LAO Contact

February 1, 2021

Evaluating State Economic Stimulus Proposals

- Introduction

- State Capacity for Stimulus More Limited Than Federal Government

- Assessing Economic Stimulus Proposals

- Considerations Specific to the COVID‑19 Pandemic

- Appendix

Executive Summary

The state can seek to encourage short‑term economic activity through spending increases or tax reduction programs that get people employed, increase consumer spending, and spur businesses to invest. During economic slowdowns, like the one the state currently is experiencing, interest in these types of economic stimulus programs is heightened. In this report, we offer the Legislature guidance on how to evaluate stimulus proposals.

Recognize Limitations on State Funded Stimulus

Unlike the federal government—which can run a deficit to pay for fiscal stimulus—the state must balance fiscal stimulus with other one‑time and ongoing spending priorities.

Ask Key Questions to Assess Stimulus Proposals

✓ What is the source of funding?

✓ Does the proposal have other strong policy justifications?

✓ How does the proposal interact with other federal, state, and local programs?

✓ How might the expected benefits and costs be overstated or understated?

✓ Will the benefits be realized when they are needed?

✓ How might the benefits be distributed?

Incorporate These Elements for More Effective Stimulus

Given the state’s spending constraints, economic stimulus is most likely to be effective if new programs:

✓ Are funded using federal funds, a state General Fund surplus, or proceeds from previously authorized bonds.

✓ Efficiently advance other legislative policy objectives.

✓ Complement (and do not duplicate) other federal or state programs.

✓ Can be implemented quickly.

✓ Are well designed and clearly targeted.

✓ Avoid making existing inequities worse.

Introduction

COVID‑19 Pandemic Severely Disrupted California’s Economy. The beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic in early 2020 disrupted California’s economy in an unprecedented way. In the spring, the economy abruptly ground to a halt: millions of Californians lost their jobs, businesses closed, and consumers deeply curtailed spending.

Rapid Rebound Results in Incomplete, Uneven Economic Recovery. Almost as quickly, Californians began to adjust to the realities of the pandemic. With this adjustment, and accompanying major federal actions to support the economy, came a rapid rebound in economic activity over the summer and into the fall. This recovery, however, has been incomplete and remarkably uneven. In particular:

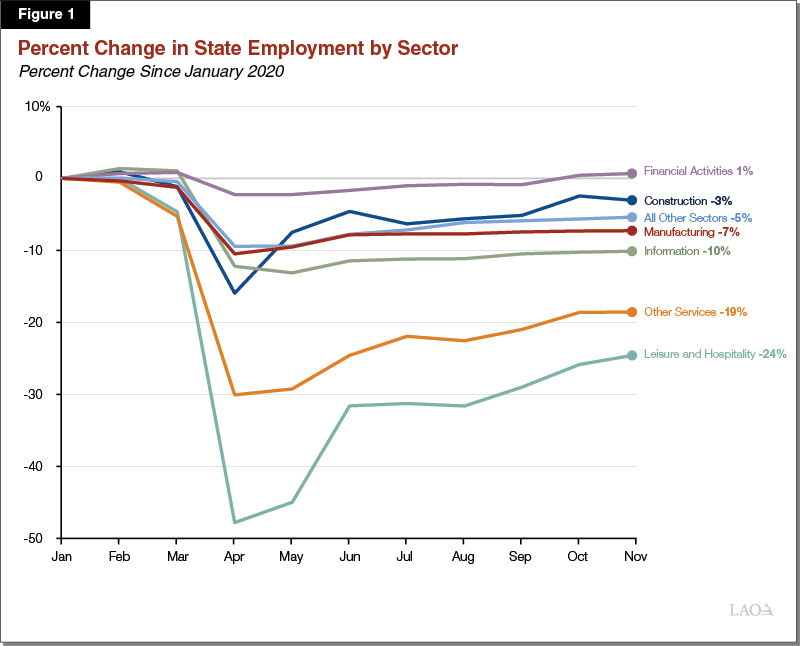

- Some Sectors of the Economy Recovering More Slowly Than Others. COVID‑19 has had the biggest effect on close‑contact jobs and industries related to tourism and discretionary in‑person services. Employment in industries such as personal care services; accommodations and food services; motion picture and video; and arts, entertainment, and recreation experienced relatively large declines in employment and are recovering much more slowly than most other industries in California. Figure 1 shows how employment losses varied across sectors of the state economy. In all industries, however, unemployment was concentrated among low‑income workers while high‑income workers were largely unaffected.

- Women, Younger Adult, and Latino Workers Disproportionately Affected. COVID‑19‑related job losses have affected Latinos, younger adults, and women disproportionately, as these Californians are overrepresented—relative to their share of the populations—in the industries that were most affected. In addition, the closures of schools and childcare providers during the pandemic also appears to have disproportionately affected workers with children, especially women. The labor force participation rates among women with children declined significantly more than among men during 2020.

Our December 2020 Economy & Tax post, COVID‑19 and the Labor Market: Which Workers Have Been Hardest Hit by the Pandemic? describes the unequal economic and employment effects of the pandemic.

Full Economic Recovery Will Not Be Possible Until Public Health Emergency Has Been Resolved. The COVID‑19 pandemic is ongoing and, while vaccines are being distributed and administered, their widespread distribution is still some months away. Reaching a full recovery will be a slow process that will depend heavily on continued progress on management and treatment of the virus. In the meantime, the state continues to face significant economic uncertainty.

Fiscal Stimulus Can Aid Economic Recovery. State government can provide financial relief and encourage short‑term economic activity using fiscal stimulus. Fiscal stimulus consists of spending increases or tax reduction programs that get people employed, increase consumer spending, and spur businesses to invest. (Stimulus also can refer to other government actions such as regulatory changes that affect the demand for goods and services by the private sector, but this is not the focus of this report.) While these short‑term benefits can help speed the state’s economic recovery from a recession, the state also must balance fiscal stimulus with other one‑time and ongoing spending priorities. As we describe in our November 2020 report, Update on COVID‑19 Spending in California, the state has already taken some important actions to mitigate the adverse economic and health consequences of COVID‑19. The 2021‑22 Governor’s Budget also proposes several new spending and tax reduction programs that could mitigate the economic consequences of the pandemic and stimulate the state economy. These include new programs to provide fiscal relief to low‑income Californians and small businesses impacted by the pandemic, funding for infrastructure, and other new spending that could stimulate the economy. We analyze these proposals in separate publications available on our website.

Beyond the proposals in the Governor’s budget, we anticipate that the Legislature will be asked to consider the economic effects of new proposals over the coming months and years. This report provides (1) context for understanding the state’s capacity for economic stimulus; (2) guidance for assessing legislative or spending proposals based on their potential economic benefits, in addition to any other policy considerations; and (3) specific comments about economic stimulus in the context of the current economic and public health situation. In the Appendix of this report, we summarize other work our office has done in the past on evaluating the economic effects of state programs and policies.

State Capacity for Stimulus More Limited Than Federal Government

In this section, we discuss the roles of and recent actions taken by the federal and state governments to stimulate the economy.

Federal Government Has Significant Capacity for Economic Stimulus

- Federal Government Has Few Restrictions on Spending. The federal budget is able to operate at a deficit. In 2019, the federal budget deficit was around 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

- Federal Response to COVID‑19 Has Increased Size of Deficit. The federal budget deficit, as a percent of GDP, grew by more than 10 percentage points in 2020 (to around 15 percent) due to the federal government’s response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency. The U.S. Congress passed a major fiscal stimulus bill in March 2020 that enhanced unemployment insurance benefits, provided broad‑based cash assistance to individuals and businesses, and provided financial assistance to states and local governments. We estimate that individuals, businesses, and public agencies in California received more than $300 billion in financial assistance from the federal government in response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency in 2020. This financial assistance at the onset of the recession likely mitigated its negative economic effects for several months. Individuals, businesses, and public agencies also will receive billions of dollars in additional financial assistance during 2021 from another major economic stimulus package that Congress enacted at the end of 2020. (Further federal action is possible in coming months.)

- Federal Reserve System (the Fed) and Monetary Policy. The Fed may use monetary policy to stimulate economic growth. Monetary policy includes influencing interest rates and increasing the supply of money. In response to COVID‑19, the Fed has committed to keeping interest rates very low for an extended period of time. Congress also provided the Fed with additional authority to make extraordinary loans directly to businesses and to state and local governments. States have no role in monetary policy.

State Fiscal Capacity for Stimulus Spending Is Limited

- California Must Balance Budget. The state has less capacity for fiscal stimulus than the federal government primarily because the State Constitution requires enactment of a balanced state budget. There are only limited ways—bonds and savings from prior years—for the state government to spend more than it collects in revenue in any given year.

- Capacity for State Fiscal Policy Is Relatively Small. The state’s budget is much smaller than the federal government’s, which also limits the capacity for fiscal stimulus. California’s entire budget is about 6 percent of the state’s economic output. In comparison, the federal government spending increase in 2020 alone was more than 10 percent of the U.S. economy, as mentioned above. Without a constitutional balanced budget requirement, federal spending can increase significantly to provide impactful fiscal stimulus—as it did this year. Moreover, during periods of economic hardship, the state budget typically shrinks as lower incomes and lower spending reduce the tax base.

Assessing Economic Stimulus Proposals

In this section, we first explain generally how economic stimulus can work and why it often is challenging to accurately estimate the economic benefits. We then provide a framework for assessing the merits of economic stimulus proposals.

How Does Economic Stimulus Work?

Economic stimulus may be accomplished through either spending increases or tax reductions. The state sometimes adopts a new program with economic stimulus as the primary objective. However, many state programs with another intended objective may also have economic benefits. An economic stimulus proposal can have a variety of economic effects. On the positive side, economic stimulus can create new economic activity directly, as well as indirectly through so‑called “multiplier effects.” On the negative side, are so‑called “opportunity costs.” The overall economic effect of a stimulus proposal depends on the balance of these positive and negative factors.

- Direct Economic Effects. New state spending may (1) directly increase state employment; (2) increase state purchases of goods and services from the private sector; and/or (3) increase private‑sector employment, spending, and investment. Similarly, a tax reduction also may increase employment, spending, and investment in the private sector by increasing residents’ after‑tax incomes. These direct economic effects can increase the overall size of the state’s economy provided they do not “crowd out” other economic activity, as we discuss below.

- Multiplier Effects. As employment, spending, and investment increase, other indirect economic effects also occur within the state’s economy. The resulting increase in personal and business income circulates throughout the economy, as households and businesses purchase other goods and services. Ultimately, the total increase in the number of jobs, income, and economic output of the state’s economy may be somewhat bigger than the amount of new spending—this is called an economic multiplier. An increase in public spending may also “crowd in” (encourage) or crowd out (displace) some private‑sector spending and investment. Such private sector responses further affect the size of the multiplier.

- Opportunity Costs. When funds are used for economic stimulus, they are not available for alternative programs or spending. These alternatives also would provide economic benefits, which are lost when funding is allocated elsewhere. The forgone benefits from unfunded alternative uses are known as opportunity costs. In other words, opportunity costs are the answer to the question: What other state programs would have been funded if the stimulus program had not been created and what would have been the benefits of those other programs? The size of opportunity costs in large part depends on the source of funding, as we discuss in more detail below.

Quantifying Economic Benefits Often Difficult

- Studies to Estimate Economic Benefits Often Have Many Limitations... Quantifying all of the potential economic effects of a change in policy is difficult and subject to a significant amount of uncertainty. In rare cases, gauging the potential benefits of a proposal by looking at economic research of the historical experiences with similar programs may be possible. In many cases, however, such high‑quality information is not available. In place of learning from the past, other types of economic studies attempt to use models to estimate economic benefits under certain specific assumptions, which may or may not be accurate. This approach has many significant drawbacks. Importantly, assessing these models’ reliability can be difficult because there often are major practical barriers to checking the assumptions and predictions against real‑world outcomes. For example, differentiating a particular policy’s effect on employment from the variety of other complex factors that drive employment changes is very difficult. Further, some economic studies omit significant economic considerations, such as the opportunity costs. As a result, relying solely on the results of estimated jobs or economic output from these types of studies to evaluate a stimulus proposal likely will lead to an incomplete assessment.

- …But Studies Still Can Provide Useful Information. Even if economic studies face significant challenges in quantifying economic benefits, these studies often provide other useful information. For example, studies often describe the intended policy outcomes and qualitatively discuss the potential economic effects of proposals. These studies also can highlight important but less obvious economic effects of spending or tax proposals. For example, an economic impact study of a transportation investment might estimate the economic benefits of improved mobility and safety, in addition to the direct economic benefits of the engineering and construction activities. This information can help policymakers evaluate the stimulus proposal for its other potential policy benefits.

Key Questions to Ask When Evaluating Economic Stimulus Proposals

Given the challenges of quantifying economic benefits, we recommend asking six key questions, summarized in Figure 2, to make a more complete assessment of the merits of economic stimulus proposals.

Figure 2

Key Questions to Ask When Evaluating Economic Stimulus Proposals

|

|

|

|

|

|

What Is the Source of Funding?

- Fiscal Stimulus Spending Generally Requires Making Trade‑Offs. Funds used for stimulus spending will be unavailable for other government programs and services. The extent to which the Legislature must trade spending on fiscal stimulus with other priorities depends on the source of the funds.

- Trade‑Off Heightened for New State Spending. New General Fund spending can require reductions elsewhere in the budget because of constitutional restrictions against deficit spending. While new stimulus programs or tax incentives could have economic benefits, cuts to funding for other state programs or tax increases can have negative economic effects. This trade‑off means that, in many cases, it is difficult to be confident that any increase in economic activity from a new stimulus program would not be more than offset by the corresponding decrease in economic activity from less funding to another state program.

- Federal Funds Require Fewer Trade‑Offs. Federal funds, if available, are the best source of funding for fiscal stimulus because they may not require a reduction in other state spending. The potential economic benefits of federally funded stimulus depend on the specific circumstances of the federal programs providing funds. For example, there typically are restrictions on how the funding can be used. Additionally, many federal programs require the state provide matching funds. Federally funded fiscal stimulus allows the state to increase economic activity while making fewer trade‑offs among other spending priorities. As a general guideline, the Legislature should maximize the use of federal funds.

- Borrowing Trades More Spending Now for Less Spending Later. Issuing bonds allows the state to significantly increase current spending, but there are three important trade‑offs to consider.

- Voter‑Approval Required. The state uses bonds primarily to pay for the planning, construction, and renovation of infrastructure projects such as bridges, dams, prisons, parks, schools, and office buildings. The state is prohibited from borrowing money to finance state operations. In most cases, voters must approve new bond authority before the state can raise the funds—a process that increases the amount of time between when the need for stimulus is identified and when any new spending may occur.

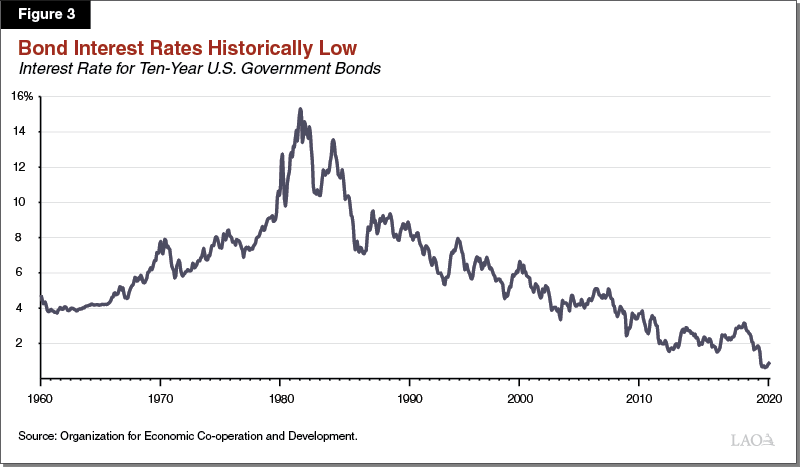

- Increases Total Cost. Interest payments on the borrowed funds somewhat increases the total cost of bond‑funded projects. The additional cost often is offset by having the benefits of those projects much sooner than had they been funded conventionally. When interest rates are high, the cost of borrowing also is high, but the opposite is true when interest rates are low. The actual cost of borrowing depends on the market conditions when the bonds are sold. Figure 3 shows that interest rates for ten‑year U.S. treasury bonds, which are closely related to changes in state borrowing costs, currently are at historic lows.

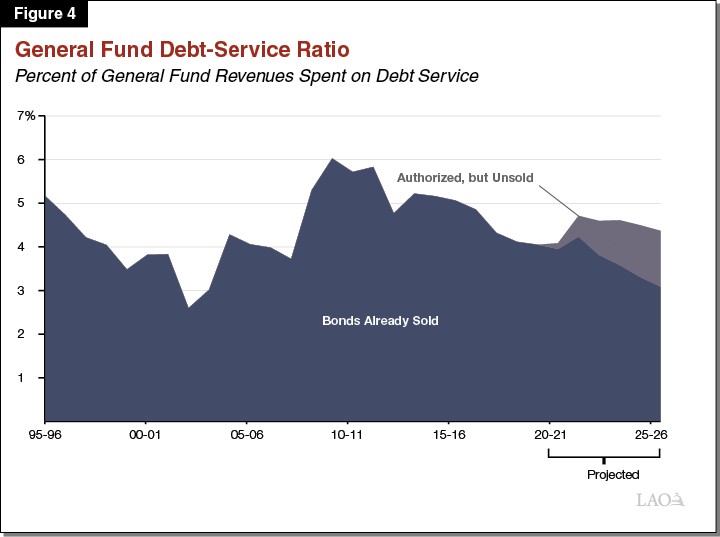

- Debt Service Reduces Fiscal Resources. Debt service payments reduce the amount of resources available for other state spending for many years. For this reason, bond‑funded spending should be spent in ways that produce ongoing benefits rather than one‑time benefits. Moreover, unlike other state spending, debt service cannot be scaled back during economic slowdowns. As a result, high debt service costs put pressure on other parts of the state’s budget when state revenues are down. This means that the trade‑off between bond‑funded stimulus and other spending is greater when the state’s existing debt service costs are higher. Figure 4 shows the historical ratio of debt service costs to General Fund revenues. The current debt‑service ratio of 4.1 percent in 2020‑21 is somewhat below the historical average of 4.9 percent in the ten prior years, and well below the peak of 6 percent in 2009‑10.

Does the Proposal Have Other Strong Policy Justifications?

- Would the Stimulus Proposal Advance Other Legislative Priorities? Given that few state‑funded stimulus proposals are likely to generate large benefits (relative to the size of the state’s economy), and these benefits often are very uncertain, considering the broader policy effects of the proposals is important. For example, the Legislature likely will be presented with “green” stimulus proposals in the coming months and years that purport to stimulate the economy and also have an environmental benefit. Our office recently released a separate report, A Framework for Evaluating State‑Level Green Stimulus Proposals, to provide guidance for the Legislature on how to evaluate such proposals. Rarely will it make sense for the state to adopt a proposal for the sake of potential economic stimulus alone, given the state’s limited fiscal capacity. Instead, the Legislature should prioritize proposals that achieve other policy goals while also offering potential economic stimulus.

- Programs Providing Little Short‑Term Stimulus Can Still Have Long‑Term Economic Benefits. Some programs that do not create immediate economic benefits may nonetheless generate significant economic benefits or fiscal savings over a longer period of time. For example, a program to increase the energy efficiency of state‑owned buildings might not provide immediate economic benefits if the equipment is purchased from suppliers located outside the state. However, the program should be considered on its policy merits—in this case, reducing ongoing state operating costs—in the context of other state budget priorities.

How Does the Proposal Interact With Other Federal, State, and Local Programs?

- Avoid Unnecessary Duplication. Before creating a new stimulus program, policymakers should take stock of existing efforts at the federal, state, and local levels. Having many similar programs spread across different state agencies or different levels of government can be inefficient and confusing for the people or businesses the programs are intended to benefit. For example, in our analysis The 2019‑20 Budget: Opportunity Zones, we argued that creating a new state Opportunity Zone program to fund affordable housing would add an unnecessary layer of complication to the financing of affordable housing.

- Find Ways to Complement Existing Programs. As mentioned previously, the federal government’s capacity to fund stimulus programs far exceeds the state’s. Given the state’s more limited role, finding ways to complement, and not duplicate, federal efforts can be especially important. For example, last year the state expanded financial assistance to undocumented individuals that are not eligible for federal stimulus programs.

- Be Cautious of Unintended Interactions. Unintended interactions between a new stimulus program and other federal, state, and local programs can reduce its effectiveness. Policymakers should carefully consider these potential interactions. Examples include: Could increasing assistance for people or businesses through one program affect their eligibility for other programs? Could a change in state tax law affect Californians’ federal taxes? Do state actions to increase funding for one program impede local efforts to fund related programs?

How Might the Expected Benefits and Costs Be Overstated or Understated?

The benefits and costs of new stimulus programs may be less than or greater than expected if the initial assumptions turn out to have been inaccurate. The actual economic benefits and costs of stimulus programs depend in part on factors that are uncertain, such as future labor market conditions and behavioral responses by affected businesses. Asking the following questions can help Legislators assess whether the estimated economic and fiscal effects presented to them are reasonable.

- Is This an Established Program or a New Program? The estimated benefits from increased funding for an existing program with an established history are likely more certain than estimates for a new program. A proposal for a new program might have optimistic economic or fiscal estimates that do not account for factors that could significantly reduce the net benefits, such as unforeseen implementation difficulties or low participation rates.

- How Large Are the Administrative Costs? All programs have costs for public administration. The administrative costs of an economic stimulus program ideally should be a small share of the overall cost. A small program with a complicated enrollment process may have relatively high administrative costs that diminish the amount of funds available for delivering the intended economic benefits. On the other hand, a large program with low administrative overhead may be more efficient.

- Will the Program Effectively Increase Private Sector Hiring and Investment? Many state programs—such as tax reductions, loans, and industrial subsidies—are intended to encourage people or their businesses to take certain actions that would increase spending, hiring, or investment. For example, in 1980, the state adopted a program that reduced the taxes of companies that invested in new technology that increased the efficiency of their power plants (specifically, cogeneration systems). However, the amount of the tax savings was too small to have an effect on the number of qualified power plants that were built or retrofitted using the new technology. As a result, the economic benefits from the program were more than offset by reductions in state spending elsewhere in the budget to pay for the program. In considering targeted incentives to increase spending, hiring, and business investments, balancing the cost of the program with its likelihood of being large enough to actually change the decisions of people or businesses is critical.

- Are There Constraints in the Labor Market? Fiscal stimulus often is intended to create new employment opportunities. Certain circumstances can make the economic stimulus more effective at increasing employment. For example, stimulus may be more effective when overall unemployment is high or when the stimulus is targeted at a sector with high unemployment. Conversely, stimulus can be less effective when there are constraints that would make hiring difficult—for example, when unemployment is very low for key occupations and licensing requirements or other factors prevent new workers from joining the local labor market.

- How Much of the Funding Will Be Spent Outside the State? As our economy is closely integrated with other states and other countries, some of the economic benefits from new spending in California will go to areas outside the state. The extent of these so‑called “spillover” effects can affect the overall economic benefit to California from new stimulus spending. One key question to ask to assess the extent of spillover is: What portion of the workers and materials will come from within California? If more comes from within California, then the economic benefit from the stimulus spending will be bigger. However, if a project relies on a lot of materials that are not locally sourced, then the spillover might be large and the benefit could be smaller or negative. For example, the economic benefit from a bridge replacement project that requires buying steel components sourced from another country might be lower than expected if the estimates had assumed unadjusted average construction industry multipliers.

Will the Benefits Be Realized When They Are Needed?

- Fiscal Stimulus May Be More Effective During A Recession. New public spending is likely to be more effective at stimulating the economy during and immediately following a recession rather than late in an economic expansion. This is because the increased public spending may be less likely to displace private sector spending due to the amount of slack in the economy. For example, state projects are less likely to be competing with private businesses for goods and services that are in limited supply.

- Consider the Timing of When Benefits Will Occur. The benefits of a new stimulus program will take some time to occur. The amount of time will depend on both how quickly the program can be implemented as well as how quickly the new initial economic activity circulates throughout the economy. For example, a completely new program may take several years to be implemented fully. Similarly, the planning, permitting, and completion of the final design of new construction projects can take several years, even if preliminary designs were previously completed. Assessing the timing of new stimulus spending may be possible by examining similar investments made in the past. Increasing funding for existing programs could more quickly provide economic benefits than creating a new program.

How Might the Benefits Be Distributed?

- Many State Programs Benefit a Specific Group or Region by Design. Many state programs directly benefit one group or another, rather than all residents broadly. For example, expanding childcare primarily benefits families with young children and reducing college tuition primarily benefits college students. Economic stimulus can be broad or targeted. In assessing an economic stimulus proposal, consider which groups would directly benefit from the new program and whether that is consistent with the needs of the economy.

- Some Proposals Intended to Address Inequities. Some of the state’s economic development policies target investment in areas of the state with high poverty and high unemployment. When considering a proposal designed to target areas for economic development, carefully scrutinizing the rules or standards used to identify these areas is important. Many past programs have been ineffective because of overly broad or ambiguous targeting.

- Consider Whether Stimulus Proposals Might Exacerbate Inequities. Low‑income households and small businesses may be less prepared to apply for broad‑based financial assistance than wealthier households and more established businesses. For example, federal financial assistance provided to businesses in April 2020 through the Paycheck Protection Program flowed first to businesses with existing relationships with banks. Less affluent communities also may be less prepared to compete for stimulus spending. For example, a community that has spent local funds to plan for and design infrastructure projects in advance of external funding likely would be better positioned to compete for stimulus infrastructure spending than communities that lacked funding to do such preparation.

Considerations Specific to the COVID‑19 Pandemic

In our recent report, The 2021‑22 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we forecast that the state will begin the 2021‑22 fiscal year with a one‑time surplus of about $26 billion. This large revenue windfall provides the Legislature with an opportunity to mitigate the adverse economic and health consequences of the public health emergency. As part of this overall response, the Legislature also may consider using a portion of these funds for one‑time fiscal stimulus. In addition to the general guidance above, we suggest the Legislature consider several additional unique factors related to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

- Target Most Impacted Communities and Businesses. The COVID‑19 pandemic and recession has disproportionately affected many low‑income workers; communities of color; and businesses in tourism, hospitality, and close‑contact personal services industries. Directly targeting stimulus proposals to the most affected households and businesses could more effectively address these disparities than broad‑based economic stimulus. At the same time, it is important to be mindful that disadvantaged communities might be less prepared to compete for targeted stimulus. One option for targeting stimulus without placing undue administrative burdens on intended beneficiaries could be to limit eligibility to certain geographical regions or industrial classifications.

- Some Types of Economic Stimulus Would Be Counterproductive Until Public Health Emergency Resolved. Stimulating economic activity that would increase the risk of spreading COVID‑19 would be counterproductive. Stimulus targeted at increasing tourism or large indoor gatherings, for example, likely would increase the negative health effects of the pandemic. During this time, the state might instead provide targeted financial assistance to households and businesses that have lost income to minimize additional adverse economic effects. Over time, such economic relief also provides broader indirect economic benefits. In the absence of federal programs, however, we note that the state has relatively modest capacity for direct financial payments to affected households and businesses.

- Prioritize Stimulus Spending on Proposals With Public Health Co‑Benefits. Public health programs that also have economic stimulus co‑benefits are particularly important right now given the pandemic’s severity and the close relationship between the economy and the public health situation. The Legislature could look for opportunities to increase funding for effective existing programs that address both needs. Examples might include providing training in relevant public health jobs and contracting with California companies for business services related to the state’s pandemic response.

- Some Increased Borrowing for Stimulus Spending Could Be Reasonable. This is a relatively good time to finance stimulus spending for major deferred maintenance and necessary infrastructure projects because interest rates are at historic lows. The Legislature could consider whether spending under previously authorized bonds can be accelerated. The state also may borrow against special fund revenues for some types of spending without first getting voter approval. However, policymakers should consider that planning and initiating new construction projects often is a lengthy process. While the long‑term economic benefits from new infrastructure spending may have strong policy merit, the amount of time needed to begin construction may be too long to provide meaningful economic stimulus coming out of an economic recession.

Appendix

Prior Evaluations of the Economic Effects of State Programs

The Legislature occasionally asks our office to evaluate the economic and fiscal effects of state programs and policies. Our research has raised issues for legislative consideration about the potential effectiveness of the state programs that we reviewed. In addition, we have endeavored to increase awareness about the challenges and limitations of such analyses. We highlight three recent studies below.

Film and Television Production Tax Incentives. We evaluated the economic effects of an income tax credit for motion picture production in 2016 at the request of the legislature. In this report, we estimated that about one‑third of the film and television projects that received a tax credit under this program would probably have been made in California anyway. We found that the $800 million program may have increased the state’s economic output by between $6 billion and $10 billion over ten years. Our report also highlighted key areas of uncertainty and additional factors the legislature should consider beyond the bottom line economic results of the analysis—such as opportunity costs and the policy objective of the program which was to strategically counter aggressive film tax credits offered by other states. This report is available online.

Sales Tax Exemption for Certain Manufacturers. In 2018, we evaluated the economic effects of a sales tax exemption administered by the California Alternative Energy and Advanced Transportation Financing Authority. This exemption is available for equipment used for certain manufacturing activities such as aerospace, electric vehicles, and alternative energy equipment. In this report, we concluded that the exemption likely has some positive economic effects on the targeted industries in California. Whether the program had positive or negative net effects on the state’s economy as a whole was unclear, however. This report, which is available online, includes an appendix that discusses the economic effects of the program in detail and explains why the estimates of these effects are highly uncertain.

State Policies to Reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions. Pursuant to a statutory requirement, our office reports annually to the Legislature on the economic effects of the state’s statutory GHG emission goals. Our 2018 report, Assessing California’s Climate Policies: An Overview, provides a conceptual overview of the potential economic effects of state GHG reduction policies and explains key economic concepts and the challenges in estimating the overall effects of the policies.