LAO Contact

Correction (3/1/22): The funding amount for the K-12 Strong Workforce Program has been adjusted.

February 23, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

College and Career Proposals

Summary. In his January budget, the Governor proposes $2 billion in one‑time funding across three programs to increase college and career readiness among high school students. In this post, we provide background on the state’s programs, describe and assess the Governor’s proposals, and provide our recommendations to the Legislature.

Background

Almost Two‑Thirds of High School Graduates Attend a Postsecondary Institution. California’s four‑year high school graduation rate (86 percent) is similar to the national average. Of the state’s graduates, 64 percent enrolled in college after graduating high school. (This is based on 2017‑18, the most recent year for which data is available.) Of those enrolling in college, 55 percent enrolled in a California community college (CCC), 30 percent enrolled in the University of California (UC) or California State University (CSU) systems, and 15 percent enrolled either at private or out‑of‑state colleges and universities.

About Half of Graduates Complete UC/CSU College Preparatory Course Requirements. Of the state’s high school graduates, about half (49 percent in 2017‑18) completed the college preparatory coursework required to be eligible for freshman admission at UC/CSU (known as the “A through G” series). Certain subgroups have lower rates of completion of these UC/CSU requirements. For example, in 2017‑18, 40 percent of graduates who were from low‑income families, 16 percent of graduates who were English learners, and 12 percent of graduates who were foster youth had completed UC/CSU college preparatory course requirements at graduation.

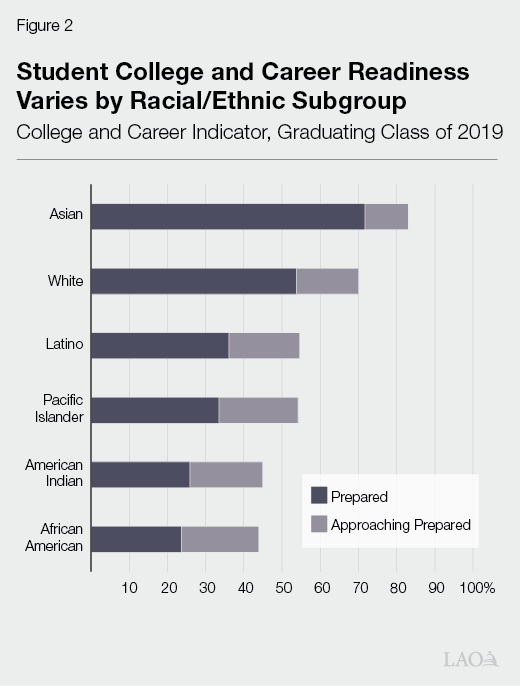

College and Career Indicator Part of State’s Accountability System. As part of the state’s accountability system, districts report various student outcome data to the state, which is then displayed on a public website known as the school dashboard. Under the state’s accountability system, school districts that have poor performance for one or more student subgroups based on these indicators must examine their root issues and access support to help them improve. The school dashboard includes a variety of data, including standardized test scores, graduation rates, and suspension rates. Another key indicator is the College and Career Indicator, which combines information about a student’s course completion and test scores. As Figure 1 shows, the indicator allows multiple ways for students to demonstrate they are “prepared” or “approaching prepared” for college and career. In 2018‑19, 44 percent of the state’s high school graduates were deemed prepared, 17 percent were approaching prepared, and 39 percent were not prepared. As Figure 2 shows, rates of preparation can vary substantially by racial/ethnic subgroups. Additionally, rates of preparation are far below the state average for homeless students (26 percent prepared), foster youth (13 percent prepared), and students with disabilities (11 percent prepared).

Figure 1

Description of College and Career Indicator

|

Prepared |

|

High school diploma and any one of the following measures: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Approaching Prepared |

|

High school diploma and any one of the following measures: |

|

|

|

|

|

Not Prepared |

|

No high school diploma or high school diploma but no measures met |

|

CTE = career technical education. |

State Has Several Existing K‑12 Programs Focused on Career Readiness. Figure 3 shows the two major programs—the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant (CTEIG) program, administered by CDE, and the K‑12 Strong Workforce Program (SWP), administered by the CCC Chancellor’s Office. Whereas the CTEIG program is intended to cover a broader range of goals beyond workforce training—such as student engagement and career exploration—the K‑12 SWP is primarily intended to address regional workforce needs.

Figure 3

State’s Two Major K‑12 Career Technical Education (CTE) Programs

Proposition 98 General Fund (In Millions)

|

Name |

Ongoing |

Description |

|

CTE Incentive Grants |

$300 |

Allocated on a competitive basis. Funds are disbursed based on a formula that considers the size of the CTE program. Priority given in eight different categories, including whether the program is in a rural area and whether it already uses other CTE funding, such as federal grants. Requires $2 local match for every $1 in state funding. |

|

K‑12 Strong Workforce Program |

150 |

Allocated to regional consortia based on a formula considering grades 7 through 12 attendance and regional workforce needs. Each consortium, in turn, awards grants to school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education on a competitive basis. Requires that grantees partner with a community college develop CTE opportunities and career pathways. Requires $2 local match for every $1 in state funding. |

Several Programs at the Community Colleges Support K‑12 College and Career Readiness Efforts. Several key community college programs are aligned with or provide support to existing K‑12 programs that promote college and career readiness. The state provides $290 million ongoing for the CCC SWP, which shares the same regional structure with the K‑12 SWP. Both programs are required to focus on regional workforce needs, with the K‑12 program intended to feed into CCC degree and certificate programs. In addition, the state provides community colleges about $200 million annually in apportionment funding for high school students dually enrolled in CCC courses (which we discuss further below). The state also provides $1.8 million ongoing in program support for “middle college high schools.” These schools are a partnership between a school district or charter school and a community college to operate a high school on a community college campus, targeted to students who are at a risk of dropping out of high school. (A similar model, known as “early college high school,” is a partnership between public schools and a CCC, CSU, or UC campus that allows students to earn a diploma and up to two years of college credit in four years or less.) In addition to the programs at community colleges, both UC and CSU have programs that provide outreach and recruitment to high schools to support students to enroll at a university after graduation.

Dual Enrollment Allows High School Students to Take College Level Courses. Credit from these college‑level classes may count toward both a high school diploma and a college degree. By graduating high school having already earned college credits, students can save money and accelerate progress toward a postsecondary degree or certificate. Dual enrollment has various models. California’s two most widely used models are traditional dual enrollment and College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP). Traditional dual enrollment typically consists of individual high school students taking college‑level courses on a community colleges campus. CCAP, on the other hand, allows cohorts of high school students to take college‑level classes on a high school campus. Under both dual enrollment models, the school district the student attends and the community college are typically able to claim apportionment funding for the time that students are taking the community college courses.

2018‑19 Budget Created Dual Enrollment Initiative Focused on College and Career Readiness. The Legislature provided CCC $10 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for the initiative, known as the “California STEM Pathways Grant Program.” Under the initiative, community college grantees collaborate with high schools and industry partners to create a school spanning 9th through 14th grades (that is, through lower‑division coursework at CCC). Participating community colleges and schools first enter into a CCAP agreement. Students in the program then take a mix of high school and community college courses that lead both to a high school diploma and a “no cost” associate degree in a designated science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) field (including manufacturing and information technology). Though the program is structured as a six‑year model, students can progress at their own pace and complete their associate degree in a somewhat faster or slower time period. In addition, students participate in work‑based experiences, such as internships and mentorships with local businesses. Upon graduation, students can choose to continue their education at a four‑year college or obtain an entry‑level job in the field they studied. Industry partners commit to giving program graduates first priority for relevant job openings. Statute requires the Chancellor’s Office to prioritize grants to applicants serving students from groups that have historically faced barriers to completing high school or college. The Chancellor’s Office also is required to report to the Legislature and Department of Finance by January 2025 on the outcomes of students who participated in the program—including the number and percentage of students who obtained an associate degree, gained full‑time employment in the area they studied, or enrolled in a four‑year college.

Governor’s Proposals

Provides $1.5 Billion One Time for Golden State Pathways. The proposal would create a new competitive grant program intended to improve college and career readiness. The program is to be administered by CDE and would fund the development of specific types of high school pathways programs. Funding would be available over five years. As Figure 4 shows, funding would be for three activities: implementation, regional planning, and technical assistance. Funding could be provided to school districts, charter schools, county offices of education, regional occupational centers, or programs operated by a joint powers authority. (For the remainder of this post, we refer to these entities as local education agencies or LEAs.) The proposal defines high‑priority LEAs as those that have (1) a majority of their student population consisting of English learners or low‑income students, or (2) higher than the state average rate of high school dropouts, suspensions or expulsions, child homelessness, foster youth, or justice‑involved youth. The proposal would give preference to high‑priority LEAs that seek to establish programs in education (including early education), computer science, health care, or STEM pathways that also focus on climate resilience. Grant recipients would be required to:

- Provide high school students a program that includes (1) an integrated program of study that incorporates all of the UC/CSU course requirements, and at least one of the other criteria to be considered prepared under the College and Career Indicator; (2) the opportunity to earn at least 12 college credits; (3) opportunities to participate in work‑based learning experiences, and (4) integrated support services to address a student’s social, emotional, and academic needs.

- Develop and integrate standards‑based academics with a sequenced curriculum aligned to high‑wage, high‑demand jobs.

- Provide articulated pathways from high school to postsecondary education and training that are aligned with regional workforce needs.

- Collaborate with other entities—such as institutions of higher education and employers—to increase the availability of college and career pathways that address regional workforce needs.

- Leverage available resources or in‑kind contributions from public, private, and philanthropic sources to sustain the ongoing operation of the pathways they develop.

Figure 4

Golden State Pathways Funding

Split Among Three Activities

Proposition 98 General Fund (In Millions)

|

Description |

Funding |

|

Implementation grants for local educational agencies (LEAs). |

$1,250 |

|

Grants to develop regional consortia and support collaborative planning. |

$150 |

|

Technical assistance grants. The California Department of Education can contract with up to ten LEAs for this purpose. |

$75 |

Under the proposal, grant recipients would be required to annually report data disaggregated by student subgroups in several areas, including academic performance, graduation rates, completion of UC/CSU course requirements, postsecondary outcomes, and employment outcomes. An evaluation of the program would be required to be completed between June 30, 2027 and June 30, 2028.

Provides $500 Million One Time to Increase Dual Enrollment. The funding would be split among three different grant types, as shown in Figure 5. As with the Golden State Pathways proposal, funding would be administered by CDE and allocated through a competitive grant process. Priority would be given to LEAs where at least half of their student population consists of English learners or low‑income students, as well as those that have higher than the state average rate of high school dropouts, suspensions or expulsions, child homelessness, foster youth, or justice‑involved youth. Funding would be available over five years.

Figure 5

Summary of Governor’s Proposed

Dual Enrollment Grants

Proposition 98 General Fund (In Millions)

|

Description |

Funding |

|

Up to $500,000 for enhanced student advising and success support. Can be spent over five years. |

$300.0 |

|

$250,000 for planning and starting up middle and early college high schools on K‑12 school sites. |

137.5 |

|

$100,000 to establish CCAP agreements that allow students to take some community college courses at their high school. |

62.5 |

|

CCAP = College and Career Access Pathways. |

|

Provides $20 Million One Time for Another Round of California STEM Pathways Grants. The Governor’s proposal is very similar to the initiative funded in the 2018‑19 budget. One difference is that the 2022‑23 proposal adds education (including early education) as an eligible field that students can study in the pathways program. In addition, the Governor’s proposal adds another reporting requirement (January 2029) for the Chancellor’s Office. As in 2018‑19, the Governor’s budget allows the Chancellor’s Office to decide on the number and size of the grants using the proposed funds. Also, like the 2018‑19 grants, grantees would have six years to spend their fund awards (aligned with the amount of time a 9th‑through‑14th grade cohort of students is to spend in the program).

Assessment

All Proposals Provide One‑Time Funding for Ongoing Activities. The administration indicates the one‑time funding in these proposals is intended to be used as start‑up costs to create or expand pathways and dual enrollment programs. However, the bulk of the costs associated with building and sustaining these programs—such as hiring staff, developing partnerships with industry, and purchasing instructional materials and equipment—are ongoing. Moreover, in the case of the $500,000 dual enrollment grants for academic support and advising, the funding appears to be covering an ongoing cost that, if not continued, would have no long‑term benefits. Although the expectation is that LEAs commit to sustaining the programs when grant funding expires, there is no guarantee that this would occur. Alternatively, the grantees that apply for and receive these funds may be LEAs that already were planning and committed to implementing these programs, regardless of whether they were to receive one‑time state funding.

Golden State Pathways Proposal Would Add More Complexity to State’s Approach to Funding College and Career Readiness. The Golden State Pathways proposal has several elements that are similar to the existing CTEIG and K‑12 SWP. Most notably, it is intended to be aligned with regional workforce needs and include partnerships with industry and institutions of higher education. However, the program has a significant number of additional program requirements, such as having pathways be aligned with UC/CSU course requirements and providing students with integrated support services. There could be benefits to encouraging LEAs to implement programs of this type, as they can provide students with greater options after high school. However, enacting this proposal would leave LEAs often operating programs with three different sources of funding and three different program rules. Such a fragmented approach can make implementing well aligned and coordinated programs administratively and fiscally challenging for LEAs.

Little Details Around Key Aspects of Golden State Pathways Proposal. The Governor’s proposal sets clear expectations for the types of pathways programs grant recipients must develop and requires grantees to submit a robust set of outcome data that will help inform the required evaluation of the program. However, the proposal also lacks critical details, such as the amount of funding grantees would receive and the allowable uses of the funds. These decisions are left to the Superintendent of Public Instruction, in consultation with the State Board of Education. Without these details, it is difficult for the Legislature to assess the program’s potential benefits. This is particularly relevant given the robust requirements included in the proposal.

No Clear Fiscal Barriers to Implementing Dual Enrollment. Research suggests that dual enrollment can be an effective model for improving college preparation. Moreover, the state supports an extensive amount of dual enrollment through several program models. In proposing additional funding for dual enrollment, however, the administration fails to identify what problem currently exists with dual enrollment. In particular, the administration does not specify what barriers LEAs currently face in implementing dual enrollment programs and how additional funding might help remove these barriers. For example, most of the proposed funding for dual enrollment is intended to increase the level of student support services, such as tutoring. Yet, the administration does not specify how current funding to support students is inadequate at high schools and community colleges. Given that community colleges currently are receiving funding from the state far in excess of their enrollment levels, we question whether students—including dually enrolled students—have inadequate access to tutors, counselors, and other support staff. In the case of CCAP, it is not clear that funding barriers exist at all. Full‑time equivalent enrollment in CCAP programs has grown to almost 18,000 students in just a few years. In 2020‑21, CCAP enrollment grew by 22 percent from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21, even as overall community college enrollment declined by 8 percent. Moreover, rather than posing fiscal barriers, CCAP funding policies can work to the benefit of schools and colleges. This is particularly the case when students take CCAP courses in place of their regular high school coursework. In such cases, schools can receive attendance‑based funding even though they may only be providing three hours (rather than the standard six hours) of instruction per day. (For more background on dual enrollment, please see our 2021‑22 analysis of a proposal to fund dual enrollment instructional materials.)

Little Information Available Regarding Current STEM Pathways Grant Program. The program is based on a decade‑old model aimed at combining education and workforce development through dual enrollment and industry partnerships. Though the model has been implemented in other states and countries, it is relatively new to California. To better assess the merits of the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature thus would benefit from a basic status update on how the currently funded $10 million initiative is working (recognizing that the report due in 2025 will have more complete outcomes data). For example, our understanding is that the Chancellor’s Office awarded $10 million in grants to a total of six community colleges in early 2019 and that programs generally began enrolling 9th grade students in fall 2019 or fall 2020. (The Chancellor’s Office originally offered seven grants but only six community colleges met minimum application requirements.) It is unclear, however, how many students began these programs, how many are still enrolled, and the progress they are making toward a high school diploma and acquiring college credits. In addition, since the program is designed to focus on supporting underserved youth, the Legislature would benefit from receiving data on the demographics of students in these programs. Without the above information, it is difficult for the Legislature to know whether the Governor’s proposal to fund another round of grants would be an effective approach to increasing college and career readiness.

Proposals Do Little to Target Funding to Schools and Students That Would Benefit Most. For the Golden State Pathways and dual enrollment proposals, the administration defines high‑priority LEAs as those with at least half of their student population consisting of English learners or low‑income students, as well as any LEA with a higher than the state average rate of high school dropouts, suspensions or expulsions, child homelessness, foster youth, or justice‑involved youth. Such a broad definition of priority is unlikely to have much effect on targeting the proposals to LEAs with students that have the greatest need. Based solely on one priority measure—that more than half of students be low income or English Learners—at least two‑thirds of school districts would be designated as meeting the high‑priority characteristics. (Using the other measures, additional districts would also be eligible.) In addition, neither the Golden State Pathways nor the dual enrollment proposals require districts to target programs to the schools or student populations in their district with the lowest outcomes. This could result, for example, in districts using funding to benefit programs at their higher‑performing high schools without implementing similar programs at their lower‑performing high schools.

Recommendations

Request the Administration Provide More Information on Golden State and Dual Enrollment Proposals. As the Legislature evaluates these proposals, we recommend it request more information from the administration prior to the May Revision, in order to fully assess their potential benefits and shortcomings. Specifically, we suggest requesting responses to the following questions:

- How does the administration expect LEAs to coordinate funding from Golden State Pathways and other CTE programs into a coherent approach for serving students?

- What considerations is the administration taking to decide how to set grant amounts for the Golden State Pathways program?

- What does the administration see as the key barriers to dual enrollment? Why does the administration believe additional funding is necessary given the fiscal incentives that already exist?

- Why is the administration proposing one‑time funding for programs that will need ongoing support?

- How will the administration ensure that funding is being distributed in an equitable manner that targets the students that could benefit most from high‑quality high school programs?

Direct Chancellor’s Office to Report at Spring Hearings About Current STEM Pathways Program. By obtaining a status update on the six programs that received a grant in 2018‑19, the Legislature would be in a better position to make an informed decision about the Governor’s proposal. In addition, given that only six grants were awarded in 2018‑19, the Legislature should request the administration to explain how it determined the amount proposed for 2022‑23 and share any indications it has that enough interest and demand exists from college, school, and industry partners to justify the requested amount. The Legislature could use information to help weigh the Governor’s proposal against other one‑time legislative spending priorities for 2022‑23.

Consider Ways to Target Schools and Students With Highest Need. If the Legislature chooses to adopt the Golden State Pathways or dual enrollment proposals, it could modify the proposals to prioritize a smaller subset of districts. For example, it could designate a high‑priority LEA as one where at least 75 percent of the student population is low income or an English learner. This would restrict priority to the top one‑third of school districts. To increase the likelihood that grant funds ultimately benefit students with the greatest needs, the Legislature could consider requiring that grantees demonstrate they will be implementing these programs equitably across various school sites and in a way that is targeted to benefit student subgroups with lowest college and career outcomes.