Sonia Schrager Russo

February 21, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

Overview of the Federal CalWORKs Pilot

Update on Federal Pilot. In March 2025, the federal government notified the five previously selected pilot states—California, Maine, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Ohio—that these states were deselected from the pilot project. The federal Administration for Children and Families (ACF) indicated it plans to take a new approach to the pilot program and will issue a new request for proposals from states. The previously selected pilot states will not be subject to work participation rate requirements for federal fiscal year 2025. More information is available on the ACF website.

Summary. California was recently selected as one of five states to participate in a federal, six-year pilot to test new Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program performance metrics focused on long-term employment and family well-being. In this post, we provide background on California’s TANF program, the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program, information on the pilot and California’s pilot application, and comments and questions for the Legislature to consider surrounding the implementation of the pilot. The Governor’s budget does not include funding or programmatic changes related to the pilot.

Background

In this section, we provide background on the CalWORKs program, including current federal and state program rules and requirements. As described in the next section, California and other states participating in the federal pilot will be exempt from many of these federal rules and requirements for the duration of the pilot (however, absent any federal changes, these rules and requirements will remain in place for non-pilot states).

CalWORKs Provides Cash Assistance and Supportive Services to Low-Income Families. CalWORKs was created in 1997 in response to 1996 federal welfare reform legislation that created the federal TANF program. CalWORKs is administered by counties and overseen by the California Department of Social Services (CDSS). In 2023-24, about 890,000 individuals in about 346,000 households participated in CalWORKs (making up over 30 percent of all TANF recipients nationwide).

Federal, State, and County Governments Share Program Costs. Federal law allows for some state flexibility in the use of federal TANF funds. California receives $3.7 billion annually for its TANF block grant (which does not change year to year), over $2 billion of which goes to CalWORKs (the remainder helps fund aid for some low-income college students and various other human services programs). To receive its annual TANF block grant, the state must spend a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) amount from state and local funds to provide services for families eligible for CalWORKs. This MOE amount is approximately $2.9 billion annually (which can be spent directly on CalWORKs or other programs that meet federal requirements. The MOE amount also generally remains fixed from year to year, with some exceptions). State and federal CalWORKs funding generally is allocated to counties, all of which directly serve eligible families.

Families and Individuals Must Meet Certain Criteria to Be Eligible for CalWORKs. States have some flexibility in setting eligibility requirements. To qualify for CalWORKs, families generally must earn less than about 80 percent of the federal poverty level, equivalent to about $1,700 per month for a family of three in 2024. Families also generally can only have limited assets (such as property or savings). Only families with children under age 18 can qualify for CalWORKs, with limited exceptions. Eligibility status can also vary by individual within a family. Family members may be ineligible for CalWORKs for several reasons. Most commonly, people are ineligible for CalWORKs because they (1) exceeded the lifetime limit on aid for adults (currently 60 months), (2) currently are sanctioned for not meeting some program requirements, or (3) receive Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) benefits (state law prohibits individuals from receiving both SSI/SSP and CalWORKs). Additionally, individuals may be ineligible due to their immigration status. Undocumented immigrants, as well as most immigrants with legal status who have lived in the United States for fewer than five years, are ineligible for CalWORKs. Generally, if an individual is ineligible for CalWORKs, other members of his or her family (including children) who themselves meet eligibility requirements can receive aid.

Grants Based on Number of Eligible Family Members, Not Overall Family Size. Monthly CalWORKs grant amounts are set according to the size of the assistance unit (AU). The size of the AU is the number of CalWORKs-eligible people in the household. Grant amounts are adjusted based on AU size—larger AUs are eligible to receive a larger grant amount—to account for the increased financial needs of larger families. As of December 2023 (when the most recent analysis was conducted), about 40 percent of CalWORKs cases included everyone in the family (and thus the AU size and the family size were the same). In the remaining 60 percent of cases, though, one or more people in the family were not eligible for CalWORKs and therefore the AU size was smaller than the family size (many of these cases include zero adults). Child only cases made up over 40 percent of all CalWORKs cases in 2023-24, including those in which the AU and family size were the same.

Grants Also Vary Based on Other Factors, Such as Geography and Income. Families living in high-cost coastal counties such as Los Angeles and San Francisco receive grants about 5 percent higher than similar families living in inland counties such as Fresno and Shasta. Additionally, grant sizes generally decrease as family income increases. In 2024-25, the administration estimates the average CalWORKs grant amount to be $1,001 per month across all family sizes and income levels. CalWORKs recipients are often also eligible to receive supportive services and resources, such as subsidized child care, employment training, mental health counseling, and housing assistance.

Many Adult Participants Must Meet Participation Requirements. Under current federal and state program rules (described in further detail below), most adults receiving CalWORKs must be employed or participate in specified activities intended to eventually lead to employment, known as welfare-to-work (WTW) activities for 20 to 35 hours per week (depending on family makeup). If adult participants do not meet the WTW requirements, they may be sanctioned, leading to grant reductions.

The Federal Government Has Historically Measured Program Success Through Work Participation Rate (WPR) Requirements. A state’s WPR is the percentage of adult TANF participants engaging in required WTW activities. The WPR has historically been the only federal measure of state TANF program performance (however, as mentioned above and described in more detail below, California and other pilot states will test alternative performance measures to the WPR). To meet WPR requirements, at least 50 percent of all families and 90 percent of two-parent families receiving TANF in a state (with work-eligible adults in the family) must be working or engaged in WTW activities for the requisite number of hours per week. Federal law outlines specific WTW activities that count toward the WPR requirements.

States May Incur Financial Penalties for Failing to Meet WPR Requirements. Federal financial penalties for failing to meet the WPR requirements can start at 5 percent of a state’s annual TANF grant and can increase (up to a maximum penalty of 21 percent) each successive year a state fails to meet the requirements. States generally can appeal penalties (for example, by claiming reasonable cause for failure to meet the WPR requirements). A state that meets the all families requirement (50 percent participation) but not the two-parent requirement (90 percent participation) might incur a smaller penalty than if it had failed to meet both requirements. (California and other pilot states will not face WPR-related penalties during the pilot period unless removed from the pilot, as described below.)

Meeting All WPR Requirements Has Been Challenging for California. As shown in Figure 1 below, California failed to meet at least one WPR requirement annually between 2007-08 and 2021-22 (California has submitted appeals for all penalties incurred to date and, to date, has not paid a penalty). California state law currently stipulates that if the state fails to meet the WPR requirement(s) and incurs a federal penalty, counties that did not meet the WPR requirement(s) locally incur a portion of the penalty’s cost (given California’s appeals, counties have not incurred a penalty to date).

Figure 1

California’s Previous Penalties and Appeals

(In Millions)

|

Federal Fiscal Year |

All Families WPR Requirement |

Two‑Parent WPR Requirement |

Original Base Penalty |

Current Assessed Penaltiesa |

Revised Estimated Penalty Exposureb |

|

2007‑08 |

Failed |

Met |

$48 |

— |

— |

|

2008‑09 |

Failed |

Met |

114 |

— |

— |

|

2009‑10 |

Failed |

Met |

180 |

— |

— |

|

2010‑11 |

Failed |

Met |

246 |

— |

— |

|

2011‑12 |

Failed |

Failed |

312 |

$165 |

$12 |

|

2012‑13 |

Failed |

Failed |

378 |

231 |

6 |

|

2013‑14 |

Failed |

Failed |

444 |

297 |

5 |

|

2014‑15 |

Met |

Failed |

93 |

66 |

13 |

|

2015‑16c |

Met |

Failed |

9 |

9 |

5 |

|

2016‑17c |

Met |

Failed |

14 |

14 |

13 |

|

2017‑18c |

Met |

Failed |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

2018‑19c |

Met |

Failed |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

2019‑20 |

Met |

Failed |

5 |

— |

— |

|

2020‑21 |

Met |

Failed |

11 |

— |

— |

|

2021‑22 |

Met |

Failed |

To Be Determined |

To Be Determined |

To Be Determined |

|

Totals |

$1862 |

$791 |

$64 |

||

|

aReflects most recent correspondence from Administration for Children and Families. bIncludes penalty relief provided for “significant progress” towards WPR target, and the impact of a penalty reduction in any given year on the penalty calculation/amount in following years. cPenalties in dispute as of January 2025. |

|||||

|

Note: California has appealed all assessed penalties to date. Data on 2022‑23 and beyond are not yet available. |

|||||

|

WPR = work participation rate. |

|||||

Federal WTW Requirements Focus on “Core” WTW Activities. As mentioned, current federal TANF rules require most adult TANF recipients to participate in WTW activities for a certain number of hours each week (outside of the new federal pilot). Federal rules also dictate how many of those hours must be spent on work or work-like activities, which are called core WTW activities. To fulfill federal requirements (and to be counted as meeting the WTW requirements in a state’s WPR), most individuals must spend the majority of their WTW hours on core activities. Core activities include, but are not limited to, employment, community service, and job search activities. Noncore activities include certain job skills training and educational activities.

States Have Some Flexibility in the Types of WTW Activities and Services Provided. In 2012, the California Legislature modified state rules governing allowable WTW activities. The modified WTW rules provide greater flexibility for CalWORKs participants to receive services aligned with addressing barriers to employment, such as mental health issues. California’s current rules provide more flexibility than the current federal rules on the types of activities that can be counted towards participation. Additionally, California does not dictate how many hours an individual must spend on core activities. Therefore, some CalWORKs participants have historically met their participation requirements through mostly noncore activities, such as barrier removal or education. In these cases, participants are meeting their work participation requirements to stay in compliance with state rules (and therefore are not at risk of a sanction), but would not be meeting the federal participation requirements. Generally, individuals who spent more time on noncore activities than is allowable under federal rules were included in the state’s work-eligible caseload (the WPR’s denominator), but were excluded from the number of cases meeting the federal WTW requirements (the WPR’s numerator). This has the effect of lowering the state’s WPR in the short term. (As described below, the pilot provides participating states with further flexibility in setting program requirements and defining WTW activities.)

California Collects Data on Additional Performance Measures Alongside WPR Through the CalWORKs Outcomes and Accountability Review (Cal-OAR). California established Cal-OAR, a local program management system, through the 2017-18 Budget Act. Cal-OAR is designed to facilitate improvement of county CalWORKs programs through the collection, analysis, and dissemination of program outcomes and best practices. The system, implemented in July 2021 (after a COVID-19-related delay in 2020-21), includes 26 performance measures outlined in Figure 2. A workgroup of CDSS and legislative staff, county representatives, the County Welfare Directors Association of California, CalWORKs recipients, and other relevant entities selected the performance measures to align with the programmatic goals of supporting both self-sufficiency amongst work-eligible Californians and improving low-income child and family well-being.

Figure 2

CalWORKs Outcomes and Accountability Review Performance Measures

|

Economic Measures |

Participation Measures |

|

Current and former participant employment rates |

WTW engagement rate |

|

Subsidized to unsubsidized employment rate |

Sanction rate |

|

Wage progression (6 and 12 months after exit) |

Sanction resolution rate |

|

Rate of exits with earnings |

Orientation attendance rate |

|

Rate of program re‑entries (including after exit with earnings) |

Appraisal completion rate |

|

Rate of re‑entry after exit with earnings |

Time from appraisal to first WTW activity |

|

Intergenerational enrollment rate |

First WTW activity attendance rate |

|

Education Measures |

Access to Supplemental Services |

|

Education and skills development rate |

Homeless Assistance and Housing Support Program access rates |

|

Education and skills development activity utilization rate |

Ancillary services access rate |

|

Child care access rate |

Transportation provision rate |

|

Improved literacy, basic skills, and English language acquisition rate |

Home Visiting to WTW transition rate |

|

Community college progress rate |

Family Stabilization to WTW transition rate |

|

Educational completion rate |

|

|

WTW = Welfare‑to‑Work. |

|

Cal-OAR Also Aims to Assist Counties in Assessing and Improving Local CalWORKs Programs. Beginning July 2021 (with the implementation of Cal-OAR), counties were required under state law to participate in the Cal-OAR continuous quality improvement (Cal-CQI) process. The Cal-CQI process occurs over the course of five-year cycles, the first of which is July 1, 2021 through June 30, 2026. Through the Cal-CQI process, each county must:

Conduct a self-assessment of its CalWORKs program, aimed at assessing how the program is currently performing along the Cal-OAR metrics (all counties have completed this step in the current cycle. These assessments are available on the CDSS website).

Develop a system improvement plan, aimed at leveraging the self-assessment findings to set goals for local program improvement along certain locally selected Cal-OAR metrics. (As of February 2025, most counties have completed this step in the current cycle. These plans are available on the CDSS website.)

Conduct peer review sessions, aimed at sharing local best practices and brainstorming solutions to challenges.

Submit two progress reports on local program improvement efforts (in the current cycle, most counties must submit the first progress report in 2025).

State Recently Made Augmentations and Reductions to CalWORKs. We provide an overview of the most notable changes made to CalWORKs in the past five budgets (which include an ongoing grant increase, an increase to the adult lifetime aid limit, and increases to the earned income disregard for applicants and participants, among other changes) in our recent post. Additionally, the 2024-25 spending plan enacted four CalWORKs reductions (totaling $146 million in 2024-25) in the areas of intensive case management, expanded subsidized employment, mental health and substance abuse services, and the home visiting program (HVP). The reductions were intended to help solve the budget problem and to generally more closely align funds to actual utilization and avoid adverse impacts for parents and families served (we provide more information on these reductions in our recent post).

Federal TANF Work and Family Well-Being Pilot

The federal Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA) authorized a five-state pilot project to test alternative performance measures to the WPR—largely focused on long-term employment outcomes and family well-being—in the TANF program for six years. According to the federal government, the pilot project aims to build new evidence on whether TANF programs being accountable for work and well-being outcomes (rather than the WPR) leads to stronger employment outcomes and increased family stability and well-being amongst participants. California applied to participate in the pilot in late 2024, as was proposed by the administration and agreed upon by the Legislature in the June 2024 budget package. In November 2024, the federal Administration for Children and Families (ACF) notified CDSS that California was selected to participate in the pilot alongside Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, and Ohio. Of the five states selected to participate, California has the largest TANF program. (Of the selected states, Ohio has the second largest TANF program, with about 40,000 participating families in 2023. Kentucky’s TANF program is the smallest of the selected states, with about 12,000 participating families in 2023.)

Key Components of the Pilot

Participating States Will Utilize Alternative Performance Measures to WPR. During the pilot, participating states will not be required to meet WPR requirements. Instead, we understand performance of these states’ TANF programs will be measured by the following four metrics:

The percentage of work-eligible individuals employed six months after program exit.

The earning levels of those individuals six and 12 months after program exit.

Whole family income levels during and after program participation, including employment earnings; tax credits; child support payments; and other income supports or benefits, including SSI/SSP and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program assistance (CalFresh in California).

Two state-selected family stability and well-being performance measures (which could include, but are not limited to, job access, quality, or security; success of barrier remediation; employment skills gain; poverty reduction; health insurance or behavioral health access; access to child care and early education; educational outcomes; or housing stability). (We describe what we understand was included in the administration’s pilot application surrounding the state-selected measures in further detail below.)

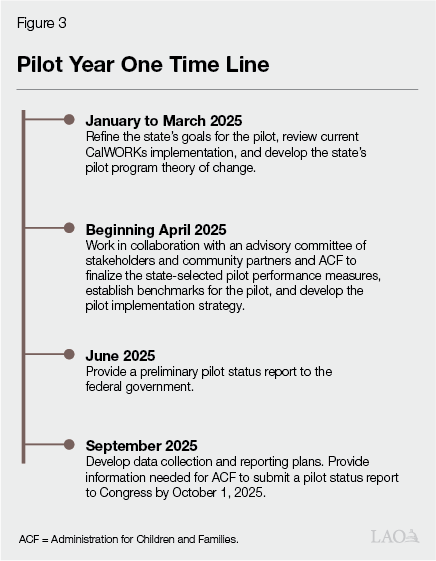

In First Year, Participating States Will Establish Benchmarks, Negotiate Targets, and Develop Pilot Implementation Plan. The pilot will be in effect for six federal fiscal years, beginning October 1, 2024. Figure 3 describes the administration’s anticipated time line for year one (October 1, 2024 through September 30, 2025), as we understand it.

Participating States Will Track and Report on New Measures in Pilot Years Two Through Six. From October 1, 2025 through September 30, 2030, we understand states will collect data and report to ACF on the newly established program performance measures, as described further below. We understand participating states could be removed from the pilot for failing to meet the benchmarks identified in year one. Removed states would again be subject to the same WPR requirements and potential penalties as non-pilot states going forward.

ACF Will Leverage Existing Administrative Data Sources Where Possible for Pilot Performance Tracking and Measurement. It is our understanding that to determine the percentage of work-eligible participants employed six months after exiting the program and the earning levels of these individuals (six and 12 months after program exit), pilot states will submit participant information to ACF, which will then calculate these metrics on the states’ behalf. ACF also indicated it will use existing administrative data and publicly available data sets to calculate whole family income levels on behalf of pilot states. We understand CDSS is not currently aware of additional reporting that will be required from California for the calculation of these metrics, but that CDSS anticipates receiving further guidance from ACF in the coming months.

Participating States Encouraged to Innovate in Delivery of Employment, Training, and Engagement Opportunities for TANF Participants. The ACF’s request for pilot applications (released in late 2024) indicated the federal government was interested in state pilot designs that would create innovative employment and training opportunities for TANF participants aimed at improving employment, earnings, stability, and well-being outcomes. ACF indicated the flexibilities provided through the pilot (via the alleviation of WPR requirements) were designed to encourage participating states to tailor employment, training, and other engagement activities to the needs of TANF families and to help ensure participating families have access to customized supports and services (which, according to ACF, can result in better employment and family well-being outcomes).

Federal Government Will Conduct Pilot Implementation and Outcomes Study. It is our understanding that pilot states will be required to participate in a federally funded pilot implementation and outcomes study, which will be designed by a federal third-party contractor in consultation with the pilot states (the timing of the study is not known at this time). We understand ACF will provide technical assistance to support states’ participation in the study. Pilot states will not receive additional federal funds to conduct independent pilot program evaluations and if states opt to conduct their own evaluation activities, they will be expected by ACF to coordinate these activities with and fully participate in the federal study.

California’s Pilot Application

June 2024 Budget Package Required CDSS to Apply for Pilot. As mentioned above, the 2024-25 Budget Act required CDSS, after consulting with stakeholders, to apply to participate in the pilot program (application for the pilot was first proposed in the Governor’s January and May 2024 budget proposals). In late 2024, CDSS hosted listening sessions with various stakeholders, including county representatives, legislative staff, and participant advocates to inform California’s pilot application.

2024-25 Budget Act Also Included Other Pilot-Related Actions. The June 2024 budget package also stated the Legislature’s intent to continue to reimagine CalWORKs; authorized CDSS to consider certain program changes in its pilot application, such as repealing the county share of the federal WPR penalty and aligning sanctions with minimum federal requirements; required CDSS to report to the Legislature by January 10, 2025 with necessary statutory changes and comprehensive cost estimates to implement any policy changes as part of the pilot program; and allowed the Department of Finance to increase the CDSS budget for state operations (with notification to the Legislature) by up to $2.4 million in 2024-25 for associated costs if California was selected to participate in the pilot. We understand the administration intends to request this funding in 2024-25 to support data reporting and analysis functions for the pilot.

Application Suggested Participation Would Allow State to Assess Impacts of Cal-OAR Framework. In the state’s pilot application, CDSS indicated that through pilot participation, California could assess the usage of Cal-OAR and the Cal-OAR CQI process as a performance measurement framework and a route to increased long-term employment and program effectiveness without the impediment of WPR requirements. It is our understanding that California’s pilot application suggested using the 26 Cal-OAR measures as the state’s pilot outcome measures (in addition to the four performance measures required across all pilot states, as described above, most of which are also captured in Cal-OAR). However, the state’s application indicated it may be necessary to identify a narrower subset of measures within Cal-OAR for the pilot. As mentioned above, we understand from the administration that CDSS will begin working with an advisory committee and ACF to finalize the state-selected pilot performance measures and establish benchmarks beginning in April 2025.

Application Also Suggested Using CalWORKs Take-Up Rate as Outcome Measure. The CalWORKs take-up rate is the percentage of eligible individuals who are actually enrolled in the program (our office previously published a series of posts on the CalWORKs take-up rate). In California’s pilot application, CDSS suggested using the CalWORKs take-up rate as another outcome measure for the state’s pilot program (in addition to the 26 Cal-OAR measures and four federally required measures). The administration indicated California would use the CalWORKs take-up rate, alongside administrative data from other safety net programs like CalFresh and Medi-Cal, to identify and test outreach strategies for eligible but not enrolled individuals, including in certain communities with lower rates of participation. The administration also indicated it would explore the use of administrative data to reduce barriers to enrollment. According to the state’s pilot application, both efforts would aim to increase CalWORKs take-up, helping more families to achieve long-term economic and well-being goals.

Presented Potential Opportunities to Center Family Engagement, Reduce Administrative Burden, and Increase Participation. In the state’s pilot application, CDSS indicated California’s pilot approach would leverage flexibilities offered under the pilot to consider interventions that center participant engagement in CalWORKs (such as, for example, activities that aim to promote long-term employment and family well-being), aim to reduce administrative burden on participants and county staff, and support implementation at the local level. According to CDSS, these interventions would complement the current array of services in CalWORKs and could include:

Revising sanction policies and mandatory participant activities, such as intake appraisals currently conducted using the Online CalWORKs Appraisal Tool.

Tailoring WTW hourly requirements and activities to families’ unique needs.

Streamlining the application and redetermination processes.

Making program information and notices more easily accessible.

Outlined How CDSS Intends to Support Counties in Implementation. The state’s application emphasized the importance of providing counties with training and technical assistance for successful pilot implementation. CDSS indicated it would host a community of practice to facilitate sharing of challenges and successes between counties and would consider a process to provide counties with increased support on engaging families throughout the pilot.

Administration’s Report on Pilot Policy Options

Recent Report From CDSS Outlines Policy Options and Potential Fiscal Impacts. As mentioned above, the June 2024 budget package required CDSS to report to the Legislature in January 2025 with necessary statutory changes and comprehensive cost estimates to implement any policy changes as part of the pilot program. The policy options and associated cost estimates included in the CDSS report are described in Figure 4. CDSS indicated the policy options (and associated costs) outlined in the report should not be considered pilot proposals from the administration, but rather potential options to be considered (which, if desired by the Legislature, could be implemented all together, as stand-alone options, or as some combination of options). The administration indicated additional policy options could be developed in the coming months (for example, via the administration’s work with the pilot advisory committee). It is our understanding that the estimated fiscal impacts provided by the administration should be considered general annual estimates not specific to any particular fiscal year and that fiscal year-specific cost estimates would need to be developed alongside a more formalized proposal.

Figure 4

CDSS Pilot Policy Options and Estimated Costs

General Fund (In Millionsa)

|

Policy Options and Estimated Costs |

CDSS Estimated Cost |

|

|

Initial Yearb |

Ongoing |

|

|

Centering Family Engagement |

||

|

Eliminate non‑compliance sanctions and penalties during first 90 days in CalWORKs |

$1.9 |

$1.7 |

|

Expand allowable WTW activities |

— |

— |

|

Replace fixed hourly work requirements with individualized engagement requirements |

93.5 |

93.5 |

|

Make job club optional as an initial WTW activity |

— |

— |

|

Reducing Administrative Burden |

||

|

Eliminate the WPR penalty passthrough to counties |

— |

— |

|

Replace Online CalWORKs Appraisal Tool with new alternate, streamlined appraisal tool |

$3.9 |

— |

|

Eliminate applicant resource limit |

16.7 |

$30.1 |

|

Eliminate penalty for teens 16 through 18 who fail to attend school regularlyc |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Eliminate consideration of in‑kind income in eligibility determinations |

32.9 |

35.3 |

|

Simplify income reporting requirements |

112.4 |

112.1 |

|

Suspend some current WTW data reporting requirements |

— |

— |

|

Support Local Implementation |

||

|

Train and provide technical assistance to counties on pilot‑related policy and programmatic changes |

$4.0 |

$4.0 |

|

Provide grants to counties to implement program changes |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Provide funding to counties for increased engagement with CalWORKs families |

97.5 |

97.5 |

|

Total Cost of Optionsd |

$365.0 |

$376.4 |

|

County Savings |

||

|

Possible county‑level administrative efficiency savings |

‑$90.4 |

‑$90.4 |

|

aCalifornia’s annual $3.7 billion federal TANF block grant can be used flexibly for the policy options. The TANF block grant is fully allocated within the existing and proposed state budgets. As such, new costs for the CalWORKs program are considered General Fund cost impacts. State General Fund costs may be mitigated to the extent TANF funding is not fully expended in any particular year, or if one of the CalWORKs subaccounts has sufficient revenue available to support CalWORKs assistance costs. No additional federal funds were provided for the pilots. bThe initial year of the pilot aligns with the federal fiscal year (October 2025 to September 2026). As such, if the options above were adopted, some initial year costs may fall in state fiscal year 2024‑25 while others may fall in state fiscal year 2025‑26. cOne‑time automation cost is pending and not included in cost estimate. dTotal cost of policy options, including those supporting local implementation, before any county‑level administrative efficiency savings. |

||

|

CDSS = California Department of Social Services; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; WTW = Welfare‑to‑Work; and WPR = work participation rate. |

||

However, Governor’s Budget Proposal Does Not Include Federal Pilot Participation Costs. It is our understanding that proposals related to the state’s participation in the pilot (including the policy options and costs outlined above in Figure 4) are not included in the Governor’s 2025-26 budget. According to the administration, this is both due to the timing of California’s selection and the administration’s desire to engage with the Legislature on options for implementation.

LAO Assessment

Pilot And California Application Appear Aligned With Legislative Interest in Expanding CalWORKs Goals. As mentioned, California has broadened its CalWORKs goals in recent years to include a focus on long-term employment and family well-being. Overall, the flexibilities offered via the pilot likely align well with this broadened focus for CalWORKs. Based on currently available information on the administration’s anticipated approach to pilot implementation, it appears the Legislature and the administration may have similar goals for how California’s participation in the pilot could be used to further improve long-term employment and family well-being outcomes for CalWORKs participants. The alleviation of WPR requirements and associated potential penalties throughout the pilot will present an opportunity for the state and counties to shift focus towards other desired outcome measures and goals for the CalWORKs program. (However, as discussed in our recent post and below, California was likely to face lower WPR requirements than in previous years beginning in 2025-26 regardless of its participation in the pilot, largely due to the recent federal rebasing of caseload reduction credit calculations.)

Estimates on Potential Costs Appear Reasonable, but Questions Remain. As mentioned, CDSS reported to the Legislature in January 2025 with its cost estimates to implement various policy changes as part of the pilot. While our office is still working to assess the cost estimates (including assumed county administrative savings), the estimates generally appear reasonable at this time. However, questions remain on if and how the policy options and associated costs might interact with each other, if the estimated administrative savings are likely to materialize, how the anticipated implementation schedule of the policy options might impact estimated annual costs, and if other policy options not included in the CDSS report might be considered.

Questions Exist Surrounding Next Steps and Implementation. As mentioned, the administration has not proposed trailer bill or budget bill language related to pilot planning or implementation. However, based on the state’s pilot application and the administration’s cost estimates, it is our understanding that both programmatic changes and discretionary funding will likely be needed to implement the pilot program (in 2025-26 and future years), especially if the Legislature would like to consider implementing any policy changes over the course of the pilot. Therefore, questions remain on the administration’s next steps and what proposals, if any, the Legislature can expect regarding the pilot in May. We outline some of these questions in the following section.

Opportunity for Legislative Oversight. Given our office’s assessment that the 2025-26 budget is roughly balanced, the budget does not have capacity for new augmentations for CalWORKs this budget year without reductions or other solutions elsewhere across the budget. Additionally, as discussed in our recent report, The 2025-26 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, both our office and the administration project significant budget deficits in future years, meaning the Legislature will need to identify additional budget solutions to keep future expenditures balanced with forecasted revenue growth. Therefore, the Legislature could consider using the state’s participation in the pilot as an opportunity to reassess the various components and offerings of the CalWORKs program. In the next section, we describe some key questions the Legislature might consider in this oversight role.

Key Questions

In this section, we outline some key questions the Legislature could ask of the administration as it considers its role in pilot planning, implementation, and oversight.

What Can the Legislature Expect Next? As discussed, CDSS indicated it intends to begin the pilot planning process in the coming months. The Legislature could consider asking the following key questions of the administration:

What next steps does the administration intend to take in pilot planning and implementation?

What are the implementation milestones the administration is tracking and working towards (both from the federal government and as determined at the state level)?

How does the administration plan to involve the Legislature and other stakeholders throughout the planning and implementation process?

What Program Performance Metrics Will California Use in the Pilot? As mentioned, California’s pilot application suggested using the 26 Cal-OAR measures and the CalWORKs take-up rate as the state’s pilot outcome measures (as well as the four federally selected performance measures required across all pilot states). However, pilot outcome measures have not been officially proposed or selected. Questions for the administration on this topic could include:

Has the administration had further conversations with the federal government or stakeholders on the selection of pilot outcome measures or the associated benchmarks and targets?

How does the administration plan to involve stakeholders, including the Legislature, in the selection of the outcome measures?

How will benchmarks and targets along each of the selected measures be determined?

For the four federally required pilot performance measures, what funding, automation updates, or programmatic changes may be needed due to these new reporting requirements?

How will stakeholders, including the Legislature, be kept up-to-date on California’s performance in the pilot?

What Programmatic or Policy Changes Does the Administration Propose Implementing? As mentioned, CDSS indicated in the state’s pilot application that California would utilize flexibilities offered under the pilot to consider interventions that center family engagement, aim to reduce administrative burden on participants and county staff, and support implementation at the local level. However, the administration has not put forward a proposal for pilot-related programmatic or policy changes or included pilot-related funding in its January 2025 budget proposal. Some questions on this topic could include:

Has the administration had conversations with the federal government on the potential policy and programmatic interventions mentioned in the state’s application?

How was the list of policy options and associated fiscal impacts detailed in the January 2025 CDSS report developed? Does the administration plan to put forward any trailer bill or budget bill language surrounding these options? If so, which options does it plan to include in its proposal?

How would the administration recommend the Legislature prioritize the various policy options highlighted in the state’s pilot application and in the January 2025 report from CDSS (especially given the budget constraints mentioned above)?

Would not implementing, or phasing in, some of the changes included in the state’s pilot proposal jeopardize the state’s selection as a participant in the pilot?

How Will the Pilot Be Implemented Locally? As mentioned above, CalWORKs programs and services are largely administered by county human services departments. As such, county staff will largely be responsible for implementing any programmatic changes in CalWORKs throughout the pilot. Some questions the Legislature could consider asking the administration on this topic include:

What training or technical assistance does CDSS anticipate county staff will need for pilot implementation (in year one and beyond)? How does CDSS plan to provide this training or assistance?

What challenges does the administration anticipate county staff or county human services departments may encounter throughout the pilot? How will CDSS help address these challenges?

What impacts might the planned funding reductions to HVP, mental health and substance abuse services, and intensive case management, as well as the projected budget year decrease in employment services funding (described in our recent post), have on local pilot implementation and outcomes?

What feedback has the administration received from counties surrounding possible local administrative costs or savings associated with pilot implementation? How does it intend to get county input on potential costs or savings?

Other Impacts of the FRA on CalWORKs

FRA Also Introduced Other Changes to TANF. In addition to creating the federal TANF pilot, the federal FRA legislation also introduced other changes to the TANF program’s rules and requirements. Key FRA changes to TANF are described below. For further details and analysis, see our prior post.

Introduced New Reporting Requirements on Program Outcomes. Beginning October 1, 2024, each state (even those not in the pilot) must report annually to the federal government on various new TANF program outcomes, mostly focused on educational attainment, job entry and retention, and earnings. It is our understanding that these new reporting requirements apply to pilot states and that some may overlap with pilot-related reporting requirements described above. We understand that California already tracks many of the new program outcomes via Cal-OAR and, as a result, California is likely on track to fulfill these new reporting requirements for the current federal fiscal year. For the educational attainment outcome, CDSS indicated it plans to enter into a data sharing agreement with the California Department of Education to fulfill the reporting requirement.

Established a New Base Year for Caseload Reduction Credit Calculations. States can receive a caseload reduction credit if their overall TANF caseload has declined relative to a specified base year (alternatively, if a state’s caseload increases relative to the base year, it generally would not receive a reduction credit). Caseload reduction credits reduce a state’s WPR requirements. Beginning October 1, 2025, the caseload reduction credit methodology will be rebased. If California were not participating in the pilot (and was instead subject to WPR requirements), this change likely would have resulted in an increase to California’s caseload reduction credits and, therefore, a decrease in the state’s WPR requirements in 2025-26. However, given the alleviation of WPR requirements during the pilot period, our office plans to reassess California’s potential caseload reduction credits and resulting WPR requirements in future years as the pilot draws to a close.

Set New Rules for Programs Like the Work Incentive Nutrition Supplement (WINS) Program. Historically, WINS has used MOE funds to provide certain CalFresh households with additional CalWORKs-funded monthly food benefits of $10. (CalFresh provides nutrition assistance to low-income Californians.) WINS households meet the TANF WTW requirements and, therefore, contribute positively to the state’s WPR calculations. Beginning October 1, 2025, working families enrolled in other programs like CalFresh must receive at least $35 in monthly MOE-funded benefits to be included in state WPR calculations. If California were not participating in the pilot (and was instead subject to WPR requirements), WINS would only help California meet its 2025-26 WPR requirements if monthly benefits were increased from $10 to $35. However, given the alleviation of WPR requirements during the pilot period, our office plans to reassess the potential impacts of this federal policy change as the pilot winds down.

LAO Assessment

Given Pilot Participation, Most Other FRA Changes Will Not Impact CalWORKs for Multiple Years. As mentioned, for the duration of the pilot, California will not be required to meet federal WPR requirements (although, as described above, if the state fails to meet to-be-determined pilot targets, it could be removed from the pilot and again face WPR requirements). As such, the FRA changes to caseload reduction credits and to the federal rules for programs like WINS will likely not be a factor in CalWORKs until after the pilot concludes in 2030. As such (and given limited information around nationwide changes the federal government might consider after the pilot ends), our office will revisit the impacts of the FRA changes on CalWORKs as the pilot winds down and more information is available.

However, Legislature Could Begin Considering Goals for WINS Given Projected Future Deficits. As mentioned, our office estimates that under the Governor’s budget, the budget is currently roughly balanced. However, we project significant budget deficits in future years, meaning budget solutions will likely be needed in the future. Therefore, the Legislature could consider beginning to revisit the goals and outcomes of WINS given the pilot-related alleviation of WPR requirements and the uncertainty surrounding the state’s post-pilot WPR requirements (as a result of the caseload reduction credit change). The Legislature could ask for more information on WINS from the administration, such as:

In recent years, what percentage of total food benefits received by WINS participants were WINS benefits?

Would there be anticipated costs associated with pausing (or subsequently restarting) the WINS program in the future?