LAO Contact

May 23, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Multiyear Budget Outlook

Key Takeaways

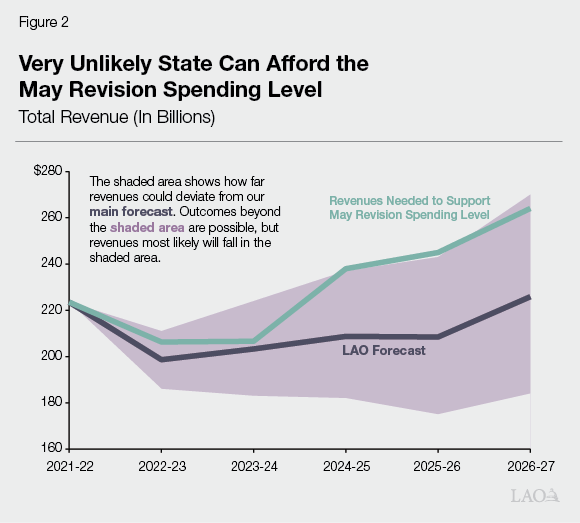

Very Unlikely the State Will Be Able to Afford the May Revision Spending Levels. Under our estimates, the state faces operating deficits throughout the multiyear window, meaning revenues would need to come in above our projections for the budget to be balanced. While the revenues required to balance the budget are optimistic, but plausible, in the budget window, they are improbable in the out‑years. For example, to eliminate the operating deficit in 2024‑25, revenues would need to be roughly $30 billion higher than our forecast. Our analysis suggests that level of revenue is very unlikely—there is less than a one‑in‑six chance the state can afford the May Revision spending level across the five‑year period. This means that, if the Legislature adopts the Governor’s May Revision proposals, the state very likely will face more budget problems over the next few years.

Multiyear One‑Time and Temporary Spending Commitments No Longer Affordable. In 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, the Legislature committed to future one‑time and temporary spending in 2023‑24 and beyond. Most of this spending no longer appears to be affordable. While the May Revision makes several billion dollars in spending reductions, it maintains $11 billion in one‑time and temporary spending in 2023‑24. We recommend this spending be reduced further (from $11 billion to roughly $4 billion) and out‑year one‑time and temporary spending be eliminated entirely, as explained further below.

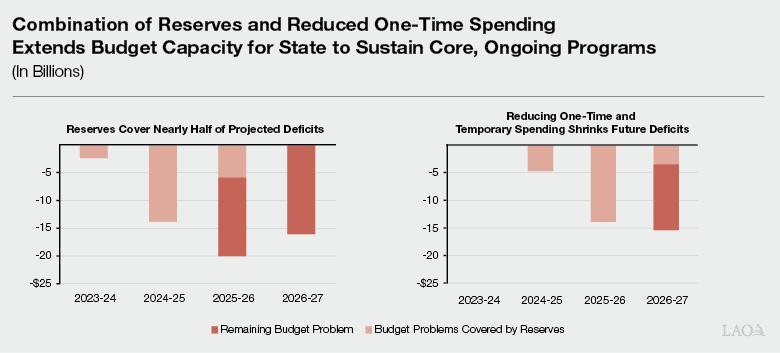

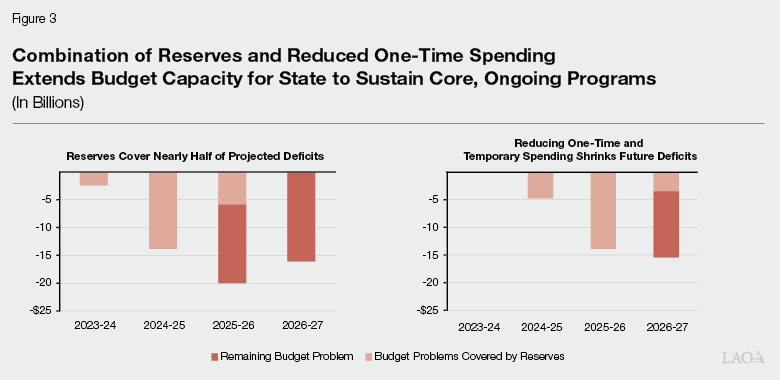

Combination of Reserves and Reduced One‑Time Spending Extends Budget Capacity for State to Sustain Core, Ongoing Programs. Under our outlook, reserves would cover nearly half of the projected multiyear deficits while reducing $18 billion of one‑time and temporary spending would cover an additional third. The remainder—$12 billion, shown on the far right of the figure—would need to be addressed with other solutions, like revenue increases, cost shifts, and other spending reductions. Taken together, reducing spending and using reserves give the Legislature a few years to align revenues and spending as the economic picture unfolds.

Introduction

This brief presents our office’s independent assessment of the condition of the state General Fund budget through 2026‑27 under our forecast of revenues and spending, assuming the Governor’s May Revision policies were adopted. The first section of the brief presents our analysis of the budget condition under these assumptions. The second section provides our comments.

Analysis

Budget Problem $6 Billion Larger in 2023‑24 Under LAO Estimates. Under our office’s projections, and assuming the Governor’s May Revision policies were adopted, the budget problem for this year is $34.5 billion—$6.2 billion higher than our estimate under the administration’s projections. There are two key, partially offsetting, reasons for this roughly $6 billion difference:

- Lower Revenues. Across the budget window (2021‑22 through 2023‑24), our revenue projections are $11 billion lower than the administration’s estimates. We discuss our economic and revenue outlook in greater detail here: The 2023‑24 Budget: May Revenue Outlook. Lower revenues result in a larger budget problem.

- Lower Constitutional Requirements. Coupled with our lower revenue estimates, we also estimate that spending on constitutional requirements is correspondingly lower by $4.8 billion. (Lower spending partially offsets the increase in the budget problem.) These requirements are based on formulas that tend to increase spending when revenues grow and reduce spending when revenues decline. These formulas include spending on schools and community colleges (under Proposition 98 [1988]), as well as debt payments and reserve deposits (under the rules of Proposition 2 [2014]).

If the Legislature adopts the administration’s revenue estimates—and does not solve the additional budget problem we identify above—we anticipate there will be a revenue shortfall in 2023‑24. As a result, the Legislature would need to address this additional budget problem as part of the 2024‑25 budget process. (This would add to the double‑digit budget problem for 2024‑25 already projected under both our and the administration’s estimates, as we describe below.)

LAO Spending Estimates Over $10 Billion Higher Than the Administration by 2026‑27. By 2026‑27, our estimate of General Fund spending (excluding spending on schools and community colleges) is $10 billion higher than the administration’s estimate. At an agency level, the single largest contributor to this difference is Health and Human Services (HHS). Across all programs in this agency (including, for example, Medi‑Cal, In‑Home Supportive Services, developmental services, and child care), our estimates are $6 billion higher than the administration’s projection by 2026‑27. Between 2023‑24 and 2026‑27, HHS programs grow at an average annual rate of 5.5 percent under our projections, compared to 3.4 percent under the administration’s estimates. Remaining programs—including employee compensation, pensions, and higher education—are responsible for the remaining $4 billion in difference in that year. As we have commented in the past, our office has little insight into the components of, or assumptions underlying, the administration’s projections in HHS. As a result, we cannot identify the precise source of these differences—or the comparative reliability of our respective estimates—with confidence.

General Fund Spending on Schools and Community Colleges Grows Moderately Under LAO Revenues. Under our outlook, Proposition 98 General Fund spending on schools and community colleges is $89 billion in 2026‑27—nearly $12 billion above our projected 2023‑24 level and $5 billion higher than the administration’s projection for 2026‑27. Both of these figures are attributable to growth in revenue and the Proposition 98 formula that reserves a minimum percentage of that revenue (just under 40 percent) for school and community college programs. A small portion of the increase relative to 2023‑24 (about $1.5 billion) reflects the continuing expansion of transitional kindergarten in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. (The June 2021 budget plan contained an agreement to make all four‑year olds eligible for transitional kindergarten by 2025‑26 and required the state to adjust the Proposition 98 requirement upward for the associated costs.) When combined with slightly smaller increases in the local property tax portion of Proposition 98, overall growth in school and community college funding would average around 4.6 percent annually.

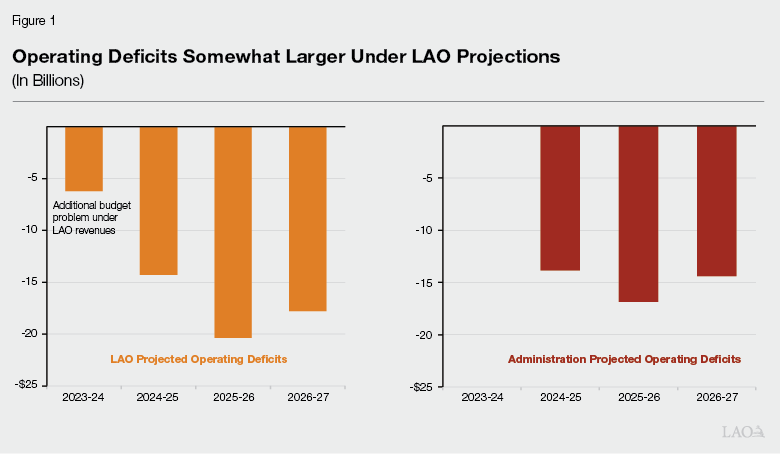

Operating Deficits Average $18 Billion Annually Under LAO Estimates. Figure 1 shows our office’s projections of the state’s budget condition compared to the administration’s estimates. As the figure shows, both of our offices project the state will have operating deficits (budget problems) over the multiyear period. The operating deficits under our forecast are slightly larger—ranging from $14 billion to $20 billion—compared to those under the administration’s forecast—ranging from $14 billion to $17 billion. There are three reasons for these differences (some offsetting): (1) our revenue estimates are somewhat higher than the administration in the out‑years, particularly in 2026‑27; (2) our higher revenue estimates result in higher spending on schools and community colleges; and (3) as noted above, our estimate of spending on all other programs is higher than the administration’s projections over the period, reaching a difference of $10 billion by 2026‑27.

Very Unlikely the State Will Be Able to Afford the May Revision Spending Levels. While both our and the administration’s forecasts suggest the state faces operating deficits, revenues could differ substantially from these estimates. Figure 2 displays the distribution of the most likely revenue outcomes over the multiyear (in light purple). As seen in the figure, while the revenues required to balance the budget (in green) are optimistic, but plausible, in the budget window, they are improbable in the out‑years. For example, to eliminate the operating deficit in 2024‑25, revenues would need to be roughly $30 billion higher than our forecast (in dark purple). Our analysis suggests that level of revenue is very unlikely—there is less than a one‑in‑six chance the state can afford the May Revision spending level across the five‑year period. This means that, if the Legislature adopts the Governor’s May Revision proposals, the state very likely will face more budget problems over the next few years.

Comments

Multiyear One‑Time and Temporary Spending Commitments No Longer Affordable. In budget‑related legislation, the Legislature often commits to future spending augmentations. In 2022‑23, for example, the Legislature committed tens of billions of dollars to one‑time and temporary spending in 2023‑24 and later. Establishing future spending commitments allows the Legislature to exert its priorities in future budgets in advance of new proposals from the Governor. However, these commitments should be understood to be subject to change due to the uncertainty surrounding revenue projections. Most of this spending no longer appears to be affordable. Under our revenues, we recommend one‑time spending in 2023‑24 be reduced further (from $11 billion to roughly $4 billion) and out‑year one‑time and temporary spending be eliminated entirely, as explained further below.

Proposed Spending Delays Are Likely Unaffordable. This year, the Governor proposes delaying some spending planned for 2023‑24 to future years. We find it is very unlikely that future budgets will have the capacity to accommodate all of the out‑year spending planned under the Governor’s May Revision, including the proposed spending delays. As a result, we recommend the Legislature ensure high‑priority, one‑time spending is included in this year’s budget because future one‑time spending is unlikely to be affordable.

Reserves Cover Nearly Half of Projected Cumulative Budget Problems Over the Multiyear. Under our estimates, the state would have $22 billion in general purpose reserves that it could use to cover the deficits shown in Figure 1. (This would include $21.7 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account and $450 million in the Safety Net Reserve.) Cumulatively, deficits would be $52 billion over the period, meaning the state could cover nearly half of the projected deficits using reserves alone, as shown on the left side of Figure 3. As reserves are not sufficient cover the full projected budget problems under our forecast, the Legislature would need to use other options (for example, spending reductions, revenue increases, or cost shifts) to address the remaining $30 billion in deficits. Reducing one‑time and temporary spending would address an additional $18 billion. The remainder—$12 billion, shown on the far right in Figure 3—would need to be addressed with other solutions.

Combination of Reserves and Reduced One‑Time Spending Extends Budget Capacity for State to Sustain Core, Ongoing Programs. Taken together, reducing spending and using reserves give the Legislature a few years to align revenues and spending as the economic picture unfolds. Using only one or the other would mean the Legislature would need to make more difficult decisions—like cuts to core programs or revenue increases—at least one year earlier. Although revenue estimates are subject to uncertainty, revenues are very unlikely to grow sufficiently to cover planned spending. Consequently, we advise the Legislature to begin to address future budget problems by reducing additional one‑time spending as part of this year’s budget process.