LAO Contacts

- Sara Cortez

- School Nutrition

- Kenneth Kapphahn

- Overall Proposition 98 Package

- The Minimum Guarantee

- Amy Li

- Special Education

- Education Workforce

- Ned Resnikoff

- Local Control Funding Formula

- Addressing the Acheivement Gap

Correction 2/26/20: Corrected reference to the cost of the Governor’s education workforce proposals.

February 24, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

Proposition 98 Education Analysis

- Introduction

- Overall Proposition 98 Package

- The Minimum Guarantee

- Local Control Funding Formula

- Special Education

- Education Workforce

- Addressing the Achievement Gap

- School Nutrition

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess the architecture of the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 budget and analyze his specific proposals for K‑12 education.

Overall Proposition 98 Budget

$3.7 Billion in New Proposition 98 Spending Proposals. The new spending consists of $3.3 billion for K‑12 schools and $388 million for community colleges. Across both segments, slightly more than half ($2 billion) is for one‑time initiatives and the remainder ($1.7 billion) is for ongoing augmentations. Nearly all of the ongoing funding is to cover an estimated 2.29 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment for various K‑14 programs. Total K‑12 funding per student would grow to $12,619 in 2020‑21, an increase of $499 (4.1 percent) over the revised 2019‑20 level.

Many of the Governor’s One‑Time Initiatives Would Not Address Root Issues. Most of the Governor’s one‑time initiatives seek to improve the education workforce or address poor performance among certain districts and schools. Many of the proposals, however, seem unlikely to have much long‑term effect on these issues. We also are concerned that many proposals are missing important details regarding how the funds would be spent. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature reject most of these proposals, freeing up more than $1 billion in Proposition 98 funds relative to the Governor’s budget. In some cases, we provide alternative options that would align more closely with existing efforts to address the root problems. These alternatives could be structured to cost less than the amounts proposed by the Governor.

Legislature Could Use Freed‑Up, One‑Time Funds to Pay Down Pension Liabilities. School districts face fiscal pressures ranging from rising pension costs to higher costs for special education. Though nearly all districts currently hold positive budget ratings, we expect districts to face more difficulty balancing their budgets in the upcoming year. To the extent the Legislature rejects some of the Governor’s one‑time proposals, we think it should consider using the freed‑up funds to provide fiscal relief. Of all the available options, we think making additional payments toward districts’ unfunded pension liabilities would offer the greatest fiscal benefit. Paying down these liabilities would improve the funding status of the pension systems and likely reduce district costs over time.

Key Messages

Special Education Base Proposal Would Reduce Historical Inequities. The administration proposes to make reforms in special education financing and other areas over a multiyear period. In this first year, the administration’s largest proposal is $645 million ongoing to ensure base rates for all special education local plan areas are at least $660 per student. We recommend the Legislature adopt this proposal. By reducing variations in base rates, the proposed new rate would address inequities that have persisted for decades.

Recommend the Legislature Take Different Approach in Other Special Education Proposals. In addition to the proposed special education base augmentation, the Governor’s budget provides $250 million one time to increase or improve special education services for preschool‑aged students. The proposal sends a confusing message to districts, as districts are unlikely to hire the additional staff necessary to provide these services with one‑time funding. As an alternative, we recommend using the $250 million to provide ongoing funding for preschool‑aged children through the state’s base special education formula. This approach would recognize the ongoing costs associated with serving this age group. The administration also proposes $1.1 million one time for a governance study and two workgroups to inform future special education reforms. We encourage the Legislature to think carefully about the concerns it would like to address and consider funding studies to provide more concrete options on these issues. In adopting its 2020‑21 budget, the Legislature could also address other key priorities not directly related to the special education funding model, such as expanding existing initiatives that provide districts technical assistance to implement inclusive practices.

Recommend Rejecting Opportunity Grants Proposal. The Governor’s budget provides $300 million one time to provide grants and support to low‑performing districts and schools where at least 90 percent of students are low income. Key elements of the Governor’s proposal, including the vision and scope of the grant program, are left entirely to the discretion of the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence and the State Board of Education. As a result, the proposal lacks sufficient detail for the Legislature to determine whether this approach would be an effective way to improve outcomes for low‑performing districts and schools. Additionally, the administration appears to have developed this proposal without considering how this funding would align with existing funding provided to support low‑performing schools and districts. We recommend the Legislature reject the proposal and instead consider a smaller ongoing augmentation to assist a smaller subset of districts with significant performance issues.

Recommend Funding Smaller Community Schools Pilot With Greater Emphasis on Technical Assistance. The Governor’s budget provides $300 million in one‑time funding to provide grants to school districts interested in implementing the community schools model. Our review finds that the community schools model is associated with improved student outcomes, but can be difficult to implement. The Governor’s proposal stipulates that grant recipients will receive technical assistance, but does not include any requirements for the level of assistance they would receive. The Governor’s proposal also includes no rules or requirements for how the grant funds could be spent. To provide greater certainty that grantees would implement a community schools model effectively, we recommend the Legislature fund a smaller grant program that focuses on technical assistance.

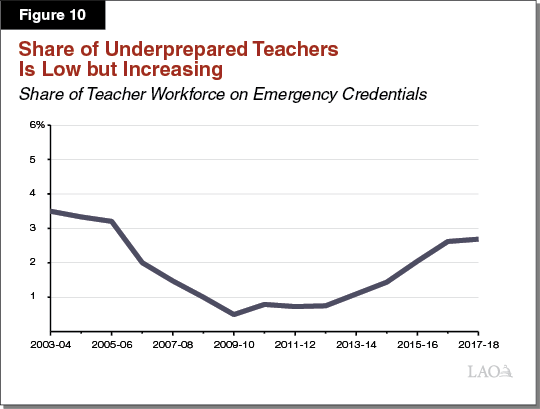

Recommend Approving Smaller Package of Proposals to Address School Workforce Shortages. The administration proposes a total of $532 million one time for various proposals aimed at addressing school workforce needs. We recommend the Legislature approve a total of $93.1 million for two programs—one that helps school employees earn a teaching credential and another that trains prospective teachers by pairing them with experienced mentor teachers in the classroom. These programs have shown some promise in expanding teacher supply and improving teacher preparation, respectively. We recommend the Legislature reject the other one‑time proposals in this areas, as they do not address the underlying factors contributing to workforce shortages.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. The first section analyzes the architecture of the Proposition 98 budget, with an overview of the new Proposition 98 spending, a review of the key fiscal issues facing school districts, and our overarching comments on the Governor’s proposals. The second section describes the underlying changes in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee that support the Governor’s proposed spending level and explains how the guarantee could change in the coming months. The five remaining sections of this report examine the Governor’s major proposals involving K‑12 education. Specifically, we analyze his proposals for (1) the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), (2) special education, (3) the education workforce, (4) closing achievement gaps, and (5) child nutrition.

Other Education Budget Analyses Complement This Report. The first section of this report summarizes the Proposition 98 spending changes affecting the California Community Colleges, but we analyze specific community college proposals separately in The 2020‑21 Budget: Higher Education Analysis. We analyze the Governor’s proposals for State Preschool in The 2020‑21 Budget: Early Education Analysis. In our January report, The 2020‑21 Budget: School District Budget Trends, we provide detailed information about compensation, staffing, pensions, and other cost pressures affecting school district budgets. On the “EdBudget” portion of our website, we post dozens of tables containing additional details about the Governor’s education proposals.

Overall Proposition 98 Package

In this section, we describe the main features of the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending package, review some key fiscal issues facing school districts, and provide our overall assessment of the Governor’s package.

Overview of New Spending

Governor Proposes $3.7 Billion in New Proposition 98 Spending. The Governor’s January budget package contains a total of $3.7 billion in new Proposition 98 spending across the 2018‑19 through 2020‑21 period. This amount consists of $3.3 billion for K‑12 education and $388 million for the California Community Colleges (Figure 1). Of the new spending, $2 billion is for one‑time initiatives and $1.7 billion is for ongoing commitments.

Figure 1

Governor’s Proposition 98 Spending Proposalsa

(In Millions)

|

K‑12 Education |

|

|

Ongoing |

|

|

COLA (2.29 percent) and attendance changes for LCFF |

$1,206 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (2.29 percent)b |

126 |

|

Child nutrition reimbursement rate increase |

60 |

|

Other |

6 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,398) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Educator Workforce Investment Grants |

$350 |

|

Community school grants |

300 |

|

Opportunity grants |

300 |

|

Special education preschool grant |

250 |

|

Grants to address school staffing shortages |

193 |

|

Teacher Residency Grant Program |

175 |

|

Stipends for teachers in hard‑to‑staff subjects/schools |

100 |

|

Inclusive Early Education Expansion Program |

75 |

|

Classified employees credentialing program |

64 |

|

Literacy grants |

53 |

|

County coordination grants |

18 |

|

Computer science resources for educators |

18 |

|

Refugee student services |

15 |

|

Other |

21 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,932) |

|

Total K‑12 Education |

$3,329 |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Ongoing |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (2.29 percent) |

$167 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

32 |

|

Apprenticeship instructional hours |

28 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs |

22 |

|

Immigrant legal and support services |

16 |

|

California Apprenticeship Initiative |

15 |

|

Other |

16 |

|

Subtotal |

($296) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Funding for current‑year apprenticeship costs |

$20 |

|

Work‑based learning initiative |

20 |

|

Deferred maintenance |

17 |

|

Faculty diversity fellowships |

15 |

|

Other |

20 |

|

Subtotal |

($93) |

|

Total California Community Colleges |

$388 |

|

Total Spending Proposals |

$3,717 |

|

aReflects all proposals scored to 2018‑19, 2019‑20, or 2020‑21, including reappropriations. bApplies to special education, state preschool, child nutrition, mandates block grant, charter school facility grants, services for foster youth, adults in correctional facilities, and American Indian education. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment and LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula. |

|

Largest Share of One‑Time Funding Allocated for Improving the Education Workforce. The largest allocation of one‑time funding consists of $882 million for five initiatives aimed at improving school employee training, recruitment, and retention. Most of these initiatives would be allocated as competitive grants. According to the Governor’s budget summary, the goals of these initiatives include (1) addressing teacher shortages in high need areas, including special education, science, and math; and (2) better preparing teachers and administrators to address the social‑emotional needs of their students.

Budget Funds Two One‑Time Initiatives Intended to Close Achievement Gaps. The budget provides $600 million for two new grant programs intended to address poor academic outcomes for specific student subgroups. The Opportunity Grant program would provide $300 million for grants to help improve academic outcomes for low‑performing schools and districts. Grant recipients also would receive additional technical assistance through the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE). The Community Schools program would provide $300 million to support the implementation and expansion of the community schools model—an approach that integrates health, mental health, and other services for students and families and provides these services directly on school campuses.

Nearly All Ongoing Funding Dedicated to Covering Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA). The Governor’s budget dedicates most of the $1.7 billion in new ongoing funding to covering the statutory COLA (projected at 2.29 percent) and changes in student attendance. Specifically, the budget provides an associated $1.2 billion for the LCFF, $167 million for community college apportionments, and $147 million for various other school and community college programs (including special education, preschool, and adult education). The other ongoing augmentations besides COLA also relate to existing programs.

Funding Rises Steadily Each Year of the Period. Figure 2 shows the overall distribution of funding by segment over the budget period. For each year, the Governor proposes to set total funding at the amount required to meet the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. In per‑student terms, funding for K‑12 education would grow to $12,619 in 2020‑21, an increase of $499 (4.1 percent) over the revised 2019‑20 level.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment

Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student

|

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Revised |

2020‑21 Proposed |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Funding |

|||||

|

K‑12 Educationa |

$69,253 |

$71,572 |

$74,279 |

$2,707 |

3.8% |

|

California Community Colleges |

9,195 |

9,477 |

9,807 |

330 |

3.5 |

|

Reserve deposit (+) or withdrawal (‑)b |

‑ |

524 |

‑38 |

‑562 |

‑ |

|

Totals |

$78,448 |

$81,573 |

$84,048 |

$2,475 |

3.0% |

|

Enrollment |

|||||

|

K‑12 attendance |

5,912,934 |

5,905,605 |

5,886,490 |

‑19,115 |

‑0.3% |

|

Community college FTE studentsc |

1,122,691 |

1,123,753 |

1,119,421 |

‑4,332 |

‑0.4 |

|

Funding Per Student |

|||||

|

K‑12 Education |

$11,712 |

$12,119 |

$12,619 |

$499 |

4.1% |

|

California Community Colleges |

8,190 |

8,433 |

8,761 |

328 |

3.9 |

|

aIncludes funding for instruction provided directly by state agencies and the portion of State Preschool funded through Proposition 98. bProposition 98 Reserve established by Proposition 2 (2014). cChange from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21 reflects lower baseline enrollment, partially offset by proposed growth. FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Funding Per Student at All‑Time High. Adjusted for inflation, the per‑student funding levels proposed by the Governor would be the highest since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. Compared with the previous all‑time high in 2000‑01, the proposed funding level for K‑12 education is up nearly $900 per student. The 2020‑21 budget would mark the fourth consecutive year in which per‑student funding exceeds the previous all‑time high.

District Fiscal Issues

Turning to a District Perspective. In this part of the report, we shift from an overview of the Governor’s budget to the fiscal trends affecting school district budgets. While each district’s budget is unique, most districts in the state are being affected by the following issues: (1) rising pension costs; (2) continued pressure to increase compensation; (3) declining attendance; and (4) following several years of strong growth, slower growth in school funding. We discuss each of these issues below.

School Pension Costs Set to Increase. Required district contributions to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) have grown from $3.5 billion in 2013‑14 to $8.7 billion in 2019‑20. (CalSTRS administers pension benefits for teachers, administrators, and other certificated employees, whereas CalPERS administers pension benefits for classified employees, such as cafeteria workers.) The rise in costs primarily reflects efforts to address the large unfunded liabilities the two pension systems accrued over the past few decades. For 2020‑21, school districts’ total contributions to CalSTRS and CalPERS are likely to increase by another $800 million to $1 billion.

Pressure to Increase Compensation Likely to Remain High. Available data show the average teacher in California earned a salary of $82,700 in 2018‑19, an increase of about $11,300 over the 2013‑14 level. (After accounting for inflation, the increase is about $4,000. The state also required teachers to make additional contributions to CalSTRS.) Though classified employees typically have lower salaries than teachers, available data suggest their salaries have grown at a similar rate. Despite these increases, we expect districts to continue facing salary‑related pressure because housing and other personal costs of living in California are relatively high and growing.

Student Attendance Likely to Continue Declining. Student attendance in California has declined every year since 2013‑14 and is projected to continue declining over the next several years. The decline is attributable to decreases in the number of births in California and overall out‑migration of school‑aged children. Some areas, including Los Angeles, Orange, and Santa Clara counties are in the midst of particularly large declines. Attendance declines can sometimes ease certain pressures. For example, districts with declining attendance tend to face less pressure to hire additional teachers. Most districts, however, report that declining attendance usually leads to tighter budgets. This is because state funding tends to decline in tandem with falling attendance, but certain district costs—such as central administration and facility maintenance—do not decline as smoothly. To balance their budgets, districts with declining attendance sometimes need to make notable adjustments (such as closing schools or consolidating programs). Available data also show that most districts are seeing an increase in the number of students with disabilities. This trend means districts face continued pressure to hire aides and other specialists to support these students despite the drops in overall district attendance.

School Funding Growing at a Slower Pace Compared With Recent Years. From 2013‑14 through 2018‑19, annual growth in K‑12 funding per student averaged 5.9 percent—notably higher than the 3.8 percent average dating back to 1988‑89. (These growth rates are unadjusted for inflation.) These increases were due mainly to significant growth in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. They also helped districts respond to their various cost pressures. Since 2019‑20, however, growth in the minimum guarantee has begun to slow. Under the Governor’s budget, Proposition 98 funding per student grows by 3.5 percent in 2019‑20 and 4.1 percent in 2020‑21—more in line with the historical average.

Most Districts Currently Hold Positive Budget Ratings. Districts respond to cost pressures in different ways, with decisions about salary, benefits, and staffing often varying notably even among neighboring districts with similar student demographics and overall funding levels. The latest available data suggest that most districts have been able to make trade‑offs among these competing pressures in ways that allow them to balance their budgets. As of December 2019, 96 percent of school districts held positive budget ratings. As funding growth slows, however, districts likely will face more difficulty balancing their budgets moving forward.

Comments

Proposition 98 Package Contains a Cushion in Event of Downturn. One important feature of the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan is that it sets aside funding in the budget year for one‑time activities. Specifically, of the $2 billion in new one‑time funds, $1.4 billion is attributable to 2020‑21. The advantage of this budgeting approach is that if the guarantee falls below projections, the expiration of these one‑time activities provides a cushion that reduces the likelihood of cuts to ongoing K‑14 programs. Such an approach seems particularly prudent this year, given the economic risks we discuss later in this report. Regardless of the specific programs the Legislature decides to fund in 2020‑21, we recommend it adopt a final budget plan that continues to include a mix of ongoing and one‑time spending.

Some One‑Time Proposals Unlikely to Address Root Issues. Most of the one‑time proposals in the Governor’s budget seek to address longstanding issues in K‑12 education, such as recruiting and retaining a well‑trained education workforce and improving outcomes in low‑performing schools and districts. Many of the proposals, however, seem unlikely to have a long‑term effect on these issues. Specifically, we are concerned that the proposals are not directly connected to the underlying problems or aligned with existing state and federal programs intended to address those problems. We also are concerned that many proposals are missing important details regarding how the funds would be spent. As we discuss in subsequent sections of this report, we recommend rejecting most of these proposals, freeing up more than $1 billion inside the guarantee. In some cases, we provide alternative options that would align more closely with existing efforts to address the root problems. These alternatives could be structured to cost less than the amounts proposed by the Governor.

Budget Provides Relatively Little Fiscal Relief for Districts. Nearly all of the one‑time proposals in the Governor’s budget would require districts to implement new programs or expand services as a condition of receiving funding. Most school districts, however, are facing relatively tight budgets compared to previous years. For example, the entire $1.2 billion increase associated with the LCFF COLA is only slightly above the expected increase in pension costs. Given these dynamics, we think districts would have difficulty implementing and sustaining so many new initiatives. To the extent the Legislature rejects some of these proposals, we think it should consider using the freed‑up funds to provide districts with additional fiscal relief. This approach could help districts prioritize the local programs and services they find most effective.

Using One‑Time Funds for Pensions Could Help Address a Key Cost Pressure. Many school districts regard higher pension costs as their most significant fiscal challenge. To help districts address this issue, the Legislature could use a portion of the freed‑up Proposition 98 funding to pay down districts’ unfunded pension liabilities more quickly. Under this approach, the state would make a payment on top of the previously scheduled increase in district contributions for 2020‑21. Paying down unfunded liabilities would improve the funding status of the pension systems. It also would likely reduce district pension costs over the next few decades—potentially making district budgets easier to balance on a sustained basis. Alternatively, if the Legislature wanted to provide more relief specifically in the upcoming year, it could consider using a portion of the one‑time funding to smooth out pension rate increases in 2020‑21. Although this approach lacks the potential for long‑term savings, it could improve districts’ fiscal health in the immediate future. The nearby box describes these options in more detail.

State Could Reduce Districts’ Pension Costs Over the Long Term

Long‑Term Savings Could Be Achieved Through Supplemental Payments. Both California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) have unfunded liabilities—meaning actuaries estimate that, based on various assumptions about the future (for example, investment returns and life expectancy), the pension systems have insufficient assets to pay future benefits that have been earned by members. The state and school districts share responsibility for paying down the CalSTRS unfunded liability, whereas districts are entirely responsible for any unfunded liability in their CalPERS plans. The state could make a supplemental payment to CalSTRS or to CalPERS on behalf of districts. In other words, the state could pay a lump sum toward districts’ share of the pension systems’ unfunded liabilities above what districts already owe in a given year. This action would reduce school districts’ unfunded liabilities and provide annual savings to school districts over the next few decades.

These savings could be significant. Given the estimate of savings is based on future investment returns and other economic and demographic assumptions, however, there is uncertainty about the ultimate amount districts would save. Using a recent CalSTRS analysis that included thousands of possible scenarios, estimated savings over the next few decades from a $1 billion supplemental payment likely could range from $1 billion to $3.3 billion (including the $1 billion supplemental payment). Overall, the average savings was $2.3 billion and in 75 percent of scenarios, the savings exceeded $1 billion. In general, it is our understanding that a supplemental payment to CalPERS has a higher probability of achieving savings over the next few decades. Ultimately, each district’s share of any CalSTRS or CalPERS savings would be proportional to its share of payroll covered by that pension system.

State Could Reduce Districts’ Pension Costs This Budget Year

Immediate Savings Could Be Achieved Through One‑Time Contribution Rate Relief. An alternative option is to provide immediate budget relief by using one‑time funds to lower the cost of districts’ CalSTRS or CalPERS contributions specifically in 2020‑21. Under this alternative, the state’s payment would cover a portion of the contribution that school districts otherwise would be required to make—resulting in a lower effective contribution rate for that year. While this approach would reduce costs to school districts in the budget year, it would have no effect on districts’ outstanding, unfunded liabilities or future contribution requirements. Consequently, such a payment would not result in savings beyond the budget year.

Unique Case Can Be Made for Small Amount of One‑Time CalSTRS Relief. While we think achieving longer‑term savings would be more beneficial to districts than one‑time savings, providing a small amount of a one‑time CalSTRS rate relief in 2020‑21 deserves some special consideration. Districts’ effective CalSTRS rate (as a percent of payroll) is scheduled to increase from 17.1 percent in 2019‑20 to 18.4 percent in 2020‑21, then decrease to around 18.1 percent in 2021‑22 (and remain approximately flat thereafter). One‑time funds could be used to eliminate this rate hump, allowing for smoother increases over the next few years. For example, the state could use one‑time funds to lower districts’ contribution rate by 0.8 percent of payroll in 2020‑21, meaning districts’ effective rate would increase by 0.5 percent in 2020‑21 and another 0.5 percent in 2021‑22. We estimate this rate smoothing would cost approximately $300 million. (All other one‑time funds could be used for supplemental payments to provide districts longer‑term savings.)

The Minimum Guarantee

In this section, we provide background on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, analyze the administration’s estimates of the guarantee, and explain how the guarantee could change in response to updated revenue estimates.

Background on Minimum Guarantee

Proposition 98 Established the Minimum Guarantee. Proposition 98 (1988) established a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue.

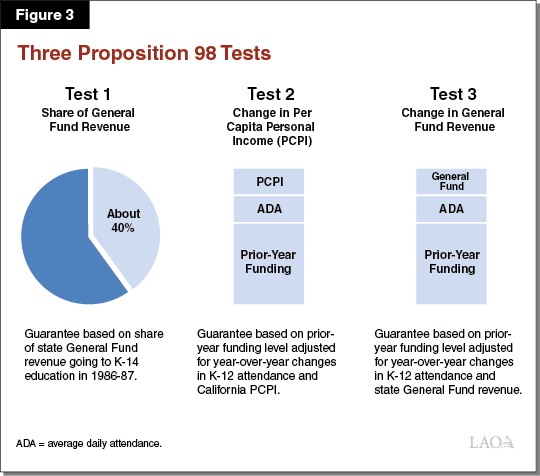

Minimum Guarantee Depends Upon Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main tests for calculating the minimum guarantee. Each test has certain inputs. The most notable inputs are General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance (Figure 3). Whereas Test 2 and Test 3 build upon the amount of funding provided the previous year, Test 1 links school funding to a minimum share of General Fund revenue (about 40 percent). The Constitution sets forth rules for comparing the tests, with one of the tests becoming operative and used for calculating the minimum guarantee that year. Although the state can provide more funding than required, in practice it usually funds at, or near, the guarantee. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year.

At Key Points, the State Recalculates Minimum Guarantee. The guarantee typically changes from the level initially assumed in the budget act as a result of updates to the relevant Proposition 98 inputs. The state continues to update Proposition 98 inputs until the following May after the close of a fiscal year. If these updates show that the revised minimum guarantee exceeds the initial estimate, the state makes a one‑time payment to “settle up” the difference. The Legislature can allocate these settle‑up payments for any school or community college program.

Proposition 98 Reserve Has Rules for Deposits and Withdrawals. Proposition 2 (2014) created a state reserve specifically for schools and community colleges—the Public School System Stabilization Account (Proposition 98 Reserve). The Constitution requires the state to deposit Proposition 98 funding into this account when the minimum guarantee is growing relatively quickly and other conditions are met (see the nearby box). When the guarantee is growing relatively slowly, the Constitution requires the state to withdraw funds from the reserve and allocate them for school and community college programs. The state continues to update its calculation of any required deposits or withdrawals for up to nine months after the close of the fiscal year.

Key Rules Governing the Proposition 98 Reserve

Below, we describe the rules governing Proposition 98 Reserve deposits and withdrawals.

Deposits Predicated on Four Main Conditions. To determine whether a deposit is required, the state first determines whether all of the following conditions are met:

- Revenues From Capital Gains Are Relatively Strong. Deposits are required only when the state receives an above‑average amount of revenue from taxes paid on capital gains (a relatively volatile source of General Fund revenue).

- Test 1 Is Operative. Test 1 years historically have been associated with relatively strong growth in the minimum guarantee due to strong growth in state revenue.

- Formulas Are Not Suspended. If the Governor declares a “budget emergency” (based on a natural disaster or slowdown in state revenues), the Legislature can reduce or cancel a Proposition 98 Reserve deposit. Additionally, if the Legislature votes to suspend the minimum guarantee, any required deposit is automatically canceled.

- Obligations Created Before 2014‑15 Are Retired. Proposition 2 (2014) specified that no deposits would be required until the state paid certain school funding obligations (known as “maintenance factor”) that it accrued during the Great Recession. The state met this condition starting in 2019‑20.

Amount of Deposit Depends Upon Additional Formulas. If the state determines that the conditions for a deposit are satisfied, it performs several calculations to determine the size of the deposit. Generally, the size of the deposit tends to increase when the revenue from capital gains is relatively high and the guarantee is growing quickly relative to inflation. More specifically, the deposit equals the lowest of the following four amounts:

- The Portion of the Guarantee Attributable to Above‑Average Capital Gains. The state calculates what the Proposition 98 guarantee would have been if the state had not received any revenue from capital gains in excess of the historical average. Deposits are capped at the difference between the operative guarantee and the hypothetical alternative guarantee without the additional capital gains revenue.

- The Difference Between Test 1 and Test 2 Levels. Deposits are capped at the difference between the higher Test 1 and lower Test 2 funding levels.

- Growth Relative to the Prior Year. The state calculates how much funding schools and community colleges would receive if it adjusted the previous year’s funding level (excluding any deposits that year) for changes in student attendance and inflation. The inflation factor is the higher of the cost‑of‑living adjustment or growth in per capita personal income. Deposits are capped at the difference between the Test 1 funding level and the inflation‑adjusted prior‑year funding level.

- Room Available Under a 10 Percent Cap. The Proposition 98 Reserve has a cap equal to 10 percent of all funding allocated to schools and community colleges. Deposits are only required to the extent the existing balance is below this threshold.

Withdrawals Required When Guarantee Is Growing Relatively Slowly. Proposition 2 requires the state to withdraw funds from the Proposition 98 Reserve if the minimum guarantee is not growing quickly enough to support the prior‑year funding level, as adjusted for student attendance and inflation.

Administration’s Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee

Minimum Guarantee Revised Upward in 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. Compared with the estimates included in the June 2019 budget plan, the administration revises its estimates of the minimum guarantee to increase by $302 million in 2018‑19 and $517 million in 2019‑20 (Figure 4). In 2018‑19, the increase mainly reflects higher estimates of local property tax revenue. (In Test 1 years like 2018‑19 and 2019‑20, changes in local property tax revenue directly affect the level of the minimum guarantee. They do not offset General Fund spending.) In 2019‑20, the increase in the minimum guarantee mainly reflects higher General Fund revenue.

Figure 4

Tracking Changes in Proposition 98 Guarantee

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

||||||

|

June 2019 Estimate |

January 2020 Estimate |

Change |

June 2019 Estimate |

January 2020 Estimate |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$54,445 |

$54,505 |

$61 |

$55,891 |

$56,405 |

$514 |

|

|

Local property tax |

23,701 |

23,942 |

241 |

25,166 |

25,168 |

3 |

|

|

Totals |

$78,146 |

$78,448 |

$302 |

$81,056 |

$81,573 |

$517 |

|

|

Operative Test |

2 |

1 |

yes |

1 |

1 |

no |

|

2020‑21 Guarantee Increases $2.5 Billion Over Revised 2019‑20 Level. The administration estimates that the minimum guarantee is $84 billion in 2020‑21, an increase of $2.5 billion (3 percent) over the revised 2019‑20 level (Figure 5). Test 1 is operative, with the guarantee receiving about 40 percent of the General Fund revenue projected for 2020‑21. Growth in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue each account for about half of the increase in the guarantee.

Figure 5

Proposition 98 Key Inputs and Outcomes Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||

|

General Fund |

$54,505 |

$56,405 |

$57,573 |

|

Local property tax |

23,942 |

25,168 |

26,475 |

|

Totals |

$78,448 |

$81,573 |

$84,048 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||

|

General Fund |

$1,554 |

$1,899 |

$1,168 |

|

Percent change |

2.9% |

3.5% |

2.1% |

|

Local property tax |

$1,317 |

$1,226 |

$1,307 |

|

Percent change |

5.8% |

5.1% |

5.2% |

|

Total guarantee |

$2,871 |

$3,126 |

$2,475 |

|

Percent change |

3.8% |

4.0% |

3.0% |

|

Operative Test |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

‑0.8% |

‑0.1% |

‑0.3% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

3.7% |

3.9% |

4.1% |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)a |

6.2% |

4.0% |

2.0% |

|

Proposition 98 Reserve |

|||

|

Deposit (+) or withdrawal (‑) |

— |

$524 |

‑$38 |

|

Cumulative balance |

— |

524 |

487 |

|

aAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. Note: No maintenance factor obligation is created, paid, or owed over the period. |

|||

Additional Reserve Deposit Required in 2019‑20. As part of the 2019‑20 budget plan, the state made its first deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve ($377 million). The size of this deposit was determined by the difference between the Test 1 and Test 2 funding levels (described in the previous box). Due to the administration’s higher estimate of the minimum guarantee, this difference has increased to $524 million. The Governor’s budget accordingly provides for an additional deposit of $148 million to meet the higher requirement.

Small Withdrawal Required in 2020‑21. Under the Governor’s budget, the minimum guarantee in 2020‑21 is $38 million below the inflation‑adjusted funding level from 2019‑20. The Constitution requires the state to make up this difference by withdrawing a corresponding amount of funding from the Proposition 98 Reserve. This withdrawal reduces the balance in the reserve to $487 million.

Comments

Estimates of General Fund Revenue Are Reasonable... Of all the factors affecting the calculation of the minimum guarantee, estimates of General Fund revenue typically are the most volatile. Relative to the revenue estimates we prepared for The 2020‑21 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, the administration’s estimates are similar in 2018‑19, higher in 2019‑20, and lower in 2020‑21. Across all three years, however, the administration’s estimates are very close to ours—being less than $100 million below our estimates (roughly 0.01 percent of total tax collections). Given these similarities, we think the administration has provided a reasonable starting point for estimating the minimum guarantee.

…But Have Some Downside Risk. Although the administration’s revenue estimates seem reasonable based on current economic conditions, some signs suggest the economy could slow in the coming months. For example, housing markets have been stagnant, job growth is down, and trade activity is decreasing. Though these signs do not necessarily mean a broader economic slowdown is imminent, they do suggest a higher level of risk for state revenue estimates compared to previous budget cycles.

Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive to Changes in Revenue Estimates Over the Period. To the extent estimates of General Fund revenue are higher or lower by May, the minimum guarantee would likewise be affected. In general, the relationship between revenue and the minimum guarantee depends on which Proposition 98 test is operative and whether another test could become operative with higher or lower revenue. Under our outlook, Test 1 is the operative test each year of the budget period. After examining many scenarios, we found that the operative test is unlikely to change in 2019‑20 or 2020‑21. Holding other factors constant, Test 1 would be operative given any level of General Fund revenue. This is due mainly to consistent declines in student attendance over the budget period, a trend that contributes to Test 1 being operative. In Test 1 years, the guarantee increases or decreases about 40 cents for each dollar of higher or lower General Fund revenue.

Changes in Revenue Would Affect Guarantee and Size of Reserve Deposits. Changes in revenue estimates and the minimum guarantee likely would affect the amount of funding the state is required to set aside in the Proposition 98 Reserve. If revenue were to decrease in 2019‑20 or 2020‑21, the state likely would be required to make a smaller deposit (in 2019‑20) or withdraw additional funding (in 2020‑21) from the Proposition 98 Reserve. These changes in the Proposition 98 Reserve level could help insulate school and community college programs from drops in the minimum guarantee—though given the relatively small amount currently in the reserve, this buffer would disappear quickly. On the upside, an increase in revenue would tend to require a larger deposit (in 2019‑20) or smaller withdrawal (in 2020‑21), potentially leaving little of the increase available for new spending. (Our analysis holds all inputs other than revenue constant, though changes in these inputs also could affect the guarantee and the reserve.)

Property Tax Estimates Somewhat Above Our Projections. Estimates of local property tax revenue are the other significant factor affecting the minimum guarantee when Test 1 is operative. Relative to our November outlook, the administration assumes schools and community colleges receive somewhat more property tax revenue from local Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds (accounts that shift funding between schools and other local agencies). It also projects slightly faster growth in assessed property values. On the other hand, the administration has somewhat lower estimates of property tax revenue attributable to former redevelopment agencies (the state dissolved these agencies in 2011‑12). Overall, the administration’s property tax estimates are $671 million above our November estimates over the budget period. The majority of this difference is attributable to the administration’s higher Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds assumptions. To the extent that local property tax revenue differs from the administration’s January estimates, the minimum guarantee would change on a dollar‑for‑dollar basis. (As with General Fund revenue, changes in local property tax revenue also could affect the size of reserve deposits or withdrawals.)

Local Control Funding Formula

In this section, we provide background on LCFF, describe the administration’s proposal and associated projections for LCFF costs, and assess those projections.

Background

State Enacted New School Funding Formula in 2013‑14. Prior to LCFF, the state distributed school funding through a combination of general purpose grants (called “revenue limits”) and more than 40 state categorical programs. Districts could use general purpose grants for any educational purpose but had to spend categorical funding on state‑prescribed activities. In the years leading up to LCFF, policy makers were concerned this system had adverse effects. Notably, the system was characterized by a lack of coordination across programs, a compliance‑based rather than student‑based mindset, a disconnect between funding and student costs, historic funding inequities, and limited local control. In response, the state eliminated most categorical programs in 2013‑14, replacing the previous general purpose grants and program‑specific funding formulas with one new formula.

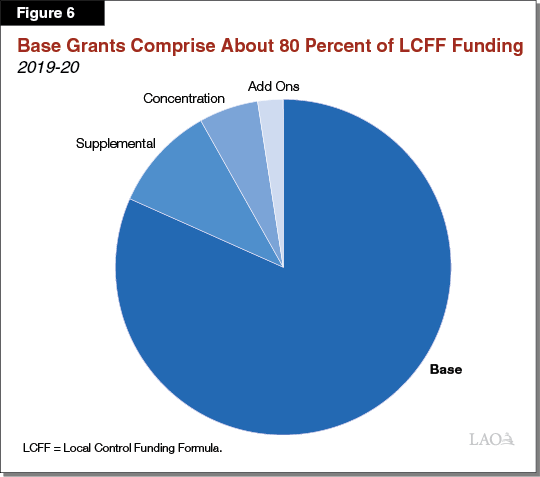

LCFF Has Three Main Components Plus “Add Ons.” LCFF consists of base, supplemental, and concentration grants, as well as several small add ons. Figure 6 shows the share of total LCFF funding attributable to each of these components. We describe each component below.

- Base Grants. The largest component of LCFF is a base grant generated by each student. The number of students is measured using average daily attendance (ADA). Base funding rates differ by grade span, with students in higher grade spans generally generating more funding than those in lower grade spans. The state set per‑student base LCFF funding targets about $500 higher than pre‑recession funding levels adjusted for inflation. Districts may use base funding for any educational purpose.

- Supplemental Grants. For each student who is an English Learner or low income (EL/LI), a district receives a supplemental grant equal to 20 percent of the base grant. A student who is both EL and LI generates the same funding rate as a student who belongs to only one of these groups. Districts must use this funding for the benefit of EL/LI students.

- Concentration Grants. Districts serving a student population of more than 55 percent EL/LI also receive a concentration grant equal to 50 percent of the base grant for each EL/LI student above the 55 percent threshold. Districts also must use this funding for the benefit of EL/LI students.

- Add Ons. The largest add ons are associated with two historical categorical programs—one supporting targeted instructional support and the other supporting home‑to‑school transportation. Though the state no longer requires districts to operate these specific programs, districts continue to receive their 2012‑13 allocations for them.

State Reached LCFF Funding Targets in 2018‑19. In 2013‑14, the state estimated LCFF would cost $18 billion more than the previous system due to its higher per‑student funding targets. Given the size of this additional cost, the state anticipated fully phasing in the rate increases in 2020‑21. Instead, the state slightly surpassed funding targets in 2018‑19.

Since Full Implementation, State Policy Has Been to Adjust LCFF Funding Rates for COLA. Following full implementation, the state adopted a policy of automatically adjusting LCFF per‑student rates for COLA. The specific COLA rate is linked to a national price index designed to reflect the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country—the state and local government price index. This index is developed by the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis (a division of the U.S. Department of Commerce).

State Adopted COLA Cap Last Year. Trailer legislation included in the 2019‑20 budget package added a provision that automatically reduces the COLA rate under certain conditions. Specifically, in years in which growth in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is insufficient to fund an LCFF increase based on the state and local government price index, the LCFF COLA is reduced to fit within the guarantee.

State Estimated to Spend $63 Billion for LCFF in 2019‑20. LCFF is by far the state’s largest education program. With $42.3 billion supported by the state General Fund (and $20.6 billion supported by local property tax revenue), LCFF also is the largest component of the state’s General Fund budget.

Governor’s Proposal

Provides $1.2 Billion Increase to Make Growth and COLA Adjustments. In keeping with recent state practice, the administration’s largest ongoing augmentation is for LCFF. Specifically, the Governor’s budget for 2020‑21 includes a $1.2 billion increase to LCFF, which reflects funding for a projected 2.29 percent COLA, slightly offset by a projected 0.3 percent decline in ADA. The augmentation brings total LCFF funding in 2020‑21 to $64 billion.

Assessment

Projected COLA Rate and Associated Cost Increase for 2020‑21 in Line With Our Estimates. Using the latest data available, we estimate the 2020‑21 COLA rate is 2.14 percent—roughly tracking with the administration’s estimate of 2.29 percent. The estimated rate will change based upon the release of further data updates over the coming months, with the state locking down the rate in late April 2020. Given the relatively modest growth rate in the federal government’s price index, we believe the administration will likely revise its estimate slightly downward as part of the May Revision.

Special Education

Below, we provide background on special education services and financing, describe the Governor’s proposals to reform these aspects of special education, assess these proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Federal Law Requires Schools to Provide Students With Disabilities Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). Special education is instruction designed to meet the unique needs of each child with a disability. As a condition of receiving federal funding, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires schools to identify all students with disabilities and provide them individualized support beginning at the age of three. The specific support provided to each student is detailed in his or her IEP, a legal document developed by the student’s teachers, parents, and school administrators. Support services may include specialized academic instruction, speech therapy, physical therapy, counseling, or behavioral intervention services. In 2018‑19, 11.7 percent of K‑12 students received special education in California.

Schools Must Serve Students With Disabilities in the Most Inclusive Setting. Federal law generally requires districts to serve students with disabilities in the educationally appropriate setting that offers the most opportunity to interact with peers who do not have disabilities. The intent is to provide an “inclusive setting” where students with disabilities are taught alongside their peers in general education classrooms with appropriate services. These students may receive special education services within the general education classroom (for example, having an aide or interpreter work with them one on one) or in separate pull‑out sessions (for example, having a one‑on‑one speech therapy session). Other inclusive models may include instruction designed for students with varying learning needs or co‑teaching, where a special education teacher and general education teacher collaboratively teach a class that includes students with and without disabilities. In 2017‑18, 56 percent of all students with disabilities in California were educated in an inclusive setting—placing California 40th out of 47 states for which data are available.

Special Education Supported by Combination of General Purpose and Categorical Funds. Schools receive billions of dollars each year (mostly from LCFF) to educate all students, including students with disabilities. These funds can be used for any educational purpose but primarily cover general education costs such as teacher compensation. Beyond these general education costs, schools incur additional costs to serve students with disabilities (for example, to provide specialized support and adaptive equipment). To help cover these additional costs, both the state and federal governments provide categorical funding specifically for special education. These fund sources together cover about 40 percent of the additional cost of special education services. Schools cover remaining special education costs with general purpose funding (mostly from LCFF).

Most Funding Allocated to Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs). State law requires school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education—collectively referred to as local education agencies (LEAs)—to participate in a SELPA, which is typically a regional consortium of entities that coordinate special education services. Large districts are allowed to serve as their own SELPAs. Most state and federal special education funding is allocated directly to SELPAs. Each SELPA decides how to allocate its special education categorical funding among its members.

State Provides Most Categorical Funding Based on Overall K‑12 Student Attendance. About 80 percent of state special education funding is allocated by a base rate formula commonly called AB 602 (after its enacting legislation in 1997). The formula distributes funding based on total student attendance rather than a more direct measure of special education costs (for example, the number of students identified for special education or the cost of services provided). The formula uses the greater of the current year’s or prior year’s overall attendance. The AB 602 approach ensures schools have little incentive to overidentify students for special education or serve these students in unnecessarily expensive ways. The federal government also allocates most of its special education funding based on overall student attendance.

AB 602 Base Rates Vary by SELPA. Under AB 602, SELPAs are funded based on overall attendance, but the per‑student rate each SELPA receives varies across the state—ranging from $557 to $960 per student in 2019‑20. As described in the nearby box, this variation was present when the state first shifted to the AB 602 model in the late 1990s. Over the last 20 years, the state has occasionally provided funding augmentations to increase base rates for SELPAs with below average rates.

History of Special Education Funding in California

State Has Overhauled Special Education Funding System Twice Previously. State special education funding has gone through three distinct eras. First, between 1860 and 1980 the state created a patchwork system of special education categorical programs mostly based on specific types of disabilities. Second, in 1980 the state introduced a somewhat simpler funding formula—commonly referred to as J‑50—that was based on the types of services provided. Finally, in 1997 the state introduced an even simpler formula commonly known as AB 602 (Davis) that is based on total student attendance.

Earliest System Had Array of Programs and Major Shortcomings. Starting in 1920, the state gradually developed a complex system for funding special education, eventually encompassing almost a dozen categorical programs. Each program had distinct funding rates, eligibility, and programmatic requirements. The system of categorical programs had various limitations. Most notably, the system encouraged schools to identify students with whichever disability generated the most funding rather than whichever best described their specific challenges.

Second System Funded Based on Specific Services Provided. To address these weaknesses, the state overhauled its special education policies between 1975 and 1980. California introduced a simpler funding system commonly referred to as the J‑50 system (after the associated compliance form). This system was based on three types of special education services: (1) special day classes which only students with disabilities attend, (2) resource teachers who provide pull‑out instructional support for students with disabilities served in general education classrooms, and (3) services provided by specialists such as physical therapy. During this time, California also began requiring all districts to organize into special education local plan areas (SELPAs), which would be responsible for coordinating regional special education services.

Second System Also Proved Complicated and Problematic in Practice. In theory, the J‑50 system simplified special education funding, but in practice, it replaced one set of complications with another. The system established unique funding rates for each SELPA based on a statewide survey of special education costs in 1979‑80. Though these rates closely tracked special education costs the first few years after 1980, the state’s failure to update its cost survey resulted in seemingly arbitrary funding inequities by the mid‑1990s. Most importantly, the J‑50 system encouraged schools to serve students with severe disabilities in special day classes, as the funding generated for serving students with disabilities in general education classrooms was intended only to cover students with relatively mild disabilities.

Current Funding System Intended to Simplify and Address Unequal Funding. The state overhauled the funding system for a second time in 1997 with the passage of AB 602. The state shifted to a formula based on overall student attendance to eliminate the complexity and bad incentives characterizing the J‑50 system. However, in transitioning from the J‑50 system, the state set each SELPA’s per‑student funding rate by using its total funding in the last year under the J‑50 system. Because funding rates varied notably under the J‑50 system, the new rates established under AB 602 also varied notably. In an effort to equalize these rates, the state allocated funding in the late 1990s, early 2000s, and in 2019‑20 to increase rates for SELPAs below the statewide per‑student average. Despite unequal rates, AB 602 largely realized the state’s original goals of simplifying funding and removing inappropriate incentives regarding the provision of services.

State Provides Remaining Categorical Funding Through Various Add Ons. In addition to the base funding from AB 602, SELPAs may receive funding from the state’s many special education categorical programs, as summarized in Figure 7. The distribution and spending restrictions of these categorical funds vary. Three of these categorical programs—mental health services, SELPA administration, and professional development—are allocated to all SELPAs based on overall attendance. The Out‑of‑Home Care program provides funding for students living in licensed group homes or health facilities. Funding for group homes and foster children have been held in place since 2016‑17 due to state reforms that phased out the use of group homes. The remaining programs provide funding based on a variety of other factors, such as the size of the SELPA, the number of students with high‑cost placements or low‑incidence disabilities, or the participation in employment training programs.

Figure 7

California Funds Many Special Education Programs

2019‑20 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Distribution Method |

Spending Restrictions |

Funding |

|

AB 602a |

Overall student attendance. |

Any special education expense. |

$3,412 |

|

Preschool |

Per‑child funding for three‑ and four‑year olds with disabilities (one time). |

None. |

493 |

|

Mental health services |

Overall student attendance. |

Mental health services for students with disabilities. |

386 |

|

Out‑of‑Home Care |

Location and capacity of Licensed Children’s Institutions. |

Any special education expense. |

144 |

|

SELPA administration |

Overall student attendance. |

SELPA‑level services, including data management and required reporting. |

100 |

|

Infants and toddlers |

Number of infants and toddlers with special needs served. |

Early intervention services for infants and toddlers with special needs. |

83 |

|

Workability |

Number of students enrolled in employment training programs. |

Job placement and training for students with disabilities. |

40 |

|

Low‑incidence disabilities |

Number of students who are deaf, hard of hearing, visually impaired, or orthopedically impaired. |

Services and materials for students with qualifying conditions. |

19 |

|

Technical assistance leads |

Competitive. |

Support services. |

10 |

|

Extraordinary cost pools |

Individual student placements. |

Expenses associated with very high‑cost residential or nonpublic school placements. |

6 |

|

Necessary Small SELPAs |

Attendance in SELPAs serving fewer than 15,000 students. |

SELPA‑level services, including coordination, data management, required reporting, and fiscal administration. |

3 |

|

Professional Development |

Overall student attendance. |

Staff development related to special education. |

1 |

|

Total |

$4,697 |

||

|

aSpecial education program named after authorizing legislation—Chapter 854 of 1997 (AB 602, Davis). SELPA = special education local plan area. |

|||

Federal Law Requires “Maintenance of Effort” (MOE) on State and Local Spending. In order to receive federal special education funding, both states and LEAs must spend at least as much on special education each year as they did the preceding year. States and LEAs may choose whether their MOE is calculated on the basis of total special education spending or per‑student spending. By “locking in” increased expenditures, this requirement offers an additional incentive for the state and LEAs to contain special education costs.

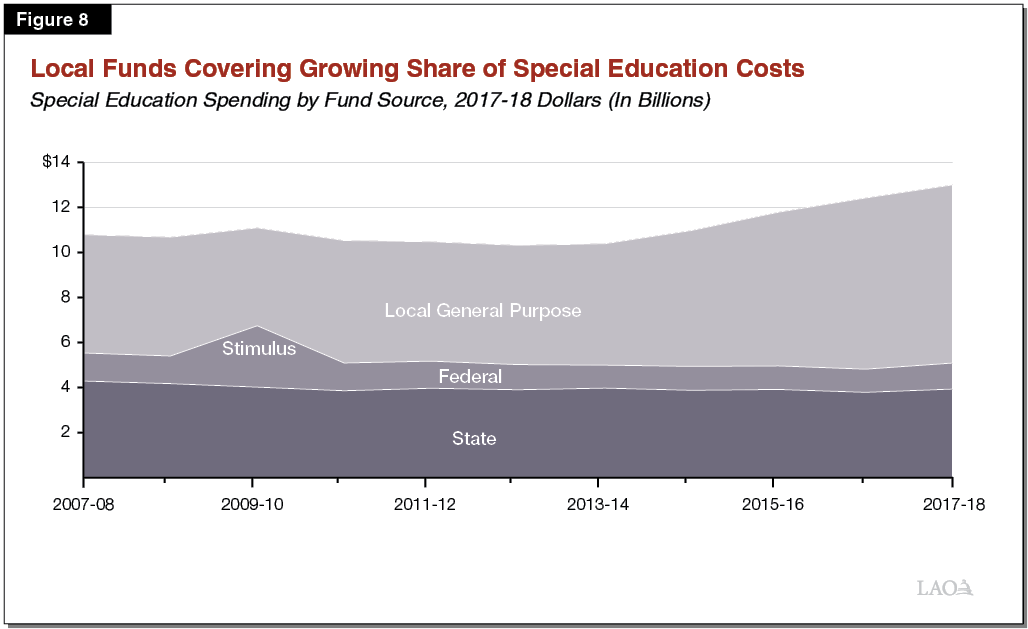

Special Education Expenditures Have Increased Faster Than Associated Funding. Figure 8 shows inflation‑adjusted special education expenditures by fund source between 2007‑08 and 2017‑18. During this ten‑year period, total state and federal special education funding declined (in inflation‑adjusted terms) due to the drop in overall student attendance. However, total special education expenditures increased, largely driven by a growing number of students with relatively severe disabilities requiring more intensive services. Most notably, the share of students with autism has increased from 1 in 600 in 1997‑98 to 1 in 50 in 2017‑18. Expenditures also have increased as a result of schools increasing staff salaries and being required to make larger pension contributions on behalf of their employees. As a result, local general purpose funding has been covering an increasing share of special education expenditures, rising from about 45 percent ten years ago to about 60 percent today.

Special Education Expenditures Vary by Region. In per‑student terms, special education expenditures vary notably among SELPAs. We estimate SELPAs spent an average of about $2,000 per student in 2017‑18 (spreading costs across all students in the region). Per‑student spending among SELPAs ranged from about $600 to more than $4,000. Special education expenditures vary by region for at least three reasons. First, the overall incidence of students with disabilities varies across the state. Second, even SELPAs serving similar proportions of students with disabilities may differ in the intensity of their services. Third, the cost of providing specific special education services varies by region, largely because of differences in the compensation packages that LEAs provide teachers and specialists.

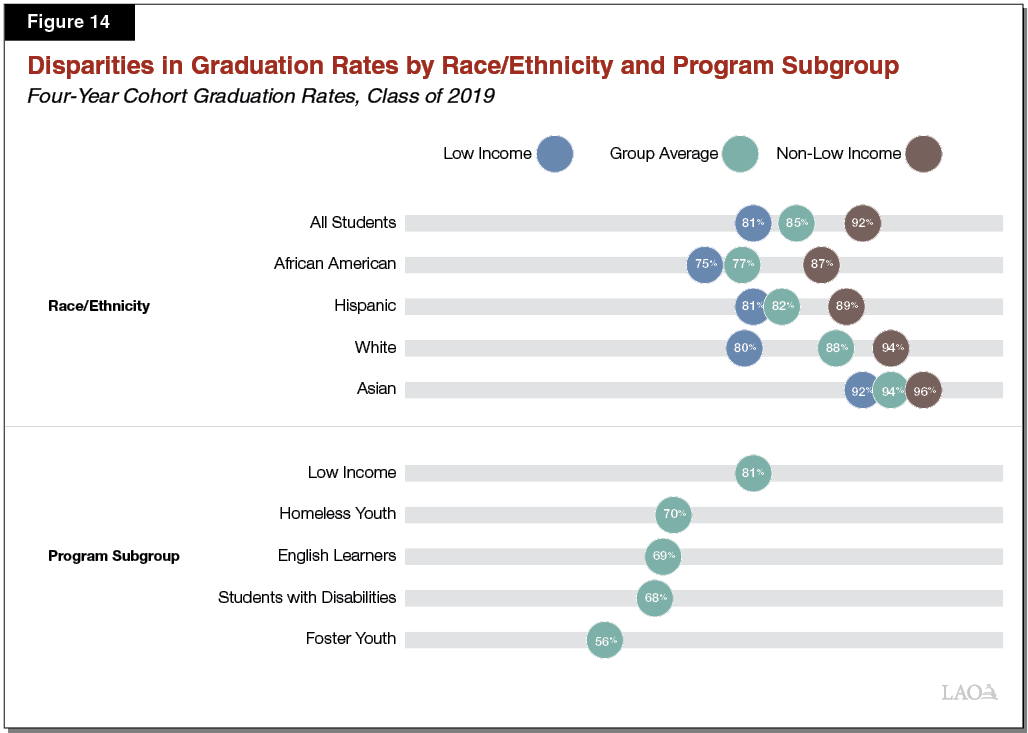

Students With Disabilities Tend to Have Poorer Outcomes Than Other Students. Students with disabilities perform worse than students without disabilities across several measures. Based upon the most recent data, students with disabilities had low scores on standardized tests of reading and math—scoring as a group at the 18th percentile of all test takers. Students with disabilities also have notably lower graduation rates compared to other student groups. In 2017‑18, the four‑year graduation rate for students with disabilities was 65 percent, compared to 83 percent of students statewide. Some students with disabilities, however, just take longer to graduate. Of the students with disabilities exiting high school in 2017‑18, 76 percent left with a high school diploma. Of the remaining students, 13.6 percent dropped out, 3.4 percent aged out (reaching age 22), and 7 percent received an alternative certification called a certificate of completion. (Students can receive a certificate of completion if their IEP team determines they are unlikely to meet all requirements for high school graduation, but can meet an alternative set of requirements developed by the IEP team.)

Current‑Year Budget Included $645 Million One‑Time Funding for Preschool and Low‑Funded SELPAs. The 2019‑20 budget provided $493 million one‑time funding to districts based on the number of preschool‑aged children with disabilities they serve—$9,010 per child. Although districts are required to provide special education services for this age group, the current‑year budget is the first time the state has provided funding for this purpose. Districts were not required to use these funds for additional services. Thus, funds likely will be used to cover the costs of existing preschool services. The 2019‑20 budget also included $153 million one‑time funding to increase AB 602 rates for SELPAs funded below the statewide average of $557 per student.

Current‑Year Augmentations Made Contingent on Future Special Education Reforms. The 2019‑20 budget package also included language specifying that the $645 million in augmentations would only be ongoing if the Legislature makes statutory changes in the 2020‑21 budget designed to improve the academic outcomes of students with disabilities. The specific reforms are to be determined collaboratively by the Legislature and the administration but may include a reconsideration of the role of SELPAs, an expansion of inclusive instructional practices, support for addressing disproportionate identification and placement of certain student subgroups, and review of special education funding allocations.

Governor’s Proposals

Proposes a Multi‑Phased Approach Aimed at Improving Special Education. Given the language in the 2019‑20 budget prompting special education reform, the administration engaged with various stakeholders in the summer and fall of 2019. The administration identified several challenges informed by these discussions, including growing student mental health and social‑emotional needs, teachers not prepared to adapt instruction to students with diverse needs, shortages in special education teachers and specialists, and the lack of clear and consistent messaging from the state to promote inclusive practices that improve outcomes for all students. To address these issues, the Governor proposes to make reforms in special education financing and other areas over a multiyear period.

First Phase Makes $645 Million Augmentation From 2019‑20 Ongoing to Modify Base Formula. The Governor proposes to increase the base rate for most SELPAs to $660 per student. To fund the base rate increase, the Governor proposes to make ongoing the $645 million augmentation provided in 2019‑20. SELPAs that currently have higher rates than the proposed new base rate would be held harmless. The Governor also proposes to modify the base formula to use a three‑year rolling average of student attendance, rather than the greater of the current year or prior year. The average would be calculated for each LEA, but funding would continue to be allocated to SELPAs.

Freezes Categorical Funding and SELPA Membership. In anticipation of future changes to special education funding, the Governor’s budget proposes to freeze allocations for most special education categorical programs at 2019‑20 levels, adjusted for cost of living. In addition, the Governor proposes to prohibit LEAs from changing SELPAs through 2023‑24.

Future Phases to Be Informed by a Privately Funded Study. In the fall of 2019, a study of special education funding in California was commissioned using private foundation funding to potentially inform future changes to the special education funding formula. The scope of the study was developed with input from the administration, the State Board of Education, and the California Department of Education (CDE). Our understanding is the study is expected to recommend a new funding model aimed at addressing variation in student needs and costs, promoting inclusive practices, and encouraging early intervention and identification of students with disabilities. The study is expected to be completed within the next year.

Proposes $1.1 Million for a Governance Study and Two Workgroups to Inform Future Phases. The Governor’s budget provides $500,000 on a one‑time basis to fund a study on special education governance and accountability. The study would provide recommendations on (1) improving delivery of special education services, (2) improving student outcomes, (3) ensuring equitable distributions of services to LEAs, and (4) identifying strategies and challenges for funding and services under the current and recommended models. The findings of the study would be reported to the Legislature by October 1, 2021. The budget also includes a combined $600,000 one time to convene two workgroups. Of this amount, $350,000 is for a workgroup to develop a standardized IEP template and consider the feasibility of a statewide IEP reporting system. The remaining $250,000 is for a workgroup to develop alternate pathways for students with disabilities to receive a high school diploma. Both workgroups would include the Department of Rehabilitation, the Department of Developmental Services, LEAs, SELPAs, legislative staff, and relevant experts. The time frame and the of the workgroups would be similar to that of the governance study.

Includes $250 Million in One‑Time Funding for Preschool Services. The Governor’s budget includes $250 million in one‑time funding to be allocated to districts based on the number of preschool‑aged children with disabilities served by the district. In contrast to the preschool funds provided in 2019‑20, the Governor intends this funding to increase or improve program services.

Provides $4 Million One Time to Create the California Dyslexia Initiative. The Governor proposes to designate a county office of education (COE) to promote best practices regarding the treatment of dyslexia across the state. The COE would find effective models that identify and support students with dyslexia and other specific learning disabilities, create professional development on effective instruction for these students, and host a statewide conference by the end of 2020 to disseminate relevant information and resources. The COE would lead the initiative in partnership with a designated university.

Assessment

Proposal Generally Aligned With Original Legislative Intent. By reducing variations in SELPA base rates, the Governor’s proposal addresses special education funding inequities that have persisted for decades. Moreover, the proposal is consistent with the original intent of AB 602 and our office’s past recommendations.

Three‑Year Average Would Smooth Funding Changes for Districts With Declining Attendance. Given statewide student attendance has been declining since 2013‑14 and is projected to continue declining over the next decade, shifting to a three‑year average would help smooth the associated drops in special education base funding for the majority of districts. In contrast, for the smaller share of districts that are growing, a rolling average would result in annual funding increases somewhat smaller than their growth in attendance.

Unclear How Proposed Reforms Address Key Challenges in Special Education. In explaining the rationale for its proposal, the administration cites several key challenges in special education, such as teachers not being fully prepared for inclusive classrooms and an increasing need for mental health and social‑emotional support for students. However, the nexus between these challenges and the special education funding model remains unclear. The AB 602 base formula provides schools with broad flexibility to use funding in ways that align with the needs of their students, including promoting inclusive classrooms and providing additional student services. Similarly, we do not see a clear connection between the current special education governance system and the challenges cited by the administration.

Current Approach to Studying Problem Limits Legislative Input. Many of the key challenges cited by the administration align with issues the Legislature has deemed key priorities. However, the privately funded study—which may ultimately inform future proposals from the administration—was initiated, funded, and developed outside of the legislative process. This approach leaves little room to ensure the Legislature’s concerns are incorporated in the study. Although the Legislature will be able to review any new funding model that the administration proposes in the future, this provides limited time for the administration to then directly address any concerns that the Legislature may have about the proposed model. For instance, the privately funded study is expected to make recommendations to address the higher costs of serving students with severe disabilities. Providing more funding to LEAs for children with more severe disabilities could address this concern, but also could create incentives for LEAs to overidentify students with disabilities. The Legislature would need sufficient time to evaluate these considerations.

Base Funding Does Not Include Count of Preschool‑Aged Children. Although the federal government requires districts to begin providing special education to children with disabilities on their third birthdays, the AB 602 base formula does not include student attendance for this age group. This is primarily because most children in this age group do not attend school and the state does not collect data on the number of preschoolers who live within each school district’s attendance boundary. As a result, the state provides no funding to account for the costs associated with serving these children. Districts cover related costs with a combination of federal funding and general purpose funding.

One‑Time Preschool Funding Sends Confusing Message to Districts. The administration intends for the one‑time preschool funding to be used to increase or improve services for children. Based on our conversations with various special education stakeholders, effectively increasing or improving services typically requires ongoing spending increases—particularly for hiring additional staff. However, given the one‑time nature of these funds, schools are unlikely to hire additional staff to support these new services. Instead, the funding likely will be used for one‑time activities, such as professional development or technology purchases. Districts are also discouraged from using this funding to provide additional IEP‑related services, as this would raise their local MOE.

Recommendations

Adopt Governor’s General Approach to Modifying Base Funding Formula. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s general approach of using the $645 million augmentation provided last year to develop new AB 602 base rates. The approach is aligned with the original intent behind AB 602 to eliminate historical variations in base rates. We also recommend adopting the proposed three‑year average of attendance to calculate base funding. This will smooth drops in funding due to declining student attendance in many districts across the state.

Use One‑Time Preschool Funding for an Ongoing Base Increase, Incorporate Preschoolers Into the Base. We recommend the Legislature make the proposed $250 million for one‑time preschool funding, instead, an ongoing base augmentation to fund the addition of preschool‑aged children into the base formula. Expanding the base formula to include preschool‑aged children would allow the state to recognize local costs associated with serving this age group. To address the lack of preschool attendance data, we recommend modifying the base formula to double‑count kindergarten attendance for LEAs that provide preschool, effectively using kindergarten attendance as a proxy for preschool attendance.

Fund Studies and Workgroups Based on Legislative Priority. Considering the administration plans on addressing special education issues over a multiyear period, the Legislature may want to think carefully about what issues it would like to ensure are addressed. To the extent that additional research or stakeholder input may be helpful, the Legislature could consider funding other studies and/or workgroups this year to help inform future changes to special education. Below we describe two options the Legislature could consider:

- Reforms to Special Education Categorical Programs. The Legislature could fund a study or workgroup that makes recommendations for simplifying or updating the state’s special education categorical programs. Many of these programs merit a careful review to ensure they are an effective way to distribute funding. Funding for the Out‑of‑Home Care program has been partially frozen since 2016‑17 because its allocation formula is no longer applicable. Some programs, such as employment training and funding for infant and toddlers, were first established in the 1980s and are only allocated to certain LEAs. The privately funded study may examine some of these issues, but a narrower, specific study might provide the Legislature with more concrete options for reforming the current model.