LAO Contact

- Rachel Ehlers

- Community Resilience

- Sarah Cornett

- Zero-Emission Vehicles

- Energy

- Frank Jimenez

- Sustainable Agriculture

- Circular Economy

- Helen Kerstein

- Wildfire and Forest Resilience

- Nature-Based Activities

- Extreme Heat

- Parks, Museums, and Access

- Sonja Petek

- Water and Drought

- Coastal Resilience

February 22, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions

- Introduction

- Discussion of Governor’s Overall Approach

- Discussion of Specific Proposals

- Zero‑Emission Vehicles

- Energy

- Water and Drought

- Wildfire and Forest Resilience

- Nature‑Based Activities and Extreme Heat

- Community Resilience

- Sustainable Agriculture, Circular Economy, and Other Recent Augmentations

- Parks, Museums, and Access

- Coastal Resilience

- Potential Additional or Alternative Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions

Executive Summary

In response to the multibillion‑dollar budget problem the state is facing, the Governor’s budget proposal identifies significant solutions from recent augmentations made to climate, resources, and environmental programs. This report describes the Governor’s proposals and provides the Legislature with a framework and suggestions for how it might modify those proposals to better reflect its priorities and prepare to address a potentially larger budget problem. The report begins with a discussion of the Governor’s overall approach, then walks through each of the Governor’s proposed solutions within nine thematic areas, including describing and commenting on many of the specific proposals.

Recent Budgets Included Significant General Fund Augmentations for Climate, Natural Resources, and Environmental Programs. Combined, the 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget packages included $27 billion—primarily from the General Fund—for a wide variety of activities related to mitigating and responding to climate change, as well as for protecting and restoring natural resources and the environment. These recent budgets also included agreements to provide additional General Fund support in the out‑years to continue these activities—including $8.7 billion in 2023‑24—for a five‑year total of $40.2 billion.

Governor Proposes $5.8 Billion in General Fund Solutions Across Five Years From These Programs. The Governor’s budget proposal would generate $5.5 billion in General Fund savings from climate, resources, and environmental programs in 2023‑24—$3.8 billion from spending reductions, $875 million from reducing General Fund and backfilling with a different fund source (primarily the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, or GGRF), and roughly $800 million from delaying spending to a future year. The proposal includes additional net savings of $300 million in the out‑years ($1.1 billion from further reductions and fund shifts, largely offset by the resumption of the delayed expenditures). The proposed approach differs by thematic area. For example, the Governor proposes reducing close to half of all the recent and planned augmentations for coastal resilience activities, but—largely due to shifting some planned program expenditures from the General Fund to GGRF—would maintain about 90 percent of intended funding for zero‑emission vehicle programs.

While Important Needs Remain, Identifying Budget Solutions From These Programs Is Appropriate Given Magnitude of Recent Augmentations. As evidenced by the flooding, drought conditions, heat waves, and severe wildfires that Californians have experienced over the past year, a changing climate presents the state with significant challenges. As such, maintaining key activities supported by recent funding augmentations is important to making progress in addressing the causes and impacts of climate change. However, given the scale of the recent spending increases, even reduced amounts still will represent significant augmentations compared to historical levels for most of these programs, particularly since many of these activities have not typically received General Fund support. Additionally, because making reductions to newly initiated activities and one‑time expenditures is usually less disruptive than cutting ongoing programs and associated staff, these types of programs represent a reasonable area to focus some of the solutions needed to address the budget problem. Indeed, the Governor and Legislature chose to spend most of the recent General Fund surpluses on one‑time expenditures as a form of budget resilience, with the expressed goal of avoiding making ongoing commitments that would be hard to sustain should economic conditions change. As such, making reductions to these programs can allow the Legislature to take advantage of the flexibility that was envisioned when crafting recent budgets. Moreover, given the magnitude of solutions needed to solve the anticipated budget problem, a significant focus on these one‑time augmentations likely is necessary if the Legislature wants to avoid cutting ongoing programs in this or other policy areas. Through careful prioritization, the state can continue to make significant progress on its climate and environmental goals even at moderately reduced spending levels.

Governor’s Overall Approach Is Reasonable, but Specific Choices Reflect Administration’s Priorities. Overall, we find the Governor’s proposed approach for crafting budget solutions within climate, resources, and environmental programs to be reasonable—however, it represents just one possible strategy. Because of the quantity and magnitude of recent programmatic expansions in these programs, the Legislature has numerous options for selecting a different and equally sensible package of choices that achieves roughly the same—or, as may be necessary, an even greater amount—of budget solutions as the Governor’s, but that includes the activities it believes are most important to sustain.

Recommend Legislature Adopt Package of Budget Solutions Based on Legislative Prioritization Criteria. We recommend the Legislature develop its own package of budget solutions based on its priorities and guiding principles. Some criteria we suggest the Legislature consider include: (1) preserving activities that reflect key legislative priorities and goals, including targeting vulnerable communities that may not have the resources to undertake important activities on their own; (2) preserving funding that is needed urgently to meet pressing needs; (3) avoiding budget solutions that would cause major disruptions, such as reducing funding that has already been committed to specific projects and grantees; and (4) considering whether other resources—such as previous budget appropriations, special funds, or federal funds—might be available to help accomplish intended activities. As the Legislature modifies program funding levels, we recommend that it also consider whether it might want to refine or refocus some program features to ensure that remaining funding targets the most important populations, activities, and desired outcomes. Other overarching recommendations to the Legislature as it crafts its solutions package include:

- Be selective when opting to delay—rather than maintain or reduce—funding.

- Reject the Governor’s General Fund trigger restoration approach to maintain legislative flexibility.

- Reject or modify the Governor’s proposed GGRF trigger approach to maintain legislative flexibility.

- Use the spring budget process to identify additional potential budget solutions for climate, resources, and environmental programs.

- Weigh the relative priority of new spending against existing commitments.

- Request additional information from the administration on the availability of federal funding.

- Conduct robust oversight of spending and outcomes and consider whether additional program evaluations might be worthwhile.

While we do not discuss every individual program proposal or craft a comprehensive alternative package of solutions, throughout the thematic sections of this report we provide examples of alternative solutions the Legislature could consider and identify specific proposals that raise some concerns.

Introduction

In response to the multibillion‑dollar budget problem the state is facing, the Governor’s budget proposes reducing net General Fund spending by $5.8 billion across five years from climate, resources, and environmental programs. This includes $4.7 billion affecting the 2023‑24 budget—$3.8 billion in net spending reductions and $875 million from shifting spending to different fund sources. The Governor would generate an additional roughly $800 million in budget‑year savings by delaying funding for certain programs to a future year. The Governor also includes a few new spending proposals for climate, resources, and environmental programs. This report describes the Governor’s proposals and provides the Legislature with a framework and suggestions for how it might modify those proposals to (1) better reflect its priorities, and (2) prepare to address a potentially larger budget problem.

The report begins with a discussion of the Governor’s overall approach, including background on recent funding augmentations and the state’s budget problem; a high‑level overview of the Governor’s proposals for climate, resources, and environmental programs; our overarching assessment of his proposed approach; and recommendations for how the Legislature could proceed, including suggested criteria the Legislature could use to craft its own package of solutions.

We then walk through each of the Governor’s proposed solutions by thematic area, including describing and commenting on many of the specific proposals. While we do not discuss every individual program proposal or craft a comprehensive alternative package of solutions, we provide examples of alternative solutions the Legislature could consider and identify specific proposals that raise some concerns. These thematic areas include:

- Zero‑Emission Vehicles (ZEVs).

- Energy.

- Water and Drought.

- Wildfire and Forest Resilience.

- Nature‑Based Activities and Extreme Heat.

- Community Resilience.

- Sustainable Agriculture, Circular Economy, and Other Programs.

- Parks, Museums, and Access.

- Coastal Resilience.

We conclude the report with a summary of potential additional or alternative options the Legislature could consider for each thematic area.

Discussion of Governor’s Overall Approach

Background

Recent Budgets Included Significant General Fund Augmentations for Climate, Natural Resources, and Environmental Programs. Recent budgets included noteworthy amounts of new spending, mostly grouped into thematic packages. Figure 1 highlights most of this funding. (Some augmentations that were provided outside of these thematic packages are not included in the figure.) As shown in the figure, recent budgets provided $27.7 billion in 2020‑21 through 2022‑23 for a wide variety of activities related to mitigating and responding to climate change, as well as for protecting and restoring natural resources and the environment. This spending is spread across numerous departments and is primarily from the General Fund, but does include $6.4 billion from special funds, mostly the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) and Proposition 98 (for zero‑emission school buses). These budget packages also included agreements to provide additional General Fund support in the out‑years—including $8.8 billion in 2023‑24—for a five‑year total of $40.2 billion. In general, these augmentations were all for activities that were one‑time or limited‑term in nature, such as providing grants for local entities to construct infrastructure or undertake habitat restoration projects. Some of the augmentations provided funding for activities to be undertaken by state agencies, such as to secure additional electricity resources intended to ensure summer electric reliability. In most cases, the augmentations displayed in the figure represent unprecedented levels of General Fund for these types of programs, many of which historically have been supported with special funds or bond funds. In some cases, this has allowed the state to expand previous programs or initiate new activities, while in others the state is providing General Fund support to continue existing activities that were previously supported with other fund sources.

Figure 1

Recent and Planned Augmentations to Climate, Resources, and Environmental Programs

(In Millions)

|

Thematic Area |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Totals |

|

Zero‑Emission Vehicles |

— |

$3,351 |

$3,168 |

$2,107 |

$858 |

$460 |

$9,944 |

|

Energy |

— |

2,425 |

3,002 |

2,626 |

654 |

918 |

9,625 |

|

Water and Drought |

— |

5,508 |

1,435 |

1,119 |

133 |

558 |

8,752 |

|

Wildfire and Forest Resilience |

526 |

968 |

630 |

690 |

— |

— |

2,814 |

|

Nature‑Based Activities and Extreme Heat |

10 |

176 |

1,384 |

743 |

— |

— |

2,314 |

|

Community Resilience |

— |

522 |

935 |

715 |

— |

— |

2,172 |

|

Sustainable Agriculture, Circular Economy, and Other Programs |

— |

944 |

795 |

33 |

— |

— |

1,771 |

|

Parks, Museums, and Access |

— |

915 |

420 |

88 |

96 |

27 |

1,548 |

|

Coastal Resilience |

— |

19 |

606 |

652 |

19 |

— |

1,295 |

|

Totals |

$536 |

$14,827 |

$12,376 |

$8,773 |

$1,760 |

$1,963 |

$40,236a |

|

aIncludes $33.7 billion from the General Fund and $6.4 billion from other fund sources, including the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund and Proposition 98. |

|||||||

State Faces a Multibillion‑Dollar Budget Problem. Due to a deteriorating revenue picture relative to expectations from June 2022, both our office and the administration have anticipated that the state faces a budget problem in 2023‑24. A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when funding for the upcoming budget is insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. Estimates of the magnitude of this shortfall differ based on how “baseline” spending is defined—the administration estimates a $22 billion problem whereas our office estimates that the Governor’s budget addresses an $18 billion problem. Regardless of these technical definitions, it is clear that—absent a major and unexpected jump in state revenues—the state faces the task of “solving” the budget problem. The Governor proposes to address the problem primarily by reducing spending, and targets the climate, resources, and environmental policy areas for the largest proportional share of these solutions. (We discuss the overall budget condition in our recent reports, The 2023‑24 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget and The 2023‑24 Budget: Multiyear Assessment.)

Budget Outlook Could Actually Be Even Worse. While the Governor’s budget is balanced under the administration’s estimates for 2023‑24, the administration forecasts operating deficits of $9 billion in 2024‑25, $9 billion in 2025‑26, and $4 billion in 2026‑27. That is, if the Governor’s budget projections are accurate, the state would have to address deficits of these amounts in each of these future years. Moreover, our office’s estimates suggest there is a good chance that revenues will be lower than the administration’s projections for 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. Thus far, neither the administration nor our office is forecasting a recession; rather, our weaker revenue estimates represent a slowdown from the extraordinary economic growth in recent years. However, we do see certain economic signs that suggest a heightened risk of a potential recession. Should a recession occur, the state’s revenue shortfall would be considerably larger than current forecasts from either the administration or our office. Given this downside risk, in our recent budget reports, we recommended that the Legislature: (1) plan for a larger budget problem and (2) address that larger problem by reducing more one‑time and temporary spending.

Governor’s Proposals

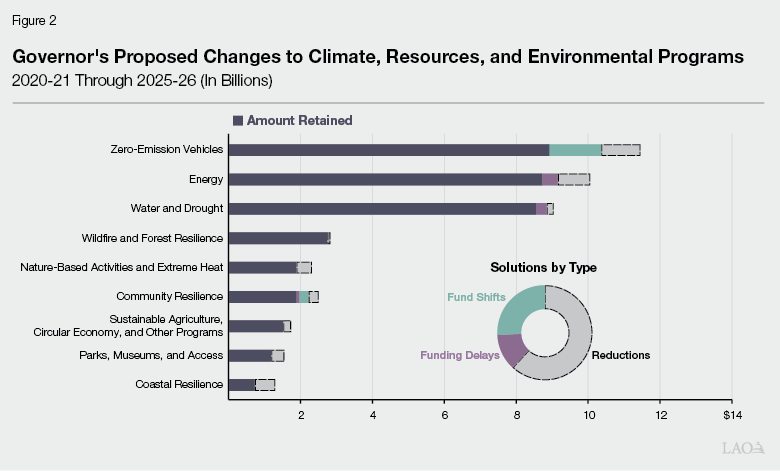

Uses Three Strategies to Generate $5.8 Billion in General Fund Solutions Across Five Years From Climate, Natural Resources, and Environmental Protection Programs. The Governor relies on three strategies to achieve General Fund savings from climate, resources, and environmental programs: reductions, fund shifts, and funding delays. This includes $5.5 billion in General Fund savings in 2023‑24—$3.8 billion from spending reductions, $875 million from reducing General Fund and backfilling with a different fund source, and roughly $800 million from delaying spending to a future year. The proposal includes additional net savings of $300 million in the out‑years—$1.1 billion from further reductions and fund shifts, largely offset by the resumption of the delayed expenditures. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s proposed approach differs by thematic area. The figure also shows that for each area, the Governor proposes maintaining the majority of intended funding—using General Fund or a different source—across the five years.

- Reductions. The Governor reduces funding for selected programs. In some of these cases, the proposal is to rescind funding that was provided in the current or prior year that departments have not yet expended. In others, the Governor proposes not providing funding in 2023‑24 that was pledged as part of a recent budget agreement. For some programs the Governor partially reduces the intended funding levels, and for others the proposal completely eliminates the funding. Reductions are the strategy through which the Governor generates the most savings across the five years ($4.1 billion, or 62 percent), as displayed in Figure 2. This includes $3.8 billion scored towards solving the 2023‑24 budget problem.

- Fund Shifts. The Governor achieves additional savings by reducing or eliminating the intended General Fund for a program, but then backfilling it with funding from other sources—primarily using GGRF. The Governor would dedicate nearly all of the proposed 2023‑24 discretionary GGRF expenditures—as well as amounts in future years—to backfill General Fund reductions. The Governor mentions the possibility of pursuing a general obligation bond for replacing or supplementing some program funding, but has not submitted a formal proposal to do so nor linked any specific program changes to potential bond funding. (A general obligation bond would have to be repaid from the General Fund and would require voter approval.) Similarly, the Governor mentions the potential availability of federal funds to help offset General Fund reductions, but does not propose any explicit shifts from state funds to federal funds. The proposal includes a total of $1.7 billion in fund shifts, including $875 million scored towards solving the 2023‑24 budget problem.

- Funding Delays. The Governor also proposes delaying intended funding for certain programs, with the intent to provide it in a future year rather than in 2022‑23 or 2023‑24. This would achieve General Fund savings in the budget year, but shift the associated costs to a future year. The proposal includes a total of about $800 million in funding delays, all scored towards solving the 2023‑24 budget problem.

Suggests Some Proposed Reductions Could Be Restored if General Fund “Trigger” Conditions Are Met. The Governor’s proposal includes language that would allow $2.2 billion—just over half—of the proposed reductions highlighted in Figure 2 to be restored in the middle of 2023‑24 if the administration at that time estimates that the state has sufficient resources to fund these expenditures. Specifically, if in January 2024 the administration estimates that the state has sufficient General Fund resources to fund both its other baseline costs and these expenditures, funding for the associated programs would be restored halfway through the fiscal year. In order for any of these restorations to occur, however, the administration would have to determine that the state has sufficient resources to fund all of the identified programs subject to the trigger. If the administration determines the state does not have sufficient resources, none of the restorations would occur. The trigger restoration list totals $3.8 billion across the budget and includes some programs outside of the climate, resources, and environmental policy areas.

Also Proposes Trigger Restoration Approach for GGRF. The Governor proposes a separate trigger restoration approach for GGRF revenues that the state may receive above the administration’s current estimates. Specifically, proposed budget control section language would require the administration to allocate additional discretionary GGRF revenue to backfill more of the proposed reductions to ZEV programs. Under this proposal, the Director of the Department of Finance (DOF) would have the discretion to determine which ZEV programs to augment and at what levels.

Governor Also Proposes Some New Discretionary Climate and Natural Resources Spending. In addition to the above budget solutions, the Governor has a few significant new General Fund spending proposals for climate and natural resources programs. (These are in addition to numerous baseline increases across many departments, such as for funding to implement recently passed legislation, which we do not consider “discretionary.”) The major proposed augmentations include the following, most of which we discuss in more depth in separate publications:

- California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) new training center and conservation camp replacement ($37 million in 2023‑24, with commitment for $495 million in future years for capital outlay, as well as ongoing operations costs of between $3 million and $12 million annually). (Please see our brief, The 2023-24 Budget: California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection’s Major Capital Outlay Proposals.)

- Various flood management activities ($139 million one time). (Please see our brief, The 2023-24 Budget: Department of Water Resources.)

- Drought contingency fund ($125 million one time).

- ZEV charging infrastructure at state buildings ($35 million one time).(Please see our brief, The 2023-24 Budget: Governor’s Proposals for the Department of General Services.)

- Expanded Sustainable Groundwater Management Act staffing ($14 million annually). (Please see our brief, The 2023-24 Budget: Department of Water Resources.)

- Expansion of California Volunteers Climate Action Corps ($4.7 million annually for three years, growing to $9.5 million annually starting in 2026‑27). (Please see our brief, The 2023-24 Budget: California Volunteers Proposed Program Expansions.)

Overarching Assessment

Need for Climate, Resources, and Environmental Programs Remains… As evidenced by the flooding, drought conditions, heat waves, and severe wildfires that Californians have experienced over the past year, a changing climate presents the state with significant challenges. Escalating climate change impacts will continue to threaten public health, safety, and well‑being—including from life‑threatening events, damage to public and private property and infrastructure, and impaired natural resources. The unprecedented funding augmentations that the Legislature committed in recent budgets represent a significant step in the state’s efforts to help mitigate these effects, along with pursuing other major state goals such as reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, increasing energy reliability, and restoring and protecting natural habitats. Maintaining key activities supported by this funding is important to making progress in addressing the causes and impacts of climate change.

…However, Given Magnitude of Recent One‑Time Augmentations, Identifying Budget Solutions From These Programs Is Appropriate. Across the budget, the Governor targets the climate, resources, and environmental policy areas for the largest share of budget solutions. This is due in part to the fact that these policy areas also received the largest proportional share of one‑time General Fund spending from recent budget surpluses. Specifically, these programs represented about $20 billion, or nearly one‑quarter, of the state’s $87 billion in one‑time expenditures from the General Fund surplus from 2018‑19 through 2022‑23. (This total excludes constitutionally required spending for schools and community colleges pursuant to Proposition 98.) In addition, many of the programs supported by these funds represent new activities that are just getting up and running. Because making reductions to newly initiated activities and one‑time expenditures usually is less disruptive than cutting ongoing programs and associated staff, these types of programs represent a reasonable area for the Governor—and Legislature—to focus some of the solutions needed to address the budget problem. Indeed, the Governor and Legislature chose to spend most of the recent surpluses on one‑time expenditures as a form of budget resilience, with the expressed goal of avoiding making ongoing commitments that would be hard to sustain should economic conditions change. As such, making reductions to these programs can allow the Legislature to take advantage of the flexibility that was envisioned when crafting recent budgets. Moreover, given the magnitude of solutions needed to solve the anticipated budget problem, a significant focus on these one‑time augmentations likely is necessary if the Legislature wants to avoid cutting ongoing programs in these or other policy areas. Although making reductions in these policy areas will result in fewer of the one‑time activities that the Legislature intended for the state to conduct, even reduced amounts still will represent significant augmentations compared to historical levels for most of these programs. This is particularly true since many of these activities have not typically received General Fund support. Through careful prioritization, the state can continue to make significant progress on its climate and environmental goals even at moderately reduced spending levels.

Overall Approach Is Reasonable, but Specific Choices Reflect the Governor’s Priorities. Given the significant budget problem facing the state, we find the Governor’s overall approach for solutions from climate, resources, and environmental programs to be reasonable. As we discuss in the subsequent thematic sections of this report, in many cases, we find the Governor’s rationale for many specific programmatic choices to be credible. For example, many of the proposed solutions focus on programs for which funds have not yet been committed to specific projects, where other fund sources are available to help compensate for the loss in General Fund, or where reduced funding would allow some of the activities to continue but at a lower level. However, the proposals represent an expression of the Governor’s prioritization criteria, and the efforts that the administration believes are most—or least—important to sustain. While the Governor selects many programs for funding reductions, the proposals would leave even more programs untouched. Notably, many of the programs that the Governor suggests reducing are those for which the Legislature advocated during budget negotiations in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, rather than those which were first proposed through the Governor’s January and May budget proposals. For example, as shown in Figure 2, the Governor proposes cutting roughly $560 million (43 percent) from the multiyear budget agreement for coastal resilience activities, most of which was added to the final budget package by the Legislature.

Additionally, the Governor focuses about one‑third of proposed reductions on 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 appropriations, with about two‑thirds from funding intended for 2023‑24 and future years. However, the proposals still leave a significant portion of planned budget‑year and future amounts unaffected. While this approach could make sense in some cases—such as if circumstances have delayed departments from spending prior‑ and current‑year funds—in other instances avoiding appropriating budget‑year funding in the first place could be less disruptive for departments and other entities than taking back existing funding. This is because expenditure plans likely are not as far along for funding that the departments do not yet have the legal authority to spend.

Legislature Could Apply Its Own Criteria, Select Different Set of Solutions. The Governor’s proposed approach for crafting budget solutions within climate, resources, and environmental programs represents one possible approach. Because of the quantity and magnitude of recent programmatic expansions in these programs, however, the Legislature has numerous options for selecting a different and equally reasonable package of choices that achieves roughly the same—or, as may be necessary, an even greater amount—of budget solutions as the Governor’s but that reflects legislative priorities. For example, this could include (1) a different mix across programs within a thematic area (such as across Energy programs); (2) a different mix across climate, resources and environmental thematic areas (such as more budget solutions from water spending and less from coastal resilience programs); (3) a different mix across budget policy areas (such as more solutions from higher education programs and less from climate programs); (4) a different mix of solution strategies (such as more reductions and fewer delays); and (5) less new spending than the Governor proposes. The Legislature could also look at making reductions to programs funded with special funds—such as 2022‑23 appropriations from GGRF that have not yet been expended by departments and are deemed a lower priority—to free up additional funding that could offset the impact of General Fund reductions. As we discuss below, the Legislature could apply its own prioritization criteria to guide its choices in building its solutions.

As Legislature Modifies Funding Levels, It Could Also Consider Refocusing Programs. Alongside its decisions to reduce funding for certain programs, the Legislature may want to also take the opportunity to refine the design of those programs to help ensure that remaining funding is targeted towards achieving the most important desired outcomes. For instance, this could mean adopting budget bill language giving administering departments more guidance on how to prioritize funds, such as by limiting funding eligibility to underserved communities or to focus on those activities or projects that have been shown to be most effective. Similarly, the Legislature could specify whether it wants departments to implement funding reductions by decreasing the amount of each grant they award, or, alternatively, to keep the grants at the same level and just award fewer of them. In some instances, the Legislature may want to scale back funding originally intended to be spread across multiple years and instead fund an initial year on a pilot basis before making a larger commitment. In such cases, adding data collection and reporting requirements could help the state learn about the effectiveness of the pilot effort to inform future funding decisions.

Data Indicate Significant Amount of Funding Has Not Yet Been Committed. As of early February 2023, information provided by the administration indicates that approximately $11.4 billion of the $27 billion provided in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 for climate, resources and environmental programs has not yet been committed to or spent on specific projects. In many cases, this is because programs were recently established with the new funding and require time to hire staff, develop program guidelines, and implement grant solicitations and awards processes. While the Governor has already proposed some of the applicable programs for reductions or delays (totaling about $1.4 billion), clearly that is not the case for all of them. Departments are in the process of awarding some of these funds in the coming months—meaning they are not ideal for reducing—but others represent options that the Legislature could consider for identifying additional solutions. As we discuss below, we think that one principle the Legislature should use to guide its decisions is to avoiding making reductions to programs that are already relatively far along in their implementation processes, since that can result in disruption for local grantees and their projects—including, potentially, prohibiting them from completing projects they have already begun carrying out. However, programs with large balances of uncommitted funds may indicate cases where programs still are in the early stages of implementation and thus reductions or delays could be made without significant disruptions. We highlight some specific examples in the subsequent thematic sections of this report.

Governor’s General Fund Trigger Restoration Approach Not Realistic, Minimizes Legislative Authority. As noted, of the $3.8 billion in proposed reductions to climate, resources and environmental programs in 2023‑24, the Governor identifies $2.2 billion as being eligible for restoration should revenues exceed expectations by January 2024. We find this trigger proposal to be misleading in that it portrays the necessity for these reductions as being less certain than we think it is, and creates a false sense of hope—particularly for potential grant recipients and other stakeholders—that the reductions may not be implemented. As discussed earlier, not only do the administration’s revenue estimates assume insufficient funds to trigger such a restoration, but the administration also forecasts a $9 billion budget deficit for 2024‑25 that will need to be addressed. Moreover, the way the Governor has structured the trigger proposal would require sufficient resources to restore the full $3.8 billion budget‑wide trigger restoration list. Given other budget formulas—such as Proposition 98—this means that revenues likely would have to exceed his projections by about $7 billion in order for these restorations to occur. Since our revenue outlook is less optimistic than the Governor’s, we find it unlikely the trigger will be met. Specifically, we estimate there is about a one‑in‑three chance that the state will be able to afford the Governor’s budget as proposed for 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, and an even lower chance that the state could afford the Governor’s budget plus the trigger restorations. As such, we think the Legislature should consider the proposed trigger reductions as indistinct from the non‑trigger reduction proposals, and assume that they will be needed. Indeed, as we discuss below, we think a strong possibility exists that the Legislature will need to identify an even greater magnitude of budget solutions.

Additionally, an automatic trigger is not needed to make midyear funding augmentations—the Legislature already has this ability through its authority to pass midyear spending bills. As such, we find that the Governor’s proposal is structured in a way that reduces legislative authority and flexibility. First, it grants the Director of DOF sole responsibility for determining whether resources are in “excess” of existing spending commitments, which allows significant room for the Director to make subjective decisions (such as how to define those commitments). Second, the proposal does not provide the Legislature with the opportunity to modify the identified spending priorities once the revenue situation has become clearer. This is because all of the programs in the proposed trigger would either be “on” or “off,” even if legislative priorities change or if revenues might be sufficient to allow for some but not all of the restorations.

GGRF Trigger Proposal Also Raises Concerns. We have similar concerns about the Governor’s proposal to allow the Director of DOF to allocate potential midyear increases in GGRF revenues. Historically, the Legislature has opted to delay action on any additional GGRF revenues that materialize midyear and allocate them as part of the subsequent year’s budget package. This approach allows the Legislature the discretion to consider its highest priorities for that spending as part of a more comprehensive discussion, which also often includes consideration of the impact of those activities recently supported by GGRF and a desired level of fund balance to maintain. When midyear adjustments have been necessary due to GGRF revenues coming in lower than expected, the administration has cut programs proportionally (rather than making discretionary decisions to prioritize some over others). Allowing the administration to select which ZEV programs it would fund with any potential new monies and at what levels—without any statutory direction from the Legislature‑shifts too much decision‑making authority away from the Legislature to the administration.

Proposed Fund Shifts Would Have Programmatic Impacts. The Governor’s proposals to shift some program costs from the General Fund to other sources have some merit, as this approach can allow planned activities to continue while also helping to solve the state’s budget shortfall. However, such fund shifts are not without impacts. For example, the Governor’s proposal to use all of the discretionary GGRF revenue in 2023‑24—roughly $860 million—as well as commit GGRF revenues from future years to help sustain planned ZEV and “AB 617” community air protection program expenditures would benefit those programs. However, this strategy would leave the state without those funds to use for other programs that GGRF discretionary monies typically have supported. For example, in recent years, GGRF has been used for programs that reduce methane emissions, support climate change research, replace agricultural diesel engines, and limit short‑lived climate pollutants. The choice before the Legislature is whether backfilling the General Fund to sustain intended funding for the ZEV and AB 617 programs is a higher priority than other programs for which GGRF could be used. The Legislature could also use GGRF to backfill General Fund reductions for other climate programs instead of those selected by the Governor.

Potential for Federal Funds Could Help Ease—but Not Fully Backfill—Proposed General Fund Reductions. While we see advantages to the Governor’s suggested strategy of identifying federal funds to help offset some proposed General Fund reductions, this strategy also comes with trade‑offs. Specifically, while federal programs may fund activities similar to those supported by the state’s programs, typically they would not provide an identical dollar‑for‑dollar match. Federal programs may have different eligibility criteria or allowable activities than state programs. For example, some federal funding for coastal projects focuses more on nature‑based activities to address sea‑level rise rather than on other resilience efforts that state funds support, such as land acquisitions or shoring up critical public infrastructure. Moreover, some federal programs often require state departments or local governments to apply and compete for funding against entities from across the nation, making it uncertain whether California‑based projects ultimately would benefit from the same total amount of funding as a General Fund allocation would have guaranteed. Some federal programs also require a state or local funding contribution, which can result in higher barriers to access than some state programs. Indeed, state or local entities may have been planning to use some of the recent state augmentations to meet such matching fund requirements in order to be eligible for funding from federal programs. Additionally, some federal programs are structured in ways that provide different forms of benefits than state programs. For instance, Californians who do not file taxes—including some lower‑income households—cannot benefit from the tax credits provided through the federal ZEV incentive program, but are eligible for rebates from the state’s program.

While these distributional differences are important considerations for the Legislature to keep in mind, the recent large increases from federal spending bills do offer a unique and helpful opportunity to at least partially mitigate some state spending reductions made necessary by California’s budget situation. As such, taking federal fund availability into account when crafting budget solutions is worthwhile. Given the quantity of new and augmented programs in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act, the Legislature would benefit from additional assistance from the administration to fully understand the landscape and nuances of federal funds that might be available.

Governor Uses Portion of Budget Solutions to “Make Room” for Proposed New Spending. As highlighted above, along with the proposed reductions, the Governor’s budget also includes a few notable new General Fund spending proposals, including for flood management activities and CalFire capital outlay projects. Some of these activities may have merit and represent priorities for the Legislature—particularly as flood vulnerabilities have been highlighted by recent storms. However, in the context of a budget problem when revenues already are insufficient to fund existing commitments, every dollar of new spending comes at the expense of a previously identified priority and requires finding a commensurate level of solution somewhere within the budget. Moreover, some of the proposals—most notably the CalFire projects—have significant out‑year costs, which would contribute to projected future budget deficits and require finding additional solutions in the coming years. We therefore think the Legislature should weigh the importance and value of the proposed new activities against the activities to which it has already committed, as this is essentially the spending trade‑off that will result as long as budget problems persist.

Additional Solutions May Be Needed if Budget Problem Worsens. As discussed earlier, recent economic data and our fiscal outlook suggest that the Governor’s revenue estimates have a high likelihood of being overly optimistic. Should that prove to be the case, the Legislature will need to identify additional solutions in order to meet its constitutional requirement to pass a balanced budget. While it has several options for crafting such solutions—including from within other policy areas and using tools other than spending reductions—given the magnitude of the recent one‑time investments in climate, resources, and environmental programs, the Legislature likely will want to consider making additional General Fund reductions in this area.

Outcomes and Success of Recent Augmentations Largely Are Still Unknown. While the administration has collected some data regarding the status of spending from recent augmentations, information about the outcomes from that spending largely is still unavailable. For example, the Legislature has funded numerous efforts to help protect and rescue fish and wildlife from drought impacts, but does not have information regarding which specific strategies have proven to be most successful for long‑term species protection. Similarly, the 2022‑23 budget package provided close to $3 billion in the current year for several different efforts to improve the state’s electrical grid reliability during summers and extreme events, but the degree to which these have increased the state’s preparedness still is not clear. Such data shortcomings are somewhat understandable, given how early many of these programs are in their implementation and expenditure of recently appropriated funds. However, the lack of such information makes it difficult for the Legislature to evaluate which programs are most effective at achieving their intended outcomes, and—perhaps most importantly—which are meaningfully contributing to the state’s overall climate resilience goals. Detailed program outcome data would be valuable in the near term to help inform the Legislature as to which lesser‑performing programs could be better candidates for making needed budget reductions. Moreover, such information also would be important for helping to guide longer‑term decisions, such as which programs should be prioritized for future funding investments. In addition to information on outcomes, the Legislature also could benefit from continued reporting from the administration regarding program implementation, including how funds are being prioritized for allocation and whether departments are encountering any barriers in effectively carrying out the Legislature’s goals. This type of data could facilitate the Legislature’s ability to be aware of and intervene if problems—such as significant delays—arise, or if departments are not implementing programs as the Legislature had originally intended.

Overarching Recommendations

Below, we discuss our overarching recommendations to the Legislature for crafting climate, resources, and environmental budget solutions, which we also summarize in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Summary of Overarching Recommendations for Crafting Climate, Resources,

and Environmental Budget Solutions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adopt Package of Budget Solutions Based on Legislative Prioritization Criteria. We recommend the Legislature develop its own package of budget solutions based on its priorities and guiding principles. Figure 4 highlights some of the criteria we suggest the Legislature use to guide its decisions. We provide our analyses and suggestions on specific programs in the subsequent sections of this report based on these principles. We find that many of the Governor’s proposals largely align with our suggested criteria, but so too would numerous alternative decisions the Legislature could make instead of or in addition to the Governor’s proposals. As the Legislature modifies program funding levels, we recommend that it also consider whether it wants to refine or refocus some program features to ensure that remaining funding targets the most important populations, activities, and desired outcomes.

Figure 4

Suggested Criteria for Crafting Climate, Resources, and

Environmental Budget Solutions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Be Selective When Opting to Delay—Rather Than Maintain or Reduce—Funding. As noted, the Governor proposed delaying about $800 million in funding for climate, resources, and environmental programs. While this approach might preserve funding over the longer term, it also exacerbates future budget problems. Given the out‑year budget forecast, we recommend the Legislature set a relatively high bar for opting to delay—rather than reduce—program funding. To the degree the Legislature wants to consider funding delays, we recommend limiting this strategy to programs that have a very compelling rationale for the state to prioritize maintaining funding (such as activities benefiting vulnerable populations), but for which (1) funding will not be spent this year, such as because of capacity issues precluding more immediate spending at the state or local level, and/or (2) more information is needed before specific decisions can be made about how to most effectively target the funds.

Reject Governor’s General Fund Trigger Restoration Approach, Maintain Legislative Flexibility. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s trigger restoration proposal for two reasons. First, given revenue forecasts and the “all or nothing” structure of the proposal, we believe the likelihood of the state receiving sufficient funds to activate the trigger is low, so portraying the trigger cuts as distinct from other proposed reductions is misleading. Second, the proposal minimizes legislative authority and flexibility to respond to changing revenue conditions and evolving spending priorities. We therefore recommend the Legislature instead focus its efforts on adopting the level of solutions needed to balance the 2023‑24 budget. Then, as revenues become clearer over the coming year, it can make midyear changes—including augmentations if possible, or additional reductions if needed—through its existing authorities, such as by passing midyear spending bills. If the Legislature finds it is important to identify some signals to help guide potential future actions, it could include intent language in the budget package to identify which program reductions it views as the highest priorities for potential midyear legislative restorations if that option becomes available. However, because priorities might change over the coming year—along with the evolving fiscal situation—we recommend the Legislature avoid locking in any decisions now and preserve its flexibility to revisit any future budget actions.

Reject or Modify Governor’s GGRF Trigger Approach, Maintain Legislative Flexibility. We similarly recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed approach of giving the Director of DOF the discretion over how to allocate potential increases in GGRF revenues. We recommend the Legislature either (1) follow its historical approach of waiting to allocate any unforeseen increases in 2023‑24 GGRF revenues as part of the 2024‑25 budget process; (2) appropriate such revenues by passing a midyear spending bill in early 2024; or (3) adopt language that directs the administration specifically how it should allocate additional GGRF revenues, such as to which particular programs—ZEV or otherwise—and at which levels. Any of these approaches would better preserve the Legislature’s spending decision authority as compared to the Governor’s proposal.

Use Spring Budget Process to Identify Additional Potential Budget Solutions for Climate, Resources, and Environmental Programs. Given the distinct possibility of worsening fiscal conditions, we recommend the Legislature begin to prepare now for the likely need to solve for a deeper revenue shortfall when it adopts its final budget this summer. Specifically, in addition to weighing the Governor’s proposed solutions and substituting its own alternatives, we recommend it identify additional reductions and fund shifts (and potentially some delays) for a greater total amount of solutions from climate, resources, and environmental programs than those proposed by the Governor. While this process will be challenging—and, likely, unpleasant—taking the time to consider, research, and select potential options over the spring will better prepare the Legislature to make decisions in May and June when it will not have much time to gather information or carefully consider program trade‑offs before the budget deadline.

Weigh Relative Priority of New Spending Against Existing Commitments. In the context of a budget shortfall, each additional dollar of General Fund spending for new activities necessitates making additional spending reductions from previously agreed‑upon commitments. As such, we recommend the Legislature keep these trade‑offs in mind as it considers the Governor’s new spending proposals. Essentially, we recommend the Legislature weigh whether the new proposals represent higher priorities than its previously budgeted activities, since funding one comes at the expense of another. As it undertakes these calculations, we recommend the Legislature also consider potential out‑year and/or ongoing costs associated with the new spending proposals and how they may affect future budget problems and resulting trade‑offs.

Request Additional Information From Administration on Availability of Federal Funding. We recommend the Legislature ask the administration to provide more detailed information on funding that the state and local entities could potentially access from IIJA and the Inflation Reduction Act. Departments likely have been closely tracking the federal programs that align with their missions, and therefore could help provide comprehensive summaries that might be more difficult and time‑intensive for legislative staff to track down on their own. Moreover, because federal agencies are still formulating some program specifics, additional details may become available over the spring. Such information could help instruct the Legislature’s decisions about where federal funds might help make up for potential state funding reductions, and to understand associated implications and trade‑offs in cases where federal programs’ criteria differ from the state’s programs. The Legislature could request that the administration provide this information ahead of the May Revision. Relatedly, we recommend the Legislature exercise caution about reducing state funding that might be essential for drawing down additional federal funds, such as monies that might be needed for state matching fund requirements.

Conduct Robust Oversight of Spending and Outcomes, and Consider Whether Additional Program Evaluations Might Be Worthwhile. We recommend the Legislature conduct both near‑term and ongoing oversight of how the administration is implementing—and local grantees are utilizing—funding from the recent budget augmentations. In particular, we recommend the Legislature track: (1) how the administration is prioritizing funding, especially within newly designed programs; (2) the time lines for making funding allocations and completing projects; (3) the levels of demand and over‑ or under‑subscription for specific programs; (4) any barriers to implementation that departments or grantees encounter; and (5) the impacts and outcomes of funded projects. The Legislature has a number of different options for conducting such oversight, all of which could be helpful to employ given that they would provide differing levels of detail. These include requesting that the administration report at spring budget hearings, requesting reports through supplemental reporting language, and adopting statutory reporting requirements (such as those typically included for general obligation bonds). Additionally, to the degree it might want more intensive external program evaluations for certain high‑priority programs to help assess their effectiveness, the Legislature could consider adopting language that directs the administration to set aside a portion of provided funding to contract for researchers to conduct more in‑depth studies.

Discussion of Specific Proposals

Zero‑Emission Vehicles

Recent and Planned Funding Augmentations

2021‑22 and 2022‑23 Budget Acts Included $9.9 Billion in Planned Investments for ZEV Programs. The previous two budgets committed significant funding for programs intended to promote purchase and use of ZEVs. As shown in Figure 5, this funding is spread across five years, including $6.5 billion already provided and $2.1 billion intended for 2023‑24. The majority of this funding is from the General Fund ($6.3 billion), but also includes $1.6 billion from Proposition 98 General Fund (for school buses), $1.3 billion from GGRF, $307 million from federal funds, and $366 million from other special funds. Most of the funding is for continuing or expanding existing programs, such as rebates for purchasing vehicles and incentive payments for developing charging infrastructure. As shown in the figure, ZEV funding is primarily split between the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the California Energy Commission (CEC). CARB oversees vehicle incentive programs, while CEC oversees ZEV charging infrastructure programs. The majority of planned ZEV augmentations ($5.5 billion) support heavy‑duty vehicle programs.

Figure 5

Recent and Planned Zero‑Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Augmentations

Highlighted Rows Indicate Programs Governor Proposes for Budget Solutions

General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Totals |

|

Light‑Duty Programs |

$1,210 |

$396 |

$495 |

$170 |

$80 |

$2,351 |

|

|

ZEV Fueling Infrastructure Grants |

CEC |

$515 |

$15 |

$210 |

$90 |

$40 |

$870 |

|

Clean Vehicle Rebate Project |

CARB |

525a |

— |

— |

— |

— |

525 |

|

Clean Cars 4 All and Other Equity Projects |

CARB |

150b |

381a |

125 |

— |

— |

656 |

|

Equitable At‑Home Charging |

CEC |

20 |

— |

160 |

80 |

40 |

300 |

|

Heavy‑Duty Programs |

$1,627 |

$2,635 |

$1,205 |

$488 |

$225 |

$6,180 |

|

|

School Buses and Infrastructure |

CARB |

$130 |

$1,260c |

$135 |

— |

— |

$1,525 |

|

CEC |

20 |

390c |

15 |

— |

— |

425 |

|

|

Clean Trucks, Buses, and Off‑Road Equipment |

CARB |

500a |

600a |

— |

— |

— |

1,100 |

|

CEC |

299 |

— |

315 |

$31 |

$25 |

670 |

|

|

Transit Buses and Infrastructure |

CARB |

70 |

70 |

200 |

110 |

70 |

520 |

|

CEC |

30 |

30 |

90 |

50 |

30 |

230 |

|

|

Drayage Trucks and Infrastructure |

CARB |

157 |

75 |

165 |

48 |

— |

445 |

|

CEC |

181 |

85 |

185 |

49 |

— |

500 |

|

|

Ports |

CARB |

— |

— |

60 |

120 |

70 |

250 |

|

CEC |

— |

— |

40 |

80 |

30 |

150 |

|

|

ZEV Manufacturing Grants |

CEC |

125 |

125 |

— |

— |

— |

250 |

|

Near‑Zero Heavy‑Duty Trucks |

CARB |

45 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

45 |

|

Drayage Trucks and Infrastructure Pilot Project |

CARB |

40 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

40 |

|

CEC |

25 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

25 |

|

|

ZEV Consumer Awareness |

GO‑BIZ |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

5 |

|

Other |

$514 |

$137 |

$407 |

$200 |

$155 |

$1,413 |

|

|

Transportation package ZEV |

CalSTA |

$407b |

$77d |

$77d |

$77d |

$76 |

$714 |

|

Sustainable community plans and strategies |

CARB/CalSTA |

— |

— |

200 |

80 |

59 |

339 |

|

Emerging Opportunities |

CARB |

53 |

— |

35 |

12 |

— |

100 |

|

CEC |

54 |

— |

35 |

11 |

— |

100 |

|

|

Charter boats compliance |

CARB |

— |

60a |

40 |

— |

— |

100 |

|

Hydrogen Infrastructure |

CEC |

— |

— |

20 |

20 |

20 |

60 |

|

Totals |

$3,351 |

$3,168 |

$2,107 |

$858 |

$460 |

$9,944 |

|

|

aIncludes Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. bIncludes $200 million Public Transportation Account and $80 million federal funds. cProposition 98 General Fund. dFederal funds. |

|||||||

|

CEC = California Energy Commission; CARB = California Air Resources Board; Go‑BIZ = Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development; and CalSTA = California State Transportation Agency. |

|||||||

Package Represents Unusually Large State‑Level Investment in ZEV Programs. The large investments reflect the state’s policy goals of reducing GHGs from transportation. Transportation is the single largest source of GHGs—responsible for 40 percent of emissions—making the sector a critical area for seeking reductions. In the fall of 2022, CARB adopted regulations to require all new cars sold in California to be ZEV or hybrid‑electric by 2035. While the state has historically administered a variety of programs intended to promote ZEVs, the funding displayed in Figure 5 is significant compared to previous amounts, as is the use of General Fund. For example, in 2019‑20, the state invested a total of $435 million for ZEV programs, from GGRF. Certain vehicle fees commonly known as “AB 8” fees have provided another consistent source of funding for ZEV and mobile source emission reduction programs. These fees provide about $170 million annually for programs that support ZEVs and lower‑emission vehicles. (As we discuss in a separate publication, a portion of these fees are scheduled to sunset in 2023, and the Governor is proposing that the Legislature renew them to continue to support existing programs.)

Governor’s Proposal

Reduces General Fund Spending and Partially Backfills With GGRF for Net Reduction of $1.1 Billion. As shown in Figure 6, the administration proposes to reduce General Fund spending on ZEV programs by a total of $2.5 billion, including $1.5 billion in 2023‑24. However, the Governor proposes using $1.4 billion from discretionary GGRF revenues across three years to backfill some of these reductions. As shown in Figure 7, this amount includes $611 million in 2023‑24. The Governor also proposes pledging $414 million in annual discretionary GGRF revenues in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 to partially backfill proposed reductions in those years. Largely because of this proposed use of GGRF, the majority of ZEV programs would be unaffected by the Governor’s proposed reductions, including Clean Cars 4 All (CC4A, which provides rebates to lower‑income individuals for purchasing ZEVs), and a program shared by CARB and CEC to support ZEV and lower‑emission drayage trucks and infrastructure. For most of the programs that would receive reductions, the Governor would maintain at least 50 percent of funding. The one exception is the proposed elimination of a new program shared by CARB and CEC aimed at reducing mobile source emissions from port equipment. Overall, the Governor proposes maintaining $8.9 billion, or 89 percent, of intended funding for ZEV programs across the five years.

Figure 6

Governor’s Proposed Zero‑Emission Vehicle (ZEV) Budget Solutions

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Total Augmentations |

General Fund Reductions |

GGRF Backfill (2023‑24 Through 2025‑26) |

Net Reductions |

New Proposed Amounts |

|

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 and 2025‑26 |

|||||

|

Programs Proposed for Solutions |

||||||

|

School Buses and Infrastructure (CARB) |

$1,525 |

‑$135 |

— |

— |

‑$135 |

$1,390 |

|

School Buses and Infrastructure (CEC) |

425 |

‑15 |

— |

— |

‑15 |

410 |

|

ZEV Fueling Infrastructure Grants |

870 |

‑210 |

‑$130 |

$130 |

‑210 |

660 |

|

Clean Cars 4 All and Other Equity Projects |

656 |

‑125 |

— |

125 |

— |

656 |

|

Transit Buses and Infrastructure (CARB) |

520 |

‑176 |

‑180 |

293 |

‑63 |

457 |

|

Transit Buses and Infrastructure (CEC) |

230 |

‑66 |

‑80 |

130 |

‑16 |

214 |

|

Drayage Trucks and Infrastructure (CARB) |

445 |

‑80 |

‑48 |

128 |

— |

445 |

|

Drayage Trucks and Infrastructure (CEC) |

500 |

‑85 |

‑49 |

134 |

— |

500 |

|

Sustainable community plans and strategies |

339 |

‑140 |

‑44 |

25 |

‑159 |

180 |

|

Equitable At‑Home Charging |

300 |

‑160 |

‑120 |

280 |

— |

300 |

|

Clean Trucks, Buses, and Off‑Road Equipment |

299 |

‑98 |

‑56 |

154 |

— |

299 |

|

Ports (CARB) |

250 |

‑60 |

‑190 |

— |

‑250 |

— |

|

Ports (CEC) |

150 |

‑40 |

‑110 |

— |

‑150 |

— |

|

Charter boats compliance |

100 |

‑40 |

— |

40 |

— |

100 |

|

Emerging Opportunities (CARB) |

100 |

‑35 |

‑12 |

— |

‑47 |

53 |

|

Emerging Opportunities (CEC) |

100 |

‑35 |

‑11 |

— |

‑46 |

54 |

|

Subtotals |

($6,809) |

(‑$1,500) |

(‑$1,030) |

($1,439) |

(‑$1,091) |

($5,718) |

|

All Other ZEV Package Funding |

$3,135 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

$3,135 |

|

Totals |

$9,944 |

‑$1,500 |

‑$1,030 |

$1,439 |

‑$1,091 |

$8,853 |

|

GGRF = Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; CARB = California Air Resources Board; and CEC = California Energy Commission. |

||||||

Figure 7

Governor’s Proposed Use of GGRF for ZEV Program Backfills

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Department |

Backfill General Fund With |

GGRF Three‑ |

||

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|||

|

Transit Buses and Infrastructure |

CARB |

$38 |

$56 |

$199 |

$293 |

|

CEC |

25 |

40 |

65 |

130 |

|

|

Equitable At‑Home Charging |

CEC |

160 |

80 |

40 |

280 |

|

Clean Trucks, Buses, and Off‑Road Equipment |

CEC |

98 |

31 |

25 |

154 |

|

Drayage Trucks and Infrastructure |

CARB |

80 |

48 |

— |

128 |

|

CEC |

85 |

49 |

— |

134 |

|

|

ZEV Fueling Infrastructure Grants |

CEC |

— |

90 |

40 |

130 |

|

Clean Cars 4 All and Other Equity Projects |

CARB |

125 |

— |

— |

125 |

|

Charter boats compliance |

CARB |

— |

20 |

20 |

40 |

|

Sustainable community plans and strategies |

CARB/CalSTA |

— |

— |

25 |

25 |

|

Totals |

$611 |

$414 |

$414 |

$1,439 |

|

|

GGRF = Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund; ZEV = zero‑emission vehicles; CARB = California Air Resources Board; CEC = California Energy Commission; and CalSTA = California State Transportation Agency. |

|||||

Proposes Trigger Restoration Approach for GGRF. The Governor proposes a trigger restoration approach for GGRF revenues that the state might receive above current estimates during the 2023‑24 fiscal year. Specifically, proposed budget control section language would require the administration to allocate additional GGRF revenues to backfill additional proposed reductions to ZEV programs. The language identifies specific activities for which these revenues could be used—fueling infrastructure grants, transit and school buses, ports, community‑based efforts, emerging opportunities, and charter boat compliance—but would allow the Director of DOF the discretion to determine which of these ZEV programs to augment and at what levels.

Administration Plans to Seek Federal Funds to Offset Other Reductions. The administration indicates plans to use potential federal funding from IIJA and the Inflation Reduction Act to help further offset the proposed decrease in state funds. For example, the administration has identified federal funding for activities that reduce GHG emissions at ports ($3 billion total available), support charging infrastructure ($2.5 billion total available), and support ZEV buses and bus infrastructure ($5.6 billion total available)—three areas proposed for General Fund reductions.

Proposes $35 Million New Spending for Charging Stations at State‑Owned Locations. Outside of the ZEV package—and therefore not displayed in any of the figures—the Department of General Services (DGS) Office of Sustainability is requesting $35 million from the General Fund over three years to install ZEV infrastructure at state‑owned and leased facilities.

Assessment

Consider Highest‑Priority Goals When Making Funding Decisions. The large number of ZEV‑related programs reflects diversity in approaches to achieve various state goals, such as reducing air pollution, lowering GHG emissions, and providing subsidies and infrastructure benefiting low‑income and disadvantaged communities. Prioritizing among these complementary goals and assessing how effective each program is at attaining them can help guide the Legislature’s decisions about where to make funding reductions. For example, if the Legislature’s highest‑priority goal is to reduce air pollution from mobile sources, then it may want to prioritize maintaining funding for programs that incentivize medium‑ and heavy‑duty ZEVs, as these are more effective at achieving that objective than programs that focus on passenger vehicles or charging infrastructure. Alternatively, if the most important goal is reducing GHGs, then maintaining funding for programs that promote passenger ZEVs make sense. (Please see our 2022 report, The 2022‑23 Budget: Zero‑Emission Vehicle Programs, for more information on the effectiveness of ZEV programs by goal.)

Governor’s Proposed Solutions Appear Generally Reasonable. We find merit in the Governor’s approach of focusing budget solutions on newer programs and in areas with potential federal funding availability. For example, eliminating funding for the ports program is less likely to cause disruption as compared to some existing programs, given that this program has not begun implementation. Furthermore, federal funds for similar activities at ports are available to help offset a loss in state funds. We also see value in the Governor’s approach of retaining funding for programs that reduce emissions and air pollution in low‑income/disadvantaged communities, including the drayage truck programs and CC4A. These communities are more likely to be located in heavy transit corridors with higher levels of air pollution, so they represent a worthwhile area of state focus and intervention. This is consistent with the Legislature’s historical prioritization of programs that provide ZEV funding for low‑income and disadvantaged communities. Finally, a rationale exists for making reductions in ZEV charging infrastructure support, as the market for charging is maturing and the same level of state intervention may no longer be needed to spur development. Additionally, new federal funding is becoming available for charging infrastructure.

Consider Refining Some Programs to Focus on Highest‑Priority Needs. As it considers making funding reductions, the Legislature may want to also consider narrowing the scope of certain ZEV programs. This could help to ensure that remaining funding is specifically targeted towards achieving the Legislature’s highest‑priority goals. For example, this might include more narrowly focusing benefits on lower‑income Californians who are not eligible for federal subsidies and efforts where state investments could be most effective at spurring growth in ZEV infrastructure. Two possible approaches include:

- Focusing CC4A Rebates on Consumers Who Do Not Qualify for Federal Incentives. The Governor proposes to maintain the full funding amount for the CC4A program ($656 million), which provides rebates for low‑income car buyers who purchase ZEVs. Some individuals who purchase ZEVs are also eligible for federal tax credits up to $7,500. For example, a car buyer at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty level and living in a disadvantaged community could receive up to $12,000 from CC4A, up to $7,500 from the state’s Clean Vehicle Rebate Program, and up to $7,500 of federal incentives. As the program is currently structured, some consumers can qualify for both CC4A and other state ZEV rebate programs in addition to the federal tax incentive. In contrast, some Californians are only eligible for CC4A because their incomes are too low to participate in the federal program. (The federal program provides incentives as a tax credit and very low‑income households are not required to file taxes so therefore are not able to take advantage of this benefit.) Particularly if it were to make reductions to the CC4A program, the Legislature could consider further limiting the program’s income‑eligibility threshold to focus exclusively on consumers who do not qualify for federal incentives. This would allow the Legislature to focus funding on those who do not have other options for subsidizing their ZEV purchases and facilitate more equitable outcomes.

- Focusing Light‑Duty ZEV Charging Funding on Chargers That Would Otherwise Not Be Developed. The state has invested heavily in chargers and these investments have helped support a private market for public charging stations. More chargers likely will be deployed with or without additional state investments due to increased availability of federal funding and the growth of companies that install chargers in public locations. This is particularly true for passenger light‑duty vehicles in locations with higher concentrations of ZEVs, which tend to be higher‑income areas. The Legislature may want to consider whether the state should focus less on funding light‑duty chargers and instead prioritize infrastructure investments in areas that do not have as much private investment. This could include helping to subsidize installment of chargers in multiunit dwellings and in lower‑income neighborhoods. This also could include prioritizing funding for medium‑ and heavy‑duty vehicles and hydrogen vehicles rather than light‑duty electric chargers. While these types of chargers and fueling stations may also qualify for federal funds, they are more emergent technologies and may need additional support before reaching the same availability as passenger electric vehicle chargers.

Legislature Will Need to Weigh Whether ZEV Programs Represent Its Highest Priority for GGRF Discretionary Funds… The Governor proposes to use the majority of discretionary GGRF funds for ZEV programs. Together with $250 million proposed for backfilling a reduction to the AB 617 air quality improvement program (discussed in the “Community Resilience” section of this report), this represents nearly all of the administration’s projected 2023‑24 discretionary GGRF expenditures. Typically, the Legislature and Governor negotiate annually to allocate discretionary GGRF revenue for a variety of programs and priorities. As such, directing these revenues towards only two program areas is unusual. The Governor’s proposal presents the Legislature with the key decision of whether sustaining ZEV programs is its highest priority for the 2023‑24 discretionary GGRF revenue. However, should the Legislature reject the Governor’s GGRF approach, this could mean deeper reductions to ZEV or other programs compared to what the administration proposes if it wants to realize the same amount of General Fund savings.

…And Whether It Wants to Commit Out‑Year GGRF Revenues Now. As shown in Figure 7, in addition to the $611 million of discretionary GGRF revenues in 2023‑24, the Governor proposes using $414 million annually in future GGRF discretionary funds to backfill ZEV programs in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. This is somewhat unusual—in general, after allocating funding for statutorily required expenditures, uses for remaining GGRF funds typically are determined by the Governor and Legislature on an annual basis as part of the deliberations on the budget for the fiscal year in which they would be spent. Committing future GGRF revenues now would reduce the discretionary funds available in future years that could support other programs and preclude the Legislature’s ability to weigh whether it might have different spending priorities in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26.

GGRF Trigger Proposal Also Raises Concerns. We have concerns about the Governor’s proposal to allow DOF to allocate potential midyear increases in GGRF revenues. Historically, the Legislature has opted to delay action on any additional discretionary GGRF revenues that materialize midyear and allocate them as part of the subsequent year’s budget package. This standard approach allows the Legislature the discretion to consider its highest priorities for that spending as part of a more comprehensive discussion. When midyear adjustments have been necessary due to GGRF revenues coming in lower than expected, the administration has cut programs proportionally (rather than making discretionary decisions to prioritize some over others). Allowing the administration to select which ZEV programs it would fund with any potential new monies and at what levels—without any statutory direction from the Legislature—shifts too much decision‑making authority away from the Legislature to the administration.

Potential for Higher GGRF Revenues Highlights Importance of Identifying Legislative Spending Priorities. We believe a strong possibility exists that additional GGRF revenues will be available to spend in 2023‑24, as the administration historically underestimates cap‑and‑trade auction revenues. This makes it particularly important for the Legislature to consider its priorities for these discretionary funds—and to maintain decision‑making over how to spend potential midyear increases. Extra GGRF revenues could be especially helpful this year, given the potential for a worsening budget picture. The Legislature could consider using such funds to support other climate‑related activities that might otherwise need to be reduced.