May 17, 2019

The 2019-20 May Revision

Multiyear Budget Outlook

- Near‑Term Budget Condition

- Longer‑Term Budget Condition

- Preparing the Budget for the Future

- CONCLUSION

Executive Summary

This report presents our office’s independent assessment of the condition of the state General Fund budget through 2022‑23 assuming the economy continues to grow and all of the Governor’s May Revision spending proposals are adopted.

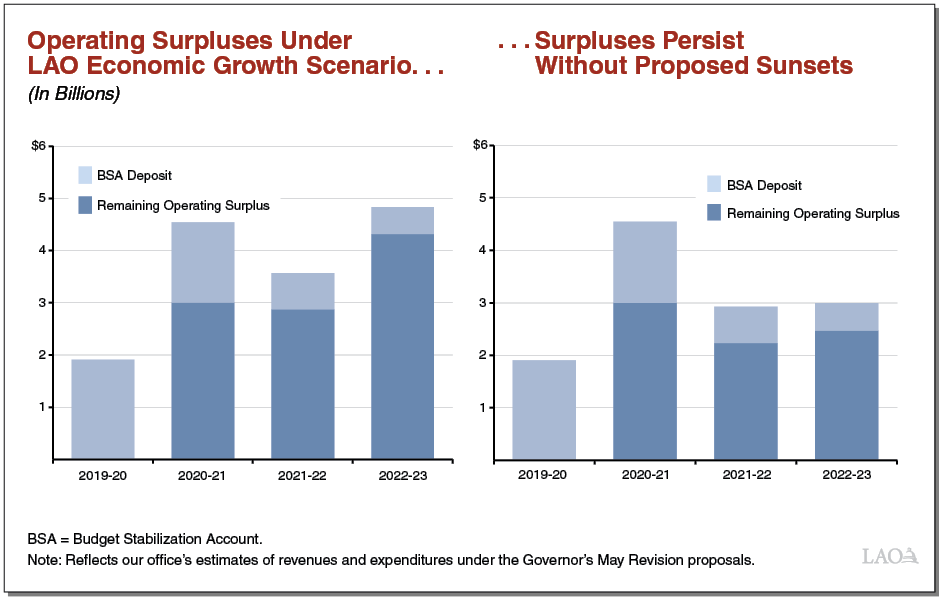

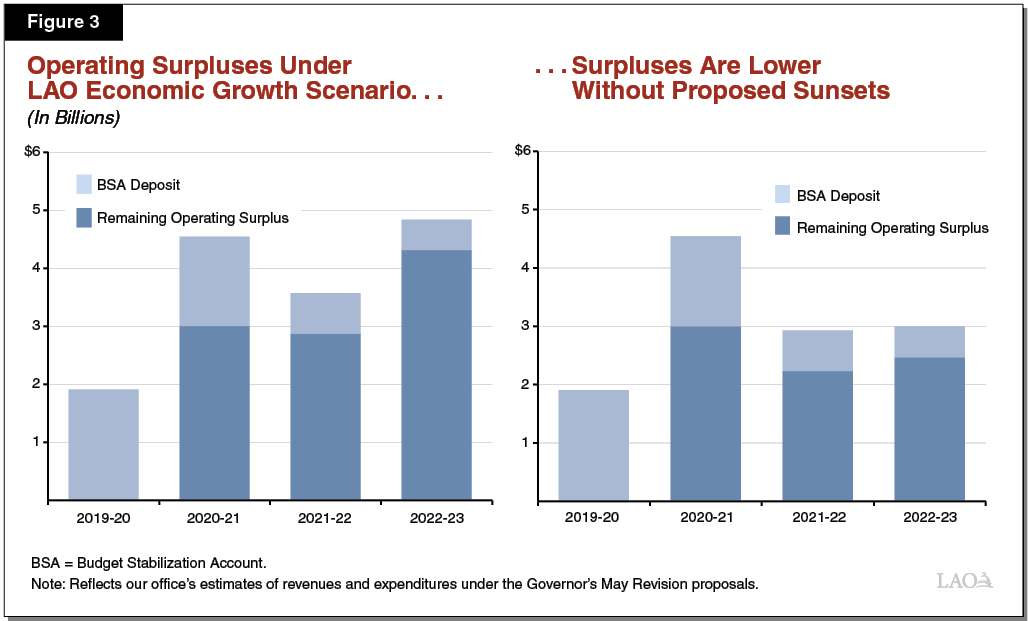

Multiyear Budget Condition Is Positive. Under our multiyear outlook assumptions, the state budget has the capacity to pay for the Governor’s May Revision proposals and still has an operating surplus—which could be available to respond to unanticipated cost increases, build additional reserves, or make additional commitments. In fact, although the Governor proposes to “sunset” four major categories of program expenditures (such as provider rate increases in Medi‑Cal), our outlook suggests this action is not necessary to balance the budget. The figure below shows our projections of the budget’s operating surpluses with and without the Governor’s proposed sunsets. As the right side of the figure shows, under our revenue assumptions, operating surpluses persist even without the Governor’s proposed sunsets.

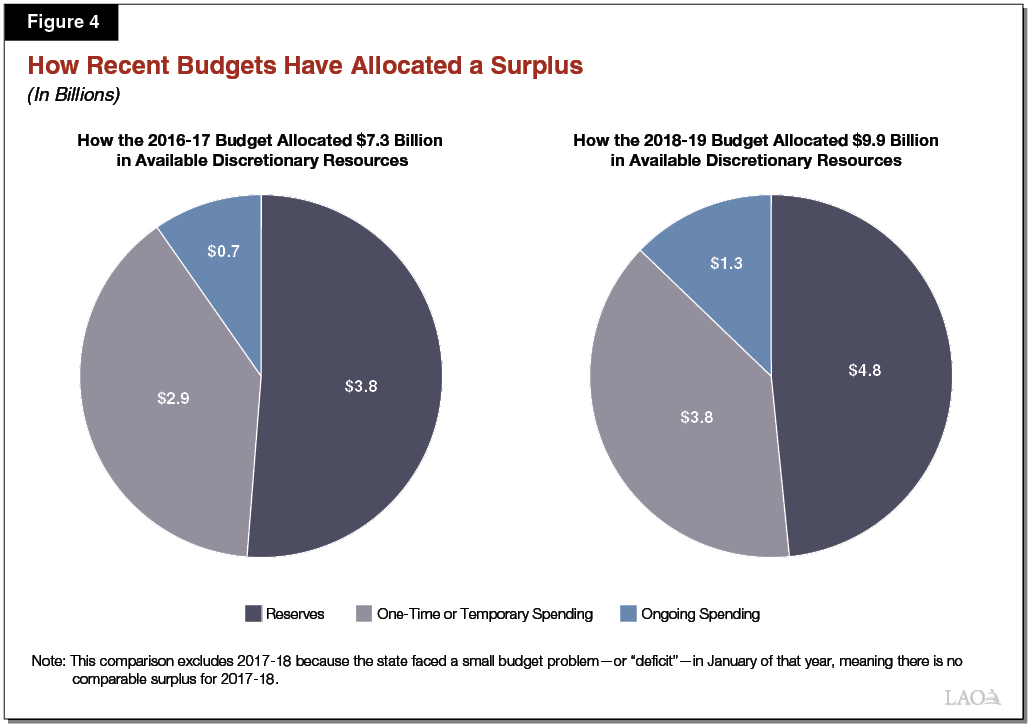

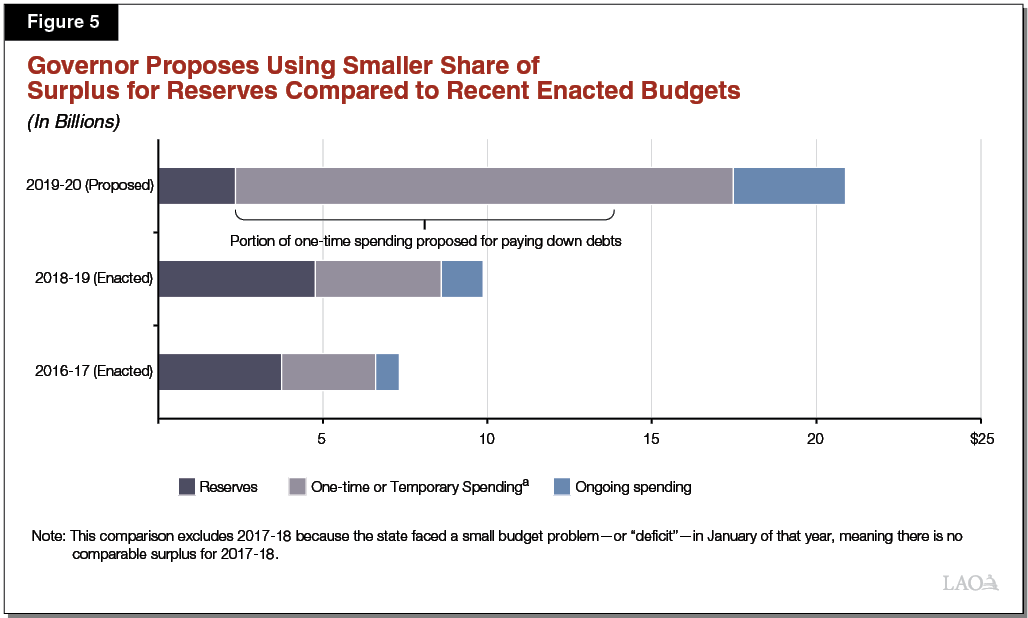

Recent Budgets Focused on Building Reserves to Prepare for Future. In this report, we also analyze how well the Governor’s proposed budget prepares the state for future budgetary challenges—such as a recession. Recently enacted budgets have focused on building reserves as the primary strategy for preparing the budget for the future. They also have focused new discretionary spending proposals on one‑time, rather than ongoing, purposes. For example, in 2016‑17 and 2018‑19, the Legislature committed roughly half of the budget’s estimated surplus to increasing reserves. These budgets also committed a relatively small amount of new resources to ongoing spending. (This comparison excludes 2017‑18 because the state faced a small budget problem—or a “deficit”—in January of that year, meaning there was no comparable surplus for 2017‑18.)

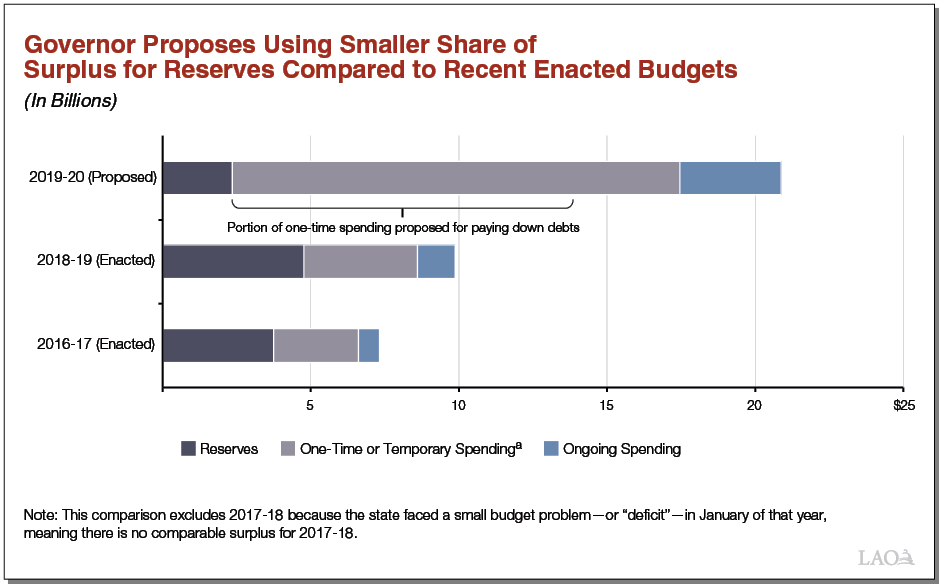

Governor Places a Much Lower Emphasis on Building More Discretionary Reserves . . . In his proposed budget, the Governor’s revenue estimates indicate the state has a much larger available surplus to allocate compared to recent years. In both dollar and percentage terms, however, the Governor allocates much less of this surplus to building more discretionary reserves. Moreover, the Governor proposes allocating more available funding, in dollar terms, to new ongoing spending commitments. Specifically, as shown in the figure below, he proposes new ongoing spending of $3.4 billion (growing to $4.4 billion upon full implementation), compared to recent levels of $300 million and $1.3 billion in 2016‑17 and 2018‑19.

. . . And Instead Focuses on Paying Down State Debt. The Governor has stated that one of the primary objectives of his budget is to better prepare the state for a future challenge. To accomplish this, the Governor proposes to pay down state debts (which he refers to as a plan to build budget resilience). In particular, the Governor proposes allocating $9.5 billion of available discretionary resources to repaying state debts, including paying down pension liabilities, repaying outstanding loans to state special funds, undoing two budgetary deferrals, and paying obligations to schools and community colleges.

We Recommend the Legislature Maintain Its Recent Practice to Focus on Reserves. We agree with the Governor that the state’s remarkable surplus represents a unique opportunity to prepare the budget for the future. We also agree that using a portion of the surplus to address some of the state’s outstanding debt is prudent. However, we think the state’s plan for responding to a recession should focus—first and foremost—on building budget reserves. Building reserves is the most reliable and effective method for preparing the budget for a downturn. As such, we recommend the Legislature dedicate a larger portion of the surplus to discretionary reserves, as it has done in recent budgets.

This report presents our office’s independent assessment of the condition of the state General Fund budget through 2022‑23 under the Governor’s May Revision proposals. As is our practice at the May Revision, our assessment is based on: (1) one set of economic conditions (in this outlook, a continued growth scenario), (2) implementation of the Governor’s policy proposals, and (3) our own estimates of the future costs of state programs.

The first section of this report analyzes the near‑term budget condition under our revenue estimates and those of the administration. The second section analyses how the budget would fare under our estimates of revenues and expenditures assuming the economy continues to grow. The third section analyzes the extent to which the Governor’s May Revision proposals prepare the budget for a future budget problem.

Near‑Term Budget Condition

Under Our Estimates, 2019‑20 Ends With Nearly $1 Billion Higher Surplus. Figure 1 compares our office’s bottom‑line estimates of the budget’s condition to the administration’s estimates. Relative to the Department of Finance (DOF), we estimate 2019‑20 would end with $961 million more in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). The SFEU—the state’s discretionary reserve—represents the difference between state spending and state resources for a given fiscal year. The key reason our SFEU balance is higher is that our estimates of revenues are somewhat higher than the administration’s estimates. Consequently, under our assessment, the Legislature has a roughly $22 billion surplus available to allocate in 2019‑20, rather than the roughly $21 billion surplus under the administration’s estimates.

Figure 1

Comparing LAO and DOF Near‑Term General Fund Budget Outlooks

(In Millions)

|

LAO |

DOF |

||||

|

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Proposed |

2018‑19 Revised |

2019‑20 Proposed |

||

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$11,213 |

$6,561 |

$11,419 |

$6,224 |

|

|

Revenues and transfers |

138,388 |

144,478 |

138,046 |

143,839 |

|

|

Expenditures |

143,039 |

147,048 |

143,241 |

147,033 |

|

|

Ending fund balance |

$6,561 |

$3,991 |

$6,224 |

$3,031 |

|

|

Encumbrances |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

$1,385 |

|

|

SFEU balance |

5,176 |

2,606 |

4,839 |

1,646 |

|

|

DOF = Department of Finance and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|||||

Total Reserves. Figure 2 compares how the state’s total reserve balances would differ under the LAO and DOF estimates of revenues (assuming all of the Governor’s May Revision proposals are in place). Total reserve balances under our office’s revenue estimates would be about $20.2 billion at the end of 2019‑20, compared to $19.5 billion under the Governor’s estimates. This difference is the net result of four factors:

- Slightly Lower Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) Balance. The BSA is the state’s general purpose constitutional reserve. Proposition 2 (2014) outlines a set of complicated formulas that require minimum deposits into the BSA each year. (The formulas also require the state to pay down a certain amount of eligible debts each year.) In addition to these required deposits, the state is permitted to make additional optional deposits into the account. Under our estimates of revenues—particularly lower estimates of capital gains revenues—the BSA balance would be nearly $150 million lower at the end of 2019‑20 than under the Governor’s revenue estimates.

- Higher SFEU Balance. The state’s other primary general purpose reserve account is the SFEU. Unlike the BSA, which has restrictions on withdrawals, the Legislature has wide discretion to use the funds in the SFEU. As described above, under our revenue estimates, the SFEU balance would be about $1 billion higher at the end of 2019‑20 than it would be under the Governor’s estimates.

- Unchanged Safety Net Reserve. The 2018‑19 budget created the Safety Net Reserve to set aside funds for future costs of two programs—California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) and Medi‑Cal—in the event of a recession. The Governor proposes depositing $700 million into this account to bring its total balance to $900 million.

- Slightly Lower School Reserve. In addition to creating new rules for depositing funds into the BSA, Proposition 2 established a specific statewide school reserve (the Public School System Stabilization Account). This school reserve is governed by a separate set of formulas. Under our estimates of revenues, the deposit into the school reserve would be $76 million lower than under the administration’s estimates.

Figure 2

Comparing Total Reserve Balances Under LAO and DOF Budget Outlooks

(In Millions)

|

Reserves at End of 2019‑20 |

LAO |

DOF |

|

BSA balance |

$16,372 |

$16,515 |

|

SFEU balance |

2,606 |

1,646 |

|

Safety Net Reserve balance |

900 |

900 |

|

School reserve balance |

313 |

389 |

|

Total Reserves |

$20,191 |

$19,450 |

|

DOF = Department of Finance; BSA = Budget Stabilization Account; and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

||

Longer‑Term Budget Condition

To evaluate the effect of the administration’s policy proposals on the state’s fiscal condition over the next few years, both our office and the administration produce a multiyear budget outlook in May. Both of these outlooks assume the economy continues to grow, although we have differences in our respective approaches to and conclusions about what that growth could look like. In this section, we present our longer‑term budget outlook under our set of economic assumptions and compare our estimates to the administration’s forecast.

Operating Surpluses Assuming Economic Growth. The left side of Figure 3 displays our office’s outlook for the General Fund. The top part of each bar shows our projection of the annual BSA deposit. The bottom part of each bar shows the annual operating surplus (the amount by which projected revenues exceed expenditures or the annual change in the SFEU). This indicates that—under this set of economic assumptions—the state’s budget has the capacity to pay for the Governor’s May Revision proposals and still have a couple billions of dollars annually to build additional reserves or make additional commitments. These surpluses are significantly larger than those displayed by the administration in its multiyear estimates. The administration’s estimates of the operating surplus are in the hundreds of millions of dollars. There are two major factors that drive these differences: (1) our office’s higher estimates of revenues (particularly in the out years) and (2) our office’s lower estimates of spending on health and human services programs.

Surpluses Are Lower Assuming No Sunsets. Importantly, the left side of Figure 3 includes the Governor’s proposal to sunset four major categories of program expenditures in 2021 and 2022. The Governor’s sunset proposals are to: (1) use Proposition 56 (2016) funding for General Fund cost increases in Medi‑Cal, (2) make the restoration of In‑Home Supportive Services service hours temporary, (3) make new insurance subsidies temporary, and (4) make new supplemental rate increases for developmental services providers temporary. Absent these sunsets, a structural deficit would emerge under his policy plans and revenue estimates. The right side of Figure 3 shows the budget’s multiyear condition, under our estimates, if the Legislature chose not to implement these sunsets. As the figure shows, our estimates of the budget’s condition suggest the state has the capacity to implement the Governor’s May Revision proposals without sun setting these program expenditures.

Positive General Fund Situation Reflects a Number of Factors. This budgetary outlook is positive. It is the result of three important factors and assumptions:

- Continued Economic and Revenue Growth. The budget surpluses displayed in Figure 3 rely on a specific economic scenario. That economic scenario assumes U.S. gross domestic product grows at nearly 2 percent annually over the next five years, wages and salaries continue to grow above 3 percent annually, the stock market remains mostly flat, and many other conditions persist. Under our models, this fairly positive economic picture would result in moderate revenue growth over the period.

- Lower Growth in General Fund Spending on Schools and Community Colleges. Under the rules of Proposition 98 (1988), the state must provide a minimum funding level to schools and community colleges each year. This minimum level is met through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. In the past couple of years, we have revised our projections of growth for the General Fund share of the minimum funding level downward. For example, in our May 2017 outlook, we estimated General Fund growth would average 3.6 percent per year over the outlook period. Our May 2018 outlook, we estimated annual growth of 3.4 percent. This May, we estimate General Fund spending on schools and community colleges would grow 2.9 percent over the outlook period. This primarily reflects slower projected growth in General Fund revenue and faster growth in local property tax revenue compared to previous outlooks. This slower growth in school spending contributes to the budget’s better condition. (Overall growth in funding for schools and community colleges—including local property tax revenues—would be higher than 3 percent under our outlook.)

- Lower Growth in Medi‑Cal. The Governor’s proposed budgets in both January and May reflected significantly lower Medi‑Cal costs than had been anticipated by recent budgets and administration estimates. Under our outlook, a portion of this baseline adjustment results in lower ongoing costs to the Medi‑Cal program. This improves the budget’s multiyear condition by hundreds of millions of dollars relative to our previous estimates.

LAO Comments

Budget Outlook Continues to Be Positive. Our office produces a multiyear assessment of the state’s budget condition twice annually. For several years, these outlooks have indicated the budget picture is positive and this assessment continues to hold today. As this analysis has shown, the Governor’s approach to focus new spending commitments on one‑time purposes, rather than ongoing ones, contributes to a budget picture that reflects operating surpluses assuming the economy continues to grow. That said, the economic picture can change quickly. If the growth of California’s economy slows in the coming years, the budget picture will be very different from what we have displayed here.

State Faces a Number of Cost Pressures Not Reflected in This Analysis. Our multiyear budget analyses often emphasize the risks the state could face in a recession or economic slowdown. However, even under the precise economic conditions assumed in this outlook, we think the budget could face unexpected cost increases (and lower surpluses) than we are currently displaying. There are a number of reasons this could occur, including:

- Disaster(s). Our outlook assumes the state faces no major disaster in the coming years, such as an earthquake or catastrophic wildfire, similar to the Camp, Woolsey, and Hill fires that occurred in November 2018 or the Tubbs wildfire in October 2017. Such an occurrence could occur, however, and the associated state costs would be hundreds of millions or even a billion dollars.

- Unexpected Cost Increases. This outlook provides the Legislature with our best estimate of future costs based on currently available data. We do not build in an assumption about unexpected costs. In recent years, however, unexpected costs have occurred and been sizable. For example, the 2017‑18 budget reflected a $1.8 billion unexpected cost increase in the Medi‑Cal program due to a one‑time retroactive payment of drug rebates and an administrative error. (That said, the state also sometimes revises costs downward—as the administration did with Medi‑Cal costs this year—and such downward revisions would result in a budget condition that is better than what we have currently displayed.)

Our Multiyear Outlook Does Not Reflect Intent for Future Augmentations. The operating surpluses in this section reflect no additional budget commitments after 2019‑20. That is, we assume no additional program or benefit expansions occur after this budget is passed. In some cases, however, the Legislature has signaled that it intends to make additional programmatic commitments. For example, the 2018‑19 budget package included statutory intent language stating the Legislature’s goal to increase CalWORKs grants to ensure participating families’ incomes are above 50 percent of the federal poverty level by 2020‑21. The Governor also has stated he intends to propose further program augmentations. For example, in this budget, the Governor has noted his goal for providing universal preschool to all children in California and has proposed funding to develop a plan to achieve this goal (including revenue options). Future augmentations (if not fully offset by new revenues) would reduce the operating surpluses we display here.

Recommend the Legislature Maintain Some Operating Surplus Capacity for Future Years. The Governor’s May Revision proposes new ongoing spending while treating some existing programmatic commitments and cost pressures—such as provider payment increases in Medi‑Cal and developmental services—as temporary. Given these programs have been priorities of the Legislature in recent years, we do not think the Legislature should take this approach. In building its multiyear plans and assumptions, we recommend the Legislature use estimates of ongoing spending that reflect the full cost pressures associated with the budget’s commitments—in this case, assuming the sunsets are not enacted. Moreover, given the various unexpected cost increases the state could face in the future, we suggest the Legislature build positive operating surpluses into its planning estimates. Given these considerations, we recommend the Legislature adopt a final budget package with a level of ongoing spending that is no higher than currently proposed by the Governor (in 2019‑20 this level of ongoing spending is $3.4 billion—projected to grow to $4.4 billion—upon full implementation).

Preparing the Budget for the Future

Throughout this budget process—as in recent years—there has been significant discussion about whether the state budget is prepared to weather a recession. In our previous work (Building Reserves to Prepare for a Recession and The 2019‑20 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook), we estimated the state would need between $20 billion and $40 billion in reserves to avoid major spending reductions, tax increases, or cost shifts in a recession. The Governor has stated that one of the primary objectives of his budget is to better prepare the state for such a future challenge. To do this, the administration uses a substantial portion of the expected surplus to pay down state debts and liabilities. In February, we offered the Legislature alternative debt and liability payment options that would provide greater General Fund benefits. (More information about our alternative options can be found in The 2019‑20: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities.) However, in that report we did not assess whether the Governor’s approach accomplishes this stated objective. In this section, we analyze how well the Governor’s budget proposals prepare the budget to weather a recession.

How Recent Budgets Have Prepared for Future Challenges

Recent Budgets Have Focused on Building Reserves to Prepare for the Future . . . Budget reserves are monies set aside for future use, like a household’s savings account that is dedicated to emergencies. Reserves help insulate the budget from temporary shortfalls, delaying or mitigating the need for the Legislature to make difficult choices, including spending reductions and tax increases. In recent years, when significant resources have been available, the Legislature has focused on building more reserves to prepare the budget for the future.

. . . And Focused New Commitments on One‑Time Purposes. One‑time programmatic spending also benefits the budget in the event of a budget problem. One‑time spending has one of the benefits of reserves (it reduces the size of a future budget problem) but not the other benefit of reserves (holding money available to spend on programs in the future). In recent budgets, the Legislature has focused new spending commitments on one‑time purposes and generally limited the amount of new increases in ongoing spending.

Figure 4 shows how recent budgets have allocated available discretionary resources (the “surplus”). In 2016‑17, we estimate the Legislature had $7.3 billion available for new discretionary spending increases and in 2018‑19 nearly $10 billion available. In each of these budgets, the Legislature committed roughly half of the surplus to increasing reserves. These budgets also committed a relatively small amount of new resources to ongoing spending—$300 million and $1.2 billion, respectively. (This comparison excludes 2017‑18 because the state faced a small budget problem—or a deficit—in January of that year, meaning there is no comparable surplus for 2017‑18.)

The Governor’s New Approach to Preparing the Budget

Governor Places a Much Lower Emphasis on Building More Discretionary Reserves . . . We estimate the Governor’s May Revision had a significant budget surplus of nearly $21 billion. Figure 5 shows how the Governor allocates that surplus and compares the proposed allocation to recent enacted budgets. As the figure shows, in both numerical and proportional terms, the Governor allocates a much smaller share of discretionary resources to reserves than previous budgets enacted. In dollar terms, the Governor proposes much more one‑time and ongoing spending. That said, within one‑time or temporary spending, the Governor allocates $9.5 billion to paying down state debts (which we discuss in greater detail later in this brief).

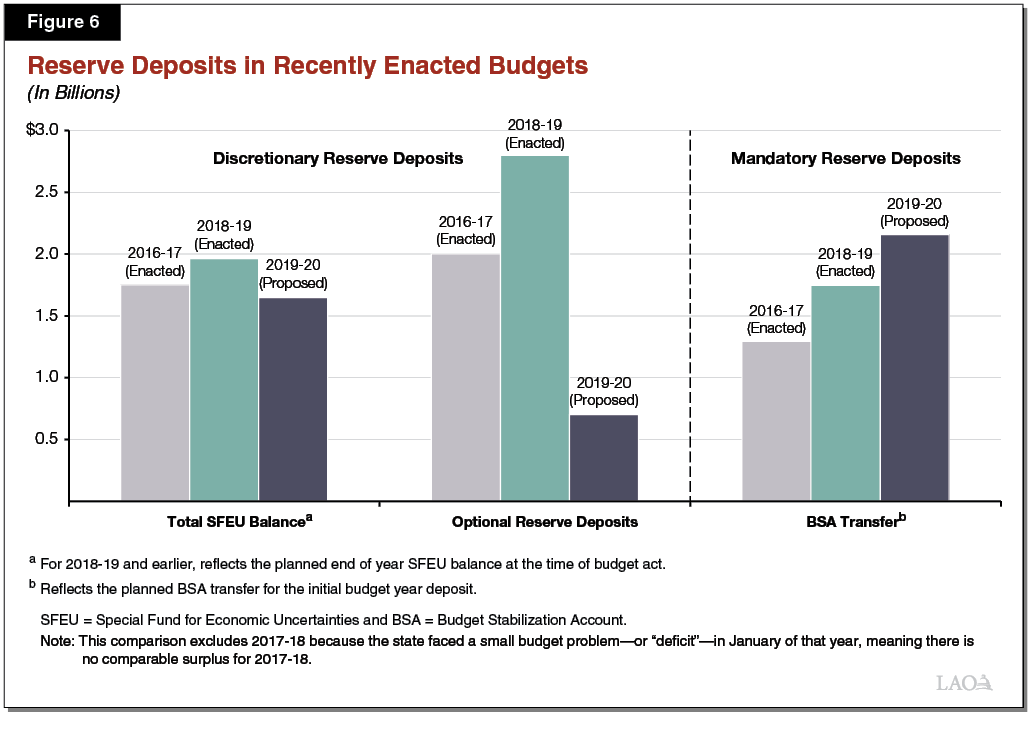

. . . But Required Reserve Deposits Are Somewhat Higher. In Figures 4 and 5, discretionary reserves have two components: the total balance in the SFEU and optional reserve deposits (which includes optional deposits into the BSA, as well as any deposit into the Safety Net Reserve). Mandatory reserve deposits (under the rules of Proposition 2), however, also increase total state reserves. (Generally, mandatory reserve deposits are higher when revenues estimated for the upcoming fiscal year are higher.) Figure 6 compares recent budgets’ constitutionally required reserve deposits to the 2019‑20 May Revision estimate. As the figure shows, while the Governor is proposing significantly less in discretionary reserve deposits for 2019‑20 compared to other recent budgets, the Governor’s budget does include a slightly larger mandatory reserve deposit. This is largely because the Governor anticipates more revenues for the upcoming fiscal year, particularly revenues from capital gains.

Instead of Building Discretionary Reserves, Governor Focuses on Paying Down State Debt. The Governor proposes to pay down state debts to improve the budget’s condition (which he refers to as a plan to build budget resilience). In particular, the Governor proposes allocating $9.5 billion of available discretionary resources to repaying state debts. The Governor also allocates $2.2 billion in constitutionally required debt payments under the rules of Proposition 2. While Proposition 2 determines the minimum amount that must be spent on debt payments, the measure gives the Legislature flexibility on how to allocate those payments (among eligible uses). Figure 7 summarizes how the administration proposes allocating these payments. (In addition to the payments described above, the 2019‑20 budget will repay additional billions of dollars in debt, such as debt service on bonds, on a mandatory basis. We do not include these annual, mandatory debt repayments in our description of the Governor’s debt package.)

Figure 7

Governor’s Debt and Liability Repayment Proposals in 2019‑20 May Revision

(In Millions)

|

Liability Type . . . |

Liability Owed by . . . |

Discretionary |

Proposition 2 Debt Payments (Mandatory) |

|

Retirement Liabilities |

|||

|

CalPERS |

State |

$3,000 |

— |

|

CalSTRS |

State |

— |

$1,117 |

|

CalSTRS |

School districts |

2,300 |

— |

|

OPEB |

State |

— |

260 |

|

UCRP |

Universities |

25 |

— |

|

Budgetary Liabilities |

|||

|

Pension deferral |

State |

707 |

— |

|

Payroll deferral |

State |

973 |

— |

|

Special fund loans |

State |

1,283 |

— |

|

Weight fee loans |

State |

886 |

— |

|

Settle up |

State |

297 |

390 |

|

CalPERS borrowing plan |

State |

— |

390 |

|

Totals |

$9,471 |

$2,157 |

|

|

OPEB = other post‑employment benefits and UCRP = University of California Retirement Plan. |

|||

Proposed Debt Package Largely the Same as January. The only new debt proposal in the May Revision is to pay $25 million toward the University of California Retirement Plan unfunded liability. While the amount and composition—Proposition 2 or discretionary—of other debt proposals changed somewhat under the May Revision, the major proposals are largely unchanged. We described these proposals in depth in our report The 2019‑20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities. We also summarize them—and their potential benefits—in the nearby box.

Major Features of The Governor’s Debt Package

Key Components of the Governor’s Debt Package. The Governor’s debt repayment package has a number of notable features. In particular it includes payments toward:

- CalPERS. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is the state employee pension system. The state of California has full responsibility for CalPERS’ $59 billion unfunded liability. The Governor proposes paying down an additional $3 billion of this unfunded liability. We estimate the state would save about $90 million annually beginning in 2020‑21 as a result. (These savings would grow over time.)

- CalSTRS. The California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) is the pension system for California’s teachers. Under state law, the state has responsibility for roughly one‑third of CalSTRS’ $104 billion unfunded liability and school districts and community colleges share responsibility for the other two‑thirds of the liability. The Governor proposes using $2.3 billion to pay down a share of the districts’ CalSTRS unfunded liability and $1.1 billion to pay down the state’s share of the liability. CalSTRS estimates the districts’ payments would reduce their costs by a total of $6.7 billion over the next three decades—reducing districts’ annual contributions by about 0.4 percent of payroll. Whether or not the state would achieve savings over the next few decades from paying down a portion of the state’s share of the unfunded liability is less certain.

- Pension and Payroll Deferrals. To address budgetary shortfalls in the past, the state has made various accounting adjustments to push costs into different fiscal years, providing a significant temporary budgetary benefit. These are called deferrals. The Governor proposes reversing two of the state’s outstanding deferrals: (1) a payroll deferral, in which the state employee payroll for June is dated July 1, and (2) a pension deferral, in which the fourth‑quarter payment to CalPERS due at the end of June is paid in early July. The cost to undo these actions is $1.7 billion.

- Special Fund Loans. As one of many actions it took in the 2000s to address its budget problems, the state loaned amounts to the General Fund from other state accounts, particularly special funds. The state has been repaying these loans since the end of the Great Recession and the Governor proposes repaying all remaining outstanding special fund loans at a cost of $2.2 billion. (This figure includes “weight fee loans” as a type of special fund loan.)

- Settle Up. A settle‑up obligation to schools and community colleges is created when their constitutional minimum spending requirement ends up higher than estimated in the enacted budget. The Governor proposes repaying all outstanding settle up in the 2019‑20 budget.

LAO Comments

Compared to recent budgets, which have focused on building reserves as the primary mechanism to prepare the budget for the future, the Governor emphasizes paying down debts. We summarize our assessment of whether these proposals better prepare the budget for addressing a future budget problem in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Summary of Assessments of Governor’s Debt Package

|

Governor’s Proposal |

Key Budgetary Advantage for State or Other Entity |

Does This Proposal Allow the State to Address a Future Budget Problem? |

|

Pays down CalPERS unfunded liability |

Saves state money over the long term |

Yes—Provides significant budgetary savings. Recommend Legislature approve this payment. |

|

Pays down CalSTRS school district and UCRP unfunded liability |

Saves districts and UC money over the long term |

Somewhat—Could improve districts’ and universities’ financial health, making these entities better prepared for reductions in General Fund spending. |

|

Pays down CalSTRS state unfunded liability |

Saves state money over the long term |

Somewhat—Likely will achieve savings, but has a lower chance of doing so over the next few decades compared to CalPERS payment. |

|

Undoes budgetary deferrals |

Improves state budgetary and accounting practices |

Yes—Allows state to take action again in the future; however, building more reserves would be a more efficient way to achieve the same goal. |

|

Repays outstanding special fund loans |

In some cases, allows fund to expand services for fee payers |

Somewhat—Might allow state to borrow again, but funds’ future capacity for lending might be more constrained than in the past. |

|

Repays outstanding settle up |

Supports additional school spending this year |

No—This action removes the option to provide schools more funding during a fiscal downturn. |

|

UCRP = University of California Retirement Plan. |

||

Some of the Governor’s Approach Makes Sense . . . Some of the proposed debt repayments improve the budget’s bottom‑line condition and we believe those are good ideas. Most notably, the proposed supplemental payment to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System will reduce the system’s unfunded liability and result in significant state savings over time, which has benefits for the state budget. (Our recent analysis on this proposal recommended modifications, but we recommend the Legislature approve this payment in its final budget package.) While the supplemental California State Teachers’ Retirement System payment for districts’ unfunded liability does not directly lower state costs, reducing schools’ costs could put their budgets in better shape to withstand future challenges. Given the state’s interest in school districts’ financial health, we do not have concerns with this proposal.

. . . However, Much of the Governor’s Approach Does Not Help the Budget Address a Future Problem. Whereas paying down unfunded pension liabilities better positions the state for addressing a future budget problem, other proposals do not have that effect. In particular, repaying special fund loans and undoing two budgetary deferrals only have benefit if the state anticipates using these borrowing mechanisms to address a budget problem again in the future. This approach could be problematic, however, as special fund borrowing could result in negative impacts to those programs. While the state has used these practices in past recessions, we believe they should be a measure of last resort. Moreover, as described in the nearby box, the state’s capacity to borrow from special funds might be more constrained than their balances would indicate.

How Much of Special Fund Balances Are Available for Borrowing?

State Has Repaid Billions of Dollars in Special Fund Loans to the General Fund. During the dot‑com bust and Great Recession, the state borrowed from special funds to help address the General Fund’s budget problems. Since the end of the Great Recession, the state has repaid billions of dollars of these special fund loans. In recent years the state also has built significant reserve balances in its special funds—as of the Governor’s budget, the projected balance of special fund reserves was $17 billion at the end of 2019‑20.

To What Extent Are These Special Fund Balances Borrowable? While special fund reserves in aggregate are significant, not all of this amount is borrowable from a legal perspective or advisable to borrow from a policy perspective. Based on our preliminary analysis, there are several reasons for this:

- Some Funds Are Not Legally Borrowable. In recent years, constitutional amendments have prohibited the state from borrowing from most transportation accounts. Major transportation accounts represent over $5 billion of the special funds’ total reserve balance of $17 billion.

- Some Funds Have Built Large Balances to Maintain Operations. In some cases, special funds face volatile or declining revenue sources. These funds have built large balances in order to smooth expenditures in future years when revenues may be lower than today. For example, the Healthcare Treatment Fund, with a balance of $300 million, receives revenues from taxes on tobacco products. Because tobacco consumption (and associated revenue) is expected to continue to decline in the coming years, the fund has a significant balance in order to maintain current expenditure levels.

- Some Funds Have Been Allocated, but Not Yet Encumbered. The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) receives auction revenues from the state’s cap‑and‑trade program and reflects a fund balance of about $1.3 billion. Under both our and the administration’s estimates of the Governor’s expenditure proposals for the fund, however, GGRF would have an unencumbered balance of less than $100 million available at the end of 2019‑20.

- Some Funds Faces Structural Deficits. Many funds have positive reserve balances, but nonetheless face structural deficits. For example, as of the Governor’s Budget, the Motor Vehicle Account had a balance of over $300 million, but faces a structural deficit for future years. Likewise, the Immediate and Critical Needs Account (ICNA), which was created to finance the construction of a number of new courts, has a balance of about $300 million, but might not have sufficient resources in the future to fund its originally planned projects. (In fact, a key reason ICNA faces these structural issues is that a significant portion of ICNA resources were transferred to the General Fund during the fiscal downturn.) Borrowing from these funds again is possible, but would further exacerbate their existing budgetary problems.

Paying off the state’s remaining settle up to schools also does not help the state address a future budget problem. Settle‑up payments do not reduce costs in the long term, nor do they create more cash reserves for the future. Instead, paying remaining settle up now reduces the solutions available to the state to mitigate reductions in school funding in the event of a fiscal downturn. Rather than pay off the remaining settle up this year, the state could wait to provide the funding in a year when schools are facing little, or no, increase in funding. Taking this approach could enable schools to maintain ongoing programs that otherwise would be reduced.

We Recommend the Legislature Maintain Its Recent Practice to Focus on Reserves. We agree with the Governor that the state’s remarkable surplus represents a unique opportunity to prepare the budget for the future. We also agree that using a portion of the surplus to address some of the state’s outstanding debt is prudent. However, we think the state’s plan for responding to a recession should focus—first and foremost—on building budget reserves. Building reserves is the most reliable and effective method for preparing the budget for a downturn. As such, we recommend the Legislature dedicate a larger portion of the surplus to discretionary reserves, as it has done in recent budgets.

Conclusion

The Governor’s January budget proposal and May Revision have reflected a somewhat different approach to fiscal management compared to recently enacted budgets. First, relative to recent budgets, the Governor proposes a higher level of ongoing spending. Specifically, the Governor proposes new, ongoing discretionary spending of $3.4 billion in 2019‑20 (excluding the sunsets described below). This is much higher than recently enacted levels of $300 million and $1.3 billion.

Coupled with these new ongoing spending proposals, the Governor suggests making some ongoing expenditures temporary in order to address a budget problem that would otherwise materialize under his administration’s own multiyear estimates. Under our estimates of revenues and expenditures, however, these sunsets would not be necessary. Given these programs reflect ongoing services and have been recent legislative priorities, we do not think the Legislature should take this approach.

Second, the Governor proposes a shift in the state’s approach to preparing for the future, namely a recession, but also other unforeseen challenges, such as a natural disaster. While past budgets emphasized building more reserves as the primary means of preparation, the Governor emphasizes paying down debts. We believe some of the Governor’s debt package has merit, but also note that the state has not yet reached the lower end of our advised range of reserves. Given the extraordinary level of resources now available, we think the Legislature should stay on its current course, continuing to focus on building reserves as the primary mechanism for preparing the budget for the future.

The Governor’s budget reflects an extraordinary surplus of $22 billion, but it is the Legislature’s constitutional authority to ultimately determine the allocation of that surplus in the enacted budget. As the Legislature sets about its final budget deliberations, we have the following recommendations. First, we recommend the Legislature adopt a final budget package with a level of new ongoing spending that is no higher than the level currently proposed by the Governor. Second, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s plan to make ongoing augmentations temporary in order to address the multiyear budget condition. Rather, we think the state budget should accurately reflect the true ongoing costs associated with its budget year commitments. Finally, we recommend the Legislature build more reserves than currently proposed by the Governor.