LAO Contact

February 28, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

University of California

Summary

Brief Covers the University of California (UC) Budget. This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals relating to UC’s core operations and enrollment. It also revisits recent one‑time initiatives and capital projects the state has funded at UC.

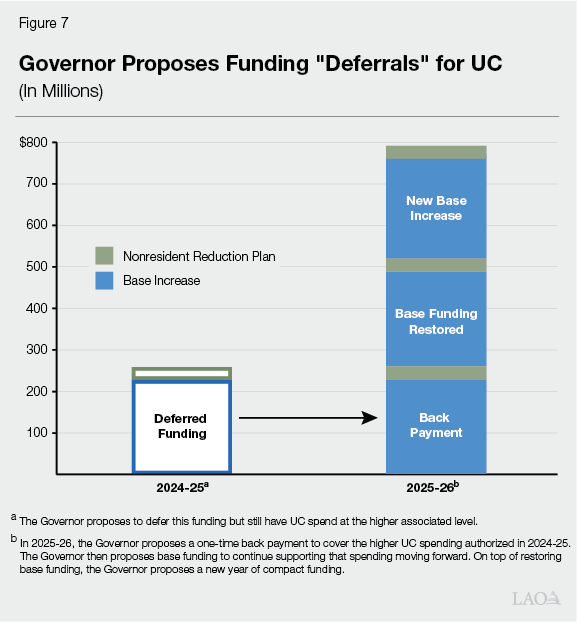

Governor Proposes Two Funding Deferrals for UC. Specifically, the Governor proposes deferring a $228 million base increase and a $31 million augmentation relating to a nonresident enrollment reduction plan. Under the Governor’s proposed approach, the state would delay these funding increases until 2025‑26, at which time it would double up ongoing increases as well as provide one‑time back payments. In the meantime, UC would increase spending in 2024‑25 by the originally planned amounts, likely by borrowing internally.

Recommend Holding State Funding and Spending Expectations Flat for UC. We recommend rejecting the proposed deferrals. The Governor’s approach creates risk for the state, which would be committing to a $790 million General Fund increase for UC in 2025‑26, despite facing a significant projected budget deficit that year. The approach also creates risk for UC, which would be increasing spending and incurring costs associated with internally borrowing in anticipation of a state funding increase in 2025‑26. If the state is unable to provide these funds, then UC likely would need to consider significant spending reductions that could be more disruptive than containing spending in the first place.

Recommend Also Holding UC’s Funded Enrollment Target Flat. In 2023‑24, UC estimates it is enrolling 202,278 resident full‑time equivalent (FTE) students—an increase of 5,167 students over the previous year. Even with this growth, UC remains 1,383 FTE students below its funded enrollment target. The Governor’s compact intends for UC to grow resident undergraduate enrollment by 1 percent annually. The Governor’s budget maintains this expectation. Given that UC could add more students within its current funded enrollment target, some UC campuses have missed their recent enrollment targets, additional enrollment capacity exists at the California State University, and the state is facing deficits, we recommend instead holding UC’s enrollment target flat for 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. As an option, the Legislature could consider having UC use its reserves on a temporary basis to enroll additional resident students at its three highest‑demand campuses.

Recommend Pulling Back Some Unspent One‑Time Funds From Prior Budgets. From 2021‑22 to 2023‑24, the state appropriated $1.3 billion one‑time General Fund for about 40 UC initiatives. Many of these initiatives were campus specific and involved research activities. Of the $1.3 billion, we estimate $325 million remains unspent. Given the state’s projected operating deficits, we recommend the Legislature pull back all of these remaining one‑time funds.

Recommend a Few Changes Related to Debt‑Financed Capital Projects. In 2023‑24, the state appropriated $84 million ongoing General Fund for a total of 11 capital projects that UC was to debt finance using university bonds. Three of these projects remain in the preliminary planning phase and UC has not yet sold bonds to finance them. We recommend the Legislature pause these three projects and remove an associated $22 million ongoing General Fund from UC’s budget. We also recommend not moving forward at this time with the UC Merced medical education building and removing the associated $14.5 million in annual debt service funding. Though UC has entered a construction contract for this project, it has not yet sold bonds for it. We also recommend the state align the rest of its debt service funding with UC’s actual debt service costs. Doing so likely would yield at least $50 million in savings in 2023‑24, followed by smaller amounts of savings over the next few years as UC sells additional bonds.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on UC. UC is one of California’s three public higher education segments. Under state law, UC is to provide undergraduate and graduate education, including doctoral programs and professional programs in law and medicine. It also is to serve as the primary state‑supported academic agency for research. The UC system consists of ten campuses. Nine of UC’s campuses enroll students across a range of disciplines, whereas one campus enrolls graduate health science students only. This brief analyzes the Governor’s 2024‑25 budget proposals for UC. The first section of the brief provides an overview of those proposals. The next two sections focus on core operations and enrollment, respectively. The last section provides a recap of recent UC initiatives that could be revisited given the state’s projected budget deficits.

Overview

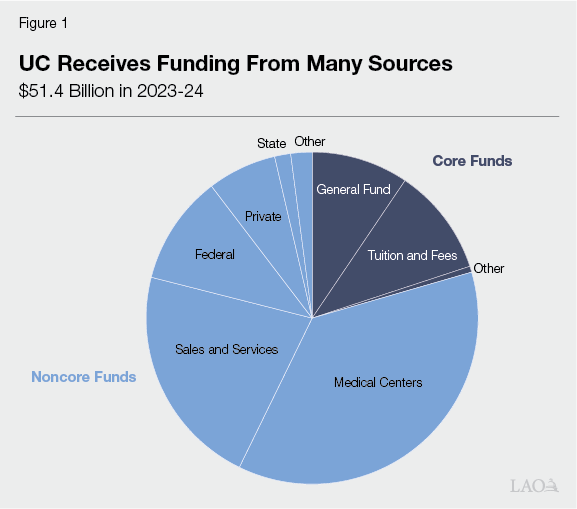

UC Budget Currently Is $51.4 Billion. Of the three public higher education segments, UC has the largest budget, with total funding greater than the California State University (CSU) and California Community Colleges (CCC) combined. As Figure 1 shows, UC receives funding from a diverse array of sources. The state generally focuses its budget decisions around UC’s “core funds,” or the portion of UC’s budget supporting undergraduate and graduate education and certain state‑supported research and outreach programs. Core funds at UC primarily consist of state General Fund and student tuition revenue. A small portion comes from lottery funds, a share of patent royalty income, and overhead funds associated with federal and state research grants. Between 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, ongoing core funds per student increased 4 percent at UC.

Ongoing Core Funding Increases by $230 Million (2.2 Percent) Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor proposes to increase state General Fund for UC by only $17 million (0.4 percent), but tuition and fee revenue is expected to increase by $213 million (4 percent). Other core funds increase slightly (by a combined $62,000). The increase in tuition and fee revenue is a result of higher tuition charges as well as anticipated enrollment growth. Under the Governor’s budget, ongoing core funding per student increases 0.7 percent.

Figure 2

Largest Portion of UC Core Fund Increase Comes From Tuition

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2022‑23 Actual |

2023‑24 Revised |

2024‑25 Proposed |

Change From 2023‑24 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Ongoing Core Funds |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,377 |

$4,712 |

$4,729 |

$17 |

0.4% |

|

Tuition and feesa |

5,174 |

5,390 |

5,603 |

213 |

4.0 |

|

Lottery |

72 |

58 |

58 |

— |

‑0.1b |

|

Other core fundsc |

243 |

242 |

242 |

— |

—b |

|

Totals |

$9,866 |

$10,402 |

$10,632 |

$230 |

2.2% |

|

FTE Students |

289,695 |

292,457 |

296,937 |

4,480 |

1.5% |

|

Funding Per Student |

$34,056 |

$35,569 |

$35,807 |

$238 |

0.7 |

|

aIncludes funds used for student financial aid. bLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. cIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Governor’s Budget Includes a Few Funding Adjustments for UC. As Figure 3 shows, the Governor’s budget includes two ongoing General Fund adjustments for UC. The largest is to pay debt service for a new medical education facility at UC Merced. The box below provides more information about this project. We also discuss this project in the “Budget Solutions” section of this brief. The other ongoing adjustment is an additional $2.6 million General Fund backfill for a graduate medical education (GME) program. As Proposition 56 tobacco‑tax revenue supporting this program declines, the state has used General Fund to backfill for the loss, maintaining the program at $40 million annually. In 2024‑25, a total of $13 million in ongoing General Fund would be provided to the program. (In 2024, UC also expects to begin receiving annual installments of $75 million for expanding GME in connection with the recently enacted managed care organization tax agreement.) The largest one‑time funding adjustments in the Governor’s budget involve carryover—$5 million for employee professional development programs and $4.5 million for the UC Hematologic Malignancies Pilot.

Figure 3

Governor’s Budget Includes a Few Funding

Adjustments for UC

Reflects Governor’s Budget Proposals, 2024‑25 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

Debt service for new UC Merced medical education facility |

$14.5 |

|

Graduate medical education backfilla |

2.6 |

|

Subtotal |

($17.1) |

|

One‑Time Adjustments |

|

|

Carryover |

$9.5 |

|

Nutrition Policy Instituteb |

1.1 |

|

Subtotal |

($10.6) |

|

Total |

$27.7 |

|

aReflects a General Fund backfill for a drop in Proposition 56 tobacco‑tax revenue. The backfill maintains the program at $40 million. bUnder a multiyear budget agreement, this institute received $1.3 million in 2023‑24, rising to $2.4 million in 2024‑25. |

|

State Approved a New UC Merced Medical Education Building

New Facility Is Costliest State‑Funded UC Project to Date. Chapter 23 of 2019 (AB 74, Ting) gave the University of California (UC) authority to construct a medical education facility on or near the Merced campus. The accompanying provisional language indicated that the state would cover the associated debt service. The provisional language did not contain the typical components of a state‑approved capital project. Most notably, the provisional language did not specify the cost, scope, or schedule of the project. Based upon the most recent information available, the project is expected to cost $300 million to complete. Of this amount, $243 million is covered by state General Fund, $45 million by gift funds, and $12 million by campus funds. This project has the highest state‑supported cost of any single capital project ever approved for UC. As one point of comparison, a new medical school building at UC Riverside (opened in fall 2023) had a state‑supported cost of $94 million.

Governor Proposes Two UC Funding “Deferrals.” In May 2022, the administration announced a compact with UC to provide 5 percent annual base General Fund increases through 2026‑27. The Governor’s budget, however, includes no base increase in 2024‑25. The Governor proposes to defer these funds ($228 million) until 2025‑26. The Governor also proposes to defer funding ($31 million) for implementing the third year of a plan to replace nonresident with resident students at three high‑demand UC campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego). In 2025‑26, the Governor is committing to provide UC with a total of $790 million in new General Fund support, consisting of $259 million in one‑time back payments and $530 million in new ongoing funding. The new ongoing funding would build up UC’s base so it could continue accommodating the higher spending level from the prior year moving forward, along with providing a new 5 percent base increase and additional funding for implementing another year of the nonresident enrollment replacement plan.

Governor Proposes One UC Spending Reduction. The Governor proposes eliminating $300 million one‑time General Fund for the California Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy (to be located near UC Los Angeles). The state already has provided $200 million in prior‑year, one‑time funding for the institute. This proposal would remove the remaining one‑time funds that the state had planned to provide for the project in 2024‑25. The administration indicates that the additional funding originally planned for 2024‑25 is no longer needed due to a change in the project. Rather than constructing a new facility, the institute is acquiring and plans to renovate an existing facility.

Core Operations

In this section, we provide background on UC’s core operating costs and how UC generally covers these costs. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed funding deferrals for UC, along with the options UC has identified for responding to those deferrals. We then assess the Governor’s proposed deferrals and make an associated recommendation. (We address nonresident enrollment issues in the “Enrollment” section of this brief, but we address the associated funding deferral in this section.)

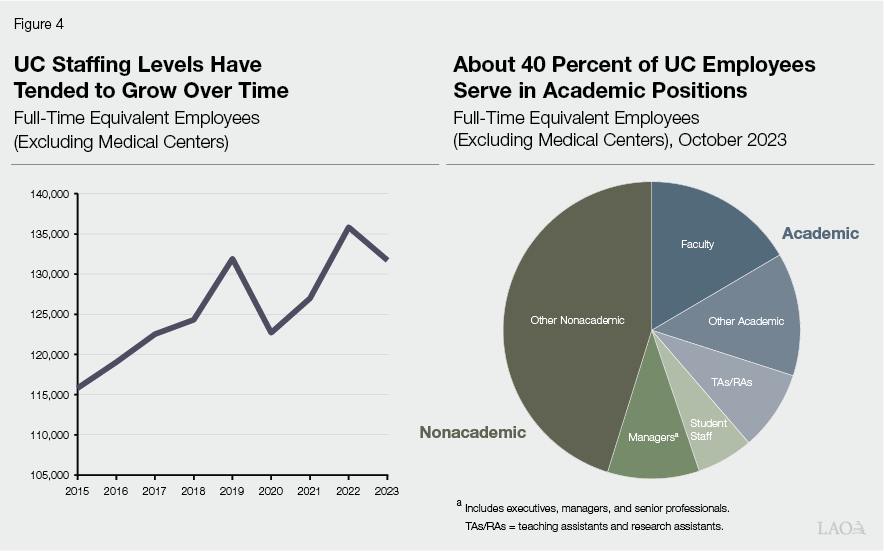

Cost Pressures

UC Has a Large Workforce. In October 2023, UC employed 131,727 FTE campus employees (excluding its medical centers). As the first part of Figure 4 shows, the number of FTE employees at UC generally has been trending upward over time (though UC’s staffing level dipped in 2020 when campuses were most affected by the shift to remote instruction). As the second part of Figure 4 shows, almost 40 percent of UC campus employees currently serve in academic positions, with the remainder serving in various nonacademic roles. In 2023, UC had 1 FTE employee for every 2.3 FTE students. This employee‑student ratio has hovered around 2.3 for the past several years.

UC’s Largest Operating Cost Is Employee Compensation. Like many other state agencies, the largest component of UC’s budget is employee salaries and benefits (comprising 69 percent of its core expenditures in 2022‑23). UC has more control than most state agencies, however, over its compensation costs, partly because most of its employees (approximately 80 percent) are not represented by a labor union. The Board of Regents directly sets salaries and benefits for these employees. UC collectively bargains salaries and benefits for its represented employee groups, negotiating with eight labor unions. As with CSU, the Legislature does not ratify UC’s collective bargaining agreements.

All UC Employee Groups Have Been Receiving Salary Increases. Salaries for UC employee groups—both non‑represented and represented—have been increasing. In 2023‑24, UC provided faculty with a 4.6 percent general salary increase (GSI), along with 1.78 percent merit increases for qualifying faculty. UC also provided non‑represented staff employees with a 4.6 percent GSI. UC’s budget plan for 2024‑25 contains funding to cover another 4.2 percent GSI for non‑represented employees, along with additional funding for the faculty merit program. In 2023‑24, salary increases for represented employee groups varied—ranging from a 3 percent GSI and salary step increases for some groups to more than 15 percent salary increases for academic student employees. UC already has negotiated 2024‑25 salary increases with most of its represented groups. These increases also range from a 3 percent GSI for some groups to more than 15 percent salary increases for academic student employees.

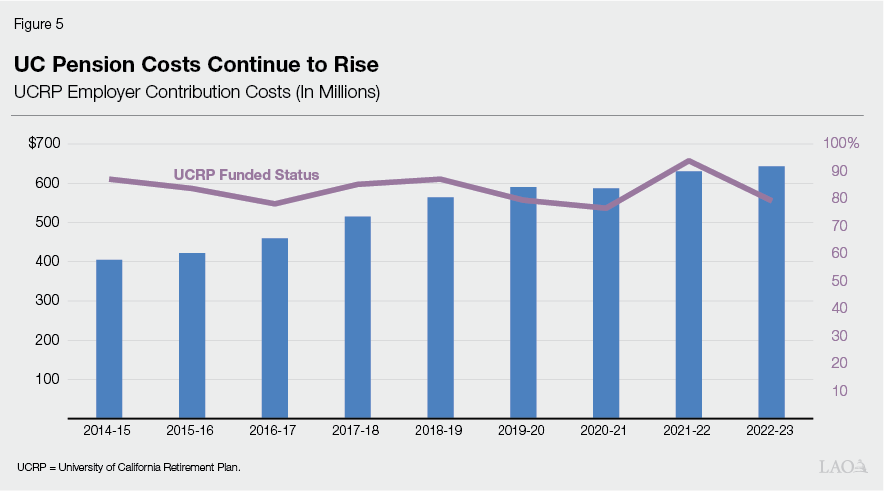

UC Administers Its Own Pension Program, Associated Costs Have Been Rising. UC employees may participate in the University of California Retirement Plan (UCRP). The Board of Regents manages this program. Each year, the Board of Regents determines how much UC should contribute to the pension program. For the last ten years, the UC employer contribution rate has increased gradually—from 14.72 percent of payroll in 2014‑15 to 16.31 percent in 2023‑24. As Figure 5 shows, annual program costs have steadily grown over this period. The program’s funded status (comparing assets to liabilities) has fluctuated but generally has hovered around 80 percent. In 2023‑24, UCRP’s funded status was 81 percent, with $20.4 billion in unfunded liabilities. UCRP’s funded status has tended to be better than other California state retirement plans. The funded status of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), for example, has hovered around 70 percent over the past decade. Looking forward, the UC employer contribution rate is set to increase to 17.72 percent of payroll in 2024‑25. The increase in the 2024‑25 employer contribution rate is largely due to continued implementation of UC’s plan for addressing the program’s unfunded liabilities.

UC Covers the Cost of Health Care Benefits. UC manages health care benefits for both its active employees and retirees. (In contrast to CSU, CalPERS does not administer health care benefits for UC retirees.) A range of health plans are available for UC employees and retirees, with premiums set annually for the respective plans. The share of premium costs that UC covers depends on an employee’s income level, with lower‑paid employees receiving a higher share of their premium costs covered. (For example, in one UC health care plan, employees who are single earning less than $68,000 contribute $100 to their monthly premium, whereas similar employees earning more than $204,000 contribute $239.) UC’s health care spending generally has increased over time, but it has not grown notably as a share of UC’s total core expenditures. Over the past decade, health care spending on behalf of active employees has hovered around 5.7 percent of UC’s total core expenditures. UC estimates that its health care costs for active employees are increasing by $23 million in 2023‑24. UC projects these health care costs to increase by $47 million in 2024‑25, largely due to premiums increasing 7.8 percent—the largest increase in premiums over the past decade.

Costs Also Are Rising for Retiree Health Benefits. Unlike many other state agencies, UC does not pre‑fund retiree health benefits by making contributions while the employee is still working. Instead, UC continues to use a pay‑as‑you‑go approach. Thus, UC’s annual costs are driven by changes in the number of retirees and health care premiums. UC estimates retiree health care costs are increasing by $6 million in 2023‑24. It projects an increase of $11 million in 2024‑25, reflecting a 3 percent increase in the number of retirees, together with higher premiums. UC assesses a payroll charge of 2.23 percent to cover these costs.

UC Is Responsible for Its Facility Upkeep and Growth. Prior to 2013‑14, the state financed UC academic facilities directly through state general obligation bonds and state lease revenue bonds. Chapter 50 of 2013 (AB 94, Committee on Budget) established the current system whereby UC is authorized to sell its own bonds and use a portion of its annual state appropriation to cover associated debt service. As part of this transition, the state shifted $200 million General Fund associated with general obligation debt service into UC’s main state appropriation. As part of UC’s budget, this amount now indirectly grows whenever the state provides UC with a base increase. In such years, this budget approach effectively provides UC some additional capacity to undertake new capital projects. The state also allowed UC to refinance its state lease revenue bonds. The state has authorized $3.3 billion of new academic facility projects under the current system through 2023‑24. UC’s total debt service associated with general obligation bonds, refinanced bonds, and new bonds is $471 million in 2023‑24, up from $386 million in 2022‑23. The large increase is due to the state approving several new projects for UC debt financing last year. Looking forward, UC estimates its debt service costs in 2024‑25 will increase another $10 million, reaching $481 million.

UC Has Large Capital Renewal and Seismic Safety Backlogs. Of the new state‑supported academic facility projects UC has undertaken since 2013‑14, more than $1 billion has been for capital renewal or seismic safety projects. Despite these additional facility projects, UC continues to report large and growing project backlogs. As of January 2024, UC identified $7.5 billion in state‑eligible capital renewal projects, up approximately $900 million from one year ago. In addition to these costs, UC has identified $13.8 billion of state‑supportable seismic safety projects.

Student Financial Aid and Other Cost Pressures Also Exist. Beyond employee compensation and ongoing facility costs, UC faces various other annual cost pressures. The largest remaining cost involves student financial aid programs. UC designates a portion of new student tuition revenue for student financial aid programs, such that any time tuition rates increase or enrollment increases, UC has more funding it directs into its institutional aid programs. In 2024‑25, UC is planning for large increases in funding for institutional aid, with an additional $75 million generated from tuition increases and another $17 million generated from planned enrollment growth. Though much smaller in magnitude, UC also can experience cost increases relating to operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). OE&E costs tend to grow with inflation over time, though UC tries to contain these costs through operational efficiencies.

Funding

UC Covers Its Operating Cost Increases From Two Main Sources. UC’s largest core fund source is student tuition and fee revenue. In 2023‑24, 52 percent of its ongoing core funds came from this source. UC also relies notably on state General Fund support for its core operations, with 45 percent of its ongoing core fund coming from this source in 2023‑24. Since 2013‑14, the state has provided UC with General Fund base increases every year but one. (In 2020‑21, the state reduced General Fund base support due to a projected shortfall, but it restored funding the following year.)

UC Continues Implementing Its Tuition Stability Plan. A few years ago, the Board of Regents approved a UC tuition policy. Under this policy, tuition is increased annually for new undergraduates and all graduate students, while remaining flat for continuing undergraduates. Tuition increases generally are based on a three‑year rolling average of the annual change in the California Consumer Price Index, with a cap of 5 percent (unless increased by the Board of Regents). The first year of tuition increases under this policy was 2022‑23. In 2024‑25, tuition and systemwide fee rates are set at $14,436 for new undergraduate resident students, reflecting an increase of $684 (5 percent). In 2024‑25, UC estimates generating an additional $191 million in revenue from tuition increases. It plans to use $75 million of this additional revenue for institutional student financial aid. (In addition, the California Student Aid Commission budget includes $43 million in higher associated Cal Grant costs for UC students in 2024‑25. Many UC students with financial need receive full tuition coverage under the Cal Grant program.)

UC Also Relies on Various Alternative Fund Sources. In recent years, UC has begun using certain investment earnings from its asset management program to support its operations. In 2024‑25, UC has identified $90 million in investment earnings that it intends to use to support its operating cost increases. In recent years, UC also has been achieving savings through operational efficiencies and procurement savings that it redirects back into its core operations. In 2024‑25, UC is anticipating $11 million from these savings. Lastly, some campuses continue to grow their nonresident enrollment. In 2024‑25, UC estimates those campuses will collect a combined $4.1 million in additional associated nonresident supplemental tuition revenue. UC also uses this revenue to support its operations.

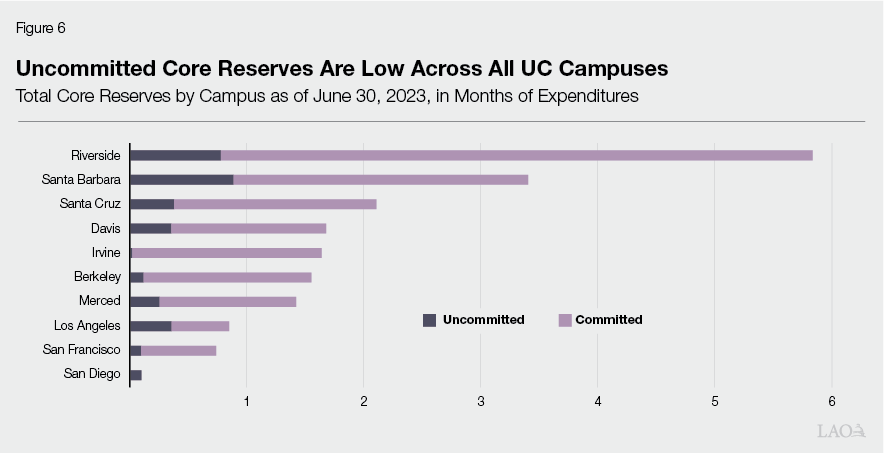

UC Has Core Reserves. Like many other universities (as well as public and private entities more generally), UC maintains reserves. UC commits part of its reserves for planned activities, such as faculty recruitment and retention, certain capital outlay costs, and other strategic program investments. It leaves some reserves uncommitted, such that they are available to address economic uncertainties, including state budget reductions. Some, but not all, of UC’s reserve commitments could be revisited in the face of a fiscal downturn. Whereas CSU has a systemwide policy that aims to have core uncommitted reserves equivalent to three to six months of operating expenses, UC does not have a systemwide reserve policy. As of June 2023, UC reported $1.4 billion in total core reserves, of which $238 million was uncommitted. UC’s uncommitted reserves equate to nine days (2.5 percent) of its total annual core operating expenditures.

Campus Reserve Levels Vary. In the absence of a systemwide reserves policy, UC allows its ten campuses to determine their own reserve levels. Campus policies vary but typically aim for uncommitted core reserves worth one to three months of core expenditures. Figure 6 shows core reserves at each UC campus as of June 30, 2023. Total core reserves (committed and uncommitted combined) ranged from less than one month of expenditures at the San Diego campus to almost six months of expenditures at the Riverside campus. Uncommitted reserves for economic uncertainties, however, equated to less than one month of expenditures at all campuses. In dollar terms, uncommitted core reserves ranged from as little as $2.1 million at UC Irvine to $51 million at UC Santa Barbara.

Governor’s Proposals

Governor Proposes to Defer General Fund Base Increase. Two years ago, the Governor made a compact with UC to provide annual 5 percent unrestricted base increases from 2022‑23 through 2026‑27. (The compact is not codified, and the Legislature decides through the annual budget process which, if any, of the components it will enact.) The Governor’s budget does not fund the third year of the base increases. Instead, the Governor proposes to delay the associated $228 million in ongoing funding until 2025‑26. As Figure 7 shows, the Governor intends to double up funding in 2025‑26, such that UC would receive a base increase to support the higher level of prior‑year ongoing spending ($228 million), along with a new 5 percent base increase ($241 million)—for a total increase of $469 million in ongoing General Fund support that year. In addition, the Governor intends to provide UC with a one‑time back payment of $228 million in 2025‑26 to compensate for the foregone funds in 2024‑25. The administration describes this proposal as a deferral of the third‑year compact payment. The Governor expects UC to spend at the higher assumed level in 2024‑25 by using interim financing, such as drawing down its reserves or borrowing. The Governor gives UC discretion to choose its corresponding spending priorities.

Governor Also Proposes to Defer Nonresident Enrollment Replacement Funding. UC has committed to reducing nonresident enrollment at three campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) in order to free up space for more resident undergraduates. Under a multiyear plan, these three campuses are to lower their nonresident enrollment so that it comprises no more than 18 percent of total undergraduate enrollment by 2026‑27. The past two years, the state has provided UC with funding to offset the associated loss of nonresident supplemental tuition revenue. The Governor proposes deferring $31 million linked to the third year of this plan. As Figure 7 shows, like with the base deferral, the Governor intends to double up this funding in 2025‑26, such that UC would receive $62 million ongoing General Fund in 2025‑26. The Governor also would provide a one‑time back payment of $31 million in 2025‑26 to compensate for the foregone funds in 2024‑25. Though the Governor defers the nonresident enrollment replacement funding, the budget bill contains provisional language specifying that UC continue implementing the nonresident enrollment replacement plan in 2024‑25.

UC’s Plan

UC Has Identified Its Spending Priorities. As Figure 8 shows, UC has identified a total of more than $650 million in new spending priorities for 2024‑25. These spending priorities include covering cost increases for UCRP, student financial aid, and employee health benefits, along with providing salary increases to non‑represented and represented staff. UC indicates that its spending priorities exceed the amount available to it under the Governor’s compact by nearly $70 million. As of this writing, UC had not yet determined how it would align its spending priorities with available funding.

Figure 8

UC Has Identified Several

Spending Priorities

Planned Spending Increases, 2024‑25 (In Millions)

|

Spending Priorities |

|

|

Retirement contributions |

$105 |

|

Student financial aid increases |

92 |

|

Represented employee salary increases |

90 |

|

Faculty general salary increases |

89 |

|

Non‑represented staff salary increases |

75 |

|

Enrollment growth |

58 |

|

Health benefits for active employees |

46 |

|

Operating expenses and equipment |

45 |

|

Faculty merit program |

39 |

|

Health benefits for retirees |

11 |

|

Other |

4 |

|

Total |

$653 |

In Response to Proposed Deferrals, UC Could Use Its Reserves. One option UC is exploring in response to the Governor’s proposed funding deferrals is drawing down its uncommitted core reserves. UC’s uncommitted core reserves ($238 million), however, are not sufficient to cover the proposed $259 million in deferrals entirely. Moreover, entirely depleting reserves for economic uncertainty is considered poor fiscal practice, as it leaves entities unequipped to deal with unexpected issues that might arise throughout the year. Entirely depleting UC’s core reserves for economic uncertainty could place at least some UC campuses in fiscal distress in 2024‑25 if such emergencies arose.

UC Indicates Its Reserves Generally Are Held in a Short‑Term Investment Account. UC indicates that it holds its reserves generally in its Short Term Investment Pool (STIP). STIP holds cash primarily slated for payroll and other common expenses for all UC campuses and medical centers. As of June 30, 2023, UC reported that STIP held $4.2 billion (after backing out certain restricted funds). If UC were to borrow $259 million from STIP (in quarterly installments), it anticipates an effective interest rate of approximately 3 percent. (Though STIP investment returns average approximately 4.5 percent annually, UC would not need to borrow the full $259 million for a full 12 months, assuming the state was able to make the back payment early in fiscal year 2025‑26.) At this point in time, UC indicates this internal borrowing likely would be its lowest‑cost financing option. If the state ultimately were to adopt funding deferrals for UC, UC indicates it would re‑evaluate its internal and external borrowing options at that time.

Assessment

Proposed Funding Delay Worsens State’s Projected Out‑Year Budget Deficits. As we discuss in The 2024‑25 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state faces significant operating deficits in the coming years. The Governor’s proposed funding delay for UC worsens those deficits, as we discuss in The 2024‑25 Budget: Higher Education Overview. Under the proposed approach, the state would need to increase General Fund spending for UC by $790 million in 2025‑26—consisting of a $531 million ongoing augmentation and an additional $259 million one‑time back payment. Rather than increasing university costs, the state historically has contained these costs when facing multiyear budget deficits.

Proposed Approach Increases Out‑Year Risks for the State. Both our office and the administration project the state faces an operating deficit of more than $30 billion in 2025‑26. Given this projected deficit, increasing spending on UC in that year would require a like amount of other budget solutions. The Legislature likely will have fewer options for budget solutions next year, with lower reserves and less one‑time spending available to pull back. At that time, the Legislature might face the difficult choice of either cutting other ongoing state programs to make room for the additional UC spending or, alternatively, forgoing the increase it had committed to providing UC.

Proposed Approach Also Increases Out‑Year Risks for UC. Although the Governor’s proposal benefits UC in 2024‑25 by allowing it to increase spending, it comes with heightened risks for UC the following year. Under the proposed approach, UC would be entering 2025‑26 with higher ongoing spending and potentially depleted core uncommitted reserves. If the state were then unable to support that higher spending level in 2025‑26, UC could need to consider significant reductions at that time. Depending upon the severity of the budget situation, UC might consider actions such instituting hiring freezes or furloughs, both of which it has done over the years in response to previous state budget cuts. These types of actions would negatively impact both employees and students, as they likely would lead to fewer classes and a reduction in support services. Moreover, such actions would likely be more disruptive than containing spending increases in the first place.

Without a Base Increase, UC Still Could Cover Some Cost Increases in 2024‑25. If the state were to forgo rather than delay the base increase planned for 2024‑25, UC would have less ability to increase spending on various purposes, including employee compensation. It would, however, still have some options for covering a portion of its cost increases. Most notably, UC estimates it will generate $117 million in additional tuition revenue (net of financial aid) and have $105 million from alternative fund sources available for addressing operating cost increases. It also could draw down some of its uncommitted core reserves to cover certain cost increases that it cannot avoid in the near term, such as health care premium increases, absent a General Fund increase for 2024‑25.

Recommendation

Hold State Funding and Spending Expectations Flat for UC, Revisit Next Year. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposals to defer, then double up, funding for UC. Such an approach substantially worsens the state’s projected deficit in 2025‑26, and it is risky for the state, UC, and other state programs that might be cut more deeply in 2025‑26 to make room for the additional UC spending. Rejecting the Governor’s proposals provides $790 million in budget savings, more than $500 million of which is ongoing, beginning in 2025‑26. By taking this action this year, the Legislature can mitigate the need for other, potentially more disruptive, budget solutions next year. As long as the state is projected to have large, multiyear budget deficits, we caution against raising UC’s General Fund spending levels or expectations. We recommend the Legislature take a more prudent approach to crafting its budget that aims to contain UC spending. If the state budget situation were to improve in 2025‑26, the state would then be in the more advantageous position of being able to set a UC base increase that it can afford at that time.

Enrollment

In this section, we first provide background on the state’s approach to funding enrollment growth at UC and cover UC enrollment trends. We then discuss the Governor’s enrollment proposals along with UC’s corresponding enrollment plans. Next, we assess those proposals and make associated recommendations.

Background

UC Enrolls a Mix of California Resident and Nonresident Students. In 2022‑23, of the nearly 290,000 FTE students UC enrolled, 81 percent were California residents and 19 percent were nonresidents. Compared to the other two segments, UC enrolls a notably larger share of nonresident students. (About 5.5 percent of CSU FTE students are nonresidents and about 3.5 percent of CCC FTE students are nonresidents.) Within UC, nonresident students are more common in graduate programs. Whereas approximately one‑third of UC graduate students are classified as nonresidents, approximately 15 percent of UC undergraduates are nonresidents.

UC Enrolls a Mix Freshmen and Transfer Students. Besides aiming to enroll a mix of resident and nonresident students, UC tries to have each new incoming undergraduate class have a certain share of freshmen and transfer students. Specifically, UC aims to enroll one resident transfer student for every two resident freshmen. In fall 2023, UC fell somewhat short of its transfer goal, with 70 percent of its new resident undergraduates being freshmen while 30 percent were resident transfer students. UC achieved its goal a few years ago, but the transfer pipeline shrank notably during the pandemic years and is just beginning to rebound.

State Typically Sets Resident Enrollment Targets and Provides Associated Funding. Over the past two decades, the state’s typical enrollment approach for UC has been to set systemwide resident enrollment targets. These targets typically have applied to total resident enrollment, giving UC flexibility to determine the mix of undergraduate and graduate students. If the total systemwide target has included growth (sometimes the state leaves the target flat), the state typically has provided associated General Fund augmentations. Augmentations have been calculated using an agreed‑upon per‑student funding rate derived from the “marginal cost” formula. This formula estimates the cost to enroll each additional student and shares the cost between the state General Fund and student tuition revenue. In 2023‑24, the total marginal cost per student is $21,137, with a state share of $11,640.

Recently, State Has Made Two Modifications to Its Enrollment Growth Approach. One modification is that the state has been setting enrollment growth targets only for undergraduates. Another modification is that the state generally has been trying to better align its targets with UC’s admissions cycle. UC completes its admissions cycle for the coming fall term before the state enacts the annual budget each June. Setting an enrollment growth target for budget year plus one allows the state to influence UC’s planning for the next admissions cycle.

State Continues Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Plan. Another important change in recent years is that the state has acted to limit the number of nonresident undergraduates at UC, with the intent to make more slots available for resident undergraduates at high‑demand campuses. Specifically, the state has directed UC to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by a total of 902 FTE students annually and increase resident undergraduate enrollment by the same amount. The nonresident enrollment reduction plan began in 2022‑23 and is intended to extend through 2026‑27. By 2026‑27, all UC campuses are to have nonresident students comprise no more than 18 percent of their total undergraduate enrollment. (The 18 percent cap applies to all UC campuses, but only the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses currently are notably above that cap.)

Last Year’s Budget Act Included 2023‑24 Enrollment Growth Expectations. Specifically, the state set an expectation in the 2023‑24 Budget Act that UC grow by 7,800 resident undergraduate FTE students in 2023‑24 over the 2021‑22 level. This growth target consisted of three components. First, the state provided $51.5 million to grow resident undergraduate enrollment by 4,730 students. Second, the state provided $30 million for UC to replace an additional 902 nonresident students with resident students at its three highest‑demand campuses. Third, the state directed UC to grow by an additional 2,168 resident students using part of its General Fund base augmentation. Altogether, the state expected UC to enroll a total of 203,661 resident undergraduate FTE students in 2023‑24. The budget act included provisional language allowing the administration to reduce funding if UC fell short of this target. In this case, the Director of the Department of Finance may reduce UC funding at the state marginal cost rate of $11,640 for each student slot below the target.

Last Year’s Budget Act Also Included Enrollment Growth Expectations for the Next Few Years. Specifically, the 2023‑24 Budget Act set an expectation that UC grow by 2,927 resident undergraduate FTE students in 2024‑25, 2,947 FTE students in 2025‑26, and 2,968 FTE students in 2026‑27. These amounts reflect annual growth of 1.4 percent. The state’s intent was that UC would fund this new growth from base General Fund augmentations provided in each of the next three years.

UC Has Graduate Enrollment Goals for Next Few Years. Unlike for UC undergraduates, the state has not been setting enrollment targets for UC graduate students. The Governor and UC, however, have compact goals relating to graduate enrollment. Specifically, UC set a plan to increase enrollment in its state‑supported graduate programs by a total of 2,500 students (resident and nonresident students combined) over four years. UC originally intended to add this enrollment in even increments (625 FTE students per year) beginning in 2023‑24 and extending through 2026‑27. Though not earmarked in the state budget act, graduate enrollment growth is supported by state funding and tuition revenue, among other sources.

Trends

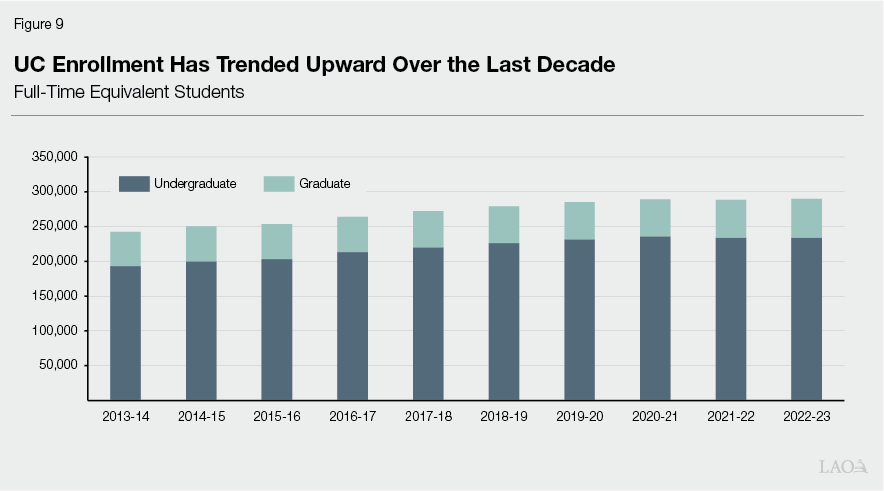

UC Enrollment Has Grown Over the Past Decade. As Figure 9 shows, UC enrollment has increased every year but one (2021‑22) over the past decade. Total enrollment has grown by approximately 47,000 FTE students (19 percent). As total enrollment has increased, the share of undergraduate and graduate students has remained about the same, with about 80 percent being undergraduates and 20 percent being graduate students. Undergraduate enrollment growth has varied somewhat across UC campuses. Over the past decade, UC Santa Cruz has experienced the least amount of growth. UC San Diego has added the greatest number of undergraduates, and UC Merced has grown at the fastest rate.

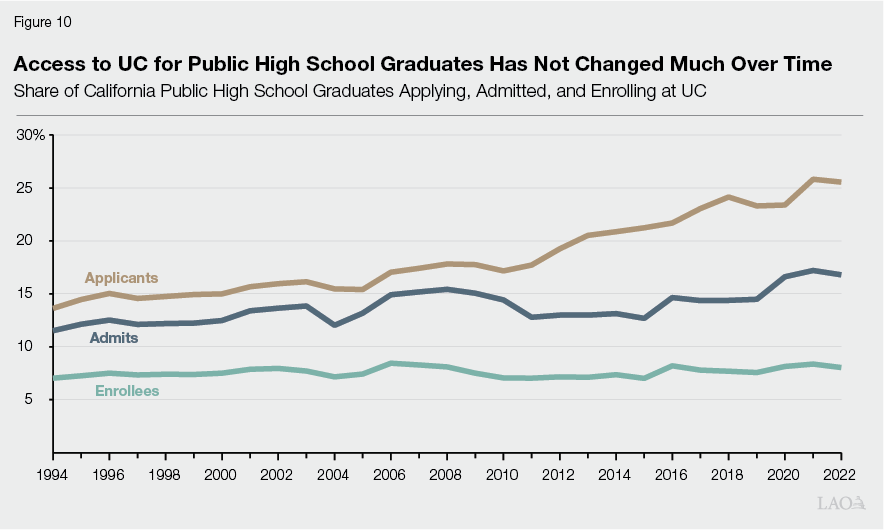

Number of Resident Undergraduate Applicants Has Been Increasing. From fall 2013 through fall 2022 (the most recent data available), the number of resident undergraduate UC applicants increased notably. In 2013, about 129,000 unique resident applicants applied to UC. (Some applicants apply to multiple UC campuses.) By 2022, UC had about 168,000 unique applicants, reflecting a 30 percent increase. Growth was faster among freshman applicants (33 percent) than transfer applicants (19 percent). As the number of applicants has grown, so too has the share of California public high school graduates applying to UC. In 1994, 13.6 percent of California public high school graduates applied to UC (generally in line with state master plan expectations that UC draw from the top 12.5 percent of high school graduates). A decade later, this share had risen slightly (by 1.8 percentage points). By 2014, however, the share was up to 21 percent, and, by 2022, it was up to 26 percent. (We cover these trends in more detail in Trends in Higher Education: Student Access.)

Resident Freshman Admission Rates Generally Have Been Declining. As the number of resident applicants have increased over the past decade, all but two UC campuses (Riverside and Merced) have lowered their freshman admission rates. For example, UC Berkeley admitted 18 percent of applicants in 2012, compared to 14 percent in 2022. The trend is different for transfer students, with only four of the nine general campuses lowering their transfer admission rates. UC Berkeley, for example, increased its admission rate for transfer students, from 22 percent in 2012 to 25 percent in 2022.

Enrollment of California Public High School Graduates Has Not Changed Much. Though student demand for UC has increased markedly and freshman admission rates have also generally increased, access to UC among California public high school graduates has not changed much over the past nearly 30 years. As Figure 10 shows, the share of California public high school graduates who enroll at a UC campus has changed only slightly—from 7 percent in 1994 to 8 percent in 2022.

UC Enrollment Trends in 2023‑24 Are Mixed. UC estimates that its total FTE enrollment will increase in 2023‑24 by 1 percent. Growth in resident undergraduate enrollment accounts for all of the expected growth. UC estimates that its resident undergraduate enrollment will increase 5,167 students (2.6 percent) above the 2022‑23 level. New resident freshman enrollment is expected to increase by 5.2 percent, while enrollment from new resident transfer students is expected to increase by 0.2 percent compared to fall 2022. An expected drop in nonresident undergraduate enrollment will offset some of this growth. UC also estimates its graduate enrollment will be down by 1,570 FTE students (3 percent) from 2022‑23. UC indicates that campuses were more conservative enrolling new doctoral students in 2023‑24 due to funding concerns.

Governor’s Proposals

Governor Maintains Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Growth Expectations Set in Compact. Consistent with his compact with UC, the Governor expects UC to increase resident undergraduate enrollment by 1 percent annually through 2026‑27. The administration retains provisional budget language allowing the Director of the Department of Finance to reduce UC funding if a target is not met. Specifically, for each student below the 2024‑25 target, UC funding could be reduced at the state marginal cost rate of $11,930. Under the compact, UC is expected to accommodate enrollment growth from within its 5 percent annual base General Fund increases. The Governor’s budget makes no changes to these enrollment expectations, although it delays the planned base General Fund increase until 2025‑26. (We discuss this delay in the “Core Operations” section of this brief.)

Governor Also Maintains Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Expectations. The Governor’s budget also maintains the expectation that UC continue to reduce nonresident enrollment by a total of 902 FTE students at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses in 2024‑25, replacing those students with resident undergraduates. As with the base funding deferral, the Governor proposes to defer $31 million ongoing General Fund that otherwise would have been provided in 2024‑25 to continue implementing the nonresident enrollment reduction plan. The $31 million is intended to backfill UC for the associated loss of nonresident supplemental tuition revenue. Under the Governor’s approach, UC would use other means to implement the plan as it awaits state funds next year.

UC’s Plans

UC Expects to Get Close to Its Undergraduate Enrollment Target in 2023‑24. Based on data from the summer and fall 2023 terms, UC estimates that its resident undergraduate enrollment is 1,383 FTE students below the 2023‑24 Budget Act target for 2023‑24. UC indicates that it likely will get closer to its target for 2023‑24 over the coming months. UC will finalize its 2023‑24 enrollment counts later this year after it has better data on student unit‑taking.

UC Plans to Meet Its Out‑Year Enrollment Targets. Despite being somewhat below its 2023‑24 enrollment target, UC believes that it can meet the enrollment targets set for it in each of the next few years. The exact amount UC would need to grow in those years to reach its targets will depend on its final 2023‑24 enrollment level, but the annual growth is likely to be about 3,000 resident undergraduate FTE students. Though UC plans to remain on track to meet these enrollment targets, its plans could change if the state does not provide UC with annual base General Fund augmentations.

UC Expects to Meet Its Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Goals in 2023‑24. Compared to the fall 2022 term, nonresident undergraduate enrollment in the fall 2023 term declined at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by an estimated 1,138 FTE students. This exceeds the state reduction target of 902 FTE students. Each of the three campuses made progress toward lowering its nonresident enrollment and increasing its resident enrollment. UC San Diego made the most progress, accounting for 43 percent of the reduction in nonresident enrollment across the three campuses.

UC Expects to Continue Meeting Its Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Goals. Despite the proposed deferral, UC indicates that it plans to continue implementing the nonresident enrollment reduction plan. Specifically, UC anticipates replacing a total of 1,036 FTE nonresident undergraduate students with resident students at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses in 2024‑25. Given the Berkeley campus needs to make the most progress among the three campuses, its reduction target would be greater than the other two campuses. Specifically, UC plans for the Berkeley campus to reduce nonresident enrollment by 554 FTE students, whereas the other two campuses each would have reduction targets of around 250 FTE students. The fiscal impact of the proposed deferral would be experienced at these three campuses. UC could change these plans were the Governor to change his deferral proposal.

Assessment

Undergraduate Demand for UC Remains High. Based on preliminary data, UC estimates the number of unique resident applicants in fall 2024 will increase over fall 2023. New unique resident freshman applicants are expected to grow by 1.3 percent, marking another year of being the highest number of such applicants in UC history. UC estimates the number of transfer applicants will grow 9.7 percent, likely indicating some rebound in the transfer pipeline.

Despite High Demand, Some Signs That Meeting Targets Is Becoming Somewhat More Difficult. While the new freshman cohort is estimated to increase for 2023‑24, UC indicates that several campuses needed to go further into their waitlists later in the admissions cycle last year, which left a few campuses short of their enrollment targets. Additionally, UC’s first‑to‑second‑year retention rate declined for three consecutive years (from 2019 through 2021)—dropping by 0.9 percentage points. UC attributes this decline to challenges students encountered during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Even a small decline in retention rates makes meeting enrollment targets more difficult.

Demographic Trends Could Potentially Limit Growth in Out‑Years. While the number of new freshmen enrolling at UC has increased in four of the past five years, demographic trends could limit this growth moving forward. Based on the most recent projections from the Department of Finance, the number of high school graduates in California is expected to peak in 2023‑24. The number of high school graduates is projected to decline by 40,097 students (9 percent) from 2023‑24 to 2026‑27. Such a decline typically would translate into smaller new freshman cohorts in the out‑years. More broadly, California’s college‑age population (ages 18‑24) already has been declining and is projected to continue declining. Since 2012, California’s college‑age population is estimated to have declined by about 10 percent. Over the next five years, it is projected to decline by another 4 percent. This demographic trend also is expected to relieve enrollment pressure at UC.

CSU Has Enrollment Capacity. As we discuss in The 2024‑25 Budget: California State University, CSU’s existing enrollment level is substantially lower than its funded target. We estimate CSU could enroll an additional approximately 24,000 FTE students from within its existing budget, accounting for all the state enrollment funding CSU has been provided to date. Were the state not to be able to afford enrollment growth at UC over the next year, the impact on students would be mitigated given the additional room available at CSU.

Budget Situation Has Changed From June 2023. When the state set its enrollment expectations for UC in the 2023‑24 Budget Act, the state budget condition appeared notably better than it does today. As we noted in The 2024‑25 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state now faces large projected operating deficits for the next several years. Should the Legislature wish to continue funding resident undergraduate growth at UC, these increased costs would require a like amount of other budget solutions elsewhere.

Recommendations

Revert Any Unearned 2023‑24 Enrollment Growth Funds. After the state enacts the 2024‑25 budget, UC will finalize its enrollment counts for 2023‑24. If actual enrollment that year falls short of the state target, we recommend the state revert any unearned funds as part of the 2025‑26 budget. Existing provisional budget language allows this reduction to occur administratively, without requiring legislative action. (Legislative action would be needed only if the Director of Finance chose not to exercise this authority.) Based on UC’s 2023‑24 enrollment estimates as of February 2023, $16 million in enrollment growth funding has been unearned.

Hold UC’s Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target Flat for 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. Consistent with our recommendation in the previous section of this brief to hold state funding for UC flat, we recommend holding UC’s enrollment target at the current level of 203,661 resident FTE students for 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. While student demand to attend UC generally is strong, the state budget at this time cannot afford to fund enrollment growth at UC unless it can find spending reductions or revenue increases elsewhere in the budget. Moreover, even without raising UC’s enrollment target for 2024‑25 or 2025‑26, UC still could add some students. At its existing funded level, UC still has some room to grow (by as many as 1,383 FTE students). Furthermore, CSU has considerable room to accommodate undergraduate enrollment growth within its existing funded level.

Reserves Are an Option for Keeping the Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Plan on Track. Given student demand is so strong at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses, the state might want to request that UC use its system reserves for the specific purpose of keeping the nonresident enrollment reduction plan on track. If UC were to continue implementing this plan in 2024‑25, as it now expects to do, more than 1,000 slots for resident undergraduate students would become available at UC’s highest‑demand campuses. Though the associated enrollment costs are ongoing, using system reserves for this specific purpose for a year or two would help relieve substantial enrollment pressures at these campuses. While using reserves for ongoing enrollment costs is not sustainable over many years, the approach might be considered on a temporary basis given the nonresident enrollment reduction plan has been such a high legislative priority.

Budget Solutions

In this section, we first discuss the Legislature’s options for achieving budget savings at UC by pulling back unspent one‑time funding from prior budgets. Although the Governor does not propose any such actions for UC, pulling back these funds likely would be less disruptive than many of the other options the state has for addressing its projected budget deficits. We then provide an update on various UC capital projects that the state recently approved and make a few associated recommendations.

State Adopted Many One‑Time Initiatives Over Past Three Years. From 2021‑22 through 2023‑24, the state appropriated a total of $1.3 billion one‑time General Fund to UC for about 40 one‑time initiatives. (These amounts exclude capital projects that the state converted from cash funding to debt financing, as we discuss at the end of this section.) The state adopted these one‑time appropriations in response to the large operating surpluses originally estimated for 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. Designating funds for one‑time purposes when the state has a surplus can be a prudent approach, as it avoids building up ongoing programs, particularly when revenues could be spiking and potentially contract in subsequent years. Now that prior surpluses have been replaced with projected multiyear deficits, the state could revisit recent one‑time initiatives to determine how much associated funding remains unspent. The more funds the Legislature pulls back from previous one‑time initiatives now, the less the Legislature might need to turn to ongoing programs for budget solutions moving forward.

Recommend Pulling Back Unspent One‑Time Funding From Prior Budgets. Based on a data request to UC, our preliminary estimate is that $325 million of the $1.3 billion in one‑time funding for UC has not yet been encumbered or spent by campuses as of January 1, 2024. (An additional $11 million has not yet been encumbered for the UC Riverside Center for Environmental Research and Technology, though UC anticipates awarding a design‑build contract in February 2024 and committing the remainder of project funds in April 2024.) As Figure 11 shows, most of the remaining funding is associated with campus‑specific initiatives, many of which have a research focus. We recommend the Legislature pull back all of the unencumbered and unspent one‑time funds from these initiatives, achieving a like amount of General Fund savings. To maximize potential savings, the Legislature might want to take early action, as doing so would ensure that additional funds are not spent before the end of the fiscal year.

Figure 11

Some One‑Time Funding From Recent UC Initiatives Remains Unspent

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Recent One‑time Initiatives |

Maximum Available Fundsa |

|

Campus‑specific climate change initiatives |

$83.3 |

|

UC San Diego Scripps Reserve Vessel |

34.8 |

|

UC Berkeley Local Public Affairs Grant Initiative |

23.1 |

|

California Institutes for Science and Innovation |

18.6 |

|

UC Davis Institute for Regenerative Cures |

16.1 |

|

UC Los Angeles Latino Policy and Politics Institute |

13.7 |

|

UC Riverside School of Medicine operations |

13.6 |

|

K‑14 Student Academic Preparation and Educational Partnerships |

12.6 |

|

UC Los Angeles Ralph J. Bunche Centerb |

14.2 |

|

UC San Francisco Dyslexia Centerc |

13.2 |

|

UC‑CSU Collaborative on Neurodiversity and Learning |

8.8 |

|

UC Los Angeles Asian American and Pacific Islander Multimedia Textbook Project |

7.9 |

|

Animal Shelter Assistance Act |

7.1 |

|

Cancer research relating to firefighters |

7.0 |

|

UC Berkeley School of Journalism Police Records Access Project |

6.7 |

|

UC Institute of Transportation Studies |

5.9 |

|

UC Riverside Survey of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans |

5.4 |

|

Equal Opportunity Practices and professional development for UC faculty |

5.0 |

|

UC Davis Equine Performance and Rehabilitation Center |

5.0 |

|

UC San Diego Student Mental Health App |

4.6 |

|

Plant‑based and cultivated meat research |

4.6 |

|

Climate Change Research and Entrepreneurship Grants |

4.0 |

|

UC Los Angeles Institute on Reproductive Health, Law, and Policy |

3.2 |

|

UC San Diego Scripps Institute Fire Camera Mapping System |

3.2 |

|

K‑12 Subject Matter Projects in Learning Loss Mitigation |

2.5 |

|

UC Merced Center on Food Resilience |

1.3 |

|

Total |

$325.4 |

|

aReflects amount not spent or encumbered by campuses as of January 1, 2024. bReflects total amount of unencumbered funds from 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24. cReflects total amount of unencumbered funds from 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. |

|

Last Year, State Converted Some Capital Projects From Cash to Debt Financing. At the height of the state’s budget surpluses, the state approved many new capital projects and decided to fund those projects up front with General Fund cash. In 2023‑24, facing a moderate budget deficit, the state converted many of those projects from cash funding to debt financing. As Figure 12 shows, for UC specifically, the state reverted $1.2 billion in one‑time General Fund associated with a total of 11 capital projects. Instead of receiving cash for these projects, UC is to debt financing them using university bonds. The state appropriated $84 million ongoing General Fund for UC to cover the debt service associated with the 11 projects altogether.

Figure 12

Many Debt‑Financed Capital Projects at UC Remain in Early Phases

(In Millions)

|

Project |

Project Costa |

Annual Debt Service |

Bond Issuedb |

Current Phasec |

|

Student Housing Projects |

||||

|

Riverside/Riverside City College |

$126.0 |

$8.9 |

Yes |

C |

|

Santa Cruz/Cabrillo College |

111.8 |

8.1 |

No |

P |

|

Merced/Merced College |

100.0 |

7.1 |

No |

P |

|

Berkeley |

100.0 |

6.8 |

Yesd |

C |

|

San Diego—Pepper Canyon West |

100.0 |

6.8 |

Yes |

C |

|

Santa Cruz—Kresge College |

89.0 |

6.1 |

Yes |

C |

|

Irvine |

65.0 |

4.4 |

Yes |

C |

|

Los Angeles |

35.0 |

2.4 |

Yes |

W,C |

|

Subtotals |

($726.8) |

($50.7) |

||

|

Other Projects |

||||

|

Berkeley Clean Energy Project |

$249.0 |

$16.7 |

Yes |

P,C |

|

Riverside campus expansion project |

154.5 |

10.3 |

Yesd |

P |

|

Merced campus expansion project |

94.5 |

6.3 |

No |

P |

|

Subtotals |

($498.0) |

($33.3) |

||

|

Totals |

$1,224.8 |

$84.0 |

||

|

aReflects state cost of project (excluding nonstate costs). bUC issued bonds in September 2023 and February 2024. cReflects project status as of January 1, 2024. dUC indicates that it has drawn commercial paper for these projects. |

||||

|

P = preliminary plans; W = working drawings; and C = construction. |

||||

Recommend Pausing Projects for Which UC Has Not Sold Bonds. Based on a data request to UC, three of the capital projects recently converted to debt financing remain in the preliminary planning phase and have no associated debt. That is, UC has not yet sold bonds for any of these projects. The projects are estimated to cost a total of $306 million. The state budgeted $22 million to cover the associated debt service. We recommend the Legislature pause these projects and remove the $22 million ongoing General Fund from UC’s budget. Pausing these projects now not only helps the state address its projected multiyear budget deficits, it also helps reduce cost pressures for decades to come, as it would avoid creating new facilities that would need to be maintained over time.

Recommend Pausing New UC Merced Medical Education Building. In 2019‑20, the state approved a new medical education building at or near the UC Merced campus. The state authorized UC to finance the new building using UC bonds, with the state committing to cover the associated debt service. Based on the most recent estimates, this project has a state cost of $243 million (the most expensive state‑supported UC project to date). The Governor is proposing to provide $14.5 million beginning in 2024‑25 to cover the associated debt service. While having entered into a construction contract for the project, UC indicates that it has neither drawn commercial paper nor issued a revenue bond for the project. Under the existing project schedule, construction is to begin in summer 2024 and be completed by fall 2026, with the building opening to students in fall 2027. We recommend pausing this project and removing the $14.5 million ongoing General Fund for debt service from UC’s budget. The state could revisit the project once its budget condition improves.

Recommend Aligning Funding With Estimated Debt Service Costs. Whereas the state’s typical fiscal practice is to cover actual debt service costs when they become due, the state forward‑funded UC for debt service on all the projects noted above. That is, the state provided the funds before UC had issued bonds and knew its actual debt service costs. Because UC has not yet sold bonds for all of the approved projects, it has not needed all the associated state funding. We estimate UC has at least $50 million in unspent debt service funding in 2023‑24. The state could achieve some one‑time savings by aligning the state appropriation for debt service with UC’s actual debt service costs. The state could continue to achieve some one‑time savings until UC has sold all the bonds. The amount of one‑time savings would shrink over the next few years as additional bonds are sold.