In this report, we (1) provide a high–level overview of the Governor’s 2013–14 higher education budget, (2) examine the Governor‘s concerns about California’s public higher education system, (3) discuss the various components of the Governor’s multiyear budget plan for higher education, and (4) provide an assessment of and alternatives to the Governor’s plan. We discuss various other issues relating to the community colleges, including adult education restructuring, Proposition 39 energy efficiency projects, and payment deferrals in a companion report, The 2013–14 Budget: Proposition 98 Education Analysis.

Governor Proposes $1.4 Billion in Additional General Fund Support for Higher Education. California’s publicly funded higher education system consists of the UC, CSU, CCC, Hastings, and CSAC. As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s budget provides $11.9 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2013–14. This is $1.4 billion (13 percent) more than the revised current–year level. As shown in Figure 2, the bulk of the new funding is for adult education restructuring, base increases at the universities, and a general purpose increase for the community colleges. A portion of the total ongoing General Fund increase is linked with provisions in the 2012–13 budget package that provided $125 million each to UC and CSU if they did not raise student tuition levels.

Figure 1

Higher Education General Fund Supporta

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,504

|

$2,567

|

$2,846

|

$279

|

11%

|

|

California State University

|

2,228

|

2,492

|

2,809

|

317

|

13

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

3,612

|

3,802

|

4,503

|

701

|

18

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

—

|

3

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

1,533

|

1,624

|

1,722

|

98

|

6

|

|

Grand Totals

|

$9,885

|

$10,494

|

$11,890

|

$1,396

|

13%

|

Figure 2

Governor’s Major Higher Education Budget Changesa

Change From Revised 2012–13 Budget to Proposed 2013–14 Budget (In Millions)

|

|

|

|

Provide funding for CCC adult education

|

$300

|

|

Provide 5 percent base increases for UC, CSU, and Hastings College of the Law

|

251

|

|

Fund 2012–13 tuition buyout at UC and CSU

|

250

|

|

Provide general purpose funds to CCC

|

197

|

|

Fund increased Cal Grant costs

|

100

|

|

Allocate funds to CCC for energy efficiency projects

|

50

|

|

Fund new CCC online project

|

17

|

|

Create new CCC apprenticeship program

|

16

|

|

Other adjustments

|

216

|

|

Total Changes

|

$1,396

|

Total Core Funding for Higher Education Would Increase $1.2 Billion. Figure 3 offers a broader perspective on higher education funding in that it shows both General Fund support and support from other core funding sources, including student tuition revenue, federal funds, and local property taxes (for the community colleges). In 2013–14, higher education would receive $18.4 billion in total core funding—reflecting a year–to–year increase of 7 percent.

Figure 3

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net tuitiona

|

$2,558

|

$2,480

|

$2,523

|

$43

|

2%

|

|

General Fundb

|

2,504

|

2,567

|

2,846

|

279

|

11

|

|

Other UC core funds

|

388

|

441

|

385

|

–55

|

–13

|

|

Lottery

|

30

|

37

|

37

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,479)

|

($5,525)

|

($5,792)

|

($267)

|

(5%)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fundb,c

|

$2,228

|

$2,492

|

$2,809

|

$317

|

13%

|

|

Net tuitiona

|

1,982

|

1,919

|

1,919

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

42

|

56

|

56

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($4,252)

|

($4,467)

|

($4,784)

|

($317)

|

(7%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,612

|

$3,802

|

$4,503

|

$701

|

18%

|

|

Local property tax

|

1,974

|

2,256

|

2,171

|

–85

|

–4

|

|

Fees

|

354

|

387

|

387

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

197

|

186

|

186

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,137)

|

($6,631)

|

($7,247)

|

($616)

|

(9%)

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net tuitiona

|

$35

|

$37

|

$36

|

–$1

|

–1%

|

|

General Fundb

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

—

|

3

|

|

Lotteryd

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($44)

|

($46)

|

($46)

|

(—)

|

(–1%)

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$1,471

|

$736

|

$720

|

–$16

|

–2%

|

|

Student Loan Operating Fund

|

62

|

85

|

60

|

–25

|

–29

|

|

TANF funds

|

—

|

804

|

943

|

139

|

17

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,533)

|

($1,624)

|

($1,722)

|

($98)

|

(6%)

|

|

Totalse

|

$16,465

|

$17,213

|

$18,413

|

$1,200

|

7%

|

|

General Fund

|

$9,823

|

$9,606

|

$10,887

|

$1,281

|

13%

|

|

Net tuition/feese

|

3,950

|

3,742

|

3,687

|

–55

|

–1

|

|

Local property tax

|

1,974

|

2,256

|

2,171

|

–85

|

–4

|

|

Other

|

450

|

1,329

|

1,388

|

59

|

4

|

|

Lottery

|

269

|

279

|

279

|

—

|

—

|

Programmatic Funding Per Student Would Increase at All Higher Education Segments. Figure 4 shows another perspective on higher education funding—one that adjusts for enrollment levels and any accounting changes (such as payment deferrals) that otherwise would distort year–to–year programmatic comparisons. This figure focuses on the amount of funding generally available to support operational costs. As shown in Figure 4, increases in programmatic per–student funding range from 4 percent at UC to 10 percent at CCC.

Figure 4

Programmatic Funding Per Studenta

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

$32,483

|

$39,219

|

$41,048

|

$1,829

|

5%

|

|

University of California

|

24,411

|

24,909

|

25,940

|

1,031

|

4

|

|

California State University

|

11,667

|

12,729

|

13,656

|

927

|

7

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

5,349

|

5,447

|

5,969b

|

522

|

10

|

Package Includes Funding Increases for State’s Financial Aid Programs. The Governor’s budget includes Cal Grant funding increases of $60 million in the current year and an additional $100 million in 2013–14. The increased costs result from growth in student participation in the program and shifts in the types of awards for which students qualify (with more students qualifying for grants that cover both tuition and a portion of living costs). Figure 5 shows the number of Cal Grant recipients and total award amounts by segment.

Figure 5

Cal Grant Recipients and Funding by Segment

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Number of Recipients

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

California State University

|

77,485

|

88,645

|

97,426

|

8,781

|

10%

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

76,062

|

80,786

|

87,926

|

7,140

|

9

|

|

University of California

|

57,394

|

60,687

|

64,885

|

4,198

|

7

|

|

Private nonprofit institutions

|

23,798

|

25,483

|

26,840

|

1,357

|

5

|

|

Private for–profit institutions

|

15,220

|

13,278

|

11,542

|

–1,736

|

–13

|

|

Totals

|

249,959

|

268,879

|

288,619

|

19,740

|

7%

|

|

Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

University of California

|

$691

|

$733

|

$782

|

$48

|

7%

|

|

California State University

|

394

|

454

|

509

|

55

|

12

|

|

Private nonprofit institutions

|

219

|

226

|

238

|

12

|

5

|

|

Private for–profit institutions

|

104

|

90

|

66

|

–24

|

–27

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

88

|

91

|

99

|

9

|

10

|

|

Totals

|

$1,496

|

$1,594

|

$1,694

|

$100

|

6%

|

The 2013–14 Governor’s Budget Summary raises several concerns about higher education in California. Specifically, the Governor makes the following claims:

- High–Cost Delivery Model Is Not Sustainable. The Governor describes a higher education cost structure that “continually increases without necessarily adding productivity or value.” He contends that neither the state’s taxpayers nor students and their families can continue to sustain higher education institutions under the current model.

- Universities’ Budget Plans Assume Continued Growth in Costs. The Governor points out that the UC Regents’ and CSU Trustees’ budget plans are predicated on the current high–cost model. They assume continued growth in funding at levels far exceeding projected growth in state revenues and personal income. The Governor deems such plans unrealistic and instead urges the segments to reduce instructional costs, decrease time to degree, and increase graduation rates.

- Enrollment–Based Funding Does Not Promote Innovation and Improvement. The Governor notes that current funding approaches—historically based on enrollment—reinforce the high–cost delivery model and do not focus attention on important outcomes such as student success and efficiency.

- Unavailability of Required Courses Increases Total Costs for State and Students. The Governor asserts that the high–demand courses many students need to meet graduation requirements often are unavailable. As a result, the Governor argues many students take unnecessary units to remain enrolled and take longer to graduate. These factors increase costs for both the state and students.

- Student Outcomes Generally Are Poor. Calling attention to low graduation and transfer rates, the Governor argues that poor student outcomes lead to even greater inefficiencies in the higher education system.

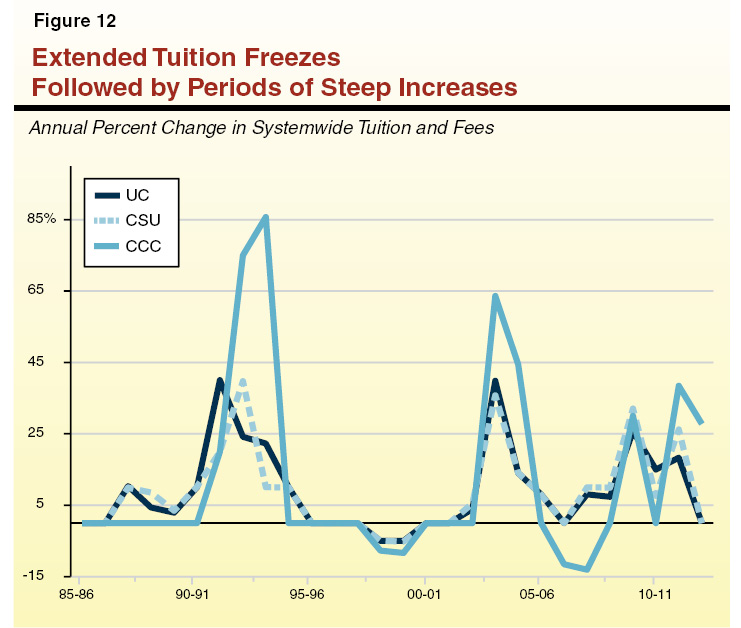

- Rapid Tuition Increases Have Been a Hardship for Some Families. The Governor also notes that recent tuition increases have been difficult for some families that do not qualify for financial aid. At the same time, he acknowledges that despite these tuition increases California has some of the lowest fees in the country. He also points out that the state’s financial aid programs are among the nation’s most generous. As a result of low tuition and high aid levels, the Governor concludes that public postsecondary education remains relatively affordable for California families.

Available data support many of the claims the Governor makes about higher education. For a few of his claims, however, the data are less compelling.

Traditional Delivery Model Is High Cost. The traditional higher education delivery model has a few basic attributes that result in high costs relative to other potential higher education models as well as other industry models. Most importantly, the model is based on a faculty member with an advanced degree teaching a relatively small number of students in a physical setting. These high labor and facility costs are even greater at institutions that focus heavily on research. This is because faculty at these institutions tend to have a lower teaching load compared to institutions that focus less on research. Universities with a very high research focus also have relatively expensive facilities given the additional need for laboratories and state–of–the–art technology. Another factor that contributes to high costs is the very common practice of measuring educational attainment by the amount of time a student spends in school (usually the equivalent of at least four years for a bachelor’s degree and at least two years for an associate degree). This focus on time in school rather than more refined measures of learning perpetuates the traditional higher education cost structure.

University Costs in California Are Particularly High. Not only is the traditional higher education delivery model high cost, but data suggest that costs are particularly high in California. One reason is that a greater share of California’s public university students attend institutions with very high research activity (which tend to be more expensive than other universities). While one–third of university students attend such institutions nationally, 40 percent of California’s university students do. In addition, average spending per student at these UC universities is more than 20 percent higher than at their national counterparts. Several factors could result in higher costs, including lower faculty workload expectations, a more science–oriented mix of academic programs, and high compensation.

Universities’ Budget Plans Predicated on State Maintaining High–Cost Delivery Model. In developing their own budget plans, the segments have included various components related to the high–cost delivery model, including proposed increases in compensation, employee benefit costs, and infrastructure needs. In addition, the universities’ plans propose to reverse some recent budget reductions, for example by reducing student–faculty ratios. Overall, UC’s and CSU’s own budget plans reflect core spending increases of 8 percent and 11 percent, respectively, from the current year. Because both plans assume the state General Fund rather than tuition will cover the entirety of these spending increases, projected increases in state funding are higher—12 percent and 18 percent, respectively. As the Governor points out, these increases are very high relative to the projected 4.5 percent increase in state revenues.

Many Students Accrue More Course Units Than Required for Graduation. Higher education costs also are driven up by excess unit–taking. Standard course requirements for graduation generally total 60 semester units (or 90 quarter units) for an associate degree and 120 semester units (or 180 quarter units) for a bachelor’s degree. Students who accrue units in excess of these requirements generally take longer to graduate, increase state and student costs, and crowd out other students. Excess unit–taking is most prevalent at CCC and CSU. In 2011–12, CCC provided instruction to more than 350,000 students who already had earned 60 or more degree–applicable semester units. Of these students, nearly 95,000 had earned more than 90 units. At CSU, about 90,000 students already had accrued 120 semester units before starting the current academic year. Of these students, about 13,000 had accrued at least 150 units and 2,000 had accrued at least 180 units.

Causes of Excess Unit–Taking Are Varied. Several factors contribute to excess unit–taking. Some of these involve choices students make, either intentionally or because they lack adequate information. Others are related to campus decisions. Unfortunately, due to data limitations, it is not possible to determine the share of excess unit–taking caused by each of these factors.

- Some Students Choose to Take Extra Courses. Some students choose to take courses that are not required for their majors because of interest in the subject or to make themselves more marketable to employers or graduate schools. Others change majors a number of times, repeat courses several times to improve their grades, or remain in school for other reasons after meeting degree requirements.

- Unavailability of Courses Also Has a Role. Students who cannot get into their required courses (due to oversubscribed courses or student scheduling constraints) sometimes substitute other, nonrequired courses to remain eligible for student financial aid, insurance, and other student benefits. As they enroll in substitute courses, these students crowd out others who may need the courses to meet degree requirements.

- Institutional Policies Limit Applicability of Some Units. Course articulation decisions made at the campus or department level also may result in a student accruing excess units. For example, transfer students may find that some of their community college courses are not accepted toward degree requirements by the receiving university.

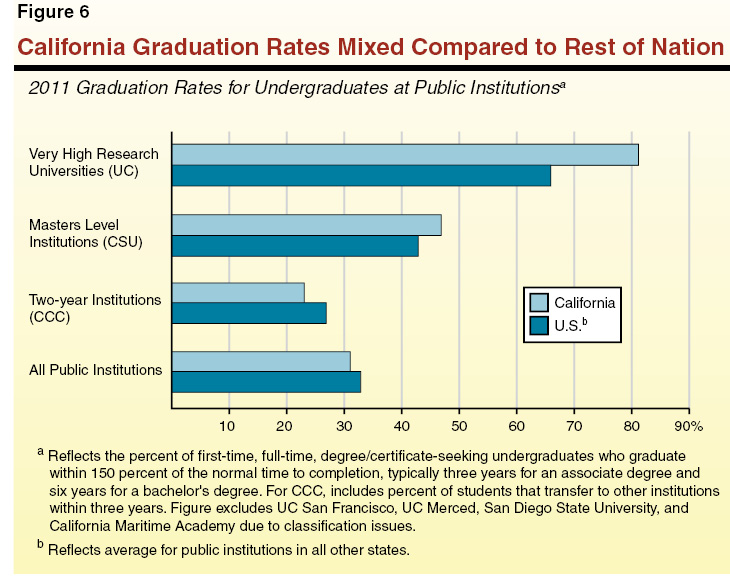

Graduation Rates in California Tell Mixed Story. Student outcomes vary among California’s public higher education segments. (Outcomes also vary significantly among institutions within each segment.) This variation is due in part to the pools of students from which the three segments draw. Currently, the top one–eighth of all graduating high school students are eligible for admission to UC, the top one–third are eligible for admission to CSU, and all persons 18 years or older are eligible to attend CCC. As Figure 6 shows, more than 80 percent of UC students graduate within six years, compared with 47 percent of CSU students. Only 23 percent of CCC students graduate or transfer within three years. These official graduation rates, reported by the U.S. Department of Education, reflect the share of first–time, full–time freshmen who graduate within 150 percent of the normal time needed to complete all program requirements. The graduation rate does not reflect student success broadly at CCC because only a small fraction of CCC students enter as full–time freshmen and some students may not be seeking degrees. Even considering these caveats, graduation rates at CCC are disconcertingly low. Figure 6 also shows that low graduation rates are a national problem, not only a California problem. In fact, graduation rates at UC and CSU are better than the rates for comparable institutions nationally, but the CCC rate is lower than the average of two–year public institutions in all other states.

Spending Per Degree Also High. One way of measuring the productivity of the state’s investment is to consider average annual spending per degree. This measure is affected by both spending and the number of degrees conferred per student. Spending per degree cannot be compared readily across the segments because they (1) offer a different mix of undergraduate and graduate degrees and certificates and (2) do not track undergraduate and graduate instructional spending separately. California’s public segments, however, can be compared with similar institutions nationally. Despite relatively high graduation rates, UC’s average spending per degree ($166,000) is well above that of other universities with very high research activity ($140,000). (This measure is more difficult to interpret for CSU and CCC, as students transfering to CSU and CCC students not seeking degrees both complicate spending–per–degree comparisons.)

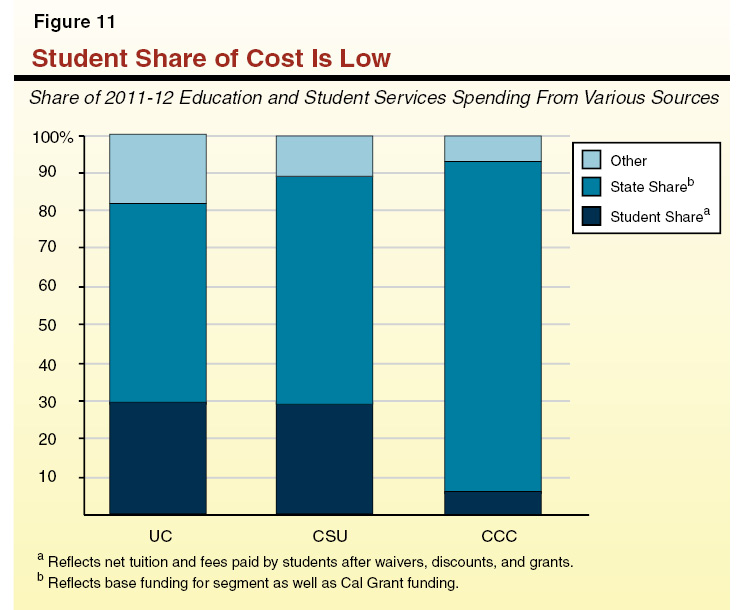

Tuition and Fee Levels in California Are Relatively Low. In addition to focusing on higher education costs and student outcomes, the Governor makes certain claims about tuition and fees in California. Although tuition and fee rates have nearly doubled since 2007–08 at UC and CSU—and more than doubled at CCC—these rates remain comparatively low. The per–unit fee ($46) at the CCC is lowest among the 50 states, undergraduate tuition at CSU ($5,472) is lowest among its 15 public university peers, and undergraduate tuition at UC ($12,192) is slightly above the average of its four comparison public research universities.

California’s Financial Aid Programs Keep College Education Affordable for Financially Needy Students. About half of the students currently enrolled in public colleges and universities receive need–based financial aid specifically to cover full tuition and fee costs. These financial aid awards increase dollar–for–dollar as tuition and fees increase. As a result, spending for both Cal Grants and institutional financial aid has doubled since 2007–08 while the amount actually paid by families has increased far less.

With Low Fees and High Aid, Net Price Has Not Increased Much for Lower Income and Many Middle–Income Families. Figure 7 shows the increase in average net price for families at various income levels from 2008–09 to 2010–11. (Average net price is the total cost of attendance—including tuition, room and board, and other expenses—after subtracting government and institutional grants and scholarships. It is only reported for families receiving federal student aid, including student loans.) While tuition and fees increased between 30 percent and 45 percent during this period, average net price increased 4 percent or less for most families at the universities and 6 percent at the community colleges. For UC students with family income above $110,000 and CSU students with family income above $75,000, net price increased more significantly. Though they are less likely to qualify for need–based aid, these families may receive other types of federal assistance to help cover education costs, including tax credits, tax deductions, and student loans. Nonetheless, families with these higher income levels typically are more likely to bear the costs of tuition increases.

Figure 7

Average Net Price of College

Total Cost of Attendance Less Financial Aid for Full–Time Resident Undergraduatesa

|

Family Income Level

|

Percent of Students

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

Two–Year Change

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$0 – 30,000

|

37%

|

$8,200

|

$8,267

|

$8,545

|

$345

|

4%

|

|

$30,001 – 48,000

|

19

|

9,811

|

9,858

|

9,765

|

–46

|

—

|

|

$48,001 – 75,000

|

18

|

14,403

|

13,939

|

13,526

|

–877

|

–6

|

|

$75,001 – 110,000

|

12

|

20,981

|

21,045

|

21,606

|

625

|

3

|

|

Over $110,000

|

14

|

23,477

|

25,032

|

26,591

|

3,114

|

13

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$0 – 30,000

|

40

|

5,626

|

5,387

|

5,489

|

–137

|

–2

|

|

$30,001 – 48,000

|

20

|

7,795

|

7,856

|

7,916

|

121

|

2

|

|

$48,001 – 75,000

|

17

|

11,245

|

11,377

|

11,654

|

409

|

4

|

|

$75,001 – 110,000

|

11

|

13,954

|

15,468

|

16,036

|

2,082

|

15

|

|

Over $110,000

|

12

|

14,628

|

16,338

|

17,166

|

2,538

|

17

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$0–30,000

|

100b

|

5,721

|

5,983

|

6,058

|

337

|

6

|

Student Debt Also Relatively Low. Another result of low fees and high aid is that average student loan borrowing is relatively low for California students. Recent data show that in 2010–11, about half of graduates from California’s public universities had student loan debt, and the average debt for these students was $16,840. (This is lower than the amount cited in the Governor’s budget, which includes graduates of nonpublic institutions.) By comparison, the average debt for public university graduates nationally—57 percent of whom had student loans—was more than $23,000.

As part of his overall approach to addressing these issues, the Governor proposes a multiyear higher education budget plan. The plan includes annual unallocated base increases for each segment. The Governor links these base increases with an expectation the segments improve their performance in certain areas. The Governor’s plan also makes changes in the funding of debt service at the universities and retirement costs at CSU. The plan includes no enrollment targets for the universities but does include a proposal to change how funding is allocated to the community colleges. The Governor’s plan also earmarks funding for several technology–related initiatives. In addition, his plan includes proposals to freeze tuition levels, cap the number of state–subsidized units, and change two CCC financial aid policies. Below, we describe each of these proposals. In the next section, we evaluate them and, in many cases, offer alternatives.

Proposes Annual Unallocated Base Increases. The main funding component of the Governor’s multiyear higher education budget plan is annual unallocated base General Fund increases for each of the higher education segments over the next four years (2013–14 through 2016–17). For 2013–14, the Governor provides 5 percent base increases of $125 million each for UC and CSU and nearly $200 million for CCC. (The 5 percent base increases for the universities are identical because he bases them both on UC’s budget.) University funding would increase by an additional 5 percent in 2014–15 and 4 percent in each of the following two fiscal years. The Governor also expects CCC funding to grow “significantly” over the next several years.

Desires Better Student Outcomes. The Governor links his proposed base increases with the segments’ success in achieving certain objectives, including improving graduation rates at all segments, increasing the CCC transfer rate, and improving credit and basic skills course completion. To help achieve these objectives, the Governor expects the segments to implement certain strategies, including increasing the availability of courses, using technology to deliver quality education to greater numbers of students in high–demand courses, improving course management and planning, using faculty more effectively, and increasing use of summer sessions.

Combines Funding for Capital and Support Budgets . . . The Governor also proposes to shift a total of about $400 million in general obligation bond debt service for UC, CSU, and Hastings to the segments’ support budgets. Each segment would receive the amount associated with 2013–14 general obligation debt service payments for its capital projects: $201 million for UC, $198 million for CSU, and $1 million for Hastings. Since these funds already were being accounted for in a separate appropriation, the shift does not increase state costs. The Governor also proposes to remove current restrictions specifying how much of the universities’ support budgets are to be used to repay state lease–revenue debt. To ensure that state debt for all projects continues to be repaid, however, the State Controller would automatically transfer the appropriate amounts out of the universities’ budgets each year.

. . . And Removes Legislative Prerogative in Capital Projects Moving Forward. Under the proposal, Department of Finance (DOF) would continue to review and approve capital projects for the universities, but the Legislature would no longer be involved in making these decisions. Projects using state funds would be limited to academic facilities needed for safety, enrollment growth or modernization purposes, as well as infrastructure projects that support academic programs. Though the administration indicates the universities potentially still could request state bond funding for their projects, the Governor also proposes to allow them to pledge General Fund monies to issue their own debt for capital projects.

Allows Universities to Restructure State Bond Debt. The Governor further proposes to allow UC and CSU to restructure existing state lease–revenue debt related to their projects. For example, the state currently has about $2.5 billion in outstanding lease–revenue debt for projects built at UC. In 2013–14, the state will spend about $221 million to service this debt. Under the Governor’s proposal, UC would be granted the authority to repay the state’s bondholders the $2.5 billion owed to them by issuing its own bonds on its own terms.

Limits Future Budget Adjustments for CSU Retirement Costs. Under state law, CSU is required to participate in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). The university system’s annual contribution to CalPERS is determined by multiplying its payroll costs by its employer contribution rate. In 2012–13, for example, CSU had an estimated $2.2 billion in payroll subject to CalPERS, an employer contribution rate of 21 percent (for most of its payroll), and a resulting CalPERS contribution of $463 million. Each year, the state adjusts CSU’s budget (as it does for other state departments) to account for changes in retirement costs due to changes in payroll and employer rates. Starting in 2013–14, the Governor proposes that future adjustments to CSU’s budget for retirement costs be based permanently on 2012–13 payroll costs. According to the administration, this would require CSU to consider full compensation costs for any decision to increase its payroll.

Does Not Include Enrollment Targets for Universities. Figure 8 shows enrollment levels for each of the segments, as reflected in the Governor’s budget, though the administration indicates the information is only for display purposes. Unlike historical budget practice, the administration indicates that it will not set enrollment targets for UC and CSU as part of the multiyear plan. The Governor also does not link any of the annual base augmentations to specified enrollment growth. The administration indicates the universities would have full discretion in determining how many students to serve, including how many additional students, if any, to serve. The Governor proposes to continue to fund community college districts based on enrollment (though he proposes to change the way enrollment is calculated, as discussed below). Despite keeping current–year CCC base funding linked with enrollment, the Governor does not require the community colleges to serve additional students in the budget year with his proposed base augmentation.

Figure 8

Higher Education Enrollment

Resident Full–Time Equivalent Studentsa

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Projected

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

175,505

|

173,690

|

175,040

|

1,350

|

1%

|

|

Graduateb

|

38,258

|

39,013

|

39,013

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

(213,763)

|

(212,703)

|

(214,053)

|

(1,350)

|

(1%)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

302,817

|

294,331

|

294,331

|

—

|

—

|

|

Teacher Credential

|

5,969

|

5,808

|

5,808

|

—

|

—

|

|

Graduatec

|

32,494

|

31,577

|

31,577

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

(341,280)

|

(331,716)

|

(331,716)

|

(—)

|

(—)

|

|

California Community Collegesd

|

1,098,014

|

1,108,116

|

1,108,116

|

—

|

—

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

1,297

|

1,135

|

1,083

|

–52

|

–5%

|

|

Totals

|

1,654,354

|

1,653,670

|

1,654,968

|

1,298

|

—

|

Bases CCC Funding on Course Completions Rather Than Enrollment. The Governor also proposes to change the basis on which community college districts are funded for credit instruction. Currently, the amount of funding a district receives depends largely on the number of students enrolled at “census”—a point defined in CCC regulations as one–fifth into a given academic term (typically the third or fourth week of the semester). If a student drops a course after this date, the college still earns full payment for that student. Beginning in 2013–14, the Governor proposes to add a second CCC census date at the end of each term. Over a five–year period, there would be a gradual shift in the relative weight of these census dates for purposes of calculating district enrollment. By 2017–18, community colleges would be funded exclusively on the number of students still enrolled in their courses at the end of each term. According to DOF, any reduction in a district’s enrollment (apportionment) monies resulting from this policy change would be automatically redirected to that district’s Student Success and Support categorical program, which funds assessment and counseling services. Districts that do not show improvement in course completions after a certain period of time (as defined by the Board of Governors [BOG]) would have this redirected funding swept and reallocated to other colleges. According to the Governor, the purpose of his proposal is to “more appropriately apportion funding by focusing on completion” as well as to provide community colleges with incentives to ensure appropriate student placement and good course management.

Earmarks Funding for Several Online Education and Technology Initiatives. The Governor earmarks $10 million each for UC and CSU to expand the availability of courses through the use of technology. Budget bill language specifies that the funding is for high–demand courses that fill quickly and are required for many different degrees. Under the Governor’s plan, UC and CSU would have discretion in allocating funds within their systems but would be required to prioritize development of new courses that can serve greater numbers of students while providing equal or better learning experiences. The Governor also proposes a new $16.9 million CCC categorical program, a portion of which would be used for a similar online initiative to increase the availability of high–demand courses. The CCC Chancellor’s Office would be required to submit an associated allocation plan to the DOF for approval. The Governor proposes that CCC use some of the remaining increase to purchase a common learning management software system and the rest to expand opportunities for students to earn course credit by examination.

Proposes No Tuition and Fee Increases Over Extended Period. Figure 9 shows tuition and fee levels at each of the segments. The Governor expects the universities to maintain current tuition and fee levels for the next four years. As a result, tuition and fee levels would remain flat for a six–year period (2011–12 through 2016–17). For the community colleges, the Governor also proposes no fee increase in 2013–14 but DOF indicates the administration is silent as to potential fee increases in the future.

Figure 9

Annual Tuition and Fees

Mandatory Charges for Full–Time Resident Students

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

Systemwide tuition and fees

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

$12,192

|

$12,192

|

$12,192

|

|

Graduate—academic

|

12,192

|

12,192

|

12,192

|

|

Graduate—professionala

|

16,192 – 47,340

|

16,192 – 50,740

|

16,192 – 50,740

|

|

Average campus feeb

|

989

|

1,008

|

1,058

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

38,355

|

44,186

|

44,186

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

Systemwide tuition and fees

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

5,472

|

5,472

|

5,472

|

|

Teacher credential

|

6,348

|

6,348

|

6,348

|

|

Graduate—mastersc

|

6,738

|

6,738

|

6,738

|

|

Graduate—doctorald

|

10,500

|

11,118 – 16,148

|

11,118 – 16,148

|

|

Average campus fee

|

1,047

|

1,140

|

1,140

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

1,080

|

1,380

|

1,380

|

Places Cap on State–Supported Units. The Governor proposes placing a limit on the number of units the state would subsidize per student. Under the proposal, students taking units in excess of the cap generally would be required to pay the full cost of instruction. For 2013–14 and 2014–15, the Governor proposes a cap of 150 percent of the standard units needed to complete most degrees at UC and CSU. (The 150 percent cap equates to 270 quarter–units at UC and 180 semester–units at CSU.) Thereafter, the Governor proposes a cap of 125 percent of the standard required units at UC and CSU—about one extra year of coursework. For the community colleges, the Governor proposes a cap of 90 semester–units beginning in 2013–14. This cap also equates to about one extra year of coursework beyond that required for transfer or an associate degree. For CCC students who transfer to UC or CSU as juniors, the proposed cap is 150 percent in the first two years and 125 percent beginning in 2015–16 of the additional units needed to meet the requirements for a bachelor’s degree. According to the Governor, the unit cap is intended to create an incentive for students to shorten their time to degree, reduce costs for students and the state, and increase access to more courses for other students.

Proposes Two Changes to CCC Financial Aid Policies. Currently, many CCC students have a choice to apply for a BOG fee waiver using either the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or a separate BOG fee waiver form. Beginning in 2013–14, the Governor proposes to require CCC students to use only the FAFSA. The purpose of the proposal is to ensure that all financially needy students gain access to the full spectrum of allowable federal and state aid—rather than being able only to access a CCC fee waiver. Requiring students to complete the FAFSA also would result in better information about students’ financial means, as the current process for many CCC financial aid applicants relies on self–certified information. The Governor’s second proposal is to require campuses to take both student and parent income into account when determining certain students’ eligibility for a BOG fee waiver.

In this part of the report, we analyze the Governor’s specific higher education proposals. We group his proposals into three main sections. The first section focuses on several proposals relating to the Governor’s base funding increases for the three segments. The second section assesses the Governor’s three technology initiatives. The third section focuses on the Governor’s proposals relating to tuition, caps on state–subsidized units, and financial aid.

By providing the segments with large unallocated increases not tied to specific requirements, the Governor cedes substantial state responsibilities to the segments and takes key higher education decisions out of the Legislature’s control. For example, the Governor defers to the segments the issue of how many students California’s public higher education system will serve. We believe this type of decision should be made through the annual state budget process. Given our concerns with the Governor’s overall budget approach for higher education, we recommend rejecting several of his proposals. Specifically, as discussed in more detail below, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposals to: (1) provide the segments with unallocated base increases, (2) combine UC’s and CSU’s capital and support budgets, and (3) allow the universities to restructure their debt–service payments. In contrast to these proposals, we think the Governor’s proposal relating to CSU retirement costs has merit but are concerned with the absence of a proposal relating to UC retirement costs. Lastly, we think the Governor’s interest in rethinking how the state allocates funding to the community colleges also has merit, but we offer the Legislature an alternative that we think is much more likely to foster the state’s dual goals of providing student access and promoting student academic success.

Given High Costs and Mixed Outcomes, Justification for More Funding Unclear. The Governor provides $427 million in unallocated base funding increases to the institutions, with only a vague connection to undefined performance expectations. (Including additional funding provided in exchange for not raising tuition last year, cumulative new unallocated funding for the segments is $677 million.) Why the state would invest more in a system that is high cost and has poor outcomes without requiring explicit improvement is unclear.

Unallocated Increases Allow Segments to Pursue Own Interests Rather Than Broader Public Interests. For the universities, the Governor’s budget lumps virtually all of each segment’s funding into one pot and allows the segment to determine how best to spend the entire pot. For the community colleges, the Governor also provides an unallocated base augmentation linked neither to enrollment growth nor to any other identified public purpose. Rather than encouraging the segments to address state–identified problems and priorities, such an approach gives the segments much broader authority to pursue their top priorities. For example, the segments might decide to focus on more research, their law and medical schools, or administrative support, even if at the expense of broader public interests. Moreover, based on the segments’ own budget plans, the segments likely would use augmentations primarily for employee compensation. As a result, the augmentations would increase the cost per student. Given the almost complete removal of funding requirements and the associated weakening of the incentives segments have to focus on broader public interests, the Governor’s approach could end up exacerbating existing problems rather than improving the system.

Some Problems Can Be Addressed by Redistributing Rather Than Increasing Funding. Furthermore, most of the Governor’s proposals involve substituting more efficient or effective activities for existing ones. For example, increasing the availability of required courses while reducing the amount of excess course–taking could be done within existing resources. Likewise, the segments could leverage an existing repository of online courses developed by faculty and enable students more easily to access those courses largely, if not entirely, within existing resources. As these examples illustrate, the segments likely could achieve many of the goals set forth by the Governor using funds the state already provides.

If Additional Funding Provided, Use to Meet Highest Priorities. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s unallocated base increases, as they would be very unlikely to promote systemic change. We also recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s approach of providing equal dollar amounts to each university segment irrespective of its needs. Instead, we recommend the Legislature allocate any new funding to meet the state’s highest priorities. As a first priority, we recommend the state meet existing higher education obligations, including debt service, employee pension costs, and paying down community college deferrals.

Set Specific Improvement Targets and Review Performance Annually. If more funding is provided than needed to meet these existing funding obligations, then we recommend the Legislature link the additional funding with an expectation that the segments develop and implement strategies to improve legislatively specified student outcomes and meet identified cost–containment goals. Broad consensus already exists on some key outcome goals, including improving student persistence, transfer, and graduation; reducing costs; and maintaining quality. Moreover, the Legislature last year passed legislation outlining a process that would enable the state to measure progress and promote improvement in these areas through budget and policy decisions. Building on this foundation, the Governor and Legislature could establish specific improvement targets and a system for reporting on the segments’ performance relative to these targets. We also recommend the Legislature establish enrollment targets for all three segments to ensure that student outcome improvements do not come at the expense of existing student access. These performance and enrollment targets would send a clear signal to the segments regarding the state’s priorities and expectations. Compared with unallocated increases of seemingly arbitrary amounts, this approach would be far more likely to result in improved performance of the higher education system.

Weak Rationale for Proposed Changes to Capital Outlay Budget Process. The administration indicates the motivation for combining the universities’ capital and support budgets is to provide the universities with more flexibility, given limited state funding. The administration, however, has not identified specific problems associated with the current process used to budget the segments’ capital projects, nor identified any specific benefits the state might obtain from the proposal. As a result, both the problems the proposal is intended to address and the benefits that the proposal offers are difficult to ascertain. (How the administration proposes funding CCC facilities moving forward also is unclear.)

Legislature Would Lose Control of Key Budget Decisions. Not only does the Governor’s proposal not identify any benefits for the state, we find that the proposal has several serious drawbacks. Most troubling, the Governor’s approach is predicated on the Legislature relinquishing its role in capital decisions for the universities. That is, the Governor takes the Legislature out of the business of approving state buildings at the universities and gives it no role in determining the shares of higher education funding to be used for infrastructure and operations. As a result, the Legislature would have less oversight over the segments’ use of state funds and the segments would have even greater incentive to pursue their own institutional interests, instead of those benefiting the state more broadly. In addition, the Governor’s proposal would make planning for infrastructure spending statewide more difficult, as the state would not be able to prioritize funding as easily among the segments and/or other program areas.

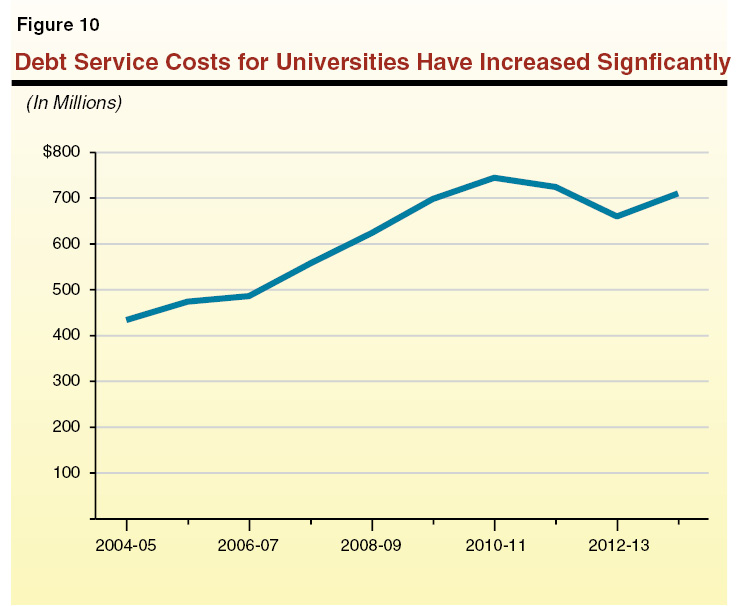

Funding Provided Under Proposal Not Linked With Any Assessment of Ongoing Needs. Another concern with the Governor’s proposal relates to the amount of funding he plans to provide the segments for their ongoing infrastructure needs. Specifically, the proposal presumes the amount of debt service funding related to one fiscal year (2013–14) is an appropriate amount upon which to base ongoing needs yet offers no evidence to this effect. It may be, for instance, that the current debt service amounts are too high. As shown in Figure 10, the state’s total debt service costs (general obligation bonds and lease–revenue bonds) for UC, CSU, and Hastings have increased significantly over the last decade—growing from $434 million ten years ago to $711 million today (an increase of 64 percent). The Governor’s proposal nonetheless effectively rolls into each of the three segments’ base budget a relatively high point in debt service, without attempting to determine how this amount relates to the segments’ ongoing needs.

Future Need for Infrastructure Spending Likely to Decrease. A related problem with the Governor’s proposal is that it does not take into account that the segments’ infrastructure needs likely will decrease significantly in the near future. One reason for this is demographic changes. The state projects that the 18 to 24 year–old population (the traditional college–age population at universities) will start to decline by about 1 percent annually starting in 2015. This means the segments may not require as many new buildings to accommodate enrollment as they have in past years when this age group was growing at a rapid pace. Moreover, the Governor’s proposal to change the delivery model for higher education would result in a significantly reduced need for infrastructure spending. In particular, moving more courses online and increasing summer sessions would reduce the demand for new, traditional facilities (as would other strategies that increased space utilization). Thus, even if the current debt service amounts were somehow reflective of the segments’ capital outlay needs at present, they could seriously overstate future needs.

Recommend Rejecting Proposal to Combine Capital and Support Budgets. Given the lack of a compelling policy rationale for the proposal, along with the serious concerns regarding the loss of the Legislature’s ability to plan and oversee infrastructure projects, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. If the Legislature is interested in developing a new process for funding the segments’ capital projects, then it would need to grapple with several fundamental issues. Most importantly, the Legislature would need to (1) identify the specific problems with the current capital outlay process and (2) develop a new method for allocating and overseeing funding that addresses these problems. As part of this process, if the Legislature did decide to combine capital and operational funding, then the Legislature would need to assess annual ongoing capital priorities, identify a reasonable initial amount to transfer, decide how to adjust that amount moving forward, and decide whether the segments should be able to pledge their state appropriations to issue debt. Without addressing such fundamental issues, we think moving to a new process as proposed by the Governor is premature.

UC’s Proposal Would Increase Future Costs Significantly in Exchange for Relatively Minor Short–Term Savings . . . In response to the Governor’s proposal to allow the universities to restructure state infrastructure–related debt, UC has developed one potential restructuring plan. (The CSU has not yet presented a proposal.) Under UC’s plan, it would restructure the existing lease–revenue debt over a 40–year period. Under the state’s current repayment schedule, this debt would be retired fully in half that time. Because the university would extend the repayment period so far into the future, UC estimates it could lower the annual debt service payment by about $80 million in the short term. After ten years, however, the university would begin paying a few million dollars more in debt service annually than under the current repayment schedule. This difference would increase significantly in later years, such that, over the life of the restructured debt, UC estimates it would pay an additional $2.1 billion. In today’s dollars, this means the restructuring would cost nearly $400 million.

. . . Which Could Make Investing in UC Facilities More Difficult in the Future. The university asserts that extending the repayment term to 40 years matches the life span of the buildings built with the bonds. By pushing debt out to years in which there otherwise would be no debt service, this approach, however, risks making investments in future facilities more difficult. For example, the university may have difficulty undertaking as many new capital projects 30 years from now as it otherwise could because it still would be paying off debt issued over 30 years earlier. (Though the demographic projections and policy proposals discussed earlier could mitigate the need for facilities in the near term, making similar judgments about facility needs several decades from now is more difficult.) Faced with such a situation, the university likely would have to (1) forgo capital projects it otherwise would have undertaken, (2) redirect funding that otherwise would have gone to support instruction or research, (3) seek additional funding from the state, and/or (4) increase student tuition.

Other Restructuring Proposals Also Would Not Be Worth Pursuing. The example above reflects one scenario provided by UC as to how it could restructure the state’s lease–revenue debt. The universities could develop other proposals with different repayment periods and financial assumptions. These proposals potentially could have lower costs compared to the proposal discussed above. By definition, however, restructuring typically means extending out debt repayments into the future. As a result, debt restructuring typically means paying more in interest. For this reason, the state does not restructure its debt to longer repayment periods. (The state routinely refinances its debt, however, to take advantage of lower interest rates. In these transactions, the state keeps the same repayment schedule or shortens it and saves money on interest costs.)

Recommend Rejecting Restructuring Proposal. Given that restructuring debt would cost more money in the long term and constrain future budget choices, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s debt restructuring proposal for the universities. If the Legislature is concerned that the universities would lose the short–term savings associated with the debt restructuring, it could consider other strategies for the universities to increase revenue or reduce costs.

Proposal for CSU Provides Some Benefits, Recommend Adopting. The Governor’s proposal to modify the way the state budgets for CSU retirement costs offers some minor benefits. Specifically, the proposal would provide an incentive for the university to consider retirement costs in its hiring decisions. Right now, the university likely ignores these costs since they are automatically covered by the state. Because the university no longer would receive automatic budget adjustments above the current payroll level, the Governor’s approach would incentivize CSU to be more cautious in its hiring and use its existing resources more efficiently. This could reduce both payroll costs and future retirement costs. At the same time, the proposal reasonably allows for future budget adjustments related to the university’s existing payroll to account for rate changes made by CalPERS. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature adopt the proposal.

Governor Does Not Directly Address UC Retirement Costs. Unlike for CSU, the Governor does not have a proposal to address retirement costs at UC. (He also does not have a proposal for Hastings—which participates in UC’s plan.) In the 2012–13 budget, the state provided $89 million to UC (and nearly $900,000 to Hastings) specifically to cover increased retirement costs. For 2013–14, UC has identified additional retirement costs of $67 million, due to an increase in employer contribution rates and an increase in payroll. (Hastings has identified $455,000 in additional costs.) The Governor’s budget does not identify any funding for these costs. The university could cover them, however, with a portion of the Governor’s proposed base augmentations. (Hastings could cover all but $63,000 of its costs with its proposed base augmentation.)

Three Budget–Year Considerations Related to UC Retirement Costs. In deciding how best to address UC’s retirement costs, we think the Legislature has three main issues to keep in mind.

- Cost Control. One major issue is that UC, unlike other state agencies, administers its own retirement plan. This means that UC determines its contribution rates, employee benefits, and investment options—all of which affect the plan’s costs. Given this, the state needs to assess UC’s retirement costs and benefits to ensure they are reasonable. For example, at the moment, UC employees contribute less to their pension plan than most state workers. Both the state and UC, however, have been undertaking many changes in their retirement programs and phase–in issues are making comparison of the two programs somewhat more difficult. Our best assessment today is that UC’s increased costs in 2013–14 appear reasonable.

- Payment Obligation. The state is not legally obligated to provide funding for the university’s retirement costs. Nevertheless, current retirement costs are largely unavoidable obligations for the university. Not addressing them means the university would incur significantly greater costs in the future. Addressing them without state funding means the university would have to cover the costs in some other way—such as by redirecting from its instructional program or increasing student tuition.

- Transparency. The Governor’s approach to provide UC with a base augmentation but not designate any of it specifically for retirement costs lacks transparency. For other state agencies, the state typically makes a baseline funding adjustment to cover retirement costs. This makes identifying how much funding is going toward this purpose possible and provides clarity for both the agency and the state. For UC, identifying retirement costs would show how much of its base augmentation is available for this and other purposes. For the state, identifying retirement costs would prevent the university from asserting in the future that it did not receive funding for this purpose.

Recommend Designating $67 Million for UC Retirement. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature specify $67 million of UC’s proposed 2013–14 base budget increase for pension costs. (For Hastings, we recommend the Legislature increase the Governor’s proposed base augmentation from $392,000 to $455,000 and designate the full amount for retirement.) In addition, consistent with the approach taken by the state in 2012–13, we recommend the Legislature include language in the budget reiterating that the state is not obligated to provide any additional funding for this purpose moving forward. Such language is intended to reinforce that the state is not liable for these costs.

Future Considerations for Universities’ Retirement Costs. The Legislature recently enacted pension–related legislation that could significantly reduce long–term retirement costs for nearly all public employers. In the future, the Legislature may want to consider the universities’ retirement costs in light of this legislation. This consideration would be useful since UC was specifically exempt from the legislation, while the applicability of some provisions to CSU is still being determined. In the future, the Legislature could consider providing the universities with funding for retirement costs comparable with costs incurred by other public employers. Under this approach, the universities would be responsible for any costs beyond that level. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider encouraging the universities to change their retirement plans to conform with other public employers by linking such changes with their state appropriation.

Current Funding Model Pays CCC for Providing Student Access, Not Promoting Success. Like any other organization, the way community colleges are funded drives their priorities and behavior. Because they are funded on enrollment at census, a top priority of the colleges is to ensure enough students are enrolled early in the term to meet their enrollment targets. While funding community colleges this way creates a positive incentive for colleges to provide students with access to instruction, the funding approach has been criticized for not creating a strong incentive for colleges to help students fulfill their broader academic objectives. For example, some community colleges have acknowledged that they have been reluctant to require new students to participate in assessment and orientation—support services that are strongly correlated with student success—for fear of “turning off” potential students. As a result, students may enroll in courses for which they are academically unprepared and have little chance of successfully completing. The need to meet enrollment targets also can create an incentive for colleges to offer popular instruction that “fills seats” but is primarily recreational in nature and outside of CCC’s core educational mission.

Legislature Has Shown Interest in New Funding Approaches That Improve Incentives. In recent years, the Legislature has expressed interest in modifying CCC’s funding model to address these issues. During the 2009–10 legislative session, AB 2542 (Conway) would have created a voluntary pilot program allowing up to five community colleges to be funded based on the number of students who successfully completed their courses (with bonus payments for increasing student graduations) rather than the traditional census method. Also during the 2009–10 legislative session, SB 1143 (Liu) sought to base CCC funding in part on successful course completions. After its passage in the Senate, this bill was amended to require the BOG to convene a task force to study “alternative funding options” and other strategies designed to improve student success at the community colleges. The legislation was signed by the Governor in fall 2010.

CCC Task Force Recommends Ongoing Study of Outcome–Based Options. In response to the legislation, the BOG created the Student Success Task Force. The task force was comprised of 21 members from inside and outside the CCC system. After meeting for nearly one year, the task force released Advancing Student Success in California Community Colleges in December 2011. The report contains a number of recommendations, including creation of a common assessment test for new students and development of a “scorecard” that measures student success rates at each college. While members did not reach consensus on whether to endorse funding outcomes in the report, the task force recommended the CCC Chancellor’s Office “continue to monitor implementation of outcomes–based funding in other states and model how various formulas might work in California.” The BOG formally adopted the Student Success Task Force’s recommendations in January 2012.

Some Advantages of Funding Course Completions Over Current Approach . . . Though the Governor’s proposal is not tied to a specific recommendation of the Student Success Task Force, funding course completions would have a couple of advantages over how CCC’s are currently paid. By not providing funding for students who fail to complete their courses, the proposed change could result in colleges providing more guidance to students regarding their readiness for collegiate instruction. For example, colleges would have a stronger incentive to assess more students and require students to demonstrate a minimum level of proficiency in reading, writing, and mathematics before attempting certain transfer–level courses. The Governor’s proposal also would help eliminate the current public perception that the state is paying for many students who are no longer enrolled. (We recognize, however, that colleges incur upfront costs to compensate instructors for teaching a course—costs that do not change if a student drops the course later in the term.)

. . . But Governor Misses Opportunity for More Meaningful Reform. Though funding course completions has some advantages over the current funding model, course completion is actually quite high at CCC—the systemwide average course retention is about 85 percent. Program completion, on the other hand, is low. According to the Institute for Higher Education Leadership and Policy, only about one–third of all CCC students seeking to transfer to a four–year institution or earn a certificate or associate degree actually do so. Whereas course retention is not a major problem, research has shown that students do tend to struggle to achieve other milestones on their educational path, such as returning the following year, completing their basic skills (remedial) sequences, passing transfer–level math and English courses, and reaching 30 units of college credit (one full academic year of coursework). By addressing only course retention, therefore, we believe the Governor is focused too narrowly on only one type of outcome—when instead the focus should be on several other more meaningful outcomes of student success.

Funding Course Completions Could Create Perverse Incentives for CCC. In addition, we are concerned that, if implemented, the Governor’s proposed funding model could create perverse incentives for community colleges. While average course retention rates are 85 percent, rates vary considerably by discipline and program. For example, mathematics and economics courses tend to have lower retention rates than fine arts and sociology courses. If the CCC system were to be funded based on course completions, colleges would have a perverse incentive to de–emphasize core programs with relatively low retention rates and increase offerings of noncore programs (such as physical education) with relatively high retention rates. Moreover, the Governor’s budget seeks to create incentives for CCC to offer “quality programs.” Yet if the state were to adopt his proposal, we are concerned that faculty would feel pressure to reduce course rigor or inflate grades so as to reduce the number of students who drop classes before the end of the term.

Proposed Funding Reallocation Mechanism Could Impair CCC Improvement Efforts. The Governor’s proposal also has a weak justification for redirecting any reduction in a districts’ apportionment funds relating from the shift to course retention to that districts’ Student Success and Support categorical program. In effect, the Governor presupposes that students do not complete their courses because of inadequate assessment or counseling services, but course–retention problems also can stem from a poorly designed or taught class. Yet, if the Governor’s proposal were adopted, the primary funds that support local professional development (apportionments) would be automatically shifted to a categorical program that has an unrelated purpose. Such a redirection of funds actually could serve to undermine a college’s efforts to improve student outcomes.

Consider Funding Approach That Supports Access and Success. For all these reasons, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to change the census date. We believe the Legislature could achieve the overarching objective of improving college and student outcomes by developing a more robust funding model that balances student access (enrollment) with student success (as measured by specific performance indicators). In effect, a disconnect exists today between the state’s message to community colleges and its funding mechanism—value both access and achievement but only get compensated for successfully providing access. We envision a better funding model that continues to place an important emphasis on enrollment and access but also creates stronger incentives for colleges to focus on student achievement by linking a portion of state funding to colleges’ ability to improve outcomes.

Building an Effective Funding Model. Currently, a number of other states (such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Washington) have adopted funding models that fund colleges for enrollment as well as student achievement. Other states (such as Illinois, Missouri, and South Carolina) adopted such an approach before abandoning it a few years later. Given all of these experiences to date, many best practices and lessons learned have been identified. We believe an effective funding model for the CCC system would include the following components.

- Specific Outcome Measures. The new system could have program–completion measures (such as graduations and transfers) as well as intermediate measures that influence program completion (such as reaching a certain unit threshold).

- Rules for Tracking Progress. The new system could measure year–to–year changes for each college. Colleges’ performance could be compared against themselves (rather than other colleges within the system) to account for differences in student demographics among colleges.

- An Integrated Allocation Mechanism. The new system could allocate a portion of base as well as new funds on performance results. Remaining funding could continue to be allocated based on enrollment. Over time, a larger share of funding could be linked to performance.

We believe building this type of funding model would be a significant improvement over both the current system and the Governor’s course–completion funding approach. States’ experiences with more robust outcome–based funding models indicate that such systems can play an important role in focusing institutional efforts on student success.

University Funding Model Also Has Basic Problems. The state’s approach to funding the universities also has a number of problems. Historically, the universities’ funding model similarly has emphasized access over success. That is, funding for UC and CSU traditionally has been based largely on the number of full–time equivalent (FTE) students the state expects each segment to enroll, multiplied by an estimated marginal cost per student. The marginal cost formula has been an important way to guide the segments’ student–faculty ratios, faculty salaries, and allocation of resources between research and instruction. Over the last five years, however, a series of unallocated budget reductions and augmentations has disconnected state funding from enrollment. By removing enrollment targets for the universities and delinking base augmentations from enrollment expectations for all three segments, the Governor’s budget effectively funds neither access nor success at the universities.

Consider Dual Enrollment and Achievement Funding Model for Universities Too. As the state’s budget stabilizes, the Legislature has an opportunity to establish a new basis for funding UC and CSU that balances access, student outcomes, and other state priorities. For example, instead of basing funding entirely on expected enrollment, the Legislature and Governor also could establish targets for degrees earned, research activity, and cost reductions. When determining funding allocations to each segment, the Legislature could consider the segment’s performance in these areas. In addition, the Legislature could direct the universities to include incentives for improving student achievement (analogous to those described above for CCC) in their internal allocation of state funds across campuses. In these ways, the state could promote both student access and success through its support of the universities.

In an effort to expand access to instruction at a lower cost, the Governor’s budget includes several related technology and efficiency proposals. We think these proposals can help place even greater attention on how best to open up new college opportunities. However, as discussed in more detail below, we believe many of the improvements sought by the Governor through these proposals could be accomplished largely within existing resources.

Online Education Can Promote Access, Efficiency, and Student Learning. Online education has been found to have numerous benefits, including making coursework more accessible to students who otherwise might not be able to enroll due to restrictive personal or professional obligations and allowing campuses to serve more students without a commensurate need for additional physical infrastructure. Moreover, research suggests that, on average, postsecondary students who complete online courses learn at least as much as those taking the same courses solely through in–person instruction (though students tend to drop online courses at higher rates than face–to–face courses). Recently, massive open online courses (MOOCs) also appear to be paving the way for open–access instruction—often taught by the country’s most distinguished professors—at minimal or no cost to students.

Need for New Funding to Create More Courses Is Questionable. We do not see a justification, however, for earmarking $10 million each for UC and CSU and up to $16.9 million at CCC for the development of additional online courses. Each year the state provides funds to UC, CSU, and CCC to support their operational costs. The segments use these monies to pay faculty to develop and deliver instructional content, and campuses generally decide on their own whether that content is offered through face–to–face or online courses. The segments have chosen to use their general–purpose monies to fund a considerable amount of online education. In 2011–12, the CCC system spent approximately $500 million serving over 100,000 FTE students through online education (about 10 percent of total instruction provided that year). Though CSU does not separate out costs by instructional type, online education is commonly used, with each of the segment’s 23 campuses providing such instruction (primarily to undergraduate students). And, while historically UC has offered very little state–supported online instruction, over the past couple of years UC has expanded its online program—with plans to continue adding courses in the near future. Among the three segments, we estimate that more than 20,000 undergraduate courses (and more than 30,000 course sections) were offered online in 2011–12. It is unclear to us, then, why the segments require ongoing augmentations to develop more online courses.