Recently, the Legislative Analyst’s Office released its report, The 2020-21 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook amid data indicating that the economic expansion, now in its 11th year, is still intact. The Fiscal Outlook paints a positive picture of California’s fiscal condition. Assuming that current law and policies are held constant, we estimate that at the end of 2020-21, the state’s discretionary reserve balance would reach nearly $7 billion. We refer to this projected balance as a surplus because it is the amount of anticipated discretionary resources above what we project will be needed to fund existing commitments and legal obligations. Estimating the state’s anticipated surplus is important because it represents an upper limit on the amount of new commitments the Legislature can afford with existing resources. (Conversely, when the Fiscal Outlook anticipates a deficit, our estimate reflects the budget problem the Legislature will confront in the coming budget cycle.) Whether the state likely faces a surplus or deficit in the coming year is necessary, but is insufficient information for crafting a prudent budget. For that, additional context about the state’s fiscal structure, the economic backdrop, and other potential risks and uncertainties is crucial.

First, to recap some key takeaways from our Fiscal Outlook:

Prior to any new spending commitments, we estimate that California’s General Fund is on track for a $6.7 billion surplus in 2020-21.

The ongoing portion of the surplus is considerably smaller, averaging $3 billion through our outlook horizon which extends to 2023-24.

The state’s budget reserves, which are already at record levels, continue to increase under our baseline growth scenario. In 2020-21, the Budget Stabilization Account balance reaches $18.3 billion with total budget reserves—inclusive of our estimated surplus—approaching $26 billion.

Despite these large surpluses and reserves, our central recommendation is that the Legislature limit its new ongoing commitments to approximately $1 billion or less in the upcoming budget.

Given our estimate for a nearly $7 billion surplus for 2020-21, it is reasonable to ask how we arrived at a recommended limit of $1 billion in new ongoing spending. A majority of the difference lies in the distinction between the ongoing and one-time components of the surplus. The former is an annual amount that allows lawmakers to make recurring expenses, while the latter is available in one year to be spent or saved. Since our surplus estimate comprises $3 billion in ongoing and $4 billion in one-time components, best practice dictates an upper limit of $3 billion for new ongoing purposes. Worthy considerations for the other $4 billion include increasing discretionary reserves or other one-time expenditures, such as supplemental pension payments. Lawmakers could preserve fiscal flexibility by scheduling any such one-time payments to occur late in the fiscal year, contingent on the state’s budget condition at that time. This still leaves a question relating to the $3 billion ongoing surplus and why we recommend against budgeting no more than about $1 billion of it to new ongoing commitments.

One reason for limiting the amount of new commitments is the potential for a recession. But even putting aside, for a moment, the possibility of a recession, we identified in the Fiscal Outlook several risks and uncertainties to the state’s budget condition that lie outside the Legislature’s control. Examples include federal decisions (such as if the federal government does not approve the state’s tax on managed care organizations, which generates additional federal funding) and the risk of major natural disasters (wildfires in particular). The additional cost associated with such outcomes could easily reduce the state’s ongoing surplus to around $1 billion. Given that these risks—and arguably others—are hardly implausible, we recommend that the Legislature take them into account as they allocate the anticipated surplus in the upcoming budget.

Furthermore, in the real world, of course, the risk of a recession cannot be assumed away. Although the impending threat of a recession has seemed to wax and wane throughout 2019, we suspect that downside risk to the economy is now elevated compared with prior years’ outlooks. The good news is that the state’s current budget reserves and annual operating surpluses (where revenues exceed expenditures) provide enough of a fiscal cushion to cover the revenue shortfalls of our recession scenario.

Several caveats are warranted, however. First, the recession in our hypothetical “stress test” is only average in severity and duration compared with the dozen recessions that have occurred since World War II. A more severe or longer lasting recession would inflict more fiscal strain on the state than what we assumed. Second, even if the recession were relatively mild, nothing precludes it from occurring simultaneous with the higher costs related to the aforementioned risks and uncertainties. It is not difficult to envision how these noneconomic-related risks combined with the effects of a recession could render the state’s reserves as inadequate. Finally, in order to “weather” the recession, we assume the Legislature funds K-14 education at the minimum amount allowed by Proposition 98. While this is consistent with the Legislature’s past practice, it would involve at least one multibillion dollar year-over-year funding reduction to the schools, a difficult policy decision for the Legislature.

Putting California’s Current Fiscal Position Into Perspective

Nothing mentioned above should detract from the historic nature of California’s current budget condition. Indeed, far from taking them for granted as the ordinary results of an economic upswing, the state’s budget reserves and operating surpluses are, as we have previously characterized them, historically extraordinary. A combination of fiscal policy choices and broader economic performance has been integral to the state’s budgetary gains in recent years.

Consider how the following variables aligned in such a way to facilitate the state’s improved fiscal condition:

An extended ten year-plus—now a record in duration—period of uninterrupted economic growth;

A more than tripling of stock market valuations since 2009;

Voter-approved tax increases (Proposition 30 in 2012 and Proposition 55 in 2016), the timing of which coincided with an economic expansion and bull market for equities;

Executive, legislative, and voter support for establishing a stronger constitutional budget reserve formula (Proposition 2 in 2014); and,

Consistent allocation of above-budget revenues throughout a period of accelerating economic growth to one-time expenditures, including to build higher discretionary reserve balances.

If some of these conditions are not in place after the next recession, it will be more difficult for the state to rebuild its reserves to current levels following a drawdown. Assuming the Legislature perceives current reserve levels as prudent—and not easily replicated—then it may wish to add a layer of fiscal protection to them. To that end, we recommend that the Legislature retain a portion of the ongoing surplus in its discretionary reserve as a first line of defense. In a nascent recession, this would allow the initial wave of any revenue shortfalls to erode the anticipated operating surplus before encroaching on the state’s constitutional reserve balance. Relative to a budget that allocates the entire anticipated surplus to ongoing purposes, this approach would preserve a larger share of the state’s accumulated constitutional budget reserve.

California’s Economic Advantage Is Not Without Risk

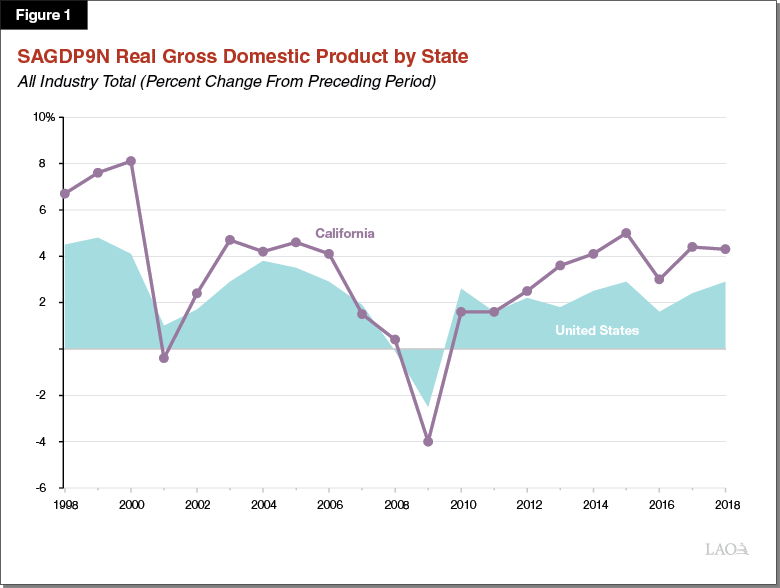

A final consideration relates to the performance of California’s economy compared with that of the nation. California’s economy has outperformed the national economy in the good times but it has also fared worse than average in recessions. This relationship has held throughout the current expansion, with California’s economy growing at a faster clip than the national economy each year from 2012 through 2018.

If history is a guide, however, California could again suffer a proportionately sharper downturn when the national economy next goes into a recession. Moreover, certain policy changes in recent years likely exacerbate the state’s propensity for fiscal volatility. General Fund reliance on the personal income tax—and thus on capital gains-related income taxes in particular—has increased. Consequently, from a fiscal standpoint, the state could see revenue shortfalls commensurate with or greater than past recessions, especially if it were accompanied by a stock market correction. Recognizing how California’s economic cyclicality and fiscal profile interact—along with the other risks we have mentioned—we recommend a cautious approach to increasing the state’s ongoing commitments.