LAO Contact

November 10, 2020

Expanding Access to Safe and Affordable Drinking Water in California—A Status Update

- Introduction

- Background

- Legislature Created Drinking Water Fund and Program

- Beginning Implementation of SB 200

- LAO Comments on Implementation and Oversight

- Conclusion

- Research Citations

Executive Summary

Many Californians Lack Access to Drinking Water That Is Safe and Affordable. Despite federal and state water quality standards, over one million Californians currently lack access to safe drinking water. This is primarily because these residents receive their water from systems and domestic wells that do not consistently meet those established standards. In addition, some Californians struggle to afford access to safe drinking water, sometimes paying in excess of 5 percent of their income on their water bills. In particular, smaller water systems face the most significant challenges in delivering safe and affordable drinking water because their small rate‑payer bases render them less able to afford to undertake necessary water quality upgrades. Such drinking water problems disproportionately affect Latino, rural, and lower‑income communities in California.

State Created New Drinking Water Fund and Program in 2019. Chapter 120 of 2019 (SB 200, Monning) established the Safe and Affordable Drinking Water (SADW) Fund, which provides up to $130 million annually for efforts to provide safe drinking water for every California community. The fund can be used for a broad range of activities for communities and water systems, including emergency water supplies, technical assistance, actions to consolidate water systems, planning support, funding for capital construction projects, and direct operations and maintenance support. Senate Bill 200 tasks the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) with administering the SADW Fund. The board recently created the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) program, which pairs allocations from the SADW Fund with funding from other sources—as well as regulatory actions—to help struggling water systems provide safe drinking water to their customers.

SWRCB Has Begun Implementing SB 200. SWRCB has undertaken several key steps to begin implementing SB 200 and the SAFER program, including expending $130 million that was provided in 2019‑20, developing an Expenditure Policy for the program and Expenditure Plan for 2020‑21 funds, performing a comprehensive statewide needs assessment, and establishing metrics to measure how well the program is achieving its objectives. The board’s stated goals for the program in 2020‑21 are to respond to urgent or emergency needs; address the needs of systems and wells that have been identified as being out of compliance with water quality standards; and accelerate projects to consolidate small water systems, particularly in small disadvantaged communities. From the $130 million available, the largest categories of planned expenditures from the SADW Fund in 2020‑21 include construction ($49 million), technical assistance ($30 million), and emergency water supplies and interim solutions ($19 million).

Good Progress on Implementation Thus Far, but Continued Legislative Oversight Is Important. Our review finds that SWRCB has shown positive progress in its initial year of administering the SADW Fund and implementing SB 200. Despite the logistical complications posed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic, the board has developed required policies and plans, is on track to complete a comprehensive needs assessment by June 2021, and is actively engaged in identifying projects and allocating funding. We also find that the spending priorities SWRCB has identified are consistent with SB 200 and begin to put the state on a path to improving drinking water conditions in affected communities. However, much work remains to be accomplished in order to achieve the state’s goal of ensuring all Californians have access to safe and affordable drinking water. To ensure the SAFER program is implemented effectively and struggling drinking water systems are improved, the Legislature will want to provide careful oversight regarding SWRCB’s ongoing efforts and assess whether additional legislative actions are merited. In particular, oversight issues the Legislature may want to monitor include (1) how well the SAFER program is meeting its objectives based on its adopted performance metrics; (2) whether the state might need to collect additional information to assess the program’s performance, including regarding how effectively the program is addressing the existing disproportionate impacts on the state’s Latino population; (3) the magnitude of drinking water needs that exist statewide and how existing funding aligns with meeting those needs; and (4) how the program will adjust if available funding is lower than anticipated in the coming years given uncertainty about cap‑and‑trade auction revenues, the program’s primary funding source.

Emerging Issues Could Complicate State’s Efforts. The SADW Fund is intended to help the state make progress in expanding access to safe and affordable drinking water to the estimated one million Californians who currently lack this human right. However, certain factors have the potential to worsen existing drinking water issues in some communities. These developments could counteract the progress of the SAFER program by exacerbating the statewide conditions the program is working to improve. In particular, emerging issues the Legislature may want to monitor include (1) whether continued groundwater pumping practices will place additional water systems at risk of failing, and the degree to which implementation of the state’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act will—or will not—mitigate these risks; (2) whether emerging drought conditions could cause vulnerable water systems and wells to go dry; and (3) the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic both on vulnerable households that face significant unpaid water bills and on water systems that are experiencing significant revenue losses.

Introduction

Despite California being the first state in the nation to adopt a policy stating that clean water is a human right, an estimated one million Californians currently lack access to safe and affordable drinking water. Many of the communities experiencing water contamination and shortages are located in the San Joaquin Valley, and low‑income and Latino residents are disproportionately affected. To improve upon these health and environmental justice issues, in 2019 the Legislature passed and the Governor signed Chapter 120 (SB 200, Monning) which established a new stream of dedicated funding totaling up to $130 million annually for safe and affordable drinking water. The legislation tasked the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) with administering the funding and overseeing efforts to implement both short‑ and long‑term solutions to persistent drinking water problems.

Implementing SB 200 represents a significant commitment of state funding and is intended to remediate serious health and safety problems. As such, ensuring the funding is meeting its intended outcomes and effectively improving conditions for vulnerable Californians is a high priority for the state. Earlier this year, SWRCB adopted a policy and expenditure plan for how it will approach implementing SB 200. This report provides an update for the Legislature on SWRCB’s decisions.

We begin by explaining the larger context for this expanded state initiative, including describing the drinking water problems that the new funding is intended to address. We also highlight areas in which important data—such as a full statewide assessment of drinking water needs and associated costs—is still pending, and describe previous state efforts related to drinking water. Next, we describe the components included in SB 200. We then review SWRCB’s stated priorities and proposals for allocating funding—both at a high level and specifically in 2020‑21—and explain how the program plans to measure its progress. We conclude by providing some comments about program implementation thus far, as well as by highlighting some issues we suggest the Legislature continue to monitor in the coming months and years to ensure statewide goals for improving access to drinking water are effectively achieved.

Background

Drinking Water Supposed to Meet Certain Safety Standards

Federal and State Laws Establish Water Quality Standards. The federal Safe Drinking Water Act was enacted in 1974 to protect public health by requiring that drinking water meet certain standards. These standards take into account the health risk, detectability, treatability, and costs of treatment associated with various pollutants. California has also enacted its own safe drinking water legislation to implement the federal law and establish additional state standards. (There are certain state drinking water standards which are more stringent than federal standards.) While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency enforces federal drinking water standards at the national level, it has granted most states—including California—the authority to implement and enforce federal drinking water requirements at the state level.

Most Californians Receive Water Through Public Water Systems. Drinking water comes from surface water—such as rivers—or water pumped from underground, and most California households receive their water via treatment and delivery systems operated by either local government agencies or privately owned utilities. A small proportion of residents receive water from private wells. Figure 1 on the next page identifies the different types of water systems in California. As described in the figure, a public water system is one that provides water for human consumption and has 15 or more service connections, or regularly serves at least 25 individuals daily at least 60 days out of the year. (A “service connection” is usually the point of access between a water system’s service pipe and a user’s piping.) In California, SWRCB—together with its regional water quality control boards—is responsible for regulating public water systems. The state contains approximately 7,400 public water systems, of which about 2,900 provide service to yearlong residents and are referred to as “community water systems.” (The remainder—transient and nontransient noncommunity public water systems—do not serve year‑round residents, and include schools, rest stops, and campgrounds.) The vast majority of California residents—over 90 percent—receive their water from about 400 large community water systems that have 3,300 or more service connections. Most community water systems are comparatively smaller, with about half of all systems having between 15 and 100 connections.

Figure 1

Types of Water Systems in California

|

|

|

|

|

|

Very Small Water Systems and Wells Are Not Regulated by the State. The exact number of “state small water systems” that serve between 5 and 14 connections is unknown but estimated at roughly 1,500. These systems are not regulated by SWRCB but are overseen by county health officers, however, the applicable water quality standards and testing requirements, oversight procedures, and data collection practices are significantly less robust than those for public water systems. The water quality conditions of domestic wells—which supply water for an individual residence or up to four connections—are not regularly monitored by the state or local governments. Data suggest that between 1.5 million and 2.5 million Californians rely on domestic wells for their water.

Many Californians Lack Access to Safe and Affordable Drinking Water

Many Californians Lack Access to Drinking Water That Is Safe... Despite federal and state water quality standards, SWRCB estimates that over one million Californians currently lack access to safe drinking water. This is primarily because these residents receive their water from systems and domestic wells that do not consistently meet those established standards. Many of these systems and wells provide water that contains contaminants such as arsenic, nitrates, and/or 1,2,3‑Trichloropropane, all of which pose health risks for both children and adults. A 2019 analysis of data from SWRCB conducted by the California Health Care Foundation found that only 17 of California’s 58 counties had public water systems that all complied with state and federal drinking water standards, and that in 12 counties—including San Joaquin, Kern, and San Benito—more than 10 percent of residents had unsafe tap water.

…And Affordable. Besides suffering from water quality problems, some Californians also struggle to afford access to safe drinking water. Pursuant to Chapter 662 of 2015 (AB 401, Dodd), SWRCB recently completed a report looking into how the state might implement a low‑income water rate assistance program. The report cites that, adjusting for inflation, the average California household paid around 45 percent more per month for drinking water services in 2015 than in 2007. This has created an affordability challenge for many low‑income households that have not seen a commensurate increase in their incomes—in fact, when adjusting for inflation, the average incomes for the bottom quartile of California income earners decreased by 9 percent between 2007 and 2015. The study also reports that less than 20 percent of the state’s low‑income population who are served by community water systems currently receive benefits from a low‑income rate assistance program. Additional research conducted in 2014 found that in some California cities, one in five households was spending almost 5 percent of their annual income on water. (Federal and state programs have adopted policies indicating that water rates exceeding the range of 1.5 percent to 2.5 percent of household income may create affordability challenges.) As we discuss later, these affordability challenges likely have been exacerbated for some households in recent months by the spike in unemployment rates resulting from the economic slowdown and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic.

Drinking Water Issues Worsened During Recent Drought. In addition to long‑standing water quality issues, acute water shortages emerged in certain areas of the state during the severe drought that occurred between 2011 and 2016. In particular, low precipitation combined with increased rates of pumping for agriculture caused groundwater levels to drop significantly in many parts of the Central Valley. This in turn caused some wells serving residential homes to dry up or become affected by contaminants that emerged in the underlying aquifers. Research suggests at least 1 in 30 of the domestic and agricultural wells constructed after 1975 ran dry between 2013 and 2018, and data from the Department of Water Resources indicates that at least 2,760 households have experienced water shortages since 2013. In many areas of the state, pre‑drought groundwater levels have not yet recovered and wells are still dry.

Communities Served by Small Water Systems Confront Greatest Challenges. Smaller water systems face the most significant struggles in delivering safe and affordable drinking water. This is primarily because their small rate‑payer bases render them less able to afford to undertake necessary water quality upgrades or pay the infrastructure costs necessary to consolidate with other water systems in their region. Moreover, even if these small water systems can qualify for one‑time grants to fund needed upgrades, they often lack sufficient technical, managerial, and financial resources to operate and maintain their systems on an ongoing basis. SWRCB found that in 2019, while only about 5 percent of the total 7,403 active public water systems had one or more violations of water quality standards, over 91 percent of those that failed to comply contained fewer than 500 service connections. The aforementioned SWRCB AB 401 water rate assistance study also found that smaller systems face greater affordability challenges than larger systems. Specifically, the water systems with the highest percentages of customers from households earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level are mostly small or very small systems, and those systems typically lack the means to fund a low‑income water rate assistance program.

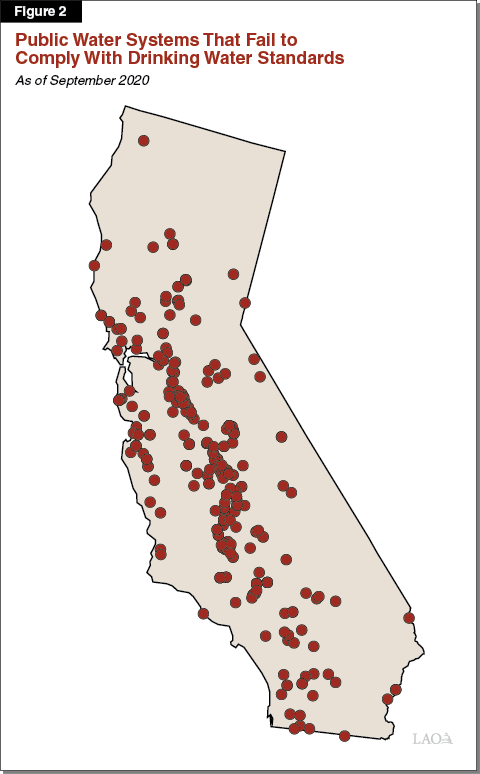

Drinking Water Problems Concentrated in Central Valley. Many of the areas that experience problems with their drinking water are small farmworker communities located in California’s Central Valley. Figure 2 shows a map of the public water systems that violated one or more federal or state primary drinking water standard as of September 2020. This means that testing revealed the systems’ water contained at least one contaminant at amounts that exceeded the maximum levels set by the standards, and that SWRCB undertook enforcement actions (such as issuing a compliance order or fine). As shown, while violations occur statewide, they are concentrated in systems in the San Joaquin region. (Because comparable data are not readily available, the map excludes information for state small systems and domestic wells that are not regulated by the state.)

Most Drinking Water Challenges Affect Lower‑Income Communities. Research has also found that many of the affected communities contain high proportions of residents earning lower incomes. For example, analysis by researchers from the University of California (UC), Davis found that low‑income communities located outside city boundaries are served by “a fragmented patchwork of small and often underperforming water systems that result in uneven access to safe drinking water.” A separate analysis of water quality data in the San Joaquin Valley found that community water systems serving predominantly socioeconomically disadvantaged communities had both higher levels of arsenic and higher odds of violating water quality standards. Moreover, a study by the Pacific Institute found that of the public water systems in California that experienced or were on the verge of experiencing water shortages during the recent drought, two‑thirds served a “disadvantaged” community and nearly one‑third served a “cumulatively burdened” community. (The researchers defined communities as disadvantaged if they had a median household income of less than 80 percent of the state median, and cumulatively burdened if they ranked in the top one‑quarter of census tracts in the state for environmental burdens and socioeconomic vulnerability.)

Latino Residents Are Disproportionately Affected by Lack of Safe Drinking Water. In addition to socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity are important factors in understanding who has access to safe drinking water in the San Joaquin Valley. For example, the aforementioned UC Davis study reports that Hispanics/Latinos make up a much larger percentage of the population served by out‑of‑compliance community water systems (57 percent), as compared to Caucasians (36 percent). Moreover, research has indicated that Hispanics/Latinos in the San Joaquin Valley are disproportionately exposed to higher levels of nitrates and this exposure is particularly prevalent in smaller water systems. These trends are partially due to historical housing discrimination practices that restricted which racial groups could live and purchase homes in the incorporated cities that contained larger and more developed water systems. These practices forced many residents of color to concentrate in rural and unincorporated areas that are dependent on wells and less sophisticated water systems.

Full Accounting of Drinking Water Problems and Costs Unknown

Available Data Are Incomplete. SWRCB has developed a list of potential solutions and cost estimates for addressing problems at public water systems that currently fail to meet water quality standards. The board has also begun developing a list of potential capital projects and temporary solutions and associated costs for some state small systems at which deficiencies have been identified. As of July 2020, the combined costs for these identified potential solutions totaled roughly $900 million. However, this does not represent a full accounting of what it will cost to address all of the drinking water systems and wells in the state that fail to, or are at risk of failing to, provide safe and affordable drinking water. Rather, these data are limited to the systems that have either been identified by or have already requested funding from SWRCB. They therefore exclude at‑risk public water systems that have not yet been flagged by SWRCB or requested funding, those for which potential short‑ or long‑term solutions have not yet been identified, and state small systems and domestic wells about which the state has not historically collected water quality data.

Pending Needs Assessment Will Help Inform State’s Efforts. SWRCB is in the process of conducting a comprehensive needs assessment to inform the state’s drinking water efforts. This assessment, which was partially funded with $3 million from the General Fund appropriated in the 2018‑19 Budget Act, will be completed by June 2021. The assessment will (1) identify and map systems that may currently comply with but are at risk of not meeting water quality standards, (2) identify state small systems and domestic wells that are violating or at risk of violating water quality standards, and (3) develop a cost analysis for interim and long‑term solutions to the identified problems. Because limited information is available to address the second component of the assessment, SWRCB is developing a map of aquifers that are at high risk of containing contaminants that exceed safe drinking water standards and are used or likely to be used as a source of drinking water for state small water systems or domestic wells. This map will be completed by January 2021.

Prior State Efforts to Address Drinking Water Problems

State Law Establishes Right to Safe Water in California. In 2012, the Legislature passed and Governor Brown signed Chapter 524 (AB 685, Eng), which established the state policy that “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.” This legislation made California the first state in the country to legally recognize the human right to water. Chapter 524, however, did not expand any obligation of the state to provide water or require that additional state resources be spent to ensure that the policy’s intent was achieved.

Expanded State Authority to Address Poorly Performing Water Systems. The Legislature has provided SWRCB with increased powers to address drinking water issues. Specifically, Chapter 27 of 2015 (SB 88, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) authorized SWRCB to require certain water systems that consistently fail to provide safe drinking water to consolidate with, or receive an extension of service from, another public water system. Additionally, Chapter 773 of 2016 (SB 552, Wolk) and Chapter 871 of 2018 (AB 2501, Chu) provided SWRCB with the authority to appoint an administrator to provide either broad management responsibilities or specific duties for a public water system in a disadvantaged community if needed to help the system consistently provide safe and affordable drinking water.

Some Funding Provided to Address Drinking Water Issues. The state and federal governments have provided some funding to address drinking water issues over the past several years, including:

- Voter‑Approved General Obligation Bonds. California voters have approved several general obligation bonds that have included funding to address drinking water issues, primarily to provide grants for capital improvement projects. Most of the funding that is currently available is from the two most recent natural resources bonds. Proposition 1 (2014) included $720 million to prevent and cleanup contamination of groundwater used for drinking water and $260 million for public water system infrastructure improvements, and Proposition 68 (2018) included $250 million for safe drinking water projects and $80 million to treat and remediate contaminated groundwater used for drinking water. Nearly all of this funding has been appropriated by the Legislature and SWRCB is engaged in allocating grants.

- Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF). The DWSRF is primarily used to finance local water infrastructure projects through grants and low‑interest loans, and also supports SWRCB staff to provide technical assistance and conduct regulatory activities. DWSRF funding comes from federal grants, revolving principal and interest repayments, and investment earnings. (The state has also used portions of the aforementioned bonds to meet federal requirements for state matching contributions to the DWSRF.) Based on federal guidelines, financing is prioritized for projects that (1) address the most serious human health risks, (2) are necessary to comply with federal Safe Drinking Water Act requirements, and (3) assist public water systems in small disadvantaged communities. In recent years, federal grants have averaged about $90 million annually.

- General Fund and Special Funds. From 2013‑14 through 2019‑20, the Legislature provided several one‑time appropriations totaling roughly $200 million for drinking water‑related activities from the General Fund and the State Water Quality Control Fund Clean Up and Abatement Account. These funds were primarily to address urgent needs—in part to respond to drought conditions—such as providing emergency drinking water supplies, connecting smaller systems to larger ones that had more stable sources of water, and replacing wells.

Legislature Created Drinking Water Fund and Program

Overview

Safe and Affordable Drinking Water (SADW) Fund Established in 2019. To help address the long‑standing issues around access to safe and affordable water, SB 200 established the SADW Fund in the State Treasury, along with a source of funding and parameters for how it must be used. The legislation states that the fund’s intended goals are to “help water systems provide an adequate and affordable supply of safe drinking water in both the near and long terms” and to “bring true environmental justice to our state and begin to address the continuing disproportionate environmental burdens in the state by creating a fund to provide safe drinking water in every California community, for every Californian.” As highlighted in Figure 3, SB 200 requires that SADW Fund monies be prioritized for three broad objectives, including a focus on serving disadvantaged communities and low‑income households.

Figure 3

Primary Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Fund Expenditure Priorities

|

|

|

Funding

State Will Provide Up to $130 Million Annually to SADW Fund. Senate Bill 200 requires that each year beginning in 2020‑21 and through 2029‑30, 5 percent of revenues from the state’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) must be transferred into the SADW Fund, up to an annual total of $130 million. The GGRF consists of revenues generated from the state’s cap‑and‑trade auctions. The legislation authorized that the transfer to the SADW Fund be continuously appropriated from the GGRF, meaning it is not dependent on an annual budget act appropriation by the Legislature. Because the amount of revenue the cap‑and‑trade auctions generate can vary, however, in some years 5 percent of GGRF revenues may total less than $130 million. Senate Bill 200 requires that beginning in 2023‑24 and through 2029‑30, if the amount automatically transferred from the GGRF to the SADW Fund does not total $130 million, sufficient monies from the General Fund shall also be transferred to make up the difference.

While SB 200 authorized the transfer from the GGRF to the SADW Fund to begin in 2020‑21, the Legislature provided the first year of comparable funding in 2019‑20. Specifically, the 2019‑20 budget provided $100 million in GGRF and $30 million from the General Fund to SWRCB for activities to help water systems provide safe and affordable drinking water.

Program Could Be Partially Supported by Special Fund Loan in 2020‑21. Due in part to the economic slowdown caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic, the cap‑and‑trade auctions held in May 2020 and August 2020 generated less revenue than previous quarterly auctions. This creates some uncertainty about how much GGRF will be available to transfer to the SADW Fund in 2020‑21. (As noted, the provision requiring supplemental funding from the General Fund does not take effect until 2023‑24.) To make certain that the program is able to undertake expenditures totaling $130 million in this fiscal year, the Legislature authorized a one‑time loan from a different special fund as part of the 2020‑21 budget package. Specifically, Chapter 40 of 2020 (SB 115, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) allows the Director of Finance to transfer up to $130 million from the Underground Storage Tank Cleanup (USTC) Fund as a loan to the SADW Fund in 2020‑21 to help make up the difference should 5 percent of GGRF revenues fall short of that amount. (The USTC Fund—which has maintained a large balance in recent years—is administered by SWRCB and is used to clean up soil and groundwater contaminated by petroleum leaks from underground storage tanks.) The loan will need to be repaid to the USTC Fund by future GGRF revenues.

Based on the results of the August 2020 cap‑and‑trade auction, in the first quarter of 2020‑21 the SADW Fund will receive $20 million from GGRF and $12.5 million loaned from the USTC Fund—totaling $32.5 million, or one‑quarter of $130 million.

Program Administration

SWRCB Administers Drinking Water Fund and Program. Senate Bill 200 tasks SWRCB with administering the SADW Fund. The board recently created the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) program, which will pair allocation of monies from the SADW Fund with funding from other sources such as bonds and DWSRF—as well as regulatory actions—to help struggling water systems provide safe drinking water to their customers. In combination, the 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 state budgets established 71 new positions for SWRCB to administer the SADW Fund and SAFER program, which will be supported by about $13 million annually from the SADW Fund. The board plans to implement SAFER program services through three of its divisions and offices: the Division of Drinking Water (to enforce compliance with federal and state laws), the Division of Financial Assistance (to administer grants and loans), and the Office of Public Participation (to facilitate community engagement and input).

Senate Bill 200 also requires SWRCB to form an advisory group to provide input into how the fund is allocated each year. The group must contain representatives from several categories of stakeholders, including: public water systems; local agencies; nongovernmental organizations; and residents served by state small water systems, domestic wells, and community water systems in disadvantaged communities. SWRCB convened this advisory group beginning in January 2020.

Activities

SADW Fund Can Be Used for Many Types of Activities. Figure 4 describes the types of activities SB 200 prescribes for using the SADW Fund. The fund is intended to complement SWRCB’s other programs and help “fill in gaps” to better address persistent problems faced by water systems. The other funding sources upon which SWRCB primarily relies to support drinking water activities—bonds and the DWSRF—generally are restricted for capital infrastructure projects. This is why, as highlighted in Figure 3, the SADW Fund is prioritized for uses other than capital construction projects. As shown in Figure 4, the SADW Fund can be used for a much broader suite of activities, including operations and maintenance costs, emergency water supplies, and appointed administrators.

Figure 4

Allowable Uses for the Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Fund

Pursuant to Chapter 120 of 2019 (SB 200, Monning)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Senate Bill 200 states that SWRCB can use the SADW Fund for grants, loans, contracts, or services, and defines eligible recipients as public agencies, nonprofit organizations, public utilities, mutual water companies, federally and state recognized California Native American tribes, administrators, and groundwater sustainability agencies.

Beginning Implementation of SB 200

Program Goals

SWRCB Identified Short‑ and Long‑Term Program Goals. Pursuant to a requirement contained in SB 200, in May 2020 SWRCB adopted a policy to guide its development of annual expenditure plans for the SAFER program. The policy lays out two short‑term goals for the program: (1) provide safe drinking water to more communities and people, more efficiently, and in less time, and (2) promote system consolidations and extensions of service. The stated long‑term goals are to (1) support permanent water system improvements and (2) build technical, managerial, and financial capacity to make systems safe, efficient, and sustainable. Because the program is intended to be both responsive and proactive, it will provide funding and services to address water systems that currently are out of compliance with water quality standards, as well those identified as being at risk of falling out of compliance. The policy also states that to increase efficiency and decrease administrative burdens, SWRCB will seek to promote regional‑scale solutions as opposed to a series of individual projects or services. For example, this could include funding the infrastructure needed for two small water systems to join a larger neighboring system rather than appointing multiple administrators and water treatment facilities to maintain each of those small systems separately. The funding categories for which monies from the SADW Fund will be used are described in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Categories for SADW Fund Expenditures

|

Category |

Examples of Funded Activities |

|

Emergency water supplies and interim solutions |

Emergency improvements or repairs to existing systems; provision of bottles, tanks, or filling stations for short‑term water supplies; temporary connections to safe water sources; and point‑of‑use water treatment systems. |

|

Technical assistance |

Training for water system staff, support in developing plans and grant applications, technical/managerial/financial capacity assessments, rate studies, financial audits, negotiation of consolidation agreements, and community outreach. |

|

Planning |

Project planning activities such as feasibility studies, engineering plans, and environmental permits. |

|

Construction |

Implementation of projects such as new wells, connections or extensions to other systems, or new water treatment facilities. |

|

Direct operations and maintenance support |

Temporary support for systems that are in the process of consolidating, such as covering revenue shortfalls until infrastructure upgrades have been completed and water rate adjustments have been made. |

|

Pilot projects |

Projects to help develop and test new approaches before wide‑scale implementation, including innovative water treatment technologies. |

|

Administrators |

Support for SWRCB‑appointed water system administrators. |

|

SWRCB staff |

Staff costs for administration and implementation of the SAFER program. |

|

SADW = Safe and Affordable Drinking Water; SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; and SAFER = Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience. |

|

Expenditure Plan

Expenditure Plan Identifies Specific Priorities for 2020‑21. Senate Bill 200 requires SWRCB to develop—and provide to the Legislature—an annual plan that describes how it intends to expend monies from the SADW Fund. SWRCB adopted its 2020‑21 Fund Expenditure Plan in July 2020 and identified four primary priorities for 2020‑21:

- Address emergency or urgent needs.

- Address community water systems and school water systems out of compliance with primary drinking water standards, with a focus on small disadvantaged communities.

- Accelerate consolidations for systems out of compliance, at‑risk systems, and state small water systems and domestic wells, with a focus on small disadvantaged communities.

- Address the needs of state small systems and domestic wells that are out of compliance with water quality standards.

Expenditure Plan Provides Details on How Funds Will Be Used. Figure 6 summarizes information from the Fund Expenditure Plan detailing how SWRCB used SADW funds in 2019‑20 and its planned expenditures for 2020‑21. As shown, in comparison to the prior year, the 2020‑21 plan distributes funds across a broader collection of activities, including to pay for SWRCB staff and to provide direct operations and maintenance support for systems that are in the process of consolidating. SWRCB will select projects to fund from submitted applications and staff‑identified needs. While the amounts displayed in the figure reflect planned expenditures, SWRCB has delegated authority to the Deputy Director of its Division of Financial Assistance to make adjustments across expenditure categories over the course of the year based on evolving needs. Below, we provide detail on the largest expenditure categories.

- Construction. As noted earlier in Figure 3, SB 200 requires that the SADW Fund be prioritized for noncapital projects. Construction, however, is the largest proposed spending category for 2020‑21—$49 million, or 38 percent of the total. The plan states that these SADW Fund monies will help make up funding shortfalls to enable completion of larger scale projects for which available grants from other sources—such as bonds—are limited by statutory funding caps.

- Technical Assistance. Just over half of the 2019‑20 expenditures ($67.2 million) was spent on technical assistance activities, dropping to a proposed $30 million in 2020‑21. As highlighted in Figure 5, these funds could support a wide variety of activities to help local systems increase their technical, financial, and managerial capacity, and to take the necessary steps to enable them to implement projects.

- Emergency Water Supplies and Interim Solutions. As shown in the figure, SWCRB also plans to increase SADW Fund spending on responding to emergencies and providing interim water supplies until permanent solutions can be implemented—$7.4 million in 2019‑20 compared to $19 million in 2020‑21. According to the plan, the 2020‑21 budgeted amount can provide more than 9,000 households with bottled water (at $75 per month per household) for two years, with $2.5 million remaining available to address unforeseen emergencies. Even with this increase in SADW Fund spending, the program likely will not be able to fully fund the identified need for emergency supplies and interim solutions, which SWRCB has estimated at a total of around $400 million. The plan states that SWRCB will give priority to requests from systems that serve small disadvantaged communities and face the greatest threats to public health and safety, including those that are experiencing elevated hexavalent chromium levels in their water. (SWRCB is in the process of adopting an enforceable water quality standard for hexavalent chromium. Elevated levels of this contaminant currently cause public health risks, but affected systems are not yet flagged as being out of compliance.)

- SWRCB Staff. The figure highlights that SWRCB plans to dedicate a notable proportion of the SADW Fund—$12.8 million, or roughly 10 percent of the total—to support 71 staff working on SAFER program activities. (This compares to $3.4 million that was provided from the General Fund on a one‑time basis for 23 positions to initiate the program in 2019‑20.) While SB 200 caps the amount of SADW Fund monies that can be used for administrative tasks at 5 percent, the proposed totals also include staff who will be working on implementing the program. Proposed implementation tasks include working with water systems to develop potential solutions, conducting public outreach, providing legal reviews associated with system consolidation orders, and developing plans and assessments. In contrast, administrative tasks include accounting work, grant and contract administration, and information technology support. SWRCB indicates that 43 positions and about $8 million are associated with implementation tasks while 28 positions and roughly $4.8 million are associated with administrative tasks.

Figure 6

SWRCB Expenditure Plan for SADW Fund

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Construction |

$53.8 |

$49.0 |

|

Technical assistance |

67.2 |

30.0 |

|

Emergency water supplies and interim solutions |

7.4 |

19.0 |

|

SWRCB staff |

—a |

12.8 |

|

Direct operations and maintenance support |

— |

10.0 |

|

Planning |

1.6 |

6.0 |

|

Pilot projects |

— |

3.2 |

|

Totals |

$130.0 |

$130.0 |

|

aSWRCB received a separate one‑time appropriation of $3.4 million from the General Fund to support staff in 2019‑20. SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board and SADW = Safe and Affordable Drinking Water. |

||

Other Funding Sources Available for Appointed Administrators in 2020‑21. Notably, SWRCB does not plan to expend SADW Fund monies to support the costs of appointing administrators to take over struggling water systems in the current fiscal year, despite the Fund Expenditure Plan mentioning that the board intends to “gradually ramp up” use of this option in 2020‑21. This is because as of July 2020, $10 million from the General Fund remained available for this purpose from Chapter 1 of 2019 (AB 72, Committee on Budget). SWRCB adopted an Administrator Policy Handbook in September 2019 describing when and how it might appoint an administrator to take over responsibilities in a public water system. The Expenditure Plan states that SWRCB anticipates being able to appoint at least five administrators in 2020‑21.

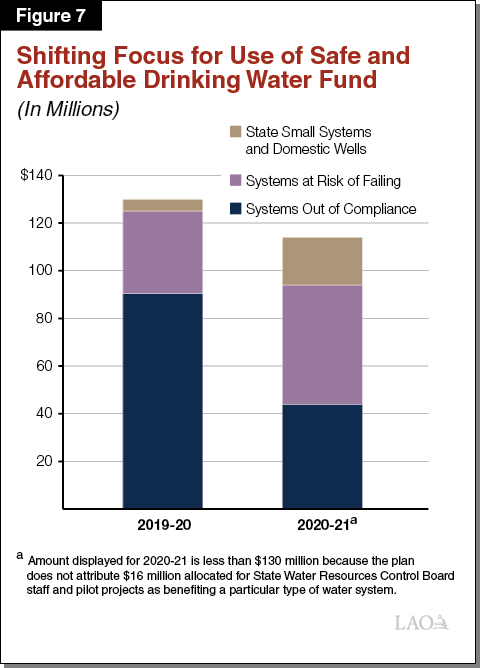

Increasing Emphasis on Addressing Needs of At‑Risk Systems and Wells. The differences in planned SADW Fund expenditures across years displayed in Figure 6 also reflect a shift in the types of water systems to be targeted for financial assistance. Specifically, as shown in Figure 7, $90 million (70 percent) of SADW Fund expenditures for water systems in 2019‑20 were for grants, loans, and services benefiting public water systems that are currently failing to comply with drinking water standards. In 2020‑21, however, SWRCB plans to place additional emphasis on also addressing the needs of systems identified as being at risk of falling out of compliance, as well as state small systems and domestic wells in areas at high risk of having contaminated aquifers. Specifically, the board plans to spend a larger share of funding—totaling 61 percent—on at‑risk systems ($50 million) and state small systems and domestic wells ($20 million). (The amount displayed for 2020‑21 is less than $130 million because the plan does not attribute the $16 million for SWRCB staff and pilot projects as benefiting a particular type of water system.)

Expenditure Plan Establishes Threshold for Defining Affordability. The Fund Expenditure Plan outlines approaches for addressing concerns that drinking water is not currently affordable in some communities. Generally, the expectation is that a focus on certain strategies—such as system consolidations—will reduce water systems’ ongoing operations and maintenance costs, which in turn will allow systems to reduce the rates they must charge their customers. To help guide SWRCB’s work, the plan includes a working definition for what level of rates it considers “affordable.” Specifically, the plan adopts an affordability threshold of 1.5 percent of the community’s median household income. That is, community water systems that currently must charge fees exceeding 1.5 percent of the median household income for their areas in order to provide drinking water that meets state and federal standards are identified as having challenges providing affordable rates. Water systems in disadvantaged communities that exceed that threshold generally are eligible for grants, rather than loans, from the SAFER program. While acknowledging that data limitations make its list incomplete, the Fund Expenditure Plan identifies 190 community water systems that exceed the affordability threshold, of which 92 were identified as serving disadvantaged communities. (This analysis omitted 1,140 community water systems for which sufficient data were not available for SWRCB to estimate water rates.) SWRCB indicates that it will revisit the appropriateness of its current level and methodology for defining affordability in future annual expenditure plans, in consultation with the advisory group.

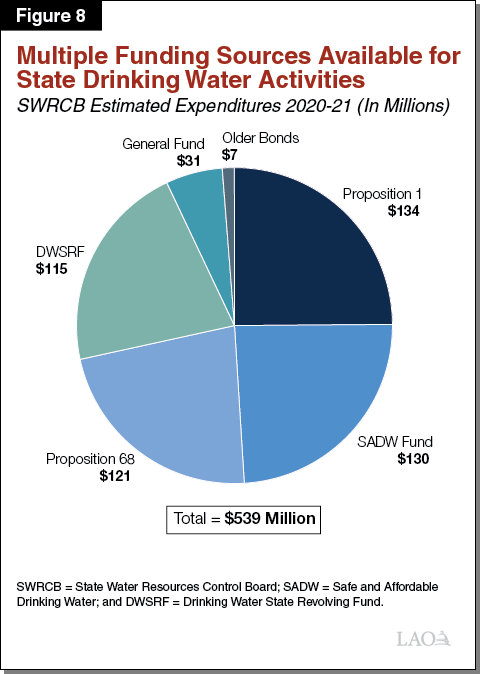

Other SAFER Program Funding Will Supplement SADW Fund. As discussed earlier, the SADW Fund is not the only source of funding available to address drinking water issues across California. Figure 8 summarizes how much SWRCB anticipates expending from various sources to support projects and activities in 2020‑21, totaling $539 million. These estimates suggest that the SADW Fund will make up roughly one‑quarter of the total funding for the SAFER program this year.

Performance Metrics

Board Has Adopted Performance Metrics to Gauge Progress. The expenditure policy that SWRCB adopted in May 2020 included eight metrics by which it will measure SAFER program performance each year, which are displayed in Figure 9. The Fund Expenditure Plan includes data for 2019‑20 and establishes new goals for what the SAFER program will accomplish in 2020‑21 for the first three metrics, which are displayed in Figure 10. The plan states that because the program has completed just one year of implementation, SWRCB does not yet have sufficient information to set appropriate goals for the other metrics. The board plans to gather baseline data in 2020‑21 for other categories—such as current application processing times and average pounds of carbon dioxide saved by type of project—to inform goal‑setting in expenditure plans for 2021‑22 and subsequent years. Both the accomplishments and goals reflect projects and solutions that were or will be funded by all SAFER program funding sources, not just the SADW Fund. As shown, in 2019‑20, the program ended up funding a greater number of communities than originally planned, and with a larger‑than‑anticipated focus on providing interim solutions. As discussed earlier, interim solutions include activities such as providing emergency water supplies, whereas long‑term solutions might include consolidating with other systems. The plan sets even more ambitious goals for the number of communities it will serve 2020‑21, in part due to increased SWRCB staffing capacity.

Figure 9

Annual Performance Metrics for SAFER Program

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SAFER = Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience. |

Figure 10

Initial SAFER Program Goals and Performance

Number of Communities

|

2019‑20 Goals |

2019‑20 Accomplishmentsa |

2020‑21 Goals |

|

|

Interim solutions |

75 |

173 |

150 |

|

Planning |

100 |

72 |

100 |

|

Long‑term solutions |

75 |

67 |

100 |

|

Totals |

250 |

312 |

350 |

|

aAs of June 2020. SAFER = Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience. |

|||

LAO Comments on Implementation and Oversight

Overall Assessment

Good Progress on Implementation Thus Far. Based on our review of the adopted Fund Expenditure Plan, SWRCB has shown positive progress in its initial year of administering the SADW Fund and implementing SB 200. Despite the logistical complications posed by the COVID‑19 pandemic—such as the shift to remote work and meetings—the board (1) formed and convened the advisory group; (2) met 2020 deadlines for adopting an expenditure policy and plan; and (3) is on track for delivering the required aquifer map, needs assessment, and 2021‑22 Fund Expenditure Plan by the associated 2021 time lines. Largely positive feedback provided at SWRCB’s official meetings—as well as our conversations with stakeholders—suggest that the program has also been effective at conducting outreach to and incorporating feedback from a wide array of interested parties.

Spending Priorities Reasonable. We find that the spending priorities SWRCB has identified are consistent with SB 200 and begin to put the state on a path to improving drinking water conditions in affected communities. In particular, we find that continuing to focus the majority of SADW Fund expenditures on nonconstruction activities like providing technical assistance and emergency water supplies is reasonable because many water systems are not yet ready to undertake the projects and permanent solutions that ultimately may be necessary and other funds are available for many capital projects. We consider the short‑term goals—providing timely water assistance to more communities and promoting actions that will lead to consolidations—and long‑term objectives—supporting permanent solutions and improving the operational capacity of local systems—identified by SWRCB to be prudent and appropriate. While data limitations have thus far limited SWRCB’s ability to identify and respond to the needs of state small systems and domestic wells, the forthcoming needs assessment should aid in those efforts, and expanding the program’s focus to those systems makes sense given the large numbers of residents they serve.

Continued Legislative Oversight Is Important

While we view SWRCB’s implementation progress positively thus far, much work remains to be accomplished in order to achieve the state’s goal of ensuring all Californians have access to safe and affordable drinking water. To ensure the SAFER program is implemented effectively and struggling drinking water systems are improved, the Legislature will want to carefully monitor SWRCB’s ongoing efforts and assess whether additional legislative actions are warranted. Questions that we believe merit the Legislature’s particular oversight in the coming months and years are summarized in Figure 11 and discussed in greater detail below.

Figure 11

Key Legislative Oversight Questions for Ensuring Access to

Safe and Affordable Drinking Water

|

|

|

|

|

How Well Is the SAFER Program Meeting Its Objectives for Expanding Access to Safe and Affordable Drinking Water? As described in Figure 9, SWRCB has adopted metrics which it will track and report in its annual Fund Expenditure Plans. Beginning in 2021, these plans must be submitted to the Legislature annually every March. The Legislature can use these performance metrics to monitor SB 200 implementation progress. Should the Legislature observe that SWRCB is regularly failing to meet the annual goals it has established, it may be an indication that additional legislative oversight or action could be merited. For example, if in a given year SWRCB plans to implement projects and solutions in 350 communities but only ends up serving 250, the Legislature may want to investigate what obstacles are impeding progress. Information reported in conjunction with these metrics could also highlight areas of concern for the Legislature. For example, if the number of communities remaining out of compliance remains comparably high across multiple years despite significant investments in solutions, this could indicate a growing problem. Additionally, if the time to fully execute projects seems excessive—leaving communities without safe water for many years even after problems, solutions, and funds have been identified—the Legislature may want to investigate what barriers are preventing timely progress. The Legislature may also want to weigh in if it believes that SWRCB is not setting sufficiently ambitious annual goals for these metrics and improving drinking water access.

Does the State Need Additional Information to Assess the Performance of the SAFER Program? The Legislature may want to consider whether additional information that will not be reported through the established metrics might be important to ensure the objectives of SB 200 are being met. For example, while SWRCB’s metrics consider how many communities are provided projects and attain compliance with water quality standards, they do not speak to how many people or households are on a path to receiving or have gained access to clean drinking water. Given that providing safe and affordable drinking water to more Californians is the ultimate goal of the program, this seems an important measure to assess. Moreover, none of the performance metrics directly address the issue of affordability and assessing how effective SADW Fund expenditures might be at lowering exorbitant water rates. If the Legislature needs additional data to adequately assess the degree to which SB 200 implementation is meeting its goals, it could request that SWRCB collect and report additional information.

How Well Is the SAFER Program Addressing Disproportionate Impacts on California’s Latino Population? As discussed earlier, access to safe drinking water disproportionately affects California’s low‑income and Latino residents. Because SB 200 prioritizes funding for disadvantaged communities, the Legislature can have some certainty that funded projects will help address the drinking water needs of lower‑income Californians. However, SWRCB does not currently collect data on racial disparities in access to safe drinking water. The Legislature may want to request that SWRCB collect and report data on the degree to which Latino residents are gaining access to safe drinking water from the SADW Fund investments, given research suggesting they have been disproportionately affected by shortages and contaminants compared to other groups. Should such data reveal that SAFER program investments and projects are not significantly rectifying the existing inequities across racial and ethnic groups, the Legislature may want to provide additional direction on how SADW Fund monies should be prioritized and how community outreach efforts may need to be expanded.

How Will the Program Adjust if Funding Is Lower Than Anticipated in the Coming Years? Should GGRF revenues not be sufficient to support full funding for the SADW Fund in 2021‑22 or 2022‑23, the Legislature will need to decide whether to provide supplemental funding from a different source. (As noted, beginning in 2023‑24, SB 200 requires that the General Fund provide a backfill if 5 percent of annual GGRF revenues total less than $130 million.) While the Legislature authorized a loan from the USTC Fund to ensure the SADW Fund receives $130 million in 2020‑21, that fund likely will not be able to support a similar loan in future years. If the state’s fiscal condition and other spending priorities preclude it from providing full funding for the SADW Fund in the coming years, SWRCB will need to determine how to prioritize available funds for the program. The Legislature may want to provide input into that process to reflect its particular priorities. For example, if funding is limited, the Legislature could direct SWRCB to place a greater emphasis on addressing immediate health and safety needs as compared to undertaking longer‑term solutions.

What Are Statewide Drinking Water Needs and How Well Aligned Is Available Funding to Meet Those Needs? Until the pending needs assessment clarifies the extent of current drinking water problems, the state cannot fully assess how quickly the SADW Fund and SAFER program will be able to address those deficiencies. Depending upon the magnitude of the estimates identified in the assessment, the Legislature may want to reassess its annual funding commitment to the SADW Fund. For example, if estimates suggest that $130 million annually (together with other SAFER program funding sources) through 2029‑30 will be more than enough to meet the state’s drinking water goals, the Legislature may want to consider amending statute to provide a lesser amount of GGRF and General Fund for the SADW Fund, at least for a couple of years. Such an approach might be particularly helpful to balancing the state budget in the near term if California continues to face a reduction in fiscal resources. In contrast, if the needs assessment indicates that the costs of ensuring safe and affordable drinking water for all Californians will greatly exceed the amount of funding that has been identified for the SAFER program over the next ten years—which is a more likely scenario, given the number of systems and wells about which water quality data are still lacking—the Legislature may want to identify additional funding options for achieving its objectives. For example, the Legislature could direct additional existing state funding for this program or consider raising new revenues.

Emerging Issues Could Complicate State’s Efforts

The SADW Fund is intended to help the state make progress in expanding access to safe and affordable drinking water to the estimated one million Californians who currently lack this human right. However, certain factors have the potential to worsen existing drinking water issues in some communities. These emerging issues—including continued groundwater pumping, drought, and COVID‑19—could counteract the progress of the SAFER program by exacerbating the statewide conditions the program is working to improve.

Groundwater Pumping Practices Place Additional Water Systems at Risk of Failing. As the state continues to work on identifying the systems and wells that currently fail to produce safe drinking water, recent research has raised concerns that changing conditions could put even more communities at risk. Specifically, a June 2020 report by The Water Foundation suggests that between 4,000 and 12,000 domestic drinking water wells are at risk of failing by 2040 if significant groundwater pumping continues in San Joaquin Valley basins that are already critically depleted. The report estimates this will cause between roughly 46,000 and 127,000 people to lose some or all of their primary water supply over the next two decades. Moreover, the researchers found that many of the plans developed pursuant to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA)—which are intended to help bring the groundwater in these basins back to sustainable levels—would not prevent these impacts. That is, many of the plans reviewed by the researchers set goals for “sustainable” minimum groundwater thresholds that could allow thousands of additional domestic wells to go dry. Additional reviews by UC Davis researchers found that the majority of these initial SGMA‑required Groundwater Sustainability Plans do not adequately consider how drinking water stakeholders could be impacted by the criteria they set for water quality and water levels, but rather concentrate on potential impacts to other types of water users. In light of these concerns, the Legislature may want to conduct additional oversight—such as through hearings or information requests—to ascertain how the Department of Water Resources and SWRCB are addressing these issues through their implementation and enforcement of SGMA.

Drought Conditions Could Cause Additional Wells to Go Dry. In addition to potential impacts from continued groundwater pumping, the prospect of an emerging drought has also raised concerns about the vulnerability of some existing wells and water systems, particularly in light of the significant number of communities that lost water during the last drought. The SAFER program’s focus on identifying and assisting at‑risk water systems and wells is intended to help ameliorate these potential vulnerabilities. If the state continues to experience below‑average precipitation patterns in the coming years, however, the Legislature will want to conduct oversight to ensure SWRCB’s efforts are adequate at proactively addressing communities in danger of losing access to safe drinking water.

COVID‑19 Pandemic Could Impact Vulnerable Households and Drinking Water Systems. The pandemic‑caused recession has the potential to interact with drinking water in two key ways, both of which may merit legislative action as conditions evolve. First, the economic slowdown and associated job losses could make it more difficult for certain households to be able to afford to pay their water bills. In April 2020, the Governor issued an executive order imposing a moratorium on water shut‑offs due to unpaid bills, but how long this order will last and the manner in which struggling households ultimately may be expected to repay money that is owed are still unclear. Second, some water systems likely are experiencing lower revenues—as a result of unpaid bills and less commercial water usage—that may affect their ability to continue service and maintain affordable rates.

How widespread or severe these challenges might be for households and water systems across the state is still unknown. A national report published in April 2020 estimated that, in aggregate, the drinking water sector could experience a 17 percent negative financial impact—primarily from lost revenues—associated with the COVID‑19 pandemic. SWRCB is undertaking a survey of water systems in California to try to ascertain how they have been impacted by changing conditions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, initial survey responses indicate that small water systems (with fewer than 1,000 connections) are more likely to experience revenue losses that make up a larger share of their budgets compared to larger systems which have greater revenue bases and cash reserves. The degree to which these funding shortfalls ultimately impact water rates and affordability remains to be seen.

Conclusion

Enacting SB 200 and establishing the SADW Fund in 2019 represented important steps in California’s path to ensuring that all of its residents have access to safe and affordable drinking water. One year later, SWRCB has made good progress in establishing spending priorities, beginning to allocate funds and execute projects, and collecting essential data to identify the communities that should be targeted for improvements. However, the state is still in the very early stages of implementation. Given the serious threats to public health, safety, and environmental justice posed by existing drinking water deficiencies, the Legislature will want to continue conducting robust oversight over how efforts to rectify these conditions proceed.

Research Citations

American Water Works Association and Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies (2020). “The Financial Impact of the COVID‑19 Crisis on U.S. Drinking Water Utilities.”

Balazs, C., Morello‑Frosch, R., Hubbard, A., Ray, I. (2011). “Social Disparities in Nitrate‑Contaminated Drinking Water in California’s San Joaquin Valley.” Environmental Health Perspectives 119:9.

Balazs et al. (2012). “Environmental justice implications of arsenic contamination in California’s San Joaquin Valley: a cross‑sectional, cluster‑design examining exposure and compliance in community drinking water systems.” Environmental Health 11:84.

Dobbin, K., Bostic, D., Kuo, M., Mendoza, J. (2020). “SGMA and the Human Right to Water: To what extent do submitted Groundwater Sustainability Plans address drinking water uses and users?” Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior, UC Davis.

Feinstein, L., Phurisamban, R., Ford, A., Tyler, C., Crawford, A. (2017). “Drought and Equity in California.” The Pacific Institute.

Jasechko, S., Perrone, D. (2020) “California’s Central Valley Groundwater Wells Run Dry During Recent Drought.” Earth’s Future, Volume 8, Issue 4.

London et al. (2018). “The Struggle for Water Justice in California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Focus on Disadvantaged Unincorporated Communities.” Davis, CA: UC Davis Center for Regional Change.

United States Conference of Mayors (2014). “Public Water Cost Per Household: Assessing Financial Impacts of EPA Affordability Criteria in California Cities.”

The Water Foundation (2020). “Groundwater Management and Safe Drinking Water in the San Joaquin Valley; Analysis of Critically Over‑drafted Basins’ Groundwater Sustainability Plans.”