LAO Contact

Related Content . . .

December 14, 2016

The Administration's Sacramento Office Building Construction Strategy:

Ensuring Robust Oversight

Executive Summary

$1.3 Billion Approved in 2016–17 Is First Step in Administration’s Larger Strategy. In adopting the 2016–17 budget package, the Legislature established the State Project Infrastructure Fund (SPIF), which is continuously appropriated for state projects. The Legislature further provided $1.3 billion to the SPIF over two years for three specific state office building construction projects in Sacramento. These projects reflect the first step of the administration’s larger regional strategy to construct or renovate a total of 11 state office buildings in the Sacramento area over the next ten years. We expect that in the coming years the administration will come forward with more than $1 billion in additional funding requests to continue to carry out this strategy.

Administration’s Approach to Strategy Raises Some Specific Concerns. Assessing the condition of the state’s office buildings and taking a regional approach to maintaining these assets makes sense and is consistent with legislative direction. However, we identify some specific areas of concern for the Legislature as it faces decisions about (1) whether to move forward with additional state building projects and (2) how best to oversee the projects funded with the $1.3 billion provided in 2016–17. Specifically, we find the following:

- Strategy Lacks Adequate Analysis. The administration’s strategy lacks basic information necessary to determine its merits, including its costs, benefits, and potential alternative approaches—such as addressing a different mix of buildings from the 11 state office buildings that are proposed.

- Strategy Is Ambitious. The strategy includes an ambitious construction and renovation schedule, which the administration is already falling behind. Additionally, while the administration has not provided cost estimates, the strategy is likely to be expensive and appears to be growing more so.

- Existing SPIF Process Is Problematic for Future Projects. The administration indicates that it plans to continue to use the SPIF funding process—including the use of continuous appropriations—for future projects. This process—which allows the administration to establish and fund projects without legislative approval—greatly reduces legislative control and oversight compared to the traditional budget process. Furthermore, the weaknesses of the process are magnified when more funds are added to the SPIF because the additional funds increase the monies available for the administration to fund projects that were not envisioned by the Legislature.

Recommend Legislature Provide Clear Direction to Administration on Strategy. We recommend that the Legislature take the following actions to address the above concerns:

- Direct the administration to provide a robust analysis of its strategy. This should include information necessary to evaluate the merits of the strategy, such as the strategy’s costs, benefits, and other available approaches to addressing state office building deficiencies.

- Closely monitor the expenditure of the $1.3 billion approved in 2016–17 through the use of hearings at key points in project life cycles.

- Make it clear to the administration that any future funding provided for state office building projects should go through the typical budget process rather than a continuous appropriation under the current SPIF process.

We believe these recommendations would help ensure that the state has the information it needs to move forward with the best available strategy for addressing its buildings in the Sacramento area and that any funds provided are spent with adequate legislative oversight and accountability.

Introduction

In adopting the 2016–17 budget package, the Legislature established the State Project Infrastructure Fund (SPIF) and provided $1.3 billion over two years for three specific state office building projects in the Sacramento area. These projects reflect the first step of the administration’s larger regional strategy to expand and improve state office buildings in the Sacramento area over the next ten years. In the coming years, the Legislature will be presented with important decisions related to this strategy. Specifically, the Legislature will have to determine whether to proceed with the additional projects envisioned in the administration’s regional strategy. Additionally, the Legislature will have to decide how to best oversee the projects funded with the $1.3 billion provided in 2016–17.

This report is intended to help guide the Legislature as it makes these decisions. We begin by providing background information on Sacramento state office buildings and summarizing the actions taken in the 2016–17 budget process. Next, we assess the administration’s regional strategy for state office buildings in the Sacramento area. Finally, we provide recommendations to assist the Legislature as it faces key decision points related to the administration’s strategy.

Background

The state, through the Department of General Services (DGS), owns and maintains 58 general purpose office buildings across the state. Thirty–four of these buildings—totaling over 8 million square feet—are in the Sacramento area. These Sacramento area buildings are valued at over $4 billion and house 35 state departments and agencies, such as the Department of Water Resources and the Franchise Tax Board. The state also leases about 8 million square feet of general purpose office space in the Sacramento area. (We note that some state departments other than DGS operate office space for more specific purposes. For example, the Department of Motor Vehicles operates field offices.)

Legislature Required Analysis of Sacramento Office Buildings

DGS Directed to Perform Sacramento Office Planning Effort. As part of the 2014–15 budget, the administration proposed and the Legislature approved a total of $2.5 million for DGS to complete a long–range planning study (Long–Range Study) of state–owned general purpose office space in the Sacramento area. The Long–Range Study was to include (1) an update of an earlier planning study identifying potential office space development opportunities in Sacramento (Office Planning Study); (2) condition assessments of all state office buildings in the Sacramento area (Sacramento Assessment Report); (3) a plan for sequencing the renovation or replacement of state office buildings in Sacramento (Sequencing Plan); and (4) a funding plan for undertaking these projects, including project cost estimates and an economic analysis (Funding Plan).

Chapter 451 of 2014 (AB 1656, Dickinson) required that DGS complete this Long–Range Study by July 1, 2015, as well as provided direction on the contents of the study and how it was to be used by DGS. First, the legislation specified that the study should guide the state’s actions on state buildings over the next 25 years. Second, it required that DGS use the information in the Long–Range Study as the basis for developing detailed cost and scope information to be considered in future budget proposals. Finally, it directed DGS to issue requests for proposals to address the renovation and replacement needs of Sacramento office buildings, starting with the three buildings with the most significant and immediate facility needs.

Office Planning Study Identified Potential Office Development Sites. In 2015, DGS completed the Office Planning Study component of the Long–Range Study, which identified and ranked 41 potential sites in Sacramento for future development over the next 40 years based on an evaluation of the feasibility of developing the sites. Using criteria such as size, ownership (state–owned versus privately owned), and access to transportation, the evaluation rated the seven best sites as “superior” and nine additional sites as “good.” As shown in Figure 1, some of these sites are state–owned and some are privately owned. Additionally, the development time frames for these sites vary, with some potentially ready for development within five years—such as Downtown Block 204 (currently occupied by a parking lot and the historic Heilbron House)—and others available for development within six to ten years—such as the State Printing Plant site. Many of these sites contain existing buildings that would have to be demolished or moved to accommodate new development.

Figure 1

Potential Superior and Good Development Sites Identified in Sacramento Office Planning Study

|

Site |

Ownership |

Development |

Location |

|

Superior |

|||

|

Bonderson Building site |

State |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

CalPERS site |

State |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

Downtown Block 275 |

State |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

Downtown Blocks 203 and 204 |

State |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

Food and Agriculture Annex site |

State |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

Franchise Tax Board site |

State |

0–5 |

County (near Rancho Cordova) |

|

Richards Boulevard area |

Private |

0–5 |

Railyards area/River District |

|

Good |

|||

|

Resources Building site |

State |

6–10 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

State Printing Plant site |

State |

6–10 |

Railyards area/River District |

|

Downtown Core |

Private |

0–5 |

Downtown Sacramento |

|

Bradshaw Landing |

Private |

0–5 |

County (near Rancho Cordova) |

|

Granite Park |

Private |

0–5 |

Granite Regional Park area (near Tahoe Park) |

|

Railyards area |

Private |

0–5 |

Railyards area/River District |

|

Southport Business Park |

Private |

0–5 |

West Sacramento |

|

West Capitol Downtown |

Private |

0–5 |

West Sacramento |

|

Pioneer Bluff area |

Private |

6–10 |

West Sacramento |

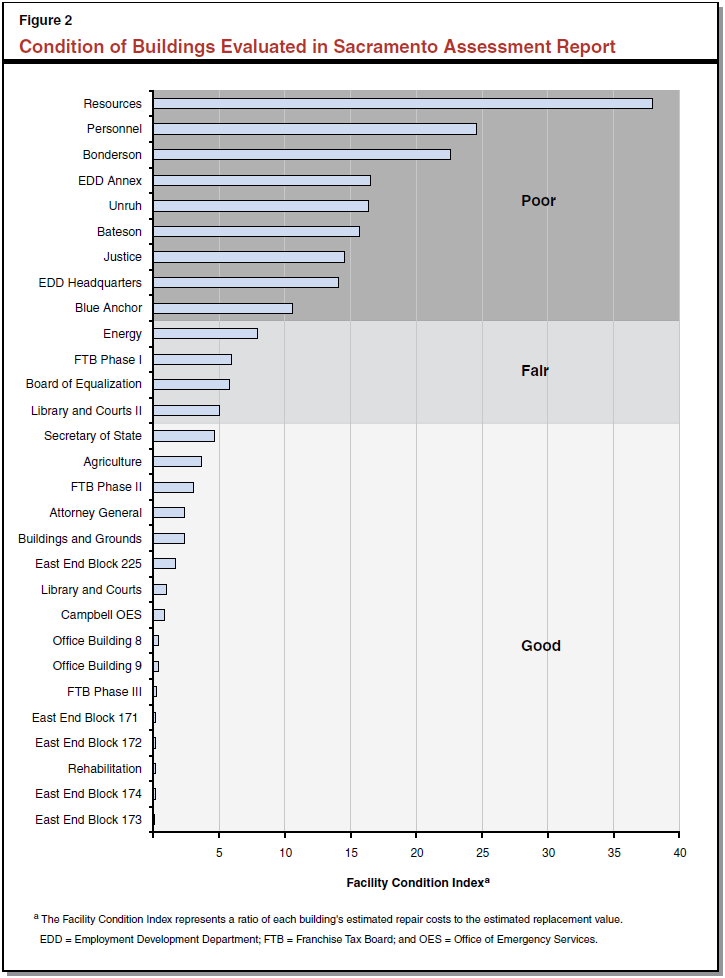

Sacramento Assessment Report Identified Buildings With Highest Needs. In July 2015, DGS released the Sacramento Assessment Report portion of the Long–Range Study. The report evaluated 29 state–owned office buildings in Sacramento. (The report excluded a few buildings that were vacant or that DGS did not consider to be typical office space, such as the State Capitol Annex.)

Overall, the Sacramento Assessment Report noted that all of the buildings that were evaluated were in a safe, serviceable, and functioning condition. The report developed a Facility Condition Index (FCI) score for each building, which compared the estimated costs of repairing versus replacing the building. (A high FCI score means that a building’s repair costs are relatively high compared to cost of replacement.) Based on this analysis, the report ranked the 29 buildings, identifying 9 in poor condition, 4 in fair condition, and 16 in good condition, as shown in Figure 2. The report ranked the Resources Building, Personnel Building, and Bonderson Building as those in most critical need of renovation or replacement and recommended prioritizing the needs of these buildings over other buildings, consistent with the direction provided in Chapter 451. The report also found that all of the buildings that were evaluated had FCIs well below 65, which is the industry standard for replacement. This suggests that all of the buildings that were evaluated are better candidates for repair rather than replacement. (As we discuss later, in September 2016 the administration completed assessments of the condition of general purpose office buildings in other parts of the state besides Sacramento.)

Funding Provided for First Three Projects

2016–17 Budget Package Included $1.3 Billion Over Two Years. The 2016–17 budget package provided $1 billion from the General Fund in 2016–17 and $300 million in 2017–18 to be deposited into a new fund, the SPIF. This funding is to be used for three buildings in the Sacramento area: a new building at the current Food and Agriculture Annex site on O Street (O Street Building), a new Resources Building at a different site, and either replacement or renovation of the State Capitol Annex. (Throughout this report, we refer to these three projects as the “three initial projects.”)

SPIF Funds Are Continuously Appropriated. In adopting the 2016–17 budget package, the Legislature passed Chapter 31 of 2016 (SB 836, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), which governs the use of the SPIF. Chapter 31 specifies that monies in the SPIF are continuously appropriated. It also authorizes the administration to establish and move forward with projects without having to receive legislative approval through the traditional state budget process, as is typically required for capital outlay projects. (Please see the nearby box, for a detailed description of the traditional state budget process for capital outlay projects.)

Traditional State Budget Process for Capital Outlay Projects

Under the traditional state budget process, the administration proposes individual capital outlay projects as part of the Governor’s proposed budget for the coming fiscal year. These capital outlay budget change proposals generally include important details on the proposed projects—such as the project scope, construction timeline, costs by project phase, funding sources, delivery method, and a narrative justification. They also include an analysis of alternatives and an explanation of why the alternatives were rejected in favor of the proposed project.

Typically, the administration submits proposals prior to being able to initiate certain design and construction phases of a project. As part of its review of these proposals, the Legislature assesses if projects are consistent with its funding priorities and the long–term programmatic needs of the relevant department.

After an individual capital outlay project is approved, the Legislature maintains oversight of certain changes related to the project. Specifically, if the scope of a project changes substantively or if the project’s costs increase by more than 20 percent, the administration is generally required to seek legislative approval through the traditional budget process before being able to proceed. (If the project’s scope changes minimally or its costs increase by between 10 percent and 20 percent, the typical process requires the administration to notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee.) If the Legislature has concerns about the administration’s proposed changes, the Legislature has the opportunity to reject them or to direct the administration to make changes to address the concerns.

Certain Notifications Required for Funded Projects. Chapter 31 requires the administration to provide the Legislature with quarterly reports and notifications in order to establish and move forward with SPIF–funded projects. Figure 3 summarizes the required notifications. For example, at least 20 days before spending SPIF funds on project planning activities, the administration must provide the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) with a notice identifying the purpose of the planning activity and its estimated costs. In September 2016, the administration provided the Legislature with the first notification through this process—a 20–day notification regarding its intent to spend $4.9 million on the development of the cost, scope, and delivery method for the O Street Building and the new Resources Building. The notification review periods for the Legislature range from 20 to 60 days depending on the project and activity. We note that, because of its unique characteristics, Chapter 31 created a separate process for the State Capitol Annex as described in the nearby box. As such, when we discuss state office buildings in this report, we do not include the State Capitol Annex unless otherwise specified.

Figure 3

Required Notifications for State Projects Funded Through the State Project Infrastructure Funda

|

Activity |

Contents of Required Notice |

Minimum Number of Days of Advanced Notification |

|

Expenditure of funds on planning activities |

Purpose of planning activity and estimates of costs |

20 |

|

Establishment of scope, cost, and delivery method |

Scope, budget, delivery method, expected tenants, and schedule for any space to be constructed or renovated as part of that state project |

45 or 60b |

|

Approval of the project design of a state project by State Public Works Board |

Updated estimates of cost and schedule |

30 |

|

Contract or a lease arrangement for a state project that includes construction |

Updated estimates of cost and schedule |

30 |

|

Change to the scope of an approved project |

Change in the scope and any associated costs |

20 |

|

Change in the cost of an approved project of between 10 percent and 20 percentc |

Change in the cost |

20 |

|

aExcludes State Capitol Annex project, which is governed by a separate notification process. bMinimum of 45 days must be provided for the O Street and new Resources building projects. Minimum of 60 days must be provided for other state projects. cThe administration indicates that it interprets the law to require them to seek legislative approval of cost increases over 20 percent. |

||

State Capitol Annex Project Governed by Separate Process

The State Capitol Annex (Annex) is a unique building owned by the state. Built in 1952, the Annex is attached to the east side of the historic Capitol building, which was constructed in 1874. In order to make room for the Annex, the original design of the east side of the Capitol, including a distinctive semi–circular architectural structure known as an apse, was destroyed. Today, the Annex provides roughly 365,000 square feet of space for legislative and gubernatorial offices as well as a variety of committee rooms. Additionally, more than one million visitors are estimated to visit the State Capitol and its Annex annually. Because of its distinctiveness, Chapter 31 of 2016 (SB 836, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) creates a separate process to guide the project that will replace or renovate the Annex. The separate process for this project envisions a collaborative approach between the administration and the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Rules (JCR). It also specifically requires the Department of General Services to report to JCR on the scope, budget, delivery method, and schedule for the Annex project.

Administration’s Sequencing Plan Strategy

Administration Released Sequencing Plan for Next Ten Years. In March 2016, DGS released the Sequencing Plan portion of the Long–Range Study. The Sequencing Plan represents the administration’s proposed strategy for addressing the facility needs of Sacramento office buildings—including the three initial projects—over the next ten years. (We also refer to this Sequencing Plan as the administration’s “strategy” in this report.) We note that the administration indicates that it no longer plans to complete the remaining portion of the Long–Range Study, the Funding Plan.

Administration’s Strategy Articulates Certain Principles. While addressing building condition needs is a primary motivation for the strategy, the administration indicates that the strategy is also intended to serve other goals, such as consolidating department office space to colocate staff working on similar topics and reducing the use of leased space by constructing additional state–owned office space. Consistent with those goals, the strategy articulates the administration’s principles for state office projects, which are summarized in Figure 4. For example, one principle is to consolidate departments with similar functions in order to achieve operational and programmatic efficiencies. The Sequencing Plan also states a preference for state ownership of office space in high–cost areas (rather than leasing), under the assumption that state–ownership is more cost–effective.

Figure 4

Administration’s Principles for Sequencing Sacramento Office Space

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

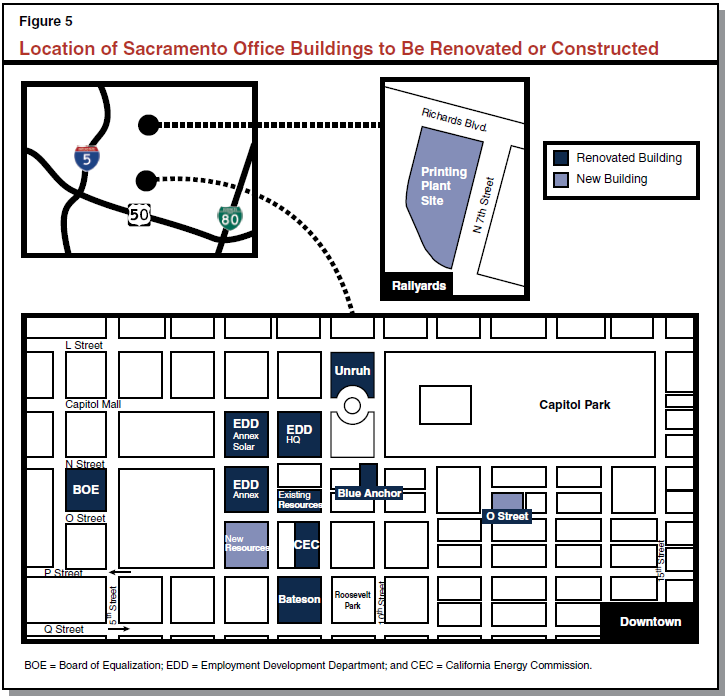

Administration’s Strategy Proposes Various Projects. In total, the strategy would result in constructing three new state office buildings consisting of about 2 million square feet—the new Resources Building, the O Street Building, and a new building at the State Printing Plant site—and reducing leased space by a roughly equivalent amount. (The funding provided in 2016–17 is for the new Resources and O Street Buildings, as well as the State Capitol Annex.) The strategy also proposes to renovate eight existing state office buildings consisting of about 2 million square feet. These activities would occur over a ten–year period. Nearly all of the buildings proposed to be constructed or renovated are within the downtown core of Sacramento, as shown in Figure 5. In total, the strategy would address one of the three worst buildings identified in the Sacramento Assessment Report—the Resources Building. We note that the administration proposes the design–build delivery method—in which a single contractor designs and constructs a project—for all of the planned projects.

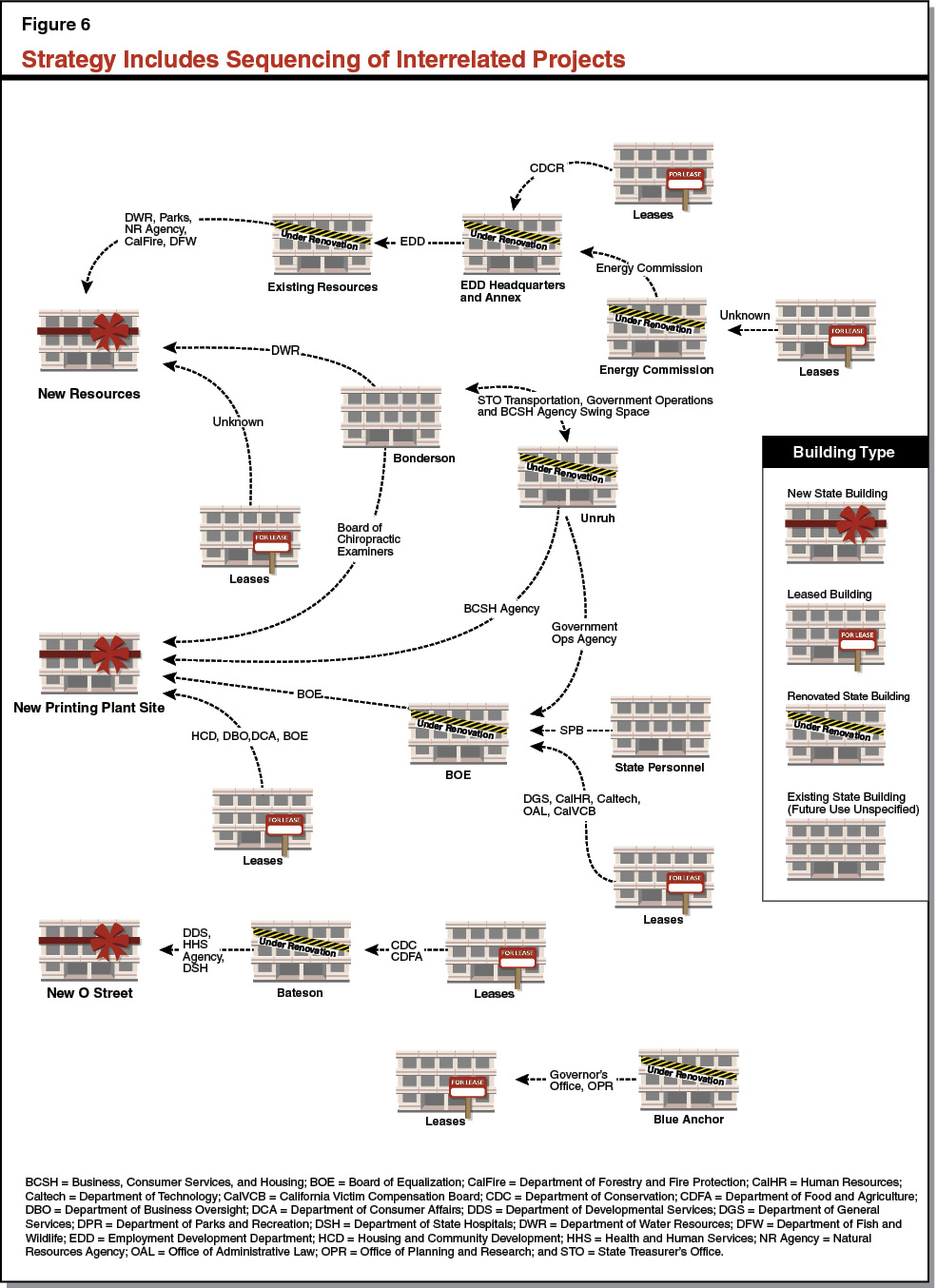

Strategy’s Projects Are Closely Interrelated. In most cases, the proposed projects in the administration’s strategy are interrelated. This is because the administration is generally proposing to strategically sequence the building renovations by successively conducting staff moves and building renovations. Consistent with its stated goals, strategically sequencing building renovations would allow DGS to reduce the number of relocations that departments must undergo since department staff would not move back into their original buildings after those buildings are renovated. Limiting the number of staff relocations can be worthwhile because relocations can affect department operations and result in significant costs, including costs to lease temporary space during renovations and move office equipment and files.

As shown in Figure 6, under the administration’s plan, the construction of the new Resources Building is the first step in the renovation or construction of many other interrelated state buildings. Once the new Resources Building is constructed, staff from the existing Resources Building will be relocated to the new space. The vacated Resources Building will then be renovated, and staff from the Employment Development Department (EDD) Headquarters and Annex Buildings will be relocated to the renovated space. That, in turn, will leave the EDD Headquarters and Annex Buildings vacant and available for renovation and the relocation of the staff from the Energy Commission Building. Through the ten–year planning window covered by the plan, this chain will continue until the state ultimately moves staff from existing leased space into newly renovated state office space. Similar sequencing of staff moves and renovations is envisioned related to the construction of the new O Street Building and State Printing Plant site.

Assessments of Office Buildings in Other Parts of State

In addition to assessing the condition of Sacramento area buildings as required by Chapter 451, DGS released an assessment of 21 office buildings totaling about 5.1 million square feet in other parts of the state (Statewide Assessment Report). This assessment was completed in September 2016 and developed the FCI for each of these buildings. As shown in Figure 7, this assessment identified 2 additional buildings in poor condition, 5 in fair condition, and 14 in good condition. In some cases, these buildings were rated in worse condition than buildings in Sacramento. Specifically, based on their current condition, two buildings—the San Diego State Building and the Stockton State Building—ranked among the ten state office buildings most in need of repair.

Figure 7

Ranking of Office Buildings Outside of Sacramento

|

Building |

City |

Age (Years) |

Condition |

Facility |

Statewide |

|

San Diego State Building |

San Diego |

53 |

Poor |

17.3 |

4 |

|

Stockton State Building |

Stockton |

52 |

Poor |

12.9 |

10 |

|

Fresno Water Resources Building |

Fresno |

49 |

Fair |

9.9 |

12 |

|

Hugh Burns State Building |

Fresno |

56 |

Fair |

8.0 |

13 |

|

Santa Ana State Building |

Santa Ana |

40 |

Fair |

6.9 |

15 |

|

Redding State Building |

Redding |

53 |

Fair |

6.1 |

16 |

|

Van Nuys State Building |

Los Angeles |

32 |

Fair |

6.0 |

17 |

|

Mission Valley State Building |

San Diego |

16 |

Good |

4.3 |

22 |

|

Justice Joseph A. Rattigan Building |

Santa Rosa |

33 |

Good |

4.3 |

23 |

|

Ronald Reagan State Building |

Los Angeles |

25 |

Good |

4.0 |

24 |

|

Wadie P. Deddeh State Office Building |

San Diego |

10 |

Good |

2.8 |

27 |

|

Red Bluff State Building |

Red Bluff |

47 |

Good |

2.8 |

28 |

|

Ronald M. George State Office Complex/Earl Warren |

San Francisco |

94 |

Good |

2.5 |

29 |

|

California Tower |

Riverside |

44 |

Good |

2.0 |

32 |

|

Alfred E. Alquist Building |

San Jose |

33 |

Good |

1.8 |

33 |

|

Governor Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Building |

San Francisco |

32 |

Good |

1.2 |

35 |

|

4th District Court of Appeal |

Riverside |

17 |

Good |

0.9 |

38 |

|

Junipero Serra Office Building |

Los Angeles |

102 |

Good |

0.7 |

39 |

|

Elihu M. Harris State Building |

Oakland |

18 |

Good |

0.4 |

40 |

|

Ronald M. George State Office Complex/Hiram Johnson |

San Francisco |

18 |

Good |

0.3 |

43 |

|

Leo J. Trombatore Building |

Marysville |

6 |

Good |

0.1 |

49 |

LAO Assessment

Overall, the concept of addressing state office building needs as part of a regional strategy—rather than on an ad hoc basis—makes sense. However, we identify below several specific areas where the administration has not provided adequate information and a robust analysis to ensure that the Legislature can assess whether its strategy is a good approach, much less the best approach available to the state to address these buildings in the future. Additionally, we find that the strategy is ambitious—both in terms of cost and schedule—and that the existing SPIF process does not facilitate adequate legislative oversight.

Taking a Regional Approach Makes Sense

The state needs to take care of its office buildings in order to ensure that they can continue to provide services for years to come. Additionally, addressing state office buildings as part of a regional strategy makes sense. We find that a regional strategy—informed by data on building needs from recent facility assessments—is important for a few reasons.

- First, it allows the state to get a more complete understanding of the condition of the state office buildings across the region, rather than focusing only on certain buildings. This can better enable the state to prioritize resources to higher–need buildings.

- Second, a regional strategy allows the state to assess Sacramento–area building needs in the context of other state goals. For example, the administration identified colocating department staff. A regional strategy enables the state to consider those types of goals, along with identified facility needs, as it directs resources within the region.

- Third, a regional strategy can enable the state to take advantage of opportunities to strategically sequence building renovations in the region. This can help to reduce the number of required building relocations and their associated costs.

Given the advantages of a regional approach, we find that the Governor’s efforts so far to address this important topic in a systematic way is a step in the right direction, including his release of a strategy outlining the timing of future state office projects in Sacramento.

Administration’s Strategy Lacked Adequate Analysis

The administration’s specific sequencing strategy for addressing Sacramento office buildings could be a good strategy, or even potentially the best strategy, available to the state over the coming years. However, it is impossible to assess whether this is the case because the strategy lacks much of the key information necessary to make such an assessment. Specifically, the strategy lacks basic information on its costs, its benefits, and potential alternatives that are available. It is particularly important for the Legislature to have this information given the scale and costs of the identified projects.

No Analysis of Costs. The administration has not provided any estimate of the costs of its strategy. We would typically expect the administration to prepare such an analysis as part of the development of its strategy, just as we would expect the administration to provide cost estimates for any proposal. This type of information is necessary for the Legislature to be able to weigh the merits of the proposed projects against its other priorities for limited state resources.

Recognizing this importance, the 2014–15 budget provided DGS with funds to undertake the Funding Plan component of the Long–Range Study, which was to include cost estimates of planned projects the administration proposed to pursue. However, the administration indicates that it no longer plans to complete this Funding Plan. (It is unclear how the funding provided was used.) We note that an overall cost estimate for the strategy—rather than a piecemeal approach that only provides cost estimates for individual projects when they are proposed—is particularly important because of the interrelated nature of the projects within the strategy. It is difficult for the Legislature to make an informed decision about any individual future project without even a rough understanding of the costs (and benefits) of the related projects in the strategy.

Benefits of Strategy Not Identified. The administration has also failed to clearly articulate the benefits that it expects to achieve from the proposed strategy and to quantify them where feasible. As with any proposal, it is important for the Legislature to receive information on the expected benefits of the strategy in order to determine whether it is justified. We recognize that in many cases, these benefits are not likely to be quantifiable. For example, it is probably impossible to fully value the benefits associated with providing modern office space to employees. Additionally, it is difficult to fully assess the operational savings achieved from colocating department staff. However, even if these benefits are not quantifiable, it is still valuable for the administration to fully identify and describe them in order to support its rationale for proceeding with the strategy.

We also note that there are some benefits that could be quantified. In those cases, we would expect the administration to estimate and report them. For example, one of the administration’s stated principles is to make both the new and renovated facilities in the strategy Zero Net Energy—that is, to have them generate as much energy on–site as they use on an annual basis. Given the reduced energy use that this goal implies, we would expect the administration to include an estimate of the resulting financial savings (as well as the costs to achieve these benefits). Additionally, the strategy involves building 2 million square feet of new state office space that will ultimately replace state leases—resulting in some state savings associated with fewer leases. We would expect the administration to quantify the savings from fewer leases and compare them to the costs of constructing this new space. We note that when we conducted this type of comparison based on available data and using some standard assumptions, we found that it could take over 100 years for the savings from lower lease costs to offset the construction and operating costs associated with the new buildings proposed. By that point, these buildings likely would be well beyond their useful lives.

No Analysis of Alternatives. The administration’s strategy also fails to include an analysis of available alternatives. Specifically, an analysis that evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of the alternatives and explains why the administration ultimately rejected them in favor of the proposal. Such an analysis is necessary for the Legislature to effectively understand the various options available and assess whether the administration’s proposal is not only a good option, but the best option available.

We note that there are two main alternatives that are available to the state that the administration should have included it its analysis. First, the administration should have analyzed options for addressing a different mix of state office buildings than the 11 state office buildings that are proposed. This should have included an alternative that addresses the three Sacramento office buildings assessed to be in the worst condition, consistent with the legislative direction provided in Chapter 451. As shown in Figure 8, two of the three buildings in worst condition—the Personnel Building and the Bonderson Building—are not addressed in the administration’s strategy. It also should have included an option that addresses other high–need, “poor condition” buildings, as three of the nine poor condition buildings in Sacramento are not included in the administration’s strategy.

Figure 8

Condition of Sacramento Area Office Buildingsa

|

Building |

Condition |

Facility Condition Index |

Condition Ranking |

Age (Years) |

Renovated or Replaced in Plan |

|

Resources Building |

Poor |

38.0 |

1 |

52 |

Yes |

|

Personnel Building |

Poor |

24.5 |

2 |

62 |

No |

|

Bonderson Building |

Poor |

22.6 |

3 |

33 |

No |

|

EDD Annex |

Poor |

16.5 |

4 |

33 |

Yes |

|

Jesse M. Unruh Building |

Poor |

16.4 |

5 |

87 |

Yes |

|

Gregory Bateson Building |

Poor |

15.7 |

6 |

35 |

Yes |

|

Justice Building |

Poor |

14.5 |

7 |

34 |

No |

|

EDD Headquarters |

Poor |

14.1 |

8 |

61 |

Yes |

|

Blue Anchor Building |

Poor |

10.6 |

9 |

84 |

Yes |

|

California Energy Commission Building |

Fair |

8.0 |

10 |

34 |

Yes |

|

FTB Phase I |

Fair |

6.0 |

11 |

32 |

No |

|

Board of Equalization Headquarters Building |

Fair |

5.8 |

12 |

24 |

Yes |

|

Library and Courts II Building |

Fair |

5.0 |

13 |

22 |

No |

|

Secretary of State/Archives Building |

Good |

4.6 |

14 |

21 |

No |

|

Agriculture Building |

Good |

3.7 |

15 |

80 |

No |

|

FTB Phase II |

Good |

3.0 |

16 |

24 |

No |

|

Attorney General Building |

Good |

2.4 |

17 |

21 |

No |

|

Buildings and Grounds Headquarters |

Good |

2.4 |

18 |

23 |

No |

|

East End Complex Block 225 |

Good |

1.7 |

19 |

14 |

No |

|

Stanley Mosk Library and Courts Building |

Good |

1.0 |

20 |

88 |

No |

|

Campbell Building—Office of Emergency Services |

Good |

0.9 |

21 |

14 |

No |

|

Office Building 8 |

Good |

0.4 |

22 |

47 |

No |

|

Office Building 9 |

Good |

0.4 |

23 |

47 |

No |

|

FTB Phase III |

Good |

0.2 |

24 |

11 |

No |

|

East End Complex Block 171 |

Good |

0.2 |

25 |

13 |

No |

|

East End Complex Block 172 |

Good |

0.2 |

26 |

13 |

No |

|

Rehabilitation Building (OB10) |

Good |

0.2 |

27 |

66 |

No |

|

East End Block 174 |

Good |

0.1 |

28 |

13 |

No |

|

East End Block 173 |

Good |

0.1 |

29 |

13 |

No |

|

aSacramento Assessment Report did not include buildings that were not considered to be suitable or available as typical office space, such as the Food and Agriculture Annex, the State Printing Plant, and the State Capitol Building and Annex. EDD = Employment Development Department and FTB = Franchise Tax Board. |

|||||

Second, the administration should have evaluated the most cost–effective way to address the needs of these buildings. For example, it should have included an analysis of whether it is more cost effective to construct new buildings versus pursue other approaches, such as purchasing or leasing existing privately owned office buildings. We note that this type of evaluation is particularly important for informing the Legislature’s future decision about whether to fund the new building at the Printing Plant site because there is growing evidence that the new buildings that were funded in 2016–17 are likely to be expensive compared to other available options. Specifically, based on the administration’s preliminary estimates, we expect the new Resources and O Street buildings to cost roughly $1,000 per square foot. This is well above the estimated cost of building a new high–rise in downtown Sacramento—about $400 to $500 per square foot—and far exceeds the recent sales prices of existing office buildings in the downtown area—generally under $300 per square foot. Also, when the opportunity costs of capital are taken into account, we estimate that the state’s annual costs of constructing and operating these new buildings would be more than double current market rents in the downtown area.

Proposed Strategy Is Ambitious

The proposed strategy is likely to be a significant General Fund expense and includes an ambitious construction and renovation schedule. There are also early indications that the strategy’s costs and timelines are already increasing for some of the three initial projects. Furthermore, given the interrelated nature of the projects in the strategy, these types of changes to initial projects have the potential to alter the schedule and associated costs of other projects in the strategy.

Cost of Strategy Unclear, but Could Total Almost $3 Billion. As previously indicated, the administration has not provided the Legislature with a cost estimate for the strategy. Additionally, it has failed to define the scope of each of the projects included in the strategy, which makes it difficult to develop an independent cost estimate. However, based on the best information available, we estimate that the administration’s strategy could cost a total of almost $3 billion. This estimate is based on the conceptual costs for new buildings provided in the administration’s 2016–17 budget proposal and the Office Planning Study. It also incorporates cost estimates for building renovations based on the ten–year facility needs identified in the Sacramento Assessment Report. (We augmented the costs identified in the Sacramento Assessment Report by about 50 percent to account for various costs that were not included in the report, such as labor and project management costs.) We note that it is possible that the actual costs could be different from our estimates. For example, the administration could propose to undertake different—and in some cases possibly more significant—renovations than the ten–year facility needs we assume.

Additionally, this $3 billion estimate includes the $1.3 billion already approved in 2016–17 for the initial three projects. To the extent that there are changes to the costs of these projects, it would also affect the overall cost of the strategy. There are some initial indications that the costs of these buildings will grow. Specifically, the new Resources Building and O Street Building are already undergoing revisions that are anticipated to increase costs. The new Resources Building was originally envisioned as a lease–purchase on private property, but is now planned to be constructed on Block 204, which is owned by the state. This change in project delivery method and location is anticipated to cost at least an additional $70 million over the original rough estimate of $530 million because there will be additional project management costs and a longer construction period. The administration also indicates that it may increase the size of the O Street Building, which would almost certainly increase construction costs.

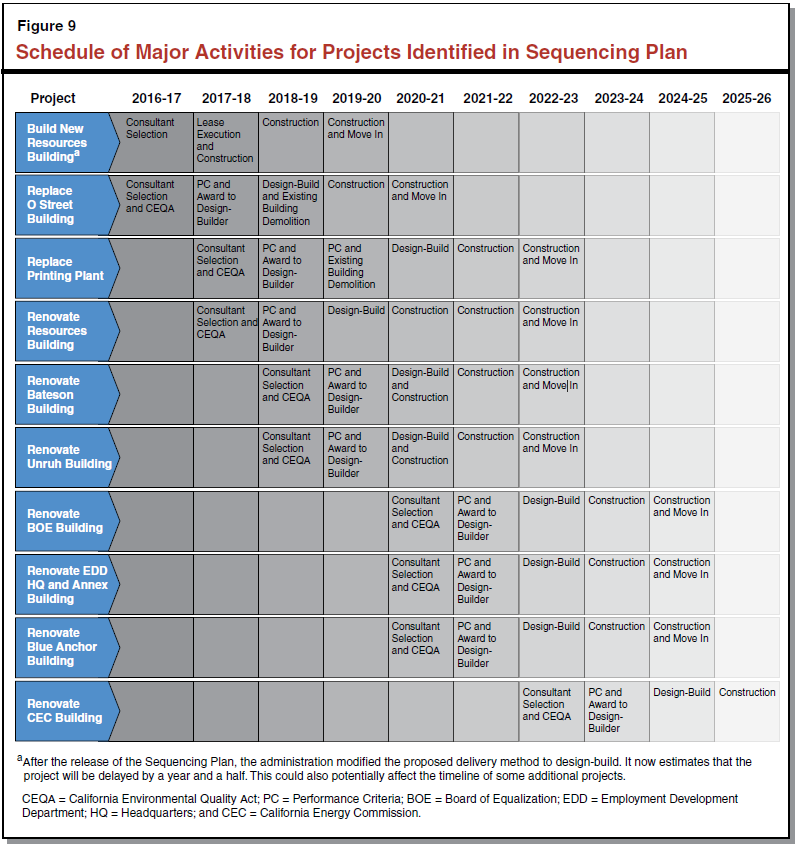

Strategy Has Ambitious Timeline. The strategy proposes to complete 11 state office buildings projects (including both the EDD Headquarters and Annex) within the ten–year planning window, as shown in Figure 9. Most of the individual construction projects are anticipated to be completed in four or five years from start to finish. This timeline is significantly faster than other state building projects. While DGS has not initiated the construction or major renovation of any state office buildings over the past ten years, it has generally taken the department at least six years to complete new state office building and major renovation projects in recent decades.

The relatively short time frame for the projects in the strategy leaves little additional time for contingencies once a project is initiated. To the extent that the administration encounters unanticipated circumstances that create project delays—such as unanticipated site conditions—it is unlikely that these delays could be accommodated without making changes to a project’s schedule. There are also early signs that schedule changes are occurring. Specifically, the administration indicates that the change to the location of the new Resources Building is expected to shift the schedule for the project back by more than a year compared to the timeline outlined in the strategy. As this project and other projects progress and their scopes are further refined, there is risk that there could be other changes that could affect timelines and potentially associated costs.

Project Delays Would Likely Have Cascading Effects. The interrelation between the different projects in the strategy means that delays that affect one project would likely have sequential effects on other projects. For example, the one–year delay to the construction of the new Resources Building would affect the timelines of the other projects that are connected to the new Resources Building project—such as the renovations of the existing Resources Building and the Unruh Building. This is because those construction projects will not be able to start until the new building is constructed and staff can be relocated into it. Additionally, to the extent that the delay affects the timeline for renovating the existing Resources Building and Unruh Building, it would also affect projects that are connected to those projects—such as the EDD Headquarters and Annex Buildings and the Energy Commission Building.

Existing SPIF Process Is Problematic For Future Projects

The $1.3 billion provided in the 2016–17 budget package was deposited into the continuously appropriated SPIF. The administration indicates that it plans to continue to use the SPIF process for future projects. However, as we discuss below, the rationale for using the SPIF process—that it would result in a faster project timeline and thus reduce costs—is not compelling, particularly for future projects. We also find that the continuous appropriation that is part of the existing SPIF process greatly reduces legislative oversight and that the notification process, while helpful, does not serve as an adequate replacement for the traditional capital outlay process for future projects. We further find that the weaknesses of the SPIF process are magnified with the addition of more funds.

Rationale for Continuous Appropriation Is Not Compelling. The administration’s rationale for the Legislature providing continuous appropriations for projects is that it will enable the state to complete projects faster, since project schedules will not have to align with the state budget process. The administration maintains that a continuous appropriation allows it to proceed with projects without having to wait for legislative approval at the typical points in a project’s life cycle. The administration further assumes that the longer time frame that could result from relying on the typical capital outlay approval process would result in additional project costs. However, the traditional capital budget process need not delay projects significantly. Notably, a key reason for the administration to have a well–developed strategy is that it would enable the state to coordinate the timing of projects with the budget process, thus avoiding any potential delays. Even if projects were not well–coordinated with the budget process, any delay would likely not be substantial given the typical multiyear timeline for large construction projects. We also anticipate that any such delays would not necessarily increase the real costs of projects. This is because, in recent years, the cost of constructing buildings has increased at roughly the same rate as overall inflation.

Rationale Is Particularly Weak For Future Projects. We find that the administration’s rationale for using a continuous appropriation—that the traditional budget process could create potential project delays and associated costs—is particularly weak for most future projects in the strategy. This is because the timing of the construction of future projects is largely dictated by the timing of the completion of the construction of the projects before them. For example, the renovation of the Bateson Building cannot begin before its staff are moved into the new Resources Building. Under the administration’s strategy, it does not anticipate beginning any initial planning activities for the renovation of the Bateson Building, including any work to select consultants to develop performance criteria, until 2018–19. However, if the administration was concerned about the timing of this project, it could start these activities in 2017–18. This would provide the administration with an additional fiscal year to complete them without affecting the construction timeline.

Continued Use of Current SPIF Process Greatly Reduces Legislative Oversight. We also find that the use of the SPIF process for future projects would greatly reduce legislative oversight. In place of the annual budget process, the SPIF requires quarterly reports and various notifications. We find that the reports and notifications are likely to include some important information to help the Legislature monitor projects at key project phases. In our view, however, the process does not serve as adequate replacement for the typical capital outlay budget process, for a few reasons.

- First, the notification process through the JLBC provides the Legislature with significantly less time to review proposed projects than the approval process through the traditional capital outlay process. The JLBC review period is as little as 20 days in some cases—far less than is necessary to complete a thorough evaluation of a large project.

- Second, the notification process is less transparent to the public than the traditional capital outlay process, which includes public hearings that enable the Legislature to ask questions and the public to provide input. For this reason, the JLBC notification process is typically reserved for minor, midyear changes to the budget rather than substantial actions such as the approval of new projects costing many millions of dollars.

- Third, the notification process does not require the same level of information that would typically be required for a capital outlay budget change proposal (COBCP). For example, a COBCP typically includes a narrative describing the justification for the project. It also includes an evaluation of the other available alternatives. This type of information is not a required part of the SPIF notifications, but would be valuable to assist the Legislature in determining whether the administration’s proposals make sense.

Weaknesses of SPIF Magnified With Additional Funding. The weaknesses of the existing SPIF process would be magnified if additional funds are added to the account in the future. The statute governing the SPIF provides the administration with the discretion to establish and fund new projects with JLBC notification rather than legislative approval. As the monies in the fund increase, the potential for the administration to exercise this authority to fund new projects not envisioned by the Legislature also increases. For this reason, it is particularly problematic to add funding to the SPIF with its current authority for additional projects in the future.

Back to the TopLAO Recommendations

Based on our assessment, we make several recommendations to help guide the Legislature as it faces key decisions points related to the administration’s strategy:

- First, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information and a robust analysis that will allow the Legislature to assess if the strategy represents the best approach available to address aging state office buildings.

- Second, we recommend that the Legislature closely monitor the expenditure of the $1.3 billion approved in 2016–17 through the use of hearings at key points in project life cycles. Such hearings would help improve transparency and ensure that funds are spent consistent with legislative priorities.

- Third, we recommend that any future funding provided for state office building projects go through the typical budget process rather than a continuous appropriation under the current SPIF process. Doing so would make it easier for the Legislature to provide robust oversight over the administration’s ambitious strategy.

Require More Analysis of Strategy Prior to Providing Additional Funds

The Legislature is likely to receive proposals requesting additional funding—likely totaling over a billion dollars—for state office building projects in Sacramento in the coming years. In order to help the Legislature in determining the approach it prefers to take to address these infrastructure issues, we recommend directing the administration to provide an analysis of the overall strategy that includes key information.

Require Analysis of Costs and Benefits. Before considering any new projects, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide information on the costs and benefits of the overall strategy. This information should include the anticipated costs of the strategy broken out by individual project. A complete understanding of these costs—even if it is rough—is critical to enabling the Legislature to assess whether it is comfortable with the financial commitment that is associated with implementing the strategy as a whole. Furthermore, this information would inform decisions on individual future projects. This is because, given the interrelated nature of the individual projects in the strategy, legislative decisions on one project affect the feasibility of other projects.

Additionally, the information provided by the administration should include the articulation of the benefits associated with the strategy and a quantification of these benefits, as feasible. Some of the potential benefits of the strategy may be more easily quantified than others. For example, some benefits—such as reduced lease costs—are readily quantifiable. Estimates of the magnitude of these benefits should be included in the administration’s analysis. Other benefits—such as the value of having modern office spaces for state employees—may be very challenging if not impossible to fully quantify. In these cases, the administration’s analysis should provide a clear description of the value of the benefits provided and why they are important to justifying the strategy. Our analysis suggests that the administration’s strategy does not appear to make sense based solely on one of the benefits that is most easy to quantify—the reduced lease costs. Thus, it is particularly important for the administration to clearly articulate any other benefits provided by the strategy in order to make the case that it is worthwhile.

Require Analysis of Alternatives. We also recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide an analysis of available alternatives to its strategy. We think that the administration’s analysis should explore two main types of alternatives: (1) different mixes of buildings to be addressed and (2) other available approaches to address these buildings.

First, the administration’s analysis should evaluate alternative strategies that include a different mix of buildings to address. Figure 10 provides some examples of the types of alternative options that the administration could evaluate. We also include rough cost estimates of these potential options. These estimates are intended to provide a sense of the general scale of the potential choices available to the Legislature. (We note that these estimates are imprecise given the lack of scope and cost information provided by the administration on these projects.) These options highlight that there are likely to be trade–offs in pursuing a different mix of buildings. For example, the Legislature could choose not to fund any additional projects beyond those already approved. While this option would reduce construction costs by roughly $1.4 billion compared to the administration’s strategy, it would also fail to directly address any of the existing state buildings identified in the Sacramento Assessment Report. Alternatively, in addition to the three priority projects, the Legislature could choose to renovate some combination of the highest–need buildings, as identified in the Sacramento Assessment Report. For example, it could choose to renovate the three highest–need buildings in Sacramento, consistent with Chapter 451, or to address all the buildings identified in “poor” condition in the Sacramento Assessment Report. These options would both result in lower costs than the strategy proposed by the administration, but they also would total less new and renovated state–owned office space. While not shown in the figure, another alternative would be to include high–need buildings in other parts of the state as identified in the Statewide Assessment Report.

Figure 10

Estimated Costs of Some Possible Optionsa

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Buildings |

Sacramento |

Entire |

Possible Options |

||

|

Priority Projects |

Priority |

Priority |

|||

|

Proposed in Sequencing Plan |

|||||

|

Build new Resources Buildingb |

N/A |

$600 |

$600 |

$600 |

$600 |

|

Replace O Street Building |

N/A |

225 |

225 |

225 |

225 |

|

Renovate or replace Capitol Annex/LOB II |

N/A |

580 |

580 |

580 |

580 |

|

Replace Printing Plantc |

N/A |

955 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Renovate Resources Building |

1 |

230 |

— |

230 |

230 |

|

Renovate Bateson Building |

6 |

45 |

— |

— |

45 |

|

Renovate Unruh Building |

5 |

25 |

— |

— |

25 |

|

Renovate BOE Building |

12 |

55 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Renovate EDD Headquarters and Annex |

4, 8 |

75 |

— |

— |

75 |

|

Renovate Blue Anchor Building |

9 |

5 |

— |

— |

5 |

|

Renovate CEC Building |

10 |

10 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Not Proposed in Sequencing Plan |

— |

— |

|||

|

Renovate Personnel |

2 |

— |

— |

15 |

15 |

|

Renovate Bonderson |

3 |

— |

— |

20 |

20 |

|

Renovate Justice |

7 |

— |

— |

— |

40 |

|

Total Estimated Costs |

$2,805 |

$1,405 |

$1,670 |

$1,860 |

|

|

Total amount of new square footage, in thousandsd |

1,900 |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

|

Total amount of renovated square footage, in thousandsd |

2,000 |

— |

700 |

2,000 |

|

|

aAssumes renovations will include the scope of work shown as the ten–year capital needs in the Assessment Report. About 50 percent was added to the estimates of the cost of this work to account for expenses not included in this report. bIncludes $70 million in additional costs compared to the original rough estimate due to revised project delivery method and building location. cEstimate is based on conceptual cost estimate provided in the Office Planning Study. dCapitol Annex/LOB II not listed in either new or renovated space, since plan for building is unknown. LOB = Legislative Office Building; BOE = Board of Equalization; EDD = Employment Development Department; and CEC = California Energy Commission. |

|||||

Second, the administration should evaluate whether other available approaches to addressing these office buildings—such as buying existing privately owned office buildings or leasing additional space—are more cost–effective. For example, as described previously, the estimated costs of building new office buildings are high compared to the costs of the state’s existing leases and compared to the cost of purchasing existing buildings. While there would likely be benefits to constructing a new building rather than purchasing or leasing an existing building—such as additional flexibility in designing the building—these benefits might be outweighed in some cases by the additional costs. Thus, it is important for the administration to provide this analysis to demonstrate that its preferred approach to addressing buildings is the best available one.

Closely Monitor Expenditure of $1.3 Billion Already Approved

The scope and details of the two state building projects initially approved—the new Resources Building and O Street Building—are not well defined. Furthermore, because the projects are funded out of the SPIF, there is a greater chance that these projects could change over time without legislative approval. Accordingly, it is important for the Legislature to maintain close oversight over these projects to ensure that funds are spent in a manner consistent with its priorities. As such, we recommend that the Legislature hold public hearings—such as through the relevant budget subcommittees—at critical project decision points.

Hold Hearings When Project Scope and Cost Are Defined. We recommend that the Legislature hold a hearing when the scope and cost of each of the two new state building projects are defined. Generally, scope and cost of capital outlay projects are defined when the Legislature initially approves the project—for example, when the Legislature approves funding for performance criteria. However, unlike typical capital outlay projects, the scope and cost of these projects were not well defined in the administration’s proposal. Instead, the administration is currently in the process of solidifying their scope and cost, a process that we expect will be completed in early 2017. At that time, we expect the administration to notify the JLBC.

When the JLBC receives these notifications, we recommend that the Legislature conduct a thorough review of them, including holding a public hearing. While a public hearing upon the establishment of scope and cost of these projects would not serve all the purposes of the traditional budget process, it would provide some of the benefits of this process. For example, it would provide the Legislature with an opportunity to review details of the projects in a public setting. Such a hearing would also enable the Legislature to address questions to the administration to ensure that it is comfortable with them. This public process is particularly important because based on our discussions with the administration, we expect that there will be notable changes to aspects of the projects—such as location and costs—compared to what the Legislature envisioned when the projects were funded. Additionally, the public process is especially important because, based on the preliminary cost estimates that are available, these are expensive projects. Thus, these hearings would provide the Legislature with an opportunity to better understand the reasons for their apparent high costs and ensure that it is still comfortable moving forward with them.

Hold Hearings When Project Scope and Cost Change Substantially. We also recommend that the Legislature hold a hearing when the scope or cost of the two state office building projects change significantly. Specifically, given the size of these projects, we recommend that the Legislature consider holding a hearing if the cost of an individual project changes by more than 10 percent. (We note that, although there is some potential ambiguity in the law, the administration has indicated to us that it interprets the law to require a new legislative appropriation if a SPIF–funded project has total cost increases exceeding 20 percent.) Similarly, we recommend a hearing if key details about one of these projects change—such as its location or proposed use. These hearings would provide the Legislature with a valuable opportunity to ask the administration to articulate the reasons for changes in scope or cost. Without such hearings, the administration could make substantial changes to these projects without the public review process provided by a hearing.

Avoid Use of Current SPIF Process for Any New Projects

Rely on Traditional Budget Process. If the administration pursues its strategy as currently envisioned, the Legislature should expect to receive additional funding requests as soon as 2017–18. The administration indicates that it anticipates continuing to use the SPIF process—including its continuous appropriation—to fund additional projects. We strongly recommend that the Legislature avoid putting additional funding into a continuously appropriated fund, including the SPIF as currently structured. Instead, if the Legislature is comfortable providing additional funding for state office buildings in the Sacramento area in future years, we recommend that it approve them through the state budget process. The budget process provides the Legislature with the ability to use its constitutionally granted appropriation authority to ensure that state funds are directed to its highest priorities and are spent with adequate legislative oversight and accountability. Furthermore, while the administration’s rationale is that this approach is necessary to expedite projects, this argument generally is not compelling for future projects. Such projects are more heavily constrained by the progress of the recently approved projects than by the time required for approval of proposals through the traditional budget process.

Require Detailed Analysis and Information in Future Proposals. Consistent with the typical process, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to provide individual COBCPs, or equivalent, for any future projects. Each of these COBCPs should provide the type of information that is typically included in such proposals, including:

- A description of the project scope and its justification.

- The estimated project cost (by project phase), funding source, timeline, and delivery approach.

- An evaluation of project alternatives and a description of why the proposed approach was selected over the alternatives.

This information should be sufficiently detailed and reliable to enable the Legislature to understand what it would be funding and to evaluate the merits of the projects. This information is critical in order to enable the Legislature to evaluate whether cost estimates are reasonable and that each of the proposed projects is the best way to accomplish the goals associated with that building. This information would also facilitate the future oversight of any projects that are subsequently approved by setting clear expectations of the initial project costs, scope, and other critical project details. We note that the administration failed to provide this type of detailed information on each of the three initial projects it proposed in 2016–17. This failure made it more difficult for the Legislature to assess these projects.

Conclusion

We expect that in the near future the administration will come forward with requests for more funding—likely totaling more than $1 billion—for additional state office buildings. We anticipate that, absent clear direction from the Legislature, the administration may submit proposals that—like its proposal in 2016–17—fail to include key information and analyses. Additionally, we expect that the administration might continue to propose using the SPIF process, which reduces legislative oversight and is particularly flawed for future projects. Thus, we strongly encourage the Legislature to provide clear direction to the administration that it expects more complete information and a robust analysis to justify any future project or funding proposals. Furthermore, we also strongly encourage the Legislature to make it clear to the administration that any future funding that is provided should be subject to a process that facilitates more robust legislative oversight and control than the SPIF process. Finally, since the SPIF process governs the funding for the state building projects funded in 2016–17, we recommend that the Legislature use other tools at its disposal—such as legislative hearings—to closely monitor them. While these tools are not a replacement for the traditional budget process, they can provide some additional legislative oversight that can help hold the administration accountable and ensure that funds are used consistent with legislative priorities.