LAO Contact

February 4, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Initial Comments on the

State Appropriations Limit Proposal

Summary. The state appropriations limit (SAL) constrains how the Legislature can use revenues that exceed a specific threshold. Given recent revenue growth, the SAL has become an important consideration in the state budget process and will continue to constrain the Legislature’s choices in this year’s budget process. This post provides our office’s initial analysis on and comments about the Governor’s proposals to address SAL requirements in the 2022‑23 Governor’s Budget.

How Does the SAL Work?

In the late 1970s, voters passed Proposition 4 (1979), which added Article XIIIB to the State Constitution. Article XIIIB established an appropriations limit on the state and most types of local governments. (These limits also are referred to as “Gann limits” in reference to one of the measure’s coauthors, Paul Gann.) The limits later were amended by Proposition 111, which was passed by voters in 1990. For more information about the history of the appropriations limit, see our previous reports, including: The State Appropriations Limit.

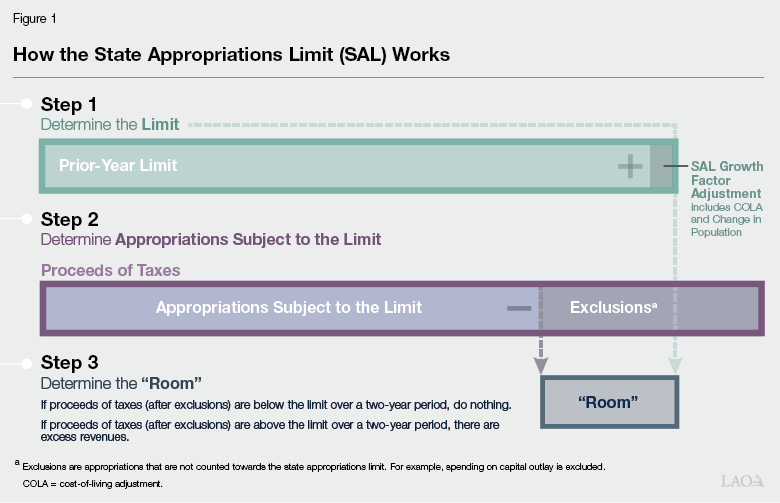

How the Formula Works. Each year the state must compare the appropriations limit to appropriations subject to the limit. As shown in Step 1 of Figure 1, this year’s limit is calculated by adjusting last year’s limit for a growth factor that includes economic and population growth. As shown in Step 2, appropriations subject to the limit are determined by taking all proceeds of taxes and subtracting excluded spending. In Step 3, the state compares appropriations subject to the limit to the limit itself. If appropriations subject to the limit are less than the limit, there is “room.” If appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit (on net) over any two‑year period, there are excess revenues.

How Does the Legislature Meet the Constitutional Requirements Under the SAL? As implied by Figure 1, if appropriations subject to the limit are expected to exceed the limit, the Legislature can: (1) lower proceeds of taxes, (2) increase exclusions, or (3) split the excess revenues between additional school and community college district spending and taxpayer rebates. (Exclusions include: subventions to local governments, capital outlay projects, debt service, federal and court mandates, and certain kinds of emergency spending.)

How Have SAL Requirements Changed?

Prior Year (2020‑21) and Current Year (2021‑22)

When the 2021‑22 Budget Act was enacted in June 2021, the state anticipated there would be room under the limit, across 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, of $16.9 billion. At Governor’s budget, under the administration’s updated revenue estimates and budget proposals, there are excess revenues of $2.6 billion across these years—a net $19.5 billion change in the state’s SAL position. (These requirements also differ somewhat from the requirements our office estimated in the November Fiscal Outlook. We describe these changes in more detail in the nearby box.) As shown in Figure 2, this change has the following components:

- Higher Revenues. Across the two years, SAL revenues are higher by $22.5 billion consistent with strong revenue collections across all three major tax sources. (SAL revenues include both General Fund and special tax revenues. General Fund SAL revenues differ slightly from total General Fund revenues because not all revenues are proceeds of taxes.)

- More Exclusions. Across the two years, exclusions are higher by about $3 billion, although this change masks significant variation in exclusions occurring both up and down. A key difference is the administration’s higher estimate of qualified capital outlay, which increased mainly due to some technical scoring issues.

- Appropriations Limit Unchanged. Finally, the appropriations limit itself is unchanged. The state does not revisit its estimate of the limit after the budget has been passed.

How Do These SAL Requirements Compare to Our Fiscal Outlook?

Prior Year and Current Year. In our November Fiscal Outlook, we estimated the state would have $14 billion in state appropriations limit (SAL) requirements to address across 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, compared to the administration’s estimate of $2.6 billion. There are two major reasons for the difference (in addition to many other smaller differences). First, the administration’s SAL revenue estimates (excluding proposals) are lower than ours by about $6 billion across 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. Second, the Governor’s budget proposes reallocating over $3 billion in transportation funds, which count as exclusions, which our office assumed would revert to the General Fund.

Budget Year. In our November Fiscal Outlook, we estimated the state would have $12 billion in SAL requirements to address in 2022‑23. The administration shows room of $5.7 billion. The key reason for this difference is that our estimates did not make any assumptions about how the surplus would be allocated. The Governor’s budget, by contrast, proposes allocations for the surplus, including to purposes that meet SAL requirements, such as additional spending on capital outlay and reductions in tax revenues. (We discuss these specific proposals in greater detail below.) In addition, some of our assumptions are different. For example, the administration’s tax revenue estimates (excluding policy proposals) are lower than ours by $3 billion in 2022‑23.

Figure 2

Comparing SAL Estimates, Budget Act

to Governor’s Budget

(In Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

SAL Revenues and Transfers |

||

|

Budget Act |

$208,667 |

$207,919 |

|

Governor’s budget |

215,221 |

223,906 |

|

Difference |

‑$6,554 |

‑$15,987 |

|

Exclusions |

||

|

Budget Act |

‑$79,158 |

‑$112,739 |

|

Governor’s budget |

‑80,363 |

‑114,604 |

|

Difference |

$1,205 |

$1,865 |

|

Appropriations Limit |

||

|

Budget Act |

$115,860 |

$125,695 |

|

Governor’s budget |

115,860 |

125,695 |

|

Difference |

— |

— |

|

Net Effect |

‑$5,349 |

‑$14,122 |

|

Two Year Total |

‑$19,471 |

|

|

SAL = state appropriations limit. |

||

What Are the SAL Requirements Under the Governor’s Budget?

Some Proposals Help Address Requirements... The Governor’s budget includes proposals—both revenue reductions and spending increases—that help the state address its SAL requirements. In particular, these include:

- $17 Billion in Proposals Using the General Fund Surplus. The Governor’s budget allocates a surplus of $29 billion across a variety of program areas. These proposals include $16.9 billion in discretionary proposals across 2021‑22 and 2022‑23—both revenue and spending—that address SAL requirements. Figure 3, shows the major excludable spending proposals in the Governor’s budget. (For a complete listing of the Governor’s budget spending proposals, including the amount of SAL exclusions, see: https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2022/4492/Overview‑Appendix‑011422.pdf.)

- $2.2 Billion in Proposals Using Discretionary Proposition 98 Funds. The Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. After setting aside funding for statutory cost‑of‑living adjustments and other planned program expansions, the Governor’s budget includes nearly $13 billion in discretionary spending proposals to meet the constitutionally required funding level for schools and community colleges. Of this total, the proposals include $2.2 billion in discretionary proposals that address SAL requirements.

Figure 3

Major SAL Excludable Governor’s Budget Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Department |

Proposal |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

Secretary for Transportation Agency |

Transportation Infrastructure Package |

$3,500 |

— |

|

Secretary for Transportation Agency |

Supply Chain Resilience |

— |

$600 |

|

Department of Transportation |

Transportation Infrastructure Package |

800 |

600 |

|

School Facilities Aid Program |

Funding for School Facilities Program |

— |

1,250 |

|

Energy Commission |

Clean energy and building decarbonization |

— |

545 |

|

State Hospitals |

Implement IST waitlist workgroup solution |

— |

350 |

|

Department of Water Resources |

Drought response activities |

— |

250 |

|

Energy Commission |

Zero‑emission vehicle programs |

— |

250 |

|

HCD |

Infill Infrastructure Grant Program |

— |

225 |

|

CDCR |

Ironwood State Prison HVAC Project Conversion to General Fund |

— |

182 |

|

California Military Department |

Sacramento: Consolidated Headquarters Complex Bonds to Cash |

— |

159 |

|

Various Departments |

Contingency funding for unspecified activities |

— |

155 |

|

CalFire |

Various capital outlay |

— |

120 |

|

OES |

California Disaster Assistance Act Adjustment |

— |

114 |

|

Department of General Services |

Facilities Management Division Deferred Maintenance |

— |

101 |

|

California State University |

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

— |

100 |

|

University of California |

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

— |

100 |

|

Department of Water Resources |

Oroville pump storage and energy reliability support |

— |

100 |

|

BSCC |

County Operated Juvenile Facility Grants |

— |

100 |

|

Note: Includes proposals using General Fund surplus monies greater than $100 million. For a complete list of all proposals, see: https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2022/4492/Overview‑Appendix‑011422.pdf. |

|||

|

SAL = state appropriations limit; IST = Incompetent to Stand Trial; HCD = Department of Housing and Community Development; CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; HVAC = heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; and OES = Governor’s Office of Emergency Services. |

|||

…But Excess Revenues Remain Outstanding. After accounting for revenue reductions and excluded spending, the Governor’s budget estimates there would be $2.6 billion in excess revenues from 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. The Governor’s budget does not set aside a portion of the surplus to meet this requirement. (The constitution allows the state two years to address this requirement.)

What Happens to the SAL if Revenue Estimates Change?

Revenue estimates change throughout the fiscal year and the Governor’s May Revision will reflect new revenue estimates that incorporate the latest collected data—particularly from the key revenue month, April. This section describes how updated revenue estimates are likely to affect the state’s SAL position—and, by extension, the surplus.

Typically, Each $1 in Unanticipated Revenues Results in $0.40 in Additional Surplus. When the state has a surplus, an additional $1 of unanticipated revenues typically would result in about $0.40 of additional surplus—although this can vary widely depending on specific conditions like stock market performance and school attendance. The state’s surplus does not increase by $1 for each $1 in additional revenues because of the state’s constitutional requirements, which require the state to allocate revenues to particular uses. Specifically, for each $1 in unanticipated revenues:

- Proposition 98 (Spending on Schools and Community Colleges) Increases by $0.40. The Proposition 98 (1988) formulas determine the minimum amount the state must spend on schools and community colleges each year. Under current conditions, the Proposition 98 formulas require the state to spend about $0.40 on new school spending for each $1 in new revenues.

- Proposition 2 (Debt Payments and Reserve Deposits) Requirements Increase between $0.15 and $0.20. The Proposition 2 (2014) formulas require the state to set aside minimum amounts each year for reserves and debt payments. In general, an additional $1 of revenue above expectations likely means an increase in Proposition 2 requirements of between $0.15 and $0.20, although they can be as high as $0.30 in strong stock market years.

This Year, Each $1 Increase in Current‑Year Tax Revenues Also Will Result in $1 in Additional SAL Requirements. This year, additional revenues will result in even more constitutional requirements. In particular, each $1 of additional revenue estimated in either 2020‑21 and/or 2021‑22 also will increase SAL requirements by $1. While some of the additional spending required by Propositions 98 and 2 could be excluded from the SAL, it is not a requirement. Depending on various spending choices made, the constitutional requirements of Propositions 4, 98, and 2 largely should be considered additive.

Each Additional $1 in Revenue Could Increase Requirements by $1.60 or So. The bottom line of the factors above is that, for each additional $1 revenue collected (especially in the current year), total constitutional requirements could increase by around $1.60. Counterintuitively, the dynamics are such this year that if revenues exceed expectations, Legislative flexibility over the surplus could decrease substantially.

LAO Comments

SAL Requirements Likely to Be Higher in May

We Expect Current‑Year Revenues to Be Higher Than the Governor Anticipates. According to our most recent “Big Three” revenue outlook update, there is a 90 percent chance that revenues will exceed Governor’s budget projections for the current year (2021‑22). The most likely outcome is that 2021‑22 revenues will exceed expectations by $5 billion to $20 billion.

Some Currently Non‑Excluded Spending Likely Needs to Be Reduced at May Revision. If revenues exceed expectations by $10 billion in 2021‑22, for example, it could mean constitutional requirements increase by $15.5 billion to $17 billion. As a result, despite significantly higher revenues, the Legislature would have only limited discretion over this additional surplus. Specifically, under this example, the Legislature would need to allocate $10 billion to meeting the SAL requirements after meeting the requirements of Propositions 98 and 2. Consequently, there likely would be far fewer non‑excluded proposals than are included in the Governor’s budget. Figure 4 shows the major Governor’s budget spending proposals not excluded from the SAL.

Figure 4

Major Governor’s Budget Spending Proposals Not Excluded From SAL

(In Millions)

|

Department |

Proposal |

Amount |

|

Health Care Services |

Bridge housing through Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program |

$1,000 |

|

EDD |

UI Trust Fund loan repayment |

1,000 |

|

BCH Agency |

Encampment Resolution Grants Program |

500 |

|

CalFire |

Staffing and operational enhancements |

400 |

|

Health Care Services |

Undo delay in end‑of‑year fee‑for‑service provider payment processing |

309 |

|

Health Care Access and Information |

Provide funding for care economy workforce development |

271 |

|

Energy Commission |

Clean energy and building decarbonizationa |

266 |

|

Cal Fire |

Various forest health and resilience proposals |

243 |

|

Public Health |

Public health IT systems |

235 |

|

Health Care Services |

Payments to encourage equity and practice transformation |

200 |

|

Air Resources Board |

Zero‑emission vehicle programa |

160 |

|

Franchise Tax Board |

Enterprise Data to Revenue Project, Phase 2 |

151 |

|

GO‑Biz |

Small business grants |

150 |

|

CDCR |

Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program Expansion |

127 |

|

CDE |

State Preschool rate increase for students with disabilities |

111 |

|

Workforce Development Board |

Establish new HRTPs in health and human service careers |

110 |

|

Judicial Branch |

Promote Trial Court Fiscal Equity |

100 |

|

University of California |

Seed and matching grants for applied research |

100 |

|

Department of Conservation |

Oil well abandonment & remediation |

100 |

|

aPartial exclusions. |

||

|

Note: Includes proposals using General Fund surplus monies greater than $100 million. For a complete list of all proposals, see: https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2022/4492/Overview‑Appendix‑011422.pdf. |

||

|

SAL = state appropriations limit; EDD = Employment Development Department; UI = Unemployment Insurance; BCH Agency = Secretary for Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency; CalFire = California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection; IT = information technology; GO‑Biz = Governor ’s Office of Business and Economic Development; CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; CDE = California Department of Education; HRTP = High Road Training Partnership; and BSCC = Board of State and Community Corrections. |

||

Other, Difficult to Predict, Factors Also Will Influence the SAL Requirements. That said, many other factors also will change between now and May. For example, special fund tax revenues could be higher or lower, “baseline” exclusions (spending on exclusions under current law) could be higher or lower, and the limit itself will change in response to new data released in the spring. As a result, the actual change in the SAL requirements will be higher or lower than the specific change in General Fund tax revenue.

Options for Legislative Consideration

Two Different Approaches to Addressing SAL Requirements. Given the dynamics described above, the state very likely will face higher SAL requirements at the May Revision. The Legislature has two different options to address these, which can be implemented separately or in tandem. First, the state can take a preemptive approach. Through the iterative budget process, the state can lower revenues and/or spend more on excluded purposes, using a variety of fund sources. This approach lowers appropriations subject to the limit and reduces the potential for excess revenues. Second, the Legislature can choose to address any remaining excess revenues through taxpayer rebates and additional payments to schools and community colleges. We discuss each of these options in turn below.

Address SAL Requirements Preemptively. A preemptive approach involves different options, primarily using surplus funds, but other funds (such as Proposition 98 spending) also can be used. This alternative can include one, or any combination, of the following:

- Lower Tax Revenues. In order to reduce tax revenues for tax year 2021, the Legislature most likely would need to act very soon, but the state also could lower revenues for 2022 in the coming months. There are many options for tax reductions, including: broad‑based rebates, targeted rebates, and expansions of tax credits and programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit. Compared to waiting to address excess revenues, this option would afford the state more flexibility in designing the reductions. One advantage of this approach is that lowering tax revenues reduces some constitutionally required spending (described above) that otherwise would be required in addition to meeting the SAL’s requirements.

- Provide More Subventions to Local Governments. Under the Constitution and statute, subventions—funding provided to local governments on an unrestricted basis—are excluded from the SAL and counted, instead, at the local level. The state could provide more unrestricted funding to local governments or amend the definition of subvention in order to count more funding provided at the local level.

- Spend More on Infrastructure. The Constitution allows expenditures on capital outlay projects to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. Statute defines capital outlay as: “an appropriation for a fixed asset (including land and construction) with a useful life of 10 or more years and a value which equals or exceeds one hundred thousand dollars ($100,000).” The state could spend more on infrastructure‑related purposes from a variety of fund sources, including General Fund, Proposition 98 General Fund, and/or some tax‑revenue supported special funds.

- Spend More on Emergencies. The Constitution also allows expenditures on emergencies to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. However, those expenditures must meet three specific conditions. The spending must be: (1) related to an emergency declaration by the Governor, (2) approved by a two‑thirds vote of the Legislature, and (3) dedicated to an account for expenditures relating to that emergency. We think that some existing Governor’s budget proposals—such as the proposal to repay the Unemployment Insurance loan from the federal government—could be excluded as long as the funding was approved with a two‑thirds vote.

Excess Revenues Must Be Allocated to School Payments and Taxpayer Rebates. The Legislature could meet any remaining SAL requirements by splitting excess revenues between taxpayer rebates and payments to schools and community colleges The Constitution gives the state two years to make these payments, and so the costs could be funded in the 2023‑24 budget. That said, if this is the Legislature’s preferred approach, we recommend setting aside funding to pay for these costs this year. There is no guarantee that next year’s budget will have a surplus and, indeed, could face even more SAL requirements. Setting aside the money now will ensure the state has the resources to pay for these obligations.

Recommend the Legislature Make a Plan Before the May Revision for Addressing the Requirements. Regardless of which approach the Legislature decides to pursue, given the complexity of this budget situation, the high likelihood SAL requirements will increase, and the difficult trade‑offs at hand, we recommend the Legislature make a plan for how it wishes to approach potential requirements in May. We recommend the Legislature first determine how it wishes to meet the SAL’s requirements.

This decision will have significant spending implications. For instance, if the Legislature wishes to meet the SAL’s requirements through excluded spending, we recommend determining how to allocate that spending now. Moreover, regardless of how the Legislature wishes to meet the SAL’s requirements, there likely will be significantly less funding available for non‑excluded purposes. As such, we recommend the Legislature determine its priorities for non‑excluded spending. Although the Legislature does not need to finalize its budget now, determining the architecture of its preferred approach will increase its flexibility.