LAO Contacts

- Lisa Qing

- California Community Colleges:

- Apprenticeships, Work-Based Learning,

- Food Pantries, and Facilities

- Paul Steenhausen

- California Community Colleges: Apportionments, Faculty Issues, and Zero-Textbook-Cost Degrees

- California State University

- Extended Education

- Jason Constantouros

- University of California

February 20, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget

Higher Education Analysis

- Introduction

- California Community Colleges

- California State University

- University of California

- Extended Education

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s higher education budget proposals. Similar to last year, these proposals are wide ranging—including large base increases; targeted increases for apprenticeship programs and food pantries; one‑time initiatives relating to extended education programs, work‑based learning, faculty diversity, and animal shelters; and many facility projects. Below, we highlight some key takeaways from our analysis.

California Community Colleges

Bulk of Proposed Apportionment Increase Needed to Cover Higher Pension Costs. The largest ongoing spending proposal for the California Community Colleges (CCC) is $167 million to cover a 2.29 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for apportionments. Augmenting apportionments can help community colleges cover employee salary increases, health care premiums, and pension costs. We estimate that districts’ pension costs alone are likely to increase by about $120 million in 2020‑21. Under the Governor’s budget, districts would have less than $50 million remaining. By early May, the Legislature will know the final COLA rate and have better information on state revenues, which will affect the amount of state funding available for the colleges. If additional funding becomes available, the Legislature may wish to provide a larger apportionment increase.

Systemwide CCC Enrollment Has Plateaued. The Governor’s budget includes $32 million for 0.5 percent CCC enrollment growth (equating to about 7,800 additional full‑time equivalent students). The proposed growth rate is about the same as the growth used by districts in the past couple of years. Though a few areas of the state (notably, the Central Valley and Inland Empire) continue to grow, other areas (including the Bay Area and Los Angeles/Orange County region) are seeing declines. By May, the Legislature will have better data to help it set the 2020‑21 CCC enrollment target.

Universities

Governor Leaves Little Assurance Legislative Priorities Will Be Addressed. The largest ongoing spending proposals for the universities are base increases of $199 million for the California State University (CSU) and $169 million for the University of California (UC). The Governor’s budget does not link these proposed augmentations with clear, specific state spending priorities. This budgetary approach is fraught with problems—leaving the Legislature not knowing how CSU and UC will spend the proposed augmentations (including how many students they will serve), whether the universities’ budget priorities will be aligned with legislative interests, or whether the proposed augmentations are too little or too much to meet state objectives.

Tuition Increases Are One Way to Expand Budget Capacity. Both CSU and UC have been contemplating possible tuition increases. One of the options being considered would raise tuition by 3 percent, consistent with inflation. A 3 percent increase would translate into a full‑time, resident undergraduate student at CSU and UC paying about $175 and $350 more per year, respectively. Financially needy students would not pay the increase, as financial aid covers full tuition. The state also provides partial tuition coverage for middle‑income students who do not otherwise qualify for need‑based aid.

Recommend the Legislature Set Its Budget Priorities for the Universities. We crafted illustrative budget plans so the Legislature could see how much spending can be accommodated with and without a tuition increase. Under the illustrative CSU and UC plans, the state would budget for basic cost pressures, including rising health care and pension costs. The plans would then assume 3 percent salary increases for faculty and staff. After covering these costs, the “no tuition increase” plan at CSU would leave $12 million for other legislative priorities (such as enrollment growth and programmatic expansions). At UC, the no tuition increase plan ends up spending more than the amount proposed by the Governor. By comparison, the “tuition increase” plan would leave $42 million available at CSU and $50 million available at UC for funding other legislative priorities. (Another way to increase budget capacity is to consider using CSU and UC reserves for certain one‑time priorities, such as deferred maintenance or seismic safety studies.)

Multiple Factors to Consider in Deciding Whether to Grow Enrollment at CSU and UC. The challenge for the Legislature is that the factors do not all point in the same direction. On the one hand, some factors suggest more enrollment is not warranted. The number of public high school graduates in the state is projected to decrease by 0.5 percent in 2019‑20. In addition, CSU currently is not on track to meet its 2019‑20 enrollment target. Moreover, recent studies show that both CSU and UC are drawing from beyond their traditional freshman eligibility pools. On the other hand, some factors suggest growth is merited. Most notably, both CSU and UC are rejecting many eligible applicants at high‑demand, impacted campuses. More enrollment growth could help more eligible applicants attend their campus of choice.

Crosscutting Issues

Better Understanding Root Problems Is Critical Before Increasing Spending. Some of the Governor’s higher education proposals seem to have laudable goals, but the associated spending proposals are not well justified. For the initiatives involving work‑based learning, extended education, and faculty fellowships, the Governor has not clearly identified the root problems or explained how his proposals would remedy those problems. The Governor is also missing opportunities, such as with extended education and the California Apprenticeship Initiative, to learn from recent expansion efforts—knowing little more today than a year or two ago about what is working. Without a better understanding of root issues, the Legislature could end up using money ineffectively.

Important for Legislature to Weigh Its One‑Time Priorities. Each public higher education segment faces several billions of dollars in existing unfunded liabilities related to pensions, retiree health care, maintenance backlogs, and seismic renovation backlogs. Providing one‑time funding to address these existing liabilities provides clear, known benefits—helping to reduce future costs and risks while improving fiscal health. In contrast, funding many small, new, one‑time initiatives—such as the Governor’s CCC proposal for work‑based learning and the UC animal shelter outreach initiative—does little to advance progress toward addressing existing liabilities. Given these trade‑offs, the Legislature will likely want to weigh its one‑time options carefully and select the options that have the highest returns.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s major higher education proposals. This report has sections covering the California Community Colleges (CCC), California State University (CSU), University of California (UC), and extended education. The final section of this report provides a summary of our recommendations. In The 2020‑21 Budget: Medical Education Analysis, we analyze the Governor’s proposals to expand the UC Riverside School of Medicine and the UC San Francisco Fresno branch campus. In forthcoming analyses, we will cover the California Student Aid Commission and Hastings College of the Law as well as a few crosscutting education proposals, including the Fresno K‑16 educational pathways initiative. For tables providing additional higher education budget detail, see the “EdBudget” section of our website. For background on the state’s higher education system (including its students, staffing, campuses, funding, outcomes, and facilities), see California’s Education System: A 2019 Guide.

California Community Colleges

In this part of the report, we provide an overview of the CCC budget, then analyze most of the Governor’s CCC budget proposals. Specifically, we analyze his proposals for apportionments, apprenticeship programs, work‑based learning, food pantries, faculty diversity, part‑time faculty office hours, zero‑textbook‑cost degrees, and facilities. In subsequent online posts, we plan to analyze the Governor’s crosscutting proposals on (1) instructional materials for dual enrollment students and (2) immigrant legal services for students and staff.

Overview

Total CCC Budget Reaches $15.7 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. Almost $10 billion of the CCC budget comes from Proposition 98 funds (Figure 1). In addition, the state provides CCC with non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain purposes. Most notably, non‑Proposition 98 funds cover debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC teacher retirement costs, and Chancellor’s Office operations. Altogether, state Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98 funding comprises about two‑thirds of CCC funding. The remaining one‑third of CCC funding comes primarily from student enrollment fees, other student fees (such as nonresident tuition, parking fees, and health services fees), and various local sources, including community service programs and “excess” local property tax revenue. (The nearby box on provides more information on the community college districts that receive some of their funding from excess property tax revenue.)

Figure 1

California Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions, Except Funding Per Student)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$6,117 |

$6,223 |

$6,372 |

$149 |

2.4% |

|

Local property tax |

3,077 |

3,254 |

3,435 |

181 |

5.6 |

|

Subtotals |

($9,195) |

($9,477) |

($9,807) |

($330) |

(3.5%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Funda |

$893 |

$645 |

$703 |

$58 |

9.0% |

|

Lottery |

245 |

246 |

246 |

—b |

‑0.2 |

|

Special funds |

83 |

99 |

95 |

‑5 |

‑4.7 |

|

Subtotals |

($1,221) |

($991) |

($1,044) |

($53) |

(5.4%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$464 |

$464 |

$466 |

$2 |

0.5% |

|

Other local revenuec |

4,003 |

4,026 |

4,047 |

21 |

0.5 |

|

Subtotals |

($4,467) |

($4,489) |

($4,513) |

($23) |

(0.5%) |

|

Federal |

$288 |

$288 |

$288 |

— |

0.0% |

|

Totals |

$15,171 |

$15,245 |

$15,651 |

$406 |

2.7% |

|

Full‑Time Equivalent (FTE) Students |

1,123,315 |

1,123,753 |

1,119,421 |

‑4,332 |

‑0.4%d |

|

Proposition 98 Funding Per FTE Student |

$8,185 |

$8,433 |

$8,761 |

$328 |

3.9% |

|

Total Funding Per FTE Student |

$13,505 |

$13,566 |

$13,982 |

$415 |

3.1% |

|

aIncludes $405 million in additional retirement payments authorized in the 2019‑20 budget package ($315 million in 2018‑19 and $89 million in 2019‑20). bProjected to decline by $379,000. cPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. Administration assumes local debt‑service payments remain flat throughout the period. dReflects the net of the Governor’s proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. |

|||||

Excess Tax Districts

System Could Soon Have Eighth “Excess Tax” Community College District. Each year, the state excludes some property tax revenue from calculations of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Specifically, some community college districts (CCD) receive local property tax revenue in excess of their total allotment under the state’s community college funding formula. The state does not provide General Fund apportionments to these college districts, but it allows the districts to retain their excess property tax revenue. Currently, the state has seven college districts with excess property tax revenue (up from three colleges in 2010‑11). The figure lists these districts, along with the amount of property tax revenue each receives on top of its state formula allotment. Based on our property tax projections, we expect Sierra CCD (in Rocklin) to become an excess tax district over the next year or two.

Seven Community College Districts

Have “Excess” Tax Revenue

Administration’s Estimates for 2020‑21 (In Millions)

|

“Excess” Tax Amount |

|

|

South Orange CCD |

$115 |

|

San Mateo CCD |

72 |

|

West Valley‑Mission CCD |

69 |

|

MiraCosta CCD |

54 |

|

San Jose‑Evergreen CCD |

44 |

|

Marin CCD |

37 |

|

Napa CCD |

3 |

|

Total |

$394 |

|

CCD = Community College District. |

|

Governor’s Budget Contains More Than a Dozen CCC Proposition 98 Spending Proposals. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor has many CCC spending proposals. The Governor’s new ongoing spending proposals total $296 million, whereas his one‑time initiatives total $93 million. (Of the new one‑time spending, $62.6 million is scored to 2020‑21, $28.6 million is scored to 2019‑20, and $1.5 million is scored to 2018‑19.) Not reflected in the figure is a proposal to consolidate some funding currently provided for system support. The nearby box on explains this proposal.

Figure 2

Governor Has Many Proposition 98 CCC Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

Amount |

|

New Ongoing Spending |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (2.29 percent) |

$167 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

32 |

|

Apprenticeship instructional hours |

28 |

|

COLA for select categorical programsa |

22 |

|

California Apprenticeship Initiative |

15 |

|

Food pantries |

11 |

|

Immigrant legal services |

10 |

|

Dreamer resource liaisons |

6 |

|

Instructional materials for dual enrollment students |

5 |

|

Total |

$296 |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Apprenticeship instruction hours (2019‑20) |

$20 |

|

Work‑based learning initiative |

20 |

|

Deferred maintenance |

17b |

|

Faculty diversity fellowships |

15 |

|

Part‑time faculty office hours |

10 |

|

Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degrees |

10 |

|

Total |

$93 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and mandates block grant. bOf this amount, $8.1 million is scored to 2020‑21, $7.6 million is scored to 2019‑20, and $1.5 million is scored to 2018‑19. COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment. |

|

CCC System Support

Governor Proposes Consolidated Approach to Systemwide Activities. For many years, the state has funded certain support services that are intended to benefit all colleges across the CCC system. These services currently include systemwide technology infrastructure, college program improvement expertise, administration of certain workforce and student support programs, and a unified financial aid marketing campaign. As the figure below shows, the Governor proposes to redirect a total of $125 million (ongoing Proposition 98 funds) from eight of these existing CCC programs into a consolidated System Support Program, with no net change in associated funding. Proposed trailer bill language would require the CCC Board of Governors to approve an expenditure plan for the $125 million by September 30 of each fiscal year and report expenditures to the Department of Finance and Legislature by September 30 of the following year.

New Approach Intended to Foster Greater Coherence and Coordination. The proposal is intended to improve the Chancellor’s Office’s ability to coordinate activities across several categorical programs and respond to changing systemwide needs more quickly and effectively. We think the proposed consolidation has the potential to achieve these objectives. Whereas the current approach attaches separate pots of money to narrow sets of activities, the proposed approach gives the Chancellor’s Office greater flexibility to pool funding to meet strategic systemwide goals. We have no major concerns with this proposal and recommend the Legislature adopt it.

Governor Proposes Creating Consolidated

System Support Program

Funds Proposed for Redirection (In Millions)

|

Community College Program |

Amount |

|

Telecommunications and technology services |

$41.9 |

|

Institutional effectiveness initiative |

27.5 |

|

Online education initiative |

20.0 |

|

Student Equity and Achievement Program |

16.6 |

|

Strong Workforce Program |

12.4 |

|

Financial aid administration |

5.3 |

|

NextUp foster youth program |

0.8 |

|

Transfer education and articulation |

0.7 |

|

Total |

$125.2 |

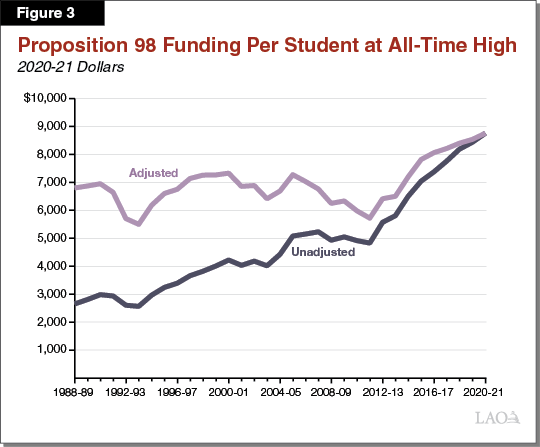

Proposition 98 Funding Per Community College Student Is at an All‑Time High. Inflation‑adjusted per‑student funding at the community colleges reached a new all‑time high in 2019‑20—marking the fifth consecutive year of new all‑time highs (Figure 3). In 2020‑21, this trend is expected to continue. Proposition 98 funding per full‑time equivalent (FTE) student is projected to be $8,761 in 2020‑21, an increase of $328 (3.9 percent) from 2019‑20. In inflation‑adjusted terms, per‑student funding in 2020‑21 is projected to be nearly $2,000 higher than in 1988‑89 (the year voters approved Proposition 98).

No Proposed Change to Enrollment Fee. State law currently sets the CCC enrollment fee at $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). The Governor proposes no increase in the fee, which has remained flat since summer 2012. The state waives the enrollment fee for about half of students, accounting for two‑thirds of credit units taken at the community colleges. Statewide, student enrollment fees account for about 5 percent of core funding, with the state General Fund and local property tax revenue accounting for the rest.

Apportionments

In this section, we provide background on community college apportionment funding, describe the Governor’s proposals to increase college apportionments for inflation and enrollment growth, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Adopted New Apportionment Funding Formula in 2018‑19. For many years, the state has allocated general purpose funding to community colleges using an apportionment formula. Prior to 2018‑19, the state based apportionment funding for credit instruction almost entirely on enrollment. In 2018‑19, the state changed the credit‑based apportionment formula to include three main components—a base allocation linked to enrollment, a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. We describe these components in more detail in the next three paragraphs. For each of the three components, the state set new per‑student funding rates. The rates are to receive a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) each year. The new formula—formally known as the Student Centered Funding Formula—does not apply to incarcerated students or high school students in credit programs. It also does not apply to students in noncredit programs. Apportionments for these students remain based entirely on enrollment.

Base Allocation. As with the prior apportionment formula, the base allocation of the Student Centered Funding Formula gives a district certain amounts for each of its colleges and state‑approved centers. On top of that allotment, it gives a district funding for each credit FTE student (about $4,000 in 2019‑20). Calculating a district’s FTE student count involves several somewhat complicated steps, but basically the count is based on a three‑year rolling average. The rolling average takes into account a district’s current‑year FTE count and counts for the prior two years. As discussed later, enrollment growth for the budget year is funded separately.

Supplemental Allocation. The Student Centered Funding Formula provides an additional amount (about $950 in 2019‑20) for every student who receives a Pell Grant, receives a need‑based fee waiver, or is undocumented and qualifies for resident tuition. Student counts are “duplicated,” such that districts receive twice as much supplemental funding (about $1,900 in 2019‑20) for a student who is included in two of these categories (for example, receiving both a Pell Grant and a need‑based fee waiver). The allocation is based on student counts from the prior year. An oversight committee recently made a recommendation to add a new factor to the supplemental allocation, as described in the box below.

Oversight Committee Recommendation

Committee Charged With Studying Possible Modifications to Funding Formula. The statute that created the Student Centered Funding Formula also established a 12‑member oversight committee, with the Assembly, Senate, and Governor each responsible for choosing four members. The committee is tasked with reviewing and evaluating initial implementation of the new formula. It also is tasked with exploring certain changes to the formula over the next few years. By January 1, 2020, the committee was required to make recommendations to the Legislature and Governor on three possible changes to the supplemental allocation component of the formula. Specifically, the committee was to make recommendations whether this component of the formula should consider first‑generation college status, incoming students’ level of academic proficiency, and regional cost of living. By June 30, 2021, the committee is to make another set of recommendations, including whether to add noncredit instruction to the base and supplement allocation components of the formula. The committee is scheduled to sunset on January 1, 2022.

Committee Recommends Adding First‑Generation College Status to Formula. In December 2019, the committee issued its first required report. The committee recommends that counts of first‑generation college students be added to the supplemental allocation beginning in 2021‑22. The committee recommended defining “first generation” as a student whose parents do not hold a bachelor’s degree. (Currently, community colleges define first generation as a student whose parents do not hold an associate degree or higher.) The oversight committee recommended using an unduplicated count of first‑generation and low‑income students. (This means a student who is both a first‑generation college goer and low income would be counted as one for purposes of generating supplemental funding.) Oversight committee members ultimately rejected or could not agree on the issues of adding academic proficiency and taking into account regional cost of living when identifying low‑income students.

Student Success Allocation. The formula also provides additional funding for each student achieving specified outcomes, including obtaining various degrees and certificates, completing transfer‑level math and English within the student’s first year, and obtaining a regional living wage within a year of completing community college. (For example, a district generates about $2,200 in 2019‑20 for each of its students receiving an associate degree for transfer.) Districts receive higher funding rates for the outcomes of students who receive a Pell Grant or need‑based fee waiver, with somewhat greater rates for the outcomes of Pell Grant recipients. (For example, a district generates about $3,100 in 2019‑20 for each Pell Grant recipient and about $2,800 for each need‑based fee waiver recipient receiving an associate degree for transfer.) Beginning in 2019‑20, the student success component of the formula is based on a three‑year rolling average of student outcomes data and only the highest award earned by a student is considered. (In 2018‑19, the formula was based on only one year of student outcome data and all degrees and certificates earned by a student were considered.)

Statute Weights the Three Components of the Formula. Of total apportionment funding, the base allocation accounts for 70 percent, the supplemental allocation accounts for 20 percent, and the student success allocation accounts for 10 percent. (The 2019‑20 budget package rescinded a previously scheduled increase in the student success share of the formula. The original 2018‑19 legislation had scheduled to increase the student success share of the formula from 10 to 20 percent by 2020‑21, with a corresponding reduction to the share based on enrollment.)

New Formula Insulates Districts From Funding Losses During Transition. The new formula includes “hold harmless” provisions for community college districts that would have received more funding under the former apportionment formula than the new formula. Through 2021‑22, these community college districts are to receive their total apportionment in 2017‑18 adjusted for COLA each year of the period. Beginning in 2022‑23, districts are to receive no less than the per‑student rate they generated in 2017‑18 under the former apportionment formula multiplied by their current FTE student count. In 2019‑20, 32 districts are being held harmless, and the state is providing about $150 million in total hold harmless funding (meaning funding above what the districts would generate based upon the Student Centered Funding Formula).

Chancellor’s Office Is Reporting a Very Small Shortfall in 2018‑19 Apportionment Funding. Throughout 2018‑19, the Chancellor’s Office estimated a large shortfall (more than $100 million as of June 2019) in apportionment funding. This shortfall was thought to have occurred due to a combination of higher‑than‑expected costs of the new formula and lower‑than‑assumed local property tax revenue. Based on updated enrollment and revenue data for 2018‑19, the Chancellor’s Office now estimates a nearly negligible shortfall for that year (less than $4 million systemwide).

State Allocates Enrollment Growth Separately. Enrollment growth funding is provided on top of the funding derived from all the other components of the apportionment formula. Statute does not specify how the state is to go about determining how much growth funding to provide. Historically, the state considers several factors, including changes in the adult population, the unemployment rate, the prior‑year enrollment trend, and the condition of the General Fund.

Chancellor’s Office Uses Statutory Formula to Allocate Enrollment Growth Funding. When the state provides enrollment growth funding, the Chancellor’s Office distributes the funding among college districts using a certain allocation formula. The allocation formula takes into account three factors at each district: (1) its share of the state’s adult population without a college degree, (2) its share of unemployed adults, and (3) its share of households with income below the federal poverty line. The Chancellor’s Office compares these measures of need with the district’s current share of community college enrollment, then allocates funds to reduce gaps between the two. In an effort to balance need, demand, capacity, and equity, the model also considers current enrollment and recent enrollment growth patterns. The formula is designed to direct a larger share of enrollment growth to high‑need districts.

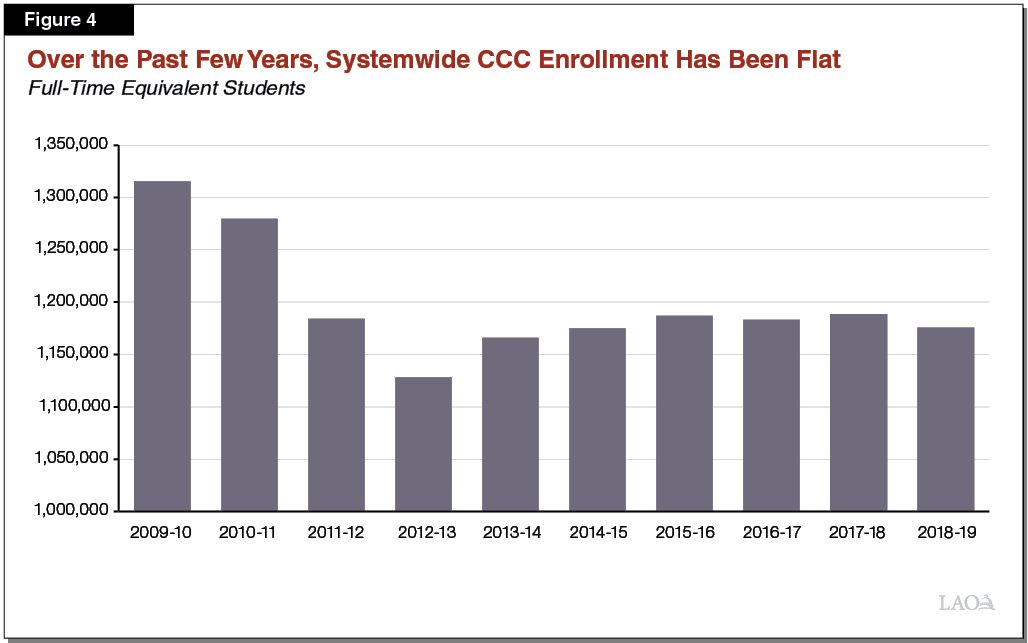

Enrollment Trends

Systemwide CCC Enrollment Has Plateaued. Systemwide community college enrollment dropped during the Great Recession as the state reduced funding for the colleges. As state funding recovered during the early years of the economic expansion (2012‑13 through 2015‑16), systemwide enrollment increased. As the period of economic expansion has lingered and unemployment has remained at or near record lows, systemwide CCC enrollment has plateaued (Figure 4). Systemwide enrollment has remained flat the past few years even with strong growth in state funding.

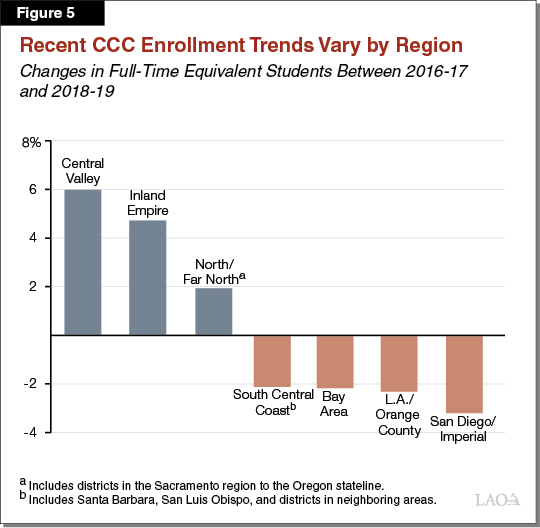

Enrollment Trends Around the State Are Mixed. Enrollment trends vary by region (Figure 5). A few areas of the state (notably the Central Valley and Inland Empire) are experiencing growth. In several other areas of the state (including the Bay Area and Los Angeles/Orange County region), CCC enrollment has declined over the past three years. These regional differences likely are the result of several factors, including underlying demographics, economic conditions, and changes in the apportionment formula.

Proposals

Governor Funds COLA and Enrollment Growth. The Governor’s budget includes $167 million to cover a 2.29 percent COLA for apportionments. In addition, the budget includes $32 million for 0.5 percent enrollment growth (equating to about 7,800 additional FTE students).

Governor Does Not Propose Any Changes to Student Centered Funding Formula for Budget Year. Largely given that certain key changes were made to formula last year, the Governor’s budget does not propose any further changes to the formula in 2020‑21. The Governor’s Budget Summary does express support for the oversight committee’s recommendation to add first‑generation college status to the funding formula, but acknowledges that the Chancellor’s Office will need time (at least one year) to begin collecting the associated data.

Assessment

Bulk of COLA Augmentation Needed to Cover Higher Pension Costs. Augmenting apportionment funding can help community colleges cover employee salary increases, higher health care premiums, and higher pension rates, among other cost increases. Under the Governor’s budget, we estimate that districts’ pension costs are likely to increase by about $120 million in 2020‑21—absorbing more than two‑thirds of the proposed apportionment augmentation. Under the Governor’s budget, districts would have less than $50 million remaining to cover increases in other compensation and operating expenses.

Proposed Enrollment Growth Is in Line With Recent Growth Trends. The Governor’s proposed growth rate of 0.5 percent reflects about the same level of growth that districts have been able to use in the past couple of years. In 2017‑18, districts used $33 million in budgeted growth funding (a growth rate of 0.6 percent). The most recent estimates provided by the Chancellor’s Office for 2018‑19 suggest that districts are using about $25 million in budgeted growth funding (a growth rate of 0.4 percent). The Governor’s proposed $32 million for the budget year falls within this range. As noted below, better information will become available over the next few months that will provide clearer insight into budget‑year demand for enrollment growth.

Recommendations

Withhold COLA Decision Until Better Data Is Available This Spring. As with school funding, the COLA for CCC apportionments is based on the price index for state and local governments. The COLA rate will be locked down in late April when the state receives updated data from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis. By early May, the Legislature also will have better information on state revenues, which, in turn, will affect the amount available for new CCC Proposition 98 spending. If additional revenues are available in May, the Legislature may wish to provide an even greater increase than the Governor proposes to community college apportionments. A larger increase would help all community college districts address rising pension and health care costs while also addressing pressure to increase employee salaries.

Withhold Enrollment Growth Decision Until Current‑Year Data Is Available. By the time of the May Revision, the Chancellor’s Office also will have provided the Legislature with final 2018‑19 enrollment data and initial 2019‑20 enrollment data. At that time, the Legislature will have better information to assess the extent to which colleges will use their budgeted 2019‑20 enrollment growth funding. This information, in turn, will help the Legislature assess whether the Governor’s proposed 0.5 percent enrollment growth expectation for the CCC system in 2020‑21 is reasonable.

Apprenticeship Instructional Hours

In this section, we provide background on apprenticeships, describe the Governor’s proposals to increase funding for apprenticeship instructional hours, assess those proposals, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

State Has 93,000 Apprentices in Various Trades. About 70 percent of apprentices in the state are in the construction trades—training to be carpenters, plumbers, electricians, or one of many other types of construction workers. The next largest number of apprentices are in public safety, including firefighting. Apprenticeships in these sectors are commonly referred to as “traditional apprenticeships.” (The state has recently made efforts to develop apprenticeships in other industry sectors, as we discuss in the next section of this report.)

Apprenticeships Combine On‑the‑Job Training With Classroom Instruction. Apprenticeship programs consist of two key components: (1) on‑the‑job training completed under the supervision of skilled workers and (2) classroom learning, known as related and supplemental instruction (RSI). Apprentices commonly complete on‑the‑job training and RSI concurrently, though RSI begins first in some programs. While program lengths vary, traditional apprenticeships typically take three to five years to complete. Apprentices are employed during the program and receive wage increases as their training progresses. Upon completing the program, apprentices attain journeyman (skilled worker) status in their trade.

State Reimburses Sponsors for Instruction Through CCC Categorical Program. Traditional apprenticeships are sponsored by employers and labor unions. These sponsors are largely responsible for developing the program, recruiting apprentices, and providing on‑the‑job training. It is also common for sponsors to directly provide RSI, taught by their employees at stand‑alone training centers. Sponsors typically cover the majority of the costs of instructing and training apprentices, often maintaining a training trust fund to support those costs. However, the state has a longstanding CCC categorical program that reimburses sponsors for a portion of their instructional costs. Sponsors are reimbursed at the hourly rate set for certain CCC noncredit instruction (currently $6.45). Sponsors must partner with a school or community college district to qualify for these funds. To receive reimbursement, the sponsor submits a record of RSI hours to the partnering district, which in turn submits those hours to the Chancellor’s Office. The Chancellor’s Office provides RSI funds to the district, which takes a small portion of the funds off the top and then passes the remaining funds back to the sponsor.

If Instructional Hours Exceed Projections, Full Reimbursement Is Not Guaranteed. Each year, the Chancellor’s Office allocates RSI funds to districts based on projected instructional hours in their affiliated apprenticeship programs. In some years, the amount of funding the state budgets for RSI falls short of covering all hours. When this occurs, the Chancellor’s Office pro‑rates funding downward. From 2013‑14 through 2017‑18, actual RSI hours exceeded initial projections, leading to pro‑rata reductions. In 2018‑19, the state provided $36 million one time to backfill the shortfalls across that five‑year period.

State Increased Funded Hours Most Recently in 2018‑19. That year, the state provided an ongoing augmentation of $23 million largely to align funding with projected growth in RSI hours. Although 2018‑19 RSI hours have not yet been finalized, the most recent estimates from the Chancellor’s Office suggest that the amount of RSI hours provided was 7 percent lower than projected in that year, which would leave about $4 million unused. The state provided no further increase in funded RSI hours in the 2019‑20 Budget Act.

Proposals

Governor Proposes Retroactive One‑Time Increase in Funded Instructional Hours for 2019‑20. Since budget enactment, the administration has revised its estimates of 2019‑20 RSI hours based on updated data from the Chancellor’s Office. The revised level is 32 percent higher than the budgeted level. Under these estimates, RSI funding would fall short of covering all certified hours by $20 million. The Governor’s budget would provide this amount one time to cover the estimated 2019‑20 shortfall.

Governor Provides Ongoing Augmentation for Projected Increase in Instructional Hours in 2020‑21. Compared with the revised current‑year level, the administration projects RSI hours will increase by 8 percent in the budget year. The Governor’s budget provides $28 million ongoing in 2020‑21 to fund these projected hours. The hourly rate would be $6.59, reflecting the 2.29 percent COLA applied to many Proposition 98 programs.

Assessment

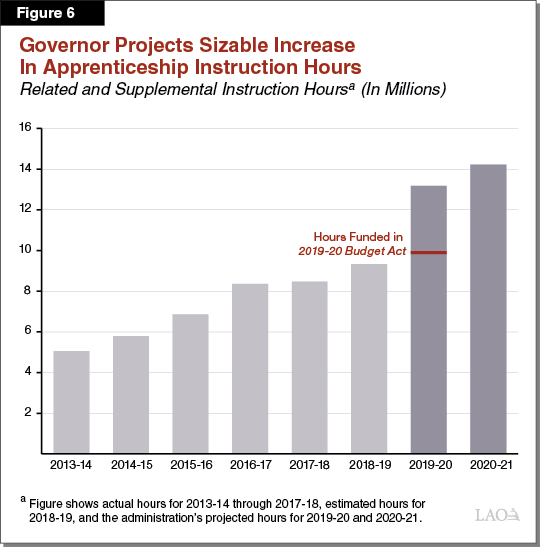

Administration’s Projections Depart Notably From Recent Trends. Based on the most recent estimates available, RSI hours increased at an average annual rate of 13 percent from 2013‑14 to 2018‑19. As Figure 6 shows, the estimates underlying the Governor’s current‑ and budget‑year proposals depart from this trend. Specifically, the administration’s estimate for 2019‑20 is 41 percent higher than the revised 2018‑19 level. Given the magnitude of this increase, we believe the estimates warrant further review as updated data becomes available. The Chancellor’s Office indicates it will finalize its 2018‑19 RSI numbers in the next few weeks and may subsequently update its 2019‑20 estimates.

Prospective Changes Are More Likely to Affect Behavior Than Retroactive Changes. If sponsors know the state has funded more instructional hours, they might decide to increase the number of apprentices they train moving forward. Compared with prospective funding changes, retroactive adjustments (such as the one the Governor proposes for 2019‑20) are less likely to have the effect of changing sponsors’ behavior. By the time sponsors were to receive any additional 2019‑20 funds, they will have already decided how much apprenticeship instruction to provide in that year based on the funding level enacted last June.

Recommendations

Withhold Action Pending Updated Data on Instructional Hours. We recommend the Legislature withhold taking action on this proposal until it has received updated data on prior‑ and current‑year RSI hours. To this end, the Legislature could direct the Chancellor’s Office to share updated data during a spring hearing. Reviewing the more recent data is particularly important given the administration’s projection for 2019‑20 departs so notably from recent trends. Moreover, the administration builds its budget‑year proposal off the higher, projected 2019‑20 level, thereby compounding the fiscal effect of any potential underlying data issues. In considering the Governor’s proposals, we further encourage the Legislature to prioritize the ongoing augmentation for 2020‑21 over the retroactive adjustment for 2019‑20, as the latter is less likely to impact the amount of apprenticeship instruction provided.

California Apprenticeship Initiative

In this section, we provide background on the California Apprenticeship Initiative (CAI), describe the Governor’s proposal to double the amount of funding going to CAI, assess that proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

State Funds Initiative to Create New Apprenticeship Programs in Nontraditional Sectors. In 2015‑16, the state created CAI to support new apprenticeship programs in high‑growth industry sectors—such as health care, information technology, and clean energy—that have not traditionally used the apprenticeship model. The state has provided $15 million annually—a total of $75 million to date—for CAI.

CAI Funds Are Awarded to Districts Through Competitive Grant Process. Community college districts and K‑12 agencies (including school districts and county offices of education) are eligible for CAI grants. In the most recent grant round, the Chancellor’s Office awarded 84 percent of grant funds to community colleges, with the remainder awarded to K‑12 agencies. Applications are scored based on the demonstrated need for the proposed program and how the program would respond to that need, among other components. To be eligible for funding, applicants must receive a minimum score of 75 (out of 100) on their application and demonstrate a commitment from one or more employers to hire participating apprentices.

CAI Grants Are Intended to Support Apprenticeship Start‑Up Costs. In the most recent grant round, grants ranged from $100,000 to $500,000 each and were spread across a three‑year period. Grant funding is intended to cover program start‑up costs. These costs include curriculum development and outreach to employer partners. Grantees are also allowed to use the funds for various ongoing needs, including instructor salaries, support staff, and tools and supplies. As CAI funds are only available for a limited term, grantees are expected to find other fund sources to cover ongoing program costs once the grant expires. To this end, applicants for CAI grants are required to describe how they plan to ensure the long‑term financial sustainability of their proposed programs.

Grantees Are Expected to Meet Certain Program Standards and Enroll Apprentices. CAI grantees are required to have newly created apprenticeship programs approved by the Division of Apprenticeship Standards (DAS), the entity within the California Department of Industrial Relations that oversees state‑approved apprenticeship programs. In addition, they are required to enroll at least one apprentice for every $20,000 in grant funds awarded. The Chancellor’s Office reports that CAI‑funded programs have enrolled 1,252 apprentices from 2017‑18 through 2019‑20. Of these apprentices, 266 have completed their program to date. While most CAI grants have focused on new apprenticeship programs, a few grant rounds have supported preapprenticeships, as the box below describes.

Preapprenticeship Programs

Some California Apprenticeship Initiative (CAI) Grants Have Focused on Preapprenticeships. Preapprenticeships are training programs designed to prepare participants to enter an apprenticeship program. Preapprenticeships typically last several months and include both classroom instruction and hands‑on training. Under Chapter 704 of 2018 (AB 235, O’Donnell), preapprenticeships—like apprenticeships—are reviewed and approved by the Division of Apprenticeship Standards. The Chancellor’s Office has designated several rounds of CAI grants for new preapprenticeship programs targeting underrepresented populations, with the goal of expanding diversity in the apprenticeship applicant pool. CAI has funded preapprenticeship programs in various sectors, with the largest number in the construction trades. Based on the most recently available data, the programs had enrolled a total of 3,248 preapprentices, of which 1,139 had completed.

Initial Grantees Participated in Evaluation of Early Outcomes. The Chancellor’s Office designated $1 million from the initial 2015‑16 CAI allocation toward technical assistance and evaluation. As part of these activities, the Chancellor’s Office partnered with the Foundation for California Community Colleges and Social Policy Research Associates on an evaluation of CAI’s implementation and early outcomes through February 2018. As of that date, the first two rounds of apprenticeship grantees had established 17 new apprenticeship programs, with the largest number of programs in manufacturing, health care, and transportation and logistics. As the grant period had only recently ended for the first round of grantees, little information was available at the time of the evaluation on whether these programs could cover ongoing costs moving forward.

Proposal

Governor Proposes to Double Ongoing Funding for CAI. Under the proposal, CAI would receive a $15 million ongoing augmentation in 2020‑21, bringing total ongoing funding to $30 million. The Governor proposes no other changes to CAI.

Assessment

Insufficient Data to Assess Demand for Additional CAI Funding. In most of the recent rounds of CAI grants, the total amount of funding requested by applicants has exceeded the total amount of funding available. A notable share of the requested funds, however, has been associated with ineligible applicants. For example, of the 33 applications for the most recent grant round, 12 applications did not attain the minimum score to receive funding, and 2 were not scored because they did not meet application requirements. As of this writing, neither the administration nor the Chancellor’s Office has provided data on the amount of unmet demand for grants among eligible applicants. Thus, it remains an open question whether there is enough demand from grantees to warrant an ongoing augmentation for CAI.

Key Questions Remain About Financial Sustainability of CAI‑Funded Programs. While CAI is intended to create lasting programs that will serve apprentices in years to come, the state does not yet have data on how many CAI grantees have continued their programs beyond the grant period. As grantees are receiving up to $20,000 per apprentice and commonly use the funds for ongoing expenses, key questions remain about how programs will cover their costs moving forward. The Foundation for California Community Colleges indicates it is currently partnering with Social Policy Research Associates on a follow‑up study on this topic. The study will examine which programs from the first three rounds of grants continued after their grants expired, with a focus on their ongoing funding sources, partnerships, and effective practices. This study is expected to be completed this summer.

Recommendations

Reject CAI Augmentation at This Time. We believe it would be premature to expand CAI before learning whether the new apprenticeship programs created to date can be sustained after grant funding ends. Later this year, the follow‑up study described above or other evaluation activities supported by the Chancellor’s Office could provide critical information about the programs sustained to date. Having better information on initial CAI outcomes could inform future budget decisions for the program. If the findings were to show that most apprenticeship programs ended due to insufficient funding once their CAI grant expired, the Legislature might consider changes next year, including potentially refining the grant requirements. Alternatively, if the findings were to show that many grant recipients have identified ongoing fund sources, then the Legislature might consider expanding the program. Were this to be the case, we encourage the Legislature to ensure that any proposed augmentation is based on strong evidence of unmet demand for CAI grants.

Work‑Based Learning

In this section, we provide background on existing CCC initiatives that incorporate work‑based learning, describe the Governor’s proposal to create a one‑time work‑based learning initiative, assess that proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

Work‑Based Learning Covers a Broad Range of Career Readiness Activities. Defined broadly, work‑based learning refers to activities that promote career exploration and preparation. Schools choose what specific work‑based learning opportunities to provide their students. Common opportunities include guest classroom speakers, job shadowing, internships, and apprenticeships. Work‑based learning opportunities can be incorporated into high school and college curricula across disciplines. Several existing CCC initiatives include work‑based learning components, as we describe below.

Work‑Based Learning Is Key Component of Strong Workforce Program. In 2014, the Board of Governors convened the Task Force on Workforce, Job Creation, and a Strong Economy to recommend improvements in career technical education (CTE). The first of the task force’s 25 recommendations was to “broaden and enhance career exploration and planning, work‑based learning opportunities, and other supports for students.” In 2016‑17, the state created the Strong Workforce Program based on the task force’s recommendations. Under the Strong Workforce Program, colleges are required to coordinate their CTE activities within seven regional consortia. The state provides $248 million ongoing for this program.

Guided Pathways Initiative Also Includes Work‑Based Learning. In 2017‑18, the state created the Guided Pathways initiative. This initiative provided CCC with $150 million one time to integrate existing student support programs, build internal capacity for program planning and implementation, and develop structured academic course sequences for entering students. State law defines Guided Pathways programs to include “group projects, internships, and other applied learning experiences to enhance instruction and student success.” The majority of Guided Pathways funds are being allocated to colleges in stages across five years, ending in 2021‑22. The funds are designated for one‑time purposes, such as faculty and staff release time, professional development, and information system upgrades related to pathways implementation. For 2019‑20, the Board of Governors requested that the state provide $20 million one time to expand work‑based learning within the Guided Pathways framework. The Governor did not include that request in his proposed budget last year, nor was it included in the enacted budget.

CCC System Recently Completed Work‑Based Learning Pilot. In 2017, the Chancellor’s Office partnered with the Foundation for California Community Colleges to launch an 18‑month pilot to expand access to work‑based learning opportunities. Six community colleges, one community college district, and two Strong Workforce regional consortia participated in the pilot. Through a series of workshops and other activities, participants identified several systemwide opportunities for enhancing and expanding work‑based learning. The identified opportunities included establishing a common understanding of work‑based learning among stakeholders (including colleges, employers, and students), aligning work‑based learning with colleges’ broader student support efforts, and breaking down silos between general education and CTE. Participating colleges also adopted several services and technology platforms intended to facilitate career exploration, enable paid work experiences, and assess students’ employability skills. The Chancellor’s Office provided $200,000 in Strong Workforce Program funding for this pilot. Participating colleges, districts, and regional consortia also contributed a total of $325,000.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $20 Million One Time for New Work‑Based Learning Initiative. The funds would support competitive grants to colleges to “expand the use of work‑based learning instructional approaches that align with the Guided Pathways framework.” The proposal is based on the one that the Board of Governors submitted to the state for 2019‑20. This year, the Governor indicates the proposal aligns with his goal to expand apprenticeships. Based on conversations with the Chancellor’s Office, the initiative could help fund additional apprenticeships, internships, clinical practicums, and applied learning experiences within the classroom. (It would not cover career exploration activities, such as guest speakers.) The Chancellor’s Office has indicated it would provide grants of up to $1 million to 20 colleges, including at least 2 colleges in each of the 7 Strong Workforce regions. The funds would be available through June 30, 2025.

Assessment

State Lacks Baseline Data on Work‑Based Learning. Although CCC’s recent pilot helped identify opportunities for expanding work‑based learning, several key questions remain about the work‑based learning that colleges currently provide. Notably, systemwide data on the number of CCC students currently engaging in internships and other work‑based learning experiences is not available. The state also does not have data on the comparative effectiveness of existing work‑based learning experiences. In addition, data is not available on how much more work‑based learning students would like, what specific kinds of experiences they would like, the barriers they currently face to obtaining such experiences, and the cost of providing more work‑based learning opportunities. Without this information, it is difficult to quantify the need for additional state funding.

With Several Programs Already Focused on Work‑Based Learning, Another Is Not Warranted. Work‑based learning is explicitly part of the Strong Workforce Program and Guided Pathways initiative. As discussed in the previous two sections of this report, the state also supports apprenticeships—one form of work‑based learning—through both a categorical program that reimburses sponsors for instructional hours and a competitive grant program that provides seed funding for new apprenticeships. Moreover, the state is taking steps to increase coordination and cohesion across CCC initiatives, as discussed in the above box titled "CCC System Support". Creating a new one‑time initiative specific to work‑based learning could have the opposite effect—further fragmenting CTE and student support efforts.

One‑Time Funds Are Not a Good Fit for Supporting the Proposed Activities. Based on conversations with the Chancellor’s Office, the proposed grants would likely support a range of expenses, including work‑based learning coordinators, stipends for industry practitioners to provide work‑based learning opportunities, curriculum development, and student screening and preparation. These are primarily ongoing activities that would require continued funding. Without a plan to cover the costs moving forward, these activities are at risk of ramping up, then ending when the grant period ends. Such an approach creates cost pressure for the state to sustain the activities in future years.

Recommendations

Reject Governor’s Proposal. Given all our concerns discussed above, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposed work‑based learning initiative and redirect the funds to other one‑time Proposition 98 priorities. (For example, later in the report, we encourage the Legislature to consider providing more one‑time funding to address existing CCC liabilities, including its maintenance backlog.) If the Chancellor’s Office determines that work‑based learning opportunities are insufficient, it could use funds from the proposed System Support Program to undertake a needs assessment and compile key baseline data. It then could provide systemwide guidance on how to support the expansion of work‑based learning activities using existing programs and resources.

Food Pantries

In this section, we provide background on food insecurity among CCC students, describe the Governor’s proposal to provide ongoing funding for campus food pantries, assess that proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

Substantial Share of CCC Students Report Food Insecurity. Food insecurity typically refers to having limited or uncertain access to adequate food. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) developed a set of questions to measure the incidence of food insecurity. In 2016 and 2018, the CCC system partnered with the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice to administer surveys based on USDA’s questions to students at 57 community colleges (about half of colleges). These surveys found that 50 percent of respondents had faced food insecurity within the past 30 days. (Because the survey had a 5 percent response rate, respondents may not be representative of the overall CCC student population.)

California Operates Food Assistance Program for Low‑Income People. The CalFresh program, administered by the California Department of Social Services (DSS), is California’s version of the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). This program provides eligible households with funds on a monthly basis to purchase food. The amount of the benefit depends on a household’s size. For example, the maximum monthly benefit is $194 for an individual and increases to $646 for a household of four. To qualify for CalFresh, a household’s income cannot exceed 200 percent of the federal poverty level, among other requirements. In 2019‑20, the CalFresh monthly income cap for an individual is $2,082 and for a household of four is $4,292.

Some Students Are Eligible for Food Benefits Through CalFresh. While college students enrolled half‑time or more are generally ineligible for CalFresh, federal law makes several exceptions to this rule. For example, college students may be eligible for CalFresh if they are working at least 20 hours per week, enrolled in certain programs designed to increase employability, have children, have a disability, or receive other forms of public assistance. Despite their eligibility, a recent study from the Government Accountability Office estimated 57 percent of college students eligible for SNAP nationally are not receiving benefits.

To Date, State Has Provided One‑Time Funds to Address Student Food Insecurity. In 2017‑18, the Legislature created the Hunger Free Campus initiative at UC, CSU, and CCC. Over the past three years, the state has provided a total of $16.4 million in one‑time Proposition 98 funds for this initiative at CCC ($2.5 million in the 2017‑18 budget package, $10 million in 2018‑19, and $3.9 million in 2019‑20). The Chancellor’s Office allocated these funds to colleges based on their FTE student count. Participating colleges are required to (1) designate an employee to ensure students have the information needed to enroll in CalFresh and (2) provide an on‑campus food pantry or food distributions.

Nearly All CCC Campuses Now Have Food Pantries. Under the Hunger Free Campus initiative, the Chancellor’s Office was required to report on community colleges’ activities to address food insecurity. As of 2018‑19, 109 colleges (out of 114 colleges with a physical campus) reported having an on‑campus food pantry or food distributions, and 73 colleges reported providing CalFresh information to students. Colleges are supporting these efforts by pooling Hunger Free Campus funding together with other public funds and private donations. CCC is in the midst of conducting a follow‑up survey on the number of students being served by on‑campus food pantries and the number receiving CalFresh enrollment assistance.

Most Food Pantries Rely Heavily on Donations and Part‑Time Staff. Most food pantries receive donated or low‑cost food from community partners, including food banks (organizations that store donations for distribution to pantries). Based on conversations with administrators, CCC food pantries typically do not have dedicated full‑time staff. More commonly, food pantries are administered by part‑time staff or full‑time staff who have other responsibilities.

DSS Is Required to Report on Student CalFresh Eligibility and Participation. Chapter 33 of 2018 (AB 1809, Committee on Budget) required DSS to consult with county social services agencies, the higher education segments, and other stakeholders to improve coordination and expand access to CalFresh for college students. Chapter 53 of 2019 (SB 77, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) subsequently required DSS to submit a report containing an estimate of the number of students at each public higher education segment who are eligible for CalFresh and receiving CalFresh benefits. The report also was to contain recommendations for ways to increase CalFresh participation among eligible students. DSS indicates this report is in progress. It was due to the Department of Finance and the Legislature by November 1, 2019.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $11.4 Million Ongoing to Support Campus Food Pantries. These funds would provide $100,000 to each of 114 community colleges to support on‑campus food pantries or distributions. Colleges would have discretion to spend the funds on staffing, food, or other needs.

Assessment

Proposal Expands on Legislature’s Recent Budget Actions. Over the past three years, the Legislature has taken actions to provide one‑time funding for the Hunger Free Campus initiative at CCC. The Governor’s proposal to create an ongoing food pantry program aligns with the Legislature’s demonstrated priorities. Relative to the one‑time funds provided to date, the proposed ongoing funds would provide greater stability in services. Because operating a food pantry entails ongoing costs, colleges have difficulty maintaining consistent levels of service using one‑time allocations that fluctuate from year to year.

At Proposed Funding Level, Allocation Method Is Reasonable. All food pantries incur some basic operational costs to remain open. Most notably, food pantries need staff to obtain food supplies from community partners, manage inventory, and assist students who visit the pantries. We believe the Governor’s proposal to allocate $100,000 to each college would help all colleges cover these fixed costs, promoting greater consistency in food pantry services across the CCC system. If additional funds beyond the proposed $11.4 million were to become available, we think considering an allocation method tied more closely to student need would be warranted. Whereas minimum staffing costs are fixed, the cost of providing food likely is higher for colleges serving larger numbers of low‑income or food‑insecure students.

Proposal Misses Opportunity to Link Food Pantries With Broader Benefits. While the Governor’s proposal would have colleges provide food to students, it would not require colleges to help students access CalFresh benefits. Assistance with CalFresh enrollment, however, has been an important component of the state’s previous efforts to address student food insecurity. To date, the state has paired making food pantries available with providing CalFresh enrollment assistance. By pairing the two strategies, food pantries not only help students who do not qualify for CalFresh, they are entryways for qualifying students to apply for longer‑term food benefits. Helping students access benefits already available through the social services system, in turn, can reduce the demand for colleges to provide food directly.

Proposal Does Not Provide for Continued Oversight. Unlike the Hunger Free Campus initiative and other related state initiatives, the Governor’s proposal does not include any reporting requirements. Without key information about students’ use of food pantries and participation in CalFresh, the Legislature cannot assess whether the new program is having its intended effect.

Recommendation

Modify Governor’s Proposal by Building Upon Past Efforts. Over the past three years, colleges have been implementing the Hunger Free Campus initiative, which has many promising program components. If the Legislature chooses to spend $11.4 million ongoing for food pantries, we recommend it build off these earlier efforts. In particular, we think the Hunger Free Campus initiative has two components that should be retained moving forward. First, we recommend directing the funds toward not only food pantries but also CalFresh enrollment assistance, as the latter program is intended to provide larger, more sustained benefits for students. Second, we recommend requiring the CCC system to report annually on the unduplicated number of students who use college food pantries and receive CalFresh enrollment assistance. The Legislature also could consider requiring DSS to report annually on the number of college students applying for and receiving CalFresh benefits. Given the Legislature would be creating an ongoing program, we recommend making these changes through trailer legislation.

Faculty Diversity

In this section, we provide background on community college faculty and the CCC Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) program, describe the Governor’s proposal to create a faculty diversity fellowship pilot, assess the proposal, and make an associated recommendation.

Background

Community College Districts Employ a Total of More Than 60,000 Faculty. Typically, community college faculty must have a master’s degree to teach. Requirements, however, are different for certain career technical education and noncredit programs. In these areas, faculty may meet CCC teaching requirements by having an associate or bachelor’s degree with a certain number of years of professional experience. Community college districts are responsible for recruiting and hiring their faculty. About one‑third of faculty are full time and two‑thirds are part time. In addition to faculty, districts employ a total of about 30,000 other staff, including administrators and clerical staff.

State Funds an EEO Program for CCC. Decades ago, the state established a program to help the community colleges promote inclusionary practices in hiring faculty and other district staff. In 2016‑17, the state augmented funding for the program—bringing ongoing funding up to $2.8 million—the level at which it has remained. From this appropriation, the Chancellor’s Office provides a base allocation of about $40,000 to each district on the condition that it meets certain criteria. These criteria include (1) developing a plan for promoting equal employment opportunities and updating the plan every three years and (2) adopting EEO best practices identified by the Chancellor’s Office. These best practices include providing campuswide cultural awareness training and offering mentoring programs to newly hired faculty and other employees.

Districts Use EEO Funding to Support Recruitment and Hiring Practices. Districts typically use their EEO funds for outreach, recruitment, and training. For example, districts commonly provide members of hiring committees (such as department chairs) with anti‑bias training. Budget provisional language linked with the state’s EEO appropriation for the colleges requires the Chancellor’s Office to report certain EEO information to the Legislature annually through December 2021. Specifically, the annual report must include (1) data on the racial/ethnic and gender composition of district faculty and (2) information on the efforts of the Chancellor’s Office to support districts in implementing EEO practices.

Statute Authorizes Districts to Create Faculty Internship Programs. These programs allow districts to employ graduate students as part‑time faculty. Pursuant to statute, interns may be within one year of receiving their master’s degree. These programs also may be open to individuals who hold a master’s degree but lack teaching experience. Under the program, interns may receive mentoring by full‑time faculty from the district.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $15 Million One Time to Create Faculty Diversity Fellowship Pilot. According to the Chancellor’s Office, the purpose of the pilot is to promote a more diverse faculty workforce at the community colleges. Specifically, the proposal seeks to have full‑time faculty more closely mirror the race/ethnicity of community college students. The pilot would be administered by the Chancellor’s Office. Members of the Chancellor’s Office and other CCC representatives (such as from the Academic Senate) would form a selection committee and solicit applications for fellowships. Eligible applicants could include current graduate students or individuals who recently received their master’s degree. Each year for a total of three years, the selection committee would award between 30 and 40 fellowships for a one‑year placement at a local community college. The selection committee also would be responsible for identifying faculty mentors at the participating colleges.

Fellows Would Engage in Various Activities. Once chosen, fellows would be assigned to teach in the classroom, with faculty mentors observing and providing feedback. Outside of class, fellows would hold student office hours and participate in campuswide and systemwide activities (such as attending student success conferences) to learn more about the CCC system and its mission. Provisional language requires the funds to be used to support compensation for the fellows and faculty mentors as well as professional development activities for the fellows. According to the Chancellor’s Office, each fellow would receive a $15,000 stipend. At the end of the fellowship, fellows would be encouraged to apply for a full‑time CCC position, should one become available in their discipline. Based on our conversations with the Chancellor’s Office, some of the proposed funding could be used by districts to cover initial hiring costs (such as covering travel/relocation costs of new hires).

Assessment

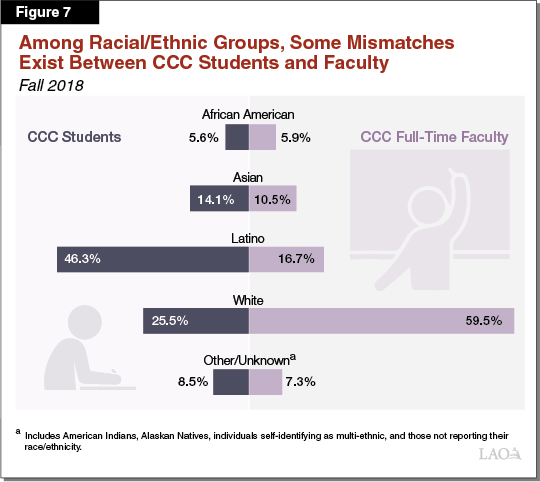

Mismatch Exists Between CCC Faculty and Students of Certain Races/Ethnicities. Figure 7 shows the percentage of CCC full‑time faculty by race/ethnicity in comparison to the CCC student body. As the figure shows, Latino faculty are significantly underrepresented compared with the proportion of Latino students enrolled at CCC. White faculty, meanwhile, are overrepresented compared with the proportion of white CCC students. Asian‑American faculty are somewhat underrepresented. Finally, the proportion of African‑American faculty aligns very closely to the proportion of African‑American students enrolled at CCC. Though the figure shows only full‑time faculty, the racial/ethnic demographics of part‑time faculty are very similar.

Proposal Fails to Identify Root Causes of Problem. Given the current mismatches, we believe the Governor’s budget has identified an important issue. Our primary concern with the proposal, though, is that it lacks an explanation of the core problems and an explicit link to how the proposed program would address those problems in a systemic way. For example, is the root problem that districts consistently fail to draw from a sufficiently diverse faculty applicant pool? Alternatively, is the root cause that otherwise qualified individuals from certain backgrounds do not feel welcome on campus? If so, how would a fellowship program address those underlying problems at districts? Moreover, the proposal lacks any insight into why a faculty/student mismatch exists between certain historically underserved groups (such as Latinos) but not others (such as African‑Americans). Without understanding the reasons behind these differences, assessing what impact a fellowship potentially could make is difficult.

Proposal Lacks Key Details and Basic Reporting Requirements. Most importantly, the proposal has neither a rationale for why $15 million was chosen for the program, nor a budget for how the funds would be spent. Without this basic information, the Legislature cannot properly review the funding request or have assurance that funds would be spent effectively. The proposal also lacks any evaluation or reporting requirements and is silent on how programs would be sustained financially at the end of the three‑year pilot period.

Recommendation

Withhold Recommendation Pending Receipt of Key Information. We recommend the Legislature request the administration and Chancellor’s Office during spring budget hearings to provide further analysis and information about the proposal. At a minimum, we recommend they answer the following key questions:

- Why faculty from certain historically disadvantaged racial/ethnic groups remain underrepresented at the community colleges despite progress among other groups.

- How the administration’s proposal would address the root causes for why Latino faculty remain underrepresented.

- How the proposed funding level was chosen and why it is justified.

- How funds would be allocated across the three‑year period and how the funds would be spent.

- How the pilot’s effectiveness would be evaluated and when results would be reported.

- Were the pilot to show promising results, how it would be sustained and scaled by CCC when one‑time state funding expired.

- How the pilot would interact with colleges’ ongoing EEO efforts over the next three years and how their relative effectiveness would be compared.

If the Legislature does not receive satisfying answers to the above questions by this spring, it could invite the administration to return in a later year with a more complete proposal.

Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours

In this section, we provide background on faculty office hours, describe the Governor’s proposal to provide $10 million one time for the Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours program, assess the proposal, and make associated recommendations.

Background

Districts Require Full‑Time Faculty to Hold Office Hours. Instruction at the community colleges is provided by nearly 20,000 full‑time (tenured/tenure‑track) faculty and more than 40,000 part‑time (adjunct) faculty. District collective bargaining agreements typically require full‑time faculty to hold a certain number of weekly office hours as part of their regular responsibilities. Full‑time faculty are compensated for providing these office hours. The purpose of office hours is to provide academic assistance and other forms of guidance to students.

District Policies on Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours Vary. Whereas holding office hours is a standard requirement for full‑time faculty, office‑hour policies for part‑time faculty vary by district. Based on data collected in fall 2019 by the California Federation of Teachers, about 20 percent of districts neither require nor compensate part‑time faculty for holding office hours. Another roughly 30 percent of districts require part‑time faculty to hold a minimum number of office hours per week and compensate faculty to do so. Office hours at the remaining approximately 50 percent of districts are voluntary for part‑time faculty, and those that opt to hold office hours are compensated (subject to available funding at the district). The number of office hours for which faculty are compensated per course and the amount they are paid per hour varies widely among districts.

Decades Ago, Legislature Created a Program to Support Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours. In the late 1990s, the Legislature created a program designed to provide a fiscal incentive for districts to encourage more part‑time faculty to offer more office hours. Under the Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours program, districts that pay part‑time faculty for office hours can apply for state funding on a reimbursement basis. Pursuant to statute, the reimbursement may cover up to 50 percent of a district’s costs. Districts must submit their reimbursement claims to the Chancellor’s Office by June each year. According to the Chancellor’s Office, typically about half of districts submit claims. The amount available for reimbursement each year depends on the level of funding appropriated in the annual state budget act.

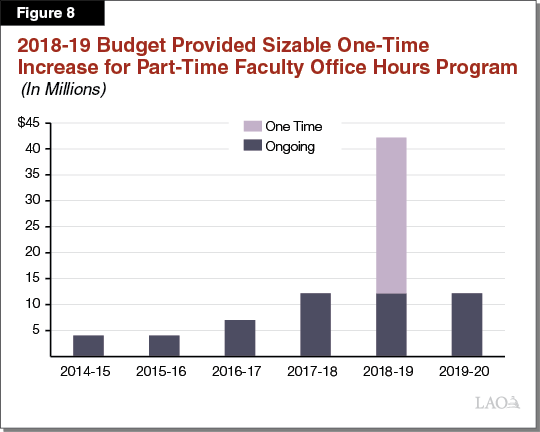

State Funding for the Categorical Program Has Varied in Recent Years. Figure 8 shows the annual amount of funding appropriated for the program over the past six years. Typically, the state has provided ongoing funding for the program given its ongoing nature. The one exception over the past six years was in 2018‑19. That year, the Legislature approved a $30 million one‑time augmentation—more than tripling funding for the program that year. In 2019‑20, the state returned to providing $12 million for the program (the same ongoing level the state had provided the previous two years).

Significant Amount of One‑Time Funding Remains From 2018‑19. In most years, the state funding for the program and the total cost of claims has resulted in the Chancellor’s Office reimbursing districts for about 35 percent (rather than 50 percent) of their costs. A notable exception was in 2018‑19. In that year, the Chancellor’s Office was able to provide 50 percent reimbursement to districts that submitted claims. Even then, only $20 million of the $42 million appropriation was claimed and allocated. As a result, the remaining $22 million is available for reimbursement in 2019‑20 and, if not all used in 2019‑20, in the budget year.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $10 Million One‑Time Augmentation. When combined with $12 million in base funds, total funding for the Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours program would reach $22 million in 2020‑21.

Assessment

Supporting Part‑Time Faculty Office Hours Is Consistent With Legislative Priorities. The Legislature has had a longstanding interest in encouraging districts to compensate part‑time faculty for office hours. Office hours provide students an opportunity to receive one‑on‑one assistance. During office hours, students may discuss difficult course material with faculty, ask for academic or career guidance, or even inquire about support services.

One‑Time Funding Is Not a Good Fit for the Program. Unlike certain types of operating expenses—such as developing a new program—faculty office hours are an annual, ongoing activity. While a one‑time augmentation supports districts and students for a particular year, such funds very likely will not change districts’ policies on compensating part‑time faculty for office hours.

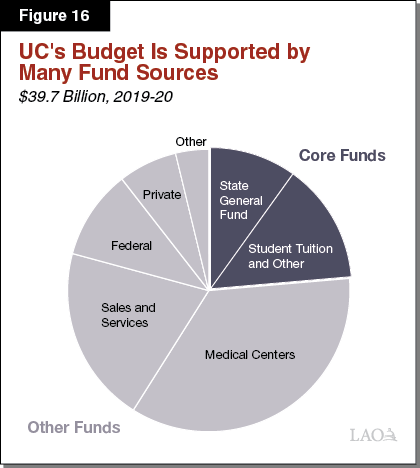

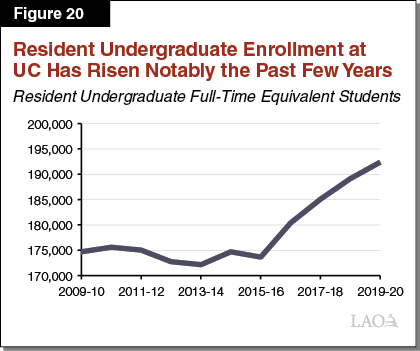

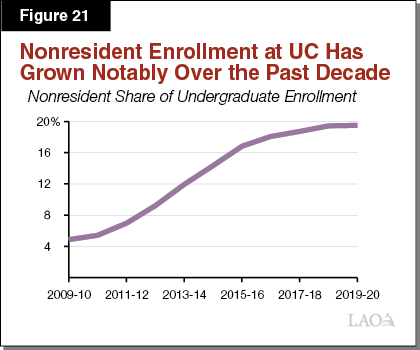

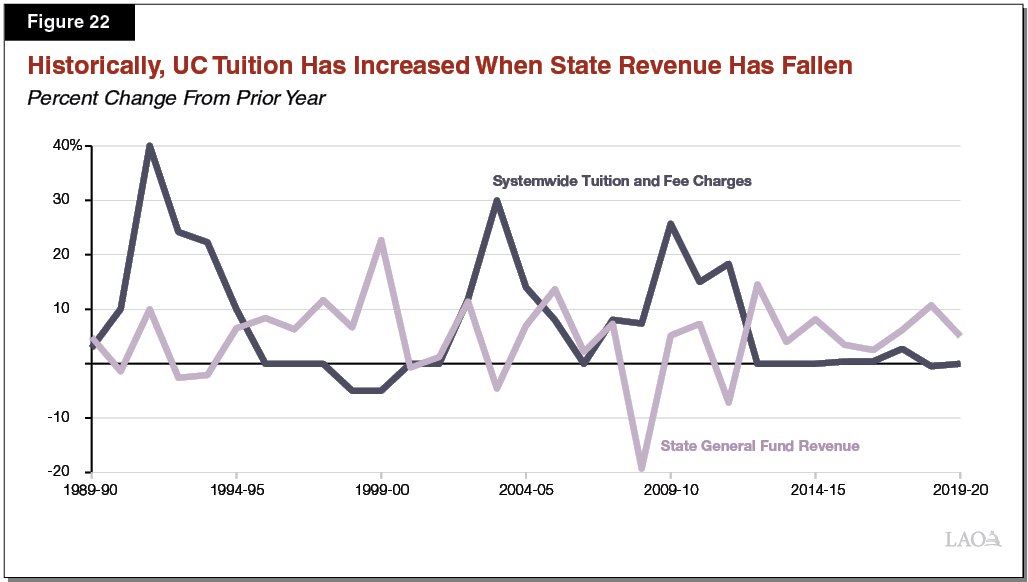

Recommendations