LAO Contact

February 2, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Analysis of Major UC Proposals

Summary

Brief Covers Major University of California (UC) Proposals. This brief focuses on the Governor’s proposals for UC base support, enrollment, and deferred maintenance. Base increases and enrollment growth account for nearly all new proposed ongoing spending for UC, with deferred maintenance accounting for about one‑third of proposed one‑time spending.

Legislature Could Tie Base Augmentation More Closely to Anticipated Cost Increases. The Governor proposes providing UC a $201 million (5 percent) General Fund base increase in 2022‑23. Coupled with additional tuition revenue (an estimated $45 million), UC would have $246 million available to cover core operating cost increases. We recommend the Legislature move away from providing UC arbitrary base increases and instead tie augmentations to anticipated cost increases. For illustration, at the Governor’s proposed funding level, the Legislature could cover UC’s nonsalary cost increases (including employee benefits and debt service) as well as a nearly 4 percent increase in UC’s salary pool.

UC’s Enrollment Plan Creates Difficult Choices for Legislature. Intended to implement enrollment agreements established last year, the Governor proposes $99 million to grow UC resident undergraduate enrollment by 7,132 students in 2022‑23. (This number includes base growth of 6,230 students, coupled with replacing 902 nonresident students with resident students.) Despite the Governor’s proposal, UC indicates it is planning to grow by only approximately 2,000 resident undergraduate students in 2022‑23. UC indicates its plan to grow less in 2022‑23 is due to higher‑than‑expected enrollment in 2020‑21. We recommend the Legislature treat UC’s planned 2,000 student growth in 2022‑23 as a starting point (at a cost of $43 million). The Legislature could provide funding above this amount if it wanted to fund over‑target enrollment from 2020‑21. Though funding past over‑target enrollment runs counter to recent state practice, the Legislature could consider making an exception this year, as the pandemic might have created more uncertainty with enrollment planning.

Facility Maintenance Remains Underfunded at UC. The Governor’s budget proposes $100 million one time for deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects at UC. UC reports having an existing maintenance backlog of $7.3 billion and an annual ongoing capital renewal need of around $1.2 billion to keep the backlog from growing. For comparison, UC estimates spending $291 million in 2019‑20 on maintenance. Given the substantial backlog facing UC, deferred maintenance is a reasonable use of one‑time funding. One‑time funding, however, does not address the ongoing problem of underfunding in this area. We encourage the Legislature to begin developing a long‑term strategy for addressing UC’s ongoing facility maintenance needs.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on the University of California (UC). UC is one of California’s three public higher education segments. In contrast to campuses at the other two segments—the California State University (CSU) and the California Community Colleges (CCC)—UC’s ten campuses are research universities. Nine of UC’s campuses enroll undergraduate, graduate, and professional school students across a range of disciplines, whereas a tenth campus enrolls graduate health science students only. Campuses offer degrees through the doctoral level. This brief is organized around the Governor’s major 2022‑23 budget proposals for UC. The first section of the brief provides an overview of the Governor’s UC budget package. The remaining three sections of the brief focus on base support, enrollment, and deferred maintenance, respectively. We anticipate covering other UC proposals in subsequent products.

Overview

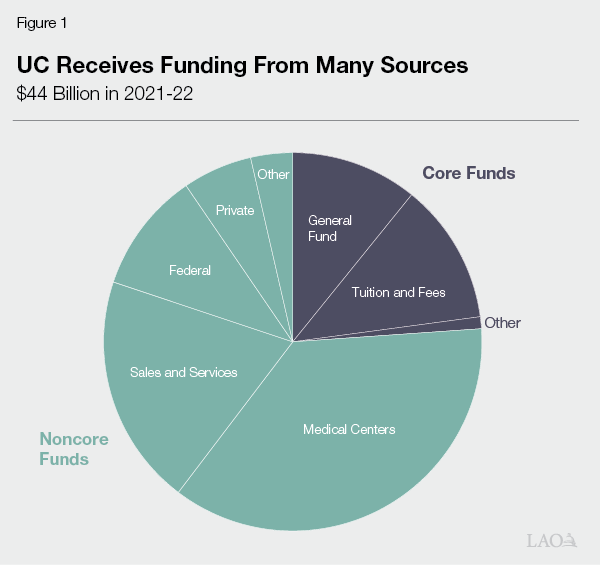

UC Budget Is $44 Billion in 2021‑22. Though having the lowest level of state support, the fewest campuses, and the least student enrollment, UC has the largest budget of the three public higher education segments—with total funding greater than the CSU and CCC budgets combined. As Figure 1 shows, UC receives funding from a diverse array of sources. In most years, the Legislature focuses its budget decisions around UC’s “core funds.” Core funds at UC primarily consist of state General Fund and student tuition revenue, with a small portion coming from other sources (including overhead funds from federal and state research grants). UC uses its core funds to support its core mission of undergraduate and graduate education, along with certain state‑supported research and outreach programs.

Ongoing Core Funding Increases by $392 Million (4 Percent) Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 2 shows, most of the increase comes from the General Fund, with a smaller increase from student tuition and fees. Ongoing General Fund would increase from $4 billion in 2021‑22 to $4.3 billion in 2022‑23, reflecting an increase of $308 million (7.7 percent). By comparison, we estimate tuition would grow from $5.3 billion to $5.4 billion, reflecting an increase of $148 million (2.8 percent). In 2022‑23, tuition revenue is expected to grow both due to increases in tuition charges and enrollment growth. Under the Governor’s budget, we estimate ongoing core funding per student to increase by 2.6 percent.

Figure 2

Largest Portion of UC Core Fund Increase

Comes From General Fund

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

General Fund |

$3,465 |

$4,010 |

$4,318 |

$308 |

7.7% |

|

Tuition and fees |

4,935 |

5,295 |

5,443a |

148 |

2.8 |

|

Lottery |

43 |

51 |

50 |

—b |

—b |

|

Other core fundsc |

395 |

395 |

395 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$8,838 |

$9,750 |

$10,207 |

$456 |

4.7% |

|

FTE studentsd |

289,314 |

293,728 |

301,377 |

7,649 |

2.6% |

|

Funding per student |

$30,549 |

$33,196 |

$33,868 |

$672 |

2.0% |

|

aEstimate from Legislative Analyst’s Office. The Department of Finance’s original estimate did not reflect the administration’s enrollment growth proposal. bAmount is less than $500,000 or 0.05 percent. cIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. dReflects total resident and nonresident enrollment in undergraduate, graduate, professional, and health science programs. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Governor Has Several UC General Fund Priorities. As Figure 3 shows, unrestricted base increases and enrollment growth account for the bulk of the proposed new ongoing funding. The Governor’s budget also provides $295 million in one‑time funding for specified initiatives, with the largest amounts for certain climate‑related initiatives as well as deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects.

Figure 3

Governor Proposes New UC Ongoing and

One‑Time Spending

General Fund Changes in 2022‑23 Over Revised 2021‑22 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Changes |

|

|

Base increase (5 percent) |

$201 |

|

Resident undergraduate enrollment growth |

68 |

|

Nonresident enrollment reduction plana |

31 |

|

Foster youth programs |

6 |

|

UC Davis Firearm Violence Center |

2 |

|

Graduate medical education |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($308) |

|

One Time Initiatives |

|

|

Climate initiatives |

|

|

Seed and matching grants for applied research |

$100 |

|

Regional climate technology incubators |

50 |

|

Regional workforce and training hubs |

35 |

|

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

100 |

|

UC San Francisco Dyslexia Center |

10 |

|

Subtotal |

($295) |

|

Total |

$603 |

|

a In 2022‑23, UC would reduce its nonresident undergraduate enrollment at three campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) by a total of 902 students. It would backfill these slots with the same number of additional resident undergraduate students. |

|

UC Plans to Increase Tuition Charges in 2022‑23. In July 2021, the Board of Regents adopted a plan to increase resident and nonresident tuition charges over the next several years. For undergraduates, tuition and fee charges will be cohort based, with fee increases applied only to new students and held flat for continuing students. In contrast, tuition will increase annually for all graduate students. Generally, tuition increases will be pegged to a rolling three‑year average of the California consumer price index. Undergraduate charges, however, will increase by more than inflation the first few years of implementation (for example, 2 percentage points over inflation in 2022‑23). UC plans to initiate its new tuition policy in 2022‑23.

Governor Announces Multiyear Compact With UC. In addition to his 2022‑23 budget proposals for UC, the Governor has indicated his intention to continue providing UC with 5 percent base increases annually through 2026‑27. He also has indicated his interest in having UC pursue 18 expectations spanning six priority areas—increasing access for California students, improving student outcomes and equity, making UC more affordable for students, enhancing intersegmental collaboration, improving workforce alignment, and expanding online education. (The administration currently does not intend to codify these expectations.) The Department of Finance indicates that the administration could consider proposing smaller future base increases were UC not to make progress in meeting one or more of these expectations. We describe and assess the Governor’s multiyear compact with UC, as well as his multiyear agreements with CSU and CCC, in our publication The 2022‑23 Budget: Overview of Governor’s Higher Education Budget Proposals.

Base Support

In this section, we first provide background on UC’s operating costs and how UC generally covers its operating cost increases. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed base increase for UC as well as identify the additional tuition revenue expected to result from UC’s new tuition policy. We then assess the Governor’s proposal and make an associated recommendation.

Background

UC Has Several Core Operating Costs. As with most state agencies, UC spends the majority of its ongoing core funds (about 70 percent in 2020‑21) on employee compensation, including salaries, employee health benefits, retiree health benefits, and pensions. Beyond employee compensation, UC spends its core funds on other annual costs, such as paying debt service on its systemwide bonds, supporting student financial aid programs, and covering other operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). Each year, campuses typically face pressure to increase employee salaries at least at the pace of inflation, with certain other operating costs (such as health care, pension, and utility costs) also tending to rise over time. Though operational spending grows in most years, UC has pursued certain actions to contain this growth. For example, UC has pursued new procurement practices and energy efficiency projects with the aim of slowing associated cost increases.

UC Has Considerable Flexibility to Manage Its Operating Costs. In contrast to most state agencies, UC directly manages its employee compensation programs. That is, it sets salaries for its employees, manages its own employee and retiree benefit programs, and sets its own pension contribution rates. Moreover, about two‑thirds of UC’s core‑funded employees are not represented by a union, giving the university considerable year‑to‑year flexibility to determine salary increases. That said, UC faces certain limitations each year. For example, UC generally must pay debt service on the bonds it issues. UC also must ensure that its pension system has sufficient funds to pay for pension benefits.

State Has Primarily Supported UC Operations Through Unrestricted Base Increases. In recent years, the state and UC have used three main means to cover its operational cost increases: (1) state General Fund augmentations, (2) additional revenue from tuition increases, and (3) increased nonresident undergraduate enrollment. (Because nonresident undergraduate students pay a supplemental charge that covers more than the cost of their education, the net revenue generated from these students is available to support cost increases.) Figure 4 tracks the use of these budget tools over the past several years. In all but one of the years shown, the state provided UC with base General Fund increases. Notably, in only one of these years (2019‑20) was the base increase linked to specific UC operating cost increases. In the other years of the period, the base increases appeared to be set arbitrarily, without a direct link to UC’s operating costs. In addition to the base General Fund augmentations, UC campuses regularly increased revenue generated from nonresident students by increasing both their supplemental tuition charge and enrollment levels. In most recent years, UC did not increase the base tuition charge (which is applied to both resident and nonresident students).

Figure 4

UC Has Used Several Means to Cover Operating Cost Increases

Annual Change

|

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

Base General Fund support |

5%a |

5%a |

4% |

4% |

4%b |

3% |

3%c |

‑8%d |

5% |

|

Tuition charges |

|||||||||

|

Base tuition |

— |

— |

— |

— |

3 |

‑1e |

— |

— |

— |

|

Nonresident supplemental tuition |

— |

— |

8 |

8 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

— |

— |

|

Student Services Fee |

— |

— |

5 |

5 |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Nonresident undergraduate enrollment |

29 |

22 |

17 |

12 |

6 |

6 |

2 |

‑5 |

7 |

|

aSmall portion of increases were designated for specified purposes, such as online course development and UC labor center operations. bPortion of augmentation was covered with Proposition 56 funds. cIncrease connected to specific UC operating cost estimates. dState restored this reduction in 2021‑22, on top of the base increase it provided UC that year. eDecrease due to end of special $60 surcharge adopted in 2007‑08. |

|||||||||

Proposal

Governor Proposes Unrestricted General Fund Base Increase. The Governor proposes a $201 million (5 percent) unrestricted General Fund increase for UC in 2022‑23. (As part of his multiyear compact, the Governor proposes to provide 5 percent base increases annually through 2026‑27, with future increases contingent on UC meeting certain expectations.)

UC Also Anticipates Receiving More Tuition Revenue. UC estimates it will receive roughly $45 million in new student tuition revenue available to cover operating costs. Of this amount, $41 million will come from tuition increases on resident and nonresident students. The remainder will be generated from growing nonresident undergraduate enrollment. (The nonresident enrollment growth will be concentrated at UC’s less selective campuses. As we note in the “Enrollment” section of this brief, UC plans to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses in 2022‑23.) The exact amount of tuition revenue UC raises will depend on the number of students it enrolls in 2022‑23. (Of the revenue generated from fee increases, UC intends to set aside a portion for student financial aid. The amounts in this paragraph are net of this set aside.)

Assessment

Base Increases Are Poor Approach to Budgeting for Operating Costs. As we have said in many previous publications, base increases are a poor approach for two reasons. First, they lack transparency. The Governor does not identify how UC is to use its base increase. Moreover, UC itself does not adopt a corresponding spending plan until after final budget enactment in June. Second, given the purpose of the funding is unspecified, the amount of proposed augmentations are arbitrary, lacking clear justification based on documented cost increases.

Legislature Could Begin by Considering Nonsalary Cost Increases. Among UC’s operating costs, we think the Legislature may wish to first consider how much to provide for employee benefits, debt service, and OE&E. Costs in these areas are driven by UC policy and contractual arrangements that, absent a change in policy, are set to increase. In 2022‑23, UC estimates that total core costs in these areas will increase by $78 million.

Legislature Then Could Consider Salary Increases. After covering nonsalary cost increases, the Legislature could consider how much funding to provide for salary increases. Generally speaking, the goal of providing salary increases is to ensure the university is able to attract and retain faculty and staff. Though recent evidence of the competitiveness of UC salaries is limited, there is little evidence that the university experiences difficulty with attracting most of its faculty and staff. For example, UC faculty salaries on average are higher than most public universities engaging in a similar level of research. Moreover, faculty separations have remained about the same over the last ten years. That said, campuses have reported to our office that they have difficulty recruiting and retaining certain types of staff, such as mental health counselors. Additionally, inflation is anticipated to be higher in 2022‑23 than in past decades, likely generating pressure for larger‑than‑typical salary increases. The Legislature likely will want to weigh these competing factors when deciding how much funding to provide for salary increases in 2022‑23. To help with the Legislature’s planning, we estimate each 1 percent increase in UC’s total salary pool in 2022‑23 would be approximately $45 million.

Recommendation

Build Base Increase Around Identified Operating Cost Increases. We recommend the Legislature decide the level of base increase to provide UC by considering the operating cost increases it wants to support in 2022‑23. The Legislature could start with UC’s nonsalary cost increases ($78 million). From this point, the Legislature could consider providing funds for salary increases (around $45 million for each 1 percent increase). For illustration, at the Governor’s proposed funding augmentation ($246 million, consisting of $201 million in new General Fund and $45 million in new tuition and fee revenue), the Legislature could cover UC’s nonsalary cost increases as well as a nearly 4 percent increase in UC’s salary pool.

Enrollment

In this section, we first provide background on the state’s approach to funding UC enrollment as well as review recent UC enrollment trends. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed funding increases for enrollment in 2022‑23 and his proposed multiyear enrollment plan. We then assess the Governor’s proposals and make associated recommendations.

Background

State Typically Sets Enrollment Targets and Provides Associated Funding. Over the past two decades, the state’s typical enrollment approach for UC has been to set systemwide resident enrollment targets. If the target reflects growth (sometimes the state leaves the target flat), the state typically provides associated General Fund augmentations. Augmentations have been determined using an agreed‑upon per‑student funding rate derived from the “marginal cost” formula. This formula estimates the cost to enroll each additional student and shares the cost between anticipated tuition revenue and state General Fund.

State’s Approach Has Changed in Three Key Ways in Recent Years. Since the 2015‑16 Budget Act, the state has made three key changes to its enrollment approach for UC, described below.

- Setting an Outyear Target. Whereas the state historically set targets for the upcoming year, most recent budgets have set a target for the following year (for example, setting a target in the 2021‑22 budget for 2022‑23). Setting an outyear target allows the state to better influence admission decisions, as campuses typically have already made their decisions for the upcoming year before the enactment of the state budget in June.

- Setting Growth Target Only. In the past, the state commonly specified both the overall level of enrollment it expected and the associated growth over the previous year. (For example, the state might set the total enrollment level at 200,000 students, with associated growth from the prior year set at 1,000 students.) Since the 2015‑16 Budget Act, the state has stopped setting the overall enrollment level and specified only the expected amount of growth over a baseline year.

- Setting Targets for Undergraduate Students Only. The state commonly has set targets for overall resident enrollment, giving UC flexibility to determine the mix of undergraduate and graduate students. Most recent budgets, however, have set a target for UC resident undergraduate growth only. (As an exception, the 2017‑18 Budget Act funded growth of 500 graduate students.)

State Set Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target for 2022‑23. In the midst of the pandemic, the Legislature opted not to set enrollment growth targets in the 2020‑21 Budget Act for 2021‑22. Such an approach gave UC flexibility to manage funding reductions and uncertain enrollment demand that year. When state revenues recovered the following year, the state resumed setting targets. Specifically, the state set an expectation in the 2021‑22 Budget Act that UC grow resident undergraduate enrollment in 2022‑23 by 6,230 students. The budget act passed in June had made this a two‑year expectation by setting 2020‑21 as the baseline year, but clean‑up legislation enacted in the fall amended the baseline year to 2021‑22. Language in the 2021‑22 Budget Act also stated legislative intent to provide ongoing state funding for this growth beginning in 2022‑23.

State Also Adopted Multiyear Plan to Reduce Nonresident Undergraduate Enrollment at UC. Until recently, the state typically has been silent on the number of nonresident students that UC campuses could enroll. Nonresident students are self‑supported by revenue generated from tuition and supplemental tuition charges and historically have comprised a small share of undergraduate enrollment. Beginning around the time of the Great Recession, however, several UC campuses notably increased nonresident undergraduate enrollment. Concerned about the potential impact of this growth on access for resident students, the state began adopting policies to limit nonresident enrollment. Most recently, the 2021‑22 budget initiated a plan to reduce the nonresident share of undergraduate students at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses from over 21 percent in 2021‑22 to 18 percent by 2026‑27. (One additional campus—Irvine—has approximately 18 percent nonresident undergraduates and the remaining five undergraduate‑serving campuses have smaller shares.) UC is to achieve the reduction targets by gradually enrolling fewer incoming students. The plan is to start in 2022‑23, with the state providing funding for the lost tuition revenue associated with the reduction in nonresident students. At the time of adopting this plan, it was estimated UC would have to reduce nonresident enrollment by 902 students annually.

Recent Enrollment Trends

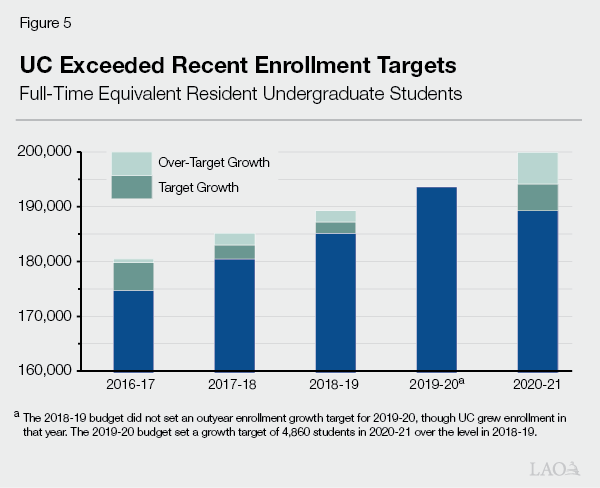

UC Exceeded Targets From 2016‑17 Through 2020‑21. As Figure 5 shows, each year the state established an enrollment growth target, UC exceeded its growth expectation. To date, the state has not provided UC additional General Fund support specifically designated for this over‑target enrollment. Instead, the state has built this over‑target enrollment into the new baseline it sets for UC. For example, in 2017‑18, UC resident undergraduate enrollment grew by around 4,700 students over the level in 2016‑17, exceeding the 2,500 student growth budgeted by the state. When the state set the growth target for 2018‑19, it set the new baseline at the higher 2017‑18 level, thus effectively absorbing the over‑target enrollment. Since 2016‑17, UC has enrolled around 10,700 students more than the state growth targets, with more than half of the over‑target growth occurring in 2020‑21 alone.

Resident Undergraduate Enrollment in 2021‑22 Expected to Decline Slightly. Though the 2021‑22 academic year has not yet finished, UC has made initial estimates based on enrollment levels in the summer and fall of 2021. UC estimates 2021‑22 resident undergraduate enrollment to be 199,358 students—717 students (0.4 percent) below the level in 2020‑21. As Figure 6 shows, UC experienced a drop in summer 2021 enrollment. Summer enrollment spiked in 2020 in the midst of the pandemic, likely because students had more opportunities to study online and fewer summer employment opportunities. The subsequent drop in summer 2021 could reflect fewer online course offerings or improved summer employment opportunities for students. Though UC saw a drop in summer 2021 enrollment, fall 2021 enrollment increased, which likely will translate into a corresponding increase in the spring 2022 term.

Figure 6

UC Enrollment Drop in 2021‑22 Attributable to

Decline in Summer Enrollment

Resident Undergraduate Full‑Time Equivalent Students

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Change From 2020‑21 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Fall through spring |

176,984 |

177,643 |

180,113 |

2,470 |

1.4% |

|

Summera |

16,808 |

22,432 |

19,245 |

‑3,187 |

‑14.2 |

|

Totals |

193,792 |

200,075 |

199,358 |

‑717 |

‑0.4% |

|

aSummer term is treated as the first term of a fiscal year. For example, summer 2019 is counted toward 2019‑20. |

|||||

UC Is Planning for Lower Growth in 2022‑23 Than Directed in Budget. In its 2022‑23 budget request to the state, the UC Board of Regents adopted a plan to grow resident undergraduate enrollment by 2,000 students over the level in 2021‑22, thus enrolling around 202,000 students in 2022‑23. Of the growth of 2,000 students in 2022‑23, 900 would be allocated to the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses (combined) to replace reductions in nonresident students. The remaining 1,100 students would be concentrated at the remaining six undergraduate‑serving campuses. According to UC, it does not intend to grow by 6,230 students in 2022‑23 (the target set in the 2021‑22 Budget Act) because of having enrollment over its target in previous years. Specifically, UC would like to count over‑target growth in 2020‑21 toward the state’s growth expectation.

Proposals

Proposes $99 Million Ongoing General Fund for Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Growth in 2022‑23. Of this amount, $67.8 million is to support enrollment growth of 6,230 undergraduate resident students in 2022‑23. Proposed budget bill language specifies 2020‑21, rather than 2021‑22, as the baseline year. This amount assumes a marginal cost of $10,866 per student, the rate for 2021‑22. The remaining $31 million is for reducing nonresident enrollment by 902 students and replacing those students with resident students. The $31 million is intended to replace lost nonresident supplemental tuition revenue, as well as lost base tuition revenue paid by nonresident students that supports financial aid for resident students. Including both proposals together, the administration expects UC to enroll 207,207 resident undergraduate students in 2022‑23, 7,132 more students than the level in 2020‑21.

Proposes Multiyear Enrollment Plan. The Governor’s compact includes a multiyear plan to expand undergraduate and graduate student enrollment. Specifically, the administration proposes that UC grow resident undergraduate enrollment by around 1 percent each year from 2023‑24 through 2026‑27. (Though proposed as part of the compact, the Governor does not specify the 1 percent growth expectation for 2023‑24 in the budget bill.) According to the administration, this annual growth would represent more than 8,000 additional students across the four‑year period. The administration also proposes that UC grow graduate student enrollment by roughly 2,500 students over the same time period. Under the Governor’s compact, UC would not receive additional funds for enrollment growth over the period, but instead it would need to accommodate the higher costs from within its base increases.

Assessment

Disconnect Between Governor’s Proposal and UC Plan Raises Issues for Legislature to Consider. The administration describes its 2022‑23 enrollment growth proposal as intended to implement the state budget agreement adopted last year. UC has indicated, however, that it is not planning to meet the administration’s target enrollment level of 207,207 students. The Legislature could respond to this disconnect by reducing UC’s associated enrollment growth funding—providing funding only for the additional students UC plans to enroll in 2022‑23 over the set baseline year. This approach keeps the tightest connection between new state funding and new students enrolled. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider providing UC the full amount proposed by the Governor—effectively funding some over‑target enrollment from 2020‑21 and raising UC’s per‑student funding level. In recent years, the state has not funded over‑target enrollment. Such a practice could create incentives for UC to disregard state enrollment growth targets with resulting fiscal impacts that could run counter to legislative intent. UC, however, is in a somewhat unusual situation due to the pandemic. Given the unusual times, the Legislature may want to consider making an exception for UC this year.

Setting Funded Enrollment Level Could Clarify Intent Moving Forward. The purpose of setting enrollment targets is to make clear expectations regarding the number students the universities are to enroll. The state’s recent practice of setting growth targets has worked well when the Legislature, administration, and segments shared a common understanding of the baseline level of students. Recent experience, however, suggests that there may be different interpretations as to the existing baseline level of funded enrollment at UC. Without a shared understanding, the Legislature runs the risk of UC and the administration implementing future enrollment expectations in ways that do not align with its intent.

Three Undergraduate Enrollment Trends to Consider. The recent pandemic has made it increasingly complicated for the state and UC to project enrollment demand. Nonetheless, three key trends, described below, could shape the Legislature’s considerations for UC resident undergraduate enrollment in 2023‑24.

- High School Graduates. The Department of Finance projects the number of high school graduates in California to increase by 0.3 percent in 2021‑22 (affecting fall 2022 demand) and by 0.6 percent in 2022‑23 (affecting fall 2023 demand). All else equal, a rise in high school graduates increases UC freshman enrollment demand.

- Community College Students. Transfer student enrollment rose at UC from fall 2016 through fall 2020, corresponding with growth in CCC enrollment over the same time period. CCC enrollment declined in 2020‑21, however, and a further drop is expected in 2021‑22. Whether this drop results in a corresponding decline in UC transfer enrollment is uncertain. UC has enrollment management tools, such as reducing transfer referrals to less selective campuses, that could allow it to increase its transfer yield rates and maintain its transfer enrollment levels.

- Referral Pools. UC refers students who are not admitted to their campuses of choice to less selective campuses. UC Merced is UC’s sole referral campus for freshman applicants, and UC Merced and UC Riverside are UC’s referral campuses for transfer students. Providing funding for more enrollment can potentially reduce the number of students referred to less selective campuses. In fall 2020 (the most recent year of data publicly available), UC referred 9,110 freshman applicants (10 percent). UC does not regularly report the number of transfer students referred.

Eligibility and Admission Policies Remain a Consideration. Historically, the state has expected UC to draw its freshman admits from the top 12.5 percent of the state’s high school graduates. As we have noted in previous analyses, UC has been found to be drawing from beyond these pools in recent years and likely will continue to do so. In past periods, the state has expected UC to tighten freshman admission policies when it was found to be drawing from beyond these pools. When the UC tightens its admission policies, it effectively redirects a portion of its enrollment to CSU and CCC.

Outyear Resident Enrollment Target Likely Will Affect Future Nonresident Plans. As the Legislature increases systemwide resident undergraduate enrollment (and thus, overall undergraduate enrollment), it reduces the number of nonresident students UC must reduce to attain the 18 percent goal at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses. If the Legislature desires to grow resident enrollment in future years, it will want to receive updated nonresident enrollment and cost information from UC. UC currently is required to submit an annual report with this information to the Legislature by January 31, with the first report due at the end of this month.

Different Set of Considerations for Graduate Enrollment. In contrast to undergraduate enrollment, access has not been a primary focus of the state when deciding whether to support graduate student enrollment growth. Rather, the primary focus in past years has been on state workforce needs for graduate students. Existing workforce demand likely varies for academic doctoral, academic master’s, and professional graduate students. For example, there is little evidence that the state is facing overall shortages of doctoral students to fill higher education faculty positions. On the other hand, there is some evidence of regional shortages for certain professions (such as for primary care physicians). Beyond workforce considerations, UC campuses also often seek to grow graduate enrollment proportionate to undergraduate enrollment. This practice ensures campuses have an adequate number of teaching and research assistants to accommodate the higher level of undergraduate courses and faculty workload.

Recommendations

Use UC’s Planned Growth as a Starting Point for Resident Undergraduate Enrollment in 2022‑23. As UC indicates it will enroll only 1,100 rather than 6,230 additional resident undergraduate students in 2022‑23 (excluding the approximately 900 new students from the nonresident reduction plan), we recommend the Legislature consider that planned growth as a starting point for funding (costing $12 million, using the 2022‑23 marginal cost of instruction of $11,200 per student). Though the Legislature could consider providing more than the $12 million, such action would differ from recent state practice. The Legislature likely would want to consider providing more funding only if it were concerned about UC having over‑target enrollment in 2020‑21 and its resulting per‑student funding being too low.

Adopt Nonresident Reduction Funds. Consistent with last year’s budget agreement, we recommend adopting funds for planned reductions in nonresident enrollment (and associated growth in resident students) in 2022‑23. We think the Governor’s proposed level of funding ($31 million for the 900 student replacement) likely is justified. That said, we recommend the Legislature review UC’s forthcoming report, due January 31, to ensure UC intends to reduce nonresident enrollment at the affected campuses by a combined 900 students.

Set Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target in 2023‑24. After making decisions for 2022‑23, we recommend the Legislature set a resident undergraduate enrollment target for budget‑year‑plus‑one. Depending on the factors discussed earlier, the Legislature could consider any number of options. For example, the Legislature could set the target in 2023‑24 at 207,207 students, thus giving UC more time to meet the administration’s proposed enrollment level. Alternatively, the Legislature could adjust its expectations based on more recent trends, funding more or less growth as it deems warranted. Regardless of the Legislature’s desired level of enrollment, we recommend setting the target enrollment level, rather than just a growth target, for 2023‑24 in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. Such an approach would better clarify legislative intent and enhance accountability. Moreover, we recommend scheduling any funds for growth in 2023‑24 to be appropriated in the 2023‑24 budget. This approach allows the state more easily to align funding with updated enrollment estimates for that year.

Consider Expectations for Graduate Enrollment. If the Legislature has specific workforce priorities that entail graduate student growth, it could set a target for 2023‑24. That said, the Legislature could continue its current approach of not setting a graduate enrollment target if it has no specific graduate student‑related priorities.

Facility Maintenance

In this section, we provide background on UC’s maintenance backlog, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects at UC, assess the proposal, and offer associated recommendations. Throughout this section, we use “facility maintenance” broadly to encompass activities needed to keep academic facilities and infrastructure in good condition. This includes capital renewal projects to replace aging building components, such as roofs and heating and ventilation systems.

Background

Campuses Have Maintenance Backlogs. Like most state agencies, UC campuses are responsible for funding the maintenance and operations of their buildings from their support budgets. When campuses do not set aside enough funding from their support budgets to maintain their facilities, they begin accumulating backlogs. These backlogs can build up over time, especially during recessions when campuses sometimes defer maintenance projects as a way to help them cope with state funding reductions.

UC Has Been Developing a Better Estimate of Its Maintenance Backlog. For the past several years, UC has indicated that its maintenance backlog totals billions of dollars. Until very recently, it lacked a more precise estimate. This is because campuses historically maintained their own lists of deferred maintenance projects. According to staff at the UC Office of the President, these lists were not reliable because campuses used different approaches to estimate their backlogs and generally had not undertaken comprehensive condition assessments of their buildings. To obtain a better estimate, UC began undertaking a multiyear project known as the Integrated Capital Asset Management Program (ICAMP). Under ICAMP, UC is conducting facility condition assessments of all its academic facilities and infrastructure. In conjunction with this effort, the Legislature in the Supplemental Report of the 2019‑20 Budget Act directed UC to submit a report quantifying its long‑term maintenance and renewal needs.

UC Recently Released Updated Estimates. In December 2021, UC released its long‑term maintenance and renewal report to the Legislature. In the report, UC estimates having a total ten‑year capital renewal need of $12.3 billion, on top of an existing $7.3 billion maintenance backlog. (According to UC, its capital renewal need likely is higher than $12.3 billion, as the university has not yet completed its systemwide infrastructure assessments.) As Figure 7 shows, UC estimates it would need to spend an average of $1.2 billion annually over the next ten years to address its capital renewal needs, as well as an additional $728 million annually to eliminate its existing backlog. The combined amount is $1.7 billion more than the best available estimate of UC’s current annual spending on these types of projects ($291 million in 2019‑20).

Figure 7

UC Has Considerable Maintenance

and Capital Renewal Needs

(In Millions)

|

Total Costs |

|

|

Projected ten‑year renewal needa |

$12,313 |

|

Existing maintenance backlog |

7,277 |

|

Total |

$19,590 |

|

Average Annual Costb |

|

|

Capital renewal costs |

$1,231 |

|

Maintenance backlog |

728 |

|

Total |

$1,959 |

|

Existing Annual Spending |

$291 |

|

Gap in Annual Spending |

$1,669 |

|

aReflects renewal need for academic facilities only, as UC is still assessing the condition of its infrastructure. bReflects estimates of amounts UC would need to spend each year for ten years to prevent its backlog from growing while also eliminating the existing backlog. |

|

State Has Provided Funds to Address Backlogs. In the years since the Great Recession, the state has provided one‑time funding to UC to help address its maintenance backlog. Figure 8 shows the amount appropriated by the state for deferred maintenance and related purposes each year from 2015‑16 through 2021‑22. Funding over the period totals $704 million, with nearly half of that amount provided in 2021‑22 alone. Notably, the state allowed UC to use its 2021‑22 allocation to pay for either deferred maintenance or energy efficiency projects. UC reports that it is spending about two‑thirds of the allocation on energy efficiency projects (most of which also address deferred maintenance), and the remaining one‑third on projects strictly intended to address deferred maintenance.

Figure 8

State Has Provided Funding to Address Deferred Maintenance at UC

One‑Time Funds (In Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

General Fund |

$25 |

$35 |

— |

$35 |

$144a |

— |

$325b |

|

UC bondsc |

— |

— |

$35d |

35 |

35 |

$35 |

— |

|

Totals |

$25 |

$35 |

$35 |

$70 |

$179 |

$35 |

$325 |

|

aThe 2020‑21 budget package allowed UC to repurpose unspent 2019‑20 deferred maintenance funds for other operational purposes. bAmount was provided for deferred maintenance or energy efficiency projects. cReflects state‑authorized UC bond funds. UC repays the debt on these bonds using its General Fund support. dIn 2017‑18, the state authorized an additional $15 million in UC bond funds for systemwide facility and infrastructure assessments. |

|||||||

Proposal

Governor Proposes Funding for Deferred Maintenance and Energy Efficiency Projects. The Governor proposes to provide $100 million one‑time General Fund to UC for these purposes. Though UC has not submitted a list of specific projects that would receive funding, UC indicates that it likely would draw from a list of projects totaling $788 million deemed by ICAMP to be “highest risk.” (Upon request, UC submitted this list of projects to our office in January 2022.) According to UC, projects in the highest risk category should be addressed within the next few years to avoid disruptions to campus operations. Budget bill language would direct the administration to report to the Legislature on the specific projects selected within 30 days after the funds are released to UC.

Assessment

Proposal Reflects a Prudent Use of One‑Time Funding. Providing funds for deferred maintenance projects would address an existing need that is growing. Addressing this need can help avoid more expensive facilities projects, including emergency repairs, in the long run. Funding energy efficiency projects also could be beneficial, as these projects are intended to reduce campuses’ utility costs over time.

One‑Time Funding Does Not Address Underlying Cause of Backlog. Deferred maintenance backlogs tend to emerge when campuses do not consistently maintain their facilities and infrastructure on an ongoing basis. Based on its estimates, UC would need to increase its ongoing spending on maintenance and capital renewal by around $1 billion just to keep the backlog from growing. (This reflects the gap between UC’s average annual capital renewal costs of $1.2 billion and its existing annual spending of $291 million.) Although one‑time funding can help reduce the backlog in the short term, it does not address the underlying ongoing problem of underfunding in this area.

Recommendations

Consider Governor’s Proposal as a Starting Point. To address UC’s maintenance backlog, we recommend the Legislature provide at least the $100 million proposed by the Governor. As it deliberates on the Governor’s other one‑time proposals and receives updated revenue information in May, the Legislature could consider providing UC with more one‑time funding for this purpose. (Though we focus on UC in this budget brief, other state agencies also have documented deferred maintenance backlogs. The Legislature could consider providing one‑time funding to address these backlogs too.)

Consider Developing Strategy to Address Ongoing Maintenance and Capital Renewal Needs. In addition to providing one‑time funding for deferred maintenance, we encourage the Legislature to begin developing a long‑term strategy around UC maintenance and capital renewal needs. Potential issues to consider include timing, fund sources, ongoing versus one‑time funds, and reporting. Given the magnitude of the ongoing maintenance and capital renewal needs at UC, developing such a strategy would likely require significant planning beyond the 2022‑23 budget cycle.