Nick Schroeder

June 27, 2025

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 12 (Craft and Maintenance)

The administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 12 (Craft and Maintenance) on the evening of June 23, 2025. Unit 12 consists of employees in various trades including electricians, landscaping and groundskeeping workers, maintenance and repair workers, and painters. Unit 12’s current members are represented by the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE). The current memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the state and IUOE is scheduled to expire June 30, 2026. Our analysis of the current MOU and other labor agreements proposed in the past are available on our State Workforce webpages. If the Legislature rejects the proposed agreement, the current MOU would remain in effect. Although the proposed agreement is presented to the Legislature as a side letter agreement, for purposes of determining if our statutory review is required under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code, we consider the proposed changes to be substantial enough to fundamental aspects of the current MOU to constitute a successor agreement to the current MOU. As such, we prepared this analysis for the Legislature as is required of us under Section 19829.5. The administration has posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website the agreement, a summary of the agreement, and a summary of the administration’s estimates of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effects.

Background

In this section, we provide background on key elements of collective bargaining for Unit 12 that are relevant to the proposed agreement.

Unit 12 in Context of State Workforce

Fifth Largest Bargaining Unit. Unit 12 is the fifth largest of the state’s 21 bargaining units. As of March 2025, rank-and-file and excluded employees associated with Unit 12 totaled more than 15,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, accounting for about 6 percent of the state’s total workforce (about 256,000 FTE). Unit 12 rank-and-file and affiliated excluded employees account for about 3 percent of the state’s General Fund salary and salary-driven benefit costs.

Types of Agreements

Agreements Submitted to Legislature Through Two Different Processes. There are two processes through which a labor agreement can be submitted to the Legislature. The first applies to successor MOUs. Specifically, Section 19829.5 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR “shall provide a memorandum of understanding pursuant to Section 3517.5 to the Legislative Analyst who shall have 10 calendar days from the date the tentative agreement is received to issue a fiscal analysis to the Legislature. […] The memorandum of understanding shall not be subject to legislative determination until either the Legislative Analyst has presented a fiscal analysis of the memorandum of understanding or until 10 calendar days has elapsed since the memorandum of understanding was received by the Legislative Analyst.” The second process applies to addenda (including side letters) to properly ratified MOUs. Specifically, Item 9800 of the budget act directs the Department of Finance (DOF) to determine if an addendum requires legislative approval—pursuant to criteria laid out under Item 9800. DOF then submits the addendum to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), which has up to 30 days to determine if it disagrees with DOF’s determination that an agreement does or does not requires legislative approval.

Proposed Unit 12 Agreement Cast as a Side Letter. The proposed agreement specifies that it is a side letter to the ratified MOU that currently is in effect.

Furloughs

Long History of Using Furloughs to Address State Budget Problems. Furloughs, referred to as Personal Leave Program (PLP) when established through the state’s collective bargaining process, are the most common tool adopted by the state to reduce state employee compensation costs in times of budget problems. Furloughs have been used in nine fiscal years since 1992 (1992-93, 1993-94, 2003-04, 2008-09 through 2012-13, and 2020-21). Typically, a furlough for state employees reduces state employee pay by 4.62 percent in exchange for one day (eight hours) off per month without affecting other elements of compensation (for example, pension and health benefits). In the past, the state has (1) imposed furloughs and negotiated PLP at the bargaining table, (2) established furloughs as mandatory days when employees do not work (state offices would be closed one, two, or three “Furlough Fridays” each month), and (3) allowed employees to have “self-directed” furlough days where employees have discretion to use furlough days as they would vacation or other leave benefits. During the most recent period of furloughs in 2020-21, the state negotiated agreements with all 21 bargaining units to reduce employee compensation costs through PLP 2020 in anticipation of a budget problem in 2020-21 that did not materialize. The pay reduction and number of leave hours received during PLP 2020 varied by bargaining unit, depending on the specific terms of each agreement. Subsequent labor agreements ended PLP 2020. As of December 2024, Unit 12 members have 41,000 unused furlough or PLP leave hours in their leave balances.

Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB)

Rising Cost. OPEB in state employee compensation consists of retiree health benefits. The state has provided some form of health benefits to retired state employees since 1961. During most of this time, the state has paid for these benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis after an employee is retired and receiving the benefit. Since the 1990s, the costs for this benefit have been among the fastest growing costs in the state budget. Between 2000-01 and 2024-25, the state’s inflation-adjusted General Fund pay-as-you-go cost towards these benefits increased by more than 250 percent to $2.8 billion. The largest factors driving these cost increases have been (1) the rapid growth in health premiums and (2) the growing number of people receiving the benefit as more employees retire and people live longer in retirement.

Large Unfunded Liabilities. Because the state had not set aside funds to prefund retiree health benefits for much of the benefit’s existence, a large and growing unfunded liability exists. In the most recent actuarial valuation (as of June 30, 2023) the state’s unfunded liability associated with this benefit for all state employees is estimated to be $85.2 billion.

Progress Towards Prefunding. In 2015-16, the state adopted a policy to establish through the collective bargaining process a prefunding arrangement whereby the state and current employees each pay one-half of the normal cost of the benefit (refer to our 2015 analysis, The 2015-16 Budget: Health Benefits for Retired State Employees for more information). (Under the policy, the state continues to make pay-as-you-go payments for benefits received by retirees.) The money contributed by the state and employees to prefund the benefit is put in a trust fund. Projections at the time indicated that the benefit would be fully funded by 2046. Under the plan, the assets of the trust fund cannot be used to pay for the benefit until 2046 or whenever the benefit is fully funded, whichever comes first. The state and Unit 12 agreed to this prefunding arrangement in 2017 with the fund expected to be fully funded for Unit 12 within 30 years (we note that the state and Unit 12 had agreed to some prefunding of this benefit in 2013, as described in the actuarial valuation as of June 30, 2016). Today, the state and employees represented by Unit 12 each contribute 4.1 percent of pay to prefund the benefit for Unit 12 members. As of June 30, 2023, the state and Unit 12 have set aside $328.7 million in assets to prefund the benefit and the unfunded liability associated with Unit 12 is $2.8 billion. The most recent actuarial valuation of Unit 12 retiree health benefits (as of June 30, 2023) estimates that the Unit 12 funding plan is on track to fully fund Unit 12 retiree health benefits by 2047.

Proposed Agreement

In this section, we summarize the major provisions of the proposed agreement.

Extend Term of Current MOU. The current MOU is scheduled to be in effect through June 30, 2026. The proposed agreement would extend the term of the MOU an additional year, through June 30, 2027.

Change Scheduled Top Step Pay Increase to General Salary Increase (GSI). Under the current MOU, Unit 12 members at the top step of their salary range are scheduled to receive a 4 percent pay increase on July 1, 2025. The proposed agreement would replace the scheduled top step increase with a 3 percent GSI. While a top step increase applies only to employees at the top step of their salary range, a GSI applies to all members of the bargaining unit. Accordingly, while the proposed agreement provides a lower pay increase than the current MOU, it provides the pay increase to more Unit 12 members.

PLP 2025. The agreement would establish PLP 2025 for full-time and part-time employees represented by Unit 12 in 2025-26 and 2026-27. During PLP 2025, Unit 12 members’ pay would be reduced by 3 percent in exchange for five hours of PLP 2025 leave credit each month. After accounting for the 3 percent GSI provided by the agreement, the net effect of PLP 2025 would be to essentially hold employees’ take-home pay flat relative to current levels. The agreement specifies that employees would be given “maximum discretion” to use PLP 2025 leave credits; however, “whenever feasible, PLP 2025 should be used in the pay period it was earned.” PLP 2025 leave would be requested and used by employees in the same manner as vacation or annual leave. The agreement specifies that PLP 2025 may be cashed out upon separation from state service. Salary rates, salary ranges, pension benefits, and health benefits would not be affected during PLP 2025. In addition to the five hours of PLP 2025 leave credit received each month, the agreement would provide employees eight hours of PLP 2025 leave on June 1, 2027 on a one-time basis.

Suspension of Employer and Employee Contributions to Prefund OPEB. Under the current MOU, the state and Unit 12 members each are scheduled to contribute one-half of the normal cost—calculated to be 4.1 percent of pay—to prefund retiree health benefits in 2025-26. Combined, the Unit 12 OPEB funding plan assumes that the full normal cost—calculated to be 8.2 percent of pay—is contributed to prefund retiree health benefits for Unit 12 members each year. The agreement would suspend both the employer and employee contributions—meaning no money would be going towards prefunding the benefit—for 2025-26 and 2026-27. The agreement creates a goal that the state and employees would again each contribute one-half of the normal cost by July 1, 2029. The agreement would phase this policy into effect with the state and employees each contributing (1) 1.4 percent of pay, for a total of 2.8 percent of pay, in 2027-28; (2) 2.7 percent of pay, for a total of 5.4 percent of pay, in 2028-29; (3) 4.1 percent of pay, for a total of 8.2 percent of pay, in 2029-30; and (4) an adjustable percentage of pay—not to be adjusted by greater than 0.5 percent of pay in any year—beginning in 2030-31.

Increased State Contributions to Health Benefits. The state contributes a flat dollar amount to Unit 12 members’ health benefits. The proposed agreement would adjust the amount of money the state pays towards these benefits to maintain a state contribution equivalent to the 80/80 formula, whereby the state pays an amount equal to 80 percent of the weighted average of the basic health plan premiums for the employee and any eligible dependents. The proposed agreement would adjust the state’s contributions to maintain this share of premium costs when premiums adjust in January 2027.

Freeze Employee Contributions Towards Pension Benefits. Beginning July 1, 2026, the current MOU allows for employee contributions towards their retirement benefits to increase in the event that California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) determines that the normal cost of the benefit increases by more than 1 percent of pay. The proposed agreement would suspend this provision, meaning that employee contributions to CalPERS would not increase through June 30, 2027.

No Furloughs. The proposed agreement specifies that the state would not implement a furlough program or additional PLP during PLP 2025.

Continuous Appropriation. For the current MOU, the state and IUOE presented as part of the ratification legislation, language to appropriate funds to maintain employee salaries and benefits in the event of a late budget. The proposed agreement specifies that the state and IUOE will present language to the Legislature as part of the vehicle for legislative ratification to extend this appropriation authority through June 30, 2027.

LAO Comments

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect

Reduced State Costs Through Term of Agreement. Figure 1 shows the administration’s estimated fiscal effects of the proposed agreement. As the figure shows, PLP 2025 and the suspension of OPEB prefunding would result in the state’s Unit 12 compensation costs to be lower than present levels through 2026-27. These savings would help address the immediate budget problem.

Figure 1

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect of Proposed Unit 12 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

2028‑29 |

||||||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

||||

|

General Salary Increase |

$14.3 |

$39.6 |

$14.3 |

$39.6 |

$14.3 |

$39.6 |

$14.3 |

$39.6 |

|||

|

Health Benefits |

— |

— |

2.8 |

7.8 |

4.8 |

13.4 |

4.8 |

13.4 |

|||

|

Personal Leave Program 2025 |

‑14.2 |

‑39.6 |

‑14.2 |

‑39.6 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|||

|

Suspension of OPEB Prefundinga |

‑10.9 |

‑30.4 |

‑10.9 |

‑30.4 |

‑7.2 |

‑20.0 |

‑3.7 |

‑10.4 |

|||

|

Extension of Terms to Excluded Employeesb |

‑2.3 |

‑7.3 |

‑2.3 |

‑7.3 |

2.2 |

6.9 |

3.0 |

9.5 |

|||

|

Totals |

‑$13.2 |

‑$37.7 |

‑$10.4 |

‑$29.9 |

$14.1 |

$39.9 |

$18.4 |

$52.0 |

|||

|

aState General Fund retiree health prefunding costs are paid using funds required to be expended under Proposition 2 (2014). bThis is an indirect cost that would result from the agreement being ratified. |

|||||||||||

|

OPEB = Other Post‑Employment Benefits. |

|||||||||||

Long Term, Agreement Would Increase Costs. While the agreement would reduce state costs in the short term, it would lead to higher costs in the future. Moreover, as we discuss in greater detail below, the agreement would lead to growth in unfunded liabilities, potentially contributing to future budget problems.

Type of Agreement

Side Letter or Successor MOU? The administration characterizes the proposed agreement as a side setter to the current MOU. We consider the agreement to be a successor MOU, meaning it is subject to the Legislative Analyst’s Office’s review process established under Section 19829.5 rather than the JLBC review process under Item 9800. While “side letters,” “MOU addenda,” and “MOUs” are all rather amorphous terms, the Public Employment Relations Board (PERB) laid out its definition of a side letter in a 2011 PERB decision. In that decision, PERB defines a side letter to mean “an agreement between an employer and union that typically: (1) modifies, clarifies or interprets an existing provision in an MOU; or (2) addresses issues of interest to the parties that are not otherwise covered by the MOU.” In our opinion, the changes to existing provisions of the current MOU under the proposed agreement would alter fundamental aspects of the current MOU in a manner more significant than mere modifications, clarifications, or interpretations. Specifically, the agreement would (1) extend the term of the current MOU by an additional year, (2) revise the scheduled pay increase in such a way as to reduce the magnitude of the pay increase while increasing the number of employees who would receive the pay increase, and (3) make significant policy changes to the state’s plan to fully fund Unit 12 retiree health benefits. Accordingly, we consider the proposed agreement to be a proposed successor MOU to the current MOU that maintains most of the provisions of the current MOU. Regardless of what name is given to the agreement, it requires legislative approval before it goes into effect.

Unit 12

Wages Found Lagging Statewide Market for Two Occupations. In its most recent total compensation study for Unit 12, CalHR identified that, statewide, Unit 12 members’ wages (excluding benefits) were (1) above market in the case of stockers and order fillers, painters and construction workers, general maintenance and repair workers, landscaping and groundskeeping workers, and mobile heavy equipment mechanics and (2) below market in the case of electricians and highway maintenance workers.

Total Compensation Found Above Statewide Market for All Occupations. When accounting for wages and benefits, the CalHR compensation study found that Unit 12 members’ total compensation is above statewide market levels. The Unit 12 lead in total compensation ranged from 3 percent above market in the case of highway maintenance workers to 32 percent above market in the case of stockers and order fillers.

Wages Less Competitive Among Local Governments and Certain Regions. CalHR’s compensation study compares wages and total compensation offered by the state with wages and total compensation offered by local government, federal government, and private sector employers across the state as well as within five distinct regions (San Francisco Bay Area Region, San Diego County, Sacramento Region, Los Angeles Region, and All Other Counties). While CalHR found that the state’s compensation for Unit 12 members leads the market statewide across all types of employers, it found that the state’s compensation package is significantly weaker when compared with region-specific local governments. For example, while CalHR found that total compensation for Unit 12 highway maintenance workers was 3 percent above the statewide market rates, CalHR found that Unit 12 highway maintenance workers’ total compensation lagged total compensation of similar employees in the San Francisco Bay Area by 27 percent, in San Diego County by 4 percent, in the Sacramento Region by 4 percent, and the Los Angeles Region by 1 percent. (These lags were more pronounced when comparing wages alone.) About two-thirds of Unit 12 members work in one of these regions where Unit 12 total compensation lagged.

Some Evidence of Recruitment and Retention Challenges. We discuss factors below that suggest there are challenges to keeping Unit 12 positions filled.

Turnover Rate Above State Average. According to CalHR’s most recent compensation study, the statewide average turnover rate across all bargaining unit positions is 7.4 percent. The turnover rate among Unit 12 positions is higher than the statewide average at 8.7 percent. In particular, while retirement rates among Unit 12 members is in line with state averages, the involuntary and voluntary separations are above the state average. This suggests that Unit 12 members are more likely to separate from state service before retirement compared with other state workers.

Declining Years of Service. In 2003, the average Unit 12 member had more than 11 years of state service. Today, the average Unit 12 member has seven years of service.

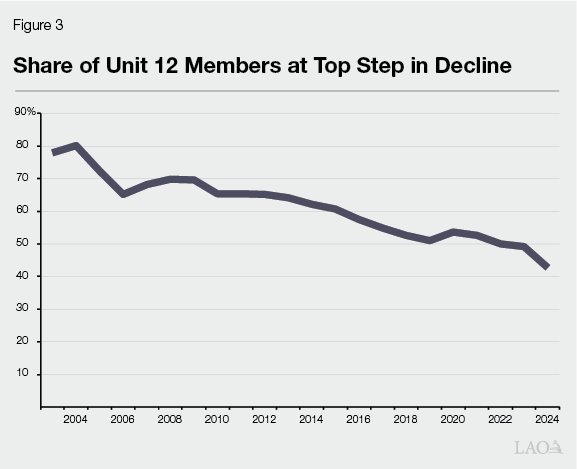

Declining Share of Employees at Top Step. Figure 2 shows that the share of Unit 12 members who are at the top step of their job classification’s pay range has decreased significantly over the past couple of decades and appears to be continuing to decline. This suggests that Unit 12 is becoming less senior.

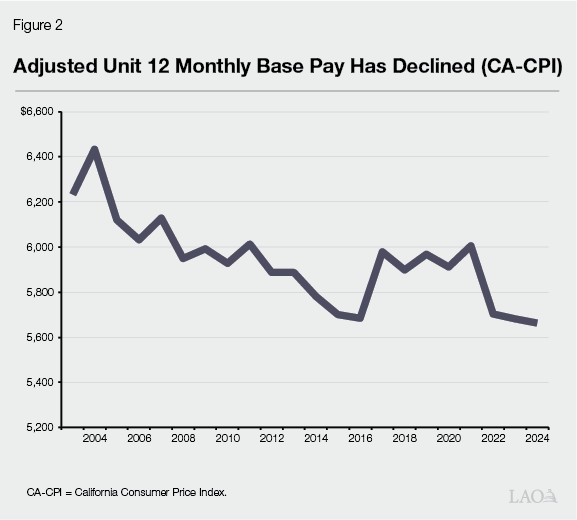

Declining Average Monthly Salary. Figure 3 shows the average monthly salaries of Unit 12 members, adjusted for inflation. The figure shows a significant decline in average adjusted monthly salary for Unit 12 members over the past couple of decades. This likely is less reflective of inflation eroding the purchasing power of Unit 12 salaries and more a reflection of the fact that Unit 12 members today tend to be lower in the salary ranges than they were in the past.

Higher Than Average Vacancy Rates. Over the past five years, Unit 12 positions have had a vacancy rate that is about 5 percentage points higher than the statewide vacancy rate across all civil service classifications. In May 2025, 22 percent of Unit 2 positions were vacant compared with 17 percent of positions statewide. (The higher vacancy rate likely is not due to a growth in the number of authorized positions as the number of authorized Unit 12 positions grew by about 1.5 percent over the past five years.)

Combined, these factors indicate that there may be recruitment and retention challenges for Unit 12. However, based on the regional findings of the compensation study, these challenges may be concentrated in certain regions of the state.

Effects of PLP

Furloughs a Common, but Imperfect Tool. Although furloughs and PLP are established through different means (imposed versus bargained), the two policies functionally are the same. As such, we generally refer to the two policies as furloughs. As we indicated above, the state has used furloughs extensively in the past three decades in response to budget problems. Furloughs have some clear advantages including that they are administratively easy to implement; they offer immediate and predictable levels of savings; and they do not require a reduction in workforce, allowing the state to immediately “staff up” after the budget problem passes. However, there are some notable trade-offs to relying on furloughs to achieve budgetary savings. These trade-offs include effects on recruitment and growth in long-term liabilities:

Recruitment. Furloughs can make the state a less attractive employer to possible new hires by making the state’s compensation package less competitive compared with compensation offered by other employers and by demonstrating a lack of predictability in the state’s terms of employment.

Long-Term Liabilities. Furloughs result in higher leave balances and retirement unfunded liabilities. Unless employees are able to take more time off, furloughs result in larger unused leave balances. These higher leave balances, in turn, lead to higher costs to the state when employees separate from state service and the state must pay the employee for any unused leave at their final salary level. Retirement liabilities funded as a percentage of pay also grow as a result of furloughs. For example, the state pays a percentage of employees’ pay to fund pension benefits. During a furlough, the state’s contributions towards pension benefits is made as a percentage of the reduced salary. However, the benefit earned by the employee is based on their full (not reduced) salary. Accordingly, during furloughs, the state systematically underfunds its pensions—contributing to larger unfunded liabilities.

Suspension of Employer and Employee OPEB Contributions

Missed Opportunity to Improve OPEB Prefunding Arrangement. We long have been critical of the state’s retiree health prefunding strategy. We have found that establishing a benefit that fundamentally has no bearing on an employee’s salary to be funded as a percentage of pay is overly complicated and creates risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by the target date. In addition, sharing the funding cost with state employees likely strengthens any argument that the benefit is protected under the State Constitution, potentially preventing the Legislature from reducing or modifying the benefit in the future. Instead, we have argued that the state should assume the full responsibility of prefunding the benefit. While we are not at the bargaining table and do not know what issues were discussed, we feel it was a missed opportunity for the parties to not find a solution that simplified the prefunding arrangement while also helping address the current budget problem.

Proposed Agreement Makes Fully Funded Target Date Unlikely. Currently, the full normal cost to prefund Unit 12 retiree health benefits is estimated to equate to 8.2 percent of Unit 12 pay. Under the proposed agreement, no contributions would be made to prefund the benefit for two years and contribution rates would not return to current levels for three years after that. Systematically underfunding the benefit for five years makes reaching the full funding target very unlikely. Moreover, although the agreement would reinstate current contribution levels by July 1, 2029, those levels may not reflect normal cost at that time. While the agreement would allow for the contribution rate to be adjusted, those adjustments would be limited to 0.5 percent per year. This constraint makes it even less likely full funding can be achieved by 2046.

Lower Costs Today in Exchange for Higher Costs Later. Suspending both the employer and employees’ contributions to prefund OPEB reduces costs today but contributes to a significant and growing unfunded liability and creates substantial risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by 2047. Further, it creates a precedent for (1) other bargaining units this year to adopt similar actions and (2) future Governors to see this action as an acceptable trade-off to address future budget problems. To the extent that this action is repeated, whether this year or in future years, the goal to fully fund the benefit will become increasingly elusive. In that case, the state could once again face rapidly growing costs in order to pay this benefit. Moreover, the structure of the funding plan allows the state to use money in the trust fund beginning in 2046, regardless of whether or not the benefit is fully funded. The benefit is on track to be fully funded after 2046. Suspending contributions will delay the full funding date further. A future Legislature and Governor could face pressure to use money from the trust fund as soon as it becomes available, especially to address a budget problem, should one exist in 2046. To the extent that money is drawn from the fund before the benefit is fully funded, the likelihood of the benefit ever becoming fully funded will further diminish. Maintaining regular and full payments to prefund the benefit is the best option to meet the policy goal of fully funding the benefit.

Budget

Three-Party Budget Deal Assumes Savings from State Employee Compensation. The current form of the budget deal between the two houses of the Legislature and the Governor (AB 102, Gabriel) assumes that state employee compensation will be reduced in 2025-26. Control Section 3.90 specifies that “the Legislature finds that the savings will likely be needed to maintain the sound fiscal condition of the state.” The control section establishes an expectation of the Legislature that all state bargaining units will meet and confer in good faith with the administration on or before July 1, 2025 to achieve the assumed level of savings through the collective bargaining process for rank-and-file employees and through existing administrative authority for employees excluded from the collective bargaining process.

Unit 12 Agreement Sets Precedent for Bargaining Units With Active MOUs. Unit 12 is one of 14 bargaining units with MOUs that are scheduled to expire some time after 2025-26. The proposed agreement with Unit 12 is the first concession agreement submitted to the Legislature for one of these bargaining units with active agreements. This agreement could be used as a model for agreements with the other 13 bargaining units with active agreements if they choose to come to the table this year. Further, this agreement could serve as a precedent for any policies that the administration might seek to impose on any of the other bargaining units (whether they have an active MOU or not) should the final budget package grant the administration that authority.