9 million in additional federal funds. DPH plans to provide services to additional counties, expand services in current counties, and offer additional evidence-based models of services. Of note, the Department of Social Services recently began rolling out its own home visiting program, which is available to mothers enrolled in the CalWORKs program.

- Black Infant Health Program. The spending plan provides $7.5 million General Fund to expand the Black Infant Health Program; this is expected to draw down an additional $12 million in federal funds. This augmentation will more than triple what has been spent on this program in recent years ($4 million from the General Fund and slightly more than $4 million in federal matching funds). The Black Infant Health Program seeks to improve the health of black mothers and infants by offering evidence-informed services and support through group sessions, health education, and case management.

Public Health Interventions to Treat Special Populations. The spending plan provides $59.7 million from the General Fund for the following purposes:

- Lesbian, Bisexual, and Queer (LBQ) Women’s Health. One-time funding of $17.5 million General Fund to improve health outcomes among LBQ women. Funding will support competitive grants and research to better understand the needs of this population, improve access to care and the quality of care, train health care providers, conduct public awareness campaigns, and expand research on LBQ women’s health.

- Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Response Navigators. $15.2 million General Fund one time, available over four years, for grants to harm reduction programs, including syringe exchange programs, that seek to connect individuals with SUD to effective treatment, health care, and other community services. Most of the grant funding will be used to increase the number of program staff (navigators) serving this population.

- Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Infrastructure. $15 million General Fund on a one-time basis, available over three years, to establish several sickle cell disease centers of excellence in several local health jurisdictions around the state, including Alameda, Fresno, Kern, Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Bernardino, and San Diego Counties. DPH will administer start-up funds to organizations through a competitive grant program. The centers will train providers, monitor and track disease incidence and outcomes, and conduct education and public awareness campaigns for affected communities.

- Mental Health Equity Programs. $8 million General Fund one-time, available over three years to address and improve mental health outcomes among California’s diverse communities. The funding is allocated as follows:

$5 million for grants awarded on a competitive basis to community-based organizations working in partnership with county behavioral health departments to develop and implement culturally competent mental health approaches for underserved populations.

$3 million for DPH to provide technical assistance to county behavioral health departments as they develop cultural competency plans, engage stakeholders, and organize educational sessions about reducing mental health disparities.

- Valley Fever Institute at Kern Medical Center. $2 million General Fund on a one-time basis, available over two years, for research on Valley Fever at Kern Medical Center in Bakersfield. The 2018‑19 spending plan also provided $3 million General Fund on a one-time basis to Kern Medical Center for the same purpose.

- Study of Farmworkers’ Health. $2 million General Fund one time, available over three years, to support a study examining the health of California’s farmworkers.

Alzheimer’s-Related Spending and Governor’s Task Force on Alzheimer’s Prevention and Preparedness. The spending plan provides $8 million from the General Fund for several initiatives related to Alzheimer’s disease:

- Local Infrastructure—Healthy Brain Initiative. $5 million one time, available over three years, for grants in up to six local health jurisdictions to increase Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment infrastructure, including diagnostic screening, disease management, and caregiver support.

- Program Grant Awards. $2.4 million in 2019‑20 ($2.7 million annually thereafter) for research grants focused on understanding the higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease among women and communities of color. Grant funding will also seek to increase early detection and diagnosis and develop effective approaches to treatment and caregiver support.

- State Operations and Governor’s Task Force on Alzheimer’s Prevention and Preparedness. $600,000 General Fund in 2019‑20 ($300,000 annually thereafter) for DPH costs associated with administering program grants and supporting the Governor’s Task Force on Alzheimer’s Prevention and Preparedness. The higher level of funding in 2019‑20 will support some of the initial task force development and implementation activities.

Support for the International AIDS Conference. The spending plan includes $2 million General Fund one time, available over three years, to provide funding to the host cities of San Francisco and Oakland in support of the 23rd Biennial International AIDS Conference.

Increased Funding for the Safe Cosmetics Program. The spending plan includes $1.5 million General Fund in 2019‑20 ($500,000 annually thereafter) for the Safe Cosmetics Program, which collects information about hazardous chemicals in cosmetics and personal care products and makes the information public. Funding will support one-time information technology upgrades and additional enforcement, research, and outreach activities.